Abstract

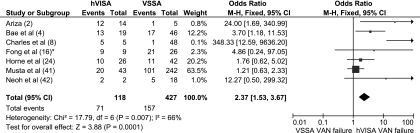

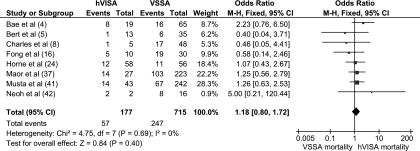

The prevalence of heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (hVISA) is 1.3% in published studies. Clinical associations include high-inoculum infections and glycopeptide failure, with hVISA infections associated with a 2.37-times-greater failure rate (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.53 to 3.67) compared to vancomycin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (VSSA) infections. Despite this, 30-day mortality rates were similar to those for VSSA infections (odds ratio [OR], 1.18; 95% CI, 0.81 to 1.74). The optimal therapy for hVISA requires further study.

In the presence of selection pressure, vancomycin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (VSSA) isolates are able to transform their cell wall and become less susceptible to vancomycin (51). These vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) isolates are defined by a vancomycin broth microdilution MIC of 4 to 8 μg/ml (57) and may progress through a precursor phenotype known as heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (hVISA) (11). Although the precise definition is disputed, heteroresistance refers to the presence of a resistant subpopulation (typically at a frequency of ≤10−5 to 10−6 CFU) in a fully susceptible isolate (a broth microdilution MIC of ≤2 μg/ml).

Detection.

hVISA detection is problematic, as commercial susceptibility platforms use inocula lower than the required threshold. As a consequence, multiple screening and detection methods using higher inocula and growth promotion of resistant subpopulations have been developed. Controversy remains, as some of these methods may select for resistant subpopulations in vitro rather than detect the in vivo presence of heteroresistance (60). The most accurate and reproducible method is the modified population analysis profile (PAP)-area under the curve (AUC), which utilizes the plot of the number of viable colonies against vancomycin concentration. An AUC ratio of the test strain to the reference strain (Mu3) of ≥0.9 confirms an hVISA isolate. However, PAP-AUC use is limited as it is expensive and labor- and time-intensive.

Epidemiology.

Following the first documented VISA (Mu50) and hVISA (Mu3) strains from Japan (22, 23), both phenotypes have been reported worldwide. The precise burden of hVISA is difficult to determine given the range of testing methodologies, definitions, and changes in vancomycin susceptibility breakpoints in 2006. This may explain the marked variation in hVISA prevalences detected across institutions, geographical regions, and patient populations, with surveillance studies generally confirming lower hVISA rates than those for selected clinical isolates. Nevertheless, the overall hVISA prevalence remains low at approximately 1.3% of all methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) isolates tested (Table 1) (1-6, 8, 9, 12-16, 18-20, 22, 24, 29-39, 41-47, 49, 50, 52, 55, 56, 58, 61).

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of hVISA based on method of screening/detection, origin of study, and isolate selection

| Screening testa | Confirmationa | Country or region (reference[s]) | Isolate source | No. of MRSA isolates | No. (%) of hVISA isolates detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No screening test | Macromethod Etest | Israel (37, 38) | Blood | 487 | 43 (8.8) |

