Abstract

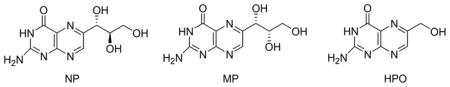

Dihydroneopterin aldolase (DHNA) catalyzes the conversion of 7,8-dihydroneopterin (DHNP) to 6-hydroxymethyl-7,8-dihydropterin (HP) in the folate biosynthetic pathway. There are four conserved active site residues at the active site, E22, Y54, E74, and K100 in Staphylococcus aureus DHNA (SaDHNA), corresponding to E21, Y53, E73, and K98 in Escherichia coli DHNA (EcDHNA). The functional roles of the conserved glutamate and lysine residues have been investigated by site-directed mutagenesis in this work. E22 and E74 of SaDHNA and E21, E73, and K98 of EcDHNA were replaced by alanine. K100 of SaDHNA was replaced by alanine and glutamine. The mutant proteins were characterized by equilibrium binding, stopped-flow binding, and steady-state kinetic analyses. For SaDHNA, none of the mutations except E74A caused dramatic changes in the affinities of the enzyme for the substrate or product analogues or the rate constants. The Kd values for SaE74A were estimated to be >3000 μM, suggesting that the Kd values of the mutant is at least 100 times those of the wild-type enzyme. For EcDHNA, the E73A mutation caused increases in the Kd values for the substrate or product analogues neopterin (MP), monapterin (NP), and 6-hydroxypterin (HPO) by factors of 340, 160, and 5600, respectively, relative to those of the wild-type enzyme. The K98A mutation caused increases in the Kd values for NP, MP, and HPO by factors of 14, 3.6, and 230, respectively. The E21A mutation caused increases in the Kd values for NP and HPO by factors of 2.2 and 42, respectively, but a decrease in the Kd value for MP by a factor of 3.3. The E22 (E21) and K100 (K98) mutations caused decreases in the kcat values by factors of 1.3×104 to 2×104. The E74 (E73) mutation caused decreases in the kcat values by factors of ~10. The results suggested that E74 of SaDHNA and E73 of EcDHNA are important for substrate binding, but their roles in catalysis are minor. In contrast, E22 and K100 of SaDHNA are important for catalysis, but their roles in substrate binding are minor. On the other hand, E21 and K98 of EcDHNA are important for both substrate binding and catalysis.

Dihydroneopterin aldolase (DHNA) catalyzes the conversion of the 7,8-dihydroneopterin (DHNP) to 6-hydroxymethyl-7,8-dihydropterin (HP) in the folate biosynthetic pathway, one of principal targets for developing antimicrobial agents (1–3). Folate cofactors are essential for life (4). Most microorganisms must synthesize folates de novo. In contrast, mammals cannot synthesize folates because of the lack of three enzymes in the middle of the folate pathway and obtain folates from the diet. DHNA is the first of the three enzymes that are absent in mammals and therefore an attractive target for developing antimicrobial agents (5).

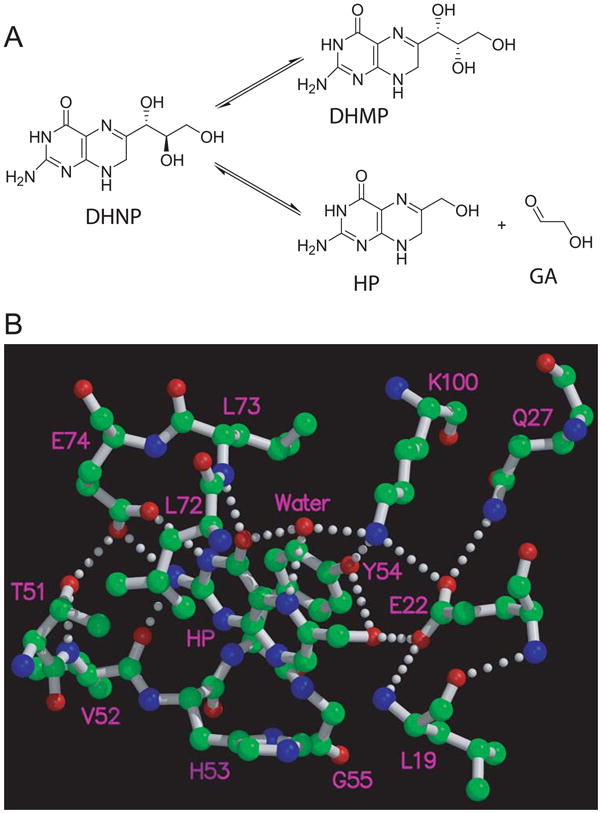

DHNA is a unique aldolase in two respects. First, DHNA requires neither the formation of a Schiff base between the substrate and enzyme nor metal ions for catalysis (6). Aldolases can be divided into two classes based on their catalytic mechanisms (7, 8). Class I aldolases require the formation of a Schiff base between an amino group of the enzyme and the carbonyl of the substrate, whereas class II aldolases require a Zn2+ ion at their active sites for catalysis. The proposed catalytic mechanism for DHNA is similar to that of class I aldolases, but the Schiff base is embedded in the substrate. Secondly, in addition to the aldolase reaction, DHNA also catalyzes the epimerization at the 2′-carbon of DHNP to generate 7,8-dihydromonapterin (DHMP) (Figure 1A) (9), but the biological function of the epimerase reaction is not known at present. Interestingly, DHNAs from Staphylococcus aureus (SaDHNA) and E. coli (EcDHNA) have significant differences in their binding and catalytic properties (Wang et al., unpublished).

