Abstract

Background

Over half a million people die in Britain each year and, on average, a GP will have 20 patients die annually. Bereavement is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, but the research evidence on which GPs and district nurses can base their practice is limited.

Aim

To review the existing literature concerning how GPs and district nurses think they should care for patients who are bereaved and how they do care for them.

Design

Systematic literature review.

Method

Searches of AMED, BNI, CINAHL, EMBASE, Medline and PsychInfo databases were undertaken, with citation searches of key papers and hand searches of two journals. Inclusion criteria were studies containing empirical data relating to adult bereavement care provided by GPs and district nurses. Information from data extraction forms were analysed using NVivo software, with a narrative synthesis of emergent themes.

Results

Eleven papers relating to GPs and two relating to district nurses were included. Both groups viewed bereavement care as an important and satisfying part of their work, for which they had received little training. They were anxious not to ‘medicalise’ normal grief. Home visits, telephone consultations, and condolence letters were all used in their support of bereaved people.

Conclusion

A small number of studies were identified, most of which were >10 years old, from single GP practices, or small in size and of limited quality. Although GPs and district nurses stated a preference to care for those who were bereaved in a proactive fashion, little is known of the extent to which this takes place in current practice, or the content of such care.

Keywords: bereavement, community nursing, general practice, grief, primary care

INTRODUCTION

Bereavement is an almost universal life event. In the past it was viewed as a private affair that individuals lived through with the support of family, close friends, and their local communities.1 Over recent years, the increasing dispersion of families and the secularisation of society has created greater isolation for people who might previously have turned to their loved ones or to their faith during difficult times. The population is ageing with more people living alone: it is estimated that 45% of women and 15% of men above the age of 65 years are widowed.2 Death of a loved one, particularly of a spouse, is one of the most stressful life events on the Social Readjustment Rating Scale:3 it is associated with increased mortality and physical morbidity and a wide range of psychological reactions.2

GPs are familiar with grief and loss. An ‘average’ practice has 20 patient deaths per full-time GP each year,4 with a number of individuals who are newly bereaved in each case. As bereavement may have adverse health effects, some have reasoned that health professionals have a responsibility to address the needs of those who are bereaved and, as such, have advocated protocols that include a practice death register, entries into the notes of key relatives, and allocation of a key worker who undertakes ‘a series of reviews to help them through the grieving process’.5 Although such an approach might be appreciated by some, others who are bereaved may not desire such professional intervention.6,7 Viewing bereavement as a normal life event that should not be turned into a pathological condition, some health professionals have argued against ‘paternalistic medicalising of a normal process’ and ‘intrusive proactivity in this most fundamental of human experiences’.8

How this fits in.

On average, GPs in the UK will have 20 patient deaths annually and many people who are newly bereaved in their practice each year. Bereavement is an important cause of mortality and morbidity especially in high-risk groups such as older people and those who are socially isolated, and bereavement care is central to the recent Department of Health's End of Life Care Strategy.20 Bereavement care practice in primary care varies widely across the UK but, with guidelines based on expert opinion rather than evidence, it remains unclear what constitutes best practice. Ways to improve bereavement care include completing practice death registers, offering home visits and telephone consultations, and sending condolence cards. The extent to which such approaches occur in current practice, or would be welcomed by those who are bereaved, is largely unknown. Bereavement care is frequently overlooked in clinical practice and largely ignored in the primary care scientific community.

Most bereavement reactions are not complicated and, for the majority of people, the necessary support will be provided by family, friends, and various societal resources.2,9 Although GPs and the primary care team may be well placed to provide bereavement support, few have received education in this area10–12 and many are uncertain how to respond after a death beyond being understanding, accessible, and approachable.5,8 It is unclear how much primary care should be regarded as part of the general societal resources for all people who are bereaved, what constitutes best practice, or how primary care teams can best identify the minority for whom intervention may be needed. Guidelines and statements of expert opinion have been published, but most have a limited evidence base.5,13–16

The one published literature review of bereavement care in primary care17,18 was described by the authors as being ‘not fully systematic’ and only covered the literature up to 1996. Therefore, employing a systematic search strategy and formal narrative synthesis, the study undertook a systematic review of the literature concerning bereavement care provided by GPs and district nurses and their attitudes to such care.19

Aims

The study aimed to systematically review the literature concerning the two research questions:

how do GPs and district nurses think they should care for patients who are bereaved?

how do GPs and district nurses care for patients who are bereaved?

