Abstract

Toxoplasma gondii can infect a large variety of domestic and wild animals and human beings, sometimes causing severe pathology. Rhoptries are involved in T. gondii invasion and host cell interaction and have been implicated as important virulence factors. In this study, we constructed a DNA vaccine expressing rhoptry protein 16 (ROP16) of T. gondii and evaluated the immune responses it induced in Kunming mice. The gene sequence encoding ROP16 was inserted into the eukaryotic expression vector pVAX I. We immunized Kunming mice intramuscularly. After immunization, we evaluated the immune response using a lymphoproliferative assay, cytokine and antibody measurements, and the survival times of mice challenged lethally. The results showed that mice immunized with pVAX-ROP16 developed a high level of specific antibody responses against T. gondii ROP16 expressed in Escherichia coli, a strong lymphoproliferative response, and significant levels of gamma interferon (IFN-γ), interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, and IL-10 production compared with results for other mice immunized with either empty plasmid or phosphate-buffered saline, respectively. The results showed that pVAX-ROP16 induces significant humoral and cellular Th1 immune responses. After lethal challenge, the mice immunized with pVAX-ROP16 showed a significantly (P < 0.05) prolonged survival time (21.6 ± 9.9 days) compared with control mice, which died within 7 days of challenge. Our data demonstrate, for the first time, that ROP16 triggers a strong humoral and cellular response against T. gondii and that ROP16 is a promising vaccine candidate against toxoplasmosis, worth further development.

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular parasite of the phylum Apicomplexa and can cause severe disease in humans and many species of endothermic animals, with a high infection rate throughout the world (24). The disease is of major medical and veterinary importance, being a cause of congenital disease in humans and abortion in all kinds of livestock, leading to serious economic losses worldwide (4, 15). In addition, it causes toxoplasmic encephalitis in AIDS patients (18).

Current primary control measures for human and animal toxoplasmosis depend on chemotherapy. However, the drugs used presently are not active against the cyst stage, are expensive, and are often toxic. Immunization is therefore attractive as a potential effective and easy-to-use method of preventing infection and cyst formation in T. gondii infections.

So far, however, the only vaccine against toxoplasmosis was licensed for use in sheep in Europe and New Zealand (3). This vaccine contains live, attenuated tachyzoites of the nonpersistent T. gondii strain S48. The use of a live, attenuated strain raises concerns of safety for use in food-producing animals because of the risk of reverting to the wild type with tissue cyst formation. Inactivated vaccines are typically safer, but although they usually induce a strong antibody response, the cellular immune responses are poor. Nucleic acid vaccination has proven to be a useful alternative approach that uses a plasmid vector which expresses a protein antigen. Nucleic acid vaccines offer the potential for further advancements in the production of safe and effective vaccines. Therefore, we have focused on the development of DNA-based vaccines for toxoplasmosis.

The invasive stages of apicomplexans are characterized by the presence of an apical complex composed of specialized cytoskeletal and secretory organelles, including rhoptries. Rhoptries, unique apical secretory organelles shared exclusively by all apicomplexan parasites, are known to be involved in an active parasite's penetration into the host cell, associated with the biogenesis of a specific intracellular compartment, the parasitophorous vacuole, in which the parasite multiplies intensively, avoiding intracellular killing (25). Due to the key biological role of rhoptries, rhoptry proteins have recently become vaccine candidates for the prevention of several parasites, including T. gondii. T. gondii ROP16 is translocated to the host cell nucleus as is phosphatase 2C (11), subverts STAT3/6 signaling and, in consequence, interleukin-12 (IL-12) production in infected host cells, and is considered one of the key virulence factors in the pathogenesis of T. gondii infection (25, 28, 29). There have been no studies evaluating the potential of ROP16 as a vaccine candidate against T. gondii.

The objective of the present study was to examine the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of T. gondii ROP16 in mice by constructing a eukaryotic plasmid, pVAX-ROP16, expressing ROP16, and evaluating the potential of ROP16 as a vaccine candidate against toxoplasmosis in Kunming mice against lethal challenge infection with the highly virulent RH strain of T. gondii.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and parasites.

