Abstract

Individuals with autism display deficits in the social domain including the proper recognition of faces and interpretations of facial expressions. There is an extensive network of brain regions involved in face processing including the fusiform gyrus (FFG) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC). Functional imaging studies have found that controls have increased activity in the PCC and FFG during face recognition tasks, and the FFG has differential responsiveness in autism when viewing faces. Multiple lines of evidence have suggested that the GABAergic system is disrupted in the brains of individuals with autism and it is likely that altered inhibition within the network influences the ability to perceive emotional expressions. On-the-slide ligand binding autoradiography was used to determine if there were alterations in GABAA and/or benzodiazepine binding sites in the brain in autism. Using 3H-muscimol and 3H-flunitrazepam we could determine whether the number (Bmax), binding affinity (Kd), and/or distribution of GABAA receptors and its benzodiazepine binding sites (BZD) differed from controls in the FFG and PCC. Significant reductions in the number of GABAA receptors and BZD binding sites in the superficial layers of the PCC and FFG, and in the number of BZD binding sites were found in the deep layers of the FFG. In addition, the autism group had a higher binding affinity in the superficial layers of the GABAA study. Taken together, these findings suggest that the disruption in inhibitory control in the cortex may contribute to the core disturbances of socio-emotional behaviors in autism.

Keywords: GABA, benzodiazepine, autism, cingulate, fusiform gyrus, receptor, neuropathology, PCC, FFG

1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental syndrome observed before three years of age. Children and adults with ASD are markedly inattentive to faces, show poorer facial identity discrimination and fixate less to the eye region (Sigman et al., 1986; Klin et al., 1999). Although individuals with autism are not incapable of attending to the face, when they do, they may process the information in much the same manner as inanimate objects (Hobson et al., 1988; Schultz et al., 2000).

Faces are multi-dimensional stimuli conveying complex social and motivational signals simultaneously. Functional brain-imaging studies have delineated an extensive network implicated in face processing in humans, including the fusiform gyrus, and several limbic system regions such as the amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, and posterior cingulate cortex (Kanwisher et al., 1997; Haxby et al., 2000; Ishai et al., 2000). Regions within this network are associated with functions related to socio-emotional processing. For example, the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) is active during simple emotions driven by faces (Fink et al., 1996; Shah et al., 2001). Interactions between emotion and face perception may provide insights into more general mechanisms underlying reciprocal links between emotion and cognitive processes and the dysfunction of this network in autism.

The etiology of autism is poorly defined both at the cellular and the molecular level. Despite considerable effort toward the identification of chromosome regions affected in autism, only a few genes have been reproducibly shown to display specific mutations (e.g. Schroer et al., 1998; Nakatani et al., 2009). A number of genetic studies have implicated subunits of the GABAA receptor, suggesting that GABA changes can influence the developmental trajectory of the brain in autism (Schroer et al., 1998; Fatemi et al., 2009). Glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 and 67 (GAD65, GAD67), key enzymes for GABA synthesis, is decreased in the cortex and altered in the cerebellum (Fatemi et al., 2002, Yip et al., 2007, 2008, 2009). Furthermore, GABAA receptors and benzodiazepine binding sites are decreased in limbic regions (Blatt et al., 2001; Guptill et al., 2007; Oblak et al., 2009). Additionally, protein levels for GABAA receptor subunits are reduced in multiple cortical areas (Fatemi et al., 2009). Together, these findings suggest that alterations in GABA system, can potentially affect cortical circuit formation.

The GABAA receptor contains a combination of five subunits and has binding sites for many modulators including benzodiazepines (BZDs). Benzodiazepine binding sites are allosteric modulatory sites on GABAA receptors and have been used as anxiolytics, muscle relaxants, sedatives, and anticonvulsants (Sieghart, 1993). Co-morbid seizure disorder is relatively common in autism and has been estimated to occur in 25-33% of individuals (Olsson et al., 1988; Volkmar & Nelson, 1990). The present study examined two regions within the socio-emotional processing network, the fusiform gyrus and posterior cingulate cortex to determine whether a common deficit in GABAA receptors and its benzodiazepine binding sites occurs in the autism group relative to controls. A discussion of how results might contribute to the underlying face-processing and social behavior deficits in autism follows.

2. Results

Overall there were significant reductions in the number of GABAA receptors and benzodiazepine binding sites in both areas in the group of patients with autism when compared to the controls. Furthermore, the Kd in the patients with autism was significantly lower than controls in the superficial layers of GABAA receptors indicating an increased binding affinity. Individual case information for Bmax and Kd values for both GABAA and BZD binding is available in the supplementary data (Tables I-IV).

2.1 GABAA Receptor Binding

2.1.1 Posterior Cingulate Cortex

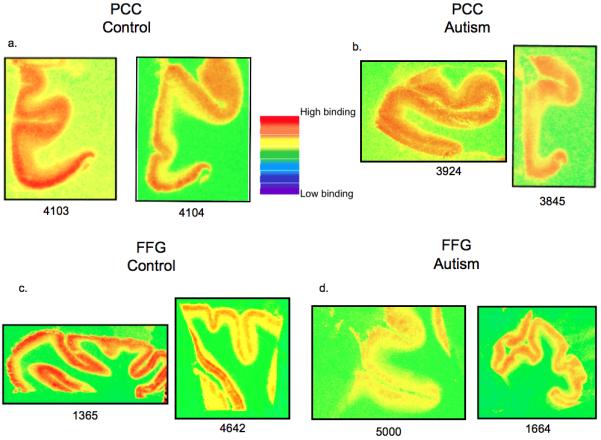

Figure 3 is a pseudocolored image of a control and autism case demonstrating reduced 3H-Muscimol labeled GABAA receptor binding. Multiple concentration binding experiments revealed that all autistic cases fell below the mean Bmax value for control cases in the superficial layers of the posterior cingulate cortex. The results from the seven concentration binding study indicates a significant reduction of GABAA receptors (Bmax) in the superficial layers (p=4.0×10−6) of the posterior cingulate cortex in the group of patients with autism (n=7) when compared to age- and post-mortem interval (PMI) matched controls (n=6; Figure 4). The Bmax values demonstrate that there was a 49.0% reduction in GABAA receptors.

