Abstract

cis-acting elements found in 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs) are regulatory signals determining mRNA stability and translational efficiency. By binding a novel non-AU-rich 69-nucleotide (nt) c-fms 3′ UTR sequence, we previously identified HuR as a promoter of c-fms proto-oncogene mRNA. We now identify the 69-nt c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR sequence as a cellular vigilin target through which vigilin inhibits the expression of c-fms mRNA and protein. Altering association of either vigilin or HuR with c-fms mRNA in vivo reciprocally affected mRNA association with the other protein. Mechanistic studies show that vigilin decreased c-fms mRNA stability. Furthermore, vigilin inhibited c-fms translation. Vigilin suppresses while HuR encourages cellular motility and invasion of breast cancer cells. In summary, we identified a competition for binding the 69-nt sequence, through which vigilin and HuR exert opposing effects on c-fms expression, suggesting a role for vigilin in suppression of breast cancer progression.

RNA binding proteins, together with noncoding regulatory RNAs, are now recognized to coordinate both mRNA stability and translation (36). After translocation to the cytoplasm, mRNAs associate with a translation initiation complex (42) or the exosome (9), including P bodies which contain proteins which function in mRNA metabolism and possibly microRNA-mediated translational repression (2, 42). In these P bodies, mRNAs are either degraded or reenter the translating pool. During this process, RNA binding proteins play an important role in guiding mRNAs to proper subcellular locations and in determining RNA stability and half-life (17). It is estimated that more than 50% of genes are regulated on the basis of mRNA stability by RNA binding proteins (10). Many posttranscriptional events are regulated by sequences in the 3′-untranslated region (3′ UTR). Binding of RNA binding proteins to cis-acting mRNA elements can either protect the mRNA from RNase cleavage (e.g., HuR [14]) or promote degradation (e.g., TTP [21], AUF1 [28, 39]) and thereby mediate many of the phenotypic changes related to 3′ UTR expression. For example, HuR, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling protein, stabilizes ARE-containing mRNAs. In contrast, TTP and AUF1 enhance mRNA decay by recruiting the cellular mRNA decay machinery to ARE-containing mRNAs.

Both 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR RNA binding proteins are also involved in translational regulation (34), with some of these multifunctional proteins playing a role in regulating both mRNA turnover and translation (37). mRNA circularization (or closed-loop formation) is proposed to play a key role in the regulation of translation initiation (1). In a closed-loop mRNP model, some RNA binding proteins block the closed-loop formed by interaction of 5′ and 3′ UTR complexes, thereby repressing translation (19).

The K-homology (KH) domain protein family member KSRP binds AREs and enhances degradation of ARE-containing mRNAs by recruiting the degradation machinery (18). In contrast, the KH protein family member vigilin known as the high-density lipoprotein-binding protein (16, 35) contains 15 tandemly arranged KH domains for RNA binding (18), binds to the non-ARE-containing Xenopus vitellogenin mRNA 3′ UTR (13), and stabilizes its mRNA. In human cells, vigilin was found in a multiprotein complex including translation elongation factors and tRNA and is proposed to transport this multiprotein complex from nucleus to cytosol (27). The yeast vigilin homolog Scp160p was found in polysome-bound mRNP complexes which also include PABPs (29). This suggests a role for vigilin in regulation of mRNA metabolism and translation.

We have studied the proto-oncogene c-fms for many years. The c-fms proto-oncogene encodes a cell surface receptor tyrosine kinase which functions as the sole receptor for the macrophage colony-stimulating factor (CSF-1) (12, 41). c-fms is expressed by the tumor epithelium in several human epithelial cancers (5, 8, 22). Activation and overexpression of c-fms in breast cancer confer invasive and metastatic properties (32, 44). In human breast cancer, c-fms expression was observed in both in situ and invasive lesions (22). In a large-cohort breast cancer tissue array, expression of c-fms is strongly associated with lymph node metastasis and poor survival of breast cancer patients (26).

The expression of c-fms is regulated at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels (7, 38). Previously we reported that in low-physiologic glucocorticoid (GC) conditions nearly all breast carcinomas express low levels of c-fms in vivo and that c-fms expression is dramatically upregulated by GCs in breast cancer cells in vitro and in breast cancer metastasis in vivo (6, 7, 22, 44). This finding is important from a translational context, because endogenous circulating physiologic levels of GCs stimulate c-fms in breast cancer cells, leading to invasiveness and metastasis.

We recently demonstrated HuR binding to a 69-nucleotide (nt) sequence in the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR (46). This 69-nt sequence does not contain conserved AREs or U-rich regions (33) but contains five “CUU” motifs. Silencing HuR decreased reporter RNA and protein activity only in the presence of the wild-type and not in the mutant 69-nt 3′ UTR c-fms sequence. Thus, posttranscriptional regulation of c-fms by HuR is dependent on a non-AU-rich 69-nt sequence in the 3′ UTR of c-fms mRNA. Furthermore, we showed that GC stimulation of c-fms mRNA and protein to be largely dependent on HuR's presence. However, the identity of other critical c-fms mRNA regulatory proteins remains unknown.

In this report, we show that vigilin also binds to the same 69-nt sequence in the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR to which HuR binds. We add to previous reports about vigilin's role in mRNA stabilization (11) by describing for the first time vigilin's role in mRNA decay and downregulation of translation, specifically of the c-fms target. We show that downregulation of vigilin results in increased expression of c-fms mRNA and protein. Vigilin overexpression reduces the level of c-fms mRNA and also suppresses translation of c-fms mRNA. Our study indicates that vigilin and HuR compete for the same 69-nt sequence in the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR and that dynamic changes in the ratio of vigilin to HuR can influence their ability to associate with the c-fms mRNA and posttranscriptionally regulate cellular c-fms levels. In addition, directed motility and invasion assays using human breast cancer cell lines show that HuR increases while vigilin suppresses cellular motility and invasion. This is the first demonstration that vigilin functions as a repressor of c-fms expression at the posttranscriptional and translational levels in GC-stimulated breast cancer cells. Our work also suggests that vigilin may have a role in cancer by functioning as a tumor repressor through competing with HuR for binding to a novel 69-nt non-ARE-containing 3′ UTR sequence in c-fms mRNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and protein fractionation.

BT20 cells, a human breast carcinoma cell line that constitutively expresses low levels of c-fms, were maintained in minimal essential medium (MEM) (Sigma) supplemented with 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1.5 g/liter sodium bicarbonate, and 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen) in 5% CO2 at 37°C. SKBR3, human breast carcinoma cells expressing c-fms, were cultured in McCoy's modified 5A (Mediatech) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. MDA-MB-231 parent and MDA-MB-231BO (a bone-metastatic derivative line of MDA-MB-231, kindly provided by T. Yoneda, University of Texas, San Antonio), human breast carcinoma cells, were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Mediatech) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. For studies using glucocorticoids, cells were grown in starvation medium with 100 nM dexamethasone (Dex) (Sigma-Aldrich). When the cultures reached 75 to 80% confluence, they were starved in serum-free DMEM/F12 Ham medium (Sigma-Aldrich) for 72 h, washed twice in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) (Invitrogen), and collected with a cell scraper. Total cellular protein extract was prepared from cells using 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Igepal (Sigma-Aldrich), and protease inhibitor cocktail set 1 at 1:100 dilution (Calbiochem). Protein concentrations were determined by BCA assay (Pierce).

RNA affinity chromatography and protein identification.

