Abstract

Soon after its founding in the politically tumultuous late 1960s, the Health Policy Advisory Center (Health/PAC) and its Health/PAC Bulletin became the strategic hub of an intense urban social movement around health care equality in New York City. I discuss its early formation, its intellectual influences, and the analytical framework that it devised to interpret power relations in municipal health care. I also describe Health/PAC's interpretation of health activism, focusing in particular on a protracted struggle regarding Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx. Over the years, the organization's stance toward community-oriented health politics evolved considerably, from enthusiastically promoting its potential to later confronting its limits. I conclude with a discussion of Health/PAC's major theoretical contributions, often taken for granted today, and its book American Health Empire.

FOR ALMOST A DECADE after its founding in 1968, New York City's Health Policy Advisory Center (Health/PAC) served as the strategic hub of a vibrant radical social movement around health care equality, one that paralleled (and sometimes conflicted with) more widely known liberal counterparts of the time. Its Health/PAC Bulletin became an established bimonthly that boasted a wide audience composed of radicalized medical students and physicians and neighborhood activists, on one side, and nervous health administrators at powerful medical centers pilloried in each issue, on the other.

In 1970, Health/PAC published a popular book, American Health Empire, predicting a movement that would “turn the medical system upside down, putting human care on top, placing research and education at its service, and putting profit-making aside.”1 Fueling these proclamations were a series of occupations at city health facilities, leading Health/PAC to ponder the possibility of “creating a wholly new American health care system.”2

Yet, by the mid-1970s, Health/PAC declared itself guilty of “intellectual euphoria” in its founding years as the political energy that had generated so much initial enthusiasm disappeared. In its place were emerging governance regimes that, in many ways, accelerated the concentration of private power in health care that spawned Health/PAC's early analysis in the first place.

In this article, I explain these developments by first detailing the framework that Health/PAC devised to analyze inequality in municipal health care. Second, I turn to the political prescription that followed. Using Health/PAC's analysis of events around the South Bronx's Lincoln Hospital, I examine the organization's invocation of “community” and the notion's power at the time “as the source of political legitimation and its attendant rhetoric of authenticity,” to borrow Adolph Reed's words for a parallel context.3 The potential (and limits) of community-oriented health politics for transformative ends would become the organization's central strategic conundrum. I conclude by considering Health/PAC's legacy and ramifications for public health analysis and practice today.4

ORIGINS

By the end of the 1950s, New York City's public hospital system, once central to its local welfare state, had fallen into disrepair. Persistent complaints circulated of facilities that were dilapidated, overcrowded, and understaffed.5 In response, Mayor Robert Wagner authorized an affiliation plan in 1961 that subcontracted administrative control of the municipal hospitals' “principal clinical departments” to the city's major private medical centers. If the municipal hospitals affiliated, so went the thinking, more and better staff might be attracted to them.6 They might also share the newer medical technology and resources that, increasingly, only the academic medical centers could afford.7 And, affiliation boosters argued, under private administrative control the municipal hospitals would free themselves from city red tape that frequently halted new initiatives.8 By 1965, most municipal hospitals had affiliated to some extent.9

Health/PAC emerged from a 1967 investigation conducted by Robb Burlage, a founding member of Students for a Democratic Society who had helped draft its Port Huron Statement.10 A few years after graduating from the University of Texas, he had begun work at the Institute for Policy Studies, a new think tank funded by left-wing perfume magnate Samuel Rubin (Fabergé).11 Impressed by Burlage, Rubin asked whether he would be interested in investigating the affiliation plan's origins and consequences. Rubin had served on several medical center boards and grown critical of Ray Trussell, the commissioner of hospitals and formerly of Columbia University, one of the city's most powerful medical institutions and private affiliates.

Burlage's report scathingly indicted the affiliation plan. It argued that the benefits of affiliation mostly flowed one way, in the direction of the private medical centers. In practice, he wrote, ceding operation to the latter (and paying for their services) resulted in little public accountability.12 One section of the report elaborated on this issue, charging regular misuse of money paid by the city through affiliations for administration of the municipal hospitals. Accusations included “diversion and use of equipment intended only for city hospitals,” “padding of payrolls and extravagant and uneven offering of professional salaries with city funds,” “use of city funds to provide luxuries and extras,” and “use of city laboratories and research space for projects of the private hospitals.”

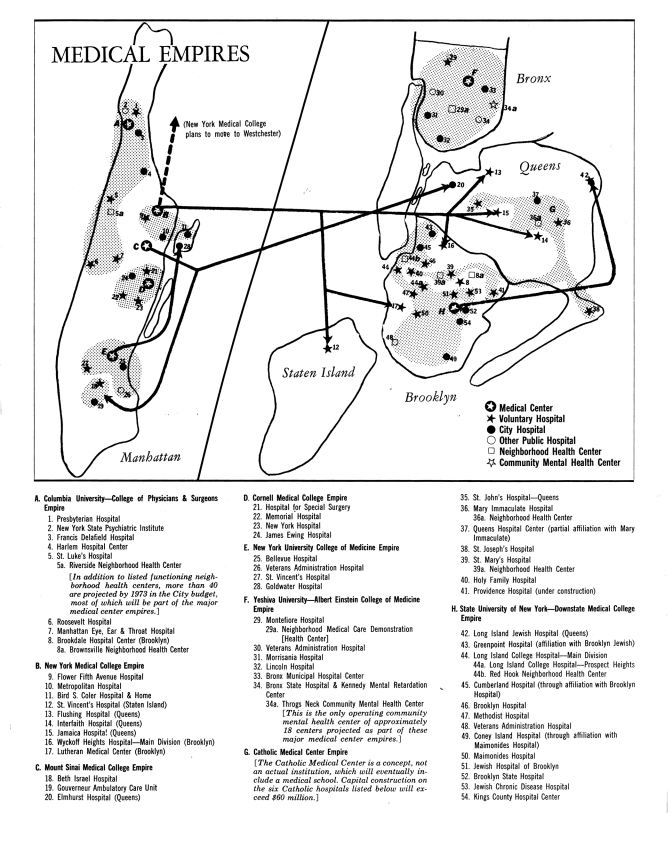

IMAGE 1.

Fold-out map of New York City “Medical Empires,” from the Health/PAC Bulletin (November–December 1968).

Structurally, there existed a “general looseness, wastefulness and lack of direction, of the affiliations program, not just individual cases,” and “city officials were ultimately responsible for not getting sufficient improvements out of affiliation expenditures and arrangements.”13 Rather than move increasing numbers of patients at municipal hospitals to less pressured voluntary (private) ones, many major medical centers in fact did the exact opposite and shuffled or “dumped” their “undesirable” patients from their voluntary hospitals into the municipal affiliates.14

Although shocking, Burlage's empirical findings themselves were not news, as his own report indicated. A 1967 blue ribbon panel reporting to Governor Nelson Rockefeller wrote of “inadequate upkeep of physical facilities,” “shortages and imbalance among the many essential categories of personnel,” and “insufficient funds and rigidity in legal and administrative procedures,” problems that affiliation promised to alleviate.15 A year after Burlage's report, a state commission confirmed multiple fiscal abuses. Some were minor, others far more serious, such as directing affiliation contract funds into interest-accruing accounts benefiting the private medical centers rather than toward municipal hospital improvements.16

Burlage's distinction rested not so much on the revelations about hospital conditions. Rather, it centered on Burlage's interpretation of them and his discussion of where the city ought to go next. Many analysts characterized the problems with affiliation as blights on an otherwise sound idea, ones that could be eliminated with increased oversight. Burlage argued, however, that affiliations as currently practiced were inherently exploitative and unaccountable. His institutional critique denounced “too much uncontrolled domination by the scattered ‘private’ and ‘academic’ sectors of health services.”17 With respect to policy, it called for the creation of a centralized public Metropolitan Health Services Commission that would regulate the municipal hospitals.18

At the same time, Burlage advocated the creation of District and Neighborhood Health Planning and Review Councils composed of residents who would provide bottom-up policy input and devise neighborhood health plans.19 The proposal exemplified a tension in New Left thinking: a supportive but simultaneously uneasy view of post–New Deal centralized state power, which could in fact be put in service of varying ends, not always progressive.20 It reflected, too, the experimentation of the War on Poverty era, particularly its Community Action Program, funds from which were directed to decentralized neighborhood-level projects that mandated public participation.21 And it applied ideas of the New Left political milieu, especially the “participatory democracy” that the Port Huron Statement had introduced into the political lexicon.

