ABSTRACT

Background and Objective

Patient-provider language barriers may play a role in health-care disparities, including obtaining colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. Professional interpreters and language-concordant providers may mitigate these disparities.

Design, Subjects, and Main Measures

We performed a retrospective cohort study of individuals age 50 years and older who were categorized as English-Concordant (spoke English at home, n = 21,594); Other Language-Concordant (did not speak English at home but someone at their provider’s office spoke their language, n = 1,463); or Other Language-Discordant (did not speak English at home and no one at their provider’s spoke their language, n = 240). Multivariate logistic regression assessed the association of language concordance with colorectal cancer screening.

Key Results

Compared to English speakers, non-English speakers had lower use of colorectal cancer screening (30.7% vs 50.8%; OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.51–0.76). Compared to the English-Concordant group, the Language-Discordant group had similar screening (adjusted OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.58–1.21), while the Language-Concordant group had lower screening (adjusted OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.46–0.71).

Conclusions

Rates of CRC screening are lower in individuals who do not speak English at home compared to those who do. However, the Language-Discordant cohort had similar rates to those with English concordance, while the Language-Concordant cohort had lower rates of CRC screening. This may be due to unmeasured differences among the cohorts in patient, provider, and health care system characteristics. These results suggest that providers should especially promote the importance of CRC screening to non-English speaking patients, but that language barriers do not fully account for CRC screening rate disparities in these populations.

KEY WORDS: language concordance, cancer screening, disparities

BACKGROUND

The United States has tremendous ethnic and linguistic diversity. According to the 2005–2007 American Community Survey, minorities comprise 26% of the population, and nearly 20% of Americans speak a language other than English at home. By 2050, it is projected that minorities will make up about half of the US population, with a similar increase in individuals speaking a language other than English at home.1 Compared to white non-Hispanics, minorities use fewer preventive services, including colorectal cancer (CRC) screening.2 Language plays a role in these health-care disparities.3, 4 Language barriers may undermine medical communication, lead to inaccurate diagnosis, and contribute to poorer management or treatment adherence.5

Of individuals who do not speak English at home, roughly 44% speak English “less than well.”1 Patient-provider communication problems may be common for individuals who have limited English proficiency (LEP).1,2,6 Compared to those with English proficiency, LEP patients are more likely to have difficulty understanding medical explanations,7 getting information,8 and have worse management of care.9 LEP patients are less likely to have preventive10 or primary care services,11 access to care,12 or be satisfied with provider communication.13 Access to, and the quality of, care for LEP patients can be improved by using professional interpreters or language-concordant providers.4

Colorectal cancer screening is recommended in the routine care of older patients in the US and may be compromised because of language barriers. CRC is the third most prevalent cancer in the US.2 Although many minorities have lower rates of CRC compared to white non-Hispanics, they tend to be diagnosed at a later stage of disease and have higher mortality rates.2 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends colonoscopy every 10 years in adults aged 50–75 years. Other recommendations include flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years or home-based fecal occult blood test (FOBT) every year.14 It is estimated that 60% of CRC deaths could be prevented if all persons age 50 years and older were screened.15

Current rates of CRC screening are less than 60%, with lower rates in minorities.16 Language appears to be a significant factor.17 Compared to white non-Hispanics, Spanish-speaking Hispanics were 43% less likely to receive CRC screening.18 Communication problems when discussing cancer screening are also documented with Vietnamese-Americans.19 Furthermore, there is evidence that fewer providers discuss CRC screening with non-English speaking patients20 even when translators are available.21

OBJECTIVE

Lack of physician recommendation is often the primary reason patients are not current with guidelines.19 Discussion of screening for CRC is complicated and time consuming, and may be omitted or abbreviated when there are language barriers.22 A recent study showed that patients who spoke Spanish at home were less likely to receive CRC screening compared to patients who spoke English at home, even after controlling for English proficiency and patient characteristics.23 However, that study did not take into account whether someone at the provider’s office spoke the patient’s preferred language. The purpose of our study is to assess the association of language concordance with CRC screening rates in patients who do not speak English at home compared to rates in those who do.

