Abstract

Magnetic nanoparticles are promising molecular imaging agents due to their relative high relaxivity and the potential to modify surface functionality to tailor biodistribution. In this work we describe the synthesis of magnetic nanoparticles using organic solvents with organometallic precursors. This method results in nanoparticles that are highly crystalline, and have uniform size and shape. The ability to create a monodispersion of particles of the same size and shape results in unique magnetic properties that can be useful for biomedical applications with MR imaging. Before these nanoparticles can be used in biological applications, however, means are needed to make the nanoparticles soluble in aqueous solutions and the toxicity of these nanoparticles needs to be studied.

We have developed two methods to surface modify and transfer these nanoparticles to the aqueous phase using the biocompatible co-polymer, Pluronic F127. Cytotoxicity was found to be dependent on the coating procedure used. Nanoparticle effects on a cell-culture model was quantified using concurrent assaying; a LDH assay to determine cytotoxicity and an MTS assay to determine viability for a 24 hour incubation period. Concurrent assaying was done to insure that nanoparticles did not interfere with the colorimetric assay results.

This report demonstrates that a monodispersion of nanoparticles of uniform size and shape can be manufactured. Initial cytotoxicity testing of new molecular imaging agents need to be carefully constructed to avoid interference and erroneous results.

Keywords: MRI, molecular imaging, nanoparticles, superparamagnetic agents, cytotoxicity, Colorimetric Assay, Pluronics

1. Introduction

1.1 Iron oxide nanoparticles as molecular imaging agents

Magnetic nanoparticles have magnetic moments more than three orders of magnitude larger than paramagnetic contrast enhancers (1). Contrast is a result of spin-spin dephasing caused by local inhomogeneities in the magnetic field due to the magnetic moment of each nanoparticle (2). The magnetic behavior depends on the properties of the individual particles (size, crystallinity and composition) and surface properties (hydrodynamic volume and chemistry) (3). Polydispersity in any of these parameters results in magnetic properties that are diffuse, with poor reproducibility and difficult to fully characterize and model.

Commercially available molecular imaging agents, such as Feridex, are synthesized via the co-precipitation of iron salts. Because the synthesis occurs entirely in the aqueous phase, surface modification and biological use are straightforward. However, control of individual particle size and shape is difficult and these particles are still prone to a high degree of agglomeration (4,5). Thus, with this synthesis method, it is common to use a size selection process to remove agglomeration and narrow the size distribution (6-8).

In this work iron oxide nanoparticles are synthesized by a different technique involving the thermal decomposition of organometallic precursors (9,10). This synthesis route results in highly crystalline, structurally/chemically uniform nanoparticles of tailorable size. These particles have been extensively characterized and have been shown to be a crystalline magnetite of high phase purity, with narrow dispersion in size and shape (9). Additionally, this synthesis method allows for the growth of nanoparticles with non-spherical geometry such as disks and rods (11) with a shape component to the anisotropy which could have unique behaviors when imaged with MRI.

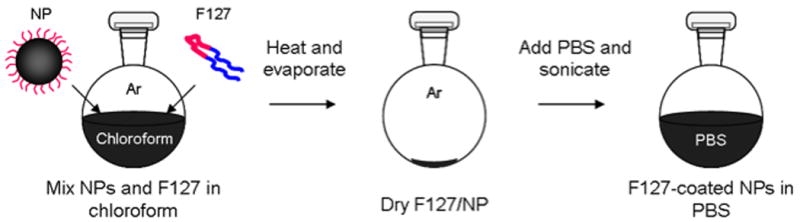

Surfactants, in this case oleic acid, mediate the growth of the nanoparticles, coat the surface of the nanoparticles and provide steric stabilization to prevent agglomeration. Even though the surfactant coating is beneficial, it also renders the nanoparticles insoluble in aqueous solutions thus limiting potential use. Before they can be used as molecular contrast agents, these nanoparticles need to be transferred to the aqueous phase. One approach to solubilize the nanoparticles is to use a surface co-polymer, Pluronic F127 (F127), which has been studied and used as a biological coating (12) and micellular drug-delivery vehicle (13-15). Two coating methods were developed and studied, a “wet” transfer and a “dry” transfer method. In the wet transfer method the nanoparticles remain suspended in solution and move from the non-polar phase to the aqueous phase where as in the dry transfer method the non-polar phase is completely removed and then the nanoparticles are redispersed in the aqueous medium.

To date the majority, if not all, of toxicity studies have been performed on iron oxide nanoparticles made from the co-precipitation of iron salts method (16-18). Very little toxicity (in vitro or in vivo) data has been collected for iron oxide nanoparticles made from the thermal decomposition of organometallics (19). Although both iron oxide and F127 have both been studied for use in vivo, this work illustrates that variation in the synthetic scheme at the phase transfer procedure can affect the in vitro cytotoxicity of the resulting coated nanoparticle.

