Abstract

Background

In developed countries, primary health care increasingly involves the care of patients with multiple chronic conditions, referred to as multimorbidity.

Aim

To describe the epidemiology of multimorbidity and relationships between multimorbidity and primary care consultation rates and continuity of care.

Design of study

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Random sample of 99 997 people aged 18 years or over registered with 182 general practices in England contributing data to the General Practice Research Database.

Method

Multimorbidity was defined using two approaches: people with multiple chronic conditions included in the Quality and Outcomes Framework, and people identified using the Johns Hopkins University Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG®) Case-Mix System. The determinants of multimorbidity (age, sex, area deprivation) and relationships with consultation rate and continuity of care were examined using regression models.

Results

Sixteen per cent of patients had more than one chronic condition included in the Quality and Outcomes Framework, but these people accounted for 32% of all consultations. Using the wider ACG list of conditions, 58% of people had multimorbidity and they accounted for 78% of consultations. Multimorbidity was strongly related to age and deprivation. People with multimorbidity had higher consultation rates and less continuity of care compared with people without multimorbidity.

Conclusion

Multimorbidity is common in the population and most consultations in primary care involve people with multimorbidity. These people are less likely to receive continuity of care, although they may be more likely to gain from it.

Keywords: chronic disease, comorbidity, family practice, primary health care, outcome and process assessment (healthcare), prevalence

INTRODUCTION

The practice of medicine is becoming increasingly specialised, both in hospitals and in general practice. For example, many practices now offer chronic disease management clinics for conditions such as diabetes. This approach of treating each condition in isolation has serious limitations. It is important to recognise that many people have multiple coexisting chronic medical conditions, or ‘multimorbidity’.1 People with multimorbidity are likely to have complex needs for health care and to account for a high proportion of the healthcare workload. Increased understanding of the epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity is needed to inform the way in which health care is organised and delivered.

The basis of primary care is that generalists manage all health problems commonly occurring in the population, identifying and referring those problems needing specialist care, and coordinating care for patients with complex health problems.2 However, efforts to improve quality of care have fuelled a move towards specialisation within general practice, and an emphasis on improving access has led to a multiplicity of providers, with patients being less likely to consult the same professional on each occasion.

It is important to consider how the balance should be struck between care provided by professionals with generalist training, able to tackle a wide range of problems at one consultation, or care provided by a wide range of specialists with cross-referral between themselves. This debate needs to be informed by data about the extent and nature of multimorbidity in patients consulting in primary care.

How this fits in.

Several studies have described the prevalence and determinants of multimorbidity, but these have produced varied results. There is little published information on the prevalence of multimorbidity in the UK. Computerisation of general practice records in the UK along with reliable coding of many chronic diseases, due to the Quality and Outcomes Framework, have made it possible to obtain reliable estimates of multimorbidity. This study shows that multimorbidity is very common in the population, particularly in older people and those living in deprived areas. The majority of consultations in general practice involve people with multimorbidity. People with multimorbidity are frequent users of primary care and are less likely to receive continuity of care. These findings support the importance of people having access to a generalist primary care service that is able to coordinate care for a wide range of problems in one individual.

Several studies have examined the prevalence of multimorbidity in different countries. These have reached varied conclusions as a result of differences in setting, the range of health conditions included, and data sources.3–5 Some studies have been based on surveys or administrative data, or have been restricted to older populations.6,7 Most studies based on medical records have involved relatively small numbers of practices and/or patients,3 while larger studies have focused on the determinants and prevalence of multimorbidity,8–12 but few have related this to process or outcome variables in primary care.13,14 Earlier research on multimorbidity has been limited by problems with case definition and with the reliability of data recording within routine practice records.15 There is little information about the epidemiology of multimorbidity in the UK.

The almost universal computerisation of general practice records in the UK over the last 20 years has been accompanied by the development of research databases that combine quality-assured data from a large and representative range of practices. In addition, the introduction of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) has led to the consistent recording of diagnoses of many important chronic health conditions. These factors enable population-based research into multimorbidity. The aims of this study were to gain a detailed and reliable understanding of the epidemiology of multimorbidity in England, and relationships between multimorbidity, consultation rate, and longitudinal continuity in primary care.