Figure 3.

3H-muscimol labeled GABAA receptor binding density in the PCC (a,b) and FFG (c,d) from two patients with autism and two controls (4103, 4104). Case numbers are under each image. Images are taken from 3H sensitive film (concentration 15nM). Note the reduced binding density in the patients with autism (b,d) compared to the control (a,c) cases. Also note the variability in binding that occurs within groups.

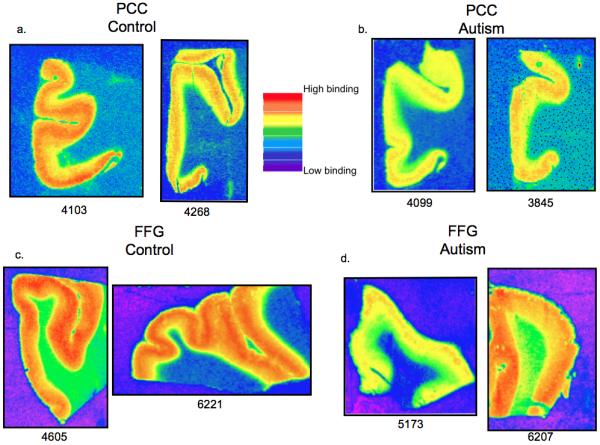

Figure 4.

3H-flunitrazepam labeled benzodiazepine binding site density in the PCC (a,b) and FFG (c, d) from two patients with autism and two control cases. Case numbers are below each image. Images are taken from 3H sensitive film (concentration 5nM). There is reduced binding density in individuals with autism (b,d) when compared to the control (a,c) cases in both the PCC and FFG. Note the variability in binding between cases within a group.

2.1.2 Fusiform Gyrus

Figure 3 is a pseudocolored image demonstrating the reduced 3H-Muscimol labeled GABAA receptors in the FFG. Similar to the PCC results, all autism cases fell below the mean of the control group in the superficial layers. The multiple concentration binding experiments in the fusiform gyrus demonstrated significant reductions in the individuals with autism (n=8) for the number of GABAA receptors (BAmax value) in the superficial layers (p= 5.20×10−6) when compared to controls (n=10; Figure 5). The Bmax values indicated that there was a 31.2% reduction in the number of GABAA receptors. Similar to the PCC results, the number of GABAA receptors did not differ from the controls in the deep layers. Age and post-mortem interval were similar in the cases in both groups.

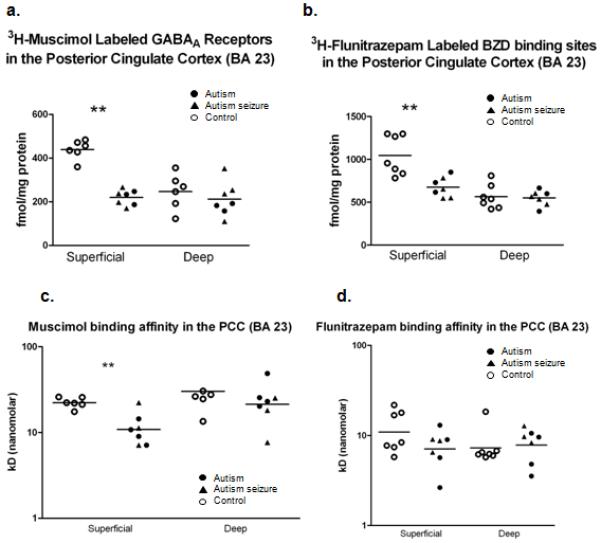

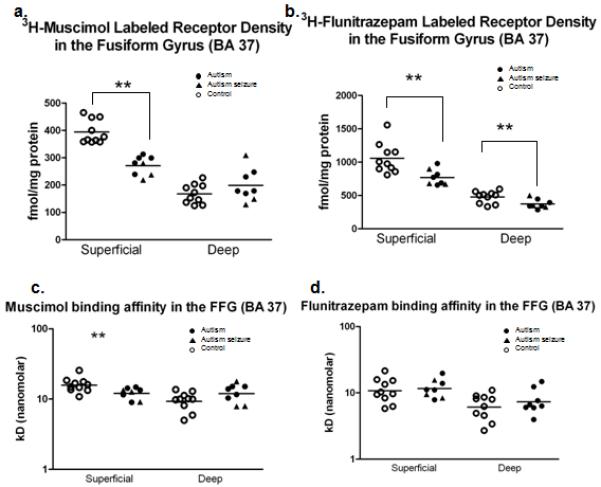

Figure 5.

Scatter plots demonstrating the density of GABAA receptors (a) and benzodiazepine binding sites (b) in the posterior cingulate cortex. Each symbol represent an individual case. Significant reductions were found in the superficial layers of both GABAA receptors (p=4.00 e-6) and BZD binding sites (p=0.0044) in autism. No change was found in the deep layers. Binding affinity was calculated for muscimol (c) and flunitrazepam (d). A significant decrease in the Kd (p=0.0024) was observed in the superficial layers of the autism group in the muscimol study only. Asterisk (**) denotes where significance was found.

2.2 Benzodiazepine Binding Sites

2.2.1 Posterior Cingulate Cortex

The results from the seven concentration binding study indicated a significant decrease in the Bmax values in the superficial layers (p=4.00 × 10−6) of the posterior cingulate cortex in autism (Figure 5). The multiple concentration binding study revealed a 35.0% reduction in benzodiazepine binding sites in the superficial layers in individuals with autism, but equivalent values for the deep layers. Figure 4 is a pseudocolored image demonstrated the reduced BZD binding density. Again, all patients with autism fell below the mean of the control cases. There was no significant difference observed in binding affinity (Figure 5).

