Abstract

In this study, the configuration and hydrogen-bonding network of side-chain amides in a 35 kDa protein are determined via measuring differential and across-hydrogen-bond H/D isotope effects by the IS-TROSY technique, which leads to a reliable recognition and correction of erroneous rotamers frequently found in protein structures. First, the differential two-bond isotope effects on carbonyl 13C′ shifts, defined as Δ2Δ13C′ (ND) = 2Δ13C′ (NDE) − 2Δ13C′ (NDZ), provide a reliable means for the configuration assignment for side-chain amides, as environmental effects (hydrogen bonds and charges etc.) are greatly attenuated over the two bonds separating the carbon and hydrogen atoms and the isotope effects fall into a narrow range of positive values. Second and more importantly, the significant variations in the differential one-bond isotope effects on 15N chemical shifts, defined as Δ1Δ15N(D) = 1Δ15N(DE) − 1Δ15N(DZ), can be correlated with hydrogen-bonding interactions, particularly those involving charged acceptors. The differential one-bond isotope effects are additive with major contributions from intrinsic differential conjugative interactions between the E and Z configurations, H-bonding interactions, and charge effects. Furthermore, the pattern of across-H-bond H/D isotope effects can be mapped onto more complicated hydrogen-bonding networks involving bifurcated hydrogen-bonds. Third, the correlations between Δ1Δ15N(D) and hydrogen-bonding interactions afford an effective means for the correction of erroneous rotamer assignments of side-chain amides. The rotamer correction via differential isotope effects is not only robust but simple and can be applied to large proteins.

Keywords: Configuration determination, hydrogen bonding, isotope effects, NMR spectroscopy, protein side-chain amide, rotamer assignment

Introduction

The carboxamide moieties of asparagine (Asn) and glutamine (Gln) residues in proteins may serve as hydrogen-bond (H-bond) donors, acceptors, or both and are frequently involved in H-bond networks. Consequently, Asn and Gln residues are often found in the active centers of enzymes and critical elements of other proteins and play important roles in molecular recognition, catalysis, structure and stability.[1]

Despite their chemical and biological importance, H-bonds are least well defined in protein structures, which are mainly determined by X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy. In general, X-ray cannot “see” hydrogen atoms in most protein crystals and the positions of hydrogen atoms are consequently not defined. On the other hand, NMR structure calculations rely on mostly the distances between hydrogen atoms and the positions of the heavy atoms involved in hydrogen bonds are defined by standard covalent geometry information. In the case of side-chain carboxamides, the identities of the nitrogen and oxygen atoms are also hard to be recognized by X-ray crystallography, because the nitrogen and oxygen atoms within a carboxamide group are related by a two-fold symmetrical axis and their electron density maps are very similar. Consequently, erroneous rotamer assignments of side-chain amides are frequently found in protein crystal structures. It has been estimated[2] that ~ 20% of side-chain amide rotamers are incorrect in protein crystal structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB).[3] A similar error rate in solution NMR structures of proteins has also been estimated.[4]

One of the most important advances in NMR spectroscopy in the last decade was the direct detection of H-bonds through trans-hydrogen-bond scalar couplings. Trans-hydrogen-bond scalar couplings are generally small and thus cannot be measured for large proteins. Unlike the electron-mediating scalar couplings, isotope effects are intrinsically vibrational phenomena. However, since isotope effects can be transmitted through covalent bonds as well as H-bonds, potentially they can be used as an alternative means for the direct detection of H-bonds.

The usefulness of isotope effects in NMR analysis of compounds, small proteins and nucleic acids has been widely reported in literatures.[5–6] Several lines of evidence have shown a clear correlation between primary deuterium (D) isotope effects and the strength of H-bonds.[7–8] Since the NMR direct observation of deuterium is limited by experimental conditions, broad linewidth and low sensitivity, current studies have been focused on secondary H/D isotope effects. With the advent of triple-resonance NMR techniques and the availability of isotope-enriched materials, extensive and in-depth studies on deuterium isotope effects on the chemical shifts of proteins and nucleic acids have become possible. For instance, the 2D HA(CA)CO experiment has been used for measuring 2Δ13C′ (ND) in the study of the equilibrium protium/deuterium fractionation of backbone amides in human ubiquitin;[9] 3Δ13Cα(ND) and 2Δ13Cα(ND) isotope effects have been measured with 3D HCA(CO)N and 3D HCAN experiments, respectively, for the correlation of 13Cα chemical shifts with the backbone conformation;[10] backbone 2Δ13C′ (ND), 3Δ13Cα(ND) and 3Δ13Cβ(ND) isotope effects have also been measured with new editing and filtering techniques.[11–12] However, because isotope effects on chemical shifts are generally small, most of their biological applications to date have been limited to small proteins and nucleic acids. Deuterium isotope effects on protein side-chain amides have hardly been studied, because side-chain amide resonances are normally invisible in standard TROSY-based NMR experiments, which are required for large proteins. Recently, we have demonstrated that the TROSY methodology can be adapted for the detection of the NMR signals of side-chain amides with a significantly enhanced sensitivity, particularly for large proteins, through the combined use of 50%H2O/50%D2O mixture solvent and deuterium decoupling.[13–14] The new TROSY technique, dubbed isotopomer-selective (IS)-TROSY, exclusively detects semideuterated isotopomers of carboxamide groups of Asn/Gln residues in large proteins with high sensitivities just as the detection of backbone amides with standard TROSY experiments.

The two primary amide protons within a side-chain carboxamide group usually show different chemical shifts, due to the slow inter-converting rate stemmed from the partial double-bond character of the C′–Nδ/ε (Asn/Gln) amide bonds. One of the geminal amide protons is in the trans (E) configuration with respect to the carboxamide oxygen and normally has a downfield (high frequency) chemical shift; the other, in the cis (Z) configuration, shows an upfield chemical shift. However, the order of their chemical shifts could be reversed, due to aromatic ring current effects and/or strong H-bonding interactions. Therefore, the stereospecific resonance assignment of side-chain amide protons is prerequisite for further NMR studies of side-chain amides in proteins.

We report here the differential secondary H/D isotope effects on the side-chain amides of yeast cytosine deaminase (yCD), a 35 kDa homodimeric protein, measured by the IS-TROSY-based technique. We show that the measurement of differential isotope effects is an effective means for the assignment of configurations, identification of hydrogen bonds, and correction of erroneous rotamers of side-chain amides.

Results and discussion

Differential one-bond H/D isotope effects on side-chain carboxamide 15N chemical shift

Although the understanding of isotope effects on NMR chemical shifts is incomplete, from accumulated experimental observations over decades, it is generally accepted that the magnitude of the isotope effects depends not only on the ratio of isotope masses but also on the chemical shift range of the nucleus.[5,15] The larger the chemical shift range of the nucleus, the larger are the isotope effects. For instance, the size of one-bond deuterium isotope effects on the chemical shift of amide 15N, defined as 1Δ15N(D) = δ15N{H} − δ15N{D}, is up to ~ 700 ppb in proteins, because amide 15N chemical shifts are well dispersed. In protein backbones, variations in 1Δ15N(D) depend primarily on the difference in hydrogen bonding interactions[9] and electric field effects from charges in the vicinity of amide protons.[16–18] The effects of conformation are relatively small, because the amide proton is typically in the trans configuration with respect to the carbonyl oxygen of the preceding residue.

For side-chain carboxamides of Asn and Gln residues, the two geminal protons have different configurations. The N–HE bond is trans to the C=O bond and has a stretching frequency higher than that of the N–HZ bond which is cis to the C=O bond. One of the important properties of amides is their tendency to involve the nitrogen lone pair in the carbonyl π system, resulting in the partial double-bond character, i.e. both the C′–N and C′–O bonds have a bond order of 1.5, which makes the amide group planar and rigid. Consequently, the two geminal N–HE and N–HZ bonds have different orientations with respect to the adjacent π orbitals, which is somewhat reminiscent of the much less restricted orientations of the two geminal C–Hα bonds in a glycine residue.[19] As a result of different (hyper)conjugations, the N–HE bond length is likely 1–2% shorter than that of the N–HZ bond as determined by neutron diffraction,[20–21] although the difference was not detected by solid state NMR measurements.[22] The configuration-dependent changes in the vibrational manifold lead to differential isotope effects, and it follows that 1Δ15N(DE) is intrinsically larger than 1Δ15N(DZ). In other words, the difference in the secondary isotope effects or the differential one-bond isotope effects, Δ1Δ15N(D) = 1Δ15N(DE) − 1Δ15N(DZ), is normally positive.