METHOD

Sample

This study is based on the anonymised records of a random sample of 99 997 adult patients (aged 18 years or over) from 182 practices in England contributing data to the General Practice Research Database (GPRD). These were all the practices in the GPRD that had provided ‘research standard’ data continuously from 1 April 2005 to 31 March 2008, and had given consent to link their data to measures of area deprivation. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were aged 18 years or over and were registered with one of the participating practices on the index date of 1 April 2005. Sample selection was stratified by practice, age group, and sex. Data were obtained with regard to all diagnoses, consultations, and prescriptions entered until 31 March 2008, including both diagnoses entered contemporaneously and earlier diagnoses that had been entered retrospectively by practices from earlier paper notes.

Defining multimorbidity

Multimorbidity was operationalised in two ways. The primary approach was to define it as a patient who, on the index date, had more than one of 17 important chronic conditions for which care is incentivised under the QOF (Box 1). The QOF business rules16 specify the Read Codes which are used to define each condition. These rules were applied to the diagnostic codes within the GPRD data to determine whether or not individuals had each chronic condition.

Box 1 Chronic conditions included in the Quality and Outcomes Framework and counted within the definition of multimorbidity

Asthma

Atrial fibrillation

Cancer

Coronary heart disease

Chronic kidney disease

Chronic obstructive airways disease

Dementia

Depression

Diabetes

Epilepsy

Heart failure

Hypertension

Learning disability

Mental health problem (psychosis, schizophrenia, or bipolar affective disorder)

Obesity

Stroke

Thyroid disease

As in the QOF itself, patients were included if they had ever had the condition unless there was a code to indicate that it had resolved. The advantage of this approach is that recording of QOF conditions is likely to be reliable and complete, as recording is linked to payments to practices, and case definition is well defined. However, although these 17 conditions include many of the most important chronic conditions, many others are not included (for example, skin disease and liver disease). Therefore, this approach underestimates the true prevalence of multimorbidity.

As a secondary approach, the Johns Hopkins University Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG®) Case-Mix System17 was used to identify whether or not each patient had one or more of a much wider list of chronic conditions. One problem with operationalising multimorbidity based on a count of chronic diseases entered in routine medical records is that the same disease may be coded in different ways and therefore counted twice in the same individual. The ACG system uses a software programme to collapse a wide range of diagnostic codes found within patients' records into 260 mutually exclusive clinically homogeneous ‘expanded diagnostic clusters' (EDCs).

Three investigators, all of whom are GPs, independently assessed whether each of the diagnostic clusters should be included as a chronic condition. Differences were resolved by consensus. A chronic condition was defined as one that normally lasts 6 months or more, including past conditions that require ongoing disease or risk management, important conditions with a significant risk of recurrence, or past conditions that have continuing implications for patient management. In this way, 114 of the 260 diagnostic clusters were defined as chronic conditions (Appendix 1).

The ACG software was used in conjunction with the diagnostic data in the GPRD dataset to determine whether or not each patient had ever been diagnosed with each condition, and an EDC-based chronic condition count per patient was calculated.

Analysis

The prevalence of multimorbidity was estimated in relation to age, sex, and deprivation. Age-standardised prevalence estimates were calculated using the European Standard Population.18 Deprivation was based on Townsend scores derived from the patient's postcode and national quintiles using 2001 census data. Based on previous research, it was anticipated that multimorbidity would show a positive association with age, female sex, and deprivation.3,8,12,19,20

The study sought to investigate associations between multimorbidity, consultation rates, and continuity of care. Consultation rates were calculated over 3 years beginning 1 April 2005, and were based on consultations with GPs or practice nurses, including face-to-face and telephone consultations. Annual rates were calculated, taking account of patients who left the practice or died during the period studied. Using the total number of consultations (rather than the number of patients) as the denominator, the proportion of consultations that involved patients with different levels of multimorbidity was also explored.