2.2.2 Fusiform Gyrus

The multiple concentration binding assays demonstrated significant reductions in the number of BZD binding sites in the fusiform gyrus in patients with autism (p=0.0052; n=8) when compared to controls (n=10; Figures 4 and 6), and values for all individuals with autism were below the mean of the control group in the superficial layers only. The reduction in the number of binding sites was calculated to be 27.2% in autism. In contrast to the results in the PCC, there was a significant 21.5% reduction in the number of BZD binding sites in the deep layers of the FFG in the individuals with autism (p=0.017). No significant difference in binding affinity was found in this study (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Scatter plots demonstrating the density of GABAA receptors (a) and benzodiazepine binding sites (b) in the fusiform gyrus. Each symbol represents an individual case. Significant reductions were found in the superficial layers of both GABAA receptors (p=5.2 e-6) and BZD binding sites (p=0.0052) in autism. Further, significant reductions in BZD binding were found in the deep layers (0.017). Binding affinity was calculated for muscimol (c) and flunitrazepam (d). A significant decrease in the Kd was observed in the superficial layers of the autism group (p=0.016) in the muscimol study only. Asterisk (**) denotes where significance was found.

2.3 Effect of seizure on GABAA receptor and BZD binding site number

In the posterior cingulate cortex, four of the cases had a reported history of at least one seizure. A non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was completed to determine if the presence of seizure in the autism group had any effect of the number of GABAA receptors or BZD binding sites. No significant difference between the patients with autism with a history of seizure and the patients with autism with no history of seizure was found in either the GABAA or BZD study. In the fusiform gyrus study, four of the cases had a reported history of seizure. Again, using a Mann-Whitney U test, no difference between the autism cases with a history of seizure and the autism cases with no history of seizure in either of the GABAA or BZD studies.

There was a significant difference in the binding affinity in the superficial layers of both the PCC and FFG in the 3H-Muscimol study. The individuals with autism demonstrated a significantly lower Kd, similar to that found in the posterior cingulate cortex and fusiform gyrus (Figures 5 and 6). There was no difference in binding affinity between the autism group with a history of seizure when compared to the autism group with no seizure.

3. Discussion

Each region within the extensive network of face and emotional processing may underlie separate and functionally specific processes (Adolphs, 2003). Autism may be characterized by multiple disruptions to individual processes or, deficits could arise from a single impairment with cascading deleterious effects on the downstream processing of specific social cues. The downstream effects could occur directly, via disruptions in typical patterns of information flow or could occur indirectly, via disrupting the normal accumulation of socially relevant experiences (Schultz et al., 2005). In this study, we investigated the GABAA receptor system in the posterior cingulate cortex and fusiform gyrus and discuss how altered inhibitory modulation within the network might affect the ability to properly process socio-emotional behaviors.

3.1 GABA in development and dysfunction in autism

Most theories regarding amino acid neurotransmitters in autism suggest that the GABAergic system is suppressed, resulting in excessive stimulation of the glutamate system (e.g. Rubenstein and Merzenich, 1998; Hussman, 2001). This can be attributed to several findings. First, researchers found abnormalities in cellular development in the limbic system and cerebellum postmortem (Kemper and Bauman, 1993; Raymond et al., 1996). Secondly, glutamate activity peaks during the second year of life (Kornhuber et al., 1989), a time when symptoms of autism emerge. A hyperfunctional system could result in increased release of GABA from interneurons, resulting in a compensatory downregulation of receptors.

GABAA receptor activation can influence DNA synthesis in proliferative cells (LoTurco et al., 1995), cell motility and morphological development in early postmitotic neurons (Barbin et al., 1993; Behar et al., 1996; Marty et al. 1996). There are a number of studies that report that the development of the cerebral cortex is abnormal in autism. Bailey and colleagues (1998) found irregular laminar patterning in the frontal cortex, with abnormally oriented pyramidal cells, increased white matter neurons, and increased neurons in layer I. Irregular laminar patterning has been found in the anterior cingulate cortex in autism (Simms et al., 2009). The frontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex has previously been found to down-regulate protein levels for GABAA receptor subunits (Fatemi et al., 2009) as well as reduced GABAA receptors and BZD binding sites (Oblak et al., 2009).

3.2 Face-processing abnormalities in autism: the role of the FFG and PCC

There is converging evidence in non-human primates and humans that eyes are viewed more frequently than any other region of the face when viewed in an upright manner (Hirata et al., 2010; Farroni et al., 2006). However, little is known about the specific visual properties of faces that activate the FFG, what neural interactions within the FFG underlie face processing, and how accumulated experience and other brain regions may shape the development and dysfunction of the FFG in autism. However, an important component of face recognition is emotion processing. The recognition of facial expressions of emotion is thought to develop slowly during the first two years of life, a time frame when the symptoms of autism become apparent, and continue to mature into adolescence.

The posterior cingulate cortex appears preferentially involved in visuospatial cognition (Olson et al., 1992; 1996), and is part of a network recruited when typically developing subjects see the faces or hear the voices of emotionally significant people in their lives (Maddock, 2001) and modulates emotion by responding to emotional scripts and faces (Mayberg et al., 1999). Individuals with autism are known to have difficulties in the perception of faces, direction of eye gaze, lack of eye contact and are impaired in face recognition abilities failing to use eye gaze and facial expression to regulate social interaction (Braverman et al., 1989; Davies et al., 1994; Joseph and Tanaka, 2003).

Early studies of adults with ASD compared to controls found evidence for reduced FFG activation and greater object-area activation by faces, even though measures of attention to the faces were similar (Schultz et al., 2000; Pierce et al., 2001; Hubl et al., 2003). The apparent failure of individuals with ASD to develop normal cortical face specialization in the fusiform gyrus and “expertise” in face recognition may be the accumulated effect of reduced social interest and lack of motivation to view faces (Schultz et al., 2000; Pierce et al., 2001; Hubl et al., 2003). However, other studies found FFG activation by faces that was modulated by personal familiarity in ASD (Pierce et al., 2004), or FFG activation that was indistinguishable from controls. Using eye-tracking, a recent study suggested that this disparity of findings might be explained by differences in fixation behavior (Dalton et al., 2005).

The current study found significant reductions in the number of GABAA receptors and BZD binding sites in the superficial layers of the PCC, the layers that actively modulate information that arrives from other cortical and/or thalamic regions within the circuit. It is likely that synaptic information entering the superficial layers of the PCC is being modulated in a different manner than controls. This information is then passed on to the deep layers and sent to higher order cortical regions to be processed, the modulation in the PCC at this level seems to be intact as there were no differences in GABAA receptor or BZD binding site number. Significant reductions in the number of GABAA receptors and BZD binding sites in the superficial layers and a reduction in BZD binding sites in the deep layers of the FFG were also demonstrated. This suggests that, similar to the PCC findings, information about emotion from faces and eye gaze, entering the FFG from cortical regions could also be abnormal in autism.