DESIGN AND SUBJECTS

We analyzed data from the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS), a nationally representative survey of non-institutionalized US civilians with 2 years of longitudinal follow-up. We used the Consolidated Household and Medical Conditions files from the Household Component Survey and the Self-Administered Questionnaire. We merged 2002, 2004 and 2006 data, choosing alternate years to ensure distinct respondents, creating a sample of 107,720 subjects. Individuals with a self-reported history of colon or rectal cancer (International Classification of Disease 9-CM codes 153, 154) and those less than 50 years were excluded, as were individuals who did not have complete responses for all variables of interest. Individuals greater than 75 years were included given lack of consensus on an upper age limit for screening. Our final study sample was 23,297 subjects, representing 222 million individuals.

MAIN MEASURES

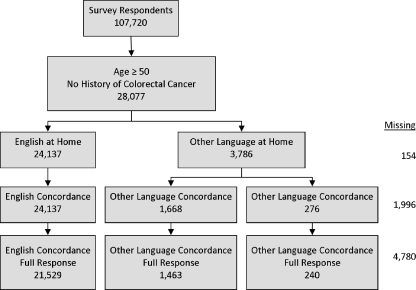

To create cohorts of patient-provider language concordance, we combined responses to the questions “What language is spoken in your home most of the time?” and “Does someone at your provider’s speak the language you prefer or provide translator services?” If English was spoken at home, the subject was categorized as English-Concordant. If English was not spoken at home and someone at the provider’s spoke the respondent’s preferred language or offered translation services, the subject was categorized as Other Language-Concordant. Subjects who reported not speaking English at home and denied that someone at their provider’s spoke their preferred language or offered translation services formed the third cohort, Other Language-Discordant (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Sample cohorts.

We assessed CRC screening using self-reported rates of FOBT and endoscopy. Given that patients may not have FOBT exactly within 12 months, we considered tests performed within 2 years prior to the date of MEPS survey completion to be current with recommendations. In MEPS data, responses for sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy were combined into a single variable with time frame choices either within or greater than 5 years of the survey date. Therefore, if an individual had FOBT within 2 years or endoscopy within 5 years, they were classified as being current with CRC screening.

Covariates included: self-reported race/ethnicity, age, education, marital status, family income, employment status, time since last check-up, and health insurance status. Race and ethnicity were combined into a variable with five categories: white non-Hispanic, black, Hispanic, Asian, and other. Age had three categories: age 50–<65 years, 65–<75 years, and age 75–85 years (this category may include subjects >85 years as MEPS top coded ages at 85). Education had four categories: no degree, high school or equivalent, some college or greater, or other. Marital status had two categories: married or not married. Total family income had four categories defined by the federal poverty line (FPL): poor/near-poor (<125% FPL), low income (125–<200% FPL), middle income (200–<400% FPL), and high income (≥400% FPL). Employment status had two categories: employed or unemployed. Time since the last checkup had three categories: within 2 years, greater than 2 years, and never. Health insurance status had three categories: any private insurance, public insurance only, and no insurance.

Co-morbidities are often considered when recommending CRC screening; however, these indices are not included in MEPS. As a proxy, the Physical Component Score (PCS) and Mental Component Score (MCS) of the 12 Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) were used. These scores have been well validated and are standardized with a mean of 50 for the general population.24 Scores were converted into two categories: scores less than the sample median (“low” PCS/MCS) and those greater than or equal to the median (“high” PCS/MCS). Sample PCS and MCS medians were 47 and 54, respectively. Of note, Medicare coverage of endoscopy for average-risk adults began in 2001, so year of survey was also included. We included US region to account for regional variations. The following provider-level variables were also included: provider race, ethnicity, and sex; and provider type and specialty.

Analysis

To account for the complex sample design, survey statistical procedures were used. Weighted prevalence and standard error (SE) estimates were calculated for independent variables using MEPS survey weights, and χ2 tests assessed for differences between cohorts. Variables with proportion of missing responses greater than 65% (provider characteristics) were eliminated. For the remaining variables, individuals with complete data were compared to those with missing data to assess generalizability. All subsequent analyses were done on samples with complete data for all variables retained (n = 23,297).

Bivariate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to evaluate the associations between each independent variable and receipt of CRC screening. Variables were independently assessed for confounding or effect modification of language concordance. Those yielding a ≥10% change in the magnitude of effect were considered as potential confounders.

