Abstract

Around 30–40 years after the first isolation of the five complexes of oxidative phosphorylation from mammalian mitochondria, we present data that fundamentally change the paradigm of how the yeast and mammalian system of oxidative phosphorylation is organized. The complexes are not randomly distributed within the inner mitochondrial membrane, but assemble into supramolecular structures. We show that all cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is bound to cytochrome c reductase (complex III), which exists in three forms: the free dimer, and two supercomplexes comprising an additional one or two complex IV monomers. The distribution between these forms varies with growth conditions. In mammalian mitochondria, almost all complex I is assembled into supercomplexes comprising complexes I and III and up to four copies of complex IV, which guided us to present a model for a network of respiratory chain complexes: a ‘respirasome’. A fraction of total bovine ATP synthase (complex V) was isolated in dimeric form, suggesting that a dimeric state is not limited to S.cerevisiae, but also exists in mammalian mitochondria.

Keywords: blue-native PAGE/complex I/complex III/complex IV/F1F0-ATP synthase

Introduction

The first protocols for the isolation of the five complexes of oxidative phosphorylation from mammalian mitochondria were published ∼30–40 years ago (see Hatefi, 1985). These complexes are functionally active when isolated as individual complexes. Although the vast majority of studies on the structural organization of the respiratory chain favour a model that allows free complexes to diffuse laterally and independently of one another, there have been several indications for permanent interactions of complexes, e.g. kinetic analyses (Rich, 1984; Boumans et al., 1998), stoichiometric association of complexes I and III after detergent removal from a mixture of the isolated complexes (Fowler and Richardson, 1963; Ragan and Heron, 1978), isolation of NADH cytochrome c reductase (complex I+III; Hatefi and Rieske, 1967) and succinate cytochrome c reductase (complex II+III; Tisdale, 1967) from bovine mitochondria, and interaction of complexes II and III in yeast (Bruel et al., 1996).

The organization of the respiratory chains in certain bacteria seemed to be different, since stable supercomplexes of complexes III and IV were isolated, e.g. from Paracoccus denitrificans (Berry and Trumpower, 1985), the thermophilic bacterium PS3 (Sone et al., 1987) and the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolubus sp. strain 7 (Iwasaki et al., 1995a,b).

In this work we attempted to isolate such supramolecular structures of the system of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) by a mild one-step protocol for the isolation of membrane protein complexes, namely blue-native PAGE (BN-PAGE). We have observed previously that the dimeric state of Saccharomyces cerevisiae ATP synthase (complex V) and the binding of three dimer-specific proteins were retained when low Triton X-100/protein ratios were used for solubilization (Arnold et al., 1998). Digitonin also retained the dimeric state of complex V, but the digitonin/protein ratio was not critical. Therefore, mostly digitonin was used in this work to search for additional supramolecular structures of membrane protein complexes within the OXPHOS system.

Results

Quantitative association of complexes III and IV in yeast

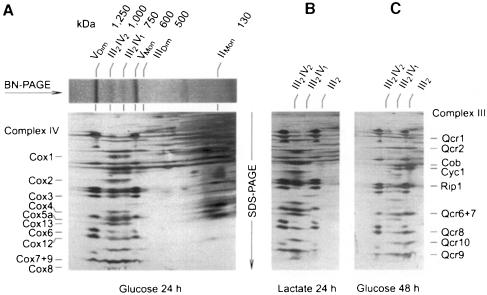

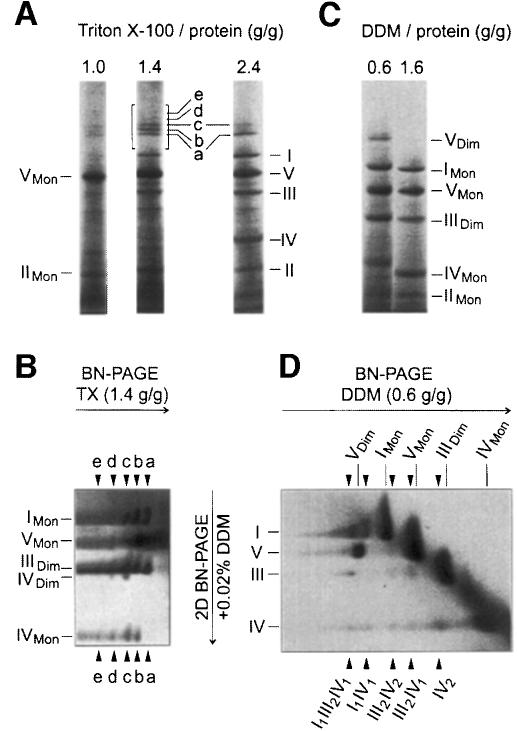

BN-PAGE (Schägger and von Jagow, 1994) of digitonin-solubilized mitochondria from S.cerevisiae grown on glucose for 24 h revealed two major bands of complex V monomer (∼600 kDa) and dimer (∼1250 kDa), and two additional bands with apparent masses of ∼750 and 1000 kDa (Figure 1A). These complexes contained the subunits of complexes III and IV, as revealed by SDS–PAGE in a second dimension followed by N-terminal sequencing. Densitometric quantification of the protein subunits in two-dimensional gels and the apparent masses in BN-PAGE indicated that the smaller supercomplex (III2IV1) consisted of a complex III dimer (500 kDa) and a complex IV monomer (200 kDa). The larger supercomplex (III2IV2) represented a complex III dimer associated with two complex IV monomers.