| Singapore (16) | Blood | 56 | 3 (5.4) | ||

| USA (41) | Blood | 489 | 71 (14.5) | ||

| PAP-AUC | Australia (8, 24) | Blood/any | 170 | 64 (37.6) | |

| World (4) | Blood | 65 | 19 (29.2) | ||

| Japan (42) | Blood | 20 | 2 (10) | ||

| Simplified PAP | USA (14, 45, 56) | Blood | 738 | 3 (0.4) | |

| Europe (50) | Any | 302 | 0 (0) | ||

| Germany (20) | Any | 85 | 7 (8.2) | ||

| Simplified PAP | PAP | Asia (52) | Any | 1,357 | 58 (4.3) |

| Spain (2) | Device related | 19 | 14 (73.7) | ||

| Japan (22, 29) | Any | 7,774 | 35 (0.5) | ||

| Korea (32, 33) | Any | 4,045 | 24 (0.6) | ||

| Germany (6) | Any | 367 | 2 (0.5) | ||

| Variation of simplified PAP | PAP | Greece (30) | Any | 72 | 1 (1.4) |

| Italy (39) | Any | 179 | 2 (1.1) | ||

| Thailand (36, 58) | Any | 1,049 | 15 (1.4) | ||

| France (44) | Any | 171 | 2 (1.2) | ||

| Mexico (12) | Any | 152 | 1 (0.7) | ||

| Belgium (13) | Any | 2,145 | 4 (0.2) | ||

| Macromethod Etest | PAP | USA (35) | Any | 982 | 2 (0.2) |

| PAP-AUC | USA (46, 47) | Blood/any | 3,299 | 140 (4.2) | |

| Ireland (15) | Any | 3,189 | 73 (2.3) | ||

| UK (34) | Blood/nasal | 2,550 | 86 (3.4) | ||

| Canada (1) | Any | 475 | 25 (5.3) | ||

| Screening agar | PAP | Turkey (49) | Any | 256 | 46 (18) |

| Belgium (43) | Nasal/skin | 455 | 3 (0.7) | ||

| Korea (9) | Any | 37,856 | 18 (<0.1) | ||

| PAP-AUC | France (19) | Any | 2,300 | 255 (11.1) | |

| China (55) | Any | 200 | 26 (13) | ||

| USA (31) | Blood | 22 | 3 (13.6) | ||

| Simplified PAP | France (5) | Any | 48 | 13 (27.1) | |

| MIC based | UK (3) | Any | 11,242 | 0 (0) | |

| Hong Kong (61) | Blood | 52 | 3 (5.8) | ||

| MIC based | PAP | USA (18) | Blood | 30 | 0 (0) |

| Total | 82,698 | 1,063 (1.3) |

Screening and/or confirmation testing included the following tests. For a more detailed discussion on the performance of each test, see reference 25. Simplified population analysis profile (PAP): growth of (1 to 30) colonies on brain heart infusion agar supplemented with 4 mg/liter vancomycin at 48 h is considered positive for hVISA. Variations of simplified PAP include using different inoculum sizes (>10 μl), inoculum concentrations (>0.5 McFarland standard), media (Mueller-Hinton agar), antibiotics (teicoplanin), and/or vancomycin concentrations (3 or 6 mg/liter). PAP: hVISA is present when the graph of isolated colonies on brain heart infusion agar or Mueller-Hinton agar plotted against increasing vancomycin concentration at 48 h is similar to that for the reference (Mu3) strain. Analysis can be standardized using the area under the curve (PAP-AUC) with hVISA being confirmed when the ratio of the test strain to the control strain (Mu3) is between 0.9 and 1.3. Macromethod (2 McFarland standard) Etest on brain heart infusion agar is defined as positive for hVISA if the vancomycin and teicoplanin MICs are ≥8 μg/ml or the teicoplanin MIC is ≥12 μg/ml for the isolate. Screening agars: ≥1 colony isolated after 24 to 48 h on either brain heart infusion agar or Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with vancomycin or teicoplanin is considered positive for hVISA. MIC-based testing includes standard Etest or vancomycin broth microdilution of resistant subpopulations.

Clinical significance of hVISA.

All English-language studies containing the term S. aureus and any of the terms reduced susceptibility, intermediate susceptibility, and heteroresistance or heteroresistant to vancomycin or glycopeptides were identified through Medline (2006 to 2010) and reviewed. All articles with clinical details are summarized in Table 2 (2, 4, 5, 8, 16, 24, 28, 31, 33, 37, 38, 41). Considerable heterogeneity exists between studies due to the differing patient populations studied, testing methodologies used, and MRSA isolates selected (i.e., initial blood culture compared to final isolate). Despite this, high-inoculum infections (such as infective endocarditis, osteomyelitis, deep abscesses, and prosthetic device infections) (8, 16, 37) and vancomycin treatment failure (defined as persistent infection or bacteremia duration and/or ongoing signs of infection) (2, 4, 8, 16, 42) were common associations with hVISA infection. After the available data were pooled, the odds of glycopeptide failure were 2.37 times greater for hVISA than for VSSA infections (odds ratio [OR], 2.37; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.53 to 3.67) (Fig. 1). Since high-inoculum infections are independently associated with bacteremic persistence (therapeutic failure) (10, 17, 31) and de novo hVISA infections do not always result in treatment failure, hVISA may reflect the consequence rather than the cause of treatment failure.