Longitudinal continuity of care over 3 years was calculated, making use of the fact that each consultation in the GPRD dataset has identifiers to indicate type of consultation, which clinician conducted it, and that clinician's profession. The usual provider continuity index21 and the continuity of care index22 were calculated. The usual provider continuity index represents the proportion of all consultations with the clinician who had been consulted most often, and the continuity of care index is a measure of the concentration of consultations with different doctors, adjusting for the number of consultations. Face-to-face and telephone consultations with GPs or practice nurses were included in continuity analyses. Patients with fewer than two consultations in the 3-year period were excluded.

Statistical analysis

For both the QOF and the ACG/EDC approaches, all analyses were repeated treating multimorbidity as a binary variable (none or one chronic condition versus more than one) and also as a discrete variable (number of conditions). Descriptive statistics, including 95% confidence intervals, were used to describe relationships between multimorbidity and other variables. Independent relationships between age, sex, deprivation, and multimorbidity when treated as a binary or discrete variable, were examined using logistic and Poisson regressions respectively. Consultation rate data were skewed and were therefore log transformed before being included in multiple linear regression analyses with multimorbidity, age, sex, and deprivation as explanatory variables. Relationships between multimorbidity and continuity of care were similarly examined. All analyses were conducted in Stata (version 11.0). The ‘svy’ survey commands were used throughout to take account of the sampling methods.

RESULTS

Epidemiology of multimorbidity

Initial examination of the patient sample in comparison with census data indicated that it was representative of the population of England in terms of age–sex distribution, although with slightly lower levels of deprivation (mean Townsend score = −1.04).

By the index date, 16% of the sample (16 030/99 997) had been diagnosed with more than one of the conditions included in the QOF, but 58% (58 115/99 997) had been diagnosed with more than one EDC chronic condition. The age-standardised prevalence was 14% using the QOF approach and 56% using the ACG/EDC approach.

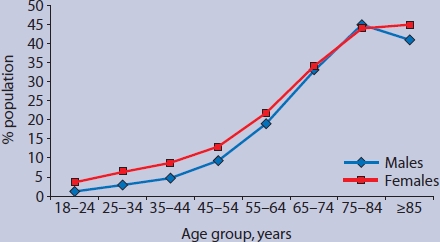

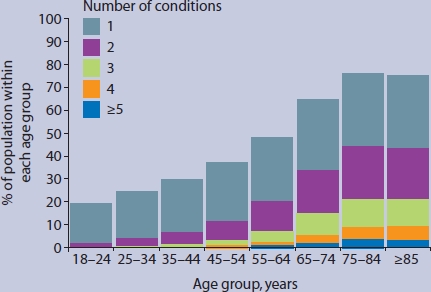

Figure 1 demonstrates that multimorbidity is strongly related to age, and slightly more common in females than males below the age of 65 years. Patients aged 75 years or over had mean = 1.56 (95% CI = 1.52 to 1.59) QOF conditions and mean = 5.63 (95% CI = 5.52 to 5.74) EDC conditions. Figure 2 illustrates that 77% of patients aged 75 years or over had at least one QOF condition, 44% had more than one QOF condition (multimorbidity), and 9% had four or more conditions.

Figure 1.

Percentage of population with more than one chronic condition in the Quality and Outcomes Framework, by age and sex.

Figure 2.

Number of conditions included in the Quality and Outcomes Framework, per patient, by age group.

Table 1 shows that increasing age, female sex, and living in a deprived area were all, as hypothesised, independently associated with increased odds of having multimorbidity. Patients in the most deprived quintile for deprivation were almost twice as likely to have multimorbidity as those in the least deprived quintile (odds ratio 1.91 [95% CI = 1.78 to 2.04] adjusted for age and sex). Similar results were observed with the ACG/EDC approach, although the relationship with deprivation was less marked.

Table 1.

Independent associations between multimorbiditya and age, sex, and deprivation

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10-year increase; range ≥18 years) | 1.78 | 1.76 to 1.81 | <0.001 |

| Sex (reference category: male) | 1.23 | 1.18 to 1.28 | <0.001 |

| Deprivation (per 10-unit increase in Townsend score) | 2.08 | 1.95 to 2.22 | <0.001 |

Multimorbidity is defined as having more than one condition in the Quality and Outcomes Framework. All variables are adjusted for each other. n = 99 624 due to missing deprivation data for 373 individuals.