Fig. 1. Saccharomyces cerevisiae complex IV is quantitatively associated with complex III. The amounts of complex III in free dimeric form (III2) or associated with one (III2IV1) or two complex IV monomers (III2IV2) vary with growth conditions. (A) BN-PAGE of mitochondria from strain W303-1A grown on glucose for 24 h, and two-dimensional resolution by SDS–PAGE. The subunits of complexes III and IV were assigned after N-terminal protein sequencing. (B) Growth on lactate increases the amount of III2IV2 complex, and decreases the fraction of free complex III. (C) Prolonged growth on glucose reduces the amounts of the III2IV2 complex, and increases the fraction of free complex III. VDim and VMon are dimeric and monomeric ATP synthase (complex V), respectively.

Complex IV was not detectable in the region between complex II (130 kDa) and complex III dimer (500 kDa). This means that nearly all complex IV was associated with complex III to form supercomplexes.

We investigated whether the supercomplexes are stable in digitonin. Increasing the digitonin/protein ratio for solubilization of mitochondria from 1.5 to 8.0 (g/g) did not affect the amount of the III2IV1 complex, but the fraction of the III2IV2 complex decreased by a few percent with a corresponding increase of free complex III dimer (not shown). The minimal effect of high digitonin seemed to indicate a stable rather than a dynamic association of proteins.

However, the distribution between III2IV2, III2IV1 and free complex III was dependent on the growth conditions. After growth on glucose for up to 24 h (Figure 1A), we typically measured ∼20% of complex III in the free dimeric form, and ∼40% each assembled into the III2IV1 and III2IV2 complexes. After growth for 48 h, the III2IV2 complex decreased to <20% with a concomitant increase of free complex III dimer to ∼50% (Figure 1C). In contrast, growth on lactate, which induced the biosynthesis of complex IV, also induced the formation of the III2IV2 complex. Usually, <10% of complex III was found in free dimeric form, <30% was assembled into the III2IV1 complex and 60–90% was assembled into the III2IV2 complex (Figure 1B). This growth-dependent variation allows for a variable stoichiometry of complex IV relative to other OXPHOS complexes without resulting in any free form of complex IV.

The subunit composition of the two supercomplexes was analysed by protein sequencing. No differences between the two supercomplexes could be detected.

Evidence for functional significance of complex III–IV association

We tested whether a role of the supercomplexes is to stabilize complex IV against proteolysis. Mitochondria from a complex III deletion mutant (Δqcr8), which cannot form assembled complex III, were analysed by BN-PAGE/SDS–PAGE for the presence of assembled complex IV. The amount and subunit composition of complex IV were normal compared with wild-type yeast (not shown). Similarly, a normal amount and subunit composition of complex III were observed using a Δcox4 deletion mutant that cannot form assembled complex IV (not shown). This indicated that complexes III and IV are not dependent on each other for stability, and the formation of supercomplexes is not required for stabilization of complex IV. Similar results were obtained by others (C.M.Cruciat, S.Brunner, W.Neupert and R.A.Stuart, in preparation).

