Abstract

BBR3610 is a polynuclear platinum compound, in which two platinums are linked by a spermine-like linker, and studies in a variety of cancers, including glioma, have shown that it is more potent than conventional platinums and works by different means. Identifying the mechanism of action of BBR3610 would help in developing the drug further for clinical use. Previous work showed that BBR3610 does not induce immediate apoptosis but results in an early G2/M arrest. Here, we report that BBR3610 induces early autophagy in glioma cells. Increased autophagy was also seen in intracranial xenografts treated with BBR3610. Interestingly, upon attenuation of autophagy by RNAi-mediated knockdown of ATG5 or ATG6/BECN1, no change in cell viability was observed, suggesting that the autophagy is neither an effective protection against BBR3610 nor an important part of the mechanism by which BBR3610 reduces glioma cell viability. This prompted a multimodal analysis of 4 cell lines over 2 weeks posttreatment with BBR3610, which showed that the G2/M arrest occurred early and apoptosis occurred later in all cell lines. The cells that survived entered a senescent state associated with mitotic catastrophe in 2 of the cell lines. Together, our data show that the response to treatment with a single agent is complex and changes over time.

Keywords: apoptosis, autophagy, cell cycle, glioma, platinum compounds

Many promising new compounds that target individual signal transduction pathways are under investigation in the laboratory and the clinic. However, in several instances, the very specificity of these agents has reduced their effectiveness in a complex and varied patient population, meaning the rationale for studying the drugs, whose mode of action is not predicated on the presence of a particular molecular target or a specific mutation, remains strong.1,2 Conventional platinum compounds, including cisplatin and oxaliplatin, show a lack of efficacy and problems with delivery to the tumor and so are not widely used in the treatment of brain cancer. We are, therefore, interested in polynuclear platinum compounds, which are structurally distinct from cisplatin and whose clinical profile and mechanism of action are different from the established platinum compounds.3–6

The prototype polynuclear platinum, trinuclear BBR3464, was shown to be effective against cells with inherent or acquired resistance to cisplatin, including glioma cells,6,7 suggesting that there are important differences in their mode of action. DNA mismatch repair status, which has been implicated as a major determinant of cisplatin sensitivity, played no role in the response to BBR3464.5 Another indication that polynuclear platinum agents are biologically distinct comes from the analysis of the 60-cell line panel from the NCI, which showed that BBR3464 was more potent than cisplatin and revealed that the pattern of response did not match that of any other tested drug, including other platinum compounds.8

More recently, we have investigated newer members of the polynuclear platinum family, which have not yet been tested in the clinic: polynuclear complexes with polyamine linkers based on spermidine (BBR3571) and spermine linkers (BBR3610).3 These second-generation polynuclear compounds have DNA-binding profiles and cellular responses that are very similar to BBR3464 and show cross-resistance with BBR3464, suggesting common elements in their mechanism of action.9–11 BBR3610, which has the greatest potency on glioma cells in culture and in xenograft models, induced predominantly G2/M arrest in the absence of apoptosis in the first day after treatment.3 Interestingly, this response was mediated by ERK activation, just as the rapid induction of apoptosis by cisplatin, suggesting that although the cellular response to polynuclear platinum compounds is distinct from cisplatin, they make use of some of the same signal transduction pathways.

The recognition that autophagy is a common occurrence when cancer cells are treated with agents as varied as the hormone inhibitor tamoxifen, the signal transduction inhibitor rapamycin and the cytotoxic temozolomide (reviewed in Kondo et al.)12 prompted the current study. Our results show that autophagy is induced early in glioma cells at concentrations of BBR3610 at or below the IC90 for colony formation, and that it is induced in gliomas in vivo when they are treated with BBR3610. However, suppression of autophagy by knockdown of ATG5 or ATG6/BECN1 failed to either rescue cells from death or divert them to another mode of cell death, suggesting that the observed autophagy was neither a primary part of the mechanism of BBR3610 nor a protective response by the cells. A comprehensive analysis of cell response to BBR3610 showed that autophagy was early and apoptosis was late for the majority of cells, regardless of p53, INK4A, or PTEN status. Cells that survived, in 2 of the 4 cell lines tested, entered senescence which was associated with mitotic catastrophe. Therefore, the response of glioma cells to BBR3610 changes from an initial G2/M arrest and autophagy to apoptosis, and if cells survive ends commonly in senescence and mitotic arrest.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Drug Treatment

