Abstract

This work presents an investigation into the use of PRESAGE™ dosimeters with an optical-CT scanner as a 3D dosimetry system for quantitative verification of respiratory-gated treatments. The CIRS dynamic thorax phantom was modified to incorporate a moving PRESAGE™ dosimeter-simulating respiration motion in the lungs. A simple AP/PA lung treatment plan was delivered three times to the phantom containing a different but geometrically identical PRESAGE™ insert each time. Each delivery represented a treatment scenario: static, motion (free-breathing) and gated. The dose distributions, in the three dosimeters, were digitized by the optical-CT scanner. Improved optical-CT readout yielded an increased signal-to-noise ratio by a factor of 3 and decreased reconstruction artifacts compared with prior work. Independent measurements of dose distributions were obtained in the central plane using EBT film. Dose distributions were normalized to a point corresponding to the 100% isodose region prior to the measurement of dose profiles and gamma maps. These measurements were used to quantify the agreement between measured and ECLIPSE® dose distributions. Average gamma pass rates between PRESAGE™ and EBT were >99% (criteria 3% dose difference and 1.2 mm distance-to-agreement) for all three treatments. Gamma pass rates between PRESAGE™ and ECLIPSE® 3D dose distributions showed excellent agreement for the gated treatment (100% pass rate), but poor for the motion scenario (85% pass rate). This work demonstrates the feasibility of using PRESAGE™/optical-CT 3D dosimetry to verify gating-enabled radiation treatments. The capability of the Varian gating system to compensate for motion in this treatment scenario was demonstrated.

1. Introduction

The necessity for quality assurance (QA) in gated radiation therapy treatments has been established (Niroomand-Rad et al 1998, Jiang et al 2007). However, the development of QA methods has not kept pace with the innovations in gating techniques. American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM) Task Group 76 outlined the necessity for a respiratory gating QA device to adequately simulate cyclical motion that is similar to human respiration and provide an adequate number of detectors for dose analysis. A variety of dynamic, high-resolution QA devices have surfaced over the years (Nelms et al 2007, Nakayama et al 2008, Nioutsikou et al 2006, Berbeco et al 2005, Keall et al 2006b, Saw et al 2007). However, each technology is inherently two-dimensional (2D) and can only offer QA analysis in one plane of a three-dimensional (3D) dose distribution. 3D QA analysis of a dose distribution is highly desirable since a 2D plane does not represent points throughout the entire dose distribution in the presence of nonlinear respiratory motion. Gel dosimetry has been shown to be a viable option for 3D gated therapy dosimetry QA (Ceberg et al 2008, Mansson et al 2006, Ravindran et al 2009). Gel dosimeters however have been reported to have undesirable characteristics: PAG dosimeters are susceptible to atmospheric oxygen (O2) that inhibits the polymerization reaction, and MAGIC dosimeters are formulated with toxic chemicals (Baldock 2009). As an alternative to gel dosimetry, PRESAGE™ dosimeters were investigated. Key advantages of PRESAGE™ dosimeters include (1) very low scatter due to absorption medium, (2) robustness to laboratory environment (i.e. no O2 sensitivity) and (3) no need for external container which provides better dosimeter edge resolution through improved refractive index (RI) matching (Guo et al 2006b). In this work we investigate the feasibility of PRESAGE™, a 3D plastic dosimeter, with much improved characteristics as a viable option for respiratory-gated 3D QA verification.

The PREASAGE™/optical-CT dosimetry system has previously been developed and tested for several applications of treatment verification, namely 3D conformal (Guo et al 2006a) and IMRT (Oldham et al 2006, 2008, Sakhalkar et al 2009b); this work represents the first attempt toward validating the use of PRESAGE™ dosimetry for the verification of a gated treatment. The PRESAGE™/optical-CT dosimetry system consists of a radiochromic plastic dosimeter (PRESAGE™) and a novel fast, high-resolution, optical-computed tomography (optical-CT) scanner for dose readout. PRESAGE™ is a 3D leuko-dye doped dosimeter that is clear until irradiated, and once irradiated it changes color proportionately to absorbed dose (Adamovics et al 2005, Adamovics and Maryanski 2003, 2004, 2006). In a recent report (Sakhalkar et al 2009a), PRESAGE™ was shown to be extremely robust with an intra-dosimeter radiochromic response variability of 2%, temporal stability for ~90 h post-irradiation and a reproducibility response of 2% was measured at all investigated dose levels. The optical-CT scanner is a dose readout system that utilizes parallel light and telecentric lens geometry for image readout as previously investigated (Sakhalkar and Oldham 2008). The scanner is capable of acquiring a complete 3D dataset in ~5 min. The scanner is based on telecentric optics to ensure accurate projection imaging that minimizes artifacts from scattered and stray-light sources as first demonstrated by Doran et al (2001), Krstajic and Doran (2006) and (2007) and allows isotropic high-resolution 3D dose readout.