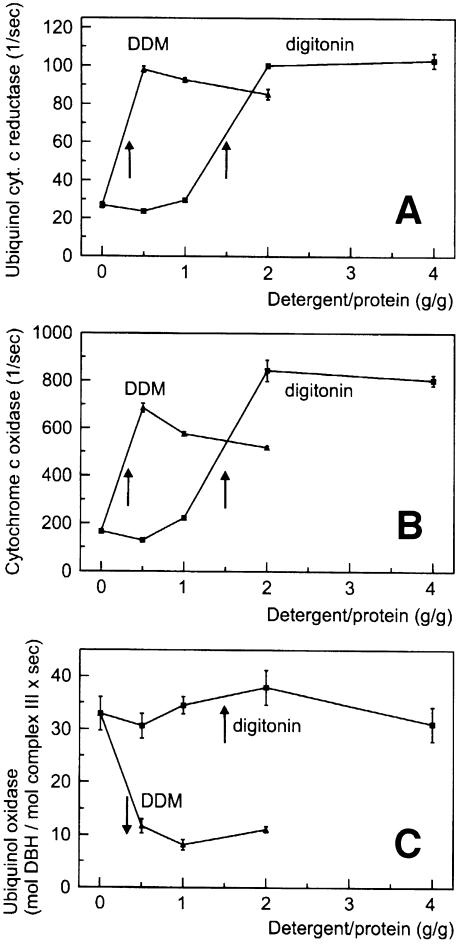

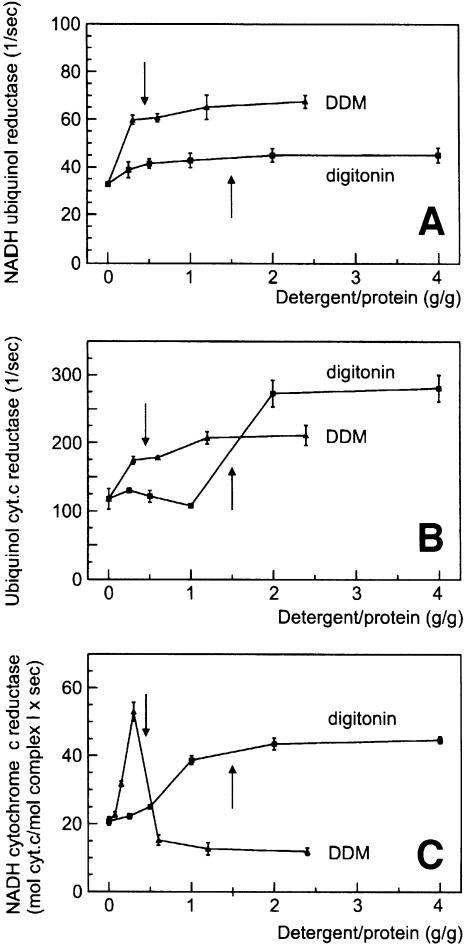

We tried to explore the functional significance of stable complex III–IV interactions by functional analyses using isolated mitochondria (Figure 2). Mitochondrial membranes from W303-1A wild type (grown on lactate for maximal amounts of III2IV2 supercomplexes; see Figure 1B) were solubilized at near physiological ionic strength (150 mM NaCl, 75 mM imidazole–HCl pH 7). The electron transport rates of complex III (ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase; Figure 2A) and complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase; Figure 2B) in the absence of detergent indicated that substrate cytochrome c had limited access to the inner membrane of the frozen and thawed mitochondria used. Using detergent/protein ratios sufficient for quantitative solubilization of the complexes eliminated accessibility barriers, and maximal rates were obtained after complete solubilization by dodecylmaltoside (DDM) and digitonin. This increase in rates is in sharp contrast to the significant decrease in the overall quinol oxidase rate (complexes III+IV; Figure 2C) after addition of DDM. In these experiments, 5 µM yeast cytochrome c, which is slightly above its KM for digitonin and DDM-solubilized complex III (3.5 ± 0.6 µM yeast cytochrome c), was added to the test buffer, but dissociation and dilution of cytochrome c could still be the cause of this decay. However, this explanation can be largely excluded, since no decrease in the quinol oxidase rate was observed after complete solubilization by digitonin. Even at 4 g/g digitonin, the quinol oxidase rate still corresponded to ∼60% of the maximal ubiquinol cytochrome c reduction rate [∼30 mol decylbenzoquinol (DBH) oxidized/mol complex III/s (Figure 2C) compared with 100 mol cytochrome c reduced/mol complex III/s (Figure 2A)]. Therefore, we conclude that the decrease in activity observed with DDM is due to a dissociation of the complex III–IV supercomplexes, which were retained after solubilization by digitonin. In fact, the decrease in quinol oxidase activity was observed in the same range as dissociation of supercomplexes III–IV was detected by BN-PAGE (not shown).

Fig. 2. Functional association of complexes III and IV in digitonin-solubilized yeast mitochondria. Detergent dependence (A) of ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase (mol cytochrome c reduced/mol complex III/s), (B) of cytochrome c oxidase (mol cytochrome c oxidized/mol complex IV/s) and (C) of ubiquinol oxidase (complexes III+IV; mol DBH oxidized/mol complex III/s) after addition of 5 µM yeast cytochrome c. Arrows indicate the solubilization range. A decrease in ubiquinol oxidase rates after solubilization by DDM indicates a separation of complexes III and IV. No decay of rates and no dissociation of complex III–IV occur after solubilization by digitonin (cf. text).

