Abstract

Specific transport systems for penicillins have been recognized, but their in vivo role in the context of other transporters remains unclear. We produced a serum against amoxicillin (anti-AMPC) conjugated to albumin with glutaraldehyde. The antiserum was specific for AMPC and ampicillin (ABPC) but cross-reacted weakly with cephalexin. This enabled us to develop an immunocytochemical (ICC) method for detecting the uptake of AMPC in the rat intestine, liver, and kidney. Three hours after a single oral administration of AMPC, the ICC method revealed that AMPC distributed to a high degree in the microvilli, nuclei, and cytoplasm of the absorptive epithelial cells of the intestine. AMPC distributed in the cytoplasm and nuclei of the hepatocytes in a characteristic granular morphology on the bile capillaries, and in addition, AMPC adsorption was observed on the luminal surface of the capillaries, intercalated portions, and interlobular bile ducts on the bile flow. Almost no AMPC could be detected 6 h postadministration in either the intestine or the liver. Meanwhile, in the kidney, AMPC persisted until 12 h postadministration to a high degree in the proximal tubules, especially in the S3 segment cells in the tubular lumen, in which numerous small bodies that strongly reacted with the antibody were observed. All these sites of AMPC accumulation correspond well to specific sites where certain transporter systems for penicillins occur, suggesting that AMPC is actually and actively absorbed, eliminated, or excreted at these sites, possibly through such certain penicillin transporters.

Amoxicillin (AMPC) is a moderate-spectrum, bacteriolytic, β-lactam antibiotic used to treat bacterial infections caused by susceptible microorganisms, acting by inhibiting the synthesis of the bacterial cell wall. In chemotherapy, the ability of a drug to reach its site of action for a desired duration is dependent on absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, all of which are intimately related to the transport mechanisms in the barrier epithelia (56). Actually, pharmacotherapeutic efficacy and toxicity are governed in vivo by a multitude of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic factors. Recently, a variety of transporters for penicillins have been demonstrated at the molecular level, especially in the kidney and liver, in which numerous potentially toxic xenobiotics and drugs are eliminated (23). It has been postulated that the following may be involved in the transport of penicillins: in the small intestine, the proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter PEPT1 (1); in the liver, the organic anion transporter (OAT) (5, 22, 44, 54), multidrug resistance-associated protein (Mrp2) (6, 26, 39, 42), and sodium-dependent phosphate transport protein (NPT1) (8, 21, 57); and in the kidney, the rat multispecific organic anion transporter 1 (rOAT1), rOAT2, and rOAT3 (2, 22, 23, 51, 55), Mrp2 (43), and H+/peptide cotransporters (PEPT1 and PEPT2) (23-25, 38, 45, 49, 53), etc. The interaction of such transporters with β-lactam antibiotics has been studied extensively in vitro (10, 23, 25). However, the in vivo role of transporters in drug disposition, in the context of other transporters, glomerular filtration, and metabolism, has not been established. Thus, knowledge of the time sequence of the distribution of penicillins in cells and tissues of animals may help develop a better understanding of the actual overall pharmacokinetics of the drugs. Also, it should be valuable for developing drug therapy for infections caused by intracellular parasites, including Staphylococcus aureus, since it is known that they invade host cells, grow, and evade the bactericidal potential of antimicrobial agents (33, 35, 41). Recently, we have successfully developed immunocytochemical (ICC) procedures for detecting cellular uptake of other water-diffusible small drugs, such as daunomycin (DM) (16, 17, 36, 37, 46, 47) and gentamicin (GM) (18). These procedures make use of glutaraldehyde (GA)-fixed tissues which undergo a series of pretreatments to unmask the sites of accumulation of the drug.

We now report on the preparation and characterization of anti-AMPC serum and the development of an ICC method for the uptake of AMPC in the liver and kidneys as well as in the intestine of rats orally administered the drug. The new information obtained by this method is that AMPC accumulated to a high degree in the microvilli of the bile capillaries of the hepatocytes, in the cells of the S3 segment of the proximal tubules in the kidney, and also in the absorptive cells of the intestine, as well as in their brush border membrane. These results, as far as we know, are the first to show that these sites of AMPC accumulation are closely correlated with the specific sites in which certain transporter systems for penicillin occur.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

AMPC, ampicillin trihydrate (ABPC), sodium borohydride, and protease (type XXIV, bacterial) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. Inc. (St. Louis, MO). GA (25% in water) and Triton X-100 were obtained from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). All other chemicals or solvents were reagent grade or chemically pure.

Preparation of immunogen (AMPC-GA-BSA conjugate).

AMPC-GA-bovine serum albumin (BSA) conjugate was prepared according to our previous method for protein conjugate of polyamine spermine or putrescine, using GA as a homobifunctional agent (13, 15). Briefly, 25 mg (60 μmol) of AMPC in 1.5 ml of 100 mM borate buffer, pH 10, was incubated with 1 ml 100 mM GA for 1 min with stirring. To this reaction mixture was added 10 mg carrier protein BSA in 1.0 ml 500 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, and the entire mixture was incubated for 1 h with slow stirring at room temperature (RT). Then, 5 mg solid sodium borohydride was added so that the double bonds were saturated. The conjugate mixture was applied to a Sephadex G-100 column (2 cm by 35 cm) equilibrated with 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and was eluted with the same buffer. The eluate, monitored at 280 nm, was collected in 3.5-ml fractions, and the peak fraction was used for immunization.

