Abstract

Research on economic inequalities in health has been largely polarized between psychosocial and neomaterial approaches. Examination of symbolic capital—the material display of social status and how it is structurally constrained—is an underutilized way of exploring economic disparities in health and may help to resolve the existing theoretical polarization. In contemporary society, what people do with money and how they consume and display symbols of wealth may be as important as income itself. After tracing the historical rise of consumption in capitalist society and its interrelationship with economic inequality, I discuss evidence for the role of symbolic capital in health inequalities and suggest directions for future research.

In the United States and other developed nations, economic disparities in health are dramatic. Individuals lower on the economic scale have poorer average health than do those who are better off. This phenomenon persists across multiple measures of economic position, primarily income, education, and occupation,1,2 and across multiple indicators of health, including all-cause mortality, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, cancers, and infant mortality.2–4 Unlike in developing nations, where thresholds of absolute poverty are strong predictors of mortality, health disparities in the United States and Europe exist across the entire economic spectrum.3 This gradient effect, coupled with observations that overall levels of societal inequality are associated with health,5 suggests that relative economic position is a critical variable in health inequalities.

The pathways by which relative economic position can influence health have been the focus of considerable research attention across biomedical and social science disciplines. In general, the main approaches characterizing this literature are (1) a neomaterial perspective, focusing on the health effects of lower objective economic status, mediated primarily through pathways of limited access to institutional, physical, and social health benefits, and (2) a psychosocial approach, focusing on the psychological consequences of lower subjective economic position, such as depression and chronic stress, and their effects on physiological processes and health behaviors. One pathway through which psychosocial mechanisms may operate is feelings of relative deprivation,6 described as a process of social comparison whereby individuals feel deprived in relative evaluation with another reference group in society. It is hypothesized that these feelings of deprivation can result in chronic stress for individuals, with significant consequences for biology and disease.7

Relative deprivation is a difficult construct to operationalize, however, particularly because identifying meaningful reference groups to which individuals make social comparisons is challenging. Strategies to address this problem include comparing individuals or households within similar occupational classes, age categories, or geographical areas.8–10 In each of these strategies, the indicator on which analyses are based, and along which people are assumed to make subjective comparisons leading to feelings of deprivation, is income. It is often the case, however, that others' incomes are not objectively known, meaning that it may not be the best variable for evaluating psychologically relevant social comparisons.

In contemporary society it may be what people do with money and how they consume and display symbols of wealth, rather than money per se, that serve as the bases for establishing social identity and position. In a consumer-oriented society, material goods provide the basis for social evaluation and are thus an important medium through which inequalities are experienced. Focusing on symbolic capital, the material display of social status and how it is structurally constrained, specifically as it relates to consumption and commoditization, may be one way to better understand how relative economic position influences health. Here I trace the historical rise of consumption in capitalist society and its interrelationship with economic inequality, discuss evidence for the role of symbolic capital in health inequalities, and propose directions for future research.

POLITICAL ECONOMY OF CONSUMPTION

Understanding the significance of consumption in modern society and its relationship to social inequality requires a political–economic analysis of the historical development of consumer society. Although literature on consumerism during the past 30 years has focused more on postmodern concepts of individual style and expression,11,12 aspects of consumption are fundamental to the history of political–economic thought. Marx, for instance, considered commodities to be the logical starting point for his analysis of modern capitalism.13 For Marx, commodities were central to understanding the social condition under capitalism, particularly to the extent that their production and exchange concealed real social relations and participated in the alienation of labor: “There is a definite social relation between men that assumes, in their eyes, the fantastic form of a relation between things.”13(p165) As contemporary Marxist scholar Harvey points out, however, “He is not saying that this disguise, which he calls fetishism … is a mere illusion.”14(p41) Although Marx's primary interest was in the underlying relations of labor and production concealed within commodities, several political economists who were followers of Marx focused on the social and economic implications of the consumption process itself.

