Abstract

The heterotrimeric helicase-primase complex of herpes simplex virus type I (HSV-1), consisting of UL5, UL8, and UL52, possesses 5′ to 3′ helicase, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)-dependent ATPase, primase, and DNA binding activities. In this study we confirm that the UL5-UL8-UL52 complex has higher affinity for forked DNA than for ssDNA and fails to bind to fully annealed double-stranded DNA substrates. In addition, we show that a single-stranded overhang of greater than 6 nucleotides is required for efficient enzyme loading and unwinding. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays and surface plasmon resonance analysis provide additional quantitative information about how the UL5-UL8-UL52 complex associates with the replication fork. Although it has previously been reported that in the absence of DNA and nucleoside triphosphates the UL5-UL8-UL52 complex exists as a monomer in solution, we now present evidence that in the presence of forked DNA and AMP-PNP, higher-order complexes can form. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays reveal two discrete complexes with different mobilities only when helicase-primase is bound to DNA containing a single-stranded region, and surface plasmon resonance analysis confirms larger amounts of the complex bound to forked substrates than to single-overhang substrates. Furthermore, we show that primase activity exhibits a cooperative dependence on protein concentration while ATPase and helicase activities do not. Taken together, these data suggest that the primase activity of the helicase-primase requires formation of a dimer or higher-order structure while ATPase activity does not. Importantly, this provides a simple mechanism for generating a two-polymerase replisome at the replication fork.

Replication of DNA genomes is a highly coordinated process that guarantees accurate and efficient inheritance of genetic information. Viruses provide important models for studying the molecular mechanisms involved in eukaryotic DNA replication and its regulation. In fact, much of what we know about cellular DNA replication has come from studying viral systems. Furthermore, viral enzymes involved in replication provide clinically useful targets for antiviral therapy against many viral pathogens. Herpes simplex viruses (HSVs) encode seven viral proteins required for viral DNA replication: an origin binding protein (UL9), a single-strand binding protein (ICP8), a two-subunit polymerase (UL30-UL42), and a three-subunit helicase-primase complex (UL5, UL8, and UL52). The viral polymerase and helicase-primase complex proteins have both been exploited as targets for antiviral therapy (reviewed in reference 17).

During HSV-1 replication, the origin binding protein UL9, in conjunction with the viral single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) binding protein, ICP8, is believed to interact with an HSV origin causing an initial distortion (6, 8). By analogy with other well-characterized replication systems, the heterotrimeric HSV-1 helicase-primase complex is believed to be recruited to the replication fork, where it subsequently unwinds the duplex DNA (helicase activity) and synthesizes short RNA primers to initiate DNA replication (primase activity) (7, 15, 39). Several lines of evidence suggest that, in addition to enzymatic functions, HSV-1 helicase-primase acts as a scaffold for recruitment of viral proteins to prereplicative sites, leading to the formation of replication compartments (9, 13, 37, 51). In addition to interactions among the subunits of the helicase-primase complex itself, UL5, UL8, and UL52 have also been reported to interact with other replication proteins such as UL9, ICP8, and UL30-UL42 (7, 10, 15, 23, 27, 35, 39, 40, 42, 48). Thus, the H/P complex is thought to play a critical role in assembly of the replication machinery at the replication fork as well as in the replication process itself.

Despite the recognition more than 2 decades ago that UL5, UL52, and UL8 comprise the HSV helicase-primase complex (19, 20), many questions remain regarding the mechanism of action of this complex at the replication fork. For instance, an unambiguous assignment of functions to the individual subunits has been complicated by the fact that UL5 and UL52 are functionally interdependent. It is known that UL5 contains seven motifs that are conserved in other helicase superfamily I proteins and that mutations in these motifs abolish ATPase and helicase activity of the helicase-primase complex (25, 53). UL52 contains an internal DXD motif that is highly conserved in different primases. Mutations in this motif abolish the primase activity but not the helicase activity of the helicase-primase (22, 31). On the other hand, mutations in the UL52 zinc finger motif affect DNA binding of the entire complex, and mutations in UL5 affect primase activity (4, 16). Furthermore, mutations causing resistance to helicase-primase inhibitors have been mapped to both UL5 and UL52 subunits, suggesting that interactions of these two subunits create a composite substrate binding surface (2, 5, 30, 36). Recent studies with subcomplexes containing various subsets of the helicase-primase complex subunits suggest that UL52-UL8 complex can polymerize nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs) onto an RNA primer-template, indicating that UL52 contains the active site for phosphodiester bond formation (14). However, initiation of primer synthesis on ssDNA requires a UL5-UL52 subcomplex, suggesting that UL5 contributes residues essential for the initiation of primer synthesis. Taken together, these observations indicate that UL5 and UL52 likely encode the helicase and primase subunits, respectively, as originally suggested (21); however, the functional interdependence between the UL5 and UL52 subunits (3, 4, 14, 16, 25) presents interesting challenges in terms of mapping functional domains such as DNA binding sites.

The UL52 subunit contains a C-terminal zinc finger motif that is conserved in prokaryotic, eukaryotic, and viral primases (28, 43). By analogy with the T7 primase, the zinc finger motif may function in sequence-specific DNA recognition (29, 33, 34). As mentioned above, mutations in this region abolish not only primase activity but also DNA binding and helicase activities, suggesting that at least one DNA binding site in the helicase-primase complex resides within UL52 (3, 16). It is likely that at least one additional DNA binding site exists within the UL5 helicase subunit itself. The functional interdependence between UL5 and UL52 may reflect the presence of shared DNA binding sites between these two subunits.

A major unanswered question relates to how the helicase and primase activities are coordinated at the replication fork. For instance, the UL5 helicase tracks along the lagging strand with 5′ to 3′ polarity (19, 20), but the primase would be expected to synthesize primers in the opposite direction. Interestingly, primase activity can be detected in assays that use a single-strand oligonucleotide as a substrate; however, primase activity is inefficient in assays using forked substrates (K. L. Graves-Woodward and S. K. Weller, unpublished data; K. A. Ramirez-Aguilar and R. D. Kuchta, unpublished data). In this paper, we demonstrate that primase activity exhibits cooperative dependence on protein concentration, while ATPase and helicase activities do not. These results suggest that primase activity requires multimerization of the helicase-primase complex, while helicase activity does not. Models for helicase-primase function at the replication fork will be discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and reagents.

Wild-type UL5-UL8-UL52 complex was expressed in insect cells coinfected with recombinant baculoviruses encoding UL5, His-tagged UL8, and UL52 (45). The heterotrimeric complex was purified on a HIS-Select nickel affinity column (purchased from Sigma) as previously described (16). DNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). 32P-labeled NTPs were purchased from Perkin-Elmer Life Science (Boston, MA).

Substrate preparation.

