Abstract

In the enteric pathogen Vibrio cholerae, expression of the major virulence factors is controlled by the hierarchical expression of several regulatory proteins comprising the ToxR regulon. In this study, we demonstrate that disruption of the fadD gene encoding a long-chain fatty acyl coenzyme A ligase has marked effects on expression of the ToxR virulence regulon, motility, and in vivo lethality of V. cholerae. In the V. cholerae fadD mutant, expression of the major virulence genes ctxAB and tcpA, encoding cholera toxin (CT), and the major subunit of the toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP) was drastically repressed and a growth-phase-dependent reduction in the expression of toxT, encoding the transcriptional activator of ctxAB and tcpA, was observed. Expression of toxT from an inducible promoter completely restored CT to wild-type levels in the V. cholerae fadD mutant, suggesting that FadD probably acts upstream of toxT expression. Expression of toxT is activated by the synergistic effect of two transcriptional regulators, TcpP and ToxR. Reverse transcription-PCR and Western blot analysis indicated that although gene expression and production of both TcpP and ToxR are unaffected in the fadD mutant strain, membrane localization of TcpP, but not ToxR, is severely impaired in the fadD mutant strain from the mid-logarithmic phase of growth. Since the decrease in toxT expression occurred concomitantly with the reduction in membrane localization of TcpP, a direct correlation between the defect in membrane localization of TcpP and reduced toxT expression in the fadD mutant strain is suggested.

The Gram-negative, noninvasive enteric bacterium Vibrio cholerae has caused devastating outbreaks of the acute diarrheal disease cholera all over the world since ancient times (32). The Indian subcontinent, particularly the Bengal Gangetic Delta, thought to be the original reservoir of V. cholerae, is still ravaged by epidemics of cholera. Indeed, even today outbreaks of cholera triggered by natural as well as human-made disasters like floods and droughts, poverty, and wars continue to occur in developing countries. The frequency and intensity of cholera epidemics may be considered key indicators of social development.

The pathogenicity of V. cholerae is largely due to the production of cholera toxin (CT) and a toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP) thought to be essential for colonization of the intestinal epithelium by the bacteria (17, 38). The expression of the ctxAB and tcpA genes, encoding CT and the major subunit of TCP, respectively, is activated by ToxT, a member of the AraC family of transcriptional regulators (9). Expression of toxT in turn is activated by the synergistic activity of ToxR and TcpP, inner membrane proteins with cytoplasmic DNA binding domains belonging to the OmpR family (16, 29). Expression of tcpP is controlled by the membrane-located AphA/AphB proteins (19, 36). This cascade of transcription regulators that control the virulence of V. cholerae is known for historical reasons to be the ToxR regulon (7, 27). The ToxR regulon is modulated by other global regulators, like the anaerobiosis response regulator ArcA/ArcB (34), the cyclic di-GMP phosphodiesterase VieA (39, 40), cyclic AMP (cAMP)/cAMP receptor protein (CRP) (20), etc., which exert their effects at different levels of the cascade. However, the exact mechanism by which these factors modulate the ToxR regulon is known only for cAMP/CRP. The cAMP/CRP complex can bind to the tcpP promoter at a site within the binding sites of AphA and AphB, thus preventing the activation of tcpP expression by AphA and AphB (20). Although decreased toxT transcript levels have been observed in both ΔvieSAB and arcA mutants, the molecular mechanism of action of these regulators is not clear (34, 39).

The ToxR regulon is also strongly influenced by physicochemical parameters (22), such as temperature (4, 30); osmolarity, pH, and amino acids (28); aeration (21); and bile (13, 15, 33). We have reported earlier that the unsaturated fatty acids present in bile, arachidonic, linoleic, and oleic acids, drastically repressed expression of the ctxAB and tcpA genes even in the presence of the transcriptional activator ToxT (6). More recently, the crystal structure of ToxT has been solved and shows that ToxT contains an almost buried, solvent-inaccessible singly unsaturated cis-palmitoleate, and in vitro experiments have demonstrated that unsaturated fatty acids inhibited the binding of ToxT to the tcpA promoter (24). Unsaturated fatty acids have also been shown to bind to CT and prevent the binding of CT to the GM1 receptor (5).

In bacteria, the product of the fadD gene is a long-chain fatty acyl coenzyme A (acyl-CoA) ligase that is postulated to activate exogenous long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) by acyl-CoA ligation concomitant with transport across the cytoplasmic membrane (3, 11, 44). Here we report that a V. cholerae fadD mutant exhibits a hypovirulent phenotype. Expression of the major virulence genes of the ToxR regulon is repressed and membrane localization of the master regulator TcpP is impaired in the fadD mutant strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. For optimum expression of virulence factors, V. cholerae was grown in LB medium (pH 6.6) at 30°C, referred to as permissive conditions (28). The suicide vectors pGP704 and pCVD442 (10, 28) were used for construction of insertion and deletion mutants and were maintained in Escherichia coli strain SM10λpir or DH5αλpir. Plasmids were introduced into V. cholerae strains by triparental mating using E. coli MM294(pRK2013) as a donor of mobilization factors. To construct plasmid pfadD, a 1.9-kb fragment that includes the entire fadD gene (VCO395_A1570), including 64 bp upstream of the putative start codon, was PCR amplified using primers fadD5 and fadD6 (Table 2), and the fragment was cloned in plasmid pBR322.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or Source |

|---|---|---|

| V. cholerae strains | ||

| O395 | O1, classical; wild type, Smr | Laboratory collection |

| O395ΔfadD::cat | Derivative of O395 Smr Cmr | This study |

| O395 fadR | O395fadR::pGP704 Smr Apr | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5αλpir | F− (lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1hsdR17 supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 λ::pir | J. J. Mekalanos |

| SM10λpir | thi recA thr leu tonA lacY supE RP4-2-Tc::Mu λ::pir | J. J. Mekalanos |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCVD442 | oriR6K mobRP4 sacB Apr | 10 |