Specific-pathogen-free (SPF)-grade female congenic Kunming mice, ages 6 to 8 weeks old, were purchased from Yat-Sen University Laboratory Animal Center. Tachyzoites of the highly virulent RH strain of T. gondii were preserved in our laboratory (Laboratory of Parasitology, College of Veterinary Medicine, South China Agricultural University) and maintained by serial intraperitoneal passage in Kunming mice. The tachyzoites were collected from the peritoneal fluids, washed by centrifugation, and then suspended in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and sonicated. The sonicate was centrifuged at 2,100 × g for 15 min.

Construction of the eukaryotic expression plasmid.

To construct the pVAX-ROP16 expression plasmid, the coding sequence of the T. gondii ROP16 gene (GenBank accession no. DQ116422, 2,124 bp from sequence positions 1 to 2124) was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of the T. gondii RH strain with a pair of oligonucleotide primers (ROP16F, forward primer, 5′-GAATTCATGAAAGTGACCACGAAAGGGC-3′; ROP16R, reverse primer, 5′-TCTAGACTACATCCGATGTGAAGAAAGTTCG-3′), and EcoR I and XbaI recognition sites (underlined) were introduced. The PCR product was cloned into the pGEM-T easy vector (Promega) and sequenced in both directions to ensure fidelity, generating pGEM-ROP16. The ROP16 fragment was cleaved by EcoR I/XbaI from pGEM-ROP16 and cloned into the EcoR I/XbaI sites of pVAX I (Invitrogen). The resulting plasmid was named pVAX-ROP16. The concentration of pVAX-ROP16 was determined by using a spectrophotometer at optical densities at 260 nm (OD260) and OD280.

Expression of ROP16 in vitro.

Marc-145 cells were transfected with pVAX-ROP16 using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were fixed with cool acetone for 15 min, and ROP16 expression was detected using the indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), with anti-T. gondii polyclonal antiserum (goat, 1:4,000; kindly provided by Delin Zhang, Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute, CAAS, Lanzhou, Gansu Province, China) and a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled donkey anti-goat IgG antibody (Proteintech Group Inc., Chicago, IL). Evans blue (Fisher) was included in the secondary antibody solution as a counterstain. Coverslips were rinsed three times with PBS. The monolayers binding the marker were covered with glycerine and examined for specific fluorescence under a Zeiss Axioplan fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

DNA immunization and challenge.

Four groups of mice (20 per group) were injected intramuscularly (i.m.) with 100 μg of plasmid DNA suspended in 100 μl sterile PBS, 100 μl in each thigh skeletal muscle, whereas control mice received PBS alone. Group I was injected with pVAX-ROP16, group II with empty pVAX I vector, also as a control, group III with PBS as a control, and group IV with nothing as a blank control. Mice were immunized using the same protocol on weeks 0, 2, and 4. Two weeks after the final inoculation, the mice in all groups were challenged intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 1 × 103 tachyzoites of the virulent T. gondii RH strain.

Blood was collected from the mouse tail vein prior to immunization. Sera were separated and stored at −20°C until used.

IgG determination.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to measure antigen-specific antibodies using an anti-T. gondii IgG ELISA kit according to the manufacture's instructions (Combined Biotech Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). In brief, microtitration plates were coated overnight at 4°C with an optimized concentration of Escherichia coli-expressed T. gondii ROP16 (200 ng/well) in PBS. The plates were blocked with 20% dried skim milk (DSM) for 1 h and incubated with mouse sera (1:100 dilution) for 1 h at 37°C. After washing with PBS-Tween 20, the bound antibodies were detected by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG, diluted 1:2,000. Immune complexes were revealed by incubation with orthophenylene diamine and 0.15% H2O2 for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 1 M H2SO4, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an ELISA reader (Bio-TekEL×800). All samples were run in triplicate.

Lymphoproliferation assay.

