Abstract

Background

There is evidence that exposure to passive smoking in general, and in babies in particular, is an important cause of morbimortality. Passive smoking is related to an increased risk of pediatric diseases such as sudden death syndrome, acute respiratory diseases, worsening of asthma, acute-chronic middle ear disease and slowing of lung growth.

The objective of this article is to describe the BIBE study protocol. The BIBE study aims to determine the effectiveness of a brief intervention within the context of Primary Care, directed to mothers and fathers that smoke, in order to reduce the exposure of babies to passive smoking (ETS).

Methods/Design

Cluster randomized field trial (control and intervention group), multicentric and open. Subject: Fathers and/or mothers who are smokers and their babies (under 18 months) that attend pediatric services in Primary Care in Catalonia.

The measurements will be taken at three points in time, in each of the fathers and/or mothers who respond to a questionnaire regarding their baby's clinical background and characteristics of the baby's exposure, together with variables related to the parents' tobacco consumption. A hair sample of the baby will be taken at the beginning of the study and at six months after the initial visit (biological determination of nicotine). The intervention group will apply a brief intervention in passive smoking after specific training and the control group will apply the habitual care.

Discussion

Exposure to ETS is an avoidable factor related to infant morbimortality. Interventions to reduce exposure to ETS in babies are potentially beneficial for their health.

The BIBE study evaluates an intervention to reduce exposure to ETS that takes advantage of pediatric visits. Interventions in the form of advice, conducted by pediatric professionals, are an excellent opportunity for prevention and protection of infants against the harmful effects of ETS.

Trial Registration

Clinical Trials.gov Identifier: NCT00788996.

Background

Environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) consists of a mixture of smoke produced by the burning of cigarettes and the smoke directly exhaled by smokers. A large part of the smoke that is inhaled by a passive smoker is made by the burning of cigarettes, which contains certain toxic components at levels far above those inhaled by the actual smoker. It has been shown that the levels of nicotine and tar produced by burning cigarettes are three times higher than in the smoke directly exhaled by smokers, and the concentration of carbon monoxide (CO) approximately five times higher [1]. In addition, the spontaneous burning of cigarettes produces smaller particles that are able to penetrate deeper areas of the lungs [2].

Since the milestone publication by Doll and Hill in 1950, it has been known that tobacco is harmful to health [3], but until 1974 no one had talked about smoking in fathers/mothers, ETS and the consequences for children. Currently, we have evidence [4] that the smoking in parents is associated with various adverse effects on infant health: increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome [5], acute respiratory diseases, respiratory symptoms, aggravation of symptoms in patients with asthma, acute and chronic diseases in the middle ear and slowed lung growth [6,7]. Passive smoking is the leading cause of preventable death in infancy in industrialized countries (third cause of preventable death in adults). According to the International Agency for the Research on Cancer (IARC) of the World Health Organization (WHO), second hand smoke is a type A carcinogen [8]. Furthermore, the WHO MPOWER report [9] proposes suggestive evidence between environmental exposure to tobacco smoke and the following diseases: leukemia, lymphoma, brain tumors and asthma. It is particularly worrying in younger children because they are dependent on adults and therefore cannot avoid exposure to tobacco smoke; moreover, their immune systems are underdeveloped.

In Spain, the law on tobacco control measures (28/2005) has led to notable progress in reducing ETS in work places and in increasing the awareness of the damage caused by ETS [10]; however, at the same time this law has made the home one of the few places where people can smoke [11]. As an example of the exceptions and contradictions of the Spanish law, in "small" places of entertainment (less than 100 square meters) such as bars and restaurants, the owners can decide whether or not to apply a smoke-free policy. Preliminary estimates indicate that 90-95% of small establishments have opted to allow smoking, furthermore, the Spanish law permits the access of children who go in the company of their parents [12]. In Catalonia, various interventions have been carried out to reinforce smoking cessation during pregnancy [13,14]. ETS has the greatest effect on the health of children under the age of five, given that this group of individuals tends to spend the most time at home, making them the most vulnerable to the effects of passive smoking [15-17]. There are few studies on measures to reduce ETS in the home [18]. Various studies have shown that the potential for tobacco pollution at home is more significant than levels of atmospheric contamination. Nonetheless, up to 75% of mothers that smoke expose their newborns to smoke, and between 47-60% of their babies present significant levels of urinary cotinine [19,20].

Interventions to reduce passive smoking have obtained irregular results [21-26]. The Cochrane review [27] on the subject states that there is no sufficient evidence to support any one intervention's effectiveness in reducing smoking habit in parents and the exposure in children. Various studies have established that the level of nicotine in hair is a good quantitative indicator to measure the environmental exposure of tobacco smoke [28-32].

Health education messages from pediatric professionals are an excellent opportunity and, in general, are well accepted by parents since they make reference to the health of their son or daughter. Brief interventions, according to the context and impact of the content, can be just as effective as more intensive interventions [33]. Studies about this type of intervention have not been published in our country.

It is important to conduct methodologically sound studies with a more appropriate design (especially in the calculation of the sample size and monitoring) and evaluation through objective measure of results, such as the level of nicotine in hair.

Objectives

The principle objective of the BIBE study is to determine the effectiveness of a brief intervention directed at fathers and/or mothers that smoke in order to reduce ETS in babies, in the context of pediatric visits in primary care.

The secondary objectives of the BIBE study are to determine if this intervention produces changes in the tobacco consumption of the parents and subsequently, to study the concordance between the subjective measures of ETS and the objective measures (questionnaire versus biological analysis of nicotine in hair).

The specific objective of this article is to describe the protocol of the BIBE study.