Supercomplexes of mammalian mitochondria

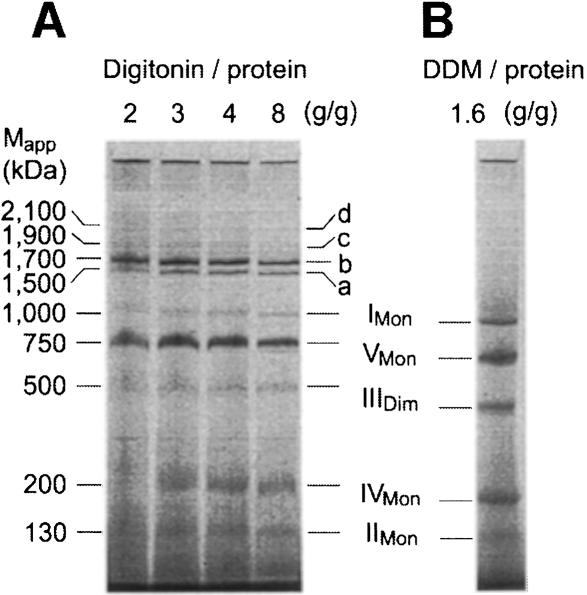

We investigated whether similar interactions of complexes also exist in mammalian mitochondria. Bovine heart mitochondria were solubilized using varying digitonin/protein ratios and resolved by BN-PAGE (Figure 3A). A digitonin/protein ratio of 4 g/g was used in the following unless stated otherwise. Monomeric complex I and dimeric complex III were significantly reduced compared with quantitative solubilization by 1.6 g DDM/g protein (Figure 3B). However, the missing amounts were found to be assembled essentially into two major complexes, a and b, and two minor complexes, c and d, in the molecular mass range 1500–2100 kDa. Two-dimensional resolution by SDS–PAGE revealed the presence of subunits of complexes I, III and IV (not shown).

Fig. 3. Complex I from bovine heart mitochondria is associated with complexes III and IV. (A) BN-PAGE of bovine heart mitochondria after solubilization by digitonin. Most complex I and complex III was found assembled into two major supercomplexes a and b, and two minor supercomplexes c and d. The 200 kDa mass differences indicate the presence of varying copy numbers of monomeric complex IV. (B) Solubilization by DDM was used as a reference for quantitative solubilization of all OXPHOS complexes.

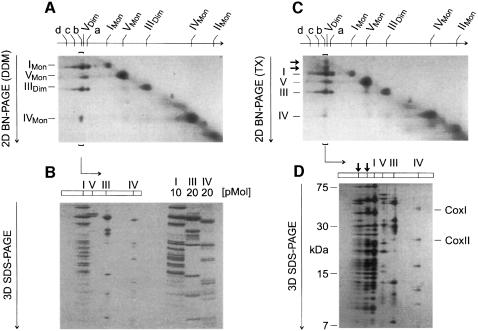

For better analysis of the components of the supercomplexes, a two-dimensional electrophoretic technique was developed, which used BN-PAGE in the first dimension and BN-PAGE plus detergent added to the cathode buffer in the second native dimension (2D BN-PAGE). Complexes from the first BN-PAGE that retained their masses after 2D BN-PAGE were found on a diagonal (Figure 4A). However, the supercomplexes were dissociated into the individual complexes and detected below the diagonal. Using a DDM addition for 2D BN-PAGE (Figure 4A), band a from the first BN-PAGE dissociated into complexes I and III. Bands b–d dissociated into complexes I, III and IV. Silver staining was required to detect complex IV that had dissociated from bands c and d (not shown). The stoichiometries within the supercomplexes were determined by densitometric quantification of Coomassie-stained SDS gels of strips from 2D BN gels (3D SDS–PAGE; Figure 4B). Calibration of the densitometric scans was performed with defined amounts of chromatographically purified complexes I, III and IV that were applied to the same gel. Bands a–d from Figure 4A were thus characterized as I1III2IVX complexes, each containing monomeric complex I, dimeric complex III and 0–3 copies of complex IV, respectively.

Fig. 4. Bovine complex I has binding sites for complex III and complex IV, and ATP synthase can be isolated as a dimer. (A) Complexes a–d and dimeric ATP synthase (VDim) separated by BN-PAGE (Figure 3A; 4 g/g digitonin) were dissociated by 2D BN-PAGE using addition of DDM to the cathode buffer. Direct interaction of complexes I and III was apparent from the dissociation of complex a (I1III2) into monomeric complex I and dimeric complex III. Complexes b–d comprised complex IV in addition (silver staining required for c and d). Dimeric complex V dissociated into the monomeric form VMon. (B) The line of complex b from 2D BN-PAGE (brackets in Figure 4A) was resolved by 3D SDS–PAGE and Coomassie Blue stained. The stoichiometry within this complex (I1III2IV1) was determined by densitometric analysis using purified complexes I, III and IV for calibration. (C) 2D BN-PAGE similar to (A), but using addition of Triton X-100 to the cathode buffer dissociated complex b (I1III2IV1) in a different way (two additional spots larger than complex I; less complex IV dissociated). (D) The line of complex b from 2D BN-PAGE (brackets in Figure 4C) was resolved by 3D SDS–PAGE. The additional spots were identified as undisociated I1III2IV1 complex and as I1IV1 complex. COXI and COXII, subunits of cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV).

From first dimension BN-PAGE (Figure 3A), it was not apparent that dimeric ATP synthase (complex VDim) was located between bands a (I1III2) and b (I1III2IV1). This was detected only after 2D BN-PAGE (Figure 4A), when a second spot for the ATP synthase appeared, which represented ∼10% of total ATP synthase. Decreasing the digitonin/protein ratio from 4 to 2 g/g retained ∼30–40% of ATP synthase in dimeric form, and at a ratio of 1 g/g the dimer was the predominant form (not shown). The ATP synthase dimer was also retained at low DDM (cf. below).