Figure 1. The Reactions catalyzed by DHNA (A) and the interactions of HP with SaDHNA (B).

The interactions between HP and SaDHNA are drawn on the basis of the crystal structure of SaDHNA in complex with HP (10). The hydrogen bonds are drawn in dotted lines. Oxygen atoms are in red, nitrogen atoms in blue, and carbon atoms in green. Panel B was prepared with the programs Molscript (20) and Raster3D (21, 22).

DHNA consists of eight identical subunits. The atomic structures of SaDHNA (5, 10), Mycobacterium tuberculosis DHNA (11), and Arabidopsis thaliana DHNA (12) have been determined by X-ray crystallography. The octameric structures look like two stacked donuts with a large hole in the middle, ~13 Å in SaDHNA. Each donut consists of four subunits. There are eight active sites, all formed by residues from two adjacent subunits. At the active sites, there are four conserved residues that interact with the bound product HP as revealed by the crystal structures (10, 11) (Figure 1B). These four residues are E22, Y54, E74, and K100 in SaDHNA, corresponding to E21, Y53, E73, and K98 in EcDHNA, respectively (Figure 2). Previously we showed that the conserved tyrosine residue plays a critical role in DHNA catalysis (13). Substitution of the conserved tyrosine residue in SaDHNA or EcDHNA with phenylalanine turned the target enzyme into an oxygenase. In this paper, we describe a site-directed mutagenesis study of the functional roles of the other conserved, active-site residues in SaDHNA and EcDHNA. The results provide important insight into the catalytic mechanisms of the enzymes and valuable information for designing inhibitors targeting these enzymes.

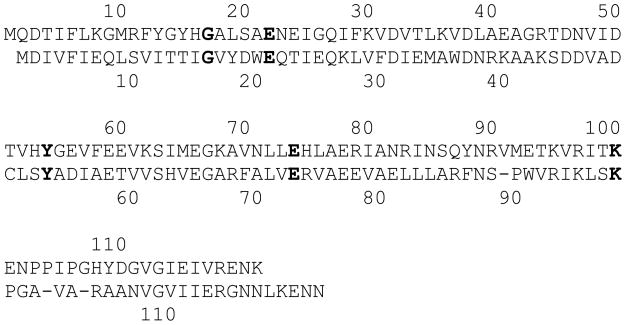

Figure 2. Amino acid sequence alignment of SaDHNA and EcDHNA.

The amino acid sequence of EcDHNA is aligned with that of SaDHNA with gaps inserted on the basis of the crystal structure of SaDHNA. Residue numbering for SaDHNA is above the amino acid sequence, and that for EcDHNA is below the amino acid sequence. The strictly conserved residues, on the basis of the sequence alignment of 67 DHNAs (not shown), are highlighted in bold.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

6-Hydroxymethylpterin (HPO), 6-Hydroxymethyl-7,8-dihydropterin (HP), 7,8-dihydro-D-neopterin (DHNP), 7,8-dihydro-L-monapterin (DHMP), D-neopterin (NP), and L-monapterin (MP) were purchased from Schircks Laboratories. Pfu DNA polymerase was purchased from Strategene. Other chemicals were from Sigma or Aldrich.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis and Protein Purification

The site-directed mutants were made by a PCR-based method using high-fidelity pfu DNA polymerase according to a protocol developed by Stratagene. The forward and reverse primers for the PCR-based mutagenesis experiments are listed in Table 1. The mutants were selected by DNA sequencing. In order to ensure that there were no unintended mutations in the mutants, the entire coding sequences of the mutated genes were determined. The S. aureus enzymes contained extra seven residues (MHHHHHH) at the N-terminus serving as a His-tag for purification.

Table 1.

The Forward and Reverse Primers for the PCR-Based Mutagenesis Experiments

| Mutanta | Primerb |

|---|---|

| SaE22A | 5′-GGTGCTTTATCAGCTGCAAATGAAATAGGGCAAATTTTC-3′ |

| 5′-GAAAATTTGCCCTATTTCATTTGCAGCTGATAAAGCACC-3 | |

| SaE74A | 5′-GCCGTTAATTTACTTGCGCATCTAGCTGAACGTATTGC-3′ |

| 5′-GCAATACGTTCAGCTAGATGCGCAAGTAAATTAACGGC-3′ | |

| SaK100A | 5′-GAAACGAAAGTGAGAATCACTGCAGAAAACCCACCGATTCCG-3′ |

| 5′-CGGAATCGGTGGGTTTTCTGCAGTGATTCTCACTTTCGTTTC-3′ | |

| SaK100Q | 5′-CGAAAGTGAGAATCACTCAAGAAAACCCACCGATTCC-3′ |

| 5′-GGAATCGGTGGGTTTTCTTGAGTGATTCTCACTTTC G-3′ | |

| EcE21A | 5′-GTGTTTACGACTGGGCACAGACCATCGAACAG-3′ |

| 5′-CTGTTCGATGGTCTGTGCCCAGTCGTAAACAC-3′ | |

| EcE73A | 5′-GCGCTGGTGGCACGCGTGGCTG-3′ |

| 5′-CAGCCACGCGTGCCACCAGCGC-3′ | |

| EcK98A | 5′-CGTATCAAACTCAGCGCGCCAGGCGCAGTGG-3′ |

| 5′-CCACTGCGCCTGGCGCGCTGAGTTTGATACG-3′ | |

SaE22A, SaE74A, and SaK100A are mutants of SaDHNA in which E22, E74, and K100 are replaced by alanine respectively. SaK100Q is a SaDHNA mutant with K100 replaced by glutamine. EcE21A, EcE73A, and EcK98A are mutants of EcDHNA in which E21, E73, and K98 are replaced by alanine respectively.