Cyanogen bromide (CNBr)-activated Sepharose 4B (GE-Pharmacia) was freshly prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. A 300-μg sample of RNA transcribed from 218 nt of c-fms (nt 3415 to 3632) in pCRII plasmid (46) was mixed with 200 mg CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B overnight at 4°C with rotation. The next morning, unreacted groups on the CNBr-activated Sepharose were blocked by 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, and equilibrated in binding buffer (20 mmol/liter HEPES [pH 7.6], 5 mmol/liter MgCl2, 200 mmol/liter KCl, 2 mmol/liter dithiothreitol [DTT], 5% glycerol). Total protein was prepared from 100 nM Dex-treated, starved BT20 cells. This sample was subjected to RNA affinity chromatography as described by Kaminski et al. (23). Briefly, the treated cells were washed twice with cold PBS and scraped off the plate using the binding buffer. The cells were sonicated and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was passed through a heparin column and then used for RNA affinity chromatography. One mg of cell lysate was mixed with 200 mg of RNA-coupled CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B and incubated at 4°C for 1 h with rotation. The beads were washed with 20 ml of the binding buffer and then boiled with SDS-PAGE loading buffer to release captured proteins, which were then resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. The proteins were silver stained with a mass spectrometry compatible kit (Invitrogen) and the 150-kDa band was excised for mass spectrometry analysis. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed in the Taplin Biological Mass Spectrometry Facility, Harvard Medical School. In-gel trypsin-digested protein bands were analyzed using a quadrupole ion trap ThermoFinnigan LCQ DECA XP PLUS equipped with a Michrom Paradigm MS4 high-performance liquid chromatographer (HPLC) and a nanoelectrospray source. All spectra were searched by the database-searching program Sequest along with manual inspection of the data.

Analysis of c-fms mRNA half-life.

To determine c-fms mRNA half-life in BT20 cells in resting conditions in the absence of Dex, total cellular RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen). For actinomycin D (Act D) chase experiments, 2 μg/ml of Act D (Sigma) was added to inhibit new transcription. Cells were harvested at 0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 18 h, 24 h, 30 h, and 36 h after Act D treatment, total RNA was extracted, and c-fms mRNA and tRNAGlu levels were analyzed by reverse transcription-quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). c-fms mRNA half-lives were calculated after qRT-PCR and normalized to tRNAGlu signals, values were plotted on a logarithmic scale, and the time period required for a given transcript to decrease to one-half of the initial abundance was calculated.

c-fms mRNA half-life was also determined in 100 nM Dex-treated BT20 cells which were transfected with either HuR shRNA (Origene), control shRNA (Origene), QC-CMV-Flag-vigilin (11), or control pCMV-Flag (Sigma) for 72 h to 96 h. Cells were harvested at 0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 18 h, 24 h, 30 h, and 36 h after Act D treatment, total RNA was extracted, and c-fms mRNA and tRNAGlu levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Three independent experiments were performed.

Polyribosme profile assay.

Polysome profiling was modified from the methods of Bor et al. (3) and Li et al. (30). A sucrose gradient was constituted by adding 2 ml each of 47, 37, 27, 17, and 7% sucrose solution (75 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 μg/ml cycloheximide) from bottom to top in a polyallomer centrifuge tube (Beckman). The layered sucrose solutions were kept at 4°C overnight to generate a continuous sucrose gradient. Parent or transfected BT20 and SKBR3 cells were cultured in 10-cm petri dishes to 75 to 80% confluence with 100 nM Dex. Before harvest, cells were treated with 100 μg/ml cycloheximide for 15 min and then washed with cold PBS containing 100 μg/ml cycloheximide two times. For each sample, cells from two 10-cm plates were scraped in PBS and pooled together. After centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 5 min, the pellets were dissolved in 500 μl lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1.25% Triton X-100, 2.5% Tween 20, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1× protease inhibitors [Roche], 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 200 U RNase inhibitor [Fermentas], 100 μg/ml cycloheximide) and incubated in ice for 10 min. The homogenized solutions were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C for 5 min. The supernatants were collected and measured by BCA reagent (Bio-Rad). Three milligrams of protein samples was loaded onto the top of the sucrose gradient, and the gradient was centrifuged at 39,000 rpm at 4°C for 2 h using a Beckman L7-55 ultracentrifuge. After centrifugation, gradient samples were fractionated 500 μl per fraction and absorbance was monitored at λ = 254 nm. The RNAs of each fraction were extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen). The total RNA concentration of each fraction was measured. The same quantity of RNA from each fraction was reverse transcribed (RT) and subjected to qPCR analysis. For analysis of the relative distributions of c-fms and GAPDH mRNA in polyribosome gradients, CT values from individual fractions 1 to 10 were each subtracted from the CT value from either fraction 1 for c-fms and GAPDH mRNAs, as fraction 1 had the largest CT values (that is, the lowest c-fms and GAPDH mRNA abundances). The resulting ΔCT numbers were converted into fold differences. The abundance of each mRNA as a percentage of the total from all 10 fractions was then calculated. Because GAPDH mRNA is not a binding target of vigilin (unpublished data) or HuR (46), its abundance was used as a control for the estimation of relative distribution of c-fms mRNA in polyribosome gradients after vigilin knockdown or overexpression. For IB, equal volumes (20 μl) of each fraction were electrophoresed through 4-to-15% SDS-PAGE gels.

Gain-of-function and loss-of-function assay.

Plasmids encoding a control short hairpin RNA (shRNA) or shRNA directed against vigilin or HuR were purchased from Origene. The shRNAs correspond to coding regions at nucleotides 614 to 642 (5′-AAGCTCG GAAGGACATTGTTGCTAGACTG-3′) and 829 to 863 (5′-CATGAAGTCTTACTCATCTCTG CCGAGCAGGACAA-3′), respectively, of human vigilin (GenBank BC001179). The shRNAs correspond to coding regions at nucleotides 645 to 673 (5′-GCAGAAGAGGCAATTACCAGTTT CAATGG-3′) and 964 to 992 (5′-CGTTTGGTGCCGTCACCAATGTGAAAGTG-3′), respectively, of human HuR (GenBank NM_001419). An shRNA containing a noneffective 29-nt GFP sequence (TR30003, Origene) was used as a negative control [(−) CTRL]. For RNAi, 5 × 106 cells were transfected with 10 μg shRNA plasmid using Fugene D (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transfected cells were maintained in culture medium for 3 to 4 days to permit knockdown before assays. Knockdown efficiency was assessed by qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis.

For vigilin overexpression, QC-CMV-Flag-vigilin (11) was transfected using Fugene HD (Roche). For HuR overexpression, pHuR-pcDNA3.1 (46) was transfected. The BT20 cells at 75 to 80% confluence in six-well plates were transfected with 5 μg of plasmids. One hour after transfection, 100 nM Dex was added into the medium and the cells were further cultured. The overexpression effects were monitored 72 h and 96 h after transfection by qRT-PCR and Western blot analyses.

In vitro translation.

Luciferase message ligated with either wild-type or mutant c-fms 3′ UTR (776-nt or 69-nt segment) were generated for in vitro translation. Luciferase message was translated for 90 min in 25-μl reactions using 20 μCi [35S]methionine and rabbit reticulocyte lysates (Promega) in the presence or absence of recombinant vigilin. Five microliters of each reaction was run on a 4-to-20% gradient SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad) and exposed to the phosphorimager overnight.

Invasion and motility assay.

The Membrane Invasion Culture System (MICS) chamber was used to quantitate the degree of invasion of MDA-MB-231 and BT20 transiently transfected vigilin or HuR overexpressing or silenced clones. Assay details were similar to those described previously (43) except that breast cancer cells were cultured in the presence of 100 nM Dex and remained under starved conditions for transfection duration prior to the invasion and motility assays. Parent or transfected cells, 1 × 105 per well in a 6-well plate, were seeded onto 10-μm-pore filters coated with a human defined matrix containing 50 μg/ml human laminin, 50 μg/ml human collagen IV, and 2 mg/ml gelatin in 10 mM acetic acid. Similarly, directed motility assays of BT20 cells were performed. Fibronectin (25 μg/ml; Fisher) was added as a chemoattractant in the lower wells of the chamber, above which uncoated 10-μm-pore filters were placed. The numbers of cells which moved to the bottom of the membrane were counted in 15 random fields using a grid. The results were reported as mean percent invasion ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Each experiment was done in triplicate.

Statistical analyses.

Data are depicted as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or mean ± SEM of results from at least three independent experiments. Exact n values are provided in figure legends. The unpaired two-way t test was done using SigmaStat (Jandel Scientific Corp.). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. P values are provided in each figure legend.

RESULTS

Vigilin, a c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR binding protein.

