Abstract

The major immediate-early (MIE) gene locus of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is the master switch that determines the outcomes of both lytic and latent infections. Here, we provide evidence that alteration in the splicing of HCMV (Towne strain) MIE genes affects infectious-virus replication, movement through the cell cycle, and cyclin-dependent kinase activity. Mutation of a conserved 24-nucleotide region in MIE exon 4 increased the abundance of IE1-p38 mRNA and decreased the abundance of IE1-p72 and IE2-p86 mRNAs. An increase in IE1-p38 protein was accompanied by a slight decrease in IE1-p72 protein and a significant decrease in IE2-p86 protein. The mutant virus had growth defects, which could not be complemented by wild-type IE1-p72 protein in trans. The phenotype of the mutant virus could not be explained by an increase in IE1-p38 protein, but prevention of the alternate splice returned the recombinant virus to the wild-type phenotype. The lower levels of IE1-p72 and IE2-p86 proteins correlated with a delay in early and late viral gene expression and movement into the S phase of the cell cycle. Mutant virus-infected cells had significantly higher levels of cdk-1 expression and enzymatic activity than cells infected with wild-type virus. The mutant virus induced a round-cell phenotype that accumulated in the G2/M compartment of the cell cycle with condensation and fragmentation of the chromatin. An inhibitor of viral DNA synthesis increased the round-cell phenotype. The round cells were characteristic of an abortive viral infection.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a widespread pathogen, causes asymptomatic and persistent infection in healthy people and severe disease in immunocompromised individuals. It is the leading cause of birth defects by an infectious agent. HCMV has a narrow host range and a prolonged replication cycle. Gene expression occurs in three temporal phases, designated immediate early (IE), early, and late. Transcription of the IE genes occurs at five loci and is independent of any de novo viral protein synthesis. IE gene products activate expression of early viral genes, which are required for viral DNA replication. The late genes, which primarily encode structural proteins, are expressed after viral DNA replication (41).

The major immediate-early (MIE) gene locus, at UL122 and UL123, is the most abundantly expressed region under IE conditions. Driven by the strong enhancer-containing promoter, a single primary transcript with five exons is transcribed, differentially spliced, and polyadenylated to produce multiple mRNA species (64). Two predominant viral gene products, IE1-p72 and IE2-p86, are encoded by mRNAs that contain the first three exons in common but differ in exon 4 (IE1) or exon 5 (IE2). Translation of the two transcripts initiates in exon 2; thus, the IE1-p72 and IE2-p86 proteins have the first 85 amino acids in common (62, 63).

IE1-p72 protein is an acidic nuclear protein and is the most abundant viral protein being expressed at IE times. Transient transfection assays indicated that IE1-p72 protein is able to augment the IE2-p86 protein-mediated transactivation of early viral genes and activate some cellular promoters, as well as its own promoter, through multiple mechanisms (41). Other activities of the IE1-p72 protein include dispersing nuclear domain ND10 (1, 31, 70), antagonizing histone deacetylation (43), blocking apoptosis (73), and binding mitotic chromatin (32, 51). The role of the IE1-p72 protein in productive viral replication was demonstrated with the IE1-null virus CR208. The mutant recombinant virus (RV) was crippled at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) in human foreskin fibroblast (HFF) cells due to a broad blockade in early viral gene expression (15, 17, 40). Further studies revealed that the acidic domain in the C terminus of the IE1-p72 protein (amino acids 421 to 479) expressed in trans dramatically complemented recombinant virus CR208 (51). The acidic domain of the IE1-p72 protein binds to STAT2, which counteracts type I interferon-mediated expression (23, 45).

The IE2-p86 protein is essential for viral replication (39). The viral protein transactivates early viral genes through its interaction with cellular basal transcription machinery (8, 19, 36, 37, 59). The IE2-p86 protein also binds to a 14-bp cis-repressor sequence upstream of the transcription start site and negatively regulates its own transcription (9, 34, 48). The IE2-p86 protein activates numerous E2F-responsive genes (18, 59, 60). Small internal deletions in this viral protein can result in nonviable viruses (67). Notably, just one or two amino acid changes in the carboxyl-terminal region of IE2-p86 protein can severely cripple the virus or lead to nonviable virus (46, 47).

Additionally, several minor, alternatively spliced products are also expressed from the MIE gene locus. A transcript (IE19) arising from the alternative splice site in exon 4 was first reported by Shirakata et al. (57) and later confirmed by Awasthi et al. (2). There are two minor IE2 proteins expressed under immediate-early conditions. IE2-p55 is a positive activator of the MIE promoter when transiently expressed. The IE2-p18 protein is detected only in infected human monocyte-derived macrophages or cycloheximide-treated HFF cells (4, 30). In addition, two gene products, 60 kDa and 40 kDa, encoded by transcripts generated from the IE2 region at late times postinfection have been shown to be required for efficient expression of delayed early and late genes, as well as production of infectious virus (68). All of these studies point to the complexity of differential regulation of the MIE gene locus in different permissive cell types. How alternative splicing of the MIE genes in different cell types affects virus replication and cellular cytopathic effects is not understood.

HCMV is well known for its ability to manipulate host cell cycle pathways and to arrest cell cycle progression (55). Multiple viral proteins have been proposed to contribute to this process in a systematic and redundant manner. Upon virus entry, two tegument proteins, pUL69 and pUL82 (pp71) function to modulate the cell cycle. pUL69 induces the cells to accumulate in the G1 compartment. pp71 accelerates cell cycle progression through the G1 phase by targeting for degradation the hypophosphorylated pocket proteins (Rb, p107, and p130) (20, 28). The MIE proteins also modulate the cell cycle. The IE1-p72 protein was shown to stimulate cells to accumulate in the S and G2/M compartments, possibly through its interaction with pocket protein p107, which relieves the p107-mediated repression of E2F-responsive genes (7, 49). The IE2-p86 protein can push cell cycle progression from G0/G1 to G1/S interphase by activating E2F-responsive genes (60). However, an equally important step is stopping cell cycle progression at the G1/S interphase by the IE2-p86 protein. A mutant virus with a single mutation in amino acid residue 548 of the IE2-p86 protein was unable to inhibit cellular DNA synthesis and cell cycle progression and provided convincing evidence for the important role of IE2-p86 protein in cell cycle arrest (47). In addition, early viral genes affect cell cycle progression. UL97 has cyclin-dependent kinase-like activity, inactivates Rb-family proteins, and affects the replication of the virus (24). UL117 inhibits cellular DNA synthesis by targeting cellular MCM licensing at cellular origins of DNA replication and, consequently, interferes with movement into the S phase (50).

Cyclin-dependent kinase activities are affected during the viral replication cycle. While cyclin A is repressed after HCMV infection, cyclins E and B are induced (27, 58). In addition, cyclin-dependent kinase activity is required for the expression, modification, and localization of viral proteins (53, 54). However, an elevated cyclin-dependent kinase activity in the S phase prevents initiation of IE gene expression (74). Understanding how HCMV activates cell cycle progression, stops cell cycle movement, and controls cellular cyclin-dependent kinases is important and may lead to novel antiviral therapies.

Although the HCMV MIE gene locus and its gene products have been studied extensively, the combined importance of the splicing of the mRNAs, the viral protein levels, and the timing and balance of MIE gene expression have not been addressed before. In this report, we describe for the first time a 24-bp region in MIE exon 4 that affects the splicing pattern of MIE gene transcripts. Three different types of mutations in this region all led to greater utilization of an alternative splice site in exon 4, which was used to generate the IE1-p38 transcript. Along with the enhanced production of the IE1-p38 protein, the IE1-p72 protein was slightly reduced and the IE2-p86 protein was substantially reduced. Mutant RVs with mutations at amino acid residues 412 to 419 showed growth defects at low MOIs in HFF cells. The wild-type IE1-p72 protein in trans did not complement the growth defect. Consistent with the growth defect, early and late viral gene expression and infectious-virus production were delayed. The mutant virus induced a round-cell phenotype that accumulated in the G2/M compartment of the cell cycle with abnormal mitotic figures. The cellular chromosomes were highly condensed and fragmented. However, an inhibitor of viral DNA replication enhanced the round-cell phenotype. Here, we describe an alteration in MIE gene splicing that can lead to abortive viral replication. The role of cellular cdk-1 activity in influencing viral productive or abortive replication is emphasized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

The plasmid pSVCS, containing the MIE enhancer-promoter and UL123-UL121, was described previously (38). A Stratagene QuikChange XL mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used to introduce mutations into exon 4 of UL123 in pSVCS according to the manufacturer's instructions. The IE1 X412 to 419A (X412-419A) mutation that converts the amino acid residues to alanines and a PvuII restriction enzyme site (underlined) were introduced using the oligonucleotide 5′-CCTGTACCCGCGACTGCTGCCGCAGCTGCTGCCGCTGCCGCTGAGAACAGTGATCAG-3′ and its complementary oligonucleotide. The IE1 dl412-419 mutation that deletes the amino acids at residues 412 to 419 was introduced using the oligonucleotide 5′-CCTGTACCCGCGACTGCTGAGAACAGTGATCAG-3′ and its complementary oligonucleotide. The IE1 PuPy412-419 mutation that converts the purines to pyrimidines and the pyrimidines to purines and generates a new PshAI restriction enzyme site (underlined) was introduced using the oligonucleotide 5′-CCTGTACCCGCGACTCAGGGAGACAGGAGTCATCAACACGCTGAGAACAGTGATCAG-3′ and its complementary oligonucleotide. The 3′ alternative splice site in exon 4 was abolished by introducing silent mutations into the wild type and the IE1 X412-419A plasmid, respectively, using oligonucleotide 5′-TGGTGTCACCCCCGGAATCCCCTGTACCCG-3′ and its complementary oligonucleotide.