Two important themes emerged from Burlage's report: its concern that private incursion into public health domains deprioritized patient care in favor of private medical interests and its contention that patients should have an increased influence on the policies of the medical facilities they used. His work earned significant mainstream press coverage.22 Most importantly, it pleased Samuel Rubin, who shortly afterward suggested creating a permanent center, Health/PAC, that would offer health care analysis in the same vein as the 1967 report. Soon thereafter, Burlage received seed funds from the Samuel Rubin Foundation and the Institute for Policy Studies and appointed as an assistant Maxine Kenny, who had worked previously as an aide to Vermont governor Philip Hoff and with the Committee of Responsibility and Committee of the Professions, two local peace groups opposed to the Vietnam War.23

A year later, in June 1968, Health/PAC released the first Health/PAC Bulletin. It critiqued in detail an official city commission headed by Scientific American publisher Gerald Piel that had also issued a report on the hospitals. Although critical overall, Piel's report took a more favorable view of the affiliations and declared that they had “largely accomplished” one short-term goal, alleviation of the medical staff shortage. It tended to focus more on bureaucratic shortcomings, such as the “divided management” that resulted from an affiliation, and much less on democratizing city health administration.24

After this inaugural issue, Health/PAC continued its withering examination of affiliation, publishing several issues while conducting, in Burlage's words at the time, “a number of seminars and workshops for community organizers, medical students, health worker groups, and dissident professionals” that drew early notice for the organization.25 The sixth issue, published in November 1968, marked a turning point. Although maintaining the Burlage report's analysis, it theorized much more forcefully, likening the relationship between private medical centers and municipal hospitals to colonialism. This comparison was, of course, a byproduct of the time, when many left analysts, especially the journal Monthly Review, debated the geopolitical consequences of near-monopolistic economic concentrations in the post–World War II era.26

Many also sought to explain the dynamics of internal inequality by drawing analogies to colonialism and the underdevelopment that it sustained. In 1962, Burlage himself had written The South as an Underdeveloped Country, which highlighted economic underdevelopment both within the region and in comparison with the North.27 Andre Gunder Frank's work on the “development of underdevelopment” famously characterized the internal dynamics of Brazil and Chile as a “chain of interlinked metropolitan-satellite relationships,” with the affluence of metropoles predicated on the exploitation of satellites.28 And most influentially, Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton, in their Black Power, used the language to describe the relationship of the Black ghetto to American society, characterizing it as internal “colonialism.”29

Critics would later identify shortcomings in this formulation and its elision of critical differences between European colonization and ghetto formation in the United States.30 But might health be different? Given the appalling state of the city's municipal hospitals at the hands of the private medical centers and the dependence of the city's poor racial minorities on them, the colonial metaphor proved apt for the health sector specifically. The sixth issue of the Bulletin captured the power relationship with one word: empire. The accompanying article, “Medical Empires: Who Controls?” declared that

medical research, teaching and specialized services empires, based primarily in seven loose medical school-hospital affiliation networks, are increasingly the centers of power in New York's medical establishment, with mammoth institutional control of the major medical resources in the City.31

A map of the empires showed linkages between the public hospitals and the private medical centers to which they were ceded.

As an antidote, the Bulletin proposed a “De-colonization Program for Health,” word choice influenced by revolutionary “Third Worldism” and swelling anti-imperialist sentiment around the world toward American military aggression in Vietnam and European powers' retreat from former colonies.32 This proposal extended the Burlage report's 1967 recommendations, calling for an “accountable City government agency based in citizen-representative health boards and confederated regional boards” that would oversee a “publicly-approved comprehensive health services plan.” These boards needed to replace top-down medical centers, in other words, as key instruments of health planning.33

Devising strategies for overthrowing the medical empires became Health/PAC's chief goal. In this aim, Health/PAC was often counseled by Harry Becker, a sympathetic professor of community health at Albert Einstein College of Medicine (hereafter referred to as Einstein) and a health policy veteran with decades of government and labor union experience. It began an internship program while its staff expanded to include, at various points over the next few years, Vicki Cooper, Ruth Glick, John Ehrenreich, Barbara Ehrenreich, Oli Fein, Leslie Cagan, Susan Reverby, Connie Bloomfield, Marsha Handelman, Ken Kimmerling, Ronda Kotelchuck, Des Callan, and Howard Levy.34 All had participated in civil rights, women's, antiwar, antipoverty, or student struggles of the decade. However, other than the physicians in the group—Callan, Fein, and Levy—they came to the world of health care as outsiders.

Health/PAC's popularity kept growing as its staff continued engaging media outlets, universities, and political groups through its busy speakers' program.35 Its office became a go-to place for people to ask questions about health care, and activists made frequent use of Health/PAC's dissections of esoteric municipal health policy. Links between analysis and action became apparent at the Lower East Side's Gouverneur Health Services, one of the first community health centers funded by the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO).36 Activists of the Lower East Side Health Council-South, a government-mandated watchdog, increasingly believed that Beth Israel Medical Center, a private affiliate of Gouverneur that actually received the OEO funds, viewed it as a dismissible token. Beth Israel's seemingly arbitrary employee reassignments and cancellations of Gouverneur neighborhood health programs brought these tensions to a pitch. Soon after Health/PAC's appearance, Council members began challenging Beth Israel administrators on arcane policy points. A Bulletin article summarized one episode:

When Beth Israel (the affiliating hospital for the Gouverneur Health Services) turned over its 175 page plus proposal for OEO funds to the Health Council, as mandated by OEO regulations, few thought the Health Council would be able to master the document. To Beth Israel's surprise and consternation, the Health Council's review of the proposal included a thorough analysis and some severe criticism of the hospital's program priorities with an explicit statement of the Council's own priorities and appropriate justification.37

Terry Mizrahi, a Lower East Side community organizer, recalled later that the relationship between the Council and Health/PAC “was one of reciprocity and exchange … each of us learning from and educating the other,” the organization a provider of “advice and direction as we [the Council] discussed political and technical strategies, conducted open community meetings, and held behind-the-scenes negotiations.”38

When discussing political transformation, however, Health/PAC focused most extensively on Einstein Medical College, the affiliate of Lincoln Hospital in the economically devastated South Bronx.39 From the agitation around Lincoln, Health/PAC generated (and constantly revised) new ideas about the transformation of the health sector.

