Abstract

Compulsive hoarding, the acquisition of and failure to discard large numbers of possessions, is associated with substantial health risk, impairment in functioning, and economic burden. Despite clear indications that hoarding has a detrimental effect on people living with or near someone with a hoarding problem, no empirical research has examined these harmful effects. The aim of the present study was to examine the burden of hoarding on family members. Six hundred sixty-five family informants who reported having a family member or friend with hoarding behaviors completed an internet-based survey. Living with an individual who hoards during childhood was associated with elevated reports of childhood distress and family strain. Family members reported high levels of patient rejection attitudes, suggesting high levels of family frustration and hostility. Rejecting attitudes were associated both with severity of hoarding symptoms and with the individual’s perceived lack of insight into the behavior. These results suggest that compulsive hoarding adversely impacts not only the hoarding individual, but also those living with them.

Keywords: Hoarding, family, obsessive-compulsive disorder, saving, family attitudes, patient rejection

1. Introduction

Compulsive hoarding is characterized by (a) the acquisition of, and failure to discard, a large number of possessions; (b) clutter that precludes activities for which living spaces were designed; and (c) significant distress or impairment in functioning caused by the hoarding (Frost & Hartl, 1996). Hoarding has frequently been considered a subtype of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). However, studies have indicated that hoarding symptoms are distinct from more “traditional” OCD symptoms such as washing, checking, etc. (Calamari et al., 2004), and that hoarding might not be associated with a particularly high rate of OCD compared to other anxiety and mood disorders (Frost, Steketee, Tolin, & Brown, 2006; Meunier, Tolin, Frost, Steketee, & Brady, 2006; Wu & Watson, 2005). Compared to most variants of OCD, compulsive hoarding is associated with a particularly chronic course (Pinto et al., 2007) and poor prognosis for standard OCD treatments using medication and exposure with response prevention (Abramowitz, Franklin, Schwartz, & Furr, 2003; Mataix-Cols, Marks, Greist, Kobak, & Baer, 2002; Steketee & Frost, 2003), suggesting that compulsive hoarding and OCD may involve different biological, cognitive, or behavioral mechanisms.

An additional difference between OCD and hoarding is the degree of awareness and insight exhibited by individuals with these conditions. Although OCD patients display a range of insight into the irrational nature of their obsessions and compulsions, most exhibit at least some insight (Foa et al., 1995). By contrast, individuals with compulsive hoarding problems commonly display a striking lack of awareness of the severity of their behavior, often resisting intervention attempts and defensively rationalizing their acquiring and saving (Greenberg, 1987; Steketee & Frost, 2003). In a large sample of family members of individuals with reported hoarding problems, more than half (53%) described the person who hoards as either having “poor insight” or “lacks insight/delusional” (Fitch, Tolin, Frost, & Steketee, 2007). Similarly, a survey of social service workers with elderly hoarding clients revealed that the majority (73%) described their client as having severely impaired insight (Steketee, Frost, & Kim, 2001). A recent study of children and adolescents with OCD revealed that those with hoarding symptoms were rated as having worse insight than were those with other OCD symptoms (Storch et al., 2007).

A growing body of evidence points to the substantial social burden imposed by hoarding. A survey of health department officials indicated that hoarding was judged to pose a substantial health risk and in 6% of reported cases, hoarding was thought to contribute directly to the individual’s death in a house fire. One small town health department spent most of their budget ($16,000) clearing out one house, only to face the same problem 18 months later (Frost, Steketee, & Williams, 2000). Several cities in North America have developed inter-agency task forces to help them deal with individuals who hoard (Frost & Steketee, 2003). A large sample of individuals with self-identified compulsive hoarding reported a mean 7.0 psychiatric work impairment days per month (Tolin, Frost, Steketee, Gray, & Fitch, 2007), equivalent to that reported by National Comorbidity Survey (Kessler et al., 1994) participants with bipolar and psychotic disorders, and significantly greater than that reported by participants with all other anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders. Eight percent reported that they had been evicted or threatened with eviction due to hoarding, and 0.1% reported having had a child or elder removed from the home (Tolin, Frost, Steketee et al., 2007).

In addition to the ill-effects of hoarding on the individual, public health officers in the Frost et al. (2000) study rated hoarding as a serious threat to the people living with or near the sufferer. Frost and Gross (1993) reported that two-thirds of their hoarding participants stated their hoarding constituted a problem for family members. Furthermore, a number of studies have found lower rates of marriage and higher rates of divorce among hoarding participants (Steketee & Frost, 2003), suggesting problems in domestic relationships. To date, however, there has been no investigation of the burden of hoarding on family or friends. The focus of the present study is the impact of hoarding on family members and friends. Anecdotally, the present authors receive inquiries from frustrated family members approximately twice as often as they do from individuals with compulsive hoarding problems. Within samples of OCD patients, family members frequently report accommodating the individual’s obsessive fears or compulsive behaviors, leading to increased family distress and frustration toward the individual (Amir, Freshman, & Foa, 2000; Calvocoressi et al., 1995). The majority of family members report that the individual’s OCD symptoms cause disruptions in their personal lives, including social, marital, and recreational impairment (Cooper, 1996).