METHOD

A search of AMED, BNI, CINAHL, EMBASE, Medline and Psychinfo databases between January 1980 and May 2009 was undertaken, with the support of a professional librarian, to identify studies of GP and district nurse bereavement care for adults. The search terms used are shown in Box 1.

Box 1 Database search terms used

Bereavement

Grief

Bereav* or griev* or grief* or mourn*

AND – for GP search strategy:

Family physician

Family practice

General practice

General practitioner

General AND pract*

Primary health care

Community health care

Community health services

AND – for district nurse search strategy:

District nurs*

Community health nursing

Community nursing

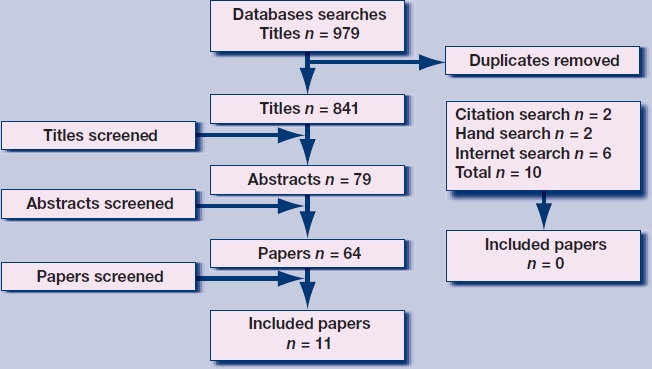

After removal of duplicate papers, titles were scanned to remove papers that were clearly not pertinent. Abstracts were then read by the researchers independently to identify potentially relevant papers; these were read in full by both authors independently, with any disagreements resolved by discussion. Further papers were sought by checking references and citation searches of included papers, conducting an internet search using Google Scholar, and hand searches of the British Journal of General Practice and Palliative Medicine between January 1980 and May 2009. These journals were selected as they had provided several titles in the initial search. Figures 1 and 2 show the processes.

Figure 1.

Selection process for papers on bereavement care provided by GPs.

Figure 2.

Selection process for papers on bereavement care provided by district nurses.

To fulfil the inclusion criteria, papers had to detail empirical studies that were written in English and reported GP or district nurse practice or their views about caring for adults (≥18 years) who are bereaved and grieving for deceased adults. Papers were excluded if they detailed bereavement following the death of a child, miscarriage or stillbirth; bereavement in childhood; or bereavement care outside primary care. Discussion articles, guidelines and opinion pieces with no new empirical data were also excluded.

From an initial 841 papers about GPs and 382 about district nurses, 13 papers meeting study criteria were identified: 11 related to GPs, and two with district nurses and one with both GPs and district nurses (Table 1). Pertinent information was entered into a data extraction form designed for this study, with these forms then entered into NVivo 8 and discussed at regular meetings at which a coding frame was developed: both researchers coded the data independently, resolving any disagreements by discussion. A narrative synthesis19 was undertaken and each paper weighted for quality, method, and relevance to the review questions using Gough's weight of evidence criteria.20

Table 1.

Summary of included papers

| Study | Design | Participants | Analysis | Key findings | Gough's weight of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harris23 (1998) | Postal questionnaire to GPs | 353 GPs from random sample of practices in South Thames region of UK | Quantitative | 65% of practice deaths were discussed in the practice, most often informaly; 40% of practices had a policy for identifying newly bereaved relatives; 56% of practices kept a death register; 39% of practices offered routine contact, usually a home visit; 62% referred patients to organisations such as CRUSE when appropriate | High |

| Birtwistle21 (2002) | Postal questionnaire to DNs | 323 DNs from south UK | Quantitative and qualitative | 74% reported their bereavement care was informed by personal experience of loss; 82% thought they should contact the person who was bereaved through visits, letters, or phone cals; 83% thought that DNs had an important role in bereavement care; 85% thought they should visit those who were bereaved if they had cared for the deceased; 10% thought bereavement visits to people who were newly bereaved were intrusive; 90% reported that someone from the practice usually attended the funeral | High |

| Blyth31 (1990) | GP questionnaire and semi-structured interviews with relatives | 5 GPs from one practice and 34 relatives of patients | Quantitative and qualitative | GPs reported al families in the sample to have been visited after the death. Seven of 34 relatives did not want to speak to the GP about their relative's death; 2 of 34 relatives felt they could not have approached their GP after bereavement | High |