The forward primers are listed first with the mutations underlined. The mutations in the reverse primers are not indicated.

EcE21A, EcE73A, and EcK98A, which were mutants of EcDHNA with E21, E73, and K98 replaced by alanine respectively, were purified by a DEAE-cellulose column followed by a Bio-Gel A-0.5 m gel column. Briefly, the E. coli cells were re-suspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 (buffer A) and lysed by a French press. The lysate was centrifuged for 20 min at ~27,000 g. The supernatant was loaded onto a DEAE-cellulose column equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with buffer A until OD280 of the effluent was <0.05 and eluted with a 0–500 mM linear NaCl gradient in buffer A. Fractions containing DHNA were identified by OD280 and SDS-PAGE and concentrated to ~15 mL by an Amicon concentrator using a YM30 membrane. The concentrated protein solution was centrifuged, and the supernatant was applied to a Bio-Gel A-0.5 m gel column equilibrated with buffer A containing 150 mM NaCl. The column was developed with the same buffer. Fractions from the gel filtration column were monitored by OD280 and SDS-PAGE. Pure DHNA fractions were pooled and concentrated to 10–20 mL. The concentrated DHNA was dialyzed against 5 mM TrisHCl, pH 8.0, lyophilized, and stored at −80 °C.

SaE22A, SaE74A, SaK100A, and SaK100Q, which were mutants of SaDHNA, were purified to homogeneity by a Ni-NTA column followed by a Bio-Gel A-0.5 m gel column. Briefly, the cells were harvested and lysed as described above except that buffer was replaced with 50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, pH 8.0 (buffer B) and 10 mM imidazole. The lysate was loaded onto the Ni-NTA column equilibrated with buffer B containing 10 mM imidazole. The column was washed with 20 mM imidazole in buffer B and eluted with 250 mM imidazole in buffer B. The concentrated protein was further purified by gel filtration, concentrated again, dialyzed, lyophilized, and stored at −80 °C as described earlier.

Equilibrium Binding Studies

The procedures for the equilibrium binding studies of DHNAs were essentially the same as previously described for the similar studies of 6-hydroxymethyl-7,8-dihydropterin pyrophosphokinase using a Spex FluoroMax-2 fluorometer (14, 15). Briefly, proteins and ligands were all dissolved in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3 and the titration experiments were performed in a single cuvette at 24 °C. The equilibrium binding experiments were performed by titrating either ligands or the proteins. In ligand titrations, fluorescence intensities were measured at an emission wavelength of 446 nm with a slit of 5 nm. The excitation wavelength and slit were 400 nm and 1 nm, respectively. A set of control data was obtained in the absence of the protein. The data set obtained in the absence of the protein was then subtracted from the corresponding data set obtained in the presence of the protein after correcting inner filter effects. The Kd value was obtained by nonlinear least square fitting of the titration data as previously described (14). All Kd values for SaDHNA mutants except that of SaE22A for HPO were obtained by titrating ligands.

In protein titration experiments, a ligand solution was titrated with a stock solution of one of the mutant proteins. Fluorescence intensities were measured at an emission wavelength of 430 nm and an excitation wavelength of 330 nm. The emission and excitation slits were both 5 nm. A control titration experiment was performed in the absence of the ligand. The control data set obtained in the absence of HP was subtracted from the corresponding data set obtained in the presence of the ligand. The Kd value was obtained by nonlinear least square fitting of the titration data as previously described (14). All Kd values for EcDHNA mutants and that of SaE22A for HPO were obtained by titrating proteins.

Stopped-Flow Analysis

Stopped-flow experiments were performed on an Applied Photophysics SX.18MV-R stopped-flow spectrofluorometer at 25 °C. One syringe contained one of the mutant proteins, and the other contained NP, MP, HP or HPO. The protein concentrations were 1 or 2 μM, and the ligand concentrations ranged from 5–60 μM. All concentrations were those after the mixing of the two syringe solutions. Fluorescence traces for NP, MP and HPO were obtained with an excitation wavelength of 360 nm and a filter with a cutoff of 395 nm for emission. Fluorescence traces for HP were obtained with an excitation wavelength of 330 nm and the same filter for emission. Apparent rate constants were obtained by nonlinear squares fitting of the data to a single exponential equation and were re-plotted against the ligand concentrations. The association and dissociation rate constants were obtained by linear regression of the apparent rate constants vs. ligand concentration data.

Steady-State Kinetic Assay

All components were dissolved in a buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 5 mM DTT, pH 8.3. The reactions were initiated by mixing with the mutant enzymes and quenched with 1 N HCl. The quenched reaction mixtures were processed as previously described (9). Briefly, the reaction mixtures (115 μl each) were mixed with 50 μl 1% I2 (w/v) and 2% (w/v) KI in 1 N HCl for 5 min at room temperature to oxidize the pterin compounds. Excess iodine was reduced by mixing with 25 μl 2% ascorbic acid (w/v). The samples were then centrifuged at room temperature for 5 min using a microcentrifuge. The oxidized reactant and products in the supernatants were separated by HPLC using a Vydac RP18 column. The column was equilibrated with 20 mM NaH2PO4 made with MilliQ water and eluted at the flow rate of 0.8 ml/min with the same solution. The oxidized reactant and products were quantified by online fluorometry with excitation and emission wavelengths of 365 and 446 nm, respectively. High concentrations of the mutant enzymes, ranging 1–20 μM, were used in the kinetic assays because of their low activities. When the substrate concentrations were in large excess of the enzyme, the normal Michaelis-Menten equation was used to obtain kinetic constants by nonlinear least square regression. When the enzyme concentration was comparable to the substrate concentrations because of the extremely low activity of the enzyme, a modified steady state kinetic equation (Equation 1) (16) was used to evaluate kinetic constants.

| (1) |

where Et and St are the total enzyme and substrate concentrations, respectively, kcat and Km have the usual meanings.

