Abstract

This review summarizes findings on the epidemiology and etiology of anxiety disorders among children and adolescents including separation anxiety disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, agoraphobia, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder, also highlighting critical aspects of diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. Childhood and adolescence is the core risk phase for the development of anxiety symptoms and syndromes, ranging from transient mild symptoms to full-blown anxiety disorders. This article critically reviews epidemiological evidence covering prevalence, incidence, course, and risk factors. The core challenge in this age span is the derivation of developmentally more sensitive assessment methods. Identification of characteristics that could serve as solid predictors for onset, course, and outcome will require prospective designs that assess a wide range of putative vulnerability and risk factors. This type of information is important for improved early recognition and differential diagnosis as well as prevention and treatment in this age span.

Keywords: Anxiety, Assessment, Diagnosis, Boundaries, Onset, Course, Outcome

ANXIETYAND ANXIETY DISORDERS IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS AND ITS ASSESSMENT

Childhood and adolescence is the core risk phase for the development of symptoms and syndromes of anxiety that may range from transient mild symptoms to full-blown anxiety disorders. Challenges from a research perspective include its reliable and clinically valid assessment to determine its prevalence and patterns of incidence, and the longitudinal characterization of its natural course to better understand what characteristics are solid predictors for more malignant courses as well as which are likely to be associated with benign patterns of course and outcome. This type of information is particularly needed from a clinical perspective to inform about improved early recognition and differential diagnosis as well as preventions and treatment in this age span.

Anxiety refers to the brain response to danger, stimuli that an organism will actively attempt to avoid. This brain response is a basic emotion already present in infancy and childhood, with expressions falling on a continuum from mild to severe. Anxiety is not typically pathological as it is adaptive in many scenarios when it facilitates avoidance of danger. Strong cross-species parallels—both in organisms’ responses to danger and in the underlying brain circuitry engaged by threats—likely reflect these adaptive aspects of anxiety.1 One frequent and established conceptualization is that anxiety becomes maladaptive when it interferes with functioning, for example when associated with avoidance behavior, most likely to occur when anxiety becomes overly frequent, severe, and persistent.2 Thus, pathological anxiety at any age can be characterized by persisting or extensive degrees of anxiety and avoidance associated with subjective distress or impairment. The differentiation between normal and pathological anxiety, however, can be particularly difficult in children because children manifest many fears and anxieties as part of typical development3,4 (Table 1). Although these phenomena might be acutely distressing, they occur in most children and are typically transient. For example, separation anxiety normatively occurs at 12 to 18 months, fears of thunder or lightning at 2 to 4 years, and so forth. Thus, given that such anxiety occurs in most children and typically does not persist, distress, in and of itself, represents an inadequate criterion for distinguishing among normal and pathological anxiety states in children. This problem creates unique challenges when trying to distinguish among normal, subclinical, and pathological anxiety states in children. Other challenges in the assessment of childhood fears and anxiety are that children at younger ages may have difficulties in communicating cognition, emotions, and avoidance, as well as the associated distress and impairments, to the diagnostician5 because they might lack the cognitive capabilities used to communicate information vital to the application of the diagnostic classification system. Thus, developmental differences (eg, cognition, language skills, emotional understanding) must be carefully considered when assessing anxiety in young people to make a diagnostic decision.6

Table 1.

Normative anxiety and fears in childhood and adolescence

| Age | Development Conditioned Periods of Fear and Anxiety | Psychopathological Relevant Symptoms | Corresponding DSM-IV Anxiety Disorder | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early infancy | Within first weeks | Fear of loss, eg, physical contact to caregivers | – | – |

| 0–6 months | Salient sensoric stimuli | – | – | |

| Late infancy | 6–8 months | Shyness/anxiety with stranger | Separation anxiety disorder | |

| Toddlerhood | 12–18 months | Separation anxiety | Sleep disturbances, nocturnal panic attacks, oppositional deviant behavior | Separation anxiety disorder, panic attacks |

| 2–3 years | Fears of thunder and lightening, fire, water, darkness, nightmares | Crying, clinging, withdrawal, freezing, eloping seek for security and physical contact, avoidance of salient stimuli (eg, turning the light on), pavor nocturnus, enuresis | Specific phobias (environmental subtype), panic disorder | |

| Fears of animals | – | Specific phobias (animal subtype) | ||

| Early childhood | 4–5 years | Fear of death or dead people | – | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic attacks |

| Primary/elementary school age | 5–7 years | Fear of specific objects (animals, monsters, ghosts) | – | Specific phobias |

| Fear of germs or getting a serious illness | – | Obsessive compulsive disorder | ||

| Fear of natural disasters, fear of traumatic events (eg, getting burned, being hit by a car or truck) | – | Specific phobias (environmental subtype), acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder | ||

| School anxiety, performance anxiety | Withdrawal, timidity, extreme shyness to unfamiliar people and peers, feelings of shame | Social anxiety disorder | ||

| Adolescence | 12–18 years | Rejection from peers | Fear of negative evaluation | Social anxiety disorder |

Data from Morris RJ, Kratochwill TR. Childhood fears and phobias. In: Kratochwill TR, Morris RJ, editors. The practice of child therapy. 2nd ed. New York: Pergamon; 1991. p. 76–114; and Muris P, Merckelbach H, Mayer B, et al. Common fears and their relationship to anxiety disorders symptomatology in normal children. Pers Individ Diff 1998;24(4):575–8.

Anxiety disorders are described and classified in diagnostic systems such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM, currently version IV-TR, American Psychiatric Association)2 or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD, currently version 10, World Health Organization)7 (Table 2). Across these systems, many anxiety disorders share common clinical features such as extensive anxiety, physiological anxiety symptoms, behavioral disturbances such as extreme avoidance of feared objects, and associated distress or impairment. Nonetheless, differences exist and it should be noted that narrowly categorized anxiety disorders such as panic disorder, agoraphobia, and subtypes of specific phobias also exhibit a substantial degree of phenotypical diversity or heterogeneity.

Table 2.

Classification of anxiety disorders according to ICD-10 and DSM-IV

| ICD-10 | DSM-IV | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurotic, somatoform, and stress-related disorders | Anxiety disorders | Different criteria in children (vs adults) Information on childhood anxieties as highlighted in DSM text portion |

||

| F40 | Phobic disorder | |||

| F40.0 | Agoraphobia | |||

| F40.00 | Agoraphobia without panic disorder | 300.22 | Agoraphobia without history of panic disorder | – |

| F40.01 | Agoraphobia with panic disorder | 300.21 | Panic disorder with agoraphobia | – |

| F40.1 | Social phobia | 300.23 | Social phobia |

|

| F40.2 | Specific (isolated) phobia | 300.29 | Specific phobia |

|

| F40.8 | Other | – | – | – |

| F40.9 | Not specified | 300.00 | Anxiety disorders NOS | – |

| F41 | Other anxiety disorders | |||

| F41.0 | Panic disorder (episodic paroxysmal anxiety) | 300.01 | Panic disorder without agoraphobia | – |

| F41.1 | Generalized anxiety disorder | 300.02 | Generalized anxiety disorder |

|

| F41.2 | Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder | – | – | – |

| F41.3 | Other mixed anxiety disorders | – | – | – |

| F41.8 | Other | – | – | – |

| F41.9 | Not specified | 300.00 | Anxiety disorders NOS | – |

| F42 | Obsessive compulsive disorder | 300.3 | Obsessive-compulsive disorder |

|

| F42.0 | Predominantly obsessional thoughts or ruminations | |||

| F42.1 | Predominantly compulsive acts (obsessional rituals) | |||

| F42.2 | Mixed obsessional thoughts and acts | |||

| F42.8 | Other | |||

| F42.9 | Not specified | |||

| F43 | Reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorder | |||

| F43.0 | Acute stress reaction | 308.3 | Acute stress disorder | – |

| F43.1 | Posttraumatic stress disorder | 309.81 | Posttraumatic stress disorder |

|

| F43.2 | Adjustment disordersa | |||

| F43.8 | Other | |||

| F43.9 | Not specified | |||

| F93 | Emotional disorders with onset specific to childhood | Disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood or adolescence | ||

| F93.0 | Separation anxiety disorder of childhood | 309.21 | Separation Anxiety Disorder | |

| F93.1 | Phobic anxiety disorder of childhood | – | – | |

| F93.2 | Social anxiety disorder of childhood | – | – | |

| F93.8 disorders | Other childhood emotional | – | – | |

| F93.9 | Childhood emotional disorder, unspecified | – | – | |

Different criteria in children versus. adults: In children, symptoms may also manifest as regressive behaviors such as enuresis, thumb-sucking, or baby talk. Conduct disorders may be associated feature, particularly in adolescents.

Data from ICD-107 (WHO) and DSM-IV2 (APA).