BATTLE IN THE SOUTH BRONX

Prior to Heath/PAC, most health activists directed their energies toward conservative organizations such as the American Medical Association.40 By contrast, Health/PAC directed its wrath toward what it perceived as liberal hypocrisy couched in the language of progressive social medicine. One Bulletin editorial stated that liberal “promoters” such as Einstein

have tended to direct their energies for “reform” in the most arrogant, dogmatic and unaccountable fashion. Even while rhetorically espousing “progressive” principles of medical system reorganization, they have engaged in wasteful inter-institution competition, hustling scarce manpower on a fee-basis, and scrapping over “teaching material.” … The irony is that these corporate liberals of the medical establishment have begun to imitate the competitiveness and self-interest of the solo, fee-for-service systems of which they are often so critical.41

An internal Einstein document seemed to substantiate such an analysis. On reasons why Einstein ought to continue its Lincoln affiliation, the document listed “needed for teaching,” “needed for financial support of school,” and “needed for health care research.” At the bottom (perhaps tellingly so) was “needed so School can meet its obligation to help with contemporary problems, to heal the sick poor etc.”42

Einstein showcased the contradictions of the affiliation plan like few other institutions. Under affiliation, Lincoln Hospital remained one of the country's worst urban hospitals. An internal Einstein report described Lincoln as

a hopelessly inefficient and inadequate building which would be useless for the running of a modern hospital for a population of 350,000 even if it were in brand new condition. As it is, the dirt and grime and general dilapidation make it a completely improper place to care for the sick or even run the complex administrative machinery that is required to do this.43

It was a “constant daily reminder to all who are in it of their futility and impotence: to the patient who gets sick in a dirty slum and enters a dirty slum for treatment it must mean that ‘they’ do not really care or try.”44

During 1969 and 1970, neighborhood residents, hospital service workers, and young physicians expressed anger over conditions at Lincoln. In 1969, politicized workers in its mental health unit seized control of the facility. They administered it by themselves for weeks, arguing that their day-to-day contact from actually living in patients' neighborhoods gave them unique insight on how to run it, knowledge that typical medical administrators did not possess.

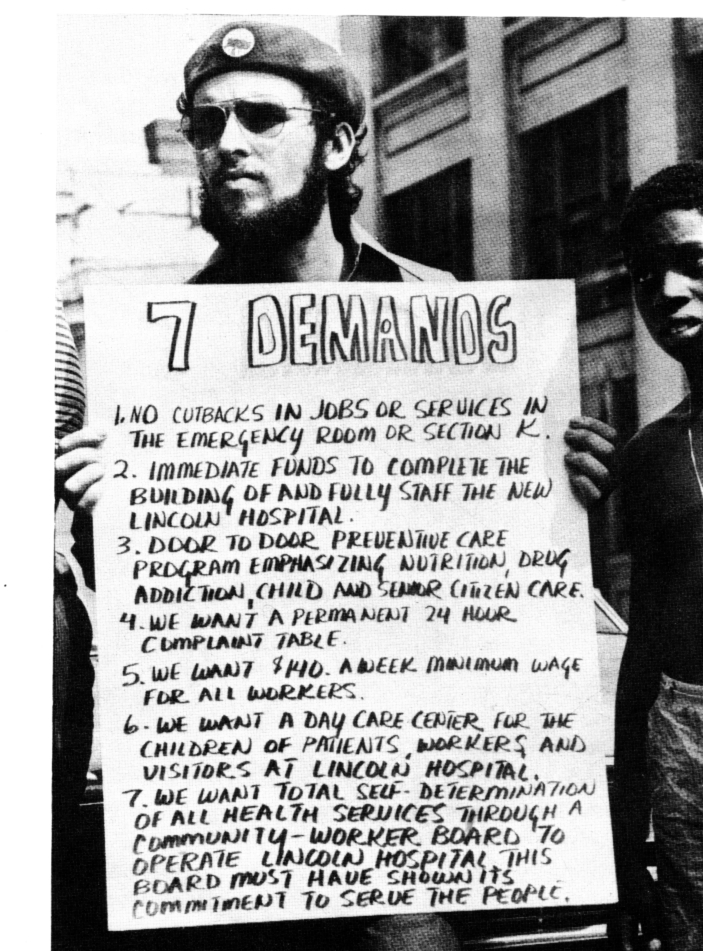

In July 1970, the Young Lords, a radical Puerto Rican nationalist group, occupied Lincoln Hospital for one day, drawing considerable public attention.45 An adjunct organization called the Health Revolutionary Union Movement (HRUM), composed mostly of Young Lords and Lincoln health workers (almost all members of racial minority groups), had demanded “total self determination of all health services through a community-worker board to operate Lincoln Hospital.”46 On top of this was a group of radical residents and interns who called themselves the Lincoln Collective. Centered in the hospital's pediatric ward, they advocated for many changes in hospital protocol, especially more neighborhood involvement in administration.47

Health/PAC reacted effusively. Of the mental health worker takeover, an editorial declared that “community-worker forces are beginning to give ‘the boot’ to the arbitrary rule of autocratic grantsmen and hierarchical professionals.”48 After the Young Lords' action, Barbara Ehrenreich weighed in favor of the new Third World political groups by declaring that chances of a victory were “mounting”. Noting other nascent health struggles around the city, she declared that Lincoln might “become the first hospital, if not the first multi-million dollar American institution of any kind, to be run by and for the people it should be serving.” Ehrenreich thus designated the radical community-worker organizations as primary catalysts for change in the health care sector.49 More quietly, the mainstream Medical Tribune and Medical News also noted the events but added skeptically (and crucially) that there “remains, however, the question of whether the staff rebels who have done the kicking are, in fact, the community.”50

Over time, the two chief groups agitating at the hospital, HRUM and the Lincoln Collective, found that community-worker control proved difficult both to define concretely and to implement in practice. Although neighborhood residents had shown considerable initial interest in the efforts around Lincoln, organizing them on a more sustained basis (as opposed to mobilizing support for periodic actions) was something else entirely.51 After a year and a half, in January 1972, Lincoln activism received an extended revisit from Health/PAC's Susan Reverby and Marsha Handelman. It differed considerably from the organization's prior assessments of health activism, such as the excited articles after the 1969 and 1970 events and Health/PAC's American Health Empire book, published in late 1970, that included a final chapter titled “The Community Revolt: Rising Up Angry.”

Reverby and Handelman, by contrast, were much more cautious as they dissected the community-worker control idea. They argued that radical health workers, represented by HRUM, were far more reliable catalysts for change than an elastically and vaguely defined “community,” writing that “the community residents' relationship to the hospital is episodic; people only come when they are ill.” “In contrast,” they continued, “the non-professional and professional workers are at Lincoln every day; it is a focus and a definition for their lives. From this base changes at Lincoln have come.”52

IMAGE 2.

Protest outside Lincoln Hospital, circa 1970, from Harold Osborn, “‘To Make a Difference’: The Lincoln Collective,” Health/PAC Bulletin (Summer 1993): 19–20.

Their piece decidedly favored HRUM over the Collective as a key source of transformation. Reverby and Handelman described the Collective's difficulties with devising a coherent political program and charged that the group's support of HRUM and the Young Lords resulted from “the politics of guilt and the politics of adventurism.” The Collective's commitment to “the community” arose “out of a romantic notion about the medical savior who leads other people's struggles; or the voyeuristic tendency that defines a ‘total politic’ as ‘rapping with the Lords.’ ”53

Still, they argued that Lincoln represented “one of the first thin threads of a sustained struggle to achieve worker-community control within a health institution.” It had “made some steps toward emancipation” and could serve as a model for “institutional organizing,” a New Left formulation that predicted changes in more and more institutions would accumulate into subsequent total change in a given sector and the society writ large.54

IMAGE 3.

