Abstract

A developmental cascade model of early emotional and social competence predicting later peer acceptance was examined in a community sample of 440 children across the ages of 2 to 7. Children’s externalizing behavior, emotion regulation, social skills within the classroom and peer acceptance were examined utilizing a multitrait-multimethod approach. A series of longitudinal cross-lag models that controlled for shared rater variance were fit using structural equation modeling. Results indicated there was considerable stability in children’s externalizing behavior problems and classroom social skills over time. Contrary to expectations, there were no reciprocal influences between externalizing behavior problems and emotion regulation, though higher levels of emotion regulation were associated with decreases in subsequent levels of externalizing behaviors. Finally, children’s early social skills also predicted later peer acceptance. Results underscore the complex associations among emotional and social functioning across early childhood.

Conceptual models of child development and adaptive functioning have often approached the understanding of early competency by examining within domain predictors of developmental phenomena or have focused on stability of early emerging skills (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker 2006; Tremblay, 2003). However, the significance of cross-domain influences (Calkins & Bell, 2010) and bidirectional processes (Masten et al., 2005) has recently garnered attention, particularly within the field of developmental psychopathology, because of the promise that such approaches offer an understanding of how early developmental phenomena influence and are influenced by separate, but perhaps related, processes. This approach is particularly useful in trying to understand complex developmental phenomena, like social competence, psychological functioning, and academic achievement outcomes that are clearly the product of numerous skills and abilities that likely emerge over time and may operate bidirectionally (Burt, Obradovic, Long, & Masten, 2008; Howse, Calkins, Anastopolous, Keane, & Shelton, 2003). A developmental psychopathology perspective, advocating an organizational view of development in which multiple factors, or levels of a given factor, are considered in the context of one another, rather than in isolation (Cicchetti & Dawson, 2002; Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1996; Cicchetti & Schneider-Rosen, 1986) is consistent with such “cascade” models of early development. Cascade models of early development also have the potential to meet one of the fundamental tenets of developmental psychopathology, which is to understand pathways to both typical and atypical outcomes.

Early social competence and successful peer relationships have long been considered a hallmark of adaptive functioning in early childhood. For example, numerous negative outcomes have been associated with peer rejection, including early conduct problems, later adolescent disorders, school truancy, suspension, and leaving school early (Coie, Lochman, Terry, & Hyman, 1992; Miller-Johnson, Coie, Maumary-Geremaud, Bierman, & Conduct Problems Research Group, 2002; Woodward & Fergusson, 2000). Similarly, withdrawal from the peer group and peer victimization are associated with many maladaptive outcomes, including depression, loneliness, and anxiety (Hodges & Perry, 1999; Hodges, Boivin, Vitaro, & Bukowksi, 1999), as well as with externalizing behaviors, school avoidance, and academic failure (Hanish & Guerra, 2002; Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1996). Although many of these associations are assessed via cross-sectional designs, preliminary evidence indicates that peer difficulties predict changes in symptomology and that these effects can linger into adulthood (Kochenderfer-Ladd & Wardrop, 2001; Olweus, 1992). The investigation of factors contributing to success or failure within the peer milieu have long been considered important, though such studies have been challenged to establish a clear direction of effects (Rubin, et al., 2006).

Although early work on the predictors of peer relationships focused on how children were processing social cues and generating responses to specific peer behaviors (c.f. Dodge, 1986), more recent work has focused on the emotion-relevant behavior children exhibit in peer environments and how it may predict their response to the behavior of others. Much of this work has focused on how children manage these emotion-relevant behaviors, with the assumption that failure to regulate emotions is a proximal cause of peer relationship difficulties (Denham et al., 2003; Eisenberg, et al., 1993; Halberstadt, Denham, & Dunsmore, 2001). From a developmental perspective, success or failure at important developmental tasks, such as the acquisition of emotion regulation skills during toddlerhood and preschool, likely plays some role in the trajectory of more serious problem behavior as children enter peer and school contexts (Keane & Calkins, 2004; Hill, Degnan, Calkins, & Keane, 2006). Moreover, from this standpoint, early childhood behavior problems are considered a risk factor for later antisocial behavior and suggest that the mechanism(s) responsible for ongoing behavioral difficulties are to be found in the interactions between very early child functioning, particularly with respect to the regulation of arousal, and the contexts in which the development of regulation is occurring: namely family and peer relationships.

Considerable work has examined the development of emotion regulation, from both normative and atypical perspectives (Calkins & Howse, 2004; Blandon, Calkins, Keane, & O’Brien, 2008; Keenan, 2000). Emotion regulation is defined as those behaviors, whether automatic or effortful, conscious or unconscious, elicited during an affectively arousing situation (Buss & Goldsmith, 1998; Calkins & Hill, 2007). Emotion regulation helps individuals modulate their arousal and facilitates positive social interaction and effective social problem solving (Eisenberg, et al., 1995, 1996; Howse, et al., 2003). Early behavioral difficulties, those characterized by high negativity and oppositional behavior challenge the child to acquire appropriate emotion regulation skills (Calkins & Dedmon, 2000)

The ability to regulate one’s emotions is a critical achievement attained during childhood, with considerable support and feedback from caregivers (Calkins & Hill, 2007; Thompson & Meyer, 2007) and has implications for many dimensions of later development, including behavioral adjustment, social relationships, and school achievement (Degnan, et al., 2008; Calkins & Howse, 2004). By school age, the pattern of emotion regulation may be entrenched and difficult to alter. For example, among older children, inhibition and suppression of negative emotion has been associated with greater internalizing problems (Suveg & Zeman, 2004), whereas undercontrolled negative emotion has been linked to greater externalizing problems (Eisenberg, et al., 2001).

Although there has been less focus on peers and the development of emotion regulation, it is clear that by the time children enter school, peers, like parents, help with the development of self-regulatory skills. Peers serve as sources of emotional support during times of stress (Hartup, 1996) but also provide feedback about the appropriateness of emotional displays. Anger expression, bossiness, aggression, and impulsivity are all negatively related to peer status (Eisenberg, Fabes, Bernzweig, & Karbon, 1993; Keane & Calkins, 2004); rejected children are also more effusive in their displays of emotion (i.e. happiness) to positive events (Hubbard, 2001). Taken together, these studies suggest that both positive and negative high-intensity emotional behavior play a role in determining concurrent peer status. The peer group may also attempt to socialize children’s emotion regulation through specific negative treatment, such as peer victimization or exclusion (Salisch, 2001).

Given that emotion regulation patterns are established early and can lead to a range of difficulties, examining its emergence and the way it influences other skills and abilities is especially important. Entrance to school, therefore, marks a significant and appropriate period to study the relation between emotion regulation and social competence, as these early relationships and concomitant peer status may be difficult to alter (Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1996). However, it is important to consider how emotion regulation becomes an element of peer relationships, how it influences behavior directed towards peers that becomes a part of the child’s social repertoire and influences social status, reputation, and peer success. Most of the research examining the role of emotion regulation and social status, for example, has focused on direct relations or on indices of behavior problems as a proxy for peer relationships.

Early work on the relations between problem behavior and peer relationships, however, provides insight into the mechanisms through which emotion regulation becomes a predictor of peer success during the transition to school. For example, Ladd and colleagues (Ladd, Kochenderfer, & Coleman, 1996) found that children who transitioned to school with a familiar peer had better academic and social adjustment than chidden who did not. Ladd further demonstrated that cooperative play on the playground predicted increases in peer acceptance across the preschool year (Ladd, Price, & Hart, 1988). Conversely, noncompliant behavior and arguing with peers were related to increases in peer rejection at both midyear and end of year assessments.

