Abstract

Research Findings

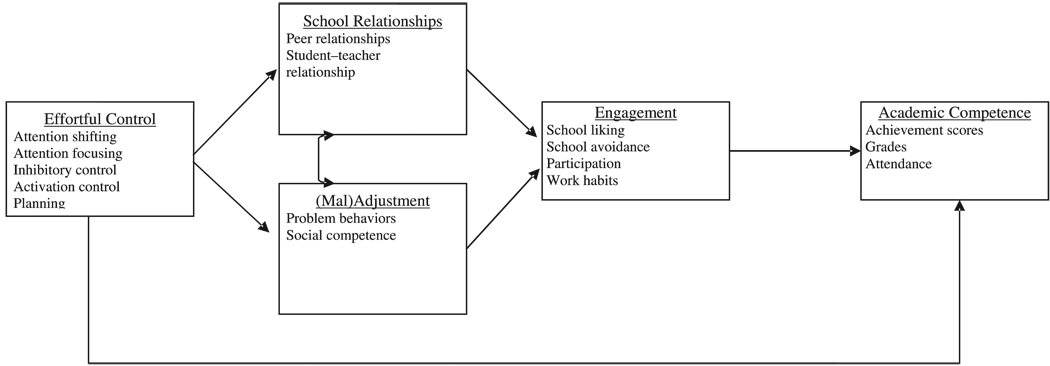

In this article, we review research on the relations of self-regulation and its dispositional substrate, effortful control, to variables involved in school success. First, we present a conceptual model in which the relation between self-regulation/effortful control and academic performance is mediated by low maladjustment and high-quality relationships with peers and teachers, as well as school engagement. Then we review research indicating that effortful control and related skills are indeed related to maladjustment, social skills, relationships with teachers and peers, school engagement, as well as academic performance.

Practice or Policy

Initial findings are consistent with the view that self-regulatory capacities involved in effortful control are associated with the aforementioned variables; only limited evidence of mediated relations is currently available.

Recently, there has been a sharp increase in research concerning the role of emotion- related self-regulatory processes in children’s school readiness and academic outcomes. Definitions of emotion-related self-regulation vary, but in general it refers to processes used to manage and change if, when, and how one experiences emotions and emotion-related motivational and physiological states and how emotions are expressed behaviorally (Eisenberg, Hofer, & Vaughan, 2007; see Table 1 for some key definitions). Emotion-related self-regulation includes regulatory processes that can be willfully controlled (although they are often in an automatic mode) when used to manage emotion-related processes. Of course, children’s emotion can also be regulated by external factors such as parents’ behaviors.

TABLE 1.

Definitions of Central Terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Temperament | “Constitutionally based individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation, in the domains of affect, activity, and attention” (Rothbart & Bates, 2006, p. 100). |

| Emotion-related self-regulation | Processes used to change one’s own emotional state, to prevent or initiate emotion responding (e.g., by selecting or changing situations), to modify the significance of the event for the self, and to modulate the behavioral expression of emotion (e.g., through verbal or nonverbal cues; Eisenberg, Hofer, et al., 2007). |

| Effortful control | The regulatory component of temperament, defined as “the efficiency of executive attention—including the ability to inhibit a dominant response and/or to activate a subdominant response, to plan, and to detect errors” (Rothbart & Bates, 2006, p. 129). |

| Activation control | A component of effortful control, defined as the capacity to perform an action when there is a strong tendency to avoid it. |

| Inhibitory control | A component of effortful control, defined as the capacity to plan and effortfully suppress inappropriate approach responses under instructions or in novel or uncertain situations. |

| Attentional control | A component of effortful control, defined as the abilities to maintain attentional focus upon task-related channels or to shift one’s focus as needed to deal with task demands. |

Individual differences in emotion-related self-regulation are at least partly due to individual differences in temperament. According to Rothbart and Bates (2006), two major components of temperament are regulation and reactivity (i.e., responsiveness to change in the external and internal environment). At the core of temperamental regulation is the construct of effortful control (EC), defined as “the efficiency of executive attention—including the ability to inhibit a dominant response and/or to activate a subdominant response, to plan, and to detect errors” (Rothbart & Bates, 2006, p. 129). EC includes the abilities to shift and focus attention as needed (i.e., attentional control); to activate and inhibit behavior as required (i.e., activational and inhibitory control, respectively), especially when one does not feel like doing so; and other executive functioning skills involved in integrating information, planning, and modulating emotion and behavior. Thus, EC includes individual differences in many processes involved in self-regulation, including the regulation of emotion, attention, and behavior. Although EC could be used in the pursuit of a maladaptive goal, in general it is expected to relate to flexible, resilient behavior (and has been found to do so; Eisenberg et al., 2004; Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Morris, 2002). In this article, we focus primarily on EC and use the term to refer to regulatory processes that likely have a dispositional basis and that are used to modulate emotion and behavior, often partly through the modulation of attention.

REGULATORY CAPACITIES AND ACADEMIC READINESS: CONCEPTUAL LINKS

A focus on using regulatory variables such as EC as predictors of children’s grades, engagement, or learning is not new. For example, two decades ago, Shoda, Mischel, and Peake (1990) demonstrated that preschoolers’ delay of gratification (which is viewed as involving EC) was predictive of their SAT scores. However, most of the relevant work has been conducted in the past decade.

