Abstract

There has long been an interest in examining the involvement of opioid neurotransmission in nicotine rewarding process and addiction to nicotine. Over the past 3 decades, however, clinical effort to test the effectiveness of nonselective opioid antagonists (mainly naloxone and naltrexone) for smoking cessation has yielded equivocal results. In light of the fact that there are three distinctive types of receptors mediating actions of the endogenous opioid peptides, this study, using a rat model of nicotine self-administration, examined involvement of different opioid receptors in the reinforcement of nicotine by selective blockade of the μ1, the δ, and the κ opioid receptors. Male Sprague-Dawley rats were trained in daily 1 h sessions to intravenously self-administer nicotine (0.03 mg/kg/infusion) on a fixed-ratio 5 schedule. After establishment of stable nicotine self-administration behavior, the effects of the opioid antagonists were tested. Separate groups of rats were used to test the effects of naloxanazine (selective for μ1 receptors, 0, 5, 15 mg/kg), naltrindole (selective for δ receptors, 0, 0.5, 5 mg/kg), and 5′-guanidinonaltrindole (GNTI, selective for κ receptors, 0, 0.25, 1 mg/kg). In each individual drug group, the 3 drug doses were tested by using a within-subject and Latin-Square design. The effects of these antagonists on food self-administering behavior were also examined in the same rats in each respective drug group after retrained for food self-administration. Pretreatment with naloxonazine, but not naltrindole or GNTI, significantly reduced responses on the active lever and correspondingly the number of nicotine infusions. None of these antagonists changed lever-pressing behavior for food reinforcement. These results indicate that activation of the opioid μ1, but not the δ or the κ, receptors is required for the reinforcement of nicotine and suggest that opioid neurotransmission via the μ1 receptors would be a promising target for the development of opioid ligands for smoking cessation.

Keywords: Antagonist, nicotine, opioid receptors, reinforcement, self-administration

1. Introduction

Tobacco smoking is one of the leading preventable causes of death in the United States (USDHHS, 2004). The adverse health effects from smoking account for an estimated 438,000 deaths, or nearly 1 of every 5 deaths, each year (CDC, 2005,CDC, 2004). Moreover, the prevalence of smoking still remains high with an approximate 22% of adults and 24% of youth being currently smokers (CDC, 2004). Although there have been several pharmacological treatments available, i.e. nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, and varenicline, long-term abstinence rates even on these drug treatment are unsatisfactorily low. The 1-year abstinence rates are ≤16.1% for bupropion, ≤20.3% for nicotine replacement and ≤26.1% for varenicline (Aubin et al., 2008; Gonzales et al., 2006; Jorenby et al., 2006). Therefore, there is an imperative need to develop more effective treatments for tobacco smoking.

Increasing evidence has shown that opioid neurotransmission is implicated in mediating rewarding actions and dependence of drugs of abuse including nicotine (Berrendero et al., 2010; Gianoulakis, 2004; Le Merrer et al., 2009; Pomerleau, 1998; Xue and Domino, 2008). For instance, nicotine administration has been found to increase expression and release of opioid peptides in mesolimbic regions (Boyadjieva and Sarkar, 1997; Davenport et al., 1990; Dhatt et al., 1995; Houdi et al., 1998; Houdi et al., 1991; Pierzchala et al., 1987). Opioid receptor antagonists have been reported to decrease nicotine-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens, an important terminal region of the mesolimbic dopamine circuitry (Tanda and Di Chiara, 1998), reduce nicotine reward (Walters et al., 2005; Zarrindast et al., 2003), and precipitate withdrawal symptoms in rats treated chronically with nicotine (Malin et al., 1993). Over the past 3 decades, however, clinical effort to test the effectiveness of opioid antagonists (mainly naloxone and naltrexone) for smoking cessation has yielded equivocal results: some trials reported that these antagonists reduced consumption of cigarettes while others failed to find any benefit (e.g., Gorelick et al., 1988; Karras and Kane, 1980; King et al., 2006; King and Meyer, 2000; Krishnan-Sarin et al., 1999; Nemeth-Coslett and Griffiths, 1986; Ray et al., 2006; Rukstalis et al., 2005; Sutherland et al., 1995; Wewers et al., 1998; Wong et al., 1999). Therefore, more clinical tests with larger sample sizes have been recommended in order to confirm or refute the usefulness of opioid antagonists for smoking cessation (David et al., 2006).

Similarly, laboratory animal research has also produced mixing findings. Earlier intracranial manipulation studies have found that a μ-opioid agonist, DAMGO, microinjected into the ventral tegmental area (Corrigall et al., 2000) or the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (Corrigall et al., 2002) effectively reduced nicotine self-administration in rats. However, systemic administration of the opioid antagonists naloxone and naltrexone did not produce an effect (Corrigall and Coen, 1991; DeNoble and Mele, 2006). In our work, neither acute nor chronic pretreatment with naltrexone across 7 daily nicotine self-administration sessions altered nicotine intake in the rats trained to steadily self-administer nicotine (Liu et al., 2009). In contrast, studies using knockout mice showed that deletion of the μ-opioid receptors or their endogenous ligand β-endorphin resulted in decreased rewarding properties of nicotine as measured by the conditioned place preference paradigm (Berrendero et al., 2002; Trigo et al., 2009). Moreover, a recent rat study reported that naloxone reduced nicotine self-administration (Ismayilova and Shoaib, 2010). Therefore, it remains to be elucidated what roles the opioid receptors play in mediating nicotine reward.

The aforementioned inconsistent results in clinical and animal research may be attributable to the existence of different types of the opioid receptors. There are 3 main types of the opioid receptors: μ (including μ1 and μ2), δ and κ (Dhawan et al., 1996; Mansour et al., 1995; Snyder and Pasternak, 2003). These receptors have quite divergent and in some cases even opposite actions. In the drug rewarding processes, for instance, activation of the μ and κ receptors may have opposite actions with the κ receptors opposing rewarding actions and/or enhancing aversive effects of drugs (Galeote et al., 2009; Hasebe et al., 2004; Matsuzawa et al., 1999; Shippenberg et al., 2007). The μ and δ receptors have an opposite role in regulating anxiety states in that knockout mice lacking μ receptors showed decreased level of anxiety whereas the δ receptor knockout mice had higher anxiety (Filliol et al., 2000). In the tests measuring the anxiety states induced by nicotine the μ and δ receptor antagonism produced opposite effects whereas the κ receptor antagonist showed no effect (Balerio et al., 2005). Therefore, due to their broad spectrum of actions the nonselective receptor antagonists such as naloxone and naltrexone can block different opioid receptors and unfortunately the effects of blocking individual types of receptors might have offset one another.