Methods/Design

Study design

Multi-centric, open cluster randomized field trial. Unit of randomization: Primary Care teams formed by a pediatrician and a pediatric nurse, both responsible for the same infant population.

Setting

Pediatric Primary Care consultations in Catalonia. All of the basic health areas of Catalonia will be offered participation through the xarxa de centres sense fum (network of smoke free centers).

Study period

The preparation and pilot test period: during 2008

Data collection period: March-December 2009. The period is not coincidental; the first recruitment visit is in spring and the six-month control visit in the fall, in order to compare the degree of exposure in a similar climate period.

Study population

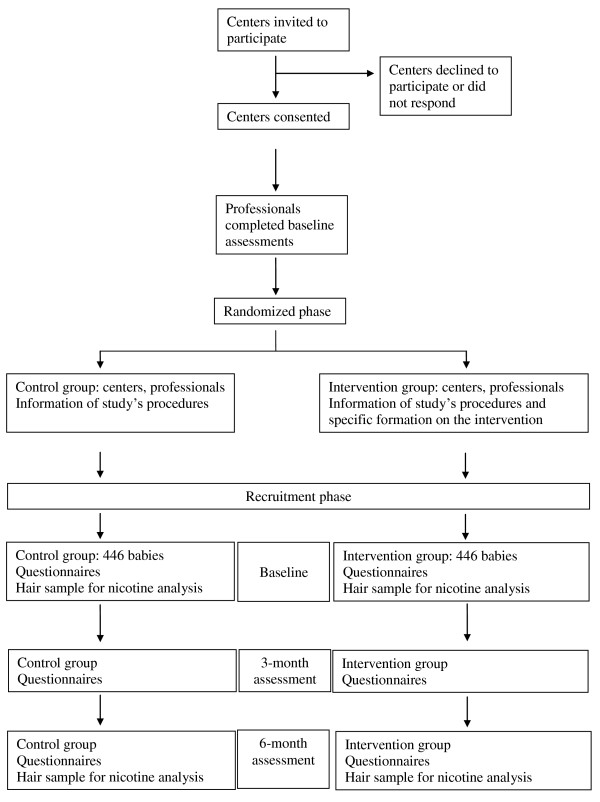

The study subjects are babies under 18 months of age at the time of recruitment, with a mother and/or father that is an active smoker and that attend a pediatric consultation (with the doctor or nurse) in Primary Care for a check-up visit. Figure 1 shows the diagram flow of the study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the BIBE study. Diagram and flow chart of the BIBE study.

Sampling strategy

During the two-month recruitment period, and until obtaining the eight proposed cases in each team, all of the mothers and/or fathers that visit with a baby under the age of 18 months will be asked whether or not they are smokers.

Inclusion criteria

Babies under 18 months of age whose parents answer affirmatively to the question "Do you or your partner smoke?" and who give their informed consent to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

- Any pathology or condition that makes inclusion/follow-up difficult at three and six-months (at the professional's criteria), for example parent or baby with an active, acute disease, known addiction in the parents to other substances or foreseeable change in residency.

- Parent in smoking cessation process at the recruitment phase of the study.

- Refusal of parents to participate in the study.

Sample size

Based on the data from the pilot study in 46 babies and using the same analysis technique of nicotine in hair used in the present study, a mean of 6.83 ng/mg and a standard deviation of 8.88 ng/mg have been obtained. Assuming a mean difference of 30% between the intervention group and the control group in nicotine in hair at the end of the intervention, with an alpha value of 0.05 and a power of 80%, 295 subjects are needed in each group. If we assume a loss of 20%, the sample size increases to 708 (354 in each group). It is considered feasible for each basic care unit to recruit eight babies in a period of two months. The estimates of the intra-cluster correlation coefficient in cluster randomized trials that evaluate the implementation of clinical practice guidelines using outcome variables in primary healthcare are generally less than 0.05 [34]. These intra-cluster correlation coefficients translate to a cluster size of eight in a design effect corresponding to a factor of 1.4. Therefore, the final simple size will be 992 babies (446 in each group).

Data collection procedures

There will be three visits with each baby included in the study in both, control and intervention group: a visit at the start of the study (recruitment) and two follow-up visits, at three and six months after the recruitment visit (Figure 1).

The father and/or mother will be asked to provide, using an electronic data collection system created for the study, data regarding the following:

1-The baby: age, sex, breastfed/artificial milk, living nucleus, medical history and clinical data for follow-up,

2- The parents: age, sex, socio-demographic data, smoking status (yes or no). In smokers, data on the smoking habit, smoking behavior during pregnancy and whether or not the baby was breastfed, behavior during breastfeeding. Finally, smoking behavior changes during the study.

3-The degree of exposure of the baby to ETS, within and outside of the home, will be based on the questions proposed by clinical practice guidelines [13,14,35,36].

In order to measure the levels of biological nicotine in hair, a sample of the baby's hair will be taken at the first (recruitment) visit and at the last (six-month) visit. A lock of hair will be cut from the root and once collected, will be placed on a card and put into an envelope, which will be provided with the study materials (Additional files 1 and 2).

For the secondary objective, change in smoking habit in the father and/or mother, expired carbon monoxide will be measured in those that declare smoking abstinence during the study period. Cut off point: 10 ppm.

