Abstract

Glioblastoma, the most intractable cerebral tumor, is highly lethal. Recent studies suggest that cancer stem-like cells (CSLCs) have the capacity to repopulate tumors and mediate radio- and chemoresistance, implying that future therapies may need to turn from the elimination of rapidly dividing, but differentiated, tumor cells to specifically targeting the minority of tumor cells that repopulate the tumor. However, the mechanism by which glioblastoma CSLCs maintain their immature stem-like state or, alternatively, become committed to differentiation is poorly understood. Here, we show that the inactivation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTor) by the mTor inhibitor rapamycin or knockdown of mTor reduced sphere formation and the expression of neural stem cell (NSC)/progenitor markers in CSLCs of the A172 glioblastoma cell line. Interestingly, combination treatment with rapamycin and LY294002, a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor, not only reduced the expression of NSC/progenitor markers more efficiently than single-agent treatment, but also increased the expression of βIII-tubulin, a neuronal differentiation marker. Consistent with these results, a dual PI3K/mTor inhibitor, NVP-BEZ235, elicited a prodifferentiation effect on A172 CSLCs. Moreover, A172 CSLCs, which were induced to undergo differentiation by pretreatment with NVP-BEZ235, exhibited a significant decrease in their tumorigenicity when transplanted either subcutaneously or intracranially. Importantly, similar results were obtained when patient-derived glioblastoma CSLCs were used. These findings suggest that the PI3K/mTor signaling pathway is critical for the maintenance of glioblastoma CSLC properties, and targeting both mTor and PI3K of CSLCs may be an effective therapeutic strategy in glioblastoma.

Keywords: differentiation, glioblastoma cancer stem cells, mTor, PI3K, self-renewal

Glioblastoma is the most frequent primary intracranial neoplasm in adults. Even with the survival advantage provided by the recently developed protocol of concurrent chemoradiation followed by adjuvant alkylating chemotherapy with temozolomide, the prognosis of patients with glioblastoma remains poor, with the median overall survival in the range of 9–15 months and a 2-year survival rate of 26% in the most favorable subgroup. At present, treatment options are limited at recurrence.1–7 There is an obvious need for development of novel treatment strategies for this disease.

Within the past decade, accumulating evidence from a number of biological systems, such as the blood,8 breast,9 and brain,10–14 has indicated that transformed, cancer stem-like cells (CSLCs) may be the cells that initiate the formation of tumors. This CSLC hypothesis suggests that many cancers are maintained in a hierarchical organization of rare, slowly dividing CSLCs, rapidly dividing amplifying cells, and differentiated cells. CSLCs have been defined as cells that have the capacity to be tumorigenic in vivo and to self-renew, that is, undergo divisions that allow the generation of more CSLCs and give rise to the variety of differentiated cells found in the malignancy.15 Of clinical significance, there is some evidence that the CSLCs are relatively resistant to chemo- and radiotherapeutic approaches.16,17 This implies that the small number of surviving CSLCs in a “seemingly eradicated” tumor after chemoradiotherapy could be the potential source of recurrence. If CSLCs are as such the principal cells in a malignancy with the ability to fuel tumor growth and cause recurrence, then novel cancer therapies may need to target the CSLC population.

Among the possible measures to target CSLCs, one potential option is inducing the differentiation of CSLCs. It is believed that differentiated cells have limited proliferative potential and lose the capacity for self-renewal and tumorigenicity. Furthermore, non-CSLCs are targeted very effectively by chemotherapeutic agents.18,19 However, how CSLCs including glioblastoma CSLCs maintain self-renewal and multipotency of differentiation is poorly understood.20

The signaling pathway composed of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTor) plays a central role in the regulation of cell proliferation, growth, differentiation, and survival.21 Dysregulation of this pathway is frequently observed in glioblastoma.20,22,23 For example, alterations in the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) tumor suppressor gene, including PTEN mutation/deletions that occur in 30%–40% of glioblastoma patients, can also result in this pathway's activation.24 Activation of the PI3K pathway has been found to be associated with reduced survival of glioma patients and it is significantly more frequent in glioblastoma than nonglioblastoma tumors.25 It was also reported that mTor activity is required for the survival of glioblastoma tumor cells and that rapamycin inhibited growth of a U87 xenograft.26,27 Therefore, the inhibition of the PI3K/mTor signaling pathway is being investigated as a potential therapy for cancer. In fact, accumulating evidence from preclinical and early clinical studies suggests that mTor inhibitors, rapamycin, and its derivative, CCI-779, could be used as phase I and II trial agents against glioblastoma.28–30

Recently, it was reported that the loss of PTEN in conjunction with the loss of p53 maintains both neural stem cells (NSCs) and glioma stem/progenitor cells in an undifferentiated state, promoting self-renewal and inhibiting differentiation, an effect attributed in part to activation of myc,31 and PTEN deletion doubled the number of side population cells, which are enriched in tumorigenic cells with stem cell properties, in tumor-derived spheres,32 suggesting that the PI3K pathway may be an important regulator of CSLCs. It is unclear, however, whether mTor regulates or rapamycin affects the fate of glioblastoma CSLCs.

In this study, we show that rapamycin elicits a significant reduction in the CSLC population in the A172 human glioblastoma cell line. We also treated A172 CSLCs with a combination of rapamycin and a PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, or with NVP-BEZ235, a dual PI3K/mTor inhibitor. Combinational inhibition of mTor and PI3K not only augmented the effect of rapamycin, but also elicited a prodifferentiation effect on A172 CSLCs as well as on patient-derived glioblastoma CSLCs. Moreover, the exposure of A172 and patient-derived glioblastoma CSLCs to NVP-BEZ235 before transplantation promoted their differentiation and significantly decreased their tumorigenicity in nude mice. These results suggest that the PI3K/mTor signaling pathway may act as an important regulator of CSLC properties and that dual blocking of mTor and PI3K on CSLCs could be effective in the treatment of glioblastoma.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Antibodies

Rapamycin and LY294002 were purchased from Calbiochem. NVP-BEZ235 was purchased from Axon Medchem. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) were from Peprotech. Anti-Nestin (AB5922) was from Chemicon. Anti-Bmi1 (05-637) was from Upstate. Anti-Sox2 (MAB2018), anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; AF2594), and anti-βIII-tubulin (MAB1195) were from R&D. Anti-phospho-Akt (#4058), anti-Akt (#9272), anti-phospho-p70S6K (#9205), anti-p70S6K (#2708), anti-phospho-4EBP1 (#2855), anti-4EBP1 (#9452), and anti-mTor (#2972) were from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-β-actin (A5441) was from Sigma. Anti-CD133 (AC133) was from Miltenyi Biotec. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for immunoblotting were from Upstate. Alexa 488- and 594-conjugated secondary antibodies for immunocytochemistry were from Molecular Probes.

A172 Cell Culture

A172 glioblastoma cells were obtained from the RIKEN Bioresource Center and were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin. Immunoblot and/or reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR analyses revealed that A172 cells maintained in the serum culture condition do not express either PTEN or p53 but do express EGFRvIII (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1E).