1.2 Cytotoxicity of nanoparticles

Performing in vitro cytotoxicity characterization with nanoparticles is not straight forward (20-22). Depending on the nanoparticles and the assay used, possible interactions include: a) increasing apparent cell dosaging due to agglomeration and settling of nanoparticles in cell culture (23); b) erroneous increase or a decrease in cell viability due to nanoparticle interference with the development of colorimetric assays (24) and c) interference due to fluorescence or absorbance of nanoparticles at the same wavelength of the assay dye. Thus careful experimental design is necessary to assess potential nanoparticle interactions.

To detect interference of nanoparticles, complementary cytotoxicity assays were used in this study. Concurrent assays were performed on the same samples by separating cells and supernatant with viability assayed directly on cells and cytotoxicity assayed with the lactate released into the medium. Two tetrazolium salt based assays, (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt (MTS), in the presence of phenazine methosulfate (PMS) which measure mitochondrial activity, as well as resazurin were used to assay cell viability. A lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay was used to determine cytotoxicity via cell membrane integrity (25).

The objective of this report is to present initial in vitro cytotoxicity testing of iron oxide nanoparticles synthesized by thermal decomposition and phase transferred with two different coating methods.

2. Results and discussion

2.1 Nanoparticle preparation and characterization

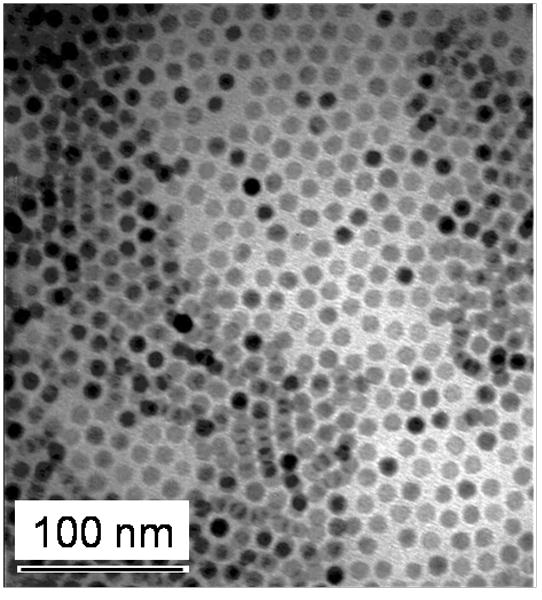

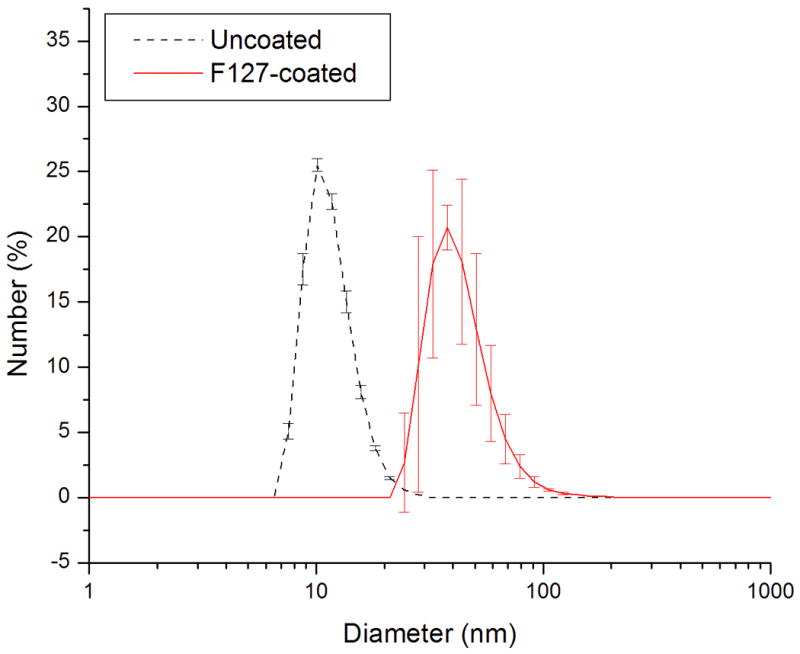

Nanoparticle size, shape and uniformity were characterized with Transmission Electron Microscopy (5) and Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). A TEM image of nanoparticles before phase transfer demonstrates that the nanoparticle cores are 9 nm in diameter [Figure 1]. The TEM image shows that the nanoparticles are spherical, non-agglomerated and uniform in size. DLS data shows the hydrodynamic diameter of these 9 nm nanoparticles before and after coating [Figure 2]. Prior to coating, nanoparticles have a hydrodynamic diameter of 11.3 nm where the difference in measured diameter can be attributed to the presence of the coating of oleic acid. The hydrodynamic diameter of phase transferred dialyzed and filter-sterilized nanoparticles increases to 37 nm and indicates that the nanoparticles are not agglomerated after coating.

Figure 1.

Transmission Electron Microscopy image of the nanoparticle cores. Synthesized iron oxide nanoparticle cores are spherical, non-agglomerated, and uniform in size with a diameter of 9 nm.

Figure 2.

Dynamic Light Scattering measurement of the nanoparticles before and after coating with Pluronic. With coating and aqueous phase transfer the hydrodynamic diameter of the particles have increased from 11.3 nm to 37.0 nm.