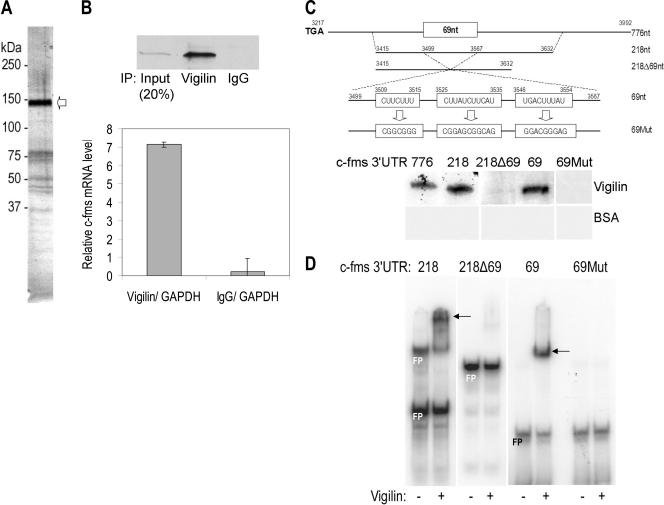

Recently we have reported that, in breast cancer cells, HuR stabilizes c-fms mRNA through its 3′ UTR, which has no conventional ARE elements (46). Because 3′ UTRs confer mRNA stability by interacting with different RNA-binding proteins, we hypothesized that multiple RNA-binding proteins may be involved in the determination of c-fms mRNA half-life. Specifically, we were looking for a destabilizing factor(s) binding to the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR. To this end, through serial biochemical purifications we enriched for c-fms mRNA-binding proteins from extracts of BT20 breast cancer cells cultured in the presence of dexamethasone (Dex) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Since a 218-nt sequence (nt 3415 to 3632) in c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR has been identified for HuR binding, we used a synthetic 218-nt RNA sequence of wild-type c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR to capture RNA-binding proteins from the BT20 cell lysates. After the bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and silver stained, there were at least eight protein bands that were potential c-fms mRNA-binding proteins (Fig. 1A). The most abundant protein (∼150 kDa) was excised and four peptides were identified as vigilin with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS-MS) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 1.

Identification of vigilin as a c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR binding protein. (A) Vigilin (arrow) was identified as one of the proteins binding to the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) LC-MS-MS analysis. (B) Immunoprecipitation of vigilin from SKBR3 cell lysates. IP assays were carried out using SKBR3 cell lysates cultured in the presence of 100 nM Dex using mouse monoclonal anti-human vigilin antibody or IgG. The presence of vigilin in the IP materials was monitored by immunoblotting. qRT-PCR measurements of c-fms mRNA in vigilin immunoprecipitates of SKBR3 cell lysates show direct interaction between vigilin and c-fms mRNA. After IP of RNA-protein complexes from SKBR3 cell lysates, RNA was isolated and used in RT reactions and amplified by real-time PCR. The graph shows relative mRNA levels in vigilin IP compared with control IgG IP conditions. The mean ± SD of c-fms mRNA normalized for GAPDH mRNA is depicted (n = 3). GAPDH mRNA was set to equal 1. (C) In vitro binding assay by UV cross-linking and label transfer of RNA sequences shows vigilin binds to the “CUU” motifs in the c-fms RNA 3′ UTR 69-nt sequence. No binding of 218ntΔ69nt (nt 3415 to 3632 with 69 nt [nt 3499 to 3567] deleted) to recombinant vigilin was detected. Mutations (69Mut, Us to Gs) in the 69-nt sequence abrogated vigilin binding. Bovine serum albumin (BSA), used as a negative control, was not bound to c-fms RNA. (D) Electrophoretic gel mobility shift assay shows recombinant vigilin associates with the c-fms 3′ UTR RNA. The 32P-labeled c-fms riboprobes (218 nt, nt 3415 to 3632; 69 nt, nt 3499 to 3567) from 3′ UTR associated with vigilin and shifted in native PAGE. In contrast, c-fms riboprobes (218ntΔ69nt and 69Mut) did not associate with vigilin. FP, free probe. + and −, presence and absence, respectively, of vigilin.

To determine the distribution of vigilin in breast epithelial cells, four breast cancer cell lines and one nontumorigenic breast cell line (MCF10A) were analyzed by immunoblotting (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). In all cell lines, expression of vigilin was seen in both nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. However, in invasive MDA-MB-231 cells and in particular the bone-metastatic derivative cell line MDA-MB-231BO, the level of vigilin protein was low compared to that in the other breast cancer cells. Interestingly, the vigilin level was high in nuclear fractions of nontumorigenic MCF10A mammary epithelial cells in comparison to that in the breast cancer cells.

Because vigilin was identified as a c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR-binding protein in extracts from human breast cancer cells, and c-fms can be posttranscriptionally regulated, we hypothesized that vigilin may regulate c-fms expression by binding to the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR. To test whether vigilin directly associates with c-fms mRNA in breast cancer cells, immunoprecipitation (IP) assays were performed (Fig. 1B). Association of c-fms mRNA with vigilin was determined by isolating RNA from the IP material and analyzing it by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). As shown in Fig. 1B, in cellular lysates from SKBR3 breast cancer cells, the c-fms mRNA was dramatically enriched in vigilin IP samples compared to that in control IgG IP samples. The association of 3′ UTR c-fms mRNA with vigilin was 33.6-fold higher than that seen in the control IgG IP reaction (Fig. 1B, two-tailed t test, n = 3, P < 0.001). Association of c-fms mRNA with vigilin was also observed in BT20 cells (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

To determine which sequences within the 3′ UTR of c-fms mRNA interact with vigilin, we first used UV cross-linking and label transfer assays. Overall, the 3′ UTR of c-fms (nt 3217 to 3992) is not AU- or U-rich (14). However, in the middle of the c-fms 3′-full-length UTR mRNA (776 nt [nt 3217 to 3992]) five “CUU” motifs are found in the 69-nt sequence (nt 3499 to 3586) which we previously characterized for HuR binding (46). A riboprobe made from the full-length 776-nt sequence bound recombinant vigilin protein (Fig. 1C). We then confirmed vigilin binding to 218-nt c-fms (nt 3415 to 3632) and then demonstrated vigilin's interaction with 69-nt c-fms (nt 3499 to 3568) RNA (Fig. 1C).

These data suggest that the vigilin protein binding site is contained in part within the 69-nt 3′ UTR c-fms sequence. This 69-nt c-fms sequence (3499CUAGUAGAACCUUCUUUCCUAAUCCCCUUAUCUUCAUGGAAAUGGACUGACUUUAUGCCUAUGAAGUCC3567), which we described for HuR binding affinity (46) and which has no homology to other human mRNA stabilizing elements described to date, has five “CUU” motifs (bold underlined). Its predicted secondary structure is complex with two stem-loop formations (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material), suggesting that it could function as an element to which RNA proteins bind. Deletion of this 69-nt sequence would make the RNA in this region significantly less UC rich. In fact, deletion of this 69-nt c-fms sequence (nt 3499 to 3567) (218Δ69nt) containing all five “CUU” motifs abrogated binding to vigilin protein (Fig. 1C).

To confirm that the 69-nt c-fms element contains part of the binding site for vigilin, mutations in the 69-nt c-fms sequence were generated and a vigilin binding assay was performed by UV cross-linking. In the 69-nt c-fms sequence, three regions which collectively encompass all five “CUU” motifs (nt 3509 to 3515, nt 3525 to 3535, and nt 3546 to 3554) were chosen for mutation analysis. Mutations of Us to Gs in all three regions abrogated vigilin binding (Fig. 1C; 69Mut).

Vigilin binding to c-fms 3′ UTR mRNA was also confirmed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), in which vigilin was able to bind to the c-fms 3′ UTR 218-nt and 69-nt segments but not 218Δ69nt or 69Mut (Fig. 1D).

These data demonstrate the specificity of interaction between vigilin protein and the non-AU-rich 69-nt sequence in the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR. These nonconsensus “CUU” motifs found in the 3′ UTR 69-nt sequence appear to be critical for vigilin binding, as it did for HuR binding (46). This binding site is consistent with data from in vitro genetic selection that identified relatively unstructured regions usually containing a G-free region and multiple UC and CU sequences as preferred vigilin binding sites (24).

