Abstract

In this article, we describe the distributions of Entomoplasmatales bacteria across the ants, identifying a novel lineage of gut bacteria that is unique to the army ants. While our findings indicate that the Entomoplasmatales are not essential for growth or development, molecular analyses suggest that this relationship is host specific and potentially ancient. The documented trends add to a growing body of literature that hints at a diversity of undiscovered associations between ants and bacterial symbionts.

The ants are a diverse and abundant group of arthropods that have evolved symbiotic relationships with a wide diversity of organisms, including bacteria (52, 55). Although bacteria comprise one of the least studied groups of symbiotic partners across these insects, even our limited knowledge suggests that they have played integral roles in the success of herbivorous and fungivorous ants (9, 12, 15, 37, 41). Several of these symbiotic bacteria are found in ant guts, habitats that appear hospitable to a wide range of microbes (24, 27, 46, 39, 41). The composition of gut communities varies between ant taxa and across the trophic scale (41), revealing that ecological and evolved physiological factors likely shape the types of microbes that colonize these environments. In addition to gut associates, some ants harbor microbes in different locations. For instance, bacteria colonize cuticular crypts of leaf-cutter ants and their relatives, secreting antibiotics that defend their fungal food sources against microbial pathogens (10, 11). Phylogenetic analyses suggest that these relationships are less specific than those between herbivorous ants and their gut microbes, since the cuticular bacteria are closely related to free-living microbes (35, 44).

Although they have been rigorously studied in a limited number of host taxa, these intriguing relationships hint at a broader significance for bacteria in the ecology and evolution of the ants. To help expand our knowledge of ant-bacterium interactions, we used universal PCR primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) to screen and sequence 16S rRNA genes of bacteria (41). Six of first 36 16S rRNA sequences obtained from a random sample of ants were closely related to bacteria from the order Entomoplasmatales (phylum Tenericutes; class Mollicutes) (41). Although they can act as plant and vertebrate pathogens (16, 47), these small-genome and wall-less bacteria have more typically been found across multiple insect groups (6, 18, 20, 31, 33, 49, 51), where their phenotypic effects range from mutualistic (14, 23) to detrimental (6, 34) or manipulative (13, 22, 25, 32, 38, 43).

Surveys for the Entomoplasmatales across species, tissues, and developmental stages.

Given the significance of the Entomoplasmatalesin other insect groups and their potential prevalence across the ants, we designed a diagnostic PCR assay that enabled a broad survey across this insect group (family Formicidae; order Hymenoptera; see Table S1 and additional supplemental material for details on molecular techniques). PCR screening across 313 ants (∼306 species, spanning 18 out of 21 known subfamilies) identified 19 confirmed associations with members of the Entomoplasmatales (6.2% prevalence across species; see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Since several of the identified hosts came from omnivorous or carnivorous genera, we examined the relationship between the trophic level {δ15N, obtained by the equation [(Rsample/Rstandard)−1] × 1,000, where Rstandard is the international 15N/14N standard for atmospheric N2} and prevalence of the Entomoplasmatales within genera using previously published stable isotope data (2, 12; see also the supplemental material for more information). A weighted regression analysis revealed a significantly positive association between the trophic level and the frequency of the Entomoplasmatales (regression line equation: Y = −0.0512 + 0.0246 X; Pslope = 0.0110; r2 = 0.0370). However, the small slope and low r2 value suggest a need for further investigations to verify this pattern.

