Abstract

Several infectious agents may cause arthritis or arthropathy. For example, infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, the etiologic agent of Lyme disease, may in the late phase manifest as arthropathy. Infections with Campylobacter, Salmonella, or Yersinia may result in a postinfectious reactive arthritis. Acute infection with parvovirus B19 (B19V) may likewise initiate transient or chronic arthropathy. All these conditions may be clinically indistinguishable from rheumatoid arthritis. Here, we present evidence that acute B19V infection may elicit IgM antibodies that are polyspecific or cross-reactive with a variety of bacterial antigens. Their presence may lead to misdiagnosis and improper clinical management, exemplified here by two case descriptions. Further, among 33 subjects with proven recent B19V infection we found IgM enzyme immunoassay (EIA) positivity for Borrelia only; for Borrelia and Salmonella; for Borrelia and Campylobacter; and for Borrelia, Campylobacter, and Salmonella in 26 (78.7%), 1 (3%), 2 (6%), and 1 (3%), respectively; however, when examined by Borrelia LineBlot, all samples were negative. These antibodies persisted over 3 months in 4/13 (38%) patients tested. Likewise, in a retrospective comparison of the results of a diagnostic laboratory, 9/11 (82%) patients with confirmed acute B19V infection showed IgM antibody to Borrelia. However, none of 12 patients with confirmed borreliosis showed any serological evidence of acute B19V infection. Our study demonstrates that recent B19V infection can be misinterpreted as secondary borreliosis or enteropathogen-induced reactive arthritis. To obtain the correct diagnosis, we emphasize caution in interpretation of polyreactive IgM and exclusion of recent B19V infection in patients examined for infectious arthritis or arthropathy.

Infection-associated clinically significant joint manifestations are common. These conditions may be self-limited or persistent. Postinfectious arthropathy can manifest as an acute arthritic syndrome mimicking early-onset rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or may have a chronic debilitating course. Sterile inflammation of joints may develop after infection with enteropathogens, such as Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia bacteria, and less often after Campylobacter infection or after sexually transmitted infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. These sterile and generally benign arthropathic disorders are collectively called reactive arthritis (ReA). In adults, parvovirus B19 (B19V), a small nonenveloped single-stranded DNA virus, may cause arthralgia or arthritis with prominent morning stiffness (9, 20). B19V arthropathy may be confused with early-onset RA or other collagenoses, e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), because of frequent autoantibody occurrence (2, 3, 13, 14). Inflammatory polyarthritis occurs also in vector-borne alphavirus infections (12, 20). Sindbis viruses are important mosquito-transmitted arboviruses in Northern Europe causing epidemics every seventh year. The disease manifests as rash of the trunk, myalgia, symmetrical polyarthralgia, or arthropathy (12). The secondary stage of Lyme disease, a chronic multisystem infectious and inflammatory disorder, develops after a tick bite that transmits the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. The infection may go undiagnosed if the tick contact is unnoticed or if the primary erythema migrans is missed or absent. Later, the insidious infection may involve the nervous system, heart, and joints (10).

The spectrum of infectious agents causing arthritis is wide. Etiological diagnosis of infectious arthritides is based on epidemiologic, clinical, radiologic, biochemical, microbiological, and serological tests and their adequate interpretation. The identification of an etiological agent not only prevents unnecessary diagnostic work-up but may lead to a cure, e.g., after complete antibiotic therapy given to a patient with secondary borreliosis; on the other hand, unnecessary and potentially harmful medication can be withdrawn, e.g., in B19V infection.

In our two index patients with prolonged arthropathy, infection serology showed positive IgM results with multiple antigens, e.g., Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Borrelia. Eventually, recent primary B19V infection was diagnosed. To determine the extent of this phenomenon, we reviewed our university hospital laboratory's serodiagnostic records for all subjects tested for both B19V and Borrelia during the 2-year period of 2008-2009. We additionally performed Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Borrelia serology on 50 samples from 33 patients with serologically verified B19V infection and, likewise, B19V serology on 17 sera from 12 patients with confirmed borreliosis. To illustrate the complexity of the diagnostic work-up in deciphering the etiology of arthropathy, we present as examples two clinical cases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients with confirmed B19V infection.