| pGP704 | oriR6K mobRP4 Apr | 28 |

| pKEK162 | pUC118 carrying toxT gene | K. E. Klose (33) |

| pVM7 | pBR327 carrying toxR gene | J. J. Mekalanos (28) |

| ptcpPH | pACYC184 carrying V. cholerae tcpPH | Laboratory collection |

| pSRfadD::cat | pCVD442 carrying fadD::cat | This study |

| pfadD | pBR322 carrying V. choleraefadD gene | This study |

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer use and primer namea | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Cloning/mutant construction | |

| fadD1 (F) | 5′-GATAAACCTTGGCTTTCACG-3′ |

| fadD2 (R) | 5′-ATCCACTTTTCAATCTATATCAAGTTCGGCATCATCAGA-3′ |

| fadD3 (F) | 5′-CCCAGTTTGTCGCACTGATAAGATTCTGGTTTCAGGCTTTA-3′ |

| fadD4 (R) | 5′-AACTGTGCGTCATTTTCTTC-3′ |

| fadD5 (F) | 5′-TCGTTGTAGATCGCCTACTT-3′ |

| fadD6 (R) | 5′-TTGCATGACTACTGCATGAT-3′ |

| fadR1 (F) | 5′-CCGGTTTCGCTGAGAAGTAT-3′ |

| fadR2 (R) | 5′-TTACCGTGTTGAATCGTGAG-3′ |

| fadR3 (F) | 5′-TGTGAGCTGTGTCCA-3′ |

| fadR4 (R) | 5′-TGGCTTTGATTGGTC-3′ |

| cat1 (F) | 5′-ATCCACTTTTCAATCTATATC-3′ |

| cat2 (R) | 5′-CCCAGTTTGTCGCACTGATAA-3′ |

| RT-PCR | |

| ctxA1 (F) | 5′-CTCAGACGGGATTTGTTAGGCACG-3′ |

| ctxA2 (R) | 5′-TCTATCTCTGTAGCCCCTATTACG-3′ |

| tcpA1 (F) | 5′-GTGGTTTCGGCGGGGGTTGT-3′ |

| tcpA2 (R) | 5′-AGCGGGAGCGATGATTTGA-3′ |

| toxT1 (F) | 5′-CAGCGATTTTCTTTGACTTC-3′ |

| toxT2 (R) | 5′-CTCTGAAACCATTTACCACTTC-3′ |

| tcpP1 (F) | 5′-CCAATGAAGCCAGAAAGG-3′ |

| tcpP2 (R) | 5′-CACAGGTAGCAAAGCAAC-3′ |

| toxR1 (F) | 5′-TTAACCCAAGCCATTTCGAC-3′ |

| toxR2 (R) | 5′-GATGAAGGCACACTGCTTG-3′ |

| aphA1 (F) | 5′-ATCTCAGTGGGGGTTATCA-3′ |

| aphA2 (R) | 5′-TGGATGAAAGTGGACAAAA-3′ |

| aphB1 (F) | 5′-GATTGCTCTCCCCTGCTG-3′ |

| aphB (R) | 5′-GTTTCACCTTGGCTGTTGG-3′ |

| 16SrRNA 1 (F) | 5′-CGATGTCTACTTGGAGGTTG-3′ |

| 16SrRNA 2 (R) | 5′-GCTGGCAAACAAAGGATAAGG-3′ |

| fabB1 (F) | 5′-ACTATCCACCAAATACAACGA-3′ |

| fabB2 (R) | 5′-ACCCAGTTCTTTCACATCAG-3′ |

| fadB1 (F) | 5′-TGGAAAATCCGAAAGTAAAA-3′ |

| fadB2 (R) | 5′-GGTGTCTTCTGAGGTGTGTT-3′ |

F, forward; R, reverse.

Construction of deletion and insertion mutants.

Plasmids for generating gene deletions in V. cholerae were constructed in pCVD442, which carries the sacB gene for counterselection (10). Splicing-by-overlap-extension (SOE) PCR (18) was used to generate a deletion/insertion mutation in the fadD gene. Upstream and downstream gene fragments were PCR amplified by using primers fadD1 and fadD2 and primers fadD3 and fadD4, respectively, as listed in Table 2. Another fragment carrying the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene (cat) was also amplified using the primers cat1 and cat2. The three fragments were used to generate a 1.25-kb PCR fragment in which the cat gene was inserted between the fadD upstream and downstream regions. The resulting SOE PCR product was ligated into plasmid pCVD442 to obtain plasmid pSRfadD::cat. The plasmid was conjugally transferred into V. cholerae O395. Deletion mutations arising due to double-crossover events were selected on plates containing sucrose (20%) and chloramphenicol (Cm; 3 μg/ml). The gene deletion was confirmed by PCR of genomic DNA with primers fadD1 and fadD4, flanking the deleted region.

To construct a V. cholerae fadR mutant, a 175-bp fragment spanning 26 bp to 200 bp of the fadR open reading frame (ORF; VCO395_A1490) was PCR amplified using primers fadR1 and fadR2, cloned in the suicide vector pGP704 (Apr), and transferred to V. cholerae O395 (Smr); and Smr Apr exconjugates in which the suicide plasmid had integrated into the V. cholerae chromosome by a single crossover in the fadR gene region were selected (28). The insertion was confirmed using primers fadR3 and fadR4, spanning the fadR gene.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR.

V. cholerae strains were grown under permissive conditions (LB medium, pH 6.6, 30°C) to different growth phases, and RNA was extracted and purified using guanidium isothiocyanate (GITC). The RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase 1 (1 U/μg, amplification grade; Invitrogen) in the presence of an RNase inhibitor (RNasin; Invitrogen). In some experiments, rifampin (50 μg/ml) was added to the cultures and RNA was extracted at different times after addition of rifampin. Semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed using a one step RT-PCR kit (Takara). Genomic DNA served as a positive control, and DNase-treated RNA that had not been reverse transcribed was used as a negative control. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed in triplicate for the genes of interest and 16S rRNA in a one-step reaction using a SYBR green One-Step qRT-PCR kit (Takara) and iCycler IQ5 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). At the end of each cycle, a dissociation curve was generated using software provided with the system to verify that a single product was amplified. The relative levels of expression of the genes of interest were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method described by Livak and Schmittgen (23), where CT is the fractional threshold cycle. 16S rRNA was used as the endogenous control. The statistical significance of the fold differences in expression levels of the genes of interest was calculated using the two-sample t test. A minimum 2-fold difference and a P value of <0.001 were considered significant, unless otherwise stated.