| Brown30 (1995) | Retrospective GP practice case records review | Records of 45 bereaved relatives over 12 months in one practice | Quantitative | 37 of 45 people who were bereaved were contacted by GP or nurse following a patient's death | High |

| Lemkau25 (2000) | Postal questionnaire to US family physicians | 400 family physicians in USA | Quantitative | Practitioners strongly believed the identification and treatment of grieving patients to be an important part of their clinical responsibility; 83% evaluated most grieving patients themselves; 60% discussed spiritual concerns with the patient; 38% referred patients to the clergy | High |

| Cartwright26 (1982) | GP postal questionnaire and interviews with carers of deceased | 180 GPs and 206 older widowed people | Quantitative | 41 % of GPs thought they should make a home visit to older people who were bereaved; 36% thought it depended on the circumstances; 76% of those who were bereaved saw their GP during the 5–7 months after spousal death; 60% of patients who saw their GP before the funeral were given a prescription | Medium |

| Daniels32 (1994) | Postal questionnaire and interview of bereaved relatives | 18 bereaved relatives in one GP practice. | Quantitative and qualitative | Five of 18 had no GP contact in bereavement; 16 felt some acknowledgement from their GP would have helped – 10 by a home visit, five by a phone call and one by a letter | Medium |

| Field27 (1998) | Semi-structured GP interviews | 25 GPs | Qualitative | Most GPs had well-established procedures for caring for bereaved relatives | Medium |

| Lloyd-Wiliams33 (1995) | Structured interview schedule | 12 bereaved patients referred to a psychiatric service for bereavement counseling | Quantitative | Of 12 patients, eight had seen a GP twice and three once before referral; only one had been offered bereavement counselling in the practice; eight were referred to CRUSE; and two had ‘abnormal’ bereavement reactions needing specialist help | Medium |

| Peters24 (1994) | Postal questionnaire | 67 GPs of patients died in Royal London Hospital ICU | Quantitative | 82% of GPs offered bereavement care: 63% at GP surgery, 14% in home visits, 11 % offered specialist help within the practice (counselors, psychologists, etc); bereavement care was ranked as low priority for time | Medium |

| Saunderson22 (1999) | Questionnaire and interview | 25 London GPs | Quantitative and qualitative | 19 reported their personal experience informed their practice of bereavement care; 17 felt they had a responsibility to make contact with those who were bereaved | Medium |

| Wiles28 (2002) | Semi-structured GP interviews | 29 individual/group interviews with 50 GPs in south UK | Quantitative and qualitative | All relied on patients consulting for help with bereavement; GPs use time since bereavement to classify the reaction as normal or not, and refer to counsellors in cases of untimely death, death of a child and social isolation | Medium |

| Lyttle29 (2001) | Interviews with bereaved patients and community nurses | 10 bereaved people, 20 community nurses | Qualitative | DNs reported continuity of care and organised care was important for those who were bereaved, although time pressures limited their contribution. Those who were bereaved welcomed more than a one-off DN bereavement visit | Medium |

DN = district nurse.

RESULTS

GP and district nurse attitudes to bereavement care

Both GPs and district nurses see bereavement care as an important part of their roles21,22 and a satisfying aspect of personal care provision,23 although time pressures often result in it having low priority.23,24 They recognise the major impact of loss25 and see it as part of their duty to make contact with those who are recently bereaved,22,26 although some question the appropriateness of doing so, fearing being an unwelcome reminder of the death27 and medicalising grief.23 On occasions, such contacts give rise to practitioners feeling a sense of failure and guilt over the death.22 In the longer term, GPs are aware that bereavement may cause people to present with a range of symptoms and difficulties.28

Practitioners find it easier to contact those who are bereaved if they already have an established relationship with them.22 If the death is sudden or unexpected, they feel a particular responsibility to contact those who are bereaved,22 although the lack of prior relationship makes such contact challenging. A 2002 survey of district nurses found that 83% believed they had an important role in bereavement care and 82% thought they should make contact with patients who were bereaved.21 Some district nurses, however, see this as, primarily, a GP responsibility21 and view visiting people with whom they have no prior relationship as inappropriate practice.29 Both groups recognise the need for interprofessional coordination within the primary care team.23,29

There is a lack of clarity concerning best practice.27 Seeking to tailor their care to the needs of the individual,21,26 practitioners are uncertain whether to routinely contact all patients who are bereaved or to wait for them to consult.23,28 They are uncertain how best to make contact, that is, whether as a home visit, by telephone call, or by letter.21 No study has investigated the areas that GPs and district nurses view as important to cover beyond being sympathetic, empathetic, and compassionate.22 In the absence of training in the area, practice is largely based on personal experience of loss and cultural norms.21,22

