Abstract

σD proteins from Aeribacillus pallidus AC6 and Bacillus subtilis bound specifically, albeit weakly, to promoter DNA even in the absence of core RNA polymerase. Binding required a conserved CG motif within the −10 element, and this motif is known to be recognized by σ region 2.4 and critical for promoter activity.

In the course of efforts to define gene expression determinants from the thermophilic bacterium Aeribacillus pallidus AC6 (2, 18), we identified flagellin (Hag) as being among the most highly expressed proteins in this strain. To determine the basis for high-level Hag expression, we isolated and sequenced the hag gene and identified and expressed the protein required for its expression in this organism, σD (σDAp). We here describe a comparison of σDAp with its ortholog from B. subtilis (σDBs).

Cloning and sequencing of the hag and sigD genes of A. pallidus AC6.

SDS-PAGE analysis of whole-cell lysates from A. pallidus AC6 identified an abundant ∼35-kDa protein. The excised protein was sent to the Center of Advanced Proteomics Research Laboratory (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey) for tryptic digestion and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) analyses. The resulting peptide sequences displayed high similarity to B. subtilis flagellin (NAQDGISLIQTAEGALTETHAILQR had 96% identity with amino acids [aa] 65 to 89 and LEHTINNLGTSAENLTAAESR had 85% identity with aa 242 to 262). Two degenerate primers (FlaF1 and FlaR1) were used to amplify the flagellin gene (hag) from A. pallidus AC6 chromosomal DNA. An ∼450-bp product was cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega) for DNA sequencing. The remainder of hag and its upstream region were obtained by inverse PCR. The 828-bp hag gene encodes a 275-amino-acid (29.7-kDa) protein having 63% identity with B. subtilis Hag and is preceded by a typical σD promoter.

To identify sigD, two degenerate primers were used to amplify a PCR fragment which was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector system and sequenced. The flanking portions of sigD were obtained by inverse PCR, and the gene was sequenced. The 771-bp sigD gene encodes a 256-amino-acid (28.7-kDa) protein having 67% overall identity with σDBs, with the highest levels of similarity concentrated in conserved regions 2 and 4, known to mediate promoter recognition.

A. pallidus AC6 flagellin is expressed from a σD-dependent promoter.

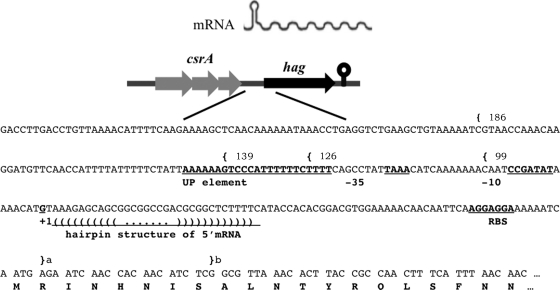

Transcription of hag initiates from a canonical σD-dependent promoter at a G residue 79 bp upstream of the start codon (Fig. 1). Analysis of hag::lacZ fusions integrated into B. subtilis CU1065 and HB4035 (sigD::kan) indicated that activity was σD dependent and highest at late logarithmic phase, as previously reported for B. subtilis (19). Optimal promoter activity required an AT-rich region just upstream of the −35 element (Table 1), which has similarity with the upstream promoter (UP) element previously described for B. subtilis hag (6). Sequence inspection suggests that high-level Hag expression may also benefit from a strong ribosome-binding site and stabilization of the mRNA by a 5′ hairpin sequence (24).

FIG. 1.

The A. pallidus hag regulatory region. The hag gene is predicted to be transcribed as a monocistronic mRNA with a 5′ stem-loop (top). The regulatory region includes a predicted UP element and recognition signals (−35 and −10) for σD RNAP. The start site in A. pallidus AC6 was determined by 5′-RACE from RNA isolated from cells grown in LB medium at 60°C with shaking and corresponds to the indicated G (+1). The ribosome-binding site (RBS) and initial coding sequence are indicated. For expression studies (Table 1), promoter-lacZ fusions were generated from the indicated upstream endpoints ({) and either of the two downstream endpoints, designated a and b (}).

TABLE 1.