A number of mechanisms have been proposed to explain the role of EC in academic success. Posner and Rothbart (2007) argued that the attentional components of EC represent central cognitive skills that are integral to key academic tasks. Students high in regulation also are believed to regulate goal-directed behavior well and to have high levels of mastery motivation and engagement, all of which are linked to academic success (Zhou et al., 2007; Zimmerman, 1998). Moreover, children high in EC tend to be quite good at developing and maintaining relationships with teachers and peers that are hypothesized to promote academic success. Students high in EC should be able to avoid angry interactions that disturb the learning environment and to minimize experiences of sadness/shyness that reduce high-quality social and emotional interactions in the classroom (Fabes, Martin, & Hanish, 1999).

We believe that school readiness is multidimensional construct based on students’ physical health, social and emotional functioning, approaches to learning, language development, and cognitive abilities (Kids Count, 2005). In this article, we focus primarily on the importance of students’ social and emotional development, especially their EC, and the many ways in which EC is relevant to the relationships students form in school as well as how they perform academically. As is depicted in Figure 1, EC would be expected to relate positively to children’s school relationships and negatively to maladjustment (Eisenberg, Sadovsky, & Spinrad, 2005). Positive relationships with teachers and peers are predicted to engender classroom engagement, resulting in higher academic performance. In addition, as is discussed in more detail later, direct relations of EC with school engagement and academic performance are predicted because children who can manage their attention, behavior, and emotions are likely to act in socially appropriate ways with teachers and peers and to maintain attention when engaged in learning and other academic tasks. In this article, we review research on the relations of EC to school performance and the potential mediators in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Heuristic model of the relations among effortful control, social relationships, (mal) adjustment, school engagement, and academic competence.

EC AND SCHOOL ACHIEVEMENT

There is now growing evidence that children’s EC is positively related to academic skills or school achievement, including measures of students’ reading, math, and linguistic abilities (Fabes, Martin, Hanish, Anders, & Madden-Derdich, 2003; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2003; Valiente, Lemery-Chalfant,& Castro, 2007). In addition, adolescents’ EC has been positively related to their achievement scores, teacher-rated academic competence, and grade point average, even when the effects of cognitive variables have been controlled (Gumora & Arsenio, 2002; Kurdek & Sinclair, 2000). Existing data support the proposition that EC is predictive of academic success in Caucasian, Hispanic, and African American samples (Hill & Craft, 2003; Valiente, Lemery-Chalfant, Swanson, & Reiser, 2008). In terms of longitudinal prediction, Blair and Razza (2007) found that preschoolers’ inhibitory control, but not attention shifting, was related to their emerging math abilities in kindergarten. Similarly, fall assessments of EC have been predictive of spring assessments of vocabulary and math (McClelland et al., 2007). The validity of the concurrent and prospective relations is supported by some, albeit limited, experimental evidence that gains in EC are related to academic success (Bierman, Nix, Greenberg, Blair, & Domitrovich, 2008; Diamond, Barnett, Thomas, & Munro, 2007).

RELATIONS OF EC WITH SOCIAL COMPETENCE, MALADJUSTMENT, AND PEER RELATIONSHIPS

The preceding review suggests that EC is often predictive of academic competence. However, as is illustrated in Figure 1, it is likely that this relation is partly due to the role of self-regulation in fostering social competence and adjustment, which in turn promote classroom engagement. For example, peer competence (e.g., peer acceptance) in the early school years has been negatively related to concurrent and subsequent deficits in work habits, deficits in math and language/reading, negative school attitudes, school avoidance, and underachievement during the first year or two of school (Ladd, 2003; O’Neil, Welsh, Parke, Wang, & Strand, 1997; Wentzel, 2009). Thus, if EC affects children’s social functioning and peer relationships, it likely also affects academic skills.

EC and Social Competence

Children high in EC, because of their ability to manage attention, emotion, and behavior, tend to behave in constructive, socially appropriate ways in social interactions (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1992; Eisenberg, Fabes, Nyman, Bernzweig, & Pinuelas, 1994). Moreover, EC, as assessed with a battery of behavioral measures, predicts preschoolers’ adult-reported social competence both concurrently (Dennis, Brotman, Huang, & Gouley, 2007; Spinrad et al., 2007) and across time (Eiden, Colder, Edwards, & Leonard, 2009). Numerous researchers have also found relations between adult-reported social competence (i.e., social competence with peers, socially skilled behavior) and EC as reported by adults or sometimes assessed with behavioral measures, concurrently and sometimes over one or more years (Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, & Reiser, 2000; Eisenberg, Vaughan, & Hofer, 2009; Fantuzzo, Perry, & McDermott, 2004; Gouley, Brotman, Huang, & Shrout, 2008; Spinrad et al., 2006; Valiente et al., 2008). Similar findings have been obtained in other cultures: Zhou, Eisenberg, Wang, and Reiser (2004) found that EC was related to peers’ ratings of sociability/leadership in China, and Eisenberg, Pidada, and Liew (2001) found relations of EC with adult-reported social competence in Indonesia.

