Abstract

Background

Current models of end-of-life care (EOLC) have been largely developed for cancer and may not meet the needs of heart failure patients.

Aim

To review the literature concerning conversations about EOLC between patients with heart failure and healthcare professionals, with respect to the prevalence of conversations; patients' and practitioners' preferences for their timing and content; and the facilitators and blockers to conversations.

Design of study

Systematic literature review and narrative synthesis.

Method

Searches of Medline, PsycINFO and CINAHL databases from January 1987 to April 2010 were conducted, with citation and journal hand searches. Studies of adult patients with heart failure and/or their health professionals concerning discussions of EOLC were included: discussion and opinion pieces were excluded. Extracted data were analysed using NVivo, with a narrative synthesis of emergent themes.

Results

Conversations focus largely on disease management; EOLC is rarely discussed. Some patients would welcome such conversations, but many do not realise the seriousness of their condition or do not wish to discuss end-of-life issues. Clinicians are unsure how to discuss the uncertain prognosis and risk of sudden death; fearing causing premature alarm and destroying hope, they wait for cues from patients before raising EOLC issues. Consequently, the conversations rarely take place.

Conclusion

Prognostic uncertainty and high risk of sudden death lead to EOLC conversations being commonly avoided. The implications for policy and practice are discussed: such conversations can be supportive if expressed as ‘hoping for the best but preparing for the worst’.

Keywords: communication, death, heart failure, palliative care

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure is an unpredictable, progressive, and incurable condition. Around 1 million UK citizens1 and 5 million US citizens2 are estimated to be living with heart failure: 1% of the general population and 15% of those aged over 80 years.3,4 Heart failure is a leading cause of hospital admissions,2,4,5 and a substantial drain on healthcare resources:6,7 it is mentioned on one in eight US death certificates.8

The prognosis associated with a diagnosis of heart failure is poor, worse than for many cancers;9 38% of patients are dead within 1 year of diagnosis and 60% within 5 years.4,10 Around 50% of deaths are sudden, especially in the less severe stages, from arrythmias or ischaemic events;11 many of these patients are reported to have had a good quality of life in the month before death.12 Progressive pump failure is the more common mode of death in advanced disease,11,13 with disabling symptoms of a similar prevalence to those of patients with advanced cancer:6,14 fatigue, breathlessness, limited mobility, restricted social life, poor quality of life, complex medication regimens, and considerable impact on the psychological and physical health of family caregivers.15

The palliative care needs of heart failure patients were first recognised in NHS policy in 2000,16 and were described as a ‘radical new departure’ for palliative care services.17 In 2003, national guidelines acknowledged considerable unmet need for palliative care in heart failure, especially in planning for the future and end-of-life care (EOLC).18 Community-based heart failure nurses have been in place since 2003: their focus is primarily on optimising medical management and admission reduction,19 and in some areas also include palliative care. The 2004 national guidelines for Supportive and palliative care for advanced heart failure20 were largely based on guidelines for cancer,21 and highlighted the need for advanced communication skills training for clinicians. The first step of the 2008 NHS EOLC strategy ‘End of life care pathway’22 is entitled ‘Discussions as the end of life approaches’. While recognising that some may not wish to hold such discussions, and acknowledging that heart failure patients’ trajectories to death are much more varied than previously conceptualised,23–25 the strategy also calls for ‘a significant culture shift within the public and the NHS’ towards more open communication about the end of life. There is increasing debate as to whether a ‘one size fits all’ approach to EOLC, based on the needs of cancer patients, is appropriate.26 The national audit of people admitted to hospital with heart failure4 highlights the importance of specialist cardiology teams in managing acute episodes; long-term care is largely undertaken in primary care.

How this fits in.

The importance of high-quality end-of-life care for all patient groups has become increasingly recognised over recent years. The 2008 NHS End of Life Care Strategy22 describes a care pathway in which step 1 is ‘Discussions as the end of life approaches’. While acknowledging that some patients may not wish to have such conversations, the strategy calls for a culture change towards more open discussion with patients. Models of end-of-life care have largely been developed from experience with cancer patients; there is increasing concern that a ‘one size fits all’ cancer-based approach may not be appropriate for those with other life-limiting illnesses. The uncertain prognosis of heart failure, with its risk of sudden death, calls for the development of a unique approach to discussions concerning the end of life.

Discussing end-of-life issues with heart failure patients is challenging. The very use of the term ‘heart failure’ may be unclear and frightening to patients,1 who often have limited understanding of the nature and seriousness of their condition;27–29 given the technical issues involved and the complexity of drug regimes, many defer to their clinicians, preferring a passive role in decision making.5,30 Clinicians often have a treatment imperative that makes it difficult for them to face the limitations of modern medicine and introduce EOLC issues.31,32 Prediction of the time of death is almost impossible, confounding even the best prognostic models:9,33 in one study more than half of those who died within 3 days had been estimated to have a prognosis of over 6 months.12 Patients may have been close to death on several occasions, and seek hope through a positive reconstruction of the threat to life.34 Although most clinicians believe patients should be told the truth, many withhold information or avoid the topic in practice;35 prognostic uncertainty, time pressures, lack of communication skills training, feeling of medical failure, uncertainty about timing and content, and fear of upsetting patients have all been suggested as contributing to a reluctance to address EOLC issues.36 Although guidelines recommend frank conversations,37,38 and in the US discussions of advanced directives are legally mandated for all hospitalised patients, in practice such conversations are rare for patients with a wide range of life-limiting illnesses.9

Much EOLC research has been undertaken with mixed samples of patients with cancer, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and other life-limiting illnesses. This literature reveals that many ‘EOLC conversations’ are largely limited to advanced directive paperwork and choices for resuscitation rather than communication about goals and future care options.39–42 There is a low level of agreement between doctors and patients,9,43,44 and doctors and family members,45 as to whether EOLC conversations have taken place at all, and discrepancy between these groups regarding their perception of the amount of information exchanged;46 this raises questions concerning the reliability of clinician reports and the adequacy of the form and content in which clinicians discuss EOLC.

This systematic literature review develops and updates that undertaken in 2004 by Parker and colleagues,35,46,47 whose review of patients' views and experiences of end-of-life conversations largely comprised studies of patients with cancer. This review focuses exclusively on studies of patients with heart failure and includes all publications to date.

Aims

The aims of the study are to review the literature concerning conversations about EOLC between patients with heart failure and healthcare professionals, with respect to:

the prevalence of conversations;

patients' and practitioners' preferences for their timing and content; and

the facilitators and blockers to conversations.

METHOD

A search of CINAHL, Medline and PsycINFO databases between January 1987 to March 2010 was undertaken. Box 1 summarises the search terms used.