RESULTS

Binding Studies

Previously we established the thermodynamic and kinetic framework for the structure-function studies of SaDHNA and EcDHNA by equilibrium measurements and stopped-flow and quench-flow analyses (Wang et al., unpublished). A similar strategy was used for the characterization of the site-directed mutants. The binding steps were mimicked with the substrate and product analogues NP, MP, and HPO. The difference between the substrate and product analogues and the corresponding substrate and products is that between C7 and N8 is a double bond in the analogues and a single bond in the substrate and products. NP, MP, and HPO are excellent substrate and product analogues for the study of binding steps for two reasons. (i) According to the crystal structure of the complex SaDHNA and HP (10), there is no hydrogen bond between N7 of HP and the protein. By implication, there may not be a hydrogen bond between N7 of DHNP or DHMP to the protein. Therefore, the reduced and oxidized pterins may have similar affinities for the enzymes. (ii) Indeed, HP and HPO have similar affinities for the enzymes (Wang et al., unpublished). The Kd values were measured by equilibrium binding experiments using fluorometry by either titrating the ligands or the proteins. Representative results of the equilibrium binding studies are shown in Figures 3 and 4. The association and dissociation rate constants were determined by kinetic binding experiments using stopped-flow fluorometry. A representative result of the kinetic binding studies is shown in Figures 5. For technical reasons, the binding constants for SaE74A and the association and dissociation rate constants for EcE73A could not be measured. The complete results of the binding studies are summarized in Tables 2 and 3 for SaDHNA and EcDHNA, respectively. In general, the thermodynamic data are in good agreement with the kinetic data, as the measured Kd values are in good agreement with those calculated from the association and dissociation rate constants. High Kd values are, for the most part, due to high dissociation rate constants. For SaDHNA, none of the mutations except E74A caused dramatic changes in the affinities of the enzyme for the substrate or product analogues or the rate constants. The Kd values for SaE74A were estimated to be >3000 μM, suggesting that the Kd values of the mutant is at least 100 times those of the wild-type enzyme. The results indicated that for SaDHNA, of the three conserved residues, only E74 is important for the binding of the analogues. For EcDHNA, similarly, the mutation of E73, corresponding E74 in SaDHNA, had the most dramatic effects on the ligand binding. The E73A mutation caused increases in the Kd values for the binding of NP, MP and HPO by factors of 340, 160, and 5600, respectively, relative to those of the wild-type enzyme, suggesting that E73 is critically important for the binding of these substrate or product analogues. In addition, the K98A mutation caused increases in the Kd values for the binding of NP, MP, and HPO by factors of 14, 3.6, and 230, respectively, suggesting that K98 is important for the binding of these ligands, particularly for the binding of HPO and NP. The E21A mutation caused increases in the Kd values for the binding of NP and HPO by factors of 2.2 and 42, respectively, but a decrease in the Kd value for the binding of MP by a factor of 3.3, suggesting that E21 is only important for the binding of HPO.

Figure 3. Binding of MP to SaE22A at equilibrium.

A 2 mL solution containing 10 μM SaE22A in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, was titrated with MP by adding aliquots of a 1.03 mM MP stock solution at 24 °C. The final enzyme concentration was 9.3 μM. The top axis indicates the MP concentrations during the titration. A set of control data was obtained in the absence of the enzyme and was subtracted from the corresponding data set obtained in the presence of the enzyme. The solid line was obtained by nonlinear least-squares regression as previously described (14).

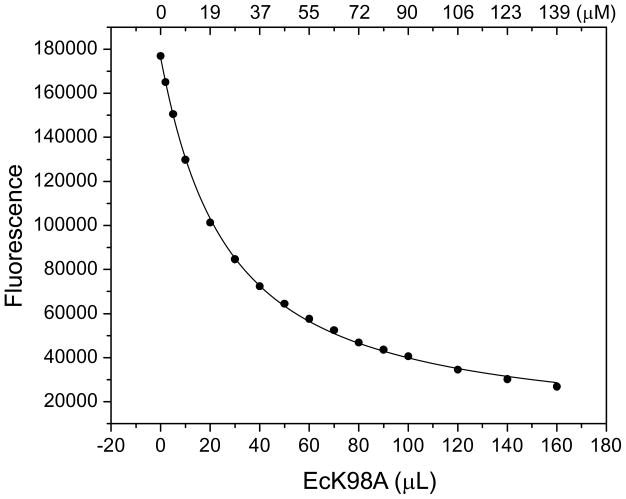

Figure 4. Binding of HPO to EcK98A at equilibrium.

A 2 mL solution containing 5 μM HPO in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, was titrated with EcK98A by adding aliquots of a 1.9 mM EcK98A stock solution at 24 °C. The final HPO concentration was 4.6 μM. The top axis indicates the EcK98A concentrations during the titration. A set of control data was obtained in the absence of HPO and was subtracted from the corresponding data set obtained in the presence of HPO. The solid line was obtained by nonlinear least-squares regression as previously described (14).