Lefebvre, writing in the mid-20th century, suggested that an analysis of contemporary society was needed that takes Marx's concept of alienation seriously.15 In Critique of Everyday Life, Lefebvre argued that mass consumption, commoditization, and leisure, which have come to define modern society, represented new forms of capitalist alienation in everyday life. Adorno and Horkheimer echoed this emphasis on mass, and especially mass-marketed, consumption from a highly critical perspective.16 In The Culture Industry, they argued that in the same way that labor is alienated under the capitalist mode of production, so too is consumer society created and dictated by the power of capital. To ensure the continuation of capital accumulation, a mass consumer society is needed in which individualism and creativity are replaced with homogenization and mass deception. As they put it, “Under monopoly all mass culture is identical …”16(p3)

Galbraith made this critique more specific to the corporate origins of consumer society by targeting the role of advertising in capitalism.17 Galbraith argued that because consumption must increase along with production in capitalist society, marketing plays the central role of creating a consumer society that can keep pace with production. He called this phenomenon the dependence effect: “As a society becomes increasingly affluent, wants are increasingly created by the process by which they are satisfied.”17(p129) Because both the production and consumption ends are under the same corporate control, the whole of society functions in the best interest of capital.

Like Marx, Galbraith, Adorno, and Horkheimer all offered critical analyses of the general role of consumption and consumer goods in society. For all of these writers, capitalism creates conditions detrimental to aspects of basic human nature, such as creativity and social relationships. Under capitalism, social relations are mediated through the production and consumption of material things. This generically negative consequence of a consumer society holds relevance for public health, because it evokes concepts such as social capital, social support, and negative mental states. But consumption also plays a more specific role in the production and maintenance of social inequalities in society, and this also has significant implications for health.

Consumption, Status, and Cultural Norms

The first, and possibly most famous, analysis of mass consumption and inequality appears in Veblen's Theory of the Leisure Class.18 Introducing the idea of conspicuous consumption, Veblen argued that, as wealth accumulates and class differences grow larger in society, material consumption plays an important role in symbolically representing social distinctions. In Veblen's theory, the wealthy upper classes set the ultimate standard for status distinction through excessive displays of leisure time and material goods. Lower economic classes in society then attempt to approximate these symbolic markers of status, but in an imperfect and descending manner, with each class emulating the next-highest class in the social order.18 Thus, Veblen argued, across the economic spectrum, people strive for the standard of decency of those above them in the economic hierarchy, “an ideal of consumption that lies just beyond our reach.”18(p103) Veblen also reasoned that the importance of material consumption is heightened in modern urban contexts, where social comparisons are more fleeting and impersonal than in closer-knit, less industrial communities. Thus, rather than kinship and other traditional markers of social position, he proposed that in modern society interactions are guided more by symbolically displayed social status.

Bourdieu carried the analysis of consumption and inequality beyond the observation that the purchase of material goods is patterned by economic class. Distinction, Bourdieu's study of French consumer culture showed that, even within economic groups, consumer tastes differ as a function of cultural capital, or an individual's access to formal education and more upper-class social norms.19 For Bourdieu, the dialectical relationship between cultural capital and taste allows for the reproduction and maintenance of social hierarchies, because economic distinctions are woven into the cultural fabric. Bourdieu thus introduced the idea that economic, material, and symbolic forms of capital intersect with each other in complex ways in modern society, and that culture, in the anthropological sense, is critical to understanding these relationships.19 It is this observation that is particularly relevant to health, because it suggests that consumption is not just a reflection of economic position in society but also a means through which culturally embedded norms of social identity are expressed, distinguished, and experienced.