The conjugate of AMPC-GA was prepared in a manner similar to that for the conjugate of AMPC-GA-BSA, but the carrier protein (BSA) was omitted (14). The reaction mixture was directly used as a conjugate without any further purification for the inhibition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) described below (14).

Antiserum.

The chromatographically purified AMPC-GA-BSA was used for production of anti-AMPC serum in three 5-week-old, female BALB/c mice. The mice intraperitoneally (i.p.) received 0.1 mg of the conjugate, emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant (Difco, Tokyo, Japan). This was followed by biweekly booster injections of 50 μg of the conjugate, which were repeated three times. Seven days later, the mice were killed and sera were separated by centrifugation, heated at 55°C for 30 min, and stored at −30°C.

Dilution ELISAs.

Dilution ELISAs were performed similarly to our previously described method for antispermine monoclonal antibodies (13). Wells in microtiter plates (Immunoplate I; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with the AMPC-GA-BSA (10 μg/ml) and then incubated overnight at 4°C with dilutions of anti-AMPC serum, followed by goat anti-mouse IgG labeled with horseradish peroxidase (HRP; diluted 1:2,000) for 1 h at 25°C. The amount of enzyme conjugate bound to each well was measured using o-phenylenediamine (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) as a substrate, and the absorbance at 492 nm was read with an automatic ELISA analyzer (ImmunoMini NJ-2300; Nalje Nunc International Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Inhibition ELISAs.

Wells in a microtiter plate were coated with 100 μl of the AMPC-GA-BSA conjugate (10 μg/ml) as described above. The wells were then incubated with 25 μl of a fixed concentration of antiserum (1:2,500) and 25 μl of different analytes (AMPC-GA-BSA, AMPC-GA, AMPC, or ABPC) at various concentrations overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with goat anti-mouse IgG labeled with HRP (1:2,000) for 1 h at RT. The activity of the bound HRP was measured as described above (12, 13).

Binding ELISAs (antibody specificity).

According to our previous method (13), the wells in a microtiter plate coated with poly-l-lysine (30 μg/ml) were activated with 2.5% GA in 50 mM borate buffer, pH 10.0, for 1 h. The wells were subsequently incubated with test compounds at various concentrations for 1 h at RT. Excess aldehyde groups were blocked with 0.5% sodium borohydride. The wells were further incubated for 1 h with 1% skim milk to block nonspecific protein binding sites, and then the plates were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary anti-AMPC serum at 1:4,000 diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST). The wells were then incubated for 1 h with HRP-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (diluted 1:2,000). The bound enzyme activity was measured described above.

Animals.

Healthy adult male Wistar rats (body weight, 200 to 250 g; Kyudo Experimental Animals, Kumamoto, Japan) were used in this study. The principles of laboratory animal care and specific national laws were observed. The animals were housed in temperature- and light-controlled rooms (21 ± 1°C with 12 h of light and 12 h of dark) and had free access to standard food and tap water. AMPC was given orally to the rats in a single dose of 15 or 60 mg/kg of body weight. For the next perfusion experiments, the rats were divided into four groups of three rats each 3, 6, 12, and 24 h after the drug administration. Three rats receiving saline administration were used for control purposes. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Committee for Animal Experimentation of Sojo University.

ICC method.

The ICC method was carried out essentially according to our previous methods (16-18). While they were under sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) anesthesia, the rats were perfused intracardially with PBS at 50 ml/min for 2 min at RT and then with a freshly prepared solution of 2% GA in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, for 6 min. Kidney, liver, and intestine (the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum were taken separately) were quickly excised and postfixed in the same fixative overnight at 4°C and were subsequently embedded in paraffin in a routine way. The samples were cut into 5-μm-thick sections, acidified with 1 N HCl for 30 min (in order to denature the DNA), digested with 0.001% to 0.006% protease (type XXIV, bacterial; Sigma-Aldrich) in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.86% NaCl (Tris-buffered saline [TBS]) for different periods (15 min to 2 h) at 30°C (in order to facilitate the penetration of antibody in order to fully detect uptake of AMPC in different cells and subcellular compartments), and reduced with 1.0% NaBH4 in TBS for 10 min (to prevent unspecific staining by reducing free aldehyde groups of GA bound in tissues). During each process of the treatment, the specimens were washed three times with TBS. Next, the specimens were blocked with a protein solution containing 10% normal goat serum, 1.0% BSA, and 0.1% saponin in TBS for 1 h at RT and were then directly incubated at 4°C overnight with anti-AMPC serum diluted 1:2,000 to 1:10,000 in TBS supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100 (TBST). The sections were washed with TBST three times for 5 min each time and then incubated with HRP-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (whole IgG; Cappel, West Chester, PA) at 1:500 for 2 h at 4°C. After the sections were rinsed with TBS, the site of the antigen-antibody reaction was revealed for 10 min with diaminobenzidine (DAB) and H2O2 (20).

Controls for the immunocytochemical method included conventional staining (second-level) controls as well as anti-gentamicin serum (18). Absorption controls used conjugates of AMPC-GA-BSA and AMPC-GA at concentrations ranging from 2 to 100 μg/ml and the free compounds AMPC, ABPC, and kanamycin at concentrations ranging between 2 and 50 μg/ml.

RESULTS

Antibody dilution.

