Abstract

Although homeless youth with and without foster care histories both face adverse life circumstances, little is known about how these two groups compare in terms of their early histories and whether they face similar outcomes. As such, we compared those with and without a history of foster care placement to determine if the associations between a history of poor parenting and negative outcomes including depression, delinquency, physical and sexual victimization, and substance use, are similar for these two groups. The sample consisted of 172 homeless young adults from the Midwestern United States. Multivariate results revealed that among those previously in foster care, a history of physical abuse and neglect were positively associated with more depressive symptoms whereas sexual abuse and neglect were related to delinquency and physical victimization. Additionally, lower caretaker monitoring was linked to greater delinquent participation. Among those without a history of foster care, physical abuse was related to more depressive symptoms whereas sexual abuse was positively correlated with delinquency, sexual victimization, and substance use. Furthermore, lower monitoring was related to more substance use. Our findings are discussed in terms of a social stress framework and we review the implications of foster care placement for homeless young adults.

Keywords: Foster care placement, Homeless young adults, Abuse histories, Negative outcomes

Introduction

There are more than half a million American youth currently in foster homes due to child abuse and neglect (US Department of Health & Human Services 2008). Abuse does not always cease once youth are removed from their homes as many continue to experience child maltreatment while in foster care (Courtney et al. 2001; Courtney and Terao 2005). Additionally, numerous children in foster care have developmental and mental health problems (Garland et al. 2000), and many previously in foster care encounter difficulties after they leave care including drug use, homelessness, victimization, and/or arrests (Courtney et al. 2001; Courtney and Terao 2005; Marx et al. 2003; Vaughn et al. 2007).

Another large group of young people who often leave home to escape family conflict, abuse, and/or ineffective parenting is homeless youth (Kaufman and Spatz Widom 1999; Tyler et al. 2000; Whitbeck and Hoyt 1999): approximately 1.6 million American youth ages 12–17 ran away from home and slept on the street during 2002 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) 2004). These young people are also at risk for the same types of negative outcomes as their foster care counterparts. For example, research finds that numerous homeless young people experience involvement in delinquency, physical and sexual victimization, and/or substance use after leaving home (Chen et al. 2004; McMorris et al. 2002). Previous foster care experiences are also common among homeless individuals: homeless adults have rates of out-of-home placement five to seven times higher than the general population (Koegel et al. 1995).

Although both those formerly in foster care but now on the streets and homeless youth have faced adverse life circumstances, little is known about how these two groups compare with one another in terms of their early family histories and whether their outcomes are similar. As such, the purpose of our study is to determine whether homeless young adults with a history of foster care placement significantly differ from those without such a history in terms of poor parenting and depression, delinquency, physical and sexual victimization, and substance use.

There are three possible scenarios that may account for the differences or similarities among former foster and non-foster care homeless young adults. First, the early experiences of homeless adolescents formerly in foster care will be more detrimental and put them at higher risk for negative outcomes because these individuals experienced such extreme forms of abuse that they came to the attention of state authorities. Second, because these adolescents were removed from their homes and placed in alternative care, they are likely to fare better and receive appropriate services and treatment compared to those who are not removed. Third, these groups are not significantly different from one another because they both come from unfavorable backgrounds and are thus likely to have similar early experiences and outcomes. Although all three of these are plausible outcomes, we believe that the third scenario is a better description of the circumstances encountered by these two groups. Previous research has compared foster care to non-foster care youth; however, there is little research on youth who are in similar social circumstances but have unique pathways to the street. The stressors associated with disadvantaged social status create pressures toward engaging in negative behavior (e.g., delinquency) and thus it is important to learn more about these two groups as these findings may have service implications.