Bill Plympton cartoon depicting the impact of fiscal crisis on health care, from “NYC Public Hospitals: Courting Extinction,” Health/PAC Bulletin (March/April 1976): 27.

Within the hospital, the Lincoln groups were able to introduce some significant internal reforms: a continuity-of-care system, a certain degree of parental decision making in the hiring of pediatric staff, and Lawrence Weed's much more rigorous “problem-oriented” system of patient record keeping.55 One year, the pediatrics department's infant care program received a rating nearly 30 points higher than the average in a city study of hospitals.56

Nevertheless, racialized class tensions developed and persisted between politicized hospital workers and the Lincoln Collective's young White radical physicians. One manifestation occurred during a dispute over meal tickets. At Lincoln, the physicians were entitled to free meals, but workers and nurses were not. HRUM proposed that the physicians, to show solidarity, start paying for meals like everybody else, but the Lincoln Collective failed to reach consensus. The real problem was not the minor surface issue of meal tickets. Rather, it was whether the Collective's members could ever conceive of themselves not as professionals but as a “proletariat” like any other and put that conception into real practice, as HRUM demanded.

One Collective member objected to such proletarianization of professionals and declared that he did not think revolution would “be led by workers in a traditionally Marxian concept.”57 At another meeting, members noted a “lack of unity” and expressed frustration over their “failure … to relate” to “other health struggles throughout the city and country.”58 Activism around Lincoln and the South Bronx—and other city sites with more moderate conflict—was indeed declining dramatically, along with political morale.

And whatever forms of community control were won, long-standing structural problems endured. Across the city, the affiliation program had yet to undergo overhaul even with the 1970 creation of the new Health and Hospitals Corporation, a public benefit corporation somewhat resembling what Burlage had advocated in his initial report but lacking many of his suggested structures for public participation. Lincoln's physical plant seemed, at times, irreversibly deteriorated. In mid-1973, Lincoln physicians Peter Schnall and Al Ross identified more than 40 hospital inadequacies, including a lack of basic supplies, 2-hour average waiting times in the pharmacy, and poor patient privacy in examination rooms.59

In late 1974, Lincoln briefly lost accreditation from the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals.60 Some Lincoln activists began to see the limits of single-institution organizing, although small doubts had always existed. As early as 1972, Mike Steinberg, an ardent advocate of such an approach at Lincoln, lamented:

It is not enough to change just one hospital or just the medical system. To meet the health and living needs of all the people in the country, we need a more fundamental change of government in the society. It would be a token to have community-worker control of this hospital and provide good services if people are going to live in miserable housing, if they don't have jobs, if they are forced to be on welfare.61

New York City, moreover, became embroiled in a protracted fiscal crisis resulting in an austerity regime that led to medical facility closures, service cutbacks, and layoffs.62 From 1975 to 1980, Charles Brecher recounts, Health and Hospitals Corporation spending growth was “virtually frozen,” in contrast to the previous five years, when expenditures had risen 54%.63

The New Deal–New Left tension that always existed in Health/PAC came to the fore. Health/PAC had spent its early years attacking a state apparatus that it argued served as a handmaiden to the city's powerful and concentrated private medical interests. Now, it (along with much of the political left) ironically found itself defending that very apparatus as it came under attack from banking interests and the political right.64

A simultaneous tension between centrally and locally oriented politics also surfaced. Amid these macroeconomic woes, the overall political potential of highly local actions around health care seemed much smaller. In the larger political picture, how much did local nodes of political power really matter when stacked against these macrostructural changes and the decisions of powerful centralized political bodies? The question had always lurked quietly in Health/PAC's thinking. In a speech several years earlier, for example, Oli Fein mentioned the possibility that community control in fact “deflect[ed] challenges, particularly about the allocation of resources, from the national level where they should be.”65 For many activists, mounting structural economic woes threw this dilemma into relief: whether, in historian Thomas Sugrue's words, “the problem was not one of governance” but ultimately “one of resources.”66

In one of the final pieces that discussed the Lincoln events extensively, published in 1975, Health/PAC staffers Howard Levy and Ronda Kotelchuck reexamined their organization's valorization of community politics and its insurgent potential. They suggested that “the romanticization of these early institutional struggles, while intending to move health workers elsewhere to join the struggle, ultimately had the opposite effect—the blocking of a process of thought that might lend clarity, direction, vision and strength to strategic options and implications of institutional organizing.”67 “The end result of such unreflective and unwarranted positivity,” they concluded, “was epidemic disillusionment, divorce from reality and fostering of false premises, all of which were without doubt self-defeating.”68 The article served as critical self-recognition of the organization's tendency to equate political synecdoches—in Health/PAC's case, “community” or “community-worker” and their purported spokespeople—with larger foment that turned out to be much more tenuous than earlier militancy had suggested.69

With the parallel decline and demobilization of the political left more generally, Health/PAC confronted a crisis of purpose. In the latter half of the 1970s, low spirits surfaced in staff meetings characterized by one office memo as “abominable, interminable, intolerable and ineffective.”70 Many staffers described the post-1960s political landscape as one of “isolation.”71 Others noted that their career goals (and the mundane pressures of everyday life) potentially conflicted with their political ones.72 The problem of funding loomed, sparking impassioned debates about whether Health/PAC ought to suspend the Bulletin, affiliate with a university, convert to a volunteer organization, or raise money from more traditional foundations.73

Some of these proposals signaled changing times. Health/PAC, after all, had begun by spotlighting the powerful influence that large, well-funded, and impersonal organizations—universities and establishment foundations among them—exerted over the health sector. It now found itself in the odd position of considering whether its existence might well depend much more heavily on them.

Eventually, the organization survived with small-foundation support (including a recommitment from Rubin), its subscriber base, and later, well-known parties at the American Public Health Association's annual meetings.74 In 1978, it changed from an organization with a full-time staff to one run by a volunteer editorial board and increasingly relied on submissions and solicited pieces.75 Until eventually folding in 1994, the Bulletin took the form of a left–liberal health policy journal in both style and substance. But it by no means abandoned coverage of on-the-ground struggles entirely, publishing issues on activism around HIV/AIDS, environmental justice, and occupational and women's health.

HEALTH/PAC'S SYSTEMIC ANALYSIS

Although focused mainly on New York City events and agitation in these early years, Health/PAC soon developed a national-level analysis of political economy and health care. The November 1969 Bulletin introduced “medical industrial complex,” a key term for which Health/PAC became known.76 One article in the issue argued that although billions flowed into the medical industry each year, the money rarely made its way into qualitative improvements for primary patient care and instead flowed to a myriad of profiteers:

This year the nation will spend over $62 billion on medical care, up more than 11 percent over last year and twice the 1960 level. $6 billion of this will flow into the hands of the drug companies, almost $10 billion will go to the companies that sell doctors and hospitals everything from bed linen to electrocardiographs, $35 billion will be spent on “proprietary” (profit-making) hospitals and nursing homes. The nation will purchase $6 billion worth of commercial health insurance and construction companies will build about $2 billion worth of hospitals.77

The issue depicted webs of privately owned drug companies, insurance firms, stockholders, financial interests, and hospital and nursing home proprietors transferring enormous profits among themselves, with patient care a second thought. Health providers themselves were but a small component—“little more than a front for the industry”—in this bleak national picture.78 Although supporting more federal spending on health, the issue cautioned that the increase would be “wasted” unless “developmental programs and spending priorities” within the system changed drastically.79