For the selective propagation of A172 CSLCs, A172 cells were seeded in 35‐mm dishes at a density of 3 × 105 cells/mL in a stem/progenitor cell culture medium (serum-free DMEM/F12 [GIBCO] supplemented with N2 [AR003, R&D]) in the presence of 20 ng/mL EGF and bFGF. Fresh EGF and bFGF were added every day. Using this culture condition, cell aggregates known as spheres were formed within 3 days after seeding and the spheres were mechanically dissociated and reseeded at intervals of 3–4 days. To induce the differentiation of A172 CSLCs, dissociated cells from spheres cultured for 14 days in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium with EGF and bFGF were cultured in the differentiation culture condition (DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS) for 10 days.

Sphere Formation Assay

For the primary sphere formation assay, A172 cells were seeded in 35‐mm dishes at a density of 3 × 105 cells/mL in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium in the presence of 20 ng/mL of EGF and bFGF. After 3 days, cells demonstrated sphere structures, which were counted as primary spheres. The inhibitors (rapamycin, LY294002, and NVP-BEZ235) were added at the time of seeding or, in some cases, after the formation of the spheres.

For the secondary sphere formation assay, cells cultured in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium containing EGF and bFGF at a density of 3 × 105 cells/mL in the presence or the absence of inhibitors for 3 days were collected and, after washing with phosphate-buffered saline, mechanically dissociated and resuspended in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium containing EGF and bFGF at a density of 3 × 105 cells/mL. These cell suspensions were then transferred to 35‐mm dishes, and the numbers of secondary spheres were counted after 3 days.

Culture of Patient-Derived Glioblastoma CSLCs

Primary human glioblastoma CSLCs, SJ28P3 and #27, were derived from surgical specimens obtained after informed consent from glioblastoma patients in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the National Cancer Center and Yamagata University School of Medicine. Tumors were minced into small pieces with scissors, washed with saline, and incubated in 0.05% pronase (53702, Calbiochem), 0.02% collagenase II (C-6885, Sigma), and 0.02% DNaseI (Sigma) in saline for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were washed once in saline, passed through a 70-µm cell strainer (Falcon), and cultured in the primary human stem/progenitor cell culture medium (serum-free DMEM/F12 containing B27 [17504-044, GIBCO]) in the presence of 20 ng/mL of EGF and bFGF. Fresh EGF and bFGF were added every day. Primary tumor spheres were dissociated and reseeded once every 3–4 days. On the fifth or sixth passage, #27 tumor spheres were used for experiments. For the monolayer culture of SJ28P3, cells were plated onto collagen-coated dishes (Iwaki) in the primary human stem/progenitor cell culture medium in the presence of 20 ng/mL of EGF and bFGF after the fourth passage, as described previously.33,34 Monolayer-cultured SJ28P3 cells were dissociated by Accutase (Sigma) and reseeded once every 4–5 days. On the sixth or seventh passage, SJ28P3 cells were used for experiments. Immunoblot and/or RT-PCR analyses revealed that SJ28P3 cells express EGFRvIII and not PTEN or p53 under the monolayer culture condition (Supplementary Material, Fig. S6B). Differentiation of human glioblastoma CSLCs was induced as described for A172 CSLCs.

Animal Experiments

Because A172 cells (1 × 107) from spheres cultured for 14 days did not form tumors after subcutaneous injection into 5-week-old male BALB/cAJcl− nu/nu mice (CLEA Japan, Inc.), we cultured A172 CSLCs by the monolayer culture method.33,34 For the monolayer culture of A172 CSLCs, dissociated cells from spheres cultured for 14 days in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium with EGF and bFGF were plated onto collagen-coated dishes, as described above. Monolayer-cultured A172 CSLCs were dissociated by Accutase and reseeded once every 6–7 days. After at least 8 weeks of monolayer culture, A172 CSLCs were used for experiments. Monolayer-cultured A172 CSLCs express EGFRvIII and not PTEN or p53 (Supplementary Material, Fig. S8B). Differentiation of monolayer-cultured A172 CSLCs was induced as described above.

For subcutaneous xenografts, monolayer-cultured A172 CSLCs and SJ28P3 cells (1 × 105) were injected subcutaneously in the left flank region of 5-week-old male BALB/cAJcl− nu/nu mice (CLEA Japan, Inc.). Tumor diameters were measured at indicated day intervals, and volumes were calculated from 5 mice per data point (mm3 = width2 × length/2).

For intracranial xenografts, monolayer-cultured A172 CSLCs and SJ28P3 cells (1 × 104) in 10 µL of the DMEM/F12 medium were injected stereotactically into the right cerebral hemisphere of 5-week-old male BALB/cAJcl− nu/nu mice at a depth of 3 mm. In either xenograft model, differentiated A172 CSLCs and SJ28P3 cells induced to differentiate in the presence of FBS (1 × 107) did not form tumors (data not shown). All animal experiments were performed under the protocol approved by the Animal Research Committee of Yamagata University.

Knockdown of mTor by RNA Interference

Immediately after A172 cells were seeded at a density of 8 × 105 cells/mL in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium, they were transfected with mTor siRNAs (#1, FAP1-HSS103825; and #2, FAP1-HSS103827; Invitrogen) or nontargeting control siRNA (Stealth RNAi Negative Control Medium GC Duplex #2, Invitrogen) using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen). After 4 hours, cells were reseeded in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium with EGF and bFGF at a density of 3 × 105 cells/mL in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium containing EGF and bFGF for a sphere formation assay. Counting of sphere numbers, RT-PCR, and immunoblot analysis were performed after 3 days.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviations and analyzed using the unpaired Student's t-test, except that mouse survival was evaluated by the Kaplan–Meier method and analyzed using the log-rank test.

Results

Isolation and Characterization of CSLCs from A172 Cells

To examine the effect of rapamycin on the fate of CSLCs in glioblastoma cells, we used the A172 cell line, which was reported to contain CSLCs.35,36 A172 cells were cultured in the stem/progenitor cell culture condition devoid of serum as described previously.35 Large numbers of small spheres with diameters of ∼100 µm were observed within 3 days (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A). After 3 days, we investigated the expression of NSC/progenitor markers (cd133 mRNA and Nestin, Bmi1, and Sox2 proteins), the neural marker βIII-tubulin, and an astrocytic marker GFAP. As shown in Supplementary Material, Fig. S1B and C, the expression of NSC/progenitor markers (cd133 mRNA and Nestin, Bmi1, and Sox2 proteins) increased in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium with EGF and bFGF when compared with medium containing serum, but βIII-tubulin was unchanged. The expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) was not detected by immunoblot analysis. These spheres could be passaged multiple times by mechanical dissociation and reseeding in fresh medium every 3–4 days and could be maintained for at least 4 weeks. These results indicate that spheres contain cells with the ability to self-renew.

To test whether individual cells derived from these spheres had differentiative capacity, we cultured A172 cells, which were cultured in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium with EGF and bFGF for 14 days, for 6 hours or 10 days on ornithine-coated coverslips under the differentiation culture condition. After 6 hours, most cells were labeled for CD133, Bmi1, and Sox2, but a few were labeled for the neuronal marker βIII-tubulin and none were labeled for GFAP, suggesting that cells from A172 spheres might be undifferentiated CSLCs (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1D). After 10 days, however, ∼90% of the cells were immunolabeled for βIII-tubulin (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1D) and ∼2% for GFAP (data not shown), but few for CD133, Bmi1, and Sox2. These results show that A172 spheres formed in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium contain CSLCs that are multipotent, giving rise to cells of neuronal and glial lineages.

