Abstract

Hantaan virus is the prototypic member of the Hantavirus genus within the family Bunyaviridae and is a causative agent of the potentially fatal hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. The Bunyaviridae are a family of negative-sense RNA viruses with three-part segmented genomes. Virions are enveloped and decorated with spikes derived from a pair of glycoproteins (Gn and Gc). Here, we present cryo-electron tomography and single-particle cryo-electron microscopy studies of Hantaan virus virions. We have determined the structure of the tetrameric Gn-Gc spike complex to a resolution of 2.5 nm and show that spikes are ordered in lattices on the virion surface. Large cytoplasmic extensions associated with each Gn-Gc spike also form a lattice on the inner surface of the viral membrane. Rod-shaped ribonucleoprotein complexes are arranged into nearly parallel pairs and triplets within virions. Our results differ from the T=12 icosahedral organization found for some bunyaviruses. However, a comparison of our results with the previous tomographic studies of the nonpathogenic Tula hantavirus indicates a common structural organization for hantaviruses.

Viruses of the Hantavirus genus, within the family Bunyaviridae, can cause serious disease in humans. Hantaviruses are harbored by rodents, distinguishing them from the arthropod-borne viruses within the other genera (Nairo-, Orthobunya-, Phlebo-, and Tospovirus) of the Bunyaviridae family. Hantaviruses can be differentiated on the basis of geographical distribution and disease state. Old World hantaviruses, such as the Hantaan and Seoul viruses, can cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS), whereas New World hantaviruses, like the Andes and Sin Nombre viruses, can cause hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) (12, 18, 22, 24). Mortality rates for HFRS and HPS have exceeded 10% and 60%, respectively, for some outbreaks (12).

All bunyaviruses have a lipid envelope and contain three (S [small], M [medium], and L [large]) negative-sense, single-stranded RNA genomic segments (12, 24). In the case of hantaviruses, these segments encode a total of four proteins. The S segment encodes a nucleocapsid protein (N) that forms ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes with the segmented RNA (25). The M segment encodes a glycoprotein precursor, which is cotranslationally cleaved at a site within a conserved pentapeptide (WAASA) (15). The two cleavage products ultimately mature into the Gn and Gc glycoproteins, which remain associated as a Gn-Gc complex (26). The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is encoded by the L segment (13).

Hantaviruses enter cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis and undergo fusion with endosomes at low pH (11). Pathogenic hantavirus entry (New or Old World) is mediated by the β3 integrins, whereas the entry of nonpathogenic virions involves β1 integrins (6). The precise functional roles of Gn and Gc in receptor binding and fusion are poorly understood. The polymerase and nucleocapsid protein are translated by free ribosomes in the cytoplasm, whereas the Gn-Gc polyprotein is translated by endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated ribosomes (24). It is generally accepted that hantaviruses assemble at the Golgi apparatus and are transported to the cell surface by exocytosis after budding into the Golgi cisternae, though it has been reported that the Sin Nombre virus and Black Canal Creek virus (New World hantaviruses) can assemble at the plasma membrane (7, 21, 27). Because the hantaviruses do not express a matrix protein, the glycoprotein cytoplasmic C-terminal tails would be logical candidates for involvement in virion assembly. Recent evidence indicates that the hantavirus Gn and Gc tails interact with RNP complexes or genomic RNA (3, 8).

The surface glycoproteins of the Rift Valley fever (5) and Uukuniemi (17) phleboviruses are icosahedrally arranged with T=12 quasisymmetry. However, a recent electron tomographic study showed that the nonpathogenic Tula hantavirus lacks icosahedral symmetry but has locally ordered tetrameric spikes (9).

Here, we have used cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) and single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to examine the structure of Hantaan virus, the prototypic species of Hantavirus and a causative agent of HFRS. We show that the rod-shaped RNP structures within virions are arranged into parallel assemblies and that the glycoproteins form a lattice of tetramers on the virion surface. Furthermore, we observe that densities protruding into the virus interior, presumably consisting of the Gn and Gc tails, are found in close proximity to RNP-like densities. A comparison of our results with cryo-ET studies of Tula virus indicates that virions within the Hantavirus genus have a common structural organization, despite differences in disease progression and receptor usage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus purification.