Consumption and Late Capitalism

In the current political–economic context of the postmodern era, or what Jameson refers to as the cultural logic of late capitalism,20 the ways that consumption is socially and economically patterned have become even more complex. Galbraith's observation that capital demands increasing consumption as production levels rise is now even more salient. With the technological advances, fast-paced distribution of products, and relaxed global labor market policies that characterize contemporary flexible accumulation,21 new ways of moving mass consumption have developed. In particular, corporate marketing strategies have promoted fragmented consumer pools that are targeted through specific age-, gender-, and race-based niche marketing.21,22 With the creation of specific purchasing groups and the targeting of products to those groups, everyone is encouraged to participate in consumer society to an equal degree.

It is also through this fragmentation of markets that consumption helps to reinforce the very social inequalities that are reflected in its economic patterning. By making consumption appear to reflect choices of individual or group identities, the real imbalances of power and resources that are embodied in consumer commodities are concealed.21,23,24 In the words of Harvey, the illusion that luxury status and symbolic capital are democratically available is “deployed deliberately to conceal, through the realms of culture and taste, the real basis of economic distinctions.”21(p78) Stated another way, “The economic context that makes consumption the engine of the economy also makes many people poor.”25(p3)

The ratcheting up of consumption is only made worse in the current context of dramatically increased economic disparity. Recent data show that income inequality, after leveling off during the middle part of the 20th century, has now exceeded pre-Depression levels.26 The income share of the top decile of US earners in 2007 was 49.7%. Real incomes for the top 1% of households rose 176% between 1979 and 2005 but only 6% for the bottom quintile.27 These disparities not only reflect the role of consumption in concentrating wealth at the top of the economic ladder but also signal a problematic environment for Veblen-esque emulative consumerism.

In The Overspent American, Schor suggests that the combination of more concentrated wealth and widespread media images of that wealth has changed the social norm of symbolic capital against which we compare ourselves: “Today a person is more likely to be making comparisons with, or choosing as a ‘reference group,’ people whose incomes are three, four, or five times his or her own. The result is that millions of us have become participants in a national culture of upscale spending.”28(p4) In this context, Veblen's notion of a standard of decency as a reference point becomes distorted; what is perceived, and widely portrayed in television shows and movies, as common and decent is in reality more exclusive and elusive.

The contemporary climate of high economic inequality thus promotes a pattern of consumption that both reflects and maintains those inequalities. By concealing real inequity in symbolic representations of status, and embedding those symbols in cultural norms, capitalist logic is able to make wealth seem democratic: although we can't all be rich, anyone can have the status of the upper class by displaying the right symbols. Of course, this logic is manipulative: without wealth, attaining its symbols is challenging, and, even with the right symbols, the true benefits of upper class status are still elusive. Furthermore, the consumption of status symbols not only feeds into the increasing concentration of wealth at the top of the economic ladder but also erodes the exclusivity of those symbols, leading to a change in the norms against which consumer status is measured. A self-perpetuating dialectical relationship exists, therefore, between economic inequality and consumption in contemporary capitalist society, which has significant implications for health.

CONSUMPTION, STATUS, AND HEALTH

This analysis of consumption within historical and contemporary political–economic contexts makes clear how significant the things we buy, and their uses as symbolic capital, are in society. Because consumption plays a critical role in both the maintenance and the expression of social and economic inequalities, it follows that it may be an important parameter to consider with regard to social disparities in health. Although relatively little work has been done on this topic, the research that exists is compelling.

A line of research in biocultural anthropology has explored the role of consumption in the relationship between economic inequality and health in the United States. Dressler et al.29 and I30 have explored how cultural norms of material status are associated with health. In both cases the cultural consensus31 and cultural consonance32 methods were used to measure relative social positions. The consensus approach, in brief, defines culture as beliefs and ideas that are shared rather than idiosyncratic. Cultural information can thus be identified as that which is most shared among the members of a group, community, or society. Consensus analysis statistically assesses sharedness (and therefore culturalness) of information by testing interrespondent agreement among a sample of informants. This analysis is accomplished by, in essence, factor-analyzing individuals as if they were variables to see the extent to which people hang together as a coherent cultural group. Cultural consonance assesses the extent to which individuals adhere in practice to the cultural norms of their group.