The plasmid pdlMCATdl-694/-583+Kanr, containing UL122-UL128, including the UL127/chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter and the kanamycin resistance gene, was described previously (33). The UL122-UL123 region of the plasmid pdlMCATdl-694/-583+Kanr was removed and replaced with UL121-UL123 of pSVCS, containing the mutations described above. The final shuttle vectors pIE1WT, pIE1WTSS, pIE1 X412-419A, pIE1 X412-419ASS, pIE1 dl412-419, and pIE1 Pu/Py412-419 were used for transfection of HEK293 cells or for construction of recombinant bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs), as described below.

The plasmid pIE1 X412-419A was further manipulated to generate a revertant (Rev) BAC. The plasmid pΩaacC4, kindly provided by T. Yahr (University of Iowa), was digested with BamHI to isolate the gentamicin resistance (Genr) gene. The kanamycin resistance (Kanr) gene was removed from pIE1 X412-419A and replaced with the Genr gene at the BamHI sites. The X412-419A mutation in exon 4 of the IE1 gene was reverted to the wild type (WT) using the oligonucleotide 5′-CCTGTACCCGCGACTATCCCTCTGTCCTCAGTAATTGTGGCTGAGAACAGTGATCAG-3′ and its complementary oligonucleotide. The resulting shuttle vector pIE1 Rev was used to construct a recombinant BAC.

Cell culture, RVs, and adenovirus vectors.

HFF cells were isolated and grown in Eagle's minimal essential medium (MEM; Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Ihfie1.3 cells, immortalized human foreskin fibroblast cells stably expressing IE1-p72 (17), and HEK293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (Meditech, Herndon, VA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS). All cell cultures were maintained in penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml).

The HCMV Towne BAC DNA was kindly provided by F. Liu (11). Shuttle vectors were linearized by restriction endonuclease digestion with NheI, and the UL121-UL128 DNA fragment was gel purified. Recombinant BACs were generated using the linear UL121-UL128 DNA fragment described above and homologous recombination with Towne BAC in DY380 cells, as described previously (12). BAC DNA was isolated using a Nucleobond BAC Maxiprep kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Recombinant viruses were isolated, propagated, and maintained on ihfie1.3 cells as described previously (17, 26). Briefly, ihfie1.3 cells were transfected with 1 or 3 μg of each recombinant BAC and 1 μg of the plasmid pSVpp71 using the calcium phosphate precipitation method (16). Extracellular fluid was harvested 5 to 7 days after 100% cytopathic effect (CPE) and stored at −80°C in 50% newborn calf serum or used to infect ihfie1.3 cells. The recombinant viruses (RVs) generated from the plasmids described above were designated IE1 WT, IE1 WTSS, IE1 X412-419A, IE1 X412-419ASS, IE1 dl412-419, IE1 Pu/Py412-419, and IE1 Rev, respectively. Virus titers were determined on ihfiel.3 cells by counting either PFU/ml or green fluorescent PFU/ml, as described previously (25).

Replication-defective E1a−, E1b−, and E3− recombinant adenovirus vectors expressing either the tetracycline-inducible “Tet-off” transactivator (AdTrans), the viral IE2-p86 protein (AdIE86), or green fluorescent protein (AdGFP) were described previously (42, 60). The adenovirus vector expressing wild-type IE1-p38 protein (AdIE38) carries the cDNA of IE1-p38 of the Towne strain (Vector Core, University of Iowa). The titers of the various recombinant adenovirus vectors were determined by plaque assay on 293 cells. For transduction experiments, 20 or 10 PFU per cell of recombinant adenovirus vector in Eagle's MEM containing 3 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) per ml for 1 h at 37°C were used. The cells were maintained in complete medium for 24 h and then infected with HCMV Towne at an MOI of 0.05 or 2.

Western blotting.

Cells were harvested, lysed and processed for Western blot analysis as described previously (46, 47). Briefly, cell lysates were fractionated on a 10 or 15% polyacrylamide-sodium dodecyl sulfate gel. Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, and the following antibodies (Ab) were used: anti-MIE monoclonal Ab (MAb) 810 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), anti-IE1 exon4 p63-27 (a kind gift from W. Britt, University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL), anti-UL44 MAb (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA), anti-UL84 (Mab84; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-UL99 MAb (Fitzgerald, Concord, MA), anti-UL83 (Fitzgerald, Concord, MA), anti-β-tubulin MAb (Hybridoma Core, University of Iowa), anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH; Chemicon), and rabbit anti-cdk-1 polyclonal antibody (Calbiochem). Proteins were detected using secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) or secondary HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG and SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence detection reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Flow cytometry.

Analysis of infected cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) was performed as described previously with minor changes (13). Briefly, HFF cells were grown to confluence and maintained at high density for 3 days. Cells were then trypsinized, seeded at a density of 0.75 × 106 to 1.0 × 106 per 10-cm dish, and allowed to settle for 1 h before infection. After 1 h, the cells were washed once and medium was added. At 24 h postinfection (p.i.), cells were harvested by trypsinization, pelleted, and suspended in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Three ml of ice-cold 70% ethanol was then added to the cells, and the mixture was incubated at 4°C for 1 h. Cells were pelleted and stained for 60 min at room temperature in 100 μl of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled MIE-specific antibody MAB810X (Chemicon) in dilution buffer (PBS-1% bovine serum albumin [BSA]-0.1% Tween 20). Two ml of wash buffer (PBS-1% BSA) was added, and the rinsed cells were pelleted by centrifugation. The pellets were then suspended in PBS containing propidium iodide (10 μg/ml) and RNase (100 μg/ml). The cells were analyzed for DNA content and Alexa Fluor 488 positivity on a FACScan flow cytometer. Cell cycle data were analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Immunofluorescence assay.

Cells on coverslips were washed twice in PBS, followed by fixation in ice-cold methanol/acetone (1:1) for 20 min at −20°C. The cells were then washed three times with PBS at room temperature prior to the addition of blocking solution (PBS with 2% bovine serum albumin and 0.01% Tween 20) for 30 min. The cells were incubated with primary mouse monoclonal antibodies diluted in blocking solution for 60 min. After extensive washes in PBS, coverslips were incubated for 50 min with isotype-specific secondary antibody diluted in blocking solution, washed in PBS, and mounted in Vectashield mounting solution with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Cells were examined and photographed under an Olympus DX-51 fluorescence microscope. Primary antibody was anti-IE1-p63-27, anti-phospho-histone H2AX (Ser139) (clone JBW301; Millipore) and anti-phospho-RPA32 (S4/S8) (Bethyl, Montgomery, TX). The secondary antibody was IgG2A-specific Alexa Fluor 568-coupled Ab or IgG-specific Alexa Fluor 488-coupled Ab (Invitrogen).

Mitotic spreads and the DNA damage response.

Mitotic spreads were performed with recombinant virus-infected HFF cells using a method described previously (44). Round cells were blown off the monolayer with medium. Monolayer cells were trypsinized and suspended in medium. After centrifugation (300 × g for 10 min), all but about 50 μl of supernatant was discarded, and the cells were suspended. One ml of 75 mM KCl was added for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were spun, the supernatant was discarded, and the cells were suspended in 300 μl of freshly prepared Carnoy's fixative (3 parts methanol, 1 part glacial acetic acid) for 10 min at room temperature. After centrifugation, the cells were suspended in 100 μl of Carnoy's fixative; 10 μl of this cell suspension was dropped from a height of 10 cm onto a glass slide and allowed to dry. Twelve microliters of Vectashield mounting solution with DAPI (Vector Laboratories) was spotted onto the slide, a coverslip was placed above it, and the edges were sealed with clear nail polish. The morphology of the cell nuclei was examined, and the cell nuclei were photographed under an Olympus BX-51 fluorescence microscope.

Genomic DNA fragmentation analysis.

HFF cells (2 × 106) were harvested at 5 days p.i. for genomic DNA fragmentation analysis using an apoptotic DNA ladder kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunoprecipitation and in vitro kinase assay.

Five million cells were lysed by freezing and thawing with NP-40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 125 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors as described previously (61). Cell lysates were precleared with protein G agarose beads (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and incubated at 4°C for 2 h with anti-cdk-1/cdc2 antibody (Oncogene) plus protein G agarose beads. Immunoprecipitates were washed three times with NP-40 lysis buffer and twice with cdk buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 8.0] containing 10 mM MgCl2). Kinase assays were at 30°C for 30 min in cdk buffer containing 2 μg of purified histone H1 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), 3 μM ATP, and 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP. Reactions were stopped by the addition of an equal volume of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis loading buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8] containing 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.02% bromophenol blue, and 20% β-mercaptoethanol). Samples were fractionated and transferred to PVDF membranes. Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (46, 47).

