Abstract

Meningitis is the most serious of invasive infections caused by the Gram-positive bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae. Vaccines protect only against a limited number of serotypes, and evolving bacterial resistance to antimicrobials impedes treatment. Further insight into the molecular pathogenesis of invasive pneumococcal disease is required in order to enable the development of new or adjunctive treatments and/or pneumococcal vaccines that are efficient across serotypes. We applied genomic array footprinting (GAF) in the search for S. pneumoniae genes that are essential during experimental meningitis. A total of 6,000 independent TIGR4 marinerT7 transposon mutants distributed over four libraries were injected intracisternally into rabbits, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected after 3, 9, and 15 h. Microarray analysis of mutant-specific probes from CSF samples and inocula identified 82 and 11 genes mutants of which had become attenuated or enriched, respectively, during infection. The results point to essential roles for capsular polysaccharides, nutrient uptake, and amino acid biosynthesis in bacterial replication during experimental meningitis. The GAF phenotype of a subset of identified targets was followed up by detailed studies of directed mutants in competitive and noncompetitive infection models of experimental rat meningitis. It appeared that adenylosuccinate synthetase, flavodoxin, and LivJ, the substrate binding protein of a branched-chain amino acid ABC transporter, are relevant as targets for future therapy and prevention of pneumococcal meningitis, since their mutants were attenuated in both models of infection as well as in competitive growth in human cerebrospinal fluid in vitro.

Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis remains a serious infectious disease causing death in approximately 25% of cases and neurological sequelae in half of survivors in spite of antibiotic treatment and intensive caretaking (29, 39). To cause meningitis, the pneumococcus disseminates to the meninges via the bloodstream from a distant focus of infection (e.g., pneumonia) or directly from a primary infectious focus in the upper respiratory tract (e.g., otitis media or sinusitis). Capsular polysaccharide (cps)-based vaccines are protective against pneumococcal infection caused by the serotypes included and have been introduced in many national health protection programs (11, 33). Because it is not possible to cover all of the >90 different pneumococcal serotypes in a single vaccine, current cps-based vaccines have been designed to target the serotypes most often involved in invasive infection. Since the introduction of these vaccines, serotype replacement has led to the emergence of novel invasive nonvaccine strains (13, 18). This phenomenon has stimulated the search for noncapsular pneumococcal vaccine leads and therapeutic targets common to all serotypes in an effort to prevent future disease and morbidity.

A detailed understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of S. pneumoniae colonization and disease is indispensable for the design of effective novel broad-range vaccines. Gene expression and knockout studies have been applied in the search for essential pneumococcal genes in different models of experimental infection (21, 26, 27). However, in most studies, the number of genes under investigation remained limited, and their selection was often based on prior knowledge. To identify novel targets for vaccine and drug design, unbiased genome-wide approaches are needed. With the availability of microarrays, the possibilities for genome-wide identification of pneumococcal genes contributing to pathogenesis have greatly expanded. Orihuela and coworkers (28) compared the S. pneumoniae gene expression profiles in experimental bacteremia, experimental meningitis, and an in vitro pharyngeal carriage model, thereby adding significantly to the knowledge of pneumococcal physiology in carriage and invasive disease. However, expression analysis does not reveal essential genes that are not differentially expressed, and increased expression of a gene does not always translate into essentiality of the gene.

The development of signature-tagged mutagenesis (STM) (16) has improved and accelerated the identification of essential bacterial genes in infection. In STM, pools of insertional mutants are created, and each mutant is labeled with a unique DNA tag to enable its identification. After the exposure of bacterial mutant pools to the condition of interest, the presence of individual mutants before and after growth is determined by detection of mutant-specific DNA tags. STM mutant library screens have now provided knowledge about S. pneumoniae genes that are essential in otitis media, colonization, pneumonia, and bacteremia (7, 14, 20, 31). At present, no such screen has been performed on the genes required in meningitis.

In the present study, we describe a mutant library screen in the search for S. pneumoniae genes essential for bacterial replication during experimental meningitis in rabbits. Instead of STM, we applied the novel microarray-based genomic array footprinting (GAF) technology that has recently been developed for S. pneumoniae (2, 6). GAF obviates the need for multiple rounds of mutagenesis to incorporate unique STM DNA tags and instead uses microarrays to generate footprints of a single marinerT7 transposon mutant library. The roles of individual genes identified by GAF were validated in single-infection and coinfection models of experimental rat meningitis and in competitive in vitro growth in human cerebrospinal fluid (h-CSF).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Wild-type and mutant S. pneumoniae TIGR4 strains were routinely grown in GM17 broth (M17 broth containing 0.25% [wt/vol] glucose) or on blood agar (BA) plates composed of Columbia agar (Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom) supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood (Biotrading, Mijdrecht, Netherlands) or horse blood (SVA, Bro, Sweden). All cultures were incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. S. pneumoniae freezer stocks for infection and growth experiments were prepared from mid-log-phase cultures in GM17 broth or sterile filtered beef broth (Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark) and were stored with 15% glycerol at −80°C. Bacterial CFU in freezer stocks, inocula, and samples were determined by plating 10-fold serial dilutions in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) on BA plates. S. pneumoniae mutant libraries and directed mutants were selected with 150 μg ml−1 spectinomycin.

Generation of S. pneumoniae transposon mutant libraries.

S. pneumoniae TIGR4 marinerT7 transposon mutant libraries were generated essentially as described previously (2). Briefly, 1 μg of pneumococcal genomic DNA was incubated in the presence of purified HimarC9 transposase and 0.5 μg of plasmid pR412T7 as a donor of the marinerT7 transposon conferring spectinomycin resistance. After repair of the resulting transposition products with Escherichia coli DNA ligase and T4 DNA polymerase, 100 ng mutagenized DNA was used for transformation of 1 ml competent S. pneumoniae cells. For mutant libraries, the required number of colonies was scraped from the plates, pooled, grown to mid-log phase in GM17 medium supplemented with spectinomycin, and stored in 15% glycerol at −80°C.

GAF mutant selection in an experimental rabbit meningitis model.

The rabbit meningitis model was set up as described previously (30). Briefly, 106 CFU of an S. pneumoniae mutant library was suspended in 20 μl beef broth and injected into the cisternae magnae of four groups of four outbred New Zealand White rabbits weighing approximately 2.5 kg (in one group, one rabbit died). CSF (0.3 ml) and blood (1 ml) were sampled from the rabbits by aspiration from indwelling spinal and arterial cannulae, yielding four replicates (in one case only three) at three time points for each screened mutant library. White blood cells (WBC) in CSF and blood samples were analyzed on a veterinary cell counter (Medonic CA-620), and a corrected CSF WBC count was calculated, taking into account possible blood contamination during sampling. Until further processing in the GAF protocol, separate CSF samples and inocula were stored with 15% glycerol at −80°C.