Description of laboratory analysis technique

Measuring nicotine in hair provides better information about average or long-term exposure to ETS as compared to other biological markers such as cotinine in the urine, saliva or blood, which have a shorter retrospectivity [28-32,37]. As hair grows in average at a rate of one centimetre per month, nicotine concentrations found in a segment of hair are related to the exposure during a period of time depending on the distance from the root. It is a specific biological indicator, sensitive, stable over time and temperature, not influenced by specific exposures prior to the analysis and easy to obtain [38,39]. The same IMIM team, with broad experience with the technique, analyzed all the samples. The analytical procedure of nicotine in hair utilizes ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) using a triple quadrupole instrument. The hair samples (several milligrams) are extensively washed with dichloromethane to eliminate any superficial contamination. Then hair samples are dissolved in an alkaline (1 M potassium hydroxide) solution. The nicotine released from the matrix of hair is extracted using dichloromethane and an aliquot directly analyzed chromatographically using an HILIC column. Detection by mass spectrometry: monitoring the transition between the pseudo molecular ion ([M+H]+ a m/z 163) and the fragment at m/z 117. The procedure uses a deuterated internal pattern D4-nicotine, which monitors the equal transition (m/z 167-- > 121). The established limit of quantification is 0.5 ng (nanogram) of nicotine in the sample (e.g. 0.05 ng/mg in 10 mg simple).

Description of the intervention

Once the teams have shown interest in collaborating in the study, the participating teams will be randomly assigned by clusters to the intervention or control group, as specified in the methodology.

There will be three visits (at the start of the study, at three and six months after inclusion in the study for each baby included in the study (control and intervention group). These visits will be used to collect necessary information.

The teams included in the intervention group will be given a two-hour specific training on passive smoking, epidemiology, morbimortality and how to intervene in the reduction of ETS. The proposed intervention is based on interventions recommended in primary care that follow international and national clinical practice guidelines [13,35,36]. The intervention is based on counseling, cognitive theory and motivational interviewing.

Thus, this study is proposing a passive smoking intervention that has been adapted from an intervention that has been shown to be effective in decreasing active tobacco consumption in Primary Care.

The intervention aims to give parents that smoke brief information that emphasizes the health benefits that reducing ETS can have on their children. The basic elements of the intervention include:

1. Ask: whether or not there is a smoker that lives with the baby. If the answer is affirmative, the baby's level of exposure will be asked.

2. Assess knowledge: Information that the parents have about the effect of passive smoking in infancy.

3. Personalized information depending on the exposure and the perceived risk.

4. Ask about suggestions to make changes: support any efforts to modify exposure to ETS and discuss the problems this entails.

5. Personalized help and advice according to exposure, baby's background, perceived risk and parents' attitude towards making changes. This intervention will be reinforced with educational leaflets about passive smoking in infancy designed for the study (Additional file 3).

6. Congratulate if the mother and/or father has quit smoking during the pregnancy and support-encourage continued smoking cessation.

7. Support and encourage those that decide to quit smoking or reduce tobacco consumption.

The control group teams will conduct the three proposed visits during the six-month follow-up period. Aside from collecting the study variables, the control group will carry out the protocol's habitual care for a healthy child during the corresponding visits. In Catalonia, these visits are officially scheduled and include a generic reference to avoid exposure to air polluted by cigarette smoke; however, there is no specific protocol for action.

Database

The database will be obtained from medical records, questionnaires (interviews or visits), biological hair samples from the babies in the first visit and from expired carbon monoxide (CO) of parents that claim to have quit smoking.

Follow-up period

The follow-up period is six months from the start of the intervention.

A visit will be conducted by the pediatrician/nurse at three and six months after the start of the study. They will register the parents' tobacco habit and the level of ETS exposure obtained by a questionnaire (at three and six months) and the nicotine in hair (at six months).

Statistical analysis

Statisticians from the University of Girona's Research Group in Statistics, Applied Economics and Health (GRECS) will carry out the statistical analyses. These statisticians will have an advisory role.

The data will be incorporated into a database constructed using SPSS version 15.0. The descriptive analyses, as well as the statistical hypothesis testing, will also be conducted with this program. For subsequent modeling, the Free R software (version 11.0 or later) will be used.

All of the known potential confounding factors will be measured at the beginning of the study, including the caretaker who smokes (and the stage of change), level of education, marital status, breastfeeding and other members of the household, overcrowding. Therefore, the control and intervention group comparisons will be carried out both adjusted and unadjusted for these known confounders.

The simple treatment effect without adjusting the rates, relative risks and the 95% confidence intervals will be obtained in the first case, with a subsequent adjusted multiple regression analysis for other variables. Two forms of regression analysis will be taken into account for the primaries.

Expected results: A Poisson regression analysis and a negative binomial if there is evidence of over or under dispersion. The analysis of the secondary results will be carried out using standard statistical procedures applicable to categorical or continuous data. An adjustment for protocol analysis will also be conducted to verify the robustness of the results. All tests of significance will be two-tailed. For the treatment effects, sensitivity analyses will be conducted to determine the effect of the missing data.

The analysis will be done following the following study phases:

1. Describe the effect in both groups:

Initially an analysis of baseline comparability will be carried out in relation with the study variables. The following step will be to estimate the effect on the response variables without adjusting for other variables. To perform the above analyses, chi-squared tests will be used for qualitative variables and comparison of means for quantitative variables.

2. To estimate the adjusted effect, a multivariate multilevel model will be used. The dependent or principal variable is the child's exposure using the measure of nicotine in hair. The baby's age and sex, as well as the variables that have been shown to be statistically significant, will be included in the bivariate analyses. The basic care unit and the individual will be the levels in the multilevel analysis.

3. Concordance between the filled questionnaire and the nicotine collected in the hair: a summary evaluation of the questionnaire on a discrete, quantitative scale based on the data that is provided by the number of smoking cohabitants, the number of cigarettes that they smoke and the exposure time outside of the home. Pearson's (or Spearman's depending on the distribution) correlation coefficient will be calculated between the estimate and the result obtained in the nicotine hair analysis. The intraclass correlation coefficient will also be studied between both measures. Finally, both estimates will be dichotomized (questionnaire and nicotine in hair analysis) into two categories (exposed/not exposed) and the Kappa coefficient between the two will be calculated.