GM1-ganglioside-dependent ELISA.

CT was estimated in culture supernatants and sonicated cell pellets of V. cholerae grown in LB medium (pH 6.6) at 30°C by a GM1-ganglioside-dependent enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Polyclonal rabbit serum directed against purified CT was used as the primary antibody, anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was used as the secondary antibody, and o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD) was used as the substrate for the color reaction. Dilutions of CT of known concentrations (Sigma) were used to quantitate CT in the experimental samples.

Western blot analysis.

Whole-cell lysates and membrane fractions were prepared as described previously (8), and equal amounts of proteins (50 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE. All samples were loaded in triplicate, and parallel lanes were stained with Coomassie blue or transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes in a Transblot apparatus (Bio-Rad). The blots were probed with anti-ToxR or anti-TcpP serum (generous gifts from J. Zhu and J. S. Matson, respectively), followed by HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidene (DAB) in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. The Image J program (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was used to measure the signal intensity of each band on scanned images of the Western blots.

Swarm plate assay.

V. cholerae cells were stabbed into semisolid LB agar plates (pH 6.6) containing 0.3% agar (Difco). The plates were incubated at 30°C for 5 to 16 h, and swarm diameters were measured at regular intervals. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and the mean swarm diameter of each strain was recorded.

LD50 assay.

Fifty percent lethal doses (LD50s) were determined in 4- to 5-day-old suckling mice. The mice were taken from their mothers at least 5 h before infection. V. cholerae strains were grown in LB medium (pH 6.6) at 30°C to the logarithmic phase and diluted as required in saline with blue food coloring. One hundred microliters of three doses of inoculum was delivered intragastrically to five infant mice per dose. Survival of the mice was determined at 20 h. The LD50, representing the means of three independent experiments, was calculated.

RESULTS

Construction and functional analysis of V. cholerae fadD mutant.

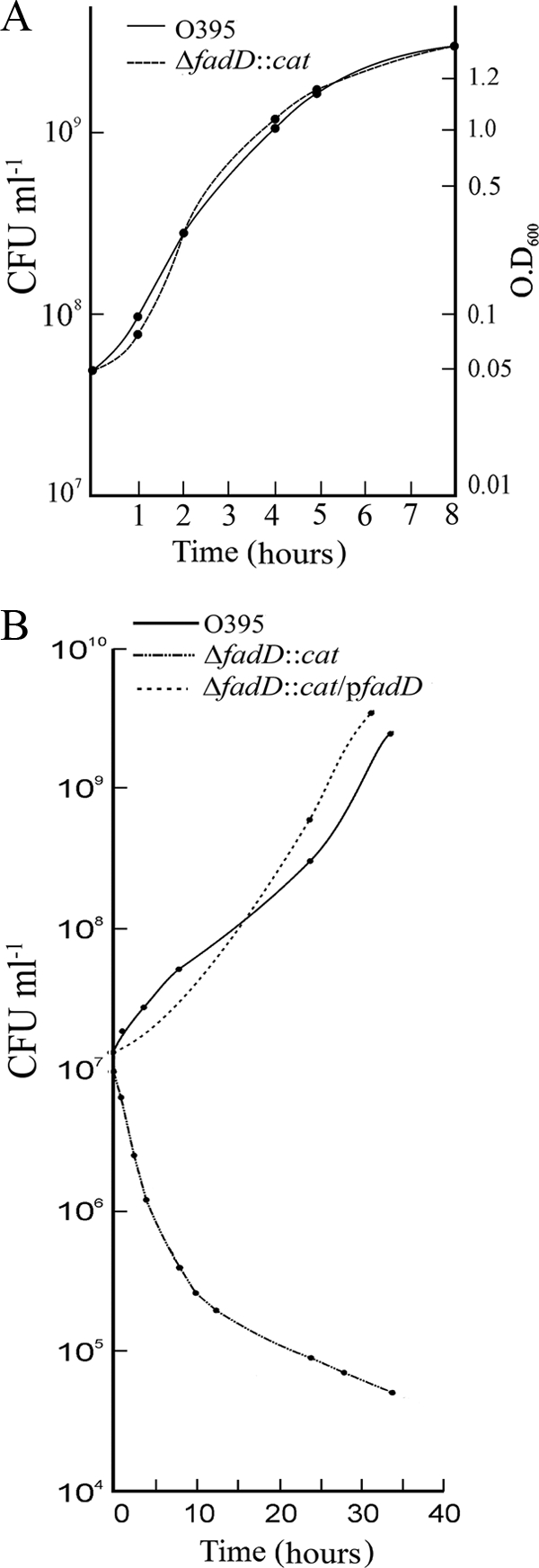

A fadD deletion/insertion mutant (ΔfadD::cat) of the V. cholerae O395 strain was constructed using the suicide vector pCVD442. The mutation was confirmed by PCR with fadD-flanking primers and also by examining phenotypic effects on growth in the presence of exogenous fatty acids. In LB medium, the ΔfadD::cat mutant strain and parental strain O395 exhibited nearly identical growth patterns (Fig. 1A ). However, in M9 medium containing palmitic acid (5 mM) as the sole carbon and energy source, the mutant strain grew poorly compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 1B). The growth defect of the mutant could be complemented by plasmid pfadD, carrying the cloned V. cholerae fadD gene (Fig. 1B). Thus, in V. cholerae, FadD is necessary for growth in the presence of fatty acids as the sole carbon and energy source, as has been reported for E. coli (3) and Sinorhizobium meliloti (37).

FIG. 1.

Growth curves of V. cholerae O395 and ΔfadD::cat. The strains were grown in LB medium (A) or M9 minimal medium containing 5 mM palmitic acid (B), and the numbers of CFU were determined at different times.

