Abstract

Background

Portal biliopathy (PBP) denotes intra- and extrahepatic biliary duct abnormalities that occur as a result of portal hypertension and is commonly seen in extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO). The management of symptomatic PBP is still controversial.

Methods

Prospectively collected data for surgically managed PBP patients from 1996 to 2007 were retrospectively analysed for presentation, clinical features, imaging and the results of surgery. All patients were assessed with a view to performing decompressive shunt surgery as a first-stage procedure and biliary drainage as a second stage-procedure if required, based on evaluation at 6 weeks after shunt surgery.

Results

A total of 39 patients (27 males, mean age 29.56 years) with symptomatic PBP were managed surgically. Jaundice was the most common symptom. Two patients in whom shunt surgery was unsuitable underwent a biliary drainage procedure. A total of 37 patients required a proximal splenorenal shunt as first-stage surgery. Of these, only 13 patients required second-stage surgery. Biliary drainage procedures (hepaticojejunostomy [n = 11], choledochoduodenostomy [n = 1]) were performed in 12 patients with dominant strictures and choledocholithiasis. One patient had successful endoscopic clearance of common bile duct (CBD) stones after first-stage surgery and required only cholecystectomy as a second-stage procedure. The average perioperative blood product transfusion requirement in second-stage surgery was 0.9 units and postoperative complications were minimal with no mortality. Over a mean follow-up of 32.2 months, all patients were asymptomatic. Decompressive shunt surgery alone relieved biliary obstruction in 24 of 37 patients (64.9%) and facilitated a safe second-stage biliary decompressive procedure in the remaining 13 patients (35.1%).

Conclusions

Decompressive shunt surgery alone relieves biliary obstruction in the majority of patients with symptomatic PBP and facilitates endoscopic or surgical management in patients who require second-stage management of biliary obstruction.

Keywords: portal biliopathy, extrahepatic portal vein obstruction, portal hypertension, biliary obstruction

Introduction

The term ‘portal biliopathy’ (PBP) encompasses intra- and extrahepatic biliary duct and gallbladder wall abnormalities seen in portal hypertension. The changes associated with PBP are common in portal hypertension as a result of extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO),1–4 which accounts for up to 40% of cases of portal hypertension in India.5,6 However, in most patients, PBP remains asymptomatic and gives rise to obstructive jaundice only in a minority (5–33%) of cases.1,3,7,8 Early and adequate alleviation of the biliary obstruction in this condition is essential because it appears to be a late9,10 and progressive 3 manifestation of EHPVO and, if unrelieved, may lead to secondary biliary cirrhosis.11,12

The management of symptomatic PBP remains controversial and various treatment options have been described in the literature. In this paper, we describe our institution's experience in the surgical treatment of patients with symptomatic PBP over a period of 11 years (1996–2007) and present an algorithmic approach to the management of these patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest series of surgically treated PBP patients to be reported.

Materials and methods

Prospectively collected data pertaining to patients with symptomatic PBP, who were treated surgically over an 11-year period from June 1996 to December 2007, were analysed retrospectively. Patients with malignancy as the cause of either portal vein obstruction or biliary symptoms were excluded from the study.

Investigation of these patients consisted of routine haematologic investigations, liver function tests (LFTs), cholangiography in the form of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE) and Doppler ultrasonography (Doppler USG). The preferred cholangiographic study for assessment of the biliary obstruction was MRCP. The diagnosis of EHPVO was based on the Doppler USG finding of replacement of the portal vein by a portal cavernoma. Doppler USG was also utilized to determine the size and patency of the splenic vein, the superior mesenteric vein, the hepatic veins and the left renal vein, and for assessment of collaterals. Oesophageal varices were classified according to the grading system of Conn and Brodoff (Grade 1, small varices appearing on Valsalva manoeuvre only; Grade 2, varices of 1–3 mm in diameter appearing without Valsalva manoeuvre; Grade 3, variceal diameter 3–6 mm; Grade 4, variceal diameter >6 mm).13 In some patients presenting with cholangitis or high bilirubin levels, endoscopic biliary stent placement was necessary prior to shunt surgery.