Quantitative real-time PCR and reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

HCMV MIE, IE1, IE2, UL37x1, and cellular 18S RNAs were detected and quantified using real-time PCR. HFF cells were infected in triplicate with recombinant virus IE1 WT or IE1 X412-419A at an MOI of 0.3. After 8 h, total RNA was isolated using TRIreagent (Invitrogen), treated with RNase-free DNase, and converted to cDNA as described previously (25, 47). Multiplex real-time PCR was performed using 2 μl of 1:10 diluted cDNA, or RNA lacking reverse transcriptase, in a final volume of 20 μl of the Platinum PCR SuperMix-UDG cocktail (Invitrogen). Primers and 6-carboxyfluorescein-6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (FAM-TAMRA) probes for HCMV MIE, IE1, IE2, UL37x1, and cellular 18S RNA genes were described previously (47, 53). Viral MIE, IE1-p72, and IE2-p86 mRNA levels were normalized to cellular 18s RNA and viral UL37x1. The value for wild-type virus was set as 1.

For RT-PCR analysis of IE1 transcripts of recombinant viruses, primer exon 1F (5′-CCGGGACCGATCCAGCCTCCGCG-3′), annealed to exon 1, and primer exon 4R (5′-AGTTTACTGGTCAGCCTTGC-3′), annealed to the 3′ end of exon 4, were used as reported previously (2). The same thermoparameters were used to perform PCR, and the amplification products were fractionated in 1% agarose gels.

RESULTS

MIE exon 4 mutation affects MIE gene expression.

Previously, we used multiple sequence alignment to identify conserved functional protein motifs in the IE2-p86 protein of HCMV (46, 47). We employed the same strategy for the IE1-p72 protein. Since amino acid residues 412 to 419 share high homology among the primate CMV homologs (Fig. 1), we determined the effect of mutation in this region on virus replication. Mutant shuttle vectors with the residues 412 to 419 of IE1 were either replaced by alanines, deleted, or altered as shown in Fig. 2 A and named pIE1 X412-419A, pIE1 dl412-419, and pIE1 Pu/Py412-419, respectively. We also made silent mutations in a 3′ splice site (SS) upstream of amino acids 412 to 419 in the WT and IE1 X412-419A shuttle vectors and designated the mutations pIE1 WTSS and pIE1 X412-419ASS, respectively (Fig. 2A). To construct recombinant BACs, linear DNA fragments of wild-type or mutant shuttle vectors in the region at UL121 to UL128 were introduced into Escherichia coli DY380 harboring HCMV Towne BAC DNA. Recombinant BACs containing either IE1 WT, WTSS, X412-419A, X412-419A SS, dl412-419, or Pu/Py412-419 were generated. A revertant BAC was constructed by replacing the X412-419A mutation with wild-type sequence and replacing the kanamycin resistance gene with the gentamicin resistance gene.

FIG. 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of the primate CMV IE1-p72 protein homologs. Amino acid sequences for the proteins from human CMV Towne strain IE1 (AAR31448), chimpanzee CMV IE1 (AAM00752), rhesus CMV IE1 (AAB00487), and African green monkey (AGM) CMV IE1 (AAB16882) were aligned using MultAlin. Multiple sequence alignments are displayed using BoxShade. Identical residues appear shaded in black, while similar residues appear shaded in gray. A star indicates a residue that is identical in all four aligned sequences, while a dot indicates a residue that is conserved in at least half of the aligned sequences. The numbers appearing between the species and the amino acid sequence represent the amino acid position for that particular species. A hyphen designates a gap in the sequence that was inserted for optimal alignment. The black bar underlines amino acids 412 to 419.

FIG. 2.

IE1 exon 4 mutations altered MIE gene splicing and expression pattern. (A) Schematic diagram of the NheI-linearized DNA fragment from the shuttle vector carrying mutated IE1 exon 4 for constructing recombinant BACs. The plasmid pdlMCATdl-694/-583+Kan+IE1/IE2 carries the genomic sequence of the HCMV Towne strain from UL121 to UL128. The UL127 locus was replaced by the CAT reporter. A kanamycin resistance (KanR) cassette was inserted between UL127 and UL128 for selection of recombinant BACs. Twenty-four nucleotides of exon 4 that encode amino acid residues from 412 to 419 of IE1-p72 were either mutated or deleted to generate IE1 X412-419A, IE1 dl412-419, and IE1 Pu/Py412-419. The upstream 3′ splice site (3′ss) in exon 4 was mutated in IE1 WTSS and IE1 X412-419ASS recombinant viruses. MIEP, MIE promoter. HFF cells infected with recombinant viruses were harvested at 8 h p.i. (C) or 48 h p.i. (B and D) for MIE mRNA and protein expression analysis. (B) RT-PCR detecting IE1-p72 or IE1-p38 mRNAs as described in Materials and Methods. Mock, mock infected. (C) The levels of viral transcripts in WT and IE1 X412-419A recombinant virus-infected cells were determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods using probes specific for MIE, IE1-p72, and IE2-p86 mRNA. A representative experiment of three is shown here. rel., relative. (D) Protein levels of MIE proteins IE1-p72, IE1-p38, and IE2-p86 were determined by Western blotting with monoclonal antibody MAB810, which recognizes an epitope in exon 2/exon 3 of IE1-p72, IE1-p38, and IE2-p86. Asterisk shows a degraded viral protein in all virus-infected samples.

We used the following criteria to confirm that the recombinant HCMV BACs were correct. (i) E. coli carrying the recombinant BACs were resistant to chloramphenicol (Towne BAC), chloramphenicol and kanamycin (mutant BACs), or chloramphenicol and gentamicin (revertant BAC). (ii) A 957-bp PCR product of exon 4 was digested with restriction endonuclease PvuII for the IE1 X412-419A mutant or PshAI for the IE1 Pu/Py412-419 mutant. The PCR product of IE1 dl412-419 mutant was of a lower molecular weight than the wild type due to a 24-bp deletion. (iii) The recombinant BAC DNAs had a restriction endonuclease profile that reflected only these changes. (iv) The entire MIE regions of recombinant BACs were sequenced, and the results verified that only the intended mutations in exon 4 were present (data not shown).

Recombinant viruses were isolated after transfection of ihfie1.3 cells that express the wild-type IE1-p72 protein in trans. Virus stocks were propagated and titrated in parallel on ihfie1.3 cells.

First, we examined expression of the MIE mRNAs and proteins from the wild type and mutants in exon 4 of IE1 by transfecting HEK293 cells with the shuttle vectors (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Second, we infected the cells with the mutant recombinant viruses at an MOI of 0.5 and analyzed the infected cells for MIE RNAs and proteins (Fig. 2). Whether cells were transfected with shuttle vectors or infected with recombinant viruses, the results were the same. The mutated IE1-p72 mRNAs were expressed at the same size as the wild type except for the deletion mutant pIE1 dl412-419, but the expression level was lower (Fig. 2B, lanes 3, 5, and 6). There was also a smaller transcript of 0.6 kb (IE1-p38 mRNA) at low levels with the wild type and at higher levels with the mutants (Fig. 2B, lanes 1, 3, 5, and 6). When the upstream 3′ splice site was mutated as shown in Fig. 2A, the IE1-p38 mRNA disappeared and the IE1-p72 mRNA was restored to wild-type levels (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 4). We also compared the quantity of MIE, IE1, and IE2 mRNAs by quantitative RT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. Mutant recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A-infected cells had significantly less IE1 (IE1-p72) and IE2 (IE2-p86) mRNA relative to the wild-type virus (Fig. 2C).

Western blot analysis showed a modest decrease in IE1-p72 protein and a substantial decrease in IE2-p86 when the residues at 412 to 419 were mutated (Fig. 2D, lanes 3, 5, and 6). In addition, a 38-kDa protein was detected when the amino acid residues at 412 to 419 in exon 4 were mutated (Fig. 2D, lanes 3, 5, and 6). Mutation at amino acids 412 to 419 of IE1 affected the accumulation of both the IE1-p72 and IE2-p86 viral proteins.

To identify the 0.6-kb small transcript, the PCR band was cloned and confirmed by DNA sequencing to be the cDNA of IE19 (data not shown) (2, 57). IE19, a minor MIE transcript from an alternative splice site in exon 4, was designated according to the viral protein's predicted molecular mass of 19 kDa (57). We designated this protein IE1-p38 according to its apparent molecular mass. The transcript for IE1-p38 is very low in relative amount in cells infected with the wild-type virus (Fig. 2B, lane 1). This explains why the viral protein was not detected in virus-infected cells by Western blotting (57).

As shown in Fig. 2A, the mutation site of pIE1 X412-419A is located 20 nucleotides downstream of an alternative 3′ splice site, which is used to produce the IE1-p38 mRNA. The eight-alanine-encoding sequence introduced into exon 4 enhances the usage of the alternative splice site. These observations indicate that the coding sequence for amino acid residues 412 to 419 of IE1-p72 on exon 4 has a suppressive function on the utilization of the upstream alternative splice site. The mechanism underlying this phenomenon within this region in exon 4 requires further investigation. Notably, the splicing and expression pattern of the MIE genes in the mutant recombinant virus-infected cells is significantly changed due to a mutation in exon 4. Along with increased expression of the IE1-p38 protein, the IE1-p72 protein was expressed at a slightly lower level with X412-419A, and IE2-p86 was significantly reduced with recombinant viruses IE1 X412-419A, IE1 dl412-419, and IE1 Pu/Py412-419 (Fig. 2D).

Recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A has a growth defect.

