Abstract

Background

CADASIL is a genetic vascular dementia caused by mutations in the Notch 3 gene on Chromosome 19. However, little is known about the mechanisms of vascular degeneration.

Methods

We characterized upstream components of Notch signaling pathways that may be disrupted in CADASIL, by measuring expression of insulin, IGF-1, and IGF-2 receptors, Notch 1, Notch 3, and aspartyl-(asparaginyl)-β-hydroxylase (AAH) in cortex and white matter from 3 CADASIL and 6 control brains. We assessed CADASIL-associated cell loss by measuring mRNA corresponding to neurons, oligodendroglia, and astrocytes, and indices of vascular degeneration by measuring smooth muscle actin (SMA) and endothelin-1 (ET-1) expression in isolated vessels. Immunohistochemical staining was used to assess SMA degeneration.

Results

Significant abnormalities including reduced cerebral white matter mRNA levels of Notch 1, Notch 3, AAH, SMA, IGF receptors, myelin-associated glycoproteins, and glial fibrillary acidic protein, and reduced vascular expression of SMA, IGF receptors, Notch 1 and Notch 3 were detected in CADASIL-lesioned brains. In addition, we found CADASIL-associated reductions in SMA, and increases in ubiquitin immunoreactivity in the media of white matter and meningeal vessels. No abnormalities in gene expression or immunoreactivity were observed in CADASIL cerebral cortex.

Conclusions

Molecular abnormalities in CADASIL are largely restricted to white matter and white matter vessels, corresponding to the distribution of neuropathological lesions. These preliminary findings suggest that CADASIL is mediated by both glial and vascular degeneration with reduced expression of IGF receptors and AAH, which regulate Notch expression and function.

Key Phrases: vascular dementia, Notch, white matter degeneration, aspartyl-(asparaginyl)-β-hydroxylase, human

Introduction

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is a genetic vascular dementia associated with degeneration of small blood vessels in brain, particularly those supplying subcortical white matter [1, 2]. The mean age at symptom onset is 45 years, and the mean age at death is 65. Migraine headaches are often the earliest symptoms, and disease progression is associated with transient ischemic attacks, stroke-like episodes, cerebral infarcts, and dementia [3–6]. Mood disorders, especially depression, occur in up to 30% of cases [6]. CADASIL is associated with missense mutations in the Notch 3 gene on chromosome 19 [1, 3]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows subcortical lacunar infarcts and extensive subcortical white matter hyper-intense signals on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images in the subcortical white matter [7], including the anterior temporal lobe, which has been shown to be a useful sign for the diagnosis of CADASIL [8]. Mutations often result in gain or loss of a cysteine residue in the extracellular domain of Notch protein [9, 10]. Although Notch transmembrane receptor family proteins are known to mediate signaling for a broad range of functions, including cell fate determination during development [11–17], it is not understood how mutation of Notch 3 leads to vascular degeneration, or why disease onset occurs relatively late in life.

Theories of CADASIL pathogenesis suggest that accumulation of mutated Notch 3 protein in the vicinity of smooth muscle cells leads to vascular degeneration and disease progression [2, 4, 18, 19]. However, supporting evidence is limited and inconclusive. We approached the question of CADASIL pathogenesis by investigating the potential roles of insulin and insulin-like growth factor signaling and aspartyl-(asparaginyl)-β-hydroxylase (AAH) expression due to their intimate relationship to Notch gene expression and signaling [20–22]. In this regard, insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) types 1 and 2 stimulate Notch and AAH [21–23]. AAH physically interacts with Notch and its ligand Jagged, and regulates their function through hydroxylation [20, 24, 25]. Upon activation and cleavage, the N-terminal fragment of Notch translocates to the nucleus where it regulates gene expression [26, 27]. Therefore insulin and IGF receptors and AAH are upstream regulators of Notch signaling and function. Experimental gene depletions of AAH and Notch produce similar phenotypes [20, 28].

One important function of AAH is to regulate cell motility [22, 23, 29–32], which is dependent upon continuous reorganization of cytoskeletal proteins [21]. Smooth muscle contraction and relaxation regulate blood flow, and these processes are mediated by continuous reorganization of cytoskeletal elements, namely smooth muscle actin, together with signaling through endothelial cells [33–35]. Previous studies demonstrated that both AAH and Notch signaling were regulated by insulin/IGF pathways [21, 22]. We hypothesize that vascular smooth muscle degeneration in the context of CADASIL-associated Notch 3 mutations is mediated by disruption of the insulin/IGF-AAH-Notch signaling axis. The current study examines expression of each component within this proposed axis, as well as the expression of genes reflecting brain cell profiles [36, 37], to determine whether other cell types, i.e. glia, endothelial cells, or neurons, are adversely affected and potentially vulnerable to degeneration in CADASIL.

Source of Materials and Methods

Source of Tissue

Fresh, snap-frozen post-mortem brain tissue from 3 patients with clinically, histopathologically, and in 2 cases genetically confirmed CADASIL (ages 64, 66, and 67), and 6 normal controls was obtained from the Brown University-Rhode Island Hospital Brain Bank [38]. The tissue was stored at −80°C. The 6 control patients, ages 62–72, were cognitively intact, and they had normal brains by macroscopic and histological examination.

Tissue Processing

One objective of these studies was to examine gene expression in separate samples of cortical and white matter tissue, and in micro-vessels isolated from cortical and white matter tissues. Therefore, cerebral cortex and white matter were separately dissected from frozen blocks of frontal and temporal lobe (3 samples per case). Portions of each were processed directly for RNA extraction. The remainder was used to isolate micro-vessels as previously described [39]. In brief, 5 gm of tissue were Dounce homogenized in 10 ml of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS) and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3000 rpm in a swinging bucket rotor. The pellets were washed 3 times by thoroughly resuspending them each in 10 ml PBS and centrifuging the samples as described. The final pellet was resuspended in 10 ml PBS and layered over 10 ml of 15% dextran cushion (15 g dextran in 100 ml PBS). Dextran (MW 35,000–45,000) was from Leuconostoc mesenteroides (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 55 minutes, and the resulting pellets were resuspended in 0.1 ml PBS and used for RNA isolation. Microvesels isolated using this procedure can be visualized by phase-contrast microscopy and demonstrated to contain variable size vessels with minimal contaminating cerebral tissue. In addition, the microvessel fractions are enriched for expression of vascular endothelial (Factor VIII) and smooth muscle (smooth muscle actin) proteins, as well as γ-glutamyl transpeptidase and alkaline phosphatase activities [40, 41]. In addition, the microvessel fractions had negligible expression of neuronal genes (Hu and tau).

Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) Assays

Brain tissue and isolated vessel samples were homogenized in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using a Polytron homogenizer (source). RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit and RNeasy Mini Spin Column (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration and purity were determined by measuring the absorbances at 260 and 280 nm. 2 µg RNA samples were reverse transcribed using random oligodeoxynucleotide primers and the 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis kit for RT-PCR (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). The resulting cDNA templates were used to measure mRNA expression by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) amplification [22, 42]. PCR amplifications were performed in triplicate with QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Mix (Qiagen Inc, Valencia, CA) and gene-specific primer pairs as previously published [37] or listed in Table 1. Amplified signals were detected continuously with the Mastercycler ep realplex instrument and software (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) as previously described [31]. Annealing temperatures were optimized using the temperature gradient program provided with the Mastercycler Ep realplex software (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). Relative mRNA abundance was calculated from the ng ratios of specific mRNA to 18S measured in the same samples, and those data were used for inter-group statistical comparisons. Negative control studies included template-free reactions.

Table 1.

Primers Used for Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR*

| mRNA | Primer | Sequence (5➇3) | Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (bp) | ||||

| Notch 1 | Forward | AGG ACC TCA TCA ACT CAC ACG C | 6038 | 117 |

| Notch 1 | Reverse | CGT TCT TCA GGA GCA CAA CTG C | 6154 | |

| Notch 3 | Forward | CGA TGT CAA CGA GTG TCT GTC G | 1368 | 102 |

| Notch 3 | Reverse | GTT CCT GTG AAG CCT GCC ATA C | 1469 | |

| AAH | Forward | GGG AGA TTT TAT TTC CAC CTG GG | 1650 | 254 |

| AAH | Reverse | CCT TTG GCT TTA TCC ATC ACT GC | 1903 |

Primer pairs used in qRT-PCR reactions to measure mRNA expression. The table lists the gene of interest, orientation of the primers, nucleic acid sequences of the primers, binding position within the transcript, and amplicon size in base pairs (bp).

Immunoistochemical Staining

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections (8 µM thick) of frontal lobe were immunostained to detect SMA or ubiquitin using mouse monoclonal antibodies. Prior to immunostaining, the deparaffinized, re-hydrated tissue sections were sequentially treated with 0.1 mg/ml saponin in phosphate buffered saline (10 mM sodium phosphate, 0.9% NaCl, pH 7.4; PBS), for 20 minutes at room temperature, followed by 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 minutes to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Non-specific binding sites were blocked using the Avidin-Biotin blocking reagents according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), followed by a 30-minute room temperature incubation with normal horse serum diluted 1:200 in SuperBlock-TBS (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL). After overnight incubation 4°C with 1 µg/ml of primary antibody, immunoreactivity was detected with biotinylated secondary antibody, avidin biotin horseradish peroxidase complex (ABC) reagents, and diaminobenzidine as the chromogen (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) [31]. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and examined by light microscopy.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed statistically using GraphPad Prism 5 software and inter-group comparisons were made using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

CADASIL-Associated Shifts in Cellular Biomarkers in Cerebral TIssue

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was used to measure Hu (neurons), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; astrocytes), myelin-associated glycoprotein-1 (MAG-1; oligodendrocytes), oligodendrocyte transcription factor 1 (Olig1), ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA1; microglia), endothelin-1 (ET-1; endothelial cells), and smooth muscle actin (SMA; vascular smooth muscle cells) in isolated samples of cortex (Table 2) and white matter (Table 3) from the frontal lobes. Previously, we used this approach to demonstrate pathologic shifts in cellular profiles in Alzheimer’s disease [36, 37]. In the current study, with the exception of GFAP which was significantly reduced in CADASIL, control and CADASIL-lesioned brains expressed similar and overlapping levels of all other mRNA transcripts in frontal cortex (Table 3). Reduced GFAP expression in cortex may reflect loss of astrocytes or impaired astrocyte function in CADASIL, despite the relative paucity of lesions in this structure. In contrast, the white matter of CADASIL-lesioned brains showed significant reductions in the expression of most genes examined, including GFAP, MAG-1, IBA1, ET-1, and SMA. Although Olig1 expression was also sharply reduced in CADASIL-lesioned white matter, the inter-group differences did not reach statistical significance due to broad variability in gene expression among controls. No significant alterations in Hu expression were detected in either cortex or white matter of CADASIL-lesioned brains. These findings reflect the extensive CADASIL-associated loss or functional impairments in mainly white matter glial and vascular elements. The relative preservation of Hu expression confirms that neurons are not primary targets of CADASIL-mediated degeneration.

Table 2.

Altered Gene Expression Levels in Frontal Cortex of CADASIL-Lesioned Brains

| Gene* | Control | CADASIL | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18S | 4.238 ± 0.592 | 4.286 ± 0.573 | |

| Hu | 0.264 ± 0.095 | 0.358 ± 0.116 | |

| MAG-1 | 0.649 ± 0.137 | 0.391 ± 0.187 | |

| OLIG1 | 0.137 ± 0.026 | 0.161 ± 0.042 | |

| GFA | 15.90 ± 5.278 | 6.675 ± 2.712 | 0.0250 |

| IBA1 | 0.030 ± 0.014 | 0.018 ± 0.010 | |

| ET-1 | 0.298 ± 0.110 | 0.144 ± 0.076 | |

| SMA | 0.156± 0.0622 | 0.066 ± 0.028 | |

| Insulin R | 0.008 ± 0.002 | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.0025 |

| IGF-1 R | 0.083 ± 0.026 | 0.011 ± 0.003 | 0.0002 |

| IGF-2R | 0.128 ± 0.011 | 0.013 ± 0.006 | 0.0002 |

| AAH | 0.391 ± 0.203 | 0.341 ± 0.171 | |

| Notch 1 | 0.567 ± 0.060 | 0.649 ± 0.120 | |

| Notch 3 | 0.039 ± 0.005 | 0.036 ± 0.005 |

Molecular profile of gene expression in frontal cortex of control and CADASIL-lesioned brains. RNA was extracted from micro-dissected tissue, reverse transcribed, and used to measure gene expression corresponding to 18S rRNA, Hu (neurons), myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG-1), oligodendrocytes (OLIG-1), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP-astrocytes), ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA1; microglia), endothelin-1 (ET-1; endothelial cells), smooth muscle actin (SMA), insulin receptor (R) IGF-1 receptor, IGF-2 receptor, aspartyl-asparaginyl-β-hydroxylase (AAH), Notch 1, and Notch 3 by quantitative PCR analysis. Gene expression levels were normalized to 18S rRNA measured in the same samples. Data depict mean ± S.E.M. and inter-group comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney U test. Significant P-values are indicated in the far right column.