These lines were aimed at Medicare and Medicaid, two reforms of the Lyndon Johnson administration initiated in 1965 that expanded federal dollars for health expenditures of senior citizens and the poor. Ehrenreich and Ehrenreich interpreted them as a boon for private health profiteers who saw the new programs as a new source of money.80 “For years,” they wrote, “the government has directly or indirectly fed dollars into the gaping pockets of the dealers in human disease.”81 This position underpinned Health/PAC's interpretation of liberal proposals for national health insurance, which it attacked for being too conservative and again saw as public money earmarked to help citizens pay for private health costs, thus enhancing the profit margin of private interests receiving the latter.82

Beyond the benefits to private medical interests, Health/PAC attacked the narrow fiduciary orientation of the reforms, arguing that “the primary emphasis of all proposals for National Health Insurance has been the financial rather than the reorganizational aspects of the health delivery system.”83 The Bulletin called instead for a national health service and a fundamental reorganization of the system's quantitative as well as qualitative aspects.84

Health/PAC's first book, American Health Empire, synthesized Health/PAC thought. Its remarkable introduction brought the reader into the lived experience of a typical urban health patient caught in the medical–industrial complex. For this patient, modern health care had become a daunting labyrinth:

He can only hope that at some point in time and space, one of the many specialty clinics to which he has been sent (each at the cost of a day off from work) will coincide with his disease of the moment.85

Doctors and treatments were esoteric, whereas “the patient himself is usually sick-feeling, often undressed, a nameless observer in a process which he can never hope to understand.”86

Medicine was institutionally racist and colonial, with non-White patients the colonial subjects—the “teaching material”—of White doctors.87 And it was sexist and demeaning:

A shy teenager from a New York ghetto reports going to the clinic for her first prenatal check-up, and being used as teaching material for an entire class of young, male medical students learning to give pelvic examinations.88

Bulletin readers were familiar with the message. Profit motive, research interests, and teaching through the use of poor patients all trumped quality of care.89 The only way to reorder these perverse priorities, the book's introduction concluded, was “to marshall all the force of public power to take medical care out of the arena of private enterprise and recreate it as a public system.”90 If nothing else, American Health Empire represented a sharp departure from the medical triumphalism of the previous decade. It remains a landmark critique of American health care in the post–World War II period.

HEALTH/PAC'S LEGACY

Bad health, as Mike Steinberg noted, stemmed from myriad forces: neglected housing that caused poisoning from lead paint; inadequate ventilation that resulted in tuberculosis; a dead-end job market that resulted in depression, alcoholism, and drug addiction; and pervasive segregation that made such housing characteristic among the city's poor minorities.91 As a formulation, Health/PAC's medical industrial complex viewed the health sector as one deeply constrained—unavoidably so—by the dynamics of the capitalist political economy in which it was embedded. Nowadays, knowingly or not, the notion is taken for granted in both mainstream and radical writing documenting the financial streams and major monetary stakes in the big business of health.92

To some, Health/PAC's left critiques of national health insurance may seem excessive in retrospect, but they contain much truth. Converting the financial stream within the health system to public dollars does not eliminate all of the exploitative interests through which that stream travels. Yet much health policy discussion, as the constricted recent debate over health reform has shown, has devolved into a narrow focus on financing and insurance alone that obscures the quality of patient experience and conditions on the ground. Health/PAC repeatedly insisted that qualitative and quantitative aspects of health care could not be divorced. Its vivid “medical empire” analogy captured an underside to American medicine demarcated by racial and class lines.

To be sure, work on health disparities is much more plentiful today. But it often lacks a sophisticated interpretive political framework like Health/PAC's. More common is public health research that is narrowly quantitative and econometric, flattening complex sociological processes into factors and variables for statistical models. Much of its development parallels well-meaning poverty research, which transformed, Michael Katz observes, into “a special interest” where “survival depended on a steady and copious stream of research dollars,” and “hype and self-justification became inevitable,” often resulting in underwhelming analysis.93 It is thus unsurprising to see regular calls for more sophistication in public health thinking.94

In municipal health care, the lax regulatory climate that first spurred Health/PAC is gone.95 But in actual practice, the fundamental conflict between private interests and the public's health remains. In recent years, for example, reports of illegal dumping have come out of Los Angeles, leading to investigation and prosecution by the city attorney against several hospitals. One cannot help but recall Lincoln Hospital and Einstein when reading about the travails of Los Angeles' King-Drew Medical Center (restructured and renamed in 2007) and its private affiliate, Charles Drew University of Medicine and Sciences.

We continue wrestling with the politics of “community”—a term invoked frequently (and often mystically) yet imprecisely in public health—and the associated search for sources of transformation in health provision. Historical and present efforts related to government health insurance have been propelled mainly by middle-class reformers, not more popular constituencies.96 With some exceptions, mass organizing around health equality remains difficult.

Health/PAC's crowning achievement was situating health care politics in a wider political–economic context and bringing intellectual rigor to activism.97 It struggled constantly with identifying the most promising methods for change in the health sector, but it must be credited, too, with revisiting that question, often in a ruthlessly self-critical way. Class medicine and obscene health inequalities remain stark. Forty years after American Health Empire, we would all do well to recall Health/PAC's political spirit and analytic totality and to revive the ambitious parameters of debate that it set.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Sean Greene, Karen Tani, and Ava Alkon for reading drafts. Walter Lear, Susan Reverby, and David Rosner have shared many important insights on health activism with me. At the University of Pennsylvania, my thanks to Adolph Reed, Tom Sugrue, David Barnes, Michael Katz, and Steven Hahn, and during an earlier incarnation of this ongoing project at Columbia University, Eric Foner, Samuel Roberts, Betsy Blackmar, and Herbert Gans.

Endnotes

- 1. Barbara Ehrenreich and John Ehrenreich, ed., The American Health Empire: Power, Profits, and Politics (New York: Random House, 1970), 27–28.

- 2. Ibid.

- 3. Adolph Reed, “Sources of De-Mobilization in the New Black Political Regime: Incorporation, Ideological Capitulation, and Radical Failure in the Post-Segregation Era,” in Stirrings in the Jug: Black Politics in the Post-Segregation Era, ed. Adolph Reed (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 136. This article's thinking on political communitarianism and its “rhetoric of authenticity,” in Reed's words, are influenced heavily by Reed, “The Curse of Community,” in Class Notes: Posing as Politics and Other Thoughts on the American Scene, ed. Reed (New York: New Press, 2000) and Rogers Brubaker, “Ethnicity Without Groups,” in Ethnicity Without Groups, ed. Brubaker (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004). For earlier meditations on such rhetoric within the medical care context, see the important essays in John C. Norman, ed., Medicine in the Ghetto (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1969)

- 4. This work joins a small but growing literature on American social movements around health care in the 20th century, including Sean Greene, The Political Creation of King-Drew Hospital: Politics, Health Care, and the Struggle for Racial Justice in Los Angeles, 1965–1975 (PhD dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, forthcoming); Ava Alkon, Late 20th-Century Consumer Advocacy and the Uses of Science: An Historical Study of Public Citizen's Health Research Group (PhD dissertation, Columbia University, forthcoming); Naomi Rogers, “Caution: The AMA May Be Dangerous to Your Health: The Student Health Organizations and American Medicine 1965–1970,” Radical History Review 80 (2001): 5–34. See also John Dittmer, The Good Doctors: The Medical Committee for Human Rights and the Struggle for Social Justice in Health Care (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2009); Elizabeth Fee and Theodore Brown, ed., Making Medical History: The Life and Times of Henry E. Sigerist (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997); and Lily Hoffman, The Politics of Knowledge: Activist Movements in Medicine and Planning (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989). The last is an excellent sociological analysis of 19 groups, including Health/PAC, that focuses particularly on the boundary between activist and professional roles. See Hoffman, 159–171. For a brief overview of these movements and the tradition from which they come, see Walter Lear, “Health Left,” in Encyclopedia of the American Left, ed. Mari Jo Buhle, Paul Buhle, and Dan Georgakas (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 300–306.