Genomic array footprinting.

The GAF technology was used as described previously (2). Briefly, the stored inocula of the S. pneumoniae mutant libraries in beef broth and the CSF samples from the rabbit meningitis experiments were defrosted, diluted in GM17 medium supplemented with spectinomycin, and grown to mid-log phase. Chromosomal DNA from S. pneumoniae mutant libraries was isolated and digested with AluI endonuclease. In vitro transcription, initiated from the T7 promoters on the marinerT7 transposon that is present in each mutant, resulted in mutant-specific T7 mRNA that marks the insertion site of the transposon in the S. pneumoniae genome. After the removal of template DNA by DNase I treatment, the T7 RNA was reverse transcribed in the presence of fluorescent Cy3/Cy5-labeled dUTP nucleotides to generate mutant-specific cDNA. Cy3/Cy5-labeled cDNA from the CSF samples and oppositely labeled (Cy5/Cy3) cDNA from the individual inocula were combined, purified, and washed by ultrafiltration. The mutant-specific fluorescent cDNA was hybridized to pneumococcal microarrays containing 2,087 open reading frames (ORFs) of S. pneumoniae TIGR4 and 70-mer oligonucleotides specific for the nonhomologous ORFs in strains R6, D39, 23F, INV104B, INV200, OXC141, and G54, all spotted in duplicate (15). Dual-channel array images were acquired on a GenePix 4200AL microarray scanner (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). A total of 45 microarrays, corresponding to the number of CSF samples, were analyzed.

Microarray data analysis.

Microarray image files were analyzed with GenePix Pro software (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). Spots were screened visually to identify those of low quality, which were removed from the data set prior to analysis. A net mean intensity filter based on hybridization signals obtained with R6-specific spots was applied in all experiments. Slide data were processed and normalized using MicroPreP (38). Further analysis was performed using a Cyber-T implementation of Student's t test (cybert.microarray.ics.uci.edu). This Web-based program lists the ratios of all intrareplicates (duplicate spots) and interreplicates (different slides), the mean ratios per gene, and standard deviations and (Bayesian) P values assigned to the mean ratios. For the identification of conditionally essential genes, only genes with a minimum of 6/8 (for groups of four rabbits) or 5/6 (for the group of three rabbits) reliable measurements and a Bayesian P value of <0.001 were included. Further selection criteria were applied: only mutants displaying an average fold change of >2.5 at a minimum of two time points, or >4.0 at one time point, were accepted as significantly attenuated or enriched.

In silico analysis.

Functional annotations of all genes were derived from the TIGR Comprehensive Microbial Resource database (http://cmr.jcvi.org/tigr-scripts/CMR/CmrHomePage.cgi). Additional information on the (putative) function of a gene was derived by using the orthology option in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (www.kegg.com). The subcellular localization of proteins encoded by genes identified in GAF screens was computationally predicted using several prediction servers, such as SignalP 3.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP), PSORTb (http://www.psort.org), and TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM).

Generation of S. pneumoniae directed mutants for validation experiments.

Directed deletion mutants of S. pneumoniae TIGR4 were generated by allelic exchange of the target gene with an antibiotic resistance marker as described previously (6). Briefly, overlap extension PCR was applied to insert the spectinomycin resistance cassette of the pR412 plasmid between the two 500-bp flanking sequences surrounding the target gene. The overlap extension PCR products were transformed into S. pneumoniae, and directed mutants were obtained by selective plating. Correct integration of the antibiotic resistance cassette into the target gene was validated by PCR. Gene deletions were crossed back to the wild-type strain by using chromosomal DNA of the mutant strains as the donor during transformation. The primers (Biolegio, Nijmegen, Netherlands) used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Experimental rat meningitis models.

Experimental rat meningitis experiments were performed as described elsewhere (3). For competitive infection experiments, 30-μl inocula containing a 1:1 ratio of the mutant to the wild type (105 CFU total) were used for intracisternal inoculation to induce experimental meningitis in groups of four outbred Wistar rats weighing approximately 160 g. CSF was sampled at 72 h postinfection by cisternal puncture to determine viable bacterial counts of the S. pneumoniae mutant and wild-type strains and to enumerate WBC. The lower detection limit for bacteria in CSF samples was 250 CFU ml−1 (when no colonies were recovered, 249 CFU ml−1 was used as the count). A competitive index (CI) score, expressing the relative growth defect of the mutant compared to the wild type, was calculated by dividing the output ratio of the CFU counts of mutant to wild-type bacteria by the input ratio of mutant to wild-type bacteria for every CSF sample.

In noncompetitive infection experiments, groups of five outbred Wistar rats weighing approximately 160 g were intracisternally infected with 105 CFU (in a volume of 30 μl beef broth) of either a mutant strain or the wild-type strain. CSF was sampled by cisternal puncture after 24 and 72 h to determine viable bacterial counts. The lower detection limits for bacteria in the CSF samples were in the range of 25 to 250 CFU ml−1, due to differences in the amounts of spinal fluid sampled. Rats were evaluated clinically every day. They were assigned a disease severity score, obtained by adding up three ratings of zero to 4 (normal animals were assigned a score of zero) for their level of activity and the appearance of their ocular surroundings and fur (4).

Competitive in vitro growth in h-CSF.

Freezer stocks of wild-type and mutant S. pneumoniae strains grown to mid-log phase in GM17 medium were defrosted, pelleted, washed in PBS, and resuspended in PBS to 107 CFU ml−1. Suspensions of wild-type and mutant strains were combined 1:1, diluted 20-fold in 10 μl GM17 broth or h-CSF, and grown for 4 h at 37°C in an oxygen-deprived environment (GENbag anaer; bioMérieux). CI scores were calculated as in the coinfection experiment (see “Experimental rat meningitis models” above). CSF had been collected from patients for diagnostic reasons and was accepted for the growth experiment only in cases where no neurological disorder was diagnosed and only when routine parameters of the CSF (WBC, red blood cells [RBC], protein, glucose, and lactate) were within the normal range. CSF was transported to the laboratory within 2 h after the lumbar puncture, centrifuged, and stored at −80°C until use in this study.

Ethics.

All meningitis experiments were conducted at the laboratory animal facilities at Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark. All protocols were approved by the Danish Animal Experiment Inspectorate “Dyreforsøgstilsynet.”

Statistics.

In competition experiments, a one-sample t test on log-transformed CI scores (with an arbitrary mean of zero and a P value of <0.05) was used to calculate statistical significance. In noncompetitive experiments, two-way repeated-measurement analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni posttests were used to evaluate the significance of differences in log bacterial CFU and disease severity scores between rats infected with the wild type and those infected with individual mutants. The results were accepted as significant at a P value of <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Microarray data accession number.