β-Galactosidase activity in B. subtilis CU1065 containing various hag::lacZ promoter fusions integrated into the thrC locusa

| Promoter construct | Extent of promoter DNA (positions) |

B. subtilis CU1065 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) | % activity | ||

| hag185 | −186 to +22 | 1,016 ± 49 | 100 |

| hag138a | −139a to +22 | 914 ± 99 | 89.9 |

| hag138b | −139b to +4 | 909 ± 63 | 89.4 |

| hag117a | −126a to +22 | 65 ± 10 | 6.4 |

| hag117b | −126b to +4 | 63 ± 15 | 6.2 |

| hag98 | −99 to +22 | 0 | 0 |

| hag56 | −57 to +22 | 0 | 0 |

Purification σD of A. pallidus and B. subtilis and reconstitution of σD RNAP.

σD proteins from A. pallidus AC6 and B. subtilis were expressed under T7 RNA polymerase (RNAP) control in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS (Novagen) by using pECG1 and pECB1 (Table 2). For purification, inclusion bodies were solubilized with Sarkosyl (1), refolded, and purified using DEAE-Sepharose and heparin-Sepharose chromatography as described previously (9). B. subtilis core RNAP was purified from a sigD-null mutant expressing a His6-tagged β′ subunit (strain EC3) by using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) chromatography (USB) and heparin-Sepharose chromatography (Pharmacia fast protein liquid chromatography [FPLC] system) and used to reconstitute σD holoenzymes (9). Both the σDAp and σDBs holoenzymes accurately and efficiently recognized the A. pallidus hag promoter on plasmid pEC3 as judged by both start site mapping (5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends [5′-RACE]) and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Description or relevant characteristicsa | Reference, source, or purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtilis | ||

| CU1065 | W168 trpC2 attSPβ | Lab stock |

| HB4035 | CU1065 sigD::kan | Lab stock |

| HB7707 | JH642 trpC2 pheA1 rpoC::His6 Spcr | Lab stock |

| EC3 | HB4035 rpoC::His6 Sptr Kanr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDG1663 | Integrational plasmid (inserts at thrC locus) | 8 |

| pECG1 | pET11a carrying sigD gene of A. pallidus AC6 | This study |

| pECB1 | pET11a carrying sigD gene of B. subtilis CU1065 | This study |

| pEC3 | pDG1663 containing hag promoter from −185 to +385 from start codon | This study |

| pEC3-185 series | Series of pDG1663 derivatives with truncated hag promoters as EcoRI-HindIII fragments (suffix indicating the upstream endpoint) | |

| Primers | ||

| FlaF1 | GCNGGNGAYGAYGCNGCNGGNYTNGC | hag (degenerate) |

| FlaR1 | GTNCCNARRTTRTTDATNGTRTGYTC | hag (degenerate) |

| SigDF2 | AARTTYGAYACNTAYGCNTCNTTYMG | sigD (degenerate) |

| SigDR2 | GMRTGDATYTGNGADATNCKNGANGTNG | sigD (degenerate) |

| Gpa sigDf | TATCACCATATGATGGTCCAATCGATGACACTG | Cloning into pET11a |

| Gpa sigDr | TATGGATCCTTAAGATAAAAGCTTAACGAGC | Cloning into pET11a |

| Bsu sigDf | TATCACCATATGATGCAATCCTTGAATTATGAAG | Cloning into pET11a |

| Bsu sigDr | TATGGATCCTTATTGTATCACTTTTTCCAGC | Cloning into pET11a |

Italics indicates a restriction site. Sptr, spectinomycin resistant; Kanr, kanamycin resistant.

Binding affinity of σD of RNAP for the hag promoter.