2.2 Cytotoxicity evaluation

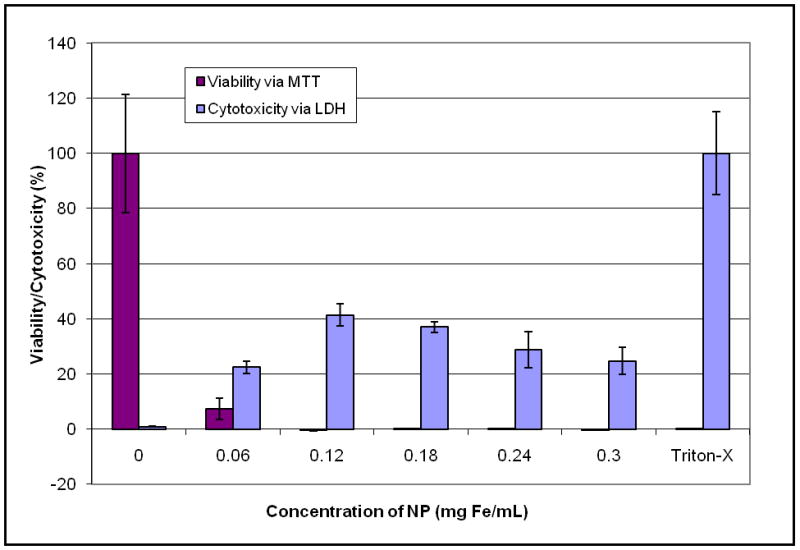

2.2.1 Cytotoxicity of wet transfer method with MTT and LDH

Visual inspection of cells (images not shown) showed only cell debris which suggested that use of the wet transfer method with the F127 coated nanoparticles coated with F127 was cytotoxic at all concentrations with all cells being non-viable at all nanoparticle concentrations greater than 0.06 mg Fe/mL. MTT assay indicated viability less than 10% for the 0.06 mg Fe/mL concentration of nanoparticles and close to 0% for higher concentrations [Figure 3]. LDH assay confirmed high toxicity of nanoparticles with cytotoxicity greater than 50% for all samples. The data suggests that all the cells were nonviable after exposure to the nanoparticles at the time of assay, thus the LDH assay performed similar to a cell count assay. The relationship to concentration indicates that at the highest concentration, the cells died more quickly and died more slowly with decreasing concentration. However for the 0.06 mg Fe/mL concentration, the measurements reveal that some cells were viable at the time of the assay resulting in lower cytotoxicity and a smaller value of viability as determined with the MTT assay. These results corresponded with visual inspection of the cell cultures.

Figure 3.

Wet transfer nanoparticle synthesis: Viability assessed with MTT and cytotoxicity assessed with LDH.

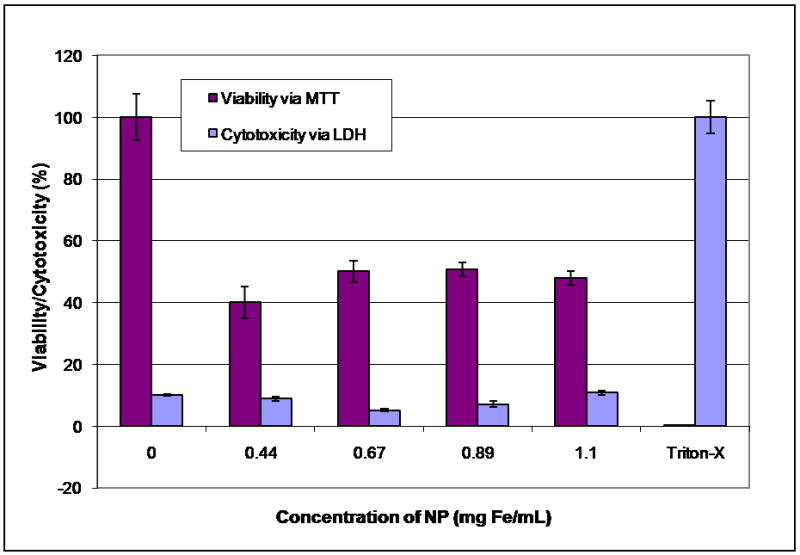

2.2.2 Cytotoxicity of dry transfer method with MTT and LDH

After a 24 hour incubation with nanoparticles, visual inspection of cells indicated that the cells were viable for all nanoparticle concentrations [Figure 4]. Concurrent LDH assay confirmed very little cytotoxicity (<10%) for all nanoparticle concentrations with membrane integrity similar to the negative control [Figure 5]. However, in contrast to visual inspection and the LDH assay, the MTT assay indicated a drop in viability of greater than 50% for all concentrations used, which did not follow a dose dependant relationship. The discrepancy between the MTT and the LDH assay results, visual inspection and lack of a dose-dependent response raised the possibility of suppressed viability measurement due to nanoparticle interference with the MTT assay.

Figure 4.

Dry transfer nanoparticle synthesis: Optical microscope images of cells after 24 hr incubation with nanoparticles and after 2 hr incubation with MTT.