Some researchers have assessed the relation of EC to observational measures of the quality of children’s peer interactions. For example, Fabes et al. (1999) found that, compared to children who were low in EC, children who were high in EC were relatively high in a composite of socially competent behaviors (e.g., helping others, being friendly) during peer interactions and teacher-reported socially competent behavior. Similarly, David and Murphy (2007) found that EC predicted low levels of problematic peer behaviors (i.e., observed hostility, negative affect, and provocative behavior during peer interactions combined with low teacher-rated social competence); however, EC was unrelated to quantity of peer interaction. Thus, individual differences in EC have been related to a range of measures of quality of children’s social behavior.

Effortful Control and Adjustment Problems

Adjustment problems have been classified into broadband groups called externalizing (EXT) and internalizing (INT). EXT refers to problems such as aggression or antisocial behavior, whereas INT encompasses problems such as anxiety, depression, withdrawal, and somatic complaints (Achenbach, Howell, Quay, & Conners, 1991). INT is often contrasted with EXT, but the constructs are often positively related and co-occur (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983). Self-regulation deficits (lack of attentional control) may partly explain the frequent co-occurrence of INT and EXT (Keiley, Lofthouse, Bates, Dodge, & Pettit, 2003).

Theoretically speaking, EC is related to EXT and INT. EXT children have difficulties regulating emotion, behavior, and attention. EC abilities play a role in modulating these difficulties, fostering planning, and reducing impulsive behavior. The relation between EC and INT is less straightforward. Children with INT problems appear to be overcontrolled in that their overt behavior may be inhibited or rigid. We have argued, however, that this type of overcontrol is not willful but is reactive and not voluntary (Eisenberg et al., 2004). Furthermore, INT problems involve difficulty controlling cognition and emotion, for example in rumination (e.g., Garnefski, Kraaij, & van Etten, 2005). Thus, some researchers have suggested that EC capabilities may prevent or reduce INT problems. Attentional control may facilitate moving attention from negative to neutral or positive thoughts, which should reduce negative emotion (a common feature of INT). Similarly, attentional control enables attention to be directed away from threatening stimuli, which should reduce negative arousal, assist in regulating withdrawal, and contribute to the quality of social interactions (e.g., Eisenberg, Shepard, Fabes, Murphy, & Guthrie, 1998). Aspects of EC such as planning might be expected to assist children with INT problems to avoid threatening or over-arousing settings (e.g., avoiding going to play at a popular park to avoid crowds of people and preclude experiencing social anxiety). Conversely, inhibitory control is conceptually unrelated to INT.

EXT problems

Researchers’ investigations of relations between EC and EXT vary widely in terms of quality (e.g., use of multiple reporters, inclusion of observed measures, collection of longitudinal data). Most of the studies conducted in recent years have used multiple methods and/or reporters, and many have been longitudinal in design. Some high-quality studies also minimize interpretation problems such as inflated correlations due to shared method variance (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2004; Lemery, Essex, & Smider, 2002; Lengua, West, & Sandler, 1998). The apparent overlap in the definition and measurement of EXT and EC poses difficulty in the interpretation of research in which positive relations between EC and EXT have been found. Nonetheless, researchers using measures from which confounded items have been removed also generally have found positive associations between EC and EXT, as well as between EC and INT (e.g., Lemery et al., 2002; Lengua et al., 1998).

EC or components of EC such as attentional and inhibitory control have often been negatively related with concurrent and/or later EXT problems (Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg, Sadovsky, Spinrad, et al., 2005). For instance, in an at-risk sample, Eiden, Edwards, and Leonard (2007) found that 3-year-olds’ observed self-regulation (which very likely partly reflected EC) was negatively correlated with adult-reported EXT problems at 3 years, at 4 years, and during kindergarten (cf. Dennis et al., 2007). Similar across-time relations between EC and EXT have been found with toddlers (Spinrad et al., 2007) and school-age children (Lengua, 2003). Furthermore, increases in EC over time have been related to lower levels of EXT over and above change in negative aspects of parenting (Lengua, 2006), and EC has predicted EXT across the school years, even when prior levels of EC and EXT have been taken into account (Valiente et al., 2006). Moreover, using a combined sample from Valiente et al. (2006) and another longitudinal study (see Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 1996), Zhou et al. (2007) found relations between trajectories of attentional control or persistence (believed to involve EC) and EXT. For example, children whose adult-rated attention focusing or observed persistence was high at 5 years and remained stable from 5 to 10 years of age were more likely to have low and stable parent- and teacher-rated EXT. Similar relations between EC and EXT have been found in ethnically diverse samples in the United States (Valiente, Lemery-Chalfant, & Reiser, 2007), France (Hofer, Eisenberg, & Reiser, in press), The Netherlands (Oldehinkel, Hartman, De Winter, Veenstra, & Ormel, 2004), and non-Western countries such as China (Eisenberg, Ma, et al., 2007; Eisenberg, Zhou, et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2004, 2008).

Some studies have supported the notion that EC is related to particular types of EXT. Olson, Sameroff, Kerr, Lopez, and Wellman (2005) reported that negative relations between 3-year-olds’ observed and parent-reported EC and adult-reported EXT problems were accounted for by impulsive and inattentive EXT problems rather than aggression problems. Oldehinkel et al. (2004) found that children with attention problems had lower EC than those with aggression problems. However, EC also has been negatively related to aggression (Hanish et al., 2004). Thus, EC may be related to a variety of EXT problems but have a stronger relation with particular types of EXT problems (e.g., those involving attention).

