Abstract

Aim

The aim of the study was to determine the potential for KV1 potassium channel blockers as inhibitors of human neoinitimal hyperplasia.

Methods and results

Blood vessels were obtained from patients or mice and studied in culture. Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction and immunocytochemistry were used to detect gene expression. Whole-cell patch-clamp, intracellular calcium measurement, cell migration assays, and organ culture were used to assess channel function. KV1.3 was unique among the KV1 channels in showing preserved and up-regulated expression when the vascular smooth muscle cells switched to the proliferating phenotype. There was strong expression in neointimal formations. Voltage-dependent potassium current in proliferating cells was sensitive to three different blockers of KV1.3 channels. Calcium entry was also inhibited. All three blockers reduced vascular smooth muscle cell migration and the effects were non-additive. One of the blockers (margatoxin) was highly potent, suppressing cell migration with an IC50 of 85 pM. Two of the blockers were tested in organ-cultured human vein samples and both inhibited neointimal hyperplasia.

Conclusion

KV1.3 potassium channels are functional in proliferating mouse and human vascular smooth muscle cells and have positive effects on cell migration. Blockers of the channels may be useful as inhibitors of neointimal hyperplasia and other unwanted vascular remodelling events.

Keywords: Potassium channels, Vascular smooth muscle cell, Neointimal hyperplasia, Cell migration

1. Introduction

Smooth muscle cells are well known for their contractile phenotype which determines the calibre of blood vessels; regulating blood pressure and local tissue perfusion. However, the cells also retain plasticity throughout the life, enabling marked transition away from contractile behaviour to motility, invasion, and proliferation. Plasticity is important in vascular development, adaptation, and response to injury.1 One consequence is the phenomenon of neointimal hyperplasia, which is the movement and proliferation of smooth muscle cells into the luminal area of a blood vessel, generating a new inner structure that can ultimately occlude blood flow.1–4 It is observed in a variety of situations but is particularly striking for its tendency to cause failure of interventional clinical procedures that include the placement of stents and bypass grafts.

Several mechanisms of smooth muscle plasticity have been determined,1 but knowledge remains incomplete. An important feature is changes in the types of ion channel as the cells switch from the contractile to the proliferating phenotype.5 The intracellular calcium ion (Ca2+) concentration is one of the key parameters controlled by the ion channels.6,7 The removal of extracellular Ca2+ or addition of Ca2+ channel blockers inhibits smooth muscle cell proliferation.8–10 Significantly, as the cells switch from the contractile to proliferating phenotype, there is loss of CaV1.2 (the L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel α-subunit) but retention or up-regulation of other types of Ca2+ channels, including the channel components TRPC1, STIM1, and Orai1.4,11–17 The suppression of TRPC channel function inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation, whereas suppression of STIM1 or Orai1 has preferential inhibitory effects on cell migration.15,17 Importantly, an anti-TRPC1-blocking antibody inhibited human neointimal hyperplasia4 and knock-down of STIM1 inhibited neointimal formation in a rat model.18 A consequence of the change to these other types of Ca2+ channel is that it is no longer membrane depolarization that is the trigger for Ca2+ entry, as is the situation in contractile cells where the L-type Ca2+ channels predominate; instead, it is hyperpolarization that causes increased Ca2+ influx by increasing the electrical driving force on Ca2+ entry through channels that are not gated by depolarization but are active across a wide range of voltages, which is the case with channels generated by TRPC, STIM1, or Orai1 proteins. Therefore, as in immune cells, ion channels that cause hyperpolarization become key players.19 Potassium ion (K+) channels are primary candidates for mediating the effect.

As with Ca2+ channels, there are changes in K+ channel type as vascular smooth muscle cells switch from the contractile to proliferating phenotype.5 As first described by Neylon et al.,20 there is a transition from the large conductance KCa1.1 (BKCa) channel to the intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel KCa3.1 (IKCa). It is thought that a reason for the change is that KCa3.1 is more active at negative membrane potentials, enabling it to confer the hyperpolarization necessary to drive Ca2+ entry. As predicted, inhibitors of KCa3.1 suppress vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, stenosis following injury, and neointimal hyperplasia.20–25 Intriguingly, KCa3.1 is also used by activated lymphocytes to drive Ca2+ entry.19,26 In some situations, immune cells of this type also use one more K+ channel for driving Ca2+ entry, a member of the KV1 family called KV1.3.19,27,28 In this study, we investigated the relevance of KV1 channels to the proliferating vascular smooth muscle cell and human neointimal hyperplasia.

