Abstract

A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping method for Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium was developed using the “Minimum SNPs” program. SNP sets were interrogated using allele-specific real-time PCR. SNP typing subdivided clonal complexes 2 and 9 of E. faecalis and 17 of E. faecium, members of which cause the majority of nosocomial infections globally.

Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis cause 80 to 90% of human enterococcal infections (9). The genetic subset of E. faecium named clonal complex 17 (CC17) seems to be responsible for the worldwide emergence of nosocomial infections by this pathogen (6, 7, 13, 14). CC17 is characterized by quinolone and ampicillin resistance and the presence of a putative pathogenicity island carrying esp and hyl genes (2, 5, 7, 16). As in the case of E. faecium, it is suggested that an adaptation to the hospital environment has occurred in E. faecalis. CC2 and CC9 might be designated high-risk CCs of E. faecalis because they contain members that are vancomycin and gentamicin resistant, produce β-lactamase, and carry pathogenicity islands (3, 6). The characterization and study of the population structure of E. faecalis and E. faecium is important to investigate how nosocomial enterococcal populations are evolving toward a predominance of highly specialized enterococcal genetic subpopulations that are capable of surviving, spreading, and infecting patients with increasing frequencies in the hospital environment. Recent efforts have focused on the development of methods for the characterization of enterococci (1, 15-19); however, there is a need to develop and apply new robust, rapid, and cost-effective techniques which are likely to yield more definitive results.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) has emerged as a powerful tool for determining the population structure of many bacterial pathogens (4, 8, 13, 14). In the case of enterococci, Homan et al. (4) concluded that MLST is an appropriate technique to establish an unambiguous international database of E. faecium genetic lineages; however, MLST is impractical for routine monitoring of E. faecalis and E. faecium outside major research facilities (10). To overcome this shortcoming, the use of informative single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) has been described as a cost-effective alternative to full MLST characterization (12). Currently, MLST costs around AUD$91.00 per strain, compared to AUD$7.00 per strain for our SNP profiling method, a considerable cost saving. Previous studies have demonstrated that a small number of SNPs derived from the MLST database can be used to define bacterial populations, including Staphylococcus aureus (4), Neisseria meningitidis (12), and Campylobacter jejuni (11). The aim of this study was to develop an SNP-based genotyping method to study the population structure of clinical isolates of E. faecalis and E. faecium from South East Queensland.

E. faecalis and E. faecium isolates sourced from clinical samples were obtained from Pathology Queensland and the QUT culture collection and were confirmed as either E. faecalis or E. faecium by performing real-time PCR to detect the ddlE. faecalis and ddlE. faecium genes. The primers used were 5′CAAACTGTTGGCATTCCACAA3′ and 5′TGGATTTCCTTTCCAGTCACTTC3′ (E. faecalis forward and reverse primers, respectively) and 5′GAAGAGCTGCTGCAAAATGCTTTAGC3′ and 5′GCGCGCTTCAATTCCTTGT3′ (E. faecium forward and reverse primers, respectively) (F. Huygens, unpublished data). E. faecalis ATCC 19433 and E. faecium ATCC 27270 strains were used for method development. The Corbett X-tractor Gene automated DNA extraction system was used to extract DNA from all cultured isolates (Corbett Robotics, Australia) using the Core protocol no. 141404 version 02. Informative SNP sets that provide a high Simpson's diversity index (D) value (12) were identified for E. faecalis and E. faecium using the software program “Minimum SNPs,” which has been described in detail elsewhere (12). Allele sequences and corresponding sequence types (STs) from the E. faecalis (http://efaecalis.mlst.net/) and E. faecium (http://efaecium.mlst.net/) MLST databases were used as input data for the Minimum SNPs software. An allele-specific real-time PCR (AS kinetic PCR) methodology was developed to interrogate these high-D-value SNPs. The allele-specific primers, designed using Primer Express 2.0 (Applied BioSystems), are listed in Table 1. Each AS kinetic PCR mixture contained 2 μl of DNA and 8 μl of reaction master mix containing 5 μl of 2× SYBR green PCR master mix (Invitrogen, Australia) and 0.125 μl of reverse and forward primers (0.5 μM final concentration). The cycling conditions were as follows: 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 60 s and a melting stage of 60°C to 90°C (RotorGene 6000; Corbett Robotics, now Qiagen). The kinetic PCR results for the xpt198, aroE355, gdh165, gyd208, gki141, and pstS390 SNPs of E. faecalis and the purK115, atpA314, and purK217 SNPs of E. faecium gave sufficiently large differences in cycle threshold (ΔCT) values to provide a clear distinction between the matched and mismatched reactions. The primers for gyd268 and pstS87 of E. faecalis and pstS452, atpA485, gyd160, pstS87, and atpA188 of E. faecium were redesigned with a subterminal mismatched nucleotide at the 3′ end of the primer to improve the allele specificity by increasing the ΔCT between the matched and the mismatched primers while having little or no effect on CT values for the matched primers. The likely reason for this effect is that the mismatch lowers the melting point of the target-primer duplex, thus reducing the probability that the primer site will be occupied at any given time point during the annealing step.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for the interrogation of high-D-value SNPs in E. faecalis and E. faecium