Structures and sequences of the artificial substrates for each experiment are described in the individual figures. Single-stranded oligonucleotides were 5′ end labeled using [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol, or 222 TBq/mmol) and polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). To generate duplex, triplex, or cruciform structures, labeled oligonucleotides were annealed to one or more unlabeled DNA oligonucleotides at a ratio of 1:3 in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 80 mM KCl, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Components were mixed together, boiled for 10 min, and slow-cooled to room temperature. All substrates used in this study were PAGE purified, resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl-1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), and quantified by GeneQuant, version 2.0.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

DNA binding reactions were performed as previously described (16). Reaction mixtures contained 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 4% glycerol, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.5 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, and 10 nM 32P-labeled substrate, as well as 50 or 200 nM UL5-UL8-UL52, unless otherwise indicated. Reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 30 min, followed by addition of 1 μl of 10× gel loading buffer containing 250 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 40% glycerol, and 0.1% bromophenol blue. Products were resolved by 4% nondenaturing PAGE, visualized, and analyzed using a Storm Phosphorimager (Amersham Biosciences) and ImageQuant software (version 2.1). Binding efficiency was defined as follows: [free DNA]/([free DNA] + [DNA + protein]) × 100%. Each measurement was repeated at least three times.

Helicase assay.

DNA unwinding reactions were performed as previously described (16). Reaction mixtures contained 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 10% glycerol, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM ATP, 10 nM 32P-labeled substrate, and increasing amounts of UL5-UL8-UL52 protein complex. In order to prevent reannealing of the labeled strand after unwinding, reaction mixtures also contained excess (50 nM) unlabeled oligonucleotide corresponding to the labeled strand as a molecular trap. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and terminated with 5× stop buffer containing 250 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 40% glycerol, and 0.1% bromophenol blue. Products were resolved by 10% nondenaturing PAGE, visualized, and analyzed using a Storm Phosphorimager (Amersham Biosciences) and ImageQuant software (version 2.1). Unwinding efficiency was defined as follows: [ssDNA]/([ssDNA] + [substrate]) × 100%. Each measurement was repeated at least three times.

SPR.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) measurements were performed using a Biacore T100 (Biacore). Biotinylated DNA substrates were immobilized on a streptavidin-coated sensor chip (Biacore type SA). The DNA sequence and structure of substrates used for SPR were as shown in Fig. 5A. For the 3′-overhang DNA the amount of immobilized ligand corresponded to 700 resonance units (RUs), or 29 fmoles of DNA, resulting in a concentration of 240 μM in the surface matrix. For the 5′-overhang DNA the amount of immobilized ligand corresponded to 560 RUs, or 23 fmoles of DNA, resulting in a surface concentration of 190 μM. For forked DNA the amount of immobilized ligand corresponded to 690 RUs, or 23 fmoles of DNA, resulting in a surface concentration of 190 μM. Different concentrations (2.5 to 40 nM) of protein analyte (UL5-UL8-UL52) in HBS buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, containing 3 mM EDTA, 0.15 M NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2 and 0.05% surfactant P20), with or without 10 mM AMP-PNP, were injected over the sensor surface at a flow rate of 30 μl/min for 180 s. Postinjection dissociation was monitored in HBS buffer for 180 s at the same flow rate. BSA was used as a control for nonspecific binding. The surface was regenerated between injections using 2.5 M NaCl at a flow rate of 100 μl/min for 20 s. Sensorgrams were fitted to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model using Biacore T100 evaluation software.

Primase assay.

Primase activity was measured as previously described (44). Assays (10 μl) contained 1 μM ssDNA template, [α-32P]NTPs, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, and 10 mM MgCl2. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 60 min and quenched with 25 μl of formamide-0.05% xylene cyanol and bromophenol blue. Products were separated by 20% denaturing PAGE and analyzed using a Typhoon Phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics) and ImageQuant software (version 2.1). Data were fitted to a monomer-dimer equilibrium model where only the dimer has activity, as described in Graziano et al. (26).

DNA-dependent ATPase assay.

Assays (5 μl) typically contained (200 nM to 1 μM) ssDNA, 100 μM to 5 mM [α-32P]ATP, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, and 1 mM DTT. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and quenched with 2.5 μl of 1 M EDTA. Products were separated on polyethyleneimine (PEI)-cellulose thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates by (J. T. Baker) in 0.34 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5. To enhance resolution, the plates were prerun in H2O and dried prior to sample spotting and chromatography. The products were analyzed using a Typhoon Phosphorimager and ImageQuant software.

RESULTS

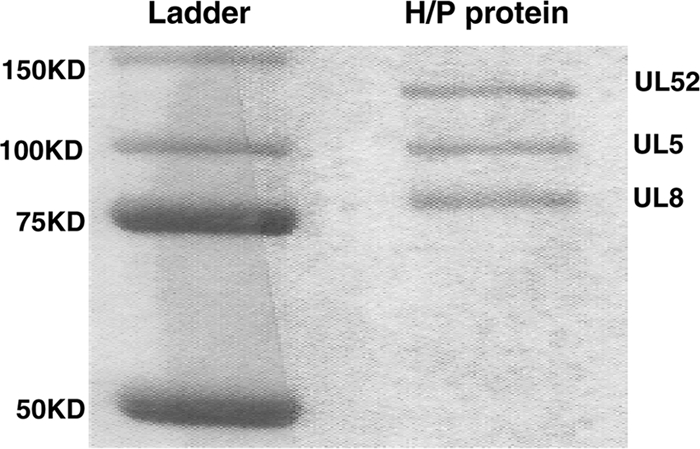

We have shown previously that HSV-1 helicase-primase subcomplex containing only two subunits (UL5 and UL52) displays a preference for binding to forked substrates over ssDNA and exhibits minimal binding to fully annealed double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) (4), suggesting that a single-stranded region is required for efficient enzyme binding. These studies lacked UL8, an essential component of the helicase-primase, and examined a limited set of substrates, Therefore, we extended this analysis to the heterotrimeric UL5-UL8-UL52 complex and additional DNA structures to provide insights into the function of UL8 and further characterize the DNA binding preferences of the complex. The UL5-UL8-UL52 complex was purified from insect cells infected with recombinant baculoviruses, as described in Materials and Methods. Figure 1 shows a Coomassie-stained gel indicating that all three subunits are present in roughly equimolar amounts and that the level of purity is high.

FIG. 1.

Purified UL5-UL8-UL52 complex. The UL5-UL8-UL52 complex was purified from Sf9 insect cells that had been coinfected with recombinant baculoviruses encoding UL5, His-UL8, and UL52. The protein was purified on a HIS-Select nickel affinity column as described in Materials and Methods. Products were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE subsequently stained with Coomassie blue. Molecular mass markers are shown in the left lane, and purified the helicase-primase complex is shown in the right lane.

A single-stranded DNA region is required for efficient HSV-1 helicase-primase loading and unwinding.

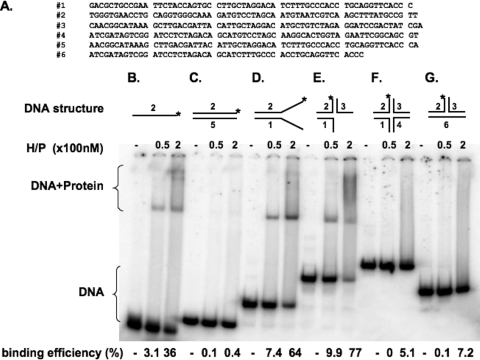

In order to test the hypothesis that an ssDNA region is required for efficient enzyme loading, we examined the DNA binding activity of the helicase-primase UL5-UL8-UL52 by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) (Fig. 2). Substrates tested included ssDNA (Fig. 2B), fully annealed dsDNA (Fig. 2C), forked DNA (Fig. 2D), a three-way junction substrate (Fig. 2E), a cruciform substrate (Fig. 2F), and a T-shaped substrate without any ssDNA regions (Fig. 2G). The heterotrimeric helicase-primase complex (UL5-UL8-UL52) was able to efficiently bind substrates containing ssDNA regions, i.e., ssDNA, forked DNA, and DNA with three way junctions. Helicase-primase complex showed a preference for binding to forked DNA over ssDNA. This result is consistent with our previous finding that the UL5-UL52 subcomplex also showed a strong preference for forked substrates (4) and indicates that UL8 does not alter this preference. Substrates that contain no ssDNA, including fully annealed double-strand DNA and cruciform and T-shaped substrates, did not bind detectably to the enzyme.

