SUMMARY

Abasic (AP) sites are the most common DNA lesions formed in cells, induce severe blocks to DNA replication, and are highly mutagenic. Human Y-family translesion DNA polymerases (pols) such as pols η, ι, κ, and REV1 have been suggested to play roles in replicative bypass across many DNA lesions where B-family replicative pols stall, but their individual catalytic functions in AP site bypass are not well understood. In this study, oligonucleotides containing a synthetic abasic lesion (tetrahydrofuran analogue) were compared for catalytic efficiency and base selectivity with human Y-famliy pols η, ι, κ, and REV1 and B-family pols α and δ. Pol η and pol δ/PCNA copied past AP sites quite effectively and generated products ranging from one-base to full-length extension. Pol ι and REV1 readily incorporated one base opposite AP sites but then stopped. Pols κ and α were severely blocked at AP sites. Pol η preferentially inserted T and A; pol ι inserted T, G, and A; pol κ inserted C and A; REV1 preferentially inserted C opposite AP sites. The B-family pols α and δ/PCNA preferentially inserted A (85and 58%, respectively) consonant with the A-rule hypothesis. Pols η and δ/PCNA were much more efficient in next base extension, preferably from A positioned opposite an AP site, than pol κ. These results suggest that AP sites might be bypassed with moderate efficiency by single B- and Y-family DNA polymerases or combinations, possibly by REV1 and pols ι, η, and δ/PCNA at the insertion step opposite the lesion and by pols η and δ/PCNA at the subsequent extension step. The patterns of the base preferences of human B-family and Y-family DNA polymerases in both insertion and extension are pertinent to some of the mutagenesis events induced by AP lesions in human cells.

Keywords: DNA polymerase, Y-family, B-family, translesion synthesis, abasic lesion

Introduction

An abasic (apurinic/apyrimidinic, AP) site is one of the most abundant DNA lesions produced in cells.1 AP sites are derived from the cleavage of N-glycosidic bonds in DNA, which occurs spontaneously, chemically, and enzymatically during base excision repair. AP sites that escape from DNA repair by AP endonucleases and nucleotide excision repair are very detrimental to cells because these DNA lesions induce strong blockage of DNA replication and are highly mutagenic due to their non-instructional nature. The mechanism of miscoding caused by AP sites is largely attributed to translesion DNA synthesis (TLS) promoted by some specialized DNA polymerases across those lesions, in which DNA replication by replicative DNA polymerases is usually stalled in yeast and Escherichia coli.2,3

At least fourteen DNA polymerases are known to be present in human cells.4 Among them, Y-family DNA polymerases (e.g. pols η, ι, κ, and REV1) are generally considered to act as the main translesion DNA polymerases that effectively bypass a variety of DNA lesions that B-family replicative DNA polymerases—e.g., pols α, δ, and ɛ—are strongly blocked at. The specialized lesion bypass abilities of Y-family DNA polymerases are attributed to their spacious active site clefts, which can accommodate a variety of bulky DNA lesions.5 In this context, the size of a DNA AP site devoid of a base is not large and even smaller than that of a normal nucleotide. Thus, the AP site per se does not need any large active site cleft of Y-family DNA polymerases. AP sites do not alter the B-form geometry of duplex DNA but induce local perturbation around the lesion site, depending on the paired base, which might be a replicative obstacle.6,7 Therefore, DNA polymerases might need some flexibility to tolerate the slightly deformed DNA structure around AP sites (across AP sites).

Some human DNA polymerases (e.g., REV1 and pol θ) have been suggested to efficiently bypass AP sites in vitro. Human REV1, a Y-family DNA polymerase that is believed to also play a structural role in translesion DNA synthesis as a scaffold protein, efficiently inserts dCTP opposite AP sites as well as bulky N2-alkyl G lesions by utilizing a distinctive mechanism of protein-template-directed nucleotide incorporation.8,9 Pol θ, an A-family DNA polymerase, is able to efficiently incorporate bases opposite AP sites and extend primers following insertion in vitro.10 Two Y-family DNA polymerases, pols η and κ, are believed to be inefficient at translesional bypass across AP sites in vitro,11,12 whereas the other Y-family DNA polymerase (pol ι) appears to be variably competent.13 However, a careful side-by-side comparison of the individual catalytic properties in AP lesion bypass among human DNA polymerases has not been reported.

Interestingly, recent reports suggest that heterotetrameric human pol δ (in complex with PCNA), a B-family replicative DNA polymerase acting on lagging strand DNA synthesis, is able to copy past small DNA adducts such as N2-ethyldeoxyguanosine, O6-methyldeoxyguanosine, and abasic lesions.14–16 However, the detailed kinetic properties such as catalytic efficiencies and base preferences of human pol δ/PCNA in AP lesion bypass have not been reported. Although the kinetic analyses of replicative bypasses opposite the AP site have been performed with some human DNA polymerases, those studies were performed using the different experimental settings and thus the resulting data have not been very useful for kinetic comparison between individual polymerases. Therefore, comparisons of the efficiencies and specificities of in vitro AP lesion bypasses by translesional Y-family and replicative B-family DNA polymerases are desirable, making speculation possible about their individual roles in AP lesion bypass in cells.

In order to better understand the kinetic properties of AP lesion bypass by human Y-family and B-family pols, we performed primer extension and the steady-state kinetic experiments by utilizing a synthetic AP site analogue (tetrahydrofuran)-containing oligonucleotide and analyzed the efficiencies and specificities of nucleotide insertion opposite and past an AP site with the available human B-family DNA polymerases α and δ and Y-family DNA polymerases η, ι, κ, and REV1. We provide evidence that human pol η and pol δ/PCNA are able to insert nucleotides opposite AP sites and also extend primers further past the lesion with moderate efficiencies, whereas pol ι and REV1 can efficiently insert only one nucleotide opposite an AP site and cannot extend further. The implications of the in vitro catalytic properties of human Y-family DNA polymerases in AP lesion bypass are discussed in comparison with B-family DNA polymerases.

