Abstract

In rod photoreceptors, signaling persists as long as rhodopsin remains catalytically active. Phosphorylation by rhodopsin kinase followed by arrestin-1 binding completely deactivates rhodopsin. Timely termination prevents excessive signaling and ensures rapid recovery. Mouse rods express arrestin-1 and rhodopsin at ~0.8:1 ratio, making arrestin-1 the second most abundant protein in the rod. The biological significance of wild type arrestin-1 expression level remains unclear. Here we investigated the effects of varying arrestin-1 expression on its intracellular distribution in dark-adapted photoreceptors, rod functional performance, recovery kinetics, and morphology. We found that rod outer segments isolated from dark-adapted animals expressing arrestin-1 at wild type or higher level contain much greater fraction of arrestin-1 than previously estimated, 15–25% of the total. The fraction of arrestin-1 residing in the OS in animals with low expression (4–12% of wild type) is much lower, 5–7% of the total. Only 4% of wild type arrestin-1 level in the outer segments was sufficient to maintain near-normal retinal morphology, whereas rapid recovery required at least ~12%. Supra-physiological arrestin-1 expression improved light sensitivity and facilitated photoresponse recovery, but was detrimental for photoreceptor health, particularly in the peripheral retina. Thus, physiological level of arrestin-1 expression in rods reflects the balance between short-term functional performance of photoreceptors and their long-term health.

Keywords: arrestin, rod photoreceptor, photoresponse, recovery, protein expression, electroretinography

Introduction

Biochemical mechanism of the response of rod photoreceptors to light faithfully served as a model of signaling cascades driven by G protein-coupled receptors (Luo et al., 2008). Light activates rhodopsin, a prototypical class A receptor, via photoisomerization of covalently attached 11-cis-retinal. Active rhodopsin catalyzes GDP/GTP exchange on a heterotrimeric G protein transducin, activating during its lifetime ~50 transducin molecules. GTP-liganded α-subunit of transducin binds γ-subunit of cGMP phosphodiesterase, activating the enzyme. Rapid drop in cGMP concentration in the OS leads to the closure of cGMP-gated cation channels. This signaling cascade has sufficient amplification to enable rods to generate a response to a single photon (Baylor et al., 1979). To maintain high temporal resolution the signaling is turned off with sub-second kinetics (Pugh and Lamb, 2000, Makino et al., 2003, Burns and Arshavsky, 2005). This is achieved by efficient mechanisms of rapid inactivation at every step of the pathway. Light-activated rhodopsin is multi-phosphorylated by a specific kinase, GRK1. When the number of rhodopsin-attached phosphates reaches a critical level of three (Mendez et al., 2000, Vishnivetskiy et al., 2007), it becomes a high-affinity target for arrestin-1a, which blocks further transducin activation by steric exclusion (Wilden, 1995, Krupnick et al., 1997). Transducin is self-inactivated due to intrinsic GTPase activity, which is greatly accelerated by RGS9 and PDEγ (reviewed in (Arshavsky et al., 2002)). Channel closure reduces the influx of Ca2+; the replacement of Ca2+ with Mg2+ converts GCAPs from inhibitors to activators of guanylyl cyclase (Peshenko and Dizhoor, 2006, Dizhoor et al., 2010), which replenishes cGMP and returns the photoreceptor to the basal state.

Rods demonstrate single photon sensitivity (Baylor et al., 1979) and high reproducibility of a single photon response (Rieke and Baylor, 1998, Burns and Arshavsky, 2005, Bisegna et al., 2008). Precise fine-tuning required for this remarkable performance involves tight control of the expression levels of each component of the signaling system (Pugh and Lamb, 2000). While the functional role of individual signaling proteins in rod phototransduction in vivo was well established using genetically modified mice (reviewed in (Makino et al., 2003)), the importance of the specific levels at which they are expressed was rarely addressed. To understand the biological role of the arrestin-1 expression level in rod photoreceptors (Strissel et al., 2006, Hanson et al., 2007b), we used transgenic lines expressing arrestin-1 at levels ranging from 4% to 220% of wild type (WT). Arrestin-1 is indispensable for the normal photoresponse recovery as well as for healthy morphology of rod photoreceptors (Xu et al., 1997). We found that the recovery kinetics and the photoreceptor morphology are affected only when the arrestin-1 expression is below 12% of WT level. However, animals expressing arrestin-1 at 125–140% of WT level demonstrate faster recovery and higher light sensitivity than WT mice. Importantly, the supra-physiological expression, while improving functional performance, is detrimental for the photoreceptor health. Rods with high arrestin-1 levels have reduced outer segment length, particularly in the peripheral retina. Thus, physiological arrestin-1 expression in rods reflects a balance between functional performance and long-term photoreceptor preservation.

Experimental Procedures

Generation of transgenic mice expressing arrestin-1 at different levels

Animal research was conducted in compliance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The coding sequence of 3A mutant with extended 5′- and 3′-UTRs followed by mp1 polyadenylation signal was placed under the control of the pRho4-1 rhodopsin promoter (Mendez et al., 2000) and used to create several transgenic lines, as described (Nair et al., 2005, Burns et al., 2006, Song et al., 2009). Transgenic lines were bred into Arr1−/−, Arr1+/−, and Arr1+/+ backgrounds. Outer segments were purified from dark-adapted animals, as described (Tsang et al., 1998). Endogenous and transgenic arrestin-1 and rhodopsin was quantified by Western blot in the homogenates of whole eyecups and outer segment preparations, using the corresponding purified proteins to construct calibration curves, as described (Chan et al., 2007, Hanson et al., 2007b, Nikonov et al., 2008, Song et al., 2009). Western blot for mitochondrial marker COX IV was used to determine the contamination of OS preparations with the IS material.

Quantitative Western blot

Aliquots of eyecup homogenates containing 0.1–0.5 ng rhodopsin or 0.3–1.2 ng arrestin-1 were subjected to SDS-PAGE along with 4–6 standards containing known amounts of the corresponding purified proteins (quantified by amino acid analysis, as described (Hanson et al., 2007b)) in the same range. Rhodopsin and arrestin-1 standards were supplemented with the same amount of protein from the retina of Rh−/− and Arr1−/− mice, respectively, that was present in experimental samples. The proteins were transferred to an Immobilon-P (Millipore) membrane, which was blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 30–60 min at 37°C with gentle rocking. The membranes were rinsed with TBST, and arrestin-1 and rhodopsin blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle rocking with polyclonal rabbit antibody (1:3,000) raised against F4C1 epitope (Donoso et al., 1990) or monoclonal 4D2 anti-rhodopsin antibody (1:3,000) (Hicks and Molday, 1986) (a generous gift from Dr. R.S. Molday) in TBST supplemented with 2% BSA. Unbound primary antibodies were removed by several washes with TBST, and the blots were incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:10,000) (Jackson Immuno), washed, and the bands were visualized with WestPico chemiluminescence reagent (Pierce) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Developed blots were exposed to SuperRX X-ray film (FujiFilm) for appropriate periods to ensure that none of the bands to be used for quantification purposes are saturated on the film. The signals were quantified using VersaDoc with QuantityOne software (BioRad), and the amount of arrestin and rhodopsin in experimental samples was calculated based on linear calibration curves using GraphPad Prizm software. Because rhodopsin always appears as a series of bands believed to represent monomers, dimers, trimers, and higher order oligomers, the sum of the signal in all rhodopsin bands in each lane was used for quantification. For rhodopsin and arrestin quantification samples containing equivalent amount of retinal protein from rhodopsin and arrestin knockout mice, respectively, was run on each blot, and the signal in corresponding areas of these “blank” lanes was subtracted from the signal in standards and all other samples. Each protein in every sample was quantified on 2–3 independent blots.

To determine the level of contamination of OS samples, aliquots of eyecup (containing 30 ng of rhodopsin) and OS homogenates (containing 150 ng of rhodopsin) were run side by side on the same SDS-PAGE gel, along with calibration samples (eyecup lysate aliquots containing 30, 20, 10, and 5 ng of rhodopsin). Western blots were developed with rabbit polyclonal antibody against mitochondrial marker COX IV (1:1,000) (#4844, Cell signaling), followed by anti-rabbit secondary antibody and WestPico, as above. The bands were quantified using VersaDoc with QuantityOne software (BioRad), and the ratio of COX IV signal in the OS preparation to that in the eyecup preparation (normalized by rhodopsin content) was used as a measure of contamination. Measured fraction of COX IV in most samples did not exceed 1%, with the highest levels detected in any OS preparation below 2%. Thus, maximum contamination (taking into account that in mouse retina about half of the mitochondria are in rod inner segments (Bentmann et al., 2005, Stone et al., 2008)) did not exceed 4% in any OS samples. Therefore, we used this level as the conservative estimate.

The analysis of retinal histology

Mice were maintained under controlled ambient illumination on a 12 hr light/dark cycle. At the age of 6–8 weeks, mice were sacrificed by overdose of isoflurane, the eyes were enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for overnight, cryoprotected with 30% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 6 hrs, and frozen at −80°C. Sections (30 μm) were cut and mounted on polylysine (0.1μg/ml) coated slides. The sections were rehydrated for 40 min in 0.1M PBS, pH 7.2 and incubated for 10 min in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100, washed twice for 5 min in PBS, and stained with NeuroTrace 500/525 green fluorescent Nissl (Invitrogen) in PBS (dilution 1:100) for 20 min. The sections were then washed with PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10min, twice with PBS (5 min each), and kept overnight at 4°C in PBS. Mounted sections were analyzed by confocal microscopy (LSM510; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The outer nuclear layer (ONL) was visualized by fluorescence in FITC (green) channel, outer segments (OS) were viewed with DIC (phase contrast). Two-channel images were acquired for quantitative analysis. Nissl stains nucleic acids, providing a convenient method of prominently labeling DNA-rich nuclei in the outer nuclear layer, and yielding characteristic more diffuse staining of RNA-rich inner segments. It also helps to identify the outer segments that are essentially free of nucleic acids and therefore contain no Nissl stain, but are clearly visible in DIC image (Fig. 2).