This work presents results from the ongoing improvement of the fast, high-resolution optical-CT scanner and the results of three treatment scenarios: static, motion (free breathing) and gated were measured and compared to their respective calculated ECLIPSE® treatment plans. The PRESAGE™ measurements were benchmarked against radiochromic EBT film. EBT film was considered the gold standard in light of prior studies demonstrating its accuracy (Devic et al 2005, Lynch et al 2006, Paelinck et al 2007, Guo et al 2006a).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. PRESAGE™ 3D dosimeter and dynamic thorax phantom

PRESAGE™ dosimeters (Heuris Pharma LLC, Skillman, NJ) have been previously characterized for 3D dosimetry (Guo et al 2006b, Sakhalkar et al 2009a). Specific to this study, the PRESAGE™ formulation had the following properties: Zeff of 8.3, density of 1.07 g cm−3 and a CT number of ~170. Three identical homogenous cylindrical PRESAGE™ dosimeters (5 cm diameter × 5 cm length) were designed to fit into the dynamic thorax phantom (CIRS Inc., Norfolk, VA). The PRESAGE™ dosimeters were maintained at a temperature of ~4 °C before and after irradiation. The dosimeter was allowed to reacclimatize to room temperature, ~22 °C, before irradiation and optical-CT readout. Approximately 12 h was allowed for the post-irradiation polymerization reaction to stabilize before optical-CT readout.

The dynamic thorax phantom (referred to as the phantom) is a phantom that represents a heterogeneous human thorax in proportion and composition. The phantom consists of a tissue equivalent lung, cortical and trabecular bone and water material, figures 1(A), (B). The phantom simulates motion by oscillating a rod made of lung-equivalent material. The rod was designed to hold 3D dosimeters with a diameter of ~5 cm. The rod was modified to accept a locking mechanism that was manufactured on the base of the PRESAGE™ dosimeter, figure 1(C). The locking mechanism allowed for consistent realignment of the dosimeters within the lung rod insert. All motion studies presented in this work utilized a customized sinusoidal motion profile with 4.5 s cycle time and 15 mm superior to inferior motion that was created to simulate a simple, idealized patient respiration pattern with maximum target displacement in the coronal plane (Dietrich et al 2005, Shirato et al 2000, Keall et al 2006a).

Figure 1.

(A) A CIRS dynamic thorax phantom is shown with a lung tissue-equivalent rod. The cylindrical three-dimensional PRESAGE™ dosimeter is placed within the rod and oscillated to simulate respiration motion in the lung. (B) A central CT slice of the phantom shows prominent anatomy with the PRESAGE™ dosimeter in the lung. The PRESAGE™ dosimeter was manufactured with a docking mechanism (C) to allow for accurate repositioning within the lung rod.

2.2. Optical-CT scanning of the PRESAGE™ dosimeter

2.2.1. Optical-CT scanner readout

PRESAGE™ dose readout was performed using an in-house fast, high-resolution optical-CT scanner that used a charge coupled device (CCD) area detector for signal digitization (Sakhalkar and Oldham 2008), figure 2. In summary, the PRESAGE™ dosimeter is placed on a rotating stage inside an anti-reflection-coated glass aquarium. The aquarium is filled with a RI-matched fluid comprising a mixture of octyl salicylate, methoxy octyl cinnamate and a small amount (3–4 drops) of green oil-based dye. The dye was used to equalize the light attenuation between the dosimeter and the fluid. This optimized the dynamic range of the scanning system. Incident illumination was provided by a 633 nm LED array (Leutron Vision Inc., Burligton, MA). The light source was matched to the peak sensitivity of the PRESAGE™ dosimeters (Guo et al 2006a, 2006b). Projection images were acquired by an A-102f 12 bit monochrome CCD camera (Basler Vision Technologies, Ahrensburg, Germany) that digitized at a resolution of 1392 × 1040 pixel. The camera was coupled to a TECHSPEC 55–349 telecentric lens system (Edmund Optics Inc., Barrington, NJ). A LABVIEW (National Instruments Corp., Austin, TX) script controlled a step-and-image acquisition scheme in which the stage made an incremental rotation after an image from the camera was written to disk. The optical-CT maximum field of view was ~7 × 7 cm2, which was limited by the physical size of the telecentric lens. Commercial telecentric lenses were available with a field of view up to 30 cm, though at a significantly increased price. Commercially available tomographic reconstruction software (COBRA, Exxim Corp., Pleasanton, CA), which used a filtered back projection reconstruction algorithm, was used for reconstructing the images readout by the optical-CT scanner. The projection images loaded into the COBRA software were down sampled from 1392 × 1040 pixel to 160 × 96 pixel using a bilinear interpolation with a 2 × 2 pixel kernel to achieve an isotropic spatial resolution of 0.4 mm.

Figure 2.

A simplified schematic depicting light rays through the CCD-based optical-CT scanner. Projection images through the PRESAGE™ dosimeter are focused onto the CCD camera chip using a tertiary telecentric lens system (acceptance angle <0.1°). A two-dimensional projection image was acquired at each rotation step.