In the assessment of anxiety features in children one has to recognize that the core diagnostic criteria might present differently in the young, requiring special assessment strategies and the recognition of special features that are unique to or characteristic for this age group. DSM-IV acknowledges this by adding for some disorders, though not consistently, some of the features that might present differently in children and adolescents. With the exception of separation anxiety disorder, all of the anxiety disorders in DSM-IV are grouped together irrespective of the age at which the disorder manifests; separation anxiety disorder, in contrast, is defined as manifesting before adulthood. Thus for most of the anxiety disorders, differences between diagnostic criteria for children and adults, if any, are provided within the same criteria set. Examples include duration commentaries, differences in symptom type or count, or insights into the excessiveness/inadequacy of fear (Table 2). More specifically, for example, the threshold in DSM-IV for diagnosing generalized anxiety disorder is lower in children than adults (1 instead of 3 out of 6 symptoms); in phobias, children are not required to judge their anxiety as excessive or unreasonable, yet duration must be at least 6 months among individuals under the age of 18 years. For ICD-10, in contrast to DSM-IV, children receive other diagnostic codings, separate from adults, for anxiety disorders that reflect exaggerations of normal developmental trends. The specific differences in diagnosis and diagnostic criteria between children and adults for DSM-IV and ICD-10 are listed in Table 2.

It should be noted that it remains unspecified as to what age range the “child-specific” diagnostic criteria refer. Given cognitive and language development, the increasing importance of peer relationships, and the seeking of autonomy from parents, it is crucial to specify similarities and differences in anxiety expressions for different ages (eg, childhood up to 12 years, adolescence 13 to 17 years). This important issue is rarely acknowledged in the current diagnostic criteria, and not even in the text portions of the DSM that generally contain important additional information for diagnosticians and clinicians (see Table 2).

There is also little guidance in the diagnostic systems on developmentally appropriate assessment of anxiety disorders to identify those in need of treatment. Although the development of explicit descriptive diagnostic criteria has facilitated the development of diagnostic instruments for the assessment of anxiety disorders, diagnosticians and clinicians should be aware of their limitations, particularly related to developmental issues in obtaining self-reports from children and adolescents.6,8,9

Table 3 provides a selection of the most commonly used diagnostic tools for assessment of anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. In children, applications of these tools to younger children might be more problematic than to older children, as reflected in poorer psychometric data. This problem undoubtedly at least partly reflects the difficulty young children face when trying to communicate information about internally experienced affective states.5 Therefore, assessments in young children often require solicitation of information from multiple sources beyond the child to reliably and validly distinguish among normal anxiety, subclinical, and pathological anxiety syndromes and disorders. This assessment includes parent or teacher reports. In older children and adolescents, in contrast, diagnostic decisions can rely heavily on information provided directly by the patient, although even in this age group parallel informants can also be helpful.

Table 3.

Assessment in children and adolescents

| Instruments | Description | Information Level | Age | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inventories on symptom levels | |||||

| Anxiety | |||||

| CASI | Child Anxiety Sensitivity Index | 18-items to evaluate separation anxiety, panic attacks and agoraphobic fears and children’s belief that anxiety symptoms have aversive consequences | Self-report | – | Silverman et al (1991) |

| MASC | Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children | 39 items, 4 scales: physical symptoms, social anxiety, harm avoidance, separation/panic anxiety | Self-report, parent report | 8–16 | March, Parker Sullivan, Stallings & Comers (1997) |

| RCMAS | Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale | 37 items, 3 factors: physiological manifestations of anxiety, worry and oversensitivity, fear/concentration | Self-report | 6–19 | Reynolds & Richmond (1978) |

| FSS-C | Fear Survey Schedule for Children—Revised | 80 items describing fears, loading on 5 factors fear of failure and criticism, fear of the unknown, fear of injury and small animals, fear of danger and death, medical fears | – | 7–18 | Ollendick (1983) |

| PARS | Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale | Anxiety severity scale specifically addressing the separation anxiety, social phobia and GAD symptoms | Clinical rating | 6–17 | RUPP Anxiety Study Group (2002) |

| CBCL, YSR, TRF | Child Behavior Checklist, Youth Self-Report, Teacher Report Form | Behavior inventory including a broad subscale of internalizing symptomatology, a specific depression/anxiety scale | – | 4–18; 11+ (YSR) | Achenbach (1991) |

| HARS | Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale | Developed according to Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale for use in children | Clark & Donovan (1994) | ||

| STAIC | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children | 2 independent 20-item inventories to assess state and trait anxiety | – | 8–12 | Spielberger (1973) |

| Social phobia | |||||

| LSAS | Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale | Evaluation of severity of fear and avoidance symptoms for social and performance-related situations; 4 subscales and total fear and total avoidance scores | Self-report | – | Liebowitz (1987) |

| BSPS | Brief Social Phobia Scale | Rating of fear, avoidance, severity, and somatic symptoms of social situations | Self-report | 18+, adolescents | Davidson et al (1991, 1997) |

| SPAI-C | Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory for Children | 39 items to assess somatic, cognitive and behavioral responses to a variety of social and performance situations | Self-report | 8–18 | Turner et al (1989); Beidel et al (1995, 2000) |

| SAS-C, SAS-A | Social Anxiety Scale for Children—Revised, Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents | 22-item inventory with 3 factors: fear of negative evaluation, social avoidance and distress specific to new situations, generalized social avoidance and distress | Self-report, parent report | – | La Greca & Stone (1993) |

| SIAS | Social Interaction Anxiety Scale | Assesses fear of interacting in dyads and groups and fear of scrutiny | Self-report | – | Mattick & Clarke (1998) |

| Specific phobias | |||||

| FSS-C | Fear Survey Schedule for Children—Revised | 80 items describing fears, loading on 5 factors fear of failure and criticism, fear of the unknown, fear of injury and small animals, fear of danger and death, medical fears | – | 7–18 | Ollendick (1983) |

| Generalized anxiety | |||||

| PSWQ-C | Penn State Worry Questionnaire— Children and Adolescents | Adaptation of the Penn state worry questionnaire for use with children and adolescents to assess intensity and inability to control pathological worrying with 16 items (PSWQ-C). The PSWQ-C demonstrated good convergent and discriminant validity, and excellent reliability | Self-report | 6–18 | Chorpita et al (1997) |

| Categorical diagnostic inventories | |||||

| SCARED | Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders | 41 item; assesses DSM symptoms of panic, separation anxiety, social phobia, GAD, and school phobia | Self-report, parent report | – | Birmaher et al (1997, 1999) |

| ADIS-C/P | Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV—Child and Parent Version | Semistructured, interviewer-observer format, diagnoses of lifetime and current anxiety, mood, externalizing disorders and screening for other disorders | Self-report, parent report | DiNardo, O’Brien, Barlow, Waddell & Blanchard (1983) | |

| K-SADS | Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-age Children—Present and Lifetime Version (Kiddie-SADS) | Semistructured diagnostic interview to derive DSM diagnoses, including severity ratings | Self-report, parent report | 6–17 | Kaufman, Birmaher, Brent, Rao & Ryan (1997) |

| NIMHDISC-IV | NIHM Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV | Highly structured interview, follows a symptom-orientated structure and covers most axis-I disorders | Self-report | 6–17 | Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan & Schwab-Stone (2000) |

| DICA | Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents | Structured syndrome-orientated interview, also parent version (DICA-P) available | Self-report, parent report | 6–17 | Herjanic & Reich (1982); Welneret et al (1987) |

| CAEF | Children’s Anxiety Evaluation Form | Combination of semistructured interview+chart review+direct observation | – | – | Hoehn-Saric et al (1987) |

| CAPA | Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment | Assesses 30 different categorical disorders, family, peer, academic functioning, life events, service use | Self-report, parent report | 8+ | Angold & Costello (2000); Angold et al (1995) |

| CIDI | Composite International Diagnostic Interview | Standardized assessment of symptoms, syndromes and diagnoses of 48 mental disorders according to DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria along with information about onset, duration, and severity; respond lists to increase validity and to diminish recall bias | Self-report | 14–65 | Wittchen & Pfister (1997) |

| CSA | Children’s Assessment Schedule | Semistructured psychiatric interview to determine specific diagnoses for clinical practice, or to derive a total score of problems or symptoms, separate scores for specific content areas or symptom complexes | Self-report | 6–17 | Hodges et al (1982) |

Note: References from this table are available from the corresponding author.

Beyond these problems, unclear rules for applying diagnostic thresholds and variations in the methods used to aggregate information from different sources may drastically influence prevalence estimates (see later discussion) and might also impact findings from basic and epidemiological research. Thus, anxiety disorders in children and adolescents cannot be easily assessed with standard questionnaires or interviews that have been derived from adult instruments. In fact, the use of structured and standardized interviews for children and adolescents has much improved the reliability and validity of anxiety diagnoses in children and adolescents in the last 2 decades. Such instruments also have an advantage over symptom scales in that they allow a better delineation of transient subclinical manifestations of anxiety from anxiety disorders that were shown to have predictive validity and even concrete implications for prevention early intervention, and treatment.

The next section highlights developmental issues in anxiety, with focus on anxiety disorders (1) by critically reviewing recent data on the prevalence, incidence, age of onset, natural course, and longitudinal outcome of anxiety disorders, including comorbidity and psychosocial impairments and disabilities, and (2) by addressing important correlates and potential risk factors. The review focuses on the following categorically defined anxiety disorders: separation anxiety disorder, specific phobias, social phobia, agoraphobia, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder are not covered in this article because of additional complicating issues involved with these diagnoses, for example, controversy in regard to their grouping with the other anxiety disorders.10 As an attempt is made to provide information on development, the authors focus on children (defined here as up to age 12), adolescence (defined here as ages 13 to 17), and young adults (defined here as ages 18 to 35 years).