Box 1 Summary of search strategy

Disease

heart failure

cardiac rehabilitation

cardiac patients

AND Discussions

approach OR communicat* OR consult* OR inform* OR introduce OR mention OR raise OR talk OR verbalise OR vocalise

Conversation

Address

Discuss

AND End of life

advanced care plan

death OR die OR dying

decision making

DNR

end of life

hospice

palliative care

treatment refusal

Inclusion criteria were: articles published in peer-reviewed journals, written in English, reporting studies of adult patients with heart failure and/or their healthcare professionals concerning discussions of care at the end of life. Exclusion criteria were: studies of knowing or telling the diagnosis, understanding treatment, symptom management, prognostication, patients who are unconscious or lack capacity, patient – family communication, discussion articles, guidelines, and theory or opinion pieces with no new empirical data. Conversations concerning deactivation of implanted cardiac defibrillators were also excluded due to the rarity of their current use and the very specific nature of the EOLC issues involved.48

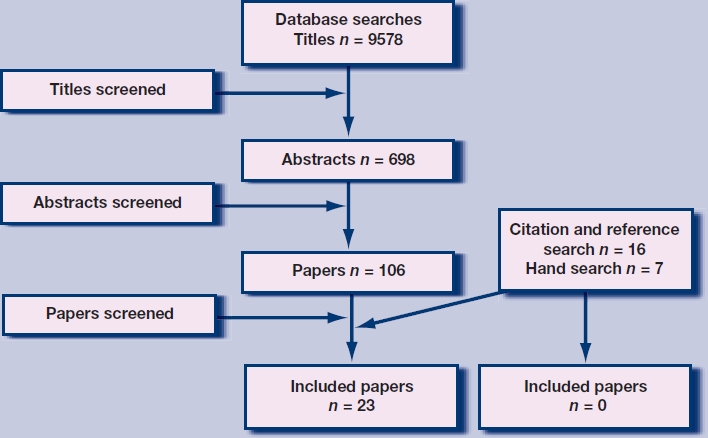

Devising a search strategy was very challenging due to a lack of MeSH (medical subject heading) terms for this topic area, as reported by Parker et al in their earlier review.47 The information technologist developed the database search strategy with the team; given the diffuse search terms involved, this generated 9576 titles that were screened by one researcher to exclude articles that were clearly not pertinent. Two reviewers read 698 abstracts independently to identify potentially relevant papers, with any disagreements resolved by discussion; 106 papers were then read in full by two reviewers independently, of which 23 were agreed to meet study criteria. Four studies each yielded two included papers: Agard et al49 and Agard et al,50 Barnes et al51 and Gott et al,52 Boyd et al53 and Murray et al,54 and Harding et al55 and Selman et al.56 Further papers were sought by checking references and searching the citations of included papers (yielded 16 papers), and hand searches of the European Journal of Heart Failure and Palliative Medicine between the above dates (yielded seven papers): these 23 additional papers were read in full by two reviewers but none were included. Figure 1 shows the process.

Figure 1.

Selection of papers.

Empirical data from the results sections of each paper that were pertinent to the review questions were recorded in a data-extraction form and entered into NVivo for qualitative analysis; authors' comments in discussion sections of papers were not included in data extraction or synthesis. Framework analysis was employed,57 using a coding frame derived from the review questions, with discussion of emergent subthemes at regular team meetings; two researchers coded the extracted data from each paper independently, resolving disagreements by discussion. Data synthesis employed a narrative approach;58 this descriptive qualitative approach is now widely used in synthesis of heterogeneous and predominantly qualitative studies.

Each paper was weighted for its overall contribution towards answering the review question using Gough's ‘weight of evidence’ criteria (Box 2).59 Table 2 summarises the included papers, with their weighting on these criteria.

Box 2 Gough's ‘weight of evidence’ framework59

Each paper is weighted (high, medium, low) on three initial criteria, followed by a fourth criterion combining these three:

Coherence and integrity of the evidence in its own terms – a generic and non-review-specific judgement about the quality of execution of the study, either qualitative or quantitative, based on the generally accepted criteria for evaluating the quality of the types of evidence.

Appropriateness of the form of evidence for answering the review question – a review-specific judgement about the research method and design employed for answering the review questions: the fitness for purpose of that form of evidence.

Relevance of the evidence for answering the review question – a review-specific judgement about the relevance of the focus of the evidence for the review question: for example the sample, type of evidence gathering, or analysis that is central to the review question.

Overall assessment of study contribution to answering the review question – a combination of these three sets of judgements combined to form an overall assessment of the extent that a study contributes evidence to answering the review question.

Table 2.

Summary of included papers

| First author | Reference | Participants | Aims | Research methods used | Key findings | Weight of evidencea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight of evidence = high | ||||||

| Agard50 | Heart and Lung 2004; 33(4): 219–226 | 40 HF patients, ≥60 years, 13 NYHA stage II, 21 stage IIIa, 5 stage IIIb, 1 stage IV | To explore patients' knowledge of HF, attitudes toward medical information, and barriers to improving their knowledge | Semi-structured qualitative interview | • Most patients unaware of the meaning of HF and its poor prognosis, and content with this • 32/40 did not want prognostic information • 4/40 wanted more information about how HF would affect their lives • If patients thought of approaching death this was in the context of ageing rather than HF | M H H – H |

| Aldred60 | J Adv Nurs 2005; 49(2): 116–124 | 10 patients with HF and their partners, ≥60 years, 3 NYHA stage II, 6 stage III, 1 stage IV | To explore the impact of HF on the lives of older patients and their informal carers | Semi-structured qualitative interview | • Most would have welcomed more information about prognosis and how the condition would progress • Commonly preoccupied with thoughts about the future • Many would have welcomed opportunity to discuss their fears with someone • Doctors perceived as being too busy to talk | H H H – H |

| Barnes51 | Health Soc Care Community 2006; 14(6): 482–490 | 44 patients with HF, ≥60 years, NYHA stage III/IV. Primary care professionals involved in HF management from these patients' practices (39 GPs, 37 nurses, 2 health visitors, 1 nursing home manager) | To explore attitudes of older people and primary care professionals toward communication of diagnosis, prognosis and symptoms in HF | Qualitative interviews with patients. Focus groups with healthcare professionals | • Few patients had discussed prognosis with any health professional. • Several patients preferred not to know about HF, as that would cause them worry • Professionals found prognostic uncertainty hindered discussion • GPs found it difficult to diagnose HF • GPs reluctant to discuss terminal nature of HF | HHH – H |

| Borbasi61 | Austr Crit Care 2005; 18(3): 104-113 | 17 nurses caring for end-stage HF patients, in homes and hospices | To understand nurses' experiences of caring for patients dying from HF | In-depth open-ended interviews | • ‘Good death’ seen as: patient understands death is close, accepts this. and plans for the end of life • ‘Bad death’ seen as: unexpected death, patient unwilling to accept death approaching, fights all the way, unprepared for death | M H H – H |