Rapamycin and Loss of mTor Can Inhibit A172 Cell Sphere Formation and the Expression of NSC/Progenitor Markers

To test the response to rapamycin of A172 CSLCs, we performed a sphere formation assay. Putative CSLCs in A172 cells cultured with FBS were amplified by primary sphere formation, and their self-renewing capacity was demonstrated by observing the number of secondary spheres formed.

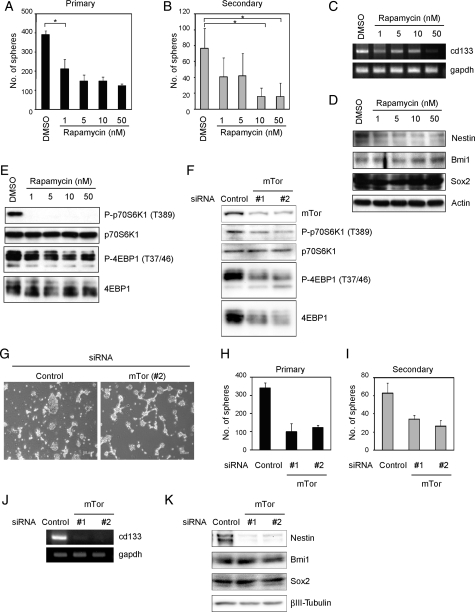

Rapamycin was treated immediately after plating at concentrations ranging from 1 to 50 nM. As shown in Fig. 1A, rapamycin resulted in marked inhibition of A172 sphere formation. Furthermore, the expression of NSC/progenitor markers (cd133 mRNA and Nestin protein) was lower than without treatment, although the expression of Sox2 and Bmi1 proteins was unchanged (Fig. 1C and D). Treatment of A172 cells with 1–50 nM of rapamycin reduced the level of p70S6K phosphorylation at Thr389 and 4EBP1 at The37/46, which were downstream targets of mTor (Fig. 1E). On the basis of the reports that the generically maximum concentration of rapamycin is 200 nM in cells, we investigated this concentration effect on sphere formation and phosphorylation of p70S6K and 4EBP1 (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). Effects of 200 nM showed the same results of 50 nM in all assays, suggesting that 50 nM is the saturation concentration, and so we decided to treat tumor cells with rapamycin at a concentration of ∼50 nM. It has been shown that rapamycin reduces cell viability in some cell lines,37,38 and so we investigated whether it could also reduce cell viability. Trypan blue analysis showed that rapamycin treatment had little effect on survival at any concentration (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3A).

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of mTor reduces A172 sphere formation and the expression of NSC/progenitor markers. A172 cells were cultured in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium with EGF and bFGF in the absence or the presence of rapamycin for 3 days. The numbers of generated primary spheres were counted (A). The primary spheres were dissociated and cultured with EGF and bFGF in the absence of rapamycin for 3 days. The numbers of secondary spheres were counted (B). (C–E) Cells were cultured as described in (A). The expression of cd133 or gapdh mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR (C). Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies (D and E). (F–K) Cells were transfected with the indicated siRNA. Then, cells were reseeded in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium containing EGF and bFGF for assays to count primary sphere numbers (G and H), RT-PCR (J), and immunoblot (F and K) analysis after 3 days. The primary spheres were dissociated and cultured with EGF and bFGF for 3 days. The numbers of secondary spheres were counted (I). Results in (A), (B), (H), and (I) are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05.

In the secondary sphere formation assay, cells cultured in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium containing EGF and bFGF in the presence or the absence of inhibitors were dissociated to form a suspension of single cells, then replated in the presence of EGF and bFGF to allow the formation of spheres in the absence of rapamycin. The number of secondary spheres corresponded to the number of sphere-producing cells within the primary sphere. The number of secondary spheres decreased at a concentration of 10 nM of rapamycin (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that rapamycin weakened the self-renewal capacity of A172 CSLCs.

The high selectivity of rapamycin toward mTor has been documented.39 Nevertheless, to further confirm the specificity of rapamycin, we used RNAi experiments. Two siRNAs, designed to target 2 different sequences of mTor, were selected. Figure 1F shows that the introduction of siRNAs targeting the mTor gene, but not control siRNA, reduced the amounts of endogenous mTor proteins and partially inhibited the phosphorylation level of p70S6K and 4EBP1. Similar to rapamycin treatment, depletion of mTor impaired sphere formation not only in primary assays (Fig. 1G and H), but also in the secondary ones (Fig. 1I). The expression of NSC/progenitor markers (cd133 mRNA and Nestin protein) was lower than without treatment (Fig. 1J and K). These results indicated that mTor plays an important role in the self-renewal capacity of A172 CSLCs.

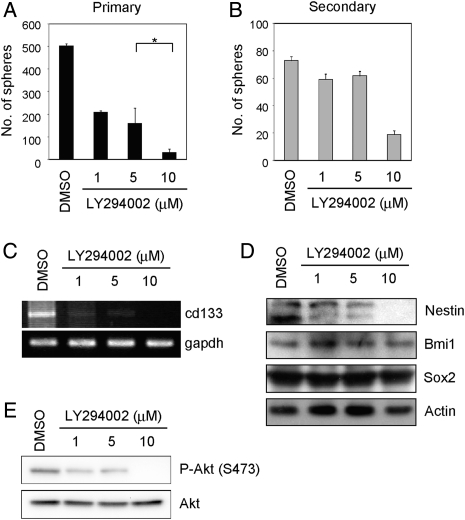

LY294002 Can Inhibit A172 Cell Sphere Formation and the Expression of NSC/Progenitor Markers

Because mTor is one of the downstream effectors of the PI3K signaling pathway and the PI3K pathway is constitutively activated in many glioblastoma cell lines including A172 cells (data not shown),40 we speculated that the PI3K inhibitor may affect the self-renewal capacity. Therefore, we determined the effect of LY294002 on A172 CSLCs. We found that LY294002 could inhibit A172 cell primary sphere formation (Fig. 2A) and reduce the expression of NSC/progenitor markers (cd133 mRNA and Nestin protein) (Fig. 2C and D) at a concentration of ∼10 µM, at which LY294002 inhibited phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 substantially (Fig. 2E). In parallel experiments, cell death was quantified by Trypan blue dye exclusion. LY294002 had no effect on cell death (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3B). Furthermore, the number of secondary spheres was remarkably decreased at a concentration of 10 µM LY294002 (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that LY294002, as well as rapamycin, weakened the self-renewal capacity of A172 CSLCs.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of PI3K reduces A172 sphere formation and the expression of NSC/progenitor markers. (A) A172 cells were cultured in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium with EGF and bFGF in the absence or the presence of LY294002 for 3 days. The numbers of generated primary spheres were counted. (B) The primary A172 spheres were dissociated and cultured in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium with EGF and bFGF in the absence of LY294002 for 3 days. The numbers of secondary spheres were counted. (C–E) Cells were cultured as described in (A). Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies (D and E). The expression of cd133 or gapdh mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR (C). Results in (A) and (B) are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05.