Table 3.

Altered Gene Expression Levels in Frontal White Matter of CADASIL-Lesioned Brains

| Gene* | Control | CADASIL | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18S | 4.024 ± 0.458 | 4.025 ± 0.697 | |

| Hu | 0.1689 ± 0.068 | 0.1184 ± 0.066 | |

| MAG-1 | 0.6324 ± 0.141 | 0.0824 ± 0.055 | 0.0008 |

| OLIG1 | 0.1611 ± 0.066 | 0.0130 ± 0.0087 | 0.0028 |

| GFAP | 16.81 ± 5.73 | 2.941 ± 1.01 | 0.0012 |

| IBA1 | 0.0076 ± 0.002 | 0.0027 ± 0.0017 | 0.0078 |

| ET-1 | 0.1611 ± 0.047 | 0.0055 ± 0.002 | 0.0008 |

| SMA | 0.0294 ± 0.012 | 0.0020 ± 0.0008 | 0.0004 |

| Insulin R | 0.0006 ± 0.0001 | 0.0002 ± 0.0001 | 0.0253 |

| IGF-1 R | 0.0057 ± 0.0004 | 0.0035 ± 0.0017 | 0.0253 |

| IGF-2R | 0.0199 ± 0.0041 | 0.0054 ± 0.0033 | 0.0058 |

| AAH | 0.1589 ± 0.032 | 0.0252 ± 0.0145 | 0.001 |

| Notch 1 | 0.11 ± 0.029 | 0.038 ± 0.006 | <0.0001 |

| Notch 3 | 0.0195 ± 0.004 | 0.0041 ± 0.0011 | <0.0001 |

Molecular profile of gene expression in frontal white matter of control and CADASIL-lesioned brains. RNA was extracted from micro-dissected tissue, reverse transcribed, and used to measure gene expression corresponding to 18S rRNA, Hu (neurons), myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG-1), oligodendrocytes (OLIG-1), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP-astrocytes), ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA1, microglia), endothelin-1 (ET-1; endothelial cells), smooth muscle actin (SMA), insulin receptor (R) IGF-1 receptor, IGF-2 receptor, aspartyl-asparaginyl-β-hydroxylase (AAH), Notch 1, and Notch 3 by quantitative PCR analysis. mRNA levels were normalized to 18S rRNA measured in the same samples. Data depict mean ± S.E.M. and inter-group comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney U test. Significant P-values are indicated in the far right column.

Molecular Analysis of Notch Genes and Upstream Genes Regulating Notch Expression and Function

Insulin, IGF-1, and IGF-2 stimulations regulate AAH expression [21, 22, 29, 30], and AAH’s catalytic activity regulates Notch [21]. Therefore, signals transmitted through insulin, IGF-1, or IGF-2 receptors and AAH represent regulatory mechanisms for Notch. We used qRT-PCR analysis to measure mRNA levels of insulin, IGF-1, and IGF-2 receptors, AAH, Notch 1 and Notch 3 in our tissue samples. Notch 1 expression was measured because this gene is not mutated in CADASIL, but could potentially subserve failing functions of Notch 3. In cortical tissue, we detected significantly reduced levels of insulin, IGF-1, and IGF-2 receptor expression in brains from patients with CADASIL (Tables 2 and 3). In contrast, the mRNA levels corresponding to AAH, Notch 1, and Notch 3 were similar in control and CADASIL frontal cortex. With regard to white matter, we detected significantly reduced levels of genes encoding the insulin, IGF-1, and IGF-2 receptors, AAH, and Notch 3, but similar levels of Notch 1 in CADASIL relative to control brains (Tables 2 and 3).

Molecular Characterization of Vascular Pathology in CADASIL

To assess the degree to which the abnormalities detected in tissue homogenates were due to arteriopathy, we isolated cerebral microvessels from cortical and white matter tissue and extracted RNA for qRT-PCR analysis. With regard to cortical vessels, there were no significant differences in the expression levels of insulin, IGF-1, or IGF-2 receptors, AAH, or SMA (Table 4). Although the mean levels of IGF-1 and IGF-2 receptors were much lower in CADASIL compared with control cortical vessels, the broad variability in gene expression among control samples rendered the inter-group differences not statistically significant. However, CADASIL cortical micro-vessels had significantly increased expression of Notch 1, and reduced expression of ET-1 and Notch 3 relative to control (Table 4a). With regard to white matter micro-vessels, the qRT-PCR analysis demonstrated significantly reduced mRNA levels of insulin receptor, AAH, SMA, and Notch 3, and significantly increased expression of Notch 1 in CADASIL relative to control samples (Table 4). IGF-2 receptor expression was also sharply reduced in CADASIL white matter micro-vessels, but high intra-group variability among controls rendered the inter-group difference not statistically significant. IGF-1 receptor and ET-1 were expressed at similar levels in CADASIL and control white matter micro-vessel samples.

Table 4.

Altered Micro-Vascular Gene Expression in of CADASIL-Lesioned Brains

| a) Frontal Cortex | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | Control | CADASIL | P-Value |