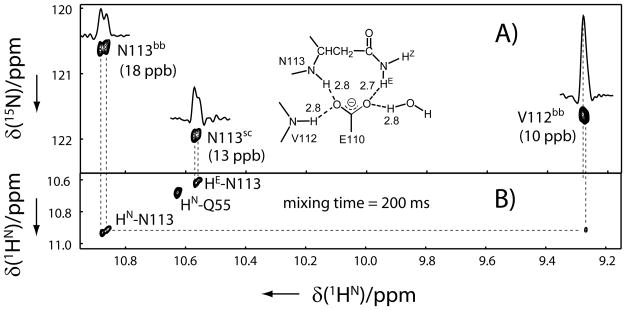

The measurement of one-bond H/D isotope effects, 1Δ15N(DE/Z), is straightforward for small proteins, as illustrated in the top panel of Figure 1. In a standard 15N–1H HSQC spectrum recorded for a small protein in the H2O/D2O mixture solvent, normally four resonances (dashed circles) for each side-chain amide can be observed, one pair from the fully protonated isotopomer (large dashed circles) at the downfield in the 15N dimension and the other from the two semideuterated isotopomers (small dashed circles) at upfield. The neat differential H/D isotope effects on one-bond 15N chemical shifts,Δ1Δ15N(D), can in principle be measured from the 15N chemical shift difference between the two semideuterated peaks (the two smaller dashed circles), if there is no signal overlap and sensitivity is high enough. For large proteins, however, the direct measurement of 1Δ15N(D) is often impossible, because resonances of 15NH2 isotopomers are weak, due to the strong dipole–dipole interaction between the geminal protons, especially in the presence of H-bonds,[13–14] and the chance of signal overlap is high. In the 2D 15N–1H IS-TROSY spectrum, however, the two protonated resonances are filtered out[23] and thus the spectrum is simplified. More importantly, the experiment exclusively detects the so called TROSY peak with a high sensitivity, which is the lower right component of each quartet (the TROSY component is represented as a small filled circle and the three non-TROSY components are as open circles).[13–14] Figure 1A is a region of the 2D 15N–1H IS-TROSY spectrum of yCD. The resonance of the 15N–HE{DZ} isotopomer has the 15N chemical shift modified by the 1Δ15N(DZ) isotope effect from the Z position and that of the 15N–HZ{DE} isotopomer by 1Δ15N(DE) from the E position. The measured differential one-bond isotope effects,Δ1Δ15N(D) = 1Δ15N(DE) − 1Δ15N(DZ), are summarized in Table 1. Duplicated experiments indicate that the differential isotope effects could be measured with a high accuracy (the standard error is less than 5 ppb). These differential isotope effects can be accurately measured even when the linewidth is larger than the chemical shift difference in the 15N dimension, because the corresponding proton resonances are well separated, which is similar to the accurate measurement of small J-couplings in E.COSY type of spectra.[24] The adoption of the TROSY technique and deuteration actually makes the linewidth very narrow even for large proteins.

Figure 1.

Regions of A) 2D 15N–1H IS-TROSY and B) 2D IS-TROSY-H(N)CO spectra of yCD showing Asn/Gln side-chain amide resonance correlations. On top of A) is a schematic diagram that illustrates how the differential H/D isotope effects on one-bond 15N chemical shifts, Δ1Δ15N(D) = 1Δ15N(DE) − 1Δ15N(DZ), are measured in the 2D 15N–1H IS-TROSY spectrum. Both spectra A) and B) were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE 900 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a TCI cryoprobe at 25 °C with a u-2H/13C/15N labeled protein sample in the 50% H2O/50% D2O solvent. The differential H/D isotope effects on one-bond 15N chemical shifts, Δ1Δ15N(D) = 1Δ15N(DE) − 1Δ15N(DZ) (modified by scalar couplings), and on two-bond 13C′ chemical shifts, Δ2Δ13C′ (ND) = 2Δ13C′ (NDE) − 2Δ13C′ (NDZ), where E stands for the trans and Z the cis side-chain amide hydrogen atoms, can be accurately measured from the chemical shift difference in the indirect dimension for the same carboxyamide moiety. Paired side-chain NH{D} resonances of each Asn/Gln residue is linked by two dash lines across the center of each resonance, and the chemical shift difference is indicated with paired arrows. Stereospecific distinction between the E and Z protons can be achieved based on the difference in isotope effects (refer to the text for details). Spectrum of A) was recorded with 8 scans and a 2 s delay time, t1max(15N) = 93 ms and t2max(1HN) = 285 ms, resulting in the experimental time of 2.4 h and spectrum of B) with 64 scans and a 1.8 s delay time, t1max(13C) = 110 ms and t2max(1HN) = 285 ms, resulting in the experimental time of 29.8 h Before Fourier transformation, the raw data were zero filled resulting in a 0.5 Hz digital resolution in the indirect dimension for spectrum A) and 1.0 Hz for B).

Table 1.

Differential secondary protium/deuterium isotope effects and corresponding H-bond patterns of side-chain carboxamides in yCD.

| Residues | Δ1Δ15N(D)[a] (ppb) | Δ2Δ13C′ (ND)[b] (ppb) | H-bonds patterns[c] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gln12 | 109 | 37 | N–HE···Oδ1 of Asp16 (2.88/3.11 Å; 135/164°)[d] |

| Asn39 | 65 | 36 | C=Oδ1···H–Nbb of Lys41 (2.75/3.03 Å; 122/157°) C=Oδ1···H–Nbb of Asp42 (2.87/4.24 Å; 146/140°) |

| Asn40 | 103 | 41 | N–HE···Oδ1 of Asp81 (2.86/2.89 Å; 171/168°) N–HZ···O=Cbb of Thr82 (3.22/3.28 Å; 137/132°) C=Oδ1···Hγ1–Oγ1 of Thr83 (2.68/2.74 Å; 166/141°) |

| Asn51 | −18/−4 | 57/23 | N–HE···O2 of IPy (2.90/2.92 Å; 171/169°) N–HZ···Oδ1 of Asp155 (2.90/2.92 Å; 162/162°) C=Oδ1···H–Nbb of Arg53 (2.84/2.88 Å; 158/156°) |

| Gln55 | 128/41 | 57/17 | N–HE···Oε2 of Glu28 (2.87/2.87 Å; 156/157°) C=Oε1···H–Nbb of Gln55 (2.69/2.77 Å; 144/143°) |

| Asn70 | 84 | 37 | N–HE···O=Cbb of Arg48 (2.77/2.83 Å; 172/176°) |

| Asn111 | 125 | 40 | N–HE···Oε2 of Glu119 (2.90/2.94 Å; 162/161°) |

| Asn113 | 231/260 | 39/24 | N–HE···Oε1 of Glu110 (2.57/2.62 Å; 158/166°)[d] N–HZ···O=Cbb of Lys138 (3.09/3.14 Å; 154/146°)[d] |

| Gln123 | 53 | 35 | N–HE···O=Cbb of Glu119 (2.94/3.64 Å; 146/129°) |

| Gln143 | 64 | 33 | N–HE···Oη of Tyr126 (3.02/3.06 Å; 130/120°)[d] |

| Gln150 | 54 | 37 | no H-bond |

Δ1Δ15N(D) = 1Δ15N(DE) − 1Δ15N(DZ), difference in one-bond H/D isotope effects on carboxyamide 15N chemical shifts, where E stands for the trans position and Z cis position of side-chain amide protons with respect to the carboxyamide oxygen. The values were measured directly from the 2D 15N–1H IS-TROSY spectrum without correction for differential 1JNH(E/Z) scalar coupling constants. The bold numbers include the contributions from across-H-bond isotope effects. The standard error in repeated measurements is less than 5 ppb and RMSD to the mean is about 2 ppb.

Δ2Δ13C′ (ND) = 2Δ13C′ (NDE) − 2Δ13C′ (NDZ), difference in two-bond H/D isotope effects on carboxyamide 13C′ chemical shifts, where E stands for the trans position and Z cis position of side-chain amide protons with respect to the carboxyamide oxygen. The magnitudes result from modifications of across-H-bond isotope effects are in bold. The standard error in repeated measurements is less than 5 ppb and RMSD to the mean is about 2 ppb.