| Boyd53 | EurJ Heart Fail 2004; 6: 585–591 | 18 patients with NYHA stage IV HF | To understand the range of issues facing patients with advanced heart disease and their lay carers during the last months of life | Qualitative serial interviews every 3 months for ≤1 year. Focus group with 16 health professionals | • Few patients had discussed their wishes for EOLC with health professionals • Patients reluctant to raise these issues themselves • Health professionals found difficulty in finding vocabulary to discuss HF and avoided-end-of-life discussions due to uncertain prognosis and risk of sudden death | H H H – H |

| Brannstrom62 | Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2005; 4: 314-323 | 11 nurses working in an advanced home care unit | To understand the meaning of being a palliative nurse for persons with HF in advanced homecare | Qualitative interviews | • Patients unsure how to show clinicians that they want to talk • If patients are well informed, will be less anxious • Important for patient to be clear they are approaching the end of life | H H H – H |

| Caldwell63 | Can J Cardiol 2007; 23(10): 791-796 | 20 patients with NYHA stage II or III HF | To identify preferences of patients with advanced HF regarding communication about their prognosis | Qualitative semi-structured interviews | • Patients do not want to think about end of life when well, but not able to engage with conversations when ill • Hesitate to ask about prognosis: reluctant to put them on the spot, time pressures • Want honest communication from doctors • Prefer doctors to initiate conversations | H H H — H |

| Gott52 | Soc Sci Med 2008; 67(7): 1113-1121 | 40 people with HF NYHA stage II—IV age ≥60 years (median age 77 years) | To explore the extent to which older people's views and concerns about dying match the revivalist model of ‘good death’, which underpins palliative care delivery | Semi-structured interviews | • 1/40 had discussed advanced care plans • Few had discussed prognosis with a clinician • Some acknowledged their limited prognosis but still did not want prognostic information • Some preferred a sudden death – avoided increasing dependency • Thinking about end of life was a source of anxiety | H H H – H |

| Hanratty64 | BMJ 2002; 325: 581-585 | 34 doctors involved in HF care: 10GPs, 8 cardiologists, 10 general physicians/geriatricians, 4 general medical doctors, 6 palliative care doctors | To identify doctors' perceptions of the need for palliative care for HF and the barriers to change | Qualitative focus groups | • Fear saying the wrong thing, giving bad news too early, patients losing hope • Prognosis difficult: poor outlook accepted by doctors too late in the illness • End-of-life issues difficult to discuss with patients | H H M – H |

| Harding55 | J Pain Symptom Manage 2008; 36: 149-156 | 20 patients with NYHA class III–IV and 12 of their carers; 12 doctors and nurses working in palliative care and cardiology | To generate recommendations for the provision of information to HF patients and their family carers | Semi-structured qualitative interviews | • No patients had discussed disease progression or EOLC • Patients want easily comprehensible information, given directly and sensitively • Patients and carers reluctant to ask questions • Prognostic difficulties hinder conversations • Cardiologists welcome palliative care and communication skils training • Palliative care professionals welcome HF training • Need to developshared care pathways | H H H – H |

| Horne65 | Palliat Med 2004; 18: 291-296 | 20 patients with HF, 11 NYHA stage IV, 7 NYHA stage III, 2 NYHA stage II | To explore the experiences of patients with severe HF and identify their needs for palliative care | Qualitative semi-structured interviews | • Patients had some sense of their poor prognosis • Mixed views about wanting to know prognosis • All had thought about dying but few had discussed these issues with clinicians | H H H – H |

| Murray54 | BMJ 2002; 325: 929–934 | 20 patients with NYHA stage IV HF | To compare the illness trajectories, needs, and service use of patients with cancer and those with advanced non-malignant disease | Serial in-depth qualitative interviews, every 3 months, up to 1 year | • Patients had little understanding of their condition, treatment aims or prognosis • A palliative care approach was rarely apparent | H H H – H |

| Rogers66 | BMJ 2000; 321: 605–607 | 30 patients with HF admitted to hospita in past 20 months: 7 NYHA stage II, 12 NYHA stage III, 8 NYHA stage IV | To explore patient understanding of HF, their need for information, and issues concerning communication | Qualitative in-depth interviews | • Some patients wanted to know more about their illness and prognosis • Some wanted to make provision for death • Others had not/did not wish to acknowledge prognosis – ambivalent about learning more about their condition • Anxieties that doctors would withold information | H H H – H |

| Selman56 | Heart 2007; 93: 963–967 | 20 patients with heart failure, 14 NYHA stage III, 2 stage III–IV, 4 stage IV; 11 family carers, 12 clinicians (6 palliative care, 6 cardiology) | To investigate patients' and carers' preferences regarding future treatment and communication between staff, patients, and carers concerning the end of life | Qualitative semi-structured interviews | • No patients had discussed end-of-life preferences with clinicians – few had discussed with family members • Cardiologists reluctant to raise end-of-life issues due to uncertain prognosis and lack of communication skills. Happy to discuss if patients raise issues | H H H – H |

| Strachan67 | Can J Cardiol 2009; 25(11): 635–640 | 106 patients (mean age 78.5 years) with heart failure NYHA class IV or ejection fraction <25% | To identify patients' perspectives on ways to improve EOLC for patients with HF | Structured survey of inpatients | • 11% had discussed life expectancy with doctor • 58% understood they were approaching the end of life • 21 % do not regard end-of-life issues as relevant to them • Most important aspects of EOLC were: to avoid life support if no hope of recovery, not to be a burden on their family and honest communication of information by doctors | H H H – H |

| Wotton68 | J Cardiovasc Nurs 2005; 20(1): 18–25 | 17 nurses experienced in palliative and cardiac care | To describe nurses' perceptions of factors influencing care for patients in the palliative phase of HF | Qualitative semi-structured interviews | • Nurses thought most patients do not want to know they are dying • Clinicians reluctant to explain severity and progression of HF • Clinicians focus on keeping patient stable rather than EOLC | H H H – H |

| Weight of evidence = medium | ||||||

| Agard49 | J Intern Med 2000; 248: 279–286 | 40 HF patients, ≥60 ≥60 years, 13 NYHA stage II, 21 NYHA stage IIIa, 4 NYHA stage IIIb, 2 NYHA stage IV | To understand patient involvement in decisions concerning CPR | Semi-structured qualitative interview plus some structured questions | • 1 of 40 patients had discussed CPR • 70% would like doctor to raise the issues • Most prefer to leave the initiative with doctors – few would raise these issues themselves | M H M – M |