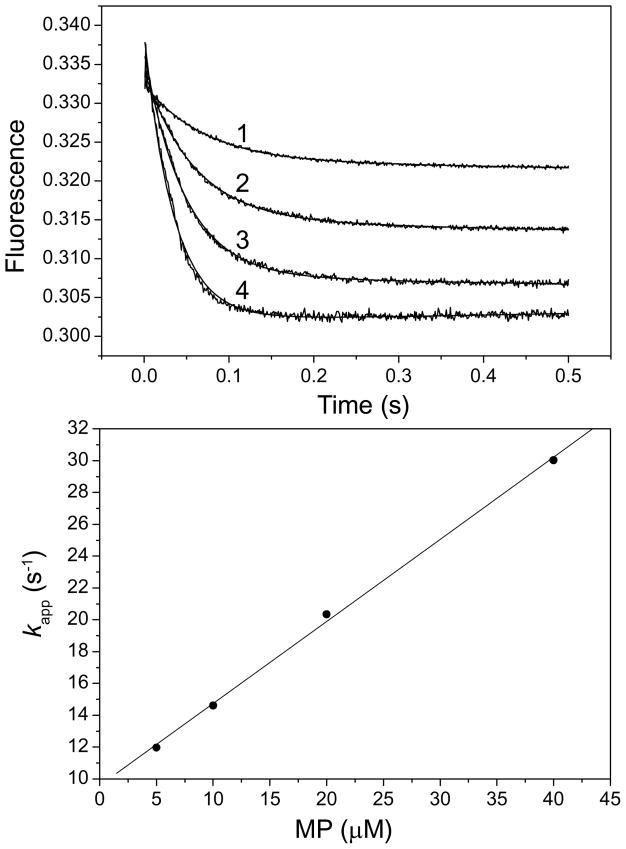

Figure 5. Stopped-flow fluorometric analysis of the binding of HPO to SaE22A.

The concentration of SaE22A was 1 μM, and the concentrations of HPO were 5, 10, 20 and 40 μM for traces 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. All concentrations were those immediately after the mixing of the two syringe solutions. Both SaE22A and HPO were dissolved in 100 mM 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3. The fluorescent signals were rescaled so that they could be fitted into the figure with clarity. The solid lines were obtained by nonlinear regression as described in the Experimental Procedures section. Panel B is a replot of the apparent rate constants vs. the HPO concentrations. The solid line was obtained by linear regression.

Table 2.

Binding Constants of SaDHNA and Site-Directed Mutantsa

| SaDHNA | SaE22A | SaE74A | SaK100A | SaK100Q | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Kd (μM) | 18±2 | 13±0.6 | > 4000 | 6.9±0.7 | 11±0.3 |

| k1 (M−1s−1) | (2.4±0.1)×105 | (2.9±0.1)×105 | n.d.b | (2.2±0.1)×105 | (1.9±0.1)×105 | |

| k−1 (s−1) | 4.5±0.1 | 4.0±0.1 | n.d.b | 1.2±0.1 | 2.0±0.1 | |

| MP | Kd (μM) | 13±1 | 11±0.9 | >3000 | 9.1±0.6 | 13±1 |

| k1 (M−1s−1) | (2.9±0.2)×105 | (3.1±0.1)×105 | n.d.b | (2.7±0.1)×105 | (2.8±0.1) ×105 | |

| k−1 (s−1) | 4.2±0.2 | 4.0±0.1 | n.d.b | 2.1±0.1 | 4.3±0.1 | |

| HPO | Kd (μM) | 24±0.2 | 17±2 | >6000 | 6.0±0.1 | 8.8±0.4 |

| k1 (M−1s−1) | (4.5±0.2)×105 | (5.6±0.3)×105 | n.d.b | (6.4±0.3)×105 | (6.8±0.4)×105 | |

| k−1 (s−1) | 10±0.5 | 10±0.2 | n.d.b | 5.8±0.3 | 5.8±0.1 | |

Both the wild-type SaDHNA and mutants have a His-tag (MHHHHHH) at the N-terminus. We have shown previously that the His-tag has no effects on the binding and catalytic properties of the enzyme. The chemical structures of the measured compounds are as follows.

n.d.: not determined.

Table 3.

Binding Constants of EcDHNA and Site-Directed Mutants

| EcDHNA | EcE21A | EcE73A | EcK98A | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Kd (μM) | 0.77±0.06 | 1.7±0.01 | 260±40 | 11±0.3 |

| k1 (M−1s−1) | (3.2±0.2)×105 | (4.6±0.2)×105 | n.d.a | (6.6±0.1)×105 | |

| k−1 (s−1) | 0.29±0.03 | 0.82±0.02 | n.d. | 7.2±0.3 | |

| MP | Kd (μM) | 2.6±0.06 | 0.80±0.01 | 420±20 | 9.4±0.09 |

| k1 (M−1s−1) | (2.6±0.1)×105 | (4.3±0.2)×105 | n.d. | (9.1±0.4)×105 | |

| k−1 (s−1) | 0.58±0.03 | 0.47±0.02 | n.d. | 9.1±0.6 | |

| HPO | Kd (μM) | 0.10±0.007 | 4.2±0.01 | 560±20 | 23±2 |

| k1 (M−1s−1) | (5.5±0.4)×105 | (1.4±0.1)×106 | n.d. | (1.2±0.1)×106 | |

| k−1 (s−1) | 0.062±0.006 | 6.3±0.2 | n.d. | 27±1 | |

n.d.: not determined.