Our study is guided by a social stress framework, which is useful for understanding the process that links numerous stressors experienced by many homeless young people with negative outcomes such as substance use and depression. Stressors, according to Wheaton, are “conditions of threats, demands or structural constraints that by their very occurrence or existence, call into question the operating integrity of the organism” (1999, p. 177). Although a majority of people adapt to stress, those with unique social circumstances such as those with foster care histories and homeless individuals may experience more negative outcomes compared with the general population due to the additional stressors associated with their social situation.

The location of individuals within the social system influences their chances of encountering stressors, increasing the likelihood of them becoming emotionally distraught (Aneshensel 1992). In other words, stressors tend to vary according to one’s position in society and thus their impact on negative health outcomes, such as depression, are likely to differ across social conditions. Foster care placement is a unique social circumstance rife with individual level stressors that may be important in understanding the prevalence of depression and other negative outcomes.

Although males and females tend to be equally represented in foster care, racial and ethnic minorities tend to be overrepresented (US Department of Health and Human Services 2008), which may be accounted for by the lack of available services in their community. For example, one study found that although African American families were rated at lower risk than Anglo families, children were more likely to be removed from Black families if the problems found required immediate action and no services were available in their community (Rivaux et al. 2008). Others report that this over representation is likely due to institutional discrimination and the way service agencies view maltreatment within the homes of minority families (Lau et al. 2003).

Many foster youth have experienced abuse and/or neglect in their family of origin or while in foster care or both (Benedict et al. 1994; Clausen et al. 1998; Poertner et al. 1999; Thompson et al. 1994). For example, Lau et al. (2003) in their study of high risk youth in the public sector of care found that more than one half of respondents reported at least one type of moderate abuse. Some also have “unsuccessful” exits from care including running away from placement, incarceration, and psychiatric hospital placement (Courtney and Barth 1996). Because of a lack of services, individuals emancipated from the foster care system may find themselves ill equipped for their emergence into society and some may become homeless within the first year after being discharged (Pecora et al. 2003).

Foster care youth are also much more likely to experience negative outcomes (Taussig 2002; Unrau and Grinnell 2005; Vaughn et al. 2007). A recent study using a nationally representative sample of adolescents aged 12–17 years found that those with a history of foster care were more likely to use alcohol and illicit drugs and to have other substance use disorders compared to those not previously in foster care (Pilowsky and Wu 2006). Furthermore, a family history of substance use or treatment was found to be associated with current substance use among older youth in foster care (Vaughn et al. 2007). Finally, those formerly in foster care were more likely to be involved in more serious delinquency such as theft and serious fighting compared to non-foster care youth (Courtney and Terao 2005).

The daily struggles that homeless individuals experience such as finding food makes the situation of homelessness another unique social circumstance. Homeless youth encounter a variety of stressors, such as housing instability, negative caretaker interactions, and child maltreatment (Anooshian 2005; Tyler 2006; Tyler and Cauce 2002). For example, those who have run away from home multiple times and/or have experiences living in foster care are at higher risk for sexual victimization and other negative outcomes (Tyler 2006; Tyler et al. 2001). Additionally, the caretakers of homeless youth tend to have high rates of substance use and low rates of monitoring (Whitbeck and Hoyt 1999) which have been linked to risky outcomes among homeless youth including alcohol use and delinquent activity (McMorris et al. 2002). Finally, experiencing child abuse is also common among the homeless (Tyler and Cauce 2002; Whitbeck and Hoyt 1999) and is associated with delinquency, substance use (Chen et al. 2004; McMorris et al. 2002; Tyler and Johnson 2006), and physical and/or sexual victimization (Tyler et al. 2000).

Homeless individuals may engage in negative behaviors because they lack adaptive alternatives. As such, the unique stressors experienced by homeless youth may impact their propensity for negative outcomes. In sum, foster care histories and homelessness are markers of social placement (Aneshensel et al. 1991) that may affect the way in which lived reality is experienced, impacting both the stressors encountered (e.g., victimization) as well as the mechanisms mobilized to deal with stress (e.g., substance use).