Briefly, splenocyte suspensions were prepared from each group of mice by pushing the spleens through a wire mesh. After the red blood cells (RBCs) were removed using RBC lysis solution (Sigma), splenocytes were resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Cells were then plated in 96-well Costar plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well and cultured with recombinant ROP16 (10 μg/ml), concanavalin A (ConA) (5 μg/ml; Sigma), or medium alone (negative control) at 37°C with 5% CO2. The proliferative activity was measured using a 3-(4,5-dimethylthylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) (5 mg/ml; Sigma) dye assay according to the method described by Bounous et al. (1). The stimulation index (SI) was calculated as the ratio of the average OD570 value of wells containing antigen-stimulated cells to the average OD570 value of wells containing only cells with medium. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Evaluation of CTL activity.

Spleen cells of mice were segregated, single-cell suspensions were prepared from euthanized mice 4 weeks after immunization, and the activity of cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) was measured by using CytoTox 96 nonradioactive cytotoxicity assay kits (Promega). Splenocyte cultures were cocultured with 2.5 μg T. gondii lysate antigen (TLA) in each well of a 24-cell plate. Five days later, Sp2/0 cells (H-2d) transfected with the plasmid pVAX-ROP16 were used as effector cells. Ten thousand target cells per well were mixed with effector cells at various effector/target cell (E:T) ratios with quadrisection and were incubated for 6 h. The percentage of specific lysis was calculated as follows: [(experimental cpm − spontaneous cpm)/(maximal cpm − spontaneous cpm)] × 100.

Cytokine assays.

Detection of cytokines was carried out according to the method described previously (26, 38). In brief, splenocytes from immunized mice were cultured with different stimuli as described for the lymphoproliferation assay. Cell-free supernatants were harvested and assayed for interleukin-2 (IL-2) and IL-4 activities at 24 h, for IL-10 activity at 72 h, and for gamma interferon (IFN-γ) activity at 96 h. The IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, and IFN-γ concentrations were evaluated using a commercial ELISA kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (R & D Systems). Cytokine concentrations were determined by reference to standard curves constructed with known amounts of mouse recombinant IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, or IL-10. The sensitivity limits for the assays were 20 pg/ml for IFN-γ, 50 pg/ml for IL-2, and 10 pg/ml for IL-4 and IL-10, respectively.

Peritoneal macrophages were cultured in 96-well plates (1 × 105 cells per well) and activated with IFN-γ (20 U/ml) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (100 ng/ml), and 1 h later, pVAX-ROP16 was transfected into peritoneal macrophages at 1 μg/well (approximately 3.6 × 1011 molecules per well). After 48 h of transfection, supernatants were collected and IL-6 and IL-12 ELISAs were performed following the manufacturer's recommendations. Each sample had three replicates.

Statistical analysis.

Data, including antibody responses, lymphoproliferation assays, and cytokine, were compared between the different groups by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). All statistical analyses were processed by SPSS13.0 Data Editor software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The results in comparisons between groups were considered different if P values were <0.05.

RESULTS

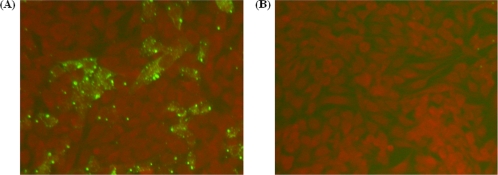

Expression of pVAX-ROP16 plasmid in Marc-145 cells.

In vitro expression of pVAX-ROP16 was evaluated by IFA at 48 h posttransfection. Cells transfected with pVAX-ROP16 showed specific green fluorescence, but the negative controls transfected with the same amount of blank pVAX I did not show any fluorescent emission (Fig. 1). IFA analysis demonstrated that one heterologously expressed protein had specific antigenicity against T. gondii-specific antiserum. This result showed that the ROP16 protein was expressed by pVAX-ROP16 in Marc-145 cells.

FIG. 1.

Analyses of ROP16 protein expression in transfected Marc-145 cells by IFA at 48 h posttransfection. (A) pVAX-ROP16 detected with Toxoplasma gondii-positive serum. (B) Negative control.