The 69-nt 3′ UTR c-fms mRNA sequence regulates c-fms expression.

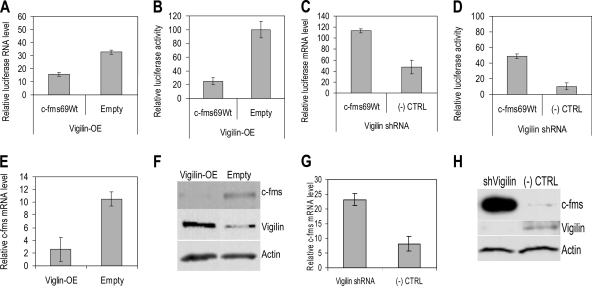

There are numerous reports showing the important role of the 3′ UTR in the regulation of mRNA expression. This regulation primarily involves interaction of cis-acting elements in the 3′ UTR with specific RNA binding proteins. Therefore, we further determined the importance of the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR in this context. In Fig. 1, we showed that vigilin binds specifically to a 69-nt sequence within the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR. We reasoned that this binding is important for vigilin's regulation of c-fms mRNA and protein. We also wanted to understand if such regulation could be seen in the presence of Dex. To confirm that the 69-nt c-fms 3′ UTR sequence regulates posttranscriptional gene expression, this 69-nt sequence was cloned into the 3′ UTR of a luciferase reporter vector (Fig. 2; c-fms69Wt; also see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). After cotransfection of the luciferase-c-fms-3′ UTR 69-nt reporter construct with either vigilin overexpression vector (QC-CMV-FLAG-Vigilin [11) or vigilin shRNA, luciferase RNA levels and activity were measured in Dex-stimulated BT20 cells. Vigilin overexpression decreased luciferase RNA levels by 2.08-fold and luciferase activity by 4.0-fold (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P < 0.001) compared to that in empty vector-transfected cells (Fig. 2A and B). In contrast, suppression of vigilin by shRNA increased luciferase RNA levels by 2.38-fold and luciferase activity by 4.75-fold (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P < 0.001) compared to that in control shRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 2C and D). Vigilin overexpression and suppression affected luciferase activity more than luciferase RNA levels.

FIG. 2.

Vigilin regulates c-fms expression. (A to D) BT20 cells cultured in the presence of Dex were cotransfected with the indicated luciferase-69Wt construct or luciferase vector and vigilin overexpression construct or vigilin shRNA. Relative luciferase activity is the ratio of the activity of firefly luciferase and the renilla luciferase control. With vigilin overexpression, luciferase RNA containing the 69Wt was decreased by 2.08-fold (A) and luciferase activity in the presence of the 69Wt was decreased by 4.0-fold (B) compared to that of cells transfected with empty vector (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P < 0.001). Suppression of vigilin expression increased luciferase RNA containing the 69Wt by 2.38-fold (C) and increased luciferase activity by 4.75-fold (D) over that of control cells (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P < 0.001). (E to H) SKBR3 cells cultured in the presence of Dex were transfected with the vigilin overexpression construct or vigilin shRNA or control empty vectors. c-fms mRNA was decreased by 4.08-fold in SKBR3 cells overexpressing vigilin (E) and c-fms protein levels were decreased by 18.0-fold in SKBR3 cells overexpressing vigilin (F) compared to that in those transfected with empty vector. c-fms mRNA was increased by 2.8-fold in vigilin-suppressed SKBR3 cells (G) and c-fms protein level was increased by 28.8-fold by vigilin suppression (H) compared to that in cells transfected with empty vector.

These data suggest that vigilin specifically interacts with the 69-nt sequence in the 3′ UTR of c-fms mRNA and that this interaction is sufficient to posttranscriptionally downregulate gene expression.

Vigilin controls c-fms expression.

In order to determine the relative influence of vigilin on the expression of c-fms, vigilin was overexpressed or suppressed in breast cancer cells. The duration of transfections in Dex-stimulated SKBR3 cells was 4 days, because vigilin overexpression or silencing is readily apparent at 4 days. We determined the effects of altering the level of vigilin on the level of c-fms mRNA and protein (Fig. 2E to H). Overexpression of vigilin decreases the level of c-fms mRNA by 4.08-fold. At the same time, the c-fms protein levels decreased by 18.0-fold compared to that in empty vector-transfected SKBR3 cells (Empty) cultured in the presence of Dex (Fig. 2E and F). We confirmed increased vigilin mRNA and protein levels by vigilin overexpression (see Fig. S7A in the supplemental material).

We also downregulated vigilin expression in Dex-stimulated-SKBR3 cells (Fig. 2G and H). Suppression of vigilin increases the c-fms mRNA level by 2.8-fold compared to that in control shRNA-transfected SKBR3 cells [(−) CTRL]. By immunoblot, we showed that suppression of vigilin increased the level of c-fms protein by 28.8-fold compared to that in control SKBR3 cells [(−) CTRL] cultured in the presence of Dex. As expected, we confirmed that vigilin mRNA and protein levels were decreased in response to vigilin silencing (Fig. 2H; also see Fig. S7B in the supplemental material). Knockdown of vigilin resulted in a larger increase in the level of c-fms protein than in the level of c-fms mRNA. These data suggest that vigilin may regulate c-fms at both the mRNA and protein levels.

Vigilin downregulates the half-life of c-fms mRNA.

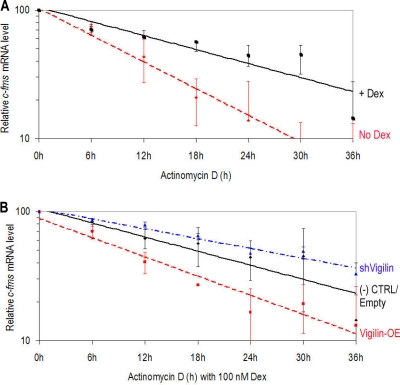

We first studied whether vigilin may destabilize c-fms mRNA. Compared to levels in cells transfected with empty vector, SKBR3 cells overexpressing vigilin showed a decrease in c-fms mRNA levels and cells in which vigilin levels were reduced with shRNA showed an increase in c-fms mRNA levels. Previous studies have shown that the expression of c-fms mRNA and protein is stimulated by Dex in vitro and in vivo (7, 44). We also recently showed that posttranscriptional stimulation of c-fms mRNA and protein by Dex is dependent on HuR. To first determine if there are changes in c-fms mRNA stability in the presence or absence of Dex, we used actinomycin D (Act D) to block de novo mRNA transcription. Resting BT20 cells in the absence of Dex were collected at several time points after Act D treatment, and c-fms mRNA expression levels were determined by qRT-PCR. tRNAGlu was used as an internal loading control, since tRNA is stable and has a long half-life (>5 days) due to its secondary structure (20). Housekeeping genes such as GAPDH mRNA have a similar half-life (∼17 h) to that of c-fms mRNA in breast cancer cells (not shown), and therefore GAPDH mRNA was not used for an internal loading control. In resting BT20 cells in the absence of Dex, the c-fms mRNA half-life was 9.6 h (Fig. 3A). In comparison, the c-fms mRNA half-life in Dex-stimulated BT20 cells was determined to be 18.9 h (Fig. 3A). This more than 2-fold increase in c-fms mRNA half-life (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P < 0.001) by Dex indicates a significant effect on enhancement of c-fms mRNA stability.

FIG. 3.

The effects of vigilin overexpression or suppression on the stability of c-fms mRNA. At 4 days after transfection, BT20 cells were treated with Act D and the half-life of c-fms mRNA was calculated. (A) In resting BT20 cells in the absence of Dex, the half-life of c-fms mRNA was 9.6 h. In the presence of Dex, half-life for the c-fms mRNA was 18.9 h. (B) In BT20 cells cultured in the presence of Dex, altering vigilin level altered c-fms mRNA half-life. In BT20 cells overexpressing vigilin (Vigilin-OE), the half-life of c-fms mRNA was reduced to 10.1 h. In vigilin-suppressed BT20 cells (shVigilin), the c-fms mRNA half-life was increased to 25.8 h. The mRNA half-life represents mean ± SEM of results of three independent experiments.