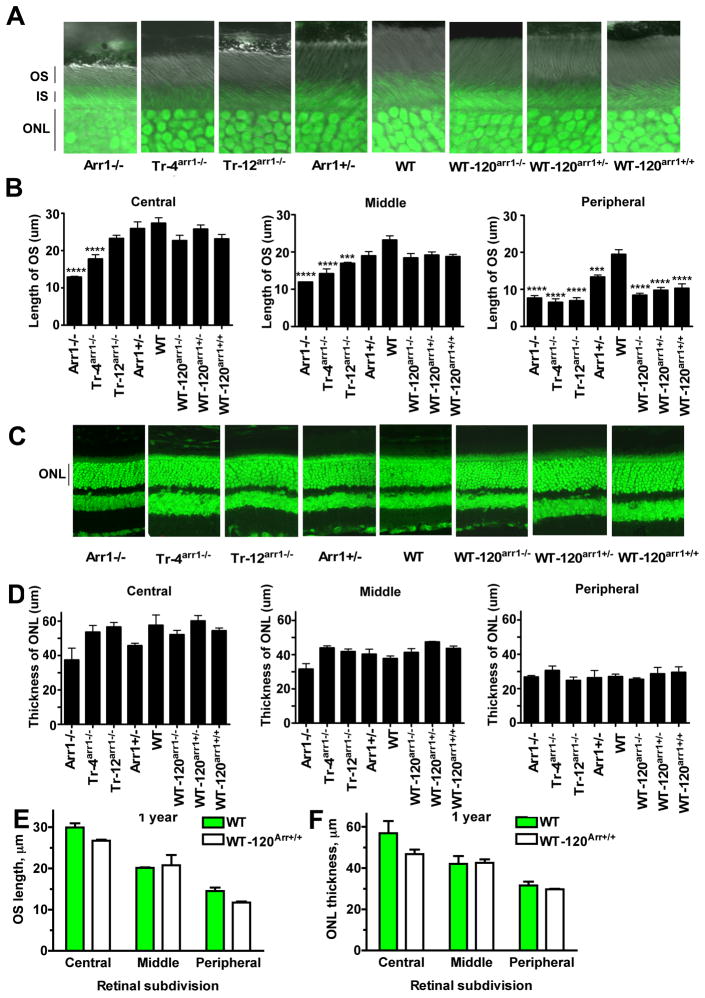

Figure 2. Arrestin expression affects the length of the outer segments, but not photoreceptor survival.

A. Combined DIC and green fluorescent Nissl images of the retina sections of 8 weeks old mice of indicated genotypes, enlarged to show OS more clearly. The positions of outer segments (OS), inner segments (IS), and outer nuclear layer (ONL) are shown on the left. B. The length of the OS measured in the Central, Middle, and Peripheral retina were the average of inferior and superior retinal hemispheres. Means +/− SE from three animals per genotype are shown. The length of OS was compared separately for each retinal subdivision by one-way ANOVA with Genotype as main factor, followed by Scheffe’s post hoc test. The effect of Genotype was significant in all retinal subdivisions (F(7,16)=15.1,11.3, 24.2, for central, middle, and peripheral retina, respectively, p<0.000)1. ***, p<0.001; **, p<0.01, as compared to WT; a – p<0.05, b – p<0.01, c – p<0.001 to Arr1-/− by Scheffe’s test. C. Confocal green fluorescent Nissl images of the ONL in central retina sections of 8 weeks old mice of indicated genotypes. D. The thickness of the ONL (reflecting the number of rod photoreceptors) measured in the Central, Middle, and Peripheral retina were the average of inferior and superior retinal hemispheres. Means +/− SE from three animals per genotype are shown. The comparison of the thickness of the ONL separately for each retinal subdivision by one-way ANOVA with Genotype as main factor revealed significant effect of Genotype for Central (F(7,26)=7.7, p<0.0001) and Middle (F(7,26)=7.1, p<0.0001) but not Peripheral retina (p=0.109). **, p<0.01, as compared to WT; a – p<0.05, b – p<0.01 to Arr1-/− according to Scheffe’s post hoc comparison. To determine whether the effects of very high arrestin-1 expression were progressive, the length of the OS (E) and the thickness of the ONL (F) were measured in12 months old WT and WT-120Arr1+/+ mice and compared to corresponding measurements at 8 weeks shown in panels B and D. E. OS length was analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA with Genotype and Age as main factors, and retinal subdivision (central, middle, and peripheral) as repeated measure factor. The effect of Genotype was highly significant (F(1,12)=17.148; p=0.0061), whereas the effect of Age was not (F(1,12)=0.876; p=0.3854). The differences among retinal subdivisions were also highly significant (F(2,12)=154.84; p<0.0001). F. The thickness of the ONL in 8 weeks and 12 months old WT and WT-120arr1+/+ mice was analyzed, as in E. No significant effects of Genotype or Age were detected, whereas the differences among retinal subdivisions were highly significant (F(2,12)=74.755; p<0.0001).

The length of OS and the thickness of ONL were measured using IPLab Version 3.9.2 (Scanalytics, Inc). The retinas of at least three mice (three sections per mouse) for each genotype were used. Each side of the section was divided into three segments according to the distance from optical nerve: central, medium, and peripheral in both inferior and superior hemispheres, so that the whole length of the section was divided into six segments. The measurements were performed at five points spaced an equal distances within each segment. Average values of each parameter for individual animals was used to calculate the mean and SD for each genotype.

Electroretinography (ERG)

Electroretinograms were recorded from 6–7 week old mice reared in 12/12 light-dark cycle (90±10 lux in the cage during light period) and dark-adapted overnight, as described (Lyubarsky et al., 2002, Song et al., 2009). Under a dim red light, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of (in μg/g body weight) 15–20 ketamine, 6–8 xylazin, 600–800 urethane in PBS. The pupils were dilated with 1% tropicamide in PBS. An eye electrode made with a coiled, 0.2 mm platinum wire was placed on the cornea, a tungsten needle reference electrode in the cheek, and ground needle electrode in the tail. ERGs were recorded with the universal testing and electrophysiologic system UTAS E-3000 (LKC Technologies, Inc.). A Ganzfeld chamber was used to produce brief (from 20μs to 1ms) full field flash stimuli. The light intensity was calibrated by the manufacturer and computer controlled. The mouse was placed on a heating pad connected to a temperature control unit to maintain the temperature at 37–38°C throughout the experiment.

Single-flash protocol

A series of stimuli from 0.00025 to 138 cd*s/m2 (or −3.6 to 2.15 log cd*s/m2, covering the range of 5.75 log units) for mice on Arr−/− background, 0.00154 to 3.7 cd*s/m2 (−2.81 to 0.57 log cd*s/m2, about 3.4 log units) for mice on Arr−/−RK−/− background, in steps of 0.2 log units was presented in an ascending order. Sufficient time interval between flashes (from 20 sec for low intensity flashes up to 3 min for the highest intensity) was allowed for dark adaptation. To increase precision, the responses to dim flashes were recorded two-three times. The a-wave amplitude was measured from baseline to the a-wave trough, and the b-wave amplitude was measured from the a-wave trough to the b-wave peak. The retinal response from rods is called the scotopic ERG, which has no discernible a-wave and a slow b-wave. The scotopic b-wave amplitude evoked the dimmest flashes, 0.00025 to 0.00964 cd*s/m2 or −3.6 to −2 log cd*s/m2, which corresponds to 0.25–10 photoisomerizations per rod (see (Lyubarsky et al., 2004) for details) was plotted versus the flash intensity, and fitted with a “Naka-Rushton” equation, hyperbolic saturation function bpeak/bmax=I/(I+I1/2) (Fulton and Rushton, 1978, Hood and Birch, 1992). Two parameters, maximal (saturation) scotopic b- wave (bmax) and the flash intensity that yields half-maximum amplitude (I1/2) were calculated using GraphPadPrism Version 4.0.

Double-flash protocol

The double-flash recording was used to analyze the kinetics of recovery (Lyubarsky and Pugh, 1996). A test flash was delivered to suppress the circulating current of the rod photoreceptors. The recovery of this current was monitored by delivering a second (probe) flash. The time interval between the two flashes was varied from 200 to 10,000 ms. The intensity of the test and probe flash was −0.4 and 0.65 log cd*s/m2, respectively, corresponding to ~400 and ~4,500 photoisomerizations per rod (Lyubarsky et al., 2004). Sufficient time for dark adaptation was allowed between trials, as determined by the reproducibility of the response to the test flash. Time-to-peak (implicit time) of the a-wave at the intensity of the probe flash was similar across different genotypes. This finding along with the shape of a-wave indicates that b-wave intrusion and oscillation potentials (Pepperberg et al., 1997, Hetling and Pepperberg, 1999) did not differentially affect different genotypes. The normalized amplitude of the probe flash a-wave was plotted as a function of time between the two flashes. Instead of fitting the data points to a theoretical equation, which is based on certain assumptions that may not be correct for all of the genotypes used in this study, we fitted curves with polynomial nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism (Version 4.0), and considered R2>0.95 as a criterion for a good fit. The time interval necessary for half recovery was calculated (Fig. 4, Table 1).