H-bonds A–H···B involving the carboxyamide group of individual Asn/Gln residues in yCD derived from the 1.14 Å-resolution crystal structure (PDB accession code: 1P6O) with A designating the hydrogen donor and B the acceptor, followed by distances (in the unit of Å) between heavy atoms A and B in two subunits with the corresponding H-bond angles in degrees. The superscript bb stands for protein backbone.

H-bonds are formed only if positions of the nitrogen and oxygen atoms of the carboxyamide moiety are swapped in the crystal structure.

As expected, most (ten out of eleven) of the Δ1Δ15N(D) values for yCD are positive, characteristic of configurational effects, but their magnitudes vary significantly and one (Asn51) of them is even negative. The large variations in Δ1Δ15N(D) indicate that the magnitude of 1Δ15N(D) is sensitive to the H-bonding interactions involved and charges in the vicinity of the amide proton, which will be discussed in a later section.

It is noteworthy that the apparent magnitude of Δ1Δ15N(D), as measured directly from the 15N–1H IS-TROSY spectrum, is not a neat differential isotope effect. Rather, it is modified by the difference between the 1JNH(E/Z) coupling constants for the E and Z amide protons in semideuterated isotopomers, as the chemical shift of the TROSY resonance is away from the corresponding HSQC resonance by half of the one-bond scalar coupling constant in both 1H and 15N dimensions (see the top panel of Figure 1). These one-bond scalar couplings can be accurately measured by 15N-coupled 15N–1H HSQC experiments (see Supporting Information) with the yCD NMR sample in 75% H2O/25% D2O. The result shows that for all but Asn51 side-chain amides, 1JNHE{DZ} of 15NHE{DZ} is 1–4 ppb larger than 1JNHZ{DE} of 15NHZ{DE} in the 1H dimension at the 900 MHz field, which is commensurate with 10–40 ppb in the 15N dimension. Repeated measurements essentially give the same result. Since the magnitude of 1JNHE{DZ} for 1HE is generally 1–4 Hz larger than that of 1JNHZ{DE} for 1HZ, the differential Δ1Δ15N(D) isotope effects are apparently “enhanced” by (|1JNHE{DZ}| − |1JNHZ{DE}|)/2, i.e. 0.5–2.0 Hz (5–20 ppb at the 15N frequency of 90 MHz). Asn51 is the sole exception and its 1JNHE{DZ} is slightly smaller (2 ppb) than 1JNHZ{DE}, likely due to the very strong H-bonding and charge effect through its Z proton. Because the differences of paired one-bond scalar coupling constants are quite uniform and relatively small at ultrahigh magnetic fields as measured with yCD, variations in apparent Δ1Δ15N(D) from IS-TROSY in essence manifest the same changes in neat differential isotope effects caused by configuration, H-bonding, charge effects, etc. For the sake of simplicity, we will not further discuss the enhancement of the differential isotope effects by the small difference in the scalar coupling constants.

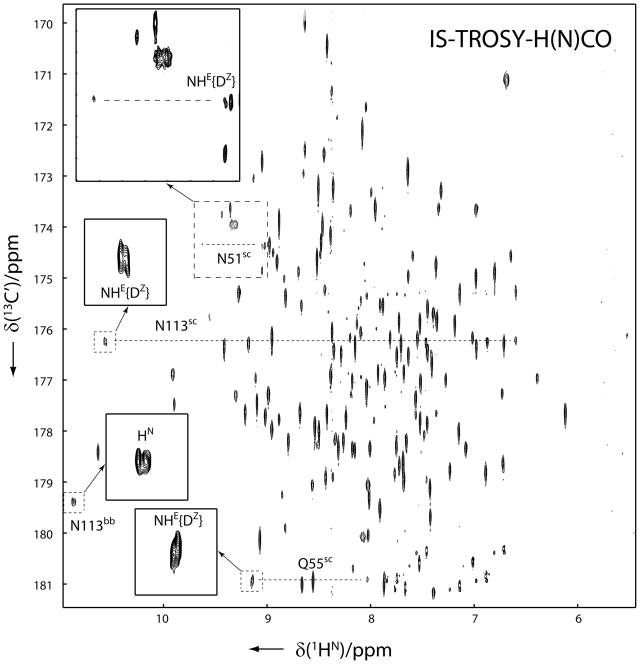

Differential two-bond H/D isotope effect on side-chain carboxamide 13C′ chemical shift

It has long been documented that the magnitude of isotope effects decreases rapidly with increasing number of bonds that separate the observed nucleus and the isotope-substituted position.[15] In protein backbones, however, the amide H/D isotope effects on two-bond 13C′ chemical shifts, 2Δ13C′ (ND), are surprisingly large, ranging from 100 to 200 ppb.[11–12] In contrast, the two-bond isotope effects on 13Cα, 2Δ13Cα(ND), are generally less than 100 ppb but sensitive to the backbone conformation.[10] Traditionally, the large backbone 2Δ13C′ (ND) isotope effects are used for resonance assignments of peptides[25–26] and small proteins.[27–28] These two-bond isotope effects are also considered to be correlated with intra-residual H-bonds in antiparallel β-sheets, as demonstrated in the small protein BPTI,[29] although the reported magnitude falls into a rather narrow range, 60–90 ppb, in this case. The backbone amide proton of a residue is in the trans configuration with respect to the carbonyl oxygen of the preceding residue, which is characterized by the positive two-bond scalar coupling constant, 2JHC′, between the amide proton and carbonyl carbon. Similarly, one of geminal protons in a side-chain carboxamide is in the trans configuration and shows a positive 2JHC′ coupling constant as in the backbone, but the other is in the cis configuration and is characterized by a negative 2JHC′ coupling constant.[30] This feature has been used for the stereospecific resonance assignment of side-chain amide protons in small proteins[31] and larger ones as well.[13] In side-chain carboxamide moieties of Asn/Gln residues, for the same reason of differential conjugative interactions and thus stretching frequencies, the magnitude of 2Δ13C′ (NDE) from the E position is larger than 2Δ13C′ (NDZ) from the Z position. As a result, the differential two-bond isotope effects,Δ2Δ13C′ (ND) = 2Δ13C′ (NDE) − 2Δ13C′ (NDZ), are expected to be positive too. The magnitude of Δ2Δ13C′ (ND) can be readily measured from the 2D IS-TROSY-H(N)CO spectrum (Figure 1B).[13] It is worthwhile to note that, unlike Δ1Δ15N(D), the magnitude of Δ2Δ13C′ (ND), as measured from the 2D IS-TROSY-H(N)CO spectrum, represents neat differential isotope effects with no contribution from scalar couplings. TheΔ2Δ13C′ (ND) values of 11 Asn/Gln residues in yCD are indeed all positive (Table 1), in spite of the diversity in H-bonding interactions and charge effects among individual side-chain amides. The influences of H-bonding and/or charges appear to be largely attenuated over two bonds. Those side-chain amides with one of their geminal protons involved in H-bonding with a negatively charged group, such as the carboxylate of an Asp/Glu residue, have slightly larger isotope effects, but the magnitudes of these two-bond differential isotope effects all fall into a narrow range of 33–57 ppb. The result indicates that Δ2Δ13C′ (ND) can be used for the configuration assignment of side-chain amides.