Since vigilin binds the 69-nt sequence in c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR, we studied the effects of altering vigilin levels on c-fms mRNA half-life in Dex-stimulated cells. The vigilin protein level was not influenced by Dex (not shown). As shown in Fig. 3B, at least part of the 4.08-fold decrease in the steady-state level of c-fms mRNA in BT20 cells seen on overexpression of vigilin (Fig. 2E) is due to a reduction in the stability of c-fms mRNA. When the empty vector treatment groups in BT20 cells were compared with vigilin-overexpressed groups (Vigilin-OE), the c-fms mRNA half-life declined from 18.9 h to 10.1 h (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P < 0.001). These results underscore the destabilizing influence of vigilin on c-fms mRNA.

To study the effect of vigilin downregulation on the expression of c-fms mRNA, we used a plasmid-expressing shRNA that targeted vigilin. At 4 days after transfection, vigilin expression was reduced below 50% of the levels seen in control cells. Reducing the level of vigilin with shRNA increased c-fms mRNA levels seen in Dex-stimulated cells. Here we find that the stability of the c-fms transcript was also influenced by vigilin abundance: partial silencing of vigilin increased c-fms mRNA half-life from 18.9 h to 25.8 h (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P = 0.001) (Fig. 3B; shVigilin). This finding of change of c-fms mRNA stability by vigilin contributes but does not entirely explain the magnitude of vigilin's posttranscriptional regulation of c-fms in Dex-stimulated breast cancer cells. Taken together our data indicate that vigilin destabilizes c-fms mRNA.

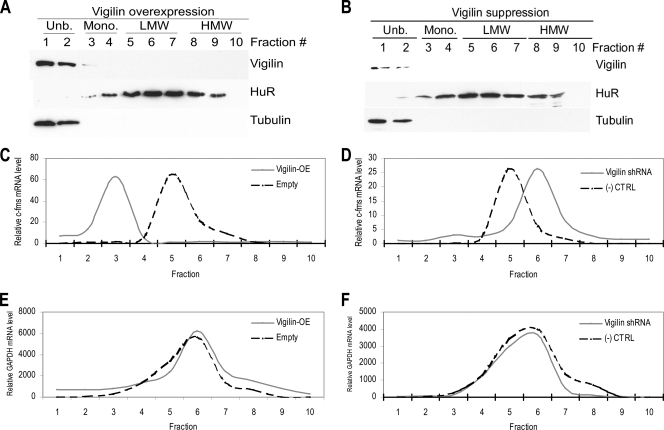

Vigilin inhibits translation of c-fms or reporter RNA.

Since alteration of vigilin expression has more prominent effects on the c-fms protein level than on the mRNA level, we tested whether vigilin affects translation of c-fms mRNA. Polysome profiles of cytoplasmic lysates from BT20 cells cultured in the presence of Dex were generated by sucrose gradient centrifugation (Fig. 4). Overexpression or suppression of vigilin did not affect the distribution of vigilin and HuR proteins in polysome profiles (Fig. 4A and B). Most of the vigilin cosedimented with free RNP (Fig. 4A and B; Unb., fractions 1 to 2), where cytosolic β-tubulin was also detected. However, a small portion of vigilin cosedimented also with the low-molecular-weight (low-MW) monosomes (Fig. 4A and B; Mono., fractions 3 to 4). In contrast and in keeping with earlier reports (28), HuR was found to colocalize primarily with low- and high-MW polysome fractions (Fig. 4A and B; LMW, fractions 5 to 7; HMW, fractions 8 to 10). We used polysome profiling to test whether vigilin affects translation of c-fms mRNA. In BT20 cells cultured in the presence of Dex and transfected with the control empty vector, 88.9% of c-fms mRNA cosedimented with polysomes (Fig. 4C, fractions 4 to 10). Upon overexpression of vigilin, 72.1% of c-fms mRNA cosedimented with free ribosomes instead (Fig. 4C, fractions 1 to 3). In contrast, knockdown of vigilin increased the proportion of c-fms mRNA in polysomes to nearly 100% (Fig. 4D, fractions 4 to 10). Vigilin overexpression or knockdown had little effect upon the distribution of GAPDH mRNA which served as controls (Fig. 4E and F). Similar effects were also observed in SKBR3 cells (not shown).

FIG. 4.

Vigilin abundance affects the distribution of c-fms mRNA on polysomes. Dex-treated BT20 cells were transfected with either control or vigilin shRNA or QC-CMV-FLAG-Vigilin or pCMV-FLAG. Polysome profiles were prepared by sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation. (A and B) Relative distributions of vigilin, HuR, and β-tubulin were obtained by IB analyses of the polysome gradient. Fractions: 1 and 2, unbound RNPs (Unb.); 3 and 4, monosomes (Mono.); 5 to 10, low- and high-MW polysomes (LMW and HMW). (A) Vigilin, HuR, and β-tubulin distribution in vigilin-overexpressed BT20 cells. (B) Vigilin, HuR, and β-tubulin distribution in vigilin-suppressed BT20 cells. (C and E) Relative distributions of c-fms mRNA (C) and GAPDH mRNA (E) in polysome gradients after vigilin overexpression. Empty, empty vector-transfected cells. (D and F) Relative distributions of c-fms mRNA (D) and GAPDH mRNA (F) in polysome gradients after vigilin supression by shRNA. (−) CTRL, control shRNA-transfected cells. Data shown are mean results from three independent experiments.

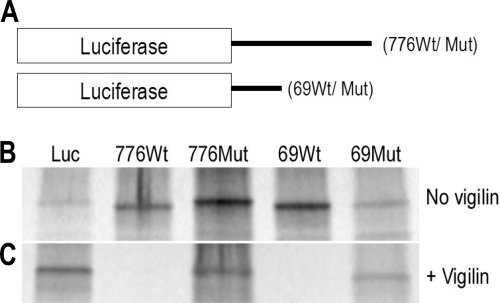

To confirm vigilin's inhibitory effect on translation as well as to investigate the inhibitory role of vigilin's interaction with the c-fms 3′ UTR on translation, luciferase mRNAs ligated with either the c-fms 3′ UTR 776-nt or 69-nt sequence were translated with rabbit reticulocyte lysates (Fig. 5A). In the absence of vigilin, the [35S]methionine-labeled luciferase protein was produced in the presence of both wild-type and mutant c-fms 3′ UTR 776-nt or 69-nt sequences (Fig. 5B). However, in the presence of vigilin, translation of [35S]methionine-labeled luciferase protein was inhibited in the context of wild-type c-fms 3′ UTR 776-nt and 69-nt sequences (Fig. 5C), with no impairment of translation in the context of the mutant 3′ UTR sequences. These results indicate that vigilin interacts with c-fms 3′ UTR wild-type sequence to inhibit translation of luciferase mRNA.

FIG. 5.

Translation of luciferase message using rabbit reticulocyte lysates. (A) Luciferase messages ligated with either wild-type or mutant c-fms 3′ UTR 776-nt or 69-nt sequence were generated for in vitro translation. (B and C) SDS-PAGE of 35S-labeled luciferase protein. Luciferase message was translated using [35S]methionine in the absence or presence of vigilin. (B) In the absence of vigilin, all luciferase RNAs were able to be translated into luciferase protein. (C) In the presence of vigilin, however, luciferase protein was not able to be translated from luciferase RNAs containing wild-type c-fms 3′ UTR 776-nt or 69-nt sequences (776Wt and 69Wt). In contrast, translation of luciferase protein was able to proceed from luciferase RNAs with mutant c-fms 3′ UTR 776-nt or 69-nt sequences (776Mut and 69Mut).

Taken together, these results indicate that vigilin regulates c-fms levels both by regulating the efficiency of translation and by controlling c-fms mRNA decay.

Vigilin and HuR compete for binding to the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR.