Method

Participants and Data Collection

Data are from the Homeless Young Adult Project (HYAP), a pilot study designed to examine the effect of neglect and abuse histories on homeless young adults’ mental health and high-risk behaviors. From April of 2004 through June of 2005, 199 young adults were interviewed in three Midwestern cities. Of this total, 144 were homeless and 55 were currently housed at the time of the interview. We defined homeless as those currently residing in a shelter, on the street, or those living independently (e.g., with friends) because they had run away, had been pushed out, or had drifted out of their family of origin. The 55 young adults were chosen via peer nominations from their homeless counterparts. Despite being housed at the time of the interview, 28 out of the 55 housed young adults had extensive histories of being homeless and had run away from home numerous times. Our final sample used for this research included 172 young adults who were homeless or had a history of running away and being homeless.

Experienced interviewers who have served for several years in agencies and shelters that support homeless young people and are knowledgeable about local street cultures (e.g., where to locate youth) conducted the interviews. All interviewers completed the Collaborative Institutional Review Board (IRB) Training Initiative course for the protection of human participants in research. Interviewers obtained informed consent from young adults prior to participation, told them about the confidentiality of the study, and informed them that their participation was voluntary. The interviews lasted approximately 1 h and all participants received $25 for their involvement. Referrals for shelter, counseling services, and food services were offered to the young adults at the time of the interview. Although interviewers did not formally tally screening rates, they reported that very few young adults refused to participate. The IRB at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln approved this study.

Measures

Demographic Control Variables

Foster care was defined as those who had been placed within the foster care system at least one time and was coded 0 = never lived in foster care and 1 = placed in foster care at least once. Gender was coded 0 = male and 1 = female. Race was coded 0 = non-White and 1 = White. Number of times run was a continuous measure that ranged from 1 = once to 6 = 21 or more times.

Early Family History Variables

Sexual abuse was measured using seven items (adapted from Whitbeck and Simons 1990). Young people were asked, for example, “Before you were on your own (when you were under 18), how often has any adult or someone at least 5 years older than you touched you sexually, like on your butt, thigh, breast or genitals (‘private parts’)?” Due to skew, the final variable was dichotomized into 0 = no sexual abuse and 1 = experienced sexual abuse at least one time. Physical abuse was measured with the Conflict Tactics Scale–Parent Child (CTSPC) (Straus, Hamby et al. 1998). Respondents were asked how many times their caretaker had engaged in a variety of abusive actions towards them before they were 18 years old (e.g., slapping them, kicking them, and assaulting them with a knife or gun). Cronbach’s alpha was .88. Due to skew, the 16 individual items were first dichotomized (0 = never and 1 = at least once) and then summed with a higher score indicating more physical abuse. Neglect was comprised of five items from a supplementary scale within the CTSPC (Straus et al. 1998). For example, respondents were asked how many times their caretaker left them home alone when someone should have been with them. Cronbach’s alpha was .82. Due to skew, the individual items were first dichotomized (0 = never and 1 = at least once) and then summed with a higher score indicating more neglect. Monitoring was measured using nine items. Respondents were asked, for example, whether their caretaker knew the parents of their friends and where they were after school. Response categories included 0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = most of the time, and 4 = always. These items were summed together and the scale ranged from 0 to 36. Cronbach’s alpha was .88. Caretaker substance misuse was measured using six items. Respondents were asked for example if they had ever thought their caretaker had a drinking problem and if they ever argued or fought with their caretaker when he/she was high (0 = no, 1 = yes). A summed scale was created (range 0 to 6). Cronbach’s alpha was .87.

Outcome Variables

Depressive symptoms consisted of 10 items from a short form of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff 1977). Respondents were asked, for example, how many days in the previous week they were bothered by things that do not usually bother them. Responses ranged from 0 = rarely or none of the time (< 1 day) to 3 = most or all of the time (5–7 days). Certain items were reverse coded and then summed so that higher scores indicated more depressive symptoms (α = .80). The scale ranged from 1 to 28.