From thoroughly examined sample material collected in 1991 to 1993 during a major B19V epidemic in Finland, 50 sera from 33 subjects were retrieved for this study (Table 1). All had been studied by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for B19V IgG and IgM antibodies (11), as well as for VP2 IgG epitope type specificity (ETS) and VP1 IgG avidity (7, 11, 17, 18) for timing of the primary infection. The strict diagnostic criteria for acute B19V infection were ≥4-fold titer rise of IgG, presence of IgM, low (<15%) avidity of IgG, and low (<10) ETS ratio.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of samples from patients with proven B19V infection analyzed for the presence of bacterial IgM antibodies

| Sample type (n) | Time of venipuncture (range of days) |

|---|---|

| Single | |

| Acute phase (15) | 2-23 |

| Post-acute phase (1) | 230 |

| Paired | |

| Both from acute phase (5) | |

| First sample | 1-5 |

| Second sample | 14-33 |

| One from acute phase and one from convalescent phase (12) | |

| First sample | 1-48 |

| Second sample | 148-674 |

Twenty-seven (82%) subjects were female, of whom 5 (18%) were reported pregnant. Nineteen (56%) patients presented with exanthema, and 10 (30%) had arthralgia.

Patients with confirmed acute borreliosis.

Seventeen samples from 12 subjects, aged 3 to 83 years, 6 (50%) of whom had erythema migrans and 2 (20%) of whom had neuroborreliosis, were examined for parvovirus B19 antibodies. Borrelia serology had been performed with EIA-C (see below). Acute borreliosis had been diagnosed by significant kinetics in IgM and/or IgG antibody levels in consecutive samples or the presence of intrathecal antibodies (in neuroborreliosis), typical clinical picture, and/or detection of Borrelia DNA in cerebrospinal fluid or skin samples.

Borrelia burgdorferi serology.

Three commercial EIA kits to detect Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato IgM antibodies were used: (i) Virotech Borrelia afzelii IgM EIA test kit (Genzyme Virotech, Rüsselsheim, Germany), containing as antigens Borrelia afzelii bacterial extract and recombinant B. afzelii-specific VlsE protein (EIA-A); (ii) Borrelia IgM EIA (Biomedica, Vienna, Austria) containing a mixture of recombinant OspC proteins of B. afzelii and Borrelia garinii, the inner part of the flagellin of B. garinii, and VlsE, a fusion protein of different genospecies (EIA-B); and (iii) Liaison Borrelia IgM Quant (DiaSorin, Italy) containing recombinant OspC and VlsE antigens expressed in Escherichia coli (EIA-C). Interpretations suggested by the manufacturers were used. To detect IgG antibodies, the Liaison Borrelia IgG kit, including a VlsE antigen, was used. Antibody specificity was investigated with the Virotech Borrelia IgG/IgM LineBlot method. The intensity of each band was scored as 0 to 5 with a ruler provided by the manufacturer. Bands scoring as ≥3 were considered positive. The two cases presented below were analyzed in another laboratory for Borrelia serology with EIA (Siemens, Germany). The samples (n = 76) used for the retrospective analysis were analyzed in the university hospital laboratory with EIA-B and an in-house method with flagellum sonicate as an antigen.

Campylobacter serology.

IgM antibodies were detected with an in-house EIA. Briefly, Campylobacter jejuni antigen was prepared as described previously (16). The acid extract of C. jejuni, strain 143483, contains a mixture of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), flagella, capsular polysaccharide, and structural proteins and exhibits broad cross-reactivity between other Campylobacter strains to allow detection of recently encountered infection. High-protein-binding EIA plates (Greiner Bio-One, Germany) were coated for 2 h at room temperature with the antigen mixture at 2.5 μg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by overnight incubation at +4°C. After the plates were washed with Tris-HCl, sera (1:1,500) were added and incubated as described above. Alkaline phosphatase-labeled anti-human Fc5μ rabbit antibody (Dako, Denmark) was applied for 1.5 h at room temperature. The bound antibody was detected with paranitrophenylphosphate, and the titers were extrapolated from a calibration curve of a selected highly reactive serum. The cutoff for IgM positivity was 4,000.