The management protocol of these patients included two stages. In the first stage, patients underwent a portal decompressive procedure in the form of proximal splenorenal shunt (PSRS) surgery to decompress the portal cavernoma responsible for the biliopathy. Intraoperative assessment of the suitability and feasibility of the procedure was performed. Following splenectomy, the splenic vein was dissected to obtain an adequate length and a splenic-vein-to-left-renal-vein shunt was formed in an end-to-side fashion with a 5–0 or 6–0 polypropylene suture. Intraoperative portal pressure was measured at the omental branch of the gastroepiploic vein at the beginning and after completion of the shunt to assess the adequacy of the shunt. Intraoperative Tru-Cut liver biopsy was performed. Intraoperative blood loss and duration of surgery were noted. Postoperative blood transfusion requirements, period of intensive care unit (ICU) stay, LFTs, morbidity and mortality were recorded.

Six weeks after shunt surgery, the patients were re-evaluated for the resolution of symptoms and improvement in LFTs. Shunt patency was assessed by Doppler USG and UGIE was performed to assess any resolution or regression in the grade of varices. Regression in variceal status by more than one grade was taken as an indirect indicator of shunt patency. Venography was not used routinely to assess shunt patency because of its invasiveness.

Patients without any dominant biliary abnormality on preoperative imaging and without biliary symptoms were followed up by clinical evaluation, LFTs and Doppler USG at 3-monthly intervals for 2 years and 6-monthly thereafter. Patients with dominant biliary abnormalities or persistent biliary symptoms during follow-up underwent cholangiographic study, preferably MRCP, which was compared with preoperative imaging. Patients with persistent strictures were scheduled for surgical biliary drainage procedure. Patients with intraluminal obstruction caused by biliary calculi or sludge, but without any biliary stricture, underwent endoscopic management. Indications for second-stage surgery therefore included persistence of a dominant biliary stricture, failure of endoscopic clearance of common bile duct (CBD) calculi, non-resolution of jaundice along with elevated LFTs, and symptomatic cholelithiasis. These patients were studied for their symptoms, indication and type of second-stage surgery, operative findings, duration of surgery, intraoperative blood loss, intraoperative and postoperative blood transfusion requirements, morbidity and mortality. Regular follow-up at 3-monthly intervals with serial LFTs and abdominal USG was maintained.

Results

A total of 311 patients with portal hypertension, including 177 patients with EHPVO, underwent surgical treatment for portal hypertension during the study period. Among the patients with EHPVO, 39 patients (27 males, 12 females) with symptomatic PBP were treated surgically during this period. These patients constitute the study group. The mean age of these patients was 29.6 ± 12.5 years (range: 13–56 years). The clinical features of these patients, including their various presenting symptoms, physical findings and profiles of biliary obstructive symptoms, are listed in Table 1. Fifteen (38.5%) patients had undergone endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) and stenting, mostly for the management of acute cholangitis that was unresponsive to antibiotics. The number of stent procedures carried out in each patient in this group ranged from one to five (mean 2.1 ± 1.4). A history of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage was present in 33 (84.6%) patients. Upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding preceded jaundice in 23 patients by a mean of 9.2 ± 7.4 years (range: 1–28 years). Twenty-three patients of these 33 patients (69.7%) had undergone endoscopic therapy for varices prior to admission. Six (15.4%) patients were non-bleeders and exhibited jaundice as their sole presentation; EHPVO was diagnosed in all of these during the evaluation of jaundice. Prior to diagnosis, these patients had experienced recurrent jaundice for a mean of 8.6 ± 5.4 years (range: 1.5–14 years).

Table 1.

Salient clinical features of symptomatic portal biliopathy patients presenting for surgical management