In contrast, the deep layers of the FFG in the autism group have a normal number of GABAA receptors. Thus, the information is being sent further downstream with the same GABAA modulation as controls, but the information that is received from the superficial layers is modulated with less inhibitory control. The resultant output in the autistic brain could be substantially different thereby leading to reduced face and emotion processing. Therefore, relevant neurochemical or neuroanatomical events may occur relatively early in the development of the central nervous system (CNS) resulting in deficits in one or more of the cortical regions involved socio-emotional processing.

3.3 Effects of seizures and anti-epileptic medication on Bmax and Kd values of GABAA and BZD binding

A significant reduction in the BZD binding site number was found in the superficial layers of the PCC and throughout the FFG in the autism cases paralleled by a change in the binding affinity. Alterations in GABAA receptor subunit expression are documented in human epilepsy (Loup et al., 2000, 2006) and in animal models of epilepsy (Gilby et al., 2005; Li et al., 2006). The evidence from these studies suggests that a shift in mRNA subunit expression can occur such that the α4 subunit is increased, but α1 is decreased (Brooks-Kayal et al., 2009). If this were the case in autism, it is likely that the number of [3H]-flunitrazepam binding sites would not change, as the α4 subunits do not contain a [3H]-flunitrazepam binding site.

In the superficial layers of the PCC and FFG, the number of [3H]-flunitrazepam receptors was also decreased, arguing that the number of GABAA receptors was due to a loss of receptors rather than an effect of binding affinity. However, in the deep layers of the FFG, the number of [3H]-flunitrazepam binding sites was not paralleled by a reduced number of [3H]-muscimol receptor binding. This would argue that it is possible for subunit switching to occur here, in an area prone to seizure, the temporal lobe, however, the binding affinity was not altered in the deep layers. Furthermore, the binding affinity of autism cases with a history of seizure did not differ indicating that the change in affinity is most likely due to the autism diagnosis. However, this conclusion is tentative due to the small number of cases that had a positive seizure history. These results do not rule out the possibility that changes occur in other regions of the brain that might be more susceptible to epileptiform activity. Therefore, it will be important for future studies to control for seizure, antiepileptics, and increase the number of subjects.

In summary, there are a number of possible explanations for the reduction in GABAA receptors and BZD binding sites in the brains of individuals with autism. First, the reduction in GABAA receptors and BZD binding is a consistent deficit in autism, with similar findings in the hippocampus and anterior cingulate cortex (Blatt et al., 2001; Guptill et al., 2007; Oblak et al., 2009a) suggesting widespread GABA receptor abnormalities in the autistic cases, irrespective of seizure and medication history. Second, it is possible that a defect in one or more of the GABAA receptor subunits exists. Fatemi et al., (2009) found reduced proteins in three of the GABAA receptor subunits in autism in multiple cortical regions and genetic studies found significant association and gene-gene interactions of specific GABA receptor subunit genes in autism (Ma et al., 2005). Molecular and genetic/epigenetic studies are needed to determine whether deficits in subunit composition are in part contributing to the reduced GABAA receptor binding in autism.

4. Experimental Procedure

4.1 Case Data

The following is a list of cases used in the study (Tables 1 and 2). There were a total of 15 post-mortem cases from patients with autism used (7 for the PCC study, 8 for the FFG study) and 17 controls (7 for the PCC study, 10 for the FFG study). The patients with autism ranged in age from 14-37 years and the controls ranged from 16- 43 years. The post-mortem interval (PMI) was less than 30 hours for the entire study. There was no difference between individuals with autism and control group in age or PMI (student’s t-test). Note that seven of fifteen cases (PCC and FFG) from the individuals with autism had a history of at least one seizure (1484, 2825, 3845, 3924, 5173, 6337, 6677). Also, four of the cases (PCC and FFG) from the patients with autism were treated with anticonvulsants (2825, 3845, 5173, 6677). There were seven individuals with autism and six control cases for PCC study; and nine cases from patients with autism and ten control cases from the FFG. All cases used in the study had an autism diagnosis of moderate to severe.

Table 1.

Posterior Cingulate cortex case information

| CASE | DIAGNOSIS | AGE (YEARS) |

PMI (HOURS) |

CAUSE OF DEATH |

GENDER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1401 | Autism | 21 | 20.6 | Sepsis | Female |

| 1484* | Autism | 19 | 15 | Burns | Male |

| 2825*▲ | Autism | 19 | 9.5 | Heart attack | Male |

| 3845*‡ | Autism | 30 | 28.4 | Cancer | Male |

| 3924 | Autism | 16 | 9 | Seizure | Female |

| 4099 | Autism | 19 | 3 | Conj. Heart Failure |

Male |

| 5754 | Autism | 20 | 29.98 | Unknown | Male |

| Mean | 21.4 | 17.3 | |||

| 4103 | Control | 43 | 23 | Heart attack/disease |

Male |

| 4104 | Control | 24 | 5 | Gun shot | Male |

| 4267 | Control | 26 | 20 | Accidental | Male |

| 4268 | Control | 30 | 22 | Heart attack/disease |

Male |

| 4271 | Control | 19 | 21 | Epiglotitus | Male |

| 4275 | Control | 20 | 16 | Accidental | Male |

| 4364 | Control | 27 | 27 | Motor Vehicle Accident |

Male |

| Mean | 25.9 | 19.0 |

The following symbols indicate medication history:

Klonopin, Mysoline, Phenobarbitol, Thorazine

Dilantin, Mellaril, Phenobarbital

Note:

Cases with an asterisk had a history of at least one seizure.

Table 2.