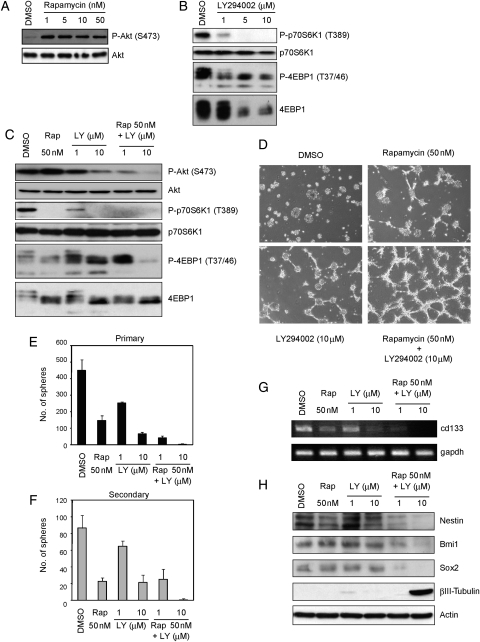

Combination Treatment with Rapamycin and LY294002 Elicits a Prodifferentiation Effect on A172 CSLCs

Recent studies demonstrated that the combination of PI3K and mTor inhibits proliferation and survival of bulk glioblastoma cells more effectively than the inhibition of either alone.41,42 We therefore hypothesized that inhibitors of PI3K signaling augment the effect of rapamycin on A172 CSLCs. To test our hypothesis, we first analyzed the effect of a combination treatment of rapamycin with LY294002 on the PI3K–mTor signaling pathway. Interestingly, rapamycin activated PI3K signaling (Fig. 3A), presumably due to the inhibition of an mTor-dependent retrograde signal. This observation, which has also been made by others,43 suggests that rapamycin weakens this negative feedback and results in activation of the PI3K signaling pathway in this assay. LY294002 also inhibits phospho-4EBP1 incompletely (Fig. 3B). As shown in Fig. 3C, however, a combination of rapamycin plus LY294002 suppressed not only the level of phospho-Akt, but also phospho-4EBP1. Our finding that the combined treatment was effective in blocking of PI3K/mTor pathway signaling prompted us to investigate whether it affected the CSLC state of A172 CSLCs. Trypan blue analysis showed that the combined treatment had little effect on survival at any concentration (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3D). With concomitant use of rapamycin and LY294002, A172 CSLCs showed a neurite-like outgrowth, and the formation of primary and secondary spheres was grossly inhibited compared with the single-agent treatment (Fig. 3D-F). The combined treatment had no effect on cell viability but caused reduction in the total cell number over the observation period, consistent with its ability to efficiently induce differentiation (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3E). In parallel with these results, the expression of NSC/progenitor markers (cd133 mRNA and Nestin protein) was additionally lower than the single-agent treatments (Fig. 3G and H). Expression of Sox2 and Bmi1 proteins was lower only when the A172 CSLCs were treated with a combination of the 2 inhibitors (Fig. 3H). Interestingly, the combination treatment increased βIII-tubulin expression in A172 CSLCs (Fig. 3H) but not in A172 cells originally maintained in the presence of serum (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4). Therefore, it is probable that the PI3K/mTor signaling pathway is specifically involved in the regulation of CSLCs' capacity to differentiate.

Fig. 3.

Effect of combination treatment with rapamycin and LY294002 on A172 cells. (A–E, G, and H) A172 cells were cultured in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium with EGF and bFGF in the absence or the presence of rapamycin (Rap) and/or LY294002 (LY) for 3 days. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies (A–C and H). The expression of cd133 or gapdh mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR (G). Cells were cultured as described above and then observed under a phase-contrast microscope (magnification ×40) (D). The numbers of generated primary spheres were counted (E). The primary A172 spheres were dissociated and cultured with EGF and bFGF in the absence of the indicated inhibitors for 3 days. The numbers of secondary spheres were counted (F). Results in (E) and (F) are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments.

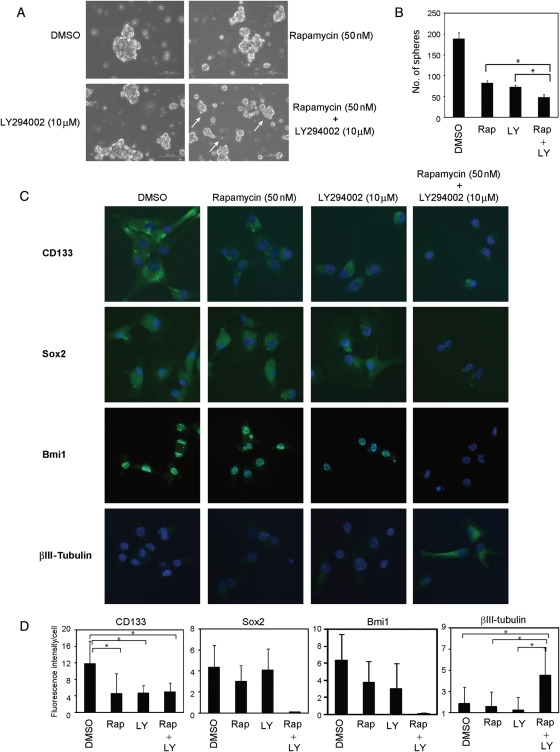

To further test whether the PI3K/mTor signaling pathway affected the differentiative capacity of A172 CSLCs, we treated the A172 CSLCs with the 2 inhibitors, which were maintained in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium with EGF and bFGF for as long as 14 days. Cells treated with the 2 inhibitors adopted a more differentiated morphology (adherent and similar to a neurite outgrowth; Fig. 4A) and formed fewer spheres than single agents (Fig. 4B). CD133 expression decreased after 3 days of single-agent treatment with rapamycin or LY294002, although the combination treatment had no additional effect. However, Sox2 and Bmi1 expression decreased only after 3 days of combination treatment with rapamycin and LY294002. Furthermore, βIII-tubulin expression increased only with the combination treatment (Fig. 4C and D). A combination of rapamycin plus LY294002 suppressed not only the level of phospho-Akt, but also phospho-4EBP1, which was inhibited partially by single agents in this assay (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5). These results suggest that the PI3K/mTor signaling pathway maintains CSLCs' undifferentiated status, whereas dual inhibition of mTor and PI3K elicits a prodifferentiation effect on A172 CSLCs.

Fig. 4.

Combination treatment with rapamycin and LY294002 inhibits self-renewal and elicits differentiation of A172 CSLCs. (A and B) A172 CSLCs were cultured in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium with EGF and bFGF for 14 days before inhibitor treatment. Then, A172 CSLCs were treated with the indicated inhibitors for 3 days, and observed under a phase-contrast microscope (magnification ×100). Arrows show neurite-like morphology (A). The numbers of spheres were counted (B) (rapamycin [Rap, 50 nM] and/or LY294002 [LY, 10 µM]). (C) Cells were cultured as described in (A) and plated on ornithine-coated coverslips with 10% serum for 6 h to facilitate cell adhesion to the dish. Cells were then immunolabeled with the indicated antibodies. (D) Results of quantitative analysis of 3 independent experiments for (C) are shown (Rap: rapamycin, 50 nM and/or LY: LY294002, 10 µM). Results in (B) are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05. Data in (D) are the mean ± SD of values obtained from at least 200 cells in each of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05.

