Abstract

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is a leading cause of acute gastroenteritis throughout the world. This pathogen has two type III secretion systems (TTSS) encoded in Salmonella pathogenicity islands 1 and 2 (SPI-1 and SPI-2) that deliver virulence factors (effectors) to the host cell cytoplasm and are required for virulence. While many effectors have been identified and at least partially characterized, the full repertoire of effectors has not been catalogued. In this proteomic study, we identified effector proteins secreted into defined minimal medium designed to induce expression of the SPI-2 TTSS and its effectors. We compared the secretomes of the parent strain to those of strains missing essential (ssaK::cat) or regulatory (ΔssaL) components of the SPI-2 TTSS. We identified 20 known SPI-2 effectors. Excluding the translocon components SseBCD, all SPI-2 effectors were biased for identification in the ΔssaL mutant, substantiating the regulatory role of SsaL in TTS. To identify novel effector proteins, we coupled our secretome data with a machine learning algorithm (SIEVE, SVM-based identification and evaluation of virulence effectors) and selected 12 candidate proteins for further characterization. Using CyaA′ reporter fusions, we identified six novel type III effectors and two additional proteins that were secreted into J774 macrophages independently of a TTSS. To assess their roles in virulence, we constructed nonpolar deletions and performed a competitive index analysis from intraperitoneally infected 129/SvJ mice. Six mutants were significantly attenuated for spleen colonization. Our results also suggest that non-type III secretion mechanisms are required for full Salmonella virulence.

Salmonella enterica serovars are intracellular pathogens that can cause gastroenteritis and typhoid fever. In the developing world, they are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality resulting from dehydration and untreated sepsis (21-22, 43). Salmonella actively secretes effector proteins into the host cell cytoplasm to create a replicative niche and inhibit the immune system. Many of these effectors are delivered by one of two type III secretion systems (TTSS), which are encoded on Salmonella pathogenicity islands 1 and 2 (SPI-1 and SPI-2, respectively) (24). The SPI-1 TTSS facilitates host cell entry and inflammation, whereas SPI-2 mediates intracellular survival (19, 51). Both SPI-1 and SPI-2 are required in a mouse model of persistent infection (35). While over 30 TTSS effectors have been identified to date (5, 25, 42, 58-59), the list is thought to be an underestimate of the true effector repertoire because several virulence phenotypes are dependent on TTS but are not linked to any known effectors (34, 57).

A proteomic study of Escherichia coli O157:H7 identified over 31 new type III effectors. This analysis took advantage of a sepL mutant that secreted effector proteins into culture medium in vitro (60). E. coli SepL interacts with Tir (63), a type III effector that inserts into the host plasma membrane and functions as a receptor for the bacterial protein intimin (31). The SepL-Tir complex is thought to occlude secretion until the translocon (host membrane pore) is assembled, thereby ensuring that Tir is translocated before any other effectors. SepL is a homolog of Salmonella SsaL, and a recent study found that an ssaL mutant secreted proteins into medium (68). However, the proposed mechanism regulating Salmonella TTS is different from that in the E. coli SepL model. SsaL is believed to form a complex with two other proteins, SpiC and SsaM. The current model suggests that this heterotrimeric complex responds to intracellular pH and permits secretion of translocon proteins at acidic pH (intravacuolar pH) while inhibiting secretion of effector proteins. When the SPI-2 TTSS gains access to the neutral pH of the eukaryotic cytoplasm, the SsaL-SpiC-SsaM complex dissociates, and effector translocation ensues (68). Because an ssaL mutation relieved the pH-dependent inhibition of effector secretion, we hypothesized that culture supernatant from a Salmonella ssaL mutant could be analyzed by proteomics to discover novel effector proteins.

In this study, we used proteomics to identify effector proteins secreted by S. enterica serovar Typhimurium under growth conditions that induced expression of the SPI-2 TTSS and its many effectors (9-10, 68). A global evaluation of SPI-2 effector secretion has not been previously reported. To support our conclusions, we compared the secretome of the wild-type (WT) parent strain to the secretomes of strains missing essential (ssaK::cat) or regulatory (ΔssaL) components of the SPI-2 secretion apparatus. Proteins were enriched by reverse-phase resins and identified by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Interpretation of the results was aided by a machine learning algorithm (SIEVE, SVM-based identification and evaluation of virulence effectors) that scored each protein for its probability of being a type III effector (50). This approach proved to be an excellent strategy for the identification and discovery of secreted effector proteins. We identified eight novel effectors and approximately 80% of the previously reported repertoire encoded by S. Typhimurium ATCC 14028. Excluding translocon components, all of the type III effectors were secreted exclusively or in greater abundance by the ssaL mutant, suggesting that ssaL and sepL are functional orthologs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture conditions, strains, and plasmids.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (ATCC 14028) was used as the wild-type strain. All bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or mLPM (see below for contents) at 37°C on a shaker set to 300 rpm. Carbenicillin, kanamycin, and chloramphenicol were used at 100, 60, and 30 μg/ml, respectively. J774 cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 using Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, sodium pyruvate, sodium bicarbonate, and nonessential amino acids. Lambda red recombination (12) was used to construct the gene deletions and sseJ::hemagglutinin (HA) strains. Deletions were constructed using PCR products derived from primers listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material and the pKD4 or pKD13mod templates. All constructs were transduced with bacteriophage P22 and resolved to create in-frame, nonpolar deletions. sseJ::HA was derived from a PCR product using primers 3 and 4 with the pNFB15 template (received from Lionello Bossi), which generated a C-terminal, doubly HA-tagged SseJ followed by a nonresolvable kanamycin marker. This construct was P22 transduced into the wild-type, ΔssaL, and ssaK::cat (18) backgrounds so that they each expressed a chromosomal copy of sseJ::HA under the control of its native promoter. The sseJ::HA, ΔssaL sseJ::HA, and ssaK::cat sseJ::HA strains were transformed with the pBADssrB plasmid (65) to generate the strains used for proteomic analysis. For CyaA′ secretion assays, open reading frames were PCR amplified from S. Typhimurium using primer sets described in Table S2 in the supplemental material. Each forward primer was designed to anneal ∼20 bp upstream of its start codon to encode the putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence. Flanking 5′ XbaI and 3′ PvuII or EcoRV restriction sites enabled directional cloning into pMJW1753 (18) cut with XbaI and SmaI. The resulting C-terminal CyaA′ fusions were verified by automated sequencing and transformed into the wild-type, ssaK::cat, and invA::cat (18) backgrounds. SssA and SssB::CyaA′ fusions were transformed into two additional backgrounds: ΔinvA ssaK::cat and ΔinvA ssaK::cat ΔflgB. Transcription was driven by the constitutive lac promoter in Salmonella, and expression was confirmed by Western blotting against CyaA′ (Santa Cruz; 1:1,000).

mLPM.

mLPM contained 5 mM KCl, 7.5 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.5 mM K2SO4, 0.3% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.00001% thiamine, 0.5 μM ferric citrate, 8 μM MgCl2, 337 μM PO43−, and 80 mM MES [2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid]-free acid adjusted to pH 5.8 with NaOH.

Sample preparation for LC-MS/MS.