2.2.2. Improved optical-CT scanning technique

Sakhalkar et al (2008) demonstrated accurate 3D dosimetry in a novel bench top scanner incorporating telecentric optics. Three limiting artifacts were observed in the reconstructed optical-CT images: concentric rings, high noise-to-signal and significant edge artifact. These three artifacts were minimized in the present work through the following improved scanning technique.

The concentric ring artifact was attributed to relatively stationary structures in all projection images due to particulates in the fluid and defects (e.g. scratches) on the aquarium wall. A 30 μm stainless steel wire mesh filter was used to improve the removal of fluid particulates. Increased fluid filtration was necessary to further remove microscopic debris from the fluid to improve the image signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). To correct for aquarium wall defects, a series of 50 flood field images were taken. A flood field image consisted of a full aquarium or RI fluid without a dosimeter in place. One image was generated from a mean of the 50 flood field images and was subtracted from each projection image before 3D image reconstruction.

RI-matching fluid filtration and flood and dark field subtraction improved the SNR by decreasing the high noise-to-signal ratio in the reconstructed images. Dark field images were generated and subtracted from the individual projection images prior to 3D image reconstruction. A dark field image measured the underlying signal generated by thermally induced electrons and captured in the non-cooled CCD camera’s photosites. The acquisition of the 3D data set with a non-cooled CCD camera was limited in its dynamic range with increased acquisition time due to the thermal noise. To account for the thermal noise contribution of each projection image, the lens cap was placed over the lens and an identical number of dark fields were captured matching the number and time for the projection images. However, one mean image of only 100 consecutively acquired images (acquired in ~1 min) was determined to be sufficient to account for the overall thermal noise contribution to a whole PRESAGE™ scan acquired in ~5–10 min.

The edge enhancement artifact was attributed to imperfect RI matching between the fluid and dosimeter and refracted light rays emerging from the dosimeter boundaries as accepted parallel light rays into the telecentric lens system. The RI of the fluid bath was adjusted adding a small amount of methoxy octyl cinnamate (RI value 1.542) to the octyl salicylate (RI value of 1.502) to match the RI of the PRESAGE™ dosimeter (RI value 1.503). Even with the fluid bath and dosimeter RI values matched, the edges of the dosimeter were visible due to non-parallel light, incident on the dosimeter boundaries, refracted such that the angle of refraction of the incident light was within the acceptance angle of the telecentric lens system and thus accepted for image formation. Telecentric lens systems are manufactured to allow only parallel light to be used for image formation. The acceptance angle, or tolerance of the telecentric lens system for non-parallel light, was considered double the angle for parallel light which was accepted for image formation (Krstajic and Doran 2006). The acceptance angle for the telecentric lens system used in this investigation was <0.1° (as quoted by the manufacturer). It is possible that non-parallel light from the diffuse LED source could scatter into the parallel plane, and thus contribute to the image; this component is small due to the high transparency of PRESAGE™, but any component was further reduced by placing the LED source at the end of the bench (~150 cm from the PRESAGE™ dosimeter). A smaller scanner could be achieved by replacing the LED source with a telecentric light source.

2.3. Treatment planning

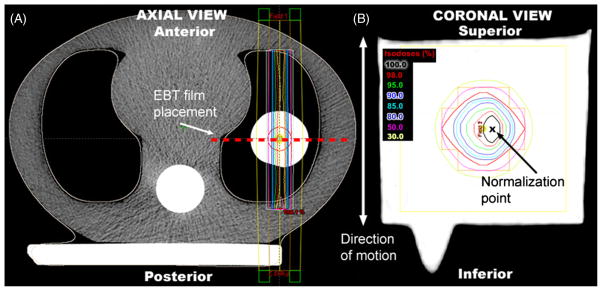

Three treatment scenarios were planned and delivered: (1) static delivery where the PRESAGE™ dosimeter was stationary during treatment, (2) motion delivery ‘free breathing’ where the PRESAGE™ dosimeter was in motion during treatment and (3) gated delivery where the PRESAGE™ dosimeter was irradiated while in motion, but gated to treat at a specific phase in the breathing cycle. For each of the three treatment scenarios, small field parallel–opposed anterior–posterior (AP/PA) beams were planned using the ECLIPSE® treatment planning system (Varian Med. Systems, Palo Alto, CA). AP/PA beams allowed for a realistic lung treatment setup that maximized the accuracy for independent verification of EBT film by rendering film placement insensitive to positional differences in the AP direction, figure 3(A). Small field sizes (~2 cm) were planned to capture the full extent of the delivered dose distribution in the PRESAGE™ dosimeter over the full range of dosimeter displacement due to the phantom motion. Field sizes were on the order of sizes used for lung stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS).

Figure 3.