Figure 5.

Dry transfer nanoparticle synthesis: Viability assessed with MTT and cytotoxicity assessed with LDH.

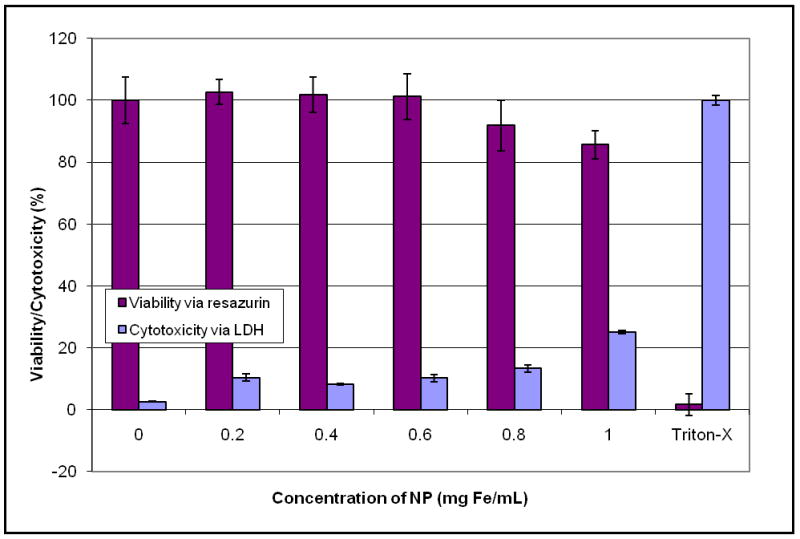

2.2.3 Cytotoxicity of dry transfer method with resazurin and LDH

Because of the possibility of nanoparticle interference with the MTT assay, the experiment was repeated with resazurin instead of the MTT assay. After a 24 hour incubation with nanoparticles, visual inspection of cells along with the viability and cytotoxicity results indicated low cytotoxicity [Figure 6]. Additionally, the complimentary assays correlate and exhibit a dose response, supporting the accuracy of these results. The slight difference between the LDH assays could indicate a difference in effective dosage due to nanoparticle settling out of solution and onto the cells.

Figure 6.

Dry transfer nanoparticle synthesis: Viability assessed with resazurin and cytotoxicity assessed with LDH.

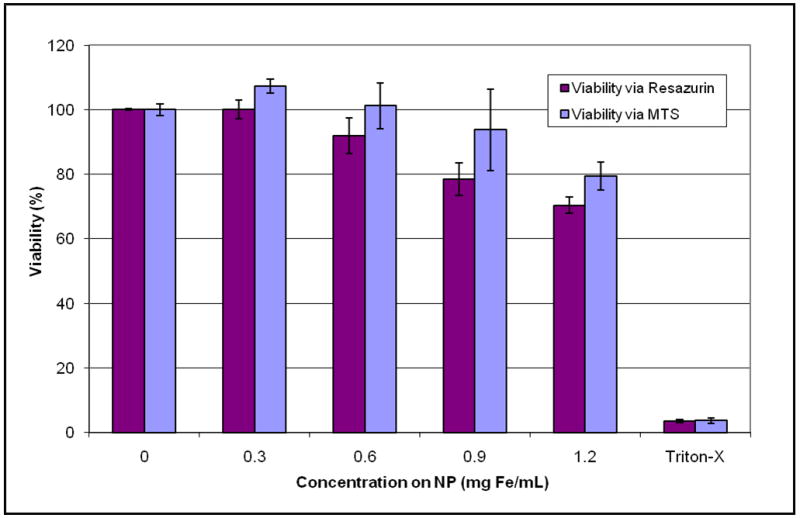

2.2.4 Viability of dry transfer method with resazurin and MTS

Resazurin and MTT do not measure cell viability in the same way; therefore resazurin cannot substitute for MTT. Resazurin interacts with the cell in ways not yet fully understood, while the MTT assay is based on the degree of mitochondrial activity. Therefore the MTS assay was also used. Like MTT, MTS measures mitochondrial activity, but it forms a water soluble dye. However the MTS and LDH assays cannot be used together exclusively. They both have absorbance peaks at similar wavelengths, leading both assays vulnerable to erroneous results if the nanoparticles being tested also have an absorption near the assay peak wavelength. In order to decouple possible effects on the mitochondria and absorbencies, the experiment was repeated and viability was confirmed by comparing the resazurin and MTS assays.

After a 24-hour incubation with nanoparticles, both the resazurin and MTS assays show a low, dose-dependent decrease in viability for all nanoparticle concentrations tested [Figure 7]. The results indicate that there is no nanoparticle interference with adsorption and that mitochondrial and overall cell viability is maintained. Slight increase in viability measured with the MTS assay may be due to increased mitochondrial activity associated with cell phagocytosis of nanoparticles.

Figure 7.

Dry transfer nanoparticle synthesis: Viability assessed with resazurin and MTS assays.