| Formiga69 | Q J Med 2004; 97: 803–808 | 80 patients admitted with HF age >64 years (mean age 79 years); 10% with NYHA stage II, 74% NYHA stage III, 16% NYHA stage IV | To determine the preferences for CPR and EOLC in older patients hospitalised for heart failure | Structured interview | • 2/80 patients had discussed their wishes for EOLC with doctors | M M M – M |

| Haydar70 | J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52: 736–740 | 109 patients enrolled in a house calls programme with HF (29), dementia (79), or both (34). Mean age of HF patients 82.6 years | To compare the end-of-life preferences of older people with dementia and HF | Medical records review: demographics, hospital use, place of death, and discussions relevant to advance planning and hospice enrolment | • Focus of advanced planning discussions for HF patients = do not resuscitate orders | M L M – M |

| Heffner71 | Chest 2000; 117: 1474–1481 | 415 patients participating in cardiovascular rehabilitation programs: 248 HF NYHA stage I, 129 NYHA stage II, 33 NYHA stage III, 1 NYHA stage IV | To assess the interests of cardiac patients in advance planning and their willingness to participate in end-of-life education during rehabilitation | Structured questionnaire survey | • The small group who had held discussions were largely around life-sustaining interventions rather than EOLC • Most wanted more information about advanced directives: 41 % thought this reassuring, 18% anxiety provoking but worthwhile, 4% too anxiety-provoking to pursue • Patients prefer clinicians to initiate discussions | H M M – M |

| Rodriguez5 | Heart Lung 2008; 37(4): 257–265 | 25 patients with HF: 2 NYHA class I, 13 NYHA class II, 9 NYHA class III, 1 NYHA class IV | To explore patients' knowledge about HF, and understanding of treatment and prognosis | Semi-structured qualitative interviews | • Patients had poor undersatnding of their illness • 2 patients reported advanced care planning discussions – both initiated by clinicians • Few had discussed prognosis, but many wanted to hear about it | H M M – M |

| Willems72 | Palliat Med 2004; 18: 564–572 | 31 patients with HF, 1 NYHA stage I, 5 NYHA stage II, 19 NYHA stage III, 2 NYHA stage IV, 4 not stated | To explore the ideas and attitudes of patients with end-stage HF concerning dying | Prospective longitudinal multiple case study using semistructured interviews, taped and transcribed | • Most thought about death infrequently • Thoughts of death were more common when admitted to hospital but receded as the threat to life resolved • Most did not think they might die earlier because of their condition | M H M – M |

| Weight of evidence = low | ||||||

| Johnson73 | Br J Cardiol 2009; 16: 194–196 | Records of 235 deceased patients who had been under the care of HF nurse specialists | To review the place of death of patients on the caseload of HF nurse specialists | Retrospective nursing records review supplemented by nurses' recall several months after the deaths | • 38% of deaths were sudden • In one area 112/149 (75%) cases had evidence of advance planning discussion, documented in records or recalled by nurse • In another area, preferred place of death was recorded for 34/86 (40%) patients | L L M – L |

CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation. EOLC = end-of-life care. HF = heart failure. NYHA = New York Heart Association.

Assessed using Gough's weight of evidence framework: 59 1 = coherence and integrity of the evidence in its own terms; 2 = appropriateness of form of evidence for answering review question; 3 = relevance of the evidence for answering the review question; 4 = overall assessment of study contribution to answering the review question.

RESULTS

Are end-of-life care discussions being held?

Eleven papers reported heart failure patients' experiences of the prevalence of EOLC discussions. Two (from the same study) found no patients had discussed their EOLC preferences, disease progression, or future care options with healthcare professionals:55,56 nine papers reported that few patients had discussed prognosis,51,52,67,74 EOLC,52,53,54,69 cardiopulmonary resuscitation or other life-sustaining interventions,49,69,71 or plans for future care.53,71,74 A uniform picture emerges that the great majority of patients with heart failure do not perceive that they have had a discussion with their healthcare professionals concerning the end of life.

In contrast, two studies of medical records reported most patients had had EOLC discussions. In one, these conversations focused on disease-modifying therapy rather than EOLC.70 The second scored lowest on weight of evidence, for reasons outlined in Table 2.73

Patient attitudes towards end-of-life care discussions

Patients have diverse attitudes towards conversations with healthcare professionals. Some welcome these conversations. They desire more information concerning prognosis,55,60,63,67,71,74 resuscitation,67 and how their condition is likely to progress,49,60,71 as this allows them to put their affairs in order and make plans for their families.63,66,74 An opportunity to discuss their fears about the future is reassuring;60,71 for some the knowledge that death could be sudden is welcomed, as this is their preferred mode of death.52

Others do not wish to have these conversations. They rarely think about death,50,72 and prefer not to think about their prognosis;50 they do not regard end-of-life issues as relevant to them,67 seeing their condition as part of growing old.54 They accept a low level of knowledge about their illness and do not view themselves as capable of understanding it, preferring to leave medical issues to their professionals.50 Some explicitly do not want prognostic information,52 and avoid the subject when raised by doctors,51 preferring to enjoy the present without conversations that will cause worry to themselves50,52 or their families,52,65 and a loss of hope50,53,66,71 Others have mixed and ambivalent views, having some awareness but not wishing to openly acknowledge their poor prognosis.65–67

When conversations are desired, patients want these to be held sensitively,50,55 with honesty,55,63,65,67 and repeated opportunities to talk.63 Patients are concerned that they may not be able to process information when feeling unwell,63 and may be afraid to ask questions,55 being reluctant to put doctors in uncomfortable positions:63 they fear that doctors will not want to talk,63,66 or will only give incomplete information.55,67

Patient preferences for the timing of conversations

The few studies that have investigated when patients would like to have these conversations reveal a dilemma. Patients are most likely to consider end-of-life issues when unwell and in hospital:67,72 a time when they are least likely to be physically, mentally, or emotionally able to absorb important information or engage in difficult conversations.63 Once the threat to life has receded, they are less likely to wish to discuss their prognosis and EOLC.63 The majority of patients prefer doctors to initiate these conversations,63,71 although a significant minority would prefer doctors to wait for patients to bring these issues up.71 Some suggest that doctors might ‘plant the seed’ at a time when symptoms are well managed and the patients feel relatively well and able to be more in control of the conversation.63