The serum produced against GA-conjugated AMPC (AMPC-GA-BSA conjugate) was characterized by an ELISA system employing GA-conjugated AMPC as the solid-phase antigen. As shown in Fig. 1, significant binding activity was observed at serial dilutions of anti-AMPC serum, even at a dilution of more than 30,000 times. On the other hand, a much lower level of immunoreactivity was seen in an ELISA system using the solid-phase antigen of BSA itself at the same concentration (10 μg/ml) (Fig. 1), thus showing the binding activity of the antibody produced against the carrier of the AMPC-GA-BSA conjugate used as the AMPC antigen. Thus, AMPC immunoreactivity was indicated as the remainder of the binding activity (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

ELISA measurements of the binding of serially diluted anti-AMPC serum to AMPC-GA-BSA (closed circles) or BSA (open squares).

Antibody specificity by inhibition ELISA.

Inhibition ELISA was done using an ELISA system with AMPC-GA-BSA conjugate as the antigen. The principle was competition between AMPC, ABPC, AMPC-GA, or AMPC-GA-BSA (free in solution) and a fixed amount of AMPC coated on ELISA plates. Calibration curves showing the relationship between the concentrations of the analytes and the percentage of bound anti-AMPC antibody were plotted, giving dose-dependent inhibition curves with AMPC-GA-BSA and AMPC-GA (Fig. 2). The doses required for 50% inhibition of binding (50% effective concentrations [EC50s]) were 10 nM with AMPC-GA-BSA and 300 μM with AMPC-GA. No inhibition occurred with AMPC itself or ABPC (Fig. 2) or with the nonrelated antibiotics gentamicin, streptomycin, and kanamycin even at concentrations up to 1 mM (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

ELISA measurements showing competition between free and conjugated AMPC and AMPC-GA-BSA coated to solid phase for binding to anti-AMPC serum. The curves show the amount (percentage) of bound enzyme activity (B) for various doses of AMPC-GA-BSA (closed circles), AMPC-GA (closed squares), amoxicillin (closed diamonds), or ampicillin (closed triangles) as a ratio of that bound using the HRP-labeled second antibody alone (B0). The concentrations of AMPC-GA-BSA and AMPC-GA were calculated by assuming that one molecule of AMPC was incorporated into a BSA molecule and that AMPC, which was used for conjugation with GA, completely reacted, respectively (18).

Antibody specificity by binding ELISA.

The binding ELISA simulates the ICC of tissue sections, on the basis of the principle of coupling of the amino group of the analytes to the wells of a microtiter plate activated with poly-l-lysine and GA and incubation of the wells by the indirect immunoperoxidase method (13). As shown in Fig. 3, analysis of the relationship between the concentration of each of the analytes applied to the wells and the bound HRP activity produced a dose-dependent curve, with AMPC and ABPC concentrations ranging from 30 μM to 500 μM. The extents of the immunoreaction were 100% with AMPC, 95% with ABPC, and 13% with cephalexin at 500 μM. No immunoreaction with bacampicillin, cefaclor, cefminox, kanamycin, gentamicin, or bestatin occurred (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Reactivity of anti-AMPC-serum determined from its immunoreactivity in the binding ELISA. Activated wells prepared for the binding ELISA were incubated with various concentrations of amoxicillin (closed circles), ampicillin (open squares), cephalexin (closed triangles), or kanamycin (closed squares). The wells were reacted with NaBH4 and then with anti-AMPC-serum (1:4,000), followed by HRP-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (whole; 1:2,000). Note that anti-AMPC-serum is almost equally immunoreactive with amoxicillin and ampicillin.

AMPC uptake in rat intestine.

Three hours after administration of a single oral dose of AMPC (15 or 60 mg/kg), the ICC method with a 1-h predigestion of jejunum sections with protease (0.001%) revealed strong staining of AMPC in the brush borders of villi of the absorptive epithelial cells, in which the cytoplasm, as well as the nuclei, also strongly reacted with the antibody (Fig. 4a and b). The intensity of staining became weak in the gradient to the bottom of the villus cells. Also, only very faint staining occurred in, probably, smooth muscle cells in the lamina propria mucosae. However, almost no staining was detected in goblet cells or crypt cells (Fig. 4a and b). The staining pattern in the duodenum was similar to that in the jejunum, but the staining was weaker in villus cells, in which, however, their brush border membrane strongly reacted with the antibody (Fig. 4c). At 6 h postadministration, no staining occurred in any of the cell types of the intestine (data not shown). The absorption controls for anti-AMPC serum showed that addition of AMPC-GA-BSA at a concentration of 30 μg/ml to the antiserum abolished all staining (Fig. 4d). All conventional immunocytochemical staining (second-level) controls were negative. In the control rats receiving an oral administration of 0.9% NaCl solution, no immunoreaction could be detected in the liver (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Immunostaining for AMPC in small intestine of rats administered AMPC. Rats were orally administered AMPC at 60 mg/kg and then killed 3 h later. The AMPC ICC method was carried out following digestion of sections with protease at 0.001% at 30°C for 1 h. (a) Jejunum (lower magnification). Strong staining occurred exclusively in the absorptive epithelial cells and not in the goblet cells (arrowheads), in the crypt cells, or in other cell types of the intestine. (b) Jejunum (higher magnification). Strong staining occurred in the microvilli (arrows), in the cytoplasm, and in the nuclei (open arrowheads) of the absorptive epithelial cells but not in the goblet cells (closed arrowheads). Very weak staining occurred in unidentified cells in the lamina propria mucosae. (c) Duodenum (lower magnification). Staining was pronounced in the microvilli (arrows) of the absorptive cells, in which intracellular staining, however, was very weak, with the exception that the top villus cells (arrowheads) were strongly stained. (d) Duodenum (lower magnification). The staining was completely abolished by absorption of the anti-AMPC serum with AMPC-GA-BSA (30 μg/ml). Bars = 100 μm (a and d) and 20 μm (b and c).