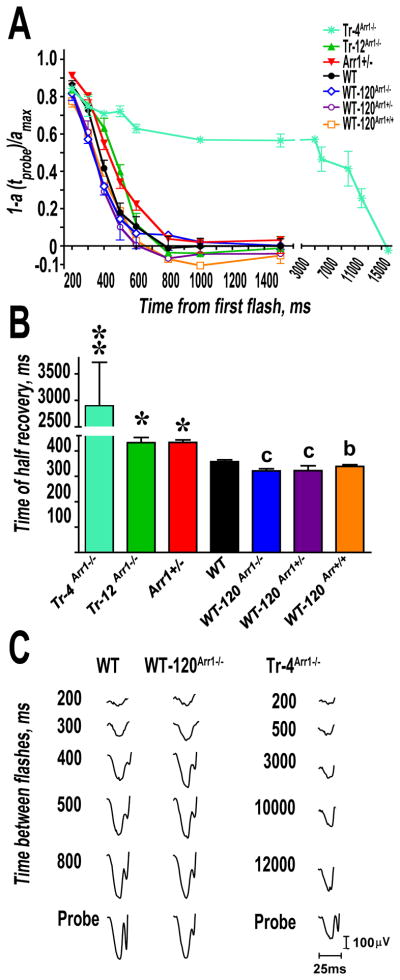

Figure 4. Reduced arrestin-1 expression slows down photoresponse recovery.

The intensities of the first (desensitizing) and second (probe) flash were 0.4 and 0.65 log cd*s/m2, respectively. A. The normalized amplitude of the probe flash a-wave was plotted as a function of time elapsed after the first flash. The interval between two flashes was varied from 200 to 1,500 ms. To calculate the time of half recovery, recovery kinetics were fitted by polynomial nonlinear regression, with R2>0.95, as described in methods. B. Calculated time of half recovery. Means +/− SD for five animals per genotype are shown. The parameters of much slower recovery of Tr-4Arr1−/− are shown in Table 1 and Supplemental Table S1. The data for other genotypes were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Genotype as a main factor, which was highly significant (F(5,24)=15.697; p<0.0001). *, p<0.05, as compared to WT; b – p<0.01, c – p<0.001 to Arr1+/− and Tr-12Arr1−/−. C. Representative traces of probe responses of WT, the fastest WT-120Arr1−/−, and the slowest Tr-4Arr1−/− mice are shown.

Table 1.

Arrestin expression, morphology and functional performance of rod photoreceptors expressing different levels of arrestin-1.

| Genotype | Arr expression | Rod Morphology | Light sensitivity (I1/2, log cd* s/m2) | Time of half recovery (thalf, ms) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ROS | ONL (μm) Middle | OS (μm) Middle | ||||||

| Arr/Rh Molar ratio | % of WT | Arr/Rh Molar ratio | % of WT | % of Total | |||||

| WT | 0.862 ±0.095 | 100% | 0.133 ±0.016 | 100 % | 15% | 37.707 ±1.553 | 23.222 ±1.126 | −2.920 ±0.071 | 376.033 ±19.184 |

| Arr1±/− | 0.462 ±0.054 | 54% | 0.088 ±0.010 | 66% | 19% | 40.269 ±2.937 | 18.973 ±1.151a | −3.262 ±0.063* | 426.332 ±10.706* |

| WT- 120arr1−/− | 1.067 ±0.070 | 124% | 0.258 ±0.007 | 194 % | 24% | 41.326 ±2.207 | 18.419 ±1.166a | −3.255 ±0.181* | 323.383 ±9.650c |

| WT- 120arr1±/− | 1.202 ±0.052 | 139% | 0.297 ±0.054 | 224 % | 25% | 47.429 ±0.302b | 19.172 ±0.851a | −3.189 ±0.103* | 330.033 ±17.316c |

| WT- 120arr1±/± | 1.877 ±0.071 | 218% | 0.341 ±0.042 | 256 % | 18% | 43.627 ±1.402a | 18.765 ±0.607a | −2.907 ±0.098 | 352.567 ±18.501b |

| Tr-12arr1−/− | 0.102 ±0.043 | 12% | 0.005 ±0.001 | 4% | 5% | 41.792 ±1.527 | 16.955 ±1.289* | −2.817 ±0.081 | 432.675 ±26.162* |

| Tr-4arr1−/− | 0.036 ±0.005 | 4% | 0.003 ±0.001 | 2% | 7% | 43.946 ±1.185a | 14.200 ±1.252** | −2.993 ±0.097 | 2642.9± 1517.0** |

The significance levels are indicated, as follows. ONL and OS:

p<0.01;

p<0.05, as compared to WT;

p<0.05;

p<0.01, as compared to Arr1−/−; light sensitivity:

p<0.05, as compared to WT; time of half recovery:

p<0.01 to all genotypes;

p<0.05, as compared to WT;

p<0.01,

p<0.001, as compared to Arr1+/− and Tr-12Arr1−/−.

Statistical analysis

For histological data, repeated measures ANOVA with Retinal Subdivision (central, middle, peripheral) as within group factor and Genotype as between group factors was used. The ANOVA analysis was followed by Scheffe post hoc test with correction for multiple comparisons.

For the a- and b-wave amplitude, repeated measures ANOVA with Genotype as the main factor and light intensity steps as repeated measures, was used. Response parameters (scotopic bmax, light sensitivity (I1/2), and time of half recovery) were analyzed by ANOVA with Genotype as the main factor followed by Scheffe post hoc test.

Results

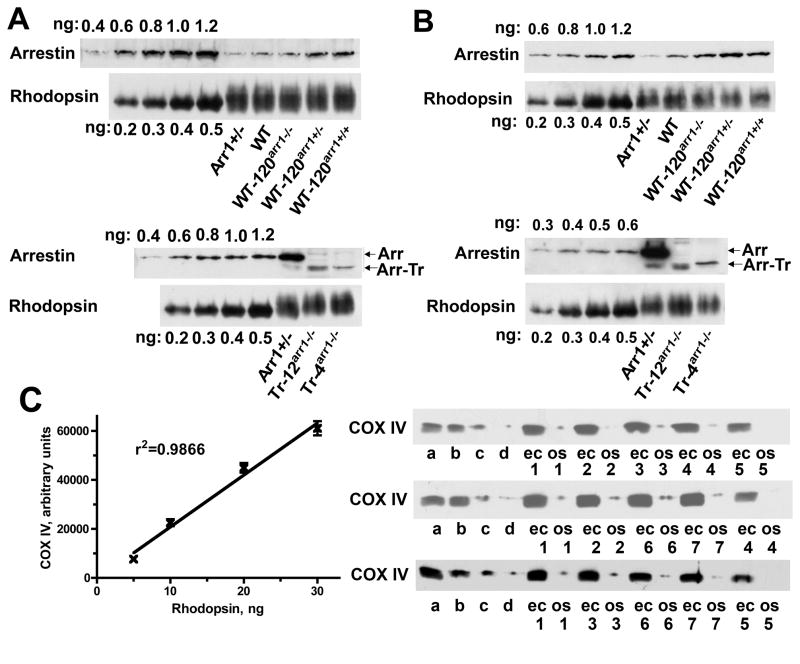

Arrestin-1 expression level affects its subcellular distribution in dark-adapted rods

In WT animals arrestin-1 is the second most abundant protein in rods, present at ~ 0.8:1 molar ratio to rhodopsin (Strissel et al., 2006, Hanson et al., 2007b). To evaluate the biological significance of this expression level, we generated several transgenic lines and measured arrestin-1 and rhodopsin in the homogenates of whole eyecups by quantitative Western blot, using purified proteins to generate calibration curves (Fig. 1A, Table 1). We confirmed that Arr1+/− (Xu et al., 1997) animals express about half of the normal arrestin-1 complement (Hanson et al., 2007b, Doan et al., 2009, Gross and Burns, 2010), and found that the expression of transgenic (Burns et al., 2006) and endogenous WT arrestin-1 is near-additive, yielding ~120%, ~140%, and ~220% of normal level on Arr1−/− (WT-120arr1−/−), Arr1+/− (WT-120arr1+/−), and Arr1+/+ (WT-120arr1+/+) backgrounds, respectively. We also created two lines with very low transgenic expression of truncated arrestin-1(1–377) at 12% and 4% of WT level (Tr-12arr1−/− and Tr-4arr1−/−, respectively) (Table 1).

Figure 1. Arrestin-1 expression and levels in OS of different mouse lines.

Western blot showing the levels of arrestin-1 in the whole eyecup (A) and OS (B) in WT, Arr1+/− and different transgenic lines, with indicated amounts of corresponding purified proteins used as standards. Arrestin-1 and rhodopsin were measured by quantitative Western blot, as described (Gurevich et al., 2007, Hanson et al., 2007b) (see Methods for details). Here the amounts of rhodopsin were equalized to show the differences in arrestin-1 levels. C. To test the purity of the OS fraction and the extent of contamination with inner segment material, aliquots of eyecup (ec, containing 30 ng of rhodopsin) and OS (os, containing 150 ng of rhodopsin) homogenates from mice with indicated genotypes were run side by side along with calibration samples on SDS-PAGE gel. Western blots were developed with rabbit polyclonal antibody against mitochondrial marker COX IV. Aliquots of WT eyecup homogenate containing 30, 20, 10, and 5 ng of rhodopsin were used as calibration samples (a, b, c, and d, respectively). Representative calibration curve is shown on the left. Only blots where calibration curve showed r2>0.95 were used. Blots of representative samples (out of three per genotype used) are shown on the right. Genotypes are indicated, as follows: 1, WT; 2, Arr1+/−; 3, WT-120Arr1−/−; 4, WT-120Arr1+/−; 5, WT-120Arr1+/+; 6, Tr- 12 Arr1−/−; 7, Tr-4Arr1−/−.