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF ANXIETY DISORDERS IN CHILDHOOD AND ADOLESCENCE

Prevalence and Onset

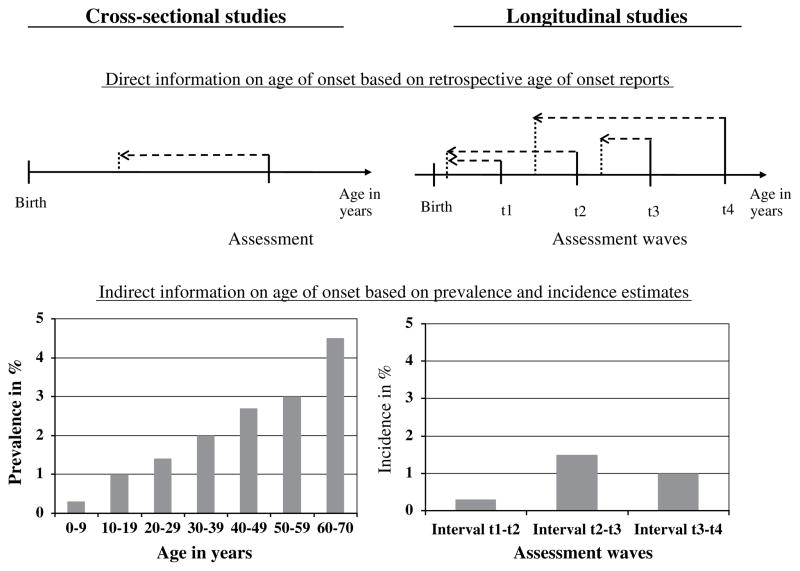

There is persuasive evidence from a range of studies that anxiety disorders are the most frequent mental disorders in children and adolescents, and thus seem to be the earliest of all forms of psychopathology. The onset of anxiety disorders (or symptoms/syndromes of anxiety) has been assessed in youth and adult samples, in cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys, most frequently by using the answers of the respondents to questions like “When was the first time you experienced…” (Fig. 1). Of note, such reports may be subject to recall bias,11 particularly in studies among older adults or in studies that retrospectively cover long time periods. As a consequence, reports of mean ages of onset are likely to be heavily influenced by the age range of the studied population (higher mean estimates in adult studies). Thus, age of onset distribution curves that cumulate recently assessed new cases across age (Fig. 2) are more informative and reliable with regard to actual onset patterns and core incidence periods (ie, high-risk phases for first onset of disorders).

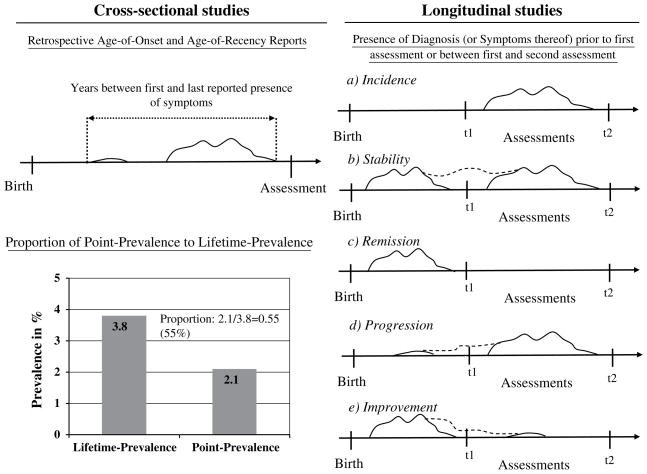

Fig. 1.

Assessing onset of anxiety disorders. The age of onset of anxiety disorders can be directly assessed by asking “When was the first time you experienced….” The retrospectively reported ages often reflect the syndrome, rather than disorder onset, and can be subject to recall bias. This fact is indirectly reflected by observations from longitudinal studies whereby different ages of onset are reported for the same condition at various assessment waves. Other sources of information on age of onset are prevalence estimates for disorders in aggregated age groups (mostly reported in cross-sectional studies). More reliably but also more rare, incidence reports from longitudinal studies (ie, the proportion of new cases in a defined time interval) provide insights into the disorder onset.

Fig. 2.

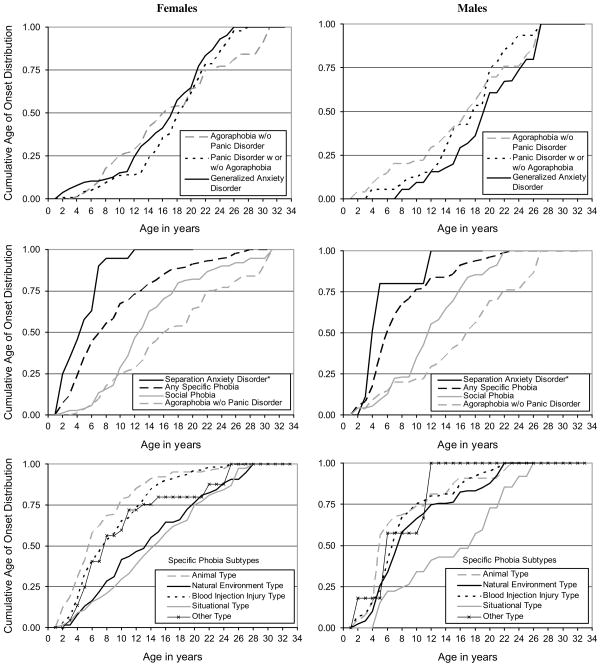

Patterns of age of onset of anxiety disorders (EDSP; N = 3021). (Note: In phobias impairment was required among subjects aged 18 years or older; *Separation Anxiety Disorder was only assessed in a subsample at T1.)

Findings suggest that onset of the first or any anxiety disorder is clearly in childhood (eg, Refs.12,13,14). Yet, leaving aside that some anxiety disorders might be preceded in their onset by other earlier comorbid anxiety disorders, there is some noteworthy heterogeneity between the specific anxiety disorders that reveals a temporal sequence of core risk periods for first onset of anxiety disorders in childhood and adolescence. In terms of validation these differences in age of onset provide one important indicator for separating different types of anxiety disorders.15 The earliest age of onset has been consistently found for separation anxiety disorder and some types of specific phobias (particularly the animal, blood injection injury, and environmental type), with most cases emerging in childhood before the age of 12 years,12,16,17 followed by the onset of social phobia with incidences in late childhood and throughout adolescence, with very few cases emerging after the age of 25.12,18,19 Panic disorder, agoraphobia, and GAD, in contrast, have their core periods for first onset in later adolescence with further first incidences in early adulthood,12,14,20 despite the fact that some cases, especially with panic attacks, might occur as early as age 12 years or before.21 Particularly for GAD as defined by the 6-month duration criterion, new cases also emerge throughout middle and late adulthood.12,20,22 It should be noted, however, that some doubts have been expressed about whether the 6-month duration criterion for GAD is appropriate in general23,24 and useful in children and adolescents in particular.25 Indirect evidence for GAD of shorter duration comes from studies using the former diagnosis of overanxious disorder (OAD), for which considerably earlier onsets and higher prevalence rates have been found among children (Table 4). Although the lack of specific diagnostic continuity for OAD into adulthood26 might speak against the definition of GAD by using a shorter duration, an accordant change of diagnostic criteria of GAD for children in DSM-V is currently under investigation.

Table 4.

Prevalence (%) of anxiety disorders in children, adolescents and young adults

| Study (Country) | Reference | Instrument | N | Age | Source | Any Anxiety Disorder |

Specific Phobia |

Social Phobia |

Agoraphobia |

Panic Disorder |

GAD/OAD |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime | Period | Lifetime | Period | Lifetime | Period | Lifetime | Period | Lifetime | Period | Lifetime | Period | ||||||

|

DSM-III-R | |||||||||||||||||

| DMHDS (New Zealand) | McGee et al (1990) | DISC | 943 | 15 | P/C | – | – | – | 3.6c | – | 1.1c | – | – | – | – | – | [5.9]c |

| Feehan et al (1994) | DIS-m-R | 930 | 17–19 | C | – | – | – | 6.1c | – | 11.1c | – | 4.0c | – | 0.8c | – | 1.8c | |

| Newman et al (1996) | DIS | 961 | 21 | C | – | – | – | 8.4c | – | 9.7c | – | 3.8c | – | 0.6c | – | 1.9c | |

| Kim-Cohen et al (2003) | DIS | 967 | 26 | C | – | – | – | 7.1 c | – | 10.7c | – | – | – | 3.9c | – | 5.5c | |

| CHDS (New Zealand) | Fergusson et al (1993) | DISC-P | 986 | 15 | P | – | 3.9c | – | 1.3c | – | 0.7c | – | – | – | – | – | 1.7 [0.6]c |

| DISC-C | 965 | C | – | 10.8c | – | 5.1 c | – | 1.7 c | – | – | – | – | – | 4.2 [2.1]a | |||

| Woodward & Fergusson (2001) | DIS | 964 | 15–16 | P/C | 29.9 | – | 20.6 | – | 2.9 | – | 1.5d | – | – | – | 11.0 [4.7] | – | |

| OADP (USA) | Lewinsohn et al (1993) | K-SADS | 1710 | 13–19 (T1) | C | 8.8 | – | 2.0 | – | 1.4 | – | 0.7 | – | 0.8 | – | [1.3] | – |