| Clinical feature | |

|---|---|

| History of jaundice, n (%) | 39 (100%) |

| Jaundice at presentation, n (%) | 28 (71.8%) |

| Jaundice as sole presentation, n (%) | 6 (15.4%) |

| History of cholangitis, n (%) | 24 (61.5%) |

| Number of cholangitis episodes, mean (range) | 6.3 ± 5.5 (1–25) |

| Variceal bleed, n (%) | 33 (84.6%) |

| Abdominal pain, n (%) | 24 (61.5%) |

| Palpable spleen, n (%) | 34 (87.2%) |

| Symptomatic splenomegaly, n (%) | 3 (7.6%) |

| Hypersplenism, n (%) | 7 (17.9%) |

| Hepatomegaly, n (%) | 25 (64.1%) |

| Ascites (mild), n (%) | 1 (2.6%) |

| Peripheral signs of liver cell failure, n | 0 |

Investigations

Serum bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase were elevated in most of the patients (mean serum bilirubin 4.9 ± 3.7 mg/dl; mean serum alkaline phosphatase 575 ± 307 IU/l), whereas serum AST (aspartate aminotransferase) and ALT (alanine aminotransferase) were within normal limits in most patients. Mean serum albumin was 3.8 ± 0.5 mg/dl (range: 2.7–4.8 mg/dl). Prothrombin time (PT) was found to be abnormal in 11 patients and was easily correctable. Abdominal USG findings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Findings on ultrasonography

| Finding | Patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Dilated intrahepatic biliary radicles | 37 (94.9%) |

| Dilated common bile duct | 32 (82.1%) |

| Gallstones | 12 (30.8%) |

| Bile duct stones | 7 (17.9%) |

| Splenomegaly | 39 (100%) (massive enlargement: 12 [30.8%]) |

| Ascites | 3 (7.7%) |

| Liver echotexture alteration | 9 (23.1%) |

Doppler USG confirmed the presence of portal cavernoma in all patients and the patency of the splenic vein in 38 patients (97.4%). In one patient, the splenic vein was well visualized proximally but not distally, which, along with the presence of collaterals in the region of the superior mesenteric vein, indicated extensive splenoportal venous thrombosi. This patient underwent hepaticojejunostomy without prior shunt surgery.

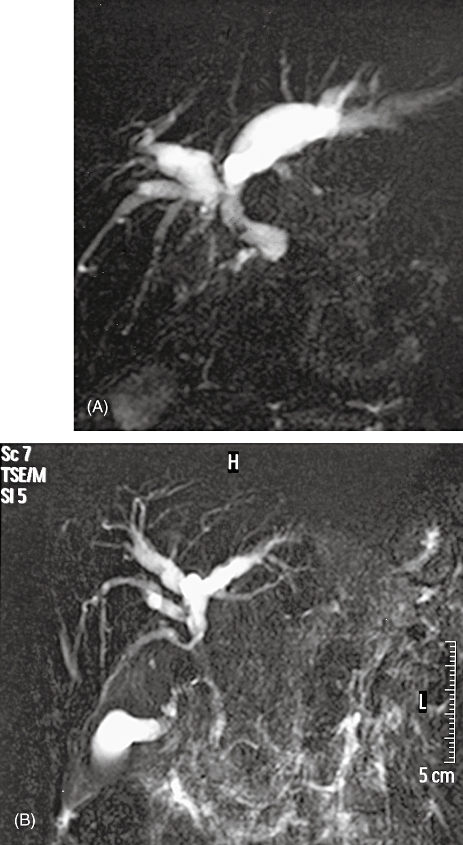

Cholangiographic studies were evaluated with the aim of diagnosing, characterizing and categorizing the PBP changes (Fig. 1). Intrahepatic biliary radicle dilatation (all 100%), predominantly involving the left system, was present in all patients and ectasia of the extrahepatic biliary system was present in 79.5% of patients. Fifteen patients (38.5%) had dominant biliary strictures (Bismuth type I-9 and type II-6)14 and four patients had multiple strictures. None of the patients had intrahepatic biliary strictures. Other abnormalities noted included angulations (n = 8, 20.5%), indentations (n = 16, 41.0%), filling defects (n = 12, 30.8%), calibre (n = 11, 28.2%) or outline (n = 17, 43.6%) irregularities and external compression (n = 7, 17.9%).

Figure 1.

MRCP findings in portal biliopathy

All patients had documented oesophageal/gastric varices at admission. One patient (2.6%) had completely obliterated varices, whereas the remaining patients (38) had oesophageal grade 1–4 varices. In addition, 21 patients had undergone ERC (with or without stent insertion) prior to admission.

Management

Surgical procedures

All 39 patients were investigated with a view to shunt surgery as the first stage of management. Two patients could not undergo PSRS in the first stage. One patient with endoscopic management failure for recurrent cholangitis and choledocholithiasis was considered to have extensive splenoportal venous thrombosis, which precluded shunt surgery; this patient underwent biliary surgery directly. Another patient was found to have a small, shrunken, nodular liver on intraoperative assessment and was considered unsuitable for shunt surgery in view of an associated higher incidence of postoperative liver decompensation and clinical/subclinical hepatic encephalopathy in the long term; this patient underwent oesophagogastric devascularization with hepaticojejunostomy instead.