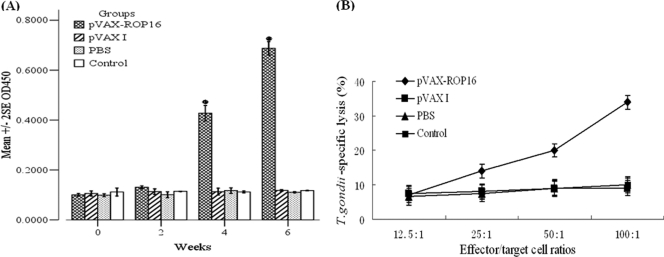

Humoral immune responses of pVAX-ROP16 in mice.

After immunization of mice with the pVAX-ROP16, antibodies were detected against ROP16 using ELISA. Figure 2A shows that anti-ROP16 antibodies were detectable as early as 2 weeks postinoculation in group I. Throughout the testing period, ROP16 antibody levels in group I were significantly higher than those in groups II, III, and IV (P < 0.05).

FIG. 2.

Determination of specific anti-ROP16 IgG and CTL activities of splenocytes. (A) Determination of specific anti-ROP16 IgG in the sera of Kunming mice immunized at weeks 0, 2, 4, and 6, post-primary vaccination as labeled. Results are expressed as means of the OD450 ± SE (n = 20)m and statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk. (B) Toxoplasma gondii-specific CTL activities of splenocytes from mice immunized with pVAX-ROP16, pVAX I, PBS, or nothing. Each point represents the mean of data for three mice that were each assayed in triplicate. E:T ratios are indicated on the horizontal axis. The vertical axis shows T. gondii-specific lysis as a percentage of the total possible lysis (% specific lysis).

Analysis of cellular immune response.

To measure the splenocyte proliferative response, the splenocytes from mice immunized with pVAX I or PBS alone or combined with ROP16 were prepared 2 weeks after the third immunization to assess the proliferative immune responses to ROP16. The splenocytes from mice immunized with pVAX-ROP16 showed a slight but significant proliferative response to ROP16 (P < 0.05), and splenocyte proliferation was ∼8-fold higher than proliferation by splenocytes from groups immunized with pVAX I, PBS, and blank control (P < 0.05). In addition, splenocytes from all experimental and control groups proliferated to comparable levels in response to the mitogen ConA (data not shown). These observations were further confirmed by the results of the CTL assay. The spleen lymphocytes from Kunming mice inoculated with pVAX-ROP16, pVAX I, PBS, or nothing were assayed for their CTL activities. As shown in Fig. 2B, spleen lymphocytes from the pVAX-ROP16 group demonstrated a high degree of CTL activity against ROP16-expressing cells compared with the other control groups (P < 0.05).

Production of cytokine by spleen cells from pVAX-ROP16-immunized mice.

The cell-mediated immunity produced in the immunized mice was indirectly evaluated by measuring the amounts of cytokines (IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, and IFN-γ) released in the supernatants of the cultures of ROP16-stimulated spleen cells. Table 1 shows that splenocytes from mice immunized with pVAX-ROP16 secreted large amounts of IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-10 compared with those from mice immunized with pVAX I, PBS, and nothing. On the other hand, low levels of IL-4 and IL-10 showed a slight but significant proliferative response in splenocytes from mice immunized with pVAX-ROP16 compared to those from mice immunized with pVAX I, PBS, or nothing (P < 0.05).

TABLE 1.

Cytokine production by splenocytes of immunized Kunming mice after stimulation with ROP16

| Groupa | Cytokine production (pg/ml)b |

Proliferation SI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ | IL-2 | IL-4 | IL-10 | ||

| pVAX-ROP16 | 918 ± 12.77 a | 887.33 ± 24.94 a | 172.67 ± 7.51 a | 168 ± 19.52 a | 1.62 ± 0.02 a |

| pVAX I | 50.24 ± 11.02 b | 48.67 ± 20.55 b | 52 ± 15.52 b | 53.67 ± 8.50 b | 0.19 ± 0.03 b |

| PBS | 47.33 ± 5.13 b | 41.00 ± 7.55 b | 50.67 ± 4.73 b | 50.67 ± 6.81 b | 0.20 ± 0.06 b |

| Control | 49.33 ± 10.50 b | 45.33 ± 8.02 b | 47.67 ± 13.58 b | 50 ± 14.18 b | 0.19 ± 0.08 b |

n = 3 per group.