In several studies, the relation between EC and EXT or INT problems has been stronger for children prone to negative emotionality than for less negative children (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1992; Eisenberg, Guthrie, et al., 2000; Eisenberg et al., 1998, 2004; Zhou et al., 2004). Thus, EC appears to be more important for regulating adjustment problems for children who are prone to negative emotion. Researchers have hypothesized that the combination of low EC and high negative emotionality may be one of several pathways to specific EXT problems, for example, reactive aggression (see Frick & Morris, 2004).

INT problems

Findings regarding the relation of EC to INT are complex. Attentional control has been associated with low levels of INT problems (Dennis et al., 2007; Derryberry & Reed, 2002; Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; see also Oldehinkel et al., 2004; Silk, Steinberg, & Morris, 2003). However, Dennis et al. found that observed EC was negatively related to INT for 4-year-olds, but not 5-and 6-year-olds, in an at-risk sample. Dennis et al. noted that this finding was inconsistent with other studies and that future research was necessary; however, they proposed that moderation by age may have occurred because of symptoms of INT changing across time or that EC may have been particularly helpful in children’s transition to school (preschool).

Eisenberg and colleagues found that the relations of EC and INT varied with the measure of EC, the age of the child, and whether EXT problems were taken into account. When children were approximately 4.5 to 7 years of age, pure INT (i.e., INT not co-occurring with high EXT problems) was related to low adult-reported attentional EC but not inhibitory control (Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001). However, in 2-and 4-year follow-ups, pure INT was unrelated to attentional or inhibitory control (Eisenberg, Sadovsky, Spinrad, et al., 2005; Eisenberg, Valiente, et al., 2009).

These investigators obtained more relations when INT symptoms were examined regardless of co-occurring EXT symptoms. Using a continuous measure of INT and ignoring whether or not EXT symptoms co-occurred with INT, they found that personality resiliency (parents’ and teachers’ reports of children’s flexible and adaptable behavior; see Block & Block’s, 1980, construct of ego resiliency) mediated the negative relations between EC and INT (EC → resiliency → low INT problems; Eisenberg et al., 2004). Valiente et al. (2006), using the same sample and continuous measures of INT, found that EC negatively predicted teacher-reported (but not mother-reported) INT in early to mid-adolescence when controlling for earlier levels of EC and INT. Thus, the findings appear to be stronger in the United States when INT has been examined regardless of the level of EXT symptoms—that is, when children with high levels of INT can also have high levels of EXT. However, in China, even pure INT was negatively related to EC in children of about the same age as those in the U.S. study (Eisenberg, Ma, et al., 2007). What is interesting is that Eisenberg, Ma, et al. noted that there was a low degree (less than 3%) of comorbidity in their Chinese sample.

Using the U.S. sample in Eisenberg et al.’s (2001, 2005, 2009) longitudinal study, Eggum et al. (2009) found that attentional control predicted different trajectories of withdrawal (a component of INT) over time. For instance, low adult-reported attentional control was related to adult-reported withdrawal that was initially high and then declined over the next 6 years (as opposed to withdrawal that was initially low and then either declined or was stable). Furthermore, Schultz, Izard, Ackerman, and Youngstrom (2001) found that in low-income families, preschoolers’ teacher-rated attentional control was inversely related to teacher-reported social withdrawal in the first grade (see also Lengua, 2003).

The relation of inhibitory control to INT problems has not been consistent across studies. Some researchers have found negative relations between inhibitory control and INT. For example, Riggs, Blair, and Greenberg (2003) found that observed inhibitory control negatively related to first and second graders’ parent-rated, but not teacher-rated, INT 2 years later. Similarly, Chinese first and second graders with parent-reported INT problems were lower than control children in parent-rated inhibitory control (Eisenberg, Ma, et al., 2007). In contrast, Spinrad et al. (2007) found that toddlers’ inhibitory control sometimes was positively related to inhibition to novelty (an aspect of INT; discomfort or behavioral/verbal reticence in response to new situations or people). Other researchers have found that INT (pure without co-occurring EXT) and control children do not differ in inhibitory control (Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg, Sadovsky, Spinrad, et al., 2005). In contrast, K. Murray and Kochanska (2002) found a positive relation between INT problems and EC.

In summary, support for a negative relation between INT and EC is inconsistent. A negative relation between EC and INT appears to be more likely for attentional than inhibitory control and when INT can co-occur with EXT. Because EXT and INT often co-occur and EXT often involves the lack of attentional and inhibitory control, relations of INT with EC may sometimes be found partly because of the co-occurrence of INT and EXT. Moreover, the inverse relation of EC with INT may be stronger in cultures that put a high premium on regulation (e.g., China).

EC and the Quality of Peer Relationships

Even in the preschool years, children viewed by adults as well regulated in their attention, behavior, and emotion tend to be relatively well liked rather than rejected by their peers (Wilson, 2003). For example, Olson and Lifgren (1988) found that behavioral measures of low regulation/EC and high impulsivity were correlated with concurrent negative sociometric nominations from preschool peers. It is interesting that high levels of positive peer nominations and/or low levels of negative nominations also predicted high EC a year later, suggesting that popular children may have more opportunities to develop their self-regulation.