2.3. Discussion

Thermal decomposition of organometallics is a nanoparticle synthesis method that has the advantage of providing control over the size, shape, and resulting magnetic properties of the constructed nanoparticles. While enabling the creation of tailorable nanoparticles, the particles created by thermal decomposition are not initially dispersible in aqueous solutions and thus require a second synthesis step consisting of surface modification to generate a water-soluble particle. In this study, spherical nanoparticles created by thermal decomposition were coated with Pluronic F127 by two different surface modification methods (wet-transfer and dry-transfer methods) to generate water-soluble nanoparticles. The importance of cytotoxicity testing was demonstrated by the high in vitro cellular toxicity that occurred with the wet transfer method, but low toxicity found with the dry transfer method. Nanoparticles created with the dry transfer method were tested up to 1.2 mg Fe/mL for 24 hours, which is a greater concentration and higher incubation time than previously studied, 4.87E-4 mg Fe/mL at 1 and 24 hours (calculated from 100 nM for 9.6 nm Fe3O4 nanoparticles) (26).

Cytotoxicity measurements were originally designed for rapid and inexpensive analysis of soluble pharmaceuticals. They are also useful in the initial development of novel nanoparticle formulations. As these results demonstrate, the particular cytotoxicity assay selected could produce erroneous findings due to nanoparticle-assay interference, and thus careful experimental design is required to detect potential interactions. In this study, different assays were used to quantify cellular viability and cytotoxicity, which allowed the detection of an interaction between the nanoparticle and the MTT assay. The MTT assay requires the formation of a water-insoluble formazan crystal which can interact with various reagents (27). It is possible that the water-soluble nanoparticles created with the wet-transfer method interfered with the formation and growth of the formazan crystals, causing a suppression of the viability results. Since the MTT assay is a standard cell viability assay, this finding highlights the importance of considering the occurrence of unsuspected assay interactions when new nanoparticles and synthesis methods are being developed.

Cytotoxicity studies are a critical part of nanoparticle development. While the coating polymer and the nanoparticle materials are themselves individually non-toxic, the method of coating can greatly affect the cytotoxicity of the resulting coated-nanoparticle. Despite producing a similar water-soluble pluronic coated nanoparticle, the wet-transfer method of surface modification was found to be highly toxic to the cells tested. The difference in cell toxicity may possibly be due to a trapped non-polar solvent. On the other hand, the dry-transfer method was found to have a low degree of cellular toxicity. Further work is needed to clarify the exact cause of the difference in cellular toxicity observed between the two surface coating methods.

3. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the thermal decomposition and phase transfer with Pluronic F127 can be used to synthesis iron oxide nanoparticles that are of uniform size and soluble in aqueous solutions. Possible interactions and differences in the synthetic methods require the use of complimentary in vitro tests on the final coated particle to adequately assess cytotoxicity.

4. Materials and methods

4.1 Materials for nanoparticle synthesis

Iron pentacarbonyl (Sigma) was stored at 4°C and centrifuged prior to use. Oleic acid 99% (Sigma) was stored at -24°C. Trimethylamine N-oxide, TMANO, (Sigma) 98% was stored at room temperature. All chemicals were prepared for synthesis in an inert argon atmosphere. Cell culture tested F127 (Sigma), used for phase transferring, was stored at room temperature prior to use.

4.2 Preparation of iron oxide nanoparticles

Iron oxide nanoparticles are formed in a two-step process (9,10). In the first step, nanoparticles (FeO1-x) are formed via a surfactant-mediated thermal decomposition of an organometallic precursor. In the second step, the particles are oxidized and annealed to form highly crystalline iron oxide (Fe3O4). Particle size is controlled by varying the molar ratio of oleic acid to iron pentacarbonyl. To prepare the nanoparticles, oleic acid in 10 mL octyl ether was heated to 100°C. Iron pentacarbonyl (0.2 mL) was injected into the hot solution and allowed to reflux at 283°C. Nucleation was evident by a sharp darkening of the solution over a 30 second period. After nucleation, the solution was allowed to reflux for an additional 1.5 hours. The solution was cooled to room temperature and TMANO (0.34 mg) was added. The temperature of the solution was increased to 130°C and heated for 2 hours during which time the color of the solution turned from black to red. Afterwards, the temperature was increased and allowed to reflux for 1 hour during which time the color of the solution turned black. The solution was cooled to room temperature and nanoparticles stored in octyl ether until use. Prior to use the nanoparticles were washed three times with a mixture of chloroform, propanol and ethanol. Washing caused flocculation of nanoparticles which could be recovered as a black precipitate by centrifugation.

4.3 Phase transfer of iron oxide nanoparticles

Two coating procedures were developed for phase transferring. In the first method, nanoparticles and F127 remained dispersed in solution during the phase transfer and thus called the “wet” transfer method with preparation previously described (12). In the second method, nanoparticles and F127 are dried prior to the addition of the aqueous phase and thus called the “dry” transfer method. For the dry transfer method, nanoparticles (2 mL) were washed, redispersed in chloroform (4 mL) and sonicated for 10 minutes. Pluronic (80 mg) was added and mixed for 5 minutes. The mixture was used immediately for phase transfer. Nanoparticle/F127 solution (∼0.75 mL) was added to a 100 mL flask heated to 55°C under an argon atmosphere [Figure 8]. Chloroform was evaporated under an argon stream then vacuum dried for 5 minutes. PBS (0.5 mL) was added to the dry nanoparticles/F127 and briefly sonicated under an argon atmosphere to suspend the nanoparticles.