FIG. 2.

A single-stranded region is required for efficient enzyme loading. (A) The sequences of the oligonucleotides used to prepare artificial substrates are shown. (B to G) DNA binding ability was examined by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) between the helicase-primase complex (H/P) and ssDNA (B), fully annealed double-stranded DNA (C), forked DNA (D), a three-way junction substrate (E), a cruciform substrate (F), and a T-shaped substrate without any ssDNA region (G), respectively. A schematic of the substrate is indicated above each panel. The star (*) indicates the position of the 32P label. Binding efficiency is shown below the lanes. Substrates were prepared as described in Materials and Methods by annealing different oligonucleotides, shown in panel A. Reaction mixtures contained 50 or 200 nM enzyme. A minus sign above the lanes indicates control reactions (no enzyme).

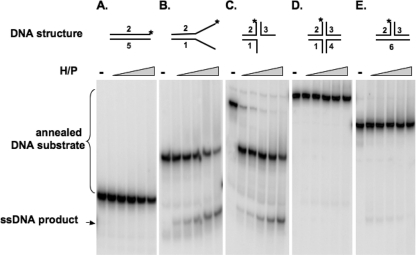

To further probe the interactions of different DNAs with helicase-primase complex, we examined the ability of the helicase to unwind various DNA substrates (Fig. 3). Consistent with the results observed in the DNA binding assays, helicase-primase efficiently unwound the forked substrate (Fig. 3B) and the three-way junction substrate (Fig. 3C), resulting in release of ssDNA products that migrate at the bottom of the gel. Partial unwinding of the three-way junction substrate produced some forked intermediate, shown at the middle of the gel. A clear preference for substrates containing ssDNA is evident since no significant unwinding was observed with dsDNA (Fig. 3A), cruciform (Fig. 3D), and T-shaped (Fig. 3E) substrates. These results indicate that a single-stranded region is required for efficient enzyme binding and unwinding.

FIG. 3.

A single-stranded region is required for efficient unwinding. The unwinding activity of the helicase-primase complex (H/P)was assayed with different substrates: fully annealed double-stranded DNA (A), forked DNA (B), a three-way junction substrate (C), a cruciform substrate (D), or a T-shaped substrate without any ssDNA region (E). A schematic of the substrate is indicated above each panel. The asterisk (*) indicates the position of the 32P label. Concentrations of the enzyme were 25, 50, 100, 200, and 400 nM. A minus sign above the lanes indicates control reactions (no enzyme).

Since recombination is thought to play a major role in HSV DNA replication (39, 52), we investigated whether the HSV-1 helicase-primase might play a role in Holliday junction branch migration. It was shown that the bacteriophage T4 UvsW helicase can bind and unwind cruciform substrates (12), indicating a possible role in branch migration during recombination. Figure 3D shows that the HSV-1 helicase-primase was unable to bind and unwind the cruciform substrate, suggesting that the helicase-primase is not likely to participate directly in HSV-1 Holliday junction branch migration.

Helicase-primase complex translocates in a 5′ to 3′ direction.

We next examined the minimal length of the ssDNA region needed for the helicase-primase to bind and confirmed the previously reported 5′ to 3′ polarity of this enzyme (19). We performed a series of helicase assays on partially double-stranded substrates that contained either 5′ or 3′ ssDNA overhangs of various lengths (Fig. 4A). Reactions were performed for 30 min, and unwinding efficiency was determined. Forked DNA and dsDNA were used as positive and negative controls, respectively (Fig. 4B). At the 30-min time point, forked DNA showed an unwinding efficiency of 26% while dsDNA exhibited very little unwinding.

FIG. 4.

The helicase-primase complex (HP)translocates along ssDNA primarily in a 5′ to 3′ direction. (A) Sequences of the substrates used. The labeled oligonucleotides are in italic. (B) Helicase assay using fork-15 and dsDNA. (C) Helicase assay using 5′-overhang substrates containing an extension of 3 nt, 6 nt, 9 nt, 12 nt, or 15 nt, as indicated above the lanes. (D) Helicase assay using 3′-overhang substrates containing an extension of 3 nt, 6 nt, 9 nt, 12 nt or 15 nt, as indicated above the lanes. Values for unwinding efficiency are shown below the lanes. A schematic of the substrate is shown above the panel. The asterisk (*) represents the location of the 32P label. A minus sign above the lanes indicates control reactions (no enzyme). Reaction mixtures contained 200 nM protein.

When comparing unwinding of substrates with 5′ overhangs (Fig. 4C) to those with 3′ overhangs (Fig. 4D), we observed that substrates with 5′ overhangs are preferred over substrates with 3′ overhangs. These results confirm that the helicase-primase translocates along ssDNA primarily in a 5′ to 3′ direction, with minimal ability to translocate in the 3′ to 5′ direction (19). We also observed that, within each group, substrates with longer ssDNA regions displayed more robust helicase activity than those with shorter ssDNA regions. A significant increase in unwinding efficiency was observed when the length of the ssDNA region was changed from 6 nucleotides (nt) to 9 nt, suggesting that >6 nt of single-stranded DNA are required for efficient enzyme unwinding. Previous reports suggested that binding of UL5-UL52 to DNA requires at least 12 nt of ssDNA if the entire DNA is single stranded (18). The difference between the previous study and this one could reflect the fact that we are using a heterotrimeric complex of UL5-UL8-UL52 and that UL8 reduces the amount of DNA needed for efficient protein binding. Additionally, the length of the ssDNA region required to bind a forked DNA may be smaller than that needed to bind purely ssDNA due to interactions of the helicase-primase complex with the dsDNA at the fork (3).

HSV-1 helicase-primase binds to substrates with 3′ and 5′ overhangs with comparable affinities.