Similar findings have been obtained for school-age children (Graziano, Reavis, Keane, & Calkins, 2007). For example, Wilson (2003) found that kindergartners and first graders who were nominated as liked and prosocial exhibited less difficulty shifting attention from negative to positive affect and were better able to regulate their behavior after experiencing social failure. Spinrad et al. (2006) found that EC predicted teacher-reported popularity over time when accounting for levels of popularity 2 years prior. In 5½-year-olds, measures of physiological vagal regulation (a physiological measure of emotion regulation) have been positively related to children’s social status. Of particular interest is the fact that this relation was mediated by girls’ superior social skills and boys’ lower levels of behavior problems (Walden, Lemerise, & Smith, 1999). Thus, children’s self-regulation/EC seems to affect children’s behavior with peers, which in turn affects their social status.

Comparable findings have been obtained in non-Western cultures. In Indonesia, Eisenberg, Pidada, et al. (2001) found that low teacher- and/or parent-reported EC was related to negative peer evaluations (disliked, fights) for third graders, whereas high adult-reported EC was related to positive peer nominations (liked, prosocial). Findings were similar 3 years later in a follow-up of this sample, although significant effects held primarily for boys (Eisenberg et al., 2004).

EC or related measures of regulation have been related to having friendships as well as sociometric popularity. Walden et al. (1999) found a negative association between emotion dysregulation (an aggregate of low regulation and children’s high affective intensity and emotional expressivity) and the number of reciprocated friendships with 4- and 5-year-old children. Similarly, Jensen-Campbell and Malcolm (2007) found that adult-reported attentional problems were related to low numbers of children’s reciprocated friendships and self-reports of low-quality friendships. Thus, there is evidence that EC is related not only to children’s acceptance by peers but also to the quality of their dyadic relationships.

EC and the Student–Teacher Relationship

Students who are disruptive and low in EC are likely to form a negative student–teacher relationship that could result in less positive feedback and instruction (e.g., less pursuit of social and academic goals, mastery orientations toward learning, and academic interest, Wentzel, 1997; see also Berndt & Keefe, 1995; Birch & Ladd, 1997; C. Murray & Greenberg, 2000; Raver, 2002). In addition, students who engage in antisocial behavior appear to be disliked by teachers and are less engaged in the classroom than their more socially competent peers (Wentzel, 1998). Moreover, EC has been positively related to the student–teacher relationship (Midgley, Feldlaufer, & Eccles, 1989).

Developing and maintaining a supportive student–teacher relationship is an important academic task, and this relationship has been positively related to students’ motivation (Alexander, Entwisle, & Dauber, 1993; Hamre & Pianta, 2005). Moreover, students’ perceived support from teachers predicts their pursuit of academic goals, even when controlling for parent and peer support (Hamre & Pianta, 2001), and declines in the quality of the student–teacher relationship appear to precede declines in student motivation and achievement (Midgley et al., 1989). Data from longitudinal studies support the premise that the student–teacher relationship is prospectively related to achievement and that the relations are significant even when controlling for general intelligence (Alexander et al., 1993; Hamre & Pianta, 2005). The accumulated body of evidence now strongly supports the premise that the relationships students form with their teachers are integral to their school readiness and long-term success (Wentzel, 1999; Wigfield, Eccles, Schiefele, Roeser, & Davis-Kean, 2006).

EC, School Relationships, and Classroom Engagement

Although data highlight the importance of students’ relationships with peers and teachers for school outcomes, there are findings consistent with the premise presented in Figure 1 that the association between the quality of relationships at school and academic outcomes is mediated by students’ engagement. Very early in elementary school it is crucial for children to become comfortable in their role as a student and to enjoy and participate in the school setting. Students’ engagement in the school setting is hypothesized to reflect motivation for learning and a goal orientation that guides behaviors linked to school success (Dweck, 1989). Finn (1993) argued that students who avoid participating in classroom activities are at an academic disadvantage beyond risks linked to race, ethnicity, language, or income. Students who participate in classroom activities and like the school setting should be motivated to pursue goals valued in that context (Alexander & Entwisle, 1988). In a series of studies, Ladd and colleagues found support for the premise that school liking and participation are antecedents of school achievement (Ladd, Birch, & Buhs, 1999; Ladd, Buhs, & Seid, 2000).

There are very few data on the relations between children’s EC and their school engagement or motivation. Indeed, Wigfield et al. (2006) noted that “the highest priority in this area is attention to the influence of emotions on motivation” (p. 987). We expect positive relations between EC and classroom engagement because in order to participate in classroom activities and feel comfortable in the student role, children likely need to modulate the emotions they experience. There is some, albeit limited, evidence to support the hypothesis that EC is positively related to school liking and participation (Valiente, Lemery-Chalfant, & Castro, 2007; Valiente et al., 2008). There is additional evidence to support the hypothesis that students’ relationships are predictive of their engagement. For example, Furrer and Skinner (2003) found that feelings of relatedness predicted engagement in school and academic performance in elementary school. Furthermore, peer-related competence (e.g., peer liking, relatedness with peers) in the early school years has been negatively correlated with concurrent and subsequent deficits in work habits and math and language/reading, negative school attitudes, school avoidance, and underachievement during the first year or two of schooling (Eisenberg, Sadovsky, & Spinrad, 2005; Ladd, 2003; O’Neil et al., 1997). Thus, the evidence, albeit limited and preliminary, is generally consistent with the mediated pathway of EC predicting the quality of children’s social relationships at school, which in turn predict their engagement in and performance at school.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, there is mounting evidence in support of the premise that students’ EC is important to their school readiness and success. There is far less work outlining the mechanisms that sustain these relations, although this is beginning to change. In this article, we have argued that students’ relationships with peers and teachers, as well as their engagement in classroom processes, mediate the links between EC and academic competence. The model presented in Figure 1 has theoretical and some empirical support, but experimental studies are needed in order to more rigorously test the ideas expressed therein. Moreover, although EC has often been related to social functioning and maladjustment in similar ways in other cultures (e.g., Eisenberg, Pidada, et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2004, 2008), few investigators have examined its role in academic functioning outside of North America. Finally, research explicitly testing the mediated relations depicted in Figure 1 is needed to examine the processes underlying the association between EC and academic outcomes.