TABLE 2.

Published studies containing clinical details of hVISA-infected patients

| Study (reference no.) | Publication description | No. (%) of hVISA isolates detecteda | No. (%) of therapeutic failures, hVISA: VSSA | Therapeutic failure definition used in study | No. (%) of infections with 30-day mortality, hVISA: VSSA | Other clinical finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ariza et al., 1999 (2) | MRSA orthopedic device infections (n = 19); retrospective | 14 (74) | 12 (86): 1 (20) (P not stated) | Persistence or reappearance of infection after 6 weeks of therapy | No data | All patients cured following device removal |

| Kim et al., 2002 (33) | Consecutive S. aureus isolates from any site (n = 3,363); retrospective | 24 (0.7) | 0: 0 | Not stated | 3 (14): 0 | 15 colonized patients, 7 infected patients |

| Bert et al., 2003 (5) | Consecutive MRSA isolates from any site (n = 48); retrospective | 13 (27) | 1 (10): 0 | Persistent bacteremia of >5 days | 1 (7): 6 (17) (P = NSb) | 3 colonized, 10 infected liver transplant patients |

| Charles et al., 2004 (8) | MRSA bacteremic patients (n = 53); retrospective | 5 (9) | 5 (100): 1 (2.1%) (P < 0.01) | Persistent bacteremia and fever for >7 days | 1 (20): 17 (35) (P = 0.7) | hVISA associated with high-bacterial-load infections (P = 0.001) and initial low VANf levels (P = 0.006) |

| Howden et al., 2004 (28) | hVISA confirmed bacteremic patients (n = 25); retrospective | 25 (100) | 19 (76): 0 | Persistent bacteremia or positive sterile-site culture (>7 days and 21 days of therapy, respectively) | 7 (33): 0 | |

| Khosrovaneh et al., 2004 (31) | Persistent and recurrent MRSA bacteremic patients (n = 21); retrospective | 3 (13) | Not stated | No data | Paired isolates tested with no hVISA phenotype detected in the initial blood isolate | |

| Maor et al., 2007 (38) | hVISA confirmed bacteremic patients (n = 264); retrospective | 16 (6) | 7 (44): 0 | Persistent bacteremia of >7 days | 12 (75): 0 | |

| Neoh et al., 2007 (42) | Adequately treated (VAN for >5 days with trough levels of >10 μg/ml) MRSA bacteremic patients (n = 20); retrospective | 2 (10) | 2 (100): 5 (27) (P < 0.01) | Persistence or worsening of symptoms and infection-related mortality | 2 (100): 8 (44) | hVISA associated with greater no. of febrile days (P < 0.01) and increased no. of days for CRPg to decrease by >30% of maximum value (P < 0.01) |

| Fong et al., 2009 (16) | Persistent MRSA infection (>7 days of culture positivity) (n = 56)c; retrospective | 3 (5) | 56 days for hVISA/VISA vs 46 days for VSSA (P < 0.01); 9/9 (100): 21/26 (80) bacteremic patientsd | Duration of bacteremia (in days); persistent bacteremia for >7 daysd | 5 (50): 19 (63) (P = 0.48) | hVISA/VISA associated with bone/joint (P < 0.01) and prosthesis (P = 0.04) infections and increased length of hospital stay (P < 0.01) |

| Maor et al., 2009 (37) | MRSA bacteremic patients (n = 250); retrospective | 27 (12) | 12 days for hVISA vs 2 days for VSSA (P < 0.01) | Duration of bacteremia (in days) | 14 (51): 103 (46) (P = 0.6) | hVISA associated with infective endocarditis (P = 0.007) and osteomyelitis (P = 0.006) |

