Abstract

Reinforcement, the strengthening of prezygotic reproductive isolation by natural selection in response to maladaptive hybridization [1, 2, 3], is one of the few processes in which natural selection directly favors the evolution of species as discrete groups [e.g., 4, 5, 6, 7]. The evolution of reproductive barriers via reinforcement is expected to evolve in regions where the ranges of two species overlap and hybridize, as an evolutionary solution to avoiding the costs of maladaptive hybridization [2, 3, 8]. The role of reinforcement in speciation has, however, been highly controversial because population-genetic theory suggests that the process is severely impeded by both hybridization [8, 9,10,11] and migration of individuals from outside the contact zone [12, 13]. To determine whether reinforcement could strengthen the reproductive barriers between two sister species of Drosophila in the face of these impediments, I initiated experimental populations of these two species that allowed different degrees of hybridization as well as migration from outside populations. Surprisingly, even in the face of gene flow, reinforcement could promote the evolution of reproductive isolation within only five generations. As theory predicts, high levels of hybridization (and/or strong selection against hybrids) and migration impeded this evolution. These results suggest that reinforcement can help complete the process of speciation.

Keywords: Speciation, isolating barriers, postmating-prezygotic isolation, reinforcement, artificial selection, experimental evolution

The process of reinforcement, or the strengthening by natural selection of prezygotic isolation between closely related taxa as an evolutionary response to maladaptive hybridization, was once seen as the inevitable last stage of speciation [14], but was later deemed to be extremely unlikely [15, 16]. Although its importance remains contentious [2, 3], reinforcement is supported by more recent data. Reinforcement is usually documented by observing a biogeographic pattern in which a reproductive isolating barrier is stronger in areas where two species overlap (“sympatric”) than in areas outside each other’s range (“allopatric”, [4–7]. But there are other explanations for such a pattern [17–19], and there has been little evidence that reinforcement can strengthen reproductive isolation in laboratory experiments [3, 20].

D. yakuba and its sister species D. santomea have several characteristics that make them ideal candidates for experimental studies of reinforcement. First, they hybridize within a well-demarcated hybrid zone [21,2] on the slopes of the African volcanic island of São Tomé. Second, I have previously found evidence suggesting that natural selection has acted in the wild to reduce maladaptive hybridization between these species: D. yakuba females from the hybrid zone show higher gametic isolation from males of D. santomea than do D. yakuba females from outside the hybrid zone. This elevated isolation in sympatric D. yakuba females results from their faster depletion of heterospecific sperm [7]. In contrast, there is no evidence for reinforced behavioral (sexual) isolation in the wild [7]. Third, when D. yakuba lines derived from allopatric populations are exposed to experimental sympatry with D. santomea and no hybridization is allowed (that is, when all hybrids are removed), there is an evolutionary increase in both behavioral and gametic isolation after only four generations [7]. Finally, both pure species and their reciprocal F1 hybrids are distinguishable by the degree of abdominal pigmentation [23, 24]. This morphological species difference allows experimentation on naturally collected isofemale lines (i.e., derived from a single wild-caught female) rather than on inbred mutant stocks whose hybrids are identifiable by their wild-type phenotype.

Taking advantage of these features, I created experimental “sympatry populations” (bottles that contained both D. yakuba and D. santomea) and allowed these populations to experience different degrees of selection against F1 hybrids as well as migration from “allopatric” bottles of flies. This models a natural situation in which two species with overlapping ranges produce hybrids. The disadvantage of these hybrids is taken to be a byproduct of evolution that occurred when their parental species were previously completely isolated geographically. Different numbers of F1 females in the population model different degrees of selection against the hybrids and hence in favor of reinforcement (in this case, selection imposed on the F1 hybrids was determined by the number of F1 females that were allowed to survive every). Varying levels of migration from stock bottles of the two species represent differential influx of migrants from allopatric populations.

To study the effect of migration on reinforcement, I allowed different levels of movement into the sympatry bottles of individuals from “allopatric” populations that were never exposed to the other species. These individuals were collected as virgins from stock bottles. The five different migration treatments involved transferring every generation either 0, 4, 8, 12 or 16 allopatric individuals (half virgin females, half virgin males) into the sympatry bottles. To vary the strength of selection against hybrids, I allowed different numbers of F1 hybrid females (easily identifiable by pigmentation) to survive each generation (F1 male hybrids were destroyed because they are sterile). There were five treatments, involving survival of 0, 4, 8, 14 or 20 female hybrids. Levels of migration were measured as the proportion of migrants per generation per species each generation (mpgps), and levels of hybridization were measured as the proportion of surviving F1 female hybrids in the population each generation (F1fh). In total there were 25 different combinations of migration and hybridization.