Despite the limited body of work testing some of the mediated relations in our heuristic model, the model has implications for interventions and education. The model makes the point that how well children do at school is not due merely to their prior preparation and ability to learn. Social behavior and social relationships, as well as children’s abilities to regulate their behavior, attention, and emotions, also matter. Children’s EC seems to be critical for the quality of their behavior at school and their relations with teachers and peers. Although reviewing interventions is beyond the scope of this article, initial findings support the view that those that target children’s abilities to manage their behavior and emotion at school have positive effects on children’s problems behaviors and social competence (e.g., Domitrovich, Cortes, & Greenberg, 2007; Riggs, Greenberg, Kusché, & Pentz, 2006). Thus, interventions that target EC are likely to improve children’s liking of, and performance at, school. In addition, programs that improve the quality of children’s social interactions and their problem behaviors are also likely to improve children’s motivation and performance at school. In future studies, a greater focus on variables that mediate relations between children’ levels of EC/self-regulation and their school outcomes is desirable to better document the ways in which interventions can have effects on school-related outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Work on this article was supported by grants to Nancy Eisenberg from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and to Carlos Valiente from the National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Contributor Information

Nancy Eisenberg, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University.

Carlos Valiente, School of Social and Family Dynamics, Arizona State University.

Natalie D. Eggum, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University.

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Howell CT, Quay HC, Conners CK. National survey of problems and competencies among four- to sixteen-year-olds: Parents’ reports for normative and clinical samples. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1991;56(3):v–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR. Achievement in the first 2 years of school: Patterns and processes. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1988;53:1–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR, Dauber SL. First-grade classroom behavior: Its short- and long-term consequences for school performance. Child Development. 1993;64:801–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ, Keefe K. Friends’ influence on adolescents’ adjustment to school. Child Development. 1995;66:1312–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Nix RL, Greenberg MT, Blair C, Domitrovich CE. Executive functions and school readiness intervention: Impact, moderation, and mediation in the Head Start REDI program. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:821–843. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. The teacher–child relationship and children’s early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology. 1997;35:61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Razza RP. Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development. 2007;78:647–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block JH, Block J. The role of ego-control and ego-resiliency in the organization of behavior. In: Andrew Collins W, editor. Development of cognition, affect, and social relations: The Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology. Vol. 13. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1980. pp. 39–101. [Google Scholar]

- David KM, Murphy BC. Interparental conflict and preschoolers’ peer relations: The moderating roles of temperament and gender. Social Development. 2007;16:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis TA, Brotman LM, Huang K-Y, Gouley KK. Effortful control, social competence, and adjustment problems in children at risk for psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:442–454. doi: 10.1080/15374410701448513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry D, Reed MA. Anxiety-related attentional biases and their regulation by attentional control. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:225–236. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, Barnett WS, Thomas J, Munro S. Preschool program improves cognitive control. Science. 2007 November 30;318:1387–1388. doi: 10.1126/science.1151148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich CE, Cortes RC, Greenberg MT. Improving young children’s social and emotional competence: A randomized trial of the preschool “PATHS” curriculum. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2007;28:67–91. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dweck CS. Motivation. In: Lesgold A, Glaser R, editors. Foundations for a psychology of education. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1989. pp. 87–136. [Google Scholar]