Human malignant glioma cell lines U87-MG and LN229 were originally from American Type Culture Collection. Human malignant glioma cell lines LN428 and LNZ308 were originally a kind gift from Dr N. de Tribolet (University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland). Glioma cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (Cellgro, Mediatech Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin; all cells were grown in a 7% CO2 humidified incubator. BBR3610 was prepared in water, stored at −80°C until use. Cisplatin (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared in dimethylsulfoxide with the final concentration of the vehicle being kept at 0.1% or below in all experiments. BBR3610 was most commonly used at 8 nM, the IC90 concentration as measured by a clonogenic assay, or at 80 nM, 10 times the IC90 concentration.3 Clonogenic assays are the most stringent cell culture-based test of drug response, as they require a cell to replate and form a colony in low-density culture after drug treatment. However, in denser cultures, such as the ones required for other types of viability assay, biochemical or cell cycle analyses, the IC90 as measured by a clonogenic assay has a lower impact,3 and higher concentrations are used. Relevance to in vivo achievable doses is a key consideration, and our in vivo achievable doses are likely to be a maximum of 150 nm or 1.5 µM, depending on whether the total fluid volume13 or blood volume14 or of a mouse is used in the calculation. Cells used here were obtained from the stocks of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, San Diego Branch, in 1997 and have been maintained in the Bogler laboratory. As of 2008, they are routinely fingerprinted for identity using a PCR-based analysis (GenomeLab Human STR Primer set from Beckman Coulter) which interrogates a set of 12 short tandem repeats (Supplementary Material, Table S1).

Quantification of Acidic Vesicular Organelles with Acridine Orange Staining

Autophagy is characterized by the development of acidic vesicular organelles (AVO). To measure the extent of AVO formation, we performed staining with acridine orange followed by FACS analysis as described previously.15 In short, cells were treated with acridine orange (Sigma Aldrich) at 10 mg/mL concentration for 15 minutes at 37°C, washed with PBS, and trypsinized and kept in a PBS buffer with FBS (10:1). FACS analysis was performed by FACScan from Becton Dickinson using CellQuest software.

Assessment of the Involvement of Microtubule-Associated Protein Light Chain 3

Light chain 3 (LC3) is a mammalian homologue of yeast ATG8 that is recruited to the autophagosome membrane during autophagy, which makes LC3 a marker of autophagy.16 LNZ308 cells were transiently transfected with an expression vector encoding green fluorescent protein-linked LC-3 (GFP-LC3) using Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Roche) for 24 hours, and treated with BBR3610 or rapamycin and observed under a fluorescence microscope to determine the proportion of cells expressing GFP-LC3 dots (≥10 dots/cell) as described before.15 GFP-LC3 expression vector was kindly supplied by Dr T. Yoshimori and Dr N. Mizushima (Osaka University, Suita, Japan, and Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell Cycle Analysis

LNZ308 cells with or without treatment were trypsinized, fixed with 70% ethanol in PBS, and stained with propidium iodide 25 µg/mL (Sigma) in the presence of RNAse A (100 µg/mL) in PBS for 60 minutes at 37°C, and analyzed for DNA content by using the FACScan (Becton Dickinson) as previously described.3 Data were analyzed by Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson).

Western Blots

To make lysates, cells were first washed with PBS twice and then scraped into a lysis buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl [pH 8], 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Na deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, aprotinin and leupeptin, 1 µg/mL each). The cells were then lysed with a 23 G needle, incubated on ice for 30 minutes, and the lysates were cleared by centrifugation. Protein concentration was measured with the BCA protein estimation kit (Pierce Biotechnology). Samples were stored at −20°C until use. Samples were run on precast gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories), transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (GE Waters & Process Technology), blocked with 5% fat-free milk, and incubated in the primary antibody at the indicated dilutions overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed with Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 3 times, each for 15 minutes. Secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:2500) developed with SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology), and exposed to film. The following antibodies were used: LC3B (1:3000, Novus Biologicals, Littleton Co.), anti-ATG5 (1:1000 kindly supplied by Dr N. Mizushima), anti-poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-BECN1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), and b-actin (1:25 000, from Sigma).

Animal Experiment

All the animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of MD Anderson Cancer Center. To see if BBR3610 induces autophagy in vivo, tumors were implanted intracranially in nude mice, and the mice were treated with either BBR3610 or cisplatin, or left untreated. Nude mice were injected with 5 × 105 cells in serum-free DMEM media intracranially using a guide screw, and tumors were allowed to grow for 14 days and then treated with either BBR3610 0.1 mg/kg i.v. or cisplatin 6 mg/kg i.v. (for justification of doses, see Billecke et al.3). Five days later, animals were sacrificed and tumors were harvested, washed with PBS, and snap frozen and stored at −80°C until use. Lysates were made from the tumor by homogenizing the tumor tissue in the lysis buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl [pH 8], 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Na deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, aprotinin and leupeptin, 1 µg/mL each) using a glass homogenizer on ice. Lysates were further processed for western blotting, as described above.