We sampled a large number of family members and friends of individuals reported to have compulsive hoarding problems, with the prediction that these individuals (particularly those whose loved ones meet strict criteria for hoarding) would report high levels of distress, family impairment, and patient rejection. To obtain a large sample, data were collected over the internet. The internet is increasingly being used for mental health research (Skitka & Sargis, 2006), and several studies indicate that web-based data collection results in greater sample diversity, generalizes across presentation formats, and findings are consistent with data collected using more traditional means (see Gosling, Vazire, Srivastava, & John, 2004, for a review). Equivalence of internet and paper-and-pencil measurement has been established in clinical disorders, including anxiety (Carlbring et al., 2007) and OCD (Coles, Cook, & Blake, 2007); in these studies, participants completed the same measures in paper-and-pencil and internet formats, and results did not differ. It was predicted that living with an individual who hoards during childhood would be associated with high levels of childhood distress and family discord, and that these findings would be particularly pronounced among individuals who lived in a cluttered environment during early childhood. Arguments about hoarding were predicted to be common, particularly among spouses. We further predicted that relatives of hoarders would endorse high levels of patient rejection attitudes, and that degree of patient rejection would be associated with hoarding severity, living in a cluttered environment during early childhood, and the hoarder’s level of insight.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

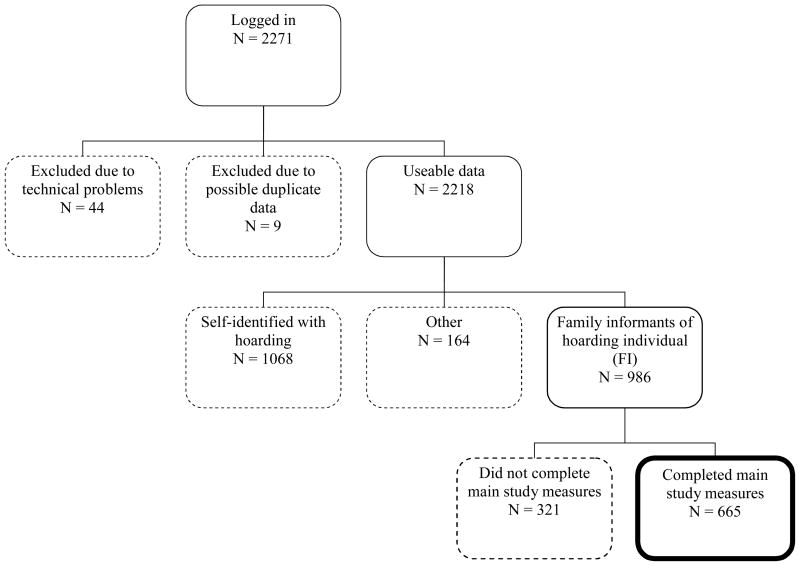

The present sample was recruited from a database of over 8,000 individuals who contacted the researchers over the past 3 years for information about compulsive hoarding after several national media appearances. Potential participants were sent an e-mail invitation to participate in the study, and were also allowed to forward the invitation to others with similar concerns. Data collection occurred from November 14, 2006 to January 15, 2007. Consistent with current recommendations (Kraut et al., 2004), prior to analysis the data were checked for apparent duplicates (i.e., a participant completing the survey more than once). Because clearly identifying data (e.g., participant names) were not collected, checking for duplicates consisted of comparing entries with identical demographic data, to see whether item responses were largely similar. Agreement between the first and fourth authors was required to exclude an apparent duplicate. A flowchart of participation is shown in Figure 1. Out of 2271 respondents, we selected 665 adults age 18 and older who identified themselves as non-hoarding friends or family members of individuals with hoarding problems.1 These participants will be labeled family informants. The individuals they described with hoarding problems will be referred to as hoarding family members. It should be noted that hoarding family members were not assessed directly in the present study; rather, information about these individuals was obtained from the family informants.

Figure 1. Flow Chart of Participation.

Note: exclusions are indicated by dashed lines. Final sample is indicated by bold line.