Virus was prepared in a biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) facility as previously described (23). Briefly, Hantaan virus (strain 76-118) was propagated in Vero E6 cells (ATCC; CRL 1586) using Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 100 units/ml 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 μg/ml of penicillin-streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine. Vero E6 cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 and incubated in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for 7 days. Cell culture supernatants were collected and clarified by centrifugation for 30 min at 8,000 rpm in a Sorvall GSA rotor (Sorvall, Newtown, CT). Polyethylene glycol precipitation was accomplished by the addition of polyethylene glycol 6000 (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) to a final concentration of 8% and sodium chloride to a final concentration of 0.5 M. After overnight stirring in a 4°C cold room, precipitates were collected by centrifugation for 30 min at 8,000 rpm in a Sorvall GSA rotor. Pellets were resuspended in TNE buffer (0.01 M Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, and 0.001 M EDTA, pH 7.4) to become 100-fold concentrations, layered onto a 10 to 60% sucrose-TNE gradient, and centrifuged at 40,000 rpm for 2 h in a Beckman SW41 rotor (Beckman Coulter, Cedar Grove, NJ). Fractions were collected and examined for the presence of virions by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a Hantaan virus nucleocapsid protein-specific monoclonal antibody (E-314) (20).

Cryo-EM and single-particle analysis.

Small aliquots (∼3.5 μl) of purified Hantaan virus particles were applied to holey electron microscopy (EM) grids (R 2/2 Quantifoil; Micro Tools GmbH, Jena, Germany) and vitrified in liquid ethane under BSL-3 conditions. Virions were imaged at 300 kV under low-dose conditions with a CM300 field emission gun electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR). After imaging, the virus was deactivated by heating the specimen grid to 100°C for a period of at least 2 h within the vacuum of the microscope. One hundred fifty-two digital micrographs containing ∼1,000 projection images of vitrified virions were recorded on a 4,096- by 4,096-pixel charge-coupled device (CCD) (TVIPS, Gauting, Germany) camera at 55,600× (0.27-nm pixels) over a range of defocus values (typically 2 through 6 μm) at a dose of 10 to 20 electrons/Å2. Pixels were averaged to give an effective pixel size of 0.54 nm for subsequent image processing.

Many of the particles looked circular in projection although somewhat variable in diameter (Fig. 1). Attempts at producing a three-dimensional reconstruction assuming icosahedral symmetry and stringent rejection of particles based on their correlation with the current model did not lead to a result consistent with the visually obvious distribution of spikes on the viral surface in projection images. In view of the apparent absence of a global order of proteins on the viral surface, attention was shifted to examine whether the obvious surface spikes might have local order that could be used to obtain a three-dimensional reconstruction of a group of adjacent spikes.

FIG. 1.

Virion diameter. Histogram showing the diameter ranges from 120 to 155 nm. The distribution is approximately normal with the largest numbers of virions having a diameter of between 130 and 134 nm.

A total of 15,482 “subparticle” images, corresponding to ∼50-nm-diameter portions of the virion surface, were extracted using the EMAN program BOXER and corrected for phase reversals (16). The majority of the subparticle images represented edge-on views of a group of membrane-embedded glycoprotein spikes, though some axial or “en face” subparticle images were included.

Attempts were made to bring the subparticle images into a common frame of reference using EMAN′s refine routine (an iterative projection matching scheme which utilizes class averages) and the program SPIDER (4) (also an iterative projection matching procedure, but one which does not utilize class averages). An initial starting model was generated using the startcsym module in EMAN. Edge views and axial views were sorted into two separate classes and combined to produce a starting model, which roughly resembled the membrane with embedded spikes when viewed edge-on. In order to improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the starting model, high rotational symmetry was imposed about an axis normal to the viral membrane. Thirteenfold symmetry was chosen so that the starting model would not bias the results toward any suspected symmetry. Several cycles of projection matching, class averaging, and three-dimensional reconstruction were carried out without enforcing any symmetry. This process converged toward a map with approximate 2-fold symmetry but showing a nearly 4-fold arrangement of densities, presumed to represent a lattice of glycoprotein ectodomains.

The asymmetric reconstruction process was repeated using a cylindrically symmetrized starting model. This process also converged to a map with similar tetragonal features. A further control was conducted, in which the subparticle images were sorted into two groups and processed independently. From each half-data set, starting models were generated using the startcsym module. Different large rotational symmetries (13-fold and 11-fold) were applied to the different starting models. At the end of several cycles of reconstruction, the two halves of the data converged toward similar maps with a nearly 4-fold arrangement of the glycoprotein ectodomains.

