Abstract

Colonization rates of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus are inversely correlated in infants. Several studies have searched for determinants of this negative association. We studied the association between antipneumococcal antibodies with Staphylococcus aureus colonization and the association between antistaphylococcal antibodies with pneumococcal colonization in healthy children in the pneumococcal vaccine era. In the first year of life, no association between maternal IgG levels and colonization was seen. In addition, no association between the IgG and IgA levels in the child versus colonization status was seen.

Colonization rates of Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) and Staphylococcus aureus in the first year of life show a mirror image trend (3, 6, 7, 12). S. aureus nasal colonization is very common among newborns, but this colonization rate decreases rapidly during the first year, while pneumococcal colonization rates are low at birth and increase significantly in the first year of life (6, 7). Both pathogens are common inhabitants of the upper airways and frequently cause infections in humans; S. pneumoniae occupies the nasopharyngeal region in young children, while S. aureus primarily nestles in the anterior nares. The pneumococcus is most common in children and is essentially absent in adults, which is the opposite situation for S. aureus, which is found in the nares of half of the adult population (9). Frequent colonization with these commensal pathogens is associated with bacterial spread at the population level and an increased risk of autoinfection, including respiratory tract infections and atopic dermatitis (1, 2, 8, 19). In two studies performed before a pneumococcal vaccination was performed in the Netherlands, pneumococcal colonization with vaccine-type strains was negatively associated with S. aureus colonization, suggesting interference between the two pathogens (3, 12). Since the widespread use of pneumococcus conjugate vaccine, a shift has occurred not only toward nonvaccine S. pneumoniae serotypes but also toward higher S. aureus carriage rates in children (11, 16). Several studies have looked for determinants of this negative association. Regev-Yochay et al. found that hydrogen peroxide produced by the pneumococcus has bactericidal activity toward S. aureus (14). A more recent study from the same research group reports on the importance of the presence of the pneumococcal pilus, which decreases the odds of cocolonization (13). The negative association was found to be independent of bacterial genotype; no specific S. aureus genotypes were found to be correlated to certain S. pneumoniae genotypes (10). The aim of our study was to assess the effect of the humoral immune response on the negative association between S. pneumoniae and S. aureus in a longitudinal study of healthy Dutch children from the pre-pneumococcal-vaccine era.

This study was part of the Generation R Study, a population-based prospective cohort study monitoring pregnant women and their children. Further details on this cohort study were described previously (5). The Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands, has approved the study protocol, and written informed consent was obtained. A cord blood sample was obtained, and blood samples were obtained from infants during the visits to the research center when the infants were 6 and 14 months old. Of the 1,079 infants in the postnatal cohort, the so-called Generation R Focus Cohort, 57 were selected for this particular study on the basis of availability of biological samples. All of these children were born between February 2003 and August 2005, prior to introduction of pneumococcal vaccination in the Netherlands in 2006. The following 17 pneumococcal protein antigens were selected: PspC (CbpA) (choline-binding protein A), enolase (Eno), hyaluronidase (Hyl), immunoglobulin A1 (IgA1) protease, neuraminidase (NanA), pneumolysin (PLY), a double mutant of pneumolysin (PdBD), putative proteinase maturation protein A (PmpA), pneumococcal surface adhesin A (PsaA), pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA), the pneumococcal histidine triad (Pht) family (BVH-3 and SP1003), streptococcal lipoprotein rotamase SlrA, Streptococcus pneumoniae proteins (SP proteins), SP0189 (hypothetical protein), SP0376 (response regulator, intracellular location), SP1633 (response regulator, intracellular location), and SP1651 (thiol peroxidase, intracellular location). The following 19 staphylococcal proteins were selected: chemotaxis inhibitory protein of S. aureus (CHIPS), clumping factors A and B (ClfA and ClfB, respectively), extracellular fibrinogen-binding protein (Efb), fibronectin-binding proteins A and B (FnbpA and FnbpB, respectively), iron-responsive surface determinants A and H (IsdA and IsdH, respectively), S. aureus surface protein (Sas), staphylococcal complement inhibitor (SCIN), serine-aspartate repeat proteins D and E (SdrD and SdrE), staphylococcal enterotoxins A, B, I, M, O, and Q (SEA, SEB, SEI, SEM, SEO, and SEQ, respectively), and toxic shock syndrome toxin (TSST). IgG and IgA levels against these proteins were measured using the bead-based flow cytometry technique (xMAP; Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX) as described previously (4, 15, 17, 18). Tests were performed in independent duplicate experiments, and the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) values, reflecting semiquantitative antibody levels, were averaged. In each experiment, control beads (not coupled to protein) were included to determine nonspecific binding. In the case of nonspecific binding, these nonspecific MFI values were subtracted from the antigen-specific results. Human pooled serum (HPS) was used as an internal standard. During the visits when the infants were 1.5, 6, and 14 months old, nasopharyngeal and nasal swabs for isolation of S. pneumoniae and S. aureus were obtained. Methods of sampling were as described previously (6, 7). First, we conducted Mann-Whitney U tests to assess differences in the levels of antibodies in colonized and noncolonized children at different ages. The association between the levels of maternal IgG antibodies as a continuous variable and the dichotomous outcome of bacterial colonization at 1.5 and 6 months and colonization frequency (0 to 1 versus 2 to 3 positive swabs) was assessed by binary logistic regression analysis to assess the risk of colonization following a certain antibody level. These same tests were used to assess the association between the levels of IgG and IgA antibodies in the child at 6 and 14 months and colonization status at 6 and 14 months. A P value of <0.025 (P value of 0.05 divided by 2, the number of pathogens that are tested) was used to adjust for multiple testing and considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