With the currently available antagonists that are highly selective for the different types of the opioid receptors, this study examined the effect of a pharmacological blockade of opioid neurotransmission via the μ1, δ, and κ receptors on nicotine reinforcement in a rat self-administration paradigm. Specifically, rats were operantly trained to intravenously self-administer nicotine. After establishment of stable nicotine self-administering behavior, effects of naloxanazine (selective for μ1 receptors), naltrindole (selective for δ receptors), and 5′-guanidinonaltrindole (GNTI, selective for κ receptors) were examined. To provide control for the specificity of these antagonists, their effects on food self-administration were also determined in the same set of rats.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Prattville, AL, USA) were used. The animals were approximate 2 months old (weighing 225–250 g) upon arrival and about 4.5 months old during the pharmacological tests (see below). Rats were individually housed in a humidity- and temperature-controlled (21–22 °C) colony room on a reversed light/dark cycle (lights on 20:00; off 8:00) with unlimited access to water. After one week of acclimation, rats were placed on a food-restriction regimen (20 g chow/day, about 85% of ad libitum calories) throughout the experiments. Training and experimental sessions were conducted during the dark phase at the same time each day (10:00–17:00). All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the University of Mississippi Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Drugs

(−)-Nicotine hydrogen tartrate, naloxonazine dihydrochloride hydrate, naltrindole hydrochloride, and 5′-guanidinonaltrindole di(trifluoroacetate) salt hydrate (GNTI) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). For self-administration, (−)-nicotine hydrogen tartrate was dissolved in physiological saline and concentration/dose was expressed as free base. The solution was adjusted to pH 7.0±0.4 with 1N sodium hydroxide solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and then sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 μm syringe filter (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). For pharmacological tests, naloxonazine, naltrindole, and GNTI were dissolved in physiological saline and administered intraperitoneally in a volume of 1 ml/kg. The doses of these antagonists and pretreatment timing (5 h before test for naloxonazine and 30 min before test for naltrindole and GNTI) were determined based on the pharmacokinetics of these agents and previous studies (e.g., Campbell et al., 2007; Ciccocioppo et al., 2002; Inan et al., 2009; Mhatre and Holloway, 2003; Negus et al., 2002).

2.3. Self-administration apparatus

Operant training and self-administration tests were conducted in sixteen operant conditioning chambers located inside sound-attenuating, ventilated cubicles (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT). The chambers were equipped with two retractable response levers on one side panel and with a 28-V (100 mA) white light above each lever as well as a red house light on the top of the chambers. Between the two levers was a food pellet trough. Intravenous nicotine injections were delivered by a drug delivery system with a syringe pump (Med Associates, model PHM100-10 rpm). Experimental events and data collection were automatically controlled by an interfaced computer and software (Med Associetes, Med-PC IV).

2.4. Food training

To facilitate learning of operant responding for nicotine self-administration (see below), animals were first trained in daily sessions to press a lever for food reinforcement. Introduction of the two levers and illumination of the red house light signaled the start of the session. Responses the right lever were rewarded with delivery of a food pellet (45 mg). Sessions lasted 1-h with a maximum of 45 food pellets available. Once rats earned all the 45 food pellets on a fixed-ratio (FR) 1 schedule in a single session, the reinforcement schedule was increased to FR5. Successful food training, defined as 45 pellets earned on the FR5 schedule in a single session, was achieved within 2–5 daily sessions.

2.5. Surgery

After food training, the rats were anesthetized with an isoflurane-oxygen mixture (1–3% isoflurane) and implanted with jugular catheters. Catheters were constructed using a 15 cm piece of Silastic tubing (0.31 mm ID and 0.63 mm OD, Dow Corning Corporation, Midland, Michigan, USA) attached to a 22-gauge stainless-steel guide cannula. The latter was bent and molded onto a durable polyester mesh (Plastics One Inc., Roanoke, Virginia, USA) with dental cement and became the catheter base. Through an incision on the rat back, the base was anchored underneath the skin at the level of scapulae and the catheter passed subcutaneously to the ventral lower neck region and inserted into the right jugular vein (3.5 cm). Animals were allowed at least 7 days to recover from surgery. During the recovery period, the catheters were flushed daily with 0.1 ml of sterile saline containing heparin (30 U/ml) and timentin (66.7 mg/ml) to maintain catheter patency and prevent infection. Thereafter, the catheters were flushed with the heparinized saline before and after the experimental sessions throughout the experiments.

2.6. Nicotine self-administration training

After recovery from surgery, rats were trained to intravenously self-administer nicotine (0.03 mg/kg/infusion, free base). In the training sessions, animals were placed in the operant conditioning chambers and connected to the drug delivery system. The daily 1-h sessions were initiated by introduction of the two levers and illumination of the red house light. Once the FR requirement on the active (right) lever was met, an infusion of nicotine was dispensed by the drug delivery system in a volume of 0.1 ml in approximately 1 s depending on the body weight of rats. Each nicotine infusion was signaled with a presentation of an auditory/visual stimulus consisting of a 5 s tone and 20 s turn-on of the lever light. The latter signaled a 20 s timeout period during which time responses were recorded but not reinforced. Responses on the inactive lever had no consequence. An FR1 schedule was used for the first 5 days, an FR2 for days 6–8 and an FR5 for remainder of the experiments. All rats received 25 daily self-administration training sessions before any pharmacological tests because our previous work showed that rats readily developed stable nicotine self-administration behavior within 25 sessions (Liu et al., 2006).

2.7. Pharmacological tests

After training, rats were divided into 3 drug groups in a pseudorandom order so that each drug group had similar profiles of lever responding and nicotine infusions.

2.7.1. Effect of naloxonazine on nicotine self-administration

Eight rats were used to test the effect of naloxonazine, a selective μ1 opioid receptor antagonist. Due to its long-lasting effect and possible initial interference with other opioid receptors (Johnson and Pasternak, 1984; Ling et al., 1986), naloxonazine pretreatment was given 5 hours before test. Rats were subjected to an intraperitoneal administration of naloxonazine (0, 5, 15 mg/kg) in a within-subject design. Every rat received each dose of naloxonazine once in a counterbalanced order. Test sessions were separated by 2 no-drug pretreatment sessions in order to eliminate possible carry-over effect of the drug. Therefore, after 25 daily training sessions the test sessions were performed on days 26, 29, and 32 with no-drug testing sessions in between.

2.7.2. Effect of naltrindole on nicotine self-administration

Ten rats were used to test the effect of naltrindole, a selective δ opioid receptor antagonist. Thirty min before the test, rats were subjected to an intraperitoneal administration of naltrindole (0, 0.5, 5 mg/kg) in a within-subject design. Every rat received each dose of naltrindole once in a counterbalanced order. To be comparable to the testing schedule for naloxonazine described above, the test sessions were also performed on days 26, 29, and 32 with no-drug testing sessions in between.