Bacteria were grown overnight in 50 ml LB broth. The following day, bacteria were washed three times in mLPM and then diluted 1:10 to a final volume of 500 ml. Carbenicillin (100 μg/ml) was added to select for inoculated bacteria, and one tablet of protease inhibitor cocktail without EDTA (Roche) was added to inhibit protein degradation. At the 4-, 8-, and 16-h time points, the medium was centrifuged for 10 min at 5,000 × g to pellet the bacteria. Spent medium was filtered through a 0.45-μm Durapore filter assembly (Millipore) and pumped at ∼1 ml/min overnight at 4°C through serial 6-ml columns containing 50 mg of C4, C8, and C18 solid-phase extraction (SPE) resins (Strata and Supelco). Prior to loading of the samples, SPE columns were conditioned with 100% methanol followed by 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). After sample processing, SPE columns were washed with 95:5 H2O-acetonitrile (ACN), 0.1% TFA and stored at −20°C until they were eluted with 80:20 ACN-H2O, 0.1% TFA. Eluted samples were concentrated with a SpeedVac, quick-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until needed. Protein concentration was assessed by a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Pierce). When required, tryptic digests were performed as previously described (1, 3).

Capillary LC-MS/MS analysis.

The high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system and method used for nanocapillary liquid chromatography have been described in detail elsewhere (1, 52). Analysis was performed using an LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) with electrospray ionization. The HPLC column was coupled to the mass spectrometer using an in-house-manufactured interface. The heated capillary temperature and spray voltage were 200°C and 2.2 kV, respectively. Data acquisition began 20 min after the sample was injected and continued for 100 min over an m/z range of 400 to 2,000. For each cycle, the six most abundant ions from MS analysis were selected for MS/MS analysis, using a collision energy setting of 35 eV. A dynamic exclusion time of 60 s was used to discriminate against previously analyzed ions. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate.

Data analysis.

Peptides were identified by using SEQUEST to search the mass spectra from LC-MS/MS analyses. These searches were performed using the annotated S. Typhimurium LT2 FASTA data file, containing 4,550 protein sequences provided by the J. Craig Venter Institute, a standard parameter file with no modifications to amino acid residues. The searches were allowed for all possible peptide termini, i.e., not limited by tryptic terminus state. Results were filtered using a modification of criteria established by Washburn et al. (64) and a statistical approach to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications (30), with a score of at least 0.9 used to increase confidence in identified peptides. An estimate of the false-positive rate was obtained by searching against a reversed FASTA database, as described elsewhere (48). An estimated false-discovery rate of 2% was determined by using the combined filtering rules. The number of peptide observations from each protein (spectral count) was used as a rough measure of relative abundance. Multiple charge states of a single peptide were considered individual observations, as were the same peptides detected in different mass spectral analyses. Similar approaches for quantitation have been described previously (1-3). Spectral counts for peptide identifications were summed across technical replicates and were analyzed separately for the eluents of the C4, C8, and C18 SPE columns. The results of the C4 and C8 columns were similar, and C18 column yields were sparse to null. Therefore, results from the C4 and C8 column eluents were combined, and C18 eluents were not used in subsequent analyses.

The accurate mass and elution time (AMT) tag approach (4, 54-55) was used as a complementary approach to increase the sensitivity of peptide detection and as a secondary method of relative peptide quantification. For this method, a reference database containing accurate peptide masses and normalized LC elution times was generated from 72 LC-MS/MS analyses. C18 SPE column data were excluded from the AMT database due to the paucity of peptides observed. The corresponding peptide sequences were determined using SEQUEST. Peptides were identified in subsequent high-throughput LC-MS analyses by matching masses and elution times observed in the high-resolution MS spectra to those contained in the reference database of peptides. Quantitation was based on measuring the mass spectral peak intensity of each peptide. This approach was enabled by published and unpublished in-group tools which can be downloaded from http://omics.pnl.gov. The software program DAnTE (49) was used to perform the abundance roll-up procedure to convert peptide information into protein information, allowing relative protein abundances to be inferred. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel. Hierarchical clustering and construction of heat maps were carried out using OmniViz 6.0.

Western blotting of secretome samples.

To evaluate cellular protein expression, pelleted bacteria were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), normalized to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600), and lysed in Laemmli sample buffer, and a volume corresponding to ∼1 × 105 bacteria was resolved by SDS-PAGE. To evaluate secretion, a 20-ml aliquot of spent, filter-sterilized medium was taken from each of the samples. Protein was precipitated overnight at 4°C in 20% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 30 min the following day. Precipitated protein pellets were washed twice in ice-cold acetone, placed on a 95°C heat block to evaporate solvent, and then suspended in Laemmli sample buffer. If a sample turned yellow, acidity was neutralized by adding 1 M Tris (pH 9) until the sample turned blue. Medium samples were normalized to the number of bacteria in the pellet and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Western blots using antibodies to DnaK (Assay Design; 1:10,000) and the C-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) tag of SseJ (Covance; 1:1,000) were used to detect intracellular and secreted proteins, respectively.

CyaA′ secretion assays.

CyaA′ secretion assays were performed as previously described (18). Secretion was evaluated under SPI-1 or SPI-2 gene-inducing conditions using the wild-type, invA::cat, and ssaK::cat genetic backgrounds. InvA and SsaK are structural components of the SPI-1 and SPI-2 TTSS, respectively. To induce SPI-1 expression, overnight LB cultures were diluted 1:33 in LB broth and incubated at 37°C with shaking until the cultures reached late log phase. J774 cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 for 1 h, and cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Assay Designs). An effector was considered to be secreted by the SPI-1 TTSS if the cAMP responses between the wild-type (WT) and invA::cat backgrounds were ≥10-fold different. To induce SPI-2 expression, bacteria were grown to late stationary phase overnight in LB broth. J774 cells were infected at an MOI of 250 for 6 h. An effector was deemed secreted by the SPI-2 TTSS if the cAMP responses between the WT and ssaK::cat backgrounds were ≥10-fold different. Three biological replicates were performed for each CyaA′ fusion, and error bars were calculated by determining standard errors of the means.

CI infections.

We performed a mixed-infection competitive-index (CI) experiment using 6- to 8-week-old female 129/SvJ mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). This protocol is based upon the work of H. Yoon, C. Ansong, J. N. Adkins, and F. Heffron (submitted for publication) and is summarized here. Using lambda red recombination, we designed each Salmonella mutant and a wild-type control with a unique scar sequence so that relative quantities could be analyzed in a mixed infection. Bacteria were grown overnight in LB broth and were washed three times in PBS the following day. Equal numbers of bacteria were mixed together, and 15 129/SvJ mice were infected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with a total of 104 CFU. Spleens were harvested on days 1, 4, and 7 postinfection and plated on LB agar for overnight growth at 37°C, where they yielded isolated colonies of approximately the same size. The following day, bacteria were harvested and normalized to an OD600, and the unique scar sequence encoded by each Salmonella strain was amplified by nested PCR using primers ScarF and ScarR. The resulting PCR products containing unique scar sequences were purified (Qiagen), normalized to concentration, and analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) to determine the quantity of each mutant relative to that of the wild-type reference strain. qRT-PCR was performed using primer ScarR with primers 67 to 74 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), SYBR green reagent (Applied Biosystems), and a StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The CI is equal to  , the ΔCt (change in threshold cycle) is equal to

, the ΔCt (change in threshold cycle) is equal to  , and E is equal to e1/−slope, where E is the amplification efficiency for each primer pair derived from the slope of a calibration curve. E values ranged between 1.7 and 1.9. Statistical significance was calculated using Student's t test.

, and E is equal to e1/−slope, where E is the amplification efficiency for each primer pair derived from the slope of a calibration curve. E values ranged between 1.7 and 1.9. Statistical significance was calculated using Student's t test.

RESULTS

Rationale for medium and strains used in this study.