GP and district nurse practice of bereavement care

There is considerable variability in the provision of bereavement care in primary care.25 Most of the studies reported care to be planned and proactive, with at least one contact from a nurse or doctor.30 This contact is usually a home visit23 (especially if the GP knew the person who is bereaved beforehand22), otherwise contact is made through a telephone call,22,23 surgery appointment,23,24 or letter.22 A 1998 survey of GP practices found 40% to have a policy of identifying those who are newly bereaved and 39% to offer routine contact, usually as a home visit.23 All next of kin who were bereaved were visited at home at least once in two studies,31,27 82% in another study.30 If district nurses visit, this is usually within a week of the death, often in the first 3 days.21 Some GPs are reactive in their practice, waiting for those who are bereaved to make contact for support;23 others practice in a mixed fashion, planning home visits for some and waiting for others to seek help if they desire.26,32

Some practices have policies for identifying those who are newly bereaved and routinely offer contact; this is usually done by a GP, but can also be carried out by a district nurse, counsellor, or practice nurse.23 This planned care is more common in practices with an interest in palliative care, practices that keep death registers, and those who regularly review deaths.23 In many practices, however, there is no such system in place22,23 and no pattern of care.24

The content of GP and district nurse contacts in bereavement has been little studied beyond practitioner reports. GPs report that they express their condolences, advise about the grieving process, encourage people to talk and express their feelings, and explore spiritual concerns.26 In many cases a prescription is issued,26 most commonly for hypnotics.25 District nurses report their contacts to have a more practical focus, discussing any arrangements to be made and local services available.21 No observational studies of bereavement practice were identified.

After an initial contact (if that occurs), it is commonly left for those who are bereaved to initiate further follow up;27,32 some practitioners, however, make contact more than once,21,31 especially for those perceived to be coping badly or who are socially isolated.27 District nurses have been reported to visit up to six times29 and sometimes attend the funeral.21

Involvement of others

Care is usually provided by the GP or district nurse without the involvement of others,23 but the charity Cruse Bereavement Care is widely used if longer-term support is needed.23,33 Referral to practice counsellors, many of whom have specific bereavement training,23 is reserved for untimely deaths, ‘abnormal’ bereavement (such as prolonged grief, particularly profound grieving, and depression or anxiety in the context of bereavement), and those who are socially isolated.25,28

Attitudes about care received from the GP and district nurse, from the perspective of those who are bereaved

The attitudes and expectations of people who are bereaved towards care from the GP or district nurse was outside the scope of this review and would require a different search strategy of further databases. Several of the studies included such views, however, which are included here to balance the professional focus.

Many people welcome contact from their practice during bereavement,29,32 especially as a home visit,32 although 20% in one study did not want to speak to a GP.31 Some are reluctant to make an appointment for bereavement issues, fearing that they will be wasting their GP's time.31 Some would like more support from their practice,29,31,26 including information about the cause of death, advice on the funeral and financial issues, or a supply of hypnotics.32 Although most do not feel they need bereavement counselling,31 those who do receive it find it beneficial.30

DISCUSSION

Summary of the main findings

This review of the literature reveals both GPs and community nurses view bereavement care as an important and satisfying part of their work, although one for which they have received little training. Bereavement care provision in primary care varies greatly: some practices have well structured proactive bereavement care protocols, with planned home visits, telephone consultations, or condolence letters: others are reactive in their approach, waiting for bereaved people to consult. There is a fear of medicalising a traumatic but normal life event. The literature provides a limited evidence base is for the development of guidelines for best practice.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This review has systematically identified and synthesised the literature concerning GP and district nurse bereavement care. That no additional papers were included from reference, citation and hand searches suggests the search strategy to have been comprehensive. In contrast to the previous review of Woof and Carter,17,18 the study has undertaken a formal systematic review and synthesis of the literature.