The microarray data have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under GEO Series record GSE21729.

RESULTS

Genome-wide GAF meningitis screen.

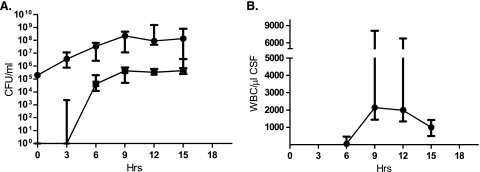

A genome-wide GAF screen in experimental meningitis in rabbits was performed with four S. pneumoniae TIGR4 marinerT7 transposon mutant libraries, covering a total of ca. 6,000 independent mutants. After the direct injection of bacterial inocula into the cisterna magna, CSF was extracted before pleocytosis developed (3 h), at the time of maximal pleocytosis (9 h), and at a time of slowing bacterial growth and abating pleocytosis (15 h). The sampling times for CSF and blood were chosen based on the results of a pilot rabbit meningitis experiment with S. pneumoniae TIGR4 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Progression of bacterial infection and the evolving immune response during experimental rabbit meningitis. Four outbred New Zealand White rabbits were infected with S. pneumoniae TIGR4, and CSF (0.3 ml) and blood (1 ml) were sampled by repeated aspiration from indwelling spinal and arterial cannulae. (A) Median concentrations of bacterial CFU in CSF (circles) and blood (squares). Error bars indicate ranges. (B) Median concentrations (and ranges) of WBC in CSF. Hrs, time postinfection.

GAF analysis yielded data on 1,813 genes in at least one mutant library at one time point. Mutants with mutations of a total of 93 genes (5%) met the GAF selection criteria for attenuated or enriched replication during experimental meningitis. We identified 82 genes that are essential for the replication of S. pneumoniae in rabbit spinal fluid in vivo (Table 1 ) and 11 genes whose disruption promotes in vivo growth in rabbit meningitis (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Targeted S. pneumoniae genes of mutants attenuated during experimental meningitis

| TIGR4 locus by role category | Gene name | Annotation | Negative fold changea at: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 h | 9 h | 15 h | |||

| Amino acid biosynthesis | |||||

| SP_0585 | metE | 5-Methyltetrahydropteroyltriglutamate-homocysteine methyltransferase | 1.4 | 3.8 | 4.5 |

| SP_0931 | proB | Glutamate 5-kinase | 2.2 | 8.0 | 8.3 |

| SP_1296 | Chorismate mutase, putative | 2.4 | 2.2 | 4.8 | |

| SP_1376 | aroE | Shikimate 5-dehydrogenase | 2.0 | 8.8 | 7.4 |

| SP_1544 | aspC | Aspartate aminotransferase | 2.3 | 4.2 | 2.8 |

| Biosynthesis of cofactors, prosthetic groups, and carriers | |||||

| SP_0197 | Dihydrofolate synthetase, putative | 10.9 | 20.8 | 16.2 | |

| SP_0881 | thiI | Thiazole biosynthesis protein ThiI | 1.5 | 3.2 | 2.7 |

| Cell envelope | |||||

| SP_0342 | dexB | Glucan 1,6-α-glucosidase | 2.3 | 4.5 | 5.8 |

| SP_0348 | cps4C | Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis protein | 2.2 | 3.0 | 2.8 |

| SP_0349 | cps4D | Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis protein | 2.0 | 3.7 | 2.7 |

| SP_0350 | cps4E | Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis protein | 3.9 | 46.3 | 33.8 |

| SP_0351 | cps4F | Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis protein | 3.9 | 10.5 | 13.7 |

| SP_0358 | cap4J | Capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis protein | 6.8 | 15.9 | 17.2 |

| SP_1966 | murA | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase | 1.1ns | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Cellular processes | |||||

| SP_0042 | comA | Competence factor-transporting ATP-binding/permease protein | 3.7 | 3.5 | 6.0 |

| SP_1462 | Arsenate reductase | 1.4 | 3.3 | 5.2 | |

| SP_1466 | Hemolysin | 9.5 | 6.5 | 7.0 | |

| SP_1645 | relA | GTP pyrophosphokinase | 10.2 | 14.6 | 16.5 |

| DNA metabolism, SP_1336 | spn5252IMP | Type II DNA modification methyltransferase Spn5252IP | 1.1ns | 4.6 | 7.1 |

| Energy metabolism | |||||

| SP_1068 | ppc | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | 7.1 | 1.8 | 9.9 |

| SP_1121 | glgB | 1,4-α-Glucan branching enzyme | 2.1 | 3.9 | 3.8 |

| SP_1297 | fld | Flavodoxin | 3.5 | 5.9 | 7.7 |

| SP_1330 | nanE | N-Acetylmannosamine-6-P epimerase, putative | 1.7 | 12.5 | 14.2 |

| SP_1507 | atpC | ATP synthase F1, epsilon subunit | 2.0 | 1.2 | 4.6 |

| SP_2021 | Glycosyl hydrolase, family 1 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 2.8 | |

| Fatty acid and phospholipid metabolism, SP_0199 | cls | Cardiolipin synthetase | 1.8 | 5.2 | 3.6 |

| Protein fate, SP_0746 | clpP | ATP-dependent Clp protease, proteolytic subunit | 1.2ns | 2.3 | 5.1 |

| Protein synthesis | |||||

| SP_1299 | rpmE | Ribosomal protein L31 | 2.8 | 10.0 | 9.2 |

| SP_2206 | yfiA | Ribosomal subunit interface protein | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| Purines, pyrimidines, nucleosides, and nucleotides | |||||

| SP_0019 | purA | Adenylosuccinate synthetase | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.6 |

| SP_0494 | pyrG | CTP synthase | 7.0 | 17.9 | 17.1 |

| Regulatory functions | |||||

| SP_0058 | Transcriptional regulator, GntR family | 2.4 | 4.1 | 3.6 | |

| SP_0416 | fabT | Transcriptional regulator, MarR family | 1.1ns | 3.3 | 4,1 |

| SP_1331 | Phosphosugar-binding transcriptional regulator, RpiR family, putative | 1.6 | 5.2 | 5.1 | |

| SP_1393 | Transcriptional regulator, GntR family, putative | 0.8 | 2.0 | 4.9 | |

| SP_1799 | susR | Sugar-binding transcriptional regulator, LacI family | 1.8 | 2.7 | 3.7 |

| Transport and binding | |||||

| SP_0079 | Potassium uptake protein, Trk family | NA | 3.7 | 4.4 | |

| SP_0101 | Putative MFSb transporter, permease; cyanate | 2.3 | 3.2 | 7.5 | |

| SP_0149 | ABC transporter, substrate binding protein; methionine | 1.8 | 3.3 | 5.2 | |