| Horne et al., 2009 (24) | Consecutive clinical MRSA isolates (n = 117); prospective | 59 (50) | 10 (38): 11 (26) (P = 0.08) | Unresolved signs or symptoms of infection following standard therapy or recurrence of infection within 1 mo of cessation of therapy | 12 (21): 11 (20) (P = 0.93) | hVISA associated with lower rate of infection (P < 0.003) and bacteremia (P < 0.001) |

| Bae et al., 2009 (4) | MRSA infective endocarditis cases from the ICEe cohort (n = 65); prospective | 19 (29) | 13 (68): 17 (37) (P = 0.029) | Persistent bacteremia of >3 days despite active antibiotic treatment | 8 (42): 16 (35) (P = 0.59) | hVISA associated with congestive cardiac failure (P = 0.033) and older patients (P = 0.037) |

| Musta et al., 2009 (41) | MRSA bacteremic patients (n = 489); retrospective | 71 (17) | 20 (47): 101 (42) (P = 0.5) | Persistent bacteremia of >7 days and/or a metastatic infection | 14 (43): 43 (27) (P = 0.5) |

For details of detection methods, see Table 1.

NS, not significant.

Of the 56 patients who met the case definition, 10 cases (3 of hVISA infection and 7 of VISA infection) and 30 randomly assigned controls were selected.

Data obtained by personal communication.

ICE, International Collaboration on Endocarditis.

VAN, vancomycin.

CRP, C-reactive protein.

FIG. 1.

Forest plot (using Mantel-Haenszel analysis) of events denoting vancomycin (VAN) treatment failure (with all definitions regarded the same) in hVISA- compared to VSSA-infected patients. Squares indicate point estimates, and the size of the square indicates the weight of each study. *, data obtained by personal communication.

Intuitively, persistent bacteremia should result in greater morbidity. However, compared to VSSA infections, hVISA persistence does not lead to more metastatic complications (41). Other parameters of morbidity have not been extensively examined. A significant increase in the mean hospital stay in patients with hVISA infection has been documented in one study (16). Similarly, infection-related complications are generally not reported (secondary to the heterogeneity of the principal diagnosis) except for one study where hVISA infective endocarditis patients were more likely to develop congestive cardiac failure (4).

Significance of MIC in hVISA.

The proportion of hVISA detected is directly related to increases in vancomycin MIC with the majority (>80%) of hVISA isolates demonstrating an Etest MIC of ≥2 μg/ml (41). Although a detailed discussion of the clinical significance of higher MICs is beyond the scope of this review, several studies have documented greater mortality associated with higher-MIC-susceptible MRSA isolates (generally between 1.5 and 2 μg/ml) (21, 53). Only one study has examined both variables (vancomycin MIC and heteroresistance phenotype) in the same isolates, with neither variable predictive of overall mortality on multivariate analysis (41). Thus, the relative contribution of heteroresistance to MIC-related outcomes remains unclear and requires further study.

Mortality and hVISA.

Since hVISA is associated with parameters known to influence mortality (i.e., high-inoculum infections, persistent bacteremia, and high vancomycin MICs), one would expect an increased mortality compared to that of VSSA infections (Table 2). However, no study to date has had the power to detect such a difference. After all available data from comparative studies were pooled, hVISA was associated with a 30-day mortality rate similar to that of VSSA infections (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.81 to 1.74) (Fig. 2). These findings can in part be explained by the reduced virulence and decreased host immune responses demonstrated in animal infection models and laboratory studies with hVISA infections (27, 40). A clinical study indirectly supports this link, with hVISA significantly more likely to be associated with colonization rather than infection (24).

FIG. 2.

Forest plot (using Mantel-Haenszel analysis) of 30-day mortality in hVISA- compared to VSSA-infected patients with “events” denoting deaths in each group. Squares indicate point estimates, and the size of the square indicates the weight of each study.

Conclusion and therapeutic implications.