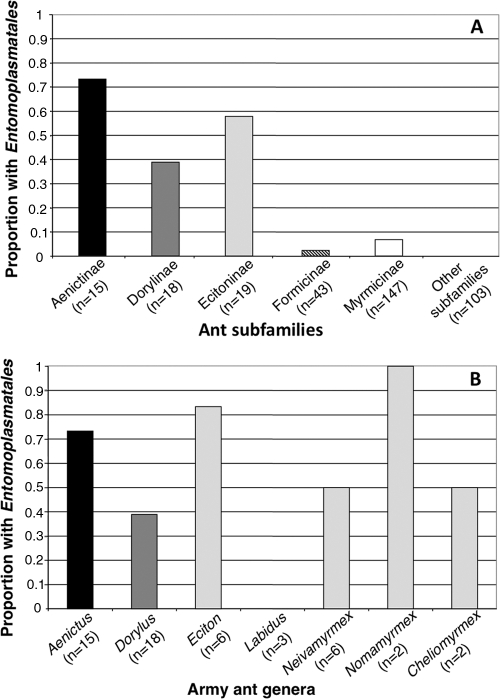

Members of the Entomoplasmatales were especially common across the army ants, a group defined by their nomadism and group predation (26). Preliminary analyses revealed that bacteria from these ants formed a host-specific lineage that grouped within the family Entomoplasmataceae. The potential for a specialized relationship between these organisms prompted us to further explore the distributions of these bacteria with additional PCR screening. To do so, we surveyed 243 additional army ants (males, adult workers, larvae, and pupae) from 82 colonies spanning 52 species (“army ant screen”; see Table S3 in the supplemental material). When we combined our screening results for adult workers with those from the general screen, we observed associations with the Entomoplasmatales in 73.3% (11/15), 38.9% (7/18), and 57.9% (11/19) of the species from the army ant subfamilies Aenictinae, Dorylinae, and Ecitoninae, respectively (Fig. 1 A). In contrast, members of the Entomoplasmatales were found in only 2 of the 15 other ant subfamilies (2.3% in the Formicinae and 6.8% in the Myrmicinae), with a combined frequency of 3.8% across 300 surveyed ants (Fig. 1A; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 1.

Distribution of the Entomoplasmatales across ant taxa. Bar graphs depict the proportion of positive species per ant subfamily (A) or army ant genus (B) based on results from diagnostic screening (pooled data from both the general and army ant screens). Species were declared positive if at least one individual ant screened positive for Entomoplasmatales. Taxa from different subfamilies are given different shading for ease of viewing (black, Aenictinae; dark gray, Dorylinae; light gray, Ecitoninae).

In spite of the prevalence and broad distributions of the Entomoplasmatales across army ant genera (Fig. 1B), the frequencies of colonized workers varied within species from 9.8% to 100% (for species with ≥4 surveyed workers), and within-colony prevalence across 12 colonies from Eciton burchellii, Eciton vagans, and Dorylus molestus never exceeded 80% (for all colonies with ≥4 surveyed workers). To assess differences in prevalence between adults and juveniles, we combined data from seven infected colonies (from three species) that were sampled across multiple developmental stages. A Fisher's exact test confirmed that members of the Entomoplasmatales were significantly more common among adult workers (21/40) than among pupae and larvae (3/40, combined) (P ≤ 0.01).

Cloning and sequencing of 16S rRNA genes suggested that the Entomoplasmatales are dominant members of the microbial communities within adult workers (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). For instance, within colonized adults, their rank abundance was always first or second while their relative clone abundance ranged from 18.8 to 71.4% (median = 40.6%). In contrast, only 10.5% of the sequenced 16S rRNA clones from a colonized E. burchellii larva belonged to the Entomoplasmatales (see Fig. S1), suggesting that adults may be more suitable hosts.

Unlike several bacteria from the related family Spiroplasmataceae, the general absence of the Entomoplasmatales in eggs and larvae argued against maternal transmission. Gut associations comprise a plausible alternative to the heritable lifestyle, since insects such as dragonflies, wasps, bees, mosquitoes, tabanid flies, and firefly beetles harbor Entomoplasmatales symbionts in their digestive systems (7, 8, 28, 31, 48, 53, 54). To test for this, we screened DNA extracted from specific ant tissues. Results of tissue-specific surveys from siblings of infected ants revealed that members of the Entomoplasmatales were found in the mid- and/or hindguts of all individuals with at least one positive tissue type (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). This was true for five different army ant species, along with four ant species from other taxa. Members of the Entomoplasmatales were occasionally detected in other tissues (see Table S4), a trend which was never observed for gut-specific bacteria of herbivorous ants (41). However, related gut bacteria in other insects can colonize the hemolymph (6, 8, 24), providing a precedent for these patterns.

Evolutionary histories of Entomoplasmatales bacterium-host interactions.