2.2. Materials

Diagnosis and severity of compulsive hoarding for hoarding family members was determined using a self-report version of the Hoarding Rating Scale-Interview (HRS-I; Tolin, Frost, & Steketee, 2007), which was termed the Hoarding Rating Scale-Self-Report (HRS-SR). Like the interview, the HRS-SR consists of 5 Likert-type ratings from 0 (none) to 8 (extreme) of clutter, difficulty discarding, excessive acquisition, distress, and impairment. The HRS-I has shown high internal consistency and inter-rater reliability, correlated strongly with other measures of hoarding, and reliably discriminated hoarding from non-hoarding participants (Tolin, Frost, & Steketee, 2007). The HRS-SR shows strong correlations with the HRS-I (range r = .74–.92), and shows 73% agreement of diagnostic status between self- and interviewer-report (Tolin, Frost, Steketee et al., 2007). Hoarding family members were considered to meet diagnostic hoarding criteria if the family informant described moderate (4) or greater clutter and difficulty discarding, as well as either moderate (4) or greater distress or impairment caused by hoarding. Severity of hoarding on the HRS-SR was determined by calculating the mean of all 5 items, with 0 = no hoarding symptoms, 2 = mild hoarding, 4 = moderate, 6 = severe, and 8 = extreme hoarding. Internal consistency was high in the present sample (α = .83).

Family frustration was assessed using the Patient Rejection Scale (PRS; Kreisman, Simmens, & Joy, 1979). This 11-item measure assesses rejecting or hostile attitudes toward the individual (e.g., “I don’t expect much from him/her anymore;” “I wish he/she had never been born”). Items are rated from 1 (never) to 3 (often), with 5 reverse-scored items. Scores on the PRS can range from 11–33. The PRS shows high internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Kreisman et al., 1979), and has been demonstrated to be elevated in family members of patients with schizophrenia (Bailer, Rist, Brauer, & Rey, 1994; Heresco-Levy, Brom, & Greenberg, 1992; Kreisman et al., 1979) and OCD (Amir et al., 2000). Negative family attitudes on the PRS have been shown to predict relapse and rehospitalization in patients with schizophrenia (Bailer et al., 1994; Heresco-Levy et al., 1992). To minimize confusion for the PRS and other scales, we first asked family informants for the hoarding family member’s first name or nickname, then inserted the name provided into the measure (e.g., the item “I wish he/she had never been born” was amended to “I wish [name] had never been born”). Internal consistency was high in the present sample (α = .82).

Demographic information was collected regarding the age, sex, and race/ethnicity of the family informant, age of the hoarding family member and the relationship between them. We also inquired about whether the family informant had lived with the hoarding family member, and, if so, the age of the family informant at the time.

Distress Ratings required participants to rate, from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much), the following questions: “How happy was your childhood” “To what extent was it difficult for you to make friends when you were a child?” “How frequently did you have people over to your house (friends, relatives, etc.)?” “How frequently did you argue with your parents?” “How strained was your relationship with your parents?” “How embarrassed were you about your home?” “How frequently did you argue with [name] about his/her hoarding behavior when you were living there?”

Clutter Ratings requested family informants to rate, for each decade of their life up to age 70, the extent of clutter in the hoarding family member’s home from 0 (none) to 8 (extreme) and whether they were living with the hoarding family member. We also administered the Clutter Image Rating (CIR; Frost, Steketee, Tolin, & Renaud, in press; available in Steketee & Frost, 2007), a series of 9 photographs each of a kitchen, living room, and bedroom with varying levels of clutter. Family informants select the photograph that most closely resembles each of the three rooms in the hoarding family member’s home. Scores for each room are scaled from 1 to 9, and a mean composite score is calculated across the three rooms (range 1–9). In the original study, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and inter-rater reliability for the CIR were high, as were correlations with validated hoarding measures (Frost et al., in press). Internal consistency was high in the present sample (α = .85).

Insight was assessed using an adaptation of item 11 from the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS; Goodman et al., 1989). Originally designed for clinician interviewers, the Y-BOCS has shown good psychometric properties as a self-report instrument (Steketee, Frost, & Bogart, 1996). In response to the question, “We would like to know just how clearly [name] recognizes the problem he/she has with hoarding. Please select the description below that most closely matches [name]’s level of insight into his/her problem.” Family informants rated the hoarding family member’s level of insight as:

-

(0)

Excellent insight, fully rational. [Name]’s hoarding behaviors may be bad, but [name] fully recognizes that they are a problem.

-

(1)

Good insight. [Name] readily acknowledges that his/her acquisition, clutter and/or difficulty discarding is a problem. However, when at home or out shopping/acquiring, [name] has difficulty seeing the problem with acquiring or not discarding items.

-

(2)

Fair insight. [Name] may admit clutter is a problem, but only reluctantly admits that his/her behavior (such as acquiring too many things, or failing to discard things) has caused the problem. When at home or out shopping/acquiring, [name] has difficulty seeing that he/she has a problem with acquiring or not discarding things.