First-stage surgery: PSRS

Thirty-seven (94.9%) patients underwent PSRS as the first phase of management. Perioperative results are summarized in Table 3. Six (16.2%) patients required postoperative ventilatory support for a mean of 1.7 days. Mean ICU and hospital stays were 2.7 ± 1.3 days and 6.6 ± 3.1 days, respectively. There was no mortality in the postoperative period. One patient required re-exploration for an intra-abdominal bleed on the first postoperative day and recovered well thereafter. None of the patients demonstrated any increased disturbance of liver function or post-shunt encephalopathy.

Table 3.

Perioperative results of proximal splenorenal shunt surgery

| Result | |

|---|---|

| Duration of surgery, mean | 5.5 ± 1.6 h |

| Intraoperative blood loss, mean | 383 ± 318 ml |

| Intraoperative blood transfusions, mean | 0.99 ± 0.98 U |

| Fever, n (%) | 12 (32.4%) |

| Wound infection, n (%) | 7 (18.9%) |

| Postoperative intra-abdominal bleed, n (%) | 1 (2.7%) |

| Ascites, n (%) | 5 (13.5%) |

Follow-up after PSRS

In the 37 patients who underwent PSRS, shunt patency was assessed by Doppler USG to visualize direct evidence of shunt patency or to provide indirect evidence of shunt patency by demonstrating hepatofugal flow, and UGIE to evaluate the decrease in size or disappearance of varices. When these two studies were evaluated in combination, 36 patients (97.3%) were considered to have patent shunts during the follow-up after PSRS. Twelve of 13 patients (92.3%) undergoing second-stage surgery were considered to have patent shunts. Shunt patency in the remaining patient was considered to be doubtful on Doppler USG.

The most common symptoms observed during follow-up were cholangitis (n = 14, recurrent in 12 patients) and abdominal pain (n = 7). Endoscopic management was carried out in 10 patients for recurrent cholangitis (n = 4), CBD calculi (n = 3), and for both CBD calculi and cholangitis (n = 3). It was successful in two (20.0%) patients and was considered to have failed in eight (80.0%).

Fourteen patients continued to have persistently abnormal LFTs during follow-up. These patients had a persistent dominant biliary abnormality in the form of stricture (n = 13) or angulation (n = 1). Dominant biliary abnormalities noticed on preoperative imaging did not show any significant reversal. No significant progression in these abnormalities was observed in most of these patients.

Out of these 14 patients, 13 proceeded to second-stage biliary surgery. One patient with a biliary stricture underwent successful endoscopic clearance of CBD stones with normalization of LFTs during the follow-up period. The procedures performed included 12 biliary drainage procedures (hepaticojejunostomy [n = 11], choledochoduodenostomy [n = 1]). These patients had dominant strictures (n = 11) and angulation of CBD (n = 1). The remaining patient underwent successful endoscopic clearance of CBD stones after first-stage surgery and required only cholecystectomy in the second stage for gallstones. The median time between first- and second-stage surgery was 6.1 months.

The mean duration of second-stage surgery was 4.5 ± 2.0 h. Mean blood loss was 280 ± 300 ml. Blood transfusion was required in only two patients intraoperatively and in three patients postoperatively. Postoperative complications occurred in 11 patients. These included postoperative pyrexia (n = 6), minor wound infection (n = 8), ascites (n = 2) and biliary leak (n = 2). None of these patients required any surgical or radiologic interventions for these complications and all were managed conservatively. There was no postoperative mortality. Two patients have been lost to follow-up. The remaining patients are asymptomatic and well after a mean follow-up of 32 months (range: 5–129 months).

Discussion

Portal biliopathy is reported in 80–100% cases of EHPVO1–4 and, as EHPVO accounts for 40% of portal hypertension cases in India,5,6 PBP cases are more commonly seen in this country than in Western nations. Portal biliopathy manifests with symptoms of biliary obstruction in only 5–14% of cases.1,3,7,8 In the present series, symptomatic PBP constituted 22% of surgically treated EHPVO cases. The reason for this relatively higher proportion may relate to the fact that the present series consists of only surgically treated EHPVO and PBP patients and may not reflect the actual percentage of EHPVO patients with symptomatic PBP.