Arrestin-1 undergoes robust light-dependent translocation, localizing to the OS in the light, whereas in dark-adapted rods it is predominantly detected in the inner segment (IS), perinuclear area, and synaptic terminals (Broekhuyse et al., 1985, Philp et al., 1987, Whelan and McGinnis, 1988). Arrestin-1 binding to P-Rh* necessary for the effective photoresponse shutoff (Chen et al., 1995, Xu et al., 1997, Chen et al., 1999a, Mendez et al., 2000) occurs within 150 ms after the flash (Xu et al., 1997) or even faster (Krispel et al., 2006, Burns and Pugh, 2009, Gross and Burns, 2010), whereas arrestin-1 translocation to the OS happens on the time scale of many minutes (Elias et al., 2004, Nair et al., 2005, Strissel et al., 2006). Thus, arrestin-1 already present in the OS is responsible for the termination of the photoresponse of dark-adapted rods. The estimates of the fraction of arrestin-1 in the OS of WT mice vary widely, from 2 to 9 % of the total (Nair et al., 2005, Strissel et al., 2006, Hanson et al., 2007b), largely due to inherent limitations of the methods used: semi-quantitative nature of immunohistochemistry (Nair et al., 2005, Hanson et al., 2007b) and insufficient amount of material generated by tangential sectioning of small mouse retinas (Strissel et al., 2006). The concentration of arrestin-1 in the OS of dark-adapted rods is a very important functional parameter. Therefore, we quantified it using another method: by isolation of dark-adapted mouse OS (Fig. 1B) and comparison of the arrestin-1 content in the OS and whole eyecups (Table 1). To minimize the effect of unavoidable sample-to-sample variability of yields, arrestin-1:rhodopsin ratios were calculated in both cases. In WT eyecups, this ratio was found to be 0.86±09, which is within experimental error of previous measurements (Strissel et al., 2006, Hanson et al., 2007b). In the OS of WT mice, this ratio was 0.133±0.016, indicating that 15% of arrestin-1 localizes to this compartment. This number is significantly higher than previous estimates. Since adjacent inner segments (IS) appear to contain a large proportion of arrestin-1 in the dark (Broekhuyse et al., 1985, Whelan and McGinnis, 1988, Nair et al., 2005, Strissel et al., 2006), we evaluated the level of contamination of the OS fractions. The IS are particularly rich in mitochondria that are absent in the OS (Sokolov et al., 2002). Therefore we used subunit IV of the cytochrome C oxidase (COX IV), localized to the inner membrane of the mitochondria, as IS marker. Quantitative Western blot for COX IV of eyecup and OS samples showed minimal contamination, with less than 2% total retinal COX IV present in the OS fraction (less than 1% in most samples) (Fig. 1C). While in avascular retinas (e.g., in guinea pig) virtually all mitochondria are localized to the IS, in the vascular retina of mouse (as well as rat and human) mitochondria are also present near synaptic terminals (outer and inner plexiform layers), and in the ganglion cell layer, so that IS contains about half of retinal mitochondria (Bentmann et al., 2005, Stone et al., 2008). Thus, the upper limit of 2% COX IV suggests that no more than 4% of the IS material is present in the OS fraction. However, this estimate is based on the assumption that the same fraction of COX IV and arrestin-1 present in contaminating IS fragments survives OS purification procedure. Although this assumption cannot be tested directly, which is the main caveat of our method, one needs to consider that COX IV resides in the inner membrane of mitochondria and can only be lost along with these organelles. In contrast, arrestin-1 is a soluble protein with no lipid modifications, which in the IS is largely bound to microtubules (Nair et al., 2005). Arrestin-1 affinity for microtubules is very low (KD > 50 μM, see (Hanson et al., 2006)), making the dissociation rate very rapid (Gurevich et al., 2007). Therefore, in the process of OS purification contaminating IS fragments will likely loose significantly larger fraction of weakly bound arrestin-1 than of COX IV. Thus, the error introduced by the use of COX IV as IS contamination marker leads to overestimation of the fraction of arrestin-1 coming from contaminating IS. Moreover, only ~60% of arrestin-1 resides in the IS of dark-adapted rods (Strissel et al., 2006). Thus, even after the most conservative correction for contamination (likely resulting in underestimation of arrestin-1 content in the OS), more than 12% of the total arrestin-1 is present in the OS in the dark, which translates into ~300 μM (assuming rhodopsin concentration in the OS of ~3 mM (Pugh and Lamb, 2000)), or one arrestin-1 molecule per ten rhodopsins. Interestingly, this is very similar to the reported arrestin-1/rhodopsin ratio in dark-adapted frog OS (Hamm and Bownds, 1986), suggesting that this ratio is conserved among vertebrates, even though frog OS are much bigger than mouse OS, contain many times more rhodopsin molecules, and account for much larger proportion of the total rod volume.

In agreement with previous reports (Xu et al., 1997, Hanson et al., 2007b, Doan et al., 2009, Gross and Burns, 2010), we found that Arr1+/− animals express about half of WT complement of arrestin-1. This translates into roughly proportional reduction of arrestin-1 content in the OS (Table 1). WT-120arr1−/−, WT-120arr1+/−, and WT-120arr1+/+ mice express arrestin-1 at 120%, 140%, and 220% of WT level, respectively (Fig. 1, Table 1). This results in a significant increase in OS arrestin-1 content. Interestingly, the increase is somewhat greater than proportional (18–25% of the total), so that arrestin-1 in the OS in these lines reaches 190%, 220%, and 260% of WT levels, which translates into one arrestin-1 per 3–4 rhodopsin molecules. Since in the dark arrestin-1 is sequestered by microtubules (Nair et al., 2005), predominantly localizing to the IS and other microtubule-rich compartments (Eckmiller, 2000), its greater fractional localization to the OS may reflect higher level of microtubule saturation. This notion is consistent with our finding that in Tr-12arr1−/− and Tr-4arr1−/− mice expressing arrestin-1 at very low levels, arrestin-1 fraction in the OS is much lower, 5–7% of the total (Fig. 1, Table 1). To test for possible contribution of higher affinity of the truncated mutant for microtubules (Nair et al., 2005, Hanson et al., 2007a), we measured OS content of arrestin-3A mutant, with the same microtubule affinity as truncated form (Nair et al., 2005), in transgenic line 3A-240arr1−/− (Song et al., 2009) that expresses it 220% of WT level, similar to WT in WT-120arr1+/+ line. The fraction of arrestin-1 in the OS in this line was found to be 25±2%, i.e., comparable to that in WT-120arr1+/+ and WT-120arr1+/− mice (Table 1), demonstrating virtually equal retention in the IS of WT and mutant arrestin-1.

Collectively, these mouse lines cover wide range of arrestin-1 expression from 4% to 220% of WT, with OS concentrations differing by ~130-fold, from 2% to 256% of WT level, setting the stage for the analysis of the biological role of arrestin-1 level in rod photoreceptors.

Arrestin-1 expression alters the length of OS more significantly than photoreceptor survival

To assess the effect of arrestin-1 expression level on rod photoreceptors, we analyzed retinal morphology in all mouse lines. To this end, we measured the length of the OS, which reflects rod health and photostasis, and the thickness of the outer nuclear layer (ONL), which reflects photoreceptor survival. In Arr1−/− mice, excessive rhodopsin signaling induces rapid dramatic shortening of the OS, and eventual photoreceptor death (thinning of the ONL) (Xu et al., 1997, Chen et al., 1999b, Song et al., 2009). To obtain a comprehensive picture, we measured both parameters in three areas: central, middle, and peripheral retina (Fig. 2). Arrestin-1 levels have profound non-linear effects on the length of the OS. The OS in Arr1−/− and Tr-4arr1−/− animals were significantly shorter than WT across retinal subdivisions. The Tr-12arr1−/− line had shorter OS than WT in the middle and peripheral retina, and in these retinal subdivisions neither of the low expressing lines was significantly different from Arr1−/− mice. However, in the central retina, the Tr-12arr1−/− line had longer OS than Arr1−/− mice (not significantly different from that in WT). The Tr-4arr1−/− line, although different from WT, was not significantly different from either Arr1−/− or Tr-12arr1−/− suggesting that its OS length values were actually in between the values for these two lines. The high expressing lines (WT-120Arr1+/− and WT-120Arr1+/+) had normal OS lengths in the central and middle retina, but significantly shorter OS in the peripheral retina (Fig. 2A,B). Overall, the peripheral retina turned out to be the most sensitive to arrestin-1 level: all genotypes had shorter OS than WT, with Arr1+/− being the second best (Fig. 2A,B). Thus, normal WT arrestin-1 level is within a fairly narrow optimum for OS maintenance, and ~50% reduction or even modest ~25% increase of arrestin-1 adversely affect the OS. However, even >2-fold higher arrestin-1 level in WT-120Arr1+/+ does not lead to progressive photoreceptor damage: the difference between this line and WT remains essentially the same at 12 months (Fig. 2E,F).

Interestingly, we found that in the normal light-dark cycle mice expressing arrestin-1 at various levels, from as low as 4% (Tr-4Arr1−/−) to as high as 220% (WT-120Arr1+/+), demonstrate normal ONL thickness indistinguishable from WT, whereas mice lacking arrestin-1 (Arr1−/−) have significantly thinner ONL than WT in the central and middle retina, indicative of photoreceptor loss (Figs. 2C,D,F). Thus, even very low expression of arrestin-1 ensures better photoreceptor survival than in Arr1−/− mice, and high supra-physiological levels do not induce photoreceptor death.

The effect of arrestin-1 expression level on functional performance of rod photoreceptors

The retinal function can be monitored non-invasively by electroretinography (ERG). Mouse ERG is dominated by the responses of rods, where the suppression of rod circulating current is reflected in the negative a-wave (Lyubarsky and Pugh, 1996, Hetling and Pepperberg, 1999), whereas the positive b-wave is largely generated by the response of rod bipolar cells (Robson and Frishman, 1995, Robson and Frishman, 1999) (reviewed in (Pugh et al., 1998)). To determine the effect of the arrestin-1 expression level on rod function we analyzed the amplitude of a-wave and b-wave at different flash strengths (Fig. 3).