-

(3)

Poor insight. [Name] maintains that acquisition, difficulty discarding, and clutter are under control or not a problem. When someone discusses the problem with him/her, [name] acknowledges that he/she might have a problem, but still underestimates the severity of the problem.

-

(4)

Lacks insight, delusional. [Name] is convinced that he/she has no problems with acquisition, clutter or difficulty discarding at all. He/she will argue that there is no problem, despite contrary evidence or arguments.

Previous analyses from the present sample indicated that insight ratings on Y-BOCS item 11 correlate significantly with discrepancy of perceived opinion about various aspects of hoarding between family informants and their hoarding family members (Fitch et al., 2007).

2.3. Procedure

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Hartford Hospital, Smith College, and Boston University. Human subjects protection was consistent with current recommendations for web-based studies (Kraut et al., 2004). Prior to data collection, participants read an informed consent page and indicated consent by clicking an icon on the page. No protected health information was collected, and it was not possible to link study data to an individual or computer. As incentive, participants were given an email address to enroll in a raffle to receive one of 10 copies of a self-help book on compulsive hoarding. Participants responded to the survey by computer. They were allowed to skip any questions they wished, or to complete only portions of the survey. Data were stored on a password-protected server. A summary of aggregate research results was emailed to all individuals in the original database.

2.4. Data Analysis

Due to the exploratory nature of the present study, corrections for multiple comparisons were not performed. The relationship between hoarding severity and family distress was examined by (a) comparing family informants (with a sub-analysis of only children of hoarding family members) who did and did not live with the hoarding family member prior to age 21 and also prior to age 10; (b) comparing children vs. siblings of hoarding family members who lived with the hoarding family member prior to age 21; (c) calculating Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between childhood distress ratings and ratings of clutter in the home; and (d) comparing frequency of arguments across different relationship types (spouse/partner, child, etc.) using a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with Tukey HSD follow-up tests. Patient rejection was examined by (a) comparing PRS scores across different relationship types using a one-way ANOVA and Tukey HSD follow-up tests; and (b) comparing PRS scores in the present sample with those in previous studies (when means and standard deviations were available) using independent-samples t-tests. Finally, we examined predictors of patient rejection by (a) calculating Pearson’s correlations between PRS scores and HRS-SR scores; CIR scores; insight scores; and age of the family informant and hoarding family member; comparing PRS scores between children of hoarding family members who did vs. did not live in a cluttered environment prior to age 10 with an independent-samples t-test; and using multiple regression analysis, predicting PRS scores, in which hoarding severity, insight, and level of home clutter prior to age 10 (dummy-coded as 0 = less than moderate or 1 = moderate or greater) were entered in successive blocks.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

Descriptive information about the family informant sample, as well as the hoarding family members they described, is found in Table 1. Of the 665 participants who completed the HRS-SR about the hoarding family member, 85.9% (n = 571) described a hoarding family member who appeared to meet full criteria for compulsive hoarding. Not surprisingly, HRS-SR and CIR scores for those meeting full criteria were significantly higher (denoting severe hoarding) than were scores for those not meeting full criteria. Nonetheless, the family members not meeting full criteria were described as having moderate severity of hoarding. Family informants were primarily White women in their mid-40s to mid-50s who described hoarding family members around 60 years old on average. Of the hoarding family members, 21.3% (n = 141) hoarding family members were reported to be spouses or partners; 46.9% (n = 311) were parents; 3.0% (n = 20) were children; 0.9% (n = 6) were grandparents; 12.4% (n = 82) were siblings; 5.4% (n = 36) were friends; and 10.1% (n = 67) had some other relationship (2 family informants did not provide this information). The majority (96.0%, n = 623) reported that the hoarding family member was still living (16 did not provide this information).

Table 1.

Sample Description: Family Informants Reporting on Hoarding Family Members

| Hoarding family member Meeting Full Criteria for Compulsive Hoarding | Hoarding family member Not Meeting Full Criteria for Compulsive Hoarding | FET | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 571 | 94 | ||

| Family informant Female (%) | 468 (83.7%) | 75 (80.6%) | .455 | |

| Family informant White (%) | 498 (94.0%) | 82 (95.3%) | .805 | |

| Family informant Age [M (SD)] | 45.36 (12.46) | 53.23 (12.76) | 5.56** | |

| Family informant HRS-SR [M (SD)] | 1.69 (1.76) | 1.87 (1.67) | 0.87 | |

| Hoarding family member Age [M (SD)] | 60.97 (12.37) | 58.45 (14.54) | 1.95 | |

| Hoarding family member HRS-SR [M (SD)] | 6.72 (0.95) | 4.18 (1.15) | 23.26** | |

| Hoarding family member CIR [M (SD)] | 5.38 (1.73) | 4.18 (1.94) | 6.06** | |

Note: HRS-SR = Hoarding Rating Scale-Self-Report. CIR = Clutter Image Rating. FET = Fisher’s Exact Test.

p < .001.