2. Methods

2.1. Tissues: cell and organ culture

For murine experiments, 8-week male C57/BL6 mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation and cervical dislocation in accordance with the Code of Practice, UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. The thoracic aorta was removed and placed in ice-cold Hanks' solution. Endothelium was removed by brief luminal perfusion with 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 in water and the adventitia was removed by fine dissection.29 Smooth muscle cells were enzymatically isolated29 and studied immediately or after 14 days of culture (without passage) when cells were clearly proliferating and non-contractile. Freshly isolated mouse cells contracted strongly in response to extracellular ATP, whereas cells in culture showed no contraction or change in shape. Freshly discarded human saphenous veins were obtained anonymously and with informed consent from adult patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery and with ethical approval from Leeds Teaching Hospitals Local Research Ethics Committee. Smooth muscle cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, penicillin/streptomycin, and l-glutamine at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator; experiments were performed on cells passaged two to five times. All experiments on the intact vein involved paired comparisons of at least two adjacent vein segments from the same patient (one in control conditions and the other in the presence of the blocker). After 14 days of organ culture, neointimal hyperplasia was the new cellular layer that developed on the luminal aspect of the internal elastic lamina and was quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, USA).22 All cells described as smooth muscle cells stained positively with an antibody to smooth muscle α-actin and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1).30 The investigation conforms with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996) and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Quantification of channel expression

Methods were similar to those described previously.22,29 Briefly, for quantification of mRNA abundance, total RNA was first extracted using Tri-reagent (Sigma) and DNase-treated RNA reverse-transcribed using enhanced AMV enzyme (Sigma). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was then performed and its specificity verified by melt curve analysis, gel electrophoresis, controls in which reverse transcriptase (RT) was omitted, and direct sequencing of PCR products (Lark, UK). RNA abundance was normalized to the abundance of 16S mitochondrial rRNA, which was also analysed by real-time PCR and was not different between any of the data sets. Sequences of PCR primers are given in Supplementary material online, Table S1. Human cerebral cortex mRNA was from Ambion. For immunodetection of KV1.3 protein, vessels were fixed in 10% formalin for ≥24 h and embedded in paraffin wax. Five-micrometre sections were cut, hot-plated, dried overnight, and stored at 37°C until use. Dewaxing, rehydration, permeabilization, haematoxylin, and antibody staining using ABC kit (Vector Labs) were according to the standard protocols. KV1.3 was detected using a monoclonal anti-KV1.3 antibody (clone L23/27; Antibodies Incorp., Davis, USA) and a rabbit anti-KV1.3 polyclonal antibody.31

2.3. Ionic current and intracellular Ca2+ recordings

Conventional whole-cell recording was performed at ∼21°C using an Axopatch 200B amplifier and pCLAMP-8 software (Molecular Devices). Signals were filtered at 1 kHz and sampled at 2 kHz. Patch pipettes had resistance of 3–5 MΩ. To the bath solution containing (in mM) NaCl (135), KCl (5), d-glucose (8), HEPES (10), and MgCl2 (4), 1 μM gadolinium chloride (GdCl3) was added to suppress background current. The patch pipette solution contained (in mM): NaCl, 5; KCl, 130; HEPES, 10; Na2ATP, 3; MgCl2, 2; and EGTA, 5. The pH of solutions was titrated to pH 7.4 using NaOH. BSA (0.1%) was continuously present to minimize the non-specific binding of margatoxin. The solvent for correolide C, psora-4, and Tram-34 was DMSO (≤0.1% v/v). For recording from HEK 293 cells stably expressing human KCa3.1, the patch pipette solution contained (in mM): KCl, 144; HEPES, 10; MgCl2, 1.205; CaCl2, 7.625; EGTA, 10; and the pH was titrated to pH 7.2 using KOH; free Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations were 300 nM and 1 mM, respectively. The bath solution was as indicated above. Intracellular Ca2+ was measured using fura-2AM (Invitrogen) on a real-time fluorescence 96-well plate reader (FlexStation, Molecular Devices). The recording medium contained (mmole/L): NaCl, 130; KCl, 5; d-glucose, 8; HEPES, 10; MgCl2, 1.2; titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH. Ca2+ was added to the medium as indicated in the figure legend.

2.4. Linear wound and cell migration assays

Smooth muscle cells were cultured on 24- (human) or 96 (mouse)-well plates to confluency and a 0.3 mm-wide scrape generated across each well (linear wound). Cells were treated with KV1.3 blockers for 48 h. Migration assays were performed using a modified Boyden chamber containing polycarbonate inserts with 8 µm pores (BD Biosciences, Oxford, UK). In brief, 1 × 105 cells were loaded in the upper chamber in DMEM supplemented with 0.4% FCS. The lower chamber contained 0.4% FCS supplemented with 10 ng/mL PDGF-BB and 10 ng/mL IL-1α (Invitrogen). After incubation for 8 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator (with the blocker or vehicle), cells were scraped from the upper surface, duplicate membranes fixed, and migrated cells stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Cells were counted in 10 random fields, leading to an average number of cells per condition per patient.