| 1 year FU (T2) | C | 9.2 | 1.5 | – | 1.5 | – | 0.6 | – | 1.2 | – | [1.2] | – | |||||

| Dutch-A (Netherlands) | Verhulst et al (1997) | DISC | 780 | 13–18 | P | – | 16.5b | – | 9.2b | – | 6.3b | – | 1.9b | – | 0.3b | – | 0.7 [1.5]b |

| DISC | C | – | 10.0b | – | 4.5b | – | 3.7b | – | 0.7b | – | 0.2b | – | 0.6 [1.8]b | ||||

| ZESCAP (Switzerland) | Steinhausen et al (1998) | DISC | 379 | 6–17 | P | – | 11.4b | – | 5.8b | – | 4.7 b | 1.9 b | – | – | 0.5 [2.1]b | ||

| QCMHS (Canada) | Breton et al (1999) | DISC | 2400 | 6–8 | C | – | 9.2b | – | 3.2b | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3.9b |

| P | – | 17.5b | – | 14.6b | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2.7b | |||||

| 9–11 | C | – | 5.8b | – | 1.3b | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3.8b | ||||

| P | – | 14.6b | – | 12.6b | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2.9 b | |||||

| 12–14 | C | – | 12.2b | – | 10.2b | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.7 b | ||||

| P | – | 12.1b | – | 7.5b | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5.5 b | |||||

| Quebec (Canada) | Romano et al (2001) | DISC | 1201 | 14–17 | C | – | 8.9b | – | 1.5b | – | 4.6b | – | 1.9 b | – | – | – | 1.1 [2.6]b |

| DISC | P | – | 6.5b | – | 1.0b | – | 2.9b | – | 0.9 b | – | – | – | 0.8 [2.3]b | ||||

| P/C | – | 14.0b | – | 2.5b | – | 6.9b | – | 2.8 b | – | – | – | 1.7 [4.5]b | |||||

| WIC (USA) | Keenan et al (1997) | K-SADS | 104 | 5 | C | – | – | 11.5 | – | 4.6 | – | – | – | – | – | [1.1] | – |

| DSM-IV | |||||||||||||||||

| GSMS (USA) | Bittner et al (2007) | CAPA | 906 | 9/11/13 | P/C | – | 16.1a | – | 0.6a | – | 1.5a | – | 2.5a | – | 3.1a | – | 5.8 [6.6]a |

| 906 | <13 | P/C | – | 6.6a | – | 0.4a | – | 0.6a | – | 0.1a | – | (0.2)a | – | 1.8 [1.7]a | |||

| 906 | >13 | P/C | – | 10.6a | – | 0.2a | – | 1.0a | – | 2.4a | – | (3.0)a | – | 4.0 [5.5]a | |||

| EDSP (Germany) | Wittchen et al (1998); Wittchen, Stein & Kessler (1999) | CIDI | 3021 | 14–24 | C | 14.4 | 9.3c | 2.3 | 1.8c | 3.5 | 2.6c | 2.6 | 1.6c | 1.6 | 1.2c | 0.8 | 0.5c |

| Wittchen et al (1999) | CIDI | 1395 | 14–17 | C | 21.3 | 14.5c | 17.1 | 10.9c | 3.7 | 2.9c | 2.8 | 2.1 c | 0.7 | 0.3c | 0.3 | 0.2c | |

| BJS (Germany) | Essau et al (1998); Essau et al (2000) | CAPI | 1035 | 12–17 | C | 18.6 | 11.3c | 3.5 | 2.7c | 1.6 | 1.4c | 4.1 | 2.7c | 0.5 | 0.5c | 0.4 | 0.2c |

| 380 | 12–13 | C | 14.7 | 8.9c | 2.6 | 2.1c | 0.5 | 0.5c | 2.4 | 1.3c | 0.0 | 0.0c | 0.0 | 0.0c | |||

| 350 | 14–15 | C | 19.7 | 12.0c | 3.1 | 2.6c | 2.0 | 1.1c | 4.9 | 3.4c | 0.9 | 0.9c | 0.9 | 0.3c | |||

| 305 | 16–17 | C | 22.0 | 13.4c | 4.9 | 3.6c | 2.6 | 2.6c | 5.2 | 3.6c | 0.7 | 0.7c | 0.3 | 0.3c | |||

| CCCS (USA) | Angold et al (2002) | CAPA | 920 | 9–17 | – | – | – | 0.4a | – | 1.4a | – | 0.5a | – | 1.2a | – | – | |

| New Zealand Mental Health Survey (New Zealand) | Wells et al (2006) | CIDI | 12,992 | 16+ | C | – | 14.8c | – | 7.3c | – | 5.1c | – | 0.6c | 1.7c | 2.0c | ||

| 16–24 | C | – | 17.7c | – | 9.3c | – | 7.0c | – | 0.7c | – | 2.4c | – | 1.6c | ||||

| IPRP-Study (Puerto Rico) | Canino et al (2004) | DISC | 1886 | 4–17 | P/C | – | 6.9c | – | – | – | 2.5c | – | – | – | 0.5c | – | 2.2c |

| Taiwan Epidemiological Study of Mental Disorders in Adolescents (Taiwan) | Gau et al (2005) | K-SADS-E | 1070 | Seventh grade | C | – | 9.2a | – | 5.0a | – | 3.4a | – | 0.2a | 0.2a | – | 0.7a | |

| 1051 | Eighth grade | C | – | 7.4a | – | 5.6a | 1.8a | 0.0a | 0.1a | 0.3a | |||||||

| 1035 | Ninth grade | C | – | 3.1a | – | 0.7a | – | 2.0a | – | 0.0a | – | 0.0a | – | 0.4a | |||

Note: References from this table are available from the corresponding author. GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; OAD, overanxious disorder; [ ] indicates overanxious disorder, () indicates panic attacks; P, parent report; C, child report.

Study abbreviations in alphabetical order: BJS, Bremer Jugendstudie (Bremen Adolescent Study); CCCS, Caring for Children in the Community Study; CHDS, Christchurch Health and Development Study; DMHDS, Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study; Dutch-A, Dutch Adolescents; EDSP, Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology; GSMS, Great Smoky Mountains Study; IPRP-Study, Island of Puerto Rico Prevalence Study; OADP, Oregon Adolescent Depression Project; QCMHS, Quebec Child Mental Health Survey; ZESCAP, Zurich Epidemiological Study of Child and Adolescent Psychopathology.

Abbreviations of diagnostic interviews: CAPA, Child and Adolescent Diagnostic Assessment; CAPI, Computer Assisted Psychiatric Interview (based on CIDI); CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DICA, Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents; DIS, Diagnostic Interview Schedule; DISC, Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; K-SADS, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-age Children; SPIKE, Structured Psychopathological Interview and Rating of the Social Consequences for Epidemiology.

3-month.

6-month.

12-month.

Indicates agoraphobiapanic disorder.

Fig. 2 graphs for males and females the age of onset distribution of anxiety disorders assessed in a prospective-longitudinal community study (Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology, EDSP) among adolescents and young adults up to age 34 years. No remarkable gender differences in onset patterns occur with 2 exceptions: compared with females, males exhibit a somewhat earlier onset of specific phobia of natural environmental type, and a later onset of GAD.

Prevalence estimates in aggregated age groups (see Fig. 1) also give some convergent, though crude indications for the early onset of a disorder. Prevalence estimates (Table 4) tend to further increase with age among children and adolescents for GAD, social phobia, panic disorder, and agoraphobia, which is not seen with the same magnitude in specific phobia or separation anxiety disorder. Confirming retrospective age of onset information, these data allow one to define “core periods of risk” for the first anxiety disorder onset in childhood for the latter conditions and in adolescence for the former conditions. Similar conclusions emerge from incidence estimates (proportions of new-onset cases between 2 assessment waves among those who were previously not affected) from prospective-longitudinal studies.17,27

Frequency of Anxiety Disorders

Community prevalence estimates (see Table 4) vary slightly due to differences in the studied age groups, assessment instruments (eg, Composite International Diagnostic Interview [CIDI], Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for school-aged children [K-SADS]), information source (eg, self-report, parent/teacher report), method of data aggregation (from multiple information sources or multiple assessment waves), and the diagnostic systems used (ie, DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, ICD-10). In addition, data aggregation from various assessment waves in prospective-longitudinal studies, the number and type of diagnoses included in summary categories (eg, “any” anxiety disorder), and the strictness of application of criteria in generating diagnoses (eg, impairment required or not) are other sources for variance. Differences in prevalence estimates from different countries are unlikely reflective of true regional differences, although it should be noted that most epidemiological studies examine prevalence in Western, industrialized countries that may differ from developing countries or other cultures.