CT production is reduced in the V. cholerae fadD mutant.

To examine if FadD has any role in the virulence of V. cholerae, production of CT, the major virulence factor, was examined in the ΔfadD::cat mutant at different stages of growth and the amount produced was compared with the amount produced in parental strain O395. Even under conditions optimum for CT production (LB medium, pH 6.6, 30°C), little CT was detected in the culture supernatants of either O395 or the isogenic ΔfadD::cat mutant until the late exponential phase of growth (Fig. 2). Thereafter, CT production rapidly increased in strain O395 and reached a maximum of about 7.5 μg per 109 CFU by late stationary phase. However, no more than 0.5 μg CT was detected in the fadD mutant under identical conditions (Fig. 2). Thus, inactivation of FadD reduced CT production by more than 95%. Complementation of the V. cholerae ΔfadD::cat mutant with plasmid pfadD carrying the full-length fadD gene restored CT to wild-type levels (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

CT production in V. cholerae wild-type and fadD mutant strains. Strains O395, ΔfadD::cat, and ΔfadD::cat containing plasmid pfadD were grown in LB medium under conditions permissive for CT production (pH 6.6, 30°C), and at different times the level of CT in culture supernatants corresponding to 109 CFU was measured. The data presented are averages of three independent experiments, and error bars represent standard deviations.

Transcriptional repression of ctxAB and tcpA genes in V. cholerae fadD mutant.

To examine if the decrease in CT production observed in the V. cholerae ΔfadD::cat mutant was at the level of transcription, RNA was isolated from the parent and mutant strains in the early (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.3) and late (OD600, 0.7) exponential phases, and the amounts of ctxA-specific mRNA in the two strains were estimated by RT-PCR (Fig. 3). Analysis of the results obtained indicated that the amounts of ctxA mRNA in the wild-type and mutant strains were similar in the early logarithmic phase (Fig. 3A). However, in the late exponential phase, a statistically significant (P = 0.001) difference in the amounts of ctxAB mRNA obtained from the wild-type and fadD mutant strains was observed. After normalization according to the amounts of 16S rRNA present in each RNA population, the amount of ctxA mRNA in V. cholerae O395 was about 7 (±2)-fold higher than that in strain ΔfadD::cat (Fig. 3B and C).

FIG. 3.

Virulence gene expression in V. cholerae fadD mutant. RNA was isolated from V. cholerae O395, ΔfadD::cat, and ΔfadD::cat containing plasmid pfadD; and the strains were grown in LB medium under permissive conditions to an OD600 of 0.3 (A) or 0.7 (B), for estimation of ctxAB, tcpA, and 16S rRNA expression by qRT-PCR. (C) Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed with RNA from cultures grown to an OD600 of 0.7. Expression of each gene was normalized to that of 16S rRNA (C, lower panels). The level of ctxA or tcpA expression in strain O395 was arbitrarily taken to be 100. In panels A and B, the results of three independent experiments are represented as means ± standard deviations. A P value of <0.001 was considered significant.

Since ctxAB gene expression is coordinately regulated with expression of the tcpA gene (38), transcription of tcpA was examined in the V. cholerae ΔfadD mutant. Practically no difference in tcpA expression was observed between V. cholerae O395 and the ΔfadD mutant in the early exponential phase (Fig. 3A). However, in cultures grown to an OD600 of 0.7, the amount of tcpA-specific transcript was about 5 (±2.3)-fold lower in the fadD mutant strain than in the parental strain, O395 (Fig. 3B and C). The difference was statistically significant (P = 0.001). Thus, a mutation in the fadD gene represses the expression of the two major virulence genes of the ToxR regulon, though the repression was more pronounced for ctxAB. RT-PCR analysis indicated that both ctxA and tcpA expression increased to wild-type levels in strain ΔfadD::cat carrying plasmid pfadD (Fig. 3), indicating that the repression of ctxAB and tcpA expression in the fadD mutant was indeed due to disruption of the fadD coding sequence and was not due to an unrecognized secondary mutation.

Expression of regulatory gene toxT.

Expression of the ctxAB and tcpA genes is coordinately regulated by the transcriptional activator ToxT (9). Since both ctxAB and tcpA expression was reduced in the ΔfadD::cat mutant, the effect of the fadD mutation on toxT expression was examined. Strains O395 and ΔfadD::cat were grown under permissive conditions (LB medium, pH 6.6, 30°C), RNA was isolated at different stages of growth, and the amounts of toxT-specific transcript were estimated by RT-PCR. In the wild-type cells, toxT expression occurred at high levels from the early logarithmic (OD600, 0.25) to the mid-logarithmic (OD600, 0.65) phase, after which toxT expression declined (Fig. 4). In the early logarithmic phase (up to an OD600 of 0.25), practically no difference in toxT expression between strains O395 and ΔfadD::cat was detected (Fig. 4A). Subsequently, however, toxT expression in the fadD mutant strain gradually decreased, and by the late logarithmic phase of growth, toxT expression was about 8-fold lower in the ΔfadD::cat strain than in strain O395 (Fig. 4A). Introduction of the full-length fadD gene in plasmid pfadD into the ΔfadD::cat mutant restored toxT expression to wild-type levels (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Expression and stability of toxT mRNA. (A) Strains O395 and ΔfadD::cat were grown in LB medium under permissive conditions, and at different times RNA was isolated for estimation of toxT expression by qRT-PCR. 16S rRNA was taken as the internal control. The amount of toxT mRNA in strain O395 cultures in the early exponential phase (OD600, 0.25) was arbitrarily taken to be 100. (B) RNA was isolated from strains O395 (lane a), ΔfadD::cat (lane b), and ΔfadD::cat/pfadD (lane c) grown to the late exponential phase (OD600, 0.7), for estimation of toxT and 16S rRNA expression by semiquantitative RT-PCR. (C) Rifampin was added to O395 and ΔfadD::cat cultures (OD600, 0.6) to inhibit transcription initiation, and aliquots were collected at different times. RNA was isolated, and toxT-specific transcripts were estimated by qRT-PCR. The amount of toxT mRNA in strain O395 at the time of addition of rifampin (0 min) was arbitrarily taken to be 100. Results of three independent experiments are represented as means ± standard deviations. A P value of <0.001 was considered significant.