Direct interactions of respiratory chain complexes

Complex I–III interactions were apparent from the presence of a I1III2 complex (Figure 4A). Direct interaction of complexes I and IV became apparent when Triton X-100 instead of DDM was used for 2D BN-PAGE (Figure 4C). Two spots in the line below band b (I1III2IV1) with molecular masses somewhat larger than complex I were characterized by 3D SDS–PAGE (Figure 4D) as undissociated I1III2IV1 complex and as I1IV1 complex containing no subunits of complex III. This indicated that, in contrast to DDM, addition of Triton X-100 for 2D BN-PAGE retained complex I–IV interactions.

Since low Triton X-100 avoided dissociation of complex I–IV interactions, we also used Triton X-100 for solubilization of mitochondria. Under conditions sufficient for quantitative solubilization of all OXPHOS complexes (Figure 5A; 2.4 g Triton X-100/g protein) a few percent of complex I was found assembled into I1III2 and I1III2IV2 complexes (bands a and c). Further I1III2IVX complexes containing up to four copies of complex IV (Figure 5A and B; bands a–e) were obtained using intermediate Triton X-100/protein ratios (1.4–1.6 g/g), which solubilized ∼50% of total complex I. 2D BN-PAGE in the presence of DDM dissociated complex IV dimers from supercomplexes c–e (Figure 5B), which indicated that low DDM can retain complex IV–IV interactions.

Fig. 5. Identification of dimeric complex IV, direct complex III–IV interactions, and complex e (I1III2IV4) comprising four copies of complex IV. (A) BN-PAGE of bovine heart mitochondria using various Triton X-100/protein ratios for solubilization. Low Triton X-100(1.0 g/g) selectively solubilized complexes V and II. High Triton X-100 (2.4 g/g) solubilized all OXPHOS complexes quantitatively, but retained supercomplexes a (I1III2) and c (I1III2IV2). Intermediate Triton X-100 (1.4 g/g) retained supercomplexes a–e (I1III2IVX) comprising0–4 copies of complex IV. (B) 2D BN-PAGE of the boxed sector from (A). Arrowheads mark the lines of dissociated complexes a–e. The identification of dimeric complex IV in lines c–e, but not in b (only one copy of complex IV), indicates the presence of complex IV dimers within the supercomplexes. (C) BN-PAGE of bovine heart mitochondria using high (1.6 g/g) and low (0.6 g/g) DDM/protein ratios for solubilization. Low DDM solubilizes all OXPHOS complexes quantitatively, but retains ∼20% of total complex V in dimeric form (VDim). (D) 2D BN-PAGE of the lane from (C) using low DDM. Arrowheads mark the lines of complexes that were retained after first dimension BN-PAGE but dissociated by 2D BN-PAGE.

Using low DDM for solubilization of mitochondria (Figure 5C; 0.6 g DDM/g protein) and 2D BN-PAGE in the presence of DDM (Figure 5D), we could not only identify dimeric complex IV, but also I1IV1, III2IV1 and III2IV2 complexes as indicators for direct complex I–IV and III–IV interactions. Furthermore, ∼25% of total bovine ATP synthase was present in dimeric form.

Indications for a network of respiratory chain complexes I, III and IV

Indications for a network of respiratory chain complexes I, III and IV were obtained from a comparison of the solubilizing properties of DDM (Figure 5C) and Triton X-100 (Figure 5A). Low DDM (0.6 g/g) solubilized all OXPHOS complexes uniformly and quantitatively, whereas low Triton X-100 (1 g/g) solubilized complexes V and II selectively. Since the detergent/protein ratio used was sufficient for disintegration of lipid areas between mitochondrial complexes, as indicated by the solubilization of complexes V and II, we postulate that the supercomplexes are assembled into much larger structures, which cannot enter the gel. Re-aggregation after solubilization by Triton X-100 seems unlikely since all experience with BN-PAGE indicates that the combination of neutral detergents and the anionic Coomassie dye leads to dissociation of complexes and removal of detergent-labile subunits rather than to aggregations.

Evidence for functional significance of complex I–III association

We analysed the functional significance of stable complex I–III interactions by enzymatic analyses. Frozen and thawed bovine heart mitochondria were solubilized in a buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 75 mM imidazole–HCl pH 7. A considerable electron transport rate of complex I (NADH quinol reductase; Figure 6A) in the absence of detergent indicated that NADH had almost free access to the matrix side of the inner mitochondrial membrane, and non-intact mitochondria were used. The substrate accessibility seemed to be improved by addition of detergent, and almost maximal rates were already obtained before complete solubilization. A similar increase of quinol cytochrome c reductase rates was observed upon solubilization of the membranes (Figure 6B); however, the DDM dependence of the overall NADH cytochrome c reductase rates (complex I+III; Figure 6C) was completely different. The rates initially increased with increasing DDM/protein ratios, which seems to reflect a reduction of accessibility barriers. In a narrow DDM/protein range (0.3–0.6 g/g), which corresponds to membrane solubilization, the rates fell sharply. At first sight, conceivable reasons for that decay are dilution of endogeneous ubiquinone, dissociation of complexes I and III, or both. However, no decrease in rates was observed upon solubilization by digitonin. We conclude that the difference between the rates using DDM or digitonin reflects the presence of separated complexes I and III, or retained complex I–III associations, respectively.