Fusiform gyrus case information

| CASE | DIAGNOSIS | AGE (YEARS) |

PMI (HOURS) |

CAUSE OF DEATH |

GENDER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1664 | Autism | 20 | 15 | Unknown | Male |

| 4899 | Autism | 14 | 9 | Drowning | Male |

| 5027 | Autism | 37 | 26 | Bowel Obstruction | Male |

| 5000 | Autism | 27 | 8.3 | Drowning | Male |

| 5144 | Autism | 20 | 23.7 | Auto Trauma | Male |

| 5173*◇ | Autism | 30 | 20.3 | GI bleeding | Male |

| 6337* | Autism | 22 | 25 | Choked | Male |

| 6756* | Autism | 16 | 22 | Myocardial Infarction |

Male |

| 6677* | Autism | 30 | 16 | Congestive heart failure |

Male |

| Mean | 24.0 | 18.4 | |||

| 602 | Control | 27 | 15 | Accident | Male |

| 1026 | Control | 28 | 6 | Cogenital Heart Disease |

Male |

| 1365 | Control | 28 | 17 | Multiple Injuries | Male |

| 4605 | Control | 29 | 18.3 | Renal Failure | Male |

| 4642 | Control | 28 | 13 | Cardiac Arrythmia | Male |

| 4916 | Control | 19 | 5 | Drowning | Male |

| 5873 | Control | 28 | 23.3 | Unknown | Male |

| 6004 | Control | 36 | 18 | Unknown | Female |

| 6207 | Control | 16 | 26.2 | Heart Attack | Male |

| 6221 | Control | 22 | 24.2 | Unknown | Male |

| Mean | 26.1 | 16.6 | |||

The following symbol indicate medication history:

Cisapride, Clorazepate, Depakote, Dilantin, Mysoline, Phenobarbital

Note:

Cases with one asterisk had a history of at least one seizure.

4.2 Regions of interest

4.2.1 Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC; Brodmann Area 23)

The PCC (BA 23) has a prominent layer IV and a less prominent layer V (Vogt et al., 1995) when compared to the adjacent anterior cingulate cortex. The PCC consists of areas 23a, 23b, 23d, which reside at the surface of the posterior cingulate gyrus. Area 23c lies in the ventral bank of the caudal cingulate sulcus (Vogt et al., 1987, 1995). Areas 23a and 23b are divided into ventral and dorsal. These regions are differentiated from each other on the basis of cytoarchitecture and connectivity and are functionally distinct (Goldman-Rakic et al., 1984; Morris et al., 1999; Vogt et al., 2005). It is suggested that both the ventral and dorsal areas of 23a/b contribute to spatial memory (Maguire, 2001). However, ventral area 23a/b may contribute to verbal and auditory memory (Rudge and Warrington, 1991). For the purposes these studies, only area 23 is considered, and not the subregions or the dorsal/ventral dichotomy. Blocks from the posterior cingulate were removed at the brain bank, and Nissl stained sections were used to differentiate BA 23 from the surrounding areas (Vogt et al., 2006). In order to reduce heterogeneity within the region, every effort was made to match the levels of the blocks removed from the Brain Bank.

4.2.2 Fusiform Gyrus (FFG; Brodmann Area 37)

The fusiform gyrus (occipitotemporal gyrus) extends the length of the inferior occipitotemporal surface, bound medially by the parahippocampal gyrus and laterally by the occipitotemporal gyrus in humans. BA 37 is a subdivision of the cytoarchitectually defined temporal region of cerebral cortex, located primarily in the caudal portions of the fusiform gyrus and inferior temporal gyrus. The fusiform gyrus was identified on tissue at the brain bank as follows: the medial margin was defined by the collateral and rhinal sulci and the lateral boundary was identified as the sulcus medial to the inferior temporal gyrus (McDonald et al., 2000). Von Economo (1927) has characterized the fusiform gyrus with the following feature: (1) layer I is slightly thicker on average than other cortical regions; (2) layer II is not densely packed, containing mostly granule cells and also some pyramidal cells; (3) layer III is relatively thick and richer in cells; (4) layer IV is compact with large granule cells; (5) layer V is divided into a thin superficial sublayer Va and is composed of densely packed, small, triangular cells, and a deeper sublayer Vb with large cells; (6) layer VI is relatively thin and has a compact layer VIa with large triangular and spindle shaped neurons and a deeper layer VIb which is thinner than other areas but contains spindle cells. Although the FFG has been attributed to several functions including processing of color information, word and number recognition as well as face and body recognition (Allison et al., 1994; Kanwisher et al., 1997), there have not been reports of regions subserving these functions having different cytoarchitectonic patterning. Therefore, the blocks of tissue were taken from similar levels of the FFG, the lateral side of the mid-fusiform gyrus, which has been shown in imaging literature to be responsible for face-processing (Kanwisher et al., 1997) and the entire FFG region was sampled from each block.

4.3 Multiple-Concentration Binding Assays

Tissue blocks were coronally sectioned at 20μm using a Hacker/Brights motorized cryostat at −20°C. The sections were thaw mounted on 2×3 inch gelatin coated glass slides. Two sections from each case were used to determine total binding and one section from each case was used to determine non-specific binding for each of seven concentrations. The ligand used for GABAA receptors was [3H]-Muscimol (specific activity 36.6 Curies/millimole; Ci/mmol; New England Nuclear) and the ligand for BZD binding sites was [3H]-flunitrazepam (specific activity 87.2 Ci/mmol; New England Nuclear). Non-specific binding was measured by adding a competitive displacer (see Table 3) to the tritiated ligand and buffer solution at a high concentration. The selected sections from all cases were assayed in parallel in order to eliminate variability in binding conditions. Slides were dried overnight under a cool stream of air, loaded into X-ray cassettes with a tritium standard (Amersham) and apposed to tritium-sensitive film (3H-Hyperfilm, Kodak). Once the exposure time elapsed, the films were developed for 4 minutes with Kodak D19 developer, fixed with Kodak Rapidfix (3 minutes) at room temperature, and allowed to air dry. Slides were stained with thionin to determine cytoarchitecture and laminar distribution of the posterior cingulate cortex and fusiform gyrus. Superficial layers corresponded to cortical layers I-IV and deep layers to layers V-VI.

Table 3.