The overall objective of this study was to identify effectors secreted into medium designed to induce SPI-2 expression. mLPM is a defined, acidic, low-phosphate, low-magnesium minimal growth medium that induces SPI-2 expression (8-10, 14, 44).

Three different isogenic S. Typhimurium ATCC 14028 strains were used for proteomic analysis: the wild-type (WT), ssaK::cat, and ΔssaL strains. To each of these strains we added a C-terminal, HA-tagged copy of SseJ to monitor secretion of a known SPI-2 effector by Western blotting. SsaK is an essential component of the SPI-2 secretion apparatus, and the ssaK::cat mutant is deficient for SPI-2 TTSS. As mentioned previously, ssaL deletion is thought to disrupt the SpiC-SsaM-SsaL complex and enable secretion of type III effector proteins at acidic pH in vitro (68). Secretion of SseJ into mLPM at pH 5.8 was confirmed (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

SsrB is a positive, global regulator of SPI-2 and of virulence factors spread throughout the chromosome (36, 65). Despite the use of medium that induced SPI-2 gene expression (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), we hypothesized that SsrB overexpression might increase the probability of identifying novel type III effectors. SsrB overexpression likely causes self-activation via spontaneous dimerization and self-phosphorylation, a phenotype that has been previously demonstrated for the PhoP two-component regulator (39). We therefore overexpressed SsrB in a parallel set of samples to drive effector synthesis. To accomplish this, all strains were transformed with the pBADssrB plasmid, which encodes an arabinose-inducible copy of ssrB (65).

Assessing secretion by Western blotting.

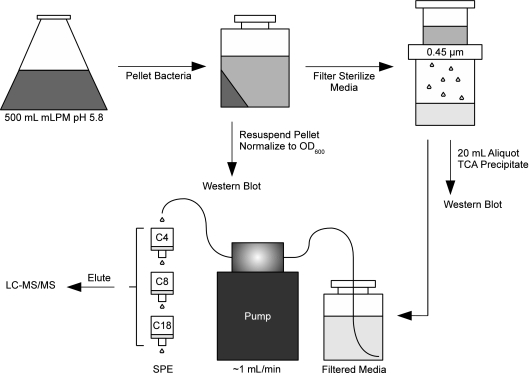

Samples were prepared by growing cultures for 4, 8, or 16 h in mLPM with and without 0.2% arabinose. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatant was filter sterilized using a low-protein-affinity membrane (Fig. 1). At each time point, we evaluated the cell pellet and supernatant for intracellular and secreted levels of the tagged secreted effector, SseJ::HA, by Western blotting. We also probed for the cytoplasmic protein DnaK to verify retention of this protein in the cell pellets.

FIG. 1.

Sample preparation of extracellular proteins for LC-MS analysis. Five-hundred-milliliter mLPM culture volumes were grown for 4, 8, or 16 h. The bacterial pellet and an aliquot of filter-sterilized medium were analyzed by Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods. The remaining medium was then pumped through serial C4, C8, and C18 solid-phase extraction (SPE) resins. Samples were eluted and then analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

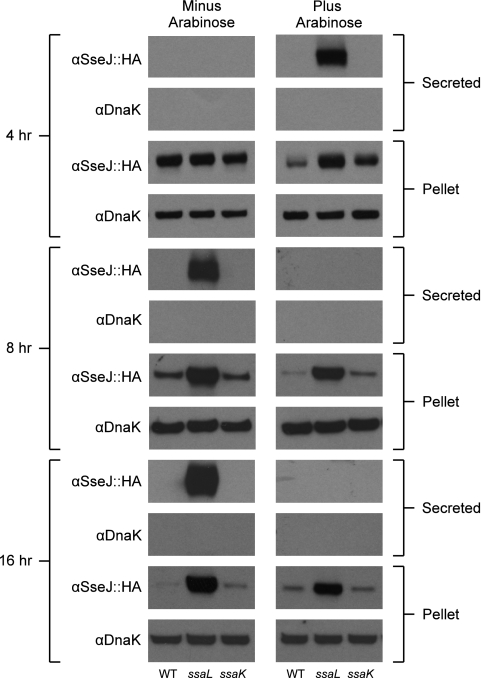

DnaK was not observed in any of the secreted fractions (Fig. 2), suggesting that the bacteria maintained cell integrity throughout the course of the experiment. In samples grown without arabinose, SseJ was detected in the supernatant at 8 and 16 h but not at 4 h. Secretion of SseJ was observed only in the ssaL mutant, not the parental strain nor the ssaK mutant (Fig. 2). Intracellular levels of SseJ decreased over time in the wild type and ssaK mutant but not in the ssaL mutant (Fig. 2). Given the lack of DnaK in the secreted fractions, these results argue against cell lysis and suggest that SsaL can regulate sseJ transcription and/or translation. Further experiments are needed to determine how this repression takes place and whether it affects other type III effectors. When pBADssrB was induced with arabinose, SseJ secretion was still dependent upon the ssaL deletion. However, SseJ secretion was observed only at 4 h, not at 8 or 16 h (Fig. 2). Collectively, these results suggest a complex, poorly understood process of regulation and feedback. Nonetheless, the results shown in Fig. 2 supported our experimental design because SseJ secretion was restricted to the ssaL mutant and because two novel effectors were exclusive to SsrB overexpression (see below).

FIG. 2.

Western blots of secretome samples illustrating secretion from the ssaL mutant. At each time point (4, 8, and 16 h), culture supernatants were filter sterilized and TCA precipitated to concentrate secreted proteins. The bacterial pellet (∼1 × 105 CFU) and TCA precipitate were analyzed by Western blotting to evaluate SseJ secretion and retention of the intracellular protein DnaK in the cell pellet.

Characterization of the secretome.

Filtered culture supernatants from each strain were applied to serial C4, C8, and C18 solid-phase extraction (SPE) columns to collect proteins for LC-MS/MS analysis (Fig. 1). Data from LC-MS/MS were analyzed with SEQUEST, which matches mass spectra to peptide sequences. Protein abundance was estimated by summing the numbers of peptide mass spectra corresponding to a particular protein (16). This approach, referred to as spectral counting, is widely used in the proteomics community (1, 3, 26, 40). SEQUEST analysis with our study conditions (72 LC-MS/MS data sets) yielded ∼1,400 unique secreted peptides that mapped to ∼434 proteins. To increase confidence in the identifications, we limited our analysis to those proteins identified by two or more peptides (n = 300) (see Table S3 in the supplemental material).

As an alternative to spectral counting, we also employed the accurate mass and elution time (AMT) tag approach (69), which reduces under-sampling and provides mass spectral peak area/height calculations for use as relative peptide abundance measurements. When the results of the analyses were compared to each other, the relative protein expression patterns between the AMT tag and spectral counting methods were in surprisingly close agreement (raw and processed results may be obtained from http://www.sysbep.org). The low level of complexity of the secretome compared to that of a typical cellular proteome may account for this observation. As a result, under-sampling of the MS/MS data was not a significant factor in this study and improved confidence in the peptide identifications. For these reasons, and because of its broader use within the proteomics community, only results derived from spectral counting are presented here.

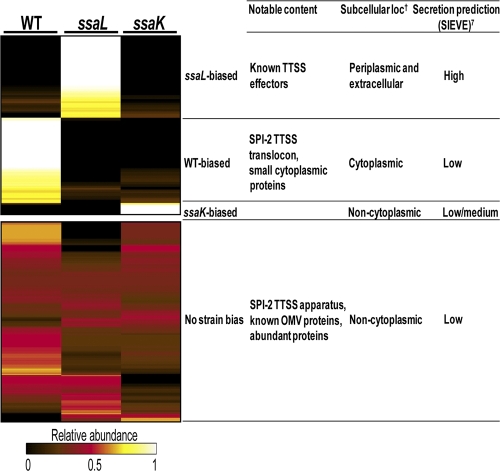

Protein secretion patterns.