Multimorbidity and consultation rates

The overall consultation rate was 4.63 (95% CI = 4.58 to 4.69) consultations per patient per annum. Consultation rates showed the anticipated relationships with age, sex, and deprivation, with increasing rates with age, higher consultation rates for females than males among those below the age of 65 years, and higher rates in more deprived areas. Patients with multimorbidity (based on QOF) had 9.35 (95% CI = 9.21 to 9.49) consultations per annum compared with 3.75 (95% CI = 3.71 to 3.80) among those without multimorbidity.

Table 2 shows the independent relationships between consultation rate and age, sex, and deprivation before and after adjusting for multimorbidity. It demonstrates that the relationship between age and consultation rate is reduced, and that between deprivation and consultation rate almost disappears, after adjustment for multimorbidity. This suggests that the main reason that older patients and those in deprived areas consult more often is because they have more chronic health conditions.

Table 2.

Independent relationships between age, sex, deprivation, and consultation rate, before and after adjusting for multimorbidity

| Consultation rate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before adjustment for multimorbidity R2 = 0.19 | After adjustment for multimorbidity R2 = 0.30 | |||||

| Explanatory variable | Coefficient | 95% CI | P-value | Coefficient | 95% CI | P-value |

| Age (per 10-year increase; range ≥18 years) | 0.17 | 0.17 to 0.18 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.09 to 0.10 | <0.001 |

| Sex (reference category: male) | 0.48 | 0.46 to 0.50 | <0.001 | 0.42 | 0.40 to 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Deprivation (per 10-unit increase in Townsend score) | 0.12 | 0.10 to 0.15 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.01 to 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Multimorbidity (number of QOF chronic conditions) | – | – | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.36 to 0.38 | <0.001 |

All variables were adjusted for each other. n = 99 624 due to missing deprivation data for 373 individuals. QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework.

Proportion of consultations involving patients with multimorbidity

Using all consultations between 1 April 2005 and 31 March 2008 as the denominator (n = 1 430 773), rather than the number of patients, the proportion of primary care consultations that involved people with multimorbidity was explored. Although patients with multimorbidity (QOF) represented only 16% of the population, they accounted for 32% of all consultations. Using the ACG/EDC approach, 58% of patients had multimorbidity, and these individuals accounted for 78% of all consultations.

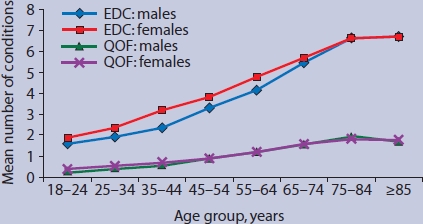

Figure 3 shows the number of different chronic conditions encountered by primary care practitioners in an average consultation, in relation to patients' age. Consultations with patients aged over 75 years involved individuals with mean = 1.86 (95% CI = 1.82 to 1.91) QOF conditions and 6.68 (95% CI = 6.53 to 6.82) EDC conditions.

Figure 3.

Number of chronic conditions in patients consulting, per consultation, by age group. EDC = expanded diagnostic clusters from the Johns Hopkins University Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) Case-Mix System.17 QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework.

Multimorbidity and continuity of care

Levels of longitudinal continuity of care were low for all patients (mean = 0.25 on both indices). QOF multimorbidity was inversely associated with the usual provider continuity index (coefficient −0.08 [95% CI = −0.09 to −0.08] after adjusting for age, sex, and deprivation). The equivalent model using the continuity of care index (which takes account of the number of consultations) showed a much smaller but still inverse relationship between multimorbidity and longitudinal continuity (coefficient = −0.008 [95% CI = −0.011 to −0.004]).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

Most consultations in primary care involve patients with multimorbidity. These people have reduced longitudinal continuity of care, largely because of their high consultation rates. Although multimorbidity is common, the estimated prevalence varies considerably, depending on how it is measured. Prevalence increases with age, but affects patients of all age groups. Multimorbidity is more common among patients living in deprived areas.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This article is based on a larger and more representative sample than earlier studies of the epidemiology of multimorbidity. As almost everyone in the UK is registered with just one general practice, participants are broadly equivalent to a population sample. The introduction of the QOF means that the coding of important diseases is likely to be consistent across participating practices, and the development of case-mix software such as the ACG system overcomes some of the coding problems encountered by previous studies.23 The comprehensive nature of the data recorded with the GPRD makes it possible to explore relationships between multimorbidity and health processes and outcomes. This paper also builds on previous research by highlighting the high proportion of consultations that involve people with multimorbidity, which is important from a health-system perspective.