Multiple Concentration Binding Conditions for GABAA receptors and Benzodiazepine binding sites in the posterior cingulate cortex and fusiform gyrus

| Ligand | Target | Concentration (nM) |

Displacer | Exposure Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3[H]-Muscimol | GABAA Receptor | [0.14, 1.84, 2.77, 5.26, 13.6, 17.5, 149] |

100mM GABA | 6-390 days |

|

3[H]- Flunitrazepam |

Benzodiazepine binding site |

[0.16, 0.95, 2.90, 4.11, 16.7, 37.0, 123] |

100mM Clonazepam |

10-230 days |

4.4 Data Analysis

Using an Inquiry densitometry system (Loats Associates), the film autoradiograms were digitized to gather quantitative measurements of optical density. The superficial and deep layers were sampled from each case. The tritiated standards that were exposed with the sections were used to calibrate the autoradiograms to quantify the amount of ligand bound per milligram of tissue in the tissue sections. Optical density for the standards, as a function of specific activity (corrected for radioactive decay), was fitted to the equation optical density = B1*(1-10k1(specific activity))+B3, by nonlinear least squares regression adjusting the values of the parameters k1, B1, and B3 using the Solver tool of Excel (Microsoft Office XP Professional) to construct a standard curve and to convert the measured optical densities into nCi/mg. Binding in femptomoles per milligram of tissue (fmol/mg) was calculated based on the specific activity of each ligand.

4.5 Statistical Analyses

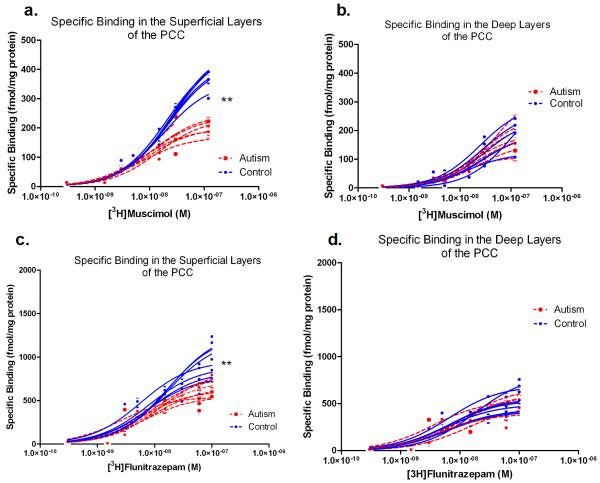

Specific binding of the tritiated ligands in the superficial and deep layers from each case was fitted independently with a hyperbolic binding equation to estimate binding affinity (Kd) and number of receptors (Bmax) for each region. Examples of binding curves are shown in Figures 1 and 2. Least-squares fitting was carried out via the Microsoft Excel Solver tool. Bmax data is reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Averaged Kd ((Kd)av) = (((10(x + s) – 10x) + (10x – 10(x-s)))/2), where x = mean(logKd) and s = the SEM of the log (Kd) values. Student’s t-tests with unequal variances were performed to determine if there was a significant difference between patients with autism and control cases in the superficial and deep layers of the PCC and FFG. Mann-Whitney U non-parametric tests were carried out to determine if the number of GABAA receptors and BZD binding sites in cases from patients with autism with a history of seizure differed from those patients with autism with no history of seizure using p<0.05 as criterion. Note that the number of cases that received anticonvulsant therapy did not meet criterion for statistical testing.

Figure 1.

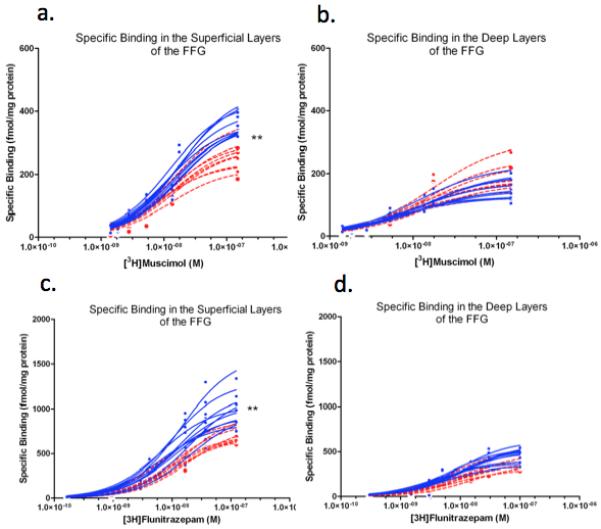

Examples of individual binding curves for the 3H-Muscimol and 3H-Flunitrazepam study is illustrated. Specific binding of 3H-Muscimol and 3H-Flunitrazepam in the superficial (a,c) and deep (b,d) layers of the PCC is illustrated. Each line represents an individual case. Smooth curves indicate fit to the hyperbolic binding equation. Autism in red, control in blue. Asterisk (**) denotes where significance was found.

Figure 2.

Examples of individual binding curves for the 3H-Muscimol and 3H-Flunitrazepam study. Each line represent an individual case. Specific binding of 3H-Muscimol and 3H-Flunitrazepam in the superficial (a,c) and deep (b,d) layers of the FFG. Smooth curves indicate fit to the hyperbolic binding equation. Autism in red, control in blue. Asterisk (**) denotes where significance was found.

Supplementary Material

5. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a “Studies to Advance Autism Research and Treatment” grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH U54 MH66398) and the Hussman Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Adrian L. Oblak, Boston University School of Medicine, Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, Laboratory of Autism Neuroscience Research, 72 East Concord Street, L-1004, Boston, MA 02118, Phone: 617-638-4134, Fax: 617-638-4922

Terrell T. Gibbs, Boston University School of Medicine, Department of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 72 East Concord Street, L-606, Boston, MA 02118, Phone: 617-638-5325, Fax: 617-638-4329

Gene J. Blatt, Boston University School of Medicine, Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, Laboratory of Autism Neuroscience Research, 72 East Concord Street, L-1004, Boston, MA 02118, Phone: 617-638-5260, Fax: 617-638-4216