In all cases a bilateral alpha error of 0.05 and a 95% confidence interval will be used. To complete the explicit information, the comparison of means will be performed using a Student's t-test for parametric variables and the U Mann-Whitney test for non-parametric variables.

Results

Primary results to obtain:

Reduction of exposure to ETS measured at the beginning of the intervention (recruitment phase) and at six months, using a questionnaire that includes information about ETS history during pregnancy and breastfeeding, exposure to ETS within and outside of the home, family smoking habits and measures used to avoid exposure. To develop this questionnaire, questionnaires used in similar studies have been adapted (varying some items, based on the results of the pilot study). As an objective measurement of the exposure: biological levels of nicotine in hair of babies. All of the hair samples (from the pilot test and the definitive study) will be analyzed by the same team at IMIM.

Secondary results to obtain:

- Reduction or cessation of smoking habit in parents, measured using a questionnaire about status of the smoker/ex-smoker/non-smoker and using the Fagerström Nicotine Dependence Test in those that smoke, as well as the stage of change (pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, finalization). In smokers that declare smoking abstinence, the amount of carbon monoxide in expired air will be determined (Smokerlyzer). Cut-off point: 10 ppm.

-Other variables using questionnaire/clinical records, including data related to:

Type of professional that performs the intervention: pediatrician, pediatric nurse or both.

The baby: age, sex, breastfeeding, medical history, living nucleus.

The father and/or mother that attends the visit: age, sex, marital status, socioeconomic situation.

Parents' level of knowledge and their level of risk perception to exposure.

Quality control

Several procedures have been employed to ensure the quality of the study data, maximizing the validity and reliability of the data obtained and of the evaluation of the results: These are:

-Written documentation: electronic and printed copies of protocols, models and outlines of informed consent stored together. All written documentation, including the leaflets given to participants, have been created according to a standard model and have been subject to the approval of local institutional ethics committees.

-A pilot study has been conducted to reveal deficiencies in the study design.

-An informational meeting will be held for both the intervention and control group to distribute documentation and to explain and materials.

-Learning: All of the intervention group professionals will receive the same two-hour workshop on passive smoking, attributable morbimortality and how to reduce exposure to ETS.

-Meetings will be held and regular emails will be sent regularly between the members that lead the study and all of the participants from the centers.

Ethical aspects

The study and its successive revisions are adapted to the criteria of the Helsinki Declaration, as well as to the Guidelines to Good Clinical Practice. The protocol has been reviewed and approved by the CEIC" Clinical Research Ethics Committee" of the Jordi Gol and Gurina Foundation for the Promotion of Research in Primary Care (IDIAP Jordi Gol), with the number P08/50 "BIBE".

In regards to parents' informed consent, the information is provided verbally and written to all participants. Individuals in the study will have the opportunity to resolve doubts about study details. The written consent states that the study follows the law contained in the Helsinki Declaration and in Title I, Article 12 of the Royal Spanish Decree 561/1993 from April 16th, 1993.

Data confidentiality: Participants will be informed that data will be treated with absolute confidentiality according to the organic law that regulates the confidentiality of computerized data (Organic law 5/1992), and that data will be used exclusively for the objectives of the study.

Voluntary withdrawal: A mother or father can voluntarily withdraw his or her baby from the project at any point without having to give an explanation. He or she also has the right to ask that their personal data be eliminated from the records at any point, as well as for the results of their interviews.

Limitations

The following limitations have been taken into consideration:

Professionals, rather than subjects (babies) will be randomized. Although this reduces the variability of the sample studied, it is necessary in order to minimize the possibility of contamination between groups.

The intervention will be carried out only in parents that visit the centers that are being studied, thus excluding a group of people that use other care services or that do not attend scheduled appointments. This phenomenon is present in normal clinical conditions, and the research team wants to show utility and feasibility in normal conditions, such as the ones taken into consideration in this design.

There could be a contamination effect in the control group due to the pre-test and the feeling of being observed during the study.

Intervention to prevent exposure to ETS will be carried out on the person who attends to the primary care consultation, therefore it can influence smoking status or not. For instance, the response to the intervention to prevent ETS exposure to babies could be greater or lesser according to the smoking status of the person. To estimate the possible effect of this phenomenon we will collect the status of tobacco consumption of the caretaker as well as of the other persons living with the child.

Discussion

Exposure to ETS is an avoidable factor related to infant morbimortality. Interventions to reduce exposure to ETS in babies are potentially beneficial for their health.

As discussed in the introduction, increased exposure is declared in places not included in the Spanish tobacco law 28/2005. This justifies the need to define and promote a pediatric program in Primary Care that includes awareness interventions in the family environment, in places not included in the law (bars and cafes) or places that cannot be regulated because they belong to the private sphere (homes and cars), in order to achieve processes of change and protect infants.

The BIBE study evaluates, in real conditions, an intervention to reduce exposure to ETS that takes advantage of pediatric visits. The intervention that is proposed in the BIBE study aims to impact the attitude and knowledge of parents regarding ETS. Interventions in the form of advice, conducted by pediatric professionals, are an excellent opportunity for prevention and protection of infants against the harmful effects of ETS. In our country, health centers have almost universal coverage, including all social classes and situations. In fact, if the study proves to be effective it would also be efficient, since the intervention uses the same professionals that are responsible for the routine care of newborns.