To normalize the LC-MS/MS data for each protein, summed spectral counts observed for a single strain were divided by the total numbers of peptides observed for all strains to give relative abundance values ranging from 0 to 1. A secreted protein was considered strongly biased for a particular strain if its relative abundance was ≥0.7. The remaining proteins were considered nonbiased, with roughly equal numbers observed for all strains. Identified proteins were also assessed with the PSORTb algorithm (66) to predict subcellular localization and by a computational method that predicts TTS (SIEVE [http://www.sysbep.org/sieve/]) (50). A SIEVE score of ≥1 indicated that a protein has a reasonable probability of being a type III effector. These and other notable features are highlighted in Fig. 3 and Table 1 and are discussed next.

FIG. 3.

Heat map representation of peptide identifications displaying strain bias. Columns indicate the strain and normalized spectral counts for each observed protein. To normalize the data, spectral counts from each strain were summed across all time points with and without SsrB overexpression and then divided by the sum of values across that protein row, resulting in a scale ranging from 0 (least abundance) to 1 (highest abundance). A protein was considered biased for observation in a strain if its relative abundance value was ≥0.7. About 50% of proteins were observed at similar levels in all strains. Notable features of the strain-biased groups are indicated to the right of each grouping.

TABLE 1.

Properties of proteins identified in the secretome

| Property | WT bias | ssaL bias | ssaK bias | No bias | Secretome | Genomea | SPI-2 effectorsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean molecular mass in kDa | 24 | 32 | 35 | 26 | 27 | 35 | 39 |

| Mean SIEVE score | −0.46 | 0.90 | 0.41 | −0.09 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 2.18 |

| No. of proteins among 200 most abundantly expressed proteins (% of total)c | 21 (31) | 3 (5) | 1 (11) | 38 (24) | 63 (21) | NA | 0 (0) |

| Mean peptide count | 3 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 4 | NA | 9 |

| Mean spectral count | 10 | 31 | 3 | 90 | 57 | NA | 69 |

| Total no. of proteins | 68 | 65 | 9 | 158 | 300 | 4,525 | 20 |

| No. of proteins by subcellular location (% of total)d | |||||||

| Cytoplasm | 36 (53) | 14 (22) | 2 (22) | 51 (32) | 103 (34) | 1819 (40) | 8 (40) |

| Inner membrane | 11 (16) | 9 (14) | 0 (0) | 18 (11) | 37 (12) | 1103 (24) | 2 (10) |

| Periplasm | 0 (0) | 13 (20) | 1 (11) | 21 (13) | 35 (12) | 158 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Outer membrane | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 2 (22) | 17 (11) | 21 (7) | 102 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Extracellular | 1 (1) | 7 (11) | 4 (44) | 4 (3) | 16 (5) | 68 (2) | 6 (30) |

| Unknown location | 19 (28) | 21 (32) | 0 (0) | 47 (30) | 87 (29) | 1275 (28) | 4 (20) |

NA, not applicable.

Known SPI-2 TTSS effectors and translocon proteins.

Previously observed in Salmonella proteomic studies.

Predicted using the PSORTbv3.0 algorithm.

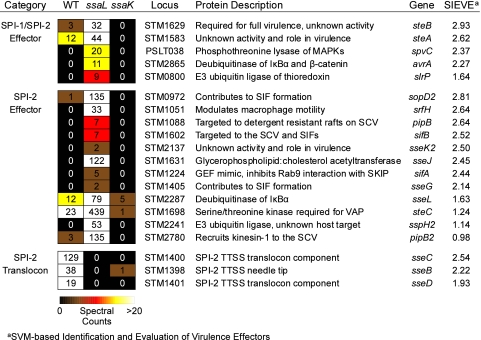

(i) Identification of known type III effectors.

We observed 15 known effectors secreted exclusively by the SPI-2 TTSS (SopD2, SrfH, PipB, SifB, SseK2, SseJ, SifA, SseG, SseL, SteC, SspH2, PipB2, SseC, SseB, and SseD) and five additional effectors secreted by both the SPI-1 and SPI-2 TTSS (SteB, SteA, SpvC, AvrA, and SlrP) (Fig. 4). Based on statistical analyses, these effectors fell into two distinct strain-specific categories, ssaL dependent and WT dependent. All effectors were ssaL dependent except the translocon proteins SseBCD, which fell into the WT-dependent category (Fig. 4). Taken together, these results support and extend the model of Yu et al. (68) where SsaL inhibits the secretion of TTSS effectors, but not translocon proteins, at acidic pH.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of known type III effector identifications. Spectral-count heat map of known type III effectors identified in the secretome. Columns indicate the strain and spectral counts for each observed protein across all time points with and without SsrB overexpression. Proteins were binned by their association with the SPI-1/SPI-2 or SPI-2 TTSS. Known TTSS effectors, but not translocon components, were observed primarily from the ssaL mutant. MAPKs, mitogen-activated protein kinases; SIF, Salmonella-induced filament; SCV, Salmonella-containing vacuole; GEF, guanine nucleotide exchange factor; SKIP, Sifa kinesin interacting protein; VAP, vacuolar actin polymerization.

(ii) ssaL bias.

Sixty-five proteins were biased for identification in the ssaL mutant (Fig. 3 and Table S4 in the supplemental material), 17 of which were known SPI-2 effectors. Of the 65 ssaL-biased proteins, 89% had zero peptides or one peptide detected in the ssaK mutant. Furthermore, ssaL-biased proteins had significantly higher SIEVE scores than the rest of the secretome (mean, 0.9 versus 0.06; P = 7 × 10−7) and the genome (mean, 0.9 versus 0; P = 5 × 10−14), suggesting that a significant proportion of these proteins may be novel secreted effectors (Table 1). Overall, these proteins were not significantly different from the rest of the secretome or genome in terms of molecular weight. In terms of subcellular localization, 22% of ssaL-biased proteins were predicted to be cytoplasmic, compared to 34% for the whole secretome (P = 0.05, χ2) and 40% for the genome (P = 0.002, χ2). The ssaL-biased subset was also enriched in predicted periplasmic proteins compared to the ssaL-biased subsets of the secretome and genome. Only three proteins in the ssaL subset were among the 200 most abundantly expressed in Salmonella under similar growth conditions (1), further suggesting that cell lysis was minimized during growth and sample preparation (Table 1).

(iii) WT bias.

In the WT subset, 68 proteins were observed at higher levels than were observed in mutant samples (Fig. 3 and Table S4 in the supplemental material). Eighty four percent of these proteins in the WT subset had zero (42 proteins) or one (15 proteins) peptide identification in the ssaK mutant. The WT-biased subset had a mean SIEVE score of −0.46, which indicates, overall, a low probability of TTS. However, this group also included the SPI-2 translocon components SseB, SseC, and SseD, confirming the Yu et al. model as previously described (68). Unlike the ssaL-biased subset, which had a molecular mass distribution similar to that of the genome, the WT-biased proteins had a higher proportion (63%) of small cytoplasmic proteins with molecular masses of <20 kDa. The proportion of proteins that are <20 kDa as predicted from the genome sequence is 28%. Notably, 21 of the WT-biased proteins were among the top 200 most highly expressed Salmonella proteins observed under similar growth conditions (Table 1) (1). Thus, the WT-biased group was enriched for small, abundant, intracellular proteins. It is intriguing and unclear why small, cytosolic proteins predominated in the WT-biased group.