Results

Extension of Primers Opposite an AP Site in the Presence of All Four dNTPs

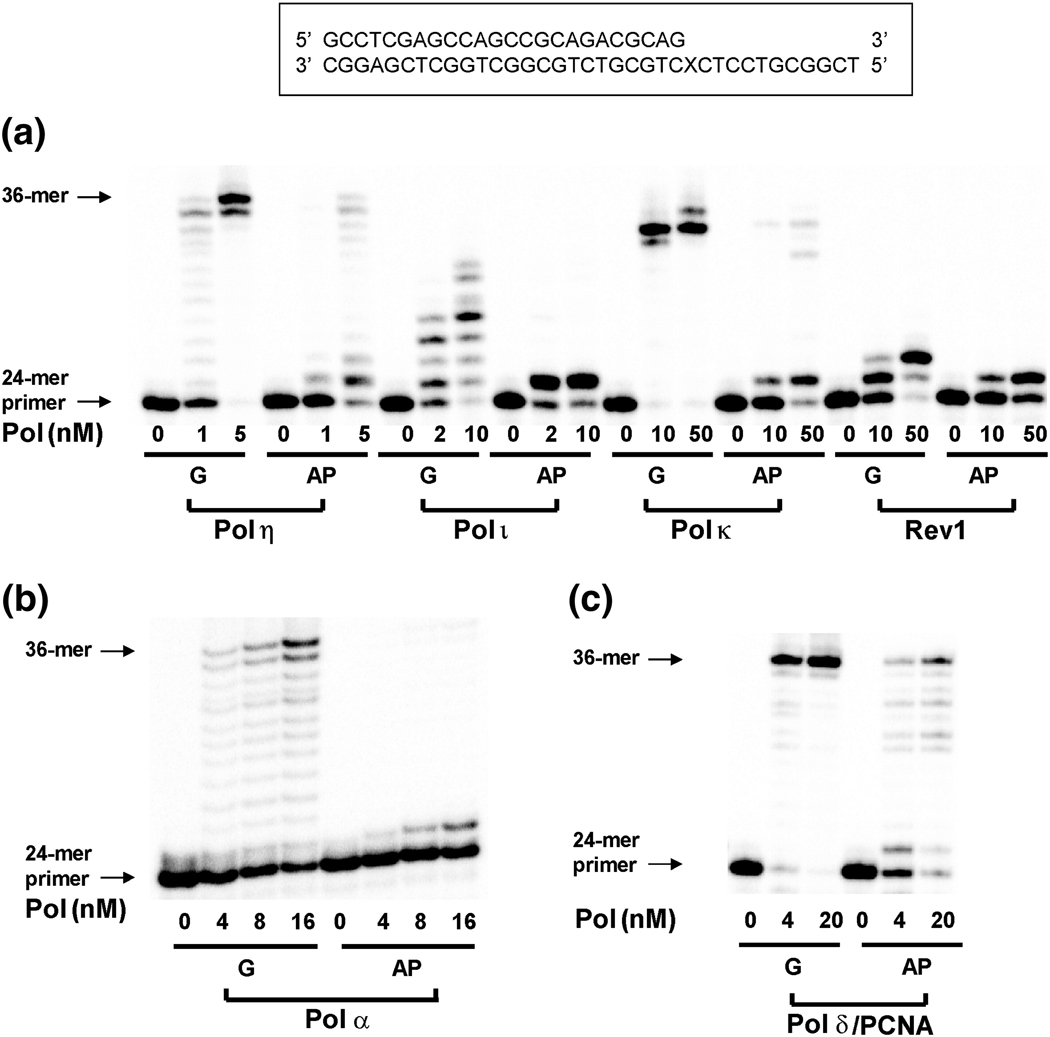

In order to evaluate the qualitative differences in DNA polymerization across an AP site by B- and Y-family human DNA polymerases, the 24-mer primers were annealed to the templates containing G or a synthetic AP site at the 25th position (Table 1) and extended in the presence of all four dNTPs using each of the human DNA polymerases available (pols α, δ, η, ι, κ, and REV1) (Fig. 2). Unmodified G was utilized as a normal control template base for comparison with the AP site because guanine is known to be lost most easily in DNA.17 All experiments with pol δ were done in the presence of PCNA; among the polymerases examined, only pol δ has been shown to intrinsically require PCNA for efficient in vitro synthesis on relatively short DNA substrates.18,19 Pol ι and REV1 readily incorporated one base opposite an AP site but stopped after the insertion (Fig. 2a). Pol η fully extended the primer across an AP site of template DNA, to some extent, whereas pol κ was strongly stalled at an AP site and yielded mostly one-base incorporated products and a trace of 34-mer products, but only at a high concentration (50 nM) of enzyme. Interestingly, pol δ (with PCNA) also fully extended the primer across an AP site to some extent (Fig. 2c) but pol α hardly incorporated even one base and stopped after insertion (Fig. 2b), indicating that a B-family DNA polymerase, pol δ (with PCNA), might have a significant AP lesion bypass ability that is very similar to pol η.

Table 1.

Oligodeoxynucleotides used in this study

| 24-mer | 5′ GCCTCGAGCCAGCCGCAGACGCAG |

| 25-A-mer | 5′ GCCTCGAGCCAGCCGCAGACGCAGA |

| 25-T-mer | 5′ GCCTCGAGCCAGCCGCAGACGCAGT |

| 25-G-mer | 5′ GCCTCGAGCCAGCCGCAGACGCAGG |

| 25-C-mer | 5′ GCCTCGAGCCAGCCGCAGACGCAGC |

| 36-mer | 3′ CGGAGCTCGGTCGGCGTCTGCGTCXCTCCTGCGGCT |

| X: A, T, G, C, AP site (tetrahydrofuran) | |

Fig. 2.

Extension of a 32P-labeled 24-mer primer opposite G and AP site at position 25 by human Y-family and B-family DNA polymerases. Primer (24-mer) was annealed with each of the two different 36-mer templates (Table 1) containing an unmodified G or AP site (tetrahydrofuran) placed at the 25th position from the 3′-end (see Fig. 1). Reactions were done for 10 min with increasing concentrations of (a) Y-family DNA polymerases: pols η (0 − 5 nM), ι (0 − 10 nM), κ (0 − 50 nM) or REV1 (0 − 50 nM) and (b) B-family DNA polymerases: pols α (0 − 16 nM) or δ (0 − 20 nM)/PCNA (300 nM), with a constant concentration of DNA substrate (100 nM primer/template) as indicated. 32P-labeled 24-mer primer was extended in the presence of all four dNTPs. The reaction products were analyzed by denaturing gel electrophoresis with subsequent phosphoimaging analysis.

Steady-state Kinetics of Nucleotide Incorporation into Primers Opposite an AP Site

To quantitatively analyze insertion efficiency of single nucleotides opposite a AP site by individual Y- and B-family human DNA polymerases, steady-state kinetic parameters were determined for the incorporation of single nucleotides into 24-mer/36-mer duplexes opposite G or a synthetic AP site (Table 1). Insertion efficiencies for the addition of a single nucleotide opposite a template AP site (i.e., kcat/Km) provide a quantitative measure for base insertion ability and selectivity opposite an AP site by DNA polymerases. The catalytic efficiencies (kcat/Km) for dNTP incorporation opposite a template AP site were compared with those for dCTP incorporation opposite template G by each polymerase in order to calculate the relative efficiency of base insertion.