- 5. My analysis in this section owes much to the historiography on the American hospital and the transformation and contestation around its role, including David Rosner, A Once Charitable Enterprise: Hospitals and Health Care in Brooklyn and New York, 1885–1915 (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2004); Charles E. Rosenberg, The Care of Strangers: The Rise of America's Hospital System (New York: Basic Books, 1987); Rosemary Stevens, In Sickness and in Wealth: American Hospitals in the Twentieth Century (New York: Basic Books, 1989); and, especially for the New York City context, Sandra Opdycke, No One Was Turned Away: The Role of Public Hospitals in New York City since 1900 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999)

- 6. Opdycke, No One Was Turned Away, 111–112; Dorothy Levenson, Montefiore: The Hospital as Social Instrument (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1984), 235.

- 7. R. A. Milliken and D. D. Pointer, “Organization and Delivery of Public Medical Care Services in New York City,” New York State Journal of Medicine 103 (1974): 99–100. [PubMed]

- 8. Opdycke, No One Was Turned Away, 111–112; Charles Brecher, Raymond Horton, Robert Cropf, and Dean Michael Mead, Power Failure: New York City Politics and Policy since 1960 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 331–333.

- 9. Milliken and Pointer, “Organization and Delivery,” 102.

- 10. Gregg Michel, Struggle for a Better South: The Southern Student Organizing Committee, 1964–1969 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 40.

- 11. Robb Burlage, “The Founding Story” (paper presented at the Health Policy Advisory Center Reunion, New York City, June 6, 2009); Health/PAC Bulletin (June 1968): 3. Dorothy Burlage, “Truths of the Heart,” in Deep in Our Hearts: Nine White Women in the Freedom Movement, Constance Curry, Joan Browning, Dorothy Burlage, et al. (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002), recounts Burlage's political activities during this time period. See also the “Editors' comment” in Burlage, “The American Planned Economy,” circa 1965, in Box 1, Folder 7, Papers of Robb Burlage, Wisconsin Historical Society. This is a revision of a 1963 Students for a Democratic Society mimeograph.

- 12. Robb Burlage, New York City's Municipal Hospitals: A Policy Review (Washington, DC: Institute for Policy Studies, 1967)

- 13. Ibid., 262.

- 14. Ibid., 224, 328, 404–415.

- 15. Report of Blue Ribbon Panel to Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller on Municipal Hospitals of New York City (Albany: New York State Department of Health, 1967), 2, 13–15.

- 16. State of New York Commission of Investigation, Recommendations of the New York State Commission of Investigation Concerning New York City's Municipal Hospitals and the Affiliation Program (New York: Community Council of Greater New York, 1968), 1–32, 47–55.

- 17. Burlage, New York City's Municipal Hospitals, 262.

- 18. Ibid., 515–520.

- 19. Ibid.

- 20.Burlage's advocacy of both a centralized public authority and strong, decentralized neighborhood health boards may have reflected his multiple ideological influences during his college years. He took classes with a pair of left-leaning statist economics professors but was also introduced by a journalistic mentor to the anarchist theorist Piotr Kropotkin. On this, Doug Rossinow writes: “Burlage came to favor an activist government that could forge economic order and equity. At the same time, he was touched by the antistatist currents running through Texas.” See Rossinow, The Politics of Authenticity: Liberalism, Christianity, and the New Left in America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 34–36. The tension is also visible in Burlage, “The American Planned Economy,” in which he critiques the lack of post–World War II American economy planning and surveys varieties of planning without conclusively favoring one over the other. For example: “All prescriptions for social change in our society must have at least an implicit notion of the nature of ‘planning’ and decision-making in the ‘political economy’ in which we live: from Gunnar Myrdal's urging for more public national planning (in Beyond the Welfare State); to those of the pundits of the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions for ‘democratization’ of and social responsibility in the ‘metrocorporation’; to Paul Goodman's pleas for new models of decentralization (see People and Personnel, New York: Random House, 1965).”

- 21. On the Office of Economic Opportunity and the Community Action Program, see Alice O'Connor, Poverty Knowledge: Social Science, Social Policy, and the Poor in Twentieth-Century U.S. History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001), 158–173; Michael B. Katz, The Undeserving Poor: From the War on Poverty to the War on Welfare (New York: Pantheon Books, 1989), 95–101; Katz, In The Shadow of the Poorhouse: A Social History of Welfare in America (New York: Basic Books, 1986), 267–269; and Kent Germany, New Orleans After the Promises: Poverty, Citizenship, and the Search for the Great Society (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007)

- 22. Edward Burks, “Reforms Advised in City Hospitals,” New York Times (May 11, 1967): 58.

- 23. Robb Burlage, “Subject: A Brief Progress Report on Health-PAC,” September 17, 1968; Maxine Kenny to Fred Stuthman, November 8, 1968, Part I, Box 28, “Institute Policy Studies (IPS) I” folder, Papers of the Health Policy Advisory Center (Health/PAC), Special Collections, Paley Library, Temple University (hereafter referred to as the Health/PAC papers); Burlage, “The Founding Story” (paper presented at the Health Policy Advisory Center Reunion, New York City, June 6, 2009); Health/PAC Bulletin (June 1968): 3.

- 24. Commission on the Delivery of Personal Health Services, Community Health Services for New York City (New York: Praeger, 1968), 28–31, 301–321. See also Opdycke, No One Was Turned Away, 151–153, and for an excellent appraisal of the Piel commission's ambiguous prescriptions, see Robert Alford, Health Care Politics: Ideological and Interest Group Barriers to Reform (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975), 54–93.

- 25. Burlage, “A Brief Progress Report.” For some early responses, see “Letters to the Editor” in the August 1968 issue of the Health/PAC Bulletin.

- 26. Paul A. Baran and Paul M. Sweezy, Monopoly Capital: An Essay on the American Social and Economic Order (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1966); C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite (New York: Oxford University Press, 1956); and, later, Harry Magdoff, The Age of Imperialism: The Economics of U.S. Foreign Policy (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1969). Also important is the term “corporate liberalism,” used most notably by James Weinstein, The Corporate Ideal in the Liberal State, 1900–1918 (Boston: Beacon Press, 1968), and Carl Oglesby, 1965 Students for a Democratic Society president, in his famous speech “Liberalism and the Corporate State,” reprinted in The New Radicals: A Report with Documents, ed. Paul Jacobs and Saul Landau (New York: Vintage Books, 1966)

- 27. Robb Burlage, The South as an Underdeveloped Country (Nashville, TN: Southern Student Organizing Committee, 1962)

- 28. Andre Gunder Frank, Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America: Historical Studies of Chile and Brazil (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1967), 16.