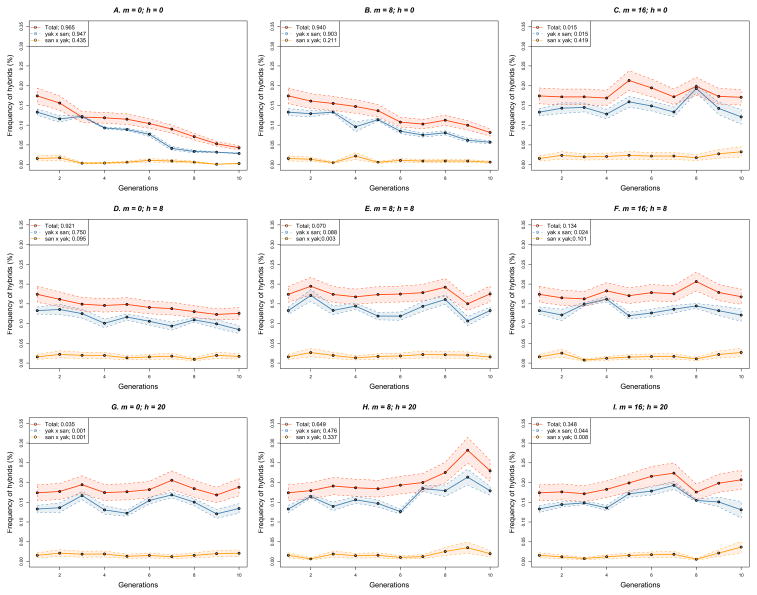

I estimated the effect of hybridization and migration on the population composition of species by determining how many F1 hybrids of both sexes appeared each generation in every experimental bottle. Treatments with low levels of migration and hybridization showed a reduction in the observed frequency of hybrids over time while those experiencing high levels of gene flow showed an increase in the proportion of hybrids (Figure 1). Both the amount of hybridization and of migration showed significant effects on the number of hybrids appearing in each treatment (LMM: hybridization, F1,71 = 282.0, p < 0.0001; migration: F1,71 = 264.3, p < 0.0001, interaction between factors: F1,1 = 52.2, p < 0.0001; Figure 3 and Figure S1). To establish what form of reproductive isolation caused the reduction in the number of F1 hybrids in those treatments in which migration and hybridization were low, I measured, after 5 and 10 generations of experimental sympatry, the levels of sexual and gametic isolation in the 25 treatments with different levels of hybridization and migration.

FIGURE 1.

Hybrid production in nine of the 25 experimental combinations of migration (m) and hybridization (h). Red lines represent the proportion of total hybrids for both reciprocal crosses observed in the experimental population. Blue lines represent the proportion of ♀yak × san ♂ hybrid males among all males in each population. yak × san hybrid males were used as a proxy for the total number of yak × san hybrids because it is not possible to distinguish san × yak and yak × san female hybrids. Yellow lines represent the proportion of ♀san × yak ♂ hybrid males among all males in each population. Dotted lines represent ± one standard error. Each regression line is shown with its r2 (i.e., coefficient of determination) in the legend. Treatments with low levels of hybridization and migration (A, B, D) showed a reduced frequency of hybrids over time (i.e., the evolution of reinforcement), while those having high levels of gene flow showed either no significant change (C, E, F, G) or an increase (H, I) in the proportion of hybrids over time (i.e., the breakdown of pre-existing reproductive isolation). Figure S1 shows the hybrid production for the other sixteen treatments.