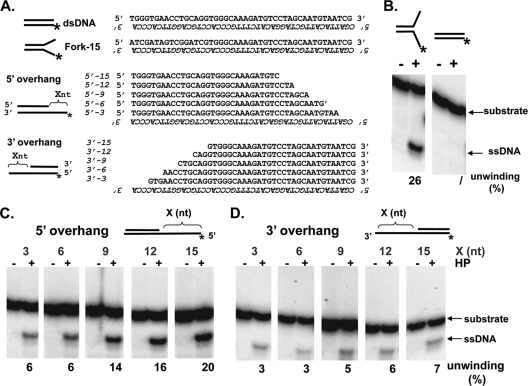

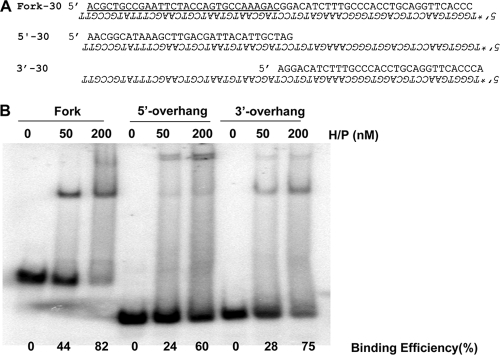

As shown above, UL5-UL8-UL52 prefers to unwind substrates with a 5′ overhang over those with a 3′ overhang. Since DNA binding precedes unwinding, we next asked whether the preference for unwinding substrates with a 5′ overhang reflects preferential binding of UL5-UL8-UL52 to substrates with 5′ overhangs. Binding of UL5-UL8-UL52 to forked, 5′-overhang, and 3′-overhang DNA substrates was measured by EMSA. Figure 5 shows that all three DNA substrates were shifted in the presence of helicase-primase at concentrations of 50 or 200 nM (Fig. 5). The binding efficiencies at 200 nM protein were 82% for the forked substrate, 60% for the substrate containing a 30-nt 5′ overhang (5′-30), and 75% for the substrate containing a 30 nt 3′ overhang (3′-30), indicating that helicase-primase can bind all three substrates efficiently. The forked substrate contains two 30-nt single-strand regions. In each case, two shifted bands were observed, and at higher protein concentrations the slower-migrating band increased in prominence in the reactions with the fork and the 5′-overhang substrate. As described below, formation of the supershifted, higher-order complexes may be critical for primase activity.

FIG. 5.

Helicase-primase complex binding to forked and 5′- and 3′-overhang substrates. (A) Sequences of substrates used. Labeled nucleotides are in italics. The forked substrate contains a 30-nt duplex and two 30-nt single-stranded regions (underlined). The 5′- and 3′-overhang substrates contain a 30-nt duplex plus a 30-nt extension. (B) Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed with forked or overhang substrates. Reaction mixtures contained either 50 nM or 200 nM protein (H/P), as indicated above the lanes; control reactions are indicated as 0 nM.

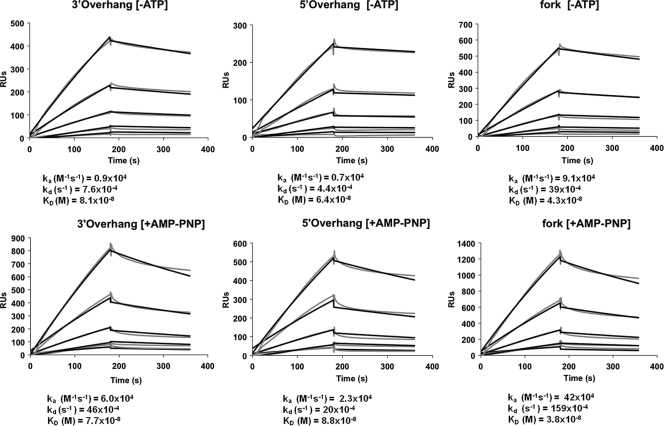

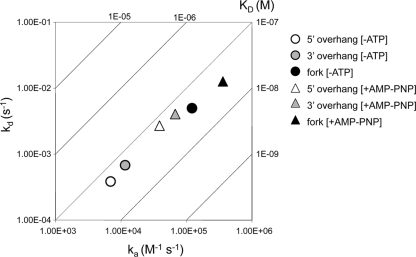

Binding kinetics of the helicase-primase complex to the forked and overhang substrates were analyzed by surface plasmon resonance analysis (SPR). Various DNA ligands containing 5′ or 3′ overhangs were conjugated with biotin and immobilized on a streptavidin-coated chip. SPR measurements were performed using multiple concentrations of helicase-primase (from 2.5 to 40 nM) as the analyte. Sensorgrams, shown in Fig. 6, were fitted to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model to obtain association (ka) and dissociation (kd) rate constants and KD (equilibrium dissociation constant) values, which are plotted on a raPID plot to facilitate comparison of different substrates under different conditions (Fig. 7). KD values for 3′-overhang, 5′-overhang, and forked substrates are comparable at 8.1 × 10−8 M, 6.4 × 10−8 M and 4.3 × 10−8 M, respectively (Fig. 6, top), indicating that the helicase-primase complex binds all three substrates with comparable affinities, which is consistent with the EMSA results. These data also indicate that on- and off-rates are slightly faster for 3′ overhangs than for 5′ overhangs. Interestingly, association and dissociation rates are almost 10-fold faster for forked substrates (Fig. 6 and 7). The increased association rate for binding of helicase-primase to forked substrate compared to single-overhang substrates suggests a difference in the way DNA is contacted by the helicase-primase complex, possibly because in the forked substrate both 5′ and 3′ overhangs are available for binding. The number of RUs for helicase-primase binding to a forked substrate is greater than for helicase-primase binding to single-overhang substrates, indicating higher binding stoichiometry for binding to forked substrates. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the helicase-primase complex can bind to both arms of the fork simultaneously. The increased association and dissociation rates for binding of helicase-primase to forked substrate compared to single-overhang substrates also suggest that the mechanism for helicase-primase binding to the fork differs from that for helicase-primase binding to single-overhang substrates.

FIG. 6.

HSV-1 helicase-primase complex binds to forked and 3′- and 5′-overhang substrates with comparable KDs as assessed by SPR. The DNA sequence and structure of substrates used for SPR were as shown in Fig. 5A. Sensorgrams for different concentrations of enzyme binding to various substrates are shown. Reactions were performed in the absence (top row) or presence (bottom row) of nonhydrolyzable ATP (AMP-PNP). Grey lines show experimental sensorgram data. Black lines show fitted curves obtained by global fitting using a 1:1 Langmuir binding model. A summary of the DNA binding parameters determined from the fitted curves is shown beneath each set of sensorgrams. ka indicates the association rate, kd indicates the dissociation rate, and KD is calculated as kd divided by ka.

FIG. 7.

raPID plot of DNA binding parameters determined in Fig. 6. Association rates (ka) are plotted on the x axis, and dissociation rates (kd) are plotted on the y axis. Dissociation constants (KD) are indicated on the diagonal axis. Open symbols indicate parameters measured in the absence of AMP-PNP. Closed symbols indicate parameters measured in the presence of AMP-PNP.

The bottom panel of Fig. 6 shows sensorgrams for binding in the presence of the nonhydrolyzable ATP analogue, AMP-PNP. The sensorgrams were again fitted with a 1:1 Langmuir binding model. Especially during the dissociation phase, the fit is not as good in the presence of AMP-PNP as in its absence, suggesting that this ligand alters the binding mechanism. Based on fitting to the 1:1 Langmuir binding model, AMP-PNP increases both association and dissociation proportionately for all substrates, such that overall KD values are comparable in the presence and absence of AMP-PNP. More significantly, AMP-PNP increases the number of RUs for helicase-primase binding to different DNA ligands approximately 2-fold compared to sensorgram results in the absence of AMP-PNP. Thus, AMP-PNP appears to increase the stoichiometry of binding at these low protein concentrations.

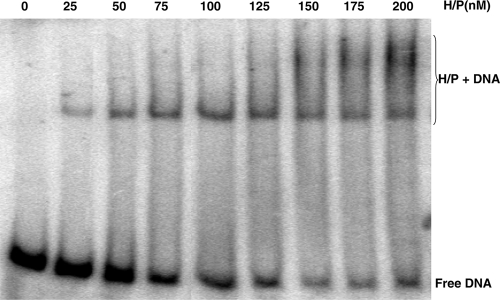

Multimeric helicase-primase binds to DNA substrate at high protein concentrations.