The study has several limitations. The large sample means that it is important to consider the magnitude of associations rather than P-values. The difference between the findings obtained using the QOF or ACG/EDC approaches illustrates the difficulty of providing precise estimates of the prevalence of multimorbidity, as this depends on the range of conditions included. Because the QOF approach only includes a limited number of conditions, it underestimates prevalence. The ACG/EDC approach includes a comprehensive list of chronic conditions, but in the absence of an internationally recognised list of conditions defined as chronic, the authors had to generate their own, and other investigators may have identified a different list.24 In addition, not all of the ‘chronic’ conditions included may have been active or relevant in a particular patient. The prevalence of multimorbidity should therefore always be stated in relation to the measure used.

Both the QOF and the ACG/EDC approaches represent disease counts, with each disease counted equally. Case-mix adjustment methods that weight diseases differentially to estimate the burden of illness (such as the Charlson index25 or the full ACG system17) are likely to predict outcomes more effectively,1 but, unlike a disease count, they do not provide a direct measure of multimorbidity as usually defined in terms of multiple conditions. Furthermore, this paper is based on a definition of multimorbidity as the coexistence of multiple diseases. This approach provides a limited and medicalised perspective, which may not reflect patients' understanding of their problems.1

Estimates of multimorbidity in this study are based on diagnoses recorded in medical records. Different estimates of prevalence are obtained using different sources of data, such as GP records, patient surveys, or studies involving examination of patient cohorts.5,26 Studies based on medical records will underestimate multimorbidity because some diseases are undiagnosed, and because they will not identify people who do not consult. Conversely, the relationship between multimorbidity and consultation rate has a risk of circularity, in that people who consult more often may have more conditions diagnosed.27

Comparison with existing literature

This study supports previous research with regard to the strong relationships between multimorbidity and increasing age3,8,12 and social disadvantage.8,12,20 Previous studies have examined the relationship between multimorbidity and hospitalisation, but few have explored the relationship with utilisation of primary care, and these studies are not directly comparable.28–30 Apart from a small study in just one practice,31 it was not possible to identify any previous research examining the relationship between multimorbidity and continuity of care.

This paper adds to previous literature because of the size and generalisability of the sample, the reliability of the data sources, and the comparison of different approaches to measuring multimorbidity. It is also the first comprehensive published study of multimorbidity in the UK.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

Most consultations in primary care involve patients with multiple conditions, and these may need to be taken into account when making decisions about patient management. Interactions between the conditions may further complicate decision making.1 Guidelines are available to inform the management of many chronic diseases but these often fail to offer clear guidance about patients with comorbidities.32 Therefore, practitioners working in primary health care need to have a broad knowledge base, be able to coordinate care across a wide range of different specialist services, have excellent communication skills to manage complex consultations in a limited time, and have good judgment to balance competing priorities.

Given that so many patients have multiple chronic conditions, healthcare systems that are based on first-contact specialist care are likely to result in patients having frequent consultations in different locations or with different providers and often seeing practitioners who have to cross-refer to other specialists for advice about comorbidities. Systems that fragment care across multiple primary care providers face challenges in coordinating care for the many patients with multiple problems.

Continuity of care is particularly important to people with multimorbidity,33,34 but this study demonstrates that these people are less likely to receive it. Longitudinal continuity, as measured here, is closely related to relational continuity,34 and although better coordination between providers and shared records may enhance ‘management continuity’ and ‘information continuity’,35 it should not be assumed that these can substitute for the relationship with a particular doctor that many people with multimorbidity value.33,34,36

Multimorbidity should be considered as a possible confounding factor in studies comparing the process or outcomes of care in different settings. Although multimorbidity is very common, it is not known how best to organise health services in order to optimise care for these people. A better understanding of the problems that multimorbidity generates is needed to develop and test interventions to improve care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank members of the multimorbidity theme group within the National School for Primary Care Research for constructive criticism on this research as it was designed and presented.