3.2. Hoarding Severity and Family Distress

Of the 662 family informants who provided information about years lived with the hoarding family member, 402 (60.7%) indicated that they had lived with the hoarding family member prior to age 21. As shown in Table 2 (top), family informants who lived with the hoarding family member before age 21 reported significantly greater childhood distress than did those who did not: they rated their childhoods as less happy, had people over less often, argued with parents more, described their relationship with their parents as more strained, and were more embarrassed about the condition of the home. For family informants who lived with the hoarding family member during childhood, we compared children to siblings. On all measures of family distress, children of hoarding family members reported more severe distress than did siblings (Table 2, bottom). Female family informants reported significantly more strained relationships with parents than did male family informants [M (SD) = 1.78 (1.25) vs. 1.46 (1.17), t650 = 2.45, p = .015]; no other distress measures differed by gender.

Table 2.

Childhood Distress Ratings (0–4) for Family Informants Who Lived With and Did Not Live With the Hoarding Family Member Prior to Age 21 (Top) and Distress Ratings for Children vs. Siblings of Hoarding Family Members (Bottom)

| Lived with hoarding family member prior to age 21 | Did not live with hoarding family member prior to age 21 | t | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Happy childhood | 2.42 (0.99) | 2.83 (0.95) | 5.26** |

| Difficult to make friends | 1.58 (1.22) | 1.42 (1.22) | 1.62 |

| Have people over to house | 1.78 (1.22) | 2.50 (1.14) | 7.70** |

| Argue with parents | 2.00 (1.13) | 1.46 (1.01) | 6.22** |

| Strained relationship with parents | 1.95 (1.20) | 1.38 (1.21) | 5.97** |

| Embarrassed about home | 2.23 (1.57) | 0.95 (1.27) | 11.01** |

| Children of hoarding family members | Siblings of hoarding family members | t | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Happy childhood | 2.39 (0.98) | 2.65 (1.06) | 2.06* |

| Difficult to make friends | 1.69 (1.24) | 1.18 (1.16) | 3.34** |

| Have people over to house | 1.59 (1.16) | 2.23 (1.16) | 4.42** |

| Argue with parents | 2.09 (1.12) | 1.63 (1.05) | 3.31** |

| Strained relationship with parents | 2.04 (1.18) | 1.54 (1.28) | 3.27** |

| Embarrassed about home | 2.64 (1.42) | 1.00 (1.25) | 9.38** |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Two hundred sixty five children of hoarding family members (who met full criteria for hoarding) reported living with the hoarding family member during childhood (including prior to age 10) and completed ratings of childhood distress. Of these, 101 (38%) rated the clutter as moderate (4) or greater prior to age 10 and 164 (62%) rated the clutter as less than moderate. As shown in Table 3, children of hoarding family members who lived in moderate or greater clutter before age 10 reported significantly more distress than did those who lived in less clutter prior to age 10: they rated their childhoods as less happy, reported more difficulty making friends, had people over less often, argued with parents more, described their relationship with their parents as more strained, and were more embarrassed about the condition of the home. No differences in current hoarding severity on the HRS-SR were noted between these two groups (all ps > .05).

Table 3.

Childhood Distress Ratings of Children of Hoarding Family Members Who Did and Did Not Live in a Cluttered Home Prior to Age 10.

| Moderate or greater clutter prior to age 10 | Less than moderate clutter prior to age 10 | t | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Happy childhood | 1.99 (0.91) | 2.59 (0.94) | 5.07** |

| Difficult to make friends | 2.05 (1.25) | 1.44 (1.15) | 4.05** |

| Have people over to house | 1.03 (0.91) | 1.94 (1.17) | 6.66** |

| Argue with parents | 2.40 (1.18) | 1.94 (1.07) | 3.26** |

| Strained relationship with parents | 2.42 (1.16) | 1.82 (1.13) | 4.111** |

| Embarrassed about home | 3.43 (0.95) | 2.24 (1.47) | 7.20** |

p < .001.

For family informants who lived with the hoarding family member prior to age 21, childhood distress ratings were correlated with reported severity of clutter (0–8) at age 0–10 and age 11–20. In all cases, the correlations were significant (r’s ranged from .27–.57, p < .001), suggesting that more severe clutter was related to greater distress. The strongest correlation (r = .57) was between clutter severity between ages 11–20 and embarrassment about the condition of the home. When we separated children from siblings of hoarding family members, significant correlations were found between childhood distress ratings and severity of clutter for children of hoarding family members (r’s ranged from .25–.64), with the highest correlation again being between clutter severity during ages 11–20 and embarrassment about the condition of the home. For siblings of hoarding family members, correlations were generally lower (r’s ranged from .00–.35); the only significant correlations were between clutter severity during ages 0–10 and arguments with parents (r = .33) and embarrassment about the condition of the home (r = .35).