| SP_0151 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein; methionine | 1.9 | 3.4 | 4.6 | |

| SP_0152 | ABC transporter, permease protein, putative; methionine | 1.9 | 3.9 | 6.3 | |

| SP_0282 | PTS system, mannose-specific IID component | 1.3ns | 3.3 | 5.6 | |

| SP_0308 | PTS system, cellobiose-specific IIA component | 0.9ns | 2.6 | 3.4 | |

| SP_0749 | livJ | ABC transporter, amino acid-binding protein; branched-chain amino acid | 1.1ns | 4.1 | 8.8 |

| SP_0751 | livM | ABC transporter, permease protein; branched-chain amino acid | 1.2ns | 2.9 | 5.4 |

| SP_0752 | livG | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein; branched-chain amino acid | 1.2ns | 3.6 | 6.2 |

| SP_0753 | livF | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein; branched-chain amino acid | 1.6 | 2.8 | 3.7 |

| SP_0823 | ABC transporter, permease protein; polar amino acid | 2.0 | 2.5 | 6.9 | |

| SP_0826 | ABC-type transporter, ATP-binding protein; phosphate | 2.8 | 6.1 | 4.7 | |

| SP_1062 | ABC-2 transporter, ATP-binding protein; unknown substrate | 1.1ns | 3.8 | 6.3 | |

| SP_1063 | ABC-2 transporter, permease protein; unknown substrate | 1.2ns | 3.3 | 7.4 | |

| SP_1069 | Putative ABC transporter, substrate binding protein; unknown substrate | 1.7 | 4.7 | 0.5 | |

| SP_1502 | ABC transporter, permease protein; polar amino acid | 4.4 | 1.5 | 5.0 | |

| SP_2198 | ABC transporter, permease protein; sulfonate/nitrate/taurine | 2.0 | 3.6 | 3.1 | |

| SP_2231 | Putative ABC transporter, permease protein, putative; unknown substrate | 1.4 | 1.6 | 5.8 | |

| Unknown function | |||||

| SP_0665 | Chorismate binding enzyme | 3.8 | 7.2 | 6.8 | |

| SP_0695 | HesA/MoeB/ThiF family protein | 3.8 | 5.7 | 4.3 | |

| SP_1298 | DHH subfamily 1 protein | 3.6 | 8.9 | 6.3 | |

| SP_0731 | Putative glyoxalase family protein | 1.1ns | 4.2 | 1.1 | |

| SP_0925 | CAAX amino protease family | 3.1 | 12.2 | 11.4 | |

| SP_1356 | Atz/Trz family protein | NA | 2.6 | 3.0 | |

| SP_1563 | Pyridine nucleotide-disulfide oxidoreductase family protein | 3.9 | 5.0 | 5.0 | |

| SP_2116 | CAAX amino protease family | 1.4 | 4.5 | 0.3 | |

| SP_2205 | DHH subfamily 1 protein | NA | 2.5 | 2.5 | |

| Hypothetical | |||||

| SP_0029 | Hypothetical protein | 2.7 | 3.3 | 2.5 | |

| SP_0067 | Hypothetical protein | 0.8 | 2.5 | 2.6 | |

| SP_0098 | Hypothetical protein | 1.6 | 2.2 | 4.1 | |

| SP_0099 | Hypothetical protein | 1.8 | 3.1 | 6.5 | |

| SP_0198 | Hypothetical protein | 2.1 | 6.9 | 5.4 | |

| SP_0276 | Conserved hypothetical protein | NA | 7.9 | NA | |

| SP_0279 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.1 | 2.9 | 4.2 | |

| SP_0552 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.8 | 5.9 | 6.0 | |

| SP_0649 | Conserved hypothetical protein, degenerate | NA | 1.7 | 4.9 | |

| SP_0748 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 1.3ns | 3.9 | 8.8 | |

| SP_0822 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 1.7 | 2.7 | 7.8 | |

| SP_1025 | Hypothetical protein | 2.0ns | 4.6 | 2.7 | |

| SP_1059 | Hypothetical protein | 0.8ns | 3.9 | 3.3 | |

| SP_1465 | Hypothetical protein | 2.6 | 4.1 | 5.7 | |

| SP_1635 | Hypothetical protein | 1.0ns | 2.7 | 2.7 | |

| SP_1931 | Hypothetical protein, fusion | 2.1 | 3.0 | 3.8 | |

| SP_1995 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 1.0ns | 4.1 | 0.4 | |

| SP_2098 | Hypothetical protein | 2.6 | 11.4 | 13.9 | |

ns, not significant; NA, not available.

MFS, major facilitator superfamily.

TABLE 2.

Targeted S. pneumoniae genes of mutants enriched during experimental meningitis

| TIGR4 locus by role category | Gene name | Annotation | Negative fold changea at: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 h | 9 h | 15 h | |||

| Energy metabolism, SP_1853 | galK | Galactokinase | 0.7ns | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Regulatory functions | |||||

| SP_0727 | copY | Transcriptional repressor, putative | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| SP_0743 | Transcriptional regulator, TetR family | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | |

| Transport and binding | |||||

| SP_0321 | PTS system, N-acetylgalactosamine-specific IIA component | 0.8ns | 0.4 | 0.3 | |

| SP_1715 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein; unknown substrate | 0.9ns | 1.8 | 0.2 | |

| SP_1887 | amiF | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein AmiF; oligopeptide | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| SP_2037 | PTS system, ascorbate-specific IIB | NA | 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| Unknown function | |||||

| SP_0166 | Pyridoxal-dependent decarboxylase, Orn/Lys/Arg family | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| SP_1994 | Aminotransferase, class I | 1.0ns | 2.6 | 0.2 | |

| SP_1944 | Putative P-loop hydrolase | 0.8ns | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| Hypothetical, SP_0721 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.8ns | 2.3 | 0.2 | |

ns, not significant; NA, not available.

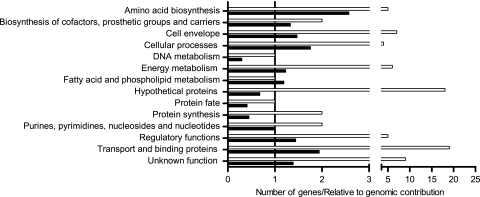

Essential genes were involved mainly in transport and binding or encoded hypothetical proteins. However, relative to their distribution in the genome, genes involved in amino acid biosynthesis and in transport and binding appeared particularly important for pneumococcal survival in experimental meningitis (Fig. 2). We also identified 5 of the 15 S. pneumoniae TIGR4 cps genes, thus showing the importance of this virulence factor. Interestingly, the polysaccharide capsule was the only classical virulence factor identified in this GAF screen. Genes belonging to nine (putative) ABC transporters were identified, four of which are required for amino acid uptake. Furthermore, we identified two phosphotransferase (PTS) systems required for the transport of mannose and cellobiose. Five transcriptional regulators were essential for experimental rabbit meningitis: two of the GntR family, one of the phosphosugar-binding RpiR family, one of the sugar-binding LacI family, and the fatty acid biosynthesis regulator FabT. Genes mutants of which had become enriched during infection represent four transporters, namely, ABC transporters for oligopeptides and an unknown substrate and PTS systems for ascorbate and N-acetylgalactosamine. In addition, we identified one regulator of the TetR family and the putative CopY transcriptional repressor for the CopAB copper transporter.

