DGKι regulates presynaptic release during mGluR-dependent LTD

Diacylglycerol (DAG) is a second messenger acting in synaptic signalling. The DAG metabolizing enzyme DGKι regulates presynaptic neurotransmitter release and PSD-95 family proteins promote its synaptic localization.

Keywords: diacylglycerol kinase, long-term depression, metabotropic glutamate receptors, phospholipase C, PSD-95

Abstract

Diacylglycerol (DAG) is an important lipid second messenger. DAG signalling is terminated by conversion of DAG to phosphatidic acid (PA) by diacylglycerol kinases (DGKs). The neuronal synapse is a major site of DAG production and action; however, how DGKs are targeted to subcellular sites of DAG generation is largely unknown. We report here that postsynaptic density (PSD)-95 family proteins interact with and promote synaptic localization of DGKι. In addition, we establish that DGKι acts presynaptically, a function that contrasts with the known postsynaptic function of DGKζ, a close relative of DGKι. Deficiency of DGKι in mice does not affect dendritic spines, but leads to a small increase in presynaptic release probability. In addition, DGKι−/− synapses show a reduction in metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long-term depression (mGluR-LTD) at neonatal (∼2 weeks) stages that involve suppression of a decrease in presynaptic release probability. Inhibition of protein kinase C normalizes presynaptic release probability and mGluR-LTD at DGKι−/− synapses. These results suggest that DGKι requires PSD-95 family proteins for synaptic localization and regulates presynaptic DAG signalling and neurotransmitter release during mGluR-LTD.

Introduction

The phospholipase C (PLC) family of enzymes hydrolyses phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol trisphosphate, both of which function as important lipid signalling molecules (Rhee, 2001). PLCs are stimulated in response to activation of various surface receptors, including G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and non-GPCR receptors (Sternweis et al, 1992; Rhee, 2001). Among the receptors at excitatory synapses that stimulate PLC are metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) and ionotropic NMDA receptors (Reyes-Harde and Stanton, 1998; Choi et al, 2005b; Horne and Dell'Acqua, 2007). DAG activates a series of downstream effectors that contain the DAG-binding C1 domain, such as protein kinase C (PKC), UNC-13, RasGRPs, and chimaerins (Brose et al, 2004). The functions of DAG at the synapse, however, are only beginning to be understood (Brose et al, 2004; Goto et al, 2006; Kim et al, 2009a).

Agonist-induced DAG signalling is terminated by enzymatic conversion of DAG to phosphatidic acid (PA) by diacylglycerol kinases (DGKs). There are 10 known mammalian DGKs belonging to one of five types (type I–V), which are mostly expressed in the brain (Luo et al, 2004; Sakane et al, 2007; Topham and Epand, 2009). DGKζ and DGKι are two closely related type IV DGKs. DGKζ has recently been shown to interact with postsynaptic density (PSD)-95, an abundant postsynaptic scaffolding protein (Sheng and Hoogenraad, 2007; Keith and El-Husseini, 2008), and regulate the maintenance of dendritic spines and excitatory synapses by regulating postsynaptic DAG signalling (Frere and Di Paolo, 2009; Kim et al, 2009a, 2009b).

DGKι shares an identical domain structure with DGKζ, including the C-terminal PDZ domain-binding motif (Bunting et al, 1996; Ding et al, 1998a, 1998b). This suggests that DGKι might also bind PSD-95 and regulate synaptic structure and function. In addition, DGKι negatively regulates RasGRP3/CalDAG-GEFIII (Regier et al, 2005), a brain-expressed DAG effector with guanine nucleotide exchange factor activity for Ras and Rap small GTPases (Yamashita et al, 2000), which are known to regulate synaptic/spine structure and synaptic plasticity (Pak et al, 2001; Zhu et al, 2002; Pak and Sheng, 2003).

Here, we report that DGKι interacts with PSD-95 family proteins, and that this interaction promotes synaptic localization of DGKι. Deficiency of DGKι in mice has no effect on dendritic spines. Rather, DGKι−/− mice show a small increase in presynaptic release probability. In addition, mGluR-dependent long-term depression (mGluR-LTD) is reduced in neonatal (2 weeks) DGKι−/− mice through presynaptic mechanisms, and is normalized by the inhibition of PKC. These results indicate that DGKι regulates presynaptic DAG signalling and neurotransmitter release during mGluR-LTD, which sharply contrasts with the prominent postsynaptic functions of the close relative DGKζ.

Results

PSD-95 family proteins interact with and promote synaptic localization of DGKι

We have recently reported that DGKζ, a close relative of DGKι, interacts directly with the PDZ domain of PSD-95 (Kim et al, 2009b). We thus first tested whether DGKι also interacts with PSD-95. We found that DGKι forms a complex with PSD-95 and three other PSD-95 family proteins (PSD-93/chapsyn-110, SAP97, and SAP102) in HEK293 cells (Figure 1A–D). In contrast, a DGKι mutant that lacks the C-terminal PDZ-binding motif (DGKι Δ3) showed no, or substantially weakened, interactions with PSD-95 family proteins. DGKι also formed a complex with PSD-95 and three other PSD-95 family proteins in rat brain lysates (Figure 1E–I).

Figure 1.

PSD-95 family proteins interact with and promote synaptic localization of DGKι. (A–D) In vitro coimmunoprecipitation. HEK293T cell lysates doubly transfected with HA-tagged DGKι (WT or the Δ3 mutant that lacks the C-terminal PDZ-binding motif) and PSD-95 family proteins (PSD-95 and EGFP-tagged PSD-95 relatives) were immunoprecipitated with HA-agarose, and immunoblotted with HA, PSD-95, or EGFP antibodies. IP, immunoprecipitation. (E–I) In vivo coimmunoprecipitation. Detergent lysates of the crude synaptosomal fraction of adult rat brain (6 weeks) were immunoprecipitated with DGKι or PSD-95 family antibodies and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (J, K) PSD-95 promotes the spine localization of DGKι. Cultured hippocampal neurons were transfected doubly with HA-DGKι (WT or Δ3) +EGFP, or triply with HA-DGKι (WT or Δ3) +PSD-95+EGFP (DIV 17–18), and monitored of spine localization of DGKι by immunostaining for DGKι and PSD-95. All the experiments in Figure 1 were repeated three times. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test. Scale bar, 10 μm.

DGKι exogenously expressed alone in cultured hippocampal neurons showed a diffuse distribution pattern throughout the neuron regardless of its possession of the PSD-95-binding C-terminus, likely due to its overexpression (Figure 1J and K). However, when DGKι was coexpressed with PSD-95, the spine localization of DGKι, determined by the spine/dendrite ratio of the protein, was significantly increased. In contrast, the mutant DGKι Δ3 coexpressed with PSD-95 showed a diffuse distribution similar to that of singly expressed DGKι. These results suggest that PSD-95 promotes synaptic localization of DGKι.

Expression patterns of DGKι protein in the rat brain

We next examined the expression patterns of DGKι protein in the rat brain using an anti-DGKι polyclonal antibody generated for this study. This antibody recognized a major ∼115 kDa band in the brain, a size similar to that of HA-DGKι expressed in HEK293T cells (Supplementary Figure S1A), and did not cross-react with DGKζ (Supplementary Figure S1B), indicating that it is specific to DGKι. In addition, this antibody did not detect the DGKι protein in brain lysates from DGKι−/− mice (Supplementary Figure S1C), further confirming its specificity.

In a series of immunoblot analyses, DGKι protein expression was found mainly in the brain, and not in other tissues (Figure 2A). DGKι protein was detected in diverse subregions of the brain (Figure 2B). During postnatal rat brain development, DGKι expression gradually increased, similar to the expression pattern of PSD-95 (Figure 2C). In subcellular fractions of rat brains, DGKι was detected in synaptic fractions, including the crude synaptosomal (P2) and synaptic membrane (LP1) fractions (Figure 2D). DGKι proteins in the P2 fraction were similarly partitioned to LP1 and LP2 (synaptic vesicle-enriched) fractions (44.5±4.1 and 55.5±4.1%, respectively; n=3 mice). The detection of DGKι in the LP2 fraction suggests that DGKι is present at presynaptic vesicles. DGKι was also detected in other fractions, including the cytosolic (S3) and microsomal (P3) fractions, suggesting that DGKι protein is widespread at various subcellular sites. DGKι was highly enriched in PSD fractions; similar to PSD-95, it was detected in the highly detergent-resistant PSD III fraction (Figure 2E), suggesting that DGKι is tightly associated with the PSD.

Figure 2.

Expression patterns of DGKι protein in the rat brain. (A) DGKι proteins are mainly expressed in the brain, as revealed by immunoblot analysis with DGKι antibodies (1870). Sk., skeletal. (B) Widespread distribution of DGKι proteins in various rat brain regions, revealed by immunoblotting of whole brain homogenates. (C) Expression levels of DGKι gradually increase during postnatal rat brain development, similar to PSD-95. P, postnatal day; W, week. (D) Widespread distribution of DGKι protein in various rat brain subcellular fractions, revealed by immunoblot analysis (1871 DGKι antibodies). H, homogenates; P2, crude synaptosomes; S2, supernatant after P2 precipitation; S3, cytosol; P3, light membranes; LP1, synaptosomal membranes; LS2, synaptosomal cytosol; LP2, synaptic vesicle-enriched fraction. (E) Enrichment of DGKι in PSD fractions; extracted with Triton X-100 once (PSD I), twice (PSD II), or with Triton X-100 and Sarkosyl (PSD III). These immunoblot experiments shown in panels A–E were repeated three times. (F, G) DGKι is detected in both MAP2-positive dendrites and NF200-positive axons. Cultured hippocampal neurons (DIV 21) were stained with DGKι antibodies (1869). Scale bar, 30 μm. (H–L) DGKι is mainly present at excitatory synapses. Cultured neurons (DIV 21) were doubly stained for DGKι (red; 1871) and synaptophysin (H, green), PSD-95 (I), Shank (J), GAD65 (K), or gephyrin (L). These experiments were repeated twice. Scale bar, 10 μm.