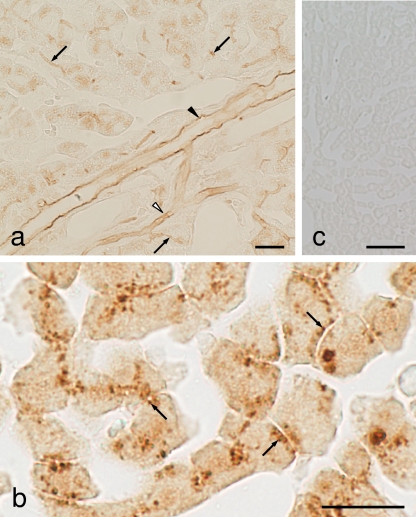

AMPC uptake in rat liver.

In liver specimens at 3 h postadministration, the omission of the protease digestion step in the ICC protocol produced weak immunostaining of AMPC in the cytoplasm of the hepatocytes and moderate staining in the luminal surface of the bile capillaries, intercalated portions, and interlobular bile ducts (Fig. 5a). However, sections that had been digested with 0.004% protease for 2 h at 30°C produced very strong staining in the cytoplasmic small granules lining the bile capillaries of the hepatocytes (Fig. 5b). Also, very weak staining occurred in the nuclei of the hepatocytes. However, 6 h after administration, no staining was observed in any of the cell types of the liver under widely various protease digestion conditions (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Immunostaining for AMPC in liver of rats administered AMPC. (a) Lower magnification. The ICC method without the protease digestion step in the protocol showed that staining occurred in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes and in the luminal surface of the bile capillaries (arrows), intercalated portion (open arrowheads), and interlobular bile ducts (closed arrowheads). (b) Higher magnification. Sections were digested with 0.006% protease for 2 h prior to immunoreaction. Note the strong staining in the small spots (arrows) lining the bile capillaries. (c) Staining was completely abolished by absorption of the anti-AMPC serum with AMPC-GA-BSA (30 μg/ml). Bars = 20 μm (a and b) and 50 μm (c).

AMPC uptake in rat kidney.

In the kidney specimens collected 3 h after a single oral administration of AMPC (60 mg/kg), omission of the protease digestion in the ICC method produced wide ranges of staining in cells of the S3 segment (the medullary straight segment) of the proximal tubules, as well as in their microvilli (Fig. 6a). Also, strong staining was observed in the nuclei and in the cytoplasm of some cells of the collecting ducts, and moderate staining was observed in the nuclei and cytoplasm of some cells of the distal tubules (Fig. 6b). In both cell types, some of the heavily stained cells were swollen (Fig. 6b). With 30 min to 1 h of predigestion with protease at 0.006%, the strongest staining, but with wide ranges of staining intensity, was detected in both the nuclei and whole cytoplasm of the S3 segment cells, whereas their microvilli, which had already lost their staining during the protease digestion, were somewhat disrupted and peeled off (Fig. 6c). Many strongly stained round small bodies occurred in the tubular lumen of the S3 segment tubules, and some of the round small bodies adhered to the apical cytoplasm of the tubular cells (Fig. 6c). Under conditions of predigestion for less than 1 h, cells of the S1 and S2 segments (the straight proximal segments located in the cortex) were not stained. However, when the protease digestion was prolonged to 2 h, the cytoplasmic staining of AMPC occurred in the cells of both segments (Fig. 6d and e and 7a). The staining was most pronounced in the small granules, which varied widely in size (Fig. 6e). The small granules occurred at the bottoms of the brush border and often formed in a line encircling the tubule (Fig. 6d), whereas very slightly stained microvilli were somewhat disrupted and peeled off (Fig. 6d and e). Also, strong staining persisted in some of the collecting duct cells, including swollen cells (Fig. 6f). Very similar patterns of AMPC staining were observed in the kidney specimens collected 6 and 12 h after AMPC administration, but at 24 h postadministration, staining completely vanished in all the cell types of the kidney, except for weak staining remaining in the cells of the S3 segment portion of the proximal tubules (Fig. 7c).

FIG. 6.

Immunostaining for AMPC in the kidneys of rats administered AMPC. Rats were orally administered AMPC at 15 mg/kg (g) or 60 mg/kg (a to f and h) and then killed 3 h later (a to h). The AMPC ICC method was carried out without protease digestion (a, b, and g) or following digestion of sections with protease at 0.006% at 30°C for 1 h (c, f, and h) or 2 h (d and e). (a) Wide ranges of immunostaining of AMPC occur in the nuclei, in the cytoplasm, and in the microvilli of the S3 segment cells of the proximal tubules (S3). Also, strong staining was observed in some, but not all, cells of the collecting duct cells (C). The S3 segment was identifiable by the presence of periodic acid-Schiff-positive brush borders. (b) Staining occurred moderately in some, but not all, cells of the distal convolution tubules (D) and strongly in some cells of the collecting duct cells (C). Note that some of heavily stained cells are swollen (arrows) and that adjacent cells are virtually unstained (arrowheads). G, glomeruli. (c) Many small bodies (open arrowheads) heavily stained with antibody occurred in the tubular lumens of the S3 segment. (d) The cytoplasm and the microvilli of the S1 and S2 segment cells (S1,2) were weakly stained, although the microvilli were somewhat disrupted and peeled off. Note the staining in small granules (arrowheads), which were located at the bottom of the microvilli of the S1 and S2 segment cells and which formed in a line encircling the tubule. (e) Moderately stained granules of various sizes (arrowheads) and very weakly stained microvilli (arrows). (f) A swollen cell strongly reacted with the antibody in the collecting duct cells in the medulla of the kidney. (g) Some of the convolution distal tubule cells were weakly stained. (h) The staining was completely abolished by absorption of the anti-AMPC serum with AMPC-GA-BSA (30 μg/ml). Bars = 20 μm (a, c, and d to h) and 50 μm (b).