(iv) ssaK bias.

Nine proteins fell into the ssaK-biased category (Fig. 3 and Table S4 in the supplemental material). This group was enriched for outer membrane and extracellular proteins and had a SIEVE score of 0.41, which indicates a low-to-moderate probability of TTS (Table 1).

(v) Proteins with no strain differences observed.

One hundred fifty-eight proteins were observed at nearly equal levels in all strain backgrounds, including components of the SPI-2 TTS apparatus, SsaC, SsaG, and SsaI (Fig. 3 and Table S4 in the supplemental material). However, 76% of this group had two or more peptide identifications in the ssaK mutant, and the mean SIEVE score was −0.09, indicating that the majority of identified proteins were unlikely to be type III effectors. Note that the secretome was prepared from strains grown in acidic minimal medium, i.e., inducing conditions for SPI-2. Compared to the genome, this subset was enriched for proteins that are highly expressed under these growth conditions (n = 38), and a significant fraction was periplasmic or outer membrane localized (24% versus 6% for the genome; P = 2 × 10−20, χ2) (Table 1). Flagellins (FliC and FljB) were also abundant in this subset, confirming a previous Salmonella study that analyzed the content of LB culture supernatants (32). Collectively, these observations suggest that abundant outer membrane and periplasmic proteins belong to this group. This group was also notable for the presence of PagC, PagD, PagK, and SrfN, of which PagC, PagD, and SrfN have been reported to be required for virulence (7, 23, 46-47). We determined that these proteins are secreted to host cells in outer membrane vesicles (OMV) (Yoon et al., submitted). Thus, OMV may have contributed to the identification of other proteins.

Selection of candidate secreted proteins.

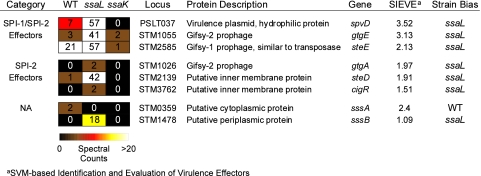

Based on the secretion patterns exhibited by known SPI-2 type III effectors (presence in the ΔssaL and/or WT background, low/no detection in the ssaK mutant, and SIEVE scores of ≥1) (Fig. 4), 12 candidate proteins were tested for secretion into host cells. The candidate proteins were PSLT037 (SpvD), STM0359, STM1026 (GtgA), STM1055 (GtgE), STM1087 (PipA), STM1478 (YdgH), STM1599 (PdgL), STM1809, STM2139, STM2585, STM3762 (CigR), and STM4082 (YiiQ).

Confirmation of novel secreted proteins.

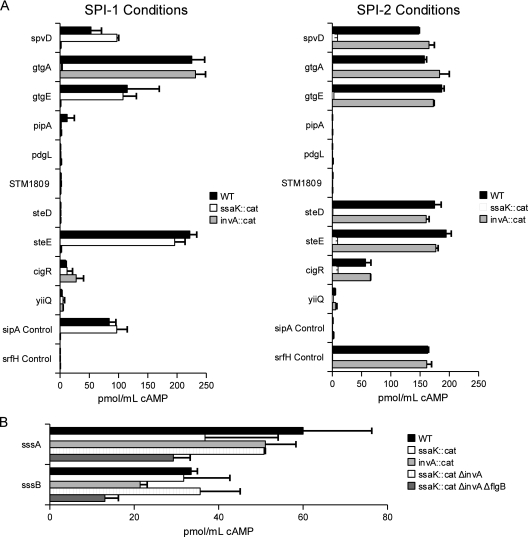

To determine if candidate effectors were secreted into host cells, we constructed a cyaA′ fusion to each open reading frame (18, 56). Expression was verified by Western blotting (data not shown), J774 macrophage-like cells were infected, and cAMP levels were measured. We identified three novel proteins secreted by the SPI-2 TTSS (GtgA, CigR, and STM2139) and three secreted by both the SPI-1 and SPI-2 TTSS (SpvD, GtgE, and STM2585) (Fig. 5 and 6). In accordance with an existing naming scheme for Salmonella type III effectors (18), we designated STM2139 SteD (Salmonella translocated effector D) and STM2585 SteE. Notably, each of these novel effectors was ssaL biased, an observation that further supports the role of SsaL in regulating SPI-2 TTS. In addition, two proteins were secreted independently of TTS: STM0359, which we designated SssA (Salmonella secreted substrate A), and YdgH, a conserved unknown protein that we designated SssB (Salmonella secreted substrate B) (Fig. 5 and 6). Of the remaining four candidates, we observed no secretion into host cells. There are several reports that suggest that secretion may be cell or tissue specific (17, 20), but due to the general success of the screen, we did not exhaustively try alternative methods. As a result, some of the unconfirmed candidates may in fact be secreted but not under the conditions described here. Nevertheless, 8 out of 12 candidates were confirmed as novel secreted substrates, demonstrating an unprecedented level of accuracy in our approach.

FIG. 5.

Discovery of novel secreted effectors. Spectral-count heat map for 8 novel secreted effectors. Columns indicate the strain and spectral counts for each observed protein across all time points with and without SsrB overexpression. Proteins were binned by their secretion via the SPI-2 TTSS or both the SPI-1 and SPI-2 TTSS. NA, not applicable (secreted independently of SPI-1, SPI-2, and flagellar TTSS).

FIG. 6.

CyaA′ secretion assays demonstrating protein translocation into the host cell cytoplasm. (A) SpvD, GtgA, GtgE, SteD, SteE, and CigR are novel type III effector proteins. To determine if an effector was translocated by SPI-2 or both the SPI-1 and SPI-2 TTSS, bacteria expressing adenylate cyclase (CyaA′) fused to the indicated proteins were induced for SPI-1 or SPI-2 gene expression. Following infection of J774 cells, cAMP levels were measured. CyaA′ fusions were tested in the WT (black bars), SPI-1 mutant (invA::cat) (light-gray bars), and SPI-2 mutant (ssaK::cat) (open bars) backgrounds. Left, SPI-1 infection conditions; right, SPI-2 infection conditions. (B) SssA and SssB are secreted into J774 macrophages independently of TTS. In addition to in the WT, invA::cat, and ssaK::cat backgrounds, SssA and SssB::CyaA′ fusions were tested in an SPI-1, SPI-2 double mutant (ΔinvA ssaK::cat) (striped bars) and an SPI-1, SPI-2, flagellum triple mutant (ΔinvA ssaK::cat ΔflgB) (dark-gray bars). cAMP levels and error bars were obtained from three independent experiments but were not normalized to an internal control.

Effects of time and SsrB overexpression on secreted protein identifications.

When the secretome was analyzed as a whole, time point and SsrB-related abundance patterns of secretion varied among the wild-type, ssaL mutant, and ssaK mutant backgrounds. Most proteins had greater abundances at 8 h than at 4 h (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). A minority of proteins further increased in abundance by 16 h. Among the known SPI-2 effectors, there was a trend of increased secretion with time in the samples lacking arabinose. With SsrB overexpression from the pBADssrB plasmid, secretion of known effectors increased from 4 to 8 h, followed by a decline at 16 h (Fig. S3). Optimal effector identification correlated with stationary-phase growth in mLPM (Fig. S4), but the distinct secretion profiles at 8 and 16 h (Fig. S3) argue for additional, uncharacterized developments between time points.