Participants indicated the frequency with which they presently argued with the hoarding family member about clutter or hoarding-related behaviors. Two hundred eighty-seven (70.7%) responded “somewhat” or more frequently, and 87 (21.4%) responded that they argued “very much.” Scores on this measure did not differ significantly whether the hoarding family member met full criteria for hoarding (M = 2.24, SD = 1.30) or did not (M = 2.06, SD = 1.33), t397 = 0.88, p = .378. There was a significant difference in frequency of arguments across family informant/hoarding family member relationships (limited to spouse/partner, parent, sibling, and friend due to the low n in other groups), F3, 562 = 19.80, p < .001. Spouses/partners of hoarding family members reported more frequent arguments about hoarding (M = 2.80, SD = 1.11) than did any other group. Children of hoarding family members reported more frequent arguments (M = 2.23, SD = 1.31) than did siblings (M = 1.79, SD = 1.29) or friends (M = 1.25, SD = 1.40); the latter two groups did not differ from each other.

3.3. Patient Rejection

The average score on the 11-item PRS for the entire sample was 20.48 (SD = 4.57). PRS scores did not differ significantly whether the hoarding family member met full criteria for hoarding, t385 = 0.27, p = .784. There were no significant differences in PRS scores across spouse/partners, children, siblings, or friends of hoarding family members (F3, 545 = 2.04, p = .107). Male and female family informants did not differ in terms of PRS scores (t623 = 1.57, p = 117).

Table 4 compares the PRS scores in the present sample with those of prior studies using the same measure. Family informants reported more rejecting attitudes than did family members of treatment-seeking OCD patients, and showed levels comparable to family members of patients hospitalized for schizophrenia.

Table 4.

Patient Rejection Scale Scores among Family Members of Hoarding Individuals, Compared to Other Patient Groups

| Comparison group | M (SD) | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoarding (M = 20.48, SD = 4.57) | Schizophrenia, at hospital discharge (Kreisman et al., 1979) | 16.5 (3.8) | 9.41 | < .001 |

| Schizophrenia, at hospital intake (Bailer et al., 1994) | 15.8 (SD not reported) | |||

| Schizophrenia, outpatient (Heresco-Levy et al., 1992) | 19.4 (5.5) | 1.58 | 0.11 | |

| Schizophrenia, chronic inpatient, rated by staff (Heresco-Levy, Ermilov, Giltsinsky, Lichtenstein, & Blander, 1999) | 21.3 (1.8) | 1.01 | 0.31 | |

| OCD, outpatient (Amir et al., 2000) | 16.81 (3.84) | 6.65 | <.001 | |

PRS scores correlated significantly with hoarding family member HRS-SR scores (r = .148, p = .003), CIR scores (r = .120, p = .018), and insight scores (r = .339, p < .001). They did not correlate significantly with age of the hoarding family member (r = −.047, p = .367) or age of the family informant (r = −.046, p = .374).

Examining only children of hoarding family members who completed the PRS, family informants who reported moderate or greater clutter in the home prior to age 10 (n = 99) showed significantly greater patient rejection than did family informants who reported less than moderate clutter in the home before age 10 (n = 162), t259 = 2.75, p = .007. PRS means (SDs) were 21.62 (4.49) for the former group and 19.98 (4.77) for the latter.

As shown in Table 5, hoarding severity (HRS-SR total score) significantly predicted PRS scores in a regression equation. When insight (Y-BOCS item 11) was added, the overall variance accounted for increased significantly, suggesting that the perceived level of insight predicts patient rejection beyond the effect of hoarding severity. Adding level of home clutter before age 10 further increased the variance accounted for, demonstrating that living in a cluttered environment in early childhood is a unique predictor of patient rejection.

Table 5.

Predicting Patient Rejection Scale Scores from Hoarding Severity and Insight

| Block | β | t | R2 | SE | F | R2 change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | .044 | 4.55 | 11.90** | |||

| HRS-SR | .210 | 3.45** | ||||

| 2 | .172 | 4.24 | 26.76** | .128** | ||

| HRS-SR | .191 | 3.37** | ||||

| Insight | .359 | 6.31** | ||||

| 3 | .196 | 4.19 | 20.83** | .024* | ||

| HRS-SR | .185 | 3.29** | ||||

| Insight | .347 | 6.16** | ||||

| Moderate or greater clutter prior to age 10 | .155 | 2.76* | ||||

Note: HRS-SR = Hoarding Rating Scale-Self Report.

p < .01.

p < .001.