The IE1-p72 protein is dispensable for virus replication at high MOIs, but not at low MOIs (17). The growth defect of IE1-p72 null HCMV at low multiplicities of infection could be fully rescued by the expression of wild-type IE1-p72 protein in trans in ihfie1.3 cells (17). To determine the effect of mutation of amino acid residues 412 to 419 on viral replication at low MOIs, HFF cells were infected with recombinant viruses IE1 WT, IE1 WTSS, IE1 X412-419A, IE1 X412-419A SS, or IE1 Rev at an MOI of 0.05. Virus titers were determined on ihfie1.3 cells. As expected, wild-type and revertant recombinant viruses had identical growth curves and peak virus titers in HFF cells (Fig. 3 A). In contrast, recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A was approximately 10- to 100-fold lower in titer after infection of HFF cells (Fig. 3A). Mutation of the 3′ splice site upstream of amino acids 412 to 419 for recombinant virus IE1 X412-419ASS restored the wild-type phenotype (Fig. 3B). Since recombinant virus IE1 X412-419ASS did not show a growth defect even though it produced a mutated IE1-p72 protein, the mutated IE1-p72 protein does not lead to the growth defect observed with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A. While HFF cells were unable to rescue recombinant virus CR208 (Fig. 3B), ihfie1.3 cells rescue CR208 as expected, but not IE1 X412-419A (Fig. 3C). These data indicate that the mutation at amino acids 412 to 419 cannot be rescued by wild-type IE1-p72 protein in trans and that the change in IE1-p72 protein is not the reason for the IE1 X412-419A growth defect.

FIG. 3.

Recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A has a growth defect. Cells were infected in triplicate with recombinant viruses at 0.05 PFU/cell. Cells and supernatant were harvested at each time point after infection, and the triplicate samples were pooled and stored. A plaque assay was performed in triplicate on ihfie1.3 cells. A representative experiment of at least three is shown here. (A) HFF cells infected with IE1 WT, IE1 X412-419A, or IE1 Rev. (B) HFF cells infected with IE1 WT, IE1 WT SS, IE1 X412-419A, IE1 X412-419A SS, or CR208. (C) The same as panel B except ihfie1.3 cells were used, which rescues recombinant virus CR208.

Last, we attempted to rescue recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A by preexpression of IE2-p86 using AdIE86 as described in Materials and Methods. One day after transduction with either AdGFP or AdIE86, cells were infected with wild-type virus or recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A at an MOI of 0.2 and analyzed by Western blotting for MIE, early, and late viral gene expression at 48 h p.i. Even though the IE2-p86 protein level was higher after transduction with AdIE86 in both wild-type and mutant recombinant virus-infected cells, the expression levels of immediate-early gene IE1-p72, IE1-p38, early viral gene UL84, and late gene UL99 were lower (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). Preexpression of IE2-p86 repressed immediate-early and early/late viral gene expression and, consequently, we were unable to rescue recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material). However, an inducible and timely expression of IE2-p86 can partially rescue early and late viral gene expression from a mutant recombinant virus (56).

We conclude that the IE1 X412-419A mutation introduced into exon 4 of the MIE gene alters the splicing of the precursor viral RNA, resulting in slower replication of the recombinant virus and lower levels of accumulation of viral progeny.

Viral protein expression is impaired during the replication cycle of recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A.

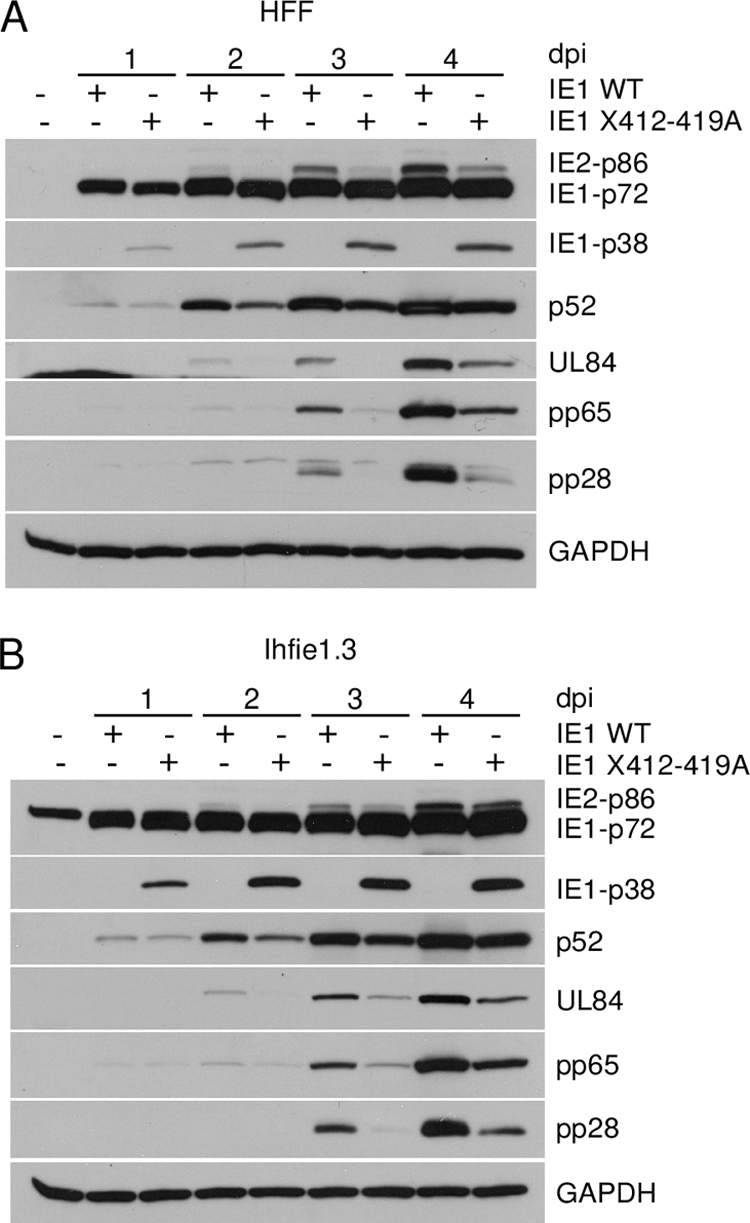

Based on the impaired growth in HFF and ihfie1.3 cells, we further investigated the viral protein expression pattern of recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A in both cell types. HFF and ihfie1.3 cells were infected with recombinant viruses IE1 WT or IE1 X412-419A at the same MOI, 0.2. Cell samples were subjected to Western blot analysis with specific antibodies against representative viral proteins expressed in all three phases of viral infection, IE, early, and late, as described in Materials and Methods. In wild-type virus-infected HFF cells, a typical pattern of IE1-p72 and IE2-p86 protein expression was detected (Fig. 4 A). At 2, 3, and 4 days p.i., the relative amount of IE2-p86 protein was significantly lower with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A (Fig. 4A). IE1-p38 protein, which was not detected in wild-type virus-infected cells throughout all time points, was readily detected in the mutant virus-infected cells. Since the IE2-p86 protein is a major viral transcription activator and is essential for viral replication (64), a delay in IE2-p86 expression was predicted to delay early and late viral gene expression. Expression of the early viral protein UL44 (p52) and UL84 as well as the early/late viral protein UL83 (pp65) and the late viral protein UL99 (pp28) were at lower levels with the mutant virus than with the wild-type virus (Fig. 4A). A similar expression pattern of viral proteins was observed for the ihfie1.3 cells infected with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A (Fig. 4B). Wild-type IE1-p72 protein was expressed in trans in the mock-infected ihfie1.3 cells (Fig. 4B). Therefore, mutated IE1-p72 protein in recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A is not the major reason for the growth defect.

FIG. 4.

Viral protein expression is delayed with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A in both HFF and ihfie1.3 cells. Cells were infected with IE1 WT or IE1 X412-419A recombinant viruses at an MOI of 0.2. Cells were harvested at the time points indicated. MIE viral proteins IE2-p86, IE1-p72, and IE1-p38, early viral proteins UL44 (p52) and UL84, early/late viral protein pp65 and late viral protein pp28, and cellular protein GAPDH were detected using specific antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. (A) HFF cells. (B) ihfie1.3 cells.

IE1-p38 expression does not suppress viral gene expression.

To determine the effect of viral protein IE1-p38 on IE1-p72 or IE2-p86 expression, we preexpressed wild-type IE1-p38 protein using a replication-defective adenovirus vector. Adenovirus AdGFP, expressing GFP, was used as a control. HFF cells were transduced with 20 PFU/cell of either AdGFP or AdIE38 along with 20 PFU/cell AdTrans as described in Materials and Methods. Approximately 100% of the cells were GFP positive 1 day after transduction, at which time the cells were infected with HCMV Towne strain at an MOI of either 0.05 (Fig. 5 A) or 2 (Fig. 5B). The cells were harvested at 1, 2, and 3 days p.i. and subjected to Western blot analysis as described in Materials and Methods. The IE1-p38 protein was readily detected at 1 to 3 days p.i. with HCMV in AdIE38 transduced cells. Whether at low or high MOIs, IE1-p72 and IE2-p86 proteins were detected at the same relative amount for AdGFP- and AdIE38-transduced cells (Fig. 5A and B). In addition, early viral protein p52 (UL44) and late viral protein pp28 (UL99) were expressed at the same relative amount. Thus, the preexpressed IE1-p38 protein did not suppress the expression of the viral proteins at various times after infection at low or high MOIs.

FIG. 5.