2.5. Data analysis

Averaged data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data sets were obtained in test and control pairs even though single control bars are shown in the figures. Statistical analysis employed Student's t-tests with significant difference indicated by an asterisk (P < 0.05) and no significant difference by NS. Numbers of experiments are indicated by n (independent experiments on different human or mouse samples, or numbers of individual recordings for patch-clamp studies) and, in some cases, also N (number of replicates within an experiment, e.g. wells in a plate). RT–PCR and tissue staining were repeated independently on samples from three patients, yielding similar results.

3. Results

3.1. Up-regulated KV1.3 mRNA in proliferating mouse aorta smooth muscle cells

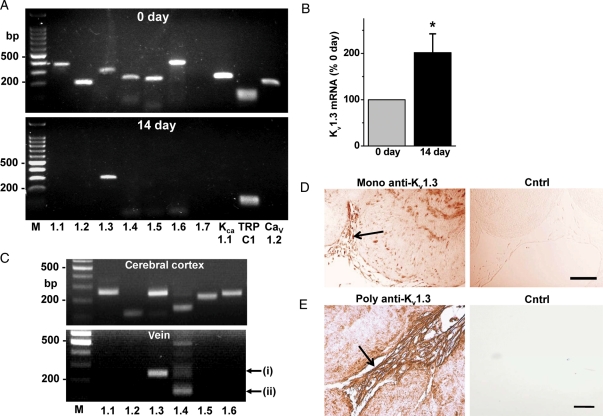

A comparison was made of vascular smooth muscle cells in the contractile phenotype (acutely after isolation from the aorta) and the proliferating phenotype (in primary culture for 14 days). In contractile cells, RT–PCR detected mRNA species encoding six of the seven KV1 channels, but in proliferating cells, only mRNA encoding KV1.3 was detected (Figure 1A). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis showed that mRNA encoding KV1.3 increased in abundance in the proliferating cells (Figure 1B; see Supplementary material online, Figure S2). Expression of three other ion channels was detected for comparison (Figure 1A): consistent with previous reports, expression of mRNAs encoding KCa1.1 and CaV1.2 was lost, whereas expression of mRNA encoding TRPC1 was retained.4,11–13 Therefore, the experimental system reflected established features of vascular remodelling and the data suggest that KV1.3 mRNA is an exception among the KV1 mRNA species, being retained and up-regulated when vascular smooth muscle cells switch to the proliferating phenotype.

Figure 1.

KV1.3 expression in proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells. (A and B) Mouse cells. (C–E) Human cells and tissue. (A) Gels showing typical RT–PCR products from RNA of contractile cells (0 day, upper panel) and proliferating cells (14 days, lower panel). In each panel, the 100 bp DNA markers (M) are on the left and the lanes for the encoded channels are ordered from KV1.1 to CaV1.2. See Supplementary material online, Table S1 for predicted PCR amplicon sizes. (B) Paired mean data for KV1.3 mRNA abundance (n = 9) showing doubling of expression in 14-day cells. (C) Typical RT–PCR products from RNA of the human cerebral cortex (upper gel, positive control) and saphenous vein smooth muscle cells (lower gel). PCR products for KV1.3 (i) and KV1.4 (ii) mRNAs are highlighted by arrows. Each is a representative of three independent experiments. (D and E) KV1.3 protein detection in neointima (arrows) of human saphenous vein segments after organ culture. Sections were stained with monoclonal (D) or polyclonal (E) antibody targeted to KV1.3. The controls were mouse IgG (D) and the absence of primary antibody (E). Increased intensity in the images indicates increased positive staining. The control image in (E) contains a vein section but it is very faint relative to the vein stained with anti-KV1.3 antibody. Scale bars are 50 μm; Cntrl, control.

3.2. KV1.3 mRNA and protein in proliferating human vein smooth muscle cells

To investigate the relevance to human neointimal hyperplasia, mRNA was isolated from cultures of human saphenous vein smooth muscle cells. With regard to the KV1 channels, only mRNA encoding KV1.3 was robustly detected (Figure 1C, i). Small amounts of mRNA encoding KV1.4 may have been present but a specific product could not be isolated, suggesting exceptionally low expression (Figure 1C, ii). Freshly isolated cells from the human vein were not investigated because of concern that the cells would already be partially remodelled in samples from such patients. To determine the relevance to newly remodelling smooth muscle cells in situ, we grew neointimal formations within segments of the human saphenous vein; these formations are variable in shape and less dense than the original vessel, containing almost exclusively smooth muscle cells.22 KV1.3 protein was detected using two different anti-KV1.3 antibodies: a mouse monoclonal antibody (Figure 1D) and a rabbit polyclonal antibody (Figure 1E). With either detection antibody, expression of KV1.3 was found to be higher in the neointima compared with the pre-existing vein (Figure 1D and E).