Many pathogenic mechanisms are postulated to cause PBP changes; these include the opening up and dilatation of the epicholedochal15 and pericholedochal16 venous plexuses pressing on the thin and pliable bile ducts,7,17,18 the formation of new vessels and connective tissue resulting in solid tissue around the ducts,7,19,20 and an extension of the thrombotic process to small venules of the bile ducts causing ischaemia of the bile duct3,18 and possibly giving rise to ischaemic cholangitis.21 These processes may lead to stasis, cholangitis, choledocholithiasis1 and stricture formation.3 A combination of these lead to the multitudinous cholangiographic abnormalities seen in PBP.1–3,7–8,22–23

Multiple treatment options have been described in the literature. Endoscopic management has been reported to be successful,24–27 although it may be hazardous if interventions such as papillotomy, dilatation or stone extraction are performed in the presence of collaterals in the region.28,29 In addition, although endoscopic management may temporarily relieve the biliary obstruction, it does not treat its underlying cause and cannot therefore be expected to be effective in the long term. Direct surgical approaches to the biliary system in EHPVO are also hazardous as a result of the presence of collaterals in the region. By decompressing these collaterals, total porto-systemic shunt surgery usually relieves the choledochal obstruction in PBP and, even in those with persistent biliary obstruction after shunt surgery, access to the region is possible.30,31 It also makes endoscopic management, if required, less hazardous and has the advantage of being a one time treatment option for these relatively young patients with long life expectancies, which deals with the symptomatic splenomegaly and hypersplenism they display.32–34

The various mechanisms postulated to cause biliary obstruction in PBP do not seem to be mutually exclusive, but it is possible that pressure effects predominate, at least in the early stages. This is reflected in the results of shunt surgery in these patients. Biliary obstruction in PBP has been reported to be relieved by shunt surgery.30,31,34 In case series dealing with the surgical management of PBP, large proportions of patients with symptomatic PBP have been reported to be relieved of biliary obstruction with decompression of portal cavernoma; three of seven patients in an earlier series reported from our institution30 and five of 10 patients in another series31 were relieved by shunt surgery alone. In the present series, more than half the patients were satisfactorily relieved of biliary obstruction after the shunt procedure alone.

In the present series, a third of patients undergoing PSRS were not relieved of biliary obstruction by shunt surgery alone. The likely explanation for this is that biliary obstruction in these patients was not caused by the pressure of collaterals on bile ducts alone, and scarring or encasement leading to angulation3 or stricture formation had already occurred. Reported rates of second-stage surgery in other series dealing with the surgical management of symptomatic PBP are 40–50%.30,31

Overall, the results of PSRS in the present series were satisfactory, with no mortality and minimal morbidity. As hepatic function is almost always preserved in EHPVO, PSRS does not usually lead to hepatic decompensation in these patients.35 As well as decompressing the portal cavernoma, a total shunt such as PSRS acts by decompressing the oesophagogastric varices, thereby reducing the risk of variceal haemorrhage36 and hypersplenism.37 Its associated safety, low morbidity and mortality rates and ability to deal with the other problems that arise in EHPVO make PSRS a suitable surgical procedure in this setting.

In the presence of portal cavernoma, a direct surgical approach to the bile ducts is difficult and hazardous, and leads to increased blood loss, morbidity and mortality.26,30,31,38,39 A PSRS decompresses the collaterals in the region and renders biliary surgery safer.30,31 In the present study, average blood loss, duration of surgery and perioperative blood transfusion requirements were low in the 13 patients who underwent biliary surgery in the second stage of treatment, and 10 patients did not require any blood transfusions. In the two patients who underwent biliary surgery without prior shunts, these outcomes were less satisfactory. Thus, even in patients in whom biliary obstruction is not relieved by shunt surgery, the decompression of collaterals makes subsequent access to bile ducts easier and safer. In an earlier surgical series reported from our department, two patients underwent direct biliary surgery without prior shunt procedure. Both these patients had excessive bleeding; one died after surgery and the other developed narrowing of the choledochojejunostomy.30 These problems led us to approach the biliary system with extreme caution in patients in whom prior shunt surgery was not possible, as in the two patients in the present series mentioned above, by meticulously ligating collaterals in the region and placing multiple sutures while opening the duct in order to take care of the intraductal wall collaterals. The latter often contribute significantly to the difficulty and hazards of direct biliary surgery in these patients. Although accessing the left duct for hepaticojejunostomy may not itself be very difficult, excessive bleeding may occur when the duct is opened as a result of intraductal wall collaterals. Therefore, even if one-stage hepaticojejunostomy is technically possible, albeit with greater and potentially higher risk for morbidity, it is not an advocated or preferred option.