Despite notable variation in prevalence estimates that is likely due to method variance, the lifetime prevalence of “any anxiety disorder” in studies with children or adolescents is about 15% to 20%. In particular, it is noteworthy that the period prevalence estimates, for example 1-year or 6-month rates, are not considerably lower than lifetime estimates. This fact indirectly indicates that anxiety disorders exhibit a persisting course or that high rates of forgetting occur for remitted disorders. The most frequent disorders among children and adolescents are separation anxiety disorder (not included in Table 4), with estimates of 2.8% and 8%,28,29,30 and specific and social phobias, with rates up to around 10% and 7%, respectively. Agoraphobia and panic disorder are low-prevalence conditions in childhood (1% or lower); higher prevalences are found in adolescence (2%–3% for panic and 3%–4% for agoraphobia). Of note, considerable controversy surrounds the diagnosis of agoraphobia. Whereas some epidemiological studies find high rates of agoraphobia without evidence of panic attacks, some suggest that this finding reflects diagnostic inaccuracy in epidemiological studies.31 This issue generally has not been addressed with the same level of rigor in studies of children and adolescents, compared with studies in adults. However, recent findings from the EDSP study among adolescents and young adults suggest that agoraphobia exists as a clinically significant phobic condition independent of panic.21

As mentioned before, it is more difficult to provide precise prevalence estimates of GAD in children and adolescents, because this diagnosis only has been applied to youth in DSM-IV, published in 1994.2 Before 1994, children presenting with worries about multiple events, who typically would receive the DSM-IV diagnosis of GAD, were given the diagnosis of OAD but not GAD. When OAD was subsumed under the diagnosis of GAD in DSM-IV, different criteria were applied to children with multiple worries in DSM-IV, relative to earlier nosologies. This situation complicates attempts to compare earlier to later studies but may explain the lower prevalence rates for GAD than for OAD. Thus, a proportion of children and adolescents who were diagnosed with OAD in the past seem to remain undiagnosed based on current GAD criteria. Similarly, GAD criteria may also identify some children and adolescents who would not meet DSM-III-R criteria for OAD. Data from the EDSP study revealed a cumulative incidence for GAD of 4.3% at age 34 years with relatively few onsets observed in childhood, and the core incidence period being in adolescence and young adulthood.14

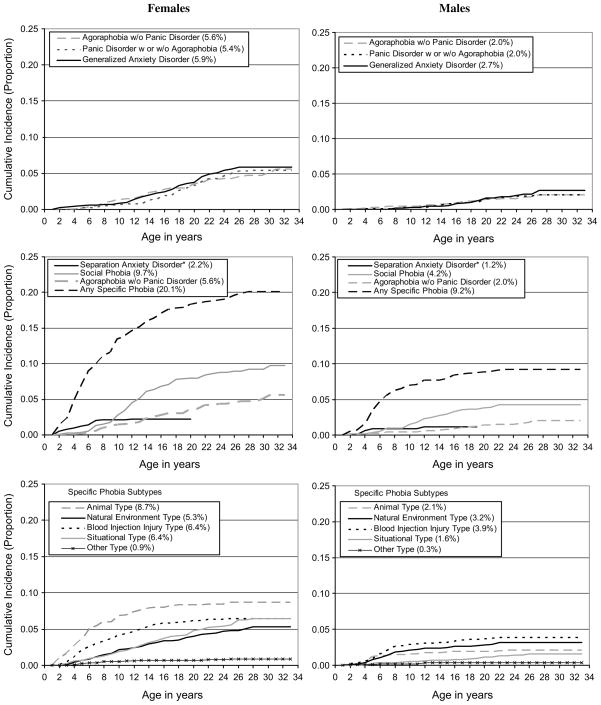

In terms of sex differences, all anxiety disorders more frequently occur among females than among males. Although sex differences may occur as early as childhood they increase with age,32 reaching ratios of 2:1 to 3:1 in adolescence (eg, Refs.28,33). Fig. 3 depicts the cumulative incidence for anxiety disorders among females and males as assessed in the EDSP study. Unlike for panic attacks (compare Ref.21), the sex difference in panic disorder is apparent in cases before the age of 14 but increases further between the ages of 14 and 25 years. The incidence curve for panic disorder reveals a very clear-cut period of increased incidence in females between the ages of 13 and 26 years, whereas males display lower estimates and the period of increased incidence is less pronounced. Agoraphobia revealed a strong and steady incidence increase for females after the age of 6, whereas agoraphobia in males was observed less frequently, with some indication of increased incidence between the ages of 15 and 20 and a leveling off after the age of 25 years. In contrast, a clear sex difference in prevalence was already seen in childhood in the specific phobia animal type (ratio 3:1 by age 10 years).

Fig. 3.

Cumulative Incidence of anxiety disorders (EDSP; N=3021). (Note: Percentages in the legends refer to the estimated cumulative incidence rate at age 33, *age 19 for Separation Anxiety Disorder which was only assessed in a subsample at T1; in phobias impairment was required among subjects aged 18 years or older.)

The choice of appropriate categorical diagnostic thresholds remains a critical issue, giving rise to the consideration of dimensional measures replacing the up to now problematic diagnostic “cutoffs.”34 There is little doubt that the nature of psychopathology is more appropriately conceptualized by dimensional measures and that there is no evidence for a natural point of rarity for most disorders, including anxiety disorders and core anxiety features. In this respect the DSM-IV clinical significance criterion—requiring distress or impairment in social or role functioning—which was introduced to decrease the false-positive problem in psychiatric diagnosis, is particularly problematic.35 Prevalence rates would markedly increase when the clinical significance criterion threshold simply is lowered or omitted (eg, Ref.36). In DSM, such subjects with “subclinical anxiety” would then be classified under “Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention.” As for adults, there is considerable evidence that children and adolescents not meeting the DSM defined clinical significance threshold might still reveal a similar range of adverse correlates as those meeting the threshold (eg, Ref.33). Critical questions therefore are “how can clinical significance or dysfunction be ideally defined” and “what constitutes clinical significance in children versus adolescents versus adults?” Another related concern is that any solution for the distress or impairment criterion that would be applied to anxiety disorders should ideally also be applied to other mental disorders for the reason of consistency.

Similarly, other critical issues relate to symptomatic thresholds required for diagnosis, ie, symptom number, intensity, severity, and temporal thresholds such as duration, persistence, and the clustering of symptoms and criteria in a given time frame.37 Despite given clinical significance (ie, distress or impairment), such conditions would be classified under the nonspecific residual category “Anxiety Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.” With few exceptions, criteria for children resemble those for adults. Particularly for diagnosis with high symptomatic threshold criteria, it may be clinically relevant to lower the threshold for children (eg, shorter duration requirement, fewer symptoms), to detect affected children early and to provide adequate and focused interventions. Such critical issues have raised significant concerns toward the DSM-V as to whether dimensional and developmental aspects should be specified to provide more clinically relevant information to facilitate diagnosis and treatment.34,35,37,38,39

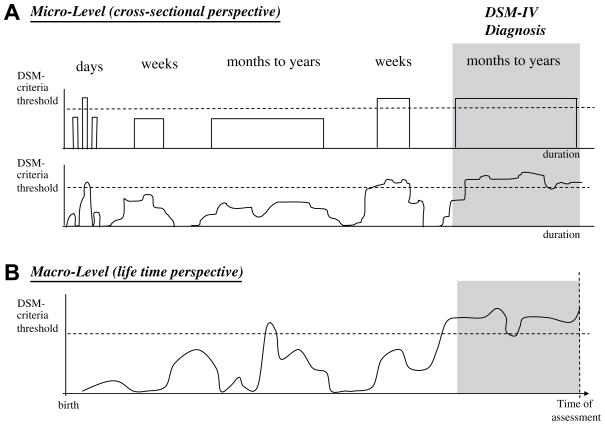

A graphical presentation of the criteria threshold problem is shown in Fig. 4. For each of the anxiety diagnoses, DSM-IV provides a specified diagnostic criteria set including symptom count, time/persistence, and clinical significance requirements reflecting the threshold for diagnosis. Falling short of just one criterion leads to nondiagnosis (or nonspecific classification such as “Anxiety Disorder Not Otherwise Specified” or “Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention”) despite the presence of significant specific anxiety Fig. 4A). Thus, the inclusion pathology ( of dimensional facets in diagnostic systems may facilitate diagnosis and treatment, but it my also complicate the assessment (ie, by use of rating scales or questionnaires, or by the need to develop such scales). Clinicians should also keep in mind that the time point and time frame of assessment may be crucial for diagnosis and diagnostic decisions; aspects also essential for interpreting the epidemiological data adequately. Thus, a lifetime diagnostic approach that describes all psychopathological phenomena in a person up to the age of assessment might yield very different diagnostic data than a cross-sectional approach that covers, for example, a 4-week or a 12-month time frame (compare Fig. 4B); for some diagnoses (like panic/agoraphobia within the anxiety spectrum or bipolar disorders in the mood disorders) a lifetime approach is essential. Variation in assessment might also affect the rates of “subclinical” or “subsyndromal/subthreshold” conditions, simply because a cross-sectional subthreshold condition may have been threshold at a previous point in time, thus more appropriately labeled as partially remitted.

Fig. 4.

The threshold problem in diagnosing children and adolescent. Diagnostic criteria define thresholds for diagnoses by specifying type and number of symptoms, the duration and persistence that the symptoms need to be present, and the clinical significance (A). Due to the current categorical classification system, being short of just one criterion (eg, only 2 instead of 3 symptoms, only 5 months’ instead of 6 months’ duration, only 3 instead of 4 days a week, all symptom criteria met but no distress or impairment reported) leads to non-diagnosis (or nonspecific classification as “Anxiety Disorder Not Otherwise Specified” or “Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention”). The variation of symptoms over time and difficulties in retrospective assessment may negatively affect correct diagnosis. Therefore it is also crucial to take a lifetime approach to diagnosis (B). Mere cross-sectional assessment may lead to erroneous nondiagnosis based on transient alleviation of symptoms.