Since both vigilin and HuR bind to the 69-nt sequence at the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR in vitro and in vivo, we tested whether the two proteins compete for the binding to the 69-nt sequence. By UV cross-linking assays, we show that vigilin competes with HuR for binding to the 69-nt sequence at the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material). Increasing the amount of vigilin reduces binding of HuR to the 69-nt sequence, resulting in the appearance of the vigilin/c-fms RNA binding complex. At a 1:1 molar ratio of vigilin and HuR, vigilin bound to the 69-nt sequence with a higher affinity. The higher affinity of vigilin may be explained by the 15 KH domains in vigilin compared to the three RNA recognition motifs in HuR. While factors, including the relative affinities of the proteins for c-fms mRNA binding in vitro can affect the results of this experiment, these data suggest that HuR and vigilin compete for binding to the 69-nt sequence in the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR.

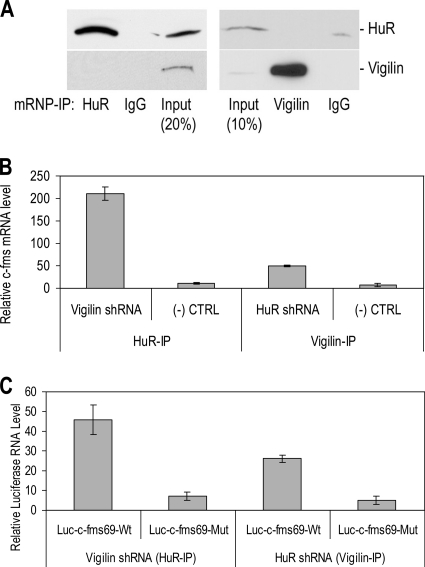

To further investigate whether vigilin and HuR can bind to shared target mRNAs in vivo at the same time, cytoplasmic lysates from SKBR3 cells were immunoprecipitated by vigilin antibody and immunoblotted by HuR antibody or vice versa. In neither case did we see IP-mRNP complexes which contained both vigilin and HuR (Fig. 6A). These data suggest that vigilin may not associate directly with HuR. Also these data suggest that vigilin and HuR, in binding the same 69-nt sequence in the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR, may compete for binding such that they cannot bind to the same mRNA simultaneously.

FIG. 6.

Vigilin and HuR compete for binding to the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR. (A) Vigilin and HuR are not present in the same mRNP complexes. IP assays were carried out using cellular lysates from SKBR3 cells in RNase-free (RNase-free) conditions using mouse anti-human HuR MAb, mouse anti-human vigilin MAb, or IgG. The presence of HuR (top) and vigilin (bottom) in the IP materials was monitored by IB. (B and C) Effects of vigilin and HuR levels on their association with endogenous c-fms and reporter mRNA. (B) SKBR3 cells cultured in the presence of Dex were transfected with vigilin shRNA, HuR shRNA, or control shRNA. HuR pulldown was performed in cells treated with vigilin shRNA and vigilin pulldown in the cells treated with HuR shRNA. qRT-PCR of c-fms mRNA abundance was measured in cytoplasmic lysates after IP of mRNP complexes. (Two-tailed t test compared to controls: P < 0.001, n = 3.) (C) Dex-treated SKBR3 cells were transfected with vigilin or HuR shRNA together with either pcDNA3.1-Luc-c-fms 69Wt or pcDNA3.1-Luc-c-fms 69Mut (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Luciferase RNA abundance was examined by qRT-PCR in cytoplasmic lysates after IP of mRNP complexes. (Two-tailed t test compared to controls: P < 0.001, n = 3.)

As both vigilin and HuR bind the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR 69-nt sequence with opposing effects on mRNA stability, we investigated the interplay between vigilin and HuR levels on c-fms expression. HuR abundance was unaffected by vigilin knockdown and vice versa (not shown). Accordingly, we examined their competitive binding to c-fms mRNA in vivo. We knocked down vigilin or HuR and used immunoprecipitation followed by qRT-PCR to determine the level of endogenous c-fms or luciferase mRNA (in separate experiments with cells transfected with luciferase-69-nt wild-type or mutant constructs) associated with HuR or vigilin. After shRNA-mediated knockdown of vigilin, c-fms mRNA abundance measured in HuR antibody immunoprecipitates increased 17.9-fold (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P < 0.001) (Fig. 6B). Likewise, HuR knockdown and IP with vigilin antibody increased vigilin association with c-fms mRNA 6.9-fold (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P < 0.001). We showed that vigilin's silencing did not affect the abundance of immunoprecipitated HuR protein and vice versa (not shown).

Similarly, in experiments using the luciferase-c-fms 3′ UTR 69-nt reporter constructs, we observed luciferase mRNA levels increase under the same conditions, but only in the presence of the wild-type, but not the c-fms 3′ UTR mutant 69-nt sequence (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that suppression of vigilin results in increased association of HuR with c-fms mRNA. Consistent with this interpretation, suppression of HuR increased the amount of c-fms mRNA associated with vigilin. Similar results were obtained with luciferase reporter RNA, but only in the presence of the wild-type 69-nt sequence. This suggests that vigilin and HuR exhibit sequence specificity in binding to the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR 69-nt sequence. Furthermore, suppression of one protein favors association of the other protein with either endogenous c-fms mRNA or the luciferase-c-fms 3′ UTR 69Wt reporter RNA.

In sum, these data indicate that vigilin and HuR competitively bind to the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR 69-nt sequence in vivo and suggest a dynamic process in which intracellular levels of vigilin and HuR control the extent to which each protein is bound to the c-fms 3′ UTR and control the decay and translation of c-fms mRNA.

Both vigilin and HuR regulate cell invasion and motility of human breast cancer cells in vitro.

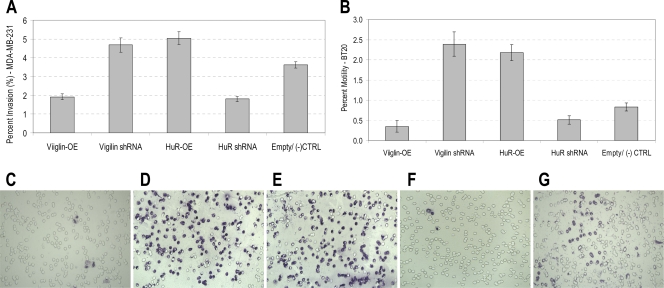

Using MDA-MB-231 and BT20 breast cancer cells cultured in the presence of Dex, we performed in vitro loss-of-function analyses by silencing vigilin or HuR (shRNA) and gain-of-function analyses by overexpressing (OE) vigilin or HuR. Alteration of vigilin or HuR expression had no significant effect on cell proliferation in vitro (not shown). In vitro invasion of these cells through a human extracellular matrix was studied using a transwell assay. Either silencing of vigilin or overexpression of HuR increased the degree of invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells by 1.4-fold compared to that of control empty vector-containing cells (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P = 0.009) (Fig. 7A). In contrast, overexpression of vigilin decreased the degree of invasion by 1.9-fold (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P = 0.001) compared to that of the control [(−) CTRL]. Silencing of HuR also decreased the degree of invasion by 2.0-fold (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P = 0.001), compared to those of their respective controls [(−) CTRL]. Similar effects on invasiveness were also observed in BT20 cells (Fig. 7C to G).

FIG. 7.

Vigilin and HuR regulate in vitro invasiveness and motility of breast cancer cells. In vitro invasion through a human extracellular matrix (A) and fibronectin-directed motility of cells (B) were studied. (A) Invasiveness of MDA-MB-231 cells. (B) Motility of BT20 cells. (C to G) Photographs of representative fields (×10 magnification) depicting invasiveness of BT20 cells overexpressing vigilin (C), with vigilin suppression (D), overexpressing HuR (E), with HuR suppression (F), and transfected with empty vector control (G).

Effects of alteration of vigilin or HuR expression on directed motility of BT20 cells were also studied (Fig. 7B) using fibronectin as a chemoattractant. Either silencing of vigilin or overexpression of HuR increased the degree of motility by 2.9-fold compared to that of control cells (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P = 0.001). In contrast, overexpression of vigilin decreased the degree of motility by 2.4-fold (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P = 0.004), compared to that of control cells containing empty vector [(−) CTRL]. Silencing of HuR also decreased the degree of motility by 1.6-fold (two-tailed t test, n = 3, P = 0.017) compared to those of their respective controls [(−) CTRL]. Taken together, these observations show that both vigilin and HuR regulate in vitro invasiveness and motility of breast cancer cells and may have opposing functional roles in regulating behavior of breast cancer cells, as they do on competitive regulation of c-fms expression in breast cancer cells.

