We described recently how immunosuppression with FK 506 alone markedly prolonged the survival in rats of non arterialized orthotopic hamster liver xenografts, but not heart xenografts revascularized in the abdominal cavity (1). We report here that addition of splenectomy to FK 506 prolonged survival of heart grafts from a mean of 3 days in untreated controls (n=6) to >100 days (7 of 7), permitting us to determine with both organs if the donor dendritic cells were replaced. Male LVG hamsters (120-150 g) and male Lewis rats (240-280 g) were used as donors and recipients, respectively. The transplant procedures were performed under methoxyflurane anesthesia in the same way as described before (1), except that the heart recipients underwent contemporaneous splenectomy.

Liver recipients were given 1 mg/kg/day intramuscular FK 506 (Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Co., Osaka, Japan) for 30 days and 0.5 mg/kg every other day for another 70 days, terminating treatment on day 100. The splenectomized heart recipients were treated with 2 mg/kg/day FK 506 for 30 days, and there-after were treated the same as the liver recipients up to 100 days.

Survival of the liver recipients was prolonged with FK 506 from 7.0±0.5 days in untreated controls (n=8) to 66.7±57.9 days (n=10), with 3 of the recipients surviving more than 100 days. The main cause of delayed death under treatment was obstruction of the bile duct, usually with minor histopathologic findings of cellular rejection. After FK 506 was withdrawn at 100 days. the 3 surviving animals remained clinically well for 2 months, at which time liver biopsies showed cellular infiltrates. One animal died alter biopsy, but the other 2 lived for an additional 84 and 109 days without therapy before their xenografts were slowly rejected. The 7 heart recipients who survived for 100 days are alive with beating hearts after a further 15-20 days off therapy.

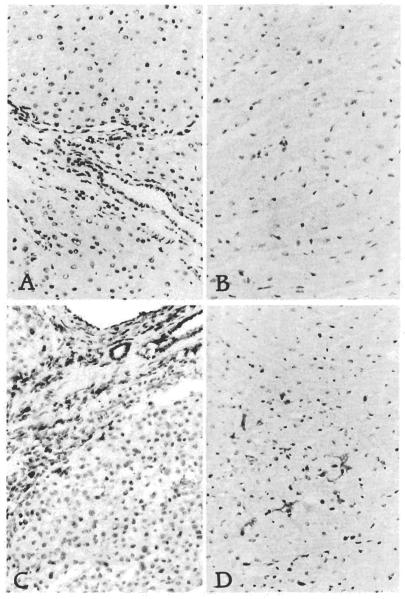

Liver xenografts were sampled during treatment at 3 (n=3), 30 (n=3), and 60 (n=3) days and beyond the 100-day treatment period (n=3), whereas cardiac xenografts were examined only on post-transplant day 100 (n=3). Tissues were studied with a previously described standard 3-step avidin-biotin complex (ABC) immunoperoxidase technique using the L-21-6 mouse mAb that recognizes class II antigens in Lewis rats (2, 3) and a variety for other inbred rat strains. No staining for L-21-6 was detected in normal hamster liver, heart, or spleen (3 samples each).

In contrast, by day 3 after liver transplantation, occasional spindled and round sinusoidal and portal cells were L-21-6 positive in all samples. After transplantation, bile ducts, hepatocytes, and vascular endothelial cells remained L-21-6 negative (donor type) throughout (Fig. 1A). From day 30 onward, whether the grafts were histologically normal or contained a mononuclear portal infiltrate, most of the portal inflammatory cells, sinusoidal Kupffer cells, dendritic-shaped cells in the triads, and spindle cells beneath hepatic venules and in the capsule were L-21-6+ and thus of recipient origin. Although most of the infiltrative cell populations were L-21-6+, 3 distinct cell subgroups could be distinguished based on location, immunophenotype, and morphology. L-21-6+/ED2+ cells with abundant cytoplasm located in the sinusoids and at the edge of the triads were most likely of macrophage lineage. L-21-6+/OX33+ small round cells in the triads, arranged in nodules, were probably B cells. Finally, L-21-6+/ED2− dendritic shaped cells present in the center of the triads, often near bile ducts, are most likely dendritic cells.

Figure 1.

Hamster liver (A) and heart (B) in native state and 100 days after transplantation to rats (C and D). Immunoperoxidase stain with L-21-6 mAb and hematoxylin counterstain. Original magnifications: top, x300; bottom, x120.

By day 100, the number of L-21-6+ cells in the portal tracts had reached their maximum. Cardiac xenografts sampled on day 100 also had intensely L-21-6+ (recipient origin) spindle-shaped dendritic reticulum cells scattered throughout the interstitium and around arteries (Fig. 1B). These observations were constant in all liver and heart samples with minimum variability.

Cell replacement in the liver allografts was originally observed by K. A. Porter in human liver allografts many years ago (4, 5) and was noted recently by Yamaguchi et al. (6) in a hamster to rat hepatic xenograft that had survived for 83 days. The findings in the liver and heart xenografts reported here support the contention that dendritic cell repopulation is generic to the acceptance of all grafts (7). It is noteworthy that repopulated hepatic and cardiac xenografts had prolonged survival after stopping treatment before they were slowly rejected.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Research Grants from the Veterans Administration and Project Grant No. DK 29961 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

REFERENCES

- 1.Valdivia LA, Fung JJ, Demetris AJ, Starzl TE. Differential survival of hamster-to-rat liver and cardiac xenografts under FK 506 immunosuppression. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:3269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demetris AJ, Qian S, Sun H, et al. Early events in liver allograft rejection: delineation of sites of simultaneous intragraft and recipient lymphoid tissue sensitization. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:609. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murase N, Demetria AJ, Matsuzaki T, et al. Long survival in rats after multivisceral versus isolated small bowel allotransplantation under FK 506. Surgery. 1991;110:87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porter KA. Pathology of the orthotopic homograft and heterograft. In: Starz TE, editor. Experience in hepatic transplantation. WB Saunders Company; Philadelphia, PA: 1969. p. 464. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kashiwagi N, Porter KA, Penn I, Brettschneider L, Starzl TE. Studies of homograft sex and of gamma globulin phenotypes after orthotopic homotransplantation of the human liver. Surg Forum. 1969;20:374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamaguchi Y, Halperin EC, Mori K, et al. Macrophage migration into hepatic xenografts in the hamster-to-rat combination. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starzl TE, Demetris AJ, Murase N, Ildstad S, Ricordi C. Cell migration, chimerism, and graft acceptance. Lancet. 1992;339:1579. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91840-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]