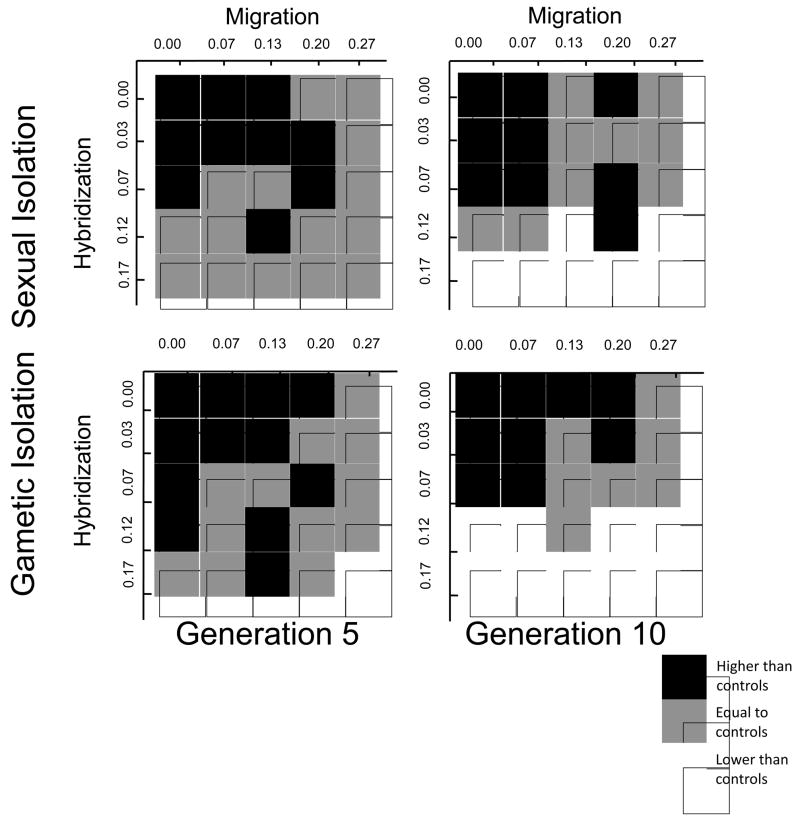

FIGURE 3.

Reproductive isolation (gametic and sexual) after five and ten generations of experimental sympatry in D. santomea females under different treatments of migration and hybridization. A, C. Sexual isolation. B, D. Gametic isolation. Key to colors: black: reproductive isolation (sexual or gametic) is significantly higher than control bottles (i.e., those not exposed to D. yakuba); grey: reproductive isolation is not significantly different from controls; white: reproductive isolation is significantly lower than controls. Different combinations of hybridization and migration levels produce substantial differences in the levels of reproductive isolation at generation 5 and 10.

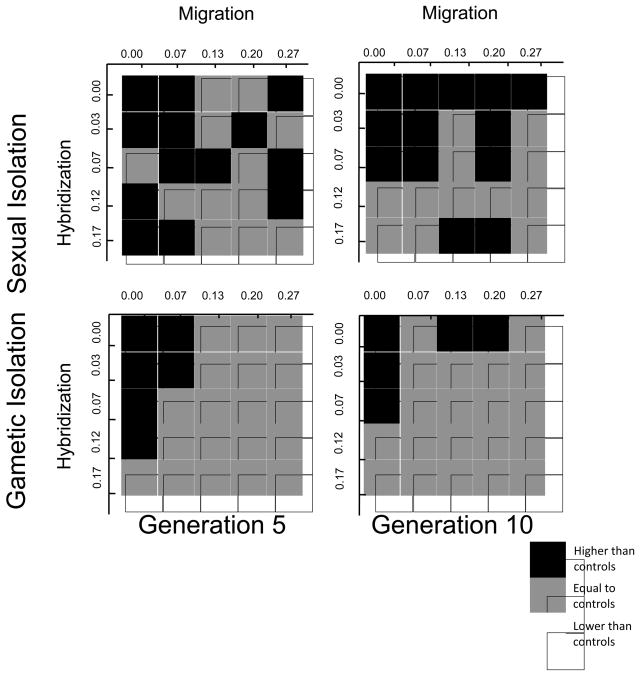

Females exposed to experimental sympatry from both species evolved increased sexual and gametic isolation within five generations, but only in those treatments in which levels of migration were fairly low and selection against F1 hybrids was strong. (Reinforcement for both gametic and sexual isolation required that migration be lower than 0.13% mpgps - the proportion of migrants per generation per species each generation- and hybridization be lower than 0.07 F1fh - the proportion of surviving F1 female hybrids in the population each generation-; Figure 1, Tables S1 and S2). After 10 generations, reinforced reproductive isolation in D. yakuba persisted in those treatments in which selection against hybrids was fairly strong, and in D. santomea when migration was low. (Reinforced sexual and gametic isolation in D. yakuba females evolved when hybridization was lower than 0.12 F1fh and migration was lower than 0.20 mpgps. Reinforcement of sexual and gametic isolation in D. santomea occurred when hybridization was lower than 0.12 F1fh and at several levels of migration, Figure 1, 2 Table S1–S2).