A central slice axial view of the dynamic thorax phantom with PRESAGE™ in situ (A) is shown with the AP/PA beam configuration. EBT film was placed along the central axis of the PRESAGE™ dosimeter (dashed line in (A)) in the coronal plane (B). The approximate normalization point is shown in (B). Small radiosurgery type field sizes (~2 cm) were used to capture the full extent of the delivered dose distribution in the PRESAGE™ dosimeters while the phantom was in motion.

2.3.1. CT scanning procedures

The phantom, including a PRESAGE™ dosimeter in situ, was CT scanned using a multislice CT scanner (Lightspeed, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). The CT scan protocol for the static scenario consisted of a helical four-slice mode with 5 mm collimation at 1.25 mm resolution per slice. The CT scan for the gated scenario (4DCT scan) consisted of an over-sampled CT acquisition at each slice (Rietzel et al 2005). This involved continuously scanning each slice in axial ciné four-slice mode for 5.0 s to scan during one full breathing cycle (4.5 s). The slice collimation and resolution used were similar to the static scan protocol. Varian’s Real-time Position Management software (RPM) recorded a breathing profile concurrent with the 4DCT scan. The RPM tracked the motion of the phantom using an infrared (IR) camera and an external IR reflective marker mounted on top of the phantom. Advantage 4D software (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) binned the acquired images retrospectively according to spatiotemporally recorded time signatures and table positions. Reconstructed images were assigned to one of ten specific respiratory phase bins, with a ±5% spatiotemporal tolerance for sorting. Each sorted bin was reconstructed into a 3D data set representing spatiotemporally similar images.

2.3.2. Treatment and delivery

Two identical treatment plans were created using ECLIPSE® figure 3. The calculation algorithm used in ECLIPSE® was AAA 8223 which consisted of a calculation matrix of 1.25 mm. The first plan was developed using the static CT scan and was used to deliver the static and motion treatment scenarios. The second plan was developed using the 4DCT scan where phases nine, zero and one (9-0-1) of the ten respiratory phases were selected and used as the ‘gate’ for dose calculation and beam delivery of the gated treatment scenario. Phases 9-0-1 represent the point of maximum exhalation. For the delivery of the gated plan, the RPM software was used to track the motion of the externally mounted marker. This respiratory trace was matched with the trace acquired during the 4DCT scan and enabled ‘beam on’ for the LINAC when the phantom entered into phase nine of the 9-0-1 phases of the respiratory cycle.

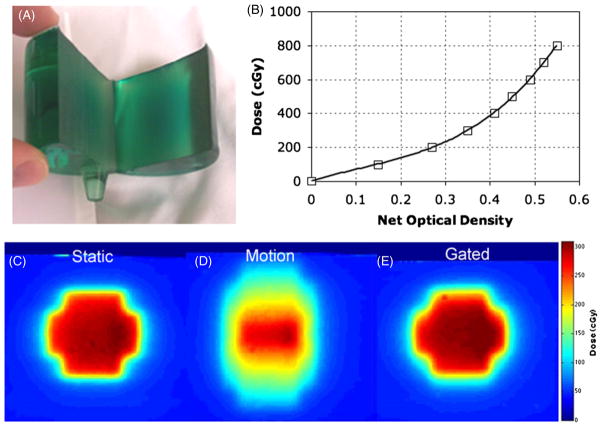

2.4. Independent EBT film measurement

Independent verification of the dose distribution was achieved using EBT film (International Specialty Products, Wayne, NJ). EBT film was chosen for its practical convenience as a self-developing radiochromic film, energy and directional independence, and temporal stability (Guo et al 2006a). A PRESAGE™ dosimeter was cut at its central, long axis, which represented the coronal plane, and a piece of EBT film was placed between the two PRESAGE™ halves, figure 4(A). The PRESAGE™ dosimeter, with EBT film in situ, was placed in the phantom, and the treatment plans for the three scenarios were delivered to the EBT film inserts, figures 4(C)–(E). A calibration curve was prepared at the time of experimental irradiation (Guo et al 2006a), figure 4(B). The films were digitized using a 48-bit transmission/reflection flatbed photo-scanner (Perfection 4990 Photo, Epson, Japan). Each film was scanned in transmission mode at a resolution of 72 pixels in−1 (0.4 mm pixel) with no color corrections and saved as RGB uncompressed Tagged Image File Format. Corrections were made for scanner light non-uniformities (Devic et al 2004, 2005, Lynch et al 2006, Paelinck et al 2007). The EPSON scanner employed a Xenon gas cold cathode fluorescent lamp (as quoted by the manufacture) with spectral emission range between 400 and 750 nm. EBT films were analyzed using the red channel (of the RGB channels) due to the film’s maximum absorption that occurred at 635 nm (Devic et al 2007). The traditional red channel of the RGB format was focused on the 580–700 nm light wavelength range with an approximate center wavelength of 640 nm. EBT film response was converted to dose using the fitting function of the film’s calibration data. The EBT film dose responses were then normalized for inter dosimeter comparison.

Figure 4.