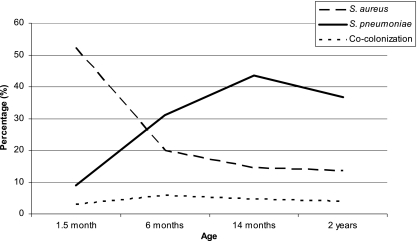

Figure 1 shows the mirror image-like graphs of S. aureus and S. pneumoniae colonization in childhood that forms the basis of our study. Maternal IgG directed against the 19 staphylococcal proteins did not protect against or increase the risk of pneumococcal colonization in the first 6 months of life. Similarly, the 17 antipneumococcal maternal IgG antibodies were not significantly associated with S. aureus colonization in the first 6 months of life. Additionally, there was no effect of maternal IgG levels on the frequency of colonization in the first year of life (Table 1). We did not study the effect of IgA levels in cord blood on later colonization, since IgA is not transported across the placenta. Hence, low levels of IgA were measured in cord blood.

FIG. 1.

Mirror image graphs of S. pneumoniae and S. aureus colonization rates in 1,079 infants from the Generation R Focus Cohort over time. S. pneumoniae colonization rates increase in the first year of life from 8.9% to 43.5% of the children and decrease again after the first year of life to 38.8%, while S. aureus colonization rates decrease in the first year of life from 52.3% to 14.5% and decrease slightly the year after to 13.6%. Cocolonization with the two pathogens exists; however, the prevalence is very low (∼5%) and stable over time.

TABLE 1.

Effect of maternal pneumococcal or staphylococcal antibodies on S. aureus or S. pneumoniae colonizationa

| Colonization and antibodyb | Prevalence (MFI) of S. aureus or S. pneumoniae in swabsc taken at: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 mo | 6 mo | At least two times in the first year | |