The predictive relations between early negative and poorly-regulated behavior and peer relations may be a function of several different behavioral processes. Young children may simply be engaging in the same behaviors in the classroom as they do at home (aggression, negativity, & oppositional behavior) and become disliked by peers for engaging in these behaviors toward classmates. Young children may engage in other sorts of behavior that elicit negative attention from the teacher (noncompliant or uncontrolled behavior) and the negative attention causes their peers to like them less. Children may also fail to engage in positive peer-directed behavior (e.g., sharing), which can lead to peer dislike (Keane & Calkins, 2004). A small number of studies have examined the specific behaviors exhibited by young children and success with peers. For example, in one study, preschoolers who engaged in prosocial behaviors and were adept at understanding emotional situations were well liked by their peers (Denham, McKinley, Couchoud, & Holt, 1990).

Given the salience of peer-directed behaviors for young children and children’s abilities to identify peers with better versus poorer social skills, which are a strong predictor of rejection and liking at a young age (Keane & Calkins, 2004), it is possible that the pathway from challenging toddler behavior and poor emotion regulation to compromised peer relationships in the early years of school is through social skills acquired during the transition from preschool to kindergarten. Children who can manage their negative and positive emotions may have more success at learning appropriate behaviors in the peer environment of the classroom and more likely to use them in subsequent social interactions. Successful use of these behaviors is noted by peers, who, in turn, develop preferences for some children over others, a process that initiates children’s social standing in the school environment as early as kindergarten.

There are clear challenges to identifying the direction of effects when studying relations among indices of emotional and social competency and peer relationships. However, it is clear from prior work that an attempt to understand these pathways and cascades must begin by assessing these constructs very early in development, prior to the time children have much exposure to peers. Moreover, it is necessary to measure early behaviors and skills across the period of early childhood in order to observe the bidirectional relations that are likely occurring. Finally, in order to understand the possible mechanisms by which early challenging behavior and emotion regulation affects peer relationships, it is important to sample the kinds of skills that are observable in preschool and kindergarten when children are first challenged to negotiate these relationships. These were the primary aims of the present study, a longitudinal investigation of the relations among early indices of emotional functioning, social competence, and peer relationships.

Research Aims

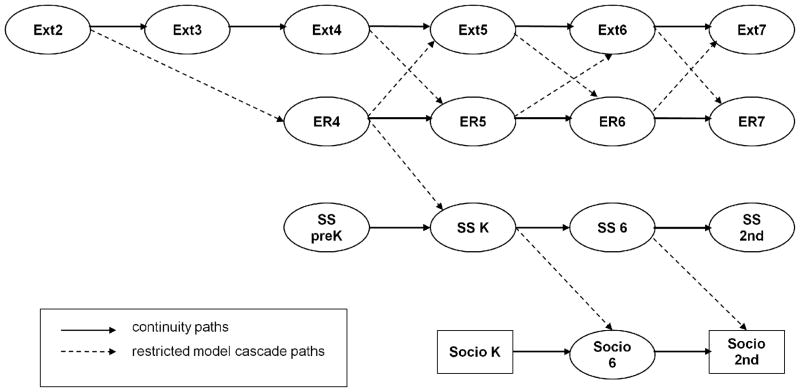

Figure 1 depicts a model that captures the influence of both early behavioral difficulties (externalizing problems) and emotion regulation on emerging social skills and peer acceptance in the early school years. This model focuses on the effects of child-driven processes and highlights the emerging emotion regulation skills that continue to influence and be influenced by a child’s level of behavior problems over the course of early childhood (Degnan et al., 2008; Hill et al., 2006). To investigate this model, we use longitudinal data from a study of children at different levels of risk for externalizing behavior problems. We measured externalizing behavior problems from ages 2 through 7, and emotion regulation, social skills, and peer relationships as emerging competencies at ages 4 and 5. Peer acceptance was measured during kindergarten and 2nd grade.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of hypothesized restricted cascade model. Numbers and grades denote year of data collection. preK = preschool assessment, K = kindergarten assessment, 2nd = 2nd grade assessment. Latent variables labeled 3 and 6 are placeholders to accommodate differential spacing of measurement. All models include within-time correlations (not shown) and paths from the prior model. Ext = externalizing; ER = emotion regulation; SS = social skills; Socio = sociometric ratings.

The first aim was to examine the stability of children’s emotional and social functioning from 2 to 7 years of age. We expected significant stability across the time points for all of the constructs, with externalizing behavior showing the highest levels of stability over time. Our second aim was to examine a restricted cascade model across early development focused on the key paths outlined in Figure 1. First, externalizing behavior and children’s emotion regulation were expected to show bidirectional effects over time. In addition, we expect children’s early externalizing behavior will have a significant effect on their later emotion regulation skills, which would then impact their social skills, and finally their peer acceptance in 2nd grade.

Due to the potential complex nature of multiple reciprocal processes linking emotional and social competence to peer acceptance across early childhood our final aim is exploratory, and examines a full model including all possible cross-lag (cascade) paths. Given the exploratory nature of this model, no specific hypotheses are proposed.

Method

Recruitment and Attrition

The current sample utilized data from three cohorts of children who are part of a larger ongoing longitudinal study. The goal for recruitment was to obtain a sample of children who were at risk for developing future externalizing behavior problems that was representative of the surrounding community in terms of race and socioeconomic status (SES). All cohorts were recruited through child day care centers, the County Health Department, and the local Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program. Potential participants for cohorts 1 and 2 were recruited at 2 years of age (cohort 1: 1994–1996 and cohort 2: 2000–2001) and screened using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL 2–3; Achenbach, 1992) completed by the mother in order to over-sample for externalizing behavior problems. Children were identified as being at risk for future externalizing behaviors if they received an externalizing T score of 60 or above. Efforts were made to obtain approximately equal numbers of males and females. A total of 307 children were selected. Cohort 3 was initially recruited when infants were 6 months of age (in 1998) for their level of frustration based on laboratory observation and parent report and followed through the toddler period (see Calkins, Dedmon, Gill, Lomax, & Johnson, 2002 for more information). From cohort 3, children whose mothers’ completed the CBCL at 2 years of age were included in the current study (n = 140). Of the entire sample (N = 447), 37% of the children were identified as being at risk for future externalizing problems. There were no significant demographic differences between cohorts with regard to gender, χ2 (2, N = 447) = .63, p = .73, race, χ2 (2, N = 447) = 1.13, p = .57, or 2-year SES, F (2, 444) = .53, p = .59. Cohort 3 had a significantly lower average 2-year externalizing T score (M = 50.36) compared to cohorts 1 and 2 (M = 54.49), t (445) = − 4.32, p < .01.