In cultured hippocampal neurons, DGKι immunofluorescence signals were detected in discrete, but often diffuse, structures along neuronal processes that were positive for both MAP2 (dendritic marker) and NF200 (axonal marker) (Figure 2F and G). DGKι signals were mainly detected at excitatory synaptic sites; DGKι colocalized with the presynaptic protein synapsin I and excitatory postsynaptic proteins PSD-95 and Shank, but not with the inhibitory presynaptic protein GAD65 or the inhibitory postsynaptic protein gephyrin (Figure 2H–L). These results indicate that DGKι protein is present in both dendrites and axons, and at excitatory, but not inhibitory, synapses.

In mouse brain slices, DGKι immunofluorescence signals were detected in various brain regions including the hippocampus and cerebellum. In the hippocampus, DGKι signals were detected in all subfields (Supplementary Figure S2A–E). In the cerebellum, DGKι signals were detected in various layers including the Purkinje cell layer (Supplementary Figure S2F). The authenticity of these signals was supported by the absence of DGKι signals in DGKι−/− slices (Supplementary Figure S2C).

Ultrastructural localization of DGKι protein

We also determined the ultrastructural localization of DGKι protein in rat brain regions by electron microscopy (Figure 3). In the hippocampal CA1 region, DGKι signals were detected in cell bodies, dendrites, dendritic spines, and axon terminals (Figure 3A–D). In axon terminals, DGKι signals colocalized with presynaptic vesicles as well as the presynaptic plasma membrane. In the cerebellar Purkinje and molecular layers, DGKι signals were detected in cell bodies, dendritic spines, and axon terminals (Figure 3E–G). In the cerebellar granule cell layer, DGKι signals were detected in cell bodies, dendritic shafts, and axon terminals (Figure 3H and I). These results indicate that the DGKι protein is present in various subcellular regions of neurons in the hippocampus and cerebellum, and at both pre- and postsynaptic sites.

Figure 3.

Ultrastructural localization of DGKι proteins in somatodendritic and synaptic regions of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons (A–D), cerebellar Purkinje cell and molecular layers (E–G), and the cerebellar granular layer (H, I). D2, G2, and I2 represent enlarged images of the insets in D1, G1, and I1, respectively. DGKι signals, shown as dark DAB precipitates (black arrowheads), are present in the cell body (A), dendritic shafts (D; B), dendritic spines (S; C), and axon terminals (AT; D) of CA1 pyramidal neurons. In the cerebellum, DGKι signals were observed in Purkinje (E) and granule (H) cell bodies. In the cerebellar molecular layer, DGKι localizes to dendritic spines (S; F) and axon terminals (AT; G). In the granule cell layer (I), DGKι localizes to dendritic shafts (D) and axon terminals (AT). White arrowheads in D, G, and I indicate DAB precipitates associated with the synaptic plasma membrane. Scale bars, 2 μm in A, E, and H, and 0.5 μm in B, C, D1, F, G1, and I1, and 0.1 μm in D2, G2, and I2.

Quantitative analysis indicated that DGKι signals are present in 13.3±2.5% of axon terminals and 44.2±4.0% of dendritic spines in the hippocampal CA1 region (n=3 animals for wild type (WT) and knockout (KO); total area analysed, 232.2 μm2/animal). In the cerebellar Purkinje and molecular layers, DGKι signals were found in 45.0±3.2% of axon terminals and 13.5±2.2% of spines. In the cerebellar granule cell layer, DGKι signals were found in 44.8±4.9% of axon terminals and 18.8±4.1% of spines. Therefore, subsets of pre- and postsynaptic structures appear to contain DGKι signals, although the measured values may vary depending on the affinity of the antibodies. In addition, the relative distribution of DGKι signals at pre- and postsynaptic sites appears to vary according to the region of the brain observed.

Normal levels of synaptic proteins and spine density and morphology in the DGKι−/− brain

The ultrastructural localization of DGKι at synaptic sites led us to test whether DGKι regulates synaptic structure or function, using the previously described DGKι−/− mice (Regier et al, 2005). We first compared expression levels of known pre- and postsynaptic proteins in WT and KO mice, but were unable to detect any significant changes in the expression levels of these proteins (Figure 4A). Expression levels of other DGK isoforms (DGKζ, DGKγ, and DGKθ) were unchanged in DGKι−/− mice (Figure 4B). Notably, however, DGKι−/− mice showed a significant increase in the expression levels of SNAP-25 (Figure 4A), a t-SNARE protein known to regulate presynaptic release (Washbourne et al, 2002; Sorensen et al, 2003; Sudhof, 2004).

Figure 4.

Normal expression levels of known synaptic proteins and other DGK isoforms except for SNAP-25 in DGKι−/− mice. Normal expression levels of other synaptic proteins (A) and other DGK isoforms (B) in DGKι−/− mice relative to WT mice (7–9 weeks). n=4–5 for A2, and 3 for A3 and B panels. *P<0.05, Student's t-test.

As spine density is significantly reduced in DGKζ−/− mice (Kim et al, 2009b), we investigated spine phenotypes in DGKι−/− mice. Dendritic spines were visualized by biolistic delivery of the lipophilic dye DiI to apical dendrites (stratum radiatum) of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons (Gan et al, 2000). Surprisingly, there was no significant difference between the spine density in DGKι−/− brains (6.40±0.40 spines/10 μm) and WT brains (7.50±0.50; Figure 5A and B). In addition, DGKι KO caused no change in the length (WT, 1.26±0.03 μm; KO, 1.32±0.05), width (WT, 0.75±0.01; KO, 0.75±0.01), or head area (WT, 0.38±0.01 μm2; KO, 0.38±0.01) of dendritic spines (Figure 5C–E). These results indicate that DGKι deficiency has no effect on the density or morphology of dendritic spines. This contrasts sharply with the marked reduction in spine density observed in DGKζ−/− mice (Kim et al, 2009b), a difference that is particularly striking given the identical domain structure of the two proteins.

Figure 5.

Enhanced synaptic transmission and a small increase in presynaptic release probability, but no changes in spine density or morphology, in the DGKι−/− brain. (A) Representative images of DiI-labelled dendritic segments (stratum radiatum) of CA1 pyramidal neurons from WT and KO mice. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B–E) Quantification of spine density (B), length (C), width (D), and head area (E). Mean±s.e.m. (WT, n=24 cells from four mice; KO, n=35, 4; 3 weeks). (F–H) Normal frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs in DGKι−/− CA1 pyramidal neurons. WT, n=13, 4; KO, n=18, 4; P16–21). (I, J) Unchanged AMPA/NMDA ratio at DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses (WT, n=6 cells, three mice; KO, n=9, 4; P16–21). (K) Enhanced evoked excitatory transmission at DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses. The synaptic input–output relationship was obtained by plotting the slopes of evoked fEPSPs against fibre-volley amplitudes. The inset compares the average input–output ratios of WT and KO synapses. WT, n=33, 13; KO, 32, 13; **P<0.01, Student's t-test. 3–5 weeks. (L) A small decrease in paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) at DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses. The ratios of paired-pulse responses (second fEPSP slope/first fEPSP slope) were plotted against inter-stimulus intervals (in ms). Note that a significant difference is observed at 20 ms inter-stimulus interval. WT, n=18, 10; KO, n=19, 11; 3–5 weeks; *P<0.05, Student's t-test.

Enhanced evoked excitatory transmission and a small increase in neurotransmitter release probability at DGKι−/− Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses

The absence of an effect of DGKι KO on dendritic spines does not exclude the possibility that DGKι regulates synaptic functions, considering the well-known involvement of DGKι-interacting PSD-95 family proteins in regulating synaptic functions (Fitzjohn et al, 2006; Sheng and Hoogenraad, 2007). We thus investigated whether excitatory transmission was changed in the DGKι−/− brain by measuring miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) from DGKι−/− CA1 pyramidal neurons. However, both the frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs in DGKι−/− neurons (frequency, 0.13±0.02 Hz; amplitude, 26.5±1.6 pA) were similar to those in WT neurons (frequency, 0.10±0.02 Hz; amplitude, 28.2±2.9; Figure 5F–H). In addition, the ratio of AMPA receptor- and NMDA receptor-mediated evoked EPSCs (AMPA/NMDA ratio) at Schaffer collateral (SC)-CA1 pyramidal (CA1) synapses in DGKι−/− mice (1.65±0.32) was similar to that in WT mice (1.34±0.20; Figure 5I and J).

We next used extracellular recordings to investigate whether DGKι deficiency caused any change in evoked synaptic transmission. Intriguingly, the relationship between fibre-volley amplitude and postsynaptic response (input–output curve) was significantly increased at DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses (Figure 5K). There were no changes in the relationship between fibre-volley amplitudes and stimulus intensities (Supplementary Figure S3). These results suggest that AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission was increased at DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses, which is not caused by increased excitability of presynaptic fibres.

Paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) at DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses was largely normal compared with that at WT synapses, except for a small decrease observed at a 20-ms inter-stimulus interval (1.48±0.03 in WT versus 1.59±0.03 in KO; P<0.05; Figure 5L). As these measurements were made using slices from 3- to 5-week-old mice, we made additional PPF measurements using slices from 2- to 6-week-old mice. Although SC-CA1 synapses from 2-week-old, but not 6-week-old, DGKι−/− slices exhibited a relatively clear tendency for a decrease in PPF, these differences did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Figure S4A and B). As 2- and 3–5-week-old slices showed clearer tendencies towards a decrease in PPF than those from 6-week-old slices, we combined data from these samples (2–5 weeks) and were able to observe an even larger and more significant decrease in PPF (P<0.01; Supplementary Figure S4C). These results suggest that DGKι deficiency has a small effect on presynaptic release, with changes occurring at earlier developmental stages (2–5 weeks) and at particular inter-stimulus intervals. This increase in presynaptic release, although small, may partly contribute to the increase in synaptic transmission indicated in the input–output curve (Figure 5K).

Enhanced MK-801-induced decay in NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs at DGKι−/− hippocampal autapses

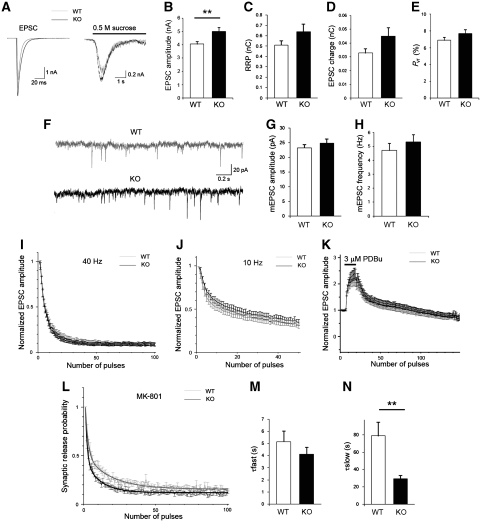

To examine the function of DGKι in the presynaptic terminal-release machinery, we assessed glutamatergic synaptic transmission in individual hippocampal neurons from WT and DGKι−/− mice in autaptic culture (Jockusch et al, 2007), measuring EPSC amplitude, readily releasable pool (RRP) size, and vesicular release probability (Pvr). We found that the amplitude of EPSC was significantly increased at DGKι−/− autapses, compared with WT synapses (WT, 4.06±0.21 nA, n=214 cells; KO, 5.01±0.30, n=212, P<0.01, Student's t-test; Figure 6A and B). In contrast, RRP and Pvr were normal at DGKι−/− autapses; the size of the RRP, defined as vesicles whose release can be triggered by the application of a hypertonic buffer containing 0.5 M sucrose (Jockusch et al, 2007), was 0.61±0.05 nC (n=127 cells) in DGKι−/− neurons and 0.51±0.04 nC (n=119) in WT neurons (Figure 6A and C); and Pvr calculated by dividing the charge transfer during a single EPSC by RRP size was 7.70±0.45% (n=127) in DGKι−/− neurons and 6.90±0.33% (n=119) in WT neurons (Figure 6D and E).

Figure 6.

Enhanced MK-801-induced decay in NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs at DGKι−/− hippocampal autapses. (A) Representative evoked EPSC traces (left), and release triggered by 0.5 M sucrose solution (right; 6 s) from WT (grey) and DGKι−/− (black) neurons. (B) Mean EPSC amplitudes measured in WT and DGKι−/− neurons. Error bars indicate s.e.m. values. **P<0.01, Student's t-test. (C) Mean RRP sizes estimated as the charge integral measured after release induced by application of 0.5 M sucrose solution. (D) Mean EPSC charge integral over time measured in WT and DGKι−/− neurons. (E) Average Pvr for WT and DGKι−/− neurons. (F) Representative mEPSC traces in WT and DGKι−/− neurons. (G, H) Average mEPSC amplitude (G) and frequency (H) in WT and DGKι−/− neurons. (I, J) Normalized synaptic responses induced by 40 Hz (I) and 10 Hz (J) stimuli in WT and DGKι neurons. (K) Similar effects of PDBu (3 μM) on EPSCs in WT and DGKι−/− neurons. EPSCs were evoked at 0.2 Hz and normalized to the initial amplitude. (L–N) Synaptic NMDA EPSCs were blocked by eliciting a series of 100 EPSCs at 0.3 Hz in the presence of MK-801 (5 μM). The successively decreasing normalized average amplitudes of NMDA-mediated EPSCs were plotted against stimulus numbers. The decay of the NMDA ESPC amplitudes in WT (grey) and DGKι−/− (black) cells was fitted with two exponentials to obtain the average time constants for fast (M) and slow (N) decay components. **P<0.01, Student's t-test.

To determine whether quantal size was altered in DGKι−/− synapses, we recorded and analysed mEPSCs. We found that mEPSC amplitude and frequency in DGKι−/− neurons (amplitude, 25.1±1.03 pA, n=90; frequency, 5.33±0.54 Hz, n=90) were similar to those in WT neurons (amplitude, 24.31±1.05 pA, n=84; frequency, 4.72±0.52 Hz, n=84; Figure 6F–H). The amplitude and frequency of spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs) measured in the absence of TTX, which include both TTX-sensitive and TTX-resistant sEPSCs, were similar between WT and DGKι−/− neurons (amplitude: WT, 20.7±0.9 pA, n=43; KO, 21.7±1.0, n=45; frequency: WT, 3.0±0.4 Hz, n=43; KO, 3.7±0.5, n=45; number of events analysed: WT, 895±128, n=43; KO, 1108±161, n=45). There were no changes in short-term plasticity observed during the train of action potentials (Figure 6I and J).

As DGK is likely essential for regulation of synaptic strength by the Munc13-related pathway, we examined the function of Munc13 in the synaptic release machinery by measuring potentiation of glutamate release by phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (PDBu) in WT and DGKι−/− neurons. The potentiation ratios were identical for WT and DGKι−/− neurons (Figure 6K). In addition, treatment of neurons with the PKC inhibitors bisindoylmaleimide I and Ro-31-8220 (Gordge and Ryves, 1994; Rhee et al, 2002; Wierda et al, 2007) and the DAG-binding C1-domain blocker calphostin C (Kobayashi et al, 1989; Brose and Rosenmund, 2002) did not produce a difference between WT and DGKι−/− neurons in PDBu-dependent potentiation of presynaptic release (Supplementary Figure S5). These results suggest that Munc13 function is normal in DGKι−/− neurons.

We next examined whether the increase in EPSC amplitude in DGKι−/− neurons was attributable to a change in synaptic release probability. To address this question, we monitored the NMDA component of EPSCs by measuring the progressive block of NMDA-mediated EPSCs by the irreversible NMDA receptor open-channel blocker MK-801 in neurons stimulated at 0.3 Hz in the presence of 10 μM glycine and 2.7 mM Ca2+ (no Mg2+). During 100 stimuli at 0.3 Hz, the decay kinetics of MK-801 block exhibited both a rapid and a slow component. Surprisingly, the time constant for NMDA-mediated decay of EPSCs was much shorter in DGKι−/− neurons than in WT neurons. This difference was attributable to an acceleration of the slow component in KO neurons (τs=29.2±4.02 s, n=12) compared with WT neurons (τs=78.8±15.7 s, n=12; P<0.01, Student's t-test); in contrast, the fast component was not significantly altered by DGKι KO (τf=4.12±0.56 s in KO versus τf=5.16±0.87 s in WT; Figure 6L–N). Thus, despite the fact that the proportions of each component (fast and slow) were identical between the two different neurons (WT, τf=80.0±5.31%, τs=19.2±5.23%, n=6; KO, τf=79.5±3.85%, τs=20.5±3.86%, n=6), the synaptic release probability was higher in DGKι−/− neurons than in WT neurons.

Reduced mGluR-dependent LTD at neonatal, but not adult, DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses

We next tested whether DGKι deficiency caused any changes in synaptic plasticity. DGKι−/− mice showed normal long-term potentiation (LTP) induced by theta burst stimulation (TBS) at SC-CA1 synapses (Figure 7A). In addition, LTD induced by single-pulse, low-frequency stimulation (SP-LFS) was normal in these mice (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Reduced presynaptic mGluR-dependent LTD at neonatal (2 weeks) DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses. (A) Normal LTP induced by TBS at DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses. WT, 133.3±3.8%; KO, 132.8±6.6% (WT, n=15 slices from eight mice; KO, 14, 7; 4–5 weeks). (B) Normal LTD induced by SP-LFS (1 Hz, 900 stimuli) at DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses (3 weeks). WT, 78.6±2.6%, n=10, 5; KO, 73.9±2.8%, n=12, 4. (C) Reduced DHPG (100 μM; RS form)-induced LTD at neonatal (P14–15) DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses. WT, 68.6±3.4%, n=7, 4; KO, 86.0±4.1%, n=10, 4; **P<0.01, Student's t-test. (D) Normal DHPG-LTD at adolescent (4–5 weeks) DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses. WT, 89.9±3.0%, n=10, 4; KO, 88.7±2.3%, n=13, 4. (E) Normal PP-LFS-induced LTD at DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses (8 weeks). PP-LFS, 900 pairs of 1 Hz stimuli with 50 ms inter-stimulus intervals. WT, 83.3±4.1%, n=12, 7; KO, 84.0±3.3%, n=14, 7.