FIGURE 2.

Reproductive isolation (gametic and sexual) after five and ten generations of experimental sympatry in D. yakuba females under different levels of migration and hybridization. A, C. Sexual isolation. B, D. Gametic isolation. Key to colors: black: reproductive isolation (sexual or gametic) is significantly higher than control bottles (i.e., those not exposed to D. santomea); grey: reproductive isolation is not significantly different from controls; white: reproductive isolation is significantly lower than controls. Different combinations of hybridization and migration levels produce substantial differences in the levels of reproductive isolation at generation 5 and 10.

To analyze the influence of selection against hybrids and of migration on reproductive isolation, I fitted linear mixed models (LMM) for sexual and gametic isolation for D. yakuba and D. santomea separately [25] establishing what model best explained the heterogeneity on both types of reproductive isolation among treatments (combinations of different levels of hybridization and migration). The strength of sexual isolation in both species and gametic isolation in D. santomea after 5 generations of experimental sympatry was best explained by a model incorporating both main factors (migration and selection against hybrids, and the interaction term in gametic isolation in D. santomea) while heterogeneity in levels of sexual isolation in D. yakuba is best explained by a model that includes only migration (Table 1). On the other hand, after 10 generations, the full-factorial model better explained both types of reproductive isolation in both species (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Different levels of selection against F1 hybrids and migration yield differences in gametic and sexual isolation in D. yakuba and D. santomea after five and ten generations of experimental sympatry. To estimate the importance of each effect (migration, hybridization, interaction between migration and hybridization), I formulated four mixed-effect linear models that differed in their fixed effects, and in which differences among individuals within each replicates were considered random effects. To determine which model was more likely to explain the data, I used the AIC (Akaike Information Criterion [20]) scores of each model. The model with the lowest AIC for each type of reproductive isolation is highlighted in bold. See also Tables S1–S3.

| Generation 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. santomea | D. yakuba | |||

| Sexual Isolation | Gametic Isolation | Sexual Isolation | Gametic Isolation | |

|

selection + migration +interaction |

−498.52 | −3420.5 | −456.35 | −2233.85 |

|

selection + migration |

−516.23 | −3405.69 | −473.52 | −2243.5 |

|

selection |

−491.56 | −3412.57 | −457.39 | −1791.86 |

| migration | −512.1 | −3229.79 | −474.9 | −1751.46 |

|

Generation 10 | ||||

| D. santomea | D. yakuba | |||

| Sexual Isolation | Gametic Isolation | Sexual Isolation | Gametic Isolation | |

|

selection + migration +interaction |

−77.3 | −2094.98 | −225.67 | −561.44 |

|

selection +migration |

−42.65 | −2066.25 | −140.97 | −482.24 |

|

selection |

−4.87 | −1842.75 | 106.05 | 10.2 |

| migration | −11.73 | −1891.54 | −22.08 | −396.04 |

These results show that both the strength of selection against hybrids and the level of migration played a significant and substantial role in the evolution of both types of reproductive isolation. Not surprisingly, the strongest increase in isolation over time, compared to controls, was seen when selection was complete (that is when, all F1 hybrids were removed) and when there was no migration from allopatric areas. This kind of selection is sometimes called “reproductive character displacement” (RCD) rather than “reinforcement” since it mimics what happens when two species meet but postzygotic isolation is already complete—that is, when they are already good biological species. Nevertheless, in both species sexual and gametic isolation also increased significantly under low levels of migration and strong—but not complete—selection against hybrids (Figure 1); this situation corresponds to true speciation through reinforcement.

The magnitude of reproductive isolation within treatments showed changes in 85 out of 100 treatments between generation 5 and 10 (Table S3). In general, reproductive isolation increased in those treatments in which levels of hybridization and migration were low, and decreased in those treatments in which these two factors were high. In D. yakuba, regardless of the level of migration, high levels of hybridization (i.e., more than 0.12 F1fh) overwhelmed the effect of reinforcing selection, actually reducing the level of reproductive isolation below that seen in control bottles (Figure 1–2, Table 1, Tables S1–S3). This suggests that if the species boundary becomes more permeable (i.e., if there is not selection against female hybrids), the two species will collapse into a hybrid swarm.