Healthcare professionals' attitudes to end-of-life care discussions

Healthcare professionals find it difficult to establish a diagnosis of heart failure at times,51 and then struggle to find a vocabulary to explain the condition.53 They see prognostication in heart failure as very difficult given the uncertain disease trajectory,51,55,56,62,64 and that comorbid conditions may be a more probable cause of death;51 in light of the potential for a catastrophic event such as sudden death, some feel unable to discuss future plans.53,54 Some do not themselves realise the terminal nature of heart failure,54 or believe that patients rarely acknowledge this.56,62 Doctors tend to focus on current aspects of medical management rather than the future,51,68 approaching heart failure as a problem to be fixed instead of a terminal illness;51 this may hinder communication concerning wider and longer-term patient needs.55,62 They fear alarming patients unnecessarily,51 creating anxiety and depression,51 destroying hope,64 and causing patients to give up the fight for life.64

The communication challenges are considerable. Although healthcare professionals believe that heart failure patients have a right to be informed of their prognosis,51 they want to avoid giving bad news too soon,64 and fear saying the wrong thing.64 They seek to give an understanding of the severity of the illness,54 including the risk of sudden death,53 but struggle to balance frightening patients with underplaying their condition.51 The ethical balance between beneficence and non-malificence can be hard to find. Discomfort with breaking bad news,53,56,62 or with broader issues of death and dying hinders communication.61,62,64,68

Clinicians believe some heart failure patients do not wish to know they are dying,68 or are unsure whether patients wish to talk about death, recognising that they may be uncertain how to show to their doctors that they want to talk.62 Some see it as inappropriate for the doctor to initiate EOLC discussions,51,56 and ‘use their own judgement’ about what information patients may or may not want to hear and when;51 in practice this commonly means waiting for patients to initiate a conversation, although they recognise that some, especially older people, may be reluctant to raise such issues with their doctors.51 Rather than a one-off conversation, this is seen as a process over time, based on an established and trusting relationship between doctor and patient.51

Some clinicians see a ‘good death’ in heart failure in terms of open awareness, and the patient understanding what is happening and being able to plan ahead and talk about their wishes.61,62 A ‘bad death’ is unexpected, where health professionals have not been open about what is happening, and the patient has no insight and is therefore unprepared.61 There is concern that cardiologists may not always provide good palliative care and that palliative care clinicians may not have the skills to manage end-stage heart failure:56,64 joint working of these two specialist teams is welcomed.55,68

Healthcare professionals' preferences for the timing of discussions

There is real difficulty for professionals in judging the right time to hold these conversations. Some prefer to discuss early in the course of heart failure before the patient becomes too unwell to assimilate the information and make plans.61,68 Others are concerned about giving bad news too soon,64 although they acknowldge that they often accept and discuss the poor outlook too late for effective communication and planning.64 Many wait for patients to give cues that they wish to talk,51,53,56,62 preferring to respond to patient questions rather than initiate conversations themselves. The preference of many patients to wait for doctors to raise these issues is thus an ineffective strategy, as they very rarely do so.71

Barriers to end-of-life care conversations

The literature evidences a number of barriers to effective and timely EOLC conversations between people living with heart failure and their clinicians.

Understanding of their condition: patients in the dark

Many patients have little understanding of heart failure;53,55,60 they rarely use the term, usually using more vague words associated with old age,50 or their other comorbid conditions.51,74 Some are content with a small amount of knowledge, preferring to leave medical issues to doctors.50 Many have an erroneous view of heart failure as a benign condition compared to cancer,56,72 have unrealistic hopes of survival,50,61 do not understand their poor prognosis,50,72 or are reluctant to accept that no further intervention is appropriate.61 Clinicians may find establishing the diagnosis difficult, especially in primary care;51 they struggle to find appropriate language to explain the condition to patients, wishing to protect them from the negative connotations and anxiety of the term ‘failure’.51,54 Euphemisms may be used,51,53 which some patients appreciate.63 Professionals may be reluctant to acknowledge the terminal nature of heart failure,61 focusing on medical aspects of treatment rather than broader and longer-term issues.55,62

Unpredictability of the future: patients living with uncertainty

Clinicians find these conversations challenging as the future is so uncertain. They view providing an accurate prognosis as very difficult, if not impossible,51,54,55,56,62,64 given the unpredictability of heart failure, that many patients are older and may die from other comorbid conditions,51 and the risk of sudden death.62

Anxiety-provoking conversations: patients fear discussing end-of-life care

Some patients are aware of the poor prognosis associated with heart failure but elect not to talk about the end of life, fearing generating anxiety and loss of hope.50,51,52,56,66 Clinicians are similarly reluctant to raise end-of-life issues for fear of causing unnecessary worry early in the illness,51,56 or loss of hope,51 especially given the lack of EOLC services for non-cancer patients.54

Professional–patient communication: disempowered patients

Patients see good professional communication skills as very important,53,63 although many professionals, including those working in cardiology, feel they lack the skills needed.56,68 Patients value a good relationship with their clinicians,53,55 and personal continuity of care;51,52 long-term relationships with patients are also valued by clinicians,51 as they afford awareness of the ground covered in previous conversations.53,55,68

Professional time pressures are seen by patients52,60,63 and clinicians55,68 as limiting the potential for conversations. Patients often feel disempowered, finding clinicians unapproachable53,63 and reluctant to give information:66 they may see questions about prognosis as taboo,63 be reluctant to ask questions,50 especially if older,51 be unsure what questions to ask,55,66 be afraid to ‘put the doctor on the spot’,63 and fear being seen as difficult, demanding, or complaining.53,60 Some hesitate to visit a doctor, fearing unwelcome and unwanted hospital admission,60 or find themselves too fatigued and unwell to be able to concentrate and absorb information.55,63,66

The consequence: a conversation that rarely takes place

Both patients and clinicians wait for the other to open up EOLC conversations. Patients prefer to wait for clinicians to raise these issues;71 very few initiate these discussions themselves.71 Clinicians prefer to wait for patients to ask questions,53,56 and report that they are happy to talk in those circumstances,56 although finding it difficult to judge how much the patient wants to know.51,62 Consequently, patients are left with their questions in a state of uncertainty,55 frequently understanding that they are approaching the end of life but rarely discussing that with their clinicians.67

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

Conversations between clinicians and patients with heart failure focus largely on disease management; EOLC is rarely discussed. While some patients would welcome such conversations, many do not realise the seriousness of their condition or wish to discuss EOL issues. Clinicians are often unsure how to discuss with heart failure patients their uncertain prognosis and risk of sudden death and fear causing premature alarm and destroying hope. Clinicians wait for cues from patients before raising EOLC issues, while patients commonly wait for clinicians to raise these issues: as a result, the conversations rarely take place: ‘the elephant on the table’ is not addressed.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This is the first systematic review to synthesise the literature concerning patients' and clinicians' views of EOLC discussions in heart failure. Knowledge in this area is recent: no paper published before 1999 was identified. While the search strategy was difficult to create, it appears to have been effective: searching reference lists and citations of included papers and hand searches of two key journals did not identify any additional papers included in the synthesis. Most of the included studies were qualitative: the smaller number of quantitative studies were given a lower weight of evidence, being retrospective or limited data being available from routine sources such as medical records. We did not search the grey literature but have set the synthesis in the context of policy documents and guidelines.