2.7.3. Effect of GNTI on nicotine self-administration

Eight rats were used to test the effect of GNTI, a selective κ opioid receptor antagonist. Thirty min before the test, rats received an intraperitoneal administration of GNTI (0, 0.25, 1 mg/kg) in a within-subject design. Every rat received each dose of GNTI once in a counterbalanced order. To be comparable to the testing schedule for naloxonazine described above, the test sessions were also performed on days 26, 29, and 32 with no-drug testing sessions in between.

2.7.4. Effect of naloxonazine, naltrindole, and GNTI on food self-administration

After the nicotine self-administration tests, effects of these antagonists on food self-administration were examined in respective drug groups. Specifically, rats were re-trained to press the lever for food reinforcement under conditions identical to that for nicotine self-administration, except that food pellets instead of nicotine infusions were delivered. That is, responses on the active lever resulted in delivery of food pellets and presentation of the auditory/visual stimulus on a FR5 schedule with a 20 min timeout period. Stable food self-administration behavior was achieved within 10 sessions. Then, the antagonist pretreatment tests were conducted in respective drug groups in a within-subject design and counterbalanced manner. The dosing and timing of administration of these antagonists was exactly the same as described above for the nicotine self-administration tests.

2.8. Statistical analyses

Data are presented as the mean±SEM number of lever responses and reinforcers (nicotine infusions and food pellets) earned. The data obtained from the nicotine and the food tests were analyzed separately. In both tests, the data collected from the 3 antagonist groups were separately analyzed. In each antagonist group, the number of lever responses was first analyzed using two-way ANOVA with drug dose and lever as factors. Then, the responses on the active and the inactive levers were further examined separately using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Newman-Keuls post hoc tests to verify differences among individual means. The number of reinforcers was analyzed using one-way ANOVA and subsequent Newman-Keuls post hoc tests.

3. Results

3.1. Nicotine self-administration

In 25 daily 1-h self-administration training sessions, rats developed stable levels of operant responding for nicotine infusions. Averaged across the final three sessions (sessions 23, 24, 25), rats made a mean±SEM number of responses of 78.7±8.9 on the active lever and 11.4±3.5 on the inactive lever. Correspondingly, rats earned 13.4±1.2 infusions of nicotine. Since rats were divided into three groups for subsequent opioid antagonist tests in a pseudorandom manner, there was no difference among groups in responses on the active lever [F(2,23)=0.14, p>0.05] and the inactive lever [F(2,23)=0.91, p>0.05], nicotine infusion [F(2,23)=0.12, p>0.05], and body weights[F(2,23)=0.33, p>0.05]. Detailed information is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Behavioral and body weight profiles of the three drug groups of rats at the end of nicotine self-administration training phase (before the pharmacological tests). The lever responses and nicotine infusions earned were averaged across the final 3 training sessions (days 23, 24, 25). Body weights were measured immediately before the first drug test session.

| Naloxonazine group (n=8) | Naltrindole group (n=10) | GNTI group (n=8) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Responses | |||

| Active Lever | 76±10 | 82±14 | 78±6 |

| Inactive Lever | 12±3 | 11±7 | 11±6 |

| Nicotine Infusions | 12.9±3.8 | 14.1±4.2 | 13.2±2.7 |

| Body Weights | 298±19 | 305±26 | 289±23 |

3.2. Effect of naloxonazine on nicotine self-administration

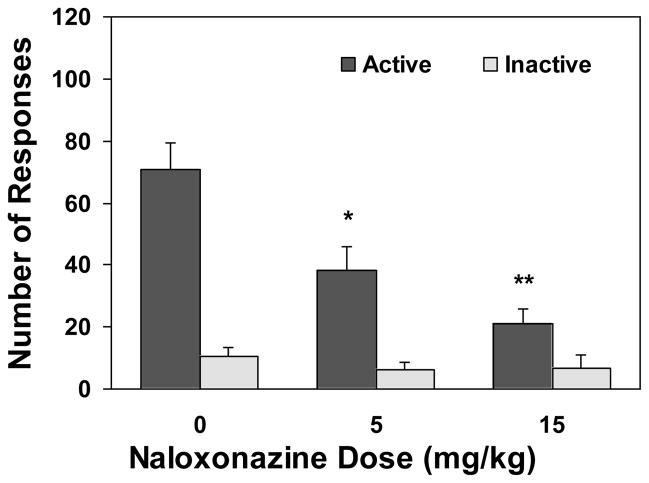

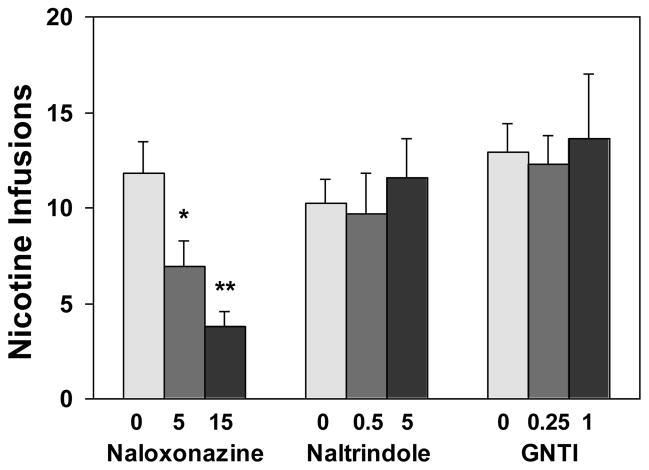

As show in Figures 1 and 4, pretreatment with the μ1-selective antagonist naloxonazine significantly reduced nicotine self-administration. An overall two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of drug dose [F(2,42)=7.32, p<0.01] and lever [F(1,42)=41.55, p<0.0001] and a significant dose X lever interaction [F(2,42)=7.19, p<0.01]. Further one-way ANOVA on the number of active lever responses yielded a significant effect of drug dose [F(2,21)=8.00, p<0.01]. Subsequent Newman-Keuls post hoc analyses showed a significant decrease of responses under the 15 (p<0.01) and the 5 mg/kg (p<0.05) conditions as compared to the vehicle-treated condition. However, one-way ANOVA on the inactive lever responses yielded no significant effect of the drug [F(2,21)=0.01, p>0.05]. That is, responses on the inactive lever remained at low levels indistinguishable among the different dose conditions. A one-way ANOVA on the nicotine infusions earned yielded a significant effect of drug dose [F(2,21)=7.17, p<0.01] and subsequent Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis showed significant decrease in the number of nicotine infusions under the 15 (p<0.01) and the 5 mg/kg (p<0.05) conditions as compared to vehicle condition.