Efficiencies of nucleotide insertion opposite an AP site varied among DNA polymerases (Tables 2–3). Pol ι was the most efficient for insertion of all four bases opposite an AP site (relative efficiency 0.7 – 3), comparable or superior to normal dCTP incorporation opposite G. Pol η and Rev1 inserted T (or A) and C, respectively, opposite an AP site with fairly good insertion efficiencies (relative efficiency 0.06 – 0.07). Pol κ was the least efficient (relative efficiency 0.0001 – 0.0009) in base insertion opposite an AP site, among the Y-family DNA polymerases. Interestingly, a B-family DNA polymerase—pol δ, with PCNA—showed moderate insertion efficiency (relative efficiency 0.012) for dATP insertion, which was only about 5-fold lower than pol η, but one and two orders of magnitude higher than pols α and κ, respectively.

Table 2.

Steady-state kinetic parameters for one-base incorporation opposite an AP site and G by human pols η, ι, κ, and REV1

| Polymerase | Template | dNTP | Km (µM) | kcat (s−1) |

kcat/Km (mM−1 s−1) |

dNTP selectivity ratioa |

Relative efficiencyb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| η | AP site | A | 40 ± 6 | 0.12 ± 0.004 | 3.0 | 0.95 | 0.065 |

| T | 290 ± 50 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 3.2 | 1 | 0.070 | ||

| G | 8.5 ± 1.0 | 0.005 ± 0.0001 | 0.59 | 0.19 | 0.013 | ||

| C | 210 ± 20 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.67 | 0.21 | 0.015 | ||

| G | C | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 0.12 ± 0.005 | 46 | 1 | ||

| ι | AP site | A | 210 ± 40 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 2.6 | 0.45 | 1.4 |

| T | 130 ± 20 | 0.74 ± 0.02 | 5.7 | 1 | 3.0 | ||

| G | 120 ± 10 | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 3.9 | 0.69 | 2.1 | ||

| C | 570 ± 140 | 0.77 ± 0.05 | 1.4 | 0.24 | 0.74 | ||

| G | C | 300 ± 30 | 0.57 ± 0.02 | 1.9 | 1 | ||

| κ | AP site | A | 1600 ± 200 | 0.077 ± 0.005 | 0.048 | 0.77 | 0.00065 |

| T | 2300 ± 700 | 0.017 ± 0.002 | 0.0074 | 0.12 | 0.00010 | ||

| G | 400 ± 70 | 0.0032 ± 0.0002 | 0.008 | 0.13 | 0.00011 | ||

| C | 780 ± 220 | 0.049 ± 0.005 | 0.063 | 1 | 0.00085 | ||

| G | C | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 74 | 1 | ||

| REV1 | AP site | A | 140 ± 50 | 0.000025 ± 0.000002 | 0.00018 | 0.0031 | 0.00019 |

| T | 190 ± 30 | 0.000072 ± 0.000003 | 0.00038 | 0.0067 | 0.00040 | ||

| G | 190 ± 50 | 0.000031 ± 0.000003 | 0.00016 | 0.0029 | 0.00017 | ||

| C | 210 ± 30 | 0.012 ± 0.001 | 0.057 | 1 | 0.061 | ||

| G | C | 12.8 ± 50 | 0.012 ± 0.0003 | 0.94 | 1 | ||

dNTP selectivity ratio, calculated by dividing kcat/Km for each dNTP incorporation by the highest kcat/Km for dNTP incorporation opposite AP site.

Relative efficiency, calculated by dividing kcat/Km for each dNTP incorporation opposite AP site by kcat/Km for dCTP incorporation opposite G.

Table 3.

Steady-state kinetic parameters for one-base incorporation opposite an AP site and G by human pols α and δ/PCNA

| Polymerase | Template | dNTP | Km (µM) | kcat (s−1) |

kcat/Km (mM−1 s−1) |

dNTP selectivity ratioa |

Relative efficiencyb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | AP site | A | 570 ± 100 | 0.0083 ± 0.0001 | 0.015 | 1 | 0.0010 |

| T | 250 ± 60 | 0.00046 ± 0.00003 | 0.0018 | 0.12 | 0.00012 | ||

| G | 550 ± 120 | 0.00024 ± 0.00002 | 0.0004 | 0.027 | 0.00003 | ||

| C | 980 ± 50 | 0.00047 ± 0.000001 | 0.0005 | 0.033 | 0.00003 | ||

| G | C | 0.42 ± 0.09 | 0.0064 ± 0.0003 | 15 | 1 | ||

| δ/PCNA | AP site | A | 25 ± 6 | 0.0067 ± 0.0004 | 0.27 | 1 | 0.012 |

| T | 62 ± 16 | 0.0060 ± 0.0004 | 0.097 | 0.36 | 0.0044 | ||

| G | 110 ± 20 | 0.010 ± 0.001 | 0.091 | 0.34 | 0.0041 | ||

| C | 880 ± 160 | 0.0069 ± 0.0006 | 0.0078 | 0.029 | 0.0004 | ||

| G | C | 0.27 ± 0.05 | 0.0059 ± 0.0002 | 22 | 1 | ||

dNTP selectivity ratio, calculated by dividing kcat/Km for each dNTP incorporation by the highest kcat/Km for dNTP incorporation opposite AP site.

Relative efficiency, calculated by dividing kcat/Km for each dNTP incorporation opposite AP site by kcat/Km for dCTP incorporation opposite G.

With B-family DNA polymerases, pols α and δ/PCNA preferentially incorporated A (dATP selectivity 85% and 58%, when calculated from the equation = (kcat/Km)dNTP/∑(kcat/Km)dNTP × 100) opposite an AP site (Table 3). In contrast, Y-family DNA polymerases preferentially incorporated different bases depending on the DNA polymerase, as follows: T (43%) and A (41%) by pol η, T (42%), G (29%), and A (19%) by pol ι, C (50%) and A (38%) by pol κ, C (98%) by REV1 (Table 2). Considering that the next base to an AP site on template DNA is C, dGTP incorporation might be expected if DNA polymerase skips an AP site and incorporates a base opposite the next base C. However, most of the cases with pols η and κ showed lower incorporation of dGTP than other nucleotides, indicating that the majority of nucleotide incorporation might occur opposite an AP site but not opposite the base 5’ to an AP site, at least in the DNA sequence context used here.