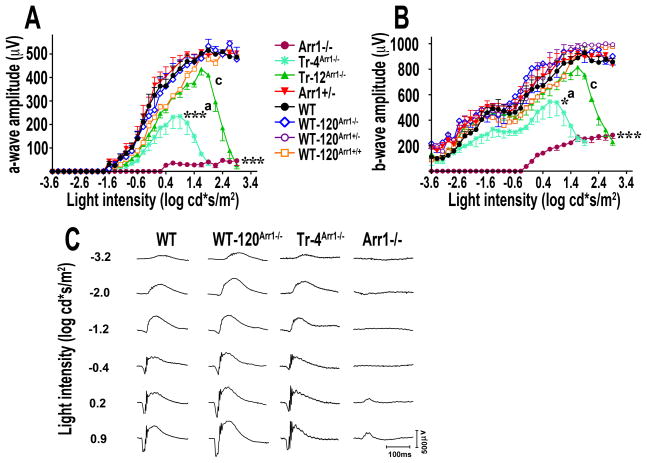

Figure 3. The role of arrestin-1 expression in functional performance of rod photoreceptors.

Single-flash ERG responses of increasing intensity for mice of indicated genotypes were recorded, as described in Methods. The a-wave (A) and b-wave (B) amplitudes were plotted as a function of light intensity. Means +/− SE from three animals per genotype are shown. The responses of higher expressors were not different from WT. Data analysis by Repeated Measures ANOVA (with light intensities as repeated measures) with Genotype as main factor revealed highly significant effect of arrestin-1 concentration at levels below WT on a-wave amplitude (F(4,160)=44.9; p<0.0001). ***, p<0.001, * − p<0.05 as compared to WT and Arr1+/−; a – p<0.05, c – p<0.001 as compared to Arr1−/− according to Scheffe’s post hoc comparison. C. Representative traces of single-flash responses of WT, WT-120Arr1−/−, Tr-4Arr1−/−, and Arr1−/− mice are shown to illustrate a dramatic improvement over Arr1−/− rods achieved even at very low arrestin-1 expression.

ERG a- and b-wave responses in WT mice increase robustly with the increasing intensities of single flashes. In contrast, as reported previously (Lyubarsky et al., 2002, Song et al., 2009), Arr1 knockout mice demonstrated no rod-dependent responses, and no a-wave was registered until flashes reached high intensity (Fig. 3A). In lower expressing lines (WT and lower), the concentration of arrestin-1 significantly affected the amplitude of the a-wave response (F(4,160)=44.86; p<0.0001). There was also a strong Genotype x Flash Intensity interaction (F(4,160)=30.2, p<0.0001) reflecting that the divergence between WT and lower expressing lines increased with light intensity (Fig. 3A).Tr-4Arr1−/− demonstrated lower a-wave amplitude than WT (p=0.0009), Arr1+/− (p=0.0005), or even Tr-12Arr1−/− (p=0.044), but higher than that in the Arr1−/− mice (p=0.046). Interestingly, animals that expressed as little as 12% of the normal arrestin-1 complement (Tr-12Arr1−/−) were not significantly different from WT or Arr1+/− mice but were very different from Arr1−/− animals (p=0.0004). The responses of mice with higher than normal levels of Arr1 (WT-120Arr1−/−, WT-120Arr1+/−, and WT-120Arr1+/+) were similar to those of WT animals (Fig. 3A).

The differences in b-wave amplitudes among genotypes are not as pronounced, likely due to a much larger cone contribution (Fig. 3, compare Arr1−/− curves in panels A and B). The animals were allowed intervals between trials to return to dark-adapted state that were gradually increased from 30 to 150 s with increasing flash intensity. All lines expressing arrestin-1 responded virtually normally to dim and moderately bright stimuli, whereas brighter flashes revealed deficits in re-adaptation in low-expressing animals (the effect of Genotype for low expressing lines F(4,260)=22.79, p<0.0001) and Genotype x Flash Intensity interaction F(26,260)=13, p<0.0001)). The intensity-response curves of Tr-4Arr1−/− and Tr- 12Arr1−/− lines began to “peel off” those of other genotypes at ~0.6 and ~2 log cd*s/m2, respectively, ultimately yielding essentially cone-only responses similar to those of Arr1−/− mice (Fig. 3A,B). The transition from WT-like to Arr1−/−-like performance in Tr-12Arr1−/− and Tr-4Arr1−/− animals occurs at 2.65 and 1.9 log cd*s/m2, respectively (Fig. 3), which corresponds to ~450,000 and ~80,000 photoisomerizations/flash (Lyubarsky et al., 2004). Since each subsequent flash in the series produces twice as many photoisomerizations as the preceding one, these values reflect the number of photoisomerizations accumulated throughout all preceding flashes. The amount of arrestin-1 present in the OS of Tr-12Arr1−/− and Tr-4Arr1−/− mice is equivalent to 4% and 2% of WT (Table 1), i.e., 12 and 6 μM, respectively. Since 108 rhodopsin molecules in mouse OS create 3 mM concentration (Pugh and Lamb, 2000), these arrestin-1 concentrations translate into 400,000 and 200,000 molecules per OS, respectively, which matches the number of accumulated photoisomerizations depleting the pool of arrestin-1 fairly well. Thus, rods behave as Arr1−/− when all arrestin-1 in the OS is “consumed” via 1:1 binding (Hanson et al., 2007b, Bayburt et al., 2010) to previously bleached photopigment. These data strongly suggest that virtually all arrestin-1 in the OS is fully accessible to rhodopsin. In summary, at least 50% of WT arrestin-1 level is necessary for rapid recovery of photoreceptor responsiveness after very bright flashes. The most surprising finding, though, was how much difference even very low expression of arrestin-1 makes. Up to a fairly bright flash intensity (2.0 log cd*s/m2), Tr-12Arr1−/− responds virtually like WT and much better than Arr1−/− (p=0.0007) (Fig. 3). Even Tr-4Arr1−/−, with only 2% of the normal arrestin-1 content in the OS, is dramatically different from Arr1−/− mice (p=0.03) that only respond to bright flashes via cones. In sharp contrast to non-functional Arr1−/− rods, Tr-4Arr1−/− rods, with this minuscule amount of arrestin-1, function fairly well, even beyond scotopic (rod only) range of dim flashes (Fig. 3).

At flash intensities that do not exceed 0.00964 cd*s/m2 (−2 log cd*s/m2), or 10 photoisomerizations per rod (Lyubarsky et al., 2004), only rods can respond. As it is technically difficult to measure a-wave of very small amplitude evoked by these flashes, scotopic (rod-driven) b-wave responses are used instead to determine light sensitivity. To this end, the amplitude of scotopic b-wave as a function of flash intensity was fitted to Naka-Rushton equation (hyperbolic saturation function bpeak/bmax=I/(I+I1/2)) (Fulton and Rushton, 1978, Hood and Birch, 1992). This analysis yields two parameters, the maximum scotopic b-wave amplitude (bmax) and light intensity producing half-maximum rod b-wave (I1/2), which reflects light sensitivity (Table 1). The amplitude of scotopic b-wave in all lines expressing arrestin-1 was not significantly different from WT (data not shown). In contrast, arrestin-1 level significantly affected light sensitivity (F(6,21)=5.167; p=0.0021). Comparison of different lines shows a non-linear relationship between arrestin-1 expression level and light sensitivity. WT-120Arr1−/− animals demonstrated higher light sensitivity (lower I1/2) than WT. Both WT-120Arr1−/− and WT-120Arr1+/− lines had significantly higher light sensitivity than WT-120Arr1+/+. In contrast, light sensitivity of Tr-12Arr1−/− animals was significantly lower than Arr1+/−, WT-120Arr1−/−, and WT-120Arr1+/− animals (Table 1). Thus, moderate increase in arrestin-1 level results in an increase of light sensitivity of rod photoreceptors.

Arrestin-1 is the key player in rapid photoresponse recovery (Xu et al., 1997, Mendez et al., 2000, Burns et al., 2006, Chan et al., 2007). Therefore we compared the recovery kinetics in mice expressing wide range of arrestin-1 levels using double-flash protocol (Pepperberg et al., 1997). In this paradigm the first flash desensitizes rods, whereas the amplitude of the response to the second flash, delivered at variable intervals after the first, shows the extent of the recovery. The plot of this amplitude as a function of time interval between flashes yields halftime of recovery (thalf) (Lyubarsky and Pugh, 1996). As expected, we found that arrestin-1 expression level significantly affects the rate of recovery (F (5,24)=15.697; p<0.0001). Animals with higher arrestin-1 levels, WT, WT-120Arr1−/−, WT-120Arr1+/−, and WT-120Arr1+/+, all showed significantly faster recovery than Tr-4Arr1−/−, Tr-12Arr1−/−, and even Arr1+/− mice (Fig. 4; Table 1). The rate of recovery was dramatically reduced in Tr-4Arr1−/− mice (Fig. 4, Table 1). The comparison of the mice with below WT expression, Arr1+/−, Tr-12Arr1−/− and Tr-4Arr1−/− shows that ~four-fold reduction of arrestin-1, from ~50 to 12%, does not appreciably change thalf, whereas a further three-fold drop from 12 to 4% increases thalf ~6-fold (Table 1). These data suggest that there is a critical threshold of arrestin-1 expression required for near-normal photoresponse recovery, which is between 12 and 4% of WT level. The fact that individual variability among Tr- 12Arr1−/− animals (SD/average ~ 0.06) is comparable to that of WT (SD/average ~ 0.051) and other lines (SD/average between 0.025 and 0.052), whereas among Tr-4Arr1−/− mice variability is dramatically increased (SD/average =0.574; Table 1) indicates that at the intensity of the first (desensitizing) flash used in our experiments (−0.4 log cd*s/m2, i.e., 400 photoisomerizations per flash (Lyubarsky et al., 2004)) this threshold is close to 4% of WT level.