Appendix 1.

Expanded diagnostic clustersa within the ACG® system, designated by the authors as chronic conditions

| Expanded Diagnostic Cluster code | Label |

| Not an EDC. Itemised separately within the ACG software | Asthma |

| Not an EDC. Itemised separately within the ACG software | Hypertension |

| Not an EDC. Itemised separately within the ACG software | Diabetes |

| Not an EDC. Itemised separately within the ACG software | Arthritis |

| ADM02 | Surgical aftercare (e.g. heart valve replacement, colostomy) |

| ADM03 | Transplant status (e.g. heart transplant, bone marrow transplant) |

| ALL06 | Disorders of the immune system |

| CAR03 | Ischemic heart disease (excluding acute myocardial infarction) |

| CAR04 | Congenital heart disease |

| CAR05 | Congestive heart failure |

| CAR06 | Cardiac valve disorders |

| CAR07 | Cardiomyopathy |

| CAR09 | Cardiac arrhythmia |

| CAR10 | Generalsed atherosclerosis |

| CAR11 | Disorders of lipoid metabolism |

| CAR12 | Acute myocardial infarction |

| CAR16 | Cardiovascular disorders, other (e.g. sub-acute bacterial endocarditis) |

| EAR08 | Deafness, hearing loss |

| END02 | Osteoporosis |

| END04 | Thyroid disease |

| END05 | Other endocrine disorders (including diabetes insipidus) |

| EYE02 | Blindness |

| EYE03 | Retinal disorders (excluding diabetic retinopathy) |

| EYE06 | Cataract, aphakia |

| EYE08 | Glaucoma |

| EYE13 | Diabetic retinopathy |

| FRE03 | Endometriosis |

| FRE12 | Utero-vaginal prolapse |

| GAS02 | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| GAS05 | Chronic liver disease |