SP-LFS-induced LTD is known to involve both NMDA receptors and mGluRs (Oliet et al, 1997; Nicoll et al, 1998). To isolate mGluR-dependent LTD, we used two different methods to activate mGluRs: direct stimulation with (RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG), a group I mGluR agonist (Palmer et al, 1997; Fitzjohn et al, 1999), and paired-pulse, low-frequency stimulation (PP-LFS) (Kemp et al, 2000). LTD is induced differentially at pre- or postsynaptic loci by mGluR activation depending on the developmental stage of the brain; in neonatal stages, presynaptic mGluR-LTD is predominant, whereas postsynaptic mGluR-LTD dominates in adolescent stages (Bolshakov and Siegelbaum, 1994; Oliet et al, 1997; Fitzjohn et al, 2001; Zakharenko et al, 2002; Feinmark et al, 2003; Rammes et al, 2003; Nosyreva and Huber, 2005), although mGluR-LTD at adult slices also involve presynaptic mechanisms (Fitzjohn et al, 2001; Watabe et al, 2002; Rammes et al, 2003; Rouach and Nicoll, 2003; Tan et al, 2003; Moult et al, 2006). In experiments performed using hippocampal slices from neonatal (12–14 days) mice, we found that LTD induced at SC-CA1 synapses by DHPG treatment was significantly reduced by ∼55% in DGKι−/− slices (86.0±4.1%) compared with WT synapses (68.6±3.4%; P<0.01; Figure 7C). In contrast, LTD induced by treatment of adolescent (4–5 weeks) DGKι−/− slices with DHPG was normal (Figure 7D). Consistent with this, when PP-LFS, which mainly triggers postsynaptic mGluR-LTD (Kemp et al, 2000), was administered to 8-week-old DGKι−/− slices, it induced LTD that was indistinguishable from that in WT mice (Figure 7E). These results suggest that DGKι deficiency selectively attenuates presynaptic mGluR-dependent LTD at neonatal (2 weeks) SC-CA1 synapses.

Reduced DHPG-LTD at neonatal DGKι−/− synapses involves suppression of an increase in PPF

To determine whether the reduction in mGluR-dependent LTD in the neonatal DGKι−/− hippocampus involves presynaptic mechanisms, we measured PPF 10 min before and 60 min after the induction of DHPG-induced mGluR-LTD (DHPG-LTD) at SC-CA1 synapses from 2-week-old mice (Figure 8A). Before DHPG treatment, both WT and DGKι−/− slices showed comparable PPF patterns (Supplementary Figure S4A). After the induction of DHPG-LTD, PPF in WT slices was significantly increased at five inter-stimulus intervals (20, 40, 80, 160, and 320 ms) (Figure 8B), consistent with the previous reports (Fitzjohn et al, 2001; Watabe et al, 2002; Rouach and Nicoll, 2003; Tan et al, 2003). DGKι−/− slices showed increases in PPF at two inter-stimulus intervals (320 and 640 ms; Figure 8C). Given that the degree of PPF tends to decline as an exponential function of time at intervals < 200 ms, but not at longer intervals (Creager et al, 1980), these results suggest that there is a smaller increase in PPF at DGKι−/− synapses relative to WT synapses. This difference was paralleled by a significant reduction in DHPG-LTD at DGKι−/− synapses relative to WT synapses (Figure 8D).

Figure 8.

Reduced DHPG-LTD at neonatal (2 weeks) DGKι−/− synapses involves suppression of an increase in PPF. (A) A diagram depicting PPF measurement 10 min before and 60 min after the induction of mGluR-LTD by DHPG (100 μM) treatment. (B, C) PPF patterns measured at neonatal WT (B) and DGKι−/− (C) SC-CA1 synapses before and after DHPG-LTD. Note that the increase in PPF during DHPG-LTD is suppressed at DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses. Data from panels B, C, E, and F (before DHPG) were used to generate Supplementary Figure S4A and B. WT, n=11 slices from four mice; KO, n=12, 4; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; Student's t-test. (D) Reduced DHPG-LTD at neonatal DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses. WT, 63.8±4.7%, n=11, 4; KO, 77.9±3.5%, n=12, 4; ***P<0.001, Student's t-test. (E, F) PPF patterns measured before and after DHPG-LTD at adult (6 weeks) WT (E) and DGKι−/− (F) SC-CA1 synapses. Note that the increase in PPF during DHPG-LTD is suppressed at DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses. WT, n=9, 4; KO, n=9, 4; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; Student's t-test. (G) Comparable DHPG-LTD at adult WT and DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses. WT, 83.5±4.4%, n=9, 4; KO, 89.4±3.7%, n=9, 4; P=0.35, Student's t-test.

PPF at adult (6 weeks) WT SC-CA1 synapses was also significantly increased by DHPG treatment (Figure 8E), whereas PPF at DGKι−/− synapses was similar to that in untreated synapses (Figure 8F). These results suggest that DHPG-LTD at adult synapses also involves presynaptic mechanisms, although to a lesser extent than at neonatal synapses, consistent with previous reports (Fitzjohn et al, 2001; Watabe et al, 2002; Rammes et al, 2003; Rouach and Nicoll, 2003; Tan et al, 2003; Moult et al, 2006). However, DHPG-LTD at DGKι−/− synapses was comparable with that at WT synapses (Figure 8G), likely due to the relatively small increase in PPF at WT synapses. These results suggest that the reduced DHPG-LTD at neonatal (2 weeks) DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses involves suppression of the increase in PPF associated with mGluR-LTD.

Inhibitors of the C1 domain and PKC normalize PPF and DHPG-LTD at neonatal DGKι−/− synapses

The reduction in mGluR-LTD at DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses may reflect an increase in local DAG concentration and enhanced action on presynaptic DAG effectors. One way to address this question would be to directly test whether the levels of PA, a product of DGK action on DAG, are reduced under basal or DHPG-treated conditions, as previously described (Kim et al, 2009b). However, basal PA levels were not different between WT and DGKι−/− hippocampal slices (Supplementary Figure S6A and B). In addition, DHPG treatment did not lead to a differential fold increase in PA levels relative to basal levels in WT and DGKι−/− slices, although PA levels trended lower in DGKι−/− slices (Supplementary Figure S6A and C). Basal and DHPG-induced levels of PIP2, which is important for regulation of endocytosis (Di Paolo and De Camilli, 2006), were not different between WT and DGKι−/− slices (Supplementary Figure S6D–F). These results might be an indication that DGKι is a less important mediator of presynaptic DAG-to-PA conversion, or that DGKι deficiency can easily be compensated by other DGKs. Alternatively, DGKι may have a major function in presynaptic DAG-to-PA conversion, but the amount of this conversion is relatively small compared with that occurring at postsynaptic sites.

To address this issue further, we used chemical inhibitors of DAG action, namely calphostin C (C1-domain inhibitor) and Ro-31-8220 (a PKC inhibitor), administered during the entire recording periods. When PPF was measured in the presence of calphostin C before DHPG treatment in neonatal (2 weeks) slices, PPF patterns at WT and DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses were comparable (Figure 9A and B), indicating that calphostin C treatment itself has little effect on PPF under basal conditions. After DHPG treatment, WT slices showed a normal enhancement in PPF (Figure 9C), similar to the PPF increase in the absence of calphostin C (Figure 8B). Interestingly, DHPG-induced PPF was significantly increased at calphostin C-treated DGKι−/− synapses (Figure 9D), similar to WT synapses (Figure 9C). Consistent with this, the magnitudes of DHPG-LTD at WT and DGKι−/− synapses were comparable with each other (Figure 9E). This suggests that C1-domain-containing effectors of DAG may be responsible for the reduced DHPG-LTD at DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses.

Figure 9.

Inhibitors of the C1 domain and PKC normalize PPF and DHPG-LTD at neonatal (2 weeks) DGKι−/− synapses. (A) A diagram depicting PPF measurement 10 min before and 60 min after the induction of mGluR-LTD by DHPG (100 μM) treatment; the C1-domain inhibitor calphostin C (1 μM) was present during the entire recording period. (B) Calphostin C has no effect on PPF before DHPG treatment at neonatal WT and DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses. The ‘before-DHPG' data from panels C and D were used to generate this figure. (C, D) Calphostin C normalizes the DHPG-induced increase in PPF at neonatal DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses (D), to an extent that mimics the pattern of PPF change at WT synapses (C). WT, n=11 cells from three mice; KO, n=9, 3; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; Student's t-test. (E) Normal DHPG-LTD at neonatal DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses in the presence of calphostin C. WT, 78.3±3.6%; KO, 74.8±6.0% (WT, n=11, 3; KO, n=9, 3). (F) A diagram depicting PPF measurement 10 min before and 60 min after the induction of mGluR-LTD by DHPG (100 μM) treatment; the PKC inhibitor Ro-31-8220 (1 μM) was present during the entire recording period. (G) Ro-31-8220 has no effect on PPF before DHPG treatment at neonatal WT and DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses. The ‘before-DHPG' data in panels H and I were used to generate this figure. (H, I) Ro-31-8220 normalizes the DHPG-induced increase in PPF at neonatal DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses (I), to an extent that mimics the pattern of PPF change at WT synapses (H). (J) Normal DHPG-LTD at neonatal DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses in the presence of Ro-31-8220. WT, 64.8±1.8%, n=9, 3; KO, 62.4±2.0%, n=10, 3.