Across-hydrogen-bond H/D isotope effects

In a very recent publication, we reported the first detection of bifurcated hydrogen bonds by NMR via trans-H-bond H/D isotope effects.[32] Specifically, in the 50% H2O/50% D2O mixture solvent, the resonances of side-chain 15N–1HE{DZ} of Asn51, backbone amide of Asn113, and side-chain 15N–1HE{DZ} of Asn113 show doublets in the 1H dimension, which are caused by H/D isotope effects from the backbone amide protons of Gly63, Val112, and a bound water molecule, respectively, across H···O···H type of bifurcated H-bonds.[32] Unexpectedly, the backbone amide resonance of either Gly63 or Val112 appears as a singlet, indicating that the observed across-H-bond isotope effects are asymmetrical. As such, the 2D 15N–1H IS-TROSY spectrum per se does not seem to identify both residues involved in the bifurcated H-bonds. However, the two amide protons that are linked to each other in the H···O···H bifurcated H-bonding network are close enough in space (< 4 Å) so that their correlation can be exclusively established in the NOESY spectrum under the highly deuterated background in concert with the information from trans-H-bond isotope effects. Figure 2 shows a region of the 2D 1H–1H projection of the 3D [15N–1H]-IS-TROSY-dispersed-NOESY spectrum of yCD together with the corresponding 2D 15N–1H IS-TROSY spectrum. The weaker component (upfield) of the backbone amide resonance of Asn113 shows a cross peak with the backbone amide proton of Val112 in the NOESY spectrum, whereas the stronger component (downfield) does not, indicating that the former is the resonance corresponding to the protonated isotopomer and the latter the deuterated isotopomer. This is consistent with the conclusion based on the spectral comparison with two yCD samples in 50% H2O/50 D2O and in 95% H2O/5% D2O, respectively.[32] Interestingly, the chemical shift for the backbone amide proton of Val112 from the NOE cross peak linking the backbone amide proton of Asn113 (Figure 2B) is not exactly the same as the corresponding resonance in the 15N–1H IS-TROSY spectrum (Figure 2A), but at about 10 ppb towards the upfield. This difference must be caused by the across-H-bond H/D isotope effects, 2hΔ1H, from the backbone amide of Asn113, i.e. the chemical shift of the Val112 resonance in the IS-TROSY spectrum corresponds approximately to the isotopomer that the backbone amide of Asn113 is deuterated since the protonated component is expected to be weaker, while the chemical shift of the Val112 cross peak in the NOESY spectrum must correspond exactly to the protonated component. In other word, combined with the IS-TROSY spectrum, the IS-TROSY-dispersed NOESY spectrum provides not only the valuable correlation information between the two amide protons that are connected through bifurcated H-bonds but also the magnitude and sign of the 2hΔ1H isotope effect even when it is smaller than the linewidth. The sign of the 2hΔ1H isotope effect for Val112 is negative, but the small 3hΔ15N isotope effect through the Val112-N-H···O···H/D-Asn113 hydrogen bonds for Val112 appears positive, although the magnitude is very small. No NOE is observed between the backbone amide proton of Gly63 and the side-chain amide protons of Asn51 within the limited measuring time, presumably because the relative population of the fully protonated or each semideuterated isotopomer of a side-chain amide is only about half of the corresponding protonated backbone amide in the mixture solvent and the spin diffusion within the nearby protonated ligand is expected to be a negative factor to the expected NOE. Nonetheless, in principle, such NOEs involving side-chain amide protons should be detectable and provide valuable correlation information in concert with trans-H-bond isotope effects for the assignment of Asn/Gln rotamers.

Figure 2.

Regions of A) the 2D 15N–1H IS-TROSY spectrum and B) the 2D projection of 3D 15N–1H IS-TROSY-dispersed NOESY spectrum of yCD with u-2H/13C/15N labeling in 50% H2O/50% D2O. The spectrum was recorded on a Bruker AVANCE 900 MHz NMR spectrometer. Experimental and data processing conditions are the same as in Figure 1. Illustrated in the inset in panel A) is suggested hydrogen-bonding network of Asn113, which is derived from the 1.14 Ǻ crystal structure of yCD (accession code: 1P6O) after flipping the side-chain oxygen and nitrogen positions.

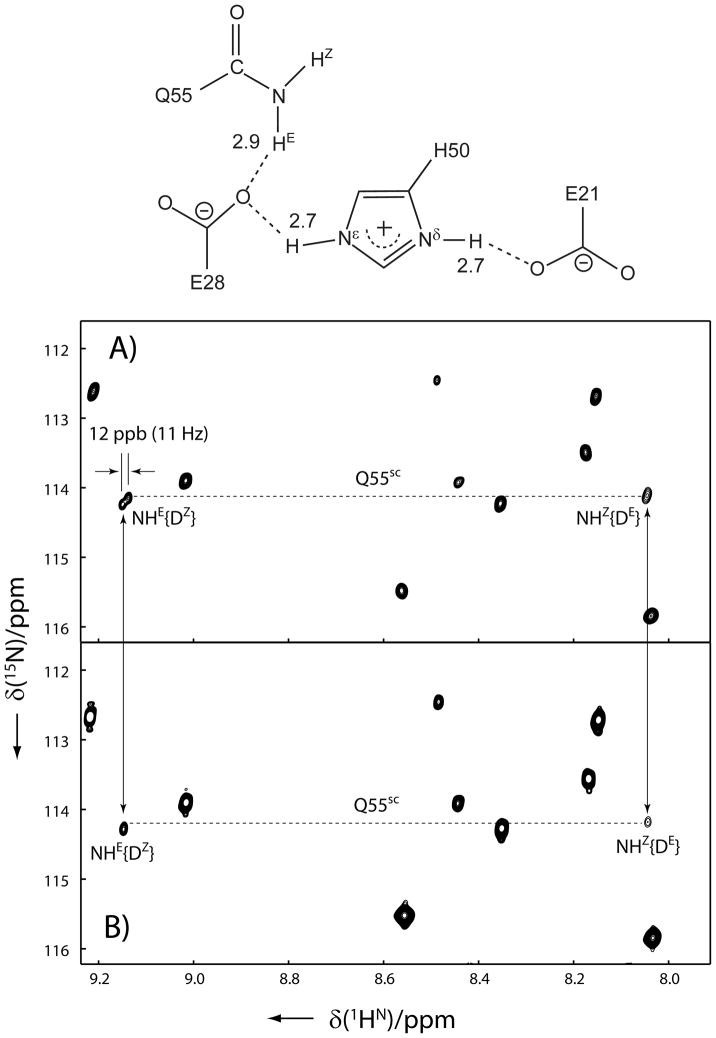

Interestingly, neither the magnitudes nor signs of the two-bond isotope effect, 2hΔ1H, and the three-bond isotope effect, 3hΔ15N, that are transmitted through 15N-H···O···H/D bifurcated H-bonds are uniform, which probably reflects the diversity in geometries and/or electronic features of the corresponding H-bonding networks. In addition, a closer inspection reveals that the 1HE resonance of Gln55 also shows doublets in both 1H and 15N dimensions of the IS-TROSY spectrum. Since it forms bifurcated H-bonds together with the Hε2 of His50 to the Oε atom of Glu28 in the crystal structure, the splittings are most likely due to trans-H-bond isotope effects with positive 12 ppb of 2hΔ1H in the 1H dimension and a small positive 3hΔ15N in the 15N dimension (see Figure 3). Furthermore, the four-bond H/D isotope effect on the side-chain carboxamide carbon, 4hΔ13C′, which is transmitted through 13C′-N-H···O···H/D bifurcated H-bonds can be observed in the 2D H(N)CO-IS-TROSY spectrum (see Figure 4). The signs of 4hΔ13C′ for all the three bifurcated H-bonds are positive. They are those between the side-chain amides of Asn51, Gln55 and Asn113 and the backbone amide of Gly63 through the carbonyl oxygen (O2) of the ligand, the side-chain Hε2 of His50 through the side-chain Oε of Glu28 and a water molecule through the side-chain Oε of Glu110, respectively. The sign of 4hΔ13C′ for the backbone amide of Asn113 due to the bifurcated H-bond of the backbone amide of Vall112 through the carboxyl oxygen of Glu110 appears positive too, although the magnitude is negligibly small (Figure 4). The modified differential isotope effects due to the trans-H-bond isotope effects are also listed in bold in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Regions of the 2D 15N–1H IS-TROSY spectra of u-2H/13C/15N labeled yCD in A) 50% H2O/50% D2O and B) 95% H2O/5% D2O. The spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE 900 MHz NMR spectrometer. Experimental and data processing conditions are the same as in Figure 1. The doublets of Gln55-NHE{HZ} resonance are caused by across H-bond H/D isotope effects mediated via the bifurcated H-bond of His50-Hε/Dε as illustrated in the top diagram.

Figure 4.

2D IS-TROSY-H(N)CO spectrum of u-2H/13C/15N labeled yCD in 50% H2O/50% D2O. The spectrum was recorded on a Bruker AVANCE 900 MHz NMR spectrometer. The doublet Asn/Gln side-chain amide cross-peaks, enclosed with dashed and enlarged with solid squares, are caused by trans-H-bond isotope effects 2hΔ1H and 4hΔ13C′. The spectrum was recorded with 128 scans and a 1.8 s delay time, t1max(13C) = 71 ms and t2max(1HN) = 285 ms, resulting in the experimental time of 41 h. Before Fourier transformation, the raw data were zero filled resulting in a 1.0 Hz digital resolution in the indirect dimension.