Independent measurement of dose was made with EBT film inside a PRESAGE™ dosimeter (A) in the coronal plane. The EBT film calibration curve (B) showed a goodness of fit (R2) of 0.9984. Distributions of the calibrated EBT film for the three treatment scenarios are shown: static (C), motion (D) and gated (E).

2.5. Data analysis

Three types of data were available for analysis: (1) 3D static, motion and gated PRESAGE™ dose distributions; (2) calculated 3D static and gated ECLIPSE® dose distributions and (3) 2D static, motion and gated EBT film central coronal plane dose distributions. The calculated static distribution from ECLIPSE® was compared to measured static and motion distributions from PRESAGE™ and EBT. The calculated gated distribution from ECLIPSE® was compared to the measured gated distributions from PRESAGE™ and EBT. Once all three data sets were spatially registered, an identical normalization point was chosen, see figure 3(B) for inter-dosimeter comparison. Film post-processing, dosimeter registration and data analysis were performed using CERR (Washington University, St Louis, MO), a Matlab-based software. Though, Babic et al (2008) demonstrated a successful implementation of a 3D gamma analysis, at the time of this investigation, the CERR software did not have a true 3D gamma calculation, so all quantitative analysis between datasets were restricted to a slice-by-slice analysis using line profiles and 2D gamma maps (Low and Dempsey 2003, Low et al 1998). The eventual use of 3D absolute dose analysis is currently being developed and will be the topic of future work. The analysis criteria for the gamma map were set at 3% dose difference and 1.2 mm distance-to-agreement (3%–1.2 mm). For the gamma maps, the dose difference acceptance criterion represents a more stringent criterion than currently used for the RTOG head and neck IMRT protocols (7%–4 mm) (Ibbott et al 2006). The distance-to-agreement acceptance criterion of 1.2 mm was used to match the dose resolution of the calculated ECLIPSE® dose distribution and to more accurately reflect the differences in dose distribution over small distances as represented in this work. Comparisons with EBT film (gold standard) were used to establish PRESAGE™ feasibility where 3D comparisons with PRESAGE™ and ECLIPSE® were used as a preliminary means to measure gating treatment efficacy.

3. Results

3.1. Improvements in the optical-CT scanning technique

A line profile through a reconstructed PRESAGE™ dosimeter, figure 5(A), with and without the improved scanning technique is plotted in figure 5(B). The line profile without the improved scanning technique measured 12% variability in the normalized signal, while the line profile with the improved scanning technique measured 4% variability. The improved scanning technique measured a factor of 3 increase in the SNR. The edge artifact decreased from 5 mm to ~2 mm through the improved scanning technique and setup geometry, figure 2.

Figure 5.

Reconstructed axial optical density map from the PRESAGE™ dosimeter showing the AP/PA beam configuration (A). Line profile (B) shows the improved optical-CT dose readout technique (‘new technique’) with noise reduction compared to the ‘old technique’.

3.2. Dose distributions in the static, motion and gated treatment scenarios

PRESAGE™, EBT film and ECLIPSE® dose distributions are plotted as isodose contour mappings for the three treatment scenarios in figure 6 with corresponding gamma map comparisons shown in figure 7 and line profiles in figure 8. Line profiles were taken along the representative dashed lines in figure 6(I). An inter-dosimeter comparison between PRESAGE™ and EBT film distributions was compared for the static, motion and gated treatment scenarios. Pass rates (3%–1.2 mm) of 99.6%, 99.9% and 99.4% were calculated for the static, motion and gated treatments, respectively, as are shown in figures 7(A)–(C).

Figure 6.

Isodose lines in the central coronal plane (shown in figure 3(A)) demonstrate the maximum motion effect. Note that the ECLIPSE® distributions are unchanged since the distributions were calculated from static CT images for (C and F) and from one of the ten scanned respiratory image sets (I).

Figure 7.

Gamma maps (3%–1.2 mm) in the central coronal plane shown in figure 3(A) indicating pass rates. Values of gamma >1 indicate failure of one or both of the gamma criteria. Excellent agreement was observed between PRESAGE™ and EBT film (A–C) for all three treatment scenarios that establishes the feasibility of the PRESAGE™/optical-CT dosimetry system. Good agreement between measured gated distribution and ECLIPSE® demonstrates the effectiveness of Varian’s gating system at delivering accurate dose distributions by reducing the motion-induced errors (E and H).

Figure 8.

Line profiles of the ECLIPSE®, PRESAGE™ and EBT dose distributions, along the dashed line shown in figure 6(I), are shown for all three treatment scenarios. A left–right elongation of the dose distribution, measured by both PRESAGE™ and EBT film, is visible in the dose profiles (A, D, G). A possible explanation of the elongation effect is increased penumbral blurring when the radiation beam passes through the rounded ends of the Varian’s MLC leaves, as reported in Butson et al (2003).