| Species and SNP | Cumulative D value | Primera | Primer sequence (5′-3′)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. faecalis | |||

| gyd268 | 0.5034 | gyd268GF | GACAAAGAAGTTACTGTTGATGAAGTG |

| gyd268AF | GACAAAGAAGTTACTGTTGATGAAGTA | ||

| gyd268R | CTACGATATCAGAAGAAACGATTTCG | ||

| xpt198c | 0.7536 | xpt198GR | AAATGAATAAACTGAAGCCGTTAAG |

| xpt198AR | AAATGAATAAACTGAAGCYGTTAAA | ||

| xpt198F | CTTCGCKCGTAAGGCAAAAAGT | ||

| aroE355c | 0.8766 | aroE355GR | TGGGATTATAAATAGCATCATACACG |

| aroE355AR | TGGGATTATAAATAGCATCATACACA | ||

| aroE355F | CCACATGCRCATAGTAGTCCTATAGAAAA | ||

| gdh165 | 0.9386 | gdh165AF | CAGCCTATCGTGATGAACCA |

| gdh165GF | CAGCCTATCGTGATGAACCG | ||

| gdh165R | CGCCAGACCAACGGAAAT | ||

| gyd208 | 0.9682 | gyd208AF | GCTCAACGTGTTCCTGTAGCA |

| gyd208TF | GCTCAACGTGTTCCTGTAGCT | ||

| gyd208R | CCATTACTGCATTYACTTCATCAAC | ||

| gki141c | 0.9824 | gki141TR | TTCCCCCGCGCCT |

| gki141CR | TTCCCCCGCGCCC | ||

| gki141F | TTCCGTTTGCHTTAGATAATGATG | ||

| pstS87c | 0.9886 | psts87GR | GACCACTGGTCCCATACCG |

| psts87AR | GACCACTGGTCCCATACCA | ||

| psts87F | CGTGGATGCCTCTAAATTAGTYGA | ||

| pstS390c | 0.992 | pstS390GR | CATCAATGCTTAAGGCAACG |

| pstS390AR | CATCAATGCTTAAGGCAACA | ||

| pstS390F | CAGTTCGTAAAATTGTTGAACAAACA | ||

| E. faecium | |||

| pstS452c | 0.3888 | pstS452CR | GTGTACATATGTTCATATGACCAGATTC |

| pstS452TR | GTGTACATATGTTCATAKGACCAGATTT | ||

| pstS452F | TCGACGGTGTAGAACCAAAAGA | ||

| atpA485c | 0.6456 | atpA485CR | CAGCATATGGTGCGATATAAAGC |

| atpA485TR | CAGCATATGGTGCGATATAAAGT | ||

| atpA485F | ACATTGAAAAAATATGGCGCAAT | ||

| gyd160c | 0.7359 | gyd160GR | CCGTCTAATTTACCGTTCAATTCG |

| gyd160TR | CCGTCTAATTTACCGTTCAATTCT | ||

| gyd160AR | CCGTCTAATTTACCRTTCAATTCA | ||

| gyd160F | GCAAACATCGTWCCTAACTCAACW | ||

| purK115 | 0.8276 | purK115TF | AGAAAAATCTTTTTTGGAAACGAAT |

| purK115CF | RGAAAAATCTTTTTTGGAAACGAAC | ||

| purK115R | GATCCCGTCAATCGCATCTT | ||

| pstS87 | 0.8782 | pstS87CF | GTGGATCATAAAGTAGCAGTGGTC |

| pstS87TF | GTGGATCATAAAGTAGCAGTRGTT | ||

| pstS87R | GTAAAGATATCAATCAATTCCTGTTTKG | ||

| atpA314 | 0.9122 | atpA314CF | CCGTAAAACAGGGAAAACTTCC |

| atpA314TF | CCGTAAAACAGGGAAAACTTCT | ||

| atpA314R | GATCATATCTTGRCCTTTTTGGTTRA | ||

| atpA188c | 0.9373 | atpA188GR | GTTAACAGATTTACGTTGCATAACG |

| atpA188AR | GTTAACAGATTTACGTTGCATAACA | ||

| atpA188F | AATYGACGGACTAGGTGAAATCG | ||

| purK217c | 0.9509 | purK217AR | CCCTTGCCATCATAGCCA |

| purK217GR | CCYTTGCCATCATARCCG | ||

| purK217F | GATCGTCAGTCCGACRGATATC |

F, forward primer; R, reverse primer.