Based on ~ 3 mM rhodopsin in the OS (Pugh and Lamb, 2000), our measurements indicate that there is ~300 μM of arrestin-1 in the OS of dark-adapted WT rods. However, arrestin-1 robustly self-associates, forming dimers and tetramers (Schubert et al., 1999, Imamoto et al., 2003, Hanson et al., 2007c, Hanson et al., 2008), and only the monomer is an active rhodopsin-binding species (Hanson et al., 2007c). Recently measured self-association constants of mouse arrestin-1 (Kd dimer =57.5±0.6 μM; Kd tetramer = 63.1±2.6 μM; see (Kim et al., 2010)) allow one to calculate that at 300 μM arrestin-1 the concentration of the monomer is ~50 μM. The kon for diffusion-controlled protein-protein interactions is ~1×106M−1sec−1 (Northrup and Erickson, 1992). Essentially the same kon was recently measured for arrestin-1 binding to rhodopsin (Bayburt et al., 2010). The on-rate for arrestin-1 binding to rhodopsin equals the product of kon and monomer concentration (~50 μM), which is 50 sec−1. In plain English this means that arrestin-1 monomer encounters each rhodopsin molecule in the OS and “checks” its functional state 50 times per second, i.e., every 20 msec. Even at the lowest estimate of rhodopsin active lifetime of ~30 msec (Burns and Pugh, 2009, Gross and Burns, 2010) this leaves a time window for rhodopsin phosphorylation, which must occur before arrestin-1 can bind with high affinity (Mendez et al., 2000, Vishnivetskiy et al., 2007).

We observed perceptible slowing of the recovery kinetics at arrestin-1 levels at 12–50% of WT, and dramatically slowed recovery at ~4% (Fig. 4). This is unlikely to be the result of gross deficit of arrestin-1 in the OS. Even in the lowest expressor Tr-4Arr1−/− there is ~6 μM (~5 μM monomer at Kd dimer=57.5 μM) arrestin-1 in the OS, which is largely free at this concentration, considering its low affinity for the two partners engaging its receptor-binding surface, microtubules (Hanson et al., 2007a) and calmodulin (Wu et al., 2006). The arrestin-1/rhodopsin ratio in dark-adapted OS in this line is 50 times lower than in WT (Table 1), i.e., one per 500 rhodopsins. In mouse OS ~ 108 rhodopsin molecules are localized in ~800 discs at ~125×103 per disc (Pugh and Lamb, 2000). Thus, Tr-4Arr1−/− mice have ~250 arrestin-1 molecules per disc, whereas the desensitizing flash we used (−0.4 log cd*s/m2) generates only ~400 Rh* per rod (Lyubarsky et al., 2004), or ~0.5 Rh* per disc. However, when arrestin-1 monomer concentration is 1/10th of WT level, expected on-rate of its binding to rhodopsin is only 5 sec−1, which means that arrestin-1 can “check” the functional state of each rhodopsin only once in ~200 msec. This would dramatically increase active lifetime of Rh*, accounting for slow recovery (Table 1). Supra-physiological expression of arrestin-1 (124–218% of WT), which increases OS concentration 2–2.7-fold, accelerates the recovery only slightly (Table 1) for two reasons. First, due to self-association, with the increase of total OS arrestin-1 from 300 μM in WT to ~800 μM in WT-120Arr1+/+ the concentration of the monomer increases only modestly, from ~50 to ~67 μM. Second, if rhodopsin phosphorylation and arrestin-1 binding have similar time constants in WT animals (Gross and Burns, 2010), the acceleration of only one of these processes cannot dramatically speed up the recovery, which critically depends on both.

Discussion

Every cell type expresses a characteristic set of proteins, each at a certain level, which is usually tightly regulated by the rate of production and degradation. Rod photoreceptors are the only cell type where the absolute expression levels of every player in the whole signaling pathway was measured with reasonable precision (Pugh and Lamb, 2000). These data, along with internal structure and dimensions of the outer segment harboring these signaling proteins, enabled the calculation of the concentrations of the key components and quantitative spatiotemporal modeling of rod function (Pugh and Lamb, 2000, Caruso et al., 2005, Bisegna et al., 2008, Shen et al., 2010). The biological role of every signaling protein in rods was demonstrated in vivo in genetically modified mice (reviewed in (Makino et al., 2003)). The elimination of rhodopsin (Humphries et al., 1997) or transducin (Calvert et al., 2000) completely blocks light-evoked signaling, whereas knockout of GRK1 (Chen et al., 1999a), arrestin-1 (Xu et al., 1997), or the components of RGS9-Gβ5-R9AP complex that accelerates transducin GTPase (Chen et al., 2000, Krispel et al., 2003, Keresztes et al., 2004) results in prolonged exaggerated signaling that eventually leads to photoreceptor demise.

In contrast to the comprehensive set of “all-or-nothing” comparisons, the biological significance of the exact expression levels of individual signaling proteins was rarely tested. Where performed, these experiments yielded illuminating, sometimes counter-intuitive results. The reduction of rhodopsin expression by ~50% had predictable effects on photon capture, but unexpectedly accelerated both photoresponse and recovery (Calvert et al., 2001), whereas increased rhodopsin expression slowed down the response (Wen et al., 2009). Reduced expression of transducin resulted in proportional reduction in signal amplification (Krispel et al., 2007, Lobanova et al., 2008). The only study where photoreceptors with multiple levels of the same protein were compared side-by-side yielded seminal results: elevated GRK1 increased rhodopsin phosphorylation, but did not change recovery kinetics, whereas an increase in RGS9 level dose-dependently facilitated the recovery, proving that deactivation of transducin rate-limits this process (Krispel et al., 2006). In contrast, in Drosophila photoreceptors rhodopsin inactivation by arrestin dominates the rate of recovery (Dolph et al., 1993, Ranganathan and Stevens, 1995).

Functional consequences of the reduction of arrestin-1 expression so far have been tested exclusively by comparing WT (Arr1+/+) and Arr1+/− animals. In the original work, no appreciable differences in recovery kinetics were detected (Xu et al., 1997). Two recent studies using different single cell recording conditions came to opposing conclusions. In one, the recovery in rods expressing ~50% of WT arrestin-1 level was reported to accelerate (Doan et al., 2009). In another, the rate of recovery after dim flashes was slowed by the reduction of arrestin-1 level, but only when downstream deactivation was speeded up by high expression of RGS9 (Gross and Burns, 2010). The effects of arrestin-1 level on photoreceptor maintenance were never reported, and rods with supra-physiological arrestin-1 expression were not studied. Therefore, we performed a comprehensive comparison of rod morphology and functional performance in animals expressing arrestin-1 at seven different levels: WT, reduced 25-, 8-, and 2-fold, and increased to 125%, 140%, and 220% of normal.

The analysis of retinal morphology unexpectedly revealed essentially the same survival of photoreceptors expressing arrestin-1 at all non-zero levels (Fig. 2, Table 1). The length of the OS was more sensitive, but even here significant shortening was observed only in lines expressing very low levels of arrestin-1. Importantly, the OS in Tr-4Arr1−/− mice expressing only 4% of normal arrestin-1 level are still slightly longer than in Arr1−/− animals. The effect of sub-physiological levels of arrestin-1 was dose-dependent: the shortening of OS in Tr-4Arr1−/− was evident across retinal subdivisions, in Tr- 12Arr1−/− in the middle and peripheral retina, whereas in Arr1+/− mice only the periphery was affected (Fig. 2). The reduction of the a-wave in Tr-4Arr1−/− and Tr-12Arr1−/− mice (Fig. 3A) is roughly proportional to the shortening of their OS, as could be expected (Robson and Frishman, 1999). Supra-physiological expression of arrestin-1 also decreased the length of the OS, but the differences with WT reached statistical significance only in the peripheral retina (Fig. 2).

Electrophysiological studies are usually performed on dark-adapted animals and/or isolated photoreceptors, where the bulk of arrestin-1 is localized to the IS. Since protein translocation in rods is a fairly slow process and its initiation requires the bleaching of >1% of total rhodopsin (Elias et al., 2004, Nair et al., 2005, Strissel et al., 2006), arrestin-1 residing in dark-adapted OS is responsible for the photoreceptor recovery determined by electrophysiology. Because of its functional importance, several groups measured this parameter using different methods. Immunohistochemistry yielded an estimate of 2–4% of the total arrestin-1 in WT mice (Elias et al., 2004, Nair et al., 2005, Gurevich et al., 2007, Hanson et al., 2007b). However, this method is based on the assumption that epitope accessibility in all rod compartments is equal, which cannot be tested experimentally. Theoretically, tangential sectioning of the flattened retina followed by quantitative Western blot is the best possible method to determine the localization of any protein in rods. This method worked beautifully in rat (Sokolov et al., 2002), but in a much smaller mouse retina the amount of material was insufficient to measure arrestin-1 in dark-adapted OS, necessitating its indirect calculation (Strissel et al., 2006). This study yielded much higher estimate, ~9% of the total. Here we quantified arrestin-1 in isolated OS of dark-adapted mice (Tsang et al., 1998), using rhodopsin content as a measure of yield and mitochondrial marker COX IV as a measure of IS contamination. Our analysis shows that 12–16% of arrestin-1 resides in the OS of dark-adapted WT and Arr1+/− mice, with even higher proportion detected in the OS of mice with elevated expression (Table 1). The fraction in the OS drops to 5–7% of the total in animals expressing arrestin-1 at 4–12% of WT level. These changes are compatible with the idea that the equilibrium between free and microtubule-bound arestin-1 and highly uneven distribution of microtubules in rod compartments determines the fraction of arrestin-1 in the OS in the dark (Nair et al., 2005). In this model, the concentration of free cytoplasmic arrestin-1 across cellular compartments is equalized by diffusion. It follows that the abundance of empty arrestin-1 binding sites on microtubules in lower expressors would reduce the concentration of free arrestin-1 and hence its fraction residing in the OS containing very few microtubules, whereas the saturation of these sites in high expressors would increase the proportion of free arrestin-1 and therefore its fraction in the OS.