Close examination of the dose distributions for the static and gated treatment scenarios reveal good agreement between PRESAGE™, EBT film and ECLIPSE® as is evident by their similarly shaped and positioned isodose contour maps in figures 6((A)–(C) and (G)–(I)) and closely aligned line profiles in figures 8((A)–(C) and (G)–(I)). Whereas the motion dose distributions, figures 6(D), (E), exhibited broadening of the penumbral regions in both the superior to inferior, figure 8(E), and left–right, figure 8(D), directions as anticipated due to the phantom motion not modeled in the ECLIPSE® calculations, figure 6(F). The measured dose distributions were compared versus the calculated ECLIPSE® distributions using the gamma map criteria. The pass rates for the ECLIPSE® and PRESAGE™ distributions were compared for the static, motion and gated treatment scenarios: 84.7%, 84.5% and 100.0%, respectively, and the ECLIPSE® and EBT pass rates are 85.5%, 79.8% and 86.0%, respectively.

4. Discussion

An interesting point to note is that the pass rate is higher in the gated scenario than in the static scenario (compare figures 7(D) and (F)). This is attributed to the fact that the ECLIPSE® dose distribution incorporates effectively a convolution ‘blurring component’ due to the finite measurement volume of the ion chamber used to acquire the commissioning data. This slight blurring of the dose distribution is not observed in the static measurement of PRESAGE™, but a similar magnitude of blur is observed in the gated PRESAGE™ measurement, due to dosimeter motion during the finite time width of the gating window.

Both the PRESAGE™ and EBT film distributions measured an ~2 mm per side elongation in the left–right directions, as shown in figure 8(A), (G), which is not consistent with the calculated ECLIPSE® distributions. The elongation is only measured in the direction parallel to the MLC leaves. However, the superior and inferior ends of the distribution, which are aligned perpendicular to the edges of the MLC leaves, do not measure the same dose elongation (figure 8(B), (H)). The left–right elongation of the dose distributions may be attributed to the x-ray beam passing through the end of a rounded Varian MLC leaf which has been shown to increase penumbral blurring by ~2 mm compared to x-rays exposed to the edge of the same MLC leaf (Butson et al 2003).

One possible limitation of this work was the necessity to normalize the dose distributions for comparison. Normalization forces agreement at one dose level and may limit the value of subsequent analyses by masking possible dose differences where large discrepancies in dose magnitude exist. Therefore, the analysis of data sets using absolute dose distributions is generally preferable when available. In the case of PRESAGE™, calibration to a given dose may be achieved from irradiation of small volumes of PRESAGE™ from the same batch. This method of establishing a calibration function using small volumes to calibrate a large 3D volume has been shown to introduce errors when comparing dose distributions (MacDougall et al 2008). The extent of this volume effect for PRESAGE™ calibration has not yet been established in sufficient detail to know exactly how accurate the calibration is; a detailed study of the volume effect is part of an ongoing study. The uncertainty of the volume effect on the accuracy of the PRESAGE™ dosimeter analysis required the use of normalization as a means to compare PRESAGE™ with ECLIPSE® and EBT film dose distributions. However, the precise linearity of the PRESAGE™ dose response has been extensively confirmed (Guo et al 2006b, Sakhalkar et al 2009a). In the present paper, the given dose at the normalization point in the PRESAGE™ dosimeter was within the calibration uncertainty of the planned dose as determined from the film measurements, shown in figure 9. We therefore conclude that the use of PRESAGE™ as a relative dosimeter, by normalizing to a point corresponding to the 100% isodose region of the planned dose distribution in the coronal plane and exploiting the strength of the linearity of PRESAGE™ response, will not introduce any limitation on the data analysis and will circumvent the demonstrated volume effect error.

Figure 9.

Absolute dose comparisons are presented between ECLIPSE® (A) and the calibrated EBT film for the three treatment scenarios (figures 4(C)–(E)). Superior–inferior (B) and lateral (C) line profiles, taken along the dashed lines shown in (A), compare overall ECLIPSE® and film absolute dose agreement. Generally, the calibrated film and calculated ECLIPSE® dose line profiles demonstrate a similar magnitude of dose and profile shape (except for the film’s motion scenario). Eclipse and film dose difference mappings show, for the three treatment scenarios—static (D), motion (E) and gated (F), good agreement in dose delivery for the central, shallow dose gradient region, but poor agreement for the peripheral, steep dose gradients. The static and gated film dose difference map, shown in (G), demonstrates the ability of the gating technique to minimize motion-induced dose blurring in surrounding regions of the planned target volume. Superior–inferior (H) and lateral (I) line profiles taken from the static and gated film treatment scenario dose distributions (figures 4(C) and (E)) also show the high agreement of the gated treatment with the static scenario.

This work presents the first application of PRESAGE™/optical-CT 3D dosimetry system to the verification of a simple gating treatment and lays the foundation for more advanced gating work. We envision a role for PRESAGE™ (and any of the other 3D dosimetry approaches) as a final whole-system verification test during the commissioning stage. There may also be a future role in repeat or periodic QA of various techniques, i.e. respiratory gating, IMRT, RapidArc™, etc, but probably not on a per patient basis unless the costs and convenience of optical-CT readout improve.