We used multivariate logistic regression to determine the association of language concordance with CRC screening. We included in the model those variables determined a priori to be potentially associated with screening (sex, age, time since last checkup, marital status, employment status, year, region), as well as variables found to be confounders (race/ethnicity, education, family income, and health insurance status) or effect modifiers (PCS).

Sensitivity Analyses

We evaluated our definitions of both the primary explanatory variable and outcome variables. Patient language was re-defined by comfort level speaking English using the question “Are you comfortable conversing in English?” Individuals with LEP (those who responded “No”) were then grouped by whether someone at their provider’s spoke their preferred language or offered translation services. In this way, three cohorts based on English proficiency were created: English-proficient, LEP-Concordant and LEP-Discordant. A simple logistic regression using these re-defined cohorts was compared to that using the original cohorts based on language spoken at home. In addition, receipt of CRC screening was re-defined in several ways. We assessed receipt of FOBT alone, endoscopy alone, endoscopy ever, and any screen ever.

All prevalence, odds ratio, and variance estimates are presented from weighted analyses unless otherwise specified. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05. All analyses were conducted with SAS (version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). This study was granted exempt status by the Boston University Institutional Review Board.

KEY RESULTS

The final study sample of 23,297 represents 222 million individuals age 50 years or older with no history of CRC. The vast majority of respondents spoke English at home (96%). Overall, most were white non-Hispanic (81.1%), had at least a high school education (75.5%), were married (61.8%), were aged 50–64 years (57.8%), were female (54.7%), and were employed (51.3%). Few were uninsured (6.1%).

The English-Concordant cohort was predominantly white non-Hispanic (83.7%), more likely to have a high school education, and to have high income and private insurance (Table 1). The Other Language-Concordant cohort had the highest prevalence of Hispanics (60.9%), was the least educated, and most likely to be poor, have public health insurance, and be from the west. The Other Language-Discordant cohort had the highest percentage of Asians (29.4%) and those 75-85 years (29.6%), and was most likely to be unemployed or uninsured. The three cohorts were similar regarding sex, marital status, and time since last checkup. Given the large sample size, the cohorts were statistically different for all covariates except marital status (p = 0.13).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Population by Language Concordance

| Variable | English concordance (N = 21,594) | Other language concordance (N = 1,463) | Other language discordance (N = 240) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Weighted % (SE) | n | Weighted % (SE) | n | Weighted % (SE) | |

| Male sex | 9,402 | 45 (0.25) | 559 | 43 (1.32) | 86 | 39 (3.10) |

| Age | ||||||

| 50–64 | 12,420 | 58.0 (0.58) | 802 | 54.5 (2.19) | 125 | 48.1 (4.15) |

| 65–74 | 4,896 | 22.1 (0.41) | 355 | 25.8 (1.65) | 54 | 22.3 (3.43) |

| 75–85 | 4,278 | 19.9 (0.47) | 306 | 19.6 (1.52) | 61 | 29.6 (3.93) |

| Race | ||||||

| White non-Hispanic | 16,350 | 83.7 (0.62) | 102 | 14.0 (1.90) | 41 | 23.2 (4.37) |

| Black | 3,271 | 9.7 (0.48) | 16 | 1.5 (0.57) | 7 | 3.5 (1.42) |

| Hispanic | 1,149 | 3.1 (0.22) | 1,152 | 60.9 (2.65) | 138 | 42.2 (4.88) |

| Asian | 350 | 1.5 (0.15) | 174 | 22.3 (2.56) | 51 | 29.4 (4.30) |

| Other | 474 | 2.0 (0.21) | 19 | 1.4 (0.44) | 3 | 1.7 (1.18) |

| Education | ||||||

| No degree | 4,387 | 15.5 (0.38) | 1,058 | 63.3 (2.17) | 144 | 49.5 (4.83) |

| High school Or GED | 10,905 | 51.5 (0.55) | 266 | 21.9 (1.65) | 57 | 27.3 (4.03) |

| College or greater | 4,801 | 25.5 (0.59) | 107 | 11.8 (1.40) | 32 | 19.2 (3.35) |