4. Discussion

The present study is the first of which we are aware to examine the burden of compulsive hoarding on family members. Living in a severely cluttered environment during early childhood (regardless of whether formal diagnostic criteria are met) is associated with elevated rates of childhood distress, including less happiness, more difficulty making friends, reduced social contact in the home, increased intra-familial strain, and embarrassment about the condition of the home. Whether living in a cluttered environment during childhood is a vulnerability factor for developing later psychopathology is an empirical question that requires additional study.

Perhaps the most striking finding from the present results is the high degree of patient rejection attitudes among family members. Scores on the PRS substantially exceeded those obtained from family members of OCD patients (Amir et al., 2000), and equaled or exceeded those from family members of patients with schizophrenia (Bailer et al., 1994; Heresco-Levy et al., 1992; Kreisman et al., 1979). Patient rejection was associated with severity of hoarding, the perceived level of insight displayed by the hoarding family member, and severity of clutter in the home during early childhood: individuals with more severe hoarding behaviors, those perceived as having less insight, and whose homes were severely cluttered during the family informant’s early childhood, are subject to more negative attitudes from family. Expressed emotion, defined as critical, hostile, or emotionally overinvolved patterns of interaction between family members and the patient, appear to predict poor initial response to OCD treatment, or relapse following successful treatment (Chambless & Steketee, 1999; Leonard et al., 1993). Clinicians working with compulsive hoarding may find it advantageous to work with the family by providing education about the harmful effects of such negative attitudes (e.g., by using cognitive strategies to reframe the patient’s behavior as manifestations of an illness rather than as a personality flaw or malicious behavior) and improving coping strategies among family members (Van Noppen & Steketee, 2003).

An important limitation of the present study is the method of participant recruitment. As described previously, recruitment began with emailing individuals who had contacted the investigators in the prior 3 years for information about compulsive hoarding; we also permitted individuals to forward the invitation to other interested parties. This method of recruitment may have biased in favor of family members of individuals with more severe hoarding behaviors or with poorer insight. Such family members might be more motivated to seek information about hoarding and to contact others for discussion (including joining internet bulletin boards on the topic). Additional research on the families of treatment-seeking hoarding patients would help clarify this issue.

Another limitation of the present study is the absence of other indices of family burden, including lost time and wages, health care costs absorbed by family members, the health care requirements of family members (e.g., counseling) due to the family member’s hoarding behavior, and the costs of excessive acquisition of objects by the individual who hoards. The present data suggest that overall the burden on family members is quite high, and additional research is needed to determine the full range of this burden.

Finally, it is noted that asking participants to describe their physical and interpersonal living situations retrospectively (often 30–40 years after the fact) invites errors such as memory decay and mood-congruent retrieval bias. Additional research is needed that will examine the level of distress among children living in cluttered environments.

The present data add to a growing body of evidence suggesting that hoarding is uniquely associated with severe dysfunction, including work and role impairment (Tolin, Frost, Steketee et al., 2007), burden on social service agencies (Frost et al., 2000), and high rates of psychiatric comorbidity (Frost et al., 2006) that exceed those of OCD patients (Samuels et al., 2006; Samuels et al., 2002). Compulsive hoarding appears to exert a profound adverse influence not only on individuals who hoard, but also on those living with them.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute of Mental Health grants R01 MH074934 (Tolin), R01 MH068008 and MH068007 (Frost & Steketee), and R21 MH068539 (Steketee). Oxford University Press supplied copies of a book to be used in a raffle for participants. Results of this study have been submitted for presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, November 2007, Philadelphia. The authors thank Dr. Nicholas Maltby for his technical assistance.