Of the 447 original screened participants, six were dropped because they did not participate in any 2 year data collection. At 4 years of age, 399 families participated. Families lost to attrition included those who could not be located, moved out of the area, declined participation, and did not respond to phone and letter requests to participate. There were no significant differences between families who did and did not participate in terms of gender, χ2 (1, N = 447) = 3.27, p = .07, race, χ2 (1, N = 447) = .70, p = .40, 2-year SES, t (424) = .81, p = .42, or 2-year externalizing T score, t (445) = -.36, p = .72. At 5-years of age 365 families participated including four that did not participate in the 4-year assessment. Again, there were no significant differences between families who did and did not participate in terms of gender, χ2 (1, N = 447) = .76, p = .38, race, χ2 (1, N = 447) = .17, p = .68, 2-year SES, t (424) = 1.93, p = .06), and 2-year externalizing T score (t (445) = −1.73, p = .09). At 7-years of age 350 families participated including 19 that did not participate in the 5-year assessment. Again, there were no significant differences between families who did and did not participate in terms of gender, χ2 (1, N = 447) = 2.12, p = .15, race, χ2 (3, N = 447) = .60, p = .90, and 2-year externalizing T score (t (445) = −1.30, p = .19). Families with lower 2-year SES, t (432) = 2.61, p > .01) were less likely to continue participation at the 7-year assessment.

Participants

The current sample included 440 children (212 male, 228 female). Children were, on average, 31 months (SD = 3.67 months), 54 months (SD = 3.74 months), 68 months (SD = 3.25 months), and 92 months (SD = 4.31 months) at the 2, 4, 5, and 7 year assessments respectively. At the 2-year assessment, 67% were European American, 27% were African American, 4% were biracial, and 2% were Hispanic. At the 2-year assessment, the children were primarily from intact families (80%; single = 16%, divorced/separated = 4%) and families were economically diverse based on Hollingshead SES scores (M = 39.54, SD = 11.15; 1975). The 4-, 5-, and 7-year SES scores were on average 42.43 (SD = 10.64), 43.00 (SD = 10.44), and 44.78 (SD = 11.77), respectively. Hollingshead scores that range from 40 to 54 reflect minor professional and technical occupations considered to be representative of middle class.

Procedures

Children and their mothers participated in an ongoing longitudinal study when the children were 2, 4, 5, and 7 years of age. During the laboratory assessments, children and their mothers engaged in a series of tasks designed to elicit emotional and behavioral responding and mother-child interaction. At each laboratory assessment, mothers completed questionnaires assessing family demographics, their own functioning, and their child’s behavior. School assessments were also conducted when children were in preschool, kindergarten, and 2nd grade. Current analyses included maternal-reported questionnaire data from the laboratory assessments, teacher-reported questionnaire, and sociometric data from the school assessments.

Preschool Assessment

Consent from the families was obtained to complete an assessment in the child’s preschool classroom. Preschool teachers completed questionnaires that measured children’s behavior problems, emotionality and regulation, child classroom social behavior, and children’s social skills.

Kindergarten and 2nd Grade Assessment

Consent from the families was obtained to complete an assessment in the child’s kindergarten classroom. This assessment did not take place until the children had at least 8 weeks in the classroom to become acclimated to their peers. Classroom sociometric ratings were conducted by trained graduate and undergraduate students who individually interviewed each child. The sociometric procedures used were a modified version of the Coie, Dodge, and Coppotelli (1982) procedure. Instead of asking children to nominate three peers they “liked most” and “liked least,” children were asked to give unlimited nominations for each category. This method allows for more reliable results and a reduction in measurement error (Terry, 2000). Furthermore, this increased precision can be achieved with fewer classmates than are needed for the limited-choice nominations (Terry, 2000). The mean rate of participation across classrooms was 84% (range = 68% – 94%; number of reporters = 8 – 22), which is well within the acceptable range (Keane & Calkins, 2004). Sociometric data were collected in 158 classrooms for the current sample. The average number of students in a class was 20 (Range = 10 – 27). Cross-gender nominations were permitted to increase the stability of measurement for the nominations to determine peer status. To ensure children had a good understanding of the questions, they were asked to go through several sample questions until they understood the task, and pictures of all of the participating children were provided as visual prompts. Interviewers were trained to provide further information and more examples if the child did not seem to grasp the questions. Teachers also completed questionnaires to assess the target child’s social, emotional, and behavioral functioning in the school setting.

Measures

Externalizing Behavior Problems

The Child Behavior Checklist was used to assess both externalizing and internalizing behaviors (CBCL; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983). Mothers completed the CBCL for 2–3 year olds when the children were 2 years of age (Achenbach, 1992) and the CBCL for 4–18 year olds when the children were 4, 5, and 7 years of age (Achenbach, 1991). These scales have been found to be a reliable index of externalizing and internalizing behavior problems across childhood (Achenbach, Edelbrock, & Howell, 1987; Achenbach, 1992). The measures for the current analysis included, at 2 years of age, the minor subscales of aggression and destructive behavior. At 4, 5, and 7 years of age, the minor subscales of aggression and delinquency were utilized.

Teachers completed the elementary school version of the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992). The BASC is a widely used behavior checklist that taps emotional and behavioral domains of children’s functioning. The teacher elementary school version for children ages 2 1/2–5 contains 109 items, whereas the version for children ages 6–11 contains 148 items. Because some of the children in our sample turned 6 during the kindergarten year, it was necessary to give them the ages 6–11 version of the BASC. Each item on the BASC is rated on a four-point scale with respect to the frequency of occurrence (never, sometimes, often, and almost always). The measure yields scores on broad internalizing, externalizing, and behavior symptom domains as well as nine specific content scales. The BASC has well-established internal consistency, reliability, and validity (Doyle, Ostrander, Skare, Crosby, & August, 1997; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992). For the purpose of the present study, the raw specific content scales of aggression and hyperactivity were included.

Emotion Regulation

Mothers and teachers completed the Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC; Shields & Cicchetti, 1997, 2001), which assesses the reporter’s perception of the child’s emotionality and regulation. This measure includes 23 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale indicating how frequently the behaviors occur (1 = almost always to 4 = never). The emotion regulation subscale includes 8 items that assess aspects of emotion understanding and empathy and contains items such as “displays appropriate negative affect in response to hostile, aggressive or intrusive play” and “is a cheerful child.” The negativity subscale includes 15 items that assess aspects such as angry reactivity, emotional intensity, and dysregulated positive emotions and contains items such as exhibits wide mood swings” and “is easily frustrated”. Validity has been established using correlations with observers’ ratings of children’s regulatory abilities and the proportion of expressed positive and negative affect (Shields & Cicchetti, 1997).

Social Skills

The Social Skills Rating System was completed by the child’s teacher at each school assessment. Preschool teachers completed the preschool version that contains 30-items to assess social behavior. Kindergarten and 2nd grade teachers completed the elementary school version of the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS; Gresham & Elliot, 1990) designed to assess children in kindergarten through 6th grade. The elementary school version is a 57-item behavior rating system that measures children’s social behavior in the classroom including social skills, academic competence, and problem behavior. On each version, teachers report on the frequency in which children engage in a variety of social behaviors (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = very often) and how important each of these behaviors is for the child’s development (0 = not important, 1 = important, 2 = critical). The SSRS has well-established internal consistency (α’s range from .78 to .95), reliability, and criterion-related validity with the CBCL (−.64). The current study utilized the raw scores of cooperation, assertion, and self-control. Higher scores indicate better social skills.

Sociometric nominations

Children’s likability was assessed based on peer sociometric ratings during kindergarten and 2nd grade. A social preference score was obtained from the sociometric procedures. The total number of nominations for “like most” and “like least” were standardized to obtain two separate z scores, which were subsequently subtracted to compose a social preference score (z “like most” − z “like least” = social preference; Coie et al., 1982). Social preference was then standardized within classrooms after computing the difference score. Lower scores represented less likeability whereas higher scores represented greater likeability. This is a widely used technique for assessing a child’s overall likeability or peer acceptance within the classroom (Jiang & Cillessen, 2005).