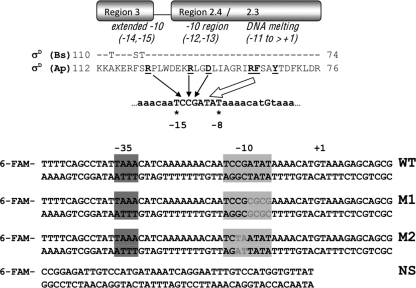

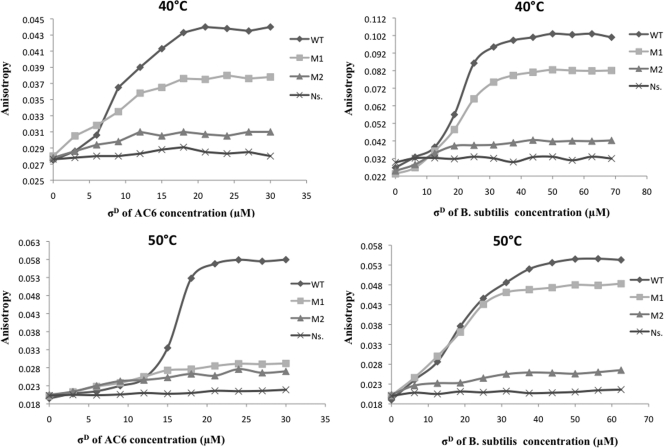

We have previously shown that σDBs recognizes promoter DNA in vitro in the absence of core RNAP, as judged by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and chemical footprinting (4). We here compared the DNA-binding abilities of σDAp and σDBs by using a fluorescence anisotropy-based assay with specific duplex oligonucleotides corresponding to the A. pallidus AC6 hag promoter and a control, nonspecific duplex (Fig. 2). Specific binding of σDAp and σDBs was apparent at several tested temperatures (Fig. 3And data not shown). The observed affinities were relatively low (dissociation constant [Kd], ∼10 to 20 μM) compared with those reported for truncated primary σ factors (5), but the specificities of the interactions were high. Previously, a somewhat higher affinity (Kd, ∼1 μM) was estimated for σDBs by using EMSA with a different labeled promoter fragment (4).

FIG. 2.

Promoter recognition by σD proteins. The −35 region is recognized by region 4.3 (not shown), and the −10 element is recognized by region 2 and an Arg residue from the amino terminus of region 3 (14). The σDAp and σDBs proteins are aligned from the initial portion of region 3 through region 2.3 (note that the direction of the protein sequences is inverted relative to conventional orientation). There are only three amino acid substitutions in this region (identical residues are indicated by dashes) and all residues known to contact DNA are identical. The underlined residues implicated in sequence specific promoter recognition include (σDAp numbering) R104 in region 3 and R97 and D94 in region 2.4. Residues in region 2.3 corresponding to positions involved in promoter melting in other σ factors are also underlined (15). Fluorescently labeled (6-carboxyfluorescein [6-FAM]) oligonucleotide duplexes were used for fluorescence anisotropy analysis of σ-DNA interactions. The −35 and −10 elements are shaded, and the substituted bases are highlighted. +1 indicates the start site for transcription. WT indicates the wild type. M1 and M2 are mutants with mutations in the core −10 element, and NS represents a nonspecific control DNA.

FIG. 3.

DNA binding by purified σD proteins monitored by fluorescence anisotropy (FA). σD proteins were added stepwise from 0 to 60 μΜ, and DNA binding was detected as an increase in anisotropy of the probe DNA. Probe DNA was a 50-bp 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM)-labeled hag duplex oligonucleotide (Fig. 2) or a variant altered in the −10 region (M1 [from TCCGATAT to TCCGCGCG] and M2 [from TCCGATAT to TCTAATAT] [substitutions are underlined]). FA experiments (excitation wavelength [λex], 492 nm [slit width = 10 nm]; emission wavelength [λem], 492 nm [slit width = 15 nm]) were performed at 40 or 50°C in 100 μl TGED buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]) with 100 nM DNA and 50 mM NaCl. Averages of 6 measurements with an integration time of 9 s were determined.

We tested two duplexes with changes within the −10 TCCGATAT consensus (M1 [TCCGCGCG] and M2 [TCTAATAT] [substitutions are underlined]; Fig. 2). Remarkably, the M2 mutation drastically affected binding by both σ factors, indicating that the CG bases within the −10 element are critical for recognition and binding. This is consistent with mutational studies demonstrating that the CG motif is critical for −10 element function (14, 28, 30). Even though M1 represents a more drastic change in sequence (a 4-bp substitution), this had a more modest effect on binding, particularly when tested with σDBs. However, a significant decrease in affinity for σDAp was observed at elevated temperatures (Fig. 3).

Concluding remarks.

Recognition of flagellin promoters by σD orthologs is conserved across distantly related species (3, 11, 27). We here demonstrate this conservation for A. pallidus; the hag promoter, like that in B. subtilis (6), is σD dependent and appears to include a strong UP element.