FIG. 2.

Functional classification of S. pneumoniae TIGR4 genes essential for experimental rabbit meningitis. Open bars represent the absolute number of genes identified within each functional class. Filled bars indicate how often genes within each functional class were selected relative to their contribution to the whole genome.

There was only limited overlap between essential genes found in the different libraries (data not shown), which indicates that the different libraries were highly random. Only 1 gene, encoding the RpmE ribosomal protein L31, was identified in three mutant libraries, and 15 genes were found in two libraries. In all cases, these were genes mutants of which had become attenuated during infection. There were several clusters of conditionally essential genes: five genes of the cps locus; four genes of the branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) ABC transporter and the adjacent SP_0748 gene; and three genes of a putative methionine ABC transporter. Furthermore, we identified three clusters of seemingly unrelated genes: SP_0098, SP_0099, and SP_0101, encoding a putative cyanate transporter and hypothetical proteins; SP_0197 to SP_0199, encoding a putative dihydrofolate synthetase, a hypothetical protein, and cardiolipin synthetase; and SP_1296 to SP_1299, encoding a putative chorismate mutase, flavodoxin, a DHH subfamily protein of unknown function, and the RpmE ribosomal protein L31. There was no clustering of genes mutants of which became enriched during infection.

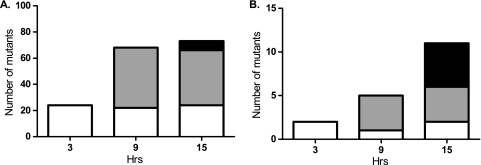

The number of genes selected during the GAF screen increased over time, and attenuated mutants were generally increasingly outgrown as infection progressed. At 3 h, 24 essential genes were selected (Fig. 3 A and Table 1). These were mainly genes for cps biosynthesis, cellular processes, protein synthesis, and nucleotide biosynthesis. From 3 to 9 h, the number of essential genes increased considerably. Genes that became essential at 9 h were mostly involved in transport and binding, amino acid biosynthesis, regulatory functions, cps biosynthesis, and energy metabolism. At 9 to 15 h postinfection, the number of selected genes reached a plateau of 71 and 77 genes, respectively (Fig. 3A). Genes that became essential at 15 h postinfection were, among others, ABC transporters for BCAAs, methionine, polar amino acids, or an unknown substrate. Only two of the genes mutants of which became enriched during infection (Fig. 3B and Table 2) were found at 3 h postinfection. At 9 to 15 h postinfection, the numbers of selected genes increased to 5 and 11, respectively. Only the the AmiF oligopeptide ABC transporter ATP-binding protein was found at all three time points.

FIG. 3.

Time course of selection of genes during the GAF rabbit meningitis screen. Shown are the numbers of mutants with mutations of S. pneumoniae genes that had become attenuated (A) or enriched (B) at 3, 9, or 15 h postinfection. The shading indicates the first time at which genes were selected: 3 (open bars), 9 (shaded bars), or 15 (filled bars) h postinfection. Hrs, time postinfection.

Competitive infection in experimental rat meningitis.

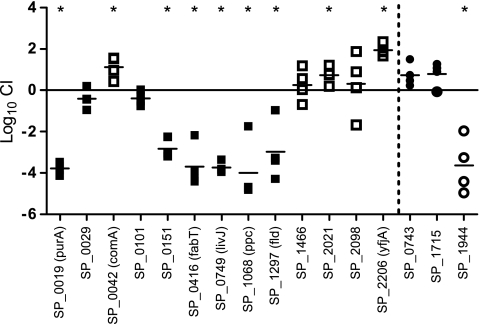

To validate the GAF results, a subset of 16 genes was selected for follow-up experiments (Fig. 4). Eight of the genes—SP_0019 (purA), SP_0029, SP_0042 (comA), SP_0151, SP_0416 (fabT), SP_1944, SP_2021, and SP_2206 (yfiA)—had shown differential regulation during experimental meningitis (24, 26). Similarly, SP_0749 (livJ) is part of the BCAA ABC transporter formerly shown to be upregulated during experimental meningitis (26). SP_1466 (hemolysin), SP_1068 (ppc), SP_0101, SP_1297 (fld), and SP_2098 were selected for validation experiments due to their essential roles in in vivo growth in CSF as early as 3 h postinfection. SP_0743 and SP_1715 were selected to represent genes mutants of which had become enriched during infection.

FIG. 4.

Competitive experimental rat meningitis with 16 mutants and wild-type TIGR4. Shown are log10 CI calculated from CSF sampled from individual rats after a 72-h coinfection with 13 mutants attenuated in GAF (squares) and three mutants enriched in GAF (circles). The horizontal line denotes the mean. Filled squares and circles indicate accordance between the mean log10 CI and the GAF data. Asterisks mark mean log10 CI that are significantly different from zero (P < 0.05).

Of 13 mutants attenuated in GAF, only 6, those with mutations in SP_0019, SP_0151, SP_0416, SP_0749, SP_1068, and SP_1297, were significantly attenuated in competitive infection (Fig. 4). Two mutants, those with mutations in SP_1466 and SP_2098, had abnormally high in vitro growth differences, suggesting that they were subject to general growth inhibition rather than to growth inhibition related to the in vivo challenge conditions. Surprisingly, three mutants were significantly enriched during competitive infection.

Of the three mutants enriched in GAF, a 10-fold (nonsignificant) enrichment was confirmed for two mutants, SP_0743 and SP_1715, in competitive infection, while the third mutant, SP_1944, was significantly attenuated.

The in vitro competitive growth patterns of the four mutants with conflicting CI and GAF data could not explain the differences. The differences may be due to the switch of animal model between the screening and the coinfection experiment, a switch that implies not only a change of species but also a change in the time from inoculation to sampling.

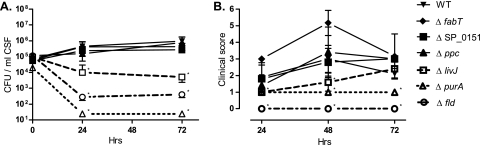

Single infection in experimental rat meningitis.