To determine if the reduction of toxT-specific transcripts in the ΔfadD mutant was due to decreased synthesis or increased degradation of the toxT mRNA, the O395 and ΔfadD::cat strains were grown to the exponential phase (OD600, 0.6) and treated with rifampin to stop transcription initiation, and RNA was extracted at short intervals thereafter. The amounts of toxT transcript remaining at 2, 4, 6, and 8 min after rifampin addition were measured by qRT-PCR (Fig. 4C). At the time of addition of rifampin (0 min; Fig. 4C), the amount of toxT mRNA was about 6-fold lower in the fadD mutant than in the parent strain. In both the strains, practically no decay of toxT mRNA was observed until after about 6 min of rifampin exposure (Fig. 4C). After 8 min, about 30% of the amount of transcript originally present could be detected in both strains, indicating that there was practically no difference in the stability of toxT mRNA in strains O395 and ΔfadD::cat. The 16S rRNA levels remained unchanged in both strains after up to the 8 min of rifampin exposure examined (data not shown). Thus, the smaller amount of toxT mRNA in the ΔfadD strain was due to reduced de novo synthesis and not accelerated degradation.

To examine if the reduced CT production in the V. cholerae fadD mutant was indeed due to repression of toxT expression, plasmid pKEK162 containing the V. cholerae toxT gene (Table 1) was introduced in the ΔfadD::cat strain as well as in wild-type strain O395, and the CT levels in these cells under optimum conditions were examined. CT production was restored to wild-type levels in strain ΔfadD::cat bearing plasmid pKEK162 (data not shown). These results indicated that FadD does not directly affect expression of ctxAB or tcpA but most likely acts upstream of ToxT.

TcpP and ToxR production is unaffected but TcpP membrane localization is impaired in the fadD mutant.

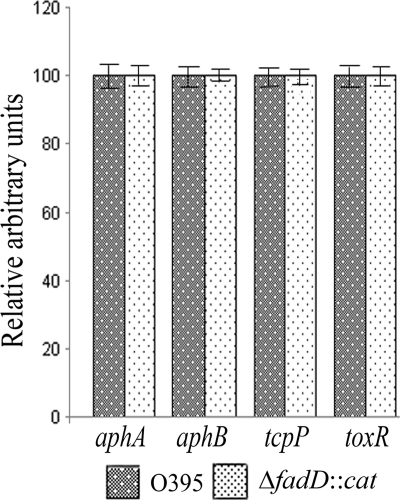

Expression of the toxT gene requires the transcriptional activators TcpP and ToxR, which act synergistically to promote expression from the toxT promoter (7, 27). Since toxT expression was reduced in the V. cholerae fadD mutant in the mid- to late exponential phase of growth, expression of tcpP and toxR was examined in strains O395 and ΔfadD::cat grown to the late exponential phase. No significant difference in expression of tcpP and toxR was detected between strains O395 and ΔfadD::cat (Fig. 5). Also, expression of aphA and aphB, which code for transcriptional activators of tcpP, was similar between strains O395 and ΔfadD::cat (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Expression of virulence regulatory genes. Expression of aphA, aphB, tcpP, and toxR was examined in strains O395 and ΔfadD::cat grown to mid-exponential phase (OD600, 0.5). 16S rRNA expression was used as an internal control. The level of gene expression in strain O395 was arbitrarily taken to be 100. The data presented are averages of three independent experiments, and error bars represent standard deviations. A P value of <0.001 was considered significant.

To examine if overproduction of TcpP and ToxR could complement toxT expression in strain ΔfadD::cat, plasmids ptcpPH and pVM7 carrying the tcpPH and toxR genes, respectively (Table 1), were introduced into strains O395 and ΔfadD::cat, and expression of the virulence genes was examined. In strains O395/ptcpPH and ΔfadD::cat/ptcpPH, the levels of expression of tcpP increased 19-fold and 14-fold, respectively (Fig. 6); however, while the level of toxT expression increased 19-fold in O395/ptcpPH compared to that in O395, only a 5-fold increase was observed in ΔfadD::cat/ptcpPH compared to the level in ΔfadD::cat. Correspondingly, significantly higher ctxA expression was observed in O395/ptcpPH than in ΔfadD::cat/ptcpPH. Thus, overexpression of TcpP in the ΔfadD mutant strain could only partially complement the defect in toxT expression. Overproduction of ToxR from plasmid pVM7 (Table 1) did not restore toxT expression in strain ΔfadD::cat (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Effect of tcpP overexpression on virulence gene expression. Expression of tcpP, toxT, and ctxA was examined in strains O395, ΔfadD::cat, O395/ptcpPH, and ΔfadD::cat/ptcpPH grown under permissive conditions. 16S rRNA expression was used as an internal control. The level of gene expression in strain O395 was arbitrarily taken to be 1.

Next, Western blot analysis was performed to examine the levels of ToxR and TcpP proteins in strains O395 and ΔfadD::cat. The results obtained indicated that there were practically no differences in the levels of TcpP and ToxR proteins in whole-cell lysates of the two strains (Fig. 7A). TcpP and ToxR are transmembrane DNA binding proteins with a cytoplasmic amino terminus and a periplasmic carboxy terminus separated by a short transmembrane domain. The localization of TcpP and ToxR in the V. cholerae fadD mutant was examined by preparing membrane fractions from strains O395 and ΔfadD::cat and subjecting them to Western blot analysis with anti-TcpP and anti-ToxR sera. Quantitation of the signals obtained in three independent experiments using the Image J program (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) indicated that the amounts of ToxR localized in the membrane fractions of strains O395 and ΔfadD::cat were similar in both the early (OD, 0.3) and the late (OD, 0.7) logarithmic phases of growth (Fig. 7B and C). However, although practically no difference in the amounts of membrane-localized TcpP in the early logarithmic phase of the two strains was observed, a significantly smaller amount of TcpP was detected in the membrane fraction of strain ΔfadD::cat than in strain O395 in the late logarithmic phase (Fig. 7B and C). Quantitation of the signals obtained in three independent experiments indicates that, on average, 65% less TcpP was located in the membrane fraction of strain ΔfadD::cat than in that of O395 (Fig. 7C). Thus, although comparable amounts of TcpP protein are produced in strains O395 and ΔfadD::cat, membrane localization of TcpP is impaired in the fadD mutant in the mid- to late logarithmic phase.