Natural Course and Longitudinal Outcome

Knowledge on the natural course of anxiety disorders after their first onset is increasing, although several methodological challenges exist. Biases of various sorts are inherent in studies based on clinical samples or in studies using retrospective information on course. Such methods may lead to overestimations of the degree to which anxiety disorders typically seem chronic. Hence, longitudinal studies have clear advantages, particularly when they are based on representative community samples assessed throughout the core high-risk period of first onset and subsequent potential periods of chronic illness. As such, these types of studies represent the method of first choice to study the natural course of anxiety disorders (Fig. 5). Although such studies are costly and time consuming, several studies among youth have become available (Table 5).

Fig. 5.

Assessing the course of anxiety disorders. Several approaches exist to study the course of anxiety disorders. Cross-sectional studies most frequently use retrospective age of onset and age of recency reports to calculate the duration of a condition in years. This approach assumes a continuous disorder course, and may thus overestimate the duration and chronicity because symptom-free intervals are not taken into account. Another indirect measure of disorder chronicity is the proportion of point to lifetime prevalence. The higher the proportion, the higher the chronicity. Because only categorical diagnoses are considered here (no symptomatic improvements below the diagnostic threshold), this may lead to underestimation of chronicity. Overall, cross-sectional studies allow for only crude estimations of course and chronicity of anxiety disorders. Longitudinal studies, in contrast, allow for a more realistic description of the course of a disorder. Taking a prospective approach, the proportion of individuals meeting or not meeting the criteria again at follow-up is frequently used to describe stability and remission. Considering only the full DSM-IV diagnostic level, higher remission rates are possible because improvements below the diagnostic threshold are not taken into account. Thus, the most valid way to describe the course of anxiety disorders is to consider also subthreshold or subsyndromal conditions.

Table 5.

Course of anxiety disorders from childhood and early adolescence to late adolescence and adulthood (follow-up and follow-back studies)

| Disorder of Interest | Study Characteristics | Outcome | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Study (Country) | N | Age at Baseline | FU Duration in Years | Same Disorder | Other Anxiety Disorder | Depressive Disorder | Other Disorders |

| Social phobia | ||||||||

| Stein et al (2001) | EDSP (Germany) | 2548 | 14–24 | 5 | x | x | x | – |

| Merikangas et al (2002) | Zurich study (Switzerland) | 591 | 18–19 | 15 | x | x | x | – |

| Essau, Conradt & Peterman (2002) | BJS (Germany) | 1035 | 12–17 | 1.3 | – | x | – | – |

| Pine et al (1998) | NYCLS (USA) | 776 | 9–18 | 9 | x | x | – | – |

| Last et al (1996) | (USA) | 247 | 5–18 | 34 | x | x | n.e. | – |

| Hale et al (2008) | CONAMORE (Netherlands) | 1318 | 12–16 | 5 | x | n.e. | n.e. | – |

| Gregory et al (2007) | DMHDS (New Zealand) | 1037 | 11 | 21 | x | x | n.e. | – |

| Bittner et al (2007) | GSMS (USA) | 906 | 9/11/13 | 6–10 | – | m | – | ADHD (m) |

| GAD/OAD | ||||||||

| Gregory et al (2007) | DMHDS (New Zealand) | 1037 | 11 | 21 | x | x | n.e. | – |

| Pine et al (1998) | NYCLS (USA) | 776 | 9–18 | 9 | x | x | x | – |

| Bittner et al (2004) | EDSP (Germany) | 2548 | 14–24 | 5 | n.e | n.e | x | – |

| Bittner et al (2007) | GSMS(USA) | 906 | 9/11/13 | 6–10 OAD: | f | – | f | CD (m) |

| – | – | – | 6–10 GAD: | – | – | f | Substance use disorders (f) | |

| Hale et al (2008) | CONAMORE (Netherlands) | 1318 | 12–16 | 5 | f | n.e. | n.e. | – |

| Separation anxiety disorder | ||||||||

| Foley et al (2004) | (USA) | 161 twins | 8–17 | 1.5 | – | x | x | CD, ADHD, ODD |

| Hale et al (2008) | CONAMORE (Netherlands) | 1318 | 12–16 | 5 | – | n.e. | n.e. | – |

| Bittner et al (2007) | GSMS (USA) | 906 | 9/11/13 | 6–10 | f | f | – | |

| Bruckl et al (2007) | EDSP (Germany) | 1090 | 14–24 | 4 | n.e. | x | – | Bipolar disorders, pain disorders, alcohol dependence |

| Pine et al (1998) | NYCLS (USA) | 776 | 9–18 | 9 | n.e. | – | – | – |

| Agoraphobia | ||||||||

| Gregory et al (2007) | DMHDS (New Zealand) | 1037 | 11 | 21 | x | x | n.e. | – |

| Specific phobias | ||||||||

| Gregory et al (2007) | DMHDS (New Zealand) | 1037 | 11 | 21 | x | x | n.e. | – |

| Pine et al (1998) | NYCLS (USA) | 776 | 9–18 | 9 | x | – | – | – |

| Panic disorder | ||||||||

| Gregory et al (2007) | DMHDS (New Zealand) | 1037 | 11 | 21 | x | x | n.e. | – |

| Hale et al (2008) | CONAMORE (Netherlands) | 1318 | 12–16 | 5 | – | n.e. | n.e. | – |

| Any anxiety disorder | ||||||||

| Last et al (1996) | (USA) | 102 | 5–18 | 4 | x | x | x | Behavioral disorders |

| Clark et al (2007) | 1958 British birth cohort | 9727 | birth | 45 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | Internalizing and externalizing disorders |

| Woodward & Fergusson (2001) | CHDS (New Zealand) | 964 | 14–16 | 21 | – | x | x | Substance use disorders |

| Kim-Cohen et al (2003) | DMHDS (New Zealand) | 1037 | birth | 26 | x | x | x | – |

| Feng et al (2008) | WIC (USA) | 290 (boys only) | 7–17 months | 8 | x | x | x | – |

| Lewinsohn et al (1997) | OADP (USA) | 1507 | 13–19 | 1 | n.e. | x | x | Externalizing disorders (substance use, disruptive behaviors) |

Note: References from this table are available from the corresponding author. No associations found. x, positive associations irrespective of gender; f, positive associations only in females; m: positive associations only in males; n.e., not estimated; CD, conduct disorder, ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder.

Study abbreviations: CHDS, Christchurch Health and Development Study; CONAMORE, Conflict and Management of Relationships; DMHDS, Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study; EDSP, Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology; GSMS, Great Smokey Mountain Study; NYCLS, New York Child Longitudinal Study; OADP, Oregon Adolescent Depression Project; WIC, Women Infants Children Program (Pittsburgh).

Anxiety disorders seem to take a chronic course based on findings from clinical adult populations (eg, Refs.40,41) or retrospective studies (eg, Refs.42,43). Prospective epidemiologic follow-up studies among youth from the community only partially support these observations. Thus, on one hand, this work does show that individuals diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, compared with those without, are at statistically increased risk to have the same disorder (eg, Refs.26,28; compare Table 5) or signs and symptoms of the same disorder25,44,45 at later points in time (“homotypic continuity”). Moreover, follow-back analyses also reveal that those with anxiety disorders in adulthood frequently had the same problems earlier in life (eg, Ref.46).

Nevertheless, despite significant longitudinal associations, stability rates (in the form of proportions) of anxiety disorders among youth from the community are overall only low to moderate. For example, in the 15-year prospective multiwave Zurich Cohort study47 a low stability (4%) was found for pure anxiety disorder, defined as GAD or panic disorder. For social phobia no individual met diagnostic criteria continuously at each follow-up assessment, after the disorder had manifested.48 In the prospective-longitudinal EDSP study, in adolescents aged 14 to 17 at baseline the probability of a positive outcome at 2-year follow-up decreased as a function of severity of baseline anxiety diagnostic status.45 However, only 19.7% of threshold baseline anxiety cases met threshold anxiety criteria again at follow-up. For the specific diagnoses, considerable variability in outcome was revealed. Taking stable threshold and subthreshold diagnoses at baseline and at follow-up, panic disorder (44%) and specific phobia (30.1%) were found to be most stable, but even here more than 50% of cases were not completely stable. Other disorders showed higher rates of instability, with agoraphobia (13.4%) and social phobia (15.8%) being particularly unstable. Similar trends emerge from clinical studies with youth as well as in an additional series of epidemiological studies (see for review Ref.49). For example, Last and colleagues13,50 found among children and adolescents (aged 5–19 years) with anxiety disorders that over the 3- to 4-year follow-up, 80% had remitted from the anxiety shown initially. Thus overall, among children and adolescents with an anxiety disorder, there is a considerable degree of fluctuation in diagnostic status of the specific anxiety disorder examined; anxiety disorders have a strong tendency to naturally wax and wane over time, particularly in young age groups.45 It is particularly remarkable that even in disorders that are defined as being chronic, such as GAD, prospective stability rates are only moderate.51

Given the limited homotypic continuity observed in prospective-longitudinal community studies among youth, the question arises as to whether children and adolescents whose specific anxiety disorder seems to improve or remit are completely healthy in their further course of life. The answer is that this is clearly not the case. For example, in the EDSP only 10% of children and adolescents with specific phobias at baseline had no mental disorder at 10-year follow-up (full diagnostic remission); 41% reported the same disorder (strict homotypic continuity) and overall, 73% were diagnosed with any anxiety or depressive disorder at subsequent assessments (heterotypic continuity).52 Similarly, only 13% of baseline social phobia cases were free of any diagnosis during the 10-year follow-up; 35% and 64% reported the same disorder and any anxiety/depression respectively. For GAD and PTSD, even all baseline cases revealed either homotypic or heterotypic continuity. Similar findings emerge from other multiwave, prospective-longitudinal studies.13,28,47,53 Thus, even if for many anxiety cases strict homotypic continuity is moderate, there is a substantial degree of continuity of psychopathology as indicated by the later presence of other anxiety disorders (broad homotypic continuity) or other disorders (heterotypic continuity).