The pathogenic potentials of the six mutants that were attenuated both in the rabbit GAF screen and in competitive rat infection experiments were tested in a noncompetitive model of rat meningitis. Bacterial concentrations in CSF sampled from rats infected with a mutant with a mutation of PurA adenylosuccinate synthetase, the LivJ substrate binding protein (SBP) of the BCAA ABC transporter, or Fld flavodoxin were significantly lower than those in CSF recovered from wild-type-infected rats (Fig. 5 A). Correspondingly, rats infected with a ΔpurA or Δfld strain had significantly lower disease severity scores than wild-type-infected rats throughout the experiment, and rats infected with the ΔlivJ strain had significantly lower disease severity scores than rats infected with the wild type at 24 and 48 h (Fig. 5). In contrast, despite the attenuation during competitive infection of mutants with a mutation of either the ATP binding protein of the putative methionine ABC transporter (SP_0151), the FabT regulator of fatty acid biosynthesis, or Ppc phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, the bacterial viability counts and clinical signs of disease for rats infected with these mutants were similar to those observed for wild-type-infected rats (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Pathogenic potentials of six GAF targets during experimental rat meningitis. Shown are bacterial loads in CSF at 24 and 72 h (A) and clinical scores of infected rats at 24, 48, and 72 h (B) after intracisternal inoculation of 105 CFU of wild-type S. pneumoniae TIGR4 (WT) or its ΔpurA, Δfld, ΔlivJ, ΔfabT, Δppc, or ΔSP_0151 mutant. Data are means and standard deviations. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) between the wild-type and mutant strains. Hrs, time postinfection.

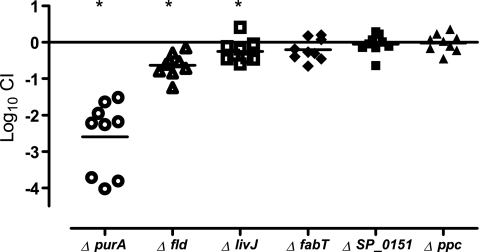

Competitive in vitro growth in h-CSF.

The growth of the six mutants that were attenuated both in the rabbit GAF screen and in competitive rat infection was explored in h-CSF in vitro in competition with the wild-type strain. Although S. pneumoniae TIGR4 had no difficulty growing in h-CSF (data not shown), it appeared that the mutants with reduced abilities to replicate during experimental rat meningitis, i.e., the ΔpurA, Δfld, and ΔlivJ mutants, also showed significant attenuation of growth in h-CSF (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Competitive growth of the ΔpurA, Δfld, ΔlivJ, ΔfabT, ΔSP_0151, and Δppc mutants with wild-type TIGR4 in h-CSF. Shown are individual (symbols) and mean (horizontal lines) log10 CI from 9-h CSF cultures after 4 h of anaerobic in vitro growth. Asterisks mark mean log10 CI that are significantly different from zero (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

This is the first genome-wide search for bacterial genes that are required by S. pneumoniae for replication during meningitis. Screening of 6,000 mutants using the GAF technology allowed us to analyze 90% of the TIGR4 genome for essentiality during experimental meningitis. Importantly, GAF results were obtained by infecting only 16 rabbits, which is only a small fraction of the number of laboratory animals needed for a comparable STM screening, emphasizing the throughput of GAF as an advantageous alternative to STM for identifying genes that are essential during infection.

The 82 pneumococcal genes that we identified as essential for experimental pneumococcal meningitis point to a role for the pneumococcal capsule and otherwise reflect the general restraint on nutrients encountered by the pneumococcus in CSF (8). Overall, the GAF results are in accordance with the results of previous gene expression studies, which showed that genes with higher expression levels in experimental rabbit and mouse meningitis are involved in the biosynthesis of cell envelope components (capsular polysaccharides and the cell wall), energy metabolism, and amino acid biosynthesis and acquisition (26, 28). Similarly, most classic virulence factors found to be repressed during meningitis (26, 28), such as pneumolysin and pyruvate oxidase, were indeed not selected in our study.

The kinetics of the mutants revealed that an increasing number of genes became essential as infection progressed, especially through the first 9 h, and that different stages of infection were characterized by genes with particular roles becoming essential. The increasing number of essential genes paralleled the increasing bacterial concentration in CSF and the concomitant rise in WBC counts throughout the first 9 h of infection (Fig. 1). Generally, genes involved in cps biosynthesis, cellular processes, protein synthesis, and nucleotide biosynthesis were essential throughout infection, whereas genes involved in transport and binding, regulatory functions, energy metabolism, and amino acid biosynthesis became increasingly important as infection progressed.

Comparison of the GAF results with those of gene expression studies may elucidate the role of selected transcriptional regulators during pneumococcal disease. For example, the essential role of the FabT repressor for fatty acid biosynthesis in the GAF meningitis screen is in accordance with the in vivo repression of the fab gene cluster during experimental meningitis (26). Moreover, we identified 11 genes, mainly encoding transporter proteins, expression of which was previously reported to be increased in a fabT mutant (22). Except for fabT itself, these genes do not appear to be regulated by FabT directly but have been suggested to respond to changes in membrane fatty acid composition (22). This suggests that pneumococci encounter an environment in the CSF that induces alterations in their membrane composition.

Compared to the findings of STM studies on pneumococcal genetic requirements for otitis media, pneumonia, and bacteremia, fewer genes were essential in our GAF meningitis screen: 5% of the TIGR4 genes were found to be essential for replication during meningitis, whereas 8% (7), 11% (14), and 10% (20, 31) of pneumococcal genes were identified by STM as essential for otitis media, pneumonia, and bacteremia, respectively. The lower number of essential genes during meningitis is in line with the results of a comparative gene expression study where fewer genes were found to be expressed during experimental meningitis than during bacteremia (28). In contrast to STM results in other models of disease, no classical virulence factors, except for the capsular genes, were identified in the GAF meningitis screen, which likely reflects our experimental model, in which the process of pneumococcal seeding to the meninges is circumvented by direct inoculation of bacteria into the cisterna magna, obviating the need for the classical virulence factors required for adherence and tissue invasion. In the CSF, S. pneumoniae has entered a relatively secluded compartment of the body, characterized by impaired innate and humoral immune responses (36, 40).