IE1-p38 protein does not suppress HCMV viral protein expression. HFF cells were transduced with 20 PFU/cell of either AdGFP or AdIE38 in the presence of AdTrans (20 PFU/cell). After 24 h, cells were infected with HCMV Towne strain at an MOI of 0.05 (A) or 2 (B), harvested at the indicated times postinfection, and analyzed by Western blotting for MIE viral proteins IE2-p86, IE1-p72, and IE1-p38, early viral protein UL44 (p52), late viral protein (UL99) pp28, and cellular protein β-tubulin as described in Materials and Methods.

Cells infected with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A can have a round-cell phenotype.

Besides the growth defects, an intriguing phenomenon was seen with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A, but not with the wild type or the revertant. Recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A infection had round-shaped cells at 3 days p.i. (Fig. 6 A). The round-cell phenotype reached peak levels at about 4 to 5 days p.i. (Fig. 6B). Although there were also some isolated round cells with a similar morphological appearance with the wild type and the revertant virus infection, the percentage of these round cells was much lower (Fig. 6B). The mutant virus infection induced the round-cell phenotype with similar kinetics in ihfie1.3 cells (Fig. 6A), which indicated that mutated IE1-p72 is not the cause of the round-cell phenotype.

FIG. 6.

Recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A induces a round-cell phenotype. HFF or ihfie1.3 cells were infected with recombinant viruses IE1 WT, IE1 X412-419A, or IE1 Rev at an MOI of 0.2 and analyzed at 5 days p.i. as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Fluorescence and phase-contrast microscopy; magnification, ×100. Florescence images of ihfie1.3 cells are not shown. (B) Percent round cells in the presence or absence of PFA (200 μg/ml).

To determine whether the round-cell phenotype depended on viral DNA synthesis, cells were infected with wild-type or recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A in the presence or absence of 200 μg/ml of the viral DNA polymerase inhibitor phosphoformic acid (PFA). While the untreated cells infected with mutant virus induced approximately 20% round cells in culture, the PFA treatment caused a 2-fold increase in the number of round cells (Fig. 6B) (for pictures of the cell cultures, see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The same trend was seen with cells infected by wild-type virus and treated with PFA (Fig. 6B). The intensity of virus-induced GFP fluorescence with PFA-treated cell culture was much weaker than that of untreated cells because the copy number of viral genomes was lower due to inhibition of viral DNA synthesis (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). PFA treatment did not directly cause round cells without viral infection (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Therefore, viral DNA replication and late viral gene expression are not required for induction of the round-cell phenotype with mutant recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A; instead, inhibition of viral DNA synthesis increased the incidence of cell rounding.

Round cells after recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A infection have abnormal mitotic figures.

To determine the difference between the cell phenotypes after infection, HFF cells were infected with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A (MOI, 0.2), and round cells were separated from the other virus-infected cells at 5 days p.i. and subjected to DAPI staining (blue) and an immunofluorescence assay with anti-IE1-p72 (IE1) specific antibody (red) as described in Materials and Methods. Two types of nuclei (blue) existed in the pooled round cells; one was oval in shape with intermediate DAPI intensity, and the other was condensed and highly DAPI stained, with some particle-like scatter (Fig. 7 A). The viral IE1 gene product was detected in both types of cells (red), but in cells with condensed nuclei, the IE1 proteins appeared tightly tethered to the condensed cellular chromatin as reported previously (32).

FIG. 7.

Round cells infected with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A have IE1 protein condensed on the chromatin and abnormal mitotic figures. HFF cells were infected with recombinant viruses IE1 WT or IE1 X412-419A at MOI of 0.1 and stained for an immunofluorescence assay with either MIE exon 4-specific antibody 6E1 (red) or DAPI (blue). In addition, round cells were enriched for an apoptotic assay or for mitotic spreads as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Immunofluorescence assay. Arrowheads indicate infected monolayer cells. Arrows indicate round cells; magnification ×400. (B) Genomic DNAs purified from 2 × 106 cells and resolved on a 0.8% agarose gel. The positive control was U937 cells treated with 4 μg/ml of camptothecin for 3 h. (C) Mitotic spreads. (a) Interphase nuclei of mock-infected cells; (b) IE1 WT-infected cells; (c) mitotic nuclei of mock-infected cells; (d to f) IE1 X412-419A-infected round cells. Magnification, ×1,000.

The cell rounding phenotype suggested apoptosis (66). To test for this possibility, round cells were harvested from mutant virus-infected HFF cells at 5 days p.i., and the genomic DNAs were purified from 2 × 106 cells by using an apoptotic DNA ladder kit. The DNAs were fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis as described in Materials and Methods. While the positive control showed the characteristic DNA ladder pattern, the mock-, wild-type virus-, and mutant virus-infected cells exhibited a typical nonapoptotic DNA profile (Fig. 7B). These observations indicated that the round cells were not going through apoptosis.

Since chromatin condensation, nuclear membrane breakdown, and cell rounding are characteristics of cells undergoing mitosis, we asked whether the round cells are in mitotic phase. Rounded cells from IE1 X412-419A-infected HFF cells were pooled and subjected to mitotic spread analysis. The interphase nuclei of mock-infected and wild-type virus-infected cells have the same oval shape, clear edge, and uncondensed chromatin (Fig. 7C, panels a and b), except the nuclei of the infected cells are enlarged, which is typical for HCMV-infected nuclei. Normal mitotic nuclei have well-formed chromatids in pairs, and over 20 such chromosome pairs are found in a cluster (Fig. 7C, panel c). In contrast, chromosomes from round cells were highly condensed without chromatid-like pairs. Instead, the chromosomes were broken into small well-defined particles or fragments scattered in one cluster (Fig. 7C, panels d to f).

The cells infected with IE1 X412-419A were also assayed for DNA damage response markers as previously described (14) and as described in Materials and Methods. The cells were either stained with DAPI to identify cellular DNA (blue) or observed by phase-contrast microscopy. Both methods identified the presence of the rounded cells in the mutant recombinant virus-infected cell culture (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The rounded cells were intensely positive for MIE (IE1/IE2) antigens (green). The IE1 proteins tethered tightly to the condensed cellular chromatin as shown in Fig. 7A and as reported previously (32). The rounded cells were also intensely positive for the DNA damage response markers (red) phospho-H2AX (γ-H2AX) and phospho-RPA (phos-RPA32) (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

Taken together, these data indicate that the round cells after HCMV Towne recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A infection were going through mitosis, albeit with abnormal mitotic figures, and had a DNA damage response.

Round cells are in the G2/M compartment of the cell cycle after infection with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A.

The IE2-p86 protein affects cell cycle progression by arresting cells at the G1/S boundary in p53+/+ cells (60). Since recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A expressed the IE2-p86 protein at a level significantly lower than that for wild-type virus, we determined the effect of the mutant virus infection on cell cycle progression. HFF cells were synchronized at G0/G1 phase by contact inhibition and then infected with recombinant viruses IE1 WT or IE1 X412-419A at an MOI of 1. At 24 h p.i., the cells were harvested and subjected to FACS analysis as described in Materials and Methods. A representative result from three independent experiments is shown in Fig. 8 A. In the presence of 10% serum, mock-infected cells reentered the cell cycle after being released from contact inhibition, and 23% of cells were in S phase by 24 h. In agreement with previous reports, wild-type virus-infected cells were stopped at the G1/S boundary with only 7% MIE-positive cells residing in S phase and 89% of the cells with G0/G1 DNA content. These data indicate that the wild-type virus was able to efficiently prevent cells from advancing into the next phase. In contrast, cells infected with the mutant virus showed less control of cell cycle progression than those infected with the wild-type virus. Approximately 20% of the IE1 X412-419A-infected cells entered S phase, which was a level close to that of the mock-infected cells. To determine the cell cycle compartment of the rounded cells infected with IE1 X412-419A, we enriched for round cells and then analyzed for DNA content by flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods. Since replicated viral DNA adds to the total DNA content (10, 35), confluent HFF cells were infected with IE1 WT or IE1 X412-419A at an MOI of 0.2 and maintained in medium with 200 μg/ml of PFA for 5 days prior to FACS analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Approximately 50% of the round cells infected with the recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A in the presence of PFA were in the G2/M compartment, and approximately 70% were in the G2/M compartment in the absence of PFA (Fig. 8B). These data indicate that the mutation in exon 4, which altered MIE mRNA splicing and gene expression, could not control cell cycle progression efficiently.

FIG. 8.

Cells infected with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A move more into the S phase, and the round cells accumulate in the G2/M compartment of the cell cycle. (A) HFF cells were synchronized by contact inhibition and released to the cell cycle by culturing at a lower density. Cells were infected with recombinant virus IE1 WT or IE1 X412-419A at an MOI of 1. After 24 h, the cells were harvested. (B) Confluent HFF cells were mock infected or infected with recombinant virus IE1 WT or IE1 X412-419A at an MOI of 0.2 in the presence or absence of PFA (200 μg/ml). Monolayer cells or round cells were harvested at 5 days (5d) postinfection. All cells (A and B) were fixed in 70% ethanol, stained with anti-MIE antibody MAB810X and propidium iodide, and then subjected to FACS analysis as described in Materials and Methods. MIE-positive cells were sorted and counted according to DNA content. Cell cycle profiles were analyzed using FlowJo software to determine the percentage of infected cells in each phase of cell cycle for each sample. With the exception of samples for the bottom right panel (w/o PFA), all samples were treated with PFA during infection.

Alternative MIE mRNA splicing causes an increase in cellular cdk-1.