Dual Inhibition of mTor and PI3K by NVP-BEZ234 Elicits a Prodifferentiation Effect on A172 CSLCs

Recently, dual PI3K/mTor inhibitors have been synthesized, including NVP-BEZ235. This agent potently and reversibly inhibits class I PI3K catalytic activity by competing at its ATP-binding site and also inhibits mTor catalytic activity, but does not target other protein kinases.44

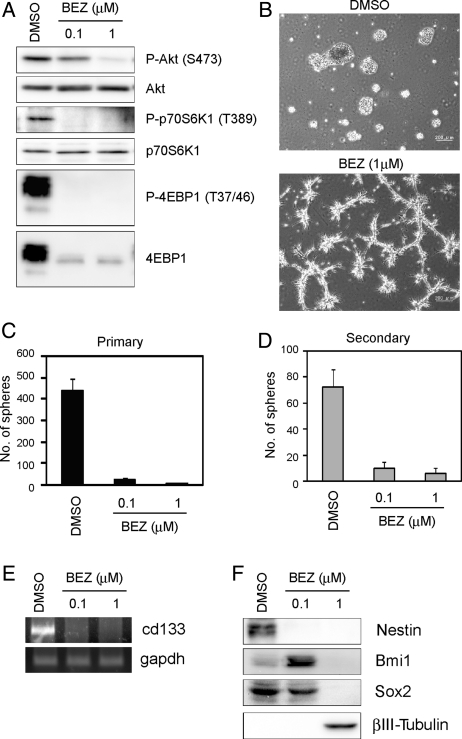

The effect of NVP-BEZ235 on PI3K and mTor activity in an A172 sphere culture was examined first. Figure 5A shows that treatment with 1 µM NVP-BEZ235 inhibited the phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473, p70S6K at Thr389, and 4EBP1 at Thr37/46. NVP-BEZ235 inhibited A172 primary and secondary sphere formation (Fig. 5B-D) and reduced the expression of NSC/progenitor markers, although 0.1 µM NVP-BEZ235 increased Bmi1 more than vehicle dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) treatment (Fig. 5E and F). At the same time, βIII-tubulin was increased at 1 µM (Fig. 5F). In parallel experiments, NVP-BEZ235 had no effect on cell death (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3D). Similar to the combination treatment of rapamycin plus LY294002, NVP-BEZ235 had no effect on cell viability but caused reduction in the total cell number over the observation period (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3E).

Fig. 5.

NVP-BEZ235 inhibits A172 sphere formation and reduces the expression of NSC/progenitor markers. (A–C, E, and F) A172 cells were cultured in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium with EGF and bFGF in the absence or the presence of NVP-BEZ235 (BEZ) for 3 days. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies (A and F). The expression of cd133 or gapdh mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR (E). Cells were cultured as described above and then observed under a phase-contrast microscope (magnification ×40) (B). The numbers of generated primary spheres were counted (C). The primary A172 spheres were dissociated and cultured with EGF and bFGF in the absence of the indicated inhibitors for 3 days. The numbers of secondary spheres were counted (D). Results in (C) and (D) are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments.

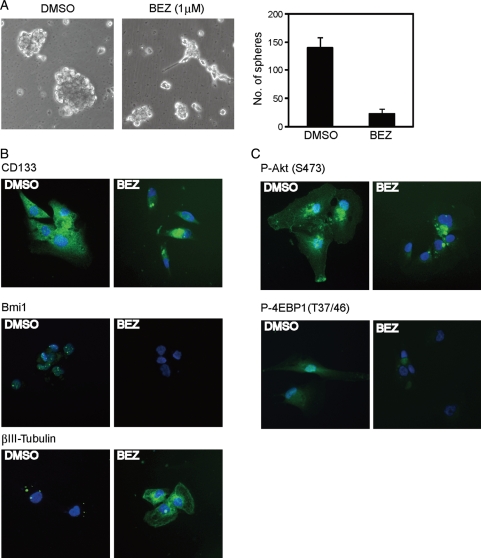

Next, we checked whether NVP-BEZ235 could regulate CSLCs' capacity to differentiate. NVP-BEZ235 treatment disrupted the sphere formation by A172 CSLCs maintained under the stem/progenitor cell culture condition for 14 days, and some cells began to show a more neurite-like morphology (Fig. 6A). We also observed an increase in the expression of βIII-tubulin and a decrease in CD133 and Bmi1 (Fig. 6B). Relative to control cells (DMSO), NVP-BEZ235–treated cells exhibited reduced PI3K/mTor activity (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that similar to a combination of rapamycin plus LY294002, dual inhibition of mTor and PI3K by NVP-BEZ234 elicits a prodifferentiation effect on A172 CSLCs.

Fig. 6.

NVP-BEZ235 inhibits self-renewal and elicits differentiation of A172 CSLCs. (A) A172 CSLCs were cultured in the stem/progenitor cell culture medium with EGF and bFGF for 14 days before NVP-BEZ235 (BEZ) treatment. Then, A172 CSLCs were treated with BEZ for 3 days and observed under a phase-contrast microscope (left, magnification ×100). The numbers of generated primary spheres were counted (right). (B and C) Cells were cultured as described above and were plated on ornithine-coated coverslips with 10% serum for 6 h to facilitate cell adhesion to the dish. Cells were then immunolabeled with the indicated antibodies. Results in (A) are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05.

Dual Inhibition of mTor and PI3K Elicits a Prodifferentiation Effect on Patient-Derived Glioblastoma CSLCs

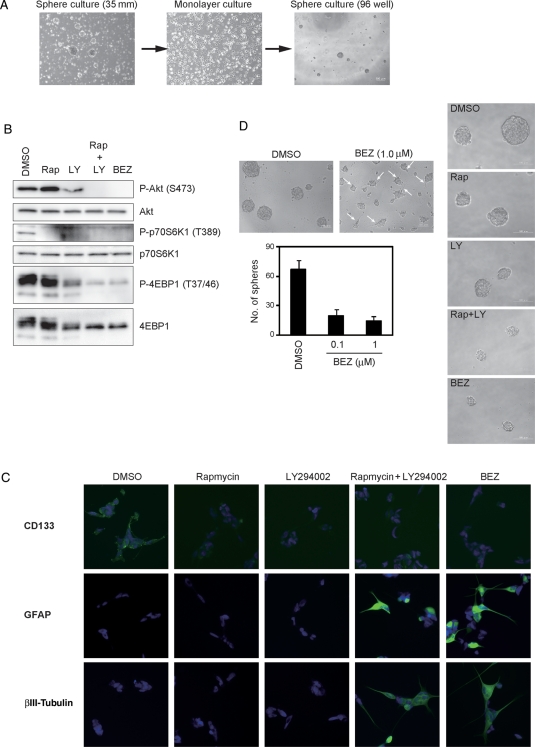

We next considered whether dual inhibition of mTor and PI3K by NVP-BEZ235 or concomitant use of rapamycin and LY294002 affected patient-derived glioblastoma CSLCs. Tumor-derived cells (SJ28P3) were cultured by using the reported methods (Fig. 7A).33,34 As shown in the Supplementary Material, Fig. S6A, after withdrawal of growth factors and adding serum, expression of CD133 was downregulated and expression of βIII-tubulin and GFAP was upregulated, suggesting that individual cells are multipotent, giving rise to both neuronal and glial lineages.