DISCUSSION

Both transcriptional and posttranscriptional control of c-fms by GCs have been reported (6, 7, 38). Chambers et al. originally proposed the involvement of a c-fms mRNA stabilizing protein in the posttranscriptional regulation of c-fms mRNA by GCs in breast carcinoma cell lines (7). Recent work from our laboratory has shown that HuR increases levels of c-fms mRNA and protein in breast cancer cells by binding to a 69-nt sequence in the c-fms mRNA and that GC stimulation of c-fms was dependent on HuR's presence (46). In our subsequent search for c-fms mRNA binding proteins which downregulate c-fms mRNA, we identified vigilin, which we now show decreases c-fms mRNA half-life (Fig. 3) and also significantly suppresses c-fms or reporter translation (Fig. 4 and 5). To our knowledge, the work presented here is the first to directly demonstrate vigilin's ability to regulate translation and enhance mRNA decay. In particular, our results uncover a novel mode of c-fms posttranscriptional regulation in which the relationship between vigilin and HuR levels in cells dictates the extent to which each protein occupies the 69-nt binding site in the 3′ UTR of c-fms mRNA and influences the stability and translation of c-fms mRNA. Thus, vigilin may be essential to maintain c-fms expression at normal physiological levels.

c-fms encodes a receptor tyrosine kinase and relays cytokine CSF-1 signals. Our study indicates that in resting conditions in the absence of GC, the half-life of c-fms mRNA is 9.6 h. While this relatively long half-life is atypical for an mRNA important in signal transduction (40), some mRNAs, such as estrogen-stabilized Xenopus vitellogenin mRNA, have half-lives of many days (4). The half-life of c-fms mRNA more than doubles to 18.9 h in BT20 cells in the presence of Dex. This more than 2-fold increase in the already long half-life of c-fms mRNA by Dex can account for the dramatic increase in steady-state c-fms mRNA and protein levels by GCs at 72 to 96 h.

Vigilin competes with and limits binding of HuR, a c-fms mRNA stabilizer, to the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR 69-nt sequence, thereby promoting c-fms mRNA degradation. Overexpression of vigilin decreases c-fms mRNA half-life and also significantly suppresses c-fms translation in a process that requires the 69-nt sequence. In contrast, suppression of HuR increases the association of vigilin with the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR 69-nt sequence, decreasing the half-life and subsequently the translation of c-fms mRNA. Because the effect of vigilin on translation is more dominant than its impact on mRNA decay, and in light of the already long mRNA half-life of the endogenous c-fms message, an alternative interpretation of our data is that the effect of vigilin on mRNA decay is secondary to its impact on translation initiation. Our data also does not rule out the likely possibility that both vigilin and HuR might affect the association of other c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR-binding proteins that play a role in c-fms mRNA stability and translation.

Our recent work showed that alteration of HuR expression has, as its primary effect, an alteration of the level of c-fms mRNA rather than of c-fms protein (46). In GC-stimulated breast cancer cells, knockdown or overexpression of HuR downregulates the level of c-fms mRNA by 233-fold or upregulates it by 47-fold, respectively. In contrast, vigilin overexpression appears to, in addition, directly suppress translation. Either knockdown or overexpression of vigilin has a 5- to 10-fold greater effect on the level of c-fms protein than on the level of c-fms mRNA (Fig. 2). This suggests different modes of regulation of c-fms expression by HuR and vigilin. We interpret this result to mean that vigilin does not simply block binding of the HuR protein to c-fms mRNA to suppress its translation.

Our data raise several questions. How does vigilin destabilize c-fms mRNA via the c-fms 69-nt binding site? How does vigilin suppress c-fms translation? Are the two processes interrelated? Does the c-fms 69-nt sequence contain embedded regulatory codes dictating c-fms mRNA stabilization and translation? One possible mechanism is that vigilin's effect may involve regulation of the closed loop in an mRNP model proposed by others (1). RNA binding proteins that are known translational repressors, such as fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) (15), TIAR (31), and TIA-1 (25), may inhibit closed-loop formation. Existence of this model in mammalian systems, however, has yet to be confirmed.

The physiological role of vigilin is not known. In our study using human breast cancer cells, alteration of vigilin expression modulated c-fms expression and also the degree of motility and invasion without affecting cell proliferation. The effect of vigilin on c-fms expression is opposite to the effect of HuR. Vigilin suppresses and HuR promotes c-fms expression competitively in breast cancer cells. Using a large-cohort breast cancer tissue array (46), we showed nuclear HuR expression is associated with nodal metastasis and poor survival, as well as coexpression with c-fms in the breast tumors (P = 0.0007). Opposing effects of vigilin and HuR on c-fms expression and on motility and invasion in breast cancer cells lead us to propose vigilin as a potential repressor of invasion and metastasis. Vigilin and HuR regulate c-fms levels, with important biological consequences. Deregulation of this balance may be an important contributor to breast cancer progression.

In conclusion, we identified vigilin as a previously uncharacterized posttranscriptional regulator that controls c-fms levels by regulating both c-fms mRNA decay and translation. Our study indicates that vigilin and HuR compete for the same 69-nt sequence in the c-fms mRNA 3′ UTR and that dynamic changes in the ratio of vigilin to HuR can influence their ability to associate with the c-fms mRNA and posttranscriptionally regulate cellular c-fms levels. Vigilin may function as a tumor repressor, inhibiting breast cancer invasion and metastasis through vigilin's ability to compete for HuR's function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Department of Defense grant DAMD 17-02-1-0633 (to S.K.C.), by Arizona Biomedical Research Commission grant 07-061 (to S.K.C.), by the Rodel Foundation (to S.K.C.), and by NIH grant DK 071909 (to D.J.S.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 October 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amrani, N., S. Ghosh, D. A. Mangus, and A. Jacobson. 2008. Translation factors promote the formation of two states of the closed-loop mRNP. Nature 453:1276-1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balagopal, V., and R. Parker. 2009. Polysomes, P bodies and stress granules: states and fates of eukaryotic mRNAs. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21:403-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bor, Y. C., J. Swartz, Y. Li, J. Coyle, D. Rekosh, and M. L. Hammarskjold. 2006. Northern blot analysis of mRNA from mammalian polyribosomes. Nat. Protoc. doi: 10.1038/nprot.216. [DOI]