We then repeated the same experiments in the presence of Ro-31-8220. After Ro-31-8220 treatment and before DHPG treatment, PPF at WT and DGKι−/− synapses were indistinguishable (Figure 9F and G). After DHPG treatment, PPF was similarly, and significantly, increased at Ro-31-8220-treated DGKι−/− and WT synapses (Figure 9H and I). This increase was paralleled by comparable magnitudes of DHPG-LTD at WT and DGKι−/− synapses (Figure 9J). These results collectively suggest that PKC has an important function in reducing DHPG-LTD at neonatal (2 weeks) DGKι−/− SC-CA1 synapses.

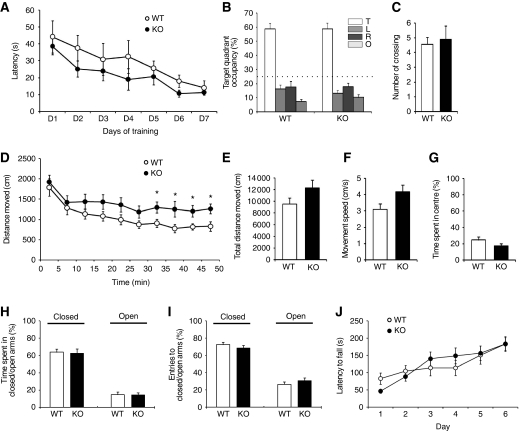

Slow habituation, but normal spatial learning and memory, anxiety-like behaviour, and motor coordination, in DGKι−/− mice

We next used the Morris water-maze assay to test whether DGKι deficiency caused any changes in spatial learning and memory behaviour in mice. During the acquisition phase, WT and DGKι−/− mice showed similar escape latencies to find the hidden platform (Figure 10A). In the probe test performed 24 h after the training phase, WT and DGKι−/− mice spent similar amounts of time in the target quadrant where the platform was formerly located (Figure 10B). In addition, similar numbers of exact crossings over the region where the platform had been located were observed in WT and DGKι−/− mice (Figure 10C). These results indicate that DGKι deficiency in mice does not affect spatial learning and memory.

Figure 10.

Slow habituation, but normal spatial learning and memory, anxiety-like behaviour, and motor coordination, in DGKι−/− mice. (A) Normal spatial learning of DGKι−/− mice in the training phase of the Morris water-maze assay (n=9 for WT and KO; 4–7 months). The latency to find a hidden platform was plotted against the days of training. (B, C) Normal spatial memory of DGKι−/− mice in the probe phase of the Morris water-maze assay. In probe tests in which the platform was removed, WT and DGKι−/− mice spent comparable amounts of time in the target quadrant (B) and showed similar numbers of exact crossings over the platform region (C). T, target; L, left; R, right; O, opposite. (D–G) A slower decrease in locomotor activity of DGKι−/− mice in open-field assays. Mice were allowed to explore a novel open field for 50 min, and their movements were quantified to obtain the total distance moved (D), speed of movement (E), and percentage of time spent in the centre region of the open field (G). n=9 for WT and KO; 4–7 months; *P<0.05, Student's t-test. (H, I) Normal anxiety-like behaviours of DGKι−/− mice in the elevated plus maze. Animals were allowed to explore an elevated plus maze for 5 min, and their movements were quantified to obtain the time spent in closed/open arms and number of entries to closed/open arms (n=9 for WT and KO; 3–6 months). (J) Normal motor learning of DGKι−/− mice in rotarod assays. Animals were trained 5 min/day for 6 days in the rotarod, and the latencies to fall were quantified (n=9 for WT and KO; 3–6 months).

We further tested the behavioural characteristics of DGKι−/− mice using open-field, elevated plus-maze, and rotarod assays. In the open-field assay, DGKι−/− mice showed normal locomotor activity, as measured by total distance moved and speed of movement (Figure 10D–F), indicating that DGKι−/− mice have normal levels of explorative and locomotor activity. Notably, however, DGKι−/− mice showed greater locomotor activity during the last 20 min of the open-field exploration compared with WT mice (Figure 10D). As the initial locomotion levels of DGKι−/− mice were normal, this result indicates that DGKι−/− mice may be slower to habituate to a novel environment. Spatial monitoring of mouse movements showed that DGKι−/− mice spent a similar amount of time in the centre region of the open field as WT mice (Figure 10G), suggesting that the level of anxiety-like behaviour in DGKι−/− mice is normal.

In the elevated plus-maze assay, the time spent by DGKι−/− mice in open and closed arms was similar to that of WT mice (Figure 10H). In addition, both WT and KO mice entered open and closed arms with similar frequencies (Figure 10I). These results suggest that DGKι−/− mice have normal levels of anxiety. In the rotarod assay, DGKι−/− mice showed similar levels of motor learning over the course of a 6-day training period (Figure 10J). Taken together, these results indicate that DGKι−/− mice are slower to habituation to a novel environment, but have normal levels of locomotor activity, anxiety, and motor coordination.

Discussion

Interaction of DGKι with PSD-95 family proteins

We have identified a novel PDZ-mediated interaction of DGKι with all four known PSD-95 family proteins that occurs both in vitro and in vivo. In addition, we found that DGKι is highly enriched in PSD fractions. We thus initially expected that PSD-95, a member of the PSD-95 family highly enriched at excitatory postsynaptic sites, might promote postsynaptic localization of DGKι for local DAG removal, as previously reported for DGKζ (Kim et al, 2009b). Contrary to this expectation, our results suggest that DGKι may have minimal functions at postsynaptic sites, as shown by the lack of changes in dendritic spines in DGKι−/− mice. It is thus possible that the loss of DGKι in dendritic spines might be compensated by DGKζ, a close relative of DGKι, although it seems that the lack of DGKζ cannot be compensated by DGKι (Kim et al, 2009b).

A notable feature of DGKι is that it is present in axons and presynaptic sites in addition to dendrites. This notion is supported by light and electron microscopic data, and by biochemical evidence for localization of DGKι to the synaptic vesicle (LP2) fraction, which contains many presynaptic proteins. More importantly, the loss of DGKι in mice is accompanied by several presynaptic functional abnormalities. DGKι interacts with all four known PSD-95 family proteins; of these, SAP97 and SAP102 are readily detected in axons, in addition to dendrites (Muller et al, 1995; El-Husseini et al, 2000; Aoki et al, 2001; Mok et al, 2002). Therefore, it is conceivable that DGKι interacts with SAP97 or SAP102 in axonal compartments or at nerve terminals. As SAP97 interacts with the KIF1Bα kinesin motor (Mok et al, 2002), SAP97 may contribute to axonal transport of DGKι by linking DGKι to microtubule-based motor proteins. PSD-95 and SAP97 are present in distinct nerve terminals in addition to axons and have been implicated in the formation of the cytoskeletal matrix of active zones (Kistner et al, 1993; Kim et al, 1995; Muller et al, 1995; Koulen et al, 1998a, 1998b; Schoch and Gundelfinger, 2006). It remains to be determined whether DGKι forms a complex with PSD-95 or SAP97 to act in concert at nerve terminals.

Regulation of synaptic transmission and presynaptic release by DGKι

SC-CA1 synapses in acute DGKι−/− slices show a small decrease in PPF and a bigger increase in evoked EPSCs. In addition, DGKι−/− autapses show an increase in evoked EPSC amplitude and a faster MK-801-induced decay of NMDA EPSCs. These results support the notion that DGKι deficiency leads to an increase in excitatory synaptic transmission. Whether this is attributable to an increase in presynaptic release needs a careful interpretation of the results. We observed the decrease in PPF only at a single inter-stimulus interval (20 ms) in DGKι−/− slices from 3- to 5-week-old mice. This is probably why the change in PPF was not accompanied by the changes in mEPSC or sEPSC frequency. However, we prefer to interpret this as data supporting a small increase in presynaptic release because we could observe a faster MK-801-induced decay of NMDA EPSCs, which is a type of data commonly used, along with PPF, to support that there is a change in presynaptic release probability (Hessler et al, 1993; Rosenmund et al, 1993; Weisskopf and Nicoll, 1995). In addition, there was a much greater change in PPF during mGluR-LTD at DGKι−/− synapses, which strongly supports the possible involvement of DGKι in the regulation of presynaptic release, although changes in PPF can be induced by diverse causes including postsynaptic modifications (Poncer and Malinow, 2001).

How might DGKι deficiency lead to such a change? The loss of DGKζ in dendritic spines suppresses the conversion of DAG to PA (Kim et al, 2009b). Similarly, the conversion of DAG—generated at nerve terminals by receptor-activated PLC—to PA might be slowed by the lack of DGKι. This would cause an abnormal increase in DAG concentration at the nerve terminal that could promote neurotransmitter release, likely by binding to and stimulating presynaptic DAG effectors. One prominent candidate is Munc13, which is a major downstream effector of DAG (Betz et al, 1998; Brose et al, 2004) and is well known for its role in presynaptic vesicle priming (Varoqueaux et al, 2002; Rosenmund et al, 2003). Another is PKC, which can contribute to DAG-dependent enhancement of transmitter release (Wierda et al, 2007; Lou et al, 2008). Alternatively, the lack of DAG-to-PA conversion may lead to a reduced production of PA, which can act as an independent signalling molecule for the regulation of activities or subcellular localization of diverse downstream proteins including p21-activated kinase 1 and phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase (PI(4)P 5-kinase) (Moritz et al, 1992; Jenkins et al, 1994; Bokoch et al, 1998; Stace and Ktistakis, 2006; Sakane et al, 2007; Kim et al, 2009a). Whether downstream effectors of PA regulate presynaptic release remains to be determined.