Delinquency was measured with 14 items. Respondents were asked how often they had engaged in a series of delinquent behaviors including theft, fraud, and violence (adapted from Whitbeck and Simons 1990). Alpha reliability was .88. Due to skew, the items were dichotomized and an index was created where higher scores indicated greater delinquency.

Physical victimization was measured with six items that asked respondents, for example, how many times they had something stolen from them, been beaten up, and been robbed. The items were summed with a higher score indicating greater physical victimization. Cronbach’s alpha was .77.

Sexual victimization was comprised of four items that focused on the frequency with which respondents had unwanted sexual experiences since being on their own. Items included, for example, having been touched sexually when they did not want to be and having been sexually assaulted and/or raped. Cronbach’s alpha was .83. Due to skew, each item was dichotomized and then summed to create an index where a higher score indicated more sexual victimization.

Substance use was measured by combining 12 individual variables that asked respondents how often they had drank beer, wine or liquor, had used marijuana, or had used crank, amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, hallucinogens, barbiturates, inhalants, or designer drugs in the past year. Cronbach’s alpha was .78. A mean scale was created (range 0 = never to 4 = daily).

Results

Sample Characteristics

The sample included 69 females (40.1%) and 103 males (59.9%). Ages ranged from 19 to 26 years with a mean of 21.45 years. The majority of the sample was White (80%), 9% were Black or African American, 3.5% Hispanic or Latino, 1.7% American Indian or Alaskan Native, 1.2% Asian and approximately 5% were biracial or multiracial. Almost half of the sample (47%) had experienced sexual abuse, 78% had experienced neglect, and almost all youth had experienced physical abuse (95%). The majority of respondents had run from home one time (46%) but 22% had run 2 or 3 times and 32% had run 4 or more times. A total of 62 youth (36%) had been in foster care at least once.

Procedure

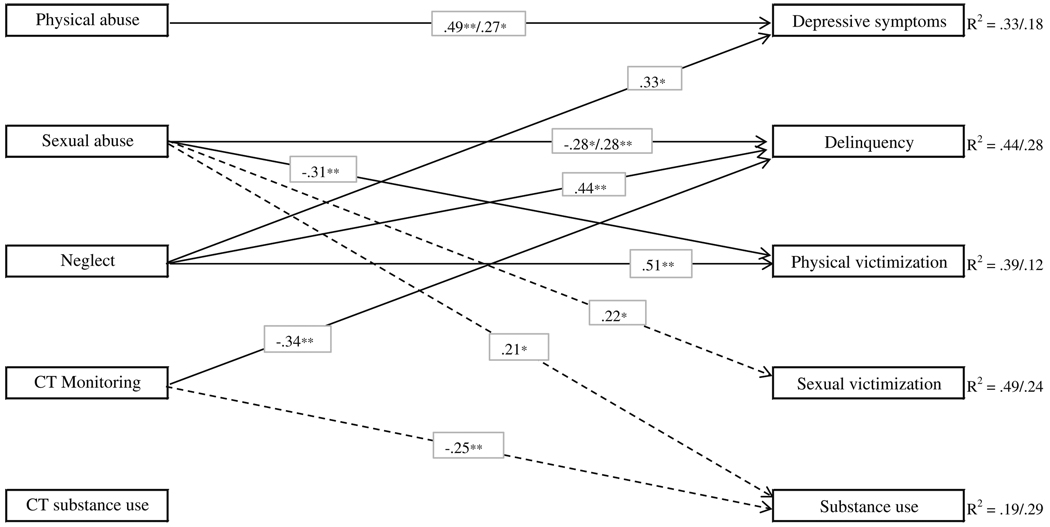

First, we examined whether the two groups of homeless young adults (i.e., those with and without foster care placement) differed in terms of family histories (e.g., sexual and physical abuse). We conducted a series of chi square comparisons to examine the dichotomous variables (see Table 1). Second, we conducted a series of t-test comparisons to compare the two groups on continuous variables (see Table 2). Third, in order to be able to compare two groups simultaneously on the association between early family histories and negative outcomes, we estimated a fully recursive multiple groups path model (see Fig. 1). None of the variables included in the analyses were skewed and multi-collinearity was not an issue as all variance inflation factors were well below five (Menard 1995).