It is not known how the HSV-1 helicase-primase complex balances its two activities, helicase and primase, as these two activities function in opposite directions on the lagging strand. To address this question, we measured the protein concentration dependence of the various activities exhibited by helicase-primase complex. In Fig. 8, DNA binding activity to a forked substrate was measured over a concentration range of 25 to 200 nM. The percent substrate bound increased with protein concentration. At protein concentrations from 25 to 100 nM a single shifted protein/DNA species was detected; however, beginning at 125 nM, a slower-migrating form was also observed. The formation of this supershifted species suggests that, at higher protein concentration, multiple heterotrimeric complexes of helicase-primase bind to a single DNA molecule.

FIG. 8.

EMSA binding assay showing helicase-primase complex (H/P) bound to DNA at increasing protein concentrations. DNA binding of the H/P to the forked substrate described in the legend to Fig. 5 was examined by electrophoretic mobility shift assay at increasing protein concentrations from 0 to 200 nM.

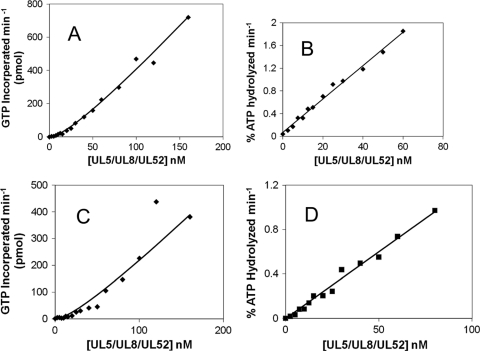

Primase but not helicase and DNA-dependent ATPase activities are cooperative.

The appearance of both shifted and supershifted primase-helicase DNA species in the gel shift assays along with the increased stoichiometry of binding in the presence of AMP-PNP in the SPR experiments suggests that the helicase-primase complex can assemble into higher-order complexes that associate with DNA. Since the formation of higher-order helicase-primase complexes might significantly affect enzyme activity, we measured the effects of various enzyme concentrations on both primase and DNA-dependent nucleoside triphosphatase (NTPase) activity.

Primase activity was measured on 3′-C20GCCC20-5′, a template that has a single canonical initiation site for primer synthesis (the underlined 3′-GCC). Figure 9A shows that in assays containing 500 μM [α-32P]GTP, the rate of primer synthesis increases nonlinearly with increasing protein concentration. In contrast, the rate of DNA-dependent ATP hydrolysis increases linearly with respect to increasing enzyme concentrations (Fig. 9B). The nonlinear increase in primase activity with increasing enzyme concentration indicates that optimal primase activity minimally requires association between at least two UL5-UL8-UL52 heterotrimers. To ensure that the apparent cooperativity of primase activity is not just a function of the particular experimental conditions used in Fig. 9, we measured both primase and DNA-dependent ATPase activity with three different templates (T20GCCCCAT17, T20GTCCT19, and T20GC3TAT14) with various NTP concentrations (0.5 to 5 mM) and with various DNA concentrations (0.2 to 1 μM). In each case, NTPase activity increased linearly with protein concentration while primase activity showed distinct cooperativity (Fig. 9A and C; see also supplemental material) Thus, whereas DNA-dependent ATPase activity behaves noncooperatively, primase activity exhibits cooperativity; i.e., active primase requires at least a (UL5-UL8-UL52)2 complex.

FIG. 9.

Effects of varying the UL5-UL8-UL52 concentration on primase (A and C) and DNA-dependent ATPase (B and D) activity. Assays contained enzyme, 0.2 μM C20GCC(C)20, 500 μM [α-32P]GTP (A), 1 mM [α-32P]GTP (C), 500 μM [α-32P]ATP (B), or 1 mM [α-32P]ATP (D) and were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The line shows the fit with a KD of 50 nM.

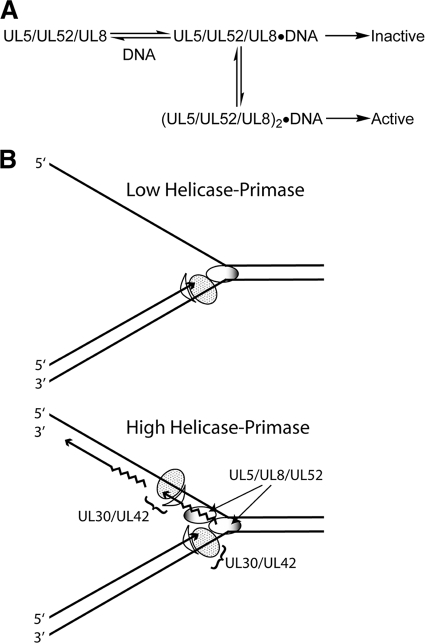

These observations suggest a model where a single UL5-UL8-UL52 heterotrimeric complex lacks primase activity, but when UL5-UL8-UL52 forms higher-order complexes [(UL5-UL8-UL52)n], these complexes exhibit primase activity. The simplest model to explain the data is shown in Fig. 10. According to this model UL5-UL8-UL52 exists in two forms, a “monomer” that lacks primase activity and a “dimer” [(UL5-UL8-UL52)2] that has primase activity. [Note that for simplicity, we will call the single UL5-UL8-UL52 complex a monomer and the (UL5-UL8-UL52)2 complex a dimer.] In this model, formation of the dimer does not affect the DNA-dependent ATPase activity of each monomer. When the helicase-primase complex binds at the replication fork at a low concentration, the helicase activity can unwind the DNA duplex but shows limited primase activity. At higher helicase-primase concentrations, the primase activity is activated to synthesize RNA primers, which can be extended by the DNA polymerase UL30-UL42. This model is consistent with the data shown in Fig. 9.

FIG. 10.

Model. (A) Scheme showing activities monomer or higher- order complexes of the UL5-UL8-UL52 heterotrimeric complex. Our model proposes that a single UL5-UL8-UL52 heterotrimeric complex lacks primase activity, but when UL5-UL8-UL52 forms higher-order complexes [(UL5-UL8-UL52)n], these complexes exhibit primase activity. (B) Replication fork model. The HSV polymerase UL30 and its accessory protein UL42 are drawn as a spotted oval and a crescent, respectively. The UL5-UL8-UL52 helicase-primase ternary complex is depicted as a shaded oval for simplicity. The sawtooth line depicts the RNA primer, and the solid line depicts single-stranded DNA. In the top panel, low concentrations of the helicase-primase complex helicase activity result in unwinding of the duplex DNA but with little or no primase activity observed. At higher concentrations of helicase-primase complex (bottom panel), a dimer or higher-order multimer of the helicase-primase forms at the fork, and under these conditions, RNA primers are synthesized which can then be extended by HSV DNA Pol-UL42.