Figure 1.

Effect of naloxonazine, an antagonist selective for the μ1 opioid receptors, on nicotine self-administration behavior. After establishment of stable nicotine self-administration in 25 daily sessions, rats (n=8) were pretreated with naloxonazine 5 hours before the test sessions in a within subject design and counterbalanced manner. The tests were separated by two no-drug pretreatment sessions. The number of lever responses is expressed as mean (±SEM). * p < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 significant difference from vehicle (0) condition.

Figure 4.

Effect of naloxonazine, naltrindole, and GNTI on the number of nicotine infusions. After stable nicotine self-administration was achieved in 25 daily sessions, the tests began. In each respective drug group, rats were subjected to pretreatment with naloxonazine (5 h before the tests), naltrindole or GNTI (30 min before the tests) in a within subject design and counterbalanced manner. There were two no-drug pretreatment sessions inserted between the tests. The doses of these antagonists are in mg/kg. The number of nicotine infusions is expressed as mean (±SEM). * p < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 significant difference from respective 0 (vehicle) condition.

3.3. Effect of naltrindole on nicotine self-administration

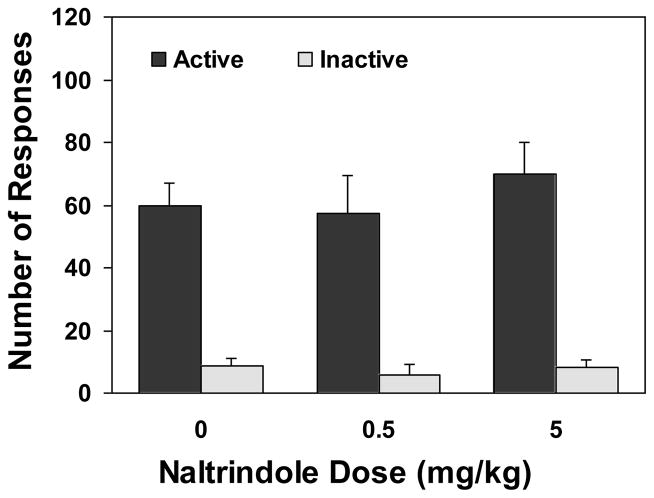

Pretreatment with the δ-selective antagonist naltrindole did not change nicotine self-administration (Figures 2 and 4). An overall two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of lever [F(1,54)=129.79, p<0.0001] but not of drug dose [F(2,54)=1.57, p>0.05]. There was no significant interaction between drug dose and lever [F(2,54)=1.30, p>0.05]. Consequently, one-way ANOVA failed to produce a significant effect of the drug dose on the number of active [F(2,27)=1.51, p>0.05] and inactive lever responses [F(2,27)=0.12, p>0.05]. There was no change after drug pretreatment in the number of nicotine infusions [F(2,27)=0.94, p>0.05].

Figure 2.

Nicotine self-administration behavior after pretreatment with naltrindole, an antagonist selective for the δ opioid receptors. Rats (n=10) were trained in 25 daily sessions to acquire stable nicotine self-administration. Then, they received an administration of naltrindole 30 min before the test sessions in a within subject design and counterbalanced manner. The tests were separated by two no-drug pretreatment sessions. The number of lever responses is expressed as mean (±SEM).

3.4. Effect of GNTI on nicotine self-administration

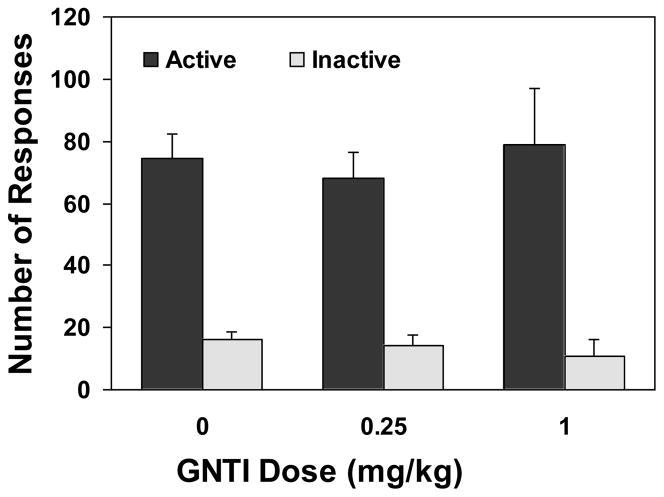

There was no significant change in nicotine self-administration after treatment with the κ-selective antagonist GNTI (Figures 3 and 4).). An overall two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of lever [F(1,42)=53.20, p<0.0001] but not of drug dose [F(2,42)=0.74, p>0.05]. There was no significant dose X lever interaction F(2,42)=0.25, p>0.05]. Consequently, one-way ANOVA did not find a significant effect of drug dose on the number of active [F(2,21)=0.16, p>0.05] and inactive lever responses [F(2,21)=0.21, p>0.05]. The number of nicotine infusions earned after drug pretreatment remained unchanged [F(2,27)=0.07, p>0.05].

Figure 3.

Nicotine self-administration behavior after pretreatment with GNTI, an antagonist selective for the κ opioid receptors. The tests were conducted after completion of 25 daily nicotine self-administration training sessions and scheduled with two no-drug pretreatment sessions in between. Rats (n=8) were subjected to an administration of GNTI 30 min before the test sessions in a within subject design and counterbalanced manner. The number of lever responses is expressed as mean (±SEM).

3.5. Effect of opioid antagonists on food self-administration

Pretreatment with naloxonazine, naltrindole, and GNTI in each respective group of rats did not alter food self-administering behavior. In each individual antagonist group, neither an overall two-way ANOVA (drug dose and lever as factors) nor a subsequent one-way ANOVA (drug dose as factor) yielded significant effect of the drug treatment (data not shown). Detailed information on the number of lever responses is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Lever responses for food reinforcement after pretreatment with the opioid antagonists selective for the μ1, δ, and κ opioid receptors.

| Active Lever Responses | Inactive lever responses | |

|---|---|---|

| Naloxonazine (n=8) | ||

| vehicle | 349±56 | 23±12 |

| 5 mg/kg | 319±30 | 15±5 |

| 15 mg/kg | 330±47 | 21±7 |

| Naltrindole (n=10) | ||

| vehicle | 363±80 | 14±4 |

| 0.5 mg/kg | 379±92 | 17±9 |

| 5 mg/kg | 339±61 | 17±5 |

| GNTI (n=8) | ||

| vehicle | 323±39 | 20±9 |

| 0.25 mg/kg | 349±60 | 12±5 |

| 1 mg/kg | 324±34 | 18±10 |

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated in a rat model of nicotine self-administration that blockade of the μ1 opioid receptors by a selective antagonist naloxonazine significantly reduced responses on the active lever and correspondingly the number of nicotine infusions, whereas pretreatment with the δ- or κ-selective antagonists (naltrindole or GNTI) did not change nicotine intake. These data indicate the involvement of opioid neurotransmission in nicotine reinforcement and further suggest that activation of the μ1, but not δ or κ, opioid receptors is required for the maintenance of well-established nicotine self-administering behavior.