- 4.Brock, M. L., and D. J. Shapiro. 1983. Estrogen stabilizes vitellogenin mRNA against cytoplasmic degradation. Cell 34:207-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers, S. K. 2009. Role of CSF-1 in progression of epithelial ovarian cancer. Future Oncol. 5:1429-1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambers, S. K., C. M. Ivins, B. M. Kacinski, and R. B. Hochberg. 2004. An unexpected effect of glucocorticoids on stimulation of c-fms proto-oncogene expression in choriocarcinoma cells that express little glucocorticoid receptor. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 190:974-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers, S. K., Y. Wang, M. Gilmore-Hebert, and B. M. Kacinski. 1994. Post-transcriptional regulation of c-fms proto-oncogene expression by dexamethasone and of CSF-1 in human breast carcinomas in vitro. Steroids 59:514-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chambers, S. K., B. M. Kacinski, C. M. Ivins, and M. L. Carcangiu. 1997. Overexpression of epithelial macrophage colony-stimulating factor (CSF-1) and CSF-1 receptor: a poor prognostic factor in epithelial ovarian cancer, contrasted with a protective effect of stromal CSF-1. Clin. Cancer Res. 3:999-1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, C. Y., R. Gherzi, S.-E. Ong, E. L. Chan, R. Raijmakers, G. J. M. Pruijn, G. Stoecklin, C. Moroni, M. Mann, and M. Karin. 2001. AU binding proteins recruit the exosome to degrade ARE-containing mRNAs. Cell 107:451-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colegrove-Otero, L. J., N. Minshall, and N. Standart. 2005. RNA-binding proteins in early development. Cri. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40:21-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham, K. S., R. E. Dodson, M. A. Nagel, D. J. Shapiro, and D. R. Schoenberg. 2000. Vigilin binding selectively inhibits cleavage of the vitellogenin mRNA 3′-untranslated region by the mRNA endonucleases polysomal ribonuclease 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:12498-12502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai, X.-M., G. R. Ryan, A. J. Hapel, M. G. Dominguez, R. G. Russell, S. Kapp, V. Sylvestre, and E. R. Stanley. 2009. Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood 99:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dodson, R. E., and D. J. Shapiro. 1997. Vigilin, a ubiquitous protein with 14 K homology domains, is the estrogen-inducible vitellogenin mRNA 3′-untranslated region-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 272:12249-12252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan, X. C., and J. Steitz. 1998. Overexpression of HuR, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling protein, increases the in vivo stability of ARE-containing mRNAs. EMBO J. 17:3448-3460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng, Y., D. Absher, D. E. Eberhart, V. Brown, H. E. Malter, and S. T. Warren. 1997. FMRP associates with polyribosomes as an mRNA, and the 1304N mutation of severe fragile abolishes this association. Mol. Cell 1:109-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fidge, N. H. 1999. High density lipoprotein receptors, binding proteins, and ligands. J. Lipid Res. 40:187-201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garneau, N. L., J. Wilusz, and C. J. Wilusz. 2007. The highways and byways of mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:113-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gherzi, R., K. Y. Lee, P. Briata, D. Wegmüller, C. Moroni, M. Karin, and C. Y. Chen. 2004. A KH domain RNA binding protein, KSRP, promotes ARE-directed mRNA turnover by recruiting the degradation machinery. Mol. Cell 14:571-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grosset, C., C. Y. Chen, N. Xu, N. Sonenberg, H. Jacquemin-Sablon, and A. B. Shyu. 2000. A mechanism for translationally coupled mRNA turnover: interaction between the poly(A) tail and a c-fos RNA coding determinant via a protein complex. Cell 103:29-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanoune, J., and M. K. Agarwal. 1970. Studies on the half life time of rat transfer RNA species. FEBS Lett. 11:78-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hau, H. H., R. J. Walsh, R. L. Ogilvie, D. A. Williams, C. S. Reilly, and P. R. Bohjanen. 2007. Tristetraproline recuits functional mRNA decay complexes to ARE sequences. J. Cell. Biochem. 100:1477-1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kacinski, B. M., K. A. Scata, D. Carter, L. D. Yee, E. Sapi, B. L. King, S. K. Chambers, M. A. Jones, M. H. Pirro, and E. R. Stanley. 1991. FMS (CSF-1 receptor) and CSF-1 transcripts and protein are expressed by human breast carcinomas in vivo and in vitro. Oncogene 6:941-952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaminski, A., D. H. Ostareck, N. M. Standart, and R. J. Jackson. 1998. Affinity methods for isolating RNA binding proteins, p. 137-160. In C. W. J. Smith (ed.), RNA:protein interactions: a practical approach. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 24.Kanamori, H., R. E. Dodson, and D. J. Shapiro. 1998. In vitro genetic analysis of the RNA binding site of vigilin, a multi-KH-domain protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:3991-4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawai, T., A. Lal, X. Yang, S. Galban, K. Mazan-Mamczarz, and M. Gorospe. 2006. Translational control of cytochrome c by RNA binding proteins TIA-1 and HuR. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:3295-3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kluger, H. M., M. D. Dolled-Filhart, S. Rodov, B. M. Kacinski, R. L. Camp, and D. L. Rimm. 2004. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor expression is associated with poor outcome in breast cancer by large cohort tissue microarray analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 10:173-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruse, C., D. Willkomm, J. Gebken, A. Schuh, H. Stossberg, T. Vollbrandt, and P. K. Müller. 2003. The multi-KH protein vigilin associates with free and membrane-bound ribosomes. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 60:2219-2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lal, A., K. Mazan-Mamczarz, T. Kawai, X. Yang, J. L. Martindale, and M. Gorospe. 2004. Concurrent versus individual binding of HuR and AUF1 to common labile target mRNAs. EMBO J. 23:3092-3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lang, B. D., and J. L. Fridovich-Keil. 2000. Scp160p, a multiple KH-domain protein, is a component of mRNP complexes in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:1576-1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, W., N. Thakor, E. Y. Xu, Y. Huang, C. Chen, R. Yu, M. Holcik, and A. N. Kong. 2010. An internal ribosomal entry site mediates redox-sensitive translation of Nrf2. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:778-788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao, B., Y. Hu, and G. Brewer. 2007. Competitive binding of AUF1 and TIAR to MYC mRNA controls its translation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14:511-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin, E. Y., A. V. Nguyen, R. G. Russell, and J. W. Pollard. 2001. Colony-stimulating factor 1 promotes progression of mammary tumors to malignancy. J. Exp. Med. 193:727-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez de Silanes, I., M. Zhan, A. Lal, X. Yang, and M. Gorospe. 2004. Identification of a target RNA motif for RNA-binding protein HuR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:2987-2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazumder, B., V. Seshardri, and P. L. Fox. 2003. Translational control by the 3′-UTR: the ends specify the means. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28:91-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKnight, G. L., J. Redasoner, K. O. Sundquist, B. Hokland, P. A. McKernan, J. Champagne, C. J. Johnson, M. C. Bailey, R. Holly, P. J. O'Hara, and J. F. Oram. 1992. Cloning and expression of a cellular high density lipoprotein-binding protein that is up-regulated by cholesterol loading of cells. J. Biol. Chem. 267:12131-12141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris, A. K., N. Mukherjee, and J. D. Keene. 2010. Systematic analysis of posttranscriptional gene expression. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2:162-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pullman, H. H. Kim, K. Abdelmohsen, A. Lai, J. L. Martindale, X. Yang, and M. Gorospe. 2007. Analysis of turnover and translation regulatory RNA-binding protein expression through binding to cognate mRNAs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:6265-6278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sapi, E., M. B. Flick, M. Gilmore-Hebert, S. Rodov, and B. M. Kacinski. 1995. Transcriptional regulation of the c-fms (CSF-1R) proto-oncogene in human breast carcinoma cells by glucocorticoids. Oncogene 10:529-542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarkar, B., Q. Xi, C. He, and R. J. Schneider. 2003. Selective degradation of AU-rich mRNAs promoted by the p37 AUF1 protein isoform. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:6685-6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharova, L. V., A. A. Sharov, T. Nedorezov, Y. Piao, N. Shaik, and M. S. Ko. 2009. Database for mRNA half-life of 19,977 genes obtained by DNA microarray analysis of pluripotent and differentiating mouse embryonic stem cells. DNA Res. 16:45-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherr, J. S., C. W. Rettenmier, R. Sacca, M. F. Roussel, A. T. Look, and E. R. Stanley. 1985. The c-fms proto-oncogene product is related to the receptor for the mononuclear phagocyte growth factor, CSF-1. Cell 41:665-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shyu, A.-B., M. F. Wilkinson, and A. van Hoof. 2008. Messenger RNA regulation: to translation or to degrade. EMBO J. 27:471-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toy, E. P., M. Azodi, N. L. Folk, C. M. Zito, C. J. Zeiss, and S. K. Chambers. 2009. Enhanced ovarian cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis by the macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Neoplasia 11:136.-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toy, E. P., N. Bonafé, A. Savlu, C. Zeiss, W. Zheng, M. Flick, and S. K. Chambers. 2005. Correlation of tumor phenotype with c-fms proto-oncogene expression in an in vivo intraperitoneal model for experimental human breast cancer metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 22:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reference deleted.

- 46.Woo, H. H., Y. Zhou, X. Yi, C. L. David, W. Zheng, M. Gilmore-Hebert, H. M. Kluger, E. C. Ulukus, T. Baker, J. B. Stoffer, and S. K. Chambers. 2009. Regulation of non-AU-rich element containing c-fms proto-oncogene expression by HuR in breast cancer. Oncogene 28:1176-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.