In children and adolescents, there is considerable interanxiety (homotypic) comorbidity with significant association between virtually all specific anxiety disorders, including specific phobia subtypes.54 The number of “pure” anxiety cases decreases with age in favor of patterns with multiple anxiety disorders by late adolescence or early adulthood. The “load” of anxiety seems to contribute to the development of secondary psychopathological complications. For example, Woodward and Fergusson55 examined life course outcomes of adolescents with anxiety disorders in a 21-year longitudinal study of a birth cohort of 1265 New Zealand children (CHDS). There were significant associations between the number of anxiety disorders reported in adolescence and later risks of anxiety disorder, major depression, substance dependence, and suicidal behavior. In this study, a higher number of anxiety disorders was also associated with other adverse developmental outcomes such as educational underachievement and early parenthood.

The development of secondary depression seems to be a particularly frequent and concerning heterotypic outcome of anxiety disorders. Is this a characteristic of anxiety in general rather than an issue of specific anxiety disorders or anxiety features (such as panic, avoidance, accumulation of risk factors)? Or is this related to an overarching anxiety or anxiety-depression liability, possibly through shared etiopathogenetic mechanisms (eg, neurobiology)? Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies examined the association between anxiety disorders and depressive disorders14,55,56,57,58 and concluded that anxiety disorders in general, and also specific types of anxiety disorders (such as phobias, GAD, panic disorder, and so forth) consequently increase the risk for developing a secondary depressive disorder. For example, prospective epidemiological studies found that children and adolescents with specific fears and phobias (especially fear of darkness),59 social phobia,18,60,61 or other types of anxiety disorders (agoraphobia, panic disorder, GAD)14,61 have an increased risk of developing a subsequent depressive disorder. This increased risk for secondary depression seems to be independent of age of onset of anxiety.18 It could further be shown that certain clinical characteristics of anxiety disorders are associated with secondary depression risk. Onset of depression is more likely in individuals with a higher number of anxiety disorders, a more severe impairment of anxiety disorders, and when panic attacks co-occur.18,61 Panic attacks among youth have also been shown to be a significant predictor for a wide range of mental disorders and severe psychopathology, particularly as indicated by the incidence of multiple anxiety disorders and substance use disorders.62

Besides depression, substance abuse or dependence (alcohol or drugs and medication) is a frequently occurring heterotypic problem among subjects with anxiety disorders.57,63,64 It has been suggested that substance use is motivated as a possibility to deal with anxiety symptoms, leading to substance-related problems and disorders over the long term.65 The onset of anxiety disorders precedes that of alcohol and drug disorders at nearly all levels of severity of substance use disorders (use, problems, dependence). Anxiety disorders have been shown to be significant predictors of the subsequent first onset of substance use disorders in cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses.65,66,67 Although substance use disorders are typically associated with so-called externalizing disorders, such as conduct disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or antisocial personality disorder (eg, Ref.68), there is also a strong and significant association with “internalizing” disorders, including anxiety disorders.69 This potentially important pathway has recently been overlooked. Previous research suggests the existence of a second, though less frequent, pathway to substance use disorders originating in early anxiety disorders.70

Higher-Order Psychopathological Factors and Metastructure

The frequent observation of comorbidity even in community-based samples has prompted factor analytical studies of higher-order structures of psychopathology. A 2- to 3-factor solution has been repeatedly found when using a limited group of anxiety, depressive, substance use, and antisocial behavior diagnoses.71,72,73,74,75,76 Anxiety and depressive disorders were consistently loading on an “internalizing” factor that moderately correlates with an “externalizing” factor reflecting substance use and antisocial disorders. The available adult studies frequently revealed 2 additional subfactors for internalizing, namely “fear” (which includes most anxiety disorders) and “anxious-misery” (which includes depressive disorders, but also GAD and PTSD).71,72,73,74,75 Among youth, this 3-factor structure has so far been replicated using only the EDSP sample.77

The finding that all types of anxiety disorders accompany depression is clinically somehow counterintuitive, and therefore several critical concerns have been expressed (see article by Wittchen and colleagues78 in this issue). Given the differences in incidence patterns of specific anxiety and other mental disorders, and the heterogeneity in the phenomenology within and across disorders, it is questionable whether the structure of psychopathology is stable across development and invariant against the inclusion of more diagnoses. From a developmental perspective it seems plausible that higher-order structure changes over time, particularly among youth. Krueger and colleagues76 found a good model fit for the 2-factor internalizing-externalizing solution in a young community sample at 2 time points which, however, were only 3 years apart (at ages 18 and 21 years). A similar type of exploration covering longer time frames and age groups is currently under way.79

Epidemiology clearly shows that anxiety disorders as early-onset conditions are risk factors for the development of depressive and other disorders occurring later in life. Thus, if one aims to derive a clinically more meaningful taxonomy of mental and anxiety disorders, the need to explore other concepts might arise. For example, one approach, taken from somatic illnesses, might be longitudinal “staging models.” Such models would allow one to describe the progression of mental disorders over time from less severe, pure conditions to more complex, severe comorbid stages and thus may have greater potential value for specifying the complexity of developmental patterns of mental disorders.39 From a clinical perspective, such a view might also facilitate the derivation of secondary prevention and staged intervention.

CORRELATES AND RISK FACTORS FOR ANXIETY DISORDERS

Many variables are considered to be risk factors for anxiety disorders. Attempts to definitively demonstrate that the many correlates of anxiety are, in reality, risk factors face considerable methodological hurdles, because it must be demonstrated that the risk factor is actually present before the onset of the anxiety disorder,80 and ideally that the probability of onset of a disorder is related to the severity, frequency, or duration of the risk factor. Thus, cross-sectional studies merely allow generation of initial hypotheses about potential risk factors, based on demonstrations of associations between anxiety disorders and a range of potential variables, such as demographic, neurobiologic, family-genetic, personality, or environmental factors; prospective-longitudinal studies are necessary to show that a factor increases the risk for the onset of an anxiety disorder. This problem, of course, does not apply to factors that are present at birth, such as sex or genotype information. Therefore, in the following sections the authors differentiate between evidence for correlates and risk factors for anxiety disorders. Aspects of specificity of these factors for specific anxiety disorders and for anxiety versus depressive disorders are also considered. The focus is primarily on epidemiological studies among youth, as clinical samples may be subject to various biases related to ascertainment;81 however, such studies are included if no other evidence is available. Findings from epidemiological studies among adults are also included if these allow for the assumption that the variables had an impact in childhood or adolescence.

Demographic Variables

Sex

Female sex consistently emerges as a risk factor for the development of anxiety disorders. Females are about twice as likely as males to develop each of the anxiety disorders (eg, Refs.28,33,82). Sex differences in prevalence, if any, are small in childhood but they increase with age.32

Education

Most epidemiological studies find higher rates of anxiety disorders among subjects with lower education in comparison with subjects with a higher education (eg, Ref.33). It remains unclear to which degree the lower educational performance is a predictor, correlate, or consequence of anxiety. Two adult studies found associations for anxiety but not for depressive disorders.83,84

Financial situation

With few exceptions,85,86 studies consistently find associations between low household income or unsatisfactory financial situations and anxiety disorders (eg, Ref.33). However, results from a quasi-experimental study suggest that these associations may not emerge through a risk factor-disorder association; other more complex relationships may explain the associations seen in cross-sectional research.87

Urbanization

Degree of urbanization (rural/urban) does not typically emerge as a correlate of anxiety disorders.33,85,86

Pathophysiology

Family genetics

Two main approaches have been used to study the familial transmission of anxiety disorders: family studies and twin studies. In family studies, including community studies with linked assessments of familial psychopathology, the familial aggregation of anxiety disorders has been shown to be substantial.88,89,90,91 Overall, children of parents with at least one anxiety disorder have a substantially increased risk of also having an anxiety disorder.92 A particular risk emerges for offspring when both parents are affected88,91 or when the parents suffer from severely impairing, multiple, or early-onset anxiety disorders.93 Because it is known that anxiety disorders are associated with an increased risk of depression, it is not surprising that parental depression was also found to be associated with offspring anxiety,94,95 and that higher rates of depression are also found among offspring of parents with anxiety disorders.91,96 Such cross-disorder associations have prompted investigations into the specificity of the familial transmission of anxiety and other mental disorders. Although findings are mixed, there is some evidence for specificity. For example, in the longitudinal Oregon study of youth, relatives of subjects with anxiety disorder alone more frequently also had an anxiety disorder alone. The same applied to pure depressive disorders. Relatives of adolescents with comorbid anxiety/depression were more likely to show pure anxiety, pure depression, or comorbid anxiety/depression.97 Moffitt and colleagues98 showed in the Dunedin birth cohort that familial depression liability was associated with pure depression but not pure GAD among offspring. In the EDSP study, Beesdo and colleagues14 showed that parental GAD was associated with anxiety disorders alone and comorbid anxiety/depressive disorders among offspring, but not with depressive disorders alone. Thus, a familial transmission of anxiety at least partly independent from depression is suggested by these findings. Furthermore, some specificity seems to exist in the familial transmission of specific anxiety disorders,14,99 consistent with findings from the classic family studies. For example, Fyer and colleagues100 found moderate but specific familial aggregation of simple phobia, social phobia, and panic disorder with agoraphobia in families of subjects who had any of these disorders but no other lifetime anxiety disorder comorbidity.