Primer Extension Opposite the Next Base Following an AP Site in the Presence of All Four dNTPs

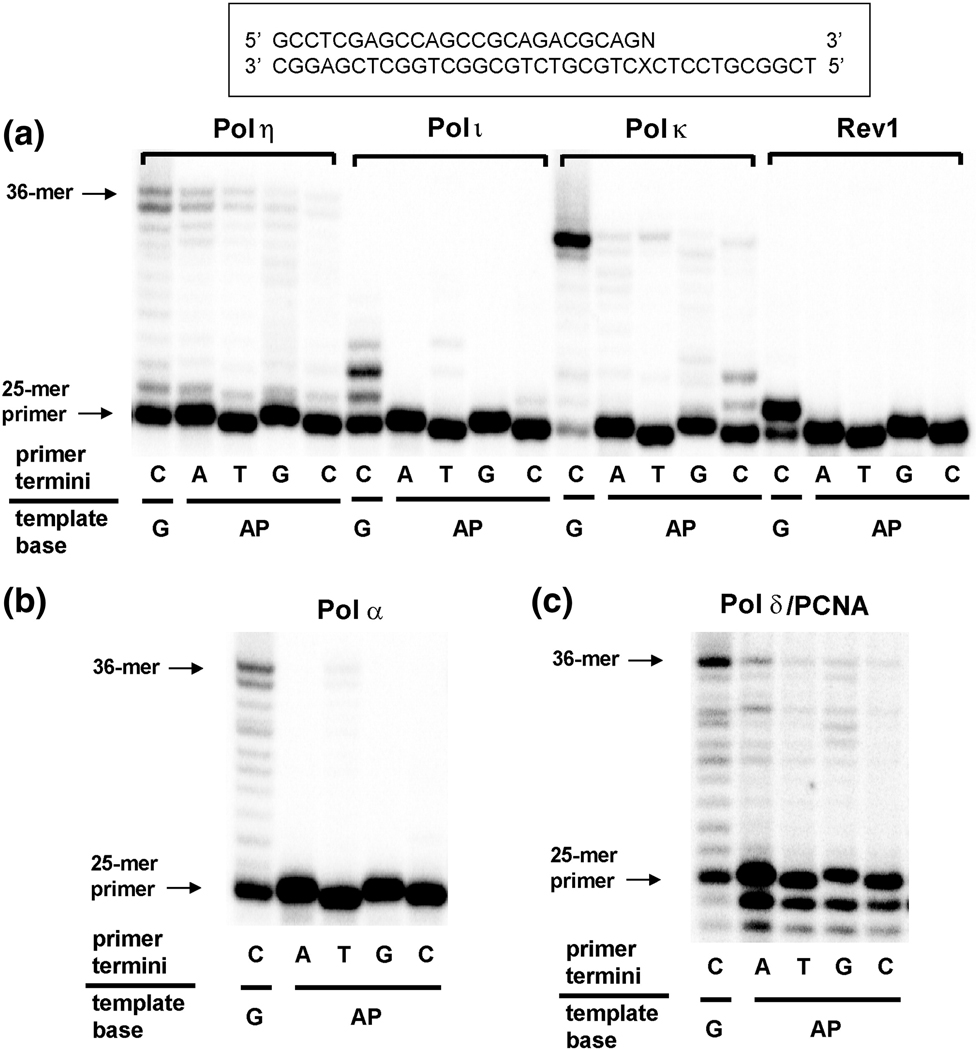

Primer extension experiments by various DNA polymerases were done with a 25-mer primer (Table 1) containing a 3’-end base (A, T, G or C) positioned opposite an AP site of a 36-mer template in the presence of all four dNTPs, for comparison with primer extension from the normal C:G pair of a 25-mer/36-mer primer-template complex (Fig. 3). Among the DNA polymerases tested, pols η, κ, and δ/PCNA showed significant extension activities opposite the next base following an AP site, whereas pols α, ι, and REV1 showed almost no extension. Pols η and δ/PCNA extended primers most efficiently from an A:AP site pair among the four possible N:AP site pairs of primer/template termini and generated considerable full-length extension products, only slightly less than extension from the normal C:G pair. Pol κ generated only trace extension products from T (or C):AP site pairs, but much less than from a normal C:G pair.

Fig. 3.

Extension of a 32P-labeled 25-mer primer opposite next base from G and AP site by human Y-family and B-family DNA polymerases. Primer (25-mer) containing an A, T, G, or C at the 3’end was annealed with each of the two different 36-mer templates (Table 1) containing an unmodified G or AP site (tetrahydrofuran) placed at the 25th position from the 3′-end (see Fig. 1). Reactions were done for 10 min with each of (a) Y-family DNA polymerases: pols η (1 nM), ι (2 nM), κ (10 nM), or REV1 (40 nM) and (b) B-family DNA polymerases: pols α (8 nM) or δ (2 nM)/PCNA (300 nM), with a constant concentration of DNA substrate (100 nM primer/template) as indicated. 32P-labeled 25-mer primer was extended in the presence of all four dNTPs. The reaction products were analyzed by denaturing gel electrophoresis with subsequent phosphoimaging analysis.

Steady-state Kinetics of Next-base Extension Following an AP Site

To quantitatively analyze the efficiency of next-base extension following an AP site by human DNA polymerases, steady-state kinetic parameters were determined for next-base extension (i.e. incorporation of the next complementary nucleotide, dGTP opposite C) into 25-A-(T, G, or C)-mer/36-AP-mer duplexes (Tables 1, 4 and 5), in comparison with next-base extension from the normal C:G (or T:A) pair of a 25-mer/36-mer primer-template complex. In good agreement with the next-base extension profiles in Fig. 3, pol η preferentially extended the primer from the A:AP site pair (among various pairs of primer/template termini), whereas pol κ extended the primer preferably from T (or C):AP primer/template termini. Pol η (relative extension efficiency 0.066) was about 110-fold more efficient for next-base extension than pol κ (relative extension efficiency 0.0006), indicating that pol η may have the most efficient next-base extension ability past an AP site among Y-family DNA polymerases. Interestingly pol δ/PCNA (relative extension efficiency 0.0068) was about 11-fold and 400-fold more efficient for next-base extension than pol κ and pol α (relative extension efficiency 0.000018) respectively, indicating that a B-family DNA polymerase—pol δ (with PCNA)— has relatively good next-base extension activity past an AP site.

Table 4.

Steady-state kinetic parameters for next base extension from an AP site:A (or T, G, C) pair and G:C pair template:primer termini by human pols η and κ

| Polyme rase |

Base-pair at 3’ primer termini (template:primer) |

Extension with dGTP (the correct nucleotide against next template C) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (µM) | kcat (s−1) |

kcat/Km (mM−1 s−1) |

Relative base-pair selectivity ratioa |

Relative extension efficiencyb |

||

| η | AP:A | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 0.011 ± 0.001 | 2.3 | 1 | 0.066 |

| AP:T | 11 ± 3 | 0.0015 ± 0.0001 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.0040 | |

| AP:G | 11 ± 2 | 0.0037 ± 0.0001 | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.0097 | |

| AP:C | 6.4 ± 1.2 | 0.0021 ± 0.0001 | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.0040 | |

| G:C | 0.43 ± 0.12 | 0.015 ±0.001 | 35 | 1 | ||

| κ | AP:A | 980 ± 40 | 0.0044 ± 0.0001 | 0.0045 | 0.58 | 0.00035 |

| AP:T | 120 ± 30 | 0.00092 ± 0.00006 | 0.0077 | 1 | 0.00059 | |

| AP:G | 400 ± 100 | 0.00066 ± 0.00005 | 0.0017 | 0.22 | 0.00013 | |

| AP:C | 80 ± 20 | 0.00059 ±0.00004 | 0.0074 | 0.96 | 0.00057 | |

| G:C | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 0.070 ± 0.004 | 13 | 1 | ||

Relative base-pair selectivity ratio, calculated by dividing kcat/Km for each dGTP incorporation by the highest kcat/Km for dGTP incorporation opposite the next template C from the AP site:N (N=A, T, G, or C) pair.