Splenocytes from mice were harvested 2 weeks after the last immunization. Results are presented as the arithmetic means ± standard errors of three replicate experiments. The same letter indicates no difference (P > 0.05), whereas different letters indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05). Values for IFN-γ are for 96 h, values for IL-2 and IL-4 are for 24 h, and values for IL-10 are for 72 h.

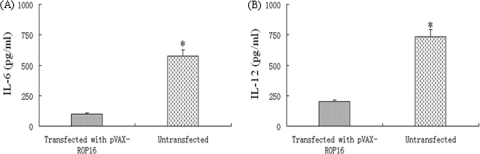

Measurement of proinflammatory cytokine concentrations.

As shown in Fig. 3A and B, the production of IL-6 or IL-12 was significantly different between the group transfected with pVAX-ROP16 and the untransfected group (P < 0.05), and the level of IL-6 or IL-12 for the transfected group was significantly lower than that for the control.

FIG. 3.

Measurement of proinflammatory cytokine concentrations. Peritoneal macrophages from Kunming mice were cultured with transfected pVAX-ROP16 in the presence of 20 U/ml IFN-γ and 100 ng/ml LPS for 24 h. Concentrations of IL-6 and IL-12 in the culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. Indicated values are means ± SD of triplicates, and statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk.

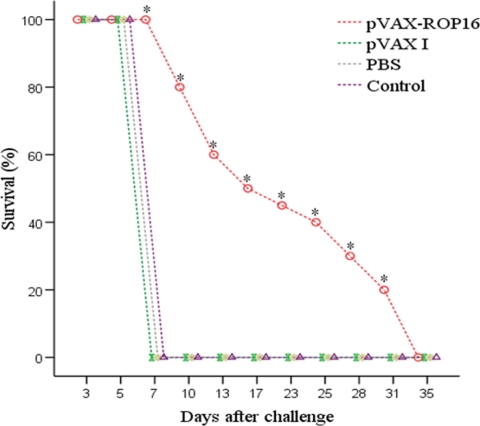

Protection of mice against challenge with T. gondii RH strain.

Immunization of mice with pVAX-ROP16 dramatically increased their survival time (21.6 ± 9.9 days) compared with that of control mice, which died within 7 days of challenge. Survival curves for the four groups of mice are shown in Fig. 4. No difference was observed among the groups with pVAX I, PBS, and nothing, and the average survival time was 7 days after challenge.

FIG. 4.

Survival rate of mice immunized with pVAX-ROP16, pVAX I, PBS, or nothing and then challenged with 1 × 103 tachyzoites. Each group had 17 mice. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk.

DISCUSSION

DNA-based vaccines have been used as a potential approach to protect animals and humans against pathogenic microorganisms and particularly intracellular parasites, because of their capacity to induce long-lasting immunity (10, 19, 27) and their ease of production and low cost (2). In this study, we used a plasmid with high biosafety, pVAX I, as the vector, which meets U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines for design of DNA vaccines.

We cloned the T. gondii ROP16 gene, one of the members of the rhoptries family, into the same mammalian expression backbone (pVAX I), designated pVAX-ROP16. With this eukaryotic system, the expressed proteins possessed authentic posttranslational modifications (e.g., glycosylation) and tertiary structure compared to a prokaryotic expression system. Consequently, conformational epitopes of the antigen should be effectively bound with antibody. By IFA analysis, we demonstrated that the FITC-labeled secondary antibody can react with ROP16 expressed in cells. Hence, the recombinant ROP16 possessed good immunogenicity (Fig. 1).