Twofold symmetry was enforced in subsequent cycles of reconstructions. At the end of this process, individual spikes, presumed to be tetrameric complexes of four Gn and Gc glycoprotein ectodomain lobes, could be discerned within the array. The spikes could be recognized because the density connections between the ectodomain lobes within a spike were stronger than those between spikes. Furthermore, each tetrameric spike was associated with an obvious cytoplasmic density.

Given the tetrameric appearance of the Gn-Gc spikes, 4-fold symmetry was enforced during the final cycles of reconstruction about an axis normal to membrane and through the center of a Gn-Gc spike. This single spike was used to redetermine the orientation of each boxed projection for the subsequent refinement cycle by limiting the comparison of the current model and a projection image to an 18-nm-radius sphere around the 4-fold spike. Subparticle images that correlated poorly with the model were rejected. A total of 9,806 subparticle projection images were included in the final 4-fold averaged map. The resolution of the 4-fold averaged spike complex was estimated from the Fourier shell correlation between maps generated from two half-data sets at a 0.5 cutoff.

Molecular mass estimates.

Densities interpreted as the ectodomains and stalk domains were extracted from the 4-fold averaged Hantaan virus spike complex map using Chimera (19). The volume of the extracted density was measured with the map threshold set to 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 standard deviations above the mean density value. Volumes were converted to mass assuming a density of 1.35 g/cm3.

Comparison of Hantaan and Tula virus spike complexes.

The 4-fold averaged Hantaan virus spike complex was low pass filtered to the resolution limit of the Tula virus map (3.6 nm). The map densities were normalized to have the same means and standard deviations and scaled to account for differences in magnification. The handedness of the Hantaan virus Gn-Gc complex map was flipped to match that of the Tula virus result from cryo-ET. The 4-fold averaged Hantaan virus spike complex was brought into register with the averaged Tula hantavirus spike structure (9) by searching for the translations and rotations that maximized the correlation coefficient between the central spike complexes of the two maps. After the alignment process, a difference map was generated by subtracting the Hantaan virus map from the Tula virus map using the proc3d module in EMAN.

Cryo-ET.

Sample grids were prepared in the same manner as those used in single-particle analysis, except that 10-nm bovine serum albumin (BSA)-Au particles (Aurion, Wageningen, Netherlands) were added to the sample solution prior to vitrification. Tilt series images for tomographic reconstructions were typically obtained over a range of −63 to +63° at 1.5° intervals at a magnification of ×35,300 (0.43-nm pixels). The electron dose for each image was either kept constant throughout the tilt series or adjusted in proportion to the effective sample thickness. The total dose for a particular tilt series was kept in the range of 50 to 100 electrons/Å2 as measured on the detector in the absence of a sample. Images were acquired using either 300 kV or 120 kV and a defocus between 5 and 10 μm. Pixels of the tilt series images were averaged to yield a final pixel size of 0.85 nm. Tilt series images were aligned using the colloidal gold particles as fiducial markers and reconstructed using the weighted back-projection method as implemented in the IMOD software package (14). For display purposes, volumes were denoised with a bilateral filter as implemented in EMAN (10). The resolution of tomograms was assessed using the NLOO2D module within the Electra package (2). The in-plane resolution for a particular tomogram was taken as the average in-plane resolution of two virions within the tomogram at a threshold of 0.5.

RESULTS

Cryo-EM of heterogeneous Hantaan virus virions.

The majority of vitrified Hantaan virus virions were round with diameters ranging from 120 to 155 nm (Fig. 1 and 2 A), although about 10% of the particles were elongated. Both round and elongated virions were covered with spikes that were presumably Gn-Gc glycoprotein complexes. The spikes extended ∼10 nm from the virion surface. In some projection images, the spike complexes appeared to be bilobal with an ∼7-nm spacing between lobes. The spike complexes were spaced at ∼14-nm intervals (Fig. 2B). The periphery of the virus had the appearance of a membrane from which the spikes radiated. In the projection images, there were no clearly recognizable RNP segments within the enveloped particles.

FIG. 2.

Cryo-EM projection images. (A) A digital micrograph of several Hantaan virions embedded in vitreous ice. Strong density is black. Bar, 100 nm. (B) The periphery of a Hantaan virus virion with apparently ordered, membrane-embedded spikes. The black asterisks indicate what appears to be a pair of ectodomain density lobes separated by ∼7 nm. The white triangles indicate two adjacent sets of ectodomain lobes, separated by ∼14 nm. Each set of paired lobes likely represents a single Gn-Gc spike complex in projection. The spikes extend ∼10 nm above the membrane. Strong density is black. Bar, 10 nm.