Salmonella serology.

As described above, IgM antibodies were detected with an in-house EIA. The selection of antigens was based on the goals of detecting recent infection, covering the majority of gastroenteritides (caused by Salmonella enterica serotypes Typhimurium and Enteritidis), and detecting typhoid fever caused by S. enterica serotypes Typhi and Paratyphi. Lyophilized LPS from S. Enteritidis and from S. Typhimurium (Sigma) was dissolved in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6; applied at 10 μg/ml to Polysorb microplates (Nunc, Denmark) in 30% methanol-PBS with 0.02% NaN3; and incubated overnight at +56°C. After washes with PBS, the sera diluted 1:1,500 in PBS-5% skim milk (Biomedicum, CityLab, Helsinki, Finland) were applied for 2 h at room temperature with vigorous shaking at +4°C overnight. Horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-human IgM rabbit antibody (Dako, Denmark) was applied for 2 h followed by hydrogen peroxide and tetramethylbenzidene substrates. The quantitation was performed as described above. The cutoff for IgM positivity was 4,000.

Retrospective analysis.

We retrieved the data from 2008 and 2009 on all the subjects for whom both B19V and Borrelia serology tests had been performed within a 2-month interval. For both tests we used interpretations given in 2008 and 2009 by specialists of the diagnostic laboratory, without amendment. Among subjects with definitive acute B19V infection, defined by both the presence of IgM and a low or rising ETS ratio, we determined the frequency of positive Borrelia IgM results. Also, Borrelia IgM-positive subjects without evidence of acute B19V infection were counted. The numbers of subjects with both Borrelia IgM positivity and acute B19V infections permitted us to estimate the frequency of the phenomenon addressed in this study.

Ethical considerations.

The samples retrieved and analyzed in the present study had been collected for “routine” laboratory diagnosis during a B19V outbreak. The two cases with polyreactivity to multiple bacterial antigens were found by one of us (T.T.) while interpreting their laboratory data. To clarify this phenomenon, the general practitioners (GPs) were contacted, and consent for study of the medical records was obtained from the patients.

RESULTS

Below is a short description of the two patients with acute B19V infection who presented with polyspecific IgM antibodies to bacterial antigens. The cases gave an impetus for further delineation of this phenomenon.

Case 1.

A 44-year-old female had an acute febrile arthralgia in her fingers' proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, elbows, and metatarsal joints. At presentation her C-reactive protein level was 6 mg/liter (reference value, below 10) and her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 20 mm/h (reference value range, 1 to 25). Tests for IgM antibodies to Campylobacter antigen were positive, with a titer of 6,200 (reference value, <4,000); tests for IgM antibodies to Borrelia antigen (EIA; Siemens) were also positive, and those for Salmonella were borderline. The specificity of Borrelia IgM antibodies was confirmed in another laboratory with immunoblotting (Viramed Biotech AG, Germany): reactive bands p22 and p41 (intensities were read with a densitometer). Antibodies to Yersinia enterocolitica O:3 or O:9 or Yersinia pseudotuberculosis O:1a were not detected by a bacterial agglutination test. Because IgM antibodies to multiple antigens were detected, a polyspecific B-cell activation was suspected. A serology test for Sindbis virus was negative. However, B19V serology revealed acute infection (positive IgM and low IgG ETS). Six weeks later, the patient's Borrelia IgM result was still positive. Her arthralgia continued, and she was referred to a rheumatologist for consultation.

Case 2.