Analysis Plan

Longitudinal Measurement Models

Several longitudinal factors were fit in an attempt to adequately account for the covariances among the observed scores over time because there were several indicators of the major constructs. For example, externalizing behaviors were measured by parent ratings of aggression and destructive and teacher reports of hyperactivity and aggression at ages 4, 5, and 7. As recommended by Kline (2005), indicators of latent variables were rescaled so that the difference in variance between each of the indicators was not more than 10, which facilitates model convergence (maternal-reported aggressive behavior .2 and destructive/delinquency 2; teacher reported hyperactivity and destructive behavior .2; maternal and teacher reported emotion regulation and negativity 5). First, we fitted two longitudinal factor models that differed in the number and types of factors. Once the factor structure was determined, we examined the invariance of the factor loadings (Meredith, 1964a, 1964b, 1993) across age.

In the first model, trait model, there were externalizing factors at ages 2, 4, 5, and 7 as well as emotion regulation and social skills factors at ages 4, 5, and 7. All common factors were allowed to covary and unique covariances between the same measurement instruments across time were estimated (e.g., mother rated aggression at ages 2, 4, 5, & 7). In the second model, trait plus informant model, we examined the need for four informant factors as the data were collected from mother and teacher reports. Thus, the data represent a modified longitudinal multitrait-multimethod (Campbell & Fiske, 1959; Widaman, 1985) design where multiple traits were crossed with multiple methods across time (Grimm, Pianta, & Konold, 2009). Informant factors may be necessary because behavior rating scales often show considerable informant variance (e.g., Konold & Pianta, 2007). The four informant factors were a global mother factor and three teacher factors–one at ages 4, 5, and 7 when teacher reports were available. Teacher factors were indicated by all of the ratings made by the child’s teacher at that age. The mother factor was indicated by all of the ratings made by the child’s mother, regardless of age. Informant factors were assumed to be uncorrelated with trait factors for identification purposes. Once the factor structure was determined, we examined longitudinal measurement invariance by constraining the factor loadings of the same observed score to be the invariant across age. This was done for trait and informant factors.

Autoregressive Cross-Lag Models

Once the factor structure was determined, we examined the longitudinal associations by fitting a series of models for the trait factors. In these models, sociometric nomination data (at ages 5 & 7) were also included. The first model (continuity model) allowed for all autoregressive paths, where each factor was predicted by itself at the previous time. The second model, a restricted model based on Burt et al. (2008), allowed for all autoregressive paths, where each factor was predicted by itself at the previous time, and a specific series of cross-lag paths (i.e., cascade effects). The cross-lag paths included longitudinal associations between externalizing and emotion regulation from 2 to 7 years of age, as well as emotion regulation at age 4 to social skills at age 5, and social skills at age 5 to sociometric nominations at age 7. The third (full model), more exploratory autoregressive cross-lag model, included all possible cross-lag effects between externalizing, emotion regulation, social skills, and sociometric nominations. In both models, autoregressive coefficients were forced to be equal across time and the differential spacing of measurements was accommodated with the addition of latent variable place holders (see McArdle, 2001). All models were fit using Mplus v. 5.0 and Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation was used to handle incomplete data.

Results

Longitudinal Measurement Model

Fit statistics and parameter estimates from the trait model (χ2(476)=2351, RMSEA=.094, CFI=.758, TLI=.698) suggested the model was unable to adequately capture to covariation structure of the data as several correlations among the common factors were greater than |1|. The fit of the trait plus informant model (χ2(435)=847, RMSEA=.046, CFI=.947, TLI=.927) was statistically better than the fit of the trait model (Δχ2=1504, Δdf=41) and the global fit indices were in the adequate to good range. Behavior ratings tended to show a considerable amount of informant variance, thus it was important to account for this variability. However, some convergence issues remained. These issues were with unique covariances, which were unstable because unique variances tended to be small. Measurement invariance was then examined with the trait plus informant model. The invariance model fit statistically worse (Δχ2=97, Δdf=31, p<.01); however global fit indices were still good (CFI=.938, TLI=.921, RMSEA=.048) indicating the invariance model was an adequate representation of the data. Factor correlations from the measurement model are included in the appendix.

Appendix.

Factor Correlations from the Measurement Model

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ext2 | ----- | |||||||||

| 2. Ext4 | .55*** | ----- | ||||||||

| 3. Ext5 | .45*** | .42*** | ----- | |||||||

| 4. Ext7 | .09 | .43*** | .38*** | ----- | ||||||

| 5. ER4 | −.16* | −.20* | −.18* | −.08 | ----- | |||||

| 6. ER5 | −.24** | −.13 | −.39*** | −.01 | .55*** | ----- | ||||

| 7. ER7 | −.04 | −.08 | −.15 | −.30** | .32** | .45*** | ----- | |||

| 8. SS preK | −.08 | −.09 | −.11 | −.04 | .83*** | .56*** | .21* | ----- | ||

| 9. SS K | −.33*** | −.16* | −.24** | −.08 | .41*** | .92*** | .44*** | .37*** | ----- | |

| 10. SS 2nd | −.13 | −.16* | −.17* | −.20* | .27** | .42*** | .79*** | .27** | .42*** | ----- |

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Numbers denote year of data collection. preK = preschool assessment, K = kindergarten assessment, 2nd = 2nd grade assessment. Ext = externalizing; ER = emotion regulation; SS = social skills.

Longitudinal Autoregressive Models

The first longitudinal model, which assessed the stability in constructs over time, fit the data well (χ2(565)=1155, CFI=.925, TLI=.911, RMSEA=.048). All autoregressive paths were positive and significantly different from zero suggesting that the child’s behavior (e.g., externalizing) at any age was related to his/her behavior at the previous occasion.

Longitudinal Cross-Lag Models

The first longitudinal cross-lag model, based on Burt et al. (2008) fit the data well (χ2(562)=1149, CFI=.925, TLI=.911, RMSEA=.048). The restricted model fit statistically marginally better than the autoregressive model (Δχ2=6.61, Δdf=3, p < .10). All autoregressive paths were positive and significantly different from zero suggesting that the child’s behavior (e.g., externalizing) at any age was related to his/her behavior at the previous occasion. In terms of cross-lag paths, only the path from social skills to sociometric nominations was significantly different from zero. The cross-lag coefficient was positive suggesting that a child’s social skills at a given occasion were positively related to the child’s subsequent sociometric nominations controlling for previous levels of sociometric nomination. Thus, children with higher levels of social skills showed greater increases in subsequent popularity. Within-time correlations between constructs, after taking into account their autoregressive and cross-lag effects, ranged from .03 to .93. Notably, emotion regulation and social skills were strongly positively related (r = .85 to .93); externalizing behaviors and social skills were negatively related (r = −.07 to −.18), and emotion regulation was negatively correlated with externalizing behaviors (r = −.23 to −.36). Sociometric nominations were not strongly correlated with emotion regulation (r = .03 to .11), externalizing behavior (r = −.04 to −.05), or social skills (r = −.08 to −.13).