This experimental design leads to two caveats. First, to allow gene flow between species, it demanded the survival of a constant number of F1 female hybrids each generation, except in those replicates which completely excluded hybrids. Maintaining constant numbers of surviving F1 females required varying the magnitude of selection against the hybrids, for as selection increased the reproductive isolation between species, fewer hybrids were produced. Accordingly, a greater fraction of produced hybrids were allowed to survive over time, which in turn meant that as selection succeeded its intensity decreased. The second caveat is that I was unable to control the number of surviving backcross flies in the population (and thus was unable to judge their impact on the evolution of reproductive isolation) because their pigmentation is often indistinguishable from that of pure-species individuals. Since I could not follow backcross flies, the number of surviving F1 hybrids is a proxy for—and not the exact value of—the amount of selection against hybrid genotypes. Given that females from backcrosses have similar levels of sexual and gametic isolation as do the pure-species females from the their father’s species (e.g., (san × yak) × yak and yak females have similar behavioral and gametic isolation levels as pure-species yak and san females; [26, 27]), this situation is a fairly good approximation to what happens when hybrid incompatibility is caused by a Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibility involving two (or more) epistatically-dominant factors (this is because the deleterious genic interaction occurs mainly in F1hybrids, and is rarer among backcross individuals because of recombination).

The results here shown raise additional questions about the evolution of reinforcement in the D. yakuba-D. santomea species pair. Natural populations of D. yakuba that are sympatric with those of D. santomea show stronger gametic isolation than do allopatric populations, implying reinforcement. Oddly, however, geography seems to have no effect on levels of sexual isolation. Yet this experimental study clearly shows that allopatric D. yakuba populations have genetic variation for sexual isolation that could form the basis for reinforced mate discrimination in the wild [7]. It is a mystery why we have not observed this in nature.

Additionally, I found that D. santomea also shows genetic variation for increased gametic and sexual isolation from D. yakuba males, but we have observed no reinforcement for either trait in the wild [7, 27]. This disparity between the laboratory and field results might reflect the greater proportion of D. santomea than D. yakuba in the hybrid zone on São Tomé, which would make selection for strengthened reproductive isolation on D. santomea weaker (the consequences of maladaptive hybridization are less severe in the more common species [2, 3]). Alternatively, since reproductive isolation with D. yakuba is already high in natural populations of D. santomea (reproductive isolating mechanisms measured under laboratory conditions reduce interspecific gene flow (compared to intraspecific controls) up to 93% for ♀ yak × san ♂ crosses and up to 98% for ♀ san × yak ♂ crosses, [22]), the selective pressure to increase reproductive isolation in D. santomea is weaker than in D. yakuba. And of course both the population-frequency and preexisting-isolation explanations are possible.

How do these results compare with previous work? Several earlier studies [7, 28, 29] examined mixed populations of two sister species of Drosophila to determine whether complete selection against hybrids could yield reproductive isolation. In these cases reproductive isolation evolved quickly. In all of these studies, however, no gene flow was possible since hybrids were completely eliminated (or were totally unfit) from populations each generation before reproduction. So while these studies demonstrated that artificial sympatry can indeed promote the rapid evolution of prezygotic isolation (both premating [7, 28, 29] and/or postmating-prezygotic [7]), the lack of gene flow meant that these studies were models not of reinforcement, but of reproductive character displacement, a post-speciation phenomenon. Related work includes experimental studies of sympatric speciation (divergence with gene flow). Sympatric speciation requires the evolution of mate discrimination in the face of o gene flow between the divergent populations [30–33]. These studies have demonstrated that assortative mating can evolve as a byproduct of a strong selection regime involving traits of potential ecological relevance. But these studies do not constitute a test of reinforcement because the increased reproductive isolation does not evolve as a way to avoid the fitness costs associated with postzygotic isolation (in sympatric speciation the reduction of gene flow and isolation between subpopulations evolves while they adapt to different habitats, not as a response to reduce the production of inferior hybrids [34,35]).