| Other | 1,501 | 7.5 (0.24) | 32 | 3.0 (0.62) | 7 | 4.0 (1.59) |

| Married | 12,754 | 61.7 (0.55) | 915 | 65.9 (1.87) | 144 | 61.5 (4.38) |

| Income* | ||||||

| Poor/near poor | 3,863 | 12.7 (0.36) | 565 | 31.2 (1.73) | 68 | 22.6 (3.63) |

| Low income | 2,947 | 12.8 (0.35) | 318 | 19.9 (1.54) | 75 | 27.6 (4.13) |

| Middle income | 5,951 | 27.6 (0.48) | 410 | 31.8 (1.98) | 49 | 22.6 (3.69) |

| High income | 8,833 | 46.9 (0.67) | 170 | 17.1 (1.67) | 48 | 27.2 (4.32) |

| Insurance | ||||||

| Any private | 14,823 | 74.2 (0.54) | 401 | 36.5 (2.46) | 87 | 37.1 (4.10) |

| Public | 5,281 | 20.0 (0.49) | 820 | 50.8 (2.58) | 111 | 48.5 (4.14) |

| Uninsured | 1,490 | 5.8 (0.22) | 242 | 12.7 (1.32) | 42 | 14.4 (2.78) |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 3,588 | 19.3 (0.86) | 227 | 20.7 (2.20) | 48 | 21.5 (3.82) |

| Midwest | 5,033 | 23.9 (0.99) | 56 | 5.9 (1.01) | 23 | 12.9 (3.61) |

| South | 8,661 | 37.1 (1.06) | 545 | 29.9 (2.91) | 88 | 30.9 (4.73) |

| West | 4,312 | 19.7 (0.97) | 835 | 43.6 (3.00) | 81 | 34.7 (5.39) |

| Time since last checkup | ||||||

| ≤2 years | 18430 | 85.9 (0.38) | 1,269 | 88.0 (1.13) | 215 | 90.2 (2.80) |

| >2 years | 2468 | 11.2 (0.29) | 107 | 7.1 (0.78) | 10 | 3.1 (1.26) |

| Never | 696 | 2.8 (0.19) | 87 | 5.0 (0.80) | 15 | 6.7 (2.44) |

| Employed | 10,483 | 51.8 (0.55) | 528 | 39.3 (2.10) | 76 | 33.3 (3.71) |

| Physical component score† | ||||||

| Low | 10,625 | 46.0 (0.51) | 874 | 57.2 (1.70) | 146 | 56.6 (4.40) |

| High | 10,969 | 54.0 (0.51) | 589 | 42.8 (1.70) | 94 | 43.4 (4.40) |

| Mental component score† | ||||||

| Low | 10,505 | 46.1 (0.44) | 994 | 66.5 (1.80) | 149 | 60.8 (3.63) |

| High | 1,108 | 53.9 (0.44) | 469 | 33.5 (1.80) | 91 | 39.2 (3.63) |

SE = standard error;

*Poor/near-poor (<125% Federal Poverty Level), low (125–<200 % FPL), middle (200–<400% FPL), high (≥400% FPL), †low = scores < median of the study population; high = scores ≥ median of the study population

The prevalence of CRC screening was greatest in the English-Concordant group, followed by the Other Language-Discordant group, and then the Other Language-Concordant group (50.8% vs 37.9% vs 28.9%, respectively). Compared to the English-Concordant cohort, the unadjusted odds of being current with CRC screening for Other Language-Concordant patients was 0.40 (95% CI, 0.33–0.47) and for Other Language-Discordant patients was 0.59 (95% CI, 0.42–0.84) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association of Independent Variables with Colorectal Cancer Screening

| Variable (n in thousands) | Unadjusted odds ratio* | Adjusted odds ratio† |

|---|---|---|

| (95% Confidence interval) | (95% Confidence interval) | |

| Concordance | ||

| English (ref) (21.6) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Other concordance (1.4) | 0.40 (0.33–0.47) | 0.57 (0.46–0.71) |

| Other discordance (0.2) | 0.59 (0.42–0.84) | 0.84 (0.58–1.2) |

| Age | ||

| 50–64 (ref) (13.3) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 65–74 (5.3) | 1.74 (1.62–1.88) | 1.55 (1.42–1.70) |