Implications for clinical practice

While the majority of people have sufficient resources to enable them to respond and adapt to this major life transition with virtually no support from health professionals2, there is a significant minority for whom bereavement can be a very difficult process during which they would benefit from professional help. National guidelines recommend that each bereaved person be made aware of support available,34 for example through a leaflet containing information about anticipated feelings and local services.35 If routine contact is not offered, professionals may erroneously assume they are coping, leaving them unaware of additional services and sources of support.35

Bereavement is a major risk factor for physical and mental morbidity and mortality, with a range of risk or protective factors identified in a recent literature review2 (Table 2). Although the literature is inconclusive for some of these factors, hindering the development of robust bereavement risk indices,36 these four categories of circumstances of the death, intrapersonal factors, interpersonal factors, and coping strategies provide a useful framework for practitioners to seek to identify those at particular risk of adverse outcomes, who may be reluctant to consult ‘just for bereavement’ and be in particular need of proactive care.

Table 2.

Potential risk or protective factors in bereavementa

| Circumstances of death | Cause of death: sudden, expected, traumatic, suicide |

| Circumstances: multiple losses, witnessing extreme distress in dying phase | |

| Lost relationship: spouse, child | |

| Quality of relationship with deceased | |

| Concurrent stresses: financial hardship resulting from loss | |

| Intrapersonal factors intrinsic to person who is bereaved | Personality style: optimism, high self-esteem, secure attachment |

| Predisposing factors: pre-bereavement depression, previous bereavements | |

| Religious beliefs and other meaning systems | |

| Sociodemographic: widowers, children, ethnic group | |

| Interpersonal factors | Social support: social isolation, cultural and social embedding |

| Economic: income has little effect | |

| Professional support and intervention | |

| Coping strategies | Grief work: sharing, disclosure, avoidance, repression |

| Emotional regulation: combination of confrontation and avoidance | |

Taken from Stroebe et al (2007)2 and reproduced with permission.

However, increasing part-time working in general practice, with reduced personal continuity of care, is leading to GPs and district nurses being less familiar with families of patients and thus less likely to make contact in bereavement.22,29 In addition, GP trainees rarely cover bereavement during their vocational training,10 a deficit that GP principals often do not subsequently make up.11,12 Many practitioners would welcome further education in this area,25 as called for by several review papers.21,24,30

Implications for future research

Most of the included papers are now old: most were published over 10 years ago and none since 2002. Primary care and society are different in many respects from the time that these studies were undertaken: GPs are increasingly working part time, with reduced continuity of care especially out of hours; an ageing population is frequently living alone, socially isolated from family and friends. Most are small studies, often undertaken in one GP practice, and thus of limited generalisability. Practitioner self-report of care may not reflect actual care delivery in practice, for example the degree to which reported care is provided for all bereaved patients or the content of consultations. Identification of the bereaved beyond the partner or household of the deceased has not been studied, nor has the care of those not registered with the practice or wider family and friends. Importantly, little is known of the views and expectations of care from their GP practice of the bereaved themselves. These issues need to be addressed in future research studies if primary care is to provide evidence-based optimal care for bereaved people.

CONCLUSION

Bereavement care is frequently overlooked in clinical practice and largely ignored in the primary care scientific community. The literature concerning bereavement care in primary care is limited: most of the papers identified are over 10 years old, and guidelines are based on expert opinion rather than empirical data. From this, rather thin evidence base the study would submit that it would be appropriate for GPs and district nurses to offer support to all patients who are bereaved and to proactively contact those who might be at risk of adverse bereavement outcomes. This is not to ‘psychologise and pathologise grief as the next stage in the long-running process of the medicalisation of life’ as some have suggested,27 but is rather a practical way to provide ‘appropriate, responsive, non-intrusive support to people who have experienced a bereavement’.27

A new study of bereavement care in 21st-century primary care is needed, investigating the views of GPs and district nurses in modern primary care, documenting care provision in practice and, most importantly, investigating the views of those who are bereaved about the contact and support they would like from primary care during the difficult period of bereavement. This we are planning to undertake.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of Isla Kuhn, reader services librarian at the University of Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine library.

Funding body

Shobhana Nagraj is funded by the NIHR Academic Clinical fellowship programme. Stephen Barclay is funded by Macmillan Cancer Support through its Research Capacity Development Programme and the National Institute for Health research (NIHR) CLAHRC (Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care) for Cambridgeshire and Peterborough. This study was undertaken as part of the above Fellowships.