6. Literature Cited

- Adolphs R, Tranel D, Damasio AR. Dissociable neural systems for recognizing emotions. Brain and Cognition. 2003;52(1):61–69. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(03)00009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison T, McCarthy G, Nobre A, Puce A, Belger A. Human extrastriate visual cortex and the perception of faces, words, numbers, and colors. Cereb Cortex. 1994;4(5):544–54. doi: 10.1093/cercor/4.5.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A, Luthert P, Dean A, Harding B, Janota I, Montgomery M, Rutter M, Lantos P. A clinicopathological study of autism. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 5):889–905. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.5.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbin G, Pollard H, Gaïarsa JL, Ben-Ari Y. Involvement of GABAA receptors in the outgrowth of cultured hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Let. 1993;152(1-2):150–154. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90505-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar TN, Li YX, Tran HT, Ma W, Dunlap V, Scott C, Barker JL. GABA stimulates chemotaxis and chemokinesis of embryonic cortical neurons via calcium-dependent mechanisms. J Neurosci. 1996;16(5):1808–1818. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01808.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt GJ, Fitzgerald CM, Guptill JT, Booker AB, Kemper TL, Bauman ML. Density and distribution of hippocampal neurotransmitter receptors in autism: an autoradiographic study. J. Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31(6):537–543. doi: 10.1023/a:1013238809666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braverman M, Fein D, Lucci D, Waterhouse L. Affect comprehension in children with pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1989;19(2):301–316. doi: 10.1007/BF02211848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Kayal AR, Raol YH, Russek SJ. Alteration of epileptogenesis genes. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6(2):312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton KM, Nacewicz B, Johnstone T, Schaefer HS, Gernsbacher M, Goldsmith HH, Alexander A, Davidson RJ. Gaze fixation and the neural circuitry of face processing in autism. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(4):519–526. doi: 10.1038/nn1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S, Bishop D, Manstead AS, Tantam D. Face perception in children with autism and Asperger’s syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 1994;35(6):1033–1057. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farroni T, Menon E, Johnson MH. Factors influencing newborns’ preference for faces with eye contact. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2006;95(4):298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Halt AR, Stary JM, Kanodia R, Schulz SC, Realmuto GR. Glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 and 67 kDa proteins are reduced in autistic parietal and cerebellar cortices. Biol. Psychiatry. 2002;52(8):805–810. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, Thuras PD. GABA(A) receptor downregulation in brains of subjects with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(2):223–230. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0646-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink GR, Markowitsch HJ, Reinkemeier M, Bruckbauer T, Kessler J, Heiss WD. Cerebral representation of one’s own past: neural networks involved in autobiographical memory. J. Neurosci. 1996;16(13):4275–4282. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04275.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilby KL, Da Silva AG, McIntyre DC. Differential GABA(A) subunit expression following status epilepticus in seizure-prone and seizure-resistant rats: a putative mechanism for refractory drug response. Epilepsia. 2005;46(Suppl 5):3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.01001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS, Selemon LD, Schwartz ML. Dual pathways connecting the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex with the hippocampal formation and parahippocampal cortex in the rhesus monkey. Neuroscience. 1984;12:719–743. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guptill JT, Booker AB, Gibbs TT, Kemper TL, Bauman ML, Blatt GJ. [3H]-flunitrazepam-labeled benzodiazepine binding sites in the hippocampal formation in autism: a multiple concentration autoradiographic study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(5):911–920. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Hoffman EA, Gobbini MI. The distributed human neural system for face perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2000;4(6):223–233. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata S, Fuwa K, Sugama K, Kusunoki K, Fujita S. Facial perception of conspecifics: chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) preferentially attend to proper orientation and open eyes. Animal Cognition. 2010;13(5):679–88. doi: 10.1007/s10071-010-0316-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson RP, Ouston J, Lee A. Emotion recognition in autism: coordinating faces and voices. Psychol Med. 1988;18(4):911–923. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700009843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubl D, Bölte S, Feineis-Matthews S, Lanfermann H, Federspiel A, Strik W, Poustka F, Dierks T. Functional imbalance of visual pathways indicates alternative face processing strategies in autism. Neurology. 2003;61(9):1232–1237. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000091862.22033.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussman JP. Suppressed GABAergic inhibition as a common factor in suspected etiologies of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31(2):247–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1010715619091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishai A, Ungerleider LG, Martin A, Haxby JV. The representation of objects in the human occipital and temporal cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2000;12(Suppl 2):35–51. doi: 10.1162/089892900564055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph RM, Tanaka J. Holistic and part-based face recognition in children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2003;44(4):529–542. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun MM. The fusiform face area: a module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. The J. Neurosci. 1997;17(11):4302–4311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04302.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper TL, Bauman ML. The contribution of neuropathologic studies to the understanding of autism. Neurol Clin. 1993;11(1):175–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klin A, Sparrow SS, de Bildt A, Cicchetti DV, Cohen DJ, Volkmar FR. A normed study of face recognition in autism and related disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1999;29(6):499–508. doi: 10.1023/a:1022299920240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornhuber J, Mack-Burkhardt F, Konradi C, Fritze J, Riederer P. Effect of antemortem and postmortem factors on [3H]MK-801 binding in the human brain: transient elevation during early childhood. Life Sci. 1989;45(8):745–749. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Kraus A, Wu J, Huguenard JR, Fisher RS. Selective changes in thalamic and cortical GABAA receptor subunits in a model of acquired absence epilepsy in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2006;51(1):121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoTurco JJ, Owens DF, Heath MJ, Davis MB, Kriegstein AR. GABA and glutamate depolarize cortical progenitor cells and inhibit DNA synthesis. Neuron. 1995;15(6):1287–1298. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loup F, Wieser HG, Yonekawa Y, Aguzzi A, Fritschy JM. Selective alterations in GABAA receptor subtypes in human temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 2000;20(14):5401–5419. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05401.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loup F, Picard F, André VM, Kehrli P, Yonekawa Y, Wieser H, Fritschy JM. Altered expression of alpha3-containing GABAA receptors in the neocortex of patients with focal epilepsy. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 12):3277–3289. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma DQ, Whitehead PL, Menold MM, Martin ER, Ashley-Koch AE, Mei H, Ritchie MD, Delong GR, Abramson RK, Wright HH, Cuccaro ML, Hussman JP, Gilbert JR, Pericak-Vance MA. Identification of significant association and gene-gene interaction of GABA receptor subunit genes in autism. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;77(3):377–388. doi: 10.1086/433195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddock RJ, Garrett AS, Buonocore MH. Remembering familiar people: the posterior cingulate cortex and autobiographical memory retrieval. Neuroscience. 2001;104(3):667–676. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA. The retrosplenial contribution to human navigation: a review of lesion and neuroimaging findings. Scandanavial Journal of Psychology. 2001;42:225–238. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty S, Berninger B, Carroll P, Thoenen H. GABAergic stimulation regulates the phenotype of hippocampal interneurons through the regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuron. 1996;16(3):565–570. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS, Liotti M, Brannan SK, McGinnis S, Mahurin RK, Jerabek PA, et al. Reciprocal limbic-cortical function and negative mood: converging PET findings in depression and normal sadness. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(5):675–682. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald B, Highley JR, Walker MA, Herron BM, Cooper SJ, Esiri MM, Crow TJ. Anomalous asymmetry of fusiform and parahippocampal gyrus gray matter in schizophrenia: A postmortem study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2000;157(1):40–47. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R, Petrides M, Pandya DN. Architecture and connections of retrosplenial area 30 in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11:2506–2518. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatani J, Tamada K, Hatanaka F, Ise S, Ohta H, Inoue K, Tomonaga S, Watanabe Y, Chung YJ, Banerjee R, Iwamoto K, Kato T, Okazawa M, Yamauchi K, Tanda K, Takao K, Miyakawa T, Bradley A, Takumi T. Abnormal behavior in a chromosome-engineered mouse model for human 15q11-13 duplication seen in autism. Cell. 2009;137(7):1235–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oblak A, Gibbs TT, Blatt GJ. Decreased GABAA receptors and benzodiazepine binding sites in the anterior cingulate cortex in autism. Aut Res. 2009;2(4):205–219. doi: 10.1002/aur.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson CR, Musil SY. Posterior cingulate cortex: sensory and oculomotor properties of single neurons in behaving cat. Cerebral Cortex (New York, N.Y. 1992;2(6):485–502. doi: 10.1093/cercor/2.6.485. 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson CR, Musil SY, Goldberg ME. Single neurons in posterior cingulate cortex of behaving macaque: eye movement signals. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;76(5):3285–3300. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.5.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson I, Steffenburg S, Gillberg C. Epilepsy in autism and autisticlike conditions. A population-based study. Arch. Neurol. 1988;45(6):666–668. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520300086024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K, Müller RA, Ambrose J, Allen G, Courchesne E. Face processing occurs outside the fusiform ‘face area’ in autism: evidence from functional MRI. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 10):2059–2073. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.10.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K, Haist F, Sedaghat F, Courchesne E. The brain response to personally familiar faces in autism: findings of fusiform activity and beyond. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 12):2703–2716. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond GV, Bauman ML, Kemper TL. Hippocampus in autism: a Golgi analysis. Acta Neuropathologica. 1996;91(1):117–119. doi: 10.1007/s004010050401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein JL, Merzenich MM. Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav. 2003;2(5):255–267. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183x.2003.00037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudge P, Warrington EK. Selective impairment of memory and visual perception in splenial tumours. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 1B):349–360. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.1.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroer RJ, Phelan MC, Michaelis RC, Crawford EC, Skinner SA, Cuccaro M, Simensen RJ, Bishop J, Skinner C, Fender D, Stevenson RE. Autism and maternally derived aberrations of chromosome 15q. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998;76(4):327–336. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980401)76:4<327::aid-ajmg8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz RT, Gauthier I, Klin A, Fulbright RK, Anderson AW, Volkmar F, Skudlarski P, Lacadie C, Cohen DJ, Gore JC. Abnormal ventral temporal cortical activity during face discrimination among individuals with autism and Asperger syndrome. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2000;57(4):331–340. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz RT. Developmental deficits in social perception in autism: the role of the amygdala and fusiform face area. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2005;23(2-3):125–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NJ, Marshall JC, Zafiris O, Schwab A, Zilles K, Markowitsch HJ. The neural correlates of person familiarity. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study with clinical implications. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 4):804–815. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.4.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W. GABAA receptors: ligand-gated Cl- ion channels modulated by multiple drug-binding sites. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1992;13(12):446–450. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90142-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigman M, Mundy P, Sherman T, Ungerer J. Social interactions of autistic, mentally retarded and normal children and their caregivers. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 1986;27(5):647–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1986.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms ML, Kemper TL, Timbie CM, Bauman ML, Blatt GJ. The anterior cingulate cortex in autism: heterogeneity of qualitative and quantitative cytoarchitectonic features suggests possible subgroups. Acta Neuropathologica. 2009;118(5):673–684. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt BA, Pandya DN. Cingulate cortex of the rhesus monkey: II. Cortical Afferents. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1987;262(2):271–279. doi: 10.1002/cne.902620208. DN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt BA, Nimchinsky EA, Vogt LJ, Hof PR. Human cingulate cortex: surface features, flat maps, and cytoarchitecture. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;359(3):490–506. doi: 10.1002/cne.903590310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt BA, Vogt L, Farber NB, Bush G. Architecture and neurocytology of monkey cingulate gyrus. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2005;485(3):218–239. doi: 10.1002/cne.20512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt BA, Vogt L, Laureys S. Cytology and functionally correlated circuits of human posterior cingulate areas. NeuroImage. 2006;29(2):452–466. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar FR, Nelson DS. Seizure disorders in autism. J. Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29(1):127–129. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199001000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Economo C, Koskinas GN. Atlas of the cytoarchitectonics of the human brain. Karger; Basel, Switzerland: 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Yip J, Soghomonian JJ, Blatt GJ. Decreased GAD65 mRNA levels in select subpopulations of neurons in the cerebellar dentate nuclei in autism: an in situ hybridization study. Aut Res. 2009;2(1):50–59. doi: 10.1002/aur.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip J, Soghomonian J, Blatt GJ. Decreased GAD67 mRNA levels in cerebellar Purkinje cells in autism: pathophysiological implications. Acta Neuropathologica. 2007;113(5):559–568. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip J, Soghomonian J, Blatt GJ. Increased GAD67 mRNA expression in cerebellar interneurons in autism: implications for Purkinje cell dysfunction. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008;86(3):525–530. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.