| 18S | 0.2790 ± 0.1230 | 0.4735 ± 0.2030 | |

| ET-1 | 0.0052 ± 0.0014 | 0.0015 ± 0.0007 | 0.033 |

| SMA | 0.1612 ± 0.0530 | 0.1093 ± 0.0200 | |

| Notch 1 | 0.0161 ± 0.0139 | 0.1765 ± 0.1266 | 0.021 |

| Notch 3 | 0.0569 ± 0.0342 | 0.0085 ± 0.0042 | 0.048 |

| Insulin R | 0.0150 ± 0.0088 | 0.0099 ± 0.0093 | |

| IGF-1 R | 0.0622 ± 0.0392 | 0.0024 ± 0.0013 | |

| IGF-2 R | 0.0117 ± 0.0090 | 0.0011 ± 0.0007 | |

| AAH | 0.0260 ± 0.0088 | 0.0214 ± 0.0106 | |

| b) Frontal White Matter | |||

| mRNA | Control | CADASIL | P-Value |

| 18S | 0.3438 ± 0.0952 | 0.4213 ± 0.1806 | |

| Insulin R | 0.0032 ± 0.0013 | 0.0001 ± 0.0001 | 0.001 |

| IGF-1 R | 0.0007 ± 0.0004 | 0.0008 ± 0.0003 | |

| IGF-2 R | 0.0036 ± 0.0023 | 0.0003 ± 0.0001 | |

| ET-1 | 0.0162 ± 0.0060 | 0.0201 ± 0.0115 | |

| SMA | 0.1799 ± 0.0764 | 0.0020 ± 0.0010 | 0.001 |

| Notch 1 | 0.0057 ± 0.0033 | 0.0186 ± 0.0060 | 0.033 |

| Notch 3 | 0.0320 ± 0.0065 | 0.0038 ± 0.0022 | 0.001 |

| AAH | 0.0252 ± 0.0133 | 0.0002 ± 0.0001 | 0.001 |

Micro-vascular expression of ET-1, SMA, Notch, and genes that regulate Notch expression and function. Micro-vessels were isolated from control and CADASIL-lesioned fresh frozen frontal cortex and white matter. RNA was extracted, reverse transcribed, and used to measure gene expression corresponding to ET-1, SMA, Notch 1, Notch 3, insulin, IGF-1, and IGF-2 receptors, and AAH by qRT-PCR analysis. mRNA levels were normalized to 18S rRNA measured in the same samples. Data depict mean ± S.E.M. and inter-group comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney U test. Significant P-values are indicated in the far right column.