Complex dependence of light sensitivity on arrestin-1 expression level (Table 1) allows several interpretations. Light sensitivity depends on photon capture, which is determined by the size of the OS, as well as on the amplitude of the elementary response and the level of noise. Increased arrestin-1 could suppress background noise and reduce elementary response, with opposite effects on sensitivity. Conceivably, modest supra-physiological levels of arrestin-1 decrease noise to a greater extent than elementary response, with the net result of higher sensitivity. In contrast, increased noise in mice lacking arrestin-1 or GRK1 apparently outweighs increased elementary response, resulting in complete loss of rod-mediated vision (Xu et al., 1997, Chen et al., 1999a). The same phenotype, night blindness, was reported in human patients carrying these molecular defects (Fuchs et al., 1995, Yamamoto et al., 1997), with a significant reduction of light sensitivity of cones as well (Cideciyan et al., 1998). The reduction of the OS length and possibly higher noise in low expressing lines apparently counteracts expected increase in elementary response, yielding essentially WT sensitivity. Since light sensitivity is determined by ERG indirectly, via b-wave generated by bipolar cells, recent discovery that arrestin-1 positively modulates the activity of N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) in rod synaptic terminals (Huang et al., 2010) suggests yet another explanation. Enhanced NSF function in modest over-expressors could account for observed increase in sensitivity, while reduced NSF function in lines with low arrestin-1 could contribute to its reduction (Table 1).

Dramatic improvement in functional performance of rods in Tr-4Arr1−/− animals with very low arrestin-1 level, as compared to Arr1−/− mice, has important implications for recently proposed use of “enhanced” arrestin-1 with high affinity for unphosphorylated light-activated rhodopsin for gene therapy of disorders associated with defects in rhodopsin phosphorylation (Song et al., 2009). Our data suggest that fairly low expression of enhanced mutant might be sufficient for near-normal photoreceptor function in dim light and for rod survival. Since rod demise is usually followed by the loss of cones and complete blindness, the preservation of rods even in imperfect morphological and functional condition may have critical importance for the therapy of visual disorders.

Conclusions

Collectively, our data show that higher than WT arrestin-1 levels only marginally improve rod functional performance, while somewhat impairing OS maintenance. In contrast, reduced levels are adequate at dim light, but impair functional performance in response to bright flashes and slow down the recovery. Thus, physiological level of arrestin-1 appears to be a perfect balance between rapid recovery and long-term health of rod photoreceptors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Drs. L. A. Donoso, R. S. Molday, and C.M. Craft for monoclonal anti-arrestin and anti-rhodopsin antibodies, and mouse rod arrestin cDNA, respectively, to Dr. J. B. Hurley for valuable discussion of mitochondria distribution in the retina, and to Hayley E. Boyd for technical assistance. Supported by NIH grants EY011500 (VVG), NS065868 (EVG), EY012155 (JC), and P30 core grant in vision research EY008126 (to Vanderbilt University).

Footnotes

We use systematic names of arrestin proteins: arrestin-1 (historic names S-antigen, 48 kDa protein, visual or rod arrestin), arrestin-2 (β-arrestin or β-arrestin1), arrestin-3 (β-arrestin2), and arrestin-4 (cone or X-arrestin; for unclear reasons its gene is called “arrestin 3” in HUGO database).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arshavsky VY, Lamb TD, Pugh ENJ. G proteins and phototransduction. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:153–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.082701.102229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayburt TH, Vishnivetskiy SA, McLean M, Morizumi T, Huang C-c, Tesmer JJ, Ernst OP, Sligar SG, Gurevich VV. Rhodopsin monomer is sufficient for normal rhodopsin kinase (GRK1) phosphorylation and arrestin-1 binding. J Biol Chem. 2010:285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151043. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor DA, Lamb TD, Yau KW. Responses of retinal rods to single photons. J Physiol. 1979;288:613–634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentmann A, Schmidt M, Reuss S, Wolfrum U, Hankeln T, Burmester T. Divergent distribution in vascular and avascular mammalian retinae links neuroglobin to cellular respiration. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20660–20665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501338200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisegna P, Caruso G, Andreucci D, Shen L, Gurevich VV, Hamm HE, DiBenedetto E. Diffusion of the second messengers in the cytoplasm acts as a variability suppressor of the single photon response in vertebrate phototransduction. Biophys J. 2008;94:3363–3383. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.114058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekhuyse RM, Tolhuizen EF, Janssen AP, Winkens HJ. Light induced shift and binding of S-antigen in retinal rods. Curr Eye Res. 1985;4:613–618. doi: 10.3109/02713688508999993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns ME, Arshavsky VY. Beyond counting photons: trials and trends in vertebrate visual transduction. Neuron. 2005;48:387–401. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns ME, Mendez A, Chen CK, Almuete A, Quillinan N, Simon MI, Baylor DA, Chen J. Deactivation of phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated rhodopsin by arrestin splice variants. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1036–1044. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3301-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns ME, Pugh ENJ. RGS9 concentration matters in rod phototransduction. Biophys J. 2009;97:1538–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert PD, Govardovskii VI, Krasnoperova N, Anderson RE, Lem J, Makino CL. Membrane protein diffusion sets the speed of rod phototransduction. Nature. 2001;411:90–94. doi: 10.1038/35075083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert PD, Krasnoperova NV, Lyubarsky AL, Isayama T, Nicoló M, Kosaras B, Wong G, Gannon KS, Margolskee RF, Sidman RL, Pugh ENJ, Makino CL, Lem J. Phototransduction in transgenic mice after targeted deletion of the rod transducin alpha -subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13913–13918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250478897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso G, Khanal H, Alexiades V, Rieke F, Hamm HE, DiBenedetto E. Mathematical and computational modelling of spatio-temporal signalling in rod phototransduction. Syst Biol (Stevenage) 2005;152:119–137. doi: 10.1049/ip-syb:20050019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S, Rubin WW, Mendez A, Liu X, Song X, Hanson SM, Craft CM, Gurevich VV, Burns ME, Chen J. Functional comparisons of visual arrestins in rod photoreceptors of transgenic mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1968–1075. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CK, Burns ME, He W, Wensel TG, Baylor DA, Simon MI. Slowed recovery of rod photoresponse in mice lacking the GTPase accelerating protein RGS9–1. Nature. 2000;403:557–560. doi: 10.1038/35000601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CK, Burns ME, Spencer M, Niemi GA, Chen J, Hurley JB, Baylor DA, Simon MI. Abnormal photoresponses and light-induced apoptosis in rods lacking rhodopsin kinase. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1999a;96:3718–3722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Makino CL, Peachey NS, Baylor DA, Simon MI. Mechanisms of rhodopsin inactivation in vivo as revealed by a COOH-terminal truncation mutant. Science. 1995;267:374–377. doi: 10.1126/science.7824934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Simon MI, Matthes MT, Yasumura D, LaVail MM. Increased susceptibility to light damage in an arrestin knockout mouse model of Oguchi disease (stationary night blindness) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999b;40:2978–2982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cideciyan AV, Zhao X, Nielsen L, Khani SC, Jacobson SG, Palczewski K. Null mutation in the rhodopsin kinase gene slows recovery kinetics of rod and cone phototransduction in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:328–333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizhoor AM, Olshevskaya EV, Peshenko IV. Mg(2+)/Ca (2+) cation binding cycle of guanylyl cyclase activating proteins (GCAPs): role in regulation of photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;334:117–124. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0328-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan T, Azevedo AW, Hurley JB, Rieke F. Arrestin competition influences the kinetics and variability of the single-photon responses of mammalian rod photoreceptors. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11867–11879. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0819-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolph PJ, Ranganathan R, Colley NJ, Hardy RW, Socolich M, Zuker CS. Arrestin function in inactivation of G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin in vivo. Science. 1993;260:1910–1916. doi: 10.1126/science.8316831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoso LA, Gregerson DS, Smith L, Robertson S, Knospe V, Vrabec T, Kalsow CM. S-antigen: preparation and characterization of site-specific monoclonal antibodies. Curr Eye Res. 1990;9:343–355. doi: 10.3109/02713689008999622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckmiller MS. Microtubules in a rod-specific cytoskeleton associated with outer segment incisures. Vis Neurosci. 2000;17:711–722. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800175054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias RV, Sezate SS, Cao W, McGinnis JF. Temporal kinetics of the light/dark translocation and compartmentation of arrestin and alpha-transducin in mouse photoreceptor cells. Mol Vis. 2004;10:672–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs S, Nakazawa M, Maw M, Tamai M, Oguchi Y, Gal A. A homozygous 1-base pair deletion in the arrestin gene is a frequent cause of Oguchi disease in Japanese. Nat Genet. 1995;10:360–362. doi: 10.1038/ng0795-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton AB, Rushton WA. The human rod ERG: correlation with psychophysical responses in light and dark adaptation. Vision Res. 1978;18:793–800. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(78)90119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross OP, Burns ME. Control of rhodopsin’s active lifetime by arrestin-1 expression in mammalian rods. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3450–3457. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5391-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich VV, Hanson SM, Gurevich EV, Vishnivetskiy SA. How rod arrestin achieved perfection: regulation of its availability and binding selectivity. In: Kisselev O, Fliesler SJ, editors. Methods in Signal Transduction Series. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2007. pp. 55–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm HE, Bownds MD. Protein complement of rod outer segments of frog retina. Biochemistry. 1986;25:4512–4523. doi: 10.1021/bi00364a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson SM, Cleghorn WM, Francis DJ, Vishnivetskiy SA, Raman D, Song S, Nair KS, Slepak VZ, Klug CS, Gurevich VV. Arrestin mobilizes signaling proteins to the cytoskeleton and redirects their activity. J Mol Biol. 2007a;368:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson SM, Dawson ES, Francis DJ, Van Eps N, Klug CS, Hubbell WL, Meiler J, Gurevich VV. A model for the solution structure of the rod arrestin tetramer. Structure. 2008;16:924–934. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson SM, Francis DJ, Vishnivetskiy SA, Klug CS, Gurevich VV. Visual arrestin binding to microtubules involves a distinct conformational change. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9765–9772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510738200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson SM, Gurevich EV, Vishnivetskiy SA, Ahmed MR, Song X, Gurevich VV. Each rhodopsin molecule binds its own arrestin. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2007b;104:3125–3128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610886104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson SM, Van Eps N, Francis DJ, Altenbach C, Vishnivetskiy SA, Klug CS, Hubbell WL, Gurevich VV. Structure and function of the visual arrestin oligomer. EMBO J. 2007c;26:1726–1736. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetling JR, Pepperberg DR. Sensitivity and kinetics of mouse rod flash responses determined in vivo from paired-flash electroretinograms. J Physiol. 1999;516:593–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0593v.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks D, Molday RS. Differential immunogold-dextran labeling of bovine and frog rod and cone cells using monoclonal antibodies against bovine rhodopsin. Exp Eye Res. 1986;42:55–71. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(86)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood DC, Birch DG. A computational model of the amplitude and implicit time of the b-wave of the human ERG. Vis Neurosci. 1992;8:107–126. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800009275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SP, Brown BM, Craft CM. Visual Arrestin 1 acts as a modulator for N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor in the photoreceptor synapse. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9381–9391. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1207-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries MM, Rancourt D, Farrar GJ, Kenna P, Hazel M, Bush RA, Sieving PA, Sheils DM, McNally N, Creighton P, Erven A, Boros A, Gulya KC, Humphries MRP. Retinopathy induced in mice by targeted disruption of the rhodopsin gene. Nat Genet. 1997;15:216–219. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamoto Y, Tamura C, Kamikubo H, Kataoka M. Concentration-dependent tetramerization of bovine visual arrestin. Biophys J. 2003;85:1186–1195. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74554-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keresztes G, Martemyanov KA, Krispel CM, Mutai H, Yoo PJ, Maison SF, Burns ME, Arshavsky VY, Heller S. Absence of the RGS9.Gbeta5 GTPase-activating complex in photoreceptors of the R9AP knockout mouse. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1581–1584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300456200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Hanson SM, Vishnivetskiy SA, Song X, Cleghorn WM, Hubbell WL, Gurevich VV. Robust self-association is a common feature of mammalian visual arrestin-1. J Biol Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1021/bi1018607. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krispel CM, Chen CK, Simon MI, Burns ME. Prolonged photoresponses and defective adaptation in rods of Gbeta5−/− mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6965–6971. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-18-06965.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krispel CM, Chen D, Melling N, Chen YJ, Martemyanov KA, Quillinan N, Arshavsky VY, Wensel TG, Chen CK, Burns ME. RGS expression rate-limits recovery of rod photoresponses. Neuron. 2006;51:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krispel CM, Sokolov M, Chen YM, Song H, Herrmann R, Arshavsky VY, Burns ME. Phosducin regulates the expression of transducin betagamma subunits in rod photoreceptors and does not contribute to phototransduction adaptation. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:303–312. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupnick JG, Gurevich VV, Benovic JL. Mechanism of Quenching of Phototransduction: Binding competition between arrestin and transducin for phosphorhodopsin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18125–18131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobanova ES, Finkelstein S, Herrmann R, Chen YM, Kessler C, Michaud NA, Trieu LH, Strissel KJ, Burns ME, Arshavsky VY. Transducin gamma-subunit sets expression levels of alpha- and beta-subunits and is crucial for rod viability. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3510–3520. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0338-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo DG, Xue T, Yau KW. How vision begins: an odyssey. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9855–9862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708405105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubarsky AL, Daniele LL, Pugh ENJ. From candelas to photoisomerizations in the mouse eye by rhodopsin bleaching in situ and the light-rearing dependence of the major components of the mouse ERG. Vision Res. 2004;44:3235–3251. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubarsky AL, Lem J, Chen J, Falsini B, Iannaccone A, Pugh ENJ. Functionally rodless mice: transgenic models for the investigation of cone function in retinal disease and therapy. Vision Res. 2002;42:401–415. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubarsky AL, Pugh EN., Jr Recovery phase of the murine rod photoresponse reconstructed from electroretinographic recordings. J Neurosci. 1996;16:563–571. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00563.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino CL, Wen XH, Lem J. Piecing together the timetable for visual transduction with transgenic animals. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:404–412. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez A, Burns ME, Roca A, Lem J, Wu LW, Simon MI, Baylor DA, Chen J. Rapid and reproducible deactivation of rhodopsin requires multiple phosphorylation sites. Neuron. 2000;28:153–164. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair KS, Hanson SM, Mendez A, Gurevich EV, Kennedy MJ, Shestopalov VI, Vishnivetskiy SA, Chen J, Hurley JB, Gurevich VV, Slepak VZ. Light-dependent redistribution of arrestin in vertebrate rods is an energy-independent process governed by protein-protein interactions. Neuron. 2005:46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikonov SS, Brown BM, Davis JA, Zuniga FI, Bragin A, Pugh EN, Jr, Craft CM. Mouse cones require an arrestin for normal inactivation of phototransduction. Neuron. 2008;59:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northrup SH, Erickson HP. Kinetics of protein-protein association explained by Brownian dynamics computer simulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:3338–3342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepperberg DR, Birch DG, Hood DC. Photoresponses of human rods in vivo derived from paired-flash electroretinograms. Vis Neurosci. 1997;14:73–82. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800008774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peshenko IV, Dizhoor AM. Ca2+ and Mg2+ binding properties of GCAP-1. Evidence that Mg2+-bound form is the physiological activator of photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23830–23841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philp NJ, Chang W, Long K. Light-stimulated protein movement in rod photoreceptor cells of the rat retina. FEBS Lett. 1987;225:127–132. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh EN, Jr, Falsini B, Lyubarsky AL. The origin of the major rod- and cone-driven components of the rodent electroretinogram, and the effect of age and light-rearing history on the magnitudes of these components. In: Williams TP, Thistle AB, editors. Photostasis and Related Phenomena. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. pp. 93–128. [Google Scholar]