Correlation with H-bonding network

While the narrow range of positive differential two-bond Δ2Δ13C′ (ND) isotope effects is useful for the configuration assignment of side-chain amides, the large variations in the differential one-bondΔ1Δ15N(D) isotope effects can be correlated with H-bonds involved in the side-chain amides. Two crystal structures of yCD in complex with a transition state analogue, 1UAQ and 1P6O at the resolutions of 1.6 Å[33] and 1.14 Å[34], respectively, have been published. Since the 1P6O structure is of much higher resolution, we will mainly use this structure as the reference to illustrate the contraventions and uncertainties in the H-bonding interactions of side-chain carboxamides, as revealed by measured H/D isotope effects. In the crystal structure, side-chain amide protons of Gln12, Asn39, Asn113, Gln123, Gln143 and Gln150 are exposed to the solvent and make no or weak H-bonding interactions to potential acceptors. Except for Gln 12 and Asn 113, all these solvent exposed amides, evidenced by their sharp and poorly dispersed resonances in the 2D 15N–1H correlation spectra, render uniform magnitudes of Δ1Δ15N(D) and Δ2Δ13C′ (ND) ranging from 52–65 ppb and 33–37 ppb, respectively, which reflects the neat conjugative difference between the E and Z configurations. Surprisingly, theΔ1Δ15N(D) effects of Gln12 and Asn113 are about two times (109 ppb) and four times (231 ppb), respectively, larger than those of other residues within this group. Apparently, there must be contributions from other factors. Both theoretical calculations[35] and experimental measurements[10] with model compounds and small proteins indicate that one-bond H/D isotope effects on 15N chemical shifts, 1Δ15N(D), depend on H-bonding strengths (in terms of bond lengths and angles) and charges, which arouse electric field effects, in the vicinity of the amide proton.[16–18] It has been widely accepted that upon H-bonding, the potential of stretching vibrations becomes more asymmetrical with a lower zero-point energy for a deuterium in comparison with a protium, leading to an enlarged difference in the bond lengths between 15N–H and 15N–D and thus a larger isotope effect results.[5] Moreover, ionization could greatly affect H-bonding; a positively charged donor and/or a negatively charged acceptor will strengthen the H-bond by virtue of an increased attraction in electron densities associated with the acceptor and the donor.[7] As such, negative charges at the H/D acceptor site, such as the carboxyl oxygen atoms of an acidic residue, strengthen the H-bond through hyperconjugative interactions with the amide moiety and give rise to more significant isotope effects. Therefore, the unexpected largeΔ1Δ15N(D) values of Gln12 and Asn113 most likely result from H-bonding and charges. Indeed, if the positions of the nitrogen and oxygen atoms in the side-chain carboxamides are flipped, the 1HE of Gln12 may form a H-bond with the carboxylate group of Asp16 and the 1HE of Asn113 may form a H-bond with the carboxylate group of Glu110 (see Table 1). The H-bond involving the 1HE of Asn113 is strong, with a short bond length (~2.60 Ǻ between the heavy atoms) and a nearly ideal bond angle (≥160°). However, the H-bond involving the 1HE of Gln12 is rather weak with a longer bond length and smaller bond angle. This is also indicated by its sharp resonances and the chemical shift characteristic of a flexible side-chain amide. Therefore, the large Δ1Δ15N(D) magnitude for Gln12 is likely mainly caused by the negative charge of Asp16, which enhances the isotope effect by at least 40 ppb, and the much larger magnitude for Asn113 must be due to the combined result of the charge and a strong H-bond with Glu110. The correlations between the large Δ1Δ15N(D) magnitudes and charge and/or H-bond strength for Gln12 and Asn113 are confirmed by the observation of large Δ1Δ15N(D) magnitudes for Asn40 (103 ppb), Gln55 (128 ppb) and Asn111 (125 ppb), whose 1HE atoms form H-bonds with the negatively charged carboxyl oxygen atoms of Asp81, Glu28 and Glu119, respectively, with similar bond lengths (~2.9 Å) and angles (155–170°). Interestingly, the 1HZ (not 1HE) of Asn51 forms a H-bond with the carboxyl oxygen of Asp155 (negatively charged), which apparently overwhelms combined contributions from differential configurations and differential 1JNHE{DZ}/1JNHZ{DE} coupling constants as well as the neutral H-bond between the 1HE of Asn51 and the O2 atom of the ligand, and makes itsΔ15N(DZ) larger than Δ15N(DE), thus a slightly negative value ofΔ1Δ15N(D), because the contribution from the charged H-bond is at least two times larger in magnitude than that of the configuration effects. On the other hand, the 1HE of Asn70 forms a neutral H-bond with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Arg48 and the magnitude of its Δ1Δ15N(D) is 84 ppb, 20–30 ppb larger than those involved in no or very weak H-bonding but at least 20 ppb smaller than that involved in H-bonds with negatively charged acceptors. For the side-chain amide of Gln123, its 1HE could form a weak H-bond to the backbone carbonyl oxygen (no charge) of Glu119 with a bond length of 2.94 Ǻ in one subunit of the crystal structure but the corresponding distance is as long as 3.64 Ǻ in the other subunit, which unlikely forms any H-bond. This is supported by the unstructured character of its side-chain resonances. The 1HE of Gln143 could form a weak H-bond to the Oη of Tyr126 if the side-chain N/O positions of the former are swapped. The side-chain amide of Gln150 does not form any H-bond in the crystal structure. H-bonding contributions to Δ1Δ15N(D) through the side-chain carboxamide oxygen appear rather small. For instance, the side-chain oxygen of Asn39 forms bifurcated H-bonds to both backbone amides of Lys41 and Asp42, but itsΔ1Δ15N(D) magnitude is only 65 ppb, similar to those without or with weak H-bonding.

| (1) |

Based on the above analysis on the isotope effects as listed in Table 1, an empirical quantification emerges as described in equation (1), containing additive contributions to differential one-bond H/D isotope effects on 15N chemical shifts of side-chain amides. The first two terms are intrinsic:Δc is the contribution of configurational effects with a positive magnitude of 40–45 ppb and Δj the contribution of differential 1JNHE{DZ}/1JNHZ{DE} coupling constants normally with a positive magnitude of 5–20 ppb (at the 90 MHz field). The third term, Δh, reflects the contributions from H-bonding interactions; a weak H-bond may account for 10 ppb and a normal one for 30 ppb and the sign is positive if 1HE is involved but negative if 1HZ involved. The term Δe represents the contribution of charges that are involved in H-bonds, i.e. negatively charged Asp/Glu side-chain carboxyl oxygen atoms as hydrogen acceptors in this work. It is about 40 ppb for a weak H-bond. However, Δe may be over 140 ppb for a strong H-bond with a positive sign if 1HE is involved but negative if 1HZ involved in the H-bond. The termΔo is the H-bonding contribution through the oxygen atom of a side-chain carboxamide and is normally small, only about 10 ppb. The last term Δa is the contribution from across-H-bond isotope effects, which can vary significantly as described earlier. In brief, the magnitude of Δ1Δ15N(D) in side-chain amides is intricately governed by the differential configurations but significantly modified by H-bonding interactions, particularly those with charged H-bond acceptors such as carboxyl oxygen atoms of Asp/Glu residues. Significant deviations inΔ1Δ15N(D) from the nominal values of solvent exposed, flexible side-chain amides (50–60 ppb at the 900 MHz field) are strongly indicative of H-bonding and charges and can be directly correlated with H-bonding networks.

It is noteworthy that typically only the 1HE or 1HZ, but not both, of a side-chain amide forms a H-bond with a negatively charged acceptor, because the proximity of two negatively charged groups is energetically unfavorable. On the other hand, both the 1HE and 1HZ of a side-chain amide could form neutral H-bonds simultaneously, which may result in a small neat contribution to Δ1Δ15N(D). However, there is no such a case in yCD. Perhaps one would expect a smaller Δ1Δ15N(D) in comparison with non-H-bonded situations if only 1HZ forms a neutral H-bond. Unfortunately, there is no such an example in yCD either. This speculation must await the observation in more proteins with high-resolution structures.