Cryo-ET shows ordered RNP segments.

Tomograms were reconstructed from tilt series images (see Materials and Methods). Unlike the projection images, the three-dimensional tomograms show rod-shaped densities within the virions, which were assumed to be RNP. These roughly parallel rods had a diameter of ∼10 nm and formed pairs, triplets, and possibly higher-order assemblies separated by ∼18 nm (Fig. 3A to D), although occasionally there were also thinner rod-like densities with a narrower spacing (Fig. 3E). The parallel-running rods may represent multiple independent genome segments. One or more of the three RNP segments may have undergone a roughly 180° bend to give the appearance of four or more rod-like structures (Fig. 3A, B, and D). The 5′ and 3′ ends of hantavirus RNP segments are complementary (24) and might bend to form a closed structure. In addition, more than one copy of a specific RNP segment might be present in some virions. The RNP complexes were sometimes located within 5 nm of the viral membrane (Fig. 3F), suggesting that there might be an interaction with the Gn and Gc cytoplasmic tails. Although some RNP segments approached 100 nm in length, it was difficult to determine their exact lengths due to the anisotropic nature of the reconstructions, an artifact which is unavoidable for tomography. Therefore, the S, M, and L genome segments could not be differentiated. The in-plane resolution of the tomograms did not exceed 7.5 nm (see Materials and Methods). This limited resolution of the tomograms did not permit visualization of the ∼7-nm-separated glycoprotein spikes seen in the cryo-EM projection images.

FIG. 3.

Tomographic sections. (A to D) Rod-like densities within the boundaries of the viral membrane are presumed to be RNP complexes. These rods have a diameter of ∼10 nm and cluster into sets of nearly parallel densities with a spacing of ∼18 nm between the rods. (E) Occasionally, thinner rod-like densities with a narrower spacing were seen. (F) White triangles indicate RNP complexes, viewed end-on, located near the viral membrane. The Gn-Gc spikes are indicated by the black triangle. Strong density is black. Bar, 50 nm.

The nearly 4-fold symmetric lattice of Gn-Gc spikes.

The heterogeneous nature of the Hantaan virus virions prevented successful single-particle analysis of whole virions. Yet, given the repetitive nature of the spikes seen in cryo-EM micrographs (Fig. 2B), it seemed likely that local patches of spikes on the virion surface were ordered. Therefore, single-particle analysis was applied using projection images which corresponded to portions of the viral membrane with embedded spikes (see Materials and Methods). A similar approach had been used to analyze the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus prefusion spike (1).

Asymmetric reconstructions converged toward a map with 2-fold symmetry in the direction normal to the viral membrane (Fig. 4 A). Densities presumed to be glycoprotein ectodomain lobes were separated by ∼7 nm. Twofold symmetry was enforced in subsequent reconstructions. The resultant 2-fold averaged map suggested that there are groups of four ectodomain lobes that together make a tetragonal Gn-Gc spike complex (Fig. 4B and 5 A and B). Several such Gn-Gc spike complexes were present in the 2-fold averaged map. Although the distances between lobes within a spike complex and the distances between adjacent lobes from neighboring spike complexes were similar (∼7 nm), the density connections between lobes within a spike were stronger than those between lobes from adjacent spikes. Furthermore, each spike in the array was associated with a density on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane located beneath the center of each tetrameric spike complex (Fig. 5C and D and 6). The ∼7-nm distance between the ectodomain lobes as well as the ∼14-nm distance between the centers of adjacent spike complexes, as measured from the 2-fold averaged map, was consistent with the estimates of inter- and intraspike distances from the projection images.

FIG. 4.

The asymmetric and 2-fold averaged reconstructions. (A) A section through the asymmetric reconstruction generated from Hantaan virus subparticle images. The section is parallel to the plane of the membrane and cuts through densities presumed to be the Gn-Gc ectodomains. The ectodomain lobes form a nearly 4-fold lattice and are separated by ∼7 nm. (B) The section is rendered in the same orientation as that in panel A, illustrating the 2-fold averaged Gn-Gc ectodomains. Strong density is black. Bar, 5 nm.