Relative extension efficiency, calculated by dividing kcat/Km for each dGTP incorporation opposite the next template C from the AP site:N pair by kcat/Km for dGTP incorporation opposite the next template C from the normal G:C pair.

Table 5.

Steady-state kinetic parameters for next base extension from T:A and AP site:A template:primer termini by human pols α and δ/PCNA

| Polyme rase |

Base-pair at 3’ primer termini (template:primer) |

Extension with dGTP (the next correct nucleotide against template C) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (µM) | kcat (s−1) |

kcat/Km (mM−1 s−1) |

Relative extension efficiencya | ||

| α | T:A | 0.78 ± 0.10 | 0.015 ± 0.001 | 19 | 1 |

| AP:A | 500 ± 50 | 0.00017 ± 0.00001 | 0.00034 | 0.000018 | |

| δ/ PCNA |

T:A | 0.18 ± 0.0004 | 0.0074 ± 0.0004 | 41 | 1 |

| AP:A | 280 ± 80 | 0.0010 ± 0.0001 | 0.28 | 0.0068 | |

Relative extension efficiency, calculated by dividing kcat/Km for each dGTP incorporation opposite the next template C from the AP site:A pair by kcat/Km for dGTP incorporation opposite the next template C from the normal T:A pair.

Discussion

In this study we investigated the bypass ability and base selectivity of human B- and Y-family DNA polymerases opposite an AP site of template DNA, in order to examine how differently these polymerases deal with the AP site. Two sequential steps of DNA lesion bypass, the base incorporation opposite an AP site and subsequent extension by individual polymerases, were analyzed in two main sets of experiments: (i) primer-extension assays in the presence of all four dNTPs and (ii) steady-state kinetic analyses of single nucleotide incorporation with individual dNTPs. Our direct comparisons of experimental data for each polymerase provide a basis for understanding the complexity of AP site bypass by single and multiple human DNA polymerases. For the initial incorporation step opposite an AP site, pol ι was most efficient and REV1, pol η, and pol δ/PCNA were moderately efficient, whereas pol α and pol κ were least efficient. For the subsequent extension step only two DNA polymerases—pol η and pol δ/PCNA—were reasonably efficient. Two B-family DNA polymerases, pol α and pol δ/PCNA (but none of Y-family DNA polymerases) followed the A-rule hypothesis20 when inserting a nucleotide opposite an AP site.

We applied comparative kinetic analyses combined with “standing start” full-length extension assays, which were preferred under the same experimental conditions, to qualitatively and quantitatively measure the catalytic function of each DNA polymerase at an AP site. The steady-state kinetic parameter kcat/Km was utilized as a quantitative measure of catalytic efficiency and specificity in nucleotide incorporation by DNA polymerases. In our work, kcat/Km might be a reliable catalytic indicator for the cases with human Y-family DNA polymerases and pol α, which are distributive (i.e. not processive) enzymes, but there are limitations with this parameter that can underestimate the catalytic efficiency for highly processive polymerases.21 With the human pol δ/PCNA complex, steady-state kinetic parameters may have caveats but are still useful for approximating the relative bypass efficiency and base selectivity upon an AP site, because the steady-state kcat/Km values for nucleotide incorporation opposite both G and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroG with calf thymus DNA pol δ/PCNA were nearly comparable to the pre-steady-state kpol/Kd values for that enzyme in a prior study.18 Caution should be used in extrapolating our kinetic data to a natural AP site, due to the potential limitation of a tetrahydrofuran analogue used as a model of AP site in this study. Whereas the in vitro bypass and miscoding properties of a tetrahydrofuran analogue with Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I or calf thymus DNA polymerase α were reported to closely resemble those of a natural AP site,22 some other reports showed that the mutation properties of a tetrahydrofuran analogue and a natural AP site are different in uninduced E. coli and yeast cells but similar in SOS-induced E. coli.2,23

In comparing data obtained with human B- and Y-family DNA polymerases in this study, the relative efficiency of nucleotide incorporation opposite an AP site was in the order of pol ι> pol η ∼ REV1 > pol δ/PCNA > pol α ∼ pol κ (compared to dCTP incorporation opposite unmodified G) (Tables 2 and 3). In contrast, the relative efficiency of next-base extension from a base inserted opposite an AP site (compared to that for a normal C:G or T:A base pair) was in the approximate order of pol η > pol δ/PCNA > pol κ > pol α (Tables 4 and 5). Interestingly human pol η showed relatively good efficiencies of dATP and dTTP insertion opposite an AP site, nearly comparable to that of C insertion by REV1. The relative efficiency of dATP insertion by pol δ/PCNA was only slightly lower(about 5-fold) than that of C insertion by REV1. Moreover, the two human pols—η and δ/PCNA—appeared to extend fairly well from A incorporated opposite an AP site, with 15- and 150-fold reduced efficiencies (compared to that from normal base pair), respectively, i.e. only 2- and 20-fold less efficient than a well-known extender polymerase, yeast pol ζ (8-fold reduced efficiency, compared to that from normal base pair).24 The preferential next-base extension from A opposite an AP site is also observed with other polymerases, e.g. yeast pol ζ and human pol θ,10,24 which might contribute in part to the A-rule. This finding is also consistent with an earlier study describing predominant A insertion opposite an AP site in the in vitro polymerization products formed by human pol η.25 Taken together, human pols η and δ/PCNA have the potential to generate predominantly A insertions opposite an AP site, although their overall bypass efficiencies appear to be less than that of human A-family polymerase θ.10 Along with our previous results and those of others showing that the human pol η bypasses many types of DNA lesions such as cis-syn thymine dimer, 1,N2-ethenoG, N2- and C8-guanyl adducts of 2-amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoline (IQ), O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl] (Pob)G, and 3-(2'-deoxy-β-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl)pyrimido-[1,2-a]purin-10(3H)-one (M1dG) quite effectively,15,26–29 the present data also indicate the highly versatile bypass capabilities of human pol η opposite a variety of DNA lesions including AP sites and dimeric, ring-closed, minor-groove, and major-groove DNA adducts in vitro.