Rotamer correction

As described in the Introduction section, a rather high percentage of side-chain amide rotamers is incorrectly assigned in both crystal and NMR structures of proteins. Such errors are found even in ultrahigh resolution crystal structures, e.g. the 0.85 Å-resolution crystal structure of the 122-residue acutoaemolysin.[36] Of the eleven side-chain amides of this protein, three have incorrect rotamers. Residual dipolar coupling (RDC) data have been used for the identification of erroneous side-chain amide rotamer assignments in 16 high-resolution crystal structures of hen egg-white lysozyme.[37] Of the 146 rotamers assigned based on the NMR data, 26 are inconsistent with those in the crystal structures. While RDC analysis is very powerful for the correction of side-chain amide rotamer assignment errors, acquisition of RDC data is much more complicated than the measurement of differential isotope effects. Moreover, the 1H–1H RDC data for side-chain amides are difficult to get for large proteins, because of line broadening due to strong dipole–dipole interactions, unless the IS-TROSY strategy is adopted.[21–22]

The differential secondary isotope effects of side-chain amides provide a simple means for the correction of the erroneous rotamer assignments. Based on the analysis of the differential secondary isotope effects as described above, the side-chain 1HE proton of Asn113 forms a strong H-bond with charged groups. The H-bonding of Asn113 as revealed by differential isotope effects is inconsistent with the side-chain amide rotamer assignments for this residue in both subunits of the 1.14 Ǻ-resolution crystal structure. Although the side-chain amide of Gln12 can form a transient H-bond with the carboxyl group of Asp16, it is mobile. Consequently, the side-chain amide Gln12 adopts one conformation in subunit A of the 1.14 Ǻ-crystal structure but another in subunit B. The rotamer assignments of all other Asn/Gln side-chain amides are consistent with the differential isotope effects. In all, this analysis identifies two rotamer assignment errors in this high-resolution crystal structure. For the 1.6 Ǻ-resolution crystal structure, the rotamer assignment for Asn113 is correct for both subunits. The conformation of the side-chain amid of Gln12 in subunit A is completely different from that in subunit A of the 1.14 Ǻ-crystal structure, but that in subunit B is 180° rotated from that in subunit B of the 1.14 Ǻ-crystal structure, i.e. a flipping of the rotamer, underscoring the mobility of the side-chain amide. The flipping of the side-chain amide in the 1.6 Ǻ-resolution crystal structure allows it to form a hydrogen bond with the carboxyl group of Asp16. The side-chain amide rotamers of Gln55, Asn70, and Asn111 are all inconsistent with the differential isotope effects, requiring a flipping in order to form the H-bonds. In total, there are six side-chain amide rotamer assignment errors in this crystal structure as listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Asn/Gln side-chain rotamer errors in yCD crystal structures as recognized by differential isotope effects and the programs MolProbility and NQ-Flipper

| PDB Code | Subunit | NMR | MolProbility | NQ-Flipper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1P6O | A | Asn113 | Gln12[a], Asn113 | Gln12[a], Asn113 |

| B | Asn113 | Asn113 | Asn113, Gln123, Gln143 | |

| 1UAQ | A | Gln55, Asn70, Asn111 | Gln55, Asn70, Asn111, Gln143 | Asn70, Asn111, Gln143 |

| B | Gln55, Asn70, Asn111 | Asn39, Gln55, Asn70, Asn111, Gln123, Gln143 | Gln12[a], Asn39, Asn70, Asn111, Gln143, Gln150 |

According to the NMR and MD simulation data, the side-chain amide of Gln12 is mobile and can adopt a variety of rotamer conformations.

Because of the frequent errors in side-chain amide rotamer assignment in protein structures, computational approaches have developed for correcting the errors.[2,4,36] In particular, two web servers are available for the identification and correction of such errors, one server (MolProbity, http://molprobity.biochem.duke.edu/) using steric clashes after the addition of hydrogen atoms as a criterion for identifying such errors[38] and the other (NQ-Flipper, http://flipper.services.came.sbg.ac.at) using an empirical potential as a criterion for identifying such errors.[36] We submitted both yCD crystal structures to the web services to check their side-chain rotamers. The results are also listed in Table 2. Both MolProbity and NQ-Flipper identified three rotamer errors in the 1.14 Ǻ crystal structure, including one for Gln12, which is mobile. However, NQ-Flipper also identified two residues (Gln123 and Gln143) in subunit B for rotamer flipping but such flipping is not necessary for both residues upon visual inspection. With respect to the 1.14 Ǻ structure, MolProbity recognized all six rotamer assignment errors identified by the differential isotope effects but also recommended additional four residues for flipping deemed unnecessary upon visual inspection. NQ-Flipper correctly identified only four rotamer assignment errors. The two rotamer errors for Gln55 were not identified, but five Asn/Gln residues with apparently correct rotamers were recommended for rotamer flipping. With respect to the two yCD structures, MolProbity did a better job in identifying side-chain rotamer errors than NQ-Flipper, but both programs recommended some rotamers for flipping deemed unnecessary upon visual inspection.

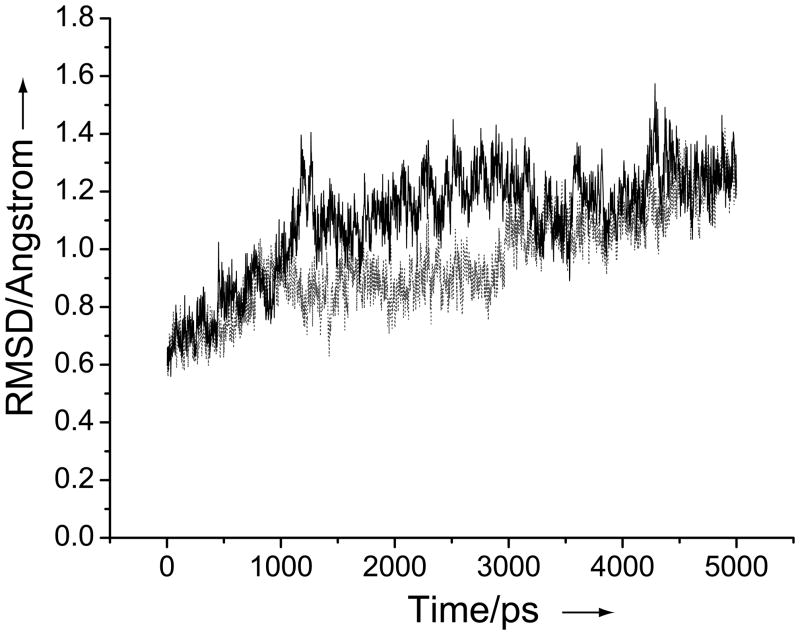

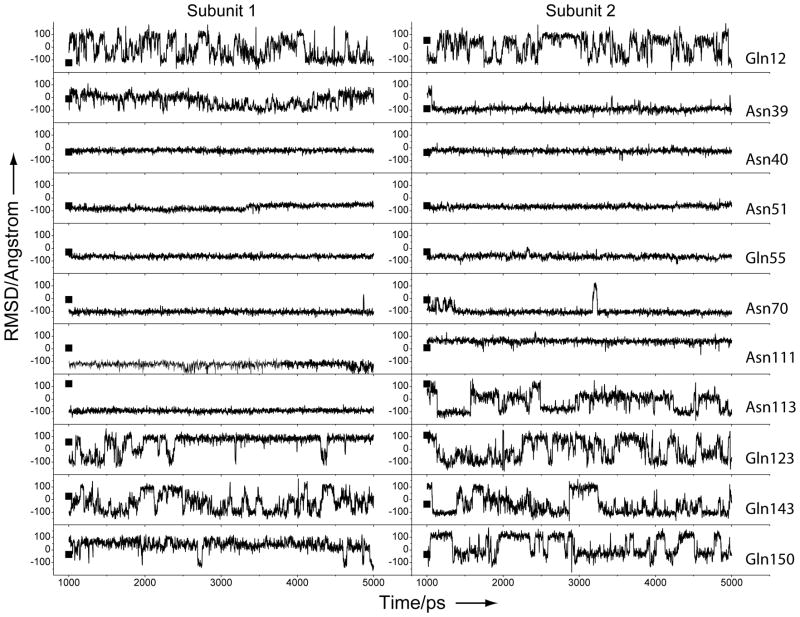

In order to better understand side-chain amide flipping, we performed a 5-ns MD simulation of the complex of yCD with the transition state analogue, which was essentially an extension of a previous MD analysis of yCD[39] with a newer version of the Amber MD package (version 8)[40] and force field (ff03).[41] It should be noted that no rotamer error correction was made to the initial structure for the MD simulation. The data analysis was based on individual subunits in order to get better statistics. Figure 5 shows the time evolution of the Cα atom RMSDs of two subunits with the coordinate of the crystal structure as the reference. The first 11 residues are not included in the analysis, as the N-terminal segment is highly mobile as in the previous MD simulations. The average Cα RMSD over the 5 ns MD simulation is 0.96 Å for subunit 1 and 1.10 Å for subunit 2. The average mass-weighted RMSD for all heavy atoms is 1.49 Å for subunit 1 and 1.62 Å for subunit 2. The result indicates that the structural changes in the protein are not large and the MD simulation is stable. Based on a trace-back RMSD analysis, the system reaches a stationary point at ~ 0.75 ns.