Fig. 7.

Dual blocking of mTor and PI3K inhibits self-renewal and elicits differentiation of patient-derived glioblastoma CSLCs. (A) The primary spheres (SJ28P3) were seeded intact onto collagen. This generated a primary monolayer that could be passaged and subsequently propagated. Phase-contrast pictures of a typical sphere formed directly from a tissue sample (left) and from a monolayer culture (right); phase-contrast image of a sphere-derived monolayer culture (middle). (B and C) SJ28P3 monolayer cells were treated with rapamycin (Rap, 50 nM) and/or LY294002 (LY, 10 µM) and NVP-BEZ235 (BEZ, 1 µM) for 3 days, and the levels of indicated proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting (B) and immunocytochemistry (C). (D) SJ28P3 monolayer-cultured cells were cultured in the primary human stem/progenitor cell culture medium with EGF and bFGF in the absence or the presence of BEZ for 3 days for a sphere formation assay. Arrows show neurite-like morphology (left upper). Representative images of spheres formed in the presence or the absence of indicated inhibitors are shown (right). Results in (D) are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments (left lower).

Following 3 days' exposure of monolayer-cultured SJ28P3 to inhibitors, mTor and PI3K activities were inhibited only when NVP-BEZ235 or a combination of rapamycin and LY294002 was used (Fig. 7B). We observed a decrease in the expression of CD133 after rapamycin or LY294002 treatment, although the combination treatment had no additive or synergistic effect. NVP-BEZ235 treatment reduced CD133. Importantly, NVP-BEZ235 and a combination of rapamycin and LY294002 caused expression of GFAP and βIII-tubulin to upregulate (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, consistent with this, NVP-BEZ235 treatment resulted in marked reduction in sphere formation as well as in decreased sizes of nonetheless formed spheres, with cells showing more neurite-like morphology (Fig. 7D). Also, dual inhibition of PI3K and mTor induced G0/G1 arrest (Supplementary Material, Table S1) and decreased the growth rate (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3E). Another patient-derived glioblastoma (#27) gave the same results as SJ28P3 (Supplementary Material, Fig. S7). Therefore, the effective dual inhibition of mTor and PI3K may also elicit a prodifferentiation effect on patient-derived glioblastoma CSLCs.

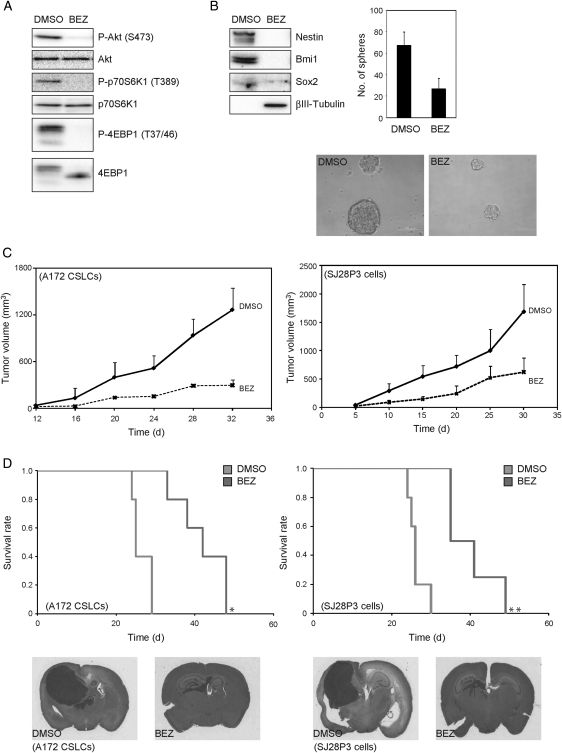

NVP-BEZ235–Treated Glioblastoma CSLCs Have Reduced Capacity of Tumor Formation In Vivo

Thus far, the results have suggested that dual inhibition of mTor and PI3K produces a prodifferentiation effect on A172 and patient-derived glioblastoma (SJ28P3 and #27) CSLCs and depletes the pool of CSLCs. From this, we inferred that the in vitro reduction in the CSLCs would correspond to a similar decline in the ability of NVP-BEZ235–treated cells to form xenografts in nude mice. To test this, we used monolayer-cultured A172 CSLCs, which showed the capacity of sphere formation and differentiation toward the neuronal lineage (Supplementary Material, Fig. S8C), because cells from spheres cultured for 14 days could not form tumors in nude mice. Monolayer-cultured A172 CSLCs were exposed to the inhibitor for 3 days, before subcutaneous and intracranial injection into immunodeficient mice. As shown in Fig. 8B, monolayer-cultured A172 CSLCs treated with NVP-BEZ235 showed a reduction in sphere numbers and a tendency to decrease the sphere size. Similar to SJ28P3 cells, coinhibition of PI3K and mTor induced G0/G1 arrest (Supplementary Material, Table S1) and decreased growth (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3E). We also confirmed that the phosphorylation of Akt, p70S6K, and 4EBP1 in monolayer-cultured A172 CSLCs is efficiently inhibited by NVP-BEZ235 for 3 days (Fig. 8A) and it also reduces the expression of Nestin, Bmi1, and Sox2 and causes the expression of βIII-tubulin to upregulate (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

NVP-BEZ235–treated cells have reduced capacity of tumor formation in vivo. Monolayer-cultured A172 CSLCs were treated with NVP-BEZ235 (BEZ, 1 µM) for 3 days, and the levels of indicated proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting (A and B). (B) The numbers of generated spheres were counted (right upper). Representative images of spheres are shown (right lower). Results in the graph are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments. (C) Monolayer-cultured A172 CSLCs (left) and SJ28P3 cells (right) treated with vehicle (DMSO) or NVP-BEZ235 for 3 days in vitro (1 × 105) were injected subcutaneously into BALB/c− nu/nu mice (5 mice per group), and the size of subcutaneous tumors was measured at the indicated time points. (D) Monolayer-cultured A172 CSLCs (left) and SJ28P3 cells (right) treated with vehicle (DMSO) or NVP-BEZ235 for 3 days in vitro (1 × 104) were injected intracranially into BALB/c− nu/nu mice (5 mice per group), and the survival of mice was evaluated by the Kaplan–Meier analysis (log-rank test: *P = .048 and **P = .049; upper). Alternatively, mice were sacrificed at 30 days after the intracranial injection, and the tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (lower).