3.3. Function of KV1.3 protein in K+ currents and Ca2+ entry

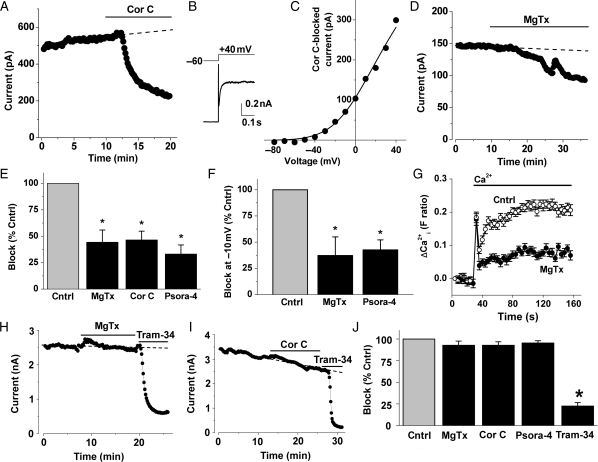

To investigate whether there are functional KV1.3 channels, we used patch-clamp recording to elicit voltage-dependent K+ current in human vein smooth muscle cells. Three chemically distinct KV1.3 channel blockers were tested for effect: margatoxin, correolide compound C, and psora-4.29,31–36 Depolarizing voltage steps evoked voltage-dependent K+ current (Figure 2A and B) that had an activation threshold near −40 mV (Figure 2C), as expected for KV1 channels.27 The current measured at +40 mV was partially inhibited by correolide compound C, margatoxin, or psora-4 (Figure 2A–E). The percentage inhibition caused by each agent was the same, suggesting a common site of action (Figure 2E). At negative (physiological) voltages, currents were small and therefore difficult to measure reliably, but they were nevertheless found to be significantly inhibited at −10 mV (Figure 2F). Further evidence for physiologically relevant KV1.3 came from intracellular Ca2+ measurement experiments where margatoxin significantly suppressed Ca2+ entry, consistent with the existence of a channel that contributes to the enhancement of the electrical attraction for the inward movement of the positively charged Ca2+ ion (Figure 2G). KV1.3 channel blockers showed selectivity because they had no effects on KCa3.1 channel currents (Figure 2H–J). The data suggest that functional KV1.3 channels are present in proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells.

Figure 2.

Effects of KV1.3 blockers on ionic current and intracellular Ca2+. Data from proliferating human saphenous vein smooth muscle cells (A–G) or HEK 293 cells stably expressing KCa3.1 (H–J). All patch-clamp experiments used a holding potential of −60 mV. (A) Example currents (black circles) evoked by stepping to +40 mV for 0.5 s at 0.1 Hz, showing block by 1 μM correolide compound C (Cor C). (B) Typical Cor C-sensitive current during a single voltage step. The initial upward spike is residual capacitance current. (C) Typical current–voltage relationship (I–V) for Cor C-sensitive current generated used 0.5 s incremental 10 mV depolarizing pulses at 0.1 Hz. The smooth curve is a fitted Boltzmann–Ohm's Law function. (D) As for (A) but showing block by 5 nM margatoxin (MgTx). (E) Mean data for the effects of MgTx, Cor C, and Psora-4 (5 nM) on linear leak-subtracted currents at +40 mV (n = 6, 4, and 4, respectively). Current amplitudes after the blocker had had maximum effect were normalized to amplitudes before each blocker was applied. Each blocker had its own control (Cntrl). (F) As for (E) except currents were measured at −10 mV; Cor C data were not obtained because a single step to +40 mV was used in the experiments. (G) Intracellular Ca2+ indicated by the change in fura-2 fluorescence ratio. Cells were pre-treated with thapsigargin (1 μM) to stimulate Ca2+-entry channels and then extracellular Ca2+ (0.2 mM) was added with or without the presence of 5 nM MgTx (n/N = 4/48). (H and I) Typical currents evoked by stepping to +40 mV showing lack of effect of 5 nM margatoxin (H) and 1 μM Cor C (I). Block by the KCa3.1 inhibitor Tram-34 (200 nM) confirmed that the majority of current was carried by KCa3.1. (J) Mean data showing lack of effect of MgTx, Cor C, and 5 nM Psora-4 on KCa3.1 but block by Tram-34 (n = 5, 3, 4, and 14). For each agent, current at the end of the period of application was normalized to its own control current before the application.