The second longitudinal cross-lag model, which was a complete exploratory cross-lag model, also fit the data well (χ2(554)=1123, CFI=.928, TLI=.913, RMSEA=.048), and fit statistically better than the restricted cross-lag model (Δχ2=25.40, Δdf=8, p < .01). This model led to a different representation of cascade effects. In this model, autoregressive coefficients for externalizing behaviors and sociometric nominations were significantly different from zero. In terms of cascade effects, social skills was found to have an effect on subsequent levels of externalizing behaviors controlling for previous levels of externalizing behavior, emotion regulation, and sociometric nominations when available. The coefficient was negative suggesting that children with greater social skills showed greater decreases in externalizing behavior at the next occasion. In addition, the cross-lag paths from emotion regulation to externalizing behavior were significant. The coefficient was negative suggesting that higher levels of emotion regulation showed greater decreases in subsequent levels of externalizing behavior problems, controlling for earlier levels of externalizing behavior. No other cross-lag effects were significantly different from zero.

Discussion

The present study examined a cascade model of children’s early emotional and social competence and children’s peer acceptance. A cascade analysis allows for an understanding of how complex developmental phenomena emerge across early childhood as well as being able to identify bidirectional influences over time among these phenomena. Research that simultaneously examines multiple domains of behavior over time fits within a developmental psychopathology perspective which promotes a view of development in which multiple factors, or levels of a given factor, are considered in context of one another rather than in isolation (Cicchetti & Dawson, 2002; Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1996). The present investigation examined a series of longitudinal structural equation models utilizing a multimethod multitrait approach that specifically controlled for shared rater variance, which is a common limitation when informant’s ratings are used to assess children’s behavioral functioning (Konold & Pianta, 2007). Given that several studies have found associations among early emotional and social functioning such as disruptive behavior and children’s regulatory abilities with children’s classroom experiences, we were particularly interested in the indirect effects of externalizing behavior and emotion regulation on later social skills and children’s peer acceptance. Specifically, we examined cascade effects from 2 year externalizing behavior to 4 year emotion regulation, which was then hypothesized to predict kindergarten social skills to levels of children’s peer acceptance in 2nd grade. Overall, the results provide some evidence for the role of cascade effects in early development although the cascade effects found were not always consistent with our specific hypothesis. These results underscore the importance of utilizing complex models for identifying bidirectional and cross-domain effects across early childhood.

The first aim was to examine the stability of children’s externalizing behavior, emotion regulation, social skills, and peer acceptance across early childhood. The models tested controlled for shared rater variance which is a common problem in longitudinal studies that rely on parent and teacher ratings of children’s behavioral functioning, thereby providing a more stringent test of stability among each construct over time. The continuity model, that tested the autoregressive paths among each construct, indicated that that there was stability in all of behaviors assessed (externalizing behavior, emotion regulation, social skills, & peer acceptance) across early childhood. Specifically, a child’s behavior at the earlier assessment was predictive of their behavior at the later assessment.

A different picture emerged, however, when the cascade paths (i.e., cross-lag paths) were included in the model. The full exploratory model, that included all cascade paths, indicated that only children’s externalizing behavior from 2 to 7 years of age and peer acceptance from kindergarten to 2nd grade exhibited stability. Suggesting that children’s ability to regulate their emotions and the social skills they utilize in the classroom are not stable across the period examined. Previous research with the same sample, found that children’s emotion regulation generally increases over time from 4 to 7 years of age (Blandon et al. 2008). Developments in brain regions associated with regulatory functioning, such as the maturation of the prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulated cortex are potential mechanisms underlying these improvements (Ochsner, Bunge, Gross, & Gabrieli, 2002; Ochsner & Gross, 2005). During this time children develop the capacity to utilize more complex strategies, such as reappraising negative events or planning to avoid distressing or difficult situations (Larsen & Prizmic, 2004); it may be the case that while they are using more strategies that they may not always prove effective, which may influence their stability over time.

Another potential explanation that emerges from a transactional perspective, and may be particularly relevant for the social skills that children are able to utilize in the classroom, is that the environmental changes that are occurring across early childhood may impact the development of children’s competencies. Across this period there are changes in classroom management practices that may account for differences in children’s ability to behave appropriately within the classroom, including increasing expectations for socially appropriate behavior and increasingly structured events (La Paro, Rimm-Kaufman, & Pianta, 2006). Given that children also have different teachers every year, and that classroom management strategies are likely to differ across different classroom, it is not necessarily surprising that children’s social skills in the classroom across early childhood are not stable.

The second aim was to examine whether the longitudinal cascade paths between externalizing behavior and emotion regulation and whether early externalizing behavior indirectly influences later peer acceptance through developments in earlier emotion regulation and social skills (Figure 1). The picture that emerged was somewhat different based on the restricted model that only tested these specific cascade paths (Figure 1) and the full model that examined all possible cascade paths (Table 2). Contrary to our expectations, the results from the restricted model indicated that there was not a bidirectional relation over time between children’s externalizing behavior and their emotion regulation. There was, however, some evidence of cascade effects based on the full model indicating that children’s ability to regulate their emotions influenced their later levels of externalizing behavior. Specifically, it appears that children with higher levels of emotion regulation evidence decreases in their subsequent externalizing behavior. This is consistent with a considerable body of research that has found that when children are unable to manage or modulate their emotions, particularly in frustrating and difficult situations, that they are at risk for increased levels of aggressive and disruptive behavior problems, difficulties with peers, and later psychopathology (Calkins, Gill, Johnson, & Smith, 1999; Eisenberg et al., 2001; Keenan, 2000; Shipman, Schneider, & Brown, 2004).

Table 2.

Longitudinal SEM Models Tested in the Cascade Analysis

| 2yr to 3yr | 3yr to 4yr | 4yr to 5yr | 5yr to 6yr | 6yr to 7yr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (Continuity Model autoregressive paths included in all subsequent model) | ||||

| Ext 2yr → Ext 3yr | Ext 3yr → Ext 4yr | Ext 4yr → Ext 5yr | Ext 5yr → Ext 6yr | Ext 5yr → Ext 7yr |

| ER 4yr → ER 5yr | ER 5yr → ER 6yr | ER 5yr → ER 7yr | ||

| SS preK → SS K | SS K → SS 6yr | SS 6yr → SS 2nd | ||

| Socio K → Socio 6 | Socio 6yr → Socio 2nd | |||

| Model 2 (Restricted Model included in subsequent model) | ||||

| Ext 2yr → ER 4yr | ER 4yr → Ext 5yr | ER 5yr → Ext 6yr | ER 5yr → Ext 7yr | |

| Ext 4yr → ER 5yr | Ext 5yr → ER 6yr | Ext 5yr → ER 7yr | ||

| ER 4yr → SS K | SS K → Socio 6yr | SS 6yr → Socio 2nd | ||

| Model 3 (Full Exploratory Model) | ||||

| Ext 2 yr → SS preK | Ext 4yr → SS K | Ext 5yr → SS 6yr | Ext 6yr → SS 7yr | |

| Ext 4yr → Socio K | Ext 5yr → Socio 6yr | Ext 6yr → Socio 2nd | ||

| ER 4yr → Socio K | ER 5yr → SS 6yr | ER 6yr → SS 2nd | ||

| SS preK → ER 5yr | ER 5yr → Socio 6yr | ER 6yr → Socio 2nd | ||

| SS preK → Socio K | SS K → ER 6yr | SS 6yr → ER 7yr | ||

| SS preK → Ext 5yr | SS K → Ext 6yr | SS 6yr → Ext 7yr | ||

| ER 4yr → Socio K | Socio K → SS 6yr | Socio 6yr → SS 2nd | ||

| SS preK → Ext 5yr | Socio K → ER 6yr | Socio 6yr → ER 7yr | ||

| Socio K → Ext 6yr | Socio 6yr → Ext 7yr | |||

Note. Numbers denote year of data collection. Year 3 and 6 are latent variable placeholders to accommodate differential spacing of measurement. preK = preschool assessment, K = kindergarten assessment, 2nd = 2nd grade assessment. Ext = externalizing; ER = emotion regulation; SS = social skills; Socio = sociometric ratings.