Of the 23 papers, thirteen report data from patients, six from health professionals and four from both groups. The uniform view of patients is that these conversations occur rarely, if at all. Two medical record review studies report frequent occurrence of conversations. One revealed little EOLC content.64 The other supplied little content information beyond records indicating ‘advanced planning discussions and preferred place of death’,65 supplemented by clinician recall some months after the death: this paper was given the lowest weight of evidence scoring. As previously noted, there is a large discrepancy between doctors' and patients' reports of whether EOLC conversations have taken place at all and the amount of information given,43,44,46,49 an issue that would benefit from further research.

Comparison with existing literature

The classic work on ‘Awareness Contexts'77 that Glaser and Strauss developed with cancer patients near the EOL gives a useful structure for understanding the communication challenges facing heart failure patients and their clinicians.

Many patients are in Closed Awareness. They do not understand the nature and severity of the term ‘heart failure’, which they often understand in terms of ageing processes or co-morbid conditions. Thoughts of approaching death are simply not part of their reality of living with heart failure.69 Some have survived being close to death during resuscitation or exacerbations and do not see why they should not do so in the future. Their clinicians are aware of the poor prognosis but avoid the difficult conversations, in a way that has been described as reminiscent of cancer care decades ago.66

Others are in Suspicion Awareness, wanting to ask questions about the future, but feeling unable to do so.55

Mutual Pretence, where both patients and clinicians are aware of the poor outcome but avoid discussing it, is perhaps less common since many patients have poor understanding of their condition.

Open Awareness, where open conversations concerning EOLC occur, also appears to be rare in heart failure. Largely shaped by a cancer care model, this is the ideal situation set out in the NHS EOLC Strategy, but appears to be of limited applicability in heart failure.52

Implications for policy and practice

Recent years have seen dramatic therapeutic advances in the management of heart failure that have significantly improved patients' survival and quality of life: in the interventionist culture of Cardiology, there is a danger that issues of EOLC are only considered too late in the illness, when active options have been exhausted. Although many clinicians believe they should discuss the deactivation of implantable defibrillators with patients, in practice they find these conversations particularly difficult and rarely do so.48,75,76 As EOLC comes to the fore across the NHS, there is a growing tension between active management and the need to communicate an uncertain and poor prognosis: a double message that is difficult for clinicians to communicate and for patients to receive.

This review addresses a number of the recommendations of recent guidelines and policy documents concerning EOLC in heart failure, which may be summarised thus:

What? It is recommended that patients with heart failure and their carers should have sufficient opportunities to discuss their uncertain prognosis, the risk of sudden death and their priorities and preferences for care.18,38 A balance of optimism and realism is recommended78,79 avoiding either embracing or negating hope, but acknowledging the uncertainty.80 Some patients may be confused by what appears to be a mixed message and find the emotional and cognitive dissonance involved difficult.78 This review indicates that in practice many patients do not have these discussions49,51–63 despite some indicating a wish to do so49,55,60,63,65,66The uncertainty of prognosis51,53,71–72 and fear of causing patients anxiety51,54 are major barriers.

When? These conversations are recommended to be offered at all stages of the disease trajectory18, 38 as a process of continuing dialogue over time38,79–80 at times of the patient's own choosing,38 at key turning points79 such as decline in performance or episodes of decompensation,81 or when needed to plan care.82 In practice it is very difficult to judge when the time is right: some do not feel able to hold these discussions when unwell61,67,69 while others prefer not to consider these issues when well.67

How? Communication should be open, sensitive and honest, at the patient's own pace,38 using an ‘ask, tell, ask’ approach82,83 where the patient's desire for information is first elicited, followed by small amounts of information given at one time, then checking their understanding and desire to talk further. The communication challenges are formidable, especially in the light of sudden death in half of patients; these are advanced communication skills, honed by training and experience. Further research is called for concerning how to best elicit patients' desire for information and for participation in decision-making.79 In practice, many clinicians do not feel they have the necessary communication skills for these conversations.56,73

Who? Conversations should be held with a clinician with whom there is an established relationship and who has a commitment to personal continuity of care, as a process over time.81 Such conversations are the remit of a senior member of the heart failure team or the patient's GP. The study would argue that it is inappropriate for medical staff unfamiliar to the patient to tell the patient that they cannot predict what will happen next, apart from it is likely to be bad, including sudden death. In practice, this frequently occurs.53,55,73

Many still think of palliative care in terms of a system of care delivery involving specialists, referrals and hospices: it is rather a philosophy and approach to care involving supporting patients throughout their illness to the EOL. Such care is delivered by many health and social care professionals,84 although often not recognised as such. In practice, while the heart failure team are often involved around the time of diagnosis or admission for exacerbation,4 their focus is on medical management more than longer-term issues, and they rarely follow up patients long-term, especially older people with other comorbidities. In many cases the GP might be the most appropriate person, given the long-term doctor – patient relationships in primary care, although it must be admitted that this rhetoric of personal continuity of care has been a declining reality over recent years. The heart failure reviews in the Quality and Outcomes Framework for general practice focus on drug management issues and do not include longer term and EOL planning.

The role of palliative care specialists remains unclear85 and is often reserved for those with complex problems or poorly managed symptoms20,86 or at the time of admission with an acute exacerbation.87 Models of joint working have been developed88,89 commonly with the heart failure nurse as the lead clinician with palliative care consultancy90 rather than heart failure orientated palliative care.91 A recent survey found that although 90% of palliative care services say they accept heart failure patients, few have developed services of significant size:89 only 6% of patients in the National Heart Failure Audit were referred to palliative care.4

Clinicians are unsure how to discuss the uncertain prognosis and risk of sudden death, and fear causing premature alarm and undermining hope. ‘It is humane and sufficient in some cases to allow patients to be unaware of the serious nature of their condition … and not to harm patients by providing stressful information that is not requested’.50 Although such an approach may be consistent with the bioethical principles of beneficence and non-malificence, it conflicts with the principle of autonomy which recognises the patient's right to make informed choices about their care. When conversations about the future do take place, they focus more on issues of disease management than EOLC. Patients who wish to talk wait for their doctors to raise EOLC issues, while clinicians wait for cues from patients before raising these topics. The consequence is that ‘the elephant in the room’92 is rarely addressed in practice.