- Pugh EN, Jr, Lamb TD. Phototransduction in vertebrate rods and cones: Molecular mechanisms of amplification, recovery and light adaptation. In: Stavenga DG, et al., editors. Handbook of Biological Physics. Molecular Mechanisms in Visual Transduction. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2000. pp. 183–255. [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan R, Stevens CF. Arrestin binding determines the rate of inactivation of the G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin in vivo. Cell. 1995;81:841–848. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieke F, Baylor DA. Origin of reproducibility in the responses of retinal rods to single photons. Biophys J. 1998;75:1836–1857. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77625-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson JG, Frishman LJ. Response linearity and kinetics of the cat retina: the bipolar cell component of the dark-adapted electroretinogram. Vis Neurosci. 1995;12:837–850. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800009408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson JG, Frishman LJ. Dissecting the dark-adapted electroretinogram. Doc Ophthalmol. 1999;95:187–215. doi: 10.1023/a:1001891904176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert C, Hirsch JA, Gurevich VV, Engelman DM, Sigler PB, Fleming KG. Visual arrestin activity may be regulated by self-association. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21186–21190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Caruso G, Bisegna P, Andreucci D, Gurevich VV, Hamm HE, Dibenedetto E. Dynamics of mouse rod phototransduction and its sensitivity to variation of key parameters. IET Syst Biol. 2010;4:12–32. doi: 10.1049/iet-syb.2008.0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov M, Lyubarsky AL, Strissel KJ, Savchenko AB, Govardovskii VI, Pugh EN, Jr, Arshavsky VY. Massive light-driven translocation of transducin between the two major compartments of rod cells: a novel mechanism of light adaptation. Neuron. 2002;34:95–106. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00636-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Vishnivetskiy SA, Gross OP, Emelianoff K, Mendez A, Chen J, Gurevich EV, Burns ME, Gurevich VV. Enhanced Arrestin Facilitates Recovery and Protects Rod Photoreceptors Deficient in Rhodopsin Phosphorylation. Curr Biol. 2009;19:700–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone J, van Driel D, Valter K, Rees S, Provis J. The locations of mitochondria in mammalian photoreceptors: relation to retinal vasculature. Brain Res. 2008;1189:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strissel KJ, Sokolov M, Trieu LH, Arshavsky VY. Arrestin translocation is induced at a critical threshold of visual signaling and is superstoichiometric to bleached rhodopsin. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1146–1153. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4289-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang SH, Burns ME, Calvert PD, Gouras P, Baylor DA, Goff SP, Arshavsky VY. Role for the target enzyme in deactivation of photoreceptor G protein in vivo. Science. 1998;282:117–121. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishnivetskiy SA, Raman D, Wei J, Kennedy MJ, Hurley JB, Gurevich VV. Regulation of arrestin binding by rhodopsin phosphorylation level. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32075–32083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706057200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen XH, Shen L, Brush RS, Michaud N, Al-Ubaidi MR, Gurevich VV, Hamm HE, Lem J, Dibenedetto E, Anderson RE, Makino CL. Overexpression of rhodopsin alters the structure and photoresponse of rod photoreceptors. Biophys J. 2009;96:939–950. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan JP, McGinnis JF. Light-dependent subcellular movement of photoreceptor proteins. J Neurosci Res. 1988;20:263–270. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490200216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilden U. Duration and amplitude of the light-induced cGMP hydrolysis in vertebrate photoreceptors are regulated by multiple phosphorylation of rhodopsin and by arrestin binding. Biochemistry. 1995;34:1446–1454. doi: 10.1021/bi00004a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N, Hanson SM, Francis DJ, Vishnivetskiy SA, Thibonnier M, Klug CS, Shoham M, Gurevich VV. Arrestin binding to calmodulin: a direct interaction between two ubiquitous signaling proteins. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:955–963. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]