A 32-year-old female was on vacation in Bulgaria in May. She acquired acute gastroenteritis, and upon return, her stool was cultured for Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, and Yersinia with negative results. She complained of arthralgia of multiple joints, and 2 weeks after her return, reactive arthritis was suspected. Her urine sample taken in June was negative for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae DNA. IgM antibodies were detected for both Salmonella and Campylobacter but not for Yersinia. Borrelia IgG EIA (Siemens) was positive, and IgM EIA (Siemens) was borderline. A Borrelia IgG immunoblot assay (Viramed) was positive with bands to VlsE, p17, and p41, and also an IgM immunoblot assay was positive with bands to VlsE, p22, and p41 antigens. In September the Borrelia IgM result by Siemens EIA was negative but it was positive by EIA-A and -C. In October Campylobacter IgM antibodies were undetectable. At that time antinuclear (speckled-type) antibodies were detected in a titer of 1:320. When the sample taken in June was retrieved and analyzed for B19V serology in parallel with the sample of October, an acute infection was observed: the VP2 IgM assay was positive in both samples with respective VP2 IgG levels of 800 to 1,600 absorbance units, while the VP2 IgG ETS index turned from the diagnostic 6.1 to 33 (the latter representing prior immunity). Most likely, the B19V infection occurred between March and May and caused activation of B cells with production of polyclonal antibodies simultaneously to Borrelia, Campylobacter, and Salmonella. There was apparent prior immunity to Borrelia (positive IgG EIA); however, the Borrelia IgM antibodies could have reappeared, or the B cells could have been polyclonally restimulated.

The analysis of these medical records led to a hypothesis that acute B19V infection may activate a number of B-cell clones that after stimulation start production of antibodies to nonrelated microbial antigens, especially those of Borrelia, Salmonella, and Campylobacter. To test this hypothesis, a retrospective analysis was carried out.

Retrospective analysis.

The data records of Borrelia and B19V tests performed within a 2-month interval during 2008 and 2009 were reviewed. Altogether 76 patients fit the criteria (Table 2). The total yield of this analysis was as follows: during the 2 years, 11 subjects had a definitive recent B19V infection, and in one subject B19V infection was probable. Among the 11 B19V-infected patients, positive Borrelia IgM was seen in 9 (82%). Altogether, combined-positive serologies with the two microbes occurred exceedingly frequently. As there is no epidemiological link between the two infecting pathogens, the most plausible explanation was polyclonal stimulation. Interpreting data strictly and including only definitive diagnostic findings for B19V and positive IgM findings for Borrelia, it can be concluded that an immune activation giving rise to positive IgM results for Borrelia ensues in over half of the B19V infections. Table 2 documents the contents of the data analysis.

TABLE 2.

Retrospective analysis from 2008 to 2009 of samples analyzed within 2 months for B19V and Borrelia antibodies

| Characteristic | No. (%) of subjects with characteristic in yr: |

|

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2009 | |

| B19V and Borrelia serology tests performed | 30 | 46 |

| Definitive acute B19V infection | 7 (23.3) | 4 (8.6) |

| Definitive acute B19V infection/positive Borrelia IgM result | 6/7 (86) | 3/4 (75) |

| Positive Borrelia IgM result without acute B19V infection | 13 (43.3) | 15 (32.6) |

Borrelia, Campylobacter, and Salmonella EIA results.

To test our hypothesis further, we analyzed 50 samples from 33 subjects with proven B19V primary infection. The combined data on all EIAs are presented in Table 3. The analysis of all EIA results was performed in relation to the phase of B19V infection. Based on the known kinetics of the B19V infection markers (7, 11, 17, 18), the acute phase of B19V infection was defined as spanning 3 months after onset of symptoms, followed by the convalescent phase. In some cases the follow-up sampling was extended for 1 to 1.5 years. The analysis shows that in the acute phase of B19V infection the frequency of antibacterial IgM antibodies was very high, reaching 91% (Table 3). These polyspecific antibodies in some patients had disappeared already on the 10th day of illness, while in others they persisted for more than half a year. The frequency of antibacterial IgM persistence was very high, 38% (Table 3). As anticipated, during follow-up a tendency toward decline of antibody levels was seen (Table 4). Interestingly, one patient showed IgM reactivity in Borrelia EIA-B on day 286 but not on day 1. In contrast, during follow-up the IgM levels of this patient declined below cutoff in EIA-A and -C. Importantly, no correlation between durations of the presence of antibacterial IgM antibodies and B19V VP2-specific IgM antibodies (Biotrin, Dublin, Ireland) was observed: the B19V-specific IgM disappeared from all patients but one with persisting antibacterial IgM.