- Eggum ND, Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Valiente C, Edwards A, Kupfer A, et al. Predictors of withdrawal: Possible precursors of avoidant personality disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:815–838. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Colder C, Edwards EP, Leonard KE. A longitudinal study of social competence among children of alcoholic and nonalcoholic parents: Role of parental psychopathology, parental warmth, and self-regulation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:36–46. doi: 10.1037/a0014839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Edwards EP, Leonard KE. A conceptual model for the development of externalizing behavior problems among kindergarten children of alcoholic families: Role of parenting and children’s self-regulation. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1187–1201. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland AJ, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, et al. The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development. 2001;72:1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA. Emotion, regulation, and the development of social competence. In: Clark MS, editor. Emotion and social behavior. Review of personality and social psychology. Vol. 14. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1992. pp. 119–150. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Maszk P, Holmgren R, et al. The relations of regulation and emotionality to problem behavior in elementary school children. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Reiser M. Dispositional emotionality and regulation: Their role in predicting quality of social functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:136–157. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Nyman M, Bernzweig J, Pinuelas A. The relations of emotionality and regulation to children’s anger-related reactions. Child Development. 1994;65:109–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Guthrie IK, Fabes RA, Shepard S, Losoya S, Murphy BC, et al. Prediction of elementary school children’s externalizing problem behaviors from attention and behavioral regulation and negative emotionality. Child Development. 2000;71:1367–1382. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Hofer C, Vaughan J. Effortful control and its socioemotional consequences. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 287–306. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Ma Y, Chang L, Zhou Q, West SG, Aiken L. Relations of effortful control, reactive undercontrol, and anger to Chinese children’s adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:385–409. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Pidada S, Liew J. The relations of regulation and negative emotionality to Indonesian children’s social functioning. Child Development. 2001;72:1747–1763. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Sadovsky A, Spinrad T. Associations among emotion-related regulation, language skills, emotion knowledge, and academic outcomes. New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development. 2005;109:109–118. doi: 10.1002/cd.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Sadovsky A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Losoya SH, Valiente C, et al. The relations of problem behavior status to children’s negative emotionality, effortful control, and impulsivity: Concurrent relations and prediction of change. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:193–211. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Shepard SA, Fabes RA, Murphy BC, Guthrie IK. Shyness and children’s emotionality, regulation, and coping: Contemporaneous, longitudinal, and across-context relations. Child Development. 1998;69:767–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Reiser M, Cumberland A, Shepard SA, et al. The relations of effortful control and impulsivity to children’s resiliency and adjustment. Child Development. 2004;75:25–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Morris AS. Regulation, resiliency, and quality of social functioning. Self and Identity. 2002;1:121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Cumberland A, Liew J, Reiser M, et al. Longitudinal relations of children’s effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:988–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0016213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Vaughan J, Hofer C. Temperament, self-regulation, and peer social competence. In: Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, Laursen B, editors. Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 473–489. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Zhou Q, Spinrad TL, Valiente C, Fabes RA, Liew J. Relations among positive parenting, children’s effortful control, and externalizing problems: A three-wave longitudinal study. Child Development. 2005;76:1055–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N, Jones S, Smith M, Guthrie I, Poulin R, et al. Regulation, emotionality, and preschoolers’ socially competent peer interactions. Child Development. 1999;70:432–442. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Martin CL, Hanish L. Peers and the transition to school; Paper presented at the Successful Transition to School Conference; Birmingham, AL. 1999. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Martin CL, Hanish LD, Anders MC, Madden-Derdich DA. Early school competence: The roles of sex-segregated play and effortful control. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:848–858. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.5.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, Perry MA, McDermott P. Preschool approaches to learning and their relationship to other relevant classroom competencies for low-income children. School Psychology Quarterly. 2004;19:212–230. [Google Scholar]

- Finn JD. School engagement and students at risk. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 1993. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED362322) [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Morris AS. Temperament and developmental pathways to conduct disorders. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:54–68. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furrer C, Skinner E. Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95:148–162. [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V, van Etten M. Specificity of relations between adolescents’ cognitive emotion regulation strategies and internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28:619–631. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouley KK, Brotman LM, Huang K-Y, Shrout PE. Construct validation of the Social Competence Scale in preschool-age children. Social Development. 2008;17:380–398. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano PA, Reavis RD, Keane SP, Calkins SD. The role of emotion regulation in children’s early academic success. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45:3–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumora G, Arsenio WF. Emotionality, emotion regulation, and school performance in middle school children. Journal of School Psychology. 2002;40:395–413. [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC. Early teacher–child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development. 2001;72:625–638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC. Can instructional and emotional support in the first-grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development. 2005;76:949–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Spinrad TL, Ryan P, Schmidt S. The expression and regulation of negative emotions: Risk factors for young children’s peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:335–353. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Craft SA. Parent-school involvement and school performance: Mediated pathways among socioeconomically comparable African American and Euro-American families. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95:74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hofer C, Eisenberg N, Reiser M. The role of socialization, effortful control, and ego resiliency in French adolescents’ social functioning. Journal of Research in Adolescence. 2010;20:555–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Campbell LA, Malcolm KT. The importance of conscientiousness in adolescent interpersonal relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33:368–383. doi: 10.1177/0146167206296104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK, Lofthouse N, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS. Differential risks of covarying and pure components in mother and teacher reports of externalizing and internalizing behavior across ages 5 to 14. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:267–283. doi: 10.1023/a:1023277413027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kids Count. Getting ready. Findings from the National School Readiness Indicators Initiative: A 17 state partnership. Providence, RI: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA, Sinclair RJ. Psychological, family, and peer predictors of academic outcomes in first- through fifth-grade children. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2000;92:449–457. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW. Probing the adaptive significance of children’s behavior and relationships in the school context: A child by environment perspective. Advances in Child Development. 2003;31:43–104. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2407(03)31002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Birch SH, Buhs ES. Children’s social and scholastic lives in kindergarten: Related spheres of influence? Child Development. 1999;70:1373–1400. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Buhs ES, Seid M. Children’s initial sentiments about kindergarten: Is school liking an antecedent of early classroom participation and achievement? Merrill Palmer Quarterly. 2000;46:255–279. [Google Scholar]