FIG. 7.

Immunostaining for AMPC in the kidneys of rats administered AMPC. Rats were orally administered AMPC at 60 mg/kg (a and c) or 15 mg/kg (b) and then killed 3 h (a and b) or 24 h (c) later. The AMPC ICC method was carried out following digestion of sections with protease at 0.006% at 30°C for 1 h (b) or 2 h (a and c). (a to c) Renal cortex (lower magnification). (a and b) The staining pattern was characteristic of the fact that strong staining occurred extensively in the S3 segment cells of the proximal tubules. In addition, strong staining occurred intermittently in the cells of the collecting ducts. The staining intensity in the collecting duct cells was much weaker in panel b than in panel a. (c) Except for weak staining in the S3 segment cells, almost no staining of the proximal tubules occurred. G, glomeruli; C, collecting ducts. Bars = 100 μm.

Similar ICC studies in which AMPC was administered at 15 mg/kg (in which the total dose per day almost matched the dose used for human chemotherapy) produced virtually the same staining pattern of uptake of AMPC in all the cell types in the kidney, as described above (Fig. 6g and 7b). However, the intensity of the staining was not as strong, and fewer swollen cells seemed to appear in both the distal tubules and the collecting ducts (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

AMPC is a form of ABPC that is absorbed to a higher degree than plain ABPC when it is administered orally. AMPC is not substantially metabolized, as 60 to 75% is excreted unchanged in urine, but some AMPC is metabolized to amoxicilloic acid and amoxicillin diketopiperazine-2′,5′-dione (40). In the last decade, numerous studies concerning either the uptake or the elimination of β-lactam antibiotics have been undertaken using as models in vitro-isolated hepatocytes, Xenopus oocytes, and renal cell lines expressing carrier-mediated transporters (10, 23, 50). However, no studies of the distribution of drugs in animal tissues are available. In the study described in this paper, we have now prepared anti-AMPC serum, characterized for its specificity, and developed an ICC procedure for determining the sites of AMPC accumulation in the rat small intestine, liver, and kidney, which represent the main organs responsible for drug absorption and elimination.

Serum against a GA-conjugated AMPC was prepared and was demonstrated to be specific for AMPC and ABPC but very slightly specific for cephalexin. Inhibition ELISA showed that antibody binding to the solid-phase antigen was inhibited strongly with AMPC-GA-BSA, weakly with AMPC-GA, and not at all with AMPC itself or ABPC. This finding suggests that the antibody recognizes not only the AMPC molecule but also, in part, the carrier protein conjugation site(s) of GA. In accordance with the findings of our recent studies (18), the tissues of rats orally administered AMPC were fixed with 2% GA by perfusion in order to immobilize the antigen in the tissue as rapidly as possible. Also, following systematic testing of several pretreatments aimed at demasking the immunoreactivity of AMPC in fixed tissues and reducing background staining, we succeeded in specifically localizing AMPC in the livers, kidneys, and intestine of rats injected with the drug.

The H+/peptide cotransporter PEPT1, which occurs exclusively in the small intestine, is especially enriched in the microvilli of the absorptive epithelial cells and is responsible for mucosal cell transport of many peptide-like drugs, such as β-lactam antibiotics (9, 29, 45, 58). The ICC method used in the present study demonstrated that at 3 h postadministration, large amounts of AMPC distributed in the microvilli, as well as in the whole cell of the absorptive epithelial cells in the jejunum. This is the first study to show that AMPC is extensively and actively absorbed by the villus cells through their microvilli, thus strongly suggesting that the PEPT1 transporter actually mediates absorption of AMPC at those sites. Also, AMPC is transported in a mode of transcellular transport rather than paracellular transport.

Most β-lactams are eliminated into the urine; however, some derivatives are exclusively excreted into the bile (3, 28, 34, 57). The ICC method revealed that in the liver at 3 h postadministration, AMPC distributed in the cytoplasm and nuclei of hepatocytes in a characteristic granular morphology probably on the bile capillaries. In addition, AMPC adsorption was observed on the luminal surface of the capillaries, intercalated portions, and interlobular bile ducts on the bile flow. Intracellular AMPC concentrations may reflect the concerted function of AMPC cellular influx and efflux and may also reflect AMPC metabolism. Recently, many transport systems for β-lactams have been recognized in healthy tissues active in absorption, excretion, and transport (10, 19, 27, 30, 52). Among such systems, OAT systems at the sinusoidal plasma membrane of hepatocytes may mediate the uptake of the drugs from the blood (5, 22, 44, 54), and the multidrug resistance-associated protein Mrp2, highly expressed on the bile canalicular membrane of the cells, may mediate excretion of the drugs into the bile (6, 26, 39, 42). Also, sodium-dependent phosphate transport protein (NPT1) may participate in hepatic sinusoidal membrane transport of AMPC for efflux in the hepatocyte-to-blood direction (8, 21, 57). Therefore, the ICC method suggests that Mrp2 significantly functions in situ as a transporter of AMPC in the microvilli of the bile canaliculi and actively excretes AMPC to the bile. This seems to be very consistent with the findings of studies showing that β-lactams interact with Mrp2, acting as substrates and/or stimulators (7, 26). The elimination rate might be so fast that the ICC method could not detect any AMPC in any of the cell types of the liver collected 6 h after administration.