The cdk-1/cyclinB1 complex plays an important role in normal mitosis by its effect on nuclear membrane breakdown, chromatin condensation, and cytoskeleton rearrangement. We determined the relative level of cdk-1 mRNA and protein at various times after infection with wild-type or recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A at an MOI of 0.2. Figure 9 A shows that cdk-1 protein increased in the wild-type virus-infected cells and reached a steady-state level at 2 days p.i. In contrast, recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A increased the level of cdk-1 2-fold above that of the wild type at 4 days p.i. The increase in cdk-1 protein correlated with approximately a 2.5-fold increase in cdk-1 mRNA at 3 days p.i (Fig. 9B). When cdk-1 was immunoprecipitated with anti-cdk-1/cdc2 (Ab1; Calbiochem) and assayed for activity by phosphorylation of histone one (H1) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP as described in Materials and Methods, the level of cdk-1 activity was approximately 2-fold higher with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A at 3 days p.i. (Fig. 9C). The level of IE2-p86 protein was slightly lower for recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A relative to the wild type, as expected (Fig. 9C).

FIG. 9.

cdk-1 accumulates in cells infected with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A. Cells were infected with IE1 WT or IE1 X412-419A at an MOI of 1 and analyzed by Western blotting, quantitative RT-PCR, and cdk-1 enzyme activity as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Western blot of cdk-1 protein in infected cells at various days after infection (dpi). (B) cdk-1 mRNA in infected cells. (C) cdk-1 enzyme activity in anti-cdk-1 immunoprecipitates of cell lysates from infected cells at 2 and 3 days p.i. Western blot of IE1-p72, IE2-p86, cdk-1, and GAPDH proteins in the cell lysates of infected cells at 2 and 3 days p.i. The data in the figures are representative of results of at least two independent experiments.

Finally, we speculated that out-of-control cdk-1 activity may be responsible for the rounded cell phenotype and for the reduced replication efficiency of the mutant recombinant virus. We determined the effect of a selective inhibitor of cdk-1 on recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A. CGP74514A is a selective inhibitor of cdk-1 (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50], 25 nM) and affects other cellular kinases at higher concentrations (IC50, 6 to 125 μM). To avoid the suppressive effect of cdk-1 inhibitor on viral gene expression and viral replication, CGP74514A was added to the cell culture at 48 h p.i. Treatment of infected cells with 1 μM CGP74514A in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or DMSO alone had no effect on wild-type virus or the mutant recombinant virus, but the number of rounded cells was greatly reduced (for pictures of the cell cultures, see Fig. S5A in the supplemental material). In contrast, treatment with 5 μM CGP745114A affected replication of both the wild type and the mutant recombinant virus and reduced the GFP fluorescence (see Fig. S5A and S5B in the supplemental material). These data suggest that the elevated level of cdk-1 is the direct reason for the round-cell phenotype, which is related to the stalled viral replication cycle.

We conclude that altered splicing of the MIE precursor RNA results in a lack of control of the cellular cdk-1 activity. When the level of cdk-1 activity is not controlled, as with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A, there is a higher percentage of cells with the round-cell phenotype.

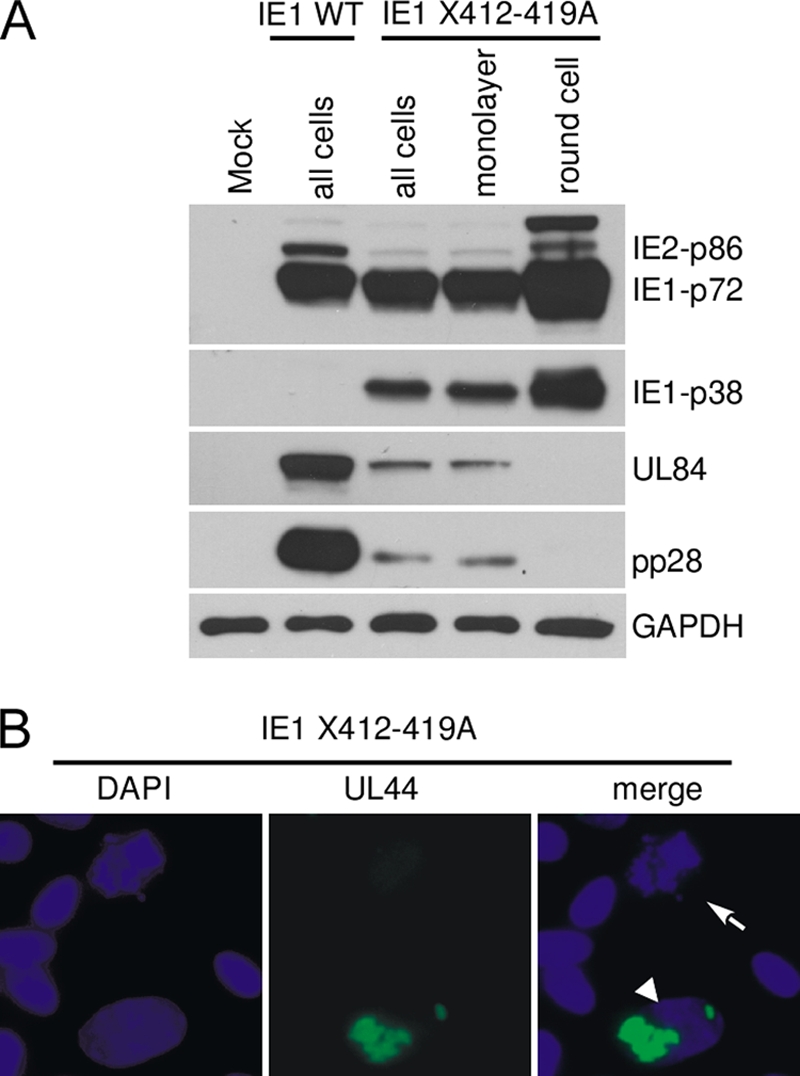

The round cells are an abortive infection.

To determine if both the monolayer cells and the round cells were supportive for virus replication, we infected HFF cells with wild-type virus and recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A at an MOI of 0.1. After 5 days, cells were harvested for either Western blot analysis or an immunofluorescence assay as described in Materials and Methods. The mixture of monolayer cells and round cells (all cells) expressed MIE (IE2-p86, IE1-p72, and IE1-p38), early (UL84), and late (pp28) viral genes but to a lower level than did wild-type virus-infected cells (Fig. 10 A). A similar pattern was seen with the infected monolayer cells. In contrast, only the viral MIE proteins (IE2-p86, IE1-p72, and IE1-p38) were detected in the round cells. Since the MOI was 0.1, not all cells were infected at 5 days p.i., but all the rounded cells were infected, and consequently, there is a higher level of IE1-p72 and IE2-p86 relative to all cells or to the monolayer cells. However, the ratio of IE2-p86 to IE1-p72 is lower in the mutant recombinant virus-infected cells than that in the WT virus-infected cells. In addition, a protein that migrated slower than the IE1-p86 protein was detected by exon 2/3-specific antibody (Fig. 10A) and exon 4-specific antibody (data not shown). We reasoned that this viral protein is sumoylated IE1-p72, according to its apparent molecular weight.

FIG. 10.

Early and late viral proteins were not detected in recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A-infected round cells. (A) HFF cells were infected with recombinant virus IE1 WT or IE1 X412-419A (MOI, 0.1). Cells were harvested or enriched for round cells and analyzed by Western blot assay or by immunofluorescence assay as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Western blot assay for MIE, early (UL84), and late (UL99; pp28) viral proteins. (B) Immunofluorescence assay of recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A-infected cells stained with anti-UL44 (p52) or DAPI. The arrow indicates an infected round cell, while the arrowhead indicates an infected monolayer cell expressing the UL44 gene product. Magnification, ×400.

To further verify the lack of early and late viral gene expression in round cells, we performed an immunofluorescence assay using anti-UL44 antibody. The early viral gene product of UL44 (p52) was easily detected in a typical infected monolayer cell as a focus in the nucleus, which indicated the viral replication center (Fig. 10B, arrowhead). A typical round cell with condensed and fragmented chromatin had no early viral gene product (Fig. 10B, arrow). We conclude that the round cells infected with the mutant virus do not lead to productive viral replication; therefore, the infection is abortive.

DISCUSSION

The MIE locus of HCMV generates a primary transcript that undergoes differential splicing and polyadenylation to produce multiple mRNA species. There are two major gene products, IE1-p72 and IE2-p86, plus multiple isomers expressed at lower levels, which include IE1-p38, IE2-p60, IE2-p55, IE2-p18, and IE2-p40 (reviewed in reference 64). Others have demonstrated that the transcript for IE1-p38 is detectable by both RT-PCR and nuclease protection assays, but the viral protein is not detectable by Western blotting (2, 57). We confirmed the detection of the IE1-p38 transcript by RT-PCR but failed to detect the viral protein by Western blotting of wild-type virus-infected cells. A conserved 24-bp region in exon 4 of the IE1 gene affects the splicing of the precursor RNA. Mutation of this region enhanced splicing of the IE1-p38 transcript and expression of IE1-p38 protein. Although the precise molecular mechanism underlying the control of IE1-p38 mRNA splicing remains to be determined, we speculate that there is an exonic splicing suppressor in the 24-bp region (65, 71). Alternatively, the 24-bp region may form a secondary structure which is unfavorable for the utilization of its adjacent splice site (3, 6). Given that MIE transcripts arise from the same precursor mRNA by differential splicing, an increase of one splice product will result in a reduction in another species. After mutation of the 24-bp region in exon 4, RT-PCR showed that the mRNAs for IE1-p72 and IE2-p86 decreased and IE1-p38 increased relative to the wild-type virus. There was also a decrease in the abundance of the IE1-p72 and IE2-p86 proteins and an increase in IE1-p38 relative to levels for the wild-type virus. The reduced expression of IE1-p72 and IE2-p86 proteins affected the temporal expression of the viral early and late genes and the replication of the virus. In HFF cells, or ihfie1.3 cells infected with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A, lower levels of the IE2-p86 protein were correlated with lower levels of early and late viral gene expression.