- Lemery KS, Essex MJ, Smider NA. Revealing the relation between temperament and behavior problem symptoms by eliminating measurement confounding: Expert ratings and factor analyses. Child Development. 2002;73:867–882. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ. Associations among emotionality, self-regulation, adjustment problems, and positive adjustment in middle childhood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2003;24:595–618. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ. Growth in temperament and parenting as predictors of adjustment during children’s transition to adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:819–832. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, West SG, Sandler IN. Temperament as a predictor of symptomatology in children: Addressing contamination of measures. Child Development. 1998;69:164–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland MM, Cameron CE, Connor CM, Farris CL, Jewkes AM, Morrison FJ. Links between behavioral regulation and preschoolers’ literacy, vocabulary, and math skills. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:947–959. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midgley C, Feldlaufer H, Eccles JS. Student/teacher relations and attitudes toward mathematics before and after the transition to junior high school. Child Development. 1989;60:981–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb03529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, Greenberg MT. Children’s relationship with teachers and bonds with school: An investigation of patterns and correlates in middle childhood. Journal of School Psychology. 2000;38:423–445. [Google Scholar]

- Murray K, Kochanska G. Effortful control: Factor structure and relation to externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:503–514. doi: 10.1023/a:1019821031523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Do children’s attention processes mediate the link between family predictors and school readiness? Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:581–593. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldehinkel AJ, Hartman CA, De Winter AF, Veenstra R, Ormel J. Temperament profiles associated with internalizing and externalizing problems in preadolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:421–440. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Lifgren K. Concurrent and longitudinal correlates of preschool peer sociometrics: Comparing rating scale and nomination measures. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1988;9:409–420. [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Sameroff AJ, Kerr DCR, Lopez NL, Wellman HM. Developmental foundations of externalizing problems in young children: The role of effortful control. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:25–45. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil R, Welsh M, Parke RD, Wang S, Strand C. A longitudinal assessment of the academic correlates of early peer acceptance and rejection. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26:290–303. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2603_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Rothbart MK. Research on attention networks as a model for the integration of psychological science. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC. Emotions matter: Making the case for the role of young children’s emotional development for early school readiness. Social Policy Report. 2002;16(3):3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs NR, Blair CB, Greenberg MT. Concurrent and 2-year longitudinal relations between executive function and the behavior of 1st and 2nd grade children. Child Neuropsychology. 2003;9:267–276. doi: 10.1076/chin.9.4.267.23513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs NR, Greenberg MT, Kusché CA, Pentz MA. The mediational role of neurocognition in the behavioral outcomes of a social-emotional prevention program in elementary school students: Effects of the PATHS curriculum. Prevention Science. 2006;7:91–102. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, personality development. 6th ed. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 99–166. (Series Ed.) (Vol. Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Schultz D, Izard CE, Ackerman BP, Youngstrom EA. Emotion knowledge in economically disadvantaged children: Self-regulatory antecedents and relations to social difficulties and withdrawal. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:53–67. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401001043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoda Y, Mischel W, Peake PK. Predicting adolescent cognitive and self-regulatory competencies from preschool delay of gratification: Identifying diagnostic conditions. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:978–986. [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescents’ emotion regulation in daily life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Development. 2003;74:1869–1880. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Fabes RA, Valiente C, Shepard SA, et al. Relation of emotion-related regulation to children’s social competence: A longitudinal study. Emotion. 2006;6:498–510. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N, Gaertner B, Popp T, Smith CL, Kupfer A, et al. Relations of maternal socialization and toddlers’ effortful control to children’s adjustment and social competence. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1170–1186. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente C, Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Reiser M, Cumberland A, Losoya SH, et al. Relations among mothers’ expressivity, children’s effortful control, and their problem behaviors: A four-year longitudinal study. Emotion. 2006;6:459–472. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente C, Lemery-Chalfant K, Castro KS. Children’s effortful control and academic competence: Mediation through school liking. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2007;53:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Valiente C, Lemery-Chalfant K, Reiser M. Pathways to problem behaviors: Chaotic homes, parent and child effortful control, and parenting. Social Development. 2007;16:249–267. [Google Scholar]

- Valiente C, Lemery-Chalfant K, Swanson J, Reiser M. Prediction of children’s academic competence from their effortful control, relationships, and classroom participation. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2008;100:67–77. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.100.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden T, Lemerise E, Smith MC. Friendship and popularity in preschool classrooms. Early Education and Development. 1999;10:351–371. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Student motivation in middle school: The role of perceived pedagogical caring. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1997;89:411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1998;90:202–209. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Social–motivational processes and interpersonal relationships: Implications for understanding motivation at school. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1999;91:76–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Peers and academic functioning at school. In: Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, Laursen B, editors. Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 531–547. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield A, Eccles JS, Schiefele U, Roeser R, Davis-Kean P. Development of achievement motivation. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, personality development. 6th ed. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 933–1002. (Series Ed.) (Vol. Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BJ. The role of attentional processes in children’s prosocial behavior with peers: Attention shifting and emotion. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:313–329. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Eisenberg N, Wang Y, Reiser M. Chinese children’s effortful control and dispositional anger/frustration: Relations to parenting styles and children’s social functioning. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:352–366. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Hofer C, Eisenberg N, Reiser M, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA. The developmental trajectories of attention focusing, attentional and behavioral persistence, and externalizing problems during school-age years. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:369–385. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Wang Y, Deng X, Eisenberg N, Wolchik SA, Tein J-Y. Relations of parenting and temperament to Chinese children’s experience of negative life events, coping efficacy, and externalizing problems. Child Development. 2008;79:493–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman BJ. Developing self-fulfilling cycles of academic regulation: An analysis of exemplary instructional models. In: Schunk DH, editor. Self-regulated learning: From teaching to self-reflective practice. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]