TABLE 3.

Frequency of induction and persistence of IgM antibodies to bacterial antigens elicited by acute B19V infection

| Phase of B19V infection (n) | No. (%) of samples positive for IgM from: |

No. (%) of samples with no bacterial IgM | Estimated frequency (%) of induction of antibacterial antibodies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Borrelia, in no. of commercial testsa |

Borrelia and Salmonellab,f | Borrelia and Campylobacterb | Borrelia, Salmonella, and Campylobacterb | |||||

| Three | At least two | At least onee | ||||||

| Acute (32) | 6 (18) | 20 (62) | 26 (81) | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 3 (9) | 91 |

| Convalescent (13) | 0 | 0 | 4 (31)c | 1 (7)d | 0 | 0 | 8 (61) | 38 |

Borrelia false IgM positivity was detected by EIA-A, -B, and -C in 70%, 42%, and 40% of samples, respectively.

Salmonella and Campylobacter IgM antibodies were detected in 6% and 9% of samples, respectively.

The maximum baseline antibody levels in subjects with persisting Borrelia antibodies were 17, 1.2, and 52 units for EIA-A, -B, and -C, respectively (the EIA-B antibody level represents day 1; antibodies were detectable at day 286 at a level of 39 units).

Only Salmonella antibodies persisted, and the maximum baseline antibody titer was 5,400.

Maximum time of persistence was 333 days.

Maximum time of persistence was 241 days.

TABLE 4.

Analysis of the magnitude of nonspecific antibacterial responses elicited by acute B19V infection

| Method (cutoff) | Highest positive result in EIA for B19V infection |

|

|---|---|---|

| Acute phase | Convalescence phase | |

| Borrelia EIA-A, units (<11) | 36 | 12 |

| Borrelia EIA-B, units (<11) | 31.1 | 39.6 |

| Borrelia EIA-C, units (<22) | 166 | None |

| Campylobacter EIA, titer (<4,000) | 9,100 | None |

| Salmonella EIA, titer (<4,000) | 5,400 | 4,500 |

Of note, the ubiquitous IgM positivity occurred in Borrelia EIAs from all three manufacturers included in the study. In EIA-A 32 samples were positive and 3 were borderline, corresponding to a false-positivity rate of 70% (35/50); in EIA-B 16 samples were positive and 5 were borderline (42%); and in EIA-C 17 were positive and 3 were borderline (40%). At the earliest the Borrelia IgM positivity was seen on day 1 of B19V infection symptoms. By comparison, the occurrence of Salmonella (6.2%) or Campylobacter (9.3%) IgM antibodies in B19V infection was far less frequent than that of Borrelia antibodies (81.2%) (Table 3).

Borrelia LineBlot results.