Fig. 6. Functional association of complexes I and III in digitonin-solubilized bovine heart mitochondria. (A) Dergent dependence of NADH ubiquinone reductase (mol NADH oxidized/mol complex I/s). Arrows indicate the solubilization range. (B) Detergent dependence of ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase (mol cytochrome c reduced/mol complex III/s). (C) Detergent dependence of NADH cytochrome c reductase (complexes I+III; mol cytochrome c/mol complex I/s). A decrease in NADH cytochrome c reductase rates after solubilization by DDM indicates a separation of complexes I and III. The absence of a decay of rates after complete solubilization by digitonin indicates a retained association of complexes I and III (cf. text).

The NADH cytochrome c reductase rate of the digitonin-solubilized supercomplexes corresponds to ∼50% of the maximal NADH quinone reduction rate [40 mol cytochrome c reduced/mol complex I/s (Figure 6C) compared with 40 mol NADH oxidized/mol complex I/s (Figure 6A)]. This high NADH cytochrome c reductase rate, measured in the presence of endogenous ubiquinone without addition of synthetic quinones, is a further indicator for direct association of complexes I and III. A doubled NADH cytochrome c reductase rate corresponding to the maximal NADH quinone reduction rate was approached after addition of 50 µM decylbenzoquinone (DBQ) (not shown).

Discussion

Early attempts to isolate OXPHOS complexes from bovine tissues not only yielded isolated complexes, but also combined complexes, e.g. complexes I and III (Hatefi and Rieske, 1967) and II and III (Tisdale, 1967). These enzyme preparations used bile salts, which can lead to protein aggregations. For this reason, and because associations of complexes within the membrane were not detected by antibodies and by liposomal fusion (Capaldi, 1982), not many researchers paid attention to a potential supramolecular organization of the respiratory chain. The isolation of complex III–IV supercomplexes from P.denitrificans (Berry and Trumpower, 1985), the thermophilic bacterium PS3 (Sone et al., 1987) and the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus (Iwasaki et al., 1995a) seemed to be special to these bacteria.

The present isolation of OXPHOS supercomplexes is superior to previous preparative work mainly by its quantitative approach: yeast complex IV does not occur significantly in free form. It is quantitatively associated with complex III, and the amount of the supercomplexes formed depends on the amount of complex IV available at different growth conditions. The amount of supercomplexes seems to reflect the cell’s demand for energy supply via the OXPHOS system.

In mammalian mitochondria, almost all complex I is associated with complex III, and although the isolated supercomplexes were probably not as complete as in the membrane, some complex IV was retained in the form of complex I–III–IV supercomplexes.

What is the functional advantage of supercomplexes compared with separated complexes? The following list of possible advantages of such multienzyme complexes over individual activities has been proposed: substrate channelling, catalytic enhancement, sequestration of reactive intermediates and ‘servicing’ the rapid intramolecular group transfer reaction (Fersht, 1999).

Substrate channelling directs an intermediate to a specific enzyme rather than allowing competition from other enzymes. A major advantage of substrate channelling is the use of a localized substrate molecule (potential candidates are quinol and cytochrome c), which makes a reaction independent of the bulk properties of a substrate pool, e.g. the midpoint potential. The absence of a pool function for cytochrome c in yeast (Boumans et al., 1998) seems to indicate tight substrate channelling. However, in contrast to yeast, a cytochrome c pool function has been shown in mammalian mitochondria (Gupte and Hackenbrock, 1988). Extreme forms of substrate channelling seem to exist in P.denitrificans and in the thermophilic bacterium PS3, since cytochrome c is not removed from the isolated bc1+c–aa3 supercomplexes during conventional isolation procedures (Berry and Trumpower, 1985; Sone et al., 1987). In Sulfolobales, no cytochrome c could be found (Anemüller et al., 1985). However, a heme a583 carrying subunit, which is tightly bound to the quinol oxidase supercomplex, seems to have cytochrome c-like functions (Iwasaki et al., 1995b).

Another possible advantage of supercomplexes is a potential catalytic enhancement by the reduction of the diffusion time of an intermediate (quinol or cytochrome c). Ubiquinol generated at complex I, for example, has a very short diffusion pathway to the associated complex III, but also has access to the quinone pool in mammalian mitochondria (Kröger and Klingenberg, 1973).

Our data on the existence of respiratory chain supercomplexes provide a structural basis for substrate channelling and catalytic enhancement by reduction of diffusion time. Substrate channelling of quinol and cytochrome c would give the highest advantage to the respiratory chain at low substrate concentration. We therefore speculate that substrate channelling is the dominating factor even when a substrate pool exists. This is currently under investigation.