DISCUSSION

The HSV-1 helicase-primase complex is believed to unwind DNA and synthesize RNA primers on viral DNA; however, little information is available concerning how the heterotrimeric complex is recruited to viral DNA. Although several lines of evidence suggest that the HSV-1 helicase-primase binds DNA (3, 4), it has not been possible to dissect the DNA binding domains on UL5 and UL52, in part because UL5 and UL52 have to be expressed together for de novo primase and helicase activity (11, 14, 21). Cross-linking studies have shown that on forked substrates both subunits contact DNA and that UL52 binds at the ssDNA tail, while UL5 binds to the junction region (3). In this paper we have used a combination of gel shift, surface plasmon resonance, and biochemical assays to study protein-DNA interactions of the helicase-primase complex with various DNA substrates. Similar to UL5-UL52, the UL5-UL8-UL52 complex has higher affinity for forked DNA than for ssDNA and fails to bind to fully annealed dsDNA substrates. Thus, a single-stranded region appears to be required for efficient complex binding. During initiation of HSV DNA synthesis, it is thought that UL9 binds at the origin and, along with ICP8, causes an initial distortion/destabilization of viral DNA (1, 32, 38). It is possible that this initial distortion event creates short ssDNA regions that allow helicase-primase recruitment. Consistent with this model, we demonstrate that efficient enzyme loading and unwinding of dsDNA requires between 6 and 9 nt of ssDNA. Furthermore, we confirm the results of Lehman and colleagues (19), who demonstrated that the HSV-1 helicase-primase complex exhibits a preference for unwinding substrates with a 5′ overhang.

DNA binding ability of the HSV-1 helicase-primase complex.

The experiments presented in this paper indicate that helicase-primase binds to and dissociates from forked substrates significantly faster than from single-overhang substrates. Faster on-rates with forked substrates may reflect additive multisite binding because of the presence of 5′ and 3′ overhangs, both of which can bind to helicase-primase complex. Since in vivo helicase-primase is more likely to encounter forked substrates than single-overhang substrates, the kinetic properties for forked substrates are more physiologically relevant to the function of helicase-primase. Rapid association/dissociation of the helicase-primase complex with DNA at the fork may facilitate the various functions of this protein better than slower binding and unbinding. The presence of AMP-PNP increases the apparent binding stoichiometry approximately 2-fold and increases the apparent on- and off-rates for binding of helicase-primase to DNA substrates approximately 10-fold. The SPR data were fitted to a 1:1 binding model, which is the simplest possible model. However, it is possible that a more complicated binding model involving dimers or higher-order oligomeric structures would be more appropriate. Experiments are in progress to more accurately define the parameters for binding and dissociation of helicase-primase complex to DNA to further constrain the binding model.

The increased binding stoichiometry in the presence of AMP-PNP implies that AMP-PNP and, by extension, ATP facilitates oligomerization of the helicase-primase complex. Since cells generally contain high levels of ATP, ATP-dependent oligomerization of helicase-primase is likely to be physiologically relevant. In this regard, Lehman and coworkers showed that in the absence of DNA and NTPs, helicase-primase exists as a monomer in solution (18). Our results indicate that in the presence of AMP-PNP, helicase-primase binds to DNA as an oligomeric complex, suggesting that binding of these ligands (NTP and DNA) causes a conformational change that allows helicase-primase complex to dimerize or form higher-order complexes.

We also report in this paper that the UL5-UL8-UL52 complex can bind, load, and unwind DNA substrates that contain between 6 and 9 nt of ssDNA. This is in contrast to previous reports that binding of the UL5-UL52 complex to DNA requires at least 12 nt of ssDNA (27a). We suggest that the presence of UL8 in the heterotrimeric helicase-primase reduces the length of ssDNA required for efficient loading. Thus, although UL8 does not exhibit DNA binding activity on its own, it appears to modulate DNA binding by UL5-UL52.

Helicase-primase complex forms higher-order complexes.

Perhaps the most important finding is that dimers or higher-order oligomeric complexes of the UL5-UL8-UL52 heterotrimer form at the replication fork, as demonstrated by three different experimental approaches. (i) Electrophoretic mobility shift assays resolve two discrete complexes, with the slower-migrating species becoming more prominent at higher protein concentrations. (ii) Surface plasmon resonance analyses indicate that larger amounts of complex bind to DNA in the presence of AMP-PNP. (iii) Primase activity assays reveal cooperative dependence on protein concentration while ATPase and helicase activities do not. Together, these three different experimental approaches provide strong evidence for formation of oligomeric complexes of UL5-UL8-UL52 at the replication fork. Besides indicating that the ATPases of each UL5-UL8-UL52 monomer act independently, this result allows us to rule out trivial explanations for the nonlinear kinetics of primase activity, such as protein denaturation at low concentrations or dissociation of the UL5-UL8-UL52 complex, since both primase and ATPase activity require the same subunits. The cooperative behavior appears to be independent of DNA sequence and NTP concentration since it occurred on multiple templates and over a range of NTP concentrations (Fig. 9; see also supplemental material).

The simplest model consistent with the data is that primase can exist as either a monomer or a dimer (Fig. 10). Both the monomer and dimer have DNA-dependent ATPase activity while only the dimer has primase activity. Fitting the various data to this model indicates a dimerization KD of around 50 nM. Interestingly, previous studies by Lehman and coworkers using sucrose density gradient centrifugation showed that 70 nM UL5-UL8-UL52 in the absence of DNA and NTPs exists as a monomer (18). Thus, helicase-primase dimerization either strictly requires these ligands, or DNA and NTPs facilitate dimerization.

The finding that the helicase-primase complex forms at least a dimer provides an explanation for several puzzling observations in herpesvirus replication. First, the helicase moves toward the replication fork while the primase moves away from the fork. By analogy with the bifunctional T7 helicase-primase (50), it is possible that during unwinding, the primase scans along the template until it recognizes a primer synthesis site, whereupon a conformational change occurs that slows the rate of unwinding leading to activation of primase activity. Alternatively, if the helicase-primase forms a dimer where two helicase-primase monomers bind in opposite orientations, this would solve the DNA polarity issue and would allow simultaneous helicase and primase activity.

Second, the observation of primase cooperativity provides a rationale for development of a reconstituted herpesvirus replication system using purified proteins and a minicircle template that generates equal amounts of leading and lagging strand products. A valuable tool for studying coordinated leading and lagging strand synthesis has been to use a single-strand circular DNA molecule with an annealed replication fork. Using purified bacteriophage T7, T4, and E. coli replication proteins, it has been possible to reconstitute the synthesis of both the leading and lagging strands and to demonstrate that synthesis is coordinated and interconnected (46, 50). Herpesvirus replication has been examined using similar assays containing HSV polymerase, single-stranded DNA binding protein, and the helicase-primase complex (24, 25, 31). While this system performs highly efficient strand displacement synthesis mimicking leading strand DNA production, it produces many fewer lagging strand products. However, these reaction mixtures contained low concentrations of helicase-primase complex (14 nM) (24), much less than needed for optimal primer synthesis (see below), which may account for the very inefficient lagging strand synthesis. We have recently generated a herpesvirus replication system on circular templates that generates equal amounts of leading and lagging strand products (47). One of the key requirements is a high concentration of helicase-primase complex (100 to 200 nM). Both biophysical and kinetic assays indicate that the functional form of the helicase-primase complex likely contains at least two copies of the helicase-primase complex [i.e., (UL5-UL8-UL52)2].