- 29. Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America (New York: Random House, 1967), especially chapter 1. See also Robert Allen, Black Awakening in Capitalist America: An Analytic History (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1969), and Robert Blauner, “Internal Colonialism and Ghetto Revolt,” in Racial Oppression in America (New York: Harper & Row, 1972)

- 30. Two sharply critical appraisals of the concept at the time are Christopher Lasch, “A Special Supplement: The Trouble with Black Power,” New York Review of Books 10 (1968): 4-14, and Donald Harris, “The Black Ghetto as Colony: A Theoretical Critique and Alternative Formulation,” Review of Black Political Economy 2 (1972): 3–33. Three excellent intellectual–historical approaches to the concept are Katz, The Undeserving Poor, 52-65; Ramon Gutiérrez, “Internal Colonialism: An American Theory of Race,” Du Bois Review 1 (2004): 281–295; and Dean Robinson, Black Nationalism in American Politics and Thought (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 81–84.

- 31. “Medical Empires: Who Controls?” Health/PAC Bulletin (November–December 1968): 1–6.

- 32. On the relationship between the Vietnam War and anti-imperialism in the United States, see Maurice Isserman and Michael Kazin, America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 188–194, and Kirkpatrick Sale, SDS: The Rise and Development of the Students for a Democratic Society (New York: Random House, 1973), 362–363, 400–402. Max Elbaum, Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Mao and Che (London: Verso, 2002), 24–58, examines the influences of China and Cuba in addition to Vietnam.

- 33. “A De-Colonization Program for Health,” Health/PAC Bulletin (November–December 1968): 1.

- 34. “Health-PAC Student Internship Program,” April 1972, Part I, Box 28, “Student Internship” folder, Health/PAC papers. I draw these biographical statements from “Appendix II: Staff” of this document and a series of interviews conducted with Burlage, Kotelchuck, Levy, Fein, and Reverby during 2004–2005. I have maintained surnames used at the time. On Callan, see also Hoffman, The Politics of Knowledge, 94; on Fein's organizing background in Students for a Democratic Society, see James Miller, Democracy Is in the Streets: From Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994), 191–208; on Levy, see Robert N. Strassfield, “The Vietnam War on Trial: The Court Martial of Dr. Howard B. Levy,” Wisconsin Law Review 4 (1994): 839–963.

- 35. Health/PAC, “Semi-Annual Report,” July 1972, Part I, Box 28, “Health-Pac semi-annual report” folder, Health/PAC papers.

- 36. On the history of the community health center program, see Bonnie Lefkowitz, Community Health Centers: A Movement and the People Who Made It Happen (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2007); Alice Sardell, The U.S. Experiment in Social Medicine: The Community Health Center Program, 1965–1986 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1988); and Jonathan Engel, Poor People's Medicine: Medicaid and American Charity Care since 1965 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 53–55, 98–103, 135–138.

- 37. Ruth Glick and Oliver Fein, “Turning the Other Deaf Ear,” Health/PAC Bulletin (July–August 1969): 10.

- 38. Terry Mizrahi, “Coming Full Circle: Lessons from Health Care Organizing,” Health/PAC Bulletin (Summer 1993): 12–15. [PubMed]

- 39. The potentially confusing relationship between the Einstein College of Medicine and the Montefiore Medical Center is explained in Levenson, Montefiore. Although they shared common personnel, I refer to the complex here as “Einstein,” Lincoln's affiliate.

- 40. Although he was not a member of Health/PAC, medical student Peter Schnall's 1968 disruption of the American Medical Association (AMA) convention in fact marked one of the last major offenses from the New York City radicals against the AMA and a turn toward liberal targets.

- 41. “The Trouble With Empires” (editorial), Health/PAC Bulletin (April 1969): 1–3. Most of this issue is devoted to Einstein. See also Robb Burlage, “Empire Survey (II): Einstein-Montefiore: Bronxmanship,” Health/PAC Bulletin (April 1969): 3–12.

- 42. “Why the [sic] Einstein Needs Lincoln Hospital,” January 29, 1970, in personal papers of Michael McGarvey.

- 43. “Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Lincoln Hospital,” circa 1970, in personal papers of Michael McGarvey.

- 44. Ibid.

- 45. For a thorough introduction to the Young Lords, see Johanna Fernández, “The Young Lords and the Postwar City: Notes on the Geographical and Structural Reconfigurations of Contemporary Urban Life,” in African American Urban History Since World War II, ed. Kenneth L. Kusmer and Joe William Trotter (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), which also analyzes the Lincoln events but from the vantage point of the group.

- 46. “Demands of the Young Lords, Think Lincoln Committee & Health Revolutionary Unity Movement,” July 14, 1970, in personal papers of Michael McGarvey.

- 47. “Purposes of a Program in Community Pediatrics at Lincoln Hospital,” September 11, 1969, Part II (subject files), Box E-1, “Lincoln Hospital/HRUM” folder, Health/PAC papers; “Albert Einstein College of Medicine Lincoln Hospital House Officer Program in Community Pediatrics,” circa 1970, Part II (subject files), Box E-1, “Lincoln Hospital/HRUM” folder, Health/PAC papers; “Lincoln Hospital—Albert Einstein College of Medicine House Officer Program 1972–73,” in personal papers of Michael McGarvey. See also Fitzhugh Mullan, White Coat, Clenched Fist (New York: Macmillan, 1976), a memoir of one Lincoln resident's experience in these events. My summary here is a greatly compressed version of Lincoln events, which I will explore further in a separate future article.

- 48. “The Trouble with Empires,” 1. See also Maxine Kenny, “Taking Care of Their Own,” Health/PAC Bulletin (April 1969): 13.

- 49. Barbara Ehrenreich, “Bronx Community Wants Control,” Health/PAC Bulletin (September 1970): 12–16.

- 50. “Bronx Conflict Focused on Community Control,” Medical Tribune and Medical News, April 21, 1969, in Lincoln Hospital file, Institute for Social Medicine and Community Health, Philadelphia, PA.

- 51. I borrow this distinction between short-term mobilizing and long-term organizing from Charles Payne, I've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995)

- 52. Susan Reverby and Marsha Handelman, “Institutional Organizing,” Health/PAC Bulletin (January 1972): 7.

- 53. Ibid., 16.

- 54. Ibid., 1, 16.

- 55. Helen Rodriguez-Trias, “The Medical Staff and the Hospital,” Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 48 (1972): 1423–1427, and Lawrence Weed, Medical Records, Medical Education, and Patient Care: The Problem-Oriented Record as a Basic Tool (Cleveland: Case Western Reserve University Press, 1969). Peter Savage, “Problem Oriented Medical Records,” British Medical Journal 322 (2001): 275, retrospectively discusses Weed's innovation.

- 56. “Report to Workers, Nurses, Doctors, and Patients on the Evaluation of Doctors,” circa 1972, in personal papers of Harold Osborn; Helen Rodriguez-Trias to All Pediatric Staff, memorandum, June 4, 1973, Box 3, Folder 5, Papers of Fitzhugh Mullan, Wisconsin Historical Society (hereafter referred to as Mullan papers)

- 57. “Collective Meeting Minutes,” May 16, 1972, Box 2, Folder 1, Mullan papers.

- 58. “Collective Meeting Minutes,” February 7, 1972, Box 2, Folder 1, Mullan papers.

- 59. Peter Schnall and Allen Ross to J. C. Galarce, April 2, 1973, in personal papers of Harold Osborn; “Bathrooms Unsanitary: Who's to Blame?” July 1974, Part II (subject files), Box E-1, “Lincoln Hospital/HRUM” folder, Health/PAC papers.

- 60. Max Seigel, “Lincoln Hospital Stripped of Accreditation by Panel,” New York Times (September 13, 1974): 41.