There has been over the past 3 decades a long-standing interest of testing opioid antagonists for smoking cessation. However, both clinical and preclinical studies have produced equivocal results (Corrigall and Coen, 1991; DeNoble and Mele, 2006; Gorelick et al., 1988; Ismayilova and Shoaib, 2010; Karras and Kane, 1980; King et al., 2006; King and Meyer, 2000; Krishnan-Sarin et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2009; Nemeth-Coslett and Griffiths, 1986; Ray et al., 2006; Rukstalis et al., 2005; Sutherland et al., 1995; Wewers et al., 1998; Wong et al., 1999). It is worthy to note that opioid neurotransmission in the brain functions via activation of at least three major types of receptors: the μ1, δ, and κ opioid receptors. These receptors have distinctive, and in some cases opposite, actions. For instance, antagonism of the μ and δ receptors produced opposite effects on nicotine-induced anxiety whereas the κ receptor antagonist showed no effect (Balerio et al., 2005). In the drug rewarding processes, activation of the μ and κ receptors may have opposite actions with the κ receptors opposing rewarding actions and/or enhancing aversive effects of drugs (Galeote et al., 2009; Hasebe et al., 2004; Shippenberg et al., 2007). Due to the fact that previous studies typically used the nonselective opioid antagonists naloxone and naltrexone, the ambiguous data obtained from these studies might be attributable to the cross-reactivities among these receptors, which offsets the actions of the individual receptor types. This study addressed this issue by testing the effects of selective blockade of different types of the opioid receptors on nicotine reinforcement.

Naloxonazine irreversibly blocked the μ1-receptors with a very high potency and long duration of action (Hahn et al., 1982; Ling et al., 1986). To eliminate possibly initial effects of this agent on other (such as the μ2 subtype) opioid receptors (Johnson and Pasternak, 1984; Ling et al., 1986), the effect of naloxonazine on nicotine intake was examined five hours after its administration. The lack of effect of naloxonazine on the food self-administering responses and the inactive lever responses during the nicotine self-administration test ruled out nonspecific interference with operant behavior. Therefore, naloxonazine produced a specific suppressant effect on the lever-pressing responses maintained by nicotine self-administration, i.e., the primary reinforcement of nicotine. This finding indicates the critical involvement of opioid neurotransmission via the μ1-receptors in the nicotine rewarding process. The underlying mechanism may involve the μ1 modulation of dopamine neurons in the mesolimbic circuitry, which mediates the rewarding properties of drug of abuse including nicotine. For example, in the ventral tegmental area opioid peptides modulate dopamine neurotransmission predominantly via activation of the μ1 receptors (Tanda and Di Chiara, 1998) and in the nucleus accumbens μ agonist inhibited dopamine overflow and this effect was reversed by naloxonazine (Britt and McGehee, 2008). The suppressant effect of naloxonazine on nicotine intake is in line with previous research suggesting a role of the μ receptors in mediating the reinforcement of nicotine and tobacco smoking (Berrendero et al., 2002; Ismayilova and Shoaib, 2010; Karras and Kane, 1980; King and Meyer, 2000; Rukstalis et al., 2005; Trigo et al., 2009). Of significance is that the present data further pinpoint the μ1 type of the opioid receptors in mediating reinforcement of nicotine. It encourages the continued clinical effort to test the effectiveness of opioid antagonists for smoking cessation and further suggests that focusing medication development within the opioid system to the μ1 receptors might prove to be a fruitful strategy.

There are possible confounding factors embedded in nicotine self-administration procedures that need to be discussed. Noticeably, these concerns may also apply to the paradigms of self-administering any other psychostimulants. First, in animal drug self-administration designs a visual and/or auditory stimulus has been typically used to signal the delivery of the drug. In this study, a 5 s tone/20 s lever light on was used to mark nicotine infusions. The ability of nicotine to enhance operant behavior maintained by other reinforcers has been revisited in recent years. For instance, nicotine can enhance rat lever-pressing responses maintained by certain particular sensory stimuli (Chaudhri et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2007; Palmatier et al., 2006) that bear intrinsic reinforcing properties. Accordingly, a speculation is raised that naloxonazine might have interfered with the possible reinforcement-enhancing effect of nicotine rather than the nicotine’s primary reinforcement. However, this argument can be ruled out because of the fact that the stimulus used in the present study has little intrinsic reinforcing value (Liu et al., 2008). Second, in the present self-administration procedure, the active lever may have acquired conditioned reinforcing value in the food training phase. Since nicotine can also enhance lever-pressing responses maintained by conditioned reinforcers (Olausson et al., 2004; Raiff and Dallery, 2008; Uslaner et al., 2010), it is reasonable to speculate that rats might have lever-pressed for the conditioned reinforcer (established during food training) and nicotine, in addition to its primary reinforcement, enhanced that conditioned reinforcer-maintained responding. Accordingly, it is argued that naloxonazine might have suppressed the nicotine-enhanced active lever responses rather than the primary reinforcement of nicotine. However, our previous study, by switching the active and the inactive levers across the food training and nicotine self-administration phases, has demonstrated that rats can develop stable and similar levels of nicotine self-administration regardless of prior lever-pressing experience for food reinforcement (Liu et al., 2006), indicating that rat lever-pressing behavior was maintained by the primary reinforcement of nicotine rather than the conditioned reinforcer or the reinforcement-enhancement by nicotine. That data may provide a clue to rule out the concern that naloxonazine might have interfered with the reinforcement-enhancing effect of nicotine. Third, as a matter of fact, the similar speculation may extend to all the drug self-administration paradigms, even the ones without prior food training: the active lever can acquire conditioned reinforcing value by delivering the drug and in turn the drug (e.g., nicotine or any other psychostimultant) may further enhance responses maintained by the conditioned reincorcer. Besides, another argument may exist that after the first administration the drug is on board and can serve as a discriminative stimulus that encourages further lever pressing behavior. However, it should be acknowledged that using the conventional drug self-administration procedures, like the one used in this study, is difficult, if not possible at all, to fully settle these arguments.