Competing interests

Stephen Barclay is a member of the NIHR Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for Cambridgeshire and Peterborough.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Field D, Payne S, Relf M, Reid D. Some issues in the provision of adult bereavement support by UK hospices. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(2):428–438. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1960–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmes T, Rahe R. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale: a cross-cultural study of Japanese and Americans. J Psychosom Res. 1967;11(2):213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barclay S. Palliative care of non-cancer patients: a UK perspective from primary care. In: Higginson I, Addington-Hall J, editors. Palliative care for non-cancer patients. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 172–188. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charlton R, Dolman E. Bereavement: a protocol for primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 1995;45(397):427–430. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Main J. Improving management of bereavement in general practice based on a survey of recently bereaved subjects in a single general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50(460):863–866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al S, Wimpenny P, Unwin R, et al. Literature review on bereavement and bereavement care. Aberdeen: The Joanna Briggs Institute, Robert Gordon University; 2006. http://www4.rgu.ac.uk/files/BereavementFinal.pdf (accessed 18 Nov 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazza D. Bereavement in adult life. GPs should be accessible, not intrusive. BMJ. 1998;317(7157):538–539. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7157.538a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Currow DC, Allen K, Plummer J, et al. Bereavement help-seeking following an ‘expected’ death: a cross-sectional randomised face-to-face population survey. BMC Palliat Care. 2008;7:19. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-7-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Low J, Cloherty M, Barclay S, et al. A UK-wide postal survey to evaluate palliative care education amongst general practice Registrars. Palliat Med. 2006;20(4):463–469. doi: 10.1191/0269216306pm1140oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barclay S, Todd C, Grande G, Lipscombe J. How common is medical training in palliative care? A postal survey of general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47(425):800–804. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barclay S, Wyatt P, Shore S, et al. Caring for the dying: how well prepared are general practitioners? A questionnaire study in Wales. Palliat Med. 2003;17(1):27–39. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm665oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlton R, Sheahan K, Smith G, Campbell I. Spousal bereavement – implications for health. Fam Pract. 2001;18(6):614–618. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.6.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson A. Bereavement: implications for health visiting practice. Community Pract. 2001;74(5):182–184. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenner P, Manchershaw A. A group approach to overcome loss. A model for a bereavement service in general practice. Prof Nurse. 1993;8(10):680–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyttle C. Bereavement visiting in the community. Eur J Palliat Care. 2005;12:74–77. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woof WR, Carter YH. The grieving adult and the general practitioner: a literature review in two parts (part 1) Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47(420):443–448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woof WR, Carter YH. The grieving adult and the general practitioner: a literature review in two parts (part 2) Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47(421):509–514. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petticrew P, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a patractical guide. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gough D. Weight of evidence: a framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Research Papers in Education. 2010;22(2):213–228. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birtwistle J, Payne S, Smith P, Kendrick T. The role of the district nurse in bereavement support. J Adv Nurs. 2002;38(5):467–478. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saunderson EM, Ridsdale L. General practitioners' beliefs and attitudes about how to respond to death and bereavement: qualitative study. BMJ. 1999;319(7205):293–296. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7205.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris T, Kendrick T. Bereavement care in general practice: a survey in South Thames Health Region. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48(434):1560–1564. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters H, Lewin D. Bereavement care: relationships between the intensive care unit and the general practitioner. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 1994;10(4):257–264. doi: 10.1016/0964-3397(94)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemkau JP, Mann B, Little D, et al. A questionnaire survey of family practice physicians' perceptions of bereavement care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(9):822–829. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.9.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cartwright A. The role of the general practitioner in helping the elderly widowed. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1982;32(237):215–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Field D. Special not different: general practitioners' accounts of their care of dying people. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(9):1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)10041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiles R, Jarrett N, Payne S, Field D. Referrals for bereavement counselling in primary care: a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyttle CP. Bereavement visiting: older people's and nurses' views. Br J Community Nurs. 2001;6:629–635. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2001.6.12.9448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown CK. Bereavement care. Br J Gen Pract. 1995;45(395):327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blyth AC. Audit of terminal care in a general practice. BMJ. 1990;300(6730):983–986. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6730.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daniels C. Bereavement and the role of the general practitioner. J Cancer Care. 1994:103–109. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lloyd-Williams M. Bereavement referrals to a psychiatric service: an audit. Eur J Cancer Care. 1995;4(1):17–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.1995.tb00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cruse Bereavement Care. 2001 Bereavement Care Standards: UK Project. Standards for Bereavement Care in the UK. http://www.crusebereavementcare.org.uk/PDFs/UKStandardsBereavementCare.pdf (accessed 29 Nov 2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Improving supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer. London: NICE; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agnew A, Manktelow R, Taylor B, Jones L. Bereavement needs assessment in specialist palliative care: a review of the literature. Palliat Med. 2010;24(1):46–59. doi: 10.1177/0269216309107013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]