Two examples illustrate how relative social position is assessed as the degree to which individuals conform to measured cultural norms of material consumer status. Dressler et al. measured consensus around cultural norms of material lifestyle.29 They asked a sample of rural African American informants to rate how important certain standard material items were for defining being a success in life. Items included basic material goods, such as owning a home, television, microwave oven, and stereo. The researchers found that individuals who owned more of these items, or were more consonant with this cultural model of material lifestyle, were less likely to have hypertension and to smoke. In this analysis, cultural consonance was a stronger negative predictor of these cardiovascular risk factors than were conventional socioeconomic measures of income, education, and occupation.

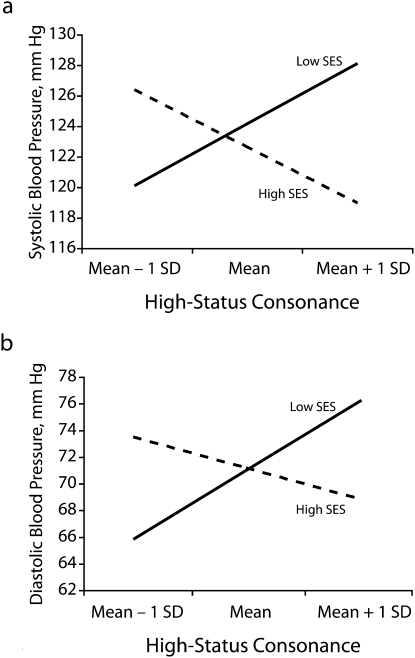

I used the consensus method to establish cultural models of social status for urban African American adolescents. Informants rated items by their importance as indicators of social status among their peers. The items that participants rated were generated from in-depth ethnographic interviews with adolescents in the community. The cultural model of social status for these adolescents included a dimension of particularly high-status and high-priced consumer goods, including Juicy Couture clothing, RAZR cell phones, and expensive cars. This cultural model of high status was found to predict adolescent systolic and diastolic blood pressure in interaction with parental socioeconomic status (SES): being consonant with this model was associated with lower blood pressure if parents' SES was high, but with higher blood pressure if parents' SES was low (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Relationship of cultural consonance in status, by parent SES, with (a) systolic blood pressure and (b) diastolic blood pressure: Maywood, IL, 2006.

Note. SES = socioeconomic status.

The findings of this study suggest that having high symbolic capital may only benefit health if economic resources are present to support it and that trying to convey high status without adequate money capital may be detrimental. On a more general level, these findings could also point to the long-term psychological burden of an unequal, consumer-oriented society, because youths with low SES may turn to consumption as a way of managing the chronic stress of relative poverty. This interpretation highlights the irony of a political–economic system that promotes consumption as an equalizing or democratic process to disguise underlying inequalities in society.

In other work, Pikhart et al. found that ownership of household items in Hungary and Poland was associated with self-rated health.33 Specifically, owning items classified by the researchers as socially oriented and luxurious, as opposed to satisfying basic needs, was associated with lower odds of reporting poor health when other socioeconomic variables were controlled. In another study from Europe, Laaksonen et al. found that low housing wealth was associated with mortality in Finland.34 They measured housing wealth not just as home ownership but also with more symbolic markers, such as home size, measured as both floor area (m2) and number of rooms. Although conventional socioeconomic indicators accounted for some of this association, all of the measures of housing wealth remained significant predictors of mortality in adjusted analyses.

CONCLUSIONS

Evidence from these studies suggests that symbolic markers of wealth or status, especially as measured by consumer goods, are important and underdeveloped dimensions of health inequality. In all of the examples described, consumption markers showed associations with health that were either different or independent from conventional socioeconomic markers. This suggests that symbolic capital is not simply a reflection of economic standing but rather another dimension of social position with relevance for health.