Figure 5.

Evolution of the Cα RMSDs of residues 15–158 of subunit 1 (solid line) and subunit 2 (dashed line) from those of the 1.14 Ǻ-resolution crystal structure during the entire MD simulation period.

Further data analysis, which focused on the motions of the side-chain amide groups, was performed on the trajectory extracted from the last 4 ns. The side-chain amide motions in this analysis were measured by the χ2 torsion angle (Cα–Cβ–Cγ–Oδ) for Asn and the χ3 torsion angle (Cβ–Cγ–Cδ–Oε) for Gln. The result is shown in Figure 6. It is clear that the side-chain amides of Gln12, Gln123, Gln143, and Gln150 can adopt a variety of rotamer conformations, as the torsion angles that define these rotamers vary widely in the MD simulation. The rapid motions of theses side-chain amides are consistent with their sharp NMR signals. Consequently, it is not meaningful to discuss the rotamer assignments and their errors. The side-chain amide of Asn39 in subunit 1 oscillates significantly around its torsion in the crystal structure but not in subunit 2. The side-chain amide of Asn113 flips in subunit 1 and remains in that conformation but oscillates significantly in subunit 2. The side-chain amides of Asn40, Asn51, Gln55, Asn70, and Asn111 behave like immobilized groups, in consistence with their broader NMR signals, although the side-chain amide of Asn111 assumes one conformation in subunit 1 but another in subunit 2. In particular, the rotamer assignment of Gln55 is incorrect in the 1.6 Ǻ-resolution crystal structure based on the differential isotope effects, the MD simulation, the 1.14 Ǻ-resolution crystal structure, and the MolProbity server analysis, but the NQ-Flipper server could not pick up the rotamer assignment error for this residue.

Figure 6.

Variations of the torsion angles for the side-chain amides in the last 4-ns MD simulation. The torsion angles measured from the 1.14 Ǻ-resolution crystal structure are indicated by solid squares. The subunit identities are labeled at the top and residue identities on the left side.

Conclusions

Protium/deuterium (H/D) isotope effects on chemical shifts can be transmitted either via covalent bonds or across hydrogen bonds and provide a sensitive means for studying H-bonding interactions, especially in large proteins where trans-hydrogen-bond scalar couplings are too small to be measured. In this study, the configuration and H-bonding network of side-chain amides in a 35 kDa protein are determined through measuring differential and across-H-bond H/D isotope effects with the IS-TROSY technique, which leads to a reliable recognition and correction of erroneous rotamers frequently found in protein structures. First, the differential two-bond isotope effects on carbonyl 13C′ shiftsΔ2Δ13C′ (ND) provide a reliable means for the configuration assignment for side-chain amides, as environmental effects (hydrogen bonds and charges etc.) are largely attenuated over the two bonds separating the carbon and hydrogen atoms and the isotope effects fall into a narrow range of positive values. Second and more importantly, the significant variations in the differential one-bond isotope effects on 15N chemical shiftsΔ1Δ15N(D) can be correlated with H-bonding interactions, particularly those involving charged acceptors. The differential one-bond isotope effects are additive with major contributions from intrinsic differential conjugative interactions between the E and Z configurations, H-bonding interactions, and charge effects. Furthermore, the pattern of across-H-bond H/D isotope effects can be mapped onto more complicated H-bonding networks involving bifurcated H-bonds. Third, the correlations between Δ1Δ15N(D) and H-bonding interactions afford a simple but effective means for the correction of erroneous side-chain amide rotamer assignments. Although several software programs and web-based services have been developed for the recognition and correction of erroneous side-chain amide rotamers, they are not always reliable, as demonstrated in the analysis of the side-chain amide rotamer assignments in the two high-resolution crystal structures of yCD. Very few experimental methods are available for this purpose. RDC data in conjunction with 15N relaxation measurements have been used for correcting Asn/Gln rotamers of solution NMR structures, but this method is laborious and applicable to only small proteins. In contrast, the rotamer correction via the differential isotope effects is not only robust but simple and can be applied to large proteins.

Experimental Section

Sample preparation and experimental conditions

The procedure for the isotope labeling and purification of yeast cytosine deaminase has been described.[42] NMR samples were prepared by dissolving the lyophilized yCD powder with the phosphate buffer (100 mM potassium), pH 7.0 (without isotope correction), in mixture solvents (either 95% H2O/5% D2O or 50%H2O/50%D2O). NaN3 (100 μM) and DSS (20 μM as an internal NMR reference) were added. The volume of all the samples was about 300 μL in Shigemi NMR microcells. Each NMR sample had yCD protein (~1.5 mM protomer) titrated with the transition state analogue 5FPy (20 mM). The samples in the mixture solvent were equilibrated at room temperature for at least a week before measuring. All NMR measurements were performed on a Bruker AVANCE 900 MHz NMR instrument at 25 °C using a TCI cryoprobe with z-axis gradient and an automatic tuning/matching unit. The raw data were processed with NMRPipe[43] and spectra were analyzed with NMRView.[44]

Measurements of differential and across-hydrogen-bond H/D isotope effects

The 15N–1H IS-TROSY experiment selectively detects semideuterated isotopomers of side-chain amides.[13–14] As depicted in Figure 1, the resonance of the 15N–HE{DZ} isotopomer has the 15N chemical shift modified by the one-bond 1Δ15N(DZ) isotope effect from the Z position and the 15N–HZ{DE} isotopomer by 1Δ15N(DE) from the E position. Since resonances of the fully protonated isotopomer, 15NH2, have been filtered out, direct measurements of 1Δ15N(DZ) and 1Δ15N(DE) are not possible from 15N–1H IS-TROSY spectra. However, the differential one-bond isotope effects, Δ1Δ15N(D) = 1Δ15N(DE) − 1Δ15N(DZ), could be measured directly although values are modified by the differential (|1JNHE{DZ}| − |1JNHZ{DE}|)/2 scalar coupling constants between the E and Z protons (see the schematic explanation of Figure 1). The magnitudes of one-bond scalar coupling constants, |1JNHE{DZ}| and |1JNHZ{DE}|, were measured from a 2D 15N–1H HSQC spectrum without using broad-bond 15N-decoupling in the direct dimension. The yCD NMR sample used for this measurement was in 75% H2O and 25% D2O otherwise the same buffer conditions as for other yCD samples that were declared in the last section. The ratio of H2O/D2O has been manipulated to obtain good signal intensities for both protonated and semi-deuterated isotopomers of side-chain amides while alleviating the potential complication caused by across-H-bond isotope effects. The one-bond scalar coupling constants in side-chain amides were directly measured from the 1H signal splittings of the corresponding semideuterated 15NH{D} isotopomers in this 15N-coupled HSQC spectrum (see Supporting Information). Similarly, the differential two-bond isotope effects,Δ2Δ13C′ (ND) = 2Δ13C′ (NDE) - 2Δ13C′ (NDZ), were measured from the 2D IS-TROSY-H(N)CO spectrum of yCD as shown in Figure 1B. Unlike the one-bone isotope effects as shown in Figure 1A, the two-bond isotope effects in Figure 1B are neat without any modification from scalar couplings, because no TROSY principle was adopted in the 13C dimension of the 2D IS-TROSY-H(N)CO experiment. Across-H-bond two-bond and three-bond H/D isotope effects on side-chain amide proton and 15N chemical shifts, 2hΔ1H and 3hΔ15N, respectively, mediated by H···O···H bifurcated H-bonds,[32] were measured either from the 15N–1H IS-TROSY spectrum (Figure 3) or in combination with the IS-TROSY-dispersed NOESY spectrum (Figure 2; see Supporting Information for the pulse sequence). The new observation of across-H-bond four-bond isotope effects on side-chain 13C′, 4hΔ13C′, were obtained from the 2D IS-TROSY-H(N)CO spectrum (Figure 4).