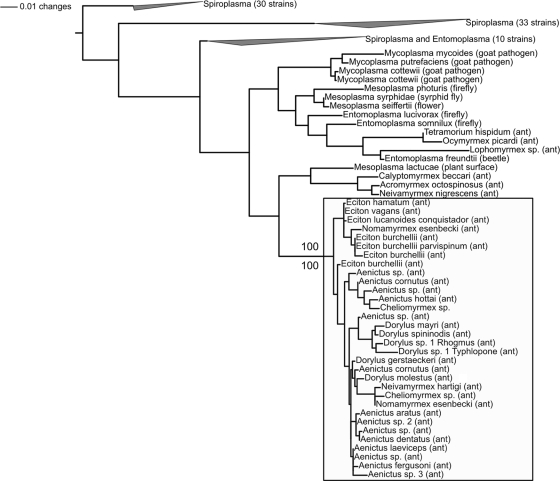

Host-specific clades of the Entomoplasmatales were frequently identified in 16S rRNA phylogenies that included microbes from ants and other arthropods, along with related bacteria from plants and mammals (Fig. 2; see also the supplemental material for phylogenetic methods). Most notably, bacteria from 27 species within the army ant subfamilies Aenictinae (genus Aenictus), Dorylinae (genus Dorylus), and Ecitoninae (genera Cheliomyrmex, Eciton, Neivamyrmex, and Nomamyrmex) formed a strongly supported host-specific clade (100% bootstrap support in both likelihood and parsimony analyses; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Only 4 of the 36 total strains identified across the army ants fell outside this clade, and each of these outliers grouped into ant-specific Entomoplasmatales lineages. In total, only 4 of the 48 analyzed strains from ants fell outside ant-specific lineages (0/36 strains from army ants and 4/12 strains from non-army ants), further underscoring the trend of host fidelity.

FIG. 2.

16S rRNA phylogeny depicting relatedness of Entomoplasmatales associates from army ants and other organisms. Maximum likelihood was used to construct a phylogeny based on an alignment of 122 16S rRNA sequences from bacteria within the order Entomoplasmatales. The tree was rooted using Mycoplasma genitalium as the outgroup (not shown). Analyzed sequences included nonredundant ant associates from this study (i.e., one representative per species per 1% phylotype), their closest relatives in GenBank (based on BLASTn searches), and selected strains from other arthropod hosts, with an emphasis on those from Drosophila, spiders, and lepidopterans. To better illustrate the main finding—a host-specific clade of microbes exclusively found in army ants (with 100% bootstrap support in parsimony and likelihood searches; “Primary Army Ant Clade”), most clades were collapsed. The full tree (with bootstrap values, strain IDs, and accession numbers but without branch lengths) can be found in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. Strains from ants are named after their hosts, and the host/environment of origin is indicated for all taxa in parentheses.

This pattern was not unique to the ants, since several other taxon-specific lineages were identified upon inspection of our phylogeny (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). For example, 8/12 Spiroplasma strains from Drosophila species fell into one of two genus-specific clades comprised of heritable symbionts (20, 33) and male killers (1). Similarly, 4/6 Spiroplasma strains from spiders formed a monophyletic group; this fell within a larger lineage of arthropod-associated Spiroplasma comprised of gut associates and maternally transmitted bacteria.

Although the phylogenetic patterns were not generally consistent with a history of cospeciation, they did suggest some degree of host specificity. Indeed, statistical analyses using UniFrac (30) and the Analysis of Traits software package (50) showed that host-specific clustering was significantly greater than would be expected by chance (Table 1; see also the supplemental material for more information on these analyses). Further analyses revealed that workers from single army ant species generally harbored monophyletic groups of bacteria (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) while those from different subfamilies tended to harbor bacteria from separate lineages (Fig. 2; Table 1). These trends could indicate that army ant subfamilies have exclusively coevolved with separate bacterial lineages since their time of divergence, even without cospeciation. However, bacteria from army ant subfamilies were not strictly monophyletic (Fig. 2), as one would expect under this scenario. Furthermore, monophyly was statistically rejected by Shimodaira-Hasegawa tests (45) (see the supplemental material, including Table S5, for more information on these analyses). Additionally, molecular clock dating suggested that bacteria from different army ant subfamilies shared a common ancestor more recently than their army ant hosts (12.5 to 50 million years, versus ∼70 to 100 million years for the army ants, according to references 3 and 4; see the supplemental material for more information). Combined, these findings suggest that strains of the Entomoplasmatales have undergone horizontal transfer between subfamilies or that ants from different subfamilies have independently acquired related bacteria (from unknown sources) since their time of divergence.

TABLE 1.