As a class, isolated σ factors are often considered to have little if any affinity for promoter DNA despite the fact that recognition of both the −35 and −10 elements involves specific σ-DNA contacts (7). DNA binding by primary σ factors (e.g., σ70) can be revealed by removal of an amino-terminal domain (region 1) thought to allosterically mask the DNA-binding determinants (5). However, many alternative σ factors lack region 1, and a different mechanism of self-inhibition likely pertains. Indeed, solution studies suggest a predominant σ conformation incompatible with DNA binding (22, 25). For σD, structural analysis of a σD::FlgM complex revealed a compact σ conformation with the two DNA-binding domains (regions 2 and 4) closely apposed (26). Disulfide cross-linking suggests that a similarly compact conformation predominates in solution (25). Conversely, other studies support the idea that σ factors may specifically recognize elements of the promoter even in the absence of core RNA polymerase (12, 16, 23). We suggest that there is an equilibrium between the compact conformation, unable to interact specifically with DNA, and a more open conformation in which specific DNA binding is possible.

The −10 element is highly conserved in σD promoters. The GCCG motif is a composite recognition element: the GC is recognized by R91 from region 3 of E. coli σ28 (the σD ortholog), whereas the CG is recognized by R84 and D81 from region 2.4 (14). The corresponding residues in σDAp are R104 from region 3 and R97 and D94 from region 2.4. E. coli σ28 R91 recognizes a G residue at either of the first two positions of the extended −10 element (15), and σDAp R104 is therefore predicted to contact G on the template strand at position −14 (Fig. 2). The neighboring AT-rich motif (ATAT) likely functions in DNA melting, presumably via interaction with region 2.3 (13, 15). In general, it is not yet known whether the downstream portion of the −10 element is recognized as duplex DNA or whether this region establishes close interactions with σ only after promoter melting. For nearly all σ factors, this region is AT rich (and often includes alternating AT residues). Since it is unlikely that σ factor alone can melt DNA (29), this may explain the relatively modest effects of the substitutions in M1 on binding by σDBs. Conversely, the notable effect of the M1 substitution on DNA binding by σDAp at elevated temperatures hints that duplex recognition of this region may also play a role.