Figure 8.

Dry transfer procedure. Washed iron oxide nanoparticles are mixed with F127 in chloroform. In an argon atmosphere at 55°C the chloroform is evaporated. Pluronic-coated nanoparticles are suspended in PBS with a brief sonication.

To remove unconjugated Pluronic, F127-coated nanoparticles were dialyzed against PBS using a 25 kDa molecular weight cut off (MWCO) dialysis membrane (Spectra/Por 7) for 24 hours with one change of PBS. Dialyzed solutions were filter-sterilized with a sterile 0.2 μm Surfactant Free Cellulose Acetate (SFCA) filter (Corning) in a sterile atmosphere and stored at room temperature until use.

4.4 Characterization of nanoparticles

4.4.1 Particle size and size distribution

4.4.1.1 Transmission Electron Microscopy

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) was performed on a Phillips 420 operating at an accelerating voltage of 100 keV. TEM samples of uncoated nanoparticles were prepared by allowing a drop of solution to dry on a Formvar-coated carbon-type B grid (Ted Pella).

4.4.1.2 Dynamic Light Scattering

Malvern Zetasizer NanoS Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) machine was used to measure the hydrodynamic diameter of the nanoparticles in solution before and after coating. Phase-transferred samples were prepared by diluting ∼ 50 μL of F127-coated nanoparticle solution with ∼ 1 mL of filtered PBS and measured in disposable cuvettes. Intensity (%) data was converted and presented as Number (%). All measurements were performed twice with the average measurement value presented. Error is presented as ± one standard deviation.

4.4.2 Quantification of Fe concentration

Iron concentration (mg Fe/mL) of filter-sterilized phase transferred nanoparticles was measured with Inductively Coupled Plasma – Atomic Emission Spectrophotometer (ICP) (Jarell Ash 955). Samples were diluted and measured in the ICP, no further sample preparation was necessary because these samples contained iron oxide of nanometer diameter.

4.5 In vitro cytotoxicity testing

In this study the RAW 264.7 cell line, a mouse leukemic monocyte macrophage lineage, was used as the model system. Macrophages were chosen because of their phagocytotic nature (22) and their relevance to studies of atherosclerosis. Macrophages would also likely be among the first cells to interact with nanoparticles because of their role with the innate immune system.

Nanoparticles were incubated with cells for 24 hours after which time the cytotoxicity and viability were quantified with colorimetric assays (28-32).

4.5.1 Cell culture

RAW 264.7 cells, (ATCC, Manassas, Va), were grown in DMEM (Gibco BRL) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37°C in a 95% O2/5% CO2 humidified environment. Cells were grown in 75 cm2 tissue culture flasks and passaged approximately every two days up to 25 passages. For passage, cells were scraped from the surface of the flask, pelleted via centrifugation (250 g for 5 minutes) and resuspended in 10 mL of medium prior to counting with a hemacytometer. Passaged cells were then resuspended at a density of 1.5×106 cells/75cm2 flask.

4.5.2 Solutions and reagents

To prevent interference with colorimetric measurements, Phenol Red-free RPMI-1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) with 1% L glutamine, 10 % heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin (100 U/mL)/streptomycin (100 μg/mL) was used. Dialyzed and filter-sterilized F127-coated nanoparticle solution was heated to 32°C and diluted with 1 × PBS and Phenol Red-free medium to achieve working concentrations. A 1% Triton-X solution was prepared with DI water, filter-sterilized and stored at room temperature.

4.6 Evaluation of cell viability with colorimetric assays

4.6.1 Concurrent concentration assays

The MTS assay (Promega's CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay) was used as is, stored in the dark at -20 °C and thawed prior to use. For the MTT assay, a 5 mg/mL MTT solution was prepared by mixing MTT salts (Sigma-Aldrich) with 1 × PBS. MTT solution was stored in the dark at 4°C. A formazan release and solubilizing solution was a mixture of 12.5% glycine buffer (0.1 M glycine, 0.1 M NaCl pH 10.5) with DMSO prepared at time of use. The resazurin assay (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as is, stored in the dark at 4°C and warmed to room temperature prior to use. LDH kit was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. LDH reaction mixture was prepared immediately prior to use following the Sigma TOX-7 kit instructions.

Cell plating layout was designed to allow for viability and cytotoxicity studies by incorporating a positive viability control (nanoparticle-free) and a positive cytotoxicity control (nanoparticle-free). Four dilutions of nanoparticles were used for each experiment. To account for any possible absorbance by the nanoparticles, a cell-free control was prepared for each dilution of nanoparticle. Each well was initially plated with 100 μL/well of cells at 3 × 105 cells/mL in triplicate in 96-well plates. At this concentration the cells were in the log phase of growth at the time of the assay. Cells were grown for 24 hours to allow for cell recovery and adherence. After 24 hours the medium in the wells containing cells and the cell-free wells was removed and replaced with medium containing nanoparticles. The medium in the controls was replaced with Phenol Red-free medium. Cells were allowed to grow for 24 additional hours after which viability and cytotoxicity assays were performed.