UniFrac and Analysis of Traits statistics on phylogenetic clustering of Entomoplasmatales strains from well-sampled arthropod groupsa

| Comparisonb | Environment (nc) |

UniFrac |

Analysis of Traits |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Distanced | P valuee | D statisticd,f | P value | |

| Differences between host taxa and strains from all remaining environments (entire phylogeny) | Army ants (36) | All others (87) | 0.8086 | ≤0.001 | 0.04 | <0.000001 |

| Other ants (12) | All others (111) | 0.7831 | 0.2120 | 0.077 | 0.00004 | |

| Spiders, Araneae (6) | All others (117) | 0.8988 | 0.003 | 0.034 | 0.00791 | |

| Moths and butterflies, Lepidoptera (10) | All others (113) | 0.8321 | 0.031 | 0.082 | <0.000001 | |

| Fruit flies, Drosophila (12) | All others (111) | 0.8903 | ≤0.001 | 0.061 | <0.000001 | |

| Differences between army ant subfamilies (primary army ant clade) | Aenictinae (14) | Dorylinae (7) | 0.6311 | 0.006 | NAg | NA |

| Dorylinae (7) | Ecitoninae (15) | 0.4565 | 0.004 | NA | NA | |

| Ecitoninae (15) | Aenictinae (14) | 0.7018 | 0.310 | NA | NA | |

| Differences between army ant genera (primary army ant clade) | Aenictus (14) | Dorylus (7) | 0.6331 | 0.013 | NA | NA |

| Dorylus (7) | Eciton (7) | 0.6453 | ≤0.001 | NA | NA | |

| Eciton (7) | Aenictus (14) | 0.4049 | ≤0.001 | NA | NA | |

n ≥ 6 host species.

Analyses focused on bacteria from the entire phylogeny or only on those from a subset within the primary army ant clade (see the supplemental material [Fig. S2] for the phylogeny and more details on the analyses).

Sample sizes in parentheses indicate the numbers of bacterial strains falling into each of the compared categories.

Higher UniFrac distances and lower Analysis of Traits D statistics imply greater phylogenetic separation of bacteria from the two focal categories.

Generated using UniFrac's “compare each pair” test.

Analysis of Traits analysis could be performed only on the entire 16S rRNA phylogeny.

NA, not analyzed.

Concluding remarks.

In summary, our findings provide one of the first microbial characterizations of the army ants (41), identifying a novel group of the Entomoplasmatales for these predatory insects. While these microbes were prevalent across species from three army ant subfamilies, they were found at polymorphic levels within most species and colonies, suggesting that they are not required for their hosts' growth and development. Their limited incidence across eggs, larvae, and pupae from infected colonies indicates that they are unlikely to be maternally transferred and that adults serve as more-suitable hosts. Furthermore, their localization to mid- and hind-gut tissues points toward lifestyles similar to those of related gut bacteria from other insects (5, 7, 19).

Across the ants, bacteria from the Entomoplasmatales were slightly enriched among predatory genera. It is therefore worth noting that our sequencing efforts have identified a second group of ant-specific bacteria (phylum Firmicutes) that are similarly limited to predatory ants (see the supplemental material for Fig. S4 and for more details on this lineage). Although further investigations are needed to establish the strength of these trends, they clearly contrast with those reported previously for Rhizobiales bacteria, which were primarily restricted to the guts of herbivorous ants (41).

Members of the Rhizobiales and their coinhabiting microbes also differ from the Entomoplasmatales in their stability and prevalence, since they are nearly ubiquitous within host colonies and species (41, 46). The contrasting polymorphism exhibited by associates of the Entomoplasmatales implies a considerably less integrated set of relationships. But in spite of this, phylogenetic and molecular clock analyses indicate that army ants have interacted with these bacteria for millions of years. Since army ants can range from generalized predators of arthropods to specialized predators of social insects (26), we cannot invoke similar diets as a cause of this trend. Instead, we must conclude that these bacteria have evolved a propensity to colonize army ants (specialization) or possibly that evolved behavioral or physiological attributes have predisposed the army ants to harbor selected strains of the Entomoplasmatales (selectivity). Selectivity and specialization may explain the other phylogenetic patterns detected in this study, whereby other ants, spiders, and fruit flies harbored host-specific groups of the Entomoplasmatales (Table 1; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Such trends have previously been documented for both heritable and gut-associated bacteria of insects (17, 21, 25, 29, 36, 40, 41, 42), and the relative ease with which we continue to uncover them hints at the diversity of coevolved relationships that have yet to be unveiled.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tim Pian and Karen Sullam for technical assistance. Heike Feldhaar, David Lohman, and Caspar Schöning kindly provided ant specimens. Members of the Russell and Pierce labs improved the study through useful discussion.