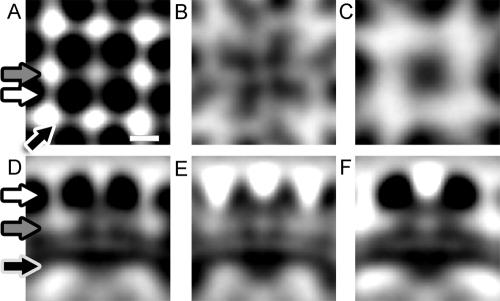

FIG. 5.

Sections from the 2-fold averaged subparticle reconstruction. Left-hand images (A, C, and E) are parallel to the plane of the membrane but are at different heights along an axis perpendicular to the membrane. Right-hand images (B, D, and F) are sections perpendicular to the plane of the membrane. (A) The section cuts through the 2-fold averaged Gn-Gc ectodomains. The white, gray, and black arrows indicate the positions of the planes from which panels B, D, and F are derived, respectively. (B) The section cuts through the center of the ectodomain lobes. Here, the white, gray, and black arrows indicate the positions of the planes from which panels A, C, and E are derived, respectively. (C) The section cuts through the array of Gn-Gc cytoplasmic tail densities located on the inner surface of the viral membrane. (D) The section cuts through the center of two adjacent Gn-Gc spikes. White triangles indicate the location of densities below the center of the Gn-Gc spikes, presumed to be the glycoprotein cytoplasmic tails. (E and F) The sections show density presumed to be an RNP complex (black triangle) in lengthwise (E) and end-on (F) orientations. Strong density is black. Bar, 5 nm.

FIG. 6.

A three-dimensional isosurface rendering of the 2-fold averaged reconstruction. The map was contoured at 1.5σ and tilted to show the cytoplasmic densities. Densities were colored according to radius, so that the Gn-Gc ectodomains are green, the membrane and associated cytoplasmic tails are yellow, and the RNP densities are red. Note that the internal ceiling of the yellow density represents the boundary between the cytoplasmic components of the spikes and the lower-density interior of the virus. Bar, 5 nm.

RNP segments interact with the Gn-Gc cytoplasmic tails.

In the 2-fold single-particle reconstruction, there was an elongated density, running parallel to the viral membrane on the cytoplasmic side of the lipid bilayer (Fig. 5E and F and 6). This density was similar in diameter (∼10 nm) to the RNP segments observed in the cryo-ET results and had lower density than that associated with the glycoprotein and membrane density. The direction of this feature runs diagonally across the tetragonal arrangement of spikes.

The 4-fold averaged Hantaan virus spike complex.

The final map (Fig. 7 and 8) obtained through the alignment and averaging of Hantaan virus subparticle images was 4-fold averaged and determined to a resolution of 2.5 nm (see Materials and Methods). The central spike in the 4-fold reconstructed map consisted of four globular ectodomain lobes, which were tethered to the membrane by four stalk domains. A density on the cytoplasmic side of the viral membrane protruded into the virion and was presumed to arise from the Gn-Gc ctyoplasmic tails.

FIG. 7.

An isosurface rendering of the 4-fold averaged reconstruction. The map was contoured at 1.1σ and is shown down an axis normal to the membrane. The color scheme is the same as in Fig. 6. A system of ridges and valleys at the membrane surface (yellow) was found beneath the four ectodomain lobes (green). The ectodomains of the central spike complex nearly make contact with the neighboring spikes at this contour level. Bar, 5 nm.

FIG. 8.

Sections through the 4-fold averaged reconstruction. (A to C) Sections parallel to the plane of the membrane show the glycoprotein ectodomains (A), ridges on the virion surface in the shape of an X (B), and the Gn-Gc cytoplasmic tails on the inner viral membrane (C). (D to F) Sections normal to the plane of the membrane. The white, gray, and black arrows in panel A indicate the positions of the planes from which panels D, E, and F are derived, respectively. In panel D, the white, gray, and black arrows indicate the positions of the planes from which panels A, B, and C are derived, respectively. Bar, 5 nm. Strong densities are black.

The globular ectodomain lobes had an approximate diameter of 5 nm, and the distance between the center of each lobe and its nearest 4-fold related neighboring lobe was 7 nm (Fig. 8A). At density contours below ∼2σ, the lobes of the tetramer were connected. Connections between ectodomain lobes from neighboring spike complexes existed only at contours less than 0.75σ. The ectodomain lobes extended ∼10 nm above the viral membrane, consistent with observations of the raw projection images. Four vertical stalks connected the membrane-proximal side of each ectodomain lobe to the viral membrane (Fig. 8D to F). The membrane-distal stalk ends did not originate from the centers of the ectodomain lobes but were offset slightly.