Table 1.

Frequencies and chi square comparisons for foster care vs. non-foster care individuals

| Total N (%) | Foster care N (%) | Non-foster care N (%) | χ2 comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (1 = female) | 69 (40%) | 30 (43.5%) | 39 (56.5%) | 2.761 |

| Race (1 = White) | 137 (79.7%) | 45 (32.8%) | 92 (67.2%) | 2.990+ |

| Sexual abuse ever | 80 (46.5%) | 35 (43.8%) | 45 (56.3%) | 3.456+ |

N = 172.

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10

Table 2.

Mean comparisons of foster care placement vs. non-foster care placement

| Foster care | Non-foster care | T-test comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Means differencea | |

| Number of times run (1–6) | 2.684 | 1.824 | 1.980 | 1.266 | −2.858** |

| Physical abuse (0–15) | 5.316 | 3.334 | 6.216 | 3.497 | 1.582 |

| Neglect (0–5) | 2.228 | 1.637 | 2.000 | 1.735 | −.811 |

| Caretaker monitoring (0–36) | 20.947 | 9.305 | 20.500 | 8.718 | −.303 |

| Caretaker substance use (0–6) | 1.088 | 1.672 | 1.177 | 1.544 | .337 |

| Depressive symptoms (1–28) | 11.842 | 5.678 | 13.088 | 6.907 | 1.160 |

| Delinquency (0–12) | 3.860 | 3.456 | 3.529 | 3.486 | −.575 |

| Physical victimization (0–17) | 6.386 | 4.292 | 5.402 | 3.816 | −1.491 |

| Sexual victimization (0–4) | .807 | 1.172 | .892 | 1.428 | .384 |

| Substance use (0–2.5) | .542 | .506 | .542 | .464 | −.009 |

N = 172.

Difference between foster care placement and non-foster care placement (t-test used)

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10

Fig. 1.

Standardized path coefficients for foster care (n = 110) and non-foster care youth (n = 62). Note: ** p < .01, * p < .05. CT refers to caretaker. The paths for foster care respondents are represented by solid lines; the paths for non-foster care respondents are signified by dashed lines. When two coefficients are provided, the coefficient for foster care is listed first

Chi Square Comparisons

In terms of race, 45 youth (32.8%) who were White compared to 17 youth (48.6%) who were non-White have ever lived in foster care (see Table 1). This difference was significant such that non-Whites were more likely to be represented among foster care youth compared to Whites (χ2 = 2.990). Young adults who reported ever experiencing sexual abuse were significantly more likely to have lived in foster care compared to those without a history of maltreatment (χ2 = 3.456). There was no significant gender difference in terms of foster care placement.

T-Test Comparisons

Results from t-test comparisons shown in Table 2 reveal that the two groups of young adults significantly differed in the number of times they ran away with those previously in foster care running away more often (Mean = 2.684 vs. 1.980). No other differences emerged. That is, these groups of young people did not differ in terms of physical abuse, neglect, parental monitoring, caretaker substance use, or any of the negative outcomes.

Multivariate Analyses

In order to be able to compare two groups simultaneously on the association between family history variables and negative outcomes, we estimated a fully recursive multiple groups path model using the maximum likelihood procedure in Mplus 5.1 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2007). For interpretation purposes, the standardized path coefficients (β) represent the effect of a given predictor variable on the dependent variable after accounting for the remaining relationships in the model. Although ordinary least squares regression would also provide the standardized effect (β), multiple groups models allow us to compare the two groups and estimate all of the paths simultaneously.