Many agents in administration of a DNA vaccine could affect immune efficacy, including immune dosages and routes; typical amounts of DNA used for i.m. inoculation of mice are 10 to 100 μg. One study has indicated that antibody titers were seen following i.m. delivery with an increase in the dose of the plasmid from 100 to 300 μg (21). Additionally, different immune routes could induce different immune response. It has been shown that i.m. inoculation resulted in higher and more persistent neutralizing antibody titers than intradermal (i.d.) inoculation (21). Although DNA vaccines are often weak (8), the immune responses may be enhanced and modulated by the use of molecular adjuvants (19, 34). In our study, we applied 100 μg recombinant plasmid alone with inoculation in mice by i.m. administration.

Pseudorabies virus and adenovirus have been demonstrated to elicit better immune response in some experiments (13, 37). In our laboratory, we are constructing the recombinant canine adenovirus expressing ROP16, and we hope to gain an ideal immune response. It has been demonstrated that a prime-boost immunization regime with a DNA plasmid and a recombinant virus, both expressing the same pathogen antigen, can induce a strong immune response, especially cell-mediated immunity (9). So, we want to apply the “prime-boost” method, using the adjuvants which have been found to function as Th-1 adjuvants (e.g., CpG oligodeoxynucleotides and IL-12) (12, 31), to improve the immune response to T. gondii in the next serial experiments.

A number of T. gondii antigens have been assessed as vaccine candidates against T. gondii infection. These include the microneme proteins (MIC1, MIC4, and MIC6) (17, 22), dense granule proteins (GRA1 to GRA7) (14, 19), rhoptry antigens (ROP1 and ROP2) (5, 32), the matrix protein MAG1 (7), and surface antigens (SAG1) (19). ROP16 of T. gondii is one of the key virulence factors (25, 29), and there have previously been no reported studies evaluating the immunogenicity of T. gondii ROP16. We therefore constructed the pVAX-ROP16 plasmid, and the results showed that the vaccine induced high levels of specific anti-T. gondii ROP16 antibodies (Fig. 2).

Several studies have shown that DNA vaccines, such as those with SAG1 and ROP2, can induce protective immune responses against T. gondii (20, 30, 33). However, a DNA vaccine containing multiantigenic SAG1-ROP2 induced only low-level immunity. At the same time, many recombinant antigens, including SAG1 and ROP2, have been proved to induce a protective immune response against toxoplasmosis in a mouse experimental model (23, 39). In the present study, although the mortality of mice was 100% in the group vaccinated with pVAX-ROP16, the life spans of mice were greatly increased compared to those in the other three groups, demonstrating that T. gondii ROP16 could induce protective immune efficacy against challenge with the virulent RH strain of T. gondii. Recent studies have shown that multiantigenic DNA vaccines and viral vectors provided excellent protection against toxoplasmosis (16, 23, 39) and were superior to a single DNA vaccine (36).

An important goal with the present vaccine constructs was to induce a T cell response as strong as the response after natural infection, and in naturally occurring T. gondii infections, the Th1 immune response is predominant (6). Compared with results with pVAX I and PBS, immunization with ROP16 enhanced the Th1 cell-mediated immunity, with high levels of IFN-γ and IL-2, but induced low levels of IL-4 and IL-10 (Table 1). Immunological aberrance occurs when locally synthesized (cerebral) IL-4 and IL-10 induce anergastic immunosuppression. These findings demonstrate that i.m. immunization with pVAX-ROP16 could potentiate the Th1-type and Th2-type cytokine responses, and it could induce the highest levels of IL-2 and IFN-γ; however, a modulated Th1-type response plays a major deterministic role in inducing cell-mediated immune responses and controlling acute T. gondii infections.

ROP16 of type I T. gondii has been shown to suppress the production of IL-6 and IL-12 when expressed in mammalian cells via activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and STAT6 (24). In our study, we measured the levels of IL-6 and IL-12, which were suppressed in the macrophages transfected with pVAX-ROP16 (Fig. 3). We speculate that STAT3 and STAT6 should be activated according to findings in related studies (24, 35). We will examine whether STAT3 and STAT6 were activated in further studies.