The molecular mass of the spike complex ectodomain region, including the four ectodomain lobes and the associated stalks, was estimated (see Materials and Methods) to be 590, 430, and 310 kDa at the 1.0-, 1.5-, and 2.0σ contour levels, respectively. Based on the known sequences and the position within the sequence of the transmembrane regions, the estimated molecular masses of the Gn and Gc ectodomains are 47 and 51 kDa, respectively. Thus, the molecular mass estimates of the spike complex were found to be roughly consistent with a 392-kDa mass corresponding to four copies each of Gn and Gc.

The viral surface, or floor, between the spike complexes was not flat but had a system of ridges and valleys connecting the spikes. The membrane-proximal ends of the stalk domains were connected to a ridge that runs toward a neighboring Gn-Gc complex. The four ridges formed an “X” on the virion surface (Fig. 8B).

On the cytoplasmic side of the viral membrane, a density protruded ∼4 nm into the virion from the center of the Gn-Gc spike (Fig. 8C, E, and F). This protrusion was in close proximity to cytoplasmic density found near the inner leaflet of the lipid bilayer, resulting from averaging the elongated RNP complexes.

The 4-fold averaged spike resembles the Tula virus spike.

The 4-fold averaged Hantaan virus spike complex map resembles the glycoprotein spike structure of Tula hantavirus (9) in that the ectodomain lobes of the two maps are of similar sizes and shapes (Fig. 9 A and B). Furthermore, the ectodomain lobe densities are situated about the 4-fold axis such that distances between the lobes are similar in the two maps. Also, the two maps have similar ridges on the viral surface (Fig. 9E and F), and a cytoplasmic protrusion is seen beneath the center of the 4-fold spike in both maps (Fig. 9G and H).

FIG. 9.

Comparison of the Hantaan and Tula hantavirus spike complex maps. Left-hand images are sections through the 4-fold averaged Hantaan virus spike complex map. Right-hand images are corresponding sections from the Tula virus map. For both maps, positive density is black. All sections are parallel to the plane of the viral membrane but at different levels along an axis perpendicular to the plane of the membrane. (A and B) Ectodomains. The two maps show similar arrangements of the glycoprotein ectodomains. (C and D) Stalks. Each of the four Hantaan ectodomain lobes is tethered to the membrane via a stalk, making a total of four stalk densities. However, the Tula virus spike complex has a single stalk, which is central to the four ectodomain lobes, as well as peripheral stalks which link adjacent spikes. These peripheral stalks are not apparent in the Hantaan virus map. (E and F) Ridges. Ridges form an X on the virion surface, or outer membrane, in both maps. (G and H) Protrusion into virion. In both maps a large cytoplasmic protrusion is seen on the inner surface of the virion, located beneath the center of the four ectodomain lobes.

The central spike complex of the 4-fold averaged Hantaan virus map was aligned to the central spike complex of the Tula virus map (see Materials and Methods). The best alignment of these two spike complexes yielded a correlation coefficient of 0.92. Visual inspection of a difference map generated by subtracting the Tula virus spike complex from the Hantaan virus spike indicated that the most significant negative differences lie in the space between the four lobes at the membrane-distal end of the spike ectodomain. In both maps there is a slight depression or cavity between the four lobes (Fig. 9A and B), but this feature is more pronounced in the Hantaan virus spike complex. The most significant positive differences were found near the periphery of the spike complex ectodomains, indicating that the tetrameric lobes of the Hantaan virus spike ectodomains extended slightly further from the spike center. Furthermore, the Tula virus ectodomain tetramer is connected to the viral membrane via a central stalk (Fig. 9D), centered between the four ectodomain lobes, whereas there are four central stalk densities in the Hantaan virus spike complex (Fig. 9C). These differences suggested that the tetrameric ectodomain lobes of the Tula virus spike complex are more tightly associated than those of the Hantaan virus spike complex.

In the (Hantaan-Tula) difference map, there were negative differences which correspond to the membrane-associated linkages between the Tula virus spike complexes (Fig. 9D) named “peripheral stalks” by Huiskonen et al. (9). In the Tula virus map, these densities appear to cross over the depressions on the virion floor, linking the system of ridges. In similar locations in the Hantaan virus map, the density is near the average value for the map, suggesting that these linkages may be present but at a lower occupancy than those of the Tula virus map.