Based on the bibliography, more research in passive smoking that uses objective measures of evaluation is necessary. Such research will generate evidence on the information that we are interested in collecting in order to learn children's exposure to cigarette smoke. It will also help to identify which intervention is effective in reducing this exposure. This is what we aim to do in the BIBE study.

Abbreviations

BIBE: Brief Intervention in babies. Effectiveness; PS: Passive smoking; ETS: Environmental tobacco smoke.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

GO was responsible for the conception and design of the study, conceived and participated in the design of the questionnaires, led the development of the program and the training and wrote the firsts drafts and final version of the study protocol. CC, CM, JB, ED, JL, LR, CM, CC, ES, AV, and MJ contributed to the design and development of the study and the questionnaires, as well as to the writing and development of the protocol. They have also contributed to the development of the program and the training. MS and MB were responsible for the statistical design of the protocol, the randomization and the statistical analysis of the pilot study data. JP and RP analyzed hair concentrations of nicotine.

The associated researchers contributed to the field work: recruitment, interview and collection of hair samples. Those in the intervention group have contributed to the development of the intervention protocol.

All authors have performed a critical revision of this manuscript and the final version.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Image 1. Cut a lock of the hair. Images showing how to cut a lock of baby's hair.

Image 2. Sample of the baby's hair to label and send. Image of a sample of baby's hair that was used to analyze nicotine concentration.

Image 3. Leaflet: Passive smoking: advice to decrease exposure in babies. Image showing a leaflet in Catalan which contains correct and incorrect advices for parents to reduce baby's exposure to environmental tobacco smoke.

Contributor Information

Guadalupe Ortega, Email: Guadalupe.ortega@gencat.cat.

Cristina Castellà, Email: cristinacastella@hotmail.com.

Carlos Martín-Cantera, Email: Carlos.Martin@uab.es.

Jose L Ballvé, Email: ballvejl@gmail.com.

Estela Díaz, Email: estela.diaz@gencat.cat.

Marc Saez, Email: marc.saez@udg.edu.

Juan Lozano, Email: jlozano@camfic.org.

Lourdes Rofes, Email: lrofes@grupsagessa.com.

Concepció Morera, Email: cmorera.girona.ics@gencat.cat.

Antònia Barceló, Email: antonia.barcelo@udg.edu.

Carmen Cabezas, Email: carmen.cabezas@gencat.cat.

Jose A Pascual, Email: jpascual@imim.es.

Raúl Pérez-Ortuño, Email: rperez@imim.es.

Esteve Saltó, Email: esteve.salto@gencat.cat.

Araceli Valverde, Email: araceli.valverde@gencat.cat.

Mireia Jané, Email: mireia.jane@gencat.cat.

Acknowledgements

The study was awarded a grant (CNPT0701) by the National Committee for the Prevention of Tobacco (CNPT), which enabled the pilot study in nine centers, as well as the preparation, design and graphic editing of the definitive study materials.

The analysis of nicotine in hair in the 46 babies in the pilot study and the intervention group reinforcement leaflet were financed by the General Directorate of Public Health, Generalitat de Catalunya.

The study has also been awarded a publication grant for the protocol by the Barcelona's Unit of Research Support for Primary Care of the IDIAP Jordi Gol.

The study has also received the support from the Primary Care Foundation of CAMFic and IDIAP Jordi Gol.

The authors thanks:

All members of the Primary Care Sin Humo (Smoke-Free) program that collaborated in the diffusion of the project in their Primary Care centers.

The scientific comments of Neus Altet and Jesus Almeda in the previous version of the manuscript.

The help received from the linguistic service of the Department of Health, Generalitat de Catalunya, especially Elena and Cristina for the correction of the materials and their contributions.

The management of the nine health centers that participated in the pilot study: ABS Badalona-Montigalà; ABS Badalona-Martí i Julià; ABS Badalona-Morera; ABS Badalona-Nova Lloreda; ABS Banyoles; ABS Montgat-Tiana; ABS L'Hospitalet-Florida; ABS Cornellà-St. Idelfons and ABS Vila-Seca.

The IDIAP Jordi Gol, for financing the translation of the study protocol.

Elisa Puigdomènech from the Grup de Recerca en Estils de Vida de la IDIAP Jordi Gol for the collaboration on the last versions of the manuscript and its submission to the journal

We also thank all the participants of the BIBE group:

BIBE Project Investigators:

Alt Pirineu i Aran: Antonia Parra de la Cruz Ester Prat i Gallart Elena Alcover Bloch.

Lleida: Ma Dolores Martínez Gracia, Rosa Gloria Jove Dolcet, Yolanda Pascual Arrazola, Laura Lanaspa Serrano, M. Jesús Fernández Galán, Maria Adelina Albana Mola, Mercè Lozano Vergara, Dolors Macià Penella, Ramon Capdevila Bert, Mireia Biosca Pàmies, Ma Encarnación Domènech Bonilla, Núria Yolanda Palencia Prats, Olga Diez Zaera, Susana Pérez Osuna, Maria Luisa Moreno Gonzalez, Ma Pilar Salillas Larruy, Laura Comabella Alzuria, Carles Gatius Tonda, Silvia Prado Muñoz, Amparo Blanch Guillen, Mercè Giribet Folch, Ma Carmen Cañameras Serrado, Julia Jové Naval, Maria Belen Garriga Figueres, Ma Del Mar Bafalluy Melé, Ramon Anguera Farran, Mercè Pollina Pocallet, Ma Mercè Segura i Serra, Maria Dolors Andreu Duat, Laura Marimon Gabernet, Rosa-Nicolasa Masot Recha, Lidia Sanz Borrell.