| 75–85 (4.6) | 1.39 (1.28–1.51) | 1.22 (1.10–1.35) |

| Sex | ||

| Male (ref) (10) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Female (13.3) | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) | 0.88 (0.83–0.94) |

| Race | ||

| White non-Hispanic (ref) (16.5) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Black (3.3) | 0.80 (0.72–0.89) | 0.97 (0.88–1.08) |

| Hispanic (2.4) | 0.57 (0.50–0.64) | 0.92 (0.79–1.07) |

| Asian (0.6) | 0.55 (0.45–0.68) | 0.60 (0.48–0.76) |

| Other (0.5) | 0.70 (0.57–0.86) | 0.83 (0.67–1.03) |

| Income‡ | ||

| High income (ref) (9.1) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Middle income (6.4) | 0.79 (0.73–0.86) | 0.88 (0.81–0.96) |

| Low income (3.3) | 0.67 (0.60–0.74) | 0.74 (0.66–0.84) |

| Poor/near poor (4.5) | 0.59 (0.53–0.65) | 0.70 (0.62–0.80) |

| Education level | ||

| College (ref) (4.9) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| High school or GED (11.2) | 0.72 (0.67–0.78) | 0.74 (0.68–0.80) |

| No degree (5.6) | 0.47 (0.43–0.51) | 0.51 (0.46–0.58) |

| Other (1.5) | 0.74 (0.65–0.84) | 0.77 (0.67–0.89) |

| Insurance coverage | ||

| Any private (ref) (15.3) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Public only (6.2) | 0.83 (0.77–0.90) | 0.87 (0.79–0.96) |

| Uninsured (1.7) | 0.28 (0.24–0.32) | 0.54 (0.46–0.63) |

| Year | ||

| 2002 (ref) (8.7) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 2004 (7.1) | 1.11 (1.03–1.19) | 1.09 (1.01–1.18) |

| 2006 (7.5) | 1.23 (1.14–1.34) | 1.25 (1.15–1.35) |

| Region | ||

| Northeast (ref) (3.9) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Midwest (5.1) | 0.85 (0.73–0.99) | 0.91 (0.79–1.05) |

| South (9.3) | 0.81 (0.70–0.94) | 0.89 (0.77–1.03) |

| West (5.0) | 0.80 (0.69–0.92) | 0.91 (0.78–1.05) |

| Physical component score§ | ||

| High (ref) (11.7) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Low (11.6) | 1.17 (1.11–1.24) | 1.14 (1.07–1.22) |

| Mental component score§ | ||

| High (ref) (11.6) | 1.0 | n/a |

| Low (11.6) | 0.88 (0.83–0.94) | |

| Employment | ||

| Employed (ref) (11.1) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Not employed (12.2) | 1.33 (1.25–1.41) | 1.35 (1.24–1.46) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married (ref) (13.8) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Not married (9.5) | 0.78 (0.72–0.83) | 0.90 (0.83–0.98) |

| Time since last checkup | ||

| Never (ref) (0.8) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| >2 years (2.6) | 0.84 (0.64–1.12) | 0.78 (0.59–1.03) |

| ≤2 years (19.9) | 4.37 (3.34–5.70) | 3.59 (2.77–4.65) |

*Odds ratios determined from weighted sample

†Adjusted for all variables in table except MCS

‡Poor/near-poor (<125% Federal Poverty Level), low (125–<200 % FPL), middle (200–<400% FPL), high (≥400% FPL)

§Low = scores less than the median of the study population; high = scores greater than or equal to the median of the study population

After adjusting for confounding, demographic and socioeconomic variables, the odds of being current with CRC screening for those who did not speak English at home was lower compared to those who did (30.7% vs 50.8%, respectively; OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.51–0.76).

When looking at patient-provider language concordance determined by language spoken at home and if someone at the provider’s spoke the patient’s preferred language, the adjusted odds of being current with CRC screening was lower for those in the Other Language-Concordant cohort compared to those in the English-Concordant cohort (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.46–0.71). The Other Language-Discordant cohort did not statistically differ from the English-Concordant cohort (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.58–1.21) (Table 2).