This work was funded by grants from the Baker Fund, the Tides Foundation, and the Putnam Expeditionary Fund of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. N.E.P. was supported by National Science Foundation grant SES-0750480. J.A.R. was supported by the Green Memorial Fund, a National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellowship in microbiology, and the Department of Biology at Drexel University; C.S.M. was supported by a graduate fellowship from the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard and the Department of Zoology at the Field Museum; D.J.C.K. was supported by the Harvard Society of Fellows.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 November 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anbutsu, H., S. Goto, and T. Fukatsu. 2008. High and low temperatures differently affect infection density and vertical transmission of male-killing Spiroplasma symbionts in Drosophila hosts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:6053-6059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blüthgen, N., G. Gebauer, and K. Fiedler. 2003. Disentangling a rainforest food web using stable isotopes: dietary diversity in a species-rich ant community. Oecologia 137:426-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brady, S. G. 2003. Evolution of the army ant syndrome: the origin and long-term evolutionary stasis of a complex of behavioral and reproductive adaptations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:6576-6579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brady, S. G., T. R. Schultz, B. L. Fisher, and P. S. Ward. 2006. Evaluating alternative hypotheses for the early evolution and diversification of ants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:18172-18177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark, T. B. 1984. Diversity of Spiroplasma host-parasite relationships. Isr. J. Med. Sci. 20:995-997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark, T. B. 1977. Spiroplasma sp., a new pathogen in honey bees. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 29:112-113. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark, T. B. 1982. Spiroplasmas—diversity of arthropod reservoirs and host-parasite relationships. Science 217:57-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark, T. B., R. F. Whitcomb, and J. G. Tully. 1982. Spiroplasmas from coleopterous insects—new ecological dimensions. Microb. Ecol. 8:401-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook, S. C., and D. W. Davidson. 2006. Nutritional and functional biology of exudate-feeding ants. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 118:1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Currie, C. R., A. N. M. Bot, and J. J. Boomsma. 2003. Experimental evidence of a tripartite mutualism: bacteria protect ant fungus gardens from specialized parasites. Oikos 101:91-102. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Currie, C. R., M. Poulsen, J. Mendenhall, J. J. Boomsma, and J. Billen. 2006. Coevolved crypts and exocrine glands support mutualistic bacteria in fungus-growing ants. Science 311:81-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson, D. W., S. C. Cook, R. R. Snelling, and T. H. Chua. 2003. Explaining the abundance of ants in lowland tropical rainforest canopies. Science 300:969-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebbert, M. A. 1991. The interaction phenotype in the Drosophila willistoni-Spiroplasma symbiosis. Evolution 45:971-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebbert, M. A., and L. R. Nault. 1994. Improved overwintering ability in Dalbulus maidis (Homoptera, Cicadellidae) vectors infected with Spiroplasma kunkelii (Mycoplasmatales, Spiroplasmataceae). Environ. Entomol. 23:634-644. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldhaar, H., J. Straka, M. Krischke, K. Berthold, S. Stoll, M. J. Mueller, and R. Gross. 2007. Nutritional upgrading for omnivorous carpenter ants by the endosymbiont Blochmannia. BMC Biol. 5:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fletcher, J., G. A. Schultz, R. E. Davis, C. E. Eastman, and R. M. Goodman. 1981. Brittle root disease of horseradish—evidence for an etiological role of Spiroplasma citri. Phytopathology 71:1073-1080. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraune, S., and M. Zimmer. 2008. Host-specificity of environmentally transmitted Mycoplasma-like isopod symbionts. Environ. Microbiol. 10:2497-2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukatsu, T., T. Tsuchida, N. Nikoh, and R. Koga. 2001. Spiroplasma symbiont of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Insecta: Homoptera). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1284-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hackett, K. J., R. F. Whitcomb, J. G. Tully, J. E. Lloyd, J. J. Anderson, T. B. Clark, R. B. Henegar, D. L. Rose, E. A. Clark, and J. L. Vaughn. 