4.6.2 Preparing the cytotoxicity control

To prepare the positive cytotoxicity control, the medium was removed and replaced with 100 μL of 1% Triton-X solution from the positive cytotoxicity controls and the corresponding cell-free well. The plate was left for 5 – 10 minutes at room temperature to allow for complete lysing of cells.

4.6.3 Collecting supernatant for LDH

Supernatant (75 μL) was collected from each well and placed in vials and stored at 4°C for the LDH assay.

4.6.4 Viability with MTT, MTS and resazurin

The remainder of the supernatant was removed. Fresh Phenol Red – free medium (100 μL) was added to each well. Either MTT (25 μL), MTS (20 μL) or resazurin (10 μL) was added to each well including controls and cell-free wells. Assays were allowed to develop for 2 hours in the incubator. Both the MTS and resazurin needed no further processing before reading, however the MTT required solubilization.

For MTT solubilization the medium was removed from all wells. DMSO (100 μL) and glycine buffer (25 μL) was added to each well to cause cell membrane rupture and formazan salt solubilization.

4.6.5 Cytotoxicity with LDH

The collected supernatant was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 700 g to remove cell debris and some nanoparticles. Supernatant (50 μL) was plated in a second 96-well plate preserving the plating configuration. LDH solution (100 μL) was added to each well including controls and cell-free wells. The plate was allowed to develop for 20 minutes in the dark at room temperature and required no further processing before reading.

4.7 Calculation of results

Absorbance was measured with a SPECTRAmax M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices) and data collected with SoftMax Pro 4.6 software. All data was first normalized by subtracting the background absorbance values for each well. Viability with the MTT and MTS was determined for each well by subtracting the normalized absorbance (for MTT: absorbance measured at 570 nm – absorbance measured at 680 nm, for MTS: absorbance measured at 490 nm – absorbance measured at 680 nm) of wells containing nanoparticles but no cells from the normalized absorbance of wells containing nanoparticles and cells. Relative viability was determined by normalizing by the positive viability control (cells with 0 mg Fe/mL).

Viability with the resazurin was determined as the decrease in absorbance at 600 nm. The normalized absorbance (absorbance measured at 600 nm – absorbance measured at 570 nm) of wells containing nanoparticles and cells was subtracted from the normalized absorbance of the wells containing nanoparticles but no cells. Relative viability was determined by normalizing against the positive viability control (cells with 0 mg Fe/mL).

Cytotoxicity with LDH was determined by subtracting the normalized absorbance (absorbance measured at 490 nm – absorbance measured at 680 nm) of the cell-free wells from the normalized absorbance of wells with cells. Relative cytotoxicity was determined by normalizing against the positive cytotoxicity control (cells with no nanoparticles incubated with 1% Triton-X).

The results have been presented with mean standard deviations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NSF/DMR #0501421, by the Campbell Endowment at UW and the National Physical Science Consortium. The authors would like to thank Dr. Stephan T. Stern, Ph.D. from the Nanotechnology Characterization Lab for useful conversations regarding the nanoparticle interaction with cell culture experiments.