| GAS08 | Gastro-oesophageal reflux |

| GAS09 | Irritable bowel syndrome |

| GAS10 | Diverticular disease colon |

| GAS12 | Chronic pancreatitis |

| GAS13 | Lactose intolerance |

| GSU06 | Chronic cystic disease of the breast |

| GSU08 | Varicose veins of lower extremities |

| GSU11 | Peripheral vascular disease |

| GSU13 | Aortic aneurysm |

| GTC01 | Chromosomal anomalies |

| GTC02 | Inherited metabolic disorders |

| GUR01 | Vesicoureteral reflux |

| GUR03 | Hypospadias, other penile anomalies |

| GUR04 | Prostatic hypertrophy |

| GUR09 | Renal calculi |

| GUR10 | Prostatitis |

| HEM01 | Hemolytic anaemia |

| HEM02 | Iron deficiency, other deficiency anaemias |

| HEM05 | Aplastic anaemia |

| HEM03 or HEM 06 | Thromboplebitis and DVT (deep vein thrombosis) |

| HEM07 | Hemophilia, coagulation disorder |

| HEM08 | Hematologic disorders, other (including secondary polycythaemia) |

| INF01 | Tuberculosis |

| INF04 | HIV, AIDS |

| MAL01 | Malignant neoplasms of the skin |

| MAL02 | Low impact malignant neoplasms |

| MAL03 | High impact malignant neoplasms |

| MAL04 | Malignant neoplasms, breast |

| MAL05 | Malignant neoplasms, cervix, uterus |

| MAL06 | Malignant neoplasms, ovary |

| MAL07 | Malignant neoplasms, esophagus |

| MAL08 | Malignant neoplasms, kidney |

| MAL09 | Malignant neoplasms, liver and biliary tract |

| MAL10 | Malignant neoplasms, lung |

| MAL11 | Malignant neoplasms, lymphomas |

| MAL12 | Malignant neoplasms, colorectal |

| MAL13 | Malignant neoplasms, pancreas |

| MAL14 | Malignant neoplasms, prostate |

| MAL15 | Malignant neoplasms, stomach |

| MAL16 | Acute leukemia |

| MAL18 | Malignant neoplasms, bladder |

| MUS06 | Kyphoscoliosis |

| MUS07 | Congenital hip disclocation |

| MUS11 | Congenital anomalies of limbs, hands, and feet |

| MUS13 | Cervical pain syndromes |

| MUS14 | Low back pain |

| NUR03 | Peripheral neuropathy, neuritis |

| NUR05 | Cerebrovascular disease |

| NUR06 | Parkinson's disease |

| NUR07 | Seizure disorder |

| NUR08 | Multiple sclerosis |

| NUR09 | Muscular dystrophy |

| NUR11 | Dementia and delirium |

| NUR12 | Quadriplegia and paraplegia |

| NUR16 | Spinal cord injury/disorders |

| NUR17 | Paralytic syndromes, other |

| NUR18 | Cerebral palsy |

| NUR19 | Developmental disorder |

| NUR21 | Neurologic disorders, other (e.g. Huntingdon's chorea) |

| NUT03 | Obesity |

| PSY01 | Anxiety, neuroses |

| PSY02 | Substance use |

| PSY04 | Behaviour problems |

| PSY05 | Attention deficit disorder |

| PSY07 | Schizophrenia and affective psychosis |

| PSY08 | Personality disorders |

| PSY09 | Depression |

| REC01 | Cleft lip and palate |

| REC03 | Chronic ulcer of the skin |

| REN01 | Chronic renal failure |

| REN04 | Nephritis, nephrosis |

| REN05 | Renal disorders, other |

| RES03 | Cystic fibrosis |

| RES04 | Emphysema, chronic bronchitis, COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) |

| RES06 | Sleep apnea |

| RES08 | Pulmonary embolism |

| RES09 | Tracheostomy |

| RES11 | Respiratory disorders, other (e.g. pneumoconiosis) |

| RHU01 | Autoimmune and connective tissue diseases |

| RHU02 | Gout |

| RHU03 | Arthropathy (e.g. pyogenic arthritis) |

| SKN02 | Dermatitis and eczema |

| SKN12 | Psoriasis |

| SKN13 | Disorders of hair and follicles (e.g. alopecia) |

Details of expanded diagnostic clusters (EDCs) obtained from the Johns Hopkins University Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) Case-Mix System Reference Manual version 7.17 Bloomberg: John Hopkins University, 2005. Copyright, used by permission.

Funding body

This work was undertaken by the authors, who received funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research funding scheme. This report presents independent commissioned research by the National Institute for Health Research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. This study is based in part on data from the Full Feature General Practice Research Database obtained under licence from the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. However the interpretation and conclusions contained in this study are those of the authors alone. Access to the GPRD database was funded through the Medical Research Council's licence agreement with MHRA.

Ethics committee

Studies based on the GPRD are covered by ethics approval granted by Trent Multicentre Research Ethics Committee, reference 05/MRE04/87.

Competing interests

The authors have stated that there are none.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Valderas JM, Starfield B, Sibbald B, et al. Defining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health services. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):357–363. doi: 10.1370/afm.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starfield B. Primary care — balancing health needs, services, and technology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity among adults seen in family practice. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):223–228. doi: 10.1370/afm.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Roos S, Knottnerus JA. Problems in determining occurrence rates of multimorbidity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(7):675–679. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schram MT, Frijters D, van de Lisdonk EH, et al. Setting and registry characteristics affect the prevalence and nature of multimorbidity in the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(11):1104–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman C, Rice D, Sung HY. Persons with chronic conditions. Their prevalence and costs. JAMA. 1996;276(18):1473–1479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starfield B, Lemke KW, Bernhardt T, et al. Comorbidity: implications for the importance of primary care in ‘case’ management. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(1):8–14. doi: 10.1370/afm.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van den Akker M, Buntinz F, Metsemakers JF, et al. Multimorbidity in general practice: prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(5):367–375. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saltman DC, Sayer GP, Whicker SD. Comorbidity in general practice. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81(957):474–480. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.028530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schellevis FG, van der Velden J, van de Lisdonk E, et al. Comorbidity of chronic diseases in general practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(5):469–473. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90024-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hippisley-Cox J, Pringle M. Comorbidity of diseases in the New General Medical Services Contract for General Practitioners: analysis of QRESEARCH data. Nottingham: QRESEARCH; 2007. http://www.qresearch.org/Public_Documents/DataValidation/Co-morbidity%20of%20diseases%20in%20the%20new%20GMS%20contract%20for%20GPs.pdf (accessed 15 Oct 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Britt HC, Harrison CM, Miller GC, Knox SA. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in Australia. Med J Aust. 2008;189(2):72–77. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid R, Evans R, Barer M, et al. Conspicuous consumption: characterizing high users of physician services in one Canadian province. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8(4):215–224. doi: 10.1258/135581903322403281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C, Vanasse A. Multimorbidity is common to family practice. Is it commonly researched? Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:244–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Roos S, Knottnerus JA. Problems in determining occurrence rates of multimorbidity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(7):675–679. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NHS Primary Care Commissioning. QOF implementation business rules v11. http://www.primarycarecontracting.nhs.uk/145.php (accessed 15 Oct 2010)