Small Interfering RNA

To specifically inhibit the expression of ATG5 or BECN1 proteins, cells were transfected with small interfering RNA (siRNA) directed against ATG5 or BECN1, purchased from Dharmacon. The sequence of siRNA targeting ATG5 and BECN1 was as follows: -CAACTTGTTTCACGCTATA and -GGACAGUUUGGCACAAUCA, respectively. These siRNAs (1 µg) were transfected using Nucleofector and a Cell Line Nucleofector Kit T (Amaxa Biosystems) or lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Cell Viability Assay

Cells were seeded at 5 × 102 cells per well in 96-well flat-bottomed plates, and allowed to attach overnight at 37°C. Subsequently, DMEM with 10% FBS containing vehicle or reagents was added to the medium in each well, and cells were further incubated at 37°C for the indicated duration. The number of viable cells was estimated using WST-1 (Roche Diagnostics Gmbh). The absorbance was measured at 450 nm. All the evaluations were done in the range of absorbance that correlates linearly with the cell number (data not shown). Percent viability was expressed as (Asample−Ablank)/(Acontrol−Ablank), where A is the absorbance. For the cells treated with reagents, the vehicle-treated cells were used as the control. Blank was for WST-1 added to medium.

Cellular Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase Assay

Cellular senescence was examined by detecting the activity of β-galactosidase. Briefly, tumor cells were seeded in a 24-well plate (Corning), treated with reagents for the indicated duration, and then stained using Senescence β-Galactosidase Staining Kit (Cell Signaling Technology) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Cells were examined using a light microscope. No signal was detected in LNZ308 and LN428 cultures. For U87-MG and LN229 cultures, the percentage of stained cells was estimated by counting random fields.

Giemsa Staining

Cells were seeded in 12-well flat-bottomed plates (Corning), and allowed to attach overnight at 37°C. Subsequently, cells were treated with reagents for the indicated duration. Cells were fixed with 70% (v/v) methanol, stained with Giemsa's stain, and examined using a light microscope. Large cells with multiple nuclei, micronucleation, or lobulated nuclei were counted as mitotic catastrophe cells.

Statistical Analysis

An unpaired Student's t-test (two-tailed) was used for comparison between two groups. Differences were considered statistically significant when P-value was <.05.

Results

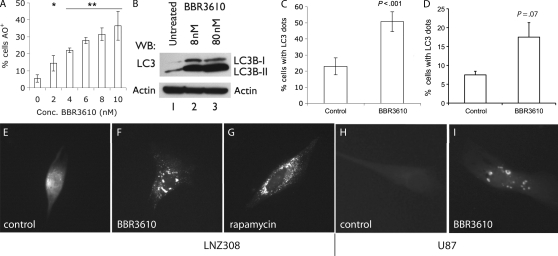

A rapid approach to testing whether autophagy may be occurring is to measure cellular acidification using acridine orange staining and FACS analysis.15 An absence of acidification would rule out autophagy, whereas its presence would be a rationale for further investigations. Treating LNZ308 glioma cells with 8 nM BBR3610, the IC90 concentration in a clonogenic assay,3 led to the acidification of cells over time, with near-maximal levels reached by day 4 (data not shown). At this time point, a dose–response curve revealed statistically significant levels of acridine orange staining at 2 nM BBR3610 and above, suggesting that vesicle acidification occurred at treatments well below the IC90 for clonogenicity (Fig. 1A), and prompting further analysis of whether autophagy was induced by this compound.

Fig. 1.

BBR3610 induces autophagy in glioma cells. (A) LNZ308 cells were plated in 6-well dishes, treated with different concentrations of BBR3610 and allowed to grow for 4 days and then stained with AO and analyzed by FACS to determine the percentage of cells that were AO+. Data from three independent experiments were combined and are represented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis using a t-test showed significant difference between the control and cells treated with 2 nM BBR3610 (*P < .05) and higher doses (**P < .005). (B) Western blot analysis of LC3B in LNZ308 cells treated with 8 and 80 nM of BBR3610 after 5 days showed a marked increase in the LC3B-II form, indicating autophagosome formation (one representative of three experiments shown). (C, E–G) LNZ308 cells or (D, H, and I) U87 cells were transfected with GFP-LC3 plasmid and were either untreated or treated with either 80 nM BBR3610 or 100 mM rapamycin and observed under the microscope 5 days later. When cells showing a dot-like pattern (≥10 dots/cell) were counted, a significant increase was observed in BBR3610 cells when compared with the untreated control (C: P < .001; data combined from 3 experiments; D: P = .07; data combined from 2 experiments). Untreated cells showed a diffuse distribution of LC3 (E and H) while those treated with either BBR3610 (F and I) or rapamycin (G) showed a punctate pattern of “LC3-dots”, confirming formation of autophagosomes.