References

- 1.Bowen CV, Zhang X, Saab G, Gareau PJ, Rutt BK. Application of the static dephasing regime theory to superparamagnetic iron-oxide loaded cells. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48(1):52–61. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood ML, Hardy PA. Proton relaxation enhancement. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1993;3(1):149–156. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880030127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fahlvik AK, Klaveness J, Stark DD. Iron oxides as MR imaging contrast agents. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1993;3(1):187–194. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880030131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roca AG, Morales MP, Serna CJ. Synthesis of monodispersed magnetite particles from different organometallic precursors. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics. 2006;42(10):3025–3029. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tartaj P, del Puerto Morales M, Veintemillas-Verdaguer S, Gonzalez-Carreno T, Serna CJ. The preparation of magnetic nanoparticles for applications in biomedicine. J Phys D: Appl Phys. 2003;36(13):182–197. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rheinlaender T, Koetitz R, Weitschies W, Semmler W. Magnetic fractionation of magnetic fluids. J Magn Magn Mat. 2000;219(2):219–228. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rheinlaender T, Roessner D, Weitschies W, Semmler W. Comparison of size-selective techniques for the fractionation of magnetic fluids. J Magn Magn Mat. 2000;214(3):269–275. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romanus E, Koettig T, Glockl G, Prass S, Schmidl F, Heinrich J, Gopinadhan M, Berkov DV, Helm CA, Weitschies W, Weber P, Seidel P. Energy barrier distributions of maghemite nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2007;18(11):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzales M, Krishnan KM. Synthesis of magnetoliposomes with monodisperse iron oxide nanocrystal cores for hyperthermia. J Magn Magn Mat. 2005;293(1):265–270. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyeon T, Lee SS, Park J, Chung Y, Na HB. Synthesis of highly crystalline and monodisperse maghemite nanocrystallites without a size-selection process. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123(51):12798–12801. doi: 10.1021/ja016812s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bao Y, Pakhomov AB, Krishnan KM. A general approach to synthesis of nanoparticles with controlled morphologies and magnetic properties. J App Phys. 2005;97(10):10. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzales M, Krishnan KM. Phase transfer of highly monodisperse iron oxide nanocrystals with Pluronic F127 for biomedical applications. J Magn Magn Mat. 2007;311:59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kabanov A, Zhu J, Alakhov V. Pluronic Block Copolymers for Gene Delivery. Adv Genet. 2005;53PA:231–261. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(05)53009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goppert TM, Muller RH. Protein adsorption patterns on poloxamer- and poloxamine-stabilized solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2005;60(3):361–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goppert TM, Muller RH. Adsorption kinetics of plasma proteins on solid lipid nanoparticles for drug targeting. Int J Pharm. 2005;302(1-2):172–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muldoon LL, Sandor M, Pinkston KE, Neuwelt EA. Imaging, distribution, and toxicity of superparamagnetic iron oxide magnetic resonance nanoparticles in the rat brain and intracerebral tumor. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(4):785–796. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/57.4.785. discussion 785-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissleder R, Stark DD, Engelstad BL, Bacon BR, Compton CC, White DL, Jacobs P, Lewis J. Superparamagnetic iron oxide: pharmacokinetics and toxicity. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152(1):167–173. doi: 10.2214/ajr.152.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bacon BR, Stark DD, Park CH, Saini S, Groman EV, Hahn PF, Compton CC, Ferrucci JT., Jr Ferrite particles: a new magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent. Lack of acute or chronic hepatotoxicity after intravenous administration. J Lab Clin Med. 1987;110(2):164–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JH, Huh YM, Jun YW, Seo JW, Jang JT, Song HT, Kim S, Cho EJ, Yoon HG, Suh JS, Cheon J. Artificially engineered magnetic nanoparticles for ultra-sensitive molecular imaging. Nature medicine. 2007;13(1):95–99. doi: 10.1038/nm1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soenen SJ, De Cuyper M. Assessing cytotoxicity of (iron oxide-based) nanoparticles: an overview of different methods exemplified with cationic magnetoliposomes. Contrast media & molecular imaging. 2009;4(5):207–219. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monteiro-Riviere NA, Inman AO, Zhang LW. Limitations and relative utility of screening assays to assess engineered nanoparticle toxicity in a human cell line. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2009;234(2):222–235. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diaz B, Sanchez-Espinel C, Arruebo M, Faro J, de Miguel E, Magadan S, Yague C, Fernandez-Pacheco R, Ibarra MR, Santamaria J, Gonzalez-Fernandez A. Assessing methods for blood cell cytotoxic responses to inorganic nanoparticles and nanoparticle aggregates. Small (Weinheim an der Bergstrasse, Germany) 2008;4(11):2025–2034. doi: 10.1002/smll.200800199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teeguarden JG, Hinderliter PM, Orr G, Thrall BD, Pounds JG. Particokinetics in vitro: dosimetry considerations for in vitro nanoparticle toxicity assessments. Toxicol Sci. 2007;95(2):300–312. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stern S. In: Response to questions on NCI Method GTA-2 V. 1. Gonzales M, editor. Frederick, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stern S, Potter T. NCL Method GTA-2 V.1 HEP G2 Hepatocarcinoma Cytotoxicity Assay. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.William WY, Chang E, Sayes CM, Drezek R, Colvin VL. Aqueous dispersion of monodisperse magnetic iron oxide nanocrystals through phase transfer. Nanotechnology. 2006;17(17):4483–4487. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmad S, Ahmad A, Schneider KB, White CW. Cholesterol interferes with the MTT assay in human epithelial-like (A549) and endothelial (HLMVE and HCAE) cells. Int J Toxicol. 2006;25(1):17–23. doi: 10.1080/10915810500488361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carmichael J, DeGraff WG, Gazdar AF, Minna JD, Mitchell JB. Evaluation of a tetrazolium-based semiautomated colorimetric assay: assessment of chemosensitivity testing. Cancer Res. 1987;47(4):936–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Decker T, Lohmann-Matthes ML. A quick and simple method for the quantitation of lactate dehydrogenase release in measurements of cellular cytotoxicity and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) activity. J Immunol Methods. 1988;115(1):61–69. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(88)90310-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denizot F, Lang R. Rapid colorimetric assay for cell growth and survival. Modifications to the tetrazolium dye procedure giving improved sensitivity and reliability. J Immunol Methods. 1986;89(2):271–277. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Legrand C, Bour JM, Jacob C, Capiaumont J, Martial A, Marc A, Wudtke M, Kretzmer G, Demangel C, Duval D, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity of the cultured eukaryotic cells as marker of the number of dead cells in the medium [corrected] J Biotechnol. 1992;25(3):231–243. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(92)90158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65(1-2):55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]