The association of complexes I and III might also be helpful for the sequestration of the reactive intermediate ubisemiquinone, which can react with oxygen to generate superoxide anion radical (Kotlyar et al., 1990). Superoxide is perhaps the main source of reactive oxygen species in mitochondria, and seems to be involved in the pathogenicity of mitochondrial disorders (Robinson, 1998). The potential sequestration of ubisemiquinone can be envisaged as part of a ubiquinone reductase mechanism postulated in the original version of Mitchell’s Q-cycle (Mitchell, 1975; Vinogradov, 1998). ‘The natural ubiquinone reductase reaction may be a result of concerted one-electron reduction of quinone or semiquinone by the dehydrogenase itself, which produces either ubisemiquinone or ubiquinol, and by cytochrome b at centre i of complex III, which provides the second electron to complete the two-electron reduction of original quinone to quinol’ (Vinogradov, 1998).

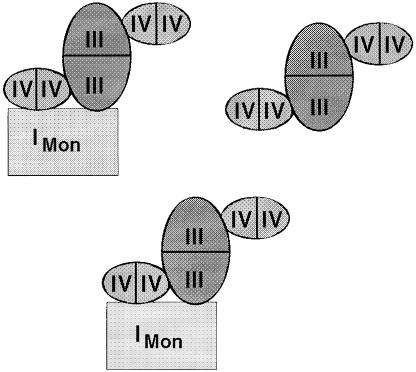

The data presented in this work on the interactions of complexes within bovine heart mitochondria were used to depict a model for a network of respiratory chain complexes that may be called a ‘respirasome’ (Figure 7). This model assumes two copies of a I1III2IV4 building block and one copy of a III2IV4 building block to fit the overall 1:3:6 stoichiometries of complexes I:III:IV, determined by Hatefi (1985). A complete III2IV4 complex was not detected, most likely because complex IV–IV interactions are easily dissociated by detergents in the presence of the anionic Coomassie dye. No association of complex II with any of the other OXPHOS complexes was identified.

Fig. 7. Model for of a network of mammalian respiratory chain complexes. This model is based on the identification of direct interactions of complexes and on the overall 1:3:6 stoichiometry of complex I:III:IV by Hatefi (1985). It postulates two copies of a large building block comprising complexes I, III and IV, and one smaller building block without complex I. Comparison of the different solubilization by DDM and Triton X-100 indicated that these building blocks can interact to form a network of respiratory chain complexes.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains

Haploid wild-type yeast strain W303-1A and a ΔcoxIV strain (Fölsch et al., 1998) were kindly provided by Dr R.A.Stuart. A Δqcr8 strain (CB2; Bruel et al., 1996) was a kind gift of Dr B.Trumpower.

Electrophoretic techniques

Mitochondria from S.cerevisiae W303-1A and from bovine heart were isolated as described (Schägger and von Jagow, 1994; Arnold et al., 1998), and processed for first dimension BN-PAGE as described (Arnold et al., 1998), except that the detergent/protein ratios indicated in the text were used. Strips (1–3 cm) from the first dimension BN-PAGE were then excised and used for a second dimension BN-PAGE. Second dimension BN-PAGE was similar to first dimension BN-PAGE except that gradient gels from 5 to 20% acrylamide were used and 0.02% DDM or 0.03% Triton X-100 were added to the cathode buffer. The protocol for third dimension SDS–PAGE is identical to that for second dimension SDS–PAGE (Schägger and von Jagow, 1994). Staining and quantification of gels (Schägger, 1995) and electroblotting and protein sequencing (Arnold et al., 1998) were performed as described.

Enzymatic analyses

Bovine heart mitochondrial membranes (5 mg/ml) and yeast mitochondrial membranes (2.8 mg/ml) suspended in 150 mM NaCl, 75 mM imidazole–HCl pH 7.0 were supplemented with detergent to adjust variable detergent/protein ratios. After 10 min incubation on ice, all catalytic activities were measured at 22°C using 150 mM NaCl, 75 mM imidazole–HCl pH 7.0 as the test buffer. Cyanide (5 mM) was added to the buffer except for activities comprising complex IV.

NADH ubiquinol reductase (complex I) was measured by the decylquinazolin amine (DQA; Okun et al., 1999) sensitive oxidation of NADH (200 µM; 340–400 nm; ε 3.4 l mM–1 cm–1) using DBQ (75 µM) as electron acceptor.

Ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase (complex III) and cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) were measured by the antimycin-sensitive reduction and cyanide-sensitive oxidation of cytochrome c, respectively (70 µM yeast or bovine heart cytochrome c; 550–540 nm; ε 19 l mM–1 cm–1). DBH (75 µM) was used as the substrate for complex III.

NADH cytochrome c reductase (complex I+III) was measured by the antimycin- and DQA-sensitive reduction of cytochrome c (as above) using 200 µM NADH as electron donor. The catalytic activity was determined with or without added quinone (0–50 µM DBQ).