Mathematical theory has shown that the evolution of reinforcement depends critically on the amount of hybridization: with even small amounts of gene flow, populations fuse rather than becoming more isolated [2, 8, 9, 10, 36, 37]. This is because gene flow breaks up associations between alleles that can cause postzygotic isolation, between characters that can cause prezygotic isolation, and between characters that cause pre- and postzygotic isolation [3, 9, 11]. My experimental results confirm this conclusion: even moderate levels of gene flow, in the form of either hybridization or migration, overwhelmed the effects of reinforcing selection. This pattern was also seen in observations of Timema walking sticks in nature [38, 39]. Taken together, the results described here confirm theoretical formulations that reinforcement can be important in completing the speciation process especially when gene flow is not too high.

Other factors that might affect the probability of reinforcement remain to be studied; these include migration from the hybrid zone back to allopatric populations, which will eliminate the pattern of reinforcement by spreading it throughout allopatric populations; heterogeneity in habitat structure across the geographic range of a species; and population structure. But although these aspects of reinforcement remain unexplored, this study confirms that the process is at least a plausible factor in the final stages of speciation.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Reinforcement can help complete the process of speciation under certain circumstances, such as limited migration and strong—but not complete—selection against hybridization.

The evolution of reinforcement is impeded by high levels of hybridization (and/or strong selection against hybrids) and migration.

Populations of D. santomea and D. yakuba from areas outside each other’s range show genetic variation for increased gametic and sexual isolation from each other.

Supplementary Material

FIGURE S1. Total hybrids produced in 16 of the 25 experimental combinations of migration and hybridization. m = number of migrants allowed each generation per species; h = number of F1 hybrid females allowed to survive each generation. A. m = 0; h = 4. B. m = 0; h = 14. C. m = 4; h = 0. D. m = 4; h = 4. E. m = 4; h = 8. F. m = 4; h = 14. G. m = 4; h = 20. H. m = 8; h = 4. I. m = 8; h = 14. J. m = 12, h = 0. K. m = 12; h = 4. L. m = 12; h = 8. M. m = 12; h =14. N. m = 12; h = 20. O. m =16; h = 4. P. m = 16; h = 14). Red lines represent the proportion of total hybrids (i.e., from both reciprocal crosses) observed in the experimental population. Blue lines represent the proportion of yak × san hybrid males among all males in each population. yak × san hybrid males were used as a proxy for the total number of yak × san hybrids because it is not possible to distinguish san × yak and yak × san female hybrids. Yellow lines represent the proportion of san × yak hybrid males among all males in each population. Dotted lines represent ± one standard error.

TABLE S1. Pairwise comparisons (two-tailed Student’s t test) of levels of gametic and sexual isolation between controls (D. yakuba pure-species bottles) and D. yakuba females exposed to experimental sympatry with D. santomea for five and ten generations. Comparisons show that different levels of migration and hybridization significantly affected levels of sexual isolation in D. yakuba females. Probability values are in parentheses. Related to Figure 2.

TABLE S2. Pairwise comparisons (two-tailed Student’s t test) of levels of gametic and sexual isolation between controls (D. santomea pure species bottles) and D. santomea females exposed to experimental sympatry with D. yakuba for five and ten generations. Comparisons show that different levels of migration and hybridization significantly affected levels of gametic isolation in D. santomea females. Related to Figure 3

TABLE S3. Pairwise comparisons (One-way ANOVA) of levels of sexual and gametic isolation after five and ten generations of experimental sympatry in D. santomea and D. yakuba females. Comparisons between generations show that the magnitude of gametic isolation within treatments in both species sympatry changed significantly over time. Related to Figures 2 and 3.

TABLE S4. Number of flies (D. yakuba, D. santomea, F1 hybrids and migrants) used to initiate experimental sympatry populations. All replicates were started with 30 D. yakuba females, 30 D. yakuba males, 30 D. santomea females and 30 D. santomea males. I set up the sympatry conditions by collecting both sexes of D. santomea and D. yakuba, and F1 female hybrids and migrants from both species. yakmig: D. yakuba flies from stock bottles (never exposed to D. santomea). sanmig: D. santomea flies from stock bottles (never exposed to D. yakuba).