| S. aureus colonization | |||

| Maternal pneumococcal antibodies | |||

| BVH-3 | 0.91 (0.74-1.11) | 0.89 (0.69-1.15) | 0.89 (0.70-1.13) |

| PspC | 1.02 (0.86-1.21) | 0.95 (0.78-1.16) | 0.92 (0.76-1.12) |

| PdBD | 0.82 (0.59-1.13) | 0.78 (0.55-1.11) | 0.63 (0.41-0.98)* |

| Eno | 0.79 (0.50-1.25) | 0.77 (0.28-2.10) | 0.03 (0.00-9.10) |

| Hyal | 0.94 (0.75-1.19) | 0.93 (0.72-1.21) | 0.74 (0.51-1.08) |

| IgA1 protease | 1.00 (0.75-1.31) | 1.00 (0.73-1.38) | 0.97 (0.70-1.35) |

| NanA† | 0.85 (0.70-1.03) | 0.94 (0.77-1.15) | 0.92 (0.74-1.14) |

| PLY | 0.94 (0.76-1.15) | 0.95 (0.78-1.17) | 0.94 (0.75-1.18) |

| PpmA | 0.95 (0.78-1.15) | 0.81 (0.61-1.09) | 0.87 (0.66-1.15) |

| PsaA | 0.94 (0.82-1.09) | 1.00 (0.85-1.18) | 0.89 (0.73-1.07) |

| PspA | 1.01 (0.86-1.18) | 0.77 (0.59-1.00)* | 0.80 (0.62-1.02) |

| SlrA | 1.42 (0.63-3.23) | 0.81 (0.25-2.62) | 1.72 (0.60-4.98) |

| SP0189 | 1.80 (0.26-12.40) | ||

| SP0376† | 0.78 (0.46-1.32) | 0.96 (0.53-1.72) | 1.01 (0.59-1.72) |

| SP1003 | 1.02 (0.80-1.31) | 0.75 (0.54-1.04) | 0.90 (0.68-1.18) |

| SP1633† | 1.14 (0.77-1.68) | 1.04 (0.82-1.32) | 1.01 (0.78-1.30) |

| SP1651† | 1.08 (0.84-1.38) | 0.71 (0.33-1.55) | 0.52 (0.16-1.68) |

| S. pneumoniae colonization | |||

| Maternal staphylococcal antibodies | |||

| ClfA | 0.84 (0.55-1.29) | 0.99 (0.77-1.27) | 1.01 (0.75-1.38) |

| ClfB† | 0.99 (0.85-1.16) | 0.95 (0.84-1.08) | 0.99 (0.85-1.16) |

| SasG† | 0.99 (0.92-1.07) | 1.03 (0.98-1.07) | 0.99 (0.92-1.06) |

| IsdA | 0.42 (0.13-1.39) | 1.14 (0.81-1.60) | 1.04 (0.66-1.64) |

| IsdH | 1.00 (0.62-1.62) | 1.09 (0.79-1.51) | 1.18 (0.79-1.77) |

| FnbpA | 1.05 (0.48-2.30) | 0.96 (0.54-1.69) | 0.67 (0.30-1.50) |

| FnbpB† | 0.94 (0.70-1.26) | 1.11 (0.96-1.29) | 1.03 (0.94-1.14) |

| SdrD† | 0.89 (0.61-1.31) | 0.99 (0.89-1.09) | 0.66 (0.34-1.31) |

| SdrE | 0.49 (0.17-1.40 | 0.49 (0.24-1.00) | 0.42 (0.14-1.20) |

| SEA† | 0.99 (0.78-1.26) | 1.01 (0.86-1.19) | 1.17 (0.99-1.39) |

| SEB | 0.88 (0.70-1.12) | 0.92 (0.77-1.10) | 0.85 (0.66-1.10) |

| SEI | 0.95 (0.54-1.76) | 1.07 (0.70-1.65) | 0.93 (0.49-1.76) |

| SEM† | 0.97 (0.86-1.10) | 1.01 (0.95-1.07) | 0.97 (0.87-1.09) |

| SEO† | 1.09 (0.83-1.45) | 0.75 (0.51-1.11) | 0.70 (0.36-1.33) |

| SEQ† | 0.98 (0.89-1.08) | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) |

| TSST-1 | 1.08 (0.90-1.31) | 0.95 (0.84-1.08) | 1.02 (0.87-1.19) |

| SCIN | 0.92 (0.72-1.18) | 0.93 (0.80-1.08) | 0.89 (0.75-1.06) |

| Efb | 0.93 (0.72-1.21) | 0.78 (0.61-0.99)* | 0.86 (0.66-1.11) |

| CHIPS | 1.04 (0.79-1.36) | 0.84 (0.69-1.02) | 0.96 (0.77-1.21) |

Swabs were taken from the infants when the infants were 1.5 and 6 months old. The values in the table are median fluorescence intensities (MFIs); the values in parentheses are ranges. Using binary logistic regression analyses, differences in colonization prevalence were assessed per MFI unit. All MFI values were divided by 1,000, except for the antibodies with a † symbol, the MFI values for these antibodies were divided by 100. There were swabs missing at 1.5 months (n = 17), 6 months (n = 8), and 14 months (n = 7).