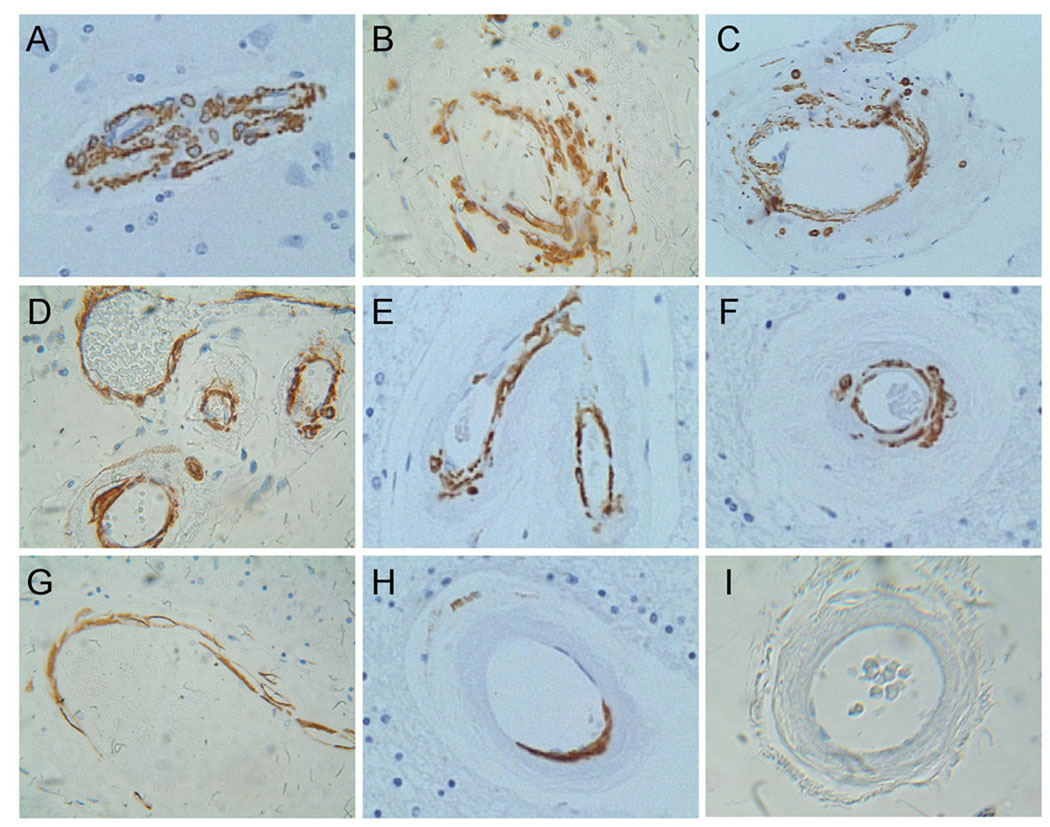

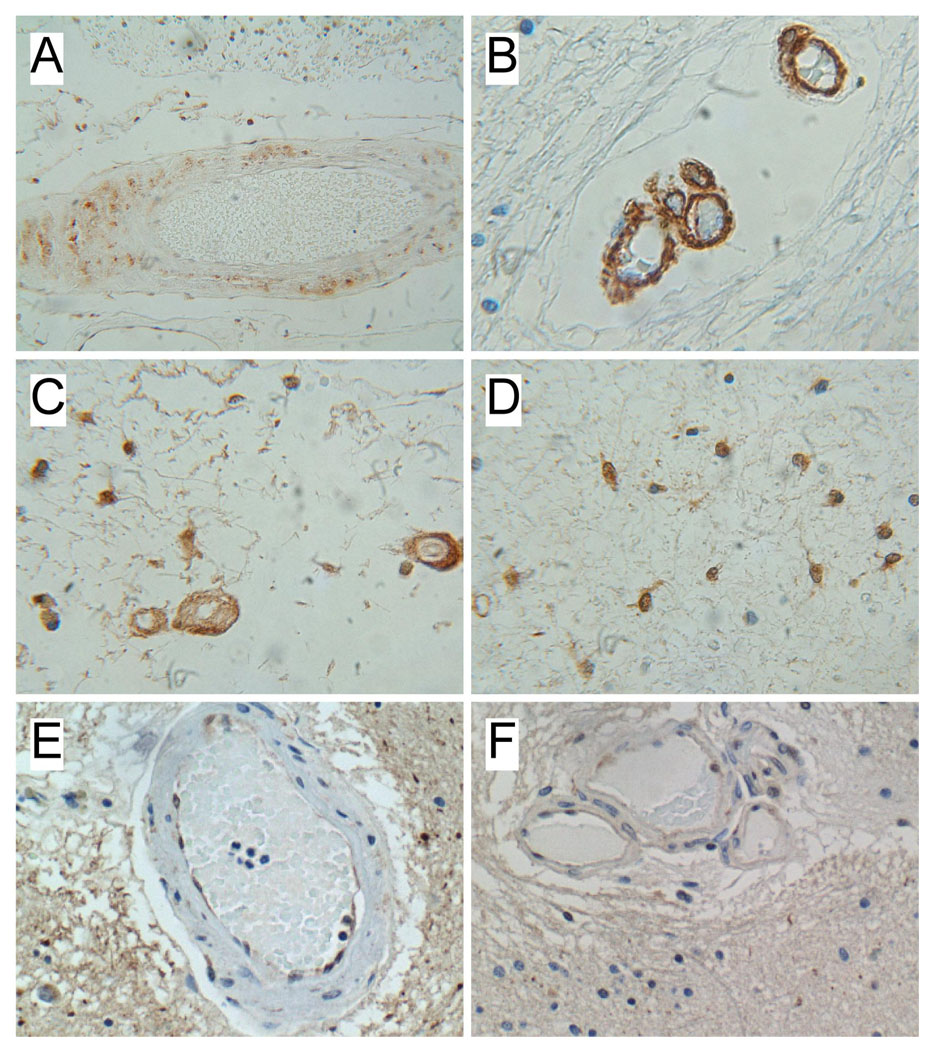

Corresponding with the mRNA studies, immunohistochemical staining demonstrated reduced levels of SMA immunoreactivity in the media of small and medium size arteries in both white matter and leptomeninges. In CADASIL-lesioned brains, the vascular SMA immunoreactivity often exhibited an irregular and fragmented pattern compared with smooth uniform labeling of control arteries (Figure 1). In addition, CADASIL vasculopathy was associated with increased ubiquitin immunoreactivity localized mainly in the media, but also the adventitia and in white matter glial cytoplasm (Figure 2). Cortical vessels had similar levels and distributions of SMA immunoreactivity, and no distinction in ubiquitin immunoreactivity between CADASIL-lesioned and control brains.

Figure 1.

Altered SMA immunoreactivity in CADASIL white matter vessels. Histological sections of (A) control and (B–H) CADASIL brains were immunostained with monoclonal antibodies to SMA. Immunoreactivity was detected with biotinylated secondary antibody, followed by horseradish peroxidase conjugated avidin-biotin complexes and diaminobenzidine substrate. Sections were counterstained lightly with hematoxylin. Note uniform dense labeling for SMA in control vessels and variable degrees of fragmented and incomplete labeling of CADASIL vessels. Panel I shows a negative control reaction in which the primary antibody was omitted from the reaction.

Figure 2.

Increased ubiquitin immunoreactivity in CADASIL white matter vessels. Paraffin-embedded histological sections of (A–D) CADASIL and (E, F) control frontal lobe white matter were immunostained with monoclonal antibodies to ubiquitin. Immunoreactivity was detected with biotinylated secondary antibody, followed by horseradish peroxidase conjugated avidin-biotin complexes and diaminobenzidine substrate. Sections were counterstained lightly with hematoxylin. Note ubiquitin immunoreactivity in the media of (A) medium-size and (B, C) small CADASIL white matter vessels, as well as in (C, D) glial cells. (E, F) Control brain vessels exhibited focal labeling of endothelial cells, which appeared to be non-specific, whereas ubiquitin immunoreactivity was not detected in the media of control white matter vessels.

Discussion

CADASIL is caused by Notch 3 missence mutations that lead to progressive cerebral arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Together with a clinical history of step-wise neuro-cognitive impairment leading to subcortical dementia, CADASIL is characteristically associated with signal hyper-intensities localized in white matter on FLAIR and T2-weighted MRI. Despite the known linkage to Notch 3 mutations, little information is available regarding disease pathogenesis and progression. Our previous investigations related to insulin/IGF regulation of AAH, and AAH regulation of Notch signaling [21, 22, 30], led us to consider the potential roles of impaired insulin/IGF signaling and AAH expression in the context of CADASIL-mediated neurodegeneration. To explore this problem, we interrogated a limited number of well-characterized human cases of CADASIL utilizing mainly a molecular approach. The investigations were extended by characterizing gene expression in micro-vessels isolated from cerebral cortex and white matter tissue. The overall findings herein reinforce the concept that CADASIL represents a subcortical arteriopathy with leukoencephalopathy, but also highlight that CADASIL may represent a degenerative disease with both glial and vascular targets resulting in arteriopathy and chronic injury to white matter mediated by ischemia and impaired myelin maintenance. The limitation of this study is that we only had 3 CADASIL cases in which sufficient fresh frozen intact brain tissue was available for study. Correspondingly have interpreted the data with caution as the findings should be regarded as preliminary. Moreover, as the investigations were cross-sectional rather than longitudinal, it is difficult to know with certainty whether the glial degeneration is a consequence of the vascular disease, or if both glial and vascular degeneration represent intrinsic abnormalities directly related to Notch 3 mutation. Finally, the main methods of investigation were qRT-PCR and immunohistochemical staining which do not cover all potential means of detecting abnormalities in the brain.

Three unique aspects of this study were that we: 1) examined gene expression in dissected cortex and underlying white matter; 2) measured gene expression in isolated cerebrovascular tissue; and 3) explored abnormalities in upstream mechanisms that regulate Notch signaling, i.e. insulin/IGF receptor expression and AAH expression. Through the use of cellular gene expression profiling to measure relative levels of Hu, GFAP, MAG-1/Olig1, SMA, and ET-1, corresponding to neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells, respectively, we previously demonstrated selective loss or relative increases in different cell types associated with neurodegeneration in humans and experimental models [36, 37, 43]. In the present study, with the exception of GFAP, gene expression corresponding to different cell types in the cortex was not significantly altered in CADASIL. In contrast, genes reflecting astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells were all reduced in CADASIL white matter, suggesting that CADASIL results in loss of both glial and vascular elements, mainly in white matter. The relatively modest shifts in cellular gene expression in cortex relative to white matter in CADASIL correspond with the preferential distribution of lesions in white matter. The finding that GFAP expression was also reduced in CADASIL cortex supports the notion that glial cells are targets of CADASIL degeneration and contribute to cortical atrophy in the later stages of disease [44, 45]. On the other hand, the relative preservation of Hu expression in both cortex and white matter indicates that neurons are not primary targets of CADASIL degeneration. Given the fact that not all genes were reduced in expression indicates that the abnormalities detected in CADASIL-lesioned brains were not non-specific. Moreover, normalizing gene expression to rRNA corrects for tissue loss and enables one to examine shifts in gene expression normalized to cell number.