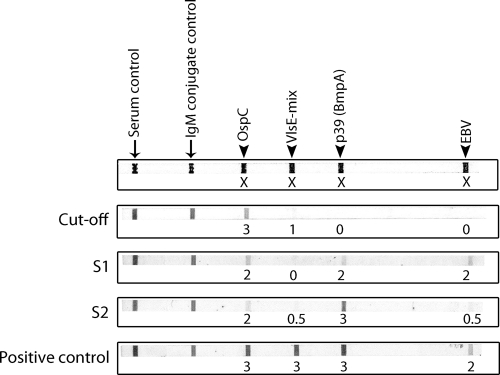

The Borrelia IgM LineBlot assay had been performed with 24/50 (48%) samples that were positive in at least one of the three EIAs. The LineBlot interpretations were based on the manufacturer's criteria, i.e., the intensity of the cutoff control band (score of 3). Only one sample (S2) showed clear bands in the IgM blot: to p39 (intensity score, 3), OspC (intensity score, 2), and VlsE (intensity score, 0.5). However, this result did not meet the positivity criteria. The sample had been reactive in EIA-A. Only 1 sample of 24 (4.1%) showed reactivity to all 3 Borrelia antigens with intensity values of 1 to 2, and 8 samples (33.3%) showed reactivities to 2 Borrelia antigens (intensity, 1 to 2). Four samples showed IgM reactivity to EBV p125 antigen, with an intensity of 1 to 2. Only one sample, positive in Liaison IgG EIA, was analyzed by the IgG LineBlot assay, with no IgG reactivity shown to any of the seven antigens. These data suggest that, even if during acute B19V infection polyspecific activation arises in response to multiple bacterial antigens, in most cases their affinity or other qualitative characteristic does not allow for positivity in immunoblotting. Figure 1 illustrates representative LineBlot results of two representative samples (S1 and S2) that showed Borrelia reactivities of subthreshold magnitude.

FIG. 1.

Four representative LineBlot results for Borrelia IgM, including one cutoff sample, patient samples S1 and S2, and the positive control. S1 and S2 show some reactivity to Borrelia antigens but, however, with band intensities weaker than that of the positive control. The numbers below each band represent estimations of the reaction intensities.

B19V serology in acute borreliosis.

Among the 12 subjects with acute borreliosis, 6 (50%) had B19V prior immunity and the remaining 6 (50%) were B19V seronegative. None showed B19V IgM, arguing against antigenic (bidirectional) cross-reactivity between these two microbes.

DISCUSSION

Using multiple approaches, we present data to show that acute B19V infection gives rise to polyclonal B-cell activation toward nonrelated bacterial antigens. This phenomenon was documented by (i) medical records for two patients in whom polyspecific IgM reactivity was observed; (ii) retrospective analysis of the laboratory data on all samples studied in 2008-2009 in our clinical microbiology laboratory simultaneously for both B19V and Borrelia antibodies; (iii) reanalysis of 50 samples from 33 subjects with verified B19V primary infection for Borrelia, Campylobacter, and Salmonella IgM antibodies; and (iv) B19V serological analysis of 12 patients with confirmed borreliosis. Taken together, we observed that acute B19V infection does elicit IgM antibodies to multiple microbial antigens. This phenomenon occurred commonly, at a frequency ranging from 75% to 86% (Table 2). Of further clinical importance is the finding that these antibodies may persist long after acute infection in many subjects (38% [Table 3]), at individually alternating levels. In comparisons of individual patients, the bacterial IgM persistence did not correlate with that of specific viral IgM, arguing against simple cross-reactivity.

In one case report a patient with B19V infection was mistakenly treated for Lyme disease (5). In that study the misdiagnosis was based on a positive Borrelia IgM EIA result, confirmed by immunoblotting. Although also our case 1 presented with a positive Borrelia EIA and immunoblot assay, the misdiagnosis of acute borreliosis was avoided because IgM antibodies were simultaneously reactive with multiple bacterial antigens. To our knowledge, our study is the first systematic report substantiated by experimental data to show that acute B19V infection may adversely affect bacterial serology, especially for Borrelia. Borrelia burgdorferi, Campylobacter, or Salmonella bacterial infections are implicated in arthritides or arthralgias considered secondary borreliosis or ReA. On the other hand, the possibility of coexistent Lyme disease and B19V infection should be kept in mind (8). Our data and earlier publications (5, 8) illustrate potential pitfalls in bacterial serology and the need for scrupulous microbiological assessment, aiming at appropriate treatment and correct prognostic assessment.

Interestingly, in our two case reports and also in the retrospective analysis we did not see production of antibodies to Yersinia as for the other bacteria. This may be due to the fact that in Yersinia serology a bacterial agglutination assay was used, with a higher-affinity threshold that might render the polyreactive antibodies undetectable.