The δ-selective antagonist naltrindole did not change nicotine self-administration behavior. The doses (up to 5 mg/kg) of naltrindole used in this study were high enough to effectively block activation of the δ receptors and selective enough to rule out any possible cross-reactivity with other opioid receptors. In literature, naltrindole in this dose range has been showed to reliably change a variety of behavior including operant ethanol-seeking responding (Ciccocioppo et al., 2002; Kitchen and Pinker, 1990) and have a good specificity for the δ receptors since it antagonized the antinociception by a δ agonist but not the μ or κ agonists (Portoghese et al., 1988). Thus, the lack of effect of naltrindole in the present study indicates that opioid neurotransmission via the δ receptors may not mediate the reinforcing properties of nicotine as measured by the operant nicotine self-administration paradigm. It is in line with evidence showing that this agent produced no change in nicotine-induced sensitization (Heidbreder et al., 1996) and consistent with a recent report showing unaltered nicotine intake after naltrindole pretreatment (0.3–3.0 mg/kg) using similar nicotine self-administration procedures (Ismayilova and Shoaib, 2010). However, these negative results seem to be at odds with a previous study using knockout mice that were deficient of preproenkephalin gene (producing enkephalin, the endogenous ligand for the δ receptors). These knockout mice showed a significant decrease in nicotine-induced conditioned place preference, indicating a reduction of the rewarding effects of nicotine (Berrendero et al., 2005). This discrepancy regarding involvement of the δ receptors in nicotine reward may be attributable to the significant differences in subjects (rats versus gene knockout mice) and the methods of measuring nicotine reward (self-administration versus conditioned place preference). Besides, it is interesting to note the evidence showing that the δ receptors have been implicated in other actions of nicotine. For instance, pharmacological antagonism of the δ receptors has been reported to change nicotine-induced antinociception (Campbell et al., 2007) and anxiogenic response (Balerio et al., 2005). Nevertheless, an alternative explanation of the knockout mouse data exists. Due to the fact that in addition to preferentially activating the δ receptors enkephalin also acts at the μ receptors (Drake et al., 2007), it is argued that the reduced rewarding properties of nicotine in these knockout mice may result be at least to some extent from the diminished μ receptor activities. Thus, the results obtained from these knockout mice in fact reconcile with the aforementioned suppression of nicotine self-administration by naloxonazine in the present study.

The present results showed no effect of GNTI on nicotine self-administration, indicating lack of involvement of κ receptor activation by the endogenous opioid peptides (mainly dynorphin). Since GNTI has high affinity for the κ receptors with more then 200-fold selectivity over the μ and δ receptors (Jones and Portoghese, 2000; Stevens et al., 2000), it could be argued that activation of the κ receptors by endogenously released dynorphin is not required for the reinforcing properties of nicotine. This conclusion is substantiated by the studies showing that the mice deficient of prodynorphin genes (which produces dynorphin) had a similar behavioral profiles in the conditioned place preference induced by nicotine, ethanol, and cocaine as compared to their wild type counterparts (Blednov et al., 2006; Galeote et al., 2009; McLaughlin et al., 2003). In a recent report (Ismayilova and Shoaib, 2010), however, the elevated activation of the κ receptors by experimenter administered agonist seemed to interfere with operant behavior for nicotine intake. In that study (Ismayilova and Shoaib, 2010), the selective κ receptor agonist U50,488 changed nicotine self-administering behavior in opposing directions depending on the doses administered. An increase of nicotine self-administration was observed after pretreatment with a low dose of 0.3 mg/kg, whereas rats decreased their nicotine self-administration after administration of higher doses (1 and 3 mg/kg). In light of the fact that U50,488 was found to produce “abnormal” behaviors (such as biting the edge of behavioral testing arena) at doses above 0.9 mg/kg (Kitamura et al., 2009) and that the κ agonists may bind to other opioid receptors and thereby to produce opposing actions (Heidbreder et al., 1995), the issue of whether and how increased activity of the κ receptors influences nicotine reinforcement needs further investigation. It is interesting to note that recent studies have suggested that activation of the κ receptors may play a role in the increased drug self-administration in drug dependent but not non-dependent subjects (Glick et al., 1995; Wee et al., 2009). For instance, Nor-BNI (a κ receptor antagonist) has been found to effectively reduce the escalated cocaine self-administration in the rats with a prolonged access to cocaine and the increased ethanol intake in the rats that became ethanol dependent by an ethanol vapor inhalation procedure (Walker et al., 2010; Wee et al., 2009).

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that maintenance of the well established nicotine self-administration in rats is sensitive to pharmacological antagonism of the μ1, but not the δ or the κ, opioid receptors. Together with the evidence showing that nicotine administration enhances release of the endogenous μ receptor ligand endorphin (Boyadjieva and Sarkar, 1997; Conte-Devolx et al., 1981; Marty et al., 1985; Rosecrans et al., 1985), these data indicate a critical role of opioid neurotransmission via the μ1 receptors in the rewarding properties of nicotine. The present results suggest that focusing on manipulation of the μ1 receptor-mediated pathways within the opioid system might prove to be a fruitful strategy for the development of medication for nicotine addiction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant DA017288 (X. Liu) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- FR