The role of vancomycin in the treatment of hVISA remains unclear, as heteroresistance may emerge during glycopeptide therapy, especially in infections associated with poor antibiotic penetration (infective endocarditis and osteomyelitis) (8). Despite these deficiencies, no new antibiotic has been documented to be superior to vancomycin (17). Alternative agents have been used successfully in numerous case reports (25). However, potential concerns remain when prescribing these agents. These include toxicity with prolonged linezolid use (7), possible cross-resistance with lipoglycopeptides (54), and the clinical relevance of emerging low-level daptomycin nonsusceptibility during treatment of hVISA infections (48). An important adjunct to antimicrobial therapy and a key component of success is surgical debridement for high-inoculum hVISA infections (26). Irrespective of treatment choice, MRSA bacteremia mortality remains high (59). Therefore, further research should be aimed at developing new agents and defining the optimal pharmacodynamic parameters of current antibiotics, including vancomycin, in targeting specific clinical contexts.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam, H. J., L. Louie, C. Watt, D. Gravel, E. Bryce, M. Loeb, A. Matlow, A. McGeer, M. R. Mulvey, and A. E. Simor. 2010. Detection and characterization of heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Canada: results from the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program, 1995-2006. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:945-949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ariza, J., M. Pujol, J. Cabo, C. Pena, N. Fernandez, J. Linares, J. Ayats, and F. Gudiol. 1999. Vancomycin in surgical infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with heterogeneous resistance to vancomycin. Lancet 353:1587-1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aucken, H. M., M. Warner, M. Ganner, A. P. Johnson, J. F. Richardson, B. D. Cookson, and D. M. Livermore. 2000. Twenty months of screening for glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:639-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bae, I. G., J. J. Federspiel, J. M. Miro, C. W. Woods, L. Park, M. J. Rybak, T. H. Rude, S. Bradley, S. Bukovski, C. G. de la Maria, S. S. Kanj, T. M. Korman, F. Marco, D. R. Murdoch, P. Plesiat, M. Rodriguez-Creixems, P. Reinbott, L. Steed, P. Tattevin, M. F. Tripodi, K. L. Newton, G. R. Corey, and V. G. Fowler, Jr. 2009. Heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate susceptibility phenotype in bloodstream methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from an international cohort of patients with infective endocarditis: prevalence, genotype, and clinical significance. J. Infect. Dis. 200:1355-1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bert, F., J. Clarissou, F. Durand, D. Delefosse, C. Chauvet, P. Lefebvre, N. Lambert, and C. Branger. 2003. Prevalence, molecular epidemiology, and clinical significance of heterogeneous glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus in liver transplant recipients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5147-5152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bierbaum, G., K. Fuchs, W. Lenz, C. Szekat, and H. G. Sahl. 1999. Presence of Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin in Germany. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 18:691-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bishop, E., S. Melvani, B. P. Howden, P. G. Charles, and M. L. Grayson. 2006. Good clinical outcomes but high rates of adverse reactions during linezolid therapy for serious infections: a proposed protocol for monitoring therapy in complex patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1599-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charles, P. G., P. B. Ward, P. D. Johnson, B. P. Howden, and M. L. Grayson. 2004. Clinical features associated with bacteremia due to heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:448-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung, G., J. Cha, S. Han, H. Jang, K. Lee, J. Yoo, H. Kim, S. Eun, B. Kim, O. Park, and Y. Lee. 2010. Nationwide surveillance study of vancomycin intermediate Staphylococcus aureus strains in Korean hospitals from 2001 to 2006. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20:637-642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cremieux, A. C., B. Maziere, J. M. Vallois, M. Ottaviani, A. Azancot, H. Raffoul, A. Bouvet, J. J. Pocidalo, and C. Carbon. 1989. Evaluation of antibiotic diffusion into cardiac vegetations by quantitative autoradiography. J. Infect. Dis. 159:938-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cui, L., X. Ma, K. Sato, K. Okuma, F. C. Tenover, E. M. Mamizuka, C. G. Gemmell, M. N. Kim, M. C. Ploy, N. El-Solh, V. Ferraz, and K. Hiramatsu. 2003. Cell wall thickening is a common feature of vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delgado, A., J. T. Riordan, R. Lamichhane-Khadka, D. C. Winnett, J. Jimenez, K. Robinson, F. G. O'Brien, S. A. Cantore, and J. E. Gustafson. 2007. Hetero-vancomycin-intermediate methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate from a medical center in Las Cruces, New Mexico. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1325-1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denis, O., C. Nonhoff, B. Byl, C. Knoop, S. Bobin-Dubreux, and M. J. Struelens. 2002. Emergence of vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus in a Belgian hospital: microbiological and clinical features. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:383-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eguia, J. M., C. Liu, M. Moore, E. M. Wrone, J. Pont, J. L. Gerberding, and H. F. Chambers. 2005. Low colonization prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus with reduced vancomycin susceptibility among patients undergoing hemodialysis in the San Francisco Bay area. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:1617-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzgibbon, M. M., A. S. Rossney, and B. O'Connell. 2007. Investigation of reduced susceptibility to glycopeptides among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from patients in Ireland and evaluation of agar screening methods for detection of heterogeneously glycopeptide-intermediate S. aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3263-3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fong, R. K., J. Low, T. H. Koh, and A. Kurup. 2009. Clinical features and treatment outcomes of vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) and heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (hVISA) in a tertiary care institution in Singapore. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28:983-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fowler, V. G., Jr., H. W. Boucher, G. R. Corey, E. Abrutyn, A. W. Karchmer, M. E. Rupp, D. P. Levine, H. F. Chambers, F. P. Tally, G. A. Vigliani, C. H. Cabell, A. S. Link, I. DeMeyer, S. G. Filler, M. Zervos, P. Cook, J. Parsonnet, J. M. Bernstein, C. S. Price, G. N. Forrest, G. Fatkenheuer, M. Gareca, S. J. Rehm, H. R. Brodt, A. Tice, and S. E. Cosgrove. 2006. Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N. Engl. J. Med. 355:653-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franchi, D., M. W. Climo, A. H. Wong, M. B. Edmond, and R. P. Wenzel. 1999. Seeking vancomycin resistant Staphylococcus aureus among patients with vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:1566-1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garnier, F., D. Chainier, T. Walsh, A. Karlsson, A. Bolmstrom, C. Grelaud, M. Mounier, F. Denis, and M. C. Ploy. 2006. A 1 year surveillance study of glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus strains in a French hospital. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:146-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geisel, R., F. J. Schmitz, L. Thomas, G. Berns, O. Zetsche, B. Ulrich, A. C. Fluit, H. Labischinsky, and W. Witte. 1999. Emergence of heterogeneous intermediate vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolates in the Dusseldorf area. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43:846-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hidayat, L. K., D. I. Hsu, R. Quist, K. A. Shriner, and A. Wong-Beringer. 2006. High-dose vancomycin therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: efficacy and toxicity. Arch. Intern. Med. 166:2138-2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiramatsu, K., N. Aritaka, H. Hanaki, S. Kawasaki, Y. Hosoda, S. Hori, Y. Fukuchi, and I. Kobayashi. 1997. Dissemination in Japanese hospitals of strains of Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin. Lancet 350:1670-1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiramatsu, K., H. Hanaki, T. Ino, K. Yabuta, T. Oguri, and F. C. Tenover. 1997. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 40:135-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horne, K. C., B. P. Howden, E. A. Grabsch, M. Graham, P. B. Ward, S. Xie, B. C. Mayall, P. D. Johnson, and M. L. Grayson. 2009. Prospective comparison of the clinical impacts of heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-susceptible MRSA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3447-3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howden, B. P., J. K. Davies, P. D. Johnson, T. P. Stinear, and M. L. Grayson. 2010. Reduced vancomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus, including vancomycin-intermediate and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate strains: resistance mechanisms, laboratory detection, and clinical implications. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23:99-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howden, B. P., P. D. Johnson, P. G. Charles, and M. L. Grayson. 2004. Failure of vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howden, B. P., D. J. Smith, A. Mansell, P. D. Johnson, P. B. Ward, T. P. Stinear, and J. K. Davies. 2008. Different bacterial gene expression patterns and attenuated host immune responses are associated with the evolution of low-level vancomycin resistance during persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. BMC Microbiol. 8:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howden, B. P., P. B. Ward, P. G. Charles, T. M. Korman, A. Fuller, P. du Cros, E. A. Grabsch, S. A. Roberts, J. Robson, K. Read, N. Bak, J. Hurley, P. D. Johnson, A. J. Morris, B. C. Mayall, and M. L. Grayson. 