FIG. 7.

Western blot analysis. Cell lysate and membrane proteins of strains O395 (lane a) and ΔfadD::cat (lane b) were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-ToxR or anti-TcpP sera. Coomassie blue staining of parallel lanes is shown as a control for protein load (left). (A) Total cell lysates of strains grown to an OD600 of 0.7. Membrane fractions of the strains were grown to an OD600 of 0.2 (B) or an OD600 of 0.7 (C).

It has been reported earlier (2, 26) that under certain conditions, TcpP is proteolytically processed to smaller peptides. No such peptides could be detected in the Western blots with anti-TcpP sera in cell lysates or membrane fractions of ΔfadD::cat. Furthermore, the steady-state levels of TcpP in strains O395 or ΔfadD::cat were similar, since a single band of equal size and intensity was observed in the Western blots of whole-cell lysates of the two strains (Fig. 7A); hence, it is unlikely that TcpP is degraded at an enhanced rate in the ΔfadD mutant.

Effect of fatty acids on virulence gene expression in fadD mutant.

It has earlier been demonstrated that unsaturated long-chain fatty acids strongly repressed expression of ctxAB and tcpA genes when the fatty acids were added exogenously to V. cholerae cultures (6). Since FadD is necessary for CoA ligation and transport of exogenous fatty acids into the bacterial cytoplasm (44), the effect of fatty acids on the residual ctxAB expression in the V. cholerae fadD mutant was examined. Little effect of linoleic acid on ctxA expression in the ΔfadD::cat strain could be detected. However, it is possible that ctxA expression in the ΔfadD::cat strain might be too low (Fig. 3) for the effect of linoleic acid, if any, to be discernible. Expression of toxT from plasmid pKEK162 could increase ctxA expression in the ΔfadD::cat strain to wild-type levels; thus, the effect of linoleic acid on ctxA expression in ΔfadD::cat-carrying plasmid pKEK162 was examined and compared to that in the wild-type strain. Although ctxA expression was reduced in both the strains, the expression was 4- to 5-fold higher in ΔfadD::cat/pKEK162 than in the wild-type strain (Fig. 8). This result suggested that fatty acid transport into the cytoplasm of the ΔfadD::cat/pKEK162 strain might be reduced but not totally abolished. Since V. cholerae O395 has a single annotated fadD gene, it is not clear how fatty acids might be transported into the ΔfadD::cat/pKEK162 strain. One possibility is that exogenous fatty acids might bind to the outer membrane receptor FadL and be transported to the periplasmic space, from where passive diffusion across the cytoplasmic membrane might allow small amounts to enter the cytoplasm even in the absence of concomitant CoA ligation in the ΔfadD mutant. Within the cytoplasm, the free fatty acids might bind to ToxT and render it nonfunctional; indeed, it has been reported that free fatty acids bind efficiently to ToxT (24).

FIG. 8.

Effect of fatty acid on ctxA expression. Strains O395 and ΔfadD::cat/pKEK162 were grown under permissive conditions in LB medium without or with linoleic acid (0.015%) to the late logarithmic phase, and ctxAB expression in the strains was estimated by qRT-PCR. The fold change in ctxA expression in each strain grown without and with linoleic acid is indicated.

Effect of FadD on motility of V. cholerae.

Virulence gene expression and motility are known to be oppositely regulated in V. cholerae (12). Since the major virulence factors were reduced in the ΔfadD::cat strain, motility of the strain was examined by swarm plate assays (Fig. 9). The swarm diameter of ΔfadD::cat (11.6 ± 1 mm) was about 2-fold greater than that of parent strain O395 (5.66 ± 0.5 mm). The swarm diameter of strain ΔfadD::cat complemented with plasmid pfadD was comparable to that of the wild-type strain.

FIG. 9.

Swarming of V. cholerae strains O395, ΔfadD::cat, and ΔfadD::cat/pfadD on motility plates.

LD50 assay.

Since in vitro experiments clearly indicated that production of the major virulence factors is significantly reduced in the ΔfadD strain, the effect of fadD mutation in vivo was examined using the infant mouse cholera model. Four-day-old mice were orally inoculated with V. cholerae wild-type O395 or ΔfadD::cat and observed after 20 h. The LD50 of ΔfadD::cat (6.25 × 108 CFU) was about 225 times higher than that of strain O395 (2.7 × 106 CFU).

FadR has no effect on virulence regulon of V. cholerae.

The primary known function of FadD is the activation of long-chain fatty acids by ligation with CoA. LCFA-CoA binds to and inactivates FadR, a transcriptional regulator that controls expression of several genes and pathways involved in fatty acid metabolism, stress response, the glyoxalate pathway, and other processes (11, 44). To examine if the effect of fadD on the virulence of V. cholerae was mediated by FadR, a V. cholerae O395 fadR mutant was constructed. As expected, expression of fabB, a fatty acid biosynthetic gene known to be activated by FadR, was reduced in the O395 fadR mutant, while expression of fadB, a fatty acid degradation pathway gene known to be FadR repressed, was induced in the fadR mutant strain (Fig. 10). However, no significant difference in expression of the virulence gene ctxA (Fig. 10) or production of CT (data not shown) was observed in the V. cholerae fadR mutant strain. Thus, FadD affects the virulence regulon of V. cholerae through a FadR-independent pathway.

FIG. 10.

Expression of fabB, fadB, and ctxA genes in the V. cholerae fadR mutant. RT-PCR analysis was performed to estimate expression of the genes and 16S rRNA in V. cholerae O395 (lanes a) and the fadR mutant (lanes b).