We then injected monolayer-cultured A172 CSLCs into nude mice subcutaneously and intracranially. In the subcutaneous model, all animals receiving DMSO (vehicle)-treated A172 CSLCs developed large tumor masses, whereas A172 CSLCs that have undergone differentiation after a 3-day NVP-BEZ235 treatment formed only small tumors (Fig. 8C). Similarly, in the intracranial model, massive tumors were observed in animals injected with DMSO-treated A172 CSLCs, whereas smaller tumors were formed in NVP-BEZ235–treated A172 CSLCs (Fig. 8D). Consistent with these results, the survival of the mice inoculated with NVP-BEZ235–treated cells was significantly prolonged compared with mice injected with DMSO-treated cells (Fig. 8D). Similar results were obtained when patient-derived glioblastoma CSLCs (SJ28P3) were used (Fig. 8C and D). These data suggested that dual inhibition of PI3K and mTor induces differentiation and reduces the tumorigenic potential of glioblastoma CSLCs.

Discussion

Recent evidence suggests that glioblastoma CSLCs may be important for the initiation, propagation, and recurrence of glioblastoma, and hence glioblastoma CSLCs are now drawing attention as critical therapeutic targets.45 An understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of glioblastoma CSLCs may thus be a significant matter. Here, we showed that mTor regulates and rapamycin decreases the self-renewal of glioblastoma CSLCs. Importantly, blocking of both PI3K and mTor activity by inhibitors promotes differentiation of glioblastoma CSLCs and reduces their tumorigenicity in mice.

Although loss of PTEN has been associated with glioblastoma development in the mouse31 and activation of the PI3K/mTor pathway has been shown to be required for breast CSLC viability and maintenance,46 whether mTor regulates the fate of glioblastoma CSLCs is not clear. In our study, rapamycin and knockdown of mTor by siRNA significantly reduced not only sphere numbers but also the expression of NSC/progenitor markers (cd133 mRNA and Nestin protein) in A172 CSLCs. However, the expression of other NSC/progenitor markers, Sox2 and Bmi1, and differentiation markers were not affected. These results suggest that inhibition of mTor alone may be insufficient for differentiation. Recently, it has been proposed that selective mTor inhibition may lead to PI3K activation, thereby limiting the effectiveness of mTor inhibitors.47 Consistently, previous studies demonstrated that cooperation between blockade of PI3K and mTor signaling also impacts autophagy in bulk glioma cells41 and proliferative arrest in bulk glioma cells and xenograft tumors in the mouse.42 In glioblastoma CSLCs, we found in this study that the combination treatment of rapamycin and LY294002 or NVP-BEZ235, which suppressed phosphorylation of Akt, p70S6K, and 4EBP1, not only decreased the expression of Sox2 and Bmi1, but also increased βIII-tubulin and GFAP. Our findings provide the first evidence in glioblastoma CSLCs that the negative feedback to PI3K from mTor can be overcome by dual inhibition of mTor and PI3K, accompanied by inhibition of self-renewal and induction of differentiation.

Recently, Liu et al.48 have demonstrated that dual inhibition of mTor and PI3K by NVP-BEZ235 elicits multifaceted antitumor activities by inducing cell cycle arrest, downregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor, and autophagy in bulk human glioblastoma cells. The results of our study add another facet to the activity of NVP-BEZ235, namely, induction of differentiation in glioblastoma CSLCs. Significantly, glioblastoma CSLCs transiently treated with NVP-BEZ235 had reduced capacity to form xenograft in nude mice. Thus, together with the fact that it is an orally available drug,44 NVP-BEZ235 may be promising as an antiglioma agent. Of note, there are reports showing that BMP4 or inhibitors of TGF-β signaling deprived tumorigenicity of glioma stem cells by promoting differentiation.49,50 These results, in conjunction with the present study, are in support of the idea that differentiation-inducing therapy may be a candidate to improve the treatment outcomes in patients with glioblastoma.

Why do glioblastoma CSLCs undergo differentiation by dual inhibition of PI3K and mTor? Akt may be one of the key factors. As other groups reported,41,42 our results show that the effect of dual blocking by rapamycin plus LY294002 or NVP-BEZ235 suppressed activation of Akt, which is a molecule upstream of mTor in the PI3K/Akt/mTor signaling pathway. Akt negatively regulates transcription through the forkhead family of transcription factors (FoxO).51 FOXO3a has been shown to induce differentiation of Bcr-Abl–transformed cells through transcriptional downregulation of Id1.52 The conditional deletion of FoxOs in specific tissues has demonstrated lineage-restricted tumorigenesis.53 Therefore, when Akt is inactivated by dual inhibition of mTor and PI3K, FoxOs may be upregulated and promote differentiation of glioblastoma CSLCs.

The chemo- and radioresistance of glioblastoma CSLCs render their clinical management difficult.54–56 One novel treatment targeting CSLCs aims to force the CSLCs to differentiate into nondividing cells. If this were possible, patients with brain tumors would be able to lead a normal life because the cells would differentiate terminally and the tumor would stop growing.49 In this respect, combination targeting of mTor and PI3K, which effectively induces differentiation of glioblastoma CSLCs, may be a promising approach in the treatment of glioblastoma.

We showed that a novel system operates in glioblastoma CSLCs and also showed an undocumented role for mTor in glioblastoma CSLCs. Significantly, glioblastoma CSLCs underwent differentiation and had reduced tumorigenic capacity by dual inhibition of mTor and PI3K. These findings suggest that inhibition of the PI3K/mTor signaling pathway both at PI3K and mTor is a potential therapeutic strategy for glioblastoma.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material is available at Neuro-Oncology online.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research, Challenging Exploratory Research, Young Scientists, and for Scientific Research on Priority areas from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, by a Grant-in-Aid from the Global COE program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, by a Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan, and by a grant from the Japan Brain foundation.