Steady-State Kinetic Studies

The catalytic properties of the mutants were determined by steady-state kinetic measurements. Because the reactions were slow, no quench-flow apparatus was needed. For technical reasons, mainly because of the solubility limits of DHNP and DHMP, only kcat/Km could be estimated for SaF74A. Also, only kcat could be estimated for SaK100Q, because the fluorescence of some unknown small molecules associated with the protein preparation caused significant errors in the reaction rates at low substrate concentrations. The steady-state kinetic parameters of the SaDHNA and EcDHNA mutants are summarized in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. For SaDHNA, the E22A mutation caused a decrease in kcat by a factor of 4.8×103 with DHNP as the substrate and 1.5×103 with DHMP as the substrate, in comparison with those of the wild-type enzyme. The K100A and K100Q mutations caused decreases in kcat by factors of 2×104 and 2.8×103, respectively, with DHNP as the substrate, and by factors of 2×103 and 1.8×103, respectively, with DHMP as the substrate. The effects of the two mutations were very similar. The results suggest that both E22 and K100 are important for catalysis. The kcat value of SaE74A mutant could not be determined, but its kcat/Km value could be estimated from the linear part of the reaction rate vs. substrate concentration curve, which decreased by a factor of 570 with DHNP as the substrate and a factor of 23 with DHMP as the substrate. The decreases in the kcat/Km values are probably largely due to the increases in Km, considering that the mutation caused dramatic decreases in the affinities of the enzyme for all substrate or product analogues. The result suggests that E74 plays no great role in catalysis. This was confirmed by the mutation of the corresponding residue (E73) of EcDHNA. The E73A mutation of EcDHNA caused a decrease in kcat by only a factor of ~10. The EcE21A and EcK98A mutants behaved like the corresponding SaDHNA mutants (SaE22A and SaK100A) in terms of their kcat values. Thus, the kcat of EcE21A decreased by a factor of 1.3×103 with DHNP as the substrate and by a factor of 3.9×103 with DHMP as the substrate, in comparison with those of the wild-type E. coli enzyme. The kcat of EcK98A decreased by a factor of 1.9×104 with DHNP as the substrate and by a factor of 1.7×104 with DHMP as the substrate. The results suggest that the conserved glutamate and lysine residues both are important as well for the catalysis by EcDHNA.

Table 4.

Steady State Kinetic Constants of SaDHNA and Site-Directed Mutants

| SaDHNA | SaE22A | SaE74A | SaK100A | SaK100Q | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHNP | kcat (s−1) | 0.045±0.002 | (9.3±0.4)×10−6 | n.d.a | (2.2±0.1)×10−6 | (1.6±0.3)×10−5 |

| Km (μM) | 4.6±0.3 | 3.9±0.6 | n.d. | 5.8±1 | n.d. | |

| kcat/Km (s−1M−1) | 9.7 | 2.4×10−3 | (1.7±0.09)×10−2 | 3.7×10−4 | ||

| DHMP | kcat (s−1) | 0.01±0.001 | (6.5±0.2)×10−6 | n.d. | (5.1±0.1)×10−6 | (5.7±0.9)×10−6 |

| Km (μM) | 5.5±0.2 | 4.0±0.6 | n.d. | 9.5±0.7 | n.d. | |

| kcat/Km (s−1M−1) | 1.8 | 1.6×10−3 | (8.0±0.08)×10−2 | 5.4×10−4 | ||

n.d.: not determined.

Table 5.

Steady State Kinetic Constants of EcDHNA and Site-Directed Mutants

| EcDHNA | EcE21A | EcE73A | EcK98A | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHNP | kcat (s−1) | 0.082±0.001 | (6.5±0.3)×10−5 | (7.3±0.6)×10−3 | (4.3±0.03)×10−6 |

| Km (μM) | 7.4± 0.3 | 1.6± 0.3 | 9700±1000 | 2.4±0.1 | |

| kcat/Km (s−1M−1) | 11 | 4.2×10−2 | 7.6×10−4 | 1.8×10−3 | |

| DHMP | kcat (s−1) | 0.089±0.004 | (2.3±0.2)×10−5 | (6.0±1)×10−3 | (5.3±0.05)×10−6 |

| Km (μM) | 8.0±0.6 | 0.76±0.2 | 9800±3000 | 2.9±0.2 | |

| kcat/Km (s−1μM−1) | 11 | 3.1×10−2 | 6.1×10−4 | 1.8×10−3 | |

DISCUSSION

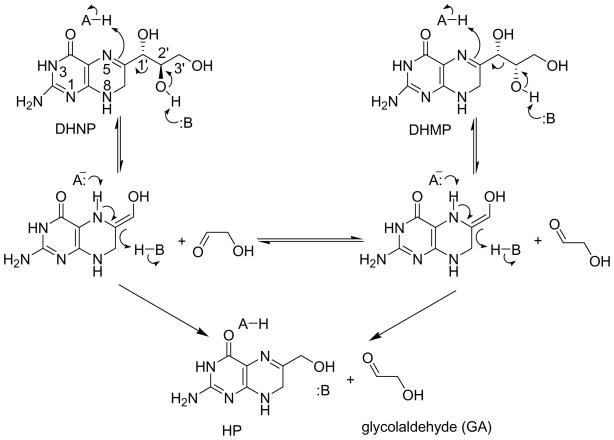

Figure 6 illustrates the proposed chemical mechanism for the DHNA-catalyzed reaction (6, 9, 10). The epimerization reaction is proposed to occur via the intermediate for the retroaldol reaction. However, little is known about how DHNA catalyzes the reaction.