Camp de Tarragona Jaume Andreu Jornet, Elena Roselló Cavallé, Núria Sanz Manrique, Margarida Borràs Martorell, Susana Vidal Piedra, Isabel M. Canovas Garcia, Susana Gil Mancha, Raquel Morales Mora, Maria Domingo Fuster, Montserrat Pérez Pérez, Virginia Buj Dell'Abate, Montserrat Bosch Seró, Ana Maria Marín Pellicer, Enriqueta Lorente Ten, Àngels Vidal Tomàs, Isabel Soler Galera, Ana Reyes Curto, Rosalia Bocanegra Capilla, Lola Alcañiz Rodríguez, Ma Pilar Machado Solanas, Amparo Boix Fonollosa, Francisco Jose Sanchis, Morales Gabriela Ricomá Castellarnau, Anabel Salazar García, Rosa M. Olivé Vilella, Núria Mélich Teruel, Maria Isabel Noguera Vilà, Francesc Bobé Armant, Montserrat Ferré Guri, Antonieta Albareda Puig, M. Carmen Fontgivell Yeste, Eva Ma Esteruelas Alvarez, Mey-Lan Hernàndez Lau, Diana Marcela López Cubillos, Aroa Baudoin García, Ma Otilia Rodriguez Canals, Rosa Maria López Fraile, Susana Mora Herrera.

Terres de l'Ebre Irene Gómez Pérez, Jaume Miquel Salsas, Maria del Roser Bautista Castells, Sònia Ponce López, Emili Marques Soler, Susana Nadela Lapeira, Gracia Garcia Bernal, Miquel Navarro Robles, Elvira Dealbert Ramos, MaJosefa López Sánchez, Ma Guadalupe Vélez Cervera.

Girona: Joaquima Serrat Trias, Gustavo Daniel Egües Cachau, M.Angels Bosch Juscafresa, Marta Bustins Pastoret, Anna Coll i Nogué, Liannet Estrada Fernandez, Isabel Mascaró Casanovas, Meritxell Parés Rodà, Isabel Pelegrin López, Anna Fàbrega Riera, Noemi Roura Merino, Maria Lluïsa Ribas Casals, Montserrat Mallol Guisset, Maria Dolores Gonzalez Forcadell, Marta Mas Parareda, Montserrat Armangué Marquez, Isabel Bentué Dabau, Antonia Ramirez Prados, Gemma Vila Buch, Rosa Blanca Cortés, Marina Anna Moyà Martínez, Immaculada Jou Solés, Silvia Mir Mercader, Joana Casellas Garcia, Josefina Aleñà Torrent, Iratxe Olabegoya Estrela, Sonia Farran Farré, Alexandre Harb Birani, Ester Masó Monells, Roser Teixidor Feliu, Imma Sau Giralt, Ma Antonia Sabench Suriñach, Eugenia del Valle Olmos Sanchez.

Catalunya Central: Nuria Rosell Soler, Ma Josep Bernat Lopez, M. Angels Tarrés Gol, Rosa M. Soler Vila.