It is yet to be determined whether the immune response induced by ROP16 of type I T. gondii could be effective against type II T. gondii strains. We have sequenced and compared the nucleotide sequences of ROP16 from the RH strain (type I) and the QHO strain (type II) and found a sequence difference of 2.7% between the two genotypes of T. gondii (unpublished data), indicating that the genetic variation is low and that very similar ROP16 proteins could be expressed between type I and type II T strains, which may stimulate similar immune responses. This will be demonstrated experimentally in further studies.

The present study comprehensively evaluated the immunogenicity and protective potency of a DNA vaccine expressing T. gondii ROP16. This vaccine construct was able to elicit a significant humoral and cellular immune response, which significantly increased the survival time of Kunming mice challenged with the lethal T. gondii RH strain tachyzoites compared with that of controls. T. gondii ROP16 should provide a promising vaccine candidate against toxoplasmosis, worth further evaluation and development using other animal species.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported in part by grants from the State Key Laboratory of Veterinary Etiological Biology, Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (SKLVEB2009KFKT014 and SKLVEB2010KFKT010), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 30901067), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant no. 9451064201003715), the Scientific and Technological Planning Project of Guangdong Province (grant no. 2010B020307006), the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (grant no. IRT0723), the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (grant no. 20094404120016), the President's Funds of South China Agricultural University (grants no. 2009K034, 5500-209073, and 4100-K09320), and the Program for Science and Technology Innovation Activity of SCAU (grant no. L09086).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bounous, D. I., R. P. Campagnoli, and J. Brown. 1992. Comparison of MTT colorimetric assay and tritiated thymidine uptake for lymphocyte proliferation assays using chicken splenocytes. Avian Dis. 36:1022-1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunnell, B. A., and R. A. Morgan. 1998. Gene therapy for infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:42-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buxton, D. 1993. Toxoplasmosis: the first commercial vaccine. Parasitol. Today 9:335-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buxton, D. 1998. Protozoan infections (Toxoplasma gondii, Neospora caninum and Sarcocystis spp.) in sheep and goats: recent advances. Vet. Res. 29:289-310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, H., G. Chen, H. Zheng, and H. Guo. 2003. Induction of immune responses in mice by vaccination with liposome-entrapped DNA complexes encoding Toxoplasma gondii SAG1 and ROP1 genes. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.). 116:1561-1566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denkers, E. Y., and R. T. Gazzinelli. 1998. Regulation and function of T-cell-mediated immunity during Toxoplasma gondii infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:569-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Cristina, M., et al. 2004. The Toxoplasma gondii bradyzoite antigens BAG1 and MAG1 induce early humoral and cell-mediated immune responses upon human infection. Microbes Infect. 6:164-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly, J. J., B. Wahren, and M. A. Liu. 2005. DNA vaccines: progress and challenges. J. Immunol. 175:633-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doria-Rose, N. A., and N. L. Haigwood. 2003. DNA vaccine strategies: candidates for immune modulation and immunization regimens. Methods 31:207-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fachado, A., et al. 2003. Protective effect of a naked DNA vaccine cocktail against lethal toxoplasmosis in mice. Vaccine 21:1327-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbert, L. A., S. Ravindran, J. M. Turetzky, J. C. Boothroyd, and P. J. Bradley. 2007. Toxoplasma gondii targets a protein phosphatase 2C to the nuclei of infected host cells. Eukaryot. Cell 6:73-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiraoka, K., et al. 2004. Enhanced tumor-specific long-term immunity of hemagglutinating virus of Japan-mediated dendritic cell-tumor fused cell vaccination by coadministration with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J. Immunol. 173:4297-4307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu, R., et al. 2006. Prevention of rabies virus infection in dogs by a recombinant canine adenovirus type-2 encoding the rabies virus glycoprotein. Microbes Infect. 8:1090-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jongert, E., et al. 2008. An enhanced GRA1-GRA7 cocktail DNA vaccine primes anti-Toxoplasma immune responses in pigs. Vaccine 26:1025-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kravetz, J. D., and D. G. Federman. 