Sensitivity Analyses

Defining language concordance using English proficiency rather than language spoken at home did not change the patterns of association with CRC screening (LEP-Discordant: OR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.20–0.83; LEP-Concordant: OR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.19–0.37, referent to English-proficient). Furthermore, using different definitions of CRC screening (e.g., FOBT only, endoscopy only, endoscopy ever, and any screen ever) also yielded similar patterns of association, with lower rates of CRC screening in individuals who did not speak English at home compared to those who did, and higher rates of CRC screening in the Other Language-Discordant cohort compared to the Other Language-Concordant cohort (data not shown).

CONCLUSIONS

We found that individuals who do not speak English at home are less likely to be adherent with CRC screening compared to those who do. This is consistent with other reports.3,10,23 However, in our adjusted model, we found that the Other Language-Discordant cohort is as likely as the English-Concordant cohort to be adherent to CRC screening guidelines, while the Other Language-Concordant cohort is less likely to be adherent. This was unexpected. We hypothesized that the Other Language-Concordant cohort would experience better communication with their providers compared to the Other Language-Discordant cohort, thereby leading to higher CRC screening rates.

These findings might be due to differences between the Other Language-Concordant and Other Language-Discordant cohorts. Compared to the Other Language-Concordant group, the Other Language-Discordant respondents were less likely to be Hispanic (42% vs 61%) and more likely to be white non-Hispanic (23% vs 14%). They were also more likely to have attended college (19% vs 12%) and have a high income (27% vs 17%). Income and education are predictors of preventive health-care use;25 however, these variables were controlled for in our model.

The discrepancy in CRC screening between the Other Language-Concordant and Other Language-Discordant groups may also be related to other unmeasured differences between the two groups. For example, provider cultural competence7,13,26,27 and better quality of communication between patients and providers4,22 are associated with higher CRC screening rates. Similarly, rates are higher with greater patient acculturation28 and health literacy.9,27,29 While these variables have been shown to be associated with CRC screening rates, we were unable to measure and include them in our study.

There are additional limitations to this study. It is possible that individuals who do not speak English at home speak English well enough to communicate adequately but answered that someone at their provider’s office did not speak their language. These individuals would be misclassified as Other Language-Discordant. As a result, our cohorts may not have appropriately captured patient-provider language barriers. Some suggest that LEP is a better measure of language barriers.4 To address this, alternatively defined cohorts based on comfort speaking English were used. Results in an unadjusted model were similar to those based on language spoken at home. Therefore, regardless of how we defined language concordance, our results suggest that individuals who are ‘other language-concordant’ with their providers have lower adherence to CRC screening.

In addition, our definition of being adherent to CRC screening guidelines is conservative and may misclassify some as non-adherent. To address this, multivariate models substituting adherence to current CRC guidelines with other CRC screening outcomes were analyzed. Results showed similar findings; individuals in the Other Language-Discordant groups had higher rates for each of the CRC testing outcomes compared to individuals in the Other-Language Concordant group. Furthermore, we could not identify if FOBT or endoscopy was done for diagnostic purposes due to symptoms or in individuals with higher risk, such as those with family history of CRC, which could overestimate CRC screening rates. We did not control for patient co-morbidities, which may influence the appropriateness of screening. As a proxy for co-morbidities, however, we included physical summary health status scores (PCS) in our multivariate model.30

Similar to prior studies, our results suggest that speaking a language other than English at home is associated with lower CRC screening. In addition, in our adjusted model we found that individuals who do not speak English at home and do not have anyone at their provider’s who speaks their preferred language had CRC screening rates comparable to English speakers, while those who do not speak English at home and have someone at their provider’s who speaks their preferred language, had lower rates. These findings may be related to unmeasured differences between the two cohorts, including patient characteristics, provider cultural competence, patient acculturation, the quality of patient-provider communication, and the level of patient health literacy. Our results suggest that providers should especially promote the importance of CRC screening to non-English speaking patients, but that patient-provider language barriers do not fully account for lower CRC screening in patients who do not speak English at home.

Acknowledgements

This research was unfunded. Results were presented in poster format at the national meetings of the American College of Preventive Medicine, February 2010, Washington DC and AcademyHealth, June 2010, Boston MA.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Census Bureau, American FactFinder. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/ Accessed August 19, 2010.

- 2.National Healthcare Disparities Report, 2008. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/qrdr08.htm Accessed August 19, 2010.