Figure 6.

The proposed catalytic mechanism for the DHNA-catalyzed reactions.

Of the published crystal structures DHNAs (5, 10–12), the most informative structures are the binary HP complexes of SaDHNA and Mycobacterium tuberculosis DHNA, which reveal the atomic interactions between the pterin moiety of the substrate and the enzymes. Four conserved residues and an important water molecule are found at the active site, as illustrated in Figure 1B for SaDHNA. The structure of SaDHNA in complex with the substrate analogue NP (5) should provide the structural information about the interaction between the trihydroxypropyl moiety and the enzyme. Unfortunately, the occupancy value is 0 with an R factor of 100 for all trihydroxypropyl atoms of the bound NP, suggesting that the trihydroxypropyl moiety of NP was not seen in the crystal and no structural information about the interaction between the trihydroxypropyl moiety and the enzyme can be deduced from the crystal structure.

The interactions between pterin and DHNA are reminiscent of those of dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) with dihydrofolate, which also contains a pterin moiety. The common features include two hydrogen bonds between a carboxylate group of a glutamate or aspartate and the 2-NH2 and 3-NH groups of the pterin and a hydrogen bond between a water molecule and N5 of the pterin. Replacement of D27 of E. coli DHFR, a residue corresponding to E74 of SaDHNA and E73 of EcDHNA, with asparagine or serine causes a significant decrease in kcat and a significant increase in Km or Kd, suggesting that the aspartate is important for both substrate binding and catalysis (17). On the other hand, replacement of D26 of Lactobacillus casei DHFR, which corresponds to D27 of E. coli DHFR, with asparagine causes a <10-fold decrease in kcat and essentially no change in Km or Kd, suggesting that the carboxyl group is not important for substrate binding but may play a minor role in catalysis (18). For DHNA, the biochemical properties of SaE74A and EcE73A indicate that the conserved glutamate is very important for substrate binding and its role in catalysis is a minor one if any. It contributes to the binding of the pterin compounds by 3–5 kcal/mol on the basis of the binding data of the two mutants.

The hallmark of the DHNA-catalyzed reaction is general acid and base catalysis (Figure 6). The formation of the intermediate of the retroaldol reaction requires the protonation of N5 and the deprotonation of 2′-OH of DHNP. The formation of HP requires the deprotonation of 5-NH and the protonation of the enol group of the reaction intermediate. The epimerization reaction is essentially the reversal of the chemical step for the formation of the reaction intermediate following the flip of GA. We have recently shown that the conserved active site tyrosine residue, corresponding to Y54 in SaDHNA and Y53 in EcDHNA, plays an important role in the protonation of the enol group of the reaction intermediate to form HP (13). Replacement of either Y54 of SaDHNA or Y53 of EcDHNA causes a dramatic decrease in the rate for the formation of HP but no significant change in the rate for the formation of the reaction intermediate. Either mutation converts the aldolase to an oxygenase. The water molecule that is hydrogen bonded to N5 of HP in the crystal structures (10, 11) is most likely the general acid for the protonation of N5 of DHNP and its conjugated base for the deprotonation of 5-NH of the reaction intermediate, because no amino acid residue is in a position to play such a role according to the crystal structures. There are several candidate residues that may act as a general base for the deprotonation of 2′-OH of DHNP according to the crystal structures, including E22, Y54, and K100 (SaDHNA numbering). Y54 can be excluded on the basis of our previous site-directed mutagenesis of the conserved tyrosine residue (13). The present site-directed mutagenesis study suggests that both E22 and K100 are important for catalysis, with K100 contributing a bit more to the transition state stabilization. The larger contribution by K100 is probably due to its hydrogen bond with the water molecule that serves as a general acid in the first chemical step of the enzymatic reaction. However, from the chemical perspective, K100 is much more likely to serve as a general base for the deprotonation of 2′-OH of DHNP. The optimal pH for the DHNA-catalyzed reaction is 9.6 (6, 19). In the crystal structure of the product complex of SaDHNA, K100 is hydrogen bonded to the carboxyl group of E22, the hydroxyl group of Y54, and the water molecule that serves as a general acid. It probably has a normal pKa of ~10, which matches closely with the optimal pH of the enzymatic reaction. On the other hand, the carboxyl group of E22 is hydrogen bonded to the hydroxyl of HP, the main-chain NH of L19, and the side-chain amide of Q27. The pKa of E22 is unlikely to be higher than 4.5, the pKa of model peptides, which is too far away from the optimal pH of the enzymatic reaction. Another possibility is that the protonated amino group of K100 serves a general acid and donates its proton via the water molecule to N5 of DHNP and the carboxyl group of E22 serves as a general base to deprotonate 2′-OH of DHNP. The pH profiles of the wild-type and mutant enzymes may help to resolve this issue. Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain the pH profiles for the mutants because of their low activities.

While E74 of SaDHNA and the corresponding residue E73 in EcDHNA play a common role in the enzymatic reaction, namely in the binding of the substrate, the roles of E22 and K100 of SaDHNA are slightly different from those corresponding residues E21 and K98 in EcDHNA. Both E22 and K100 of SaDHNA are involved in catalysis but neither contributes to the binding of the substrate. On the other hand, in addition to their roles in catalysis, both E21 and K98 are also involved in the binding of the substrate. The different biochemical properties between SaDHNA and EcDHNA revealed by the previous study of the wild-type enzymes and this site-directed mutagenesis study suggest that it is possible to develop specific inhibitors for these two enzymes.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mr. Joseph Leykam for expert assistance in the HPLC analysis.