Endoscopic management of symptomatic PBP has also been advocated in the literature.24–27,40,41 However, as well as being hazardous to perform in the presence of collaterals,28,29 endoscopic management is not very effective for longterm relief of biliary obstruction. As the predominant mechanism appears to be pressure from enlarged collaterals, procedures such as endoscopic dilatation and stent placement, which do not decompress these collaterals, are unlikely to lead to longterm relief of biliary obstruction. In addition, stents are likely to become blocked, require frequent changes,9 or need to be retained for prolonged periods,42 causing inconvenience and risk to these patients. Incomplete decompression of the biliary system as a result of stent blockages is also possible and may lead to secondary biliary cirrhosis (SBC)9 and recurrent cholangitis. In our series, 14 patients underwent a total of 30 ERC procedures and stent placements prior to being referred for surgical intervention. During the follow-up period after PSRS, endoscopic interventions for various indications were performed in nine patients, but outcomes were successful in only two of these and the main reason for failure was biliary strictures. After shunt surgery, most patients without strictures either did not require endoscopic interventions or, if they did, the chances of success were higher.

Patients with dominant biliary strictures more often required biliary drainage surgery in the second stage. Patients with strictures were significantly older than those without strictures, which indicates that the development of strictures is a relatively later occurrence in PBP. This underlines the importance of early recognition and intervention in symptomatic PBP patients to avoid the formation of strictures and the need for biliary drainage surgery with its attendant morbidity.

Patients with symptomatic PBP have been reported to be older and to have a longer duration of disease than asymptomatic PBP patients.9,12,43 The mean age of patients at presentation in this series was just under 30 years, which is higher than the mean age at presentation of EHPVO patients, who often present with variceal bleeding in first two decades of life.5,6,44 Abnormal LFTs can be present without overt jaundice or cholangitis. Therefore, patients with EHPVO should be evaluated routinely for PBP. The subset of patients with asymptomatic PBP and abnormal LFTs needs to be studied to ascertain whether abnormal LFTs alone should represent an indication for surgery to protect the liver from the effects of prolonged subclinical biliary obstruction.

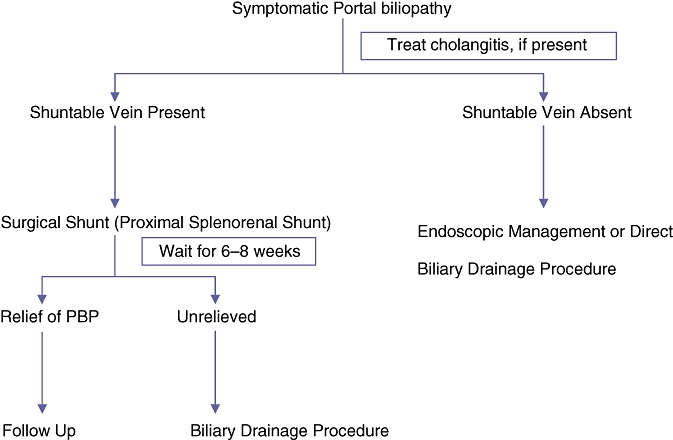

An algorithmic approach to the management of symptomatic PBP patients has been proposed30,31 (Fig. 2). The results of this series lend support to this approach. Patients with symptomatic PBP should undergo PSRS as the first stage of management. In the present study, the optimal time after PSRS for which the patient should be observed for relief of biliopathy symptoms could not be studied because many patients did not comply with the observation period proposed. However, this period should not be overly long in order to avoid the deleterious effects of prolonged biliary obstruction. Patients with biliary strictures are less likely to be relieved of obstructive symptoms with PSRS alone and therefore should expect to undergo second-stage surgery.

Figure 2.