Several mechanisms could play a role in the influence of symbolic capital on health. One likely pathway is stress. When both economic disparities and pressure to consume symbolic markers of status are high, potential incongruities between symbolized and actual wealth are large. In this situation, stress may result from feelings of relative deprivation, because people compare themselves to largely unattainable status norms and feel deprived when they are not able to sufficiently meet them. In addition, stress could result from the financial strain of trying to meet status norms without ample economic resources.

Symbolic capital may also represent direct material pathways to health. Here it is important to remember that something that has symbolic meaning may also have material consequences. Designer clothing, for example, can be used to appear wealthy in everyday social interactions, but may also convey professionalism in a job interview and thus contribute to one's employment status. Granite countertops can both display wealth and increase home value. Maintaining yearly memberships to exclusive clubs is a marker of prestige but also grants access to social networks with real material benefits. All of these symbols can only be acquired through objective money capital. Symbolic capital thus has a dialectical relationship with objective capital and, as such, provides an index of socioeconomic status that is perhaps more meaningful and encompassing than conventional indicators.

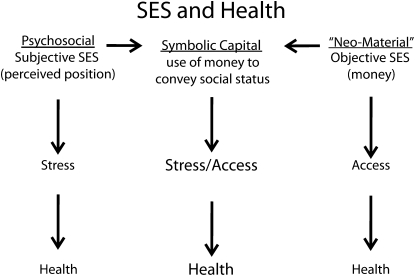

In light of these possibilities, symbolic capital may potentially provide a unifying vehicle for different interpretations of health inequality. The literature to date has been largely polarized between psychosocial and neomaterial explanations of how social inequalities influence health. Although scholars have pointed out that the differences between these explanations are “overdrawn,”35(p848) and that the perspectives are “not mutually exclusive,”36(p649),37 psychosocial and neomaterial interpretations are often still portrayed as competing theories.37

By simultaneously capturing both subjective and objective dimensions of economic status, symbolic capital may offer not just a theoretical but also an analytical bridge between psychosocial and neomaterial perspectives (Figure 2). By focusing on individuals' economic engagement with cultural norms of status, and on the ways capitalist structures simultaneously constrain and promote that engagement, symbolic capital helps to overcome the criticism of “decontextualized psychosocial approaches” that assume subjective perceptions exist “in a vacuum.”37(p1202) At the same time, the concept of symbolic capital avoids the reification of money by recognizing that money's significance for health lies in its use, not in its abstract existence.

FIGURE 2.

Theories of social inequality and health with symbolic capital as a bridging concept.

Note. SES = socioeconomic status.

Kaplan and Lynch have suggested that an epidemiology of everyday life is needed in health disparities research, which describes “the links between neomaterial conditions and the forces that generate them, psychosocial states, the social milieu, and health outcomes.”38,39(p352) Symbolic capital contributes to this epidemiology of everyday life, because it embodies the confluence of political–economic conditions and potentially stressful cultural norms and expectations. Most important, symbolic capital offers a vehicle for examining how money is used and experienced in everyday social life—something that is critical for understanding how socioeconomic inequalities influence health. Future research should explore in greater depth how consumer symbols are associated with psychological and biological markers of stress and other health outcomes, how these symbols and their effects vary across social contexts, and what pathways mediate these relationships.

Acknowledgments

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health and Society Scholars Program provided financial support during preparation of this article.

Special thanks to Ichiro Kawachi for his helpful feedback on drafts of this article.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was required because no human participants were involved.