Antibodies to the following 17 pneumococcal protein antigens were used: PspC (CbpA), choline-binding protein A; Eno, enolase; Hyl, hyaluronidase; IgA1 protease, immunoglobulin A1 protease; NanA, neuraminidase; PLY, pneumolysin; PdBD, a double mutant of pneumolysin; PmpA, putative proteinase maturation protein A; PsaA, pneumococcal surface adhesin A; PspA, pneumococcal surface protein A; the pneumococcal histidine triad (Pht) family (BVH-3 and SP1003); SlrA, streptococcal lipoprotein rotamase; SP, Streptococcus pneumoniae proteins; SP0189 (hypothetical protein), SP0376 (response regulator, intracellular location), SP1633 (response regulator, intracellular location) and SP1651 (thiol peroxidase, intracellular location). Antibodies to the following 19 staphylococcal proteins were used: CHIPS, chemotaxis inhibitory protein of S. aureus; ClfA and ClfB, clumping factors A and B, respectively; Efb, extracellular fibrinogen-binding protein; FnbpA and FnbpB, fibronectin-binding proteins A and B, respectively; IsdA and IsdH, iron-responsive surface determinants A and H, respectively; Sas, S. aureus surface protein; SCIN, staphylococcal complement inhibitor; SdrD and SdrE, serine-aspartate repeat proteins D and E, respectively; SEA, SEB, SEI, SEM, SEO, and SEQ, staphylococcal enterotoxins A, B, I, M, O, and Q, respectively; TSST-1, toxic shock syndrome toxin 1.

Values that we consider statistically significantly different from basic prevalence values are indicated as follows: *, P value of 0.05.

We were not able to detect an association between serum levels of IgG at 6 months and colonization status at 6 and 14 months (data not shown). To avoid a mixture of maternal antibodies with antibodies produced by the child him- or herself, we explicitly studied levels of IgG at 14 months to assess the effects of antibodies produced by the child on colonization. No significant association was seen for antistaphylococcal antibodies at 14 months with pneumococcal colonization at 14 months and antipneumococcal antibodies with S. aureus colonization at the same age (data not shown). Moreover, no significant association was observed for differences in IgA levels at 6 and 14 months for both antistaphylococcal and antipneumococcal antibodies on subsequent colonization. In addition, we analyzed the correlation between S. aureus and pneumococcal colonization in this particular study population. We did not observe a significant correlation between the two pathogens at 1.5, 6, and 14 months. However, the odds ratios at 1.5 and 14 months are directed to an inverse correlation (odds ratio [OR] of 0.26 and 95% confidence interval [95% CI] of 0.04 to 1.55 and OR of 0.18 and 95% CI of 0.02 to 1.55, respectively), in contrast to the correlation at 6 months (OR of 1.64 and 95% CI of 0.33 to 8.02).

We assessed the effect of the humoral immune response on the inverse correlation between S. aureus and S. pneumoniae, which significantly adds to the discussion on determinants of the inverse correlation that have been reported for these two species. A recently published study revealed that the antistaphylococcal IgG, IgA, and IgM levels show large interindividual variability in healthy infants from the same cohort as the present study. The levels of antistaphylococcal IgA and IgM increase from birth until the age of 2 years, whereas the levels of antistaphylococcal maternal IgG decrease. These placentally transferred maternal IgG antibodies do not protect against nasal staphylococcal colonization. Several antistaphylococcal antibodies (e.g., those directed against CHIPS, Efb, IsdA, and IsdH) seemed to play a role in nasal colonization of young children (18). In the current study, we investigated whether the levels of systemically produced IgG and IgA against staphylococcal and pneumococcal antigens are correlated to later colonization with the other pathogen. In infancy, neither a positive nor negative effect of antipneumococcal and antistaphylococcal IgG and IgA was seen on S. aureus and pneumococcal colonization, respectively. We hypothesized that an increased level of specific antipneumococcal antibodies (following clinical or subclinical infection) reflects prior pneumococcal colonization and thus decreases the risk for S. aureus colonization. However, no such cross-protectiveness by antipneumococcal antibodies on S. aureus colonization seems to exist and vice versa. On the other hand, one can hypothesize that increased levels of specific antipneumococcal antibodies protect children from pneumococcal colonization and infection and therefore increase the risk of S. aureus colonization. No such association was seen either. In this sample, no significant negative association between S. aureus and pneumococcal colonization can be observed. However, at 1.5 and 14 months, a nonsignificant trend toward an inverse correlation was found.