There was also an unusual cellular cytopathic effect seen with the recombinant viruses with mutations in the 24-bp region of exon 4. A round-cell phenotype was observed with the mutant recombinant viruses, and this was an intrinsic feature of the mutations introduced into exon 4. Four independent IE1 X412-419A clones all showed the round-cell phenotype, and the rescued virus did not. In addition, recombinant viruses IE1 dl412-419 and IE1 Pu/Py412-419 also showed the round-cell phenotype. The Towne mutant virus IE1 X412-419A constructed by the pRspl-neo selection and counter-selection method, which removes selection markers and leaves only the mutated viral DNA sequence, had the same round-cell phenotype. Introduction of the same mutation into HCMV AD169 (ATCC VR-538) also resulted in the same phenotype (data not shown).

Although abnormal mitotic figures and morphological features of round cells have some similarities to those of “pseudomitotic cells” described recently (21, 22), the round-cell phenotype seen with the mutant viruses in this report was dependent upon alteration of the splicing of the MIE genes and independent of viral DNA synthesis. The mutation in exon 4, which altered the splicing and expression of MIE genes, caused a slight reduction in the level of IE1-p72 protein and a significant reduction in the IE2-p86 protein level. Because both IE1-p72 and IE2-p86 proteins activate early viral gene expression, it is conceivable that optimal ratios of MIE gene expression are necessary for the virus to efficiently execute the viral replication program. Once the balance of MIE gene expression was altered (as happened in IE1 412-419 mutants), the temporal expression of the viral genes failed to execute efficiently in some cells and viral replication was halted. There was a mixture of cells productively infected and abortively infected. The cells with the round-cell phenotype were abortively infected, and viral early and late proteins were not detected.

Altered MIE gene expression does not always lead to the round-cell phenotype. The round-cell phenotype was not reported for the IE1-p72 null virus or for other IE1 mutant viruses (17, 21). Quantitative changes in the relative amounts of IE2-p86 protein have been induced by treatment with Cox-2 (72), mutation of IE2-p86 protein (52, 67), treatment with small interfering RNA (siRNA) to the IE2-p86 transcript (69), or a Cdk inhibitor (53). Lower levels of the early and late viral gene expression were detected relative to the wild type or untreated controls, but the round-cell phenotype was not reported. A reasonable explanation for these differences is that the IE2-p72 or IE1-p86 protein was either mutated (23, 52, 67) or depleted significantly (17, 69) or was overexpressed in the presence of a drug (53). The IE2-p86 protein in this report has all the properties reported for the wild-type protein, but the viral protein level and the timing and balance of gene expression were significantly altered. This replication defect could be corrected in the presence of the IE1 X412-419A mutation by mutating the upstream 3′ splice site in exon 4, which returns the recombinant virus to the wild-type phenotype (Fig. 2 and 3).

For our experiments, more than 90% of the cells were in the G0/G1 compartment of the cell cycle and more than 20% of the infected cells had the round-cell phenotype; therefore, it is unlikely that the cell cycle compartment prior to infection determined the round-cell phenotype. The round cells were predominantly in the G2/M compartment of the cell cycle with abnormal mitotic figures, including chromatin condensation and fragmentation and evidence for a DNA damage response. Treatment with PFA increased the formation of round cells, and early and late viral gene products were not detected in round cells. The preexpressed IE1-p38 protein did not cause round cells alone or in combination with virus infection. Our results do not rule out the possibility that IE1-p38 protein affects cells in a context-dependent manner. Taken together, these results suggested that cellular gene products are responsible for the rounded cell phenotype. Mutant recombinant virus-infected cells that progressed into the S phase had a significant increase in cdk-1 activity and accumulated in the G2/M compartment of the cell cycle.

The IE2-p86 protein is critical in controlling the cell cycle. We reported that a single amino acid mutation at amino acid 548 of the IE2-p86 protein, from a glutamine to an arginine, interfered with the ability of the recombinant virus to stop cell cycle progression at the G1/S boundary relative to results seen with the wild-type virus or with a mutation from glutamine to alanine (47). These recombinant virus-infected cells allowed for cellular DNA synthesis, but infectious-virus production was significantly reduced. On the other hand, the quantity of IE2-p86 protein is also important for the full function of this essential protein, which has been overlooked in the past. In agreement with the dependence of cell cycle control on the quantity of IE2-p86 protein, we noticed a rough dose-effect relationship between the relative amount of IE2-p86 protein and the percentage of cells arrested in the G0/G1 phase after infection with the mutant recombinant viruses. In this study, the IE2-p86 protein was unchanged, but the expression level was reduced in mutant viruses. It is likely that insufficient IE2-p86 protein failed to stop cell cycle progression efficiently, which resulted in cells moving into the S phase and accumulating in the G2/M compartment of the cell cycle with high levels of cdk-1 activity.

The observed higher level of cdk-1 expression and enzymatic activity with recombinant virus IE1 X412-419A supports the hypothesis that elevated cdk-1 activity caused the round-cell phenotype. cdk-1 is a typical E2F-responsive gene, and HCMV infection can upregulate its expression (5, 60). Viral proteins pp71, UL97, and IE2-p86 were all found to be able to stimulate E2F-responsive gene expression (24, 29, 60). Cells were infected with the wild type and IE1 X412-419A had similar levels of viral tegument proteins, but the level of immediate-early protein IE2-p86 was significantly lower with the mutant virus. It is conceivable that IE1 X412-419A virus infection should lead to lower expression of cdk-1, which is in contrast to the higher level of cdk-1 observed for mutant virus infection. A possible explanation is that the lower level of IE2-p86 protein failed to stop the cell cycle at G1/S phase, which led to cell accumulation in G2/M phase with higher levels of cdk-1 activity. The viral DNA synthesis inhibitor increased round-cell formation, which suggested that one or more viral genes expressed delayed early, such as early viral protein pUL117 (50), are involved in controlling the cell cycle progression. While the MIE gene products were detected in the round cell, early and late viral proteins were not detected.

Taken together, the data on the unique phenotype of IE1 412-419 mutant viruses demonstrated the importance of timing and the level of IE1-p72 and IE2-p86 expression on control of cellular gene expression and early and late viral gene expression. Selective splicing to make IE1-p38 caused significantly lower levels of IE2-p86 and resulted in an abortive infection with cells accumulating into the G2/M compartment of the cell cycle. Whether selective splicing to make IE1-p38 RNA and subsequent lowering of the IE2-p86 protein level occur more frequently in some cell types infected with HCMV remains to be investigated. A lowering of the IE2-p86 protein level due to alternative splicing may favor persistent or abortive infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Stinski laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Edward Mocarski for ihfie1.3 cells.