References

- 1.Marmot M. Economic and social determinants of disease. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(10):988–989 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler NE, Rekhopf DH. U.S. disparities in health: descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:235–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, et al. Socioeconomic status and health. The challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol. 1994;49(1):15–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adler NE, Ostrove JM. Socioeconomic status and health: what we know and what we don't. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. The Health of Nations: Why Inequality Is Harmful to Your Health. New York, NY: New Press; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Runciman W. Relative Deprivation and Social Justice: A Study of Attitudes to Social Inequality in Twentieth-Century England. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1966 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. The problems of relative deprivation: why some societies do better than others. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(9):1965–1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aberg Yngwe M, Fritzell J, Lundberg O, Diderichsen F, Burstrom B. Exploring relative deprivation: is social comparison a mechanism in the relation between income and health? Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(8):1463–1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gravelle H, Sutton M. Income, relative income, and self-reported health in Britain 1979–2000. Health Econ. 2008;18(2):125–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondo N, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Takeda Y, Yamagata Z. Do social comparisons explain the association between income inequality and health? Relative deprivation and perceived health among male and female Japanese individuals. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(6):982–987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holt DB, Schor J. Introduction: do Americans consume too much? : Schor J, Holt DB, The Consumer Society Reader. New York, NY: New Press; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schor JB. In defense of consumer critique: revisiting the consumption debates of the twentieth century. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2007;611(1):16–30 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marx K. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Vol 1 Fowkes B, trans 1867 New York, NY: Penguin Books; 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvey D. A Companion to Marx's Capital. London, UK: Verso; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 15.LeFebvre H. Critique of Everyday Life. Vol I London, UK: Verso; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adorno T, Horkheimer M. The culture industry: enlightenment as mass deception. : Schor J, Holt D, The Consumer Society Reader. New York, NY: New Press; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galbraith J. The Affluent Society. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1958 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veblen T. The Theory of the Leisure Class. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 1899 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bourdieu P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jameson F. Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harvey D. The Condition of Postmodernity. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 22.di Leonardo M. Exotics at Home: Anthropologies, Others, American Modernity. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrier JG, Heyman JM. Consumption and political economy. J R Anthropol Inst. 1997;3(2):355–373 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chin E. Purchasing Power: Black Kids and American Consumer Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams B. SANA Race and Justice Plenary I: no justice, no peace? N Am Dialogue. 2008;11(2):1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saez E. Striking it richer: the evolution of top incomes in the United States (update with 2007 estimates). Pathways Magazine. Winter 2008:6–7 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piketty T, Saez E. Income inequality in the United States, 1913–1998. Q J Econ. 2003;118(1):1–39 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schor J. The Overspent American: Why We Want What We Don't Need. New York, NY: Harper Perennial; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dressler WW, Bindon JR, Neggers YH. Culture, socioeconomic status, and coronary heart disease risk factors in an African American community. J Behav Med. 1998;21(6):527–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sweet E. “If your shoes are raggedy you get talked about”: symbolic and material dimensions of adolescent social status and health. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(12):2029–2035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romney AK, Weller SC, Batchelder WH. Culture as consensus: a theory of culture and informant accuracy. Am Anthropol. 1986;88(2):313–338 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dressler WW. Culture and blood pressure: using consensus analysis to create a measurement. Cult Anthropol Methods. 1996;8(3):6–8 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pikhart H, Bobak M, Rose R, Marmot M. Household item ownership and self-rated health: material and psychosocial explanations. BMC Public Health. 2003;3:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laaksonen M, Tarkiainen L, Martikainen P. Housing wealth and mortality: a register linkage study of the Finnish population. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(5):754–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adler N. When one's main effect is another's error: material vs. psychosocial explanations of health disparities. A commentary on Macleod et al., “Is subjective social status a more important determinant of health than objective social status? Evidence from a prospective observational study of Scottish men” (61[9], 2005, 1916–1929). Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(4):846–850, discussion 851–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Almeida-Filho N. A glossary for health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(9):647–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lynch JW, Smith GD, Kaplan GA, House JS. Income inequality and mortality: importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ. 2000;320(7243):1200–1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaplan GA, Lynch JW. Whither studies on the socioeconomic foundations of population health? Am J Public Health. 1997;87(9):1409–1411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaplan GA, Lynch JW. Is economic policy health policy? Am J Public Health. 2001;91(3):351–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]