Only human B-family DNA polymerases α and δ/PCNA—but not Y-family DNA polymerases—obeyed the “A-rule” when selecting a base opposite an AP site (Tables 2 and 3). Although bases other than A can be inserted opposite AP site by human Y-family polymerases, the A-rule might prevail for overall AP site bypass because the A:AP site pair is most efficiently extended by extender polymerases (vide supra). It has been shown that dATP and/or dCTP are frequently inserted opposite a synthetic or natural AP site in yeast cells, depending on the experimental settings,23,30–32 while dATP insertion was predominant opposite a synthetic AP site in a study using human cells.33 In this work, REV1 inserted dCTP efficiently and almost exclusively opposite an AP site, consonant with earlier studies using yeast cell systems,30,34,35 indicating a potential role of eukaryotic REV1 in generating C insertion at an AP site in cells. Pol ι, a highly efficient inserter polymerase opposite an AP site, incorporated all four bases with a relatively low base preference, which may be advantageous in generating diverse base subsititutions. Base selectivity in DNA synthesis by pol ι is peculiar due to the likelihood of differing H-bonding modes including Hoogsteen, wobble, and Watson-Crick base pairs and base stacking plus finger domain interaction, depending on the nature of template bases.36–38 A recent report shows that an AP site and an incoming different nucleotide appear to be well confined in the active site of a crystal structure of pol ι and predispose toward various base substitutions,39 in contrast with Sulfolobus solfataricus Y-family DNA polymerase Dpo4, which showed either looping out of an AP site from DNA helix to result in one base deletion or insertion of A opposite an AP site, depending on the local sequence context.40,41 The property of pol ι to efficiently catalyze diverse base insertions at AP sites may be useful for somatic hypermutation of antibody genes, although where the exact role of pol ι is controversial in studies using POLI-knockout cell lines and POLI-deficient mice.42,43

Human cells are equipped with at least three replicative DNA polymerases-pol α, δ, and ɛ— and five translesion DNA polymerases—η, ι, κ, REV1, and ζ. This categorization is not perfectly applicable for AP lesion bypass. On the basis of our results (Tables 2–5), the heterotetrameric pol δ/PCNA appears to bypass an AP site in both steps, base insertion opposite AP site and the subsequent extension, with slightly reduced efficiencies compared to pol η. These findings may support the catalytic functionality of human pol δ/PCNA as being relatively competent for replicative bypass opposite and following AP lesions, consonant with an earlier report with calf thymus pol δ.19 Although pol ζ has been reported to act as a main extender from nucleotides inserted opposite AP site in yeast cells,24 human pols η and δ/PCNA appear to have some potential to act in part as extenders from a nucleotide, especially A, inserted opposite AP site in human cells. Interestingly the human heterotetramer pol δ can be converted into a heterotrimer, which has the less translesion ability in cells when cells are exposed to high concentrations of exogenous genotoxins.16,44 Considering that numerous AP sites are being produced in cells endogenously without any exposure to exogenous damaging sources, it is conceivable that pol δ (present as a heterotetrameric form) could facilitate replicative bypass upon AP lesions in undamaged cells, without the need to activate DNA damage response pathways.

Cellular roles of individual DNA polymerases in AP lesion bypass have been speculated from studies using plasmid (or chromosome)-based translesion replication and genetically manipulated cellular systems. Most of this work has been done with E. coli and yeast cells and suggests roles for multiple specialized DNA polymerases, e.g. pols II, IV, and V for E. coli 2 and Rev1, Rev3, Rev7, and Rad30 for yeast.30–32 The exact role of eukaryotic pol η in AP lesion bypass is somewhat controversial due to varying results in previous reports using yeast and human cells,23,31,33 although our present study offers evidence for considerable in vitro catalytic abilities of human pol η to cope well with AP sites. Interestingly Pol32, a subunit of a yeast replicative pol δ, is also required in replicative bypass of AP sites in yeast cells.32,45 Moreover, a recent study demonstrated the catalytic ability of yeast replicative pol ɛ in AP site bypass, which is comparable to pol η,46 suggesting a catalytic role of eukaryotic pol ɛ in AP lesion bypass. In this regard, it is remarkable that some replicative DNA polymerases (pols α, δ, ɛ) appear to be required for AP site bypass in human cells.33 The role of human pol α in AP site bypass might be limited because pol α appears to be competent in elongation only from primase-synthesized RNA primers but not from DNA primers (opposite an AP site),47 also observed in our study. Thus, the human pol δ-PCNA complex might play a role in translesion DNA synthesis across an AP site, with its moderate catalytic competency, especially in undamaged cells. Determination of the mutation spectra and rates of replication past AP sites with single or multiple human DNA polymerases using genetically manipulated human cell cultures will be of interest, and sequencing analyses of in vitro polymerization products can also help decipher the mutagenic roles of individual human DNA polymerases in cells.

In conclusion, our results indicate that pols η and δ/PCNA are relatively efficient in translesion DNA synthesis across an AP site in both steps, insertion opposite the lesion and the following extension, while pol ι and REV1 are highly efficient only in the initial insertion step opposite an AP site. Notwithstanding the presence of multiple B- and Y-family DNA polymerases capable of replicative bypass of an AP site, the catalytic propensities of individual polymerases for base selection across an AP site may contribute to the distinct spectrum of mutations induced by AP sites in human cells.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Unlabeled dNTPs and T4 polynucleotide kinase were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). [γ-32P]ATP (specific activity 3,000 Ci/mmol) was purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA). Bio-spin columns were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Oligonucleotides were purchased from Midland Certified Reagents (Midland, TX). Human pol α was purchased from CHIMERx (Milwaukee, WI). Recombinant human pols η, ι, κ, δ, and REV1 were expressed in baculovirus-infected insect cell or E. coli systems and purified as described previously.9,14,48,49

Reaction conditions for polymerization assays

Standard DNA polymerase reactions were performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer containing 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 100 µg ml−1 bovine serum albumin (w/v), and 10% glycerol (v/v) with 100 nM primer-template at 37 °C. NaCl (50 mM) was also included for REV1. Primers (24-mer or 25-mer) were 5′ end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase and annealed with templates (36-mer). All reactions were initiated by the addition of dNTP and MgCl2 (5 mM final concentration) to preincubated enzyme/DNA mixtures.