A more specific measure of autophagy can be obtained by the analysis of microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3B).17 LC3B exists in a cytosolic form, LC3B-I, which is then processed and conjugated to lipids on autophagosome membranes to yield a shorter form, LC3B-II.16 As LC3B-II remains associated with the autophagosomes until they form autolysosomes, the relative amount of this form is a good measure of the number of autophagosomes present. Immunoblot showed that a robust induction of the LC3B-II form occurred when LNZ308 cells were treated with BBR3610 at the IC90 or 10 times the IC90 concentration (Fig. 1B). Another reliable measure of autophagy comes from monitoring the accumulation of intracellular concentrations of an LC3-GFP fusion protein into the so-called LC3 dots, which is a consequence of LC3's participation in the formation of the autophagosome.15 Treatment of LNZ308 or U87 glioma cells transfected with an LC3-GFP encoding plasmid with BBR3610 led to a doubling in the number of cells that had LC3 dots (Fig. 1C and D), which resembled those obtained with the rapamycin positive control (Fig. 1E–I).

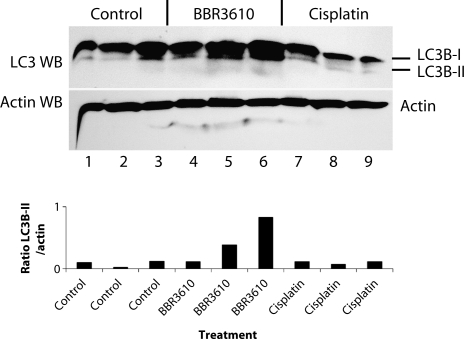

Cell culture conditions can induce behaviors that are not found in vivo, and these would likely not be relevant to the clinical situation. Therefore, we investigated whether autophagy could be observed in glioma cells in vivo, after treatment with BBR3610. We established intracranial U87 gliomas in nude mice using a guide screw system that has been described previously.18 Animals were then treated with a single i.v. dose of BBR3610 (0.1 mg/kg) or cisplatin (6 mg/kg), and the tumors were collected 5 days later for western blot analysis of LC3B processing. We analyzed 3 independent tumors for each group. Although all samples showed evidence of the lower LC3B-II band, probably because the nutrient limitation in the tumor induces cellular stress resulting in autophagy, the tumors treated with BBR3610 showed a stronger signal for LC3B-II overall (Fig. 2). The tumor in Lane 6 (Fig. 2) showed a particularly strong LC3B-II signal, and the tumors in Lanes 4 and 5 had LC3B-II bands that were as strong or stronger than the signals obtained for the control or cisplatin-treated tumors, as indicated by the quantification of the LC3B-II bands and normalization to the actin bands (Fig. 2, lower panel). This suggests that autophagy is part of the in vivo response to BBR3610.

Fig. 2.

BBR3610 induces autophagy in gliomas in vivo. Nude mice were implanted intracranially with 5 × 105 U87MG cells using a guide screw, and tumors were allowed to grow for 14 days. Animals were then treated with either BBR3610 (0.1 mg/kg) or cisplatin (6 mg/kg) i.v., and tumors were harvested 5 days later. Western blot for LC3B was done, which shows increased LC3B-II band (lower band) in tumors from the BBR3610-treated group when compared with the control untreated and cisplatin-treated groups. Quantification of the western blot is shown in a graph form in the lower panel as a ratio of the LC3B-II band intensity over the actin band intensity. A single experiment was done. The animal in Lane 4 had a survival time (30 days) closer to that of control than BBR3610 treated (23 vs 41.5 days),3 suggesting that in this instance treatment with BBR3610 was not effective.