Footnotes

Although all participants described themselves as non-hoarding relatives of a hoarding family member, analysis of the 480 participants who completed the Hoarding Rating Scale-Self Report (HRS-SR) in reference to themselves indicated that 49 (10.2%) in fact met our research criteria for compulsive hoarding. These participants were included in the analyses.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abramowitz JS, Franklin ME, Schwartz SA, Furr JM. Symptom presentation and outcome of cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:1049–1057. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir N, Freshman M, Foa EB. Family distress and involvement in relatives of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2000;14:209–217. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(99)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailer J, Rist F, Brauer W, Rey ER. Patient Rejection Scale: correlations with symptoms, social disability and number of rehospitalizations. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1994;244:45–48. doi: 10.1007/BF02279811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calamari JE, Wiegartz PS, Riemann BC, Cohen RJ, Greer A, Jacobi DM, Jahn SC, Carmin C. Obsessive-compulsive disorder subtypes: an attempted replication and extension of a symptom-based taxonomy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:647–670. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvocoressi L, Lewis B, Harris M, Trufan SJ, Goodman WK, McDougle CJ, Price LH. Family accommodation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:441–443. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlbring P, Brunt S, Bohman S, Austin D, Richards J, Ost LG, Andersson G. Internet vs. paper and pencil administration of questionnaires commonly used in panic/agoraphobia research. Computers in Human Behavior. 2007;23:1421–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Steketee G. Expressed emotion and behavior therapy outcome: A prospective study with obsessive compulsive and agoraphobic outpatients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:658–665. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles ME, Cook LM, Blake TR. Assessing obsessive compulsive symptoms and cognitions on the internet: Evidence for the comparability of paper and Internet administration. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2232–2240. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: effects on family members. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:296–304. doi: 10.1037/h0080180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch KE, Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. Compulsive hoarding: Assessing insight. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Philadelphia. 2007. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Kozak MJ, Goodman WK, Hollander E, Jenike MA, Rasmussen SA. DSM-IV field trial: obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:90–96. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Gross R. The hoarding of possessions. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1993;31:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90094-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Hartl TL. A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:341–350. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G. Community response to hoarding problems. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Obsessive-Compulsive Foundation; Nashville, TN. 2003. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Tolin DF, Brown TA. Comorbidity and diagnostic issues in compulsive hoarding. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Anxiety Disorders Association of America; Miami, Florida. 2006. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Tolin DF, Renaud S. Development and validation of the Clutter Image Rating. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Williams L. Hoarding: a community health problem. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2000;8:229–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2000.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, Heninger GR, Charney DS. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, Vazire S, Srivastava S, John OP. Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about internet questionnaires. American Psychologist. 2004;59:93–104. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D. Compulsive hoarding. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1987;41:409–416. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1987.41.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heresco-Levy U, Brom D, Greenberg D. The Patient Rejection Scale in an Israeli sample: correlations with relapse and physician’s assessment. Schizophrenia Research. 1992;8:81–87. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(92)90064-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heresco-Levy U, Ermilov M, Giltsinsky B, Lichtenstein M, Blander D. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia and staff rejection. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:457–465. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut R, Olson J, Banaji M, Bruckman A, Cohen J, Couper M. Psychological research online: report of Board of Scientific Affairs’ Advisory Group on the Conduct of Research on the Internet. American Psychologist. 2004;59:105–117. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreisman DE, Simmens SJ, Joy VD. Rejecting the patient: preliminary validation of a self-report scale. Schizophr Bull. 1979;5:220–222. doi: 10.1093/schbul/5.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard HL, Swedo SE, Lenane MC, Rettew DC, Hamburger SD, Bartko JJ, Rapoport JL. A 2- to 7-year follow-up study of 54 obsessive-compulsive children and adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:429–439. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820180023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mataix-Cols D, Marks IM, Greist JH, Kobak KA, Baer L. Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions as predictors of compliance with and response to behaviour therapy: results from a controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2002;71:255–262. doi: 10.1159/000064812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier SA, Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G, Brady RE. Prevalence of hoarding symptoms across the anxiety disorders. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Anxiety Disorders Association of America; Miami, FL. 2006. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A, Eisen JL, Mancebo M, Dyck I, Edelen M, Rasmussen S. A 2-year follow-up study of the course of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Paper presented at the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Philadelphia, PA. 2007. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ, Pinto A, Fyer AJ, McCracken JT, Rauch SL, Murphy DL, Grados MA, Greenberg BD, Knowles JA, Piacentini J, Cannistraro PA, Cullen B, Riddle MA, Rasmussen SA, Pauls DL, Willour VL, Shugart YY, Liang KY, Hoehn-Saric R, Nestadt G. Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Results from the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. Behav Res Ther. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ, Riddle MA, Cullen BA, Grados MA, Liang KY, Hoehn-Saric R, Nestadt G. Hoarding in obsessive compulsive disorder: results from a case-control study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:517–528. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skitka LJ, Sargis EG. The internet as psychological laboratory. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:529–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G, Frost R, Bogart K. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: interview versus self-report. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G, Frost RO. Compulsive hoarding: Current status of the research. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:905–927. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G, Frost RO. Compulsive hoarding and acquiring: Workbook. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G, Frost RO, Kim HJ. Hoarding by elderly people. Health and Social Work. 2001;26:176–184. doi: 10.1093/hsw/26.3.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Lack CW, Merlo LJ, Geffken GR, Jacob ML, Murphy TK, Goodman WK. Clinical features of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder and hoarding symptoms. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2007;48:313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. A brief interview for assessing compulsive hoarding: The Hoarding Rating Scale-Interview. 2007. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G, Gray KD, Fitch KE. The economic and social burden of compulsive hoarding. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Philadelphia. 2007. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Van Noppen BL, Steketee G. Family responses and multifamily behavioral treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2003;3:231–247. [Google Scholar]

- Wu KD, Watson D. Hoarding and its relation to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:897–921. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]