References

- 1.Brandes AA, Fiorentino MV. The role of chemotherapy in recurrent malignant gliomas: an overview. Cancer Invest. 1996;14:551–559. doi: 10.3109/07357909609076900. doi:10.3109/07357909609076900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang SM, Theodosopoulos P, Lamborn K, et al. Temozolomide in the treatment of recurrent malignant glioma. Cancer. 2004;100:605–611. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11949. doi:10.1002/cncr.11949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galanis E, Buckner JC, Novotny P, et al. Efficacy of neuroradiological imaging, neurological examination, and symptom status in follow-up assessment of patients with high-grade gliomas. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:201–207. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.2.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kornblith PL, Walker M. Chemotherapy for malignant gliomas. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:1–17. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.68.1.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tatter SB. Recurrent malignant glioma in adults. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2002;3:509–524. doi: 10.1007/s11864-002-0070-8. doi:10.1007/s11864-002-0070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:492–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708126. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0708126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367:645–648. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. doi:10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. doi:10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ignatova TN, Kukekov VG, Laywell ED, Suslov ON, Vrionis FD, Steindler DA. Human cortical glial tumors contain neural stem-like cells expressing astroglial and neuronal markers in vitro. Glia. 2002;39:193–206. doi: 10.1002/glia.10094. doi:10.1002/glia.10094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemmati HD, Nakano I, Lazareff JA, et al. Cancerous stem cells can arise from pediatric brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15178–15183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036535100. doi:10.1073/pnas.2036535100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galli R, Binda E, Orfanelli U, et al. Isolation and characterization of tumorigenic, stem-like neural precursors from human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7011–7021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1364. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. doi:10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor MD, Poppleton H, Fuller C, et al. Radial glia cells are candidate stem cells of ependymoma. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:323–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.001. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalerba P, Cho RW, Clarke MF. Cancer stem cells: models and concepts. Annu Rev Med. 2007;58:267–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.062105.204854. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.58.062105.204854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishii H, Iwatsuki M, Ieta K, et al. Cancer stem cells and chemoradiation resistance. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1871–1877. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00914.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altaner C. Glioblastoma and stem cells. Neoplasma. 2008;55:369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Hajj M, Becker MW, Wicha M, Weissman I, Clarke MF. Therapeutic implications of cancer stem cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.11.007. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jordan CT, Guzman ML, Noble M. Cancer stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1253–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061808. doi:10.1056/NEJMra061808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stiles CD, Rowitch DH. Glioma stem cells: a midterm exam. Neuron. 2008;58:832–846. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.031. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oldham S, Hafen E. Insulin/IGF and target of rapamycin signaling: a TOR de force in growth control. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00042-9. doi:10.1016/S0962-8924(02)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. Genetic pathways to primary and secondary glioblastoma. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1445–1453. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070011. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2007.070011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yap TA, Garrett MD, Walton MI, Raynaud F, de Bono JS, Workman P. Targeting the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway: progress, pitfalls, and promises. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:393–412. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.08.004. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. doi:10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakravarti A, Zhai G, Suzuki Y, et al. The prognostic significance of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway activation in human gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1926–1933. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.193. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.07.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu X, Pandolfi PP, Li Y, Koutcher JA, Rosenblum M, Holland EC. mTOR promotes survival and astrocytic characteristics induced by Pten/AKT signaling in glioblastoma. Neoplasia. 2005;7:356–368. doi: 10.1593/neo.04595. doi:10.1593/neo.04595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weppler SA, Krause M, Zyromska A, Lambin P, Baumann M, Wouters BG. Response of U87 glioma xenografts treated with concurrent rapamycin and fractionated radiotherapy: possible role for thrombosis. Radiother Oncol. 2007;82:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.11.004. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cloughesy TF, Yoshimoto K, Nghiemphu P, et al. Antitumor activity of rapamycin in a phase I trial for patients with recurrent PTEN-deficient glioblastoma. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050008. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang SM, Kuhn J, Wen P, et al. Phase I/pharmacokinetic study of CCI-779 in patients with recurrent malignant glioma on enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs. Invest New Drugs. 2004;22:427–435. doi: 10.1023/B:DRUG.0000036685.72140.03. doi:10.1023/B:DRUG.0000036685.72140.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang SM, Wen P, Cloughesy T, et al. Phase II study of CCI-779 in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Invest New Drugs. 2005;23:357–361. doi: 10.1007/s10637-005-1444-0. doi:10.1007/s10637-005-1444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng H, Ying H, Yan H, et al. p53 and Pten control neural and glioma stem/progenitor cell renewal and differentiation. Nature. 2008;455:1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nature07443. doi:10.1038/nature07443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bleau AM, Hambardzumyan D, Ozawa T, et al. PTEN/PI3K/Akt pathway regulates the side population phenotype and ABCG2 activity in glioma tumor stem-like cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.007. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fael Al-Mayhani TM, Ball SL, et al. An efficient method for derivation and propagation of glioblastoma cell lines that conserves the molecular profile of their original tumours. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;176:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollard SM, Yoshikawa K, Clarke ID, et al. Glioma stem cell lines expanded in adherent culture have tumor-specific phenotypes and are suitable for chemical and genetic screens. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:568–580. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.014. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gal H, Makovitzki A, Amariglio N, Rechavi G, Ram Z, Givol D. A rapid assay for drug sensitivity of glioblastoma stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358:908–913. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.020. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qiang L, Yang Y, Ma YJ, et al. Isolation and characterization of cancer stem like cells in human glioblastoma cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2009;279:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.01.016. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woltman AM, de Fijter JW, Kamerling SW, et al. Rapamycin induces apoptosis in monocyte- and CD34-derived dendritic cells but not in monocytes and macrophages. Blood. 2001;98:174–180. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.1.174. doi:10.1182/blood.V98.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pene F, Claessens YE, Muller O, et al. Role of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and mTOR/P70S6-kinase pathways in the proliferation and apoptosis in multiple myeloma. Oncogene. 2002;21:6587–6597. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205923. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bain J, Plater L, Elliott M, et al. The selectivity of protein kinase inhibitors: a further update. Biochem J. 2007;408:297–315. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070797. doi:10.1042/BJ20070797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang R, Banik NL, Ray SK. Differential sensitivity of human glioblastoma LN18 (PTEN-positive) and A172 (PTEN-negative) cells to Taxol for apoptosis. Brain Res. 2008;1239:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takeuchi H, Kondo Y, Fujiwara K, et al. Synergistic augmentation of rapamycin-induced autophagy in malignant glioma cells by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3336–3346. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fan QW, Knight ZA, Goldenberg DD, et al. A dual PI3 kinase/mTOR inhibitor reveals emergent efficacy in glioma. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.029. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun SY, Rosenberg LM, Wang X, et al. Activation of Akt and eIF4E survival pathways by rapamycin-mediated mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7052–7058. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0917. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maira SM, Stauffer F, Brueggen J, et al. Identification and characterization of NVP-BEZ235, a new orally available dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor with potent in vivo antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1851–1863. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0017. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vescovi AL, Galli R, Reynolds BA. Brain tumour stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:425–436. doi: 10.1038/nrc1889. doi:10.1038/nrc1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou J, Wulfkuhle J, Zhang H, et al. Activation of the PTEN/mTOR/STAT3 pathway in breast cancer stem-like cells is required for viability and maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16158–16163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702596104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702596104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hay N. The Akt-mTOR tango and its relevance to cancer. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.008. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu TJ, Koul D, LaFortune T, et al. NVP-BEZ235, a novel dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor, elicits multifaceted antitumor activities in human gliomas. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2204–2210. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0160. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Piccirillo SG, Reynolds BA, Zanetti N, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins inhibit the tumorigenic potential of human brain tumour-initiating cells. Nature. 2006;444:761–765. doi: 10.1038/nature05349. doi:10.1038/nature05349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ikushima H, Todo T, Ino Y, Takahashi M, Miyazawa K, Miyazono K. Autocrine TGF-beta signaling maintains tumorigenicity of glioma-initiating cells through Sry-related HMG-box factors. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:504–514. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.018. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang H, Tindall DJ. Dynamic FoxO transcription factors. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2479–2487. doi: 10.1242/jcs.001222. doi:10.1242/jcs.001222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Birkenkamp KU, Essafi A, van der Vos KE, et al. FOXO3a induces differentiation of Bcr-Abl-transformed cells through transcriptional down-regulation of Id1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2211–2220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606669200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M606669200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paik JH, Kollipara R, Chu G, et al. FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell. 2007;128:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.029. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:275–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc1590. doi:10.1038/nrc1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rich JN. Cancer stem cells in radiation resistance. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8980–8984. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0895. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang C, Ang BT, Pervaiz S. Cancer stem cell: target for anti-cancer therapy. FASEB J. 2007;21:3777–3785. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8560rev. doi:10.1096/fj.07-8560rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]