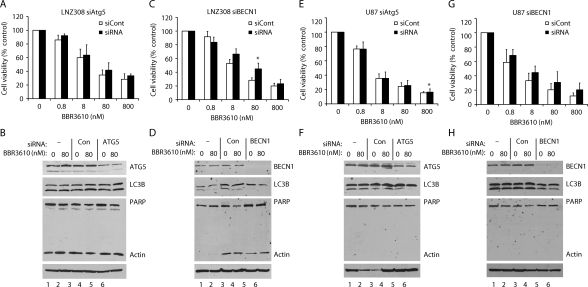

It has been suggested that cancer cells may undergo protective autophagy when treated with anticancer therapy, and that when autophagy is suppressed, the result is significantly reduced levels of cell viability.12 To determine whether this was the role of the autophagy induced by BBR3610, we inhibited autophagy by knocking down expression of the ATG5 gene, the product of which is required for the vesicle elongation stage, or of the ATG6/BECN1 gene, which is involved in vesicle nucleation.19,20 Treatment of cells with siRNA targeting ATG5 did not protect either LNZ308 or U87 cells from the loss of viability that was induced by a broad range of concentrations of BBR3610 (Fig. 3A and E), even though it reduced levels of the ATG5 proteins and inhibited autophagy, as measured by western blot (Fig. 3B and F). The knockdown of ATG6/BECN1 was more complete and also blunted the autophagy induced by BBR3610 in both cell lines (Fig. 3D and H), and similar to the ATG5 knockdown did not protect the cells from loss of viability (Fig. 3C and G). Only in two instances did knockdown of BECN1 or ATG5 statistically increase viability (Fig. 3C and E; marked by an asterisk), but in both cases, the difference was modest in biological terms. These data suggest that autophagy is induced by BBR3610 soon after treatment, but is not a major determinant of long-term cell viability, and so may not play a pronounced protective role. Furthermore, it suggests that autophagy may not be the entire response of cells to polynuclear platinums. This prompted us to look more broadly at cell behavior after exposure to BBR3610 by bringing multiple modes of analysis to bear over a 2-week time course in four different cell lines.

Fig. 3.

Knockdown of ATG5 or BECN1 blocks autophagy formation, but does not significantly effect apoptosis. LNZ308 or U87-MG cells were transfected with 100–200 nmol/L siRNAs using lipofectamine 2000 reagent. After incubated overnight, cells were harvested and seeded in 96-well plates for viability assay (A, C, E, and G) or 60 mm dishes for western blot (B, D, F, and H). (A, C, E, and G) Cells were treated with indicated concentrations of BBR3610 for 7 days and subjected to viability assay using WST-1. Viability of cells treated with vehicle was expressed as 100%. Data shown are means of 2 independent experiments done in duplicate. Error bars are SD. *P < .05. (B, D, F, and H) Cells were treated with indicated concentrations of BBR3610 for 2 days, and extracted proteins were subjected to western blot for detection of LC3B-II, full-length PARP, and ATG5 or BECN1. Actin was detected as a loading control.

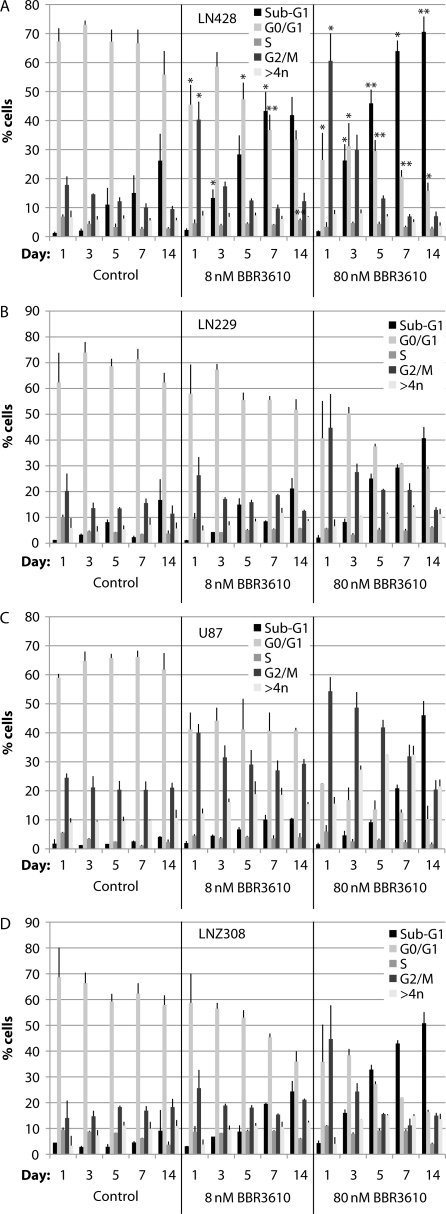

We chose to work with 4 glioma cell lines reflecting different p53, PTEN, and INK4A status: LNZ308 (p53 null; PTEN mutated; INK4A wild-type); U87 (p53 wild-type; PTEN mutated; INK4A null); LN229 (p53 mutated; PTEN wild-type; INK4A null), and LN428 (p53 mutated; PTEN wild-type; INK4A null).21 We combined cell cycle analysis with western blot analysis of apoptosis and autophagy and measurements of senescence and mitotic catastrophe and measured each at 5 time points over 2 weeks posttreatment. We treated cells at both the IC90 concentration of 8 nM and at 10 times that concentration. The overall pattern of response emerged most clearly in the cell cycle analysis, which showed an early induction of the G2/M arrest followed by a steady increase in sub-G1 cells over time (Fig. 4). Both the magnitude of the G2/M arrest and extent of transition to apoptosis were more marked at the higher concentration of BBR3610 (Fig. 4, right-hand panels) and in LN428 and LNZ308 cells (Fig. 4A and D). In all cases, the G2/M arrest was maximal at 1 day, and the proportion of cells in this compartment had returned to control levels by day 3 in LN428, LN229, and LNZ308 cells treated with 8 nM BBR3610, and by day 5 in these lines when treated with 80 nM drug (Fig. 4A, B, and D). U87 cells showed a more prolonged increase in cells in the G2/M arrest, lasting the entire 2 weeks in 8-nM treated cultures, and 7 days in 80-nM treated cultures (Fig. 4C). Correspondingly, fewer U87 cells entered the sub-G1, and presumptively apoptotic, compartment than in the other lines, although at 80 nM BBR3610 and 14 days, this exceeded 40%. Therefore, in general, a period of the G2/M arrest was followed by transition to the sub-G1 compartment in all the cells examined.