Finally, formation of a helicase-primase dimer would also answer a major question regarding the herpesvirus replisome: how does one assemble two DNA polymerases for coordinated leading and lagging strand synthesis? The UL8 subunit of UL5-UL8-UL52 reportedly binds to UL30 of the UL30-UL42 polymerase complex (41). Thus, the presence of two interacting UL5-UL8-UL52 complexes at the replication fork would provide a simple mechanism for recruiting two polymerases to the replication fork (Fig. 10B). The assembly of an HSV replisome at the replication fork is likely to be a complex process requiring all six replication fork proteins, the helicase-primase complex (UL5-UL8-UL52), and the DNA polymerase (UL30-UL42). ICP8, the single-stranded binding protein of HSV, has been reported to stimulate the primase and DNA-dependent ATPase activities of the helicase-primase complex but only if all three subunits are present (27, 48, 49). ICP8 bound to DNA may promote the binding of UL5-UL8-UL52 to DNA through an interaction with UL8 (27). Thus, the UL8 subunit of the helicase-primase complex may play a pivotal role in the assembly of the replisome at the replication fork through its interactions with ICP8 and UL30. According to this model, one UL5-UL8-UL52 would bind the polymerase that replicates the leading strand while a second UL5-UL8-UL52 would bind the polymerase(s) that generates Okazaki fragments on the lagging strand. As noted earlier, the presence of two UL5-UL8-UL52 complexes at the replication fork would also solve the potential problem of the helicase tracking along the lagging strand 5′ to 3′ while primase synthesizes primers 3′ to 5′ with respect to the lagging strand template.