Acknowledgments

I thank J. A. Coyne, T. D. Price, D. Kennedy, M.A.F. Noor, M. A. Sprigge and N. Bloch for critical discussions; and I. A. Butler and J. Gladstone for technical help. This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grant R01GM058260 to Jerry A. Coyne.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dobzhansky Th. Speciation as a stage in evolutionary divergence. Am Nat. 1940;74:312–321. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Servedio MR, Noor MAF. The role of reinforcement in speciation: Theory and data. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 2003;34:339–364. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coyne JA, Orr HA. Speciation. Sinauer Associates, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rundle HD, Schluter D. Reinforcement of stickleback mate preferences: sympatry breeds contempt. Evolution. 1998;52:200–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1998.tb05153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saetre GP, Moum T, Bures S, Kral M, Adamjan M, Moreno J. A sexually selected character displacement in flycatchers reinforces premating isolation. Nature. 1997;387:589–592. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaenike J, Dyer KA, Cornish C, Minhas MS. Asymmetrical reinforcement and Wolbachia infection in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(10):e325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matute DR. Reinforcement of gametic isolation in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(3):e1000341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Servedio MR. Reinforcement and the genetics of nonrandom mating. Evolution. 2000;54:21–29. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Servedio MR, Kirkpatrick M. The effects of gene flow on reinforcement. Evolution. 1997;51:1764–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb05100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkpatrick M, Servedio MR. The reinforcement of mating preferences on an island. Genetics. 1999;151:865–884. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.2.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanderson N. Can gene flow prevent reinforcement? Evolution. 1989;43:1223–1235. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1989.tb02570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liou LW, Price TD. Speciation by reinforcement of premating isolation. Evolution. 1994;48:1451–1459. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1994.tb02187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caisse M, Antonovics J. Evolution in closely adjacent plant populations. Heredity. 1978;40:371–384. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobzhansky T. Genetics and the origin of the species. Columbia University Press; New York: 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spencer HG, Mcardle BH, Lambert DM. A theoretical investigation of speciation by reinforcement. Am Nat. 1986;128:241–262. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall JL, Arnold ML, Howard DJ. Reinforcement: the road not taken. Trends Ecol Evol. 2002;17:558–563. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard DJ. Reinforcement: origin, dynamics, and fate of an evolutionary hypothesis. In: Harrison RG, editor. Hybrid zones and the evolutionary process. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 46–69. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noor MAF. Reinforcement and other consequences of sympatry. Heredity. 1999;83:503–508. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6886320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Price TD. Speciation in birds. Roberts & Co. Publishers; Greenwood Village, CO, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harper AA, Lambert DM. The population genetics of reinforcing selection. Genetica. 1983;62:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Llopart A, Lachaise D, Coyne JA. Multilocus analysis of introgression between two sympatric sister species of Drosophila: Drosophila yakuba and D. santomea. Genetics. 2005;171:197–210. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.033597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Llopart A, Lachaise D, Coyne JA. An anomalous hybrid zone in Drosophila. Evolution. 2005;59:2602–2607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Llopart A, Elwyn S, Lachaise D, Coyne JA. Genetics of a difference in pigmentation between Drosophila yakuba and Drosophila santomea. Evolution. 2002;56:2262–2277. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carbone MA, Llopart A, deAngelis M, Coyne JA, Mackay TFC. Quantitative trait loci affecting the difference in pigmentation between Drosophila yakuba and D. santomea. Genetics. 2005;171:211–225. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.044412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinheiro J, Bates D. Mixed-effects models in S and S-PLUS. Springer; New York (New York): 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coyne JA, Kim SY, Chang AS, Elwyn S. Sexual isolation between two sibling species with overlapping ranges: Drosophila santomea and Drosophila yakuba. Evolution. 2002;56:2424–2434. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matute DR, Coyne JA. Intrinsic reproductive isolation between two sister species of Drosophila. Evolution. 2010;64:903–920. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koopman KF. Natural selection for reproductive isolation between Drosophila pseudoobscura and Drosophila persimilis. Evolution. 1950;4:135–148. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgie M, Chenoweth S, Blows MK. Natural selection and the reinforcement of mate recognition. Science. 2000;290:519–521. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thoday JM, Gibson JB. The probability of isolation by disruptive selection. Am Nat. 1970;104:219–230. doi: 10.1038/1931164a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thoday JM. Isolation by disruptive selection. Nature. 1962;193:1164–1166. doi: 10.1038/1931164a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rice WR, Salt GW. Speciation via disruptive selection on habitat preference: Experimental evidence. Am Nat. 1988;131:911–917. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rice WR, Salt GW. The evolution of reproductive isolation as a correlated character under sympatric conditions: experimental evidence. Evolution. 1990;44:1140–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb05221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bush GL. Sympatric speciation in animals: new wine in old bottles. Trends Ecol Evol. 1994;9:285–288. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diehl SR, Bush GL. In: Speciation and Its Consequences. Otte D, Endler J, editors. Sinauer; Sunderland, MA: 1989. pp. 345–365. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelly JK, Noor MA. Speciation by reinforcement: a model derived from studies of Drosophila. Genetics. 1996;143:1485–1497. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.3.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Servedio MR. The evolution of premating isolation: local adaptation and natural and sexual selection against hybrids. Evolution. 2004;58:913–924. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nosil P, Crespi BJ, Sandoval CP. Reproductive isolation driven by the combined effects of ecological adaptation and reinforcement. Proceedings Roy Soc Lond B. 2003;270:1911–1918. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nosil P. The role of selection and gene flow in the evolution of sexual isolation in Timema walking-sticks and other Orthopteroids. Journal of Orthoptera Research. 2005;14:247–253. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coyne JA, Orr HA. Patterns of speciation in Drosophila. Evolution. 1989;43:362–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1989.tb04233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coyne JA, Orr HA. “Patterns of speciation in Drosophila” revisited. Evolution. 1997;51:295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb02412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang AS. Conspecific sperm precedence in sister species of Drosophila with overlapping ranges. Evolution. 2004;58:781–789. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shapiro SS, Wilk MB. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples) Biometrika. 1965;52:591–611. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crawley MJ. GLIM for ecologists. Oxford (United Kingdom): Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1993. p. 379. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crawley MJ. Statistical computing: an introduction to data analysis using S-plus. Chichester (United Kingdom): Wiley; 2002. p. 761. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model selection and multimodel inference: A practical information-theoretic approach. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. http://www.R-project.org.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FIGURE S1. Total hybrids produced in 16 of the 25 experimental combinations of migration and hybridization. m = number of migrants allowed each generation per species; h = number of F1 hybrid females allowed to survive each generation. A. m = 0; h = 4. B. m = 0; h = 14. C. m = 4; h = 0. D. m = 4; h = 4. E. m = 4; h = 8. F. m = 4; h = 14. G. m = 4; h = 20. H. m = 8; h = 4. I. m = 8; h = 14. J. m = 12, h = 0. K. m = 12; h = 4. L. m = 12; h = 8. M. m = 12; h =14. N. m = 12; h = 20. O. m =16; h = 4. P. m = 16; h = 14). Red lines represent the proportion of total hybrids (i.e., from both reciprocal crosses) observed in the experimental population. Blue lines represent the proportion of yak × san hybrid males among all males in each population. yak × san hybrid males were used as a proxy for the total number of yak × san hybrids because it is not possible to distinguish san × yak and yak × san female hybrids. Yellow lines represent the proportion of san × yak hybrid males among all males in each population. Dotted lines represent ± one standard error.