Fig. 4.

Cell cycle analysis of glioma cells treated with BBR3610. Cells were treated with a vehicle (control) or indicated concentrations of BBR3610 for indicated duration, and then DNA content in cells was analyzed by flow cytometry using propidium iodide. Data are means of 2 independent experiments. Error bars are SD. *P < .05 compared with the control.

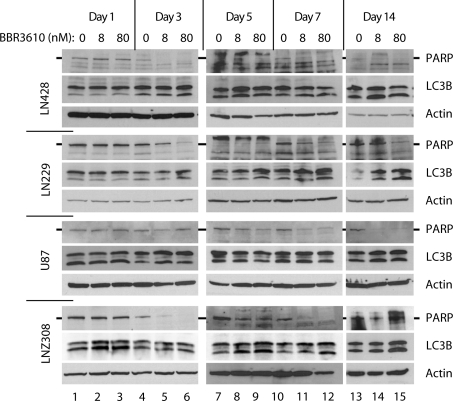

To investigate the cellular response with molecular markers, we performed western blots for PARP cleavage as a measure of apoptosis, and LC3B processing as a measure of autophagy (Fig. 5). The pattern of PARP cleavage matched the sub-G1 cell cycle analysis closely, with significantly less cleavage observed at lower concentrations of BBR3610 and earlier time points. The induction of autophagy was less pronounced in some of these experiments, even at earlier time points. LNZ308 showed the clearest increase in LC3B processing to LC3B-II, particularly at day 1, while LN428 and LN229 showed better signals at days 3 and 5. Interestingly, U87 cells, which showed the most sustained G2/M arrest, failed to show much induction of autophagy as measured by LC3B western blot (Fig. 5), suggesting no obligate coupling of the 2 states.

Fig. 5.

Western blot analysis of apoptosis and autophagy of glioma cells treated with BBR3610. Cells were treated with indicated concentrations of BBR3610 for indicated duration and subjected to western blot for detection of LC3B-II and full-length PARP. Actin was detected as a loading control. Representative data of at least 2 independent experiments are shown.

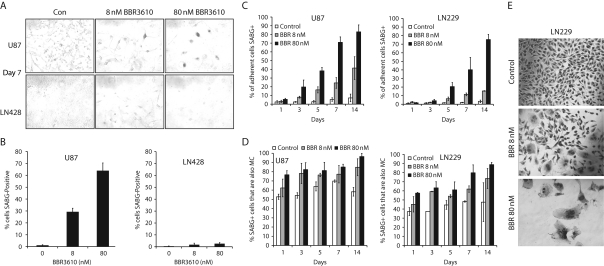

In these experiments, we also observed that some cells persisted, failing to undergo apoptosis, so we analyzed this remaining population separately. It is important to note that while the cell cycle analysis and western blots in Figures 4 and 5 were designed to include all the cells that could be collected either floating in the medium or attached to the plate, the analysis of senescence and mitotic catastrophe only included cells that remained viable and attached to the culture surface. These cells therefore represent the persisting, minority population, as the majority undergo apoptosis (Figs. 4 and 5) and so are not available for study. We first analyzed senescence using senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SABG) staining and found that U87 (Fig. 6A and B) and LN229 (not shown) cells showed an increasing rate of senescence with higher doses of BBR3610, whereas LN428 (Fig. 6A and B) or LNZ308 (not shown) did not. Analysis over time showed that the majority of cells that remained adherent and viable in U87 and LN229 cultures became senescent (Fig. 6C). We also observed that there was an increase in giant, multinucleated cells that had undergone mitotic catastrophe. There was a close association between cells in mitotic catastrophe and senescence as determined by combining SABG staining with Giemsa stain to identify multinucleated cells (Fig. 6D and E). This suggested that cells that avoid apoptosis and remain viable enter senescence and undergo mitotic catastrophe in LN229 and U87 cultures.

Fig. 6.