White matter arteriopathy in CADASIL was associated with reduced SMA and ET-1 expression in white matter, and the leukoencephalopathy was associated with reduced expression of genes corresponding to astrocytes and oligodendroglia. These abnormalities correspond with loss of smooth muscle cells and fibrotic transformation of the media in white matter vessels, and the myelin pallor, hypomyelination, hypocellularity, and incomplete infarction observed in CADASIL, particularly in the late stages of disease. Moreover, the immunohistochemical staining studies showing SMA fragmentation and increased ubiquitin immunoreactivity localized in vessel walls and white matter glia lend further support to the argument that CADASIL is actually a gliovascular degenerative disease rather than exclusively an arteriopathy, i.e. glia and arterial smooth muscle cells are disease targets in CADASIL. Loss of oligodendrocytes could contribute to myelin pallor, and white matter fiber degeneration, including the hypocellularity. Loss of astrocytes or astrocyte function could compromise maintenance of the blood-brain barrier, modulation of neurotransmitter, including glutamate, reuptake and release, regulation of extracellular ion balance and calcium flux, and support for the structural integrity of the brain, including connections between cortex and subcortical and brainstem nuclei.

To examine the role of abnormal upstream regulators of Notch signaling, we measured expression of insulin, IGF-1, and IGF-2 receptors. Activation of the related downstream pathways leads to increased AAH expression and catalytic activity [21], which in turn results in increased Notch signaling [21, 22]. In contrast, inhibition of signaling through insulin/IGF receptors and AAH decreases Notch expression and function [21, 31]. AAH interacts with and hydroxylates Notch, leading to Notch cleavage, and attendant translocation of its N-terminal fragment to the nucleus to regulate gene expression [20, 24, 46]. Our studies revealed significant inhibition of insulin, IGF-1, and/or IGF-2 receptor expression in CADASIL cortex and white matter. Since myelin synthesis and maintenance are regulated by IGF signaling [47, 48], the finding of reduced expression of IGF receptor genes in CADASIL white matter could account for the myelin pallor and hypomyelination observed in regions of incomplete infarction.

To correlate molecular abnormalities with disease pathogenic mechanisms, it is important to note that since CADASIL neurodegenerative lesions are mainly localized in white matter, yet reduced insulin/IGF receptor expression was evident in both cortex and white matter, impaired signaling through these receptors is likely to be insufficient to cause pathology. However, one major distinction between cortex and white matter was the significant down-regulation of AAH in white matter but not in cortex. Since AAH regulates Notch function, conceivably, impaired signaling through insulin/IGF receptors that leads to decreased AAH expression may represent the critical variable resulting in CADASIL-associated pathology. In this regard, effects of the already impaired Notch 3 function caused by genetic missense mutations may be exacerbated by reduced levels of AAH expression and function, promoted by decreased expression and signaling through insulin/IGF receptors. Because AAH also regulates Notch 1 [21, 31], we investigated whether Notch 1, although not mutated, might be altered in expression in association with CADASIL. The finding of increased Notch 1 expression in CADASIL was unexpected, but could represent a compensatory response to the Notch 3 mutation. In future studies it would be of interest to determine if the factor precipitating CADASIL-associated degeneration vis-à-vis up-regulated Notch 1 expression is inhibition of AAH.

Gene expression analysis of isolated micro-vessels was informative because it demonstrated that the reduced levels of IGF-1 and IGF-2 receptors in cortical and white matter tissue were probably attributable to abnormalities in both vascular and non-vascular, i.e. parenchymal tissue, whereas the reductions in insulin receptor and AAH expression in white matter were caused by abnormalities in the blood vessels alone. In addition, the “compensatory” increases in Notch 1 and down-regulated Notch 3 expression were detected in both cortical and white matter vessels, indicating that these abnormalities in Notch expression and function are indeed features of CADASIL arteriopathy. However, the data do not exclude the possibility that Notch gene expression is also altered in non-vascular cells in CADASIL-lesioned brains.

The roles of Notch signaling in relation to glial and vascular functions in adult brains are not understood. Nonetheless, given its role in cytoskeletal organization, remodeling, tissue morphogenesis, and cell migration during development, deficiencies in Notch expression could lead to impaired function of vascular and glial cytoskeletons. Collapse and disarray of vascular SMA could lead to disruption, aggregation, accumulation, and eventual targeting of SMA protein for degradation via the ubiquitin-mediated pathway. In CADASIL, granular osmiophilic material (GOM) deposited around smooth muscle cells represents a virtually pathognomonic ultrastructural feature of the disease [8, 9]. Recent studies demonstrated that GOMs exhibit Notch 3 (ectodomain of the protein) immunoreactivity [49], suggesting that accumulation of the abnormal Notch protein contributes to smooth muscle degeneration. Correspondingly, we detected fragmentation and reduced levels of SMA, and increased ubiquitin immunoreactivity in the media of white matter vessels in CADASIL, but not control brains. Similarly, collapse of glial cytoskeletal elements secondary to impaired signaling through the IGF-AAH-Notch pathway could lead to degradation and ubiquitination of glial cytoskeletal proteins. Increased ubiquitination of proteins leads to oxidative stress and cell death via apoptosis or mitochondrial pathways [50–52]. In essence, increased ubiquitin tagging of vascular and glial cytoskeletal proteins secondary to impaired Notch signaling and aberrant Notch protein accumulation could result in death of smooth muscle and glial cells, corresponding with the known histopathological features of CADASIL.