Although the magnitude of certain differential isotope effects as measured above may be smaller than the linewidth in the indirect dimension, the large separation in the direct (1H) dimension of the paired resonances of a side-chain amide makes measurement easy and accurate, which mimics the measurement of small scalar coupling constants in E.COSY type of experiments.[24] Indeed, duplicated measurements indicate that the standard error is as small as 5 ppb and the RMSD to the mean is only about 2 ppb. Markley and his colleagues have shown that amide D/H fractionation factors may be correlated to the strength of H-binding in proteins.[45] The correlation was established via measuring the intensity of amide resonances with a set of protein NMR samples in mixture solvents having different ratios of H2O/D2O. However, the ratio in principle has little to do the chemical shifts of individual resonances because solvent isotope effects on 15N chemical shifts are very small.

Molecular dynamics simulation

MD simulation on the complex of yCD with the transition state analogue was carried out essentially in the same way as previously described,[39] except that version 8 of the Amber MD package and the Amber 03 force field[46] were used for this simulation. Briefly, the starting structure was taken from the 1.14 Ǻ resolution crystal structure (PDB code: 1P6O).[34] Hydrogen atoms were added with the Insight II program. All ionizable residues were assigned to their normal protonated state at pH 7.0 except for His50, which was set as the protonated form, since its imidazole ring is hydrogen-bonded to two carboxyl groups (see Figure 3). The catalytic zinc ion was tetrahedrally coordinated with His62, Cys91, Cys94, and the transition state analogue. The sulfur atoms of Cys91 and Cys94 were deprotonated, and His 62 was in a deprotonated form with only Nε having proton attached to it. Explicit bonds between the zinc atom and its ligands were used and the force constants were the same as in our previous work.[39] The RESP charges of the zinc complex (Zn, His62, Cys91, Cys94, and the transition state analogue) were derived from a single-point quantum mechanics calculation (B3LYP/6-31+G*). Glu64 was also included in the calculation, as it may influence the charge distribution through a strong H-bond.

The protein complex was solvated by ~17,000 TIP3P water molecules in a periodic box with a minimum distance of 12.5 Å between the protein and the walls of the periodic box and was neutralized by the addition of four Na+ ions. Sander in Amber 8[40] and the ff03 force field were employed for the MD simulation. The system was first subjected to a two-stage energy minimization to eliminate steric clashes and two short MD runs for the system to reach the desired temperature and density. During the production MD run, the system was maintained at constant volume and temperature (300K) via Berendsen’s weak-coupling method.[47] Bond lengths involving hydrogen atoms were constrained by the Shake algorithm.[48] The Particle-Mesh-Ewald method was used to evaluate long-range electrostatic interactions.[49] A cutoff of 8.0 Å was used for the nonbonded pair list, which was updated every 25 steps. Coordinates were saved every other picosecond. The simulation results were analyzed with the PTRAJ module in Amber 8.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work made use of a Bruker AVANCE 900 MHz NMR spectrometer funded by Michigan Economic Development Corporation and Michigan State University. We thank Yan Wu for preparing NMR samples. The work was partially supported by NIH Grant GM58221 (H.Y.). A.L. was a recipient of the New Faculty Awards at MSU.

References

- 1.Creighton TE. Proteins: Structure and Molecular Properties. 2. Freeman, W. H. and Company; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Word JM, Lovell SC, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:1735–1747. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weichenberger CX, Sippl MJ. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1397–1398. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen PE. Magn Reson Chem. 2000;38:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dziembowska T, Hansen PE, Rozwadowski Z. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2004;45:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hibbert F, Emsley J. Adv Phys Org Chem. 1990;26:255–379. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Limbach H-H, Denisov GS, Golubev NS. Hydrogen bond isotope effects studied by NMR. In: Kohen A, Limbach H-H, editors. Isotope effects in chemistry and biology. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2006. pp. 193–230. [Google Scholar]

- 9.LiWang AC, Bax A. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:12864–12865. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ottiger M, Bax A. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:8070–8075. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meissner A, Briand J, Sørensen OW. J Biomol NMR. 1998;12:339–343. doi: 10.1023/A:1008254325702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meissner A, Sørensen OW. J Magn Reson. 1998;135:547–550. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu A, Li Y, Yao L, Yan H. J Biomol NMR. 2006;36:205–214. doi: 10.1007/s10858-006-9072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu A, Yao L, Li Y, Yan H. J Magn Reson. 2007;186:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jameson CJ. Bull Magn Reson. 1980;3:3–28. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tüchsen E, Hansen PE. Int J Biol Macromol. 1991;13:2–8. doi: 10.1016/0141-8130(91)90002-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sośnicki JG, Hansen PE. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:839–842. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sośnicki JG, Langaard M, Hansen PE. J Org Chem. 2007;72:4108–4116. doi: 10.1021/jo070285z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LeMaster DM, LaIuppa JC, Kushlan DM. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:863–870. doi: 10.1007/BF00398415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramanadham M, Sikka SK, Chidamboram R. Acta Crystallogr Sect B: Struct Crystallogr Cryst Chem. 1972;B 28:3000–3005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verbist JJ, Lehman MS, KTF, Hamilton WC. Acta Crystallogr Sect B: Struct Crystallogr Cryst Chem. 1972;B 28:3006–3013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herzfeld J, Roberts JE, Griffin RG. J Chem Phys. 1987;86:597–602. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pervushin K, Riek R, Wider G, Wüthrich K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12366–12371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griesinger C, Sørensen OW, Ernst RR. J Chem Phys. 1986;85:6837–6852. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feeney J, Partington P, Roberts GCK. J Magn Reson. 1974;13:268–274. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawkes GE, Randall EW, Hull WE, Gattegno D, Conti F. Biochemistry. 1978;17:3986–3992. doi: 10.1021/bi00612a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kainosho M, Tsuji T. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6273–6279. doi: 10.1021/bi00267a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tüchsen E, Hansen PE. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8568–8576. doi: 10.1021/bi00423a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansen PE, Tüchsen E. Acta Chem Scand. 1989;43:710–712. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bystrov VF. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 1976;10:41–81. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cai ML, Huang Y, Clore GM. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8642–8643. doi: 10.1021/ja0164475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu A, Lu Z, Wang J, Yao L, Li Y, Yan H. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2428–2429. doi: 10.1021/ja710114r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ko TP, Lin JJ, Hu CY, Hsu YH, Wang AHJ, Liaw SH. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19111–19117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300874200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ireton GC, Black ME, Stoddard BL. Structure. 2003;11:961–972. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abildgaard J, Hansen PE, Hansen AE. J Cell Biochem. 1995:68–68. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weichenberger CX, Sippl MJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W403–W406. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higman VA, Boyd J, Smith LJ, Redfield C. J Biomol NMR. 2004;30:327–346. doi: 10.1007/s10858-004-3218-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB, III, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W375–W383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yao L, Sklenak S, Yan H, Cukier RI. J Phys Chem. 2005;B 109:7500–7510. doi: 10.1021/jp044828+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Case DA, Cheatham TEI, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KMJ, Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods RJ. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duan Y, Wu C, Chowdhury S, Lee MC, Xiong GM, Zhang W, Yang R, Cieplak P, Luo R, Lee T, Caldwell J, Wang JM, Kollman P. J Comput Chem. 2003;24:1999–2012. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao L, Li Y, Wu Y, Liu A, Yan H. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5940–5947. doi: 10.1021/bi050095n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson BA, Blevins RA. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4:603–614. doi: 10.1007/BF00404272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loh SN, Markley JL. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1029–1036. doi: 10.1021/bi00170a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duan Y, Wu C, Chowdhury S, Lee MC, Xiong GM, Zhang W, Yang R, Cieplak P, Luo R, Lee T, Caldwell J, Wang JM, Kollman P. J Comput Chem. 2003;24:1999–2012. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, Vangunsteren WF, Dinola A, Haak JR. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. J Comput Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Essmann U, Perera L, Berkowitz ML, Darden T, Lee H, Pedersen LG. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.