- 17. The John Hopkins University ACG case-mix system. http://www.acg.jhsph.edu/html/International.htm (accessed 15 Oct 2010)

- 18.Office for National Statistics. Distribution of the European standard population, 1998. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/STATBASE/xsdataset.asp?vlnk=1260&More=Y (accessed 15 Oct 2010)

- 19.Uijen AA, van de Lisdonk EH. Multimorbidity in primary care: prevalence and trend over the last 20 years. Eur J Gen Pract. 2008;14(suppl 1):28–32. doi: 10.1080/13814780802436093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macleod U, Mitchell E, Black M, Spence G. Comorbidity and socioeconomic deprivation: an observational study of the prevalence of comorbidity in general practice. Eur J Gen Pract. 2004;10(1):24–26. doi: 10.3109/13814780409094223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breslau N, Reeb KG. Continuity of care in a university-based practice. J Med Educ. 1975;50(10):965–969. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197510000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bice TW, Boxerman SB. A quantitative measure of continuity of care. Med Care. 1977;15(4):347–349. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197704000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Roos S, Knottnerus JA. Problems in determining occurrence rates of multimorbidity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(7):675–679. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Halloran J, Miller GC, Britt H. Defining chronic conditions for primary care with ICPC-2. Fam Pract. 2004;21(4):381–386. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esteban-Vasallo MD, Dominguez-Berjon MF, Astray-Mochales J, et al. Epidemiological usefulness of population-based electronic clinical records in primary care: estimation of the prevalence of chronic diseases. Fam Pract. 2009;26(6):445–454. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perkins AJ, Kroenke K, Unutzer J, et al. Common comorbidity scales were similar in their ability to predict health care costs and mortality. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(10):1040–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Starfield B, Lemke KW, Herbert R, et al. Comorbidity and the Use of Primary Care and Specialist Care in the Elderly. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):215–222. doi: 10.1370/afm.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tooth L, Hockey R, Byles J, Dobson A. Weighted multimorbidity indexes predicted mortality, health service use, and health-related quality of life in older women. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(2):151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reid R, Evans R, Barer M, et al. Conspicuous consumption: characterizing high users of physician services in one Canadian province. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8(4):215–224. doi: 10.1258/135581903322403281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sturmberg JP. Morbidity, continuity of care and general practitioner workload: Is there a connection? Asia Pac Fam Med. 2002;1:12–17. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Weel C, Schellevis FG. Comorbidity and guidelines: conflicting interests. Lancet. 2006;367(9510):550–551. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayliss EA, Edwards AE, Steiner JF, Main DS. Processes of care desired by elderly patients with multimorbidities. Fam Pract. 2008;25(4):287–293. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cowie L, Morgan M, White P, Gulliford M. Experience of continuity of care of patients with multiple long-term conditions in England. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2009;14(2):82–87. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2009.008111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, et al. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ. 2003;327(7425):1219–1221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salisbury C, Sampson F, Ridd M, Montgomery AA. How should continuity of care in primary health care be assessed? Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(561):e134–e141. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X420257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]