Acknowledgments

Supported by AA-11431, AA-12908, K24-AA-16126, NIMH-START-MH, AG023916, and RR15578 from the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Salloway serves on the scientific advisory boards of Elan Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi-Aventis, Pfizer Inc, Eisai Inc, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. He serves as Associate Editor for Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences; receives publishing royalties for The Frontal Lobes and Neuropsychiatric Illness (American Psychiatric Press Inc., 2001) and The Neuropsychiatry of Limbic and Subcortical Disorders (American Psychiatric Press Inc., 1997) Vascular Dementia (Humana Press, 2004); receives honoraria from Eisai Inc., Pfizer Inc, Novartis, Forest Laboratories Inc., Elan Pharmaceuticals, and Athena Diagnostics, Inc.; holds corporate appointments with Merck Serono and Medivation, Inc.; receives research support from Elan Pharmaceuticals, Wyeth, Janssen Alzheimer’s Immunotherapy, Pfizer Inc, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Eisai Inc.; received research support from Myriad Genetics, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline; Neurochem-Alzhemed, Cephalon, Inc., Forest Laboratories Inc., and Voyager; receives research support from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network [NIA 1U01AG032438] received research support from Aging Brain: DTI, Subcortical Ischemia and Behavior [AG023916 and RR15578]; and receives research support from The Norman and Rosalie Fain Family Foundation and the Champlin Foundation.