Cells that survive BBR3610 treatment undergo mitotic catastrophe and become senescent. (A–D) Detection of cellular senescence in human malignant glioma cells. Cells were treated with a vehicle or indicated concentrations of BBR3610 for indicated duration, and then stained using Senescence β-Galactosidase Staining Kit according to the manufacturer's instruction. Cells were examined using the light microscope (magnification: ×200), and cells stained with green color (A) were counted as SABG-positive cells. (B and C) Ratio of the number of SABG-positive cells to that of total cells is calculated. Data are means of two independent experiments done in duplicate. Error bars are SD. (D) Ratio of SABG-positive cells in mitotic catastrophe cells (large cells with multiple nuclei, micronucleation, or lobulated nuclei) was calculated. Data are expressed as means of two independent experiments done in duplicate. Error bars are SD. Since LN428 (A and B) or LNZ308 (data not shown) cells were not stained with SABG, U87-MG and LN229 cells were used for evaluation of cellular senescence. (E) Cells were treated with vehicle (control) or indicated concentrations of BBR3610 for 7 days, stained with Giemsa's stain, and then examined using the light microscope (magnification: ×200). Large cells with multiple nuclei, micronucleation, or lobulated nuclei were counted as mitotic catastrophe cells.

Discussion

There is an ongoing need for new therapies for gliomas, especially considering the poor survival of patients with glioblastoma. Newer generation platinum compounds, such as the polynuclear platinums including BBR3610, appear to be promising cytotoxic agents. We had previously shown the higher efficacy of BBR3610 against glioma in vitro and in vivo when compared with conventional platinum compounds, and also observed that it does not induce immediate apoptosis as does cisplatin.3 This prompted the present study, in which we initially investigated whether another type of cell death, autophagy, was induced by BBR3610. We found that autophagy, when it occurred, was an early response of glioma cells to BBR3610 treatment, even at the IC90 concentration of the drug, and this was evident both in vitro and in vivo. BBR3610 can therefore be added to the list of cancer chemotherapeutic agents that have been shown to induce autophagy in glioma.12 The finding that BBR3610 initially induces autophagy is also consistent with many studies showing that there is no cross-resistance between conventional and polynuclear platinums, which implies very different mechanisms of action at the cellular level.6,7

Further investigation of the role of autophagy, however, failed to show that it was a major decision point in the cellular response to BBR3610. The role of the autophagy that occurs after cancer cells are treated with various agents is not yet clear. It has been proposed that autophagy may be a protective response by a cell attempting to stave off apoptosis, but an alternative possibility is that autophagy is the means by which an agent effects cell killing.12 In either instance, a prediction arises from the hypothesis, which is that inhibition of autophagy would lead to a change in cell viability.12,22 If autophagy is protective, its suppression would reduce viability, perhaps by accelerating entry into other forms of cell death. Alternately, if autophagy is how the cells are being killed, then its suppression would be protective. We chose to investigate this using a common approach, the knockdown of autophagy genes ATG5 and ATG6/BECN1, which are key regulators of autophagy.23 As shown by many others before, this approach reduced the level of autophagy that was induced, but interestingly, it did not result in a consistent or significant change in cell viability. Therefore, our data suggest that autophagy induced by BBR3610 is neither a protective response of cells attempting to avoid cell death nor is it an integral part of this agent's mechanism of action. Our observation corroborates the perceived complexity of autophagy and apoptosis regulation24 and suggests that a cell's response to some agents may not elicit an “either-or” decision.

The lack of impact of the suppression of autophagy on cell viability prompted us to undertake a comprehensive assessment of the response of 4 cell lines to BBR3610 over a 2-week window. We combined cell cycle analysis, which gives information on apoptosis (sub-G1) and mitotic catastrophe (>4n) as well as cell cycle arrest, with western blot for apoptosis and autophagy and stains for senescence and mitotic catastrophe. These data showed clearly that G2/M arrest and autophagy occurred earlier, and that apoptosis occurred later in all the cell lines, with some variation in timing and extent of the responses. In all instances, the higher dose of BBR3610, 80 nM or 10 times the IC90 calculated previously by the clonogenic assay,25 elicited a more profound response. The observation that this response was shared between cell lines of different p53 status (LNZ308: null; U87: wt; LN229 and LN428: mutant), different INK4A status (LNZ308: wild-type; U87, LN229 and LN428: null), and different PTEN status (LNZ308 and U87: mutant; LN229 and LN428: wild-type) suggest no dependence on the presence of these tumor suppressor genes.

In summary, our findings document the complex and phased response of glioblastoma cells to BBR3610, with cell cycle arrest accompanied by autophagy typically occurring earlier, apoptosis occurring later, and with a surviving minority of cells entering senescence and mitotic catastrophe. This finding underscores the importance of looking over time at cellular response and the need to study the spectrum of cellular response, including different modes of cell death for each agent. As BBR3610 and analogues are viable second-generation analogues of BBR3464 and are in preclinical development (http://www.celltherapeutics.com/novel_platinum_complexes), defining the cellular response is an important part of developing these agents further.26 The data presented here further strengthen the case for the viability of BBR3610 as a clinical candidate.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at Neuro-Oncology Journal online.