Most type III effectors were detected in culture supernatants regardless of SsrB overexpression. However, there were several exceptions. SteB and SseK2 were exclusively identified in the samples lacking arabinose (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Conversely, the novel effectors CigR and SssB were restricted to the samples where SsrB was overexpressed (Table S3). Thus, SsrB overexpression had a modest impact upon effector identification, but it nevertheless permitted discovery of two additional secreted proteins.

Chromosomal location and virulence phenotypes of novel secreted proteins.

Most of the novel effector proteins are encoded within pathogenicity islands such as Gifsy-2 (gtgA and gtgE), Gifsy-3 (steE), and SPI-3 (cigR) or the Salmonella virulence plasmid (spvD), suggesting that they were horizontally acquired. On the other hand, steD, sssA, and sssB do not appear to be located in a pathogenicity island. Since SssA and SssB were secreted independently of TTS (Fig. 6), these proteins could belong to a more ancient secretion mechanism than the type III mechanism. SssA is unique in that it is only 33 amino acids in length and is the smallest effector reported to date. SssA has no enzymatic activity likely because of its small size, has no primary sequence homology, and is unstructured, based on nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis (G. Buchko, unpublished result). Conversely, SssB possesses a domain of unknown function (DUF1471) that is conserved among numerous members of the Enterobacteriaceae. We theorize that these two proteins may be secreted by an alternative, evolutionarily conserved system(s).

We next assessed the virulence properties of our novel secreted proteins. SpvD is encoded by most pathogenic Salmonella strains but is not required for virulence in BALB/c mice (6, 41). Conversely, a gtgE mutant was attenuated 7-fold for spleen colonization of i.p. infected BALB/c mice (28). Virulence phenotypes have not been reported for the other six novel secreted proteins. We constructed nonpolar deletions of each novel candidate effector except gtgA via lambda red-mediated allelic replacement and performed a competitive-index experiment with 129/SvJ mice infected i.p. These inbred mice express natural-resistance-associated macrophage protein 1 (Nramp 1), a myeloid-cell-specific transporter of divalent cations that affects susceptibility to Salmonella and other intracellular pathogens. In contrast to BALB/c mice, which are acutely sensitive to Salmonella infection, 129/SvJ mice present a persistent infection that can last for weeks (11, 45). Deletion of spvD, steE, gtgE, steD, and sssA significantly attenuated colonization of mouse spleens on days 1, 4, and 7 postinfection. The sssB mutant was attenuated on day 1 but appeared to recover by day 4 (Table 2). Our data agree with the previously reported virulence phenotype for GtgE but not for SpvD. The disparity may be attributable to the different mouse strains used in each study.

TABLE 2.

Competitive indexes derived from the spleens of i.p. infected 129/SvJ mice

| TTSS | Mutant genotype | Relative quantity on: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 4 | Day 7 | ||

| SPI-1/SPI-2 | ΔspvD | 0.50 ± 0.31a | 0.43 ± 0.07a | 0.28 ± 0.05a |

| ΔgtgE | 0.22 ± 0.05a | 0.25 ± 0.07a | 0.18 ± 0.04a | |

| ΔsteE | 0.46 ± 0.03a | 0.27 ± 0.09a | 0.14 ± 0.03a | |

| SPI-2 | ΔsteD | 0.22 ± 0.07a | 0.32 ± 0.07a | 0.21 ± 0.06a |

| ΔcigR | 0.68 ± 0.26 | 0.96 ± 0.17 | 1.04 ± 0.39 | |

| NAb | ΔsssA | 0.52 ± 0.10a | 0.66 ± 0.16a | 0.50 ± 0.08a |

| ΔsssB | 0.35 ± 0.04a | 0.91 ± 0.14 | 1.02 ± 0.35 | |

P < 0.05.

NA, not applicable.

DISCUSSION

We used mass spectrometry to investigate the secretomes of S. Typhimurium ATCC 14028, ΔssaL mutant, and ssaK mutant bacteria grown under SPI-2-inducing conditions. An ssaL mutant secreted 17 known SPI-2 type III effectors into medium but not the translocon proteins SseBCD. Coupling our proteomic data with the SIEVE algorithm proved to be an efficient way to select novel proteins for characterization. We report eight novel effectors that are translocated into host macrophages, six of which are required for full virulence in the spleens of i.p. infected 129/SvJ mice.

Additional phenotypes have been reported for an ssaL mutant of S. Typhimurium SL1344 (8, 10). Coombes and coworkers observed that SsaL was required for in vitro secretion of effectors encoded within SPI-2 (SseG and SseL) but was dispensable for secretion of effectors encoded outside SPI-2 (PipB and SopD2) (8). In contrast, we detected all four of these proteins secreted into ΔssaL culture supernatants (Fig. 4). Indeed, our data support a more general mechanism where SsaL inhibits SPI-2 effector secretion at acidic pH (68). Our data also suggest that Salmonella SsaL is a functional ortholog of SepL. SepL is found in enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), and Citrobacter rodentium. When sepL was mutated in these bacteria, they all secreted type III effector proteins into culture media and, thus, have been similarly exploited for proteomic analysis (15, 33, 60).

Both SepL and SsaL contain an HrpJ-like domain. HrpJ is a component of the TTSS from the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae and is required for its virulence (27). Since HrpJ-like domains are also present in the SPI-1 protein InvE and in type III apparatus proteins from Vibrio, Yersinia, and Shigella spp., deletion of these HrpJ-like genes may permit secretion into media. Therefore, proteomic approaches similar to ours may be extendable to numerous Gram-negative pathogens.

The secretome data suggest that Salmonella secretes numerous effector proteins into host cells independently of TTS. SssA and SssB fell into this category, and the secretion mechanism is under investigation in our laboratory. Of particular interest to us is secretion via OMV. We likely copurified OMV because we identified known Salmonella OMV cargo (OmpA, OmpC, OmpF, OmpX, and Pal) (13, 62), as well as cytoplasmic, periplasmic, and outer membrane proteins consistent with OMV content (13, 38). We also used filtered culture supernatants, which are the starting material for OMV purification strategies (13, 29, 62). Furthermore, our proteomic analysis identified SrfN, PagC, PagD, and PagK, which are secreted into host cells via OMV and are required for virulence in mice (Yoon et al., submitted). Since other virulence factors are likely to be translocated into cells by OMV, this presents an unexplored aspect of Salmonella pathogenesis for study.

In conclusion, we took advantage of an ssaL mutant and high-resolution LC-MS/MS to identify proteins secreted by S. Typhimurium in vitro. This has been the most comprehensive screen for Salmonella-secreted effectors to date. Most importantly, this study uncovered novel secreted effectors and implies the existence of novel secretory pathways for Salmonella virulence factors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jennifer Niemann, Karl Weitz, Therese Clauss, Angela Norbeck, Meagan Burnet, and Penny Colton for contributions to this work.

Support for this work was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH/DHHS, through interagency agreement Y1-A1-8401-01 and by grant NIH/NIAID A1022933-22A1 to F.H. We used instrumentation and capabilities developed with support from the National Center for Research Resources (grant RR 018522 to R.D.S.) and the DOE/BER.

Proteomic analyses were performed in the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Biological and Environmental Research (DOE/BER) national scientific user facility on the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) campus in Richland, WA. PNNL is a multiprogram national laboratory operated by Battelle for the DOE under contract DE-AC05-76RL01830. Mass spectrometry results are available at SysBEP.org and Omics.pnl.gov.