B19V infection has been causally implicated in autoimmune conditions affecting, e.g., joints or the circulatory system (3, 13, 14). This infection is associated with an appearance of polyspecific autoantibodies, including nuclear antibodies, or rheumatoid factor that may accompany (poly)arthralgias; mono-, oligo-, or polyarthritis; vasculitides or systemic inflammatory conditions resembling SLE; polymyositis; dermatomyositis; phospholipid syndrome; and cryoglobulinemia, etc. Furthermore, simultaneous IgM EIA reactivity with measles virus, B19V, and rubella virus has been described in subjects with rash (19) but, however, without identification of the etiologic agent.

Another plausible although less likely mechanism could include molecular mimicry that gives a pathogen advantages for better survival fitness (6). Molecular mimicry may be understood as resemblance of a structure (and function) between unrelated species by chance or by a function in common.

Yet another mechanism could involve antibody cross-reactivity: i.e., linear or conformational epitopes of viruses and bacteria may be structurally so close that they are recognized by the same antibodies. For example, monoclonal antibodies raised against a B. burgdorferi strain can recognize proteins in a Western blot assay not only of the related spirochetes like Treponema pallidum or Leptospira interrogans but also of some unrelated Gram-negative bacteria, e.g., Bacteroides fragilis, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, and Escherichia coli (4). One could speculate that B19V has antigens conformationally related to those of bacteria. The likelihood of this, however, is low.

Of interest, acute borreliosis does not appear to lead to dubious results in B19V serology. All samples tested showed B19V prior immunity or were unambiguously seronegative. This observation renders the chance of antigenic cross-reactivity (bidirectionally) between the two unrelated microbes highly unlikely.

In a recent report (1), false-positive IgM results were seen in Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) serology tests after acute B19V infection using one commercial platform. False EBV IgM results were reported in 84% of cases, false HSV results were reported in 29% of cases, false cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgM results were reported in 22% of cases, and one positive result was reported in a Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato test due to the reactivity with the solid phase. In our setup this platform performed similarly to other EIAs. We believe that the phenomenon observed here represents a biological phenomenon rather than an EIA matrix effect. We suggest that it is an intrinsic feature of acute B19V infection which in response to as-yet-undetermined molecular mechanisms activates multiple B-cell clones to produce polyspecific IgM antibodies. These antibodies might be of low avidity (negative LineBlot results), can persist for a year or longer, and are not associated with an isotype class switch (nonspecific IgG not detected).

On the basis of these results, one might question the utility, in general, of detection of Borrelia IgM antibodies. It might be more feasible to study solely IgG antibodies, taking into account the fact that immunoglobulin class switch should already have occurred at the time of arthropathic Lyme borreliosis. As cross-reactivities in IgG serology occur seldom, many misdiagnoses could be avoided. Detection of Borrelia IgM may be justified in neuroborreliosis involving a de novo intrathecal immune response. The utility of Borrelia immunoblotting as a primary diagnostic method can be questioned because it can also produce false-positive results (5), especially when faint band intensities are misinterpreted. The LineBlot method could be more reliable, but due to its high cost it is unlikely to be a screening test for borreliosis.

Why do some microbial pathogens such as EBV, CMV, or Mycoplasma pneumoniae have a strong tendency to polyspecific activation? The mechanisms of this phenomenon are not yet entirely clear. The mechanism of EBV-induced polyspecific activation is easier to envision due to its direct infection of B cells (15); however, the exact molecular mechanism of polyspecific B-cell activation by B19V is at present unknown. It has earlier been shown that the nonstructural B19V protein NS1 transactivates a variety of cellular promoter regions, including those for the production of proinflammatory cytokines, e.g., tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) or interleukin-6 (IL-6) (13). Acute B19V infection may enhance the expression of these cytokines and some as-yet-undetermined growth factors, which may induce polyclonal B-cell proliferation and result in the production of polyspecific IgM antibodies. Further studies are needed to elucidate these mechanisms.