ABREVIATIONS

- DHMP

7,8-dihydro-L-monapterin

- DHNA

dihydroneopterin aldolase

- DHNP

7,8-dihydro-D-neopterin

- EcDHNA

E. coli dihydroneopterin aldolase

- EcE21A

EcDHNA with E21 replaced with alanine

- EcE73A

EcDHNA with E73 replaced with alanine

- EcK98A

EcDHNA with K98 replaced with alanine

- HP

6-hydroxymethyl-7,8-dihydropterin

- HPO

6-hydroxymethyl-7,8-dihydropterin

- MP

L-monapterin

- NP

D-neopterin

- SaDHNA

S. aureus dihydroneopterin aldolase

- SaE22A

SaDHNA with E22 replaced with alanine

- SaE74A

SaDHNA with E74 replaced with alanine

- SaK100A

SaDHNA with K100 replaced with alanine

- SaK100Q

SaDHNA with K100 replaced with glutamine

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by NIH grant GM51901 (H.Y.).

References

- 1.Walsh C. Where will new antibiotics come from? Nature Rev Microbiol. 2003;1:65–70. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bermingham A, Derrick JP. The folic acid biosynthesis pathway in bacteria: Evaluation of potential for antibacterial drug discovery. Bioessays. 2002;24:637–648. doi: 10.1002/bies.10114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kompis IM, Islam K, Then RL. DNA and RNA synthesis: Antifolates. Chem Rev. 2005;105:593–620. doi: 10.1021/cr0301144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blakley RL, Benkovic SJ. Folates and pterins. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanders WJ, Nienaber VL, Lerner CG, McCall JO, Merrick SM, Swanson SJ, Harlan JE, Stoll VS, Stamper GF, Betz SF, Condroski KR, Meadows RP, Severin JM, Walter KA, Magdalinos P, Jakob CG, Wagner R, Beutel BA. Discovery of potent inhibitors of dihydroneopterin aldolase using crystalead high-throughput X-ray crystallographic screening and structure-directed lead optimization. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1709–1718. doi: 10.1021/jm030497y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathis JB, Brown GM. The biosynthesis of folic acid XI. Purification and properties of dihydroneopterin aldolase. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:3015–3025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horecker BL, Tsolas O, Lai C-Y. Aldolases. In: Boyer PD, editor. The enzymes. Academic Press; San Diego: 1975. pp. 213–258. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen KN. Reactions of enzyme-derived enamines. In: Sinnott M, editor. Comprehensive biological catalysis. Academic Press; San Diego: 1998. pp. 135–172. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauβmann C, Rohdich F, Schmidt E, Bacher A, Richter F. Biosynthesis of pteridines in Escherichia coli - structural and mechanistic similarity of dihydroneopterin-triphosphate epimerase and dihydroneopterin aldolase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17418–17424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hennig M, D’Arcy A, Hampele IC, Page MGP, Oefner C, Dale GE. Crystal structure and reaction mechanism of 7,8-dihydroneopterin aldolase from Staphylococcus aureus. Nature Struct Biol. 1998;5:357–362. doi: 10.1038/nsb0598-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goulding CW, Apostol MI, Sawaya MR, Phillips M, Parseghian A, Eisenberg D. Regulation by oligomerization in a mycobacterial folate biosynthetic enzyme. J Mol Biol. 2005;349:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer S, Schott AK, Illarionova V, Bacher A, Huber R, Fischer M. Biosynthesis of tetrahydrofolate in plants: Crystal structure of 7,8-dihydroneopterin aldolase from Arabidopsis thaliana reveals a novel adolase class. J Mol Biol. 2004;339:967–979. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Scherperel G, Roberts KD, Jones AD, Reid GE, Yan H. A point mutation converts dihydroneopterin aldolase to a cofactor-independent oxygenase. J Am Chem Soc. 2006:128. doi: 10.1021/ja063455i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Gong Y, Shi G, Blaszczyk J, Ji X, Yan H. Chemical transformation is not rate-limiting in the reaction catalyzed by Escherichia coli 6-hydroxymethyl-7,8-dihydropterin pyrophosphokinase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:8777–8783. doi: 10.1021/bi025968h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi G, Gong Y, Savchenko A, Zeikus JG, Xiao B, Ji X, Yan H. Dissecting the nucleotide binding properties of Escherichia coli 6-hydroxymethyl-7,8-dihydropterin pyrophosphokinase with fluorescent 3′ (2)′-o-anthraniloyladenosine 5′-triphosphate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1478:289–299. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulz AR. Enzyme kinetics: From disease to multi-enzyme systems. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howell EE, Villafranca JE, Warren MS, Oatley SJ, Kraut J. Functional role of aspartic acid-27 in dihydrofolate-reductase revealed by mutagenesis. Science. 1986;231:1123–1128. doi: 10.1126/science.3511529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birdsall B, Casarotto MG, Cheung HTA, Basran J, Roberts GCK, Feeney J. The influence of aspartate 26 on the tautomeric forms of folate bound to lactobacillus casei dihydrofolate reductase. FEBS Lett. 1997;402:157–161. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01519-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathis JB, Brown GM. Dihydroneopterin aldolase from Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1980;66:556–560. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(80)66506-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraulis PJ. Molscript: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bacon DJ, Anderson WF. A fast algorithm for rendering space-filling molecule pictures. J Mol Graphics. 1988;6:219–220. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merritt EA, Bacon DJ. Raster3d: Photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:505–524. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]