Three genes of particular interest were identified during the GAF screen; adenylosuccinate synthetase (PurA), flavodoxin (Fld), and livJ mutants were severely attenuated in experimental rat meningitis and in competitive growth with the wild type in h-CSF. Adenylosuccinate synthetase catalyzes one of the last steps of purine biosynthesis: the conversion of IMP to adenylosuccinate. Since mammalian tissues contain sparse amounts of purines, de novo synthesis is a prerequisite for bacterial growth during infection (23). In E. coli K1, a pathogen causing meningitis in newborns, the purA gene is known to be induced upon association of bacteria with eukaryotic cells and to be important for invasion of human brain microvascular cells (17), and in Haemophilus parasuis, the expression of purA was increased during growth in porcine CSF and in iron-depleted (brain heart infusion [BHI]) growth medium (24). In experimental virulence studies with Salmonella spp. in mice, the 50% lethal dose (LD50) was 108-fold higher for a purA mutant than for the wild-type strain (25), and no mutants were isolated from the gastrointestinal tract beyond 24 h after ingestion (35). A pneumococcal mutant with a mutation of another purine biosynthesis gene, purK, was identified as essential in an STM screen on pulmonary infection and was shown to be attenuated in bloodstream infection (31).

Flavodoxin, encoded by another gene apparently critical in the establishment of experimental meningitis, is an electron transfer protein in several redox reactions. It is known to be an essential protein in Helicobacter pylori infection due to its role as an electron acceptor in the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate (9). In iron-poor media, flavodoxin works as a substitute for iron-containing electron carrier proteins such as ferredoxin (34), and its transcription is upregulated under conditions of iron starvation in H. pylori (19). In E. coli, flavodoxin is known to be involved in methionine synthesis and in the oxidative stress response (34). No role for flavodoxin in pneumococcal infection has been described previously, but the severely attenuated phenotype of the fld mutant in experimental meningitis is in accordance with the findings for other species (5, 19). Moreover, our discovery that genes involved in methionine synthesis and transport were essential for pneumococcal meningitis points to another plausible role for flavodoxin in this process: as a provider of methionine.

The third mutant failing to cause full-blown meningitis was the livJ mutant. livJ encodes the SBP of an ABC transporter of isoleucine, leucine, and valine (1). In a rabbit model of experimental meningitis, the expression of the livHMGF genes (encoding the membrane-spanning part of the transporter) was upregulated (28), and in a recent study, a mutant with a mutation of the same amino acid transporter was found to be attenuated in competitive pneumococcal pulmonary and systemic infections (1). However, a livHMGF deletion mutant did not show reduced virulence in noncompetitive infection (1). Interestingly, the livJ mutant did not show a growth defect during the first 3 h of our GAF screen (Table 1), and the growth defect was only moderate during 4 h of in vitro growth (Fig. 6), suggesting that the attenuation of the livJ mutant relates to the mounting depletion of BCAAs from the environment and that, during the first few hours of growth, the ABC transporter mutant is able to sequester sufficient levels of BCAAs for growth. The differences in the pathogenic potentials of the liv operon mutants between the reported study (1) and ours could be due to the different infection models or could point to a specific role for the SBP LivJ in infection. Such a role is recognized for PsaA, the SBP of an ABC-manganese transporter, known to mediate adherence to eukaryotic cells (32).