β-Lactams are known to undergo both secretion and reabsorption in renal tubules (25). The ICC method showed that the distribution pattern of AMPC was characteristic of the fact that most of the AMPC extensively accumulated in the proximal tubules, especially in the S3 segment cells. The nuclei, cytoplasm, and microvilli of the S3 segment cells, however, contained a wide range of concentrations of AMPC. Meanwhile, small amounts of AMPC accumulated in segments S1 and S2, in both of which the cytoplasmic small granules had the characteristic of forming in a line directly at the bottoms of the microvilli, suggesting that they correspond to the vacuoles, known to be involved in intracellular protein digestion (11). AMPC disappeared by 24 h postadministration, so that almost none of the drug could be detected in any of the cell types of the kidney; the exception was small amounts of AMPC still persisting in the S3 segment cells. Among transporters in the kidney, cellular uptake of organic anions across basolateral membranes may be mediated by OAT1, which is an organic anion/dicarboxylate exchanger, and by OAT2 and OAT3 (2, 22, 23, 51, 55). Also, the reabsorption of the antibiotics from the glomerular filtrate may be mediated by H+/peptide cotransporters PEPT1 and PEPT2, localized at the microvilli of the S1 and S3 segments, respectively, of proximal tubular cells. In particular, PEPT2 is abundantly expressed in the kidney, with minor contributions coming from PEPT1 (24, 31, 45, 48). Although the molecular mechanism for the process of organic anion excretion has not been identified, except for that of Mrp2 (43), which is expressed on the microvilli of the S1, S2, and S3 segments of the proximal epithelia, several candidate transporters of β-lactams are available, including, rOAT-P1, rOAT-K1, and rOAT-K2 (5, 23). Thus, the results of the present ICC method suggest that among these transporters, PEPT2 especially contributes most significantly to the distribution of AMPC in the S3 segment. Actually, it has previously been reported that PEPT2 influences the pharmacokinetic profiles and therapeutic efficacy of penicillins (23-25, 38, 45, 49, 53). Furthermore, of note was the finding that numerous round small bodies containing AMPC occurred in the tubular lumen of the S3 segment. However, their original form is unclear, and the origin of these small bodies and how they are correlated with the drug elimination are now under investigation.

In general, AMPC is safe for clinical use. However, we observed swollen cells, in which the nuclei and cytoplasm were heavily immunostained. Interestingly, such cells occurred in both the distal tubules and collecting ducts early, within 3 h after AMPC administration, while they were no longer detected in specimens collected 24 h postadministration, thus suggesting that AMPC might transiently react with some cells of both cell types. Moreover, the ICC method detected striking differences between the abilities of neighboring cells to take up and/or retain AMPC in the distal convoluted tubules as well as in collecting ducts, as was observed in GM uptake studies performed by the use of autoradiography (4) and by our ICC method (18). This suggests that physiological differences exist among these cells. In fact, both the connecting segment and the collecting duct are composed of two distinct cell types: the principal cell and the intercalated cell (32).

In conclusion, our study clearly demonstrates that the serum produced against GA-conjugated AMPC was useful for developing an ICC method for AMPC. This method revealed that the sites of AMPC accumulation might be closely correlated with ones where certain transport systems for penicillins occur in the cells of the rat intestine, liver, and kidney. Thus, this method would be useful for elucidating the in vivo role of transporters in drug disposition, in the context of other transporters, metabolism, etc., especially using penicillin transporter-deficient transgenic animals.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. Yagisawa for valuable suggestions and to D. Taniguchi, Y. Takada, Y. Tanaka, K. Moriyama, Y. J. Shin, and T. Fujita for their technical assistance throughout this study.

This study was supported in part by a grant (grant 15590148) from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 October 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adibi, S. A. 2003. Regulation of expression of the intestinal oligopeptide transporter (Pept-1) in health and disease. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 285:G779-G788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apiwattanakul, N., T. Sekine, A. Chairoungdua, Y. Kanai, N. Nakajima, S. Sophasan, and H. Endou. 1999. Transport properties of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs by organic anion transporter 1 expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 55:847-854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barza, N., J. Brush, N. C. Bergeron, O. Kemmotsu, and L. Weinstein. 1975. Extraction of antibiotics from the circulation by liver and kidney: effect of probenecid. J. Infect. Dis. 131:S86-S97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergeron, M. G., Y. Marois, C. Kuehn, and F. J. Silverblatt. 1987. Autoradiographic study of tobramycin uptake by proximal and distal tubules of normal and pyelonephritic rats. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 31:1359-1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergwerk, A. J., K. Shi, A. C. Ford, N. Kanai, E. Jacquemin, R. D. Burk, S. Bai, P. R. Novikoff, B. Stieger, P. J. Meier, V. L. Schuster, and A. W. Wolkoff. 1996. Immunologic distribution of an organic anion transport protein in rat liver and kidney. Am. J. Physiol. 271:G231-G238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodo, A., E. Bakos, F. Szeri, A. Varadi, and B. Sarkadi. 2003. Differential modulation of the human liver conjugate transporters MRP2 and MRP3 by bile acids and organic anions. J. Biol. Chem. 278:23529-23537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi, M. K., H. Kim, Y. H. Han, I. S. Song, and C. K. Shim. 2009. Involvement of Mrp2/MRP2 in the species different excretion route of benzylpenicillin between rat and human. Xenobiotica 39:171-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chong, S. S., C. A. Kozak, L. Liu, K. Kristjansson, S. T. Dunn, J. E. Bourdeau, and M. R. Hughes. 1995. Cloning, genetic mapping, and expression analysis of a mouse renal sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporter. Am. J. Physiol. 268:F1038-F1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dantzig, A. H., and L. Bergin. 1988. Carrier-mediated uptake of cephalexin in human intestinal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 155:1082-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobson, P. D., and D. B. Kell. 2008. Carrier-mediated cellular uptake of pharmaceutical drugs: an exception or the rule? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7:205-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fawcett, D. W. 1986. The urinary system, p. 755-795. Bloom and Fawcett—a textbook of histology, 11th ed. Saunders international edition. Igaku-Shoin, Tokyo, Japan.