Editor: A. J. Bäumler

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 October 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adkins, J. N., H. M. Mottaz, A. D. Norbeck, J. K. Gustin, J. Rue, T. R. Clauss, S. O. Purvine, K. D. Rodland, F. Heffron, and R. D. Smith. 2006. Analysis of the Salmonella typhimurium proteome through environmental response toward infectious conditions. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5:1450-1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adkins, J. N., S. M. Varnum, K. J. Auberry, R. J. Moore, N. H. Angell, R. D. Smith, D. L. Springer, and J. G. Pounds. 2002. Toward a human blood serum proteome: analysis by multidimensional separation coupled with mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1:947-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ansong, C., H. Yoon, A. D. Norbeck, J. K. Gustin, J. E. McDermott, H. M. Mottaz, J. Rue, J. N. Adkins, F. Heffron, and R. D. Smith. 2008. Proteomics analysis of the causative agent of typhoid fever. J. Proteome Res. 7:546-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansong, C., H. Yoon, S. Porwollik, H. Mottaz-Brewer, B. O. Petritis, N. Jaitly, J. N. Adkins, M. McClelland, F. Heffron, and R. D. Smith. 2009. Global systems-level analysis of Hfq and SmpB deletion mutants in Salmonella: implications for virulence and global protein translation. PLoS One 4:e4809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakowski, M. A., V. Braun, and J. H. Brumell. 2008. Salmonella-containing vacuoles: directing traffic and nesting to grow. Traffic 9:2022-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauerfeind, R., S. Barth, R. Weiss, and G. Baljer. 2001. Prevalence of the Salmonella plasmid virulence gene “spvD” in Salmonella strains from animals. Dtsch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 108:243-245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belden, W. J., and S. I. Miller. 1994. Further characterization of the PhoP regulon: identification of new PhoP-activated virulence loci. Infect. Immun. 62:5095-5101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coombes, B., N. Brown, Y. Valdez, J. Brumell, and B. Finlay. 2004. Expression and secretion of Salmonella pathogenicity island-2 virulence genes in response to acidification exhibit differential requirements of a functional type III secretion apparatus and SsaL. J. Biol. Chem. 279:49804-49815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coombes, B., M. Wickham, N. Brown, S. Lemire, L. Bossi, W. Hsiao, F. Brinkman, and B. Finlay. 2005. Genetic and molecular analysis of GogB, a phage-encoded type III-secreted substrate in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium with autonomous expression from its associated phage. J. Mol. Biol. 348:817-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coombes, B. K., M. J. Lowden, J. L. Bishop, M. E. Wickham, N. F. Brown, N. Duong, S. Osborne, O. Gal-Mor, and B. B. Finlay. 2007. SseL is a Salmonella-specific translocated effector integrated into the SsrB-controlled Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 type III secretion system. Infect. Immun. 75:574-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuellar-Mata, P., N. Jabado, J. Liu, W. Furuya, B. B. Finlay, P. Gros, and S. Grinstein. 2002. Nramp1 modifies the fusion of Salmonella typhimurium-containing vacuoles with cellular endomembranes in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 277:2258-2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Datsenko, K., and B. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deatherage, B. L., J. C. Lara, T. Bergsbaken, S. L. Rassoulian Barrett, S. Lara, and B. T. Cookson. 2009. Biogenesis of bacterial membrane vesicles. Mol. Microbiol. 72:1395-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deiwick, J., T. Nikolaus, S. Erdogan, and M. Hensel. 1999. Environmental regulation of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1759-1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng, W., J. Puente, S. Gruenheid, Y. Li, B. Vallance, A. Vazquez, J. Barba, J. Ibarra, P. O'Donnell, P. Metalnikov, K. Ashman, S. Lee, D. Goode, T. Pawson, and B. Finlay. 2004. Dissecting virulence: systematic and functional analyses of a pathogenicity island. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:3597-3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eng, J. K., A. L. McCormack, and J. R. Yates III. 1994. An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 5:976-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geddes, K., F. Cruz, and F. Heffron. 2007. Analysis of cells targeted by Salmonella type III secretion in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 3:e196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geddes, K., M. Worley, G. Niemann, and F. Heffron. 2005. Identification of new secreted effectors in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 73:6260-6271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ginocchio, C. C., S. B. Olmsted, C. L. Wells, and J. E. Galan. 1994. Contact with epithelial cells induces the formation of surface appendages on Salmonella typhimurium. Cell 76:717-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong, H., G. Vu, Y. Bai, E. Yang, F. Liu, and S. Lu. 2010. Differential expression of Salmonella type III secretion system factors InvJ, PrgJ, SipC, SipD, SopA, and SopB in cultures and in mice. Microbiology. 156(Pt. 1):116-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham, S. 2002. Salmonellosis in children in developing and developed countries and populations. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 15:507-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guerrant, R. L., J. M. Hughes, N. L. Lima, and J. Crane. 1990. Diarrhea in developed and developing countries: magnitude, special settings, and etiologies. Rev. Infect. Dis. 12(Suppl. 1):S41-S50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gunn, J. S., C. M. Alpuche-Aranda, W. P. Loomis, W. J. Belden, and S. I. Miller. 1995. Characterization of the Salmonella typhimurium pagC/pagD chromosomal region. J. Bacteriol. 177:5040-5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen-Wester, I., and M. Hensel. 2001. Salmonella pathogenicity islands encoding type III secretion systems. Microbes Infect. 3:549-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haraga, A., M. B. Ohlson, and S. I. Miller. 2008. Salmonellae interplay with host cells. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:53-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hendrickson, E. L., Q. Xia, T. Wang, J. A. Leigh, and M. Hackett. 2006. Comparison of spectral counting and metabolic stable isotope labeling for use with quantitative microbial proteomics. Analyst 131:1335-1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirano, S. S., A. O. Charkowski, A. Collmer, D. K. Willis, and C. D. Upper. 1999. Role of the Hrp type III protein secretion system in growth of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a on host plants in the field. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:9851-9856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ho, T. D., N. Figueroa-Bossi, M. Wang, S. Uzzau, L. Bossi, and J. M. Slauch. 2002. Identification of GtgE, a novel virulence factor encoded on the Gifsy-2 bacteriophage of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 184:5234-5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kadurugamuwa, J. L., and T. J. Beveridge. 1995. Virulence factors are released from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in association with membrane vesicles during normal growth and exposure to gentamicin: a novel mechanism of enzyme secretion. J. Bacteriol. 177:3998-4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keller, A., A. I. Nesvizhskii, E. Kolker, and R. Aebersold. 2002. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal. Chem. 74:5383-5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kenny, B., R. DeVinney, M. Stein, D. J. Reinscheid, E. A. Frey, and B. B. Finlay. 1997. Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) transfers its receptor for intimate adherence into mammalian cells. Cell 91:511-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Komoriya, K., N. Shibano, T. Higano, N. Azuma, S. Yamaguchi, and S. I. Aizawa. 1999. Flagellar proteins and type III-exported virulence factors are the predominant proteins secreted into the culture media of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 34:767-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kresse, A. U., F. Beltrametti, A. Muller, F. Ebel, and C. A. Guzman. 2000. Characterization of SepL of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:6490-6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lapaque, N., J. L. Hutchinson, D. C. Jones, S. Meresse, D. W. Holden, J. Trowsdale, and A. P. Kelly. 2009. Salmonella regulates polyubiquitination and surface expression of MHC class II antigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:14052-14057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawley, T. D., K. Chan, L. J. Thompson, C. C. Kim, G. R. Govoni, and D. M. Monack. 2006. Genome-wide screen for Salmonella genes required for long-term systemic infection of the mouse. PLoS Pathog. 2:e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee, A. K., C. S. Detweiler, and S. Falkow. 2000. OmpR regulates the two-component system SsrA-SsrB in Salmonella pathogenicity island 2. J. Bacteriol. 182:771-781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reference deleted.