- 61. Joan Solomon, “The Hospital,” The Sciences 12 (November 1972): 21–27.

- 62. Joshua Freeman, Working-Class New York: Life and Labor Since World War II (New York: New Press, 2000), chapter 15; Katz, In the Shadow of the Poorhouse, 290–292; William K. Tabb, The Long Default: New York City and the Urban Fiscal Crisis (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1982); Roger Alcaly and David Mermelstein, ed., The Fiscal Crisis of American Cities: Essays on the Political Economy of Urban America With Special Reference to New York (New York: Vintage Books, 1977)

- 63. Charles Brecher, “Historical Evolution of HHC,” in Public Hospital Systems in New York and Paris, ed. Victor Rodwin, Charles Brecher, Dominique Jolly, and Raymond J. Baxter (New York: New York University Press, 1992), 71; Brecher et al., Power Failure, 333–335.

- 64. This is a contradiction best seen with a retrospective reading of Richard Cloward and Frances Fox Piven, The Politics of Turmoil: Essays on Poverty, Race and the Urban Crisis (New York: Pantheon Books, 1974), especially ix–68, and Cloward and Piven, Regulating the Poor: The Functions of Public Welfare (New York: Pantheon Books, 1971)

- 65. Oliver Fein, “Speech on Com Control,” circa 1971 (author's estimate from context), Part I, Box 3, “CC from Oli's File” folder, Health/PAC papers.

- 66. Thomas Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North (New York: Random House, 2008), 471–477. For a liberal defense of community control of the time that simultaneously underscores the idea's limits, see Alan Altshuler, Community Control: The Black Demand for Participation in Large American Cities (Indianapolis: Pegasus, 1970). On the transition away from confrontational tactics and the impact of the fiscal crisis on the welfare rights movement, see Felicia Kornbluh, The Battle for Welfare Rights: Politics and Poverty in Modern America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), 88–113, 181–182. Stanley Aronowitz, “The Dialectics of Community Control,” Social Policy 1 (1970): 47–51, remains a masterful examination of community control's ambiguous political ramifications.

- 67. Howard Levy and Ronda Kotelchuck, “MCHR: An Organization in Search of an Identity,” Health/PAC Bulletin (March–April 1975): 1–29. [PubMed]

- 68. Ibid., 22.

- 69. I borrow the term “political synecdoche” from Adolph Reed, “The ‘Color Line’ Then and Now,” in Renewing Black Intellectual History: The Ideological and Material Foundations of African American Thought, ed. Adolph Reed and Kenneth W. Warren (Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers, 2010), 253–254.

- 70. Ronda Kotelchuck to staff, circa 1976, Part I, Box 18, “HPAC STAFF MTGS” folder, Health/PAC papers.

- 71. Health/PAC meeting minutes, September 22, 1976, October 15, 1976, April 19, 1977, and May 27, 1977, Part I, Box 18, “HPAC STAFF MTGS” folder, Health/PAC papers.

- 72. Health/PAC meeting minutes, September 22, 1976, and February 8, 1977, Part I, Box 18, “HPAC STAFF MTGS” folder, Health/PAC papers. The pressures of everyday demands and their political ramifications are explored fruitfully by Rebecca Klatch, A Generation Divided: The New Left, the New Right, and the 1960s (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), chapter 9.

- 73. Health/PAC meeting minutes, September 22, 1976, October 15, 1976, October 19, 1976, October 29, 1976, April 12, 1977, May 24, 1977, and July 11, 1977, Part I, Box 18, “HPAC STAFF MTGS” folder, Health/PAC papers.

- 74. “Health/PAC Budget (Summary of Projected Income & Expenses, July 1, 1977–June 30, 1978),” June 1977, and “Health Policy Advisory Center Summary Balance Sheet as of July 1, 1977,” June 1977, Part I, Box 18, “HPAC STAFF MTGS” folder, Health/PAC papers.

- 75. “The BULLETIN is Changing!” Health/PAC Bulletin (January/February 1978): 2; “Topics for discussion for 8/17/77 meeting,” August 17, 1977, Part I, Box 18, “HPAC-Special Interest” folder, Health/PAC papers.

- 76. Fortune magazine, of all places, used the term in a special issue on health care in January 1970.

- 77. Barbara Ehrenreich and John Ehrenreich, “Health for Profit: The Big Business of Health,” Health/PAC Bulletin (November 1969): 2.

- 78. “The Medical Industrial Complex” (editorial), Health/PAC Bulletin (November 1969): 1–2.

- 79. Ibid.

- 80. The relationship among these programs, medical cost inflation, and the growth of the private medical sector is too complicated to explore here, but Engel, Poor People's Medicine; Jonathan Oberlander, The Political Life of Medicare (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2003); Colin Gordon, Dead on Arrival: The Politics of Health Care in Twentieth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004), chapter 6; Stevens, In Sickness and in Wealth, 286–305; Eli Ginzberg, From Health Dollars to Health Services: New York City, 1965–1985 (Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Allanheld, 1986), chapter 2, are useful starting points.

- 81. Ehrenreich and Ehrenreich, “Health for Profit,” 2.

- 82. “The Great Leap Sideways” (editorial), Health/PAC Bulletin (January 1970): 1–2.

- 83. Oliver Fein, “National Health Insurance: American Dream or Scheme,” Health/PAC Bulletin (January 1970), 5.

- 84. “The Great Leap Sideways,” 2.

- 85. Ehrenreich and Ehrenreich, American Health Empire, 7.

- 86. Ibid., 11.

- 87. This phrase, or ones like it, was frequently used in the 1960s and earlier to describe patients studied by medical students, interns, and residents.

- 88. Ehrenreich and Ehrenreich, American Health Empire, 17.

- 89. Ibid., 21, 23, 25.

- 90. Ibid., 26.

- 91. For a more recent analysis of these forces, particularly racism in urban planning and fire policy, during this time period that includes discussion of the South Bronx, see Deborah Wallace and Rodrick Wallace, A Plague on Your Houses: How New York Was Burned Down and National Public Health Crumbled (New York: Verso, 1998)

- 92. See, for example, Marcia Angell, The Truth About The Drug Companies: How They Deceive Us and What to Do About It (New York: Random House, 2004)

- 93. Katz, The Undeserving Poor, 122.

- 94. See, for example, Mervyn Susser and Ezra Susser, “Choosing a Future for Epidemiology: II. From Black Box to Chinese Boxes and Eco-Epidemiology,” Am J Public Health 86 (1996): 674–677. See also Anne-Emmanuelle Birn, “Making It Politic(al): Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health,” Social Medicine 4 (2009): 166–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95. My view of gradual policy reform is thus more upbeat than the bleak assessment of Alford, Health Care Politics, although I share many of his brilliant insights on the limited and often myopic character of reforms.

- 96. Alan Derickson argues this point persuasively in Health Security for All: Dreams of Universal Health Care in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005)

- 97. Health/PAC differed from 2 other strands of health critique: one exemplified by Ivan Illich's 1970s writings, which critiqued the very content of health science itself (as opposed to its political–economic distribution and manner of administration, as Health/PAC did), and another related one anchored in individualist, “self-help” ideas that emphasized self-maintenance of personal wellness. See Ivan Illich, Medical Nemesis: The Expropriation of Health (New York: Pantheon, 1976), and, for an intellectual history of these varying strands, see David Rosner, “From Doctor Shortage to Doctor Surplus—The Shifting Debate over the Health Care ‘Crisis’ During the 1970s” (unpublished draft manuscript, 2004)