- 12.Fujiwara, K., T. Saita, N. Takenawa, N. Matsumoto, and T. Kitagawa. 1988. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for actinomycin D using β-d-galactosidase as a label. Cancer Res. 48:915-920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujiwara, K., and Y. Masuyama. 1995. Monoclonal antibody against the glutaraldehyde-conjugated polyamine, spermine. Histochem. Cell Biol. 104:309-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujiwara, K., I. Murata, S. Yagisawa, T. Tanabe, M. Yabuuchi, R. Sakakibara, and D. Tsuru. 1999. Glutaraldehyde (GA)-hapten adducts, but without a carrier protein, for use in a specificity study on an antibody against a GA-conjugated hapten compound: histamine monoclonal antibody (AHA-2) as a model. J. Biochem. 126:1170-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujiwara, K., T. Tanabe, M. Yabuuchi, R. Ueoka, and D. Tsuru. 2001. A monoclonal antibody against the glutaraldehyde-conjugated polyamine, putrescine: application to immunocytochemistry. Histochem. Cell Biol. 115:471-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujiwara, K., H. Takatsu, and K. Tsukamoto. 2005. Immunocytochemistry for drugs containing an aliphatic primary amino group in the molecule, anticancer antibiotic daunomycin as a model. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 53:467-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujiwara, K., M. Shin, D. M. Hougaard, and L.-I. Larsson. 2007. Distribution of anticancer antibiotic daunomycin in the rat heart and kidney revealed by immunocytochemistry using monoclonal antibodies. Histochem. Cell Biol. 127:69-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujiwara, K., M. Shin, H. Matsunaga, T. Saita, and L.-I. Larsson. 2009. Light-microscopic immunocytochemistry for gentamicin and its use for studying uptake of the drug in kidney. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3302-3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerk, P. M., and M. Vore. 2002. Regulation of expression of the multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2) and its role in drug disposition. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 302:407-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham, R. C., and N. J. Karnovsky. 1966. The early stages of absorption of injected horseradish peroxidase in the proximal tubules of mouse kidney. Ultrastructural cytochemistry by a new technique. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 14:291-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagenbuch, B., B. Stieger, M. Foguet, H. Lübbert, and P. J. Meier. 1991. Functional expression cloning and characterization of the hepatocyte Na+/bile acid cotransport system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:10629-10633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasegawa, M., H. Kusuhara, D. Sugiyama, K. Ito, S. Ueda, H. Endou, and Y. Sugiyama. 2002. Functional involvement of rat organic anion transporter 3 (rOat3; Slc22a8) in the renal uptake of organic anions. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 300:746-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inui, K., S. Masuda, and H. Saito. 2000. Cellular and molecular aspects of drug transport in the kidney. Kidney Int. 58:944-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inui, K., T. Okano, M. Takano, H. Saito, and R. Hori. 1984. Carrier-mediated transport of cephalexin via the dipeptide transport system in rat renal brush-border membrane vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 769:449-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inui, K., and T. Terada. 1999. Dipeptide transporters, p. 269-288. In G. Amidon and W. Sadee (ed.), Membrane transporters as drug targets. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, NY.