Barcelona: Pilar Oria Floria, Esther Guardia Gil, M. Angels Peris Morancho, Antoni Crous Xaubet, Pilar Ma Esteras Casanova, Lucelly Gómez García, Miriam Pascual Jiménez, Ma Mercè Vilallonga Fàbregas, Mercè Llopis Cantons, Carlos Moreno Meregalli, Silvia Mas Esteller, Raúl Porras, Montse Porto Turiel, Ma Angels Beneitez, Lázaro, Mónica de Luna Navarro, Ma Asunción Gotzens Busquet, Esther Moral Ramirez, Eulàlia Planas Sanz, Elisabeth Reverter Garcia, Verónica Villarejo Romero, M. Àngels Chicano Picornell, Elena Borlan Agüero, M. Luisa de Pablo Pons, Silvia López Merchena, Dolors Canadell Villaret, Núria Vilardebò Lucas, Sílvia Fuster Alay, Sandra Silva Ortega, Montserrat Pasarisas Sala, Aurora Lombó Vega, M. Lourdes Sans Estrada, Andrea Finestres Parra, Mireia Sierra Alegret, Rosa Maria Casademont Pou, Ma Esther Martínez García, Ivan Martí Garcia, Alícia Portella Serra, Rosa Minguell Cos, Carmen Serrano Barahona, Ma Isabel Jiménez García, Marta Franquesa Ibáñez, Montserrat Lloveras Viñals, Montserrat Sánchez Bonet, Lucila Caridad Davidovich, Maria Mercedes Roqueta del Riego, Araceli García García, Marta de Quixano Burgos, Ma Carmen Ruiz Salido, Sara Rosell Salas, Francisca Peidró Martín, Cristina Vivas Brau, M° Eugenia Sanchez López, Cristina Bonaventura Sans, Alicia Gámiz Gala, Ma del Pilar Cortés Viana, Consol Méndez Vallejos, Maria Castells Icart, Maria Pilar Olba Ros, Ma Teresa Garcia Fructuoso, Inmaculada Farré Ortega, Anna Guimet Villalba, Núria Baraza Ramos, Ana Ma Embid García, Meritxell Aivar Blanch, Rosa Maria Garcia Andrade, José Enrique Andrés Roldán, Milsa Josefa Cobas Selva, Blanca Inmaculada Macías Cajal, Marta Vicente Rodríguez, Sílvia Díaz Arcos, Claudia Pérez Gotarda, Josep Antonio Serrano Marchuet Zeki, Babà Moadem Montserrat, Alsina Freixa Rosa, Maria Pérez Polo, Elisabeth Celemin Garriga, Ma Gemma Baulies Romero, Maria Mercedes Gámez González, Mireia Gallardo Díaz, Marta Pujol Armengol, Núria Bartrés Canet, Verónica Ferrer Valls, Mercedes Pérez Vera, Ma Remedios Montes Velayos, Lucia Mónica Cano, López Ma del Carmen Muñoz Duque, Eva Mon López, Maria Amparo Fernández Feijoo, Antonio Gomez Navarro, Eva María Pacheco Navas, Aurora López Galán, Anna Rosa Casado Sivera, Josefina Castillo Hidalgo, Rosa Maria Martinez Rubió, Marta Chuecos Molina, Estíbaliz Molina Gallego, Raquel Garreta Martín, Esther Caraballo Prieto, Ma Concepció Cortés Rivera, Francisco Javier Farré López, Inmaculada Moreno Royo, Aurora Mola Sanna, Ma de las Mercedes Blanco Cardona, Ma Angels Viader Olivilla, Cecília Crusats Jiménez, Ana Ma Hostalot Abás Concepcion Muñoz Racero Ma Dolores Bielsa Murillo Àngela Martínez Picó Laia Parron Lagunas, Maria Mercedes Garcia Drago, Angelina Garcia Moreno, Ma Cristina López Roca, Olga Fernández Fernández, Maria Irene Rodrigo Bravo, Ma Dolors Panadés Mas, Mireia Diaz Docon, Montserrat Márquez Ruiz, Ana Villanueva Puerto, Ma Jesús Avila Villalón, Ma Pilar Sola Sola, M. VictoriaValls Ibáñez, Maria Pilar Gonzalvo Pueyo, Anna Sánchez García, Encarnación Fernández Férez, Mercedes Ramia Estaún, Maria Teresa Gutierrez García, Luisa Ma Angeles López Hernández, Ma José Torregrosa Bertet, Ramona Ortiz López, Anna Vilaro Carulla, Itziar Martín Ibáñez, Luisa Pretel Ordoñez, Rosa Maria Garrido Herrador, Maria Angeles Crespo Garcia, Africa Raventós Canet, Rebeca Sarrat Torres, Estebana Mendoza Egea, Montserrat Lozano Saló, Josep Maria Roquer Gonzalez, Mercedes Gómez Fernández, Rosa Ma Beringues Sorbías, M. Mercè Grau Fernàndez, Laura Enguix Martínez, Mercedes García Ortiz, Anna Vilalta Freixa, Gemma Martinez Galvez, María Ester de la Fuente Requena, Ana Pereira Leiva, Montserrat Antúnez Xaus, Anna Ma Serra Palá, Francisco José Molina Jiménez, Ma Mercè Aubanell Serra, Ana Maria Pol Pons, Ma Esmeralda Marrodan Herrero, Gemma Puig Lara, Ma Julia Rodríguez Martínez, Ma Jesús Llobera Bauzá, M Trinidad Hidalgo Benavides, Concepción García Pelaez, Irene Rovira Avellaneda, Montserrat Piñol Marce, Amadora Moral Martos, Yolanda Font Casas, Ma Teresa Joval Cepriá, Montserrat Martínez Marzal, Juana Maria Pérez Llamas, Nydia Fernanda Cabrera Alonso, Ma Nieves Sales Jiménez, Jesus Bernad Suarez, Marian Llussà Arboix, Carla Benedicto Pañell, Melcior Marti, i Fàbregas, Mireia Boquet Martínez.

References

- U.S.Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Respiratory Health Effects of Passive Smoking. EPA, Office of Research and Development, Office of Health and Environmental Assessment Washington DC EPA/600/6-90/006F. 1992. http://www.epa.gov/smokefree/healtheffects.html