Regulation of mGluR-dependent LTD at neonatal synapses by DGKι

A major phenotypic feature of DGKι−/− mice was a decrease in DHPG-induced mGluR-LTD at neonatal (2 weeks) SC-CA1 synapses. In addition, DGKι−/− synapses do not show a DHPG-induced increase in PPF that is normally observed at WT synapses. Importantly, suppression of the increase in PPF associated with reduced DHPG-LTD at neonatal DGKι−/− synapses was normalized by inhibitors of the C1 domain and PKC.

Quantitatively, the DHPG-induced increase in PPF at a 40-ms inter-stimulus interval is decreased by ∼70% in DGKι−/− synapses (2 weeks) relative to WT (Figure 8). In addition, this decrease was observed in adult (6 weeks) slices, although to a lesser extent (∼60%) and at a different inter-stimulus interval (20 ms). In contrast, under basal conditions in the absence of DHPG, only a small (∼14%) decrease in PPF (20 ms interval) was observed at 3–5 weeks, but not at 2 or 6 weeks (Figure 5; Supplementary Figure S4A and B). These results suggest that DGKι has an important function in regulating presynaptic release during DHPG-induced mGluR-LTD, whereas it is less important for the regulation of basal release.

What signalling pathways might be involved in the reduction of DHPG-LTD at DGKι−/− synapses and its reversal by PKC inhibition? DHPG-LTD is known to involve, among many suggested mechanisms (Collingridge et al, 2010), a reduction in presynaptic release (Bolshakov and Siegelbaum, 1994; Oliet et al, 1997; Fitzjohn et al, 2001; Zakharenko et al, 2002; Feinmark et al, 2003; Rammes et al, 2003; Nosyreva and Huber, 2005). It is, therefore, conceivable that the decreased presynaptic release triggered by mGluR activation is counteracted by the increased presynaptic release caused by DGKι deficiency. An increased tone of DAG at DGKι−/− nerve terminals may act on DAG effectors such as Munc13 and PKC to promote presynaptic release (Rhee et al, 2002; Wierda et al, 2007; Lou et al, 2008). This suggests that, under normal circumstances, DGKι may have a function in removing DAG at nerve terminals in order to promote a normal decrease in transmitter release during presynaptic mGluR-LTD.

In conclusion, our study identifies PDZ-mediated interactions of DGKι with PSD-95 family proteins, and provides genetic evidence for novel involvements of DGKι in the regulation of presynaptic DAG signalling and neurotransmitter release during mGluR-dependent LTD.

Materials and methods

cDNA constructs and reagents

DGKι cDNAs (full-length, aa 1–1050 and Δ3, aa 1–1047) were amplified by PCR from a rat brain cDNA library and subcloned into pcDNA3-HA. Full-length rat PSD-93 and mouse SAP102 were subcloned into pEGFP-C1 (Invitrogen). The following constructs have been described: GW1-PSD-95 (Kim et al, 1995), EGFP-SAP97 (Choi et al, 2005a), and HA-DGKζ (Kim et al, 2009b). Ro-31-8220 and calphostin C were obtained from Calbiochem and Tocris/Sigma, respectively.

Antibodies

Polyclonal DGKι antibodies were generated by immunizing guinea pigs (1869 and 1873) and rabbits (1870 and 1871) with GST-DGKι (aa 1–173 for 1869) and GST-DGKι (aa 900–1050 for 1870, 1871, and 1873). Polyclonal antibodies against PSD-95 (1688, guinea pig), PSD-93 (1636, guinea pig), SAP97 (1443, guinea pig), and SAP102 (1447, guinea pig) were generated by using H6-PSD-95 PDZ1-2 (human), GST-PSD-93 (rat full length), GST-SAP97 (rat full length), and GST-SAP102 (mouse full length), respectively. CaMKIIα, β antibodies (rabbit and guinea pig polyclonal 1299 and 1301) were generated using GST-CaMKIIα (human full length) as immunogen. Other antibodies have been described: DGKζ (1521) (Kim et al, 2009b), PSD-95 (SM55) (Choi et al, 2002), SAP97 (B9591) (Kim and Sheng, 1996), PSD-93 (1634) (Kim et al, 2009c), SAP102 (1445) (Choi et al, 2005a), SynGAP (1682) (Kim et al, 2009c), CASK (1640) (Kim et al, 2009c), NR2A (22284), NR2B (21266) (Sheng et al, 1994), GluR1 (1193), GluR2 (1195) (Kim et al, 2009c), and pan-Shank (1123) (Lim et al, 2001). The following antibodies were purchased from commercial sources: monoclonal PSD-95 (Affinity Bioreagents), HA, EGFP, DGKγ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), synaptophysin, synaptotagmin I, GAP-43, syntaxin 1, α-tubulin, β-actin, MAP2, NF200 (Sigma), synapsin I (Chemicon), GAD65 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), gephyrin (Synaptic Systems), DGKθ, SNAP-25, Rab3 (BD Transduction Laboratories), and NR2A (Zymed).

Animals

Sprague–Dawley rats (280–300 g) were used for rat neuron culture, in vivo coimmunoprecipitation, immunoblot analysis, and electron microscopy. DGKι−/− mice, which were generated using R1 ES cells and back-crossed with C57/BL6, have been previously described (Regier et al, 2005). WT littermates were used as controls in experiments for immunoblot analyses (Figure 4), autapses analyses (Figure 6), PPF measurements (Figures 8 and 9), and behavioural analyses (Figure 10). Other experiments used littermates or age-matched controls.

Coimmunoprecipitation and subcellular and PSD fractions

Transfected HEK293T cells were extracted with phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% Triton X-100 and incubated with HA-agarose (Sigma). For in vivo coimmunoprecipitation, the crude synaptosomal fraction of adult rat brains was solubilized with DOC buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 1% sodium deoxycholate, pH 9.0). Subcellular fractions of whole rat brains were prepared as described previously (Huttner et al, 1983). PSD fractions were purified as described previously (Carlin et al, 1980; Cho et al, 1992).

Neuron culture, transfection, and analysis of spine localization

Cultured rat neurons prepared from embryonic day 18 were maintained in neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 and transfected by the Calphos transfection kit (Invitrogen). Spine localization of DGKι was determined by comparing DGKι signals in a spine and a nearby dendrite; 3–5 spine/dendrite ratios from a single neuron.

Electron microscopy

Hippocampal and cerebellar sections of rat brains (60 μm; 9 weeks) were incubated overnight with DGKι antibodies (1871; 4 μg/ml) and biotinylated secondary antibodies for 2 h. The sections were incubated with ExtrAvidin peroxidase (Sigma), and the immunoperoxidase was revealed by nickel-intensified 3,30-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride. Areas containing the pyramidal cell layer and the stratum radiatum region of the CA1 region of the hippocampus, and the molecular, Purkinje, and granular layers of the cerebellum were trimmed. Images on a Hitachi H 7500 electron microscope (Hitachi) were captured using Digital Montage software driving a MultiScan cooled CCD camera (ES1000W; Gatan).

Electrophysiology

To measure field potentials, 400 μm transverse hippocampal slices were prepared from mice. Slices were left to recover for 1 h before recording in oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM) 124 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.23 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 10 dextrose, 1.5 MgCl2, and 2.5 CaCl2. CA1 field potentials evoked by SC stimulation were measured as previously described (Hayashi et al, 2004). LTP was induced by TBS, which consisted of four trains containing 10 brief bursts (each with four pulses at 100 Hz) of stimuli delivered every 200 ms. LTD was induced by SP-LFS (1 Hz, 900 stimuli), PP-LFS (1 Hz, 900 paired stimuli, stimuli interval of 50 ms), or 10 min application of 100 μM (RS)-DHPG (Tocris). For whole-cell experiments, CA1 pyramidal cells (300 μm horizontal slices) were held at −70 mV using a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments) with low resistance patch pipettes (2–4 MΩ). Pipette solutions contained (in mM) 110 Cs-gluconate, 30 CsCl, 20 HEPES, 4 MgATP, 0.3 NaGTP, 4 NaVitC, and 0.5 EGTA (10 EGTA for AMPAR versus NMDAR ratio). For mEPSC measurements, 0.5 μM TTX (Tocris) and 20 μM bicuculline (Tocris) were added to ACSF to inhibit spontaneous action potential-mediated synaptic currents and IPSCs, respectively. We measured mEPSCs for ∼170 s for each recording (∼20 mini-events/recording); total amounts of time for the recording and the numbers of mini-events analysed were 2169 s and 217, respectively, for WT cells (n=13) and 3076 s and 400, respectively, for KO cells (n=18). Data were acquired using Clampex 9.2 (Molecular Devices) and analysed using custom macros written in Igor (Wavemetrics). Recordings showing >20% changes in series resistance were discarded. For AMPA/NMDA ratio experiments, EPSCs were evoked by electrical stimulation of axons in stratum radiatum at a frequency of 0.06 Hz with electrodes filled with ACSF. AMPAR-mediated EPSCs were recorded at a holding potential of −70 mV with the same pipette solution as for mEPSC recording, and 100 μM picrotoxin (Tocris) was added to ACSF to inhibit IPSCs. After recording AMPAR-mediated currents, NMDAR-mediated EPSCs were isolated by changing holding potential to +40 mV and adding 10 μM CNQX to ACSF. A total of 25–30 EPSCs were averaged to obtain the AMPAR/NMDAR EPSC ratio. Signals were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz with Digidata 1322A (Axon Instruments).