Drs. Brennan-Krohn, Correia, Dong, and de la Monte have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Tournier-Lasserve E, Joutel A, Melki J, Weissenbach J, Lathrop GM, Chabriat H, Mas JL, Cabanis EA, Baudrimont M, Maciazek J, et al. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy maps to chromosome 19q12. Nat Genet. 1993;3:256–259. doi: 10.1038/ng0393-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joutel A, Corpechot C, Ducros A, Vahedi K, Chabriat H, Mouton P, Alamowitch S, Domenga V, Cecillion M, Marechal E, Maciazek J, Vayssiere C, Cruaud C, Cabanis EA, Ruchoux MM, Weissenbach J, Bach JF, Bousser MG, Tournier-Lasserve E. Notch3 mutations in CADASIL, a hereditary adult-onset condition causing stroke and dementia. Nature. 1996;383:707–710. doi: 10.1038/383707a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chabriat H, Vahedi K, Iba-Zizen MT, Joutel A, Nibbio A, Nagy TG, Krebs MO, Julien J, Dubois B, Ducrocq X, et al. Clinical spectrum of CADASIL: a study of 7 families. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Lancet. 1995;346:934–939. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91557-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dichgans M, Mayer M, Uttner I, Bruning R, Muller-Hocker J, Rungger G, Ebke M, Klockgether T, Gasser T. The phenotypic spectrum of CADASIL: clinical findings in 102 cases. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:731–739. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salloway S, Brennan-Krohn TSC, Mellion M, de la Monte S. CADASIL: A genetic model of arteriolar degeneration, white matter injury, and dementia in later life. In: Miller B, Boeve B, editors. Behavioral Neurology of Dementia. New York: Cambridge University; 2009. pp. 329–344. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salloway S, Desbiens S. CADASIL and Other Genetic Causes of Stroke and Vascular Dementia. In: Paul R, Cohen R, Ott B, Salloway S, editors. Vascular Dementia: Cerebrovascular Mechanisms and Clinical Management. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2004. pp. 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto Y, Ihara M, Tham C, Low RW, Slade JY, Moss T, Oakley AE, Polvikoski T, Kalaria RN. Neuropathological correlates of temporal pole white matter hyperintensities in CADASIL. Stroke. 2009;40:2004–2011. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.528299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markus HS, Martin RJ, Simpson MA, Dong YB, Ali N, Crosby AH, Powell JF. Diagnostic strategies in CADASIL. Neurology. 2002;59:1134–1138. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.8.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joutel A, Andreux F, Gaulis S, Domenga V, Cecillon M, Battail N, Piga N, Chapon F, Godfrain C, Tournier-Lasserve E. The ectodomain of the Notch3 receptor accumulates within the cerebrovasculature of CADASIL patients. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:597–605. doi: 10.1172/JCI8047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donahue CP, Kosik KS. Distribution pattern of Notch3 mutations suggests a gain-of-function mechanism for CADASIL. Genomics. 2004;83:59–65. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bray SJ. Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nrm2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehebauer M, Hayward P, Arias AM. Notch, a universal arbiter of cell fate decisions. Science. 2006;314:1414–1415. doi: 10.1126/science.1134042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez SL, Paganelli AR, Siri MV, Ocana OH, Franco PG, Carrasco AE. Notch activates sonic hedgehog and both are involved in the specification of dorsal midline cell-fates in Xenopus. Development. 2003;130:2225–2238. doi: 10.1242/dev.00443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lutolf S, Radtke F, Aguet M, Suter U, Taylor V. Notch1 is required for neuronal and glial differentiation in the cerebellum. Development. 2002;129:373–385. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patten BA, Peyrin JM, Weinmaster G, Corfas G. Sequential signaling through Notch1 and erbB receptors mediates radial glia differentiation. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6132–6140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-14-06132.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solecki DJ, Liu XL, Tomoda T, Fang Y, Hatten ME. Activated Notch2 signaling inhibits differentiation of cerebellar granule neuron precursors by maintaining proliferation. Neuron. 2001;31:557–568. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinmaster G. The ins and outs of notch signaling. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;9:91–102. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bianchi S, Dotti MT, Federico A. Physiology and pathology of notch signalling system. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207:300–308. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalimo H, Ruchoux MM, Viitanen M, Kalaria RN. CADASIL: a common form of hereditary arteriopathy causing brain infarcts and dementia. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:371–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00451.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dinchuk JE, Focht RJ, Kelley JA, Henderson NL, Zolotarjova NI, Wynn R, Neff NT, Link J, Huber RM, Burn TC, Rupar MJ, Cunningham MR, Selling BH, Ma J, Stern AA, Hollis GF, Stein RB, Friedman PA. Absence of post-translational aspartyl beta-hydroxylation of epidermal growth factor domains in mice leads to developmental defects and an increased incidence of intestinal neoplasia. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12970–12977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantarini MC, de la Monte SM, Pang M, Tong M, D’Errico A, Trevisani F, Wands JR. Aspartyl-asparagyl beta hydroxylase over-expression in human hepatoma is linked to activation of insulin-like growth factor and notch signaling mechanisms. Hepatology. 2006;44:446–457. doi: 10.1002/hep.21272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lahousse SA, Carter JJ, Xu XJ, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Differential growth factor regulation of aspartyl-(asparaginyl)-beta-hydroxylase family genes in SH-Sy5y human neuroblastoma cells. BMC Cell Biol. 2006;7:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-7-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavaissiere L, Jia S, Nishiyama M, de la Monte S, Stern AM, Wands JR, Friedman PA. Overexpression of human aspartyl(asparaginyl)beta-hydroxylase in hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1313–1323. doi: 10.1172/JCI118918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dinchuk JE, Henderson NL, Burn TC, Huber R, Ho SP, Link J, O’Neil KT, Focht RJ, Scully MS, Hollis JM, Hollis GF, Friedman PA. Aspartyl beta -hydroxylase (Asph) and an evolutionarily conserved isoform of Asph missing the catalytic domain share exons with junctin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39543–39554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006753200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monkovic DD, VanDusen WJ, Petroski CJ, Garsky VM, Sardana MK, Zavodszky P, Stern AM, Friedman PA. Invertebrate aspartyl/asparaginyl beta-hydroxylase: potential modification of endogenous epidermal growth factor-like modules. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;189:233–241. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91549-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kopan R, Schroeter EH, Weintraub H, Nye JS. Signal transduction by activated mNotch: importance of proteolytic processing and its regulation by the extracellular domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1683–1688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schroeter EH, Kisslinger JA, Kopan R. Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature. 1998;393:382–386. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de La Coste A, Freitas AA. Notch signaling: distinct ligands induce specific signals during lymphocyte development and maturation. Immunol Lett. 2006;102:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carter JJ, Tong M, Silbermann E, Lahousse SA, Ding FF, Longato L, Roper N, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Ethanol impaired neuronal migration is associated with reduced aspartyl-asparaginyl-beta-hydroxylase expression. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:303–315. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0377-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de la Monte SM, Tamaki S, Cantarini MC, Ince N, Wiedmann M, Carter JJ, Lahousse SA, Califano S, Maeda T, Ueno T, D’Errico A, Trevisani F, Wands JR. Aspartyl-(asparaginyl)-beta-hydroxylase regulates hepatocellular carcinoma invasiveness. J Hepatol. 2006;44:971–983. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de la Monte SM, Tong M, Carlson RI, Carter JJ, Longato L, Silbermann E, Wands JR. Ethanol inhibition of aspartyl-asparaginyl-beta-hydroxylase in fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: potential link to the impairments in central nervous system neuronal migration. Alcohol. 2009;43:225–240. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sepe PS, Lahousse SA, Gemelli B, Chang H, Maeda T, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Role of the aspartyl-asparaginyl-beta-hydroxylase gene in neuroblastoma cell motility. Lab Invest. 2002;82:881–891. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000020406.91689.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dudek SM, Garcia JG. Cytoskeletal regulation of pulmonary vascular permeability. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1487–1500. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li S, Moon JJ, Miao H, Jin G, Chen BP, Yuan S, Hu Y, Usami S, Chien S. Signal transduction in matrix contraction and the migration of vascular smooth muscle cells in three-dimensional matrix. J Vasc Res. 2003;40:378–388. doi: 10.1159/000072702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang DD, Anfinogenova Y. Physiologic properties and regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in vascular smooth muscle. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2008;13:130–140. doi: 10.1177/1074248407313737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rivera EJ, Goldin A, Fulmer N, Tavares R, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and function deteriorate with progression of Alzheimer’s disease: link to brain reductions in acetylcholine. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;8:247–268. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steen E, Terry BM, Rivera EJ, Cannon JL, Neely TR, Tavares R, Xu XJ, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and signaling mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease--is this type 3 diabetes? J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;7:63–80. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lahousse SA, Stopa EG, Mulberg AE, de la Monte SM. Reduced expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene in the hypothalamus of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5:455–462. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McNeill AM, Zhang C, Stanczyk FZ, Duckles SP, Krause DN. Estrogen increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase via estrogen receptors in rat cerebral blood vessels: effect preserved after concurrent treatment with medroxyprogesterone acetate or progesterone. Stroke. 2002;33:1685–1691. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000016325.54374.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costello P, Del Maestro R. Human cerebral endothelium: isolation and characterization of cells derived from microvessels of non-neoplastic and malignant glial tissue. J Neurooncol. 1990;8:231–243. doi: 10.1007/BF00177356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuji T, Mimori Y, Nakamura S, Kameyama M. A micromethod for the isolation of large and small microvessels from frozen autopsied human brain. J Neurochem. 1987;49:1796–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb02438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de la Monte SM, Tong M, Cohen AC, Sheedy D, Harper C, Wands JR. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor resistance in alcoholic neurodegeneration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1630–1644. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00731.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lester-Coll N, Rivera EJ, Soscia SJ, Doiron K, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Intracerebral streptozotocin model of type 3 diabetes: Relevance to sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:13–33. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters N, Holtmannspotter M, Opherk C, Gschwendtner A, Herzog J, Samann P, Dichgans M. Brain volume changes in CADASIL: a serial MRI study in pure subcortical ischemic vascular disease. Neurology. 2006;66:1517–1522. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216271.96364.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tatsch K, Koch W, Linke R, Poepperl G, Peters N, Holtmannspoetter M, Dichgans M. Cortical hypometabolism and crossed cerebellar diaschisis suggest subcortically induced disconnection in CADASIL: an 18F-FDG PET study. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:862–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Treves S, Feriotto G, Moccagatta L, Gambari R, Zorzato F. Molecular cloning, expression, functional characterization, chromosomal localization, and gene structure of junctate, a novel integral calcium binding protein of sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum membrane. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39555–39568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chesik D, De Keyser J, Wilczak N. Insulin-like growth factor system regulates oligodendroglial cell behavior: therapeutic potential in CNS. J Mol Neurosci. 2008;35:81–90. doi: 10.1007/s12031-008-9041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Joseph D’Ercole A, Ye P. Expanding the mind: insulin-like growth factor I and brain development. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5958–5962. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ishiko A, Shimizu A, Nagata E, Takahashi K, Tabira T, Suzuki N. Notch3 ectodomain is a major component of granular osmiophilic material (GOM) in CADASIL. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112:333–339. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goldbaum O, Richter-Landsberg C. Proteolytic stress causes heat shock protein induction, tau ubiquitination, and the recruitment of ubiquitin to tau-positive aggregates in oligodendrocytes in culture. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5748–5757. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1307-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Olanow CW. The pathogenesis of cell death in Parkinson’s disease--2007. Mov Disord. 2007;22(Suppl 17):S335–S342. doi: 10.1002/mds.21675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uchiyama Y, Koike M, Shibata M. Autophagic neuron death in neonatal brain ischemia/hypoxia. Autophagy. 2008;4:404–408. doi: 10.4161/auto.5598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]