3.4. Effects of KV1.3 blockers on migration of mouse and human vascular smooth muscle cells

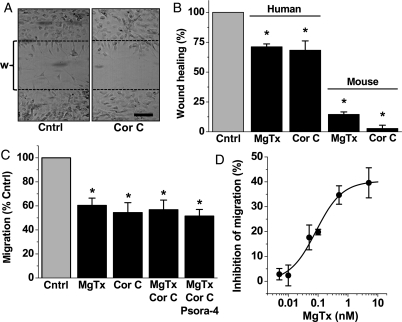

To investigate the relevance to cell function, we first used a model of vascular injury where a linear wound is made in the cell culture, removing cells from a defined region. Cells responded by regrowing into the wound (Figure 3A). At a fixed time point, the number of cells in the wound was counted. Margatoxin or correolide compound C was tested and found to reduce the number of cells in the wound, suggesting decreased capacity for response to injury (Figure 3A and B). Effects on human cells were quantitatively less than for murine cells, suggesting greater dependence on KV1.3 in the mouse (Figure 3A). Experiments were also performed on human cells using a Boyden chamber to explore growth factor-directed cell migration. Again KV1.3 blockers were inhibitory (Figure 3C). The effects of the blockers reached a limiting value and were not additive, consistent with all of the blockers affecting a common mechanism (Figure 3C). Concentration–response data for margatoxin revealed that the IC50 was 85 pM (Figure 3D), which is similar to the potency previously reported against KV1.3 channels.28,32 The data suggest that KV1.3 has a positive role in vascular smooth muscle cell migration and that margatoxin is a high-potency inhibitor of vascular cell migration.

Figure 3.

Actions of KV1.3 blockers on vascular smooth muscle cell migration and response to injury. All data are from human cells except for part of (B). (A) Typical images of cells after creation of a linear wound (w) delineated by the two dashed lines and making a paired comparison of cells without (control) and with 1 μM Cor C. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) As for (A) but mean data for numbers of cells entering the wound in the presence of the indicated blocker normalized to its own control group (n = 3 for each); for 5 nM MgTx, the control was BSA, and for 1 μM Cor C, it was DMSO. (C and D) Mean data from the Boyden chamber cell migration assays comparing effects of MgTx (5 nM unless specified differently in D), Cor C (1 μM), and Psora-4 (5 nM) (n = 4 each). (C) Each blocker group was different from its own control (*) but blocker groups were not significantly different from each other. (D) As for (C) but concentration–response data for MgTx with a fitted Hill equation (IC50 85 pM, slope 0.99).

3.5. Function of KV1.3 in human neointimal hyperplasia

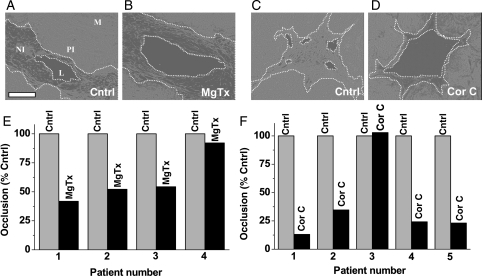

To determine the relevance to human vascular smooth muscle cells in situ, we generated neointimal formations in organ cultures of segments of the saphenous vein, as indicated above. Neointima were compared in paired vein segments from the same patient, one in the presence of the vehicle control and the other in the KV1.3 blocker (Figure 4A–D). Treatment with margatoxin inhibited neointimal growth in all four patient samples, averaging 39.87 ± 11.02% inhibition (P < 0.05) (Figure 4E). Correolide compound C was effective in four out of five patient samples, giving an average inhibition of 60.39 ± 16.19% (P < 0.05) (Figure 4F). The data suggest that KV1.3 channels have a positive role in human neointimal hyperplasia.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of neointimal hyperplasia in human saphenous vein segments. (A–D) Typical images of cross-sections of the vein after organ culture, showing auto-fluorescence (light grey or white). The panel in (A) labels the structure: L, lumen; NI, neointima; PI, pre-existing intima; M, media; the scale bar is 100 μm. In all images, edges of L and NI are indicated by dotted lines. (A and B) Paired experiment on vein from one patient comparing vehicle control (A) and 5 nM MgTx (B). (C and D) Vehicle control compared with 1 μM Cor C. (E and F) Paired individual data for veins from four (E) and five patients (F). The area of NI in the presence of MgTx or Cor C is given as a percentage of its area in the corresponding control.

4. Discussion

The data suggest that KV1.3 is important in proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells. It is exceptional among the KV1 proteins in having preserved and up-regulated expression when the cells switch to their proliferating and migratory phenotype. The proliferating cells exhibit K+ currents and other functional signals that are sensitive to inhibition by a range of established blockers of KV1.3 channels acting in a non-additive manner that is consistent with effects via a common protein, KV1.3. The blockers exhibit high potency against human vascular smooth muscle cell migration, in particular margatoxin which acts with an IC50 of 85 pM. Results with organ cultures of saphenous veins suggest the potential for KV1.3 blockers as suppressors of neointimal hyperplasia and other unwanted vascular smooth muscle cell remodelling events in humans.