- 38.Lee, E. Y., J. Y. Bang, G. W. Park, D. S. Choi, J. S. Kang, H. J. Kim, K. S. Park, J. O. Lee, Y. K. Kim, K. H. Kwon, K. P. Kim, and Y. S. Gho. 2007. Global proteomic profiling of native outer membrane vesicles derived from Escherichia coli. Proteomics 7:3143-3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lejona, S., M. E. Castelli, M. L. Cabeza, L. J. Kenney, E. Garcia Vescovi, and F. C. Soncini. 2004. PhoP can activate its target genes in a PhoQ-independent manner. J. Bacteriol. 186:2476-2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu, H., R. G. Sadygov, and J. R. Yates III. 2004. A model for random sampling and estimation of relative protein abundance in shotgun proteomics. Anal. Chem. 76:4193-4201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsui, H., C. M. Bacot, W. A. Garlington, T. J. Doyle, S. Roberts, and P. A. Gulig. 2001. Virulence plasmid-borne spvB and spvC genes can replace the 90-kilobase plasmid in conferring virulence to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in subcutaneously inoculated mice. J. Bacteriol. 183:4652-4658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGhie, E. J., L. C. Brawn, P. J. Hume, D. Humphreys, and V. Koronakis. 2009. Salmonella takes control: effector-driven manipulation of the host. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:117-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mermin, J., R. Villar, J. Carpenter, L. Roberts, A. Samaridden, L. Gasanova, S. Lomakina, C. Bopp, L. Hutwagner, P. Mead, B. Ross, and E. Mintz. 1999. A massive epidemic of multidrug-resistant typhoid fever in Tajikistan associated with consumption of municipal water. J. Infect. Dis. 179:1416-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miao, E. A., J. A. Freeman, and S. I. Miller. 2002. Transcription of the SsrAB regulon is repressed by alkaline pH and is independent of PhoPQ and magnesium concentration. J. Bacteriol. 184:1493-1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monack, D. M., D. M. Bouley, and S. Falkow. 2004. Salmonella typhimurium persists within macrophages in the mesenteric lymph nodes of chronically infected Nramp1+/+ mice and can be reactivated by IFNgamma neutralization. J. Exp. Med. 199:231-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nishio, M., N. Okada, T. Miki, T. Haneda, and H. Danbara. 2005. Identification of the outer-membrane protein PagC required for the serum resistance phenotype in Salmonella enterica serovar Choleraesuis. Microbiology 151:863-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osborne, S. E., D. Walthers, A. M. Tomljenovic, D. T. Mulder, U. Silphaduang, N. Duong, M. J. Lowden, M. E. Wickham, R. F. Waller, L. J. Kenney, and B. K. Coombes. 2009. Pathogenic adaptation of intracellular bacteria by rewiring a cis-regulatory input function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:3982-3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peng, J., J. E. Elias, C. C. Thoreen, L. J. Licklider, and S. P. Gygi. 2003. Evaluation of multidimensional chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC/LC-MS/MS) for large-scale protein analysis: the yeast proteome. J. Proteome Res. 2:43-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Polpitiya, A. D., W. J. Qian, N. Jaitly, V. A. Petyuk, J. N. Adkins, D. G. Camp II, G. A. Anderson, and R. D. Smith. 2008. DAnTE: a statistical tool for quantitative analysis of -omics data. Bioinformatics 24:1556-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samudrala, R., F. Heffron, and J. E. McDermott. 2009. Accurate prediction of secreted substrates and identification of a conserved putative secretion signal for type III secretion systems. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shea, J. E., M. Hensel, C. Gleeson, and D. W. Holden. 1996. Identification of a virulence locus encoding a second type III secretion system in Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:2593-2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shen, Y., N. Tolic, R. Zhao, L. Pasa-Tolic, L. Li, S. J. Berger, R. Harkewicz, G. A. Anderson, M. E. Belov, and R. D. Smith. 2001. High-throughput proteomics using high-efficiency multiple-capillary liquid chromatography with on-line high-performance ESI FTICR mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 73:3011-3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reference deleted.

- 54.Smith, R. D., G. A. Anderson, M. S. Lipton, C. Masselon, L. Pasa-Tolic, Y. Shen, and H. R. Udseth. 2002. The use of accurate mass tags for high-throughput microbial proteomics. OMICS 6:61-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith, R. D., G. A. Anderson, M. S. Lipton, L. Pasa-Tolic, Y. Shen, T. P. Conrads, T. D. Veenstra, and H. R. Udseth. 2002. An accurate mass tag strategy for quantitative and high-throughput proteome measurements. Proteomics 2:513-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sory, M. P., A. Boland, I. Lambermont, and G. R. Cornelis. 1995. Identification of the YopE and YopH domains required for secretion and internalization into the cytosol of macrophages, using the cyaA gene fusion approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:11998-12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Srinivasan, A., M. Nanton, A. Griffin, and S. J. McSorley. 2009. Culling of activated CD4 T cells during typhoid is driven by Salmonella virulence genes. J. Immunol. 182:7838-7845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steele-Mortimer, O. 2008. The Salmonella-containing vacuole: moving with the times. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11:38-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas, M., and D. W. Holden. 2009. Ubiquitination—a bacterial effector's ticket to ride. Cell Host Microbe 5:309-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tobe, T., S. A. Beatson, H. Taniguchi, H. Abe, C. M. Bailey, A. Fivian, R. Younis, S. Matthews, O. Marches, G. Frankel, T. Hayashi, and M. J. Pallen. 2006. An extensive repertoire of type III secretion effectors in Escherichia coli O157 and the role of lambdoid phages in their dissemination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:14941-14946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reference deleted.

- 62.Wai, S., B. Lindmark, T. Soderblom, A. Takade, M. Westermark, J. Oscarsson, J. Jass, A. Richter-Dahlfors, Y. Mizunoe, and B. Uhlin. 2003. Vesicle-mediated export and assembly of pore-forming oligomers of the enterobacterial ClyA cytotoxin. Cell 115:25-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang, D., A. Roe, S. McAteer, M. Shipston, and D. Gally. 2008. Hierarchal type III secretion of translocators and effectors from Escherichia coli O157:H7 requires the carboxy terminus of SepL that binds to Tir. Mol. Microbiol. 69:1499-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Washburn, M. P., D. Wolters, and J. R. Yates III. 2001. Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat. Biotechnol. 19:242-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Worley, M. J., K. H. Ching, and F. Heffron. 2000. Salmonella SsrB activates a global regulon of horizontally acquired genes. Mol. Microbiol. 36:749-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu, N. Y., J. R. Wagner, M. R. Laird, G. Melli, S. Rey, R. Lo, P. Dao, S. C. Sahinalp, M. Ester, L. J. Foster, and F. S. Brinkman. 2010. PSORTb 3.0: improved protein subcellular localization prediction with refined localization subcategories and predictive capabilities for all prokaryotes. Bioinformatics 26:1608-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reference deleted.

- 68.Yu, X. J., K. McGourty, M. Liu, K. E. Unsworth, and D. W. Holden. 2010. pH sensing by intracellular Salmonella induces effector translocation. Science 328:1040-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zimmer, J. S., M. E. Monroe, W. J. Qian, and R. D. Smith. 2006. Advances in proteomics data analysis and display using an accurate mass and time tag approach. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 25:450-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.