- Watson RR. Environmental tobacco smoke. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Doll R, HILL AB. Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report. Br Med J. 1950;2:739–748. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4682.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Surgeon General. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General.U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta, Georgia; 2006. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/secondhandsmoke/report/executivesummary.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Boldo E, Medina S, Oberg M, Puklova V, Mekel O, Patja K. et al. Health impact assessment of environmental tobacco smoke in European children: sudden infant death syndrome and asthma episodes. Public Health Rep. 2010;125:478–487. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshammer H, Hoek G, Luttmann-Gibson H, Neuberger MA, Antova T, Gehring U. et al. Parental smoking and lung function in children: an international study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1255–1263. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200510-1552OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DG, Strachan DP. Health effects of passive smoking-10: Summary of effects of parental smoking on the respiratory health of children and implications for research. Thorax. 1999;54:357–366. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.4.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking. Lyon. IARC Monographs 83. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2002. http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol83/mono83.pdf [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008:The MPOWER package Geneva. World Health Organization; 2008. http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/en/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Villalbi JR. Assesment of the Spanish law 28/2005 for smoking prevention. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2009;83:805–820. doi: 10.1590/S1135-57272009000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebot M, Lopez MJ, Tomas Z, Ariza C, Borrell C, Villalbi JR. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke at work and at home: a population based survey. Tob Control. 2004;13:95. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez E. Spain: going smoke free. Tob Control. 2006;15:79–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salleras L, Taberner JL, Salto E, Altet N, Fernandez R, Jane M, Guia per a la prevenció i el control del tabaquisme des de l'àmbit pediàtric. Departament de Sanitat i seguretat social Generalitat de Catalunya; 2003. http://www.gencat.cat/salut/depsalut/pdf/gtabacp.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jane M, Martinez C, Altet N, Castellanos E, Fernandez R, Garcia O. Guia clínica per promoure l'abandonament del consum de tabac durant l'embarás. Departament de Salut; 2006. http://www.gencat.cat/salut/depsalut/pdf/catalegcatdefset06.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mannino DM, Siegel M, Husten C, Rose D, Etzel R. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and health effects in children: results from the 1991 National Health Interview Survey. Tob Control. 1996;5:13–18. doi: 10.1136/tc.5.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strachan DP, Cook DG. Health effects of passive smoking. 6. Parental smoking and childhood asthma: longitudinal and case-control studies. Thorax. 1998;53:204–212. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.3.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannino DM, Moorman JE, Kingsley B, Rose D, Repace J. Health effects related to environmental tobacco smoke exposure in children in the United States: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:36–41. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson A, Hermansson G, Ludvigsson J. How should parents protect their children from environmental tobacco-smoke exposure in the home? Pediatrics. 2004;113:e291–e295. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.e291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly JB, Wiggers JH, Considine RJ. Infant exposure to environmental tobacco smoke: a prevalence study in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25:132–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2001.tb01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordoba-Garcia R, Garcia-Sanchez N, Suarez Lopez de Vergara RG, Galvan FC. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in childhood. An Pediatr (Barc) 2007;67:101–103. doi: 10.1016/s1695-4033(07)70568-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons KM, Hammond SK, Fava JL, Velicer WF, Evans JL, Monroe AD. A randomized trial to reduce passive smoke exposure in low-income households with young children. Pediatrics. 2001;108:18–24. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossum B, Arborelius E, Bremberg S. Evaluation of a counseling method for the prevention of child exposure to tobacco smoke: an example of client-centered communication. Prev Med. 2004;38:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway TL, Woodruff SI, Edwards CC, Hovell MF, Klein J. Intervention to reduce environmental tobacco smoke exposure in Latino children: null effects on hair biomarkers and parent reports. Tob Control. 2004;13:90–92. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.004440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groner JA, Hoshaw-Woodard S, Koren G, Klein J, Castile R. Screening for children's exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in a pediatric primary care setting. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:450–455. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SS, Lam TH, Salili F, Leung GM, Wong DC, Botelho RJ. et al. A randomized controlled trial of an individualized motivational intervention on smoking cessation for parents of sick children: a pilot study. Appl Nurs Res. 2005;18:178–181. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah AS, Mak YW, Loke AY, Lam TH. Smoking cessation intervention in parents of young children: a randomised controlled trial. Addiction. 2005;100:1731–1740. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priest N, Roseby R, Waters E, Polnay A, Campbell R, Spencer N, Family and carer smoking control programmes for reducing children's exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008. http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/SpringboardWebApp/userfiles/ccoch/file/World%20No%20Tobacco%20Day/CD001746.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nafstad P, Botten G, Hagen JA, Zahlsen K, Nilsen OG, Silsand T. et al. Comparison of three methods for estimating environmental tobacco smoke exposure among children aged between 12 and 36 months. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:88–94. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichini S, Altieri I, Pellegrini M, Pacifici R, Zuccaro P. The analysis of nicotine in infants' hair for measuring exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Forensic Sci Int. 1997;84:253–258. doi: 10.1016/S0379-0738(96)02069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Delaimy WK. Hair as a biomarker for exposure to tobacco smoke. Tob Control. 2002;11:176–182. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.3.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakarian JM, Hovell MF, Sandweiss RD, Hofstetter CR, Matt GE, Bernert JT. et al. Behavioral counseling for reducing children's ETS exposure: implementation in community clinics. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:1061–1074. doi: 10.1080/1462220412331324820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen M, Bisgaard H, Stage M, Loft S. Biomarkers of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in infants. Biomarkers. 2007;12:38–46. doi: 10.1080/13547500600943148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrman CA, Hovell MF. Protecting children from environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure: a critical review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5:289–301. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000094231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M, Grimshaw J, Steen N. Sample size calculations for cluster randomised trials. Changing Professional Practice in Europe Group (EU BIOMED II Concerted Action) J Health Serv Res Policy. 2000;5:12–16. doi: 10.1177/135581960000500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mataix-Sancho J, Cabezas C, Lozano-Fernandez J, Camarelles F, Ortega G, Grups d'Abordatge del Tabaquisme de semFYC i d'Educació per a la Salut del PAPPS-semFYC. Guía para el tratamiento del tabaquismo activo y pasivo. Sociedad Española (SEMFyC) y Sociedad Catalana (CAMFiC) de Medicina de Familia y Comunitaria. 2008. http://www.camfic.cat/CAMFiC/Projectes/Sense_Fum/X_SenseFum/Docs/GuiaSSH09catweb.pdf

- Institut Municipal d'Assistència Sanitària (IMAS) Guia per a pares fumadors de nens asmàtics. IMAS-Hospital del Mar Informació d'educació sanitària. 2005. http://www.parcdesalutmar.cat/mar/guiafumadorsCATok.pdf

- Pascual JA, Diaz D, Segura J, Garcia-Algar O, Vall O, Zuccaro P. et al. A simple and reliable method for the determination of nicotine and cotinine in teeth by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:2853–2855. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uematsu T, Mizuno A, Nagashima S, Oshima A, Nakamura M. The axial distribution of nicotine content along hair shaft as an indicator of changes in smoking behaviour: evaluation in a smoking-cessation programme with or without the aid of nicotine chewing gum. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;39:665–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb05726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kintz P, Tracqui A, Mangin P. Detection of drugs in human hair for clinical and forensic applications. Int J Legal Med. 1992;105:1–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01371228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Image 1. Cut a lock of the hair. Images showing how to cut a lock of baby's hair.

Image 2. Sample of the baby's hair to label and send. Image of a sample of baby's hair that was used to analyze nicotine concentration.

Image 3. Leaflet: Passive smoking: advice to decrease exposure in babies. Image showing a leaflet in Catalan which contains correct and incorrect advices for parents to reduce baby's exposure to environmental tobacco smoke.