Algorithm for management of symptomatic portal bibliopathy

The effects of asymptomatic PBP on LFTs and the natural history of the condition need to be studied in greater detail.

Conclusions

Symptomatic PBP requires intervention. Surgical decompressive shunt followed by biliary drainage appears to be the treatment of choice in patients with persistent biliary obstruction. Shunt surgery alone relieves biliary obstruction in the majority of patients and facilitates subsequent endoscopic or surgical procedures in the remaining patients.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Dilawari JB, Chawla YK. Pseudosclerosing cholangitis in extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Gut. 1992;33:272–276. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.2.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarin SK, Bhatia V, Makwane U. Portal biliopathy in extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1992;2:A82. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khuroo MS, Yatoo GN, Zargar SA, Javid G, Dar MY, Khan BA, et al. Biliary abnormalities associated with extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Hepatology. 1993;17:807–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra R, Tharakan A, Kapoor D, Sarin SK. Comparative study of portal biliopathy in patients with portal hypertension due to different aetiologies. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1997;15(Suppl 2):A59. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dilawari JB, Chawla YK. Extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Gut. 1988;29:554–555. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.4.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anand CS, Tandon BN, Nundy S. The causes, management and outcome of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in an Indian hospital. Br J Surg. 1983;70:209–211. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800700407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Condat B, Vilgrain V, Asselah T, O'Toole D, Rufat P, Zappa M, et al. Portal cavernoma-associated cholangiopathy: a clinical and MR cholangiography coupled with MR portography imaging study. Hepatology. 2003;37:1302–1308. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malkan GH, Bhatia SJ, Bashir K, Khemani R, Abraham P, Gandhi MS, et al. Cholangiopathy associated with portal hypertension: diagnostic evaluation and clinical implications. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:344–348. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sezgin O, Oguz D, Altintas E, Saritas U, Sahin B. Endoscopic management of biliary obstruction caused by cavernous transformation of the portal vein. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:602–608. doi: 10.1067/s0016-5107(03)01975-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhiman RK, Chawla Y, Duseja A, et al. Portal hypertensive biliopathy (PHB) in patients with extrahepatic portal venous obstruction (EHPVO).][Abstract.] J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:A504. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandra R, Kapoor D, Thakaran A, Chaudhary A, Sarin SK. Portal biliopathy. [Review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:1086–1092. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhiman RK, Behera A, Chawla YK, Dilawari JB, Suri S. Portal hypertensive biliopathy. Gut. 2007;56:1001–1008. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.103606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conn HD, Brodoff M. Emergency oesophagoscopy in the diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage: a critical evaluation of its diagnostic accuracy. Gastroenterology. 1964;47:505–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bismuth H. Postoperative stricture of the bile duct. In: Blumgart LH, editor. The Biliary Tract: Clinical Surgery International. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1982. pp. 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saint OA. The epicholedochal venous plexus and its importance as a mean of identifying the common bile duct during operations on extrahepatic biliary tract. Br J Surg. 1971;46:489–498. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004821104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petren T. Die extrahepatischen Gallenwegsvenen and ihre pathologischanatomische Bedentun. [The veins of extrahepatic biliary system and their pathologic anatomic significance. Verh Anat Ges. 1932;41:139–143. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bayraktar Y, Balkanci F, Ozenc A, Arslan S, Koseoglu T, Ozdemir A, et al. The ‘pseudo-cholangiocarcinoma sign’ in patients with cavernous transformation of the portal vein and its effect on the serum alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:2015–2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dhiman RK, Puri P, Chawla Y, Minz M, Bapuraj JR, Gupta S, et al. Biliary changes in extrahepatic portal venous obstruction: compression by collaterals or ischaemic? Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:646–652. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)80013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bechtelsheimer H, Conrad A. Morphology of cavernous transformation of the portal vein. [Author's translation.] Leber Magen Darm. 1980;10:99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nyman R, al-Suhaibani H, Kagevi I. Portal vein thrombosis mimicking tumour and causing obstructive jaundice. A case report. Acta Radiol. 1996;37:685–687. doi: 10.1177/02841851960373P253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Batts KP. Ischaemic cholangitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:380–385. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63706-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bayraktar Y, Balkanci F, Kayhan B, Ozenc A, Arslan S, Telatar H. Bile duct varices or ‘pseudo-cholangiocarcinoma sign’ in portal hypertension due to cavernous transformation of the portal vein. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;89:1801–1806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagi B, Kochhar R, Bhasin D, Singh K. Cholangiopathy in extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Radiological appearances. Acta Radiol. 2000;41:612–615. doi: 10.1080/028418500127345992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thervet L, Faulques B, Pissas A, Bremondy A, Monges B, Sadducci J, et al. Endoscopic management of obstructive jaundice due to portal cavernoma. Endoscopy. 1993;25:423–425. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1009120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhatia V, Jain AK, Sarin SK. Choledocholithiasis associated with portal biliopathy in patients with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction: management with endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:178–181. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khare R, Sikora SS, Srikanth G, Choudhari G, Sarasvat VA, Kumar A, et al. Extrahepatic portal venous obstruction and obstructive jaundice: approach to management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:56–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercado-Diaz MA, Hinojosa CA, Chan C, Anthon FJ, Podgaetz E, Orozco H. [Portal biliopathy.] Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2004;69:37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tighe M, Jacobson I. Bleeding from bile duct varices: an unexpected hazard during therapeutic ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:250–252. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mutignani M, Shah SK, Bruni A, Perri V, Costamagna G. Endoscopic treatment of extrahepatic bile duct strictures in patients with portal biliopathy carries a high risk of haemobilia: report of three cases. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:587–591. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(02)80093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaudhary A, Dhar P, Sarin SK, Sachdev A, Agarwal AK, Vij JC, et al. Bile duct obstruction due to portal biliopathy in extrahepatic portal hypertension: surgical management. Br J Surg. 1998;85:326–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vibert E, Azoulay D, Aloia T, Pascal G, Veilhan LA, Adam R, et al. Therapeutic strategies in symptomatic portal biliopathy. Ann Surg. 2007;246:97–104. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318070cada. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meredith HC, Vujic I, Schabel SL, O'Brien PH. Obstructive jaundice caused by cavernous transformation of the portal vein. Br J Radiol. 1978;51:1011–1012. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-51-612-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarin SK, Sollano JD, Chawla YK, Amrapurkar D, Hamid S, Hashizume M, et al. Consensus on extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Liver Int. 2006;26:512–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choudhuri G, Tandon RK, Nundy S, Mishra NK. Common bile duct obstruction by portal cavernoma. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:1626–1628. doi: 10.1007/BF01535956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prasad AS, Gupta S, Kohli V, Pande GK, Sahni P, Nundy S. Proximal splenorenal shunts for extrahepatic portal venous obstruction in children. Ann Surg. 1994;219:193–196. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199402000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webb LJ, Sherlock S. The aetiology, presentation and natural history of extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Q Med J. 1979;48:627–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Subhasis RC, Rajiv C, Kumar SA, Kumar AV, Kumar PA. Surgical treatment of massive splenomegaly and severe hypersplenism secondary to extrahepatic portal venous obstruction in children. Surg Today. 2007;37:19–23. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mork H, Weber P, Schmidt H, Goerig RM, Scheurlen M. Cavernous transformation of the portal vein associated with common bile duct strictures: report of two cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:79–83. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hymes JL, Haicken BN, Schein CJ. Varices of the common bile duct as a surgical hazard. Am Surg. 1977;43:686–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solmi L, Rossi A, Conigliaro R, Sassatelli R, Gandolfi L. Endoscopic treatment of a case of obstructive jaundice secondary to portal cavernoma. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;30:202–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lohr JM, Kuchenreuter S, Grebmeier H, Hahn EG, Fleig WE. Compression of the common bile duct due to portal vein thrombosis in polycythemia vera. Hepatology. 1993;17:586–592. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840170410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dumortier J, Vaillant E, Boillot O, Poncet G, Henry L, Scoazec JY, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of biliary obstruction caused by portal cavernoma. Endoscopy. 2003;35:446–450. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-38779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dhiman RK, Chhetri D, Behera A, et al. Management of biliary obstruction in patients with portal hypertensive biliopathy (PHB). [Abstract.] J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:A505. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chawla YK, Dilawari JB, Ramesh GN, Kaur U, Mitra SK, Walia BN. Sclerotherapy in extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Gut. 1990;31:213–216. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]