Previous studies have established the KV1 family of K+ channels as contributors to the control of physiological vascular tone, showing that they provide negative feedback against depolarizing signals in contractile arterial smooth muscle cells.31,37–39 Although KV1.3 has been detected in contractile cells, functional importance has mostly been attributed to other KV1 subunits (especially KV1.2 and KV1.5). Without excluding contribution of KV1.3 in contractile cells, our observations suggest that KV1.3 has a more distinctive role in vascular adaptation, with little or no involvement of other KV1 subunits. The findings are consistent with a recent report suggesting significance of KV1.3 in cells of the injured mouse femoral artery.40 The event of losing other KV1 subunits may somehow be functionally significant in phenotypic switching,41 but the mechanism by which this would be important is unclear and the channel subunits cannot be targets for pharmacological agents in remodelling because they are not expressed once the cells switch phenotype. All of the KV1 changes should be seen within the context of a wider and quite comprehensive alteration in the ion channel expression pattern as smooth muscle cells switch phenotype.5

The association of KV1.3 with vascular smooth muscle cell adaptation is intriguing because this channel is already linked to the proliferation of lymphocytes, oligodendrocytes, and cancer cells.19,42–44 Therefore, the channel may be a fundamental element of proliferating cells. KCa3.1 is similarly linked to cell proliferation and can co-ordinate with KV1.3.19,28 In lymphocytes, KV1.3 dominates over KCa3.1 during chronic inflammation, such that blockers of KV1.3 are suggested as new therapeutic agents in the treatment of diseases relating to chronic immune responses, including multiple sclerosis.19,28

Because we detected little or no expression of other KV1 genes, and KV1 proteins are not thought to mix with other types of KV protein, our vascular smooth muscle cell data seem to be explained by KV1.3 acting alone (i.e. as a homotetramer). We found that KV1.3 mRNA and protein were expressed alone, there was KV1-like K+ current, and there were effects of three agents at concentrations that are known to block KV1.3 and do not block KCa3.1.29,33,36 However, the voltage-dependent K+ current observed, although similar in some regards to the current generated by over-expressed KV1.3, showed little or no inactivation, which contrasts with many reports of the character of heterologously over-expressed KV1.3 channels. We do not know the reason for the difference but speculate on two possibilities: one possibility is that there is an unknown auxiliary subunit in vascular smooth muscle cells that modifies the inactivation properties of KV1.3. Another possibility is that there is tonic phosphorylation of the channels; Src-dependent phosphorylation strongly decreases the rate of inactivation of KV1.345 and is a common feature of proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells. Unfortunately, despite investigating eight different short-interfering RNA molecules targeted to KV1.3 mRNA and independently validating our methodology via other targets,15 we were unable to modify KV1.3 expression and therefore provide evidence using molecular tools that KV1.3 is involved in the human cells.

The KV1.3 blockers reduced migration of human vascular smooth muscle cells but it was evident that there was not complete inhibition (only ∼40%). This result indicates that there is a component of cell migration that depends on KV1.3 and a component that does not. We speculate that this situation arises because the K+ channels have a modulator function on cell migration, acting by causing hyperpolarization that enhances Ca2+ entry through non-voltage-gated Ca2+ channels that arise from proteins such as TRPC1 and STIM1. According to this hypothesis, the blockade of the KV1.3 K+ channels should suppress Ca2+ entry, which is what we observed (Figure 2G). We previously observed a similar effect with the blockade of another K+ channel, KCa3.1 blockade.22 The mechanism by which the Ca2+ entry facilitates cell migration is unclear and thus requires investigation.

The data suggest the potential for KV1.3 blockers in therapies against unwanted vascular remodelling, especially if the remodelling is accompanied by aggravating chronic inflammatory reactions that involve KV1.3-expressing immune cells. Although vasoconstrictor effects of margatoxin have been observed in some arteries,31 elevated blood pressure has not appeared as a significant concern during in vivo exploration of KV1.3 blockers for the treatment of multiple sclerosis,19,28 perhaps, because KV1.5 is commonly expressed in contractile smooth muscle cells and is resistant to many of the agents that block KV1.3, or because the roles of the KV1 channels can be taken by other voltage-gated K+ channels including KV2, KV7, and KCa1.1.

KV1.3 has often been viewed as an immune cell-specific K+ channel but is now emerging also as a channel of proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells and other proliferating cell types. It reflects one of several similarities in the ion channels of immune cells and vascular smooth muscle cells, including KCa3.1, TRPC, STIM1, and Orai1 channel subunits. The availability of potent KV1.3 channel blockers will facilitate further research in the area and provide foundations for possible new cardiovascular therapies.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Funding

The work was supported by the British Heart Foundation, Medical Research Council, Nuffield Hospital Leeds, and Wellcome Trust. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charge was provided by the Wellcome Trust.