5. Conclusion

Comparison between PRESAGE™ and EBT film showed excellent agreement for the three treatment scenarios. The average pass rate was >99% with respect to gamma map criteria of 3%–1.2 mm. Although the gated treatment plan was simple, this result establishes the feasibility of the PRESAGE™/optical-CT dosimetry system for verifying gating treatments and lays the groundwork for future work to investigate more complex gated treatments. Significant differences were observed between the static planned dose distribution and the measured dose distribution in the presence of breathing motion. Varian’s gating system was shown to correctly reduce this motion error through the implementation of a standard gating technique. Improvements in the optical-CT scanner design and acquisition techniques led to reduced edge artifacts and a factor of 3 increase in the SNR while maintaining scanner readout times on the order of ~5–10 min.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express gratitude to Dr John Adamovics for providing the PRESAGE™ inserts, and to Jacqueline Maurer for her help with the CT scanning. This work was made possible by NIH grant number ROI CA100835 and NIH grant number NIBIB T32 EB007185.

References

- Adamovics J, Dietrich J, Jordan K. Enhanced performance of PRESAGE—sensitivity, and post-irradiation stability. Med Phys. 2005;32:1. [Google Scholar]

- Adamovics J, Maryanski M. New 3D radiochromic solid polymer dosimeter from leuco dyes and a transparent polymeric matrix. Med Phys. 2003;30:1. [Google Scholar]

- Adamovics J, Maryanski M. OCT scanning properties of PRESAGE—a 3D radiochromic solid polymer dosimeter. Med Phys. 2004;31:1. [Google Scholar]