DISCUSSION

We present evidence from this study that a mutation in the fadD gene encoding a long-chain fatty acyl-CoA ligase has profound effects on the expression of virulence genes, motility, and in vivo lethality of the human pathogen V. cholerae. In the V. cholerae fadD mutant, expression of the major virulence genes ctxAB and tcpA was drastically repressed and a significant reduction in the expression of toxT, encoding the transcriptional activator of ctxAB and tcpA, was observed (Fig. 3 and 4). Expression of toxT from an inducible promoter completely restored CT to wild-type levels in the V. cholerae fadD mutant, suggesting that FadD probably acts upstream of toxT expression. Expression of toxT is activated by the synergistic effect of two transcriptional regulators, TcpP and ToxR, members of the OmpR family of transcription factors (16, 29). Unlike many OmpR family activators, both ToxR and TcpP have a membrane localization domain and a cytoplasmic DNA binding domain. The membrane localization of ToxR has been shown to be necessary for the activation of toxT expression (8); however, the significance of the membrane localization of TcpP is not yet known. In this study we demonstrate that ToxR production and membrane localization are not altered in the V. cholerae fadD mutant (Fig. 7). However, although tcpP gene expression and TcpP protein production are unaffected in the V. cholerae fadD mutant, membrane localization of TcpP is seriously impaired in the mutant strain from the mid-logarithmic phase of growth (Fig. 5 and 7). In the early logarithmic phase, however, no defect in membrane localization of TcpP was observed in the fadD mutant (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, the level of toxT expression in the mutant was comparable to that in the parent strain in the early logarithmic phase, but from the mid-logarithmic phase onwards, the level of toxT expression was much lower in the fadD mutant strain (Fig. 4), concomitant with reduced membrane localization of TcpP (Fig. 7C). These observations suggested a direct correlation between the defect in membrane localization of TcpP and reduced toxT expression in the fadD mutant strain.

What might be the reason for the defect in membrane localization of TcpP in the V. cholerae fadD mutant? The mechanism of interaction of integral or loosely associated membrane proteins with the membrane is not very clear, but there is enough evidence to suggest that membrane localization of a protein or, indeed, the membrane proteome is influenced by the lipid composition of the membrane (35). It has long been known that the membrane lipid composition is altered in an E. coli fadD mutant (43). It would be interesting to examine if there are differences in membrane lipids of V. cholerae O395 and ΔfadD::cat, whether the differences, if any, are growth phase specific, and how they might affect membrane localization of TcpP. It may be mentioned in this context that when the lipid composition in E. coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Streptococcus pyogenes was monitored as a function of growth phase, differences between early, mid-, and late exponential phases were detected (14, 42).

Although the results presented in this report suggest that the defect in membrane localization of TcpP might be responsible for the decrease in toxT expression in the V. cholerae fadD mutant, other possibilities may also be considered. Even though no exogenous fatty acids were added to the growth medium, endogenous fatty acids produced by membrane turnover and fatty acid biosynthesis are thought to be converted to acyl-CoA by FadD, and these fatty acyl-CoA molecules might regulate the activity of some transcription factor that directly or indirectly controls toxT expression. The most important LCFA-CoA-responsive transcription factor is FadR, which has clearly been shown in this study not to have any role in virulence gene expression (Fig. 10). Another fatty acid-responsive transcriptional regulator, FarR, has been identified in E. coli (31). However, no close homolog of E. coli FarR could be identified in the V. cholerae genome sequence database. Still, the possibility that an as yet unknown LCFA-CoA-responsive transcription factor might modulate toxT expression cannot be ruled out at this stage.

It may be noted that a mutation in fadD affects the virulence of several bacterial pathogens, including the plant pathogens S. meliloti (37) and Xanthomonas campestris (1) and the enteric bacterium Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (25). Notably, in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, mutation in fadD represses the expression of hilA, whose product is involved in activating the expression of invasion genes. Although the mechanism of hilA repression by FadD has not yet been identified, it has been shown to be FadR independent. hilA gene expression is controlled by many factors, including several membrane-associated two-component signal transduction systems (41). It would be interesting to examine if membrane localization of these regulators is affected in the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium fadD mutant similarly to the defect in membrane localization of TcpP in the V. cholerae fadD mutant reported in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Biophysics Division for cooperation, encouragement, and helpful discussions during the study. We are grateful to J. J. Mekalanos, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; K. E. Klose, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX; J. S. Matson, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI; and J. Zhu, Department of Microbiology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, for generous gifts of strains, plasmids, and antisera.

The work was supported by a research grant from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Government of India. E.C. is grateful to University Grants Commission for a research fellowship.