Yeast ubiquinol oxidase (complex III+IV) was determined by the cyanide-sensitive oxidation of 75 µM DBH (280–290 nm; ε 4.2 l mM–1 cm–1) in the presence of 0–5 µM yeast cytochrome c.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to Gebhard von Jagow on the occasion of his 65th birthday. The authors wish to thank Dr Ulrich Brandt for stimulating discussion. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forsch ungsgemeinschaft, Sonderforschungsbereich 472 Frankfurt and by the Fond der Chemischen Industrie.

References

- Anemüller S., Lübben,M. and Schäfer,G. (1985) The respiratory system of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, a thermoacidophilic archaebacterium. FEBS Lett., 193, 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold I., Pfeiffer,K., Neupert,W., Stuart,R.A. and Schägger,H. (1998) Yeast mitochondrial F1F0-ATP synthase exists as a dimer: identification of three dimer-specific subunits. EMBO J., 17, 7170–7178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry E.A. and Trumpower,B.L. (1985) Isolation of ubiquinol oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans and resolution into cytochrome bc1 and cytochrome c–aa3 complexes. J. Biol. Chem., 260, 2458–2467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boumans H., Grivell,L.A. and Berden,J.A. (1998) The respiratory chain in yeast behaves as a single functional unit. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 4872–4877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruel C., Brasseur,R. and Trumpower,B.L. (1996) Subunit 8 of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cytochrome bc1 complex interacts with succinate–ubiquinone reductase complex. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr., 28, 59–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi R.A. (1982) Arrangement of proteins in the mitochondrial inner membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 694, 291–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fersht A. (1999) Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science. W.H.Freeman & Co., New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Fölsch H., Gaume,B., Brunner,M., Neupert,W. and Stuart,R.A. (1998) C- to N-terminal translocation of preproteins into mitochondria. EMBO J., 17, 6508–6515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler L.R. and Richardson,H.S. (1963) Studies on the electron transfer system. J. Biol. Chem., 238, 456–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupte S.S. and Hackenbrock,C.R. (1988) The role of cytochrome c diffusion in mitochondrial electron transport. J. Biol. Chem., 263, 5248–5253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatefi Y. (1985) The mitochondrial electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation system. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 54, 1015–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatefi Y. and Rieske,J.S. (1967) The preparation and properties of DPNH-cytochrome c reductase (complex I–III of the respiratory chain). Methods Enzymol., 10, 225–231. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki T., Matsuura,K. and Oshima,T. (1995a) Resolution of the aerobic respiratory system of the thermoacidophilic archaeon, Sulfolobus sp. strain 7. I. The archaeal terminal oxidase supercomplex is a functional fusion of respiratory complexes III and IV with no c-type cytochromes. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 30881–30892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki T., Wakagi,T., Isogai,Y., Iizuka,T. and Oshima,T. (1995b) II. Resolution of the aerobic respiratory system of the thermoacido philic archaeon, Sulfolobus sp. strain 7. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 30893–30901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotlyar A.B., Sled,V.D., Burbaev,D.S., Moroz,I.A. and Vinogradov,A.D. (1990) Coupling site I and the rotenone-sensitive ubisemiquinone in tightly coupled submitochondrial particles. FEBS Lett., 264, 17–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kröger A. and Klingenberg,M. (1973) Further evidence for the pool function of ubiquinone as derived from the inhibition of the electron transport by antimycin. Eur. J. Biochem., 39, 313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P. (1975) Protonmotive redox mechanisms of the cytochrome bc1 complex in the respiratory chain: protonmotive ubiquinone cycle. FEBS Lett., 56, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun J.G., Lümmen,P. and Brandt,U. (1999) Three classes of inhibitors share a common binding domain in mitochondrial complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase). J. Biol. Chem., 274, 2625–2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragan C.I. and Heron,C. (1978) The interaction between mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase and ubiquinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase. Biochem. J., 174, 783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich P.R. (1984) Electron and proton transfer through quinones and cytochrome bc complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 768, 53–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson B.H. (1998) Human complex I deficiency: clinical spectrum and involvement of oxygen free radicals in the pathogenicity of the defect. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1364, 271–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schägger H. (1995) Quantification of oxidative phosphorylation enzymes after blue native electrophoresis and two-dimensional resolution: normal complex I protein amounts in Parkinson’s disease conflict with reduced catalytic activities. Electrophoresis, 16, 763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schägger H. and von Jagow,G. (1994) Analysis of molecular masses and oligomeric states of protein complexes by blue native electrophoresis and isolation of membrane protein complexes by two-dimensional native electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem., 217, 220–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sone N., Sekimachi,M. and Kutoh,E. (1987) Identification and properties of a quinol oxidase supercomplex composed of a bc1 complex and cytochrome oxidase in the thermophilic bacterium PS3. J. Biol. Chem., 262, 15386–15391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisdale H.D. (1967) Preparation and properties of succinic-cytochrome c reductase (complex II–III). Methods Enzymol., 10, 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradov A.D. (1998) Catalytic properties of the mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) and pseudo-reversible active/inactive enzyme transition. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1364, 169–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]