DISCUSSION

The volume of the Hantaan virus spike was shown to correspond to a molecular mass equivalent to the ectodomains of four Gn and four Gc molecules. These might be organized as two Gn homodimers and two Gc homodimers or as four Gn-Gc heterodimers. The four lobes within a spike appear to be rather similar in shape and size. Thus, these lobes are likely to represent four identical heterodimers as opposed to two different types of homodimers.

Like that of many other enveloped viruses, Hantaan virus entry into cells requires a fusion event triggered by the acidic environment of endosomes (11). All studied viral membrane fusion proteins rearrange from metastable dimers or trimers into a homotrimeric intermediate during the fusion process (28). The present studies of Hantaan virus and the cryo-ET studies of Tula virus (9) have indicated that the Gn and Gc hantaviral glycoproteins form tetramers, likely composed of Gn-Gc heterodimers. How this 4-fold structure could rearrange, allowing the fusogenic component to form a homotrimer, is unclear.

The hantaviral glycoproteins differ significantly in the global organization of their spikes from that of the icosahedral phleboviruses (5, 17), and yet the present results indicate that both the Hantaan virus glycoproteins and RNP are locally ordered. The single-particle approach used in the present study did not indicate the extent of the order in the arrays of spikes, but in any case, a 4-fold lattice could never extend over the whole viral surface without introducing discontinuities in the lattice. Ordering of the Gn-Gc spike complexes into localized arrays appears to be driven by interactions between ectodomain lobes of adjacent spikes as well as by the ridges located on the surface of the viral membrane.

For many enveloped viruses, a matrix protein incorporates the genomic material into virions by linking the envelope to the RNP or capsid. Bunyaviruses encode no matrix protein; however, hantavirus Gn and Gc cytoplasmic tails have been shown to interact with recombinant N protein as well as RNP complexes (8). The Hantaan virus single-particle data show that densities on the inner viral membrane, located directly beneath the Gn-Gc spike, extend toward the virion center. These densities are most likely formed primarily from the predicted ∼110-amino-acid cytoplasmic domain of Gn (8). The cytoplasmic extensions formed arrays on the inner viral membrane and were in juxtaposition with cytoplasmic densities presumed to arise from the presence of RNP complexes near the membrane. Furthermore, the present cryo-ET results showed also that the RNP complexes were often found near the viral membrane. Close packing of the matrix-like arrays of Gn and Gc cytoplasmic tail extensions may be the reason that RNP complexes are incorporated into virions as nearly parallel pairs and triplets, providing the driving force behind virion formation at the Golgi apparatus.

The correlation between the cryo-EM maps representing the tetrameric spikes of Hantaan virus and Tula virus (9) is 0.92, indicating high structural similarity. Although the two results point to similar spike structures, difference maps suggest that the ectodomain lobes within the Tula virus Gn-Gc spike complex are more strongly associated than those of Hantaan virus. These differences could be related to the differences in receptor usage and pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sheryl Kelly for help in the preparation of the manuscript. We also thank Richard J. Kuhn for his role in initiating this work as well as his helpful suggestions throughout the course of this project.