In conclusion, our study aimed to explore the etiology and immunological effects of the negative association between S. aureus and pneumococcal colonization. We found no role for the early specific humoral immune response against S. aureus and pneumococcal protein antigens.

Acknowledgments

The Generation R Study is conducted by the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands, in close collaboration with the School of Law and Faculty of Social Sciences of Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Municipal Health Service Rotterdam area, the Rotterdam Homecare Foundation, and the Stichting Trombosedienst & Artsenlaboratorium Rijnmond (STAR), Rotterdam, Netherlands. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of general practitioners, hospitals, midwives, and pharmacies in Rotterdam, Netherlands. We thank Ad Luijendijk for technical supervision at the Department of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

The first phase (until the last children turn 4 years old) of the Generation R Study was made possible by financial support from the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands, from the Erasmus University Rotterdam, and from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (Zon Mw). Additionally, an unrestricted grant from the ECT-Rotterdam funded this project.

None of the authors has any conflict of interest, nor do they have anything to disclose.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bisgaard, H., et al. 2007. Childhood asthma after bacterial colonization of the airway in neonates. N. Engl. J. Med. 357:1487-1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogaert, D., R. De Groot, and P. W. Hermans. 2004. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization: the key to pneumococcal disease. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4:144-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogaert, D., et al. 2004. Colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus in healthy children. Lancet 363:1871-1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borgers, H., et al. 2010. Laboratory diagnosis of specific antibody deficiency to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide antigens by multiplexed bead assay. Clin. Immunol. 134:198-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaddoe, V. W., et al. 2008. The Generation R Study: design and cohort update until the age of 4 years. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 23:801-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Labout, J. A., et al. 2008. Factors associated with pneumococcal carriage in healthy Dutch infants: the generation R study. J. Pediatr. 153:771-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebon, A., et al. 2008. Dynamics and determinants of Staphylococcus aureus carriage in infancy: the Generation R Study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3517-3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lebon, A., et al. 2009. Role of Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization in atopic dermatitis in infants: the Generation R Study. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 163:745-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lebon, A., et al. 2010. Correlation of bacterial colonization status between mother and child: the Generation R Study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:960-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melles, D. C., et al. 2007. Nasopharyngeal co-colonization with Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae in children is bacterial genotype independent. Microbiology 153:686-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regev-Yochay, G., et al. 2008. Does pneumococcal conjugate vaccine influence Staphylococcus aureus carriage in children? Clin. Infect. Dis. 47:289-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regev-Yochay, G., et al. 2004. Association between carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus in children. JAMA 292:716-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regev-Yochay, G., et al. 2009. The pneumococcal pilus predicts the absence of Staphylococcus aureus co-colonization in pneumococcal carriers. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:760-763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Regev-Yochay, G., K. Trzcinski, C. M. Thompson, R. Malley, and M. Lipsitch. 2006. Interference between Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus: in vitro hydrogen peroxide-mediated killing by Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 188:4996-5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shoma, S., et al. 18 November 2010, posting date. Development of a multiplexed bead-based immunoassay for the simultaneous detection of antibodies to 17 pneumococcal proteins. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. [Epub ahead of print.] doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1113-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Veenhoven, R., et al. 2003. Effect of conjugate pneumococcal vaccine followed by polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine on recurrent acute otitis media: a randomised study. Lancet 361:2189-2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verkaik, N. J., et al. 2009. Anti-staphylococcal humoral immune response in persistent nasal carriers and noncarriers of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 199:625-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verkaik, N. J., et al. 2010. Induction of antibodies by Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization in young children. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:1312-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wertheim, H. F., et al. 2005. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5:751-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]