Conclusion

Heart failure patients need clinicians to be sensitive to their individual wishes for EOLC conversations, which change as events and time unfolds. Clinicians who tend to avoid such difficult conversations need to learn to pick up the cues that the patient would like to talk further. Those who view open awareness as the best way to prepare for the EOL need to live with the internal tensions created71 when patients are reluctant to discuss this. A dual approach of continuing active treatment while acknowledging the possibility of death, at least to ourselves, is perhaps the way forward: ‘hoping for the best but preparing for the worst’.78

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the comments of James Beattie, Angie Rogers and Jonathan Silverman on an earlier draft.

Funding body

Stephen Barclay is funded by Macmillan Cancer Support and this study was funded by Macmillan Cancer Support (through its Research Capacity Development Programme) and the NIHR CLAHRC (Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care) for Cambridgeshire and Peterborough. The opinions expressed are those of the authors not the funders.

Ethics committee

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have stated that there are none.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Lehman R, Doust J, Glasziou P. Cardiac impairment or heart failure? BMJ. 2005;331(7514):415–416. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7514.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roger V, Weston S, Redfield M, et al. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA. 2004;292(3):344–350. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowie M, Wood D, Coats A, et al. Incidence and aetiology of heart failure; a population-based study. Eur Heart J. 1999;20(6):421–428. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NHS Information Centre. National heart failure audit 2010. Leeds: National Clinical Audit Support Programme; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez KL, Appelt CJ, Switzer GE, et al. Veterans' decision-making preferences and perceived involvement in care for chronic heart failure. Heart Lung. 2008;37(6):440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson H, Ward C, Eardley A, et al. The concerns of patients under palliative care and a heart failure clinic are not being met. Palliat Med. 2001;15(4):279–286. doi: 10.1191/026921601678320269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart S, McMurray J. Palliative care for heart failure. BMJ. 2002;325(7370):915–916. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics — 2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119(3):480–486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkpatrick JN, Guger CJ, Arnsdorf MF, Fedson SE. Advance directives in the cardiac care unit. Am Heart J. 2007;154(3):477–481. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.London Heart Failure Study. Survival after initial diagnosis of heart failure, around 2002. London: British Heart Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orn S, Dickstein K. How do heart failure patients die? Eur Heart J. 2002;4(suppl D):59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levenson J, McCarthy E, Lynn J, et al. The last six months of life for patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 suppl):S101–S109. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleland J, Chattopadhyay S, Khand A, et al. Prevalence and incidence of arrhythmias and sudden death in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2002;7(3):229–242. doi: 10.1023/a:1020024122726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solano J, Gomes B, Higginson I. A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(1):58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pattenden J, Roberts H, Lewin R. Living with heart failure; patient and carer perspectives. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;6(4):273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2007.01.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health. National Service Framework for coronary heart disease. London: Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Addington-Hall J, Gibbs J. Heart failure now on the palliative care agenda. Palliat Med. 2000;14(5):361–362. doi: 10.1191/026921600701536183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Management of chronic heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blue L, Lang E, McMurray J, et al. Randomised controlled trial of specialist nurse intervention in heart failure. BMJ. 2001;323(7315):715–718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7315.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.NHS Modernisation Agency. Supportive and palliative care for advanced heart failure. Leicester: NHS Modernisation Agency; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Improving supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Department of Health. End of life care strategy: promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London: Department of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lunney J, Lynn J, Foley J, et al. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289(18):2387–2392. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray S, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ. 2005;330(7498):1007–1012. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gott M, Barnes S, Parker C, et al. Dying trajectories in heart failure. Palliat Med. 2007;21(2):95–99. doi: 10.1177/0269216307076348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barclay S, Case-Upton S. Knowing patients' preferences for place of death: how possible or desirable? Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(566):642–643. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X454052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers A, Addington-Hall JM, McCoy AS, et al. A qualitative study of chronic heart failure patients' understanding of their symptoms and drug therapy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002;4(3):283–287. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(01)00213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buetow S, Coster G. Do general practice patients with heart failure understand its nature and seriousness, and want improved information? Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45(3):181–185. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horowitz C, Rein S, Leventhal H. A story of maladies, misconceptions and mishaps: effective management of heart failure. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(3):631–643. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00232-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanders T, Harrison S, Checkland K. Evidence-based medicine and patient choice: the case of heart failure care. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008;13(2):103–108. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2008.007130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stuart B. The nature of heart failure as a challenge to the integration of palliative care services. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2007;1(4):249–254. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3282f283b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fitzsimons D, Mullan D, Wilson J. The challenge of patients' unmet palliative care needs in the final stages of chronic illness. Palliat Med. 2007;21(4):313–322. doi: 10.1177/0269216307077711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barnes S, Gott M, Payne S, et al. Predicting mortality among a general practice-based sample of older people with heart failure. Chronic Illn. 2008;4(1):5–12. doi: 10.1177/1742395307083783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buetow S, Goodyear-Smith F, Coster G. Coping strategies in the self-management of chronic heart failure. Fam Pract. 2001;18(2):117–122. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hancock K, Clayton J, Parker S, et al. Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2007;21(6):507–517. doi: 10.1177/0269216307080823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zapka J, Moran W, Goodlin S, Knott K. Advanced heart failure: prognosis, uncertainty, and decision making. Congest Heart Fail. 2007;13(5):268–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2007.07184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hunt S, Abraham W, Chin M, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Guideline Update for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Heart Failure in the Adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2005;112(12):e154–e235. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.167586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scottish Partnership for Palliative Care and British Heart Foundation Scotland. Living and dying with advanced heart failure: a palliative care approach. Edinburgh: Scottish Partnership for Palliative Care and British Heart Foundation Scotland; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song M. Effects of end-of-life discussions on patients' affective outcomes. Nurs Outlook. 2004;52(3):118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tierney W, Dexter P, Gramelspacher G, et al. The effect of discussions about advance directives on patients' satisfaction with primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(1):32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golin C, Wenger N, Liu H, et al. A prospective study of patient-physician communication about resuscitation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 suppl):S52–S60. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoffman J, Wenger N, Davis R, et al. Patient preferences for communication with physicians about end-of-life decisions. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preference for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(1):1–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-1-199707010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fried TR, Bradley EH, O'Leary J. Prognosis communication in serious illness: perceptions of older patients, caregivers, and clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(10):1398–1403. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DesHarnais S, Carter RE, Hennessy W, et al. Lack of concordance between physician and patient: reports on end-of-life care discussions. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(3):728–740. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cherlin E, Fried T, Prigerson H, et al. Communication between physicians and family caregivers about care at the end of life: when do discussions occur and what is said? J Palliat Med. 2005;8(6):1176–1185. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hancock K, Clayton J, Parker S, et al. Discrepant perceptions about end-of-life communication: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(2):190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(1):81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beattie J, Connolly M, Ellershaw J. Deactivating implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(9):690. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-9-200511010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agard A, Hermeren G, Herlitz J. Should cardiopulmonary resuscitation be performed on patients with heart failure? The role of the patient in the decision-making process. J Intern Med. 2000;248(4):279–286. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agard A, Hermeren G, Herlitz J. When is a patient with heart failure adequately informed? A study of patients' knowledge of and attitudes toward medical information. Heart Lung. 2004;33(4):219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barnes S, Gott M, Payne S, et al. Communication in heart failure: perspectives from older people and primary care professionals. Health Soc Care Community. 2006;14(6):482–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gott M, Small N, Barnes S, et al. Older people's views of a good death in heart failure: implications for palliative care provision. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(7):1113–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boyd K, Murray S, Kendall M, et al. Living with advanced heart failure: a prospective, community based study of patients and their carers. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6(5):585–591. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murray S, Boyd K, Kendall M, et al. Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. BMJ. 2002;325(7370):929–932. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harding R, Selman L, Beynon T, et al. Meeting the communication and information needs of chronic heart failure patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(2):149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Selman L, Harding R, Beynon T, et al. Improving end of life care for patients with chronic heart failure: ‘let's hope it'll get better when I know in my heart of hearts it won't’. Heart. 2007;93(8):963–967. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.106518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ritchie J, Spencer L, O'Connor W. Carrying out qualitative analysis. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, editors. Qualitative research practice. A guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage; 2006. pp. 219–262. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Petticrew P, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gough D. Furlong J, Oancea A, Weight of evidence: a framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence, editors. Applied and practice-based research. Special edition of Research Papers in Education. 2007;22(2):213–228. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aldred H, Gott M, Gariballa S. Advanced heart failure: impact on older patients and informal carers. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49(2):116–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Borbasi S, Wotton K, Redden M, Chapman Y. Letting go: a qualitative study of acute care and community nurses' perceptions of a ‘good’ versus a ‘bad’ death. Aust Crit Care. 2005;18(3):104–113. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brannstrom M, Brulin C, Norberg A, et al. Being a palliative nurse for persons with severe congestive heart failure in advanced home care. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;4(4):314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caldwell P, Arthur H, Demers C. Preferences of patients with heart failure for prognosis communication. Can J Cardiol. 2007;23(10):791–796. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(07)70829-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hanratty B, Hibbert D, Mair F, et al. Doctors' perceptions of palliative care for heart failure: focus group study. BMJ. 2002;325(7364):581–585. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7364.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Horne G, Payne S. Removing the boundaries: palliative care for patients with heart failure. Palliat Med. 2004;18(4):291–296. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm893oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rogers A, Addington-Hall J, Abery A, et al. Knowledge and communication difficulties for patients with chronic heart failure: qualitative study. BMJ. 2000;321(7261):605–607. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7261.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Strachan P, Ross H, Rocker G, et al. Mind the gap: opportunities for improving end-of-life care for patients with advanced heart failure. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25(11):635–640. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(09)70160-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wotton K, Borbasi S, Redden M. When all else has failed. Nurses' perception of factors influencing palliative care for patients with end-stage heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;20(1):18–25. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Formiga F, Chivite D, Ortega C, et al. End-of-life preferences in elderly patients admitted for heart failure. Q J Med. 2004;97(12):803–808. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hch135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Haydar Z, Lowe A, Kahveci K, et al. Differences in end-of-life preferences between congestive heart failure and dementia in a medical house calls program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):736–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Heffner J, Barbieri C. End of life preferences for patients enrolled in heart failure rehabilitation programmes. Chest. 2000;117(5):1474–1481. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Willems D, Hak A, Visser F, van der Wal G. Thoughts of patients with advanced heart failure on dying. Palliat Med. 2004;18(6):564–572. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm919oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson M, Parsons S, Raw J, et al. Achieving preferred place of death — is it possible for patients with chronic heart failure? Br J Cardiol. 2009;16:194–196. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rodriguez K, Appelt C, Switzer G, et al. ‘They diagnosed bad heart’: a qualitative exploration of patients' knowledge about and experiences with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2008;37(4):257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goldstein N, Bradley E, Zeidman J, et al. Barriers to conversations about deactivation of implantable defibrillators in seriously ill patients: results of a nationwide survey comparing cardiology specialists to primary care physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(4):371–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goldstein N, Mehta D, Teitelbaum E, et al. ‘It's like crossing a bridge’ complexities preventing physicians from discussing deactivation of implantable defibrillators at the end of life. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(suppl 1):2–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0237-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Glaser B, Strauss A. Awareness of dying. London: Widenfield and Nicholson; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Back A, Arnold R, Quill T. Hope for the best, and prepare for the worst. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(5):439–443. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-5-200303040-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goodlin SJ, Hauptman PJ, Arnold R, et al. Consensus statement: Palliative and supportive care in advanced heart failure. J Card Fail. 2004;10(3):200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Davidson P. Difficult conversations and chronic heart failure: do you talk the talk or walk the walk? Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 1(4):274–278. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3282f3475d. 207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goodlin SJ. End-of-life care in heart failure. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2009;11(3):184–191. doi: 10.1007/s11886-009-0027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goodlin SJ, Quill TE, Arnold RM. Communication and decision-making about prognosis in heart failure care. J Card Fail. 2008;14(2):106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Silverman J, Kurtz S, Draper J. Skills for communicating with patients. 2nd edn. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shipman C, Gysels M, White P, et al. Improving generalist end of life care: a national consultation with practitioners, commissioners, academics and service user groups. BMJ. 2008;337(848):851. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Albert N. Referral for palliative care in advanced heart failure. Prog Palliat Care. 2008;16(5–6):220–228. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jaarsma T, Beattie JM, Ryder M, et al. Palliative care in heart failure: a position statement from the palliative care workshop of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11(5):433–443. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Widera E, Pantilat S. Hospitalization as an opportunity to integrate palliative care in heart failure management. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2009;3(4):247–251. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283325024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Johnson MJ, Houghton T. Palliative care for patients with heart failure: description of a service. Palliat Med. 2006;20(3):211–214. doi: 10.1191/0269216306pm1120oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gibbs L, Khatri K, Gibbs J. Survey of specialist palliative care and heart failure: September 2004. Palliat Med. 2006;20(603):609. doi: 10.1177/0269216306071063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Daley A, Matthews C, Williams A. Heart failure and palliative care services working in partnership: report of a new model of care. Palliat Med. 2006;20(6):593–601. doi: 10.1177/0269216306071060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.O'Leary N. The comparative palliative care needs of those with heart failure and cancer patients. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2009;3(4):241–246. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e328332e808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Quill T. Perspectives on care at the close of life. Initiating end-of-life discussions with seriously ill patients: addressing the ‘elephant in the room’. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2502–2507. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]