Primer extension assays and gel electrophoresis

A 32P-labeled primer, annealed to a template, was extended in the presence of single or all four dNTPs. Unless indicated, each reaction was initiated by adding 4 µl of dNTP-Mg2+ solution (final concentrations of 100 µM of each dNTP and 5 mM MgCl2) to a preincubated enzyme/DNA complex (final concentrations of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 nM DNA duplex, 5 mM DTT, 100 µg bovine serum albumin (BSA) ml−1, and 10% glycerol (v/v)) at 37 °C, yielding a total reaction volume of 8 µl. After 10 min, reactions were quenched with a solution of 20 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) in 95% formamide (v/v). Aliquots were separated by electrophoresis on a denaturing gel containing 8.0 M urea and 16% acrylamide (w/v) (from a 19:1 acrylamide:bisacrylamide solution, AccuGel, National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA) with 80 mM Tris-borate buffer (pH 7.8) containing 1 mM EDTA. Gels were exposed to a phosphorimager screen (Imaging Screen K, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The bands (representing extension products of the primer) were visualized with a phosphorimaging system (Bio-Rad, Personal Molecular Imager®, Hercules, CA) using the manufacturer’s Quantity One Software.

Steady-state reactions

A 32P-labeled primer, annealed to a template, was extended in the presence of increasing concentrations of a single dNTP. The molar ratio of primer/template to enzyme was at least 10:1 except for some cases with pol α and REV1 (up to 10:3 for assays with AP site). Enzyme concentrations and reaction times were chosen so that maximal product formation would be ≤ 20% of the substrate concentration. The primer-template was extended with dNTP in the presence of 0.1–5 nM enzyme for 5 or 10 min. All reactions (8 µl) were done at ten dNTP concentrations and quenched with 9 volumes of a solution of 20 mM EDTA in 95% formamide (v/v). Products were resolved using a 16% polyacrylamide (w/v) electrophoresis gel containing 8.0 M urea and quantitated by phosphorimaging analysis using a Bio-Rad Personal Molecular Imager® instrument and Quantity One software. Graphs of product formation vs dNTP concentration were fit using nonlinear regression (hyperbolic fits) in GraphPad Prism Version 3.0 (San Diego, CA) for the determination of kcat and Km values.

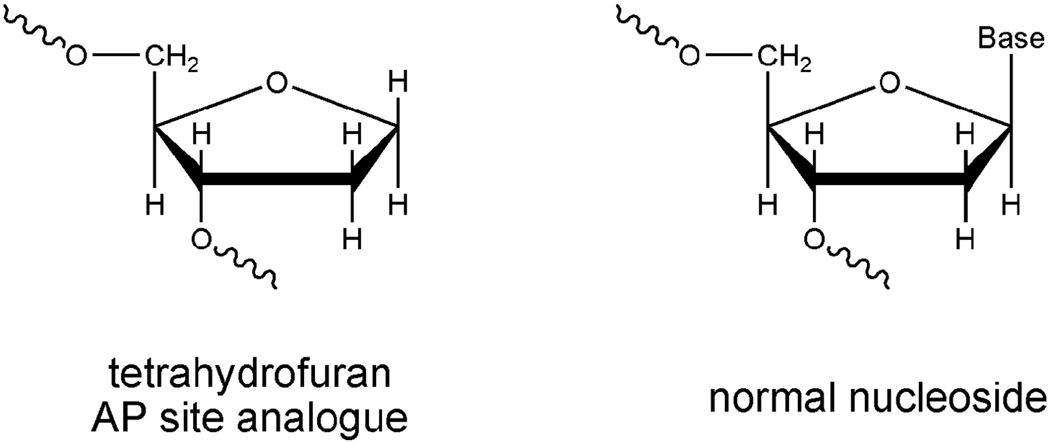

Fig. 1.

Abasic (AP) site used in this work. Structures of tetrahydrofuran analogue of AP site and normal nucleoside are compared.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (KRF-2007-331-E00041) (to J.-Y. C) and United States Public Health Service (USPHS) Grant R01 ES010375 (to F. P. G.).

Abbreviations used

- A

adenine

- C

cytosine

- G

guanine

- T

thymine

- dNTP

deoxynucleoside triphosphate

- pol

DNA polymerase

- AP

apurinic (apyrimidinic)