2004. Treatment outcomes for serious infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:521-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ike, Y., Y. Arakawa, X. Ma, K. Tatewaki, M. Nagasawa, H. Tomita, K. Tanimoto, and S. Fujimoto. 2001. Nationwide survey shows that methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains heterogeneously and intermediately resistant to vancomycin are not disseminated throughout Japanese hospitals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4445-4451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kantzanou, M., P. T. Tassios, A. Tseleni-Kotsovili, N. J. Legakis, and A. C. Vatopoulos. 1999. Reduced susceptibility to vancomycin of nosocomial isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43:729-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khosrovaneh, A., K. Riederer, S. Saeed, M. S. Tabriz, A. R. Shah, M. M. Hanna, M. Sharma, L. B. Johnson, M. G. Fakih, and R. Khatib. 2004. Frequency of reduced vancomycin susceptibility and heterogeneous subpopulation in persistent or recurrent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:1328-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim, H. B., W. B. Park, K. D. Lee, Y. J. Choi, S. W. Park, M. D. Oh, E. C. Kim, and K. W. Choe. 2003. Nationwide surveillance for Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin in Korea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2279-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim, M. N., S. H. Hwang, Y. J. Pyo, H. M. Mun, and C. H. Pai. 2002. Clonal spread of Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin in a university hospital in Korea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1376-1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirby, A., R. Graham, N. J. Williams, M. Wootton, C. M. Broughton, M. Alanazi, J. Anson, T. J. Neal, and C. M. Parry. 2010. Staphylococcus aureus with reduced glycopeptide susceptibility in Liverpool, UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:721-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kosowska-Shick, K., L. M. Ednie, P. McGhee, K. Smith, C. D. Todd, A. Wehler, and P. C. Appelbaum. 2008. Incidence and characteristics of vancomycin nonsusceptible strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at Hershey Medical Center. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:4510-4513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lulitanond, A., C. Engchanil, P. Chaimanee, M. Vorachit, T. Ito, and K. Hiramatsu. 2009. The first vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from patients in Thailand. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:2311-2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maor, Y., M. Hagin, N. Belausov, N. Keller, D. Ben-David, and G. Rahav. 2009. Clinical features of heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia versus those of methicillin-resistant S. aureus bacteremia. J. Infect. Dis. 199:619-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maor, Y., G. Rahav, N. Belausov, D. Ben-David, G. Smollan, and N. Keller. 2007. Prevalence and characteristics of heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in a tertiary care center. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1511-1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marchese, A., G. Balistreri, E. Tonoli, E. A. Debbia, and G. C. Schito. 2000. Heterogeneous vancomycin resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated in a large Italian hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:866-869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCallum, N., H. Karauzum, R. Getzmann, M. Bischoff, P. Majcherczyk, B. Berger-Bachi, and R. Landmann. 2006. In vivo survival of teicoplanin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and fitness cost of teicoplanin resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2352-2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Musta, A. C., K. Riederer, S. Shemes, P. Chase, J. Jose, L. B. Johnson, and R. Khatib. 2009. Vancomycin MIC plus heteroresistance and outcome of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: trends over 11 years. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1640-1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neoh, H. M., S. Hori, M. Komatsu, T. Oguri, F. Takeuchi, L. Cui, and K. Hiramatsu. 2007. Impact of reduced vancomycin susceptibility on the therapeutic outcome of MRSA bloodstream infections. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 6:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nonhoff, C., O. Denis, and M. J. Struelens. 2005. Low prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptides in Belgian hospitals. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11:214-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reverdy, M. E., S. Jarraud, S. Bobin-Dubreux, E. Burel, P. Girardo, G. Lina, F. Vandenesch, and J. Etienne. 2001. Incidence of Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptides in two French hospitals. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 7:267-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rybak, M. J., R. Cha, C. M. Cheung, V. G. Meka, and G. W. Kaatz. 2005. Clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus from 1987 and 1989 demonstrating heterogeneous resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 51:119-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rybak, M. J., S. N. Leonard, K. L. Rossi, C. M. Cheung, H. S. Sader, and R. N. Jones. 2008. Characterization of vancomycin-heteroresistant Staphylococcus aureus from the metropolitan area of Detroit, Michigan, over a 22-year period (1986 to 2007). J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2950-2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sader, H. S., R. N. Jones, K. L. Rossi, and M. J. Rybak. 2009. Occurrence of vancomycin-tolerant and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate strains (hVISA) among Staphylococcus aureus causing bloodstream infections in nine USA hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:1024-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakoulas, G., J. Alder, C. Thauvin-Eliopoulos, R. C. Moellering, Jr., and G. M. Eliopoulos. 2006. Induction of daptomycin heterogeneous susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus by exposure to vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1581-1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sancak, B., S. Ercis, D. Menemenlioglu, S. Colakoglu, and G. Hascelik. 2005. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin in a Turkish university hospital. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:519-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmitz, F. J., A. Krey, R. Geisel, J. Verhoef, H. P. Heinz, and A. C. Fluit. 1999. Susceptibility of 302 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from 20 European university hospitals to vancomycin and alternative antistaphylococcal compounds. SENTRY Participants Group. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 18:528-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sieradzki, K., and A. Tomasz. 2003. Alterations of cell wall structure and metabolism accompany reduced susceptibility to vancomycin in an isogenic series of clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 185:7103-7110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song, J. H., K. Hiramatsu, J. Y. Suh, K. S. Ko, T. Ito, M. Kapi, S. Kiem, Y. S. Kim, W. S. Oh, K. R. Peck, and N. Y. Lee. 2004. Emergence in Asian countries of Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4926-4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soriano, A., F. Marco, J. A. Martinez, E. Pisos, M. Almela, V. P. Dimova, D. Alamo, M. Ortega, J. Lopez, and J. Mensa. 2008. Influence of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration on the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Streit, J. M., H. S. Sader, T. R. Fritsche, and R. N. Jones. 2005. Dalbavancin activity against selected populations of antimicrobial-resistant Gram-positive pathogens. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 53:307-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun, W., H. Chen, Y. Liu, C. Zhao, W. W. Nichols, M. Chen, J. Zhang, Y. Ma, and H. Wang. 2009. Prevalence and characterization of heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus isolates from 14 cities in China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3642-3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tallent, S. M., T. Bischoff, M. Climo, B. Ostrowsky, R. P. Wenzel, and M. B. Edmond. 2002. Vancomycin susceptibility of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates causing nosocomial bloodstream infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2249-2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tenover, F. C., and R. C. Moellering, Jr. 2007. The rationale for revising the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute vancomycin minimal inhibitory concentration interpretive criteria for Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:1208-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trakulsomboon, S., S. Danchaivijitr, Y. Rongrungruang, C. Dhiraputra, W. Susaemgrat, T. Ito, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. First report of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin in Thailand. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:591-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turnidge, J. D., D. Kotsanas, W. Munckhof, S. Roberts, C. M. Bennett, G. R. Nimmo, G. W. Coombs, R. J. Murray, B. Howden, P. D. Johnson, and K. Dowling. 2009. Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: a major cause of mortality in Australia and New Zealand. Med. J. Aust. 191:368-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walsh, T. R., R. A. Howe, M. Wootton, P. M. Bennett, and A. P. MacGowan. 2001. Detection of glycopeptide resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:357-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong, S. S., P. L. Ho, P. C. Woo, and K. Y. Yuen. 1999. Bacteremia caused by staphylococci with inducible vancomycin heteroresistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:760-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]