Other avenues of research point toward reciprocal interactions between early externalizing behavior problems and children’s early emotion regulation skills across early childhood (Calkins & Keane, 2009). For instance, when children exhibit early high levels of externalizing behavior problems they may be more limited in their opportunities in which they are exposed to situations that may offer opportunities to learn strategies to manage their emotions. This may be, in part, due to parents’ reluctance to take difficult children to certain places or limit their peer interactions. It is also important to note that children’s emotion regulation is just one component process of a set of self-regulatory behaviors that develop during childhood. Indeed, self-regulation has been identified as a set of processes, including physiological, attentional, emotional, and cognitive control (Calkins, 2009; Calkins & Keane, 2009). These self-regulatory processes are hypothesized to be hierarchically organized and linked over time such that earlier regulatory developments such as children’s capacity for physiological regulation and attentional control support the development of later abilities (Calkins 2009). In the current investigation we focused specifically on children’s capacity for regulating their emotions which could account for lack of bidirectional effects. Given that children’s physiological and attentional self-regulatory processes are theorized to emerge earlier in development and they may be more likely to exhibit bidirectional relations with children’s externalizing behavior particularly during the toddler and preschool years.

In addition to longitudinal associations among children’s externalizing behavior problems and emotion regulation, the other cascade paths tested in the restricted model included children’s emotion regulation at age 4, predicting children’s social skills in the classroom during kindergarten, which was expected to predict classroom peers reports of child acceptance in 2nd grade. Contrary to our expectations, only the cascade path from children’s social skills within the classroom to sociometric nominations was significant, suggesting children with higher levels of social skills in the classroom show greater increases in subsequent popularity. Cascade effects, therefore, were evident but not until children entered school. It appears that the domain of social competence that is most important for children’s peer acceptance in school is how they are able to behave in school. There is some research to suggest that when children are able to engage in more prosocial interactions with peers, such as sharing, they have higher levels of peer acceptance (Erhardt & Hinshaw, 1994; Ladd, Price, & Hart, 1988).

The final goal was more exploratory, given that we expected there to be complex interactions among the multiple developmental phenomena from 2–7 years of age. We examined all possible cascade paths to fully explore potential cross-domain and reciprocal associations that within the cascade model context may be relevant for understanding children’s early social and emotional development. In terms of cascade effects, social skills was found to have an effect on subsequent levels of externalizing behaviors controlling for previous levels of externalizing behavior, emotion regulation, and sociometric nominations when available. Specifically, children with greater social skills in the classroom showed greater decreases in externalizing behavior at the next occasion. Children’s social skills, such as the ability to cooperate and exhibit self-control in the classroom, may reflect some aspect of children’s ability for behavioral regulation. Indeed, children’s ability to comply with adult directives and mange impulsive responses are key aspects of children’s behavioral regulation (Kopp, 1982; Kuczynski & Kochanksa, 1995), which are thought to be important for their transition into the school environment. It is also possible, that aspects of the school environment may support children’s capacity to regulate their behavior. Indeed, the increased structure that occurs from preschool through second grade may facilitate the development of children’s behavioral regulation which then may reduce their disruptive behavior overall, not just in the classroom. In addition, the peer group may also attempt to socialize children’s emotion regulation through specific types of negative treatment, such as peer victimization or exclusion (Salisch, 2001), that over the course of the school year influences children’s level of disruptive behaviors. No other significant cross-lag effects were found.

The study has some limitations that must be noted. First, the sample was overselected for externalizing behavior problems and thus may not be representative of community samples. Although there was still a normal range of behavior problems exhibited within the sample. It may actually be the case that a more extreme group approach may be more conducive to testing the model that externalizing behavior is a leading indicator in a cascade of effects across early development that influence later peer acceptance. Second, it has been proposed that the strongest argument for cascade models can be established when the study is longitudinal, there are at least three assessment points, and each construct is measured at each time point (Masten et al., 2005). In the current study, emotion regulation was not assessed at age 2 which limits some of the conclusions that can be made and given the current results, may be the key factor in understanding the cascade of emotional and social development across early childhood.

This study extends the literature on the role that emotional and social competence plays in early peer relationships in a number of directions. First, although there are a number of studies that address the predictors of peer acceptance, few studies have explored multiple domains of children’s early social and emotional competence across early childhood, utilizing a cascade model that accounts for shared rater variance, within-time correlations and continuity within constructs over the period examined. This research clearly indicates that understanding the reciprocal relations of multiple developmental phenomena over time is necessary for developing a more clear understanding of the pathways to both typical and atypical social outcomes. Further research needs to address how these developmental processes interact across early childhood with a focus on the role of both child and contextual factors. This will allow for developing a more precise understanding of the cascade of effects over time.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for All Study Variables

| Measures | n | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-year Measures | ||||