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- DTT

dithiothreitol

References

- 1.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, Schultz RA, Ellenberger T. DNA Repair And Mutagenesis. 2nd ed. Washington, D. C.: American Society for Microbiology Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kroeger KM, Goodman MF, Greenberg MM. A comprehensive comparison of DNA replication past 2-deoxyribose and its tetrahydrofuran analog in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5480–5485. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boiteux S, Guillet M. Abasic sites in DNA: repair and biological consequences in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2004;3:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loeb LA, Monnat RJ., Jr DNA polymerases and human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrg2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang W, Woodgate R. What a difference a decade makes: insights into translesion DNA synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:15591–15598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704219104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Dupradeau FY, Case DA, Turner CJ, Stubbe J. DNA oligonucleotides with A, T, G or C opposite an abasic site: structure and dynamics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:253–262. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuniasse P, Fazakerley GV, Guschlbauer W, Kaplan BE, Sowers LC. The abasic site as a challenge to DNA polymerase. A nuclear magnetic resonance study of G, C and T opposite a model abasic site. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;213:303–314. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nair DT, Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S, Aggarwal AK. Rev1 employs a novel mechanism of DNA synthesis using a protein template. Science. 2005;309:2219–2222. doi: 10.1126/science.1116336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi JY, Guengerich FP. Kinetic analysis of translesion synthesis opposite bulky N2- and O6-alkylguanine DNA adducts by human DNA polymerase REV1. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:23645–23655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801686200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seki M, Masutani C, Yang LW, Schuffert A, Iwai S, Bahar I, Wood RD. High-efficiency bypass of DNA damage by human DNA polymerase Q. EMBO J. 2004;23:4484–4494. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haracska L, Washington MT, Prakash S, Prakash L. Inefficient bypass of an abasic site by DNA polymerase eta. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:6861–6866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haracska L, Unk I, Johnson RE, Phillips BB, Hurwitz J, Prakash L, Prakash S. Stimulation of DNA synthesis activity of human DNA polymerase kappa by PCNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:784–791. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.3.784-791.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson RE, Washington MT, Haracska L, Prakash S, Prakash L. Eukaryotic polymerases iota and zeta act sequentially to bypass DNA lesions. Nature. 2000;406:1015–1019. doi: 10.1038/35023030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi JY, Guengerich FP. Adduct size limits efficient and error-free bypass across bulky N2-guanine DNA lesions by human DNA polymerase eta. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;352:72–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi JY, Chowdhury G, Zang H, Angel KC, Vu CC, Peterson LA, Guengerich FP. Translesion synthesis across O6-alkylguanine DNA adducts by recombinant human DNA polymerases. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:38244–38256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng X, Zhou Y, Zhang S, Lee EY, Frick DN, Lee MY. DNA damage alters DNA polymerase delta to a form that exhibits increased discrimination against modified template bases and mismatched primers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:647–657. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindahl T, Nyberg B. Rate of depurination of native deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1972;11:3610–3618. doi: 10.1021/bi00769a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Einolf HJ, Guengerich FP. Kinetic analysis of nucleotide incorporation by mammalian DNA polymerase δ. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:16316–16322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001291200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mozzherin DJ, Shibutani S, Tan CK, Downey KM, Fisher PA. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen promotes DNA synthesis past template lesions by mammalian DNA polymerase delta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:6126–6131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauss BS. The 'A rule' of mutagen specificity: a consequence of DNA polymerase bypass of non-instructional lesions? Bioessays. 1991;13:79–84. doi: 10.1002/bies.950130206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson KA. Conformational coupling in DNA polymerase fidelity. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1993;62:685–713. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.003345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shibutani S, Takeshita M, Grollman AP. Translesional synthesis on DNA templates containing a single abasic site. A mechanistic study of the "A rule". J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:13916–13922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otsuka C, Sanadai S, Hata Y, Okuto H, Noskov VN, Loakes D, Negishi K. Difference between deoxyribose- and tetrahydrofuran-type abasic sites in the in vivo mutagenic responses in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:5129–5135. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haracska L, Unk I, Johnson RE, Johansson E, Burgers PM, Prakash S, Prakash L. Roles of yeast DNA polymerases delta and zeta and of Rev1 in the bypass of abasic sites. Genes Dev. 2001;15:945–954. doi: 10.1101/gad.882301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kokoska RJ, McCulloch SD, Kunkel TA. The efficiency and specificity of apurinic/apyrimidinic site bypass by human DNA polymerase eta and Sulfolobus solfataricus Dpo4. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:50537–50545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi JY, Zang H, Angel KC, Kozekov ID, Goodenough AK, Rizzo CJ, Guengerich FP. Translesion synthesis across 1,N2-ethenoguanine by human DNA polymerases. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006;19:879–886. doi: 10.1021/tx060051v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi JY, Stover JS, Angel KC, Chowdhury G, Rizzo CJ, Guengerich FP. Biochemical basis of genotoxicity of heterocyclic arylamine food mutagens: Human DNA polymerase η selectively produces a two-base deletion in copying the N2-guanyl adduct of 2-amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoline but not the C8 adduct at the NarI G3 site. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:25297–25306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605699200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson RE, Washington MT, Prakash S, Prakash L. Fidelity of human DNA polymerase η. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:7447–7450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stafford JB, Eoff RL, Kozekova A, Rizzo CJ, Guengerich FP, Marnett LJ. Translesion DNA synthesis by human DNA polymerase eta on templates containing a pyrimidopurinone deoxyguanosine adduct, 3-(2'-deoxy-beta-d-erythro-pentofuranosyl)pyrimido-[1,2-a]purin-10(3H)-one. Biochemistry. 2009;48:471–480. doi: 10.1021/bi801591a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kow YW, Bao G, Minesinger B, Jinks-Robertson S, Siede W, Jiang YL, Greenberg MM. Mutagenic effects of abasic and oxidized abasic lesions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6196–6202. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao B, Xie Z, Shen H, Wang Z. Role of DNA polymerase eta in the bypass of abasic sites in yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:3984–3994. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pages V, Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S. Mutational specificity and genetic control of replicative bypass of an abasic site in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:1170–1175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711227105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Avkin S, Adar S, Blander G, Livneh Z. Quantitative measurement of translesion replication in human cells: evidence for bypass of abasic sites by a replicative DNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:3764–3769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062038699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibbs PE, McDonald J, Woodgate R, Lawrence CW. The relative roles in vivo of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pol eta, Pol zeta, Rev1 protein and Pol32 in the bypass and mutation induction of an abasic site, T-T (6-4) photoadduct and T-T cis-syn cyclobutane dimer. Genetics. 2005;169:575–582. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.034611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Auerbach P, Bennett RA, Bailey EA, Krokan HE, Demple B. Mutagenic specificity of endogenously generated abasic sites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosomal DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:17711–17716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504643102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nair DT, Johnson RE, Prakash S, Prakash L, Aggarwal AK. Replication by human DNA polymerase-iota occurs by Hoogsteen base-pairing. Nature. 2004;430:377–380. doi: 10.1038/nature02692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi JY, Lim S, Eoff RL, Guengerich FP. Kinetic analysis of base-pairing preference for nucleotide incorporation opposite template pyrimidines by human DNA polymerase iota. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;389:264–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirouac KN, Ling H. Structural basis of error-prone replication and stalling at a thymine base by human DNA polymerase iota. EMBO J. 2009;28:1644–1654. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nair DT, Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S, Aggarwal AK. DNA synthesis across an abasic lesion by human DNA polymerase iota. Structure. 2009;17:530–537. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ling H, Boudsocq F, Woodgate R, Yang W. Snapshots of replication through an abasic lesion; structural basis for base substitutions and frameshifts. Mol. Cell. 2004;13:751–762. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fiala KA, Hypes CD, Suo Z. Mechanism of abasic lesion bypass catalyzed by a Y-family DNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:8188–8198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610718200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faili A, Aoufouchi S, Flatter E, Gueranger Q, Reynaud CA, Weill JC. Induction of somatic hypermutation in immunoglobulin genes is dependent on DNA polymerase iota. Nature. 2002;419:944–947. doi: 10.1038/nature01117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McDonald JP, Frank EG, Plosky BS, Rogozin IB, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Woodgate R, Gearhart PJ. 129-derived strains of mice are deficient in DNA polymerase iota and have normal immunoglobulin hypermutation. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:635–643. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang S, Zhou Y, Trusa S, Meng X, Lee EY, Lee MY. A novel DNA damage response: rapid degradation of the p12 subunit of DNA polymerase δ. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:15330–15340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610356200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Auerbach PA, Demple B. Roles of Rev1, Pol zeta, Pol32 and Pol eta in the bypass of chromosomal abasic sites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutagenesis. 2010;25:63–69. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gep045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sabouri N, Johansson E. Translesion synthesis of abasic sites by yeast DNA polymerase ɛ. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:31555–31563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.043927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zerbe LK, Goodman MF, Efrati E, Kuchta RD. Abasic template lesions are strong chain terminators for DNA primase but not for DNA polymerase alpha during the synthesis of new DNA strands. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12908–12914. doi: 10.1021/bi991075m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi JY, Guengerich FP. Kinetic evidence for inefficient and error-prone bypass across bulky N2-guanine DNA adducts by human DNA polymerase ι. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:12315–12324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi JY, Angel KC, Guengerich FP. Translesion synthesis across bulky N2-alkyl guanine DNA adducts by human DNA polymerase κ. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:21062–21072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602246200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]