1992. Lampyridae (Coleoptera)—a plethora of Mollicute associations. Microb. Ecol. 23:181-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haselkorn, T. S., T. A. Markow, and N. A. Moran. 2009. Multiple introductions of the Spiroplasma bacterial endosymbiont into Drosophila. Mol. Ecol. 18:1294-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hongoh, Y., P. Deevong, T. Inoue, S. Moriya, S. Trakulnaleamsai, M. Ohkuma, C. Vongkaluang, N. Noparatnaraporn, and T. Kudol. 2005. Intra- and interspecific comparisons of bacterial diversity and community structure support coevolution of gut microbiota and termite host. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6590-6599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurst, G. D. D., A. P. Johnson, J. H. G. von der Schulenburg, and Y. Fuyama. 2000. Male-killing Wolbachia in Drosophila: a temperature-sensitive trait with a threshold bacterial density. Genetics 156:699-709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaenike, J., R. Unckless, S. N. Cockburn, L. M. Boelio, and S. J. Perlman. 2010. Adaptation via symbiosis: recent spread of a Drosophila defensive symbiont. Science 329:212-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaffe, K., F. H. Caetano, P. Sanchez, J. Hernandez, L. Caraballo, J. Vitelli-Flores, W. Monsalve, B. Dorta, and V. R. Lemoine. 2001. Sensitivity of ant (Cephalotes) colonies and individuals to antibiotics implies feeding symbiosis with gut microorganisms. Can. J. Zool. Rev. Can. Zool. 79:1120-1124. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiggins, F. M., G. D. D. Hurst, C. D. Jiggins, J. H. G. Von der Schulenburg, and M. E. N. Majerus. 2000. The butterfly Danaus chrysippus is infected by a male-killing Spiroplasma bacterium. Parasitology 120:439-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kronauer, D. J. C. 2009. Recent advances in army ant biology (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecol. News 12:51-65. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, H. W., F. Medina, S. B. Vinson, and C. J. Coates. 2005. Isolation, characterization, and molecular identification of bacteria from the red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) midgut. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 89:203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindh, J. M., O. Terenius, and I. Faye. 2005. 16S rRNA gene-based identification of midgut bacteria from field-caught Anopheles gambiae sensu lato and A. funestus mosquitoes reveals new species related to known insect symbionts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:7217-7223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lo, N., C. Bandi, H. Watanabe, C. Nalepa, and T. Beninati. 2003. Evidence for cocladogenesis between diverse dictyopteran lineages and their intracellular endosymbionts. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20:907-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lozupone, C., and R. Knight. 2005. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8228-8235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundgren, J. G., R. M. Lehman, and J. Chee-Sanford. 2007. Bacterial communities within digestive tracts of ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 100:275-282. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Majerus, T. M. O., J. H. G. von der Schulenburg, M. E. N. Majerus, and G. D. D. Hurst. 1999. Molecular identification of a male-killing agent in the ladybird Harmonia axyridis (Pallas) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Insect Mol. Biol. 8:551-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mateos, M., S. J. Castrezana, B. J. Nankivell, A. M. Estes, T. A. Markow, and N. A. Moran. 2006. Heritable endosymbionts of Drosophila. Genetics 174:363-376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mouches, C., J. M. Bove, J. Albisetti, T. B. Clark, and J. G. Tully. 1982. A Spiroplasma of serogroup-IV causes a May-disease-like disorder of honeybees in Southwestern France. Microb. Ecol. 8:387-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mueller, U. G., D. Dash, C. Rabeling, and A. Rodrigues. 2008. Coevolution between atine ants and actinomycete bacteria: a reevaluation. Evolution 62:2894-2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munson, M. A., P. Baumann, M. A. Clark, L. Baumann, N. A. Moran, D. J. Voegtlin, and B. C. Campbell. 1991. Evidence for the establishment of aphid-eubacterium endosymbiosis in an ancestor of 4 aphid families. J. Bacteriol. 173:6321-6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinto-Tomas, A. A., M. A. Anderson, G. Suen, D. M. Stevenson, F. S. T. Chu, W. W. Cleland, P. J. Weimer, and C. R. Currie. 2009. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation in the fungus gardens of leaf-cutter ants. Science 326:1120-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poulson, D. F., and B. Sakaguchi. 1961. “Sex-ratio” agent in Drosophila. Science 133:1489-1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roche, R. K., and D. E. Wheeler. 