Results for the path analysis (only significant paths given) are shown in Fig. 1. The numbers in the figure are standardized beta coefficients. The paths for respondents with a history of foster care placement and non-foster care placement respondents were represented by solid lines and dashed lines, respectively. Among those with a history of foster care placement, higher levels of depressive symptoms was associated with more physical abuse (β = .49) and neglect (β = .33). Additionally, participating in more delinquent activities was related to sexual abuse (β = −.28), more neglect (β = .44), and lower caretaker monitoring (β = −.34) while frequency of physical victimization was positively correlated with sexual abuse (β = −.31) and more neglect (β = .51). In terms of our control variables (results not shown), young adults who had previously run away more often were likely to have experienced greater physical victimization (β = .33). Females and Whites were likely to have experienced more sexual victimization compared to males and non-Whites (β = .51; .32, respectively). While some of these coefficients range from small to moderate (Cohen 1988), they are statistically significant despite a limited sample size and multiple group design. This lends additional credence to our findings.

Among non-foster care respondents (see Fig. 1), those who reported higher levels of depressive symptoms were more likely to have experienced greater physical abuse (β = .27) whereas individuals who participated in a greater number of delinquent acts were more likely to have experienced sexual abuse (β = .28). Additionally, those who reported having experienced greater sexual victimization were more likely to have been a victim of sexual abuse (β = .22). Finally, more substance use among non-foster care young adults was linked to having experienced sexual abuse (β = .21), and lower caretaker monitoring (β = −.25). In terms of our control variables (results not shown), non-Whites were more likely to have experienced higher levels of depressive symptoms compared to their White counterparts (β = −.24). Young people with higher levels of delinquency were more likely to be male (β = −.19), White (β = .17), and to have run away more often (β = .34). Finally, females were more likely to have experienced greater sexual victimization (β = .23), whereas males had higher rates of substance use (β = −.27).

Discussion

We compared those with and without a history of foster care placement to determine if the associations between family histories and negative outcomes are similar for these two groups. Overall, the results indicate that abuse and inadequate parenting are linked to numerous negative outcomes among both groups of young people but the significant paths vary somewhat between groups. For homeless individuals with a history of foster care placement, physical abuse and neglect are correlates of depressive symptoms whereas neglect is also related to more delinquency and physical victimization. Additionally, sexual abuse is negatively associated with delinquency and physical victimization whereas lower monitoring is related to greater involvement in delinquency. Finally, females and Whites are more likely to experience higher levels of sexual victimization whereas running away more often is positively linked to being a victim of physical assault. With the exception of sexual abuse, these results are in the expected direction and are generally consistent with the larger literature on foster care youth (Benedict et al. 1994; Clausen et al. 1998; Courtney and Terao 2005; Poertner et al. 1999; Taussig 2002; Thompson et al. 1994; Unrau and Grinnell 2005; Vaughn et al. 2007).

For the non-foster care group, physical abuse was associated with depressive symptoms and sexual abuse was correlated with delinquency. A history of sexual abuse is a risk factor for both sexual victimization and substance use whereas lower caretaker monitoring is related to more substance use. Non-Whites had higher levels of depressive symptoms but lower rates of delinquency whereas males had more delinquent participation and substance use compared to females. Finally, running away more often is positively related to delinquency whereas being female is related to experiencing greater sexual victimization on the street. These results are also in the expected direction and consistent with the literature on homeless youth (Chen et al. 2004; McMorris et al. 2002; Tyler and Johnson 2006; Tyler et al. 2000). In sum, we hypothesized that there were three possible scenarios that may account for the differences or similarities among these two groups. Our results provide support for scenario three: that is, both groups tend to come from unfavorable backgrounds with similar experiences (i.e., general lack of significance on abuse and poor parenting measures) and have comparable outcomes including depressive symptoms, delinquency, and experiences of either physical or sexual victimization. As such, the effect of foster care placement on the relationship between poor parenting and negative outcomes appears to be similar for these two groups.