- Adamovics J, Maryanski MJ. Characterisation of PRESAGE: a new 3D radiochromic solid polymer dosemeter for ionising radiation. Radiat Prot Dosim. 2006;120:107–12. doi: 10.1093/rpd/nci555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babic S, Battista J, Jordan K. Three-dimensional dose verification for intensity-modulated radiation therapy in the Radiological Physics Centre head-and-neck phantom using optical computed tomography scans of ferrous xylenol-orange gel dosimeters. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1281–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldock C. Historical overview of the development of gel dosimetry: another personal perspective. J Phys: Conf Ser. 2009;164:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Berbeco RI, Neicu T, Rietzel E, Chen GT, Jiang SB. A technique for respiratory-gated radiotherapy treatment verification with an EPID in cine mode. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:3669–79. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/16/002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butson MJ, Yu PK, Cheung T. Rounded end multi-leaf penumbral measurements with radiochromic film. Phys Med Biol. 2003;48:N247–52. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/48/17/402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceberg S, Karlsson A, Gustavsson H, Wittgren L, Back SA. Verification of dynamic radiotherapy: the potential for 3D dosimetry under respiratory-like motion using polymer gel. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53:N387–96. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/20/N02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devic S, Seuntjens J, Hegyi G, Podgorsak EB, Soares CG, Kirov AS, Ali I, Williamson JF, Elizondo A. Dosimetric properties of improved GafChromic films for seven different digitizers. Med Phys. 2004;31:2392–401. doi: 10.1118/1.1776691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devic S, Seuntjens J, Sham E, Podgorsak EB, Schmidtlein CR, Kirov AS, Soares CG. Precise radiochromic film dosimetry using a flat-bed document scanner. Med Phys. 2005;32:2245–53. doi: 10.1118/1.1929253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devic S, Tomic N, Pang Z, Seuntjens J, Podgorsak EB, Soares CG. Absorption spectroscopy of EBT model GAFCHROMIC film. Med Phys. 2007;34:112–8. doi: 10.1118/1.2400615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich L, Tucking T, Nill S, Oelfke U. Compensation for respiratory motion by gated radiotherapy: an experimental study. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:2405–14. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/10/015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran SJ, Koerkamp KK, Bero MA, Jenneson P, Morton EJ, Gilboy WB. A CCD-based optical CT scanner for high-resolution 3D imaging of radiation dose distributions: equipment specifications, optical simulations and preliminary results. Phys Med Biol. 2001;46:3191–213. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/46/12/309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P, Adamovics J, Oldham M. A practical three-dimensional dosimetry system for radiation therapy. Med Phys. 2006a;33:3962–72. doi: 10.1118/1.2349686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo PY, Adamovics JA, Oldham M. Characterization of a new radiochromic three-dimensional dosimeter. Med Phys. 2006b;33:1338–45. doi: 10.1118/1.2192888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibbott GS, Molineu A, Followill DS. Independent evaluations of IMRT through the use of an anthropomorphic phantom. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2006;5:481–7. doi: 10.1177/153303460600500504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang SB, Wolfgang J, Mageras GS. Quality assurance challenges for motion-adaptive radiation therapy: gating, breath holding, and four-dimensional computed tomography. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;71:S103–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.07.2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keall PJ, et al. The management of respiratory motion in radiation oncology report of AAPM Task Group 76. Med Phys. 2006a;33:3874–900. doi: 10.1118/1.2349696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keall PJ, Vedam SS, George R, Bartee C, Siebers J, Lerma F, Weiss E, Chung T. The clinical implementation of respiratory-gated intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Med Dosim. 2006b;31:152–62. doi: 10.1016/j.meddos.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krstajic N, Doran SJ. Focusing optics of a parallel beam CCD optical tomography apparatus for 3D radiation gel dosimetry. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51:2055–75. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/8/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krstajic N, Doran SJ. Characterization of a parallel-beam CCD optical-CT apparatus for 3D radiation dosimetry. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:3693–713. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/13/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low DA, Dempsey JF. Evaluation of the gamma dose distribution comparison method. Med Phys. 2003;30:2455–64. doi: 10.1118/1.1598711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low DA, Harms WB, Mutic S, Purdy JA. A technique for the quantitative evaluation of dose distributions. Med Phys. 1998;25:656–61. doi: 10.1118/1.598248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch BD, Kozelka J, Ranade MK, Li JG, Simon WE, Dempsey JF. Important considerations for radiochromic film dosimetry with flatbed CCD scanners and EBT GAFCHROMIC film. Med Phys. 2006;33:4551–6. doi: 10.1118/1.2370505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall ND, Miquel ME, Keevil SF. Effects of phantom volume and shape on the accuracy of MRI BANG gel dosimetry using BANG3. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:46–50. doi: 10.1259/bjr/71353258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansson S, Karlsson A, Gustavsson H, Christensson J, Back SA. Dosimetric verification of breathing adapted radiotherapy using polymer gel. J Phys: Conf Ser. 2006;56:300–3. [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama H, Mizowaki T, Narita Y, Kawada N, Takahashi K, Mihara K, Hiraoka M. Development of a three-dimensionally movable phantom system for dosimetric verifcations. Med Phys. 2008;35:1643–50. doi: 10.1118/1.2897971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelms B, Ehler E, Bragg H, Tome W. Quality assurance device for four-dimensional IMRT or SBRT and respiratory gating using patient-specific intrafraction motion kernels. J App Clin Med Phys. 2007;8:152–68. doi: 10.1120/jacmp.v8i4.2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nioutsikou E, Richard NS-TJ, Bedford JL, Webb S. Quantifying the effect of respiratory motion on lung tumour dosimetry with the aid of a breathing phantom with deforming lungs. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51:3359–74. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/14/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niroomand-Rad A, Blackwell CR, Coursey BM, Gall KP, Galvin JM, McLaughlin WL, Meigooni AS, Nath R, Rodgers JE, Soares CG. Radiochromic film dosimetry: recommendations of AAPM Radiation Therapy Committee Task Group 55. American Association of Physicists in Medicine. Med Phys. 1998;25:2093–115. doi: 10.1118/1.598407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham M, Guo P, Gluckman G, Adamovics J. IMRT verification using a radiochromic/optical-CT dosimetry system. J Phys. 2006;56:221–4. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/56/1/033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham M, Sakhalkar H, Guo P, Adamovics J. An investigation of the accuracy of an IMRT dose distribution using two- and three-dimensional dosimetry techniques. Med Phys. 2008;35:2072–80. doi: 10.1118/1.2899995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paelinck L, De Neve W, De Wagter C. Precautions and strategies in using a commercial flatbed scanner for radiochromic film dosimetry. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:231–42. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/1/015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran P, Mahata A, Babu ES. Phantom for moving organ dosimetry with gel. J Phys: Conf Ser. 2009;164:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Rietzel E, Pan T, Chen GT. Four-dimensional computed tomography: image formation and clinical protocol. Med Phys. 2005;32:874–89. doi: 10.1118/1.1869852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakhalkar H, Adamovics J, Ibbott GS, Oldham M. A comprehensive evaluation of the PRESAGE/optical-CT 3D dosimetry system. Med Phys. 2009a;36:71–82. doi: 10.1118/1.3005609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakhalkar H, Sterling D, Adamovics J, Ibbott G, Oldham M. Investigation of the feasibility of relative 3D dosimetry in the Radiologic Physics Center Head and Neck IMRT phantom using presage/optical-CT. Med Phys. 2009b;36:3371–7. doi: 10.1118/1.3148534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakhalkar HS, Oldham M. Fast, high-resolution 3D dosimetry utilizing a novel optical-CT scanner incorporating tertiary telecentric collimation. Med Phys. 2008;35:101–11. doi: 10.1118/1.2804616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saw CB, Brandner E, Selvaraj R, Chen H, Saiful Huq M, Heron DE. A review on the clinical implementation of respiratory-gated therapy. Biomed Imaging Interv J. 2007;3:1–8. doi: 10.2349/biij.3.1.e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirato H, et al. Four-dimensional treatment planning and fluoroscopic real-time tumor tracking radiotherapy for moving tumor. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48:435–42. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]