It should be noted that while a DNA-dependent dimerization model accurately describes the observed cooperativity for primase activity, it is possible that the helicase-primase complex forms higher-order structures (trimer, hexamer, etc.). Additionally, it is currently unclear if complex formation absolutely requires DNA and NTPs or if these ligands just lower the KD for complex formation. Experiments to completely define the mechanism of complex formation are in progress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members in the laboratory for helpful comments on the manuscript, Jannette Carey for helpful comments on experimental design, and Johannes Rudolph for assistance with data fitting to the dimerization model.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI-21747 (S.K.W.), NS15190 (J.H.C.), AI-059764 (R.D.K.), and GM-073832 (R.D.K.). The Biacore instrument was purchased with a Shared Instrumentation grant 1S10RR022624-01 from the NIH.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 November 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aslani, A., M. Olsson, and P. Elias. 2002. ATP-dependent unwinding of a minimal origin of DNA replication by the origin-binding protein and the single-strand DNA-binding protein ICP8 from herpes simplex virus type I. J. Biol. Chem. 277:41204-41212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckman, J., K. Kincaid, M. Hocek, T. Spratt, J. Engels, R. Cosstick, and R. D. Kuchta. 2007. Human DNA polymerase alpha uses a combination of positive and negative selectivity to polymerize purine dNTPs with high fidelity. Biochemistry 46:448-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biswas, N., and S. K. Weller. 1999. A mutation in the C-terminal putative Zn2+ finger motif of UL52 severely affects the biochemical activities of the HSV-1 helicase-primase subcomplex. J. Biol. Chem. 274:8068-8076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biswas, N., and S. K. Weller. 2001. The UL5 and UL52 subunits of the herpes simplex virus type 1 helicase-primase subcomplex exhibit a complex interdependence for DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 276:17610-17619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biswas, S., and H. J. Field. 2008. Herpes simplex virus helicase-primase inhibitors: recent findings from the study of drug resistance mutations. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 19:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boehmer, P. E., M. C. Craigie, N. D. Stow, and I. R. Lehman. 1994. Association of origin binding protein and single strand DNA-binding protein, ICP8, during herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA replication in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 269:29329-29334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boehmer, P. E., and I. R. Lehman. 1997. Herpes simplex virus DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66:347-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boehmer, P. E., and I. R. Lehman. 1993. Physical interaction between the herpes simplex virus 1 origin-binding protein and single-stranded DNA-binding protein ICP8. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:8444-8448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burkham, J., D. M. Coen, and S. K. Weller. 1998. ND10 protein PML is recruited to herpes simplex virus type 1 prereplicative sites and replication compartments in the presence of viral DNA polymerase. J. Virol. 72:10100-10107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calder, J. M., E. C. Stow, and N. D. Stow. 1992. On the cellular localization of the components of the herpes simplex virus type 1 helicase-primase complex and the viral origin-binding protein. J. Gen. Virol. 73:531-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calder, J. M., and N. D. Stow. 1990. Herpes simplex virus helicase-primase: the UL8 protein is not required for DNA-dependent ATPase and DNA helicase activities. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:3573-3578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carles-Kinch, K., J. W. George, and K. N. Kreuzer. 1997. Bacteriophage T4 UvsW protein is a helicase involved in recombination, repair and the regulation of DNA replication origins. EMBO J. 16:4142-4151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrington-Lawrence, S. D., and S. K. Weller. 2003. Recruitment of polymerase to herpes simplex virus type 1 replication foci in cells expressing mutant primase (UL52) proteins. J. Virol. 77:4237-4247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavanaugh, N. A., K. A. Ramirez-Aguilar, M. Urban, and R. D. Kuchta. 2009. Herpes simplex virus-1 helicase-primase: roles of each subunit in DNA binding and phosphodiester bond formation. Biochemistry 48:10199-10207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chattopadhyay, S., Y. Chen, and S. K. Weller. 2006. The two helicases of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1). Front. Biosci. 11:2213-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen, Y., S. D. Carrington-Lawrence, P. Bai, and S. K. Weller. 2005. Mutations in the putative zinc-binding motif of UL52 demonstrate a complex interdependence between the UL5 and UL52 subunits of the human herpes simplex virus type 1 helicase/primase complex. J. Virol. 79:9088-9096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coen, D. M., and P. A. Schaffer. 2003. Antiherpesvirus drugs: a promising spectrum of new drugs and drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2:278-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crute, J. J., and I. R. Lehman. 1991. Herpes simplex virus-1 helicase-primase. Physical and catalytic properties. J. Biol. Chem. 266:4484-4488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crute, J. J., E. S. Mocarski, and I. R. Lehman. 1988. A DNA helicase induced by herpes simplex virus type 1. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:6585-6596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crute, J. J., T. Tsurumi, L. A. Zhu, S. K. Weller, P. D. Olivo, M. D. Challberg, E. S. Mocarski, and I. R. Lehman. 1989. Herpes simplex virus 1 helicase-primase: a complex of three herpes-encoded gene products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:2186-2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dodson, M. S., and I. R. Lehman. 1991. Association of DNA helicase and primase activities with a subassembly of the herpes simplex virus 1 helicase-primase composed of the UL5 and UL52 gene products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:1105-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dracheva, S., E. V. Koonin, and J. J. Crute. 1995. Identification of the primase active site of the herpes simplex virus type 1 helicase-primase. J. Biol. Chem. 270:14148-14153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falkenberg, M., D. A. Bushnell, P. Elias, and I. R. Lehman. 1997. The UL8 subunit of the heterotrimeric herpes simplex virus type 1 helicase-primase is required for the unwinding of single strand DNA-binding protein (ICP8)-coated DNA substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 272:22766-22770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falkenberg, M., I. R. Lehman, and P. Elias. 2000. Leading and lagging strand DNA synthesis in vitro by a reconstituted herpes simplex virus type 1 replisome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:3896-3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graves-Woodward, K. L., J. Gottlieb, M. D. Challberg, and S. K. Weller. 1997. Biochemical analyses of mutations in the HSV-1 helicase-primase that alter ATP hydrolysis, DNA unwinding, and coupling between hydrolysis and unwinding. J. Biol. Chem. 272:4623-4630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graziano, V., W. J. McGrath, A. M. DeGruccio, J. J. Dunn, and W. F. Mangel. 2006. Enzymatic activity of the SARS coronavirus main proteinase dimer. FEBS Lett. 580:2577-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamatake, R. K., M. Bifano, W. W. Hurlburt, and D. J. Tenney. 1997. A functional interaction of ICP8, the herpes simplex virus single-stranded DNA-binding protein, and the helicase-primase complex that is dependent on the presence of the UL8 subunit. J. Gen. Virol. 78:857-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27a.Healy, S., X. You, and M. Dodson. 1997. Interactions of a subassembly of the herpes simplex virus type 1 helicase-primase with DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 272:3411-3415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ilyina, T. V., A. E. Gorbalenya, and E. V. Koonin. 1992. Organization and evolution of bacterial and bacteriophage primase-helicase systems. J. Mol. Evol. 34:351-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kato, M., T. Ito, G. Wagner, C. C. Richardson, and T. Ellenberger. 2003. Modular architecture of the bacteriophage T7 primase couples RNA primer synthesis to DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell 11:1349-1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleymann, G., R. Fischer, U. A. Betz, M. Hendrix, W. Bender, U. Schneider, G. Handke, P. Eckenberg, G. Hewlett, V. Pevzner, J. Baumeister, O. Weber, K. Henninger, J. Keldenich, A. Jensen, J. Kolb, U. Bach, A. Popp, J. Maben, I. Frappa, D. Haebich, O. Lockhoff, and H. Rubsamen-Waigmann. 2002. New helicase-primase inhibitors as drug candidates for the treatment of herpes simplex disease. Nat. Med. 8:392-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klinedinst, D. K., and M. D. Challberg. 1994. Helicase-primase complex of herpes simplex virus type 1: a mutation in the UL52 subunit abolishes primase activity. J. Virol. 68:3693-3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koff, A., J. F. Schwedes, and P. Tegtmeyer. 1991. Herpes simplex virus origin-binding protein (UL9) loops and distorts the viral replication origin. J. Virol. 65:3284-3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kusakabe, T., A. V. Hine, S. G. Hyberts, and C. C. Richardson. 1999. The Cys4 zinc finger of bacteriophage T7 primase in sequence-specific single-stranded DNA recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:4295-4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kusakabe, T., and C. C. Richardson. 1996. The role of the zinc motif in sequence recognition by DNA primases. J. Biol. Chem. 271:19563-19570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lehman, I. R., and P. E. Boehmer. 1999. Replication of herpes simplex virus DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 274:28059-28062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liuzzi, M., P. Kibler, C. Bousquet, F. Harji, G. Bolger, M. Garneau, N. Lapeyre, R. S. McCollum, A. M. Faucher, B. Simoneau, and M. G. Cordingley. 2004. Isolation and characterization of herpes simplex virus type 1 resistant to aminothiazolylphenyl-based inhibitors of the viral helicase-primase. Antiviral Res. 64:161-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livingston, C. M., N. A. DeLuca, D. E. Wilkinson, and S. K. Weller. 2008. Oligomerization of ICP4 and rearrangement of heat shock proteins may be important for herpes simplex virus type 1 prereplicative site formation. J. Virol. 82:6324-6336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Makhov, A. M., S. S. Lee, I. R. Lehman, and J. D. Griffith. 2003. Origin-specific unwinding of herpes simplex virus 1 DNA by the viral UL9 and ICP8 proteins: visualization of a specific preunwinding complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:898-903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marintcheva, B., and S. K. Weller. 2001. A tale of two HSV-1 helicases: roles of phage and animal virus helicases in DNA replication and recombination. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 70:77-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marsden, H. S., A. M. Cross, G. J. Francis, A. H. Patel, K. MacEachran, M. Murphy, G. McVey, D. Haydon, A. Abbotts, and N. D. Stow. 1996. The herpes simplex virus type 1 UL8 protein influences the intracellular localization of the UL52 but not the ICP8 or POL replication proteins in virus-infected cells. J. Gen. Virol. 77:2241-2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marsden, H. S., G. W. McLean, E. C. Barnard, G. J. Francis, K. MacEachran, M. Murphy, G. McVey, A. Cross, A. P. Abbotts, and N. D. Stow. 1997. The catalytic subunit of the DNA polymerase of herpes simplex virus type 1 interacts specifically with the C terminus of the UL8 component of the viral helicase-primase complex. J. Virol. 71:6390-6397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McLean, G. W., A. P. Abbotts, M. E. Parry, H. S. Marsden, and N. D. Stow. 1994. The herpes simplex virus type 1 origin-binding protein interacts specifically with the viral UL8 protein. J. Gen. Virol. 75:2699-2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mendelman, L. V., B. B. Beauchamp, and C. C. Richardson. 1994. Requirement for a zinc motif for template recognition by the bacteriophage T7 primase. EMBO J. 13:3909-3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramirez-Aguilar, K. A., and R. D. Kuchta. 2004. Mechanism of primer synthesis by the herpes simplex virus 1 helicase-primase. Biochemistry 43:1754-1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramirez-Aguilar, K. A., N. A. Low-Nam, and R. D. Kuchta. 2002. Key role of template sequence for primer synthesis by the herpes simplex virus 1 helicase-primase. Biochemistry 41:14569-14579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salinas, F., and S. J. Benkovic. 2000. Characterization of bacteriophage T4-coordinated leading- and lagging-strand synthesis on a minicircle substrate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:7196-7201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stengel, G., and R. D. Kuchta. 2011. Coordinated leading and lagging strand DNA synthesis by using the herpes simplex virus 1 replication complex and minicircle DNA templates. J. Virol. 85:957-967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanguy Le Gac, N., G. Villani, J. S. Hoffmann, and P. E. Boehmer. 1996. The UL8 subunit of the herpes simplex virus type-1 DNA helicase-primase optimizes utilization of DNA templates covered by the homologous single-strand DNA-binding protein ICP8. J. Biol. Chem. 271:21645-21651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tenney, D. J., W. W. Hurlburt, P. A. Micheletti, M. Bifano, and R. K. Hamatake. 1994. The UL8 component of the herpes simplex virus helicase-primase complex stimulates primer synthesis by a subassembly of the UL5 and UL52 components. J. Biol. Chem. 269:5030-5035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Toth, E. A., Y. Li, M. R. Sawaya, Y. Cheng, and T. Ellenberger. 2003. The crystal structure of the bifunctional primase-helicase of bacteriophage T7. Mol. Cell 12:1113-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilkinson, D. E., and S. K. Weller. 2004. Recruitment of cellular recombination and repair proteins to sites of herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA replication is dependent on the composition of viral proteins within prereplicative sites and correlates with the induction of the DNA damage response. J. Virol. 78:4783-4796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilkinson, D. E., and S. K. Weller. 2003. The role of DNA recombination in herpes simplex virus DNA replication. IUBMB Life 55:451-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu, L. A., and S. K. Weller. 1992. The six conserved helicase motifs of the UL5 gene product, a component of the herpes simplex virus type 1 helicase-primase, are essential for its function. J. Virol. 66:469-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.