According to a social stress framework, stressors tend to vary according to one’s social location and thus their impact on mental health and other negative outcomes are likely to differ across groups; our results indicate that the social circumstance of being homeless trumps foster care placement and thus heightens an individual’s risk of experiencing mental health problems. Because homeless individuals are faced with the stressors associated with their disadvantaged circumstance, many of them engage in negative behaviors such as delinquency because they lack adaptive alternatives. The daily struggles that they experience such as securing a place to stay for the night and finding food makes the situation of homelessness a unique social circumstance. Thus, homeless youth experience similar levels of stress due to meeting their daily survival needs over and above those associated with previously being in the foster care system.

Some limitations should be noted. First, all data are based on self-reports. Despite this, participants were informed that their responses would be confidential and the interviewers were already known and trusted by many of the young people so it is less likely that the respondents would be motivated to bias their responses. Another limitation is the retrospective nature of many of the measures which may have resulted in some over- or underreporting. Third, this study was cross-sectional; therefore, we cannot make inferences about causality. Also, we are unable to distinguish if the abuse occurred in their family of origin, foster care home, or both.

Despite these limitations, this paper also has numerous strengths and contributes to our understanding of similarities and differences among homeless young adults within a social stress context. Although previous research has compared foster care to non-foster care youth, little research exists that compares youth who are in similar social circumstances but have unique pathways to the street. The stressors associated with disadvantaged status create pressures toward negative behavior, such as delinquency. Our study indicates that homelessness is a unique social circumstance and that a history of foster care placement does not contribute additional risk among this population. That is, due to their lack of resources and support, numerous homeless individuals including those with and without a history of foster care may cope with distal and proximal stressors in maladaptive ways.

Our findings have implications for service providers. Although the majority of homeless young adults experience maltreatment, those with foster care histories may be disproportionately represented among this group and the effects of abuse may be long-term. As such, programs may need to specifically target this subgroup of homeless youth to ensure that they are receiving appropriate treatment for their prior abuse experiences. This is especially important given that youth with foster care histories tend to run away multiple times, making them a particularly difficult group to reach. Our findings also indicate that negative outcomes such as depressive symptoms and victimization are similar for both groups of youth indicating that service providers should target all homeless individuals for treatment related to these issues regardless of their prior histories because if left unchecked, they may experience serious negative health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH064897). Dr. Kimberly A. Tyler, PI.

Contributor Information

Kimberly A. Tyler, Department of Sociology, University of Nebraska, 717 Oldfather Hall, Lincoln, NE 68588-0324, USA, kim@ktresearch.net

Lisa A. Melander, Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Social Work, Kansas State University, 204 Waters Hall, Manhattan, KS 66506, USA, lmeland@k-state.edu

References

- Aneshensel CS. Social stress: Theory and research. Annual Review of Sociology. 1992;18:15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Rutter CM, Lachenbruch PA. Social structure, stress, and mental health: Competing conceptual and analytic models. American Sociological Review. 1991;56:166–178. [Google Scholar]