| Aggressive behavior (CBCL) | 439 | 10.15 | 5.89 | .00–30.00 |

| Destructive behavior (CBCL) | 439 | 5.18 | 3.28 | .00–16.00 |

| 4-year Measures | ||||

| Aggressive behavior (CBCL) | 375 | 8.86 | 5.82 | .00–28.00 |

| Delinquent behavior (CBCL) | 375 | 1.57 | 1.48 | .00–8.00 |

| Aggressive behavior (BASC) | 234 | 6.21 | 6.02 | .00–30.00 |

| Hyperactivity (BASC) | 235 | 6.61 | 5.22 | .00–25.00 |

| Regulation subscale (ERC–Parent) | 376 | 3.31 | .32 | 2.13–4.00 |

| Negativity subscale (ERC–Parent) | 376 | 1.89 | .36 | 1.13–3.07 |

| Regulation subscale (ERC–Teacher) | 311 | 3.19 | .47 | 1.50–4.00 |

| Negativity subscale (ERC–Teacher) | 311 | 1.68 | .49 | 1.00–3.07 |

| Cooperation (SSRS) | 312 | 14.58 | 3.71 | 4.00–20.00 |

| Assertion (SSRS) | 311 | 13.01 | 3.78 | 2.00–20.00 |

| Self-Control (SSRS) | 312 | 13.71 | 4.07 | 3.00–20.00 |

| 5-year Measures | ||||

| Aggressive behavior (CBCL) | 341 | 8.64 | 6.54 | .00–33.00 |

| Delinquent behavior (CBCL) | 341 | 1.57 | 1.34 | .00–7.00 |

| Aggressive behavior (BASC) | 258 | 5.23 | 5.38 | .00–30.00 |

| Hyperactivity (BASC) | 259 | 7.08 | 6.17 | .00–30.00 |

| Regulation subscale (ERC–Parent) | 345 | 3.31 | .32 | 2.38–4.00 |

| Negativity subscale (ERC–Parent) | 345 | 1.92 | .38 | 1.13–3.20 |

| Regulation subscale (ERC–Teacher) | 224 | 3.19 | .43 | 1.75–4.00 |

| Negativity subscale (ERC–Teacher) | 223 | 1.61 | .48 | 1.00–3.33 |

| Cooperation (SSRS) | 265 | 15.34 | 4.17 | .00–20.00 |

| Assertion (SSRS) | 266 | 12.89 | 3.63 | .00–20.00 |

| Self-Control (SSRS) | 267 | 14.45 | 3.90 | .00–20.00 |

| Sociometric Ratings | 250 | −.05 | .96 | −2.48–2.16 |

| 7-year Measures | ||||

| Aggressive behavior (CBCL) | 328 | 6.37 | 5.33 | .00–29.00 |

| Delinquent behavior (CBCL) | 328 | 1.24 | 1.43 | .00–7.00 |

| Aggressive behavior (BASC) | 278 | 5.49 | 6.80 | .00–34.00 |

| Hyperactivity (BASC) | 278 | 8.87 | 7.90 | .00–34.00 |

| Regulation subscale (ERC–Parent) | 326 | 3.40 | .34 | 2.25–4.00 |

| Negativity subscale (ERC–Parent) | 326 | 1.72 | .39 | 1.00–3.07 |

| Regulation subscale (ERC–Teacher) | 271 | 3.12 | .47 | 1.75–4.00 |

| Negativity subscale (ERC–Teacher) | 271 | 1.63 | .51 | 1.00–3.67 |

| Cooperation (SSRS) | 274 | 14.95 | 4.42 | 3.00–20.00 |

| Assertion (SSRS) | 274 | 12.43 | 3.74 | 2.00–20.00 |

| Self-Control (SSRS) | 273 | 14.22 | 4.05 | 3.00–20.00 |

| Sociometric Ratings | 259 | .09 | .97 | −2.30–2.11 |

Note. Descriptive statistics are reported for the original variables prior to rescaling for SEM analysis.

Table 3.

Standardized Path Coefficients for All Cascade Paths from the Restricted and Full Exploratory Model.

| Cascade Path | Restricted Model | Full Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | |

| 2 year to 4 year Cascade Paths | ||||

| Ext 2yr → ER 4yr | .039 | .067 | −.148 | .099 |

| Ext 2yr → SS preK | −.130† | .068 | ||

| 4year to 5 year Cascade Paths | ||||

| Ext 4yr → ER 5yr | .088 | .054 | .027 | .056 |

| Ext 4yr → SS K | −.114† | .006 | ||

| Ext 4yr → Socio K | −.066 | .051 | ||

| ER 4yr → Ext 5yr | −.039 | .052 | .789* | .387 |

| ER 4yr → SS K | −.240 | .142 | .476 | .327 |

| ER 4yr → Socio K | .046 | .226 | ||

| SS preK → ER 5yr | .135 | .276 | ||

| SS preK → Socio K | .052 | .248 | ||

| SS preK → Ext 5yr | −.861* | .391 | ||

| 5 year to 6 year Cascade Paths | ||||

| Ext 5yr → ER 6yr | .085 | .052 | .026 | .055 |

| Ext 5yr → SS 6yr | −.107† | .062 | ||

| Ext 5yr → Socio 6yr | −.063 | .049 | ||

| ER 5yr → Ext 6yr | .040 | .052 | .780* | .373 |

| ER 5yr → SS 6yr | .456 | .300 | ||

| ER 5yr → Socio 6yr | .045 | .222 | ||

| SS K → ER 6yr | .119 | .248 | ||

| SS K → Socio 6yr | .116* | .057 | .045 | .222 |

| SS K → Ext 6yr | −.755* | .343 | ||

| Socio K → SS 6yr | .164† | .097 | ||

| Socio K → ER 6yr | .073 | .056 | ||

| Socio K → Ext 6yr | .037 | .028 | ||

| 6 year to 7 year Cascade Paths | ||||

| Ext 6yr → ER 7yr | .084 | .052 | .026 | .055 |

| Ext 6yr → SS 2nd | −.106† | .063 | ||

| Ext 6yr → Socio 2nd | −.063 | .049 | ||

| ER 6yr → Ext 7yr | .040 | .053 | .772* | .348 |

| ER 6yr → SS 2nd | .451 | .301 | ||

| ER 6yr → Socio 2nd | .045 | .219 | ||

| SS 6 → ER 7yr | .122 | .253 | ||

| SS 6 → Socio 2nd | .123* | .060 | .046 | .221 |

| SS 6 → Ext 7yr | −.776* | .348 | ||

| Socio 6 → SS 2nd | .165† | .097 | ||

| Socio 6 → ER 7yr | .074 | .055 | ||

| Socio 6 → Ext 7yr | .038 | .028 | ||

Note.

p < .10.

p < .05.

Numbers denote year of data collection, with 3 and 6 latent variable placeholders to accommodate differential spacing of measurement. preK = preschool assessment, K = kindergarten assessment, 2nd = 2nd grade assessment. Ext = externalizing; ER = emotion regulation; SS = social skills; Socio = sociometric ratings.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Behavioral Science Track Award for Rapid Transition (MH 55625) and an NIMH FIRST award (MH 55584) to Susan D. Calkins and by an NIMH grant (MH 58144) awarded to Susan D. Calkins, Susan P. Keane, and Marion O’Brien. We thank the parents and children who have repeatedly given their time and effort to participate in this research and are grateful to the entire RIGHT Track staff for their help collecting, entering, and coding data.

Contributor Information

Alysia Y. Blandon, The Pennsylvania State University

Susan D. Calkins, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Kevin J. Grimm, University of California, Davis