Support for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health/NIAID (R37 AI11219 to M.G.R.) and the National Institutes of Health/General Medicine for the Biophysics training grant (T32 GM008296-20) in support of A.J.B. (C. V. Stauffacher, principal investigator).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beniac, D. R., A. Andonov, E. Grudeski, and T. F. Booth. 2006. Architecture of the SARS coronavirus prefusion spike. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13:751-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardone, G., K. Grünewald, and A. C. Steven. 2005. A resolution criterion for electron tomography based on cross-validation. J. Struct. Biol. 151:117-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Estrada, D. F., D. M. Boudreaux, D. Zhong, S. C. St. Jeor, and R. N. De Guzman. 2009. The hantavirus glycoprotein G1 tail contains dual CCHC-type classical zinc fingers. J. Biol. Chem. 284:8654-8660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank, J., M. Radermacher, P. Penczek, J. Zhu, Y. Li, M. Ladjadj, and A. Leith. 1996. SPIDER and WEB: processing and visualization of images in 3D electron microscopy and related fields. J. Struct. Biol. 116:190-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freiberg, A. N., M. B. Sherman, M. C. Morais, M. R. Holbrook, and S. J. Watowich. 2008. Three-dimensional organization of Rift Valley fever virus revealed by cyroelectron tomography. J. Virol. 82:10341-10348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavrilovskaya, I. N., E. J. Brown, M. H. Ginsberg, and E. R. Mackow. 1999. Cellular entry of hantaviruses which cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome is mediated by b3 integrins. J. Virol. 73:3951-3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldsmith, C. S., L. H. Elliott, C. J. Peters, and S. R. Zaki. 1995. Ultrastructural characteristics of Sin Nombre virus, causative agent of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Arch. Virol. 140:2107-2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hepojoki, J. M., T. Strandin, H. Wang, O. Vapalahti, A. Vaheri, and H. Lankinen. 2010. The cytoplasmic tails of hantavirus glycoproteins interact with the nucleocapsid protein. J. Gen. Virol. 91:2341-2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huiskonen, J. T., J. Hepojoki, Laurinmäki, A. Vaheri, H. Lankinen, S. J. Butcher, and K. Grünewald. 2010. Electron cryotomography of Tula hantavirus suggests a unique assembly paradigm for enveloped viruses. J. Virol. 84:4889-4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang, W., M. L. Baker, Q. Wu, C. Bajaj, and W. Chiu. 2003. Applications of a bilateral denoising filter in biological electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 144:114-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin, M., J. Park, S. Lee, B. Park, J. Shin, K. J. Song, T. I. Ahn, S. Y. Hwang, B. Y. Ahn, and K. Ahn. 2002. Hantaan virus enters cells by clathrin-dependent receptor-mediated endocytosis. Virology 294:60-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonsson, C. B., L. T. Figueiredo, and O. Vapalahti. 2010. A global perspective on hantavirus ecology, epidemiology, and disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23:412-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonsson, C. B., and C. S. Schmaljohn. 2001. Replication of hantaviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 256:13-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kremer, J. R., D. N. Mastronarde, and J. R. McIntosh. 1996. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 116:71-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Löber, C., B. Anheier, S. Lindow, H. D. Klenk, and H. Feldmann. 2001. The Hantaan virus glycoprotein precursor is cleaved at the conserved pentapeptide WAASA. Virology 289:224-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ludtke, S. J., P. R. Baldwin, and W. Chiu. 1999. EMAN: semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J. Struct. Biol. 128:82-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Overby, A. K., R. F. Pettersson, K. Grünewald, and J. T. Huiskonen. 2008. Insights into bunyavirus architecture from electron cryotomography of Uukuniemi virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:2375-2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peters, C. J., and A. S. Khan. 2002. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: the new American hemorrhagic fever. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:1224-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pettersen, E. F., T. D. Goddard, C. C. Huang, G. S. Couch, D. M. Greenblatt, E. C. Meng, and T. E. Ferrin. 2004. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25:1605-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramanathan, H. N., D.-H. Chung, S. J. Plane, E. Sztul, Y.-K. Chu, M. C. Guttieri, M. McDowell, G. Ali, and C. B. Jonsson. 2007. Dynein-dependent transport of the Hantaan virus nucleocapsid protein to the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi intermediate compartment. J. Virol. 81:8634-8647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ravkov, E. V., S. T. Nichol, and R. W. Compans. 1997. Polarized entry and release in epithelial cells of Black Creek Canal virus, a New World hantavirus. J. Virol. 71:1147-1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmaljohn, C., and B. Hjelle. 1997. Hantaviruses: a global disease problem. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:95-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmaljohn, C. S., S. E. Hasty, S. A. Harrison, and J. M. Dalrymple. 1983. Characterization of Hantaan virions, the prototype virus of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. J. Infect. Dis. 148:1005-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmaljohn, C. S., and S. T. Nichol. 2007. Bunyaviridae, p. 1741-1790. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- 25.Severson, W., L. Partin, C. S. Schmaljohn, and C. B. Jonsson. 1999. Characterization of the Hantaan nucleocapsid protein-ribonucleic acid interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33732-33739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spiropoulou, C. F. 2001. Hantavirus maturation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 256:33-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spiropoulou, C. F., C. S. Goldsmith, T. R. Shoemaker, C. J. Peters, and R. W. Compans. 2003. Sin Nombre virus glycoprotein trafficking. Virology 308:48-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White, J. M., S. E. Delos, M. Brecher, and K. Schornberg. 2008. Structures and mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins: multiple variations on a common theme. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43:189-219. (Erratum, 43:287-288.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]