A meta-analyses of data by Hettema and colleagues90 from family and twin studies of panic disorder, GAD, and phobias in adults showed that all anxiety disorders have a significant familial aggregation. Twin studies can disentangle the genetic from the shared and nonshared environmental contributions in the familial transmission of anxiety disorders. Findings indicate that the estimated genetic heritabilities across the disorders are generally no more than modest, falling in the range of 30% to 40%. The considerable remaining variance in liability can be attributed primarily to individual (nonshared) environmental factors.101 Regarding specificity, twin studies indicate that the genetic liability for specific anxiety disorders overlaps partly.101,102 Furthermore, GAD in particular shares genetic liability with major depression; both disorders, however, can be differentiated based on environmental risk.103,104

Psychobiology

Anxiety disorders can be viewed as reflecting individual differences in neural function. Various physiological systems have been examined in animals and humans to document psychobiological substrates of anxiety. However, it is not clear as to what degree many neurobiological factors relate to anxiety and anxiety processing in general, or whether they are specific correlates of anxiety disorders.

Fear-conditioning experiments in animals have demonstrated that the amygdala is involved in the neural circuit of learning to fear a previously neutral/harmless stimulus.105 Extinction processes have been shown to require communication between the amygdala and the frontal cortex. Other forms of fear develop without prior learning and are regulated by distinct but related neural circuits. Animal research has impressively shown that function of the mature fear circuit, including hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) regulation, also reflects influences during childhood (eg, rearing or stress), but the nature of these influences is likely to be highly complex.49

In humans, brain imaging procedures have been used to study brain function related to anxiety. Besides some other brain structures such as the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex,106,107 amygdala activity has been frequently examined in emotional face-viewing paradigms. Findings are inconsistent, but some studies implicate amygdala hypersensitivity in some forms of anxiety among youth. For example, Thomas and colleagues108 found enhanced amygdala activation during the viewing of evocative face-emotion displays among children with anxiety disorders. More specifically, McClure and colleagues107 found among adolescents with GAD increased amygdala responses to fearful facial expressions, particularly when they rated subjective degrees of internal fear. Thus, attention modulates emotion processing and plays an important role in shaping the function of the adolescent human fear circuit. A recent study examined commonalities and differences in amygdala activity in anxious versus depressed adolescents.109 During fearful-face processing, patients with anxiety and those with major depression both differed in amygdala responses from healthy participants and from each other, but only during a passive viewing condition that did not require a specific attention task. Focusing attention to rate subjectively experienced degrees of fear while viewing fearful faces was associated with similar amygdala hyperactivation in both anxious and depressed adolescents. These data support the view of neural distinctions between depression and anxiety as complex and nuanced, but clearly demonstrable. More work is needed to understand commonalities and differences in neural circuits of the specific anxiety disorders.

Few data are available regarding the question as to whether functional abnormalities occur as correlate of or vulnerability to anxiety disorders. One study compared amygdala activity in adults classified as inhibited or not inhibited in childhood,110 and found enhanced amygdala activity in the formerly inhibited individuals, implicating amygdala function in risk for anxiety. Another study found that perturbations in amygdala function are evident in adolescents temperamentally at risk for anxiety, and that attention state alters the underlying pattern of neural processing, potentially mediating the observed behavioral patterns across development.111 More such work is needed to understand to what degree findings of functional neural abnormalities relate to altered processing of anxiety-related cues or reflect the consequences of anxiety disorders, or whether these abnormalities pose a risk for a subsequent anxiety disorder onset. Of particular clinical interest, however, is the finding that brain function abnormalities decrease with successful pharmacological or cognitive-behavioral treatment (eg, Ref.112).

Temperament and Personality

Temperamental and personality trait vulnerabilities such as Eysenck’s neuroticism, Gray’s trait-anxiety, or Kagan’s behavioral inhibition, which are likely to be overlapping constructs, are consistently viewed to play an important role in anxiety disorders. In fact one might see these constructs as a precursor condition to the occurrence of prototypical anxiety disorders. The tripartite model conceptualizes general distress or negative affectivity as general higher-order vulnerability factor for anxiety and depression, whereas low positive affectivity is specific to depression, and physiological hyperarousal is specific to anxiety.113,114 Similarly, in a hierarchical model115 negative affectivity is the higher-order factor relevant for anxiety and depression, but on a lower level each anxiety disorder contains an additional specific component.

Several studies support the tripartite and the hierarchical models for anxiety and depression symptoms (eg, Refs.116,117,118). Twin studies consistently show high correlations between neuroticism and anxiety and depression, as well as their co-occurrence.119,120 It is estimated that about 50% of the genetic correlations between these disorders derives from the genetic factor for neuroticism. Epidemiological studies are generally in support of these findings, with few indications of specificity between anxiety and depression outcomes.121,122

The temperamental concept of behavioral inhibition reflects the consistent tendency to display fear and withdrawal in unfamiliar situations.123 Behavioral inhibition is at least moderately stable, detectable early in life, and under some genetic control.124,125 Children with behavioral inhibition are shy with strangers and fearful in unfamiliar situations.126 With few exceptions,127,128 behavioral inhibition was shown to be a risk factor for the development of anxiety disorders (eg, Refs.126,129,130). There are also indications for specificity in this association within the anxiety disorders (strong associations particularly to social phobia)126,131,132 and in differentiation to depression.14,126

Environmental Factors

Parenting style

Despite the existence of several clinical studies, there are only a few epidemiological studies examining the question as to whether parenting style is an important risk factor for anxiety disorders (for an overview, see Ref.133). In the EDSP study among adolescents, parental overprotection and parental rejection were significantly associated with increased rates of social phobia in offspring.89,99 Other analyses from this study indicate that overprotection increases the risk for anxiety disorders but not “pure” depressive disorders, whereas depressive disorders show associations to rejection.14 Kendler and colleagues134 examined 1033 female adult twin pairs, and measured 3 dimensions of parenting (coldness, protectiveness, authoritarianism). High levels of coldness and authoritarianism in parents were modestly associated with increased risk for nearly all disorders. Nevertheless, the impact of protectiveness was more variable. Whereas phobia, GAD, major depression, and panic disorder were significantly associated with protectiveness, bulimia, drug abuse, and alcohol dependence showed no significant associations with this particular parenting dimension. In a clinical sample, Merikangas and colleagues88 did not find an association between family climate or rearing style and anxiety disorders in offspring of parents with anxiety or substance use disorder. In a prospective-longitudinal design, parent-adolescent disagreements were found to indirectly increase the risk for the onset of anxiety and depressive disorders through their direct association with high symptom levels.135 Considerable other work finds similar relationships, though using somewhat different procedures.136,137

Social learning mechanisms,138 such as parental modeling of anxious or avoidance behavior, or parental attitudes and actions139,140,141,142 are discussed as mediating mechanisms of these relationships, reflecting the aspects of the environment in these family-environmental factors. However, recent work suggests that such factors also reflect the influence of genetics, through gene-environment interactions and correlations.143

Childhood adversities

Most epidemiological studies find associations between adverse experiences in childhood (eg, loss of parents, parental divorce, physical and sexual abuse) and almost all mental disorders, including anxiety disorders. Kessler and colleagues144 found associations between retrospectively reported childhood adversities, including loss events (eg, parental divorce), parental psychopathologies (eg, maternal depression), interpersonal traumas (eg, rape), and subsequent onset of DSM-III-R disorders in a large United States community study of adults. These adversities were consistently associated with the onset of anxiety disorders, mood disorders, addictive disorders, and acting out disorders. Also, a history of neglect or abuse was a strong predictor of psychiatric morbidity (ie, anxiety disorders, depression, substance use disorders) in the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS).145 In the New Zealand CHDS study, individuals who reported childhood sexual abuse had higher rates of major depression, anxiety disorder, conduct disorder, substance use disorder, and suicidal behavior than those not reporting sexual abuse.146 Furthermore, there were consistent relationships between the extent of childhood sexual abuse and the risk of mental disorders.

It remains an open question whether the nonspecificity of the findings mainly emerges because of the frequent comorbidity among disorders. Moffitt and colleagues98 found in the Dunedin birth cohort study that childhood maltreatment was associated with “pure” GAD and “pure” major depression, indicating nonspecificity. In the EDSP, however, childhood separation events were associated only with “pure” anxiety and comorbid anxiety/depression, but not with “pure” depression.14