This work was supported by grant AI-13562 from the National Institutes of Health (to M.F.S.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 November 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, J. H., E. J. Brignole III, and G. S. Hayward. 1998. Disruption of PML subnuclear domains by the acidic IE1 protein of human cytomegalovirus is mediated through interaction with PML and may modulate a RING finger-dependent cryptic transactivator function of PML. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:4899-4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Awasthi, S., J. A. Isler, and J. C. Alwine. 2004. Analysis of splice variants of the immediate-early 1 region of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 78:8191-8200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balvay, L., D. Libri, and M. Y. Fiszman. 1993. Pre-mRNA secondary structure and the regulation of splicing. Bioessays 15:165-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baracchini, E., E. Glezer, K. Fish, R. M. Stenberg, J. A. Nelson, and P. Ghazal. 1992. An isoform variant of the cytomegalovirus immediate-early auto repressor functions as a transcriptional activator. Virology 188:518-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Browne, E. P., B. Wing, D. Coleman, and T. Shenk. 2001. Altered cellular mRNA levels in human cytomegalovirus-infected fibroblasts: viral block to the accumulation of antiviral mRNAs. J. Virol. 75:12319-12330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buratti, E., and F. E. Baralle. 2004. Influence of RNA secondary structure on the pre-mRNA splicing process. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:10505-10514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castillo, J. P., A. D. Yurochko, and T. F. Kowalik. 2000. Role of human cytomegalovirus immediate-early proteins in cell growth control. J. Virol. 74:8028-8037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caswell, R., C. Hagemeier, C. J. Chiou, G. Hayward, T. Kouzarides, and J. Sinclair. 1993. The human cytomegalovirus 86K immediate early (IE) 2 protein requires the basic region of the TATA-box binding protein (TBP) for binding, and interacts with TBP and transcription factor TFIIB via regions of IE2 required for transcriptional regulation. J. Gen. Virol. 74:2691-2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherrington, J. M., E. L. Khoury, and E. S. Mocarski. 1991. Human cytomegalovirus ie2 negatively regulates alpha gene expression via a short target sequence near the transcription start site. J. Virol. 65:887-896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dittmer, D., and E. S. Mocarski. 1997. Human cytomegalovirus infection inhibits G1/S transition. J. Virol. 71:1629-1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn, W., C. Chou, H. Li, R. Hai, D. Patterson, V. Stolc, H. Zhu, and F. Liu. 2003. Functional profiling of a human cytomegalovirus genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:14223-14228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis, H. M., D. Yu, T. DiTizio, and D. L. Court. 2001. High efficiency mutagenesis, repair, and engineering of chromosomal DNA using single-stranded oligonucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:6742-6746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fortunato, E. A., V. Sanchez, J. Y. Yen, and D. H. Spector. 2002. Infection of cells with human cytomegalovirus during S phase results in a blockade to immediate-early gene expression that can be overcome by inhibition of the proteasome. J. Virol. 76:5369-5379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaspar, M., and T. Shenk. 2006. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits a DNA damage response by mislocalizing checkpoint proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:2821-2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gawn, J. M., and R. F. Greaves. 2002. Absence of IE1 p72 protein function during low-multiplicity infection by human cytomegalovirus results in a broad block to viral delayed-early gene expression. J. Virol. 76:4441-4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graham, F. L., and A. J. van der Eb. 1973. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology 52:456-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greaves, R. F., and E. S. Mocarski. 1998. Defective growth correlates with reduced accumulation of a viral DNA replication protein after low-multiplicity infection by a human cytomegalovirus ie1 mutant. J. Virol. 72:366-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagemeier, C., R. Caswell, G. Hayhurst, J. Sinclair, and T. Kouzarides. 1994. Functional interaction between the HCMV IE2 transactivator and the retinoblastoma protein. EMBO J. 13:2897-2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagemeier, C., S. Walker, R. Caswell, T. Kouzarides, and J. Sinclair. 1992. The human cytomegalovirus 80-kilodalton but not the 72-kilodalton immediate-early protein transactivates heterologous promoters in a TATA box-dependent mechanism and interacts directly with TFIID. J. Virol. 66:4452-4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi, M. L., C. Blankenship, and T. Shenk. 2000. Human cytomegalovirus UL69 protein is required for efficient accumulation of infected cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:2692-2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hertel, L., S. Chou, and E. S. Mocarski. 2007. Viral and cell cycle-regulated kinases in cytomegalovirus-induced pseudomitosis and replication. PLoS Pathog. 3:e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hertel, L., and E. S. Mocarski. 2004. Global analysis of host cell gene expression late during cytomegalovirus infection reveals extensive dysregulation of cell cycle gene expression and induction of pseudomitosis independent of US28 function. J. Virol. 78:11988-12011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huh, Y. H., Y. E. Kim, E. T. Kim, J. J. Park, M. J. Song, H. Zhu, G. S. Hayward, and J. H. Ahn. 2008. Binding STAT2 by the acidic domain of human cytomegalovirus IE1 promotes viral growth and is negatively regulated by SUMO. J. Virol. 82:10444-10454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hume, A. J., J. S. Finkel, J. P. Kamil, D. M. Coen, M. R. Culbertson, and R. F. Kalejta. 2008. Phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein by viral protein with cyclin-dependent kinase function. Science 320:797-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isomura, H., M. F. Stinski, A. Kudoh, T. Daikoku, N. Shirata, and T. Tsurumi. 2005. Two Sp1/Sp3 binding sites in the major immediate-early proximal enhancer of human cytomegalovirus have a significant role in viral replication. J. Virol. 79:9597-9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isomura, H., T. Tsurumi, and M. F. Stinski. 2004. Role of the proximal enhancer of the major immediate-early promoter in human cytomegalovirus replication. J. Virol. 78:12788-12799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jault, F. M., J. M. Jault, F. Ruchti, E. A. Fortunato, C. Clark, J. Corbeil, D. D. Richman, and D. H. Spector. 1995. Cytomegalovirus infection induces high levels of cyclins, phosphorylated Rb, and p53, leading to cell cycle arrest. J. Virol. 69:6697-6704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalejta, R. F., J. T. Bechtel, and T. Shenk. 2003. Human cytomegalovirus pp71 stimulates cell cycle progression by inducing the proteasome-dependent degradation of the retinoblastoma family of tumor suppressors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:1885-1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalejta, R. F., and T. Shenk. 2003. Proteasome-dependent, ubiquitin-independent degradation of the Rb family of tumor suppressors by the human cytomegalovirus pp71 protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:3263-3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kerry, J. A., A. Sehgal, S. W. Barlow, V. J. Cavanaugh, K. Fish, J. A. Nelson, and R. M. Stenberg. 1995. Isolation and characterization of a low-abundance splice variant from the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early gene region. J. Virol. 69:3868-3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korioth, F., G. G. Maul, B. Plachter, T. Stamminger, and J. Frey. 1996. The nuclear domain 10 (ND10) is disrupted by the human cytomegalovirus gene product IE1. Exp. Cell Res. 229:155-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lafemina, R. L., M. C. Pizzorno, J. D. Mosca, and G. S. Hayward. 1989. Expression of the acidic nuclear immediate-early protein (IE1) of human cytomegalovirus in stable cell lines and its preferential association with metaphase chromosomes. Virology 172:584-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lashmit, P. E., C. A. Lundquist, J. L. Meier, and M. F. Stinski. 2004. Cellular repressor inhibits human cytomegalovirus transcription from the UL127 promoter. J. Virol. 78:5113-5123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu, B., T. W. Hermiston, and M. F. Stinski. 1991. A cis-acting element in the major immediate-early (IE) promoter of human cytomegalovirus is required for negative regulation by IE2. J. Virol. 65:897-903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu, M., and T. Shenk. 1996. Human cytomegalovirus infection inhibits cell cycle progression at multiple points, including the transition from G1 to S. J. Virol. 70:8850-8857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lukac, D. M., N. Y. Harel, N. Tanese, and J. C. Alwine. 1997. TAF-like functions of human cytomegalovirus immediate-early proteins. J. Virol. 71:7227-7239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lukac, D. M., J. R. Manuppello, and J. C. Alwine. 1994. Transcriptional activation by the human cytomegalovirus immediate-early proteins: requirements for simple promoter structures and interactions with multiple components of the transcription complex. J. Virol. 68:5184-5193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malone, C. L., D. H. Vesole, and M. F. Stinski. 1990. Transactivation of a human cytomegalovirus early promoter by gene products from the immediate-early gene IE2 and augmentation by IE1: mutational analysis of the viral proteins. J. Virol. 64:1498-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marchini, A., H. Liu, and H. Zhu. 2001. Human cytomegalovirus with IE-2 (UL122) deleted fails to express early lytic genes. J. Virol. 75:1870-1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mocarski, E. S., G. W. Kemble, J. M. Lyle, and R. F. Greaves. 1996. A deletion mutant in the human cytomegalovirus gene encoding IE1(491aa) is replication defective due to a failure in autoregulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:11321-11326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mocarski, E. S., T. Shenk, and R. F. Pass. 2007. Cytomegalovirus. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 42.Murphy, E. A., D. N. Streblow, J. A. Nelson, and M. F. Stinski. 2000. The human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein can block cell cycle progression after inducing transition into the S phase of permissive cells. J. Virol. 74:7108-7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nevels, M., C. Paulus, and T. Shenk. 2004. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early 1 protein facilitates viral replication by antagonizing histone deacetylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:17234-17239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nghiem, P., P. K. Park, Y. Kim, C. Vaziri, and S. L. Schreiber. 2001. ATR inhibition selectively sensitizes G1 checkpoint-deficient cells to lethal premature chromatin condensation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:9092-9097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paulus, C., S. Krauss, and M. Nevels. 2006. A human cytomegalovirus antagonist of type I IFN-dependent signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:3840-3845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petrik, D. T., K. P. Schmitt, and M. F. Stinski. 2007. The autoregulatory and transactivating functions of the human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein use independent mechanisms for promoter binding. J. Virol. 81:5807-5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petrik, D. T., K. P. Schmitt, and M. F. Stinski. 2006. Inhibition of cellular DNA synthesis by the human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein is necessary for efficient virus replication. J. Virol. 80:3872-3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pizzorno, M. C., and G. S. Hayward. 1990. The IE2 gene products of human cytomegalovirus specifically down-regulate expression from the major immediate-early promoter through a target sequence located near the cap site. J. Virol. 64:6154-6165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poma, E. E., T. F. Kowalik, L. Zhu, J. H. Sinclair, and E. S. Huang. 1996. The human cytomegalovirus IE1-72 protein interacts with the cellular p107 protein and relieves p107-mediated transcriptional repression of an E2F-responsive promoter. J. Virol. 70:7867-7877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qian, Z., V. Leung-Pineda, B. Xuan, H. Piwnica-Worms, and D. Yu. 2010. Human cytomegalovirus protein pUL117 targets the mini-chromosome maintenance complex and suppresses cellular DNA synthesis. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reinhardt, J., G. B. Smith, C. T. Himmelheber, J. Azizkhan-Clifford, and E. S. Mocarski. 2005. The carboxyl-terminal region of human cytomegalovirus IE1491aa contains an acidic domain that plays a regulatory role and a chromatin-tethering domain that is dispensable during viral replication. J. Virol. 79:225-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanchez, V., C. L. Clark, J. Y. Yen, R. Dwarakanath, and D. H. Spector. 2002. Viable human cytomegalovirus recombinant virus with an internal deletion of the IE2 86 gene affects late stages of viral replication. J. Virol. 76:2973-2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]