Autaptic cell culture and electrophysiology

Autaptic cultures of hippocampal neurons and recording solutions for electrophysiological experiments were prepared as previously described (Jockusch et al, 2007). Cells at 11–15 DIV were whole-cell patch clamped at –70 mV with an Axon 700B (Axon Instruments) amplifier controlled by the Clampex 10.1 software. RRP sizes were determined by application of 0.5 M sucrose solution (HSS). EPSCs were evoked by depolarization of the cell membrane potential from −70 to 0 mV for 2 ms. The patch-pipette solution contained (in mM) 146 K-gluconate, 18 Hepes, 1 EGTA, 4.6 MgCl2, 4 NaATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, 15 creatine phosphate, and 5 U/ml phosphocreatine kinase (315–320 mOsmol/l, pH 7.3). The extracellular recording solution contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 2.4 KCl, 10 Hepes, 4 CaCl2, and 4 MgCl2 (320 mOsmol/l, pH 7.3). All chemicals, except for TTX (Tocris Cookson) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Recordings were analysed using the Axograph X software.

Diolistic spine labelling and image analysis

Mouse brain slices (150 μm) were labelled by the ballistic delivery of lipophilic dye DiI (Molecular Probes) (Gan et al, 2000). Z-stack images of DiI-labelled CA1 pyramidal neurons were obtained using a Zeiss 5 Pascal confocal microscope (× 63 objective). Analysed spines were from secondary apical dendrites located at least 25 μm outside the bifurcation point in the proximal stratum radiatum (dendritic length of 40–80 μm from 1 or 2 dendrites per neuron). Spines were defined as protrusions with a bulbous head wider than the neck and with a length >0.5 μm. Spine lengths were measured from the tip of spine head to the point of attachment to the dendrite. Quantitative spine analyses were performed using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices) in a blind manner.