Susan P. Keane, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Marion O’Brien, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/2–3 and 1992 profile. Burlington, VT: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T, Edelbrock C, Howell C. Empirically based assessment of the behavioral/emotional problems of 2- and 3-year-old children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1987;15(4):629–650. doi: 10.1007/BF00917246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandon AY, Calkins SD, Keane SP, O’Brien M. Individual differences in trajectories of emotion regulation processes: The effects of maternal depressive symptomatology and children’s physiological regulation. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(4):1110–1123. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt KB, Obradović J, Long JD, Masten AS. The interplay of social competence and psychopathology over 20 years: Testing transactional and cascade models. Child Development. 2008;79(2):359–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Goldsmith HH. Fear and anger regulation in infancy: Effects on the temporal dynamics of affective expression. Child Development. 1998;69(2):359–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD. Regulatory competence and early disruptive behavior problems: The role of physiological regulation. In: Olson SL, Sameroff AJ, editors. Biopsychosocial regulatory processes in the development of childhood behavioral problems. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 2009. pp. 86–115. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Bell MA. Introduction: Putting the domains of development into perspective. In: Calkins SD, Bell MA, editors. Child development at the intersection of emotion and cognition. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Dedmon SE. Physiological and behavioral regulation in two-year-old children with aggressive/destructive behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28(2):103–118. doi: 10.1023/a:1005112912906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Hill A. Caregiver influences on emerging emotion regulation: Biological and environmental transactions in early development. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Howse RB. Individual differences in self-regulation: Implications for childhood adjustment. In: Philippot P, Feldman RS, editors. The regulation of emotion. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2004. pp. 307–332. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Keane SP. Developmental origins of early antisocial behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:1095–1109. doi: 10.1017/S095457940999006X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Dedmon SE, Gill KL, Lomax LE, Johnson LM. Frustration in infancy: Implications for emotion regulation, physiological processes, and temperament. Infancy. 2002;3(2):175–197. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0302_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Gill KL, Johnson MC, Smith CL. Emotional reactivity and emotional regulation strategies as predictors of social behavior with peers during toddlerhood. Social Development. 1999;8(3):310–334. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT, Fiske DW. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin. 1959;56(2):81–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Dawson G. Editorial: Multiple levels of analysis. Development and Psychopathology. Special Issue: Multiple Levels of Analysis. 2002;14(3):417–420. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402003012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8(4):597–600. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Schneider-Rosen K. An organizational approach to childhood depression. In: Rutter M, Izard C, Read P, editors. Depression in young people: Clinical and developmental perspectives. New York: Guilford Press; 1986. pp. 71–134. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Lochman JE, Terry R, Hyman C. Predicting adolescent disorder from childhood aggression and peer rejection. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60(5):783–792. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie J, Dodge K, Coppotelli H. Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18(4):557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Calkins SD, Keane SP, Hill-Soderlund AL. Profiles of disruptive behavior across early childhood: Contributions of frustration reactivity, physiological regulation, and maternal behavior. Child Development. 2008;79(5):1357–1376. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Blair KA, DeMulder E, Levitas J, Sawyer K, Auerbach-Major S, Queenan P. Preschool emotional competence: Pathway to social competence. Child Development. 2003;74(1):238–256. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, McKinley M, Couchoud EA, Holt R. Emotional and behavioral predictors of preschool peer ratings. Child Development. 1990;61(4):1145–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle A, Ostrander R, Skare S, Crosby R, August G. Convergent and criterion-related validity of the Behavior Assessment System for Children Parent Rating Scale. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26(3):276–284. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2603_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland AL, Spinrad TL, Fabes R, Shepard SA, Reiser M, Murphy BC, Losoya SH, Guthrie IK. The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing. 2001 doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Bernzweig J, Karbon M. The relations of emotionality and regulation to preschoolers’ social skills and sociometric status. Child Development. 1993;64(5):1418–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC. The relations of regulation and emotionality to problem behavior in elementary school children. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8(1):141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy B, Maszk P, Smith M, Karbon M. The role of emotionality and regulation in children’s social functioning: A longitudinal study. Child Development. 1995;66:1360–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhardt D, Hinshaw SP. Initial sociometric impressions of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and comparison boys: Predictions from social behaviors and from nonbehavioral variables. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(4):833–842. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.62.4.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. Social Skills Rating System. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm KJ, Pianta RC, Konold TR. Longitudinal multitrait-multimethod models for developmental research. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2009;44(2):233–258. doi: 10.1080/00273170902794230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt AG, Denham SA, Dunsmore JC. Affective social competence. Social Development. 2001;10(1):79–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Guerra NG. A longitudinal analysis of patterns of adjustment following peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14(1):69–89. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW. The company they keep: Friendships and their developmental significance. Child Development. 1996;67(1):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AL, Degnan KA, Calkins SD, Keane SP. Profiles of externalizing behavior problems for boys and girls across preschool: The roles of emotion regulation and inattention. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(5):913–928. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Perry DG. Personal and Interpersonal antecedents and consequences of victimization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76(4):677–675. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Boivin M, Vitaro F, Bukowski WM. The power of friendship: Protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(1):94–101. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howse RB, Calkins SD, Anastopoulos AD, Keane SP, Shelton TL. Regulatory contributors to children’s kindergarten achievement. Early Education and Development. 2003;14(1):101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Howse R, Calkins S, Anastopoulos A, Keane S, Shelton T. Regulatory contributors to children’s academic achievement. Early Education and Development. 2003;14(1):101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JA. Emotion expression processes in children’s peer interaction: The role of peer rejection, aggression, and gender. Child Development. 2001;72(5):1426–1438. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Cillessen A. Stability of continuous measures of sociometric status: A meta-analysis. Developmental Review. 2005;25(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Keane SP, Calkins SD. Predicting kindergarten peer social status from toddler and preschool problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(4):409–423. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000030294.11443.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K. Emotion dysregulation as a risk factor for child psychopathology. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000;7(4):418–434. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer-Ladd B, Wardop JL. Chronicity and Instability of Children’s Peer Victimization Experiences as Predictors of Loneliness. Child Development. 2001;72(1):134–151. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer BJ, Ladd GW. Peer victimization: Cause or consequence of school maladjustment? Child Development. 1996;67(4):1305–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konold TR, Pianta RC. The influence of informants on ratings of children’s behavioral functioning: A latent variable approach. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2007;25(3):222–236. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18(2):199–214. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynski L, Kochanska G. Function and content of maternal demands: Developmental significance of early demands for competent action. Child Development. 1995;66(3):616–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Paro KM, Rimm-Kaufman SE, Pianta RC. Kindergarten to 1stgrade: Classroom characters tics and the stability and change of children’s classroom experiences. Journal of Research in Childhood Education. 2006;21:189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Kochenderfer BJ, Coleman CC. Friendship quality as a predictor of young children’s early school adjustment. Child Development. 1996;67(3):1103–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Price JM, Hart CH. Predicting preschoolers’ peer status from their playground behaviors. Child Development. 1988;59(4):986–992. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, Prizmic Z. Affect regulation. In: Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, editors. Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 40–61. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Roisman GI, Long JD, Burt KB, Obradović J, Riley JR, Boelcke-Stennes K, Tellegen A. Developmental cascades: Linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41(5):733–746. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ. A latent difference score approach to longitudinal dynamic structural analysis. In: Cudeck R, du Toit S, Sorbom D, editors. Structural equation modeling: Present and future. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2001. pp. 342–380. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W. Measurement invariance, factor analysis and factorial invariance. Psychometrika. 1993;58(4):525–543. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W. Notes on factorial invariance. Psychometrika. 1964a;29(2):177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith W. Rotation to achieve factorial invariance. Psychometrika. 1964b;29(2):187–206. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Johnson S, Coie JD, Maumary-Gremaud A, Bierman K Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Peer rejection and aggression and early starter models of conduct disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30(3):217–230. doi: 10.1023/a:1015198612049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Bunge SA, Gross JJ, Gabrieli JDE. Rethinking feelings: An fMRI study of the cognitive regulation of emotion. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2002;14(8):1215–1229. doi: 10.1162/089892902760807212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. The cognitive control of emotion. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2005;9:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Victimization among schoolchildren: Intervention and prevention. In: Albee GW, Bond LA, Monsey TVC, editors. Improving children’s lives: Global perspectives on prevention. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1992. pp. 279–295. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavior assessment system for children(BASC) Circles Pines, MN: AGS; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, Parker JG. Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, social, emotional, and personality development. 6. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2006. pp. 571–645. [Google Scholar]

- Salisch MV. Children’s emotional development: Challenges in their relationships to parents, peers, and friends. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2001;25(4):310–319. [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Cicchetti D. Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33(6):906–916. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Cicchetti D. Parental maltreatment and emotion dysregulation as risk factors for bullying and victimization in middle childhood. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30(3):349–363. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipman K, Schneider R, Brown A. Emotion dysregulation and psychopathology. In: Beauregard M, editor. Consciousness, emotional self-regulation and the brain. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2004. pp. 61–85. [Google Scholar]

- Suveg C, Zeman J. Emotion regulation in children with anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(4):750–759. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry AW. An early glimpse: Service learning from an adolescent perspective. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education. 2000;11(3):115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA, Meyer S. Socialization of emotion regulation in the family. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE. Why socialization fails: The case of chronic physical aggression. In: Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, editors. Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 182–224. [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF. Hierarchically nested covariance structure models for multitrait-multimethod data. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1985;9(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM. Childhood peer relationship problems and later risks of educational under-achievement and unemployment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41(2):191–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]