TABLE S1. Pairwise comparisons (two-tailed Student’s t test) of levels of gametic and sexual isolation between controls (D. yakuba pure-species bottles) and D. yakuba females exposed to experimental sympatry with D. santomea for five and ten generations. Comparisons show that different levels of migration and hybridization significantly affected levels of sexual isolation in D. yakuba females. Probability values are in parentheses. Related to Figure 2.

TABLE S2. Pairwise comparisons (two-tailed Student’s t test) of levels of gametic and sexual isolation between controls (D. santomea pure species bottles) and D. santomea females exposed to experimental sympatry with D. yakuba for five and ten generations. Comparisons show that different levels of migration and hybridization significantly affected levels of gametic isolation in D. santomea females. Related to Figure 3

TABLE S3. Pairwise comparisons (One-way ANOVA) of levels of sexual and gametic isolation after five and ten generations of experimental sympatry in D. santomea and D. yakuba females. Comparisons between generations show that the magnitude of gametic isolation within treatments in both species sympatry changed significantly over time. Related to Figures 2 and 3.

TABLE S4. Number of flies (D. yakuba, D. santomea, F1 hybrids and migrants) used to initiate experimental sympatry populations. All replicates were started with 30 D. yakuba females, 30 D. yakuba males, 30 D. santomea females and 30 D. santomea males. I set up the sympatry conditions by collecting both sexes of D. santomea and D. yakuba, and F1 female hybrids and migrants from both species. yakmig: D. yakuba flies from stock bottles (never exposed to D. santomea). sanmig: D. santomea flies from stock bottles (never exposed to D. yakuba).