The allele-specific primers are indicated with a nucleotide base in boldface at the 3′ end of the sequence. Key to symbols: H = A+T+C, K = G+T, R = A+G, W = A+T, Y = C+T.

The SNP is in the reverse primer.

Isolate-specific SNP profiles were generated, consisting of the polymorphism present at each of the SNP positions. SNP profiles were determined for 55 E. faecalis isolates and 30 E. faecium isolates (Tables 2 and 3). The SNP profiles were assigned to either STs or CCs. Amounts of between 18 and 30 ng of template DNA from randomly chosen isolates of E. faecalis and E. faecium were sequenced to validate the SNPs as described previously (17). The SNP profiles for 160 E. faecalis STs and 414 E. faecium STs (listed on the MLST database) were determined in silico. The nucleotides present at the SNP positions were manually determined for all the STs to determine the in silico SNP profile. The web-based eBURST (Based Upon Related Sequence Types) algorithm was used to aid the visualization of the relationship between high-D-value SNP profiles and MLST sequence types generated for E. faecalis and E. faecium isolates.

TABLE 2.

SNP profiles of E. faecalis isolates

| No. of isolates with profile or straina | Polymorphism at SNP: |

SNP profile | ST(s) in MLST | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, gyd268 | 2, xpt198 | 3, aroE355 | 4, gdh165 | 5, gyd208 | 6, gki141 | 7, pstS87 | 8, pstS390 | |||

| 1 | A | C | C | A | A | G | T | C | ACCAAGTC | ST41, ST146, ST216, ST219, ST239 |

| 2 | A | C | C | A | T | G | T | T | ACCATGTT | ST44, ST189 |

| 1 | A | C | C | G | A | A | T | C | ACCGAATC | ST62, ST85 |

| 1 | A | C | C | G | T | G | T | T | ACCGTGTT | ST113 |

| 1 | A | C | T | A | A | G | T | T | ACTAAGTT | Newb |

| 1 | A | C | T | A | T | G | C | C | ACTATGCC | ST79, ST82 |

| 2 | A | C | T | G | A | A | C | C | ACTGAACC | ST138 |

| 2 | A | C | T | G | T | A | T | C | ACTGTATC | ST40, ST114, ST148, ST198 |

| 1 | A | T | C | A | A | A | C | C | ATCAAACC | ST5, ST21, ST46, ST50, ST70 |

| 1 | A | T | C | A | A | A | C | C | ATCAAACC | ST145, ST152, ST157 |

| 7 | A | T | T | A | A | G | C | T | ATTAAGCT | ST6, ST139, ST181, ST183, ST241 |

| 1 | A | T | T | A | T | G | C | C | ATTATGCC | ST170 |

| 1 | A | T | T | G | A | G | C | T | ATTGAGCT | New |

| 1 | G | C | C | A | A | A | C | C | GCCAAACC | ST186, ST192 |

| 2 | G | C | C | A | T | A | T | T | GCCATATT | ST19, ST20, ST120 |

| 1 | G | C | C | A | T | G | C | C | GCCATGCC | New |

| 1 | G | C | C | G | A | A | T | C | GCCGAATC | ST30, ST56, ST217 |

| 1 | G | C | C | G | T | A | T | T | GCCGTATT | New |

| 17 | G | C | T | G | A | A | C | C | GCTGAACC | ST16, ST66, ST67 |

| 4 | G | C | T | G | A | A | T | C | GCTGAATC | ST26, ST60, ST209, ST214 |

| 1 | G | T | C | G | T | G | T | T | GTCGTGTT | ST36, ST118, ST180 |

| 1 | G | T | T | G | A | A | C | C | GTTGAACC | ST95, ST179 |

| 1 | G | T | T | G | A | G | T | C | GTTGAGTC | ST64, ST101, ST161, ST205 |

| TX2486 | A | T | T | G | A | A | C | T | ATTGAACT | ST2 |

| TX2708 | A | T | T | A | A | G | C | T | ATTAAGCT | ST6 |

| TX0630 | A | T | C | A | T | A | C | T | ATCATACT | ST9 |

| ΔCT value (mean ± SDc) of: | ||||||||||

| A | 6.97 ± 0.37 | NAb | NA | 2.02 ± 0.20 | 7.42 ± 0.54 | 8.88 ± 0.37 | NA | NA | ||

| C | NA | 4.36 ± 0.27 | 3.32 ± 0.47 | NA | NA | NA | 9.77 ± 0.78 | 2.49 ± 0.38 | ||

| G | 3.51 ± 0.38 | NA | NA | 3.69 ± 0.44 | NA | 7.73 ± 0.29 | NA | NA | ||

| T | NA | 2.61 ± 0.18 | 1.48 ± 0.30 | NA | 9.43 ± 0.63 | NA | 9.74 ± 0.92 | 2.2 ± 0.31 | ||

Strains were obtained from University of Texas and are fully MLST characterized.