- 26.Ito, K., T. Koresawa, K. Nakano, and T. Horie. 2004. Mrp2 is involved in benzylpenicillin-induced choleresis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 287:G42-G49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katsura, T., and K. Inui. 2003. Intestinal absorption of drugs mediated by drug transporters: mechanisms and regulation. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 18:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kind, A. C., T. E. Tupasi, H. C. Standiford, and W. M. M. Kirby. 1970. Mechanisms responsible for plasma levels of nafcillin lower than oxacillin. Arch. Intern. Med. 125:685-690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kramer, W., F. Girbig, U. Gutjahr, H. W. Kleeman, I. Leipe, H. Urbach, and A. Wagner. 1990. Interaction of rennin inhibitors with the intestinal uptake system for oligopeptides and β-lactam antibiotics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1027:25-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kusuhara, H., and Y. Sugiyama. 2009. In vitro-in vivo extrapolation of transporter-mediated clearance in the liver and kidney. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2009:37-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leibach, F. H., and V. Ganapathy. 1996. Peptide transporters in the intestine and the kidney. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 16:99-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madsen, K. M., and C. C. Tisher. 1986. Structural-functional relationship along the distal nephron. Am. J. Physiol. 250:F1-F15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin, J. R., P. Johnson, and M. F. Miller. 1985. Uptake, accumulation, and egress of erythromycin by tissue culture cells of human origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 27:314-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsui, H., K. Yano, and T. Okuda. 1982. Pharmacokinetics of the cephalosporin SM 1652 in mice, rats, rabbits, dogs and rhesus monkeys. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:213-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noumi, T., N. Nishida, S. Minami, Y. Watanabe, and T. Yasuda. 1990. Intracellular activity of tosufloxacin (T-3262) against Salmonella enteritidis and ability to penetrate into tissue culture cells of human origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:949-953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohara, K., M. Shin, L.-I. Larsson, and K. Fujiwara. 2007. Improved immunocytochemical detection of daunomycin. Histochem. Cell Biol. 127:603-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohara, K., M. Shin, H. Nakamuta, L.-I. Larsson, D. H. Hougaard, and K. Fujiwara. 2007. Immunocytochemical studies on the distribution pattern of daunomycin in rat gastrointestinal tract. Histochem. Cell Biol. 128:285-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okano, T., K. Inui, H. Maegawa, M. Takano, and R. Hori. 1986. H+ coupled uphill transport of aminocephalosporins via the dipeptide transport system in rabbit intestinal brush-border membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 261:14130-14134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paulusma, C. C., M. A. Van Geer, R. Evers, M. Heijn, R. Ottenhoff, P. Borst, and R. P. Oude Elferink. 1999. Canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter/multidrug resistance protein 2 mediates low-affinity transport of reduced glutathione. Biochem. J. 338(Pt 2):393-401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reyns, T., M. Cherlet, S. De Baere, P. De Backer, and S. Croubels. 2008. Rapid method for the quantification of amoxicillin and its major metabolites in pig tissues by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry with emphasis on stability issues. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 861:108-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchez, M. S., C. W. Ford, and R. J. Yancey, Jr. 1986. Evaluation of antibacterial agents in a high-volume bovine polymorphonuclear neutrophil Staphylococcus aureus intracellular killing assay. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 29:634-638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sathirakul, K., H. Suzuki, K. Yasuda, M. Hanano, O. Tagaya, T. Horie, and Y. Sugiyama. 1993. Kinetic analysis of hepatobiliary transport of organic anions in Eisai hyperbilirubinemic mutant rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 265:1301-1312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaub, T. P., J. Kartenbeck, J. Konig, O. Vogel, R. Witzgall, W. Kriz, and D. Keppler. 1997. Expression of the conjugate export pump encoded by the mrp2 gene in the apical membrane of kidney proximal tubules. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 8:1213-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sekine, T., S. H. Cha, M. Tsuda, N. Apiwattanakul, N. Nakajima, Y. Kanai, and H. Endou. 1998. Identification of multispecific organic anion transporter 2 expressed predominantly in the liver. FEBS Lett. 429:179-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen, H., D. E. Smith, T. Yang, Y. G. Huang, J. B. Schnermann, and F. C. Brosius III. 1999. Localization of PEP1 and PEPT2 proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter mRNA and protein in rat kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 276:F658-F665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shin, M., L.-I. Larsson, D. M. Hougaard, and K. Fujiwara. 2009. Daunomycin accumulation and induction of programmed cell death in rat hair follicles. Cell Tissue Res. 337:429-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shin, M., H. Matsunaga, and K. Fujiwara. 2010. Differences in accumulation of anthracyclines daunorubicin, doxorubicin, epirubicin in rat tissues revealed by immunocytochemistry. Histochem. Cell Biol. 133:677-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith, D. E., A. Pavlova, U. V. Berger, M. A. Hediger, T. Yang, Y. G. Huang, and J. B. Schnermann. 1998. Tubular localization and tissue distribution of peptide transporters in rat kidney. Pharm. Res. 15:1244-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takahashi, K., N. Nakamura, T. Terada, T. Okano, T. Futami, H. Saito, and K. Inui. 1998. Interaction of beta-lactam antibiotics with H+/peptide cotransporters in rat renal brush-border membranes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 286:1037-1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Terada, T., and K. Inui. 2008. Physiological and pharmacokinetic roles of H+/organic cation antiporters (MATE/SLC47A). Biochem. Pharmacol. 75:1689-1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tojo, A., T. Sekine, N. Nakajima, M. Hosoyamada, Y. Kanai, K. Kimura, and H. Endou. 1999. Immunocytochemical localization of multispecific renal organic anion transporter 1 in rat kidney. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10:464-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsuji, A. 2006. Impact of transporter-mediated drug absorption, distribution, elimination and drug interactions in antimicrobial chemotherapy. J. Infect. Chemother. 12:241-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsuji, A., T. Terasaki, I. Tamai, and H. Hirooka. 1987. H+ gradient-dependent and carrier-mediated transport of cefixime, a new cephalosporin antibiotic, across brush-border membrane vesicles from rat small intestine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 241:594-601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsuji, A., T. Terasaki, I. Tamai, and K. Takeda. 1990. In vitro evidence for carrier-mediated uptake of β-lactam antibiotics through organic anion transport systems in rat kidney and liver. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 253:315-320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uwai, Y., M. Okuda, K. Takami, Y. Hashimoto, and K. Inui. 1998. Functional characterization of the rat multispecific organic anion transporter OAT1 mediating basolateral uptake of anionic drugs in the kidney. FEBS Lett. 438:321-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.VanWert, A. L., R. M. Bailey, and D. H. Sweet. 2007. Organic anion transporter 3 (Oat3/Slc22a8) knockout mice exhibit altered clearance and distribution of penicillin G. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 293:F1332-F1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yabuuchi, H., I. Tamai, K. Morita, T. Kouda, K. Miyamoto, E. Takeda, and A. Tsuji. 1998. Hepatic sinusoidal membrane transport of anionic drugs mediated by anion transporter Npt1. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 286:1391-1396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang, C. Y., A. H. Dantzig, and C. Pidgeon. 1999. Intestinal peptide transport systems and oral drug availability. Pharm. Res. 16:1331-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]