fixed-ratio

- GNTI

5′-guanidinonaltrindole

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aubin HJ, Bobak A, Britton JR, Oncken C, Billing CB, Jr, Gong J, Williams KE, Reeves KR. Varenicline versus transdermal nicotine patch for smoking cessation: results from a randomised open-label trial. Thorax. 2008;63:717–724. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.090647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balerio GN, Aso E, Maldonado R. Involvement of the opioid system in the effects induced by nicotine on anxiety-like behaviour in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181:260–269. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2238-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrendero F, Kieffer BL, Maldonado R. Attenuation of nicotine-induced antinociception, rewarding effects, and dependence in mu-opioid receptor knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10935–10940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10935.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrendero F, Mendizabal V, Robledo P, Galeote L, Bilkei-Gorzo A, Zimmer A, Maldonado R. Nicotine-induced antinociception, rewarding effects, and physical dependence are decreased in mice lacking the preproenkephalin gene. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1103–1112. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3008-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrendero F, Robledo P, Trigo JM, Martin-Garcia E, Maldonado R. Neurobiological mechanisms involved in nicotine dependence and reward: Participation of the endogenous opioid system. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blednov YA, Walker D, Martinez M, Harris RA. Reduced alcohol consumption in mice lacking preprodynorphin. Alcohol. 2006;40:73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyadjieva NI, Sarkar DK. The secretory response of hypothalamic beta-endorphin neurons to acute and chronic nicotine treatments and following nicotine withdrawal. Life Sci. 1997;61:PL59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt JP, McGehee DS. Presynaptic opioid and nicotinic receptor modulation of dopamine overflow in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1672–1681. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4275-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell VC, Taylor RE, Tizabi Y. Effects of selective opioid receptor antagonists on alcohol-induced and nicotine-induced antinociception. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1435–1440. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Annual smoking-attributable mortality, yeas of potentail life lost, and productivity losses-United States, 1997–2001. 2005;54:625–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2004. Vol. 52. State-specific prevalence of current cigarette smoking among adults - United State 2002; pp. 1277–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Booth S, Gharib M, Craven L, Palmatier MI, Liu X, Sved AF. Operant responding for conditioned and unconditioned reinforcers in rats is differentially enhanced by the primary reinforcing and reinforcement-enhancing effects of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;189:27–36. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0522-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Effect of selective blockade of mu(1) or delta opioid receptors on reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behavior by drug-associated stimuli in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:391–399. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00302-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte-Devolx B, Oliver C, Giraud P, Gillioz P, Castanas E, Lissitzky JC, Boudouresque F, Millet Y. Effect of nicotine on in vivo secretion of melanocorticotropic hormones in the rat. Life Sci. 1981;28:1067–1073. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90755-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigall WA, Coen KM. Opiate antagonists reduce cocaine but not nicotine self-administration. Psychopharmacology. 1991;104:167–170. doi: 10.1007/BF02244173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigall WA, Coen KM, Adamson KL, Chow BL, Zhang J. Response of nicotine self-administration in the rat to manipulations of mu-opioid and gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors in the ventral tegmental area. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;149:107–114. doi: 10.1007/s002139900355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigall WA, Coen KM, Zhang J, Adamson L. Pharmacological manipulations of the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus in the rat reduce self-administration of both nicotine and cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;160:198–205. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0965-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport KE, Houdi AA, Van Loon GR. Nicotine protects against mu-opioid receptor antagonism by beta-funaltrexamine: evidence for nicotine-induced release of endogenous opioids in brain. Neurosci Lett. 1990;113:40–46. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90491-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David S, Lancaster T, Stead LF, Evins AE. Opioid antagonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003086. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003086.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNoble VJ, Mele PC. Intravenous nicotine self-administration in rats: effects of mecamylamine, hexamethonium and naloxone. Psychopharmacology. 2006;184:266–272. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0054-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhatt RK, Gudehithlu KP, Wemlinger TA, Tejwani GA, Neff NH, Hadjiconstantinou M. Preproenkephalin mRNA and methionine-enkephalin content are increased in mouse striatum after treatment with nicotine. J Neurochem. 1995;64:1878–1883. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64041878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan BN, Cesselin F, Raghubir R, Reisine T, Bradley PB, Portoghese PS, Hamon M. International Union of Pharmacology. XII. Classification of opioid receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1996;48:567–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CT, Chavkin C, Milner TA. Opioid systems in the dentate gyrus. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:245–263. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filliol D, Ghozland S, Chluba J, Martin M, Matthes HW, Simonin F, Befort K, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Valverde O, Maldonado R, Kieffer BL. Mice deficient for delta- and mu-opioid receptors exhibit opposing alterations of emotional responses. Nat Genet. 2000;25:195–200. doi: 10.1038/76061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeote L, Berrendero F, Bura SA, Zimmer A, Maldonado R. Prodynorphin gene disruption increases the sensitivity to nicotine self-administration in mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:615–625. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianoulakis C. Endogenous opioids and addiction to alcohol and other drugs of abuse. Curr Top Med Chem. 2004;4:39–50. doi: 10.2174/1568026043451573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick S, Maisonneuve I, Raucci J, Archer S. Kappa opioid inhibition on morphine and cocine self-administration on rats. Brain Res. 1995;681:147–152. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00306-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, Oncken C, Azoulay S, Billing CB, Watsky EJ, Gong J, Williams KE, Reeves KR. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:47–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick DA, Rose J, Jarvik ME. Effect of naloxone on cigarette smoking. J Subst Abuse. 1988;1:153–159. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(88)80018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn EF, Carroll-Buatti M, Pasternak GW. Irreversible opiate agonists and antagonists: the 14-hydroxydihydromorphinone azines. J Neurosci. 1982;2:572–576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-05-00572.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasebe K, Kawai K, Suzuki T, Kawamura K, Tanaka T, Narita M, Nagase H. Possible pharmacotherapy of the opioid kappa receptor agonist for drug dependence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1025:404–413. doi: 10.1196/annals.1316.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder C, Shoaib M, Shippenberg TS. Differential role of delta-opioid receptors in the development and expression of behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;298:207–216. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00815-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder CA, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Shoaib M, Shippenberg TS. Development of behavioral sensitization to cocaine: influence of kappa opioid receptor agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:150–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdi AA, Dasgupta R, Kindy MS. Effect of nicotine use and withdrawal on brain preproenkephalin A mRNA. Brain Res. 1998;799:257–263. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdi AA, Pierzchala K, Marson L, Palkovits M, Van Loon GR. Nicotine-induced alteration in Tyr-Gly-Gly and Met-enkephalin in discrete brain nuclei reflects altered enkephalin neuron activity. Peptides. 1991;12:161–166. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(91)90183-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inan S, Lee DY, Liu-Chen LY, Cowan A. Comparison of the diuretic effects of chemically diverse kappa opioid agonists in rats: nalfurafine, U50,488H, and salvinorin A. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379:263–270. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0358-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismayilova N, Shoaib M. Alteration of intravenous nicotine self-administration by opioid receptor agonist and antagonists in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;210:211–220. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1845-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N, Pasternak GW. Binding of [3H]naloxonazine to rat brain membranes. Mol Pharmacol. 1984;26:477–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RM, Portoghese PS. 5′-Guanidinonaltrindole, a highly selective and potent kappa-opioid receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;396:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, Billing CB, Gong J, Reeves KR. Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:56–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karras A, Kane JM. Naloxone reduces cigarette smoking. Life Sci. 1980;27:1541–1545. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(80)90562-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A, de Wit H, Riley RC, Cao D, Niaura R, Hatsukami D. Efficacy of naltrexone in smoking cessation: a preliminary study and an examination of sex differences. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:671–682. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Meyer PJ. Naltrexone alteration of acute smoking response in nicotine-dependent subjects. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66:563–572. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura T, Ogawa M, Yamada Y. The individual and combined effects of U50,488, and flurbiprofen axetil on visceral pain in conscious rats. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1964–1966. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181a2b5e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen I, Pinker SR. Antagonism of swim-stress-induced antinociception by the delta-opioid receptor antagonist naltrindole in adult and young rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;100:685–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Rosen MI, O’Malley SS. Naloxone challenge in smokers. Preliminary evidence of an opioid component in nicotine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:663–668. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Merrer J, Becker JA, Befort K, Kieffer BL. Reward processing by the opioid system in the brain. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:1379–1412. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling GS, Simantov R, Clark JA, Pasternak GW. Naloxonazine actions in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986;129:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90333-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Caggiula AR, Palmatier MI, Donny EC, Sved AF. Cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior in rats: effect of bupropion, persistence over repeated tests, and its dependence on training dose. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;196:365–375. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0967-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Caggiula AR, Yee SK, Nobuta H, Poland RE, Pechnick RN. Reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior by drug-associated stimuli after extinction in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:417–425. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0134-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Palmatier MI, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Sved AF. Reinforcement enhancing effect of nicotine and its attenuation by nicotinic antagonists in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;194:463–473. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0863-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Palmatier MI, Caggiula AR, Sved AF, Donny EC, Gharib M, Booth S. Naltrexone attenuation of conditioned but not primary reinforcement of nicotine in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;202:589–598. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1335-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin DH, Lake JR, Carter VA, Cunningham JS, Wilson OB. Naloxone precipitates nicotine abstinence syndrome in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 1993;112:339–342. doi: 10.1007/BF02244930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A, Fox CA, Akil H, Watson SJ. Opioid-receptor mRNA expression in the rat CNS: anatomical and functional implications. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:22–29. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93946-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty MA, Erwin VG, Cornell K, Zgombick JM. Effects of nicotine on beta-endorphin, alpha MSH, and ACTH secretion by isolated perfused mouse brains and pituitary glands, in vitro. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1985;22:317–325. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90397-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa S, Suzuki T, Misawa M, Nagase H. Different roles of mu-, delta- and kappa-opioid receptors in ethanol-associated place preference in rats exposed to conditioned fear stress. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;368:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin JP, Marton-Popovici M, Chavkin C. Kappa opioid receptor antagonism and prodynorphin gene disruption block stress-induced behavioral responses. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5674–5683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05674.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhatre M, Holloway F. Micro1-opioid antagonist naloxonazine alters ethanol discrimination and consumption. Alcohol. 2003;29:109–116. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(03)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Mello NK, Linsenmayer DC, Jones RM, Portoghese PS. Kappa opioid antagonist effects of the novel kappa antagonist 5′-guanidinonaltrindole (GNTI) in an assay of schedule-controlled behavior in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163:412–419. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth-Coslett R, Griffiths RR. Naloxone does not affect cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1986;89:261–264. doi: 10.1007/BF00174355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olausson P, Jentsch JD, Taylor JR. Nicotine enhances responding with conditioned reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;171:173–178. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1575-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmatier MI, Evans-Martin FF, Hoffman A, Caggiula AR, Chaudhri N, Donny EC, Liu X, Booth S, Gharib M, Craven L, Sved AF. Dissociating the primary reinforcing and reinforcement-enhancing effects of nicotine using a rat self-administration paradigm with concurrently available drug and environmental reinforcers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:391–400. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierzchala K, Houdi AA, Van Loon GR. Nicotine-induced alterations in brain regional concentrations of native and cryptic Met- and Leu-enkephalin. Peptides. 1987;8:1035–1043. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(87)90133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF. Endogenous opioids and smoking: a review of progress and problems. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:115–130. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portoghese PS, Sultana M, Takemori AE. Naltrindole, a highly selective and potent non-peptide delta opioid receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;146:185–186. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90502-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiff BR, Dallery J. The generality of nicotine as a reinforcer enhancer in rats: effects on responding maintained by primary and conditioned reinforcers and resistance to extinction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;201:305–314. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray R, Jepson C, Patterson F, Strasser A, Rukstalis M, Perkins K, Lynch KG, O’Malley S, Berrettini WH, Lerman C. Association of OPRM1 A118G variant with the relative reinforcing value of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;188:355–363. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosecrans JA, Hendry JS, Hong JS. Biphasic effects of chronic nicotine treatment on hypothalamic immunoreactive beta-endorphin in the mouse. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1985;23:141–143. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rukstalis M, Jepson C, Strasser A, Lynch KG, Perkins K, Patterson F, Lerman C. Naltrexone reduces the relative reinforcing value of nicotine in a cigarette smoking choice paradigm. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;180:41–48. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippenberg TS, Zapata A, Chefer VI. Dynorphin and the pathophysiology of drug addiction. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;116:306–321. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder SH, Pasternak GW. Historical review: Opioid receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:198–205. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens WC, Jr, Jones RM, Subramanian G, Metzger TG, Ferguson DM, Portoghese PS. Potent and selective indolomorphinan antagonists of the kappa-opioid receptor. J Med Chem. 2000;43:2759–2769. doi: 10.1021/jm0000665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland G, Stapleton JA, Russell MA, Feyerabend C. Naltrexone, smoking behaviour and cigarette withdrawal. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;120:418–425. doi: 10.1007/BF02245813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Di Chiara G. A dopamine-mu1 opioid link in the rat ventral tegmentum shared by palatable food (Fonzies) and non-psychostimulant drugs of abuse. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:1179–1187. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trigo JM, Zimmer A, Maldonado R. Nicotine anxiogenic and rewarding effects are decreased in mice lacking beta-endorphin. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:1147–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS. The health consequences of smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. Department of Health and Human services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease and Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner JM, Drott JT, Sharik SS, Theberge CR, Sur C, Zeng Z, Williams DL, Hutson PH. Inhibition of glycine transporter 1 attenuates nicotine- but not food-induced cue-potentiated reinstatement for a response previously paired with sucrose. Behav Brain Res. 2010;207:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker BM, Zorrilla EP, Koob GF. Systemic kappa-opioid receptor antagonism by nor-binaltorphimine reduces dependence-induced excessive alcohol self-administration in rats. Addict Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters CL, Cleck JN, Kuo YC, Blendy JA. Mu-opioid receptor and CREB activation are required for nicotine reward. Neuron. 2005;46:933–943. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee S, Orio L, Ghirmai S, Cashman JR, Koob GF. Inhibition of kappa opioid receptors attenuated increased cocaine intake in rats with extended access to cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;205:565–575. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1563-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wewers ME, Dhatt R, Tejwani GA. Naltrexone administration affects ad libitum smoking behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;140:185–190. doi: 10.1007/s002130050756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong GY, Wolter TD, Croghan GA, Croghan IT, Offord KP, Hurt RD. A randomized trial of naltrexone for smoking cessation. Addiction. 1999;94:1227–1237. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.948122713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Domino EF. Tobacco/nicotine and endogenous brain opioids. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:1131–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrindast MR, Faraji N, Rostami P, Sahraei H, Ghoshouni H. Cross-tolerance between morphine- and nicotine-induced conditioned place preference in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;74:363–369. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]