1997. Morphological specializations of the digestive tract of Zacryptocerus rohweri (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Morphol. 234:253-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell, J. A., B. Goldman-Huertas, C. S. Moreau, L. Baldo, J. K. Stahlhut, J. H. Werren, and N. E. Pierce. 2009. Specialization and geographic isolation among Wolbachia symbionts from ants and lycaenid butterflies. Evolution 63:624-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russell, J. A., C. S. Moreau, B. Goldman-Huertas, M. Fujiwara, D. J. Lohman, and N. E. Pierce. 2009. Bacterial gut symbionts are tightly linked with the evolution of herbivory in ants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:21236-21241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sauer, C., E. Stackebrandt, J. Gadau, B. Holldobler, and R. Gross. 2000. Systematic relationships and cospeciation of bacterial endosymbionts and their carpenter ant host species: proposal of the new taxon Candidatus Blochmannia gen. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:1877-1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulenburg, J. H. V. D., G. D. D. Hurst, D. Tetzlaff, G. E. Booth, I. A. Zakharov, and M. E. N. Majerus. 2002. History of infection with different male-killing bacteria in the two-spot ladybird beetle Adalia bipunctata revealed through mitochondrial DNA sequence analysis. Genetics 160:1075-1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sen, R., H. D. Ishak, D. Estrada, S. E. Dowd, E. K. Hong, and U. G. Mueller. 2009. Generalized antifungal activity and 454-screening of Pseudonocardia and Amycolatopsis bacteria in nests of fungus-growing ants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:17805-17810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimodaira, H., and M. Hasegawa. 1999. Multiple comparisons of log-likelihoods with applications to phylogenetic inference. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16:1114-1116. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stoll, S., J. Gadau, R. Gross, and H. Feldhaar. 2007. Bacterial microbiota associated with ants of the genus Tetraponera. Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 90:399-412. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thiaucourt, F., and G. Bolske. 1996. Contagious caprine pleuropneumonia and other pulmonary mycoplasmoses of sheep and goats. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epizoot. 15:1397-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tully, J. G., R. F. Whitcomb, K. J. Hackett, D. L. Williamson, F. Laigret, P. Carle, J. M. Bove, R. B. Henegar, N. M. Ellis, D. E. Dodge, and J. Adams. 1998. Entomoplasma freundtii sp. nov., a new species from a green tiger beetle (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae). Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:1197-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Borm, S., J. Billen, and J. J. Boomsma. 2002. The diversity of microorganisms associated with Acromyrmex leafcutter ants. BMC Evol. Biol. 2:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Webb, C. O., D. D. Ackerly, and S. W. Kembel. 2008. Phylocom: software for the analysis of phylogenetic community structure and trait evolution. Bioinformatics 24:2098-2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wedincamp, J., F. E. French, R. F. Whitcomb, and R. B. Henegar. 1997. Laboratory infection and release of Spiroplasma (Entomoplasmatales: Spiroplasmataceae) from horse flies (Diptera: Tabanidae). J. Entomol. Sci. 32:398-402. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wenseleers, T., F. Ito, S. Van Borm, R. Huybrechts, F. Volckaert, and J. Billen. 1998. Widespread occurrence of the micro-organism Wolbachia in ants. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 265:1447-1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whitcomb, R. F., F. E. French, J. G. Tully, G. E. Gasparich, D. L. Rose, P. Carle, J. Bove, R. B. Henegar, M. Konai, K. J. Hackett, J. R. Adams, T. B. Clark, and D. L. Williamson. 1997. Spiroplasma chrysopicola sp. nov., Spiroplasma gladiatoris sp. nov., Spiroplasma helicoides sp. nov., and Spiroplasma tabanidicola sp. nov., from Tabanid (Diptera: Tabanidae) flies. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:713-719. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williamson, D. L., J. R. Adams, R. F. Whitcomb, J. G. Tully, P. Carle, M. Konai, J. M. Bove, and R. B. Henegar. 1997. Spiroplasma platyhelix sp. nov., a new mollicute with unusual morphology and genome size from the dragonfly Pachydiplax longipennis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:763-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zientz, E., H. Feldhaar, S. Stoll, and R. Gross. 2005. Insights into the microbial world associated with ants. Arch. Microbiol. 184:199-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.