In conclusion, we present evidence that acute B19V infection may induce polyspecific IgM responses to Borrelia and less often to Campylobacter and Salmonella. Our observation highlights that in searching for arthritogenic pathogens a complete overview of the patients' serology, preferably in one laboratory, should be executed. On the basis of the results presented here, we recommend considering also the possibility of recent B19V infection when testing serological samples for borreliosis or enteropathogen-related arthropathies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Helsinki University Central Hospital Research and Education funds, the Sigrid Jusèlius Foundation, the Medical Society of Finland (FLS), and the Academy of Finland (project code 1122539).

We thank all clinicians who provided us with clinical records of their patients and Lea Hedman and Sirpa Kuismaa for expert serodiagnostic assistance. We also thank our colleagues from Islab (Kuopio, Finland) who provided us with well-characterized sera from patients with acute borreliosis.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berth, M., and E. Bosmans. 2009. Acute parvovirus B19 infection frequently causes false-positive results in Epstein-Barr virus and herpex simplex virus-specific immunoglobulin M determinations done on the Liaison platform. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:372-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broliden, K., T. Tolfvenstam, and O. Norbeck. 2006. Clinical aspects of parvovirus B19 infection. J. Int. Med. 260:285-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiche, L., A. Grados, J.-R. Harlé, and P. Cacoub. 2010. Mixed cryoglobulinemia: a role for parvovirus B19 infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:1074-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman, J. L., and J. L. Benach. 1992. Characterization of antigenic determinants of Borrelia burgdorferi shared by other bacteria. J. Infect. Dis. 165:658-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobec, M., F. Kaepelli, P. Cassinotti, and N. Satz. 2008. Persistent parvovirus B19 infection and arthralgia in a patient mistakenly treated for Lyme disease. J. Clin. Virol. 43:226-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elde, N. C., and H. S. Malik. 2009. The evolutionary conundrum of pathogen mimicry. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:787-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enders, M., et al. 2006. Human parvovirus B19 infection during pregnancy—value of modern molecular and serologic diagnostics. J. Clin. Virol. 35:400-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher, J. R., and B. E. Ostrov. 2001. Coexistent Lyme disease and parvovirus infection in a child. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 7:350-353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franssila, R., and K. Hedman. 2006. Infection and musculoskeletal conditions: viral causes of arthritis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 20:1139-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hytönen, J., P. Hartiala, J. Oksi, and M. Viljanen. 2008. Borreliosis: recent research, diagnosis, and management. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 37:161-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaikkonen, L., et al. 1999. Acute-phase-specific heptapeptide epitope for diagnosis of parvovirus B19 infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3952-3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurkela, S., T. Manni, J. Myllynen, A. Vaheri, and O. Vapalahti. 2005. Clinical and laboratory manifestations of Sindbis virus infection: prospective study, Finland, 2002-2003. J. Infect. Dis. 191:1820-1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehman, H. W., P. von Landenberg, and S. Modrow. 2003. Parvovirus B19 infection and autoimmune disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2:218-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lunardi, C., et al. 2008. Human parvovirus B19 infection and autoimmunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 8:116-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niedobitek, G., and L. S. Young. 1994. Epstein-Barr virus persistence and virus-associated tumours. Lancet 343:333-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rautelin, H., and T. U. Kosunen. 1983. An acid extract as a common antigen in Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 17:700-701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Söderlund, M., C. Brown, W. J. M. Spaan, L. Hedman, and K. Hedman. 1995. Epitope type-specific IgG responses to capsid proteins VP1 and VP2 of human parvovirus B19. J. Infect. Dis. 172:1431-1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Söderlund, M., C. Brown, B. J. Cohen, and K. Hedman. 1995. Accurate serodiagnosis of B19 parvovirus infection by measurement of IgG avidity. J. Infect. Dis. 171:710-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas, H. I., E. Barrett, L. M. Hesketh, A. Wynne, and P. Morgan-Capner. 1999. Simultaneous IgM reactivity by EIA against more than one virus in measles, parvovirus B19 and rubella infection. J. Clin. Virol. 14:107-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vassilopoulos, S., and L. H. Calabrese. 2008. Virally associated arthritis 2008: clinical, epidemiologic, and pathophysiologic considerations. Arthritis Res. Ther. 10:215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]