Editor: S. M. Payne

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barber, C. E., J. L. Tang, J. X. Feng, M. Q. Pan, T. J. G. Wilson, H. Slater, et al. 1997. A novel regulatory system required for pathogenicity of Xanthomonas campestris is mediated by a small diffusible signal molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 24:555-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck, N. A., E. S. Krukonis, and V. J. DiRita. 2004. TcpH influences virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae by inhibiting degradation of the transcription activator TcpP. J. Bacteriol. 186:8309-8316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black, P. N., C. C. DiRusso, A. K. Metzger, and T. L. Heimert. 1992. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the fadD gene of Escherichia coli encoding acyl coenzyme A synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 267:25513-25520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakrabarti, S., N. Sengupta, and R. Chowdhury. 1999. Role of DnaK in in vitro and in vivo expression of virulence factors of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 67:1025-1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee, A., and R. Chowdhury. 2008. Bile and unsaturated fatty acids inhibit the binding of cholera toxin and Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin to GM1 receptor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:220-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatterjee, A., P. K. Dutta, and R. Chowdhury. 2007. Effect of fatty acids and cholesterol present in bile on expression of virulence factors and motility of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 75:1946-1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Childers, B. M., and K. E. Klose. 2007. Regulation of virulence in Vibrio cholerae: the ToxR regulon. Future Microbiol. 2:335-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford, J. A., E. S. Krukonis, and V. J. DiRita. 2003. Membrane localization of the ToxR winged-helix domain is required for TcpP-mediated virulence gene activation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1459-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiRita, V. J., C. Parsot, G. Jander, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1991. Regulatory cascade controls virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:5403-5407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donnenberg, M. S., and J. B. Kaper. 1991. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive-selection suicide vector. Infect. Immun. 59:4310-4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujita, Y., H. Matsuoka, and K. Hirooka. 2007. Regulation of fatty acid metabolism in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 66:829-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardel, C. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1996. Alterations in Vibrio cholerae motility phenotypes correlate with changes in virulence factor expression. Infect. Immun. 64:2246-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh, A., K. Paul, and R. Chowdhury. 2006. Role of H-NS in colonization, motility and bile dependent repression of virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 74:3060-3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gidden, J., J. Denson, R. Liyanage, D. M. Ivey, and J. O. Lay. 2009. Lipid compositions in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis during growth as determined by MALDI-TOF and TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass. Spectrom. 283:178-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta, S., and R. Chowdhury. 1997. Bile affects production of virulence factors and motility of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 65:1131-1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hase, C. C., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1998. TcpP protein is a positive regulator of virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:730-734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrington, D. A., R. H. Hall, G. Losonsky, J. J. Mekalanos, R. K. Taylor, and M. M. Levine. 1988. Toxin, toxin co-regulated pili and the toxR regulon are essential for Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis in humans. J. Exp. Med. 168:1487-1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horton, R. M., H. D. Hunt, S. N. Ho, J. K. Pullen, and L. R. Pease. 1989. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 77:61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovacikova, G., and K. Skorupski. 1999. A Vibrio cholerae LysR homolog, AphB, cooperates with AphA at the tcpPH promoter to activate expression of the ToxR virulence cascade. J. Bacteriol. 181:4250-4256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovacikova, G., and K. Skorupski. 2001. Overlapping binding sites for the virulence gene regulators AphA, AphB and cAMP-CRP at the Vibrio cholerae tcpPH promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 41:393-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krishnan, H. H., A. Ghosh, K. Paul, and R. Chowdhury. 2004. Effect of anaerobiosis on expression of virulence factors in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 72:3961-3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krokonis, E. S., and V. J. DiRita. 2003. From motility to virulence: sensing and responding to environmental signals in Vibrio cholerae. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:186-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowden, M. J., K. Skorupski, M. Pellegrini, M. G. Chiorazzo, R. K. Taylor, and F. J. Kull. 2010. Structure of Vibrio cholerae ToxT reveals a mechanism for fatty acid regulation of virulence genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:2860-2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lucas, R. L., C. P. Lostroh, C. C. DiRusso, M. P. Spector, B. L. Wanner, and C. A. Lee. 2000. Multiple factors independently regulate hilA and invasion gene expression in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 182:1872-1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matson, J. S., and V. J. DiRita. 2005. Degradation of the membrane-localized virulence activator TcpP by the YaeL protease in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:16403-16408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matson, J. S., J. H. Withey, and V. J. DiRita. 2007. Regulatory networks controlling Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression. Infect. Immun. 75:5542-5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller, V. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in the construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller, V. L., R. K. Taylor, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1987. Cholera toxin transcriptional activator ToxR is a transmembrane DNA binding protein. Cell 48:271-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parsot, C., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1990. Expression of toxR, the transcriptional activator of the virulence factors in Vibrio cholerae, is modulated by the heat shock response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:9898-9902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quail, M. A., C. E. Dempsey, and J. R. Guest. 1994. Identification of a fatty acyl responsive regulator (FarR) in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 356:183-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sack, D. A., R. B. Sack, G. B. Nair, and A. K. Siddique. 2004. Cholera. Lancet 363:223-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuhmacher, D. A., and. K. K. Klose. 1999. Environmental signals modulate ToxT dependent virulence factor expression in V. cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 181:1508-1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sengupta, N., K. Paul, and R. Chowdhury. 2003. The global regulator ArcA modulates expression of virulence factors in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 71:5583-5589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sievers, S., C. M. Ernst, T. Geiger, M. Hecker, C. Wolz, D. Becher, and A. Peschel. 2010. Changing the phospholipid composition of Staphylococcus aureus causes distinct changes in membrane proteome and membrane-sensory regulators. Proteomics 10:1685-1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skorupski, K., and R. K. Taylor. 1999. A new level in the Vibrio cholerae virulence cascade: AphA is required for transcriptional activation of the tcpPH operon. Mol. Microbiol. 31:763-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soto, M. J., M. Fernández-Pascual, J. Sanjuan, and J. Olivares. 2002. A fadD mutant of Sinorhizobium meliloti shows multicellular swarming migration and is impaired in nodulation efficiency on alfalfa roots. Mol. Microbiol. 43:371-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor, R. K., V. L. Miller, D. B. Furlong, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1987. Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84:2833-2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tischler, A. D., and A. Camilli. 2005. Cyclic diguanylate regulates Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression. Infect. Immun. 73:5873-5882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tischler, A. D., S. H. Lee, and A. Camilli. 2002. The Vibrio cholerae vieSAB locus encodes a pathway contributing to cholera toxin production. J. Bacteriol. 184:4104-4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valdez, Y., R. B. Ferreira, and B. B. Finlay. 2009. Molecular mechanisms of Salmonella virulence and host resistance. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 337:93-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van de Rijn, I., and R. E. Kessler. 1979. Chemical analysis of changes in membrane composition during growth of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 26:883-891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weimar, J. D., C. C. DiRusso, R. Delio, and P. N. Black. 2002. Functional role of fatty acyl-coenzyme A synthetase in the transmembrane movement and activation of exogenous long-chain fatty acids. Amino acid residues within the ATP/AMP signature motif of Escherichia coli FadD are required for enzyme activity and fatty acid transport. J. Biol. Chem. 277:29369-29376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang, H., P. Wang, and Q. Qi. 2006. Molecular effect of FadD on the regulation and metabolism of fatty acid in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 259:249-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]