Morris water-maze, open-field, elevated plus-maze, and rotarod assays

Details on these methods are described in Supplementary data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH R01-CA95463 grant (to MKT), the Neuroscience Program (to S-YC; 2009-0081468), and the National Creative Research Initiative Program of the Korean Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (to EK). A part of this work was technically supported by the core facility service of the 21C Frontier Brain Research Center.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aoki C, Miko I, Oviedo H, Mikeladze-Dvali T, Alexandre L, Sweeney N, Bredt DS (2001) Electron microscopic immunocytochemical detection of PSD-95, PSD-93, SAP-102, and SAP-97 at postsynaptic, presynaptic, and nonsynaptic sites of adult and neonatal rat visual cortex. Synapse 40: 239–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz A, Ashery U, Rickmann M, Augustin I, Neher E, Sudhof TC, Rettig J, Brose N (1998) Munc13-1 is a presynaptic phorbol ester receptor that enhances neurotransmitter release. Neuron 21: 123–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokoch GM, Reilly AM, Daniels RH, King CC, Olivera A, Spiegel S, Knaus UG (1998) A GTPase-independent mechanism of p21-activated kinase activation. Regulation by sphingosine and other biologically active lipids. J Biol Chem 273: 8137–8144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolshakov VY, Siegelbaum SA (1994) Postsynaptic induction and presynaptic expression of hippocampal long-term depression. Science 264: 1148–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose N, Betz A, Wegmeyer H (2004) Divergent and convergent signaling by the diacylglycerol second messenger pathway in mammals. Curr Opin Neurobiol 14: 328–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose N, Rosenmund C (2002) Move over protein kinase C, you've got company: alternative cellular effectors of diacylglycerol and phorbol esters. J Cell Sci 115: 4399–4411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting M, Tang W, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM (1996) Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel human diacylglycerol kinase zeta. J Biol Chem 271: 10230–10236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin RK, Grab DJ, Cohen RS, Siekevitz P (1980) Isolation and characterization of postsynaptic densities from various brain regions: enrichment of different types of postsynaptic densities. J Cell Biol 86: 831–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho KO, Hunt CA, Kennedy MB (1992) The rat brain postsynaptic density fraction contains a homolog of the Drosophila discs-large tumor suppressor protein. Neuron 9: 929–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Ko J, Park E, Lee JR, Yoon J, Lim S, Kim E (2002) Phosphorylation of stargazin by protein kinase A regulates its interaction with PSD-95. J Biol Chem 277: 12359–12363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Ko J, Racz B, Burette A, Lee JR, Kim S, Na M, Lee HW, Kim K, Weinberg RJ, Kim E (2005a) Regulation of dendritic spine morphogenesis by insulin receptor substrate 53, a downstream effector of Rac1 and Cdc42 small GTPases. J Neurosci 25: 869–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SY, Chang J, Jiang B, Seol GH, Min SS, Han JS, Shin HS, Gallagher M, Kirkwood A (2005b) Multiple receptors coupled to phospholipase C gate long-term depression in visual cortex. J Neurosci 25: 11433–11443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge GL, Peineau S, Howland JG, Wang YT (2010) Long-term depression in the CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci 11: 459–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creager R, Dunwiddie T, Lynch G (1980) Paired-pulse and frequency facilitation in the CA1 region of the in vitro rat hippocampus. J Physiol 299: 409–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo G, De Camilli P (2006) Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature 443: 651–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, McIntyre TM, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM (1998a) The cloning and developmental regulation of murine diacylglycerol kinase zeta. FEBS Lett 429: 109–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Traer E, McIntyre TM, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM (1998b) The cloning and characterization of a novel human diacylglycerol kinase, DGKiota. J Biol Chem 273: 32746–32752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Husseini AE, Topinka JR, Lehrer-Graiwer JE, Firestein BL, Craven SE, Aoki C, Bredt DS (2000) Ion channel clustering by membrane-associated guanylate kinases. Differential regulation by N-terminal lipid and metal binding motifs. J Biol Chem 275: 23904–23910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinmark SJ, Begum R, Tsvetkov E, Goussakov I, Funk CD, Siegelbaum SA, Bolshakov VY (2003) 12-lipoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid mediate metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long-term depression at hippocampal CA3-CA1 synapses. J Neurosci 23: 11427–11435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzjohn SM, Doherty AJ, Collingridge GL (2006) Promiscuous interactions between AMPA-Rs and MAGUKs. Neuron 52: 222–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzjohn SM, Kingston AE, Lodge D, Collingridge GL (1999) DHPG-induced LTD in area CA1 of juvenile rat hippocampus; characterisation and sensitivity to novel mGlu receptor antagonists. Neuropharmacology 38: 1577–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzjohn SM, Palmer MJ, May JE, Neeson A, Morris SA, Collingridge GL (2001) A characterisation of long-term depression induced by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation in the rat hippocampus in vitro. J Physiol 537: 421–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frere SG, Di Paolo G (2009) A lipid kinase controls the maintenance of dendritic spines. EMBO J 28: 999–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan WB, Grutzendler J, Wong WT, Wong RO, Lichtman JW (2000) Multicolor ‘DiOlistic' labeling of the nervous system using lipophilic dye combinations. Neuron 27: 219–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordge PC, Ryves WJ (1994) Inhibitors of protein kinase C. Cell Signal 6: 871–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto K, Nakano T, Hozumi Y (2006) Diacylglycerol kinase and animal models: the pathophysiological roles in the brain and heart. Adv Enzyme Regul 46: 192–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi ML, Choi SY, Rao BS, Jung HY, Lee HK, Zhang D, Chattarji S, Kirkwood A, Tonegawa S (2004) Altered cortical synaptic morphology and impaired memory consolidation in forebrain-specific dominant-negative PAK transgenic mice. Neuron 42: 773–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessler NA, Shirke AM, Malinow R (1993) The probability of transmitter release at a mammalian central synapse. Nature 366: 569–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne EA, Dell'Acqua ML (2007) Phospholipase C is required for changes in postsynaptic structure and function associated with NMDA receptor-dependent long-term depression. J Neurosci 27: 3523–3534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttner WB, Schiebler W, Greengard P, De Camilli P (1983) Synapsin I (protein I), a nerve terminal-specific phosphoprotein. III. Its association with synaptic vesicles studied in a highly purified synaptic vesicle preparation. J Cell Biol 96: 1374–1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins GH, Fisette PL, Anderson RA (1994) Type I phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase isoforms are specifically stimulated by phosphatidic acid. J Biol Chem 269: 11547–11554 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jockusch WJ, Speidel D, Sigler A, Sorensen JB, Varoqueaux F, Rhee JS, Brose N (2007) CAPS-1 and CAPS-2 are essential synaptic vesicle priming proteins. Cell 131: 796–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith D, El-Husseini A (2008) Excitation control: balancing PSD-95 function at the synapse. Front Mol Neurosci 1: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp N, McQueen J, Faulkes S, Bashir ZI (2000) Different forms of LTD in the CA1 region of the hippocampus: role of age and stimulus protocol. Eur J Neurosci 12: 360–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Niethammer M, Rothschild A, Jan YN, Sheng M (1995) Clustering of Shaker-type K+ channels by interaction with a family of membrane-associated guanylate kinases. Nature 378: 85–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Sheng M (1996) Differential K+ channel clustering activity of PSD-95 and SAP97, two related membrane-associated putative guanylate kinases. Neuropharmacology 35: 993–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Yang J, Kim E (2009a) Diacylglycerol kinases in the regulation of dendritic spines. J Neurochem 112: 577–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Yang J, Zhong XP, Kim MH, Kim YS, Lee HW, Han S, Choi J, Han K, Seo J, Prescott SM, Topham MK, Bae YC, Koretzky G, Choi SY, Kim E (2009b) Synaptic removal of diacylglycerol by DGKzeta and PSD-95 regulates dendritic spine maintenance. EMBO J 28: 1170–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MH, Choi J, Yang J, Chung W, Kim JH, Paik SK, Kim K, Han S, Won H, Bae YS, Cho SH, Seo J, Bae YC, Choi SY, Kim E (2009c) Enhanced NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission, enhanced long-term potentiation, and impaired learning and memory in mice lacking IRSp53. J Neurosci 29: 1586–1595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistner U, Wenzel BM, Veh RW, Cases-Langhoff C, Garner AM, Appeltauer U, Voss B, Gundelfinger ED, Garner CC (1993) SAP90, a rat presynaptic protein related to the product of the Drosophila tumor suppressor gene dlg-A. J Biol Chem 268: 4580–4583 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi E, Nakano H, Morimoto M, Tamaoki T (1989) Calphostin C (UCN-1028C), a novel microbial compound, is a highly potent and specific inhibitor of protein kinase C. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 159: 548–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulen P, Fletcher EL, Craven SE, Bredt DS, Wassle H (1998a) Immunocytochemical localization of the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 in the mammalian retina. J Neurosci 18: 10136–10149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulen P, Garner CC, Wassle H (1998b) Immunocytochemical localization of the synapse-associated protein SAP102 in the rat retina. J Comp Neurol 397: 326–336 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S, Sala C, Yoon J, Park S, Kuroda S, Sheng M, Kim E (2001) Sharpin, a novel postsynaptic density protein that directly interacts with the shank family of proteins. Mol Cell Neurosci 17: 385–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou X, Korogod N, Brose N, Schneggenburger R (2008) Phorbol esters modulate spontaneous and Ca2+-evoked transmitter release via acting on both Munc13 and protein kinase C. J Neurosci 28: 8257–8267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo B, Regier DS, Prescott SM, Topham MK (2004) Diacylglycerol kinases. Cell Signal 16: 983–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok H, Shin H, Kim S, Lee JR, Yoon J, Kim E (2002) Association of the kinesin superfamily motor protein KIF1Balpha with postsynaptic density-95 (PSD-95), synapse-associated protein-97, and synaptic scaffolding molecule PSD-95/discs large/zona occludens-1 proteins. J Neurosci 22: 5253–5258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz A, De Graan PN, Gispen WH, Wirtz KW (1992) Phosphatidic acid is a specific activator of phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate kinase. J Biol Chem 267: 7207–7210 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moult PR, Gladding CM, Sanderson TM, Fitzjohn SM, Bashir ZI, Molnar E, Collingridge GL (2006) Tyrosine phosphatases regulate AMPA receptor trafficking during metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated long-term depression. J Neurosci 26: 2544–2554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller BM, Kistner U, Veh RW, Cases-Langhoff C, Becker B, Gundelfinger ED, Garner CC (1995) Molecular characterization and spatial distribution of SAP97, a novel presynaptic protein homologous to SAP90 and the Drosophila discs-large tumor suppressor protein. J Neurosci 15: 2354–2366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll RA, Oliet SH, Malenka RC (1998) NMDA receptor-dependent and metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent forms of long-term depression coexist in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells. Neurobiol Learn Mem 70: 62–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyreva ED, Huber KM (2005) Developmental switch in synaptic mechanisms of hippocampal metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long-term depression. J Neurosci 25: 2992–3001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliet SH, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA (1997) Two distinct forms of long-term depression coexist in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells. Neuron 18: 969–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak DT, Sheng M (2003) Targeted protein degradation and synapse remodeling by an inducible protein kinase. Science 302: 1368–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak DT, Yang S, Rudolph-Correia S, Kim E, Sheng M (2001) Regulation of dendritic spine morphology by SPAR, a PSD-95-associated RapGAP. Neuron 31: 289–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer MJ, Irving AJ, Seabrook GR, Jane DE, Collingridge GL (1997) The group I mGlu receptor agonist DHPG induces a novel form of LTD in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 36: 1517–1532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poncer JC, Malinow R (2001) Postsynaptic conversion of silent synapses during LTP affects synaptic gain and transmission dynamics. Nat Neurosci 4: 989–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammes G, Palmer M, Eder M, Dodt HU, Zieglgansberger W, Collingridge GL (2003) Activation of mGlu receptors induces LTD without affecting postsynaptic sensitivity of CA1 neurons in rat hippocampal slices. J Physiol 546: 455–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DS, Higbee J, Lund KM, Sakane F, Prescott SM, Topham MK (2005) Diacylglycerol kinase iota regulates Ras guanyl-releasing protein 3 and inhibits Rap1 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 7595–7600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Harde M, Stanton PK (1998) Postsynaptic phospholipase C activity is required for the induction of homosynaptic long-term depression in rat hippocampus. Neurosci Lett 252: 155–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee JS, Betz A, Pyott S, Reim K, Varoqueaux F, Augustin I, Hesse D, Sudhof TC, Takahashi M, Rosenmund C, Brose N (2002) Beta phorbol ester- and diacylglycerol-induced augmentation of transmitter release is mediated by Munc13s and not by PKCs. Cell 108: 121–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SG (2001) Regulation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Annu Rev Biochem 70: 281–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C, Clements JD, Westbrook GL (1993) Nonuniform probability of glutamate release at a hippocampal synapse. Science 262: 754–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C, Rettig J, Brose N (2003) Molecular mechanisms of active zone function. Curr Opin Neurobiol 13: 509–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouach N, Nicoll RA (2003) Endocannabinoids contribute to short-term but not long-term mGluR-induced depression in the hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci 18: 1017–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakane F, Imai S, Kai M, Yasuda S, Kanoh H (2007) Diacylglycerol kinases: why so many of them? Biochim Biophys Acta 1771: 793–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch S, Gundelfinger ED (2006) Molecular organization of the presynaptic active zone. Cell Tissue Res 326: 379–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M, Cummings J, Roldan LA, Jan YN, Jan LY (1994) Changing subunit composition of heteromeric NMDA receptors during development of rat cortex. Nature 368: 144–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M, Hoogenraad CC (2007) The postsynaptic architecture of excitatory synapses: a more quantitative view. Annu Rev Biochem 76: 823–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JB, Nagy G, Varoqueaux F, Nehring RB, Brose N, Wilson MC, Neher E (2003) Differential control of the releasable vesicle pools by SNAP-25 splice variants and SNAP-23. Cell 114: 75–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stace CL, Ktistakis NT (2006) Phosphatidic acid- and phosphatidylserine-binding proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1761: 913–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternweis PC, Smrcka AV, Gutowski S (1992) Hormone signalling via G-protein: regulation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis by Gq. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 336: 35–41; discussion 41–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhof TC (2004) The synaptic vesicle cycle. Annu Rev Neurosci 27: 509–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y, Hori N, Carpenter DO (2003) The mechanism of presynaptic long-term depression mediated by group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. Cell Mol Neurobiol 23: 187–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topham MK, Epand RM (2009) Mammalian diacylglycerol kinases: molecular interactions and biological functions of selected isoforms. Biochim Biophys Acta 1790: 416–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoqueaux F, Sigler A, Rhee JS, Brose N, Enk C, Reim K, Rosenmund C (2002) Total arrest of spontaneous and evoked synaptic transmission but normal synaptogenesis in the absence of Munc13-mediated vesicle priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 9037–9042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washbourne P, Thompson PM, Carta M, Costa ET, Mathews JR, Lopez-Bendito G, Molnar Z, Becher MW, Valenzuela CF, Partridge LD, Wilson MC (2002) Genetic ablation of the t-SNARE SNAP-25 distinguishes mechanisms of neuroexocytosis. Nat Neurosci 5: 19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe AM, Carlisle HJ, O'Dell TJ (2002) Postsynaptic induction and presynaptic expression of group 1 mGluR-dependent LTD in the hippocampal CA1 region. J Neurophysiol 87: 1395–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf MG, Nicoll RA (1995) Presynaptic changes during mossy fibre LTP revealed by NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic responses. Nature 376: 256–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierda KD, Toonen RF, de Wit H, Brussaard AB, Verhage M (2007) Interdependence of PKC-dependent and PKC-independent pathways for presynaptic plasticity. Neuron 54: 275–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita S, Mochizuki N, Ohba Y, Tobiume M, Okada Y, Sawa H, Nagashima K, Matsuda M (2000) CalDAG-GEFIII activation of Ras, R-ras, and Rap1. J Biol Chem 275: 25488–25493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharenko SS, Zablow L, Siegelbaum SA (2002) Altered presynaptic vesicle release and cycling during mGluR-dependent LTD. Neuron 35: 1099–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JJ, Qin Y, Zhao M, Van Aelst L, Malinow R (2002) Ras and Rap control AMPA receptor trafficking during synaptic plasticity. Cell 110: 443–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.