- Anooshian LJ. Violence and aggression in the lives of homeless children: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2005;10:129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict MI, Zuravin S, Brandt D, Abbey H. Types and frequency of child maltreatment by family foster care providers in an urban population. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1994;18:577–585. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Tyler KA, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Early sexual abuse, street adversity, and drug use among female homeless and runaway adolescents in the Midwest. Journal of Drug Issues. 2004;34:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen JM, Landsverk J, Ganger W, Chadwick D, Litrownik A. Mental health problems of children in foster care. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1998;7:283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behaviors sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Barth RP. Pathways of older adolescents out of foster care: Implications for independent living services. Social Work. 1996;41:75–83. doi: 10.1093/sw/41.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Piliavin I, Gorgan-Kaylor A, Nesmith A. Foster youth transitions to adulthood: A longitudinal view of youth leaving care. Child Welfare. 2001;80:685–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Terao S. Emotional and behavioral problems of foster youth: Early findings of a longitudinal study. In: Fitzgerald HE, Zucker R, Freeark K, editors. The crisis in youth mental health: Critical issues and effective programs. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2005. pp. 105–129. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Hough RL, Landsverk JA, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Ganger WC, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in mental health care utilization among children in foster care. Children’s services: Social policy, research, and practice. 2000;3:133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman JG, Spatz Widom C. Childhood victimization, running away, and delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1999;36:347–370. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel P, Melamid E, Burnam MA. Childhood risk factors for homelessness among homeless adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:1642–1649. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.12.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Garland AF, Hough RL, Landsverk J. Race/ethnicity and rates of self-reported maltreatment among high-risk youth in public sectors of care. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8:183–194. doi: 10.1177/1077559503254141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx L, Benoit M, Kamradt B. Foster children in the child welfare system. In: Pumariega AJ, Winters NC, editors. The handbook of child and adolescent systems of care: The new community psychiatry. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McMorris BJ, Tyler KA, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Familial and “on the street” risk factors associated with alcohol use among homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;62:34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard S. Applied logistic regression analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 4th edn. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pecora PJ, Williams J, Kessler RC, Downs AC, O’Brien K, Hiripi E, et al. Assessing the effects of foster care: Early results from the Casey national alumni study. Seattle, WA: Casey Family Programs; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky DJ, Wu LT. Psychiatric symptoms and substance use disorders in a nationally representative sample of American adolescents involved with foster care. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poertner J, Bussey M, Fluke J. How safe are out-of-home placements? Children and Youth Services Review. 1999;21:549–563. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rivaux SL, James J, Wittenstrom K, Baumann D, Sheets J, Henry J, et al. The intersection of race, poverty, and risk: Understanding the decision to provide services to clients and to remove children. Child Welfare. 2008;87:151–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the parent-child conflict tactics scales: Development and psycho-metric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1998;22:249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Substance use among youths who had run away from home. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; The NSDUH Report. 2004

- Taussig HN. Risk behaviors in maltreated youth placed in foster care: A longitudinal study of protective and vulnerability factors. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2002;26:1179–1199. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00391-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RW, Authier K, Ruma P. Behavior problems of sexually abused children in foster care: A preliminary study. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 1994;3:79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA. A qualitative study of early family histories and transitions of homeless youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:1385–1393. doi: 10.1177/0886260506291650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Cauce AM. Perpetrators of early physical and sexual abuse among homeless and runaway adolescents. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2002;26:1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00413-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Hoyt DR, Whitbeck LB. The effects of early sexual abuse on later sexual victimization among female homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15:235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Hoyt DR, Whitbeck LB, Cauce AM. The impact of childhood sexual abuse on later sexual victimization among runaway youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:151–176. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Johnson KA. Pathways in and out of substance use among homeless emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006;21:133–157. [Google Scholar]

- Unrau YA, Grinnell R. Exploring out-of-home placement as a moderator of help- seeking behavior among adolescents who are high risk. Research on Social Work Practice. 2005;15:516–530. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health & Human Services. [Retrieved June 3, 2009];The AFCARS report: Preliminary FY 2006 estimates as of January 2008. 2008 from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/stats_research/afcars/tar/report14.htm.

- Vaughn MG, Ollie MT, McMillen C, Scott L, Jr, Munson M. Substance use and abuse among older youth in foster care. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1929–1935. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B. The nature of stressors. In: Horwitz AV, Scheid TL, editors. A handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 176–197. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. Nowhere to grow: Homeless and runaway adolescents and their families. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Simons RL. Life on the streets: The victimization of runaway and homeless adolescents. Youth & Society. 1990;22:108–125. [Google Scholar]