2005. Toxoplasmosis in pregnancy. Am. J. Med. 118:212-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, Q., et al. 2008. A recombinant pseudorabies virus expressing TgSAG1 protects against challenge with the virulent Toxoplasma gondii RH strain and pseudorabies in BALB/c mice. Microbes Infect. 10:1355-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lourenco, E. V., et al. 2006. Immunization with MIC1 and MIC4 induces protective immunity against Toxoplasma gondii. Microbes Infect. 8:1244-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luft, G. J., and J. S. Remington. 1992. Toxoplasmic encephalitis in AIDS. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:211-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mévélec, M. N., D. Bout, and B. Desolme. 2005. Evaluation of protective effect of DNA vaccination with genes encoding antigens GRA4 and SAG1 associated with GM-CSF plasmid, against acute, chronical and congenital toxoplasmosis in mice. Vaccine 23:4489-4499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohamed, R. M., et al. 2003. Induction of protective immunity by DNA vaccination with Toxoplasma gondii HSP70, HSP30 and SAG1 genes. Vaccine 21:2852-2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osorio, J. E., et al. 1999. Immunization of dogs and cats with a DNA vaccine against rabies virus. Vaccine 17:1109-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng, G. H., et al. 2009. Toxoplasma gondii microneme protein 6 (MIC6) is a potential vaccine candidate against toxoplasmosis in mice. Vaccine 27:6570-6574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roque-Reséndiz, J. L., R. Rosales, and P. Herion. 2004. MVA ROP2 vaccinia virus recombinant as a vaccine candidate for toxoplasmosis. Parasitology 128:397-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saeij, J. P. J., et al. 2007. Toxoplasma co-opts host gene expression by injection of a polymorphic kinase homologue. Nature 445:324-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saeij, J., et al. 2006. Polymorphic secreted kinases are virulence factors in toxoplasmosis. Science 314:1780-1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shang, L., et al. 2009. Protection in mice immunized with a heterologous prime-boost regime using DNA and recombinant pseudorabies expressing TgSAG1 against Toxoplasma gondii challenge. Vaccine 27:2741-2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma, A. K., and G. K. Khuller. 2001. DNA vaccines: future strategies and relevance to intracellular pathogens. Immunol. Cell Biol. 79:537-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinai, A. P. 2007. The Toxoplasma kinase ROP18: an active member of a degenerate family. PLoS Pathog. 3:e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor, S., et al. 2006. A secreted serine-threonine kinase determines virulence in the eukaryotic pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. Science 314:1776-1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vercammen, M., et al. 2000. DNA vaccination with genes encoding Toxoplasma gondii antigens GRA1, GRA7, and ROP2 induces partially protective immunity against lethal challenge in mice. Infect. Immun. 68:38-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villinger, F., and A. A. Ansari. 2010. Role of IL-12 in HIV infection and vaccine. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 21:215-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang, H., et al. 2007. Immune response induced by recombinant Mycobacterium bovis BCG expressing ROP2 gene of Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitol. Int. 56:263-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei, Q. K., et al. 2006. Studies on the immunoprotection of ROP2 nuclei acid vaccine in Toxoplasma gondii infection. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong BingZa Zhi 24:337-341. (In Chinese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xue, M., et al. 2008. Comparison of cholera toxin A2/B and murine interleukin-12 as adjuvants of Toxoplasma multi-antigenic SAG1-ROP2 DNA vaccine. Exp. Parasitol. 119:352-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamamoto, M., et al. 2009. A single polymorphic amino acid on Toxoplasma gondii kinase ROP16 determines the direct and strain-specific activation of Stat3. J. Exp. Med. 206:2747-2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang, T. T., et al. 2005. Construction of monovalent and compound nucleic acid vaccines against Toxoplasma gondii with gene encoding SAG1. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi 28:14-17. (In Chinese.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan, Z., et al. 2008. A recombinant pseudorabies virus expressing rabies virus glycoprotein: safety and immunogenicity in dogs. Vaccine 26:1314-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang, X., et al. 2009. Mucosal immunity in mice induced by orally administered transgenic rice. Vaccine 27:1596-1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou, H., et al. 2007. Toxoplasma gondii: expression and characterization of a recombinant protein containing SAG1 and GRA2 in Pichia pastoris. Parasitol. Res. 100:829-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]