By GAF we hoped to be able to identify promising pneumococcal targets for the development of future vaccines or antimicrobials that target pneumococcal disease, and specifically meningitis. Of the three targets identified, only LivJ is predicted to be surface exposed; consequently, it is the most promising candidate for a vaccine lead. Giefing et al. (10) identified serum antibodies against LivJ in blood from patients convalescing after pneumococcal disease. However, when LivJ was tested as a vaccine lead in mice, it was not protective against a pneumococcal bloodstream infection with 200 lethal doses (LD). Since flavodoxin and adenylosuccinate synthetase are both critical for bacterial growth in experimental rat meningitis and in h-CSF, they could be promising targets for pharmacological inhibition. Recent evidence suggests that pneumococcal meningitis should be treated with nonbacteriolytic drugs to minimize cerebral damage and sequelae to infection (12, 37), making the exploration of inhibitory drugs an interesting field of future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by Horizon Breakthrough Grant 93518023 from the Netherlands Genomics Initiative, the Pneumopath project (contract Health-F3-2009-222983) from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7), The Danish Council for Independent Research/Medical Sciences, The Beckett Foundation, and the A. P. Møller Foundation for the Advancement of Medical Science.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 November 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basavanna, S., S. Khandavilli, J. Yuste, J. M. Cohen, A. H. Hosie, A. J. Webb, G. H. Thomas, and J. S. Brown. 2009. Screening of Streptococcus pneumoniae ABC transporter mutants demonstrates that LivJHMGF, a branched-chain amino acid ABC transporter, is necessary for disease pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 77:3412-3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bijlsma, J. J., P. Burghout, T. G. Kloosterman, H. J. Bootsma, A. de Jong, P. W. Hermans, and O. P. Kuipers. 2007. Development of genomic array footprinting for identification of conditionally essential genes in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1514-1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandt, C. T., J. D. Lundgren, S. P. Lund, N. Frimodt-Møller, T. Christensen, T. Benfield, F. Espersen, D. M. Hougaard, and C. Østergaard. 2004. Attenuation of the bacterial load in blood by pretreatment with granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor protects rats from fatal outcome and brain damage during Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis. Infect. Immun. 72:4647-4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandt, C. T., H. Simonsen, M. Liptrot, L. V. Søgaard, J. D. Lundgren, C. Østergaard, N. Frimodt-Møller, and I. J. Rowland. 2008. In vivo study of experimental pneumococcal meningitis using magnetic resonance imaging. BMC Med. Imaging 8:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bueno, M., N. Cremades, J. L. Neira, and J. Sancho. 2006. Filling small, empty protein cavities: structural and energetic consequences. J. Mol. Biol. 358:701-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burghout, P., H. J. Bootsma, T. G. Kloosterman, J. J. Bijlsma, C. E. de Jongh, O. P. Kuipers, and P. W. Hermans. 2007. Search for genes essential for pneumococcal transformation: the RADA DNA repair protein plays a role in genomic recombination of donor DNA. J. Bacteriol. 189:6540-6550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, H., Y. Ma, J. Yang, C. J. O'Brien, S. L. Lee, J. E. Mazurkiewicz, S. Haataja, J. H. Yan, G. F. Gao, and J. R. Zhang. 2008. Genetic requirement for pneumococcal ear infection. PLoS One 3:e2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Terlizzi, R., and S. Platt. 2006. The function, composition and analysis of cerebrospinal fluid in companion animals. Part I. Function and composition. Vet. J. 172:422-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freigang, J., K. Diederichs, K. P. Schafer, W. Welte, and R. Paul. 2002. Crystal structure of oxidized flavodoxin, an essential protein in Helicobacter pylori. Protein Sci. 11:253-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giefing, C., A. L. Meinke, M. Hanner, T. Henics, M. D. Bui, D. Gelbmann, U. Lundberg, B. M. Senn, M. Schunn, A. Habel, B. Henriques-Normark, A. Ortqvist, M. Kalin, A. von Gabain, and E. Nagy. 2008. Discovery of a novel class of highly conserved vaccine antigens using genomic scale antigenic fingerprinting of pneumococcus with human antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 205:117-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomes, H. D., M. Muscat, D. L. Monnet, J. Giesecke, and P. L. Lopalco. 2009. Use of Seven-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (Pcv7) in Europe, 2001-2007. Eurosurveillance 14:2-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grandgirard, D., C. Schurch, P. Cottagnoud, and S. L. Leib. 2007. Prevention of brain injury by the nonbacteriolytic antibiotic daptomycin in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2173-2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guevara, M., A. Barricarte, A. Gil-Setas, J. J. Garcia-Irure, X. Beristain, L. Torroba, A. Petit, M. E. P. Vigas, A. Aguinaga, and J. Castilla. 2009. Changing epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease following increased coverage with the heptavalent conjugate vaccine in Navarre, Spain. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 15:1013-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hava, D. L., and A. Camilli. 2002. Large-scale identification of serotype 4 Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1389-1406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendriksen, W. T., T. G. Kloosterman, H. J. Bootsma, S. Estevao, R. de Groot, O. P. Kuipers, and P. W. M. Hermans. 2008. Site-specific contributions of glutamine-dependent regulator GlnR and GlnR-regulated genes to virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 76:1230-1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hensel, M., J. E. Shea, C. Gleeson, M. D. Jones, E. Dalton, and D. W. Holden. 1995. Simultaneous identification of bacterial virulence genes by negative selection. Science 269:400-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman, J. A., J. L. Badger, Y. Zhang, and K. S. Kim. 2001. Escherichia coli K1 purA and sorC are preferentially expressed upon association with human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Microb. Pathog. 31:69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kellner, J. D., O. G. Vanderkooi, J. MacDonald, D. L. Church, G. J. Tyrrell, and D. W. Scheifele. 2009. Changing epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease in Canada, 1998-2007: update from the Calgary-Area Streptococcus pneumoniae Research (CASPER) Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon, D. H., and J. Versalovic. 2009. Fur-independent induction of Helicobacter pylori flavodoxin-encoding gene (fldA) under iron starvation. Helicobacter 14:141-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau, G. W., S. Haataja, M. Lonetto, S. E. Kensit, A. Marra, A. P. Bryant, D. McDevitt, D. A. Morrison, and D. W. Holden. 2001. A functional genomic analysis of type 3 Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 40:555-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LeMessurier, K. S., A. D. Ogunniyi, and J. C. Paton. 2006. Differential expression of key pneumococcal virulence genes in vivo. Microbiology 152:305-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu, Y. J., and C. O. Rock. 2006. Transcriptional regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 59:551-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McFarland, W. C., and B. A. Stocker. 1987. Effect of different purine auxotrophic mutations on mouse-virulence of a Vi-positive strain of Salmonella dublin and of two strains of Salmonella typhimurium. Microb. Pathog. 3:129-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metcalf, D. S., and J. I. MacInnes. 2007. Differential expression of Haemophilus parasuis genes in response to iron restriction and cerebrospinal fluid. Can. J. Vet. Res. 71:181-188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Callaghan, D., D. Maskell, F. Y. Liew, C. S. Easmon, and G. Dougan. 1988. Characterization of aromatic- and purine-dependent Salmonella typhimurium: attention, persistence, and ability to induce protective immunity in BALB/c mice. Infect. Immun. 56:419-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oggioni, M. R., C. Trappetti, A. Kadioglu, M. Cassone, F. Iannelli, S. Ricci, P. W. Andrew, and G. Pozzi. 2006. Switch from planktonic to sessile life: a major event in pneumococcal pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 61:1196-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orihuela, C. J., G. Gao, K. P. Francis, J. Yu, and E. I. Tuomanen. 2004. Tissue-specific contributions of pneumococcal virulence factors to pathogenesis. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1661-1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orihuela, C. J., J. N. Radin, J. E. Sublett, G. Gao, D. Kaushal, and E. I. Tuomanen. 2004. Microarray analysis of pneumococcal gene expression during invasive disease. Infect. Immun. 72:5582-5596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Østergaard, C., H. B. Konradsen, and S. Samuelsson. 2005. Clinical presentation and prognostic factors of Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis according to the focus of infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 5:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Østergaard, C., T. K. Sørensen, J. D. Knudsen, and N. Frimodt-Møller. 1998. Evaluation of moxifloxacin, a new 8-methoxyquinolone, for treatment of meningitis caused by a penicillin-resistant pneumococcus in rabbits. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1706-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polissi, A., A. Pontiggia, G. Feger, M. Altieri, H. Mottl, L. Ferrari, and D. Simon. 1998. Large-scale identification of virulence genes from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 66:5620-5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajam, G., J. M. Anderton, G. M. Carlone, J. S. Sampson, and E. W. Ades. 2008. Pneumococcal surface adhesin A (PsaA): a review. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 34:131-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ray, G. T., S. I. Pelton, K. P. Klugman, D. R. Strutton, and M. R. Moore. 2009. Cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: an update after 7 years of use in the United States. Vaccine 27:6483-6494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sancho, J. 2006. Flavodoxins: sequence, folding, binding, function and beyond. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63:855-864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sigwart, D. F., B. A. Stocker, and J. D. Clements. 1989. Effect of a purA mutation on efficacy of Salmonella live-vaccine vectors. Infect. Immun. 57:1858-1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simberkoff, M. S., N. H. Moldover, and J. J. Rahal. 1980. Absence of detectable bactericidal and opsonic activities in normal and infected human cerebrospinal fluids: regional host defense deficiency. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 95:362-372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spreer, A., R. Lugert, V. Stoltefaut, A. Hoecht, H. Eiffert, and R. Nau. 2009. Short-term rifampicin pretreatment reduces inflammation and neuronal cell death in a rabbit model of bacterial meningitis. Crit. Care Med. 37:2253-2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Hijum, S. A., A. de Jong, R. J. Baerends, H. A. Karsens, N. E. Kramer, R. Larsen, C. D. den Hengst, C. J. Albers, J. Kok, and O. P. Kuipers. 2005. A generally applicable validation scheme for the assessment of factors involved in reproducibility and quality of DNA-microarray data. BMC Genomics 6:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weisfelt, M., D. van de Beek, L. Spanjaard, J. B. Reitsma, and J. de Gans. 2006. Clinical features, complications, and outcome in adults with pneumococcal meningitis: a prospective case series. Lancet Neurol. 5:123-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zwahlen, A., U. E. Nydegger, P. Vaudaux, P. H. Lambert, and F. A. Waldvogel. 1982. Complement-mediated opsonic activity in normal and infected human cerebrospinal-fluid: early response during bacterial-meningitis. J. Infect. Dis. 145:635-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.