Conflict of interest statement. N.P.F. is a named inventor on patents relating to BBR3610, which are licensed for possible clinical development.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Center for Targeted Therapy of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (to O.B.) as well as by funding from the National Institutes of Health [RO1CA128991 to O.B. and N.P.F., RO1CA78754 to N.P.F., and 1P50CA127001 and R21CA1108499 to O.B.].

Acknowledgments

We thank Verlene Henry, Lindsay Holmes, and Jennifer Edge for help with the animal experiment.

References

- 1.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. doi:10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billecke C, Finniss S, Tahash L, et al. Polynuclear platinum anticancer drugs are more potent than cisplatin and induce cell cycle arrest in glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2006;8:215–226. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2006-004. doi:10.1215/15228517-2006-004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrell N. Polynuclear platinum drugs. Met Ions Biol Syst. 2004;42:251–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perego P, Gatti L, Caserini C, et al. The cellular basis of the efficacy of the trinuclear platinum complex BBR 3464 against cisplatin-resistant cells. J Inorg Biochem. 1999;77:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(99)00142-7. doi:10.1016/S0162-0134(99)00142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Servidei T, Ferlini C, Riccardi A, et al. The novel trinuclear platinum complex BBR3464 induces a cellular response different from cisplatin. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:930–938. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00061-2. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pratesi G, Perego P, Polizzi D, et al. A novel charged trinuclear platinum complex effective against cisplatin-resistant tumours: hypersensitivity of p53-mutant human tumour xenografts. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:1912–1919. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690620. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6690620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manzotti C, Pratesi G, Menta E, et al. BBR 3464: a novel triplatinum complex, exhibiting a preclinical profile of antitumor efficacy different from cisplatin. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2626–2634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrell N. Polynuclear charged platinum compounds as a new class of anticancer agents. Toward a new paradigm. In: Kelland LR, Farrell N, editors. Platinum-Based Drugs in Cancer Therapy. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2000. pp. 321–338. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGregor TD, Hegmans A, Kasparkova J, et al. A comparison of DNA binding profiles of dinuclear platinum compounds with polyamine linkers and the trinuclear platinum phase II clinical agent BBR3464. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2002;7:397–404. doi: 10.1007/s00775-001-0312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts JD, Peroutka J, Beggiolin G, et al. Comparison of cytotoxicity and cellular accumulation of polynuclear platinum complexes in L1210 murine leukemia cell lines. J Inorg Biochem. 1999;77:47–50. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(99)00137-3. doi:10.1016/S0162-0134(99)00137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kondo Y, Kanzawa T, Sawaya R, et al. The role of autophagy in cancer development and response to therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:726–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc1692. doi:10.1038/nrc1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox JG. The Mouse in Biomedical Research. 2nd ed. Amsterdam; Boston: Elsevier, AP; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diehl KH, Hull R, Morton D, et al. A good practice guide to the administration of substances and removal of blood, including routes and volumes. J Appl Toxicol. 2001;21:15–23. doi: 10.1002/jat.727. doi:10.1002/jat.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanzawa T, Germano IM, Komata T, et al. Role of autophagy in temozolomide-induced cytotoxicity for malignant glioma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:448–457. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401359. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, et al. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19:5720–5728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mizushima N. Methods for monitoring autophagy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2491–2502. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.005. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lal S, Lacroix M, Tofilon P, et al. An implantable guide-screw system for brain tumor studies in small animals. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:326–333. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.2.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boya P, Gonzalez-Polo RA, Casares N, et al. Inhibition of macroautophagy triggers apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1025–1040. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.3.1025-1040.2005. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.3.1025-1040.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, et al. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:741–752. doi: 10.1038/nrm2239. doi:10.1038/nrm2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishii N, Maier D, Merlo A, et al. Frequent co-alterations of TP53, p16/CDKN2A, p14ARF, PTEN tumor suppressor genes in human glioma cell lines. Brain Pathol. 1999;9:469–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondo Y, Kondo S. Autophagy and cancer therapy. Autophagy. 2006;2:85–90. doi: 10.4161/auto.2.2.2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujiwara K, Daido S, Yamamoto A, et al. Pivotal role of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1 in apoptosis and autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:388–397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorburn A. Apoptosis and autophagy: regulatory connections between two supposedly different processes. Apoptosis. 2008;13:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Billecke C, Finniss S, Tahash L, et al. Polynuclear platinum anticancer drugs are more potent than cisplatin and induce cell cycle arrest in glioma. Neuro-Oncology. 2006;8:215–226. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2006-004. doi:10.1215/15228517-2006-004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zerzankova L, Suchankova T, Vrana O, et al. Conformation and recognition of DNA modified by a new antitumor dinuclear Pt(II) complex resistant to decomposition by sulfur nucleophiles. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]