Acknowledgements

We thank G. Kaczorowski (Merck) for correolide compound C and H. Wulff (University of California Davis) for Tram-34. We thank H.G. Knaus (Innsbruck, Austria) for polyclonal anti-KV1.3 antibody and G. Richards (University of Manchester) for HEK 293 cells stably expressing human KCa3.1.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:767–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003. doi:10.1152/physrev.00041.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angelini GD, Jeremy JY. Towards the treatment of saphenous vein bypass graft failure—a perspective of the Bristol Heart Institute. Biorheology. 2002;39:491–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitra AK, Agrawal DK. In stent restenosis: bane of the stent era. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:232–239. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.025742. doi:10.1136/jcp.2005.025742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar B, Dreja K, Shah SS, Cheong A, Xu SZ, Sukumar P, et al. Upregulated TRPC1 channel in vascular injury in vivo and its role in human neointimal hyperplasia. Circ Res. 2006;98:557–563. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000204724.29685.db. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000204724.29685.db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beech DJ. Ion channel switching and activation in smooth-muscle cells of occlusive vascular diseases. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:890–894. doi: 10.1042/BST0350890. doi:10.1042/BST0350890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munaron L, Antoniotti S, Lovisolo D. Intracellular calcium signals and control of cell proliferation: how many mechanisms? J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:161–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00271.x. doi:10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00271.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Cell. 2007;131:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magnier-Gaubil C, Herbert JM, Quarck R, Papp B, Corvazier E, Wuytack F, et al. Smooth muscle cell cycle and proliferation. Relationship between calcium influx and sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase regulation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27788–27794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27788. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.44.27788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vallot O, Combettes L, Jourdon P, Inamo J, Marty I, Claret M, et al. Intracellular Ca2+ handling in vascular smooth muscle cells is affected by proliferation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1225–1235. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.5.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landsberg JW, Yuan JX. Calcium and TRP channels in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. News Physiol Sci. 2004;19:44–50. doi: 10.1152/nips.01457.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gollasch M, Haase H, Ried C, Lindschau C, Morano I, Luft FC, et al. L-type calcium channel expression depends on the differentiated state of vascular smooth muscle cells. FASEB J. 1998;12:593–601. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.7.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quignard JF, Harricane MC, Menard C, Lory P, Nargeot J, Capron L, et al. Transient down-regulation of L-type Ca2+ channel and dystrophin expression after balloon injury in rat aortic cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:177–188. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00210-8. doi:10.1016/S0008-6363(00)00210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golovina VA, Platoshyn O, Bailey CL, Wang J, Limsuwan A, Sweeney M, et al. Upregulated TRP and enhanced capacitative Ca2+ entry in human pulmonary artery myocytes during proliferation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H746–H755. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berra-Romani R, Mazzocco-Spezzia A, Pulina MV, Golovina VA. Ca2+ handling is altered when arterial myocytes progress from a contractile to a proliferative phenotype in culture. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C779–C790. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00173.2008. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00173.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Sukumar P, Milligan CJ, Kumar B, Ma ZY, Munsch CM, et al. Interactions, functions, and independence of plasma membrane STIM1 and TRPC1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2008;103:e97–e104. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182931. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baryshnikov SG, Pulina MV, Zulian A, Linde CI, Golovina VA. Orai1, a critical component of store-operated Ca2+ entry, is functionally associated with Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and plasma membrane Ca2+ pump in proliferating human arterial myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C1103–C1112. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00283.2009. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00283.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bisaillon JM, Motiani RK, Gonzalez-Cobos JC, Potier M, Halligan KE, Alzawahra WF, et al. Essential role for STIM1/Orai1-mediated calcium influx in PDGF-induced smooth muscle migration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C993–C1005. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00325.2009. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00325.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo RW, Wang H, Gao P, Li MQ, Zeng CY, Yu Y, et al. An essential role for stromal interaction molecule 1 in neointima formation following arterial injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:660–668. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn338. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvn338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beeton C, Chandy KG. Potassium channels, memory T cells, and multiple sclerosis. Neuroscientist. 2005;11:550–562. doi: 10.1177/1073858405278016. doi:10.1177/1073858405278016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neylon CB, Lang RJ, Fu Y, Bobik A, Reinhart PH. Molecular cloning and characterization of the intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel in vascular smooth muscle: relationship between KCa channel diversity and smooth muscle cell function. Circ Res. 1999;85:e33–e43. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.9.e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohler R, Wulff H, Eichler I, Kneifel M, Neumann D, Knorr A, et al. Blockade of the intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel as a new therapeutic strategy for restenosis. Circulation. 2003;108:1119–1125. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000086464.04719.DD. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000086464.04719.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheong A, Bingham AJ, Li J, Kumar B, Sukumar P, Munsch C, et al. Downregulated REST transcription factor is a switch enabling critical potassium channel expression and cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2005;20:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.030. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Si H, Grgic I, Heyken WT, Maier T, Hoyer J, Reusch HP, et al. Mitogenic modulation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in proliferating A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:909–917. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706793. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tharp DL, Wamhoff BR, Turk JR, Bowles DK. Upregulation of intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (IKCa1) mediates phenotypic modulation of coronary smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2493–H2503. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01254.2005. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.01254.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tharp DL, Wamhoff BR, Wulff H, Raman G, Cheong A, Bowles DK. Local delivery of the KCa3.1 blocker, TRAM-34, prevents acute angioplasty-induced coronary smooth muscle phenotypic modulation and limits stenosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1084–1089. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.155796. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.155796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.George CK, Wulff H, Beeton C, Pennington M, Gutman GA, Cahalan MD. K+ channels as targets for specific immunomodulation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:280–289. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.03.010. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coetzee WA, Amarillo Y, Chiu J, Chow A, Lau D, McCormack T, et al. Molecular diversity of K+ channels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;868:233–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11293.x. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rangaraju S, Chi V, Pennington MW, Chandy KG. Kv1.3 potassium channels as a therapeutic target in multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:909–924. doi: 10.1517/14728220903018957. doi:10.1517/14728220903018957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fountain SJ, Cheong A, Flemming R, Mair L, Sivaprasadarao A, Beech DJ. Functional up-regulation of KCNA gene family expression in murine mesenteric resistance artery smooth muscle. J Physiol. 2004;556:29–42. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058594. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madi HA, Riches K, Warburton P, O'Regan DJ, Turner NA, Porter KE. Inherent differences in morphology, proliferation, and migration in saphenous vein smooth muscle cells cultured from nondiabetic and Type 2 diabetic patients. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C1307–C1317. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00608.2008. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00608.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheong A, Dedman AM, Xu SZ, Beech DJ. KV α1 channels in murine arterioles: differential cellular expression and regulation of diameter. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H1057–H1065. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.3.H1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Calvo M, Leonard RJ, Novick J, Stevens SP, Schmalhofer W, Kaczorowski GJ, et al. Purification, characterization, and biosynthesis of margatoxin, a component of Centruroides margaritatus venom that selectively inhibits voltage-dependent potassium channels. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18866–18874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koo GC, Blake JT, Shah K, Staruch MJ, Dumont F, Wunderler D, et al. Correolide and derivatives are novel immunosuppressants blocking the lymphocyte Kv1.3 potassium channels. Cell Immunol. 1999;197:99–107. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1569. doi:10.1006/cimm.1999.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wulff H, Calabresi PA, Allie R, Yun S, Pennington M, Beeton C, et al. The voltage-gated Kv1.3 K+ channel in effector memory T cells as new target for MS. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1703–1713. doi: 10.1172/JCI16921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fadool DA, Tucker K, Perkins R, Fasciani G, Thompson RN, Parsons AD, et al. Kv1.3 channel gene-targeted deletion produces ‘Super-Smeller Mice' with altered glomeruli, interacting scaffolding proteins, and biophysics. Neuron. 2004;41:389–404. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00844-4. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00844-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vennekamp J, Wulff H, Beeton C, Calabresi PA, Grissmer S, Hansel W, et al. Kv1.3-blocking 5-phenylalkoxypsoralens: a new class of immunomodulators. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1364–1374. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.6.1364. doi:10.1124/mol.65.6.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C799–C822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Archer SL, Souil E, Dinh-Xuan AT, Schremmer B, Mercier JC, El Yaagoubi A, et al. Molecular identification of the role of voltage-gated K+ channels, Kv1.5 and Kv2.1, in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and control of resting membrane potential in rat pulmonary artery myocytes. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2319–2330. doi: 10.1172/JCI333. doi:10.1172/JCI333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen TT, Luykenaar KD, Walsh EJ, Walsh MP, Cole WC. Key role of Kv1 channels in vasoregulation. Circ Res. 2006;99:53–60. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000229654.45090.57. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000229654.45090.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cidad P, Moreno-Dominguez A, Novensa L, Roque M, Barquin L, Heras M, et al. Characterization of ion channels involved in the proliferative response of femoral artery smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1203–1211. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.205187. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.205187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moudgil R, Michelakis ED, Archer SL. The role of K+ channels in determining pulmonary vascular tone, oxygen sensing, cell proliferation, and apoptosis: implications in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Microcirculation. 2006;13:615–632. doi: 10.1080/10739680600930222. doi:10.1080/10739680600930222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin CS, Boltz RC, Blake JT, Nguyen M, Talento A, Fischer PA, et al. Voltage-gated potassium channels regulate calcium-dependent pathways involved in human T lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med. 1993;177:637–645. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.3.637. doi:10.1084/jem.177.3.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kotecha SA, Schlichter LC. A Kv1.5 to Kv1.3 switch in endogenous hippocampal microglia and a role in proliferation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10680–10693. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-24-10680.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Felipe A, Vicente R, Villalonga N, Roura-Ferrer M, Martinez-Marmol R, Sole L, et al. Potassium channels: new targets in cancer therapy. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30:375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.06.002. doi:10.1016/j.cdp.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cook KK, Fadool DA. Two adaptor proteins differentially modulate the phosphorylation and biophysics of Kv1.3 ion channel by SRC kinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13268–13280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108898200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M108898200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.