- 3.Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, Svaer BG. Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity and language among the insured. Med Care. 2002;40:52–59. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(3):255–299. doi: 10.1177/1077558705275416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavizzo-Mourey R. Improving quality of US health care hinges on improving language services. JGIM. 2007;22(Suppl 2):279–280. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0382-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins KS, Hughes DL, Doty MM, Ives BL, Edwards JN, Tenney K. Diverse communities, common concerns: assessing health care quality for minority americans. The Commonwealth Fund, 2002. Available at: http://www.cmwf.org publication number 523 Accessed August 19, 2010.

- 7.Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, Wang F, Fernandez A. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. JGIM. 2005;20:800–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pippins JR, Alegria M, Haas JS. Association between language proficiency and the quality of primary care among a national sample of insured Latinos. Med Care. 2007;45:1020–1025. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31814847be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan KS, Keeler E, Schonlau M, Rosen M, Mangione-Smith R. How do ethnicity and primary language spoken at home affect management practices and outcomes in children and adolescents with asthma? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:283–289. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng EM, Chen A, Cunningham W. Primary language and receipt of recommended health care among Hispanics in the United States. JGIM. 2007;22(Suppl 2):283–288. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0346-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu DJ, Covell RM. Health care usage by Hispanic outpatients as a function of primary language. West J Med. 1986;144(4):490–493. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ponce NA, Hays RD, Cunningham WE. Linguistic disparities in health care access and health status among older adults. JGIM. 2006;21:786–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harmsen JAM, Bernsen RMD, Bruijnzeels MA, Meeuwesen L. Patients’ evaluation of quality of care in general practice: what are the cultural and linguistic barriers? Pat Educ Couns. 2008;72:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, Beil T, Fu R. Screening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:638–658. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jamal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(1):43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterson NB, Murff HJ, Ness RM, Dittus RS. Colorectal cancer screening among men and women in the United States. J Womens Health. 2007;16(1):57–65. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Natale-Pereira A, Marks J, Vega M, Mouzon D, Hudson S, Salas-Lopex D. Barriers and facilitators for colorectal cancer screening practices in the Latino community: perspectives from community leaders. Cancer Control. 2008;15(2):157–165. doi: 10.1177/107327480801500208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diaz JA, Roberts MB, Goldman RE, Weitzen S, Eaton CB. Effect of language on colorectal cancer screening among Latinos and non-Latinos. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(8):2169–2173. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen GT, Barg FK, Armstrong K, Holmes JH, Hornik RC. Cancer and communication in the health care setting: experiences of older Vietnamese immigrants, a qualitative study. JGIM. 2007;23(10):45–50. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0455-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Phillips RS. Factors associated with colon cancer screening: the role of patient factors and physician counseling. Prev Med. 2005;41:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guerra CE, Schwartz JS, Armstrong K, Brown JS, Halbert CH, Shea JA. Barriers of and facilitators to physician recommendation of colorectal cancer screening. JGIM. 2007;22(12):1681–1688. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0396-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn AS, Shridharani KV, Lou W, Bernstein J, Horowitz CR. Physician-patient discussions of controversial cancer screening tests. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:130–134. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00288-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carcaise-Edinboro P, Bradley CJ. Influence of patient-provider communication on colorectal cancer screening. Med Care. 2008;46:738–745. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318178935a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form health survey. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hershey JC, Luft HS, Gianaris JM. Making sense out of utilization data. Med Care. 1975;13(10):838–854. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197510000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolf MS, Baker DW, Makoul G. Physician-patient communication about colorectal cancer screening. JGIM. 2007;22(11):1493–1499. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0289-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Ware JE, Tarlov AR. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:213–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Etzioni DA, Ponce NA, Babey SH, et al. A population-based study of colorectal cancer test use: results from the 2001 California Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2004;101:2523–2532. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Perez-Stable EJ, Bibbins-Domingo K, Williams BA, Schillinger D. Unraveling the relationship between literacy, language proficiency, and patient-physician communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:398–402. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kazis LE, Nethercot VA, Ren XS, Lee A, Selim A, Miller DR. Medication effectiveness studies in the United States Veterans Administration health care system: a model for large integrated delivery systems. Drug Dev Res. 2006;67:217–226. doi: 10.1002/ddr.20080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]