In sum, these results suggest that σD proteins may prove to be a useful model system for investigation of σ-DNA recognition. Despite recent progress in RNAP structural biology (reviewed in reference 20), we still lack a high-resolution view of key transcription intermediates in open-complex formation. Development of simplified model systems is one promising approach for dissecting the interactions that occur during transcription initiation (10, 23, 29).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The hag and sigD gene sequences have been submitted to GenBank under accession numbers GU991850 and HM126480, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a fellowship from the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (Tubitak) to E.S. and a grant from the NIH (GM047446) to J.D.H.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burgess, R. R. 1996. Purification of overproduced Escherichia coli RNA polymerase sigma factors by solubilizing inclusion bodies and refolding from Sarkosyl. Methods Enzymol. 273:145-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canakci, S., K. Inan, M. Kacagan, and A. O. Belduz. 2007. Evaluation of arabinofuranosidase and xylanase activities of Geobacillus spp. isolated from some hot springs in Turkey. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 17:1262-1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, Y. F., and J. D. Helmann. 1992. Restoration of motility to an Escherichia coli fliA flagellar mutant by a Bacillus subtilis sigma factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:5123-5127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, Y. F., and J. D. Helmann. 1995. The Bacillus subtilis flagellar regulatory protein σD: overproduction, domain analysis and DNA-binding properties. J. Mol. Biol. 249:743-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dombroski, A. J., W. A. Walter, M. T. Record, Jr., D. A. Siegele, and C. A. Gross. 1992. Polypeptides containing highly conserved regions of transcription initiation factor sigma 70 exhibit specificity of binding to promoter DNA. Cell 70:501-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fredrick, K., T. Caramori, Y. F. Chen, A. Galizzi, and J. D. Helmann. 1995. Promoter architecture in the flagellar regulon of Bacillus subtilis: high-level expression of flagellin by the sigma D RNA polymerase requires an upstream promoter element. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:2582-2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gruber, T. M., and C. A. Gross. 2003. Multiple sigma subunits and the partitioning of bacterial transcription space. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:441-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guérout-Fleury, A. M., N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1996. Plasmids for ectopic integration in Bacillus subtilis. Gene 180:57-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helmann, J. D. 2003. Purification of Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase and associated factors. Methods Enzymol. 370:10-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helmann, J. D., and P. L. deHaseth. 1999. Protein-nucleic acid interactions during open complex formation investigated by systematic alteration of the protein and DNA binding partners. Biochemistry 38:5959-5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heuner, K., J. Hacker, and B. C. Brand. 1997. The alternative sigma factor σ28 of Legionella pneumophila restores flagellation and motility to an Escherichia coli fliA mutant. J. Bacteriol. 179:17-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imashimizu, M., M. Hanaoka, A. Seki, K. S. Murakami, and K. Tanaka. 2006. The cyanobacterial principal sigma factor region 1.1 is involved in DNA-binding in the free form and in transcription activity as holoenzyme. FEBS Lett. 580:3439-3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juang, Y. L., and J. D. Helmann. 1994. A promoter melting region in the primary sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis. Identification of functionally important aromatic amino acids. J. Mol. Biol. 235:1470-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koo, B. M., V. A. Rhodius, E. A. Campbell, and C. A. Gross. 2009. Mutational analysis of Escherichia coli σ28 and its target promoters 'reveals recognition of a composite −10 region, comprised of an ′extended −10′ motif and a core −10 element. Mol. Microbiol. 72:830-843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koo, B. M., V. A. Rhodius, G. Nonaka, P. L. deHaseth, and C. A. Gross. 2009. Reduced capacity of alternative sigmas to melt promoters ensures stringent promoter recognition. Genes Dev. 23:2426-2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kudo, T., D. Jaffe, and R. H. Doi. 1981. Free sigma subunit of Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase binds to DNA. Mol. Gen. Genet. 181:63-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics, p. 352-355. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 18.Minana-Galbis, D., D. L. Pinzon, J. G. Loren, A. Manresa, and R. M. Oliart-Ros. Reclassification of Geobacillus pallidus (Scholz et al. 1988) Banat et al. 2004 as Aeribacillus pallidus gen. nov., comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 60:1600-1604. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Mirel, D. B., et al. 2000. Environmental regulation of Bacillus subtilis σD-dependent gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 182:3055-3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murakami, K. S., and S. A. Darst. 2003. Bacterial RNA polymerases: the wholo story. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13:31-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaeffer, P., J. Millet, and J. P. Aubert. 1965. Catabolic repression of bacterial sporulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 54:704-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz, E. C., et al. 2008. A full-length group 1 bacterial sigma factor adopts a compact structure incompatible with DNA binding. Chem. Biol. 15:1091-1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sevostyanova, A., et al. 2007. Specific recognition of the −10 promoter element by the free RNA polymerase sigma subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 282:22033-22039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharp, J. S., and D. H. Bechhofer. 2005. Effect of 5′-proximal elements on decay of a model mRNA in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 57:484-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorenson, M. K., and S. A. Darst. 2006. Disulfide cross-linking indicates that FlgM-bound and free σ28 adopt similar conformations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:16722-16727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorenson, M. K., S. S. Ray, and S. A. Darst. 2004. Crystal structure of the flagellar sigma/anti-sigma complex σ28/FlgM reveals an intact sigma factor in an inactive conformation. Mol. Cell 14:127-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Studholme, D. J., and M. Buck. 2000. The alternative sigma factor σ28 of the extreme thermophile Aquifex aeolicus restores motility to an Escherichia coli fliA mutant. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 191:103-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wozniak, C. E., and K. T. Hughes. 2008. Genetic dissection of the consensus sequence for the class 2 and class 3 flagellar promoters. J. Mol. Biol. 379:936-952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young, B. A., T. M. Gruber, and C. A. Gross. 2004. Minimal machinery of RNA polymerase holoenzyme sufficient for promoter melting. Science 303:1382-1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu, H. H., E. G. Di Russo, M. A. Rounds, and M. Tan. 2006. Mutational analysis of the promoter recognized by Chlamydia and Escherichia coli σ28 RNA polymerase. J. Bacteriol. 188:5524-5531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]