New, STs not found in MLST database; NA, not applicable.

From pooled results for each polymorphism.

TABLE 3.

SNP profiles of E. faecium isolates

| No. of isolates with profile | Polymorphism at SNP: |

SNP profile | ST(s) in MLST | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, pstS452 | 2, atpA485 | 3, gyd160 | 4, purK115 | 5, pstS87 | 6, atpA314 | 7, atpA188 | 8, purk217 | |||

| 1 | A | A | C | C | C | T | T | C | AACCCTTC | Newa |

| 1 | A | G | A | C | C | C | T | C | AGACCCTC | New |

| 2 | A | G | A | T | C | T | C | C | AGATCTCC | New |

| 1 | A | G | A | T | C | T | T | C | AGATCTTC | New |

| 1 | A | G | C | C | T | T | T | C | AGCCTTTC | New |

| 3 | A | G | C | T | C | T | C | C | AGCTCTCC | ST260, ST262, ST273, ST322 |

| 1 | A | G | T | C | T | T | T | C | AGTCTTTC | ST60, ST61, ST74, ST75, ST76, ST85, ST94, ST96, ST152, ST178, ST213, ST218, ST225, ST289, ST329, ST334, ST346, ST352, ST356, ST361 |

| 2 | G | A | C | T | C | T | T | C | GACTCTTC | ST227, ST230, ST313, ST316 |

| 5 | G | A | T | T | C | T | T | C | GATTCTTC | ST78, ST145, ST201, ST203, ST204, ST249, ST283, ST287, ST288, ST304, ST323, ST339, ST341, ST365, ST393, ST414 |

| 1 | G | G | C | C | C | C | C | C | GGCCCCCC | New |

| 2 | G | G | C | C | C | T | C | C | GGCCCTCC | ST162 |

| 6 | G | G | C | T | C | C | C | C | GGCTCCCC | ST267, ST349 |

| 2 | G | G | C | T | C | T | C | C | GGCTCTCC | ST18, ST125, ST132, ST173, ST186, ST275, ST276, ST282, ST302, ST305, ST319, ST336, ST340, ST344, ST351, ST368, ST380, ST388, ST391, ST409 |

| 2 | G | G | T | T | C | C | C | C | GGTTCCCC | ST16, ST17, ST31, ST63, ST65, ST103, ST168, ST174, ST180, ST187, ST206, ST208, ST209, ST233, ST234, ST252, ST280, ST290, ST294, ST295, ST300, ST306, ST307, ST308, ST360, ST371, ST389, ST390, ST415 |

| ΔCT value (mean ± SDb) of: | ||||||||||

| A | 7 ± 0.57 | 13.07 ± 0.65 | 14.14 | NAc | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| C | NA | NA | 19.5 ± 0.35 | 7.78 ± 0.07 | 5.49 ± 0.33 | 4.24 ± 0.59 | 15.84 ± 0.53 | 3.04 ± 0.14 | ||

| G | 10.78 ± 0.44 | 14.14 ± 0.25 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| T | NA | NA | 18.69 ± 0.18 | 7.72 ± 0.35 | 12.68 ± 0.17 | 5.02 ± 0.57 | 9.51 ± 1.1 | 1.58 ± 0.29 | ||

New, STs not found in MLST database.

From pooled results for each polymorphism.

NA, not applicable.

The relationship between the SNP profile of each isolate and the MLST-defined population structure was determined for both E. faecalis and E. faecium isolates, using the MLST database and the “working backwards” mode of the Minimum SNPs program. Twenty-one and 19 SNP profiles were identified for E. faecalis and E. faecium isolates, respectively. A number of SNP profiles were new, and these isolates are likely to be new STs that warrant further characterization. The most dominant SNP profile for E. faecalis clinical isolates was GCTGAACC (corresponding to STs 16, 66, and 67), which is shared by 17 isolates in our collection. SNP profile GGCTCCCC (corresponding to STs 267 and 349) is the dominant profile for E. faecium, which is shared by six isolates in our collection.

One hundred sixty STs (350 isolates) of E. faecalis and 414 STs (1,319 isolates) of E. faecium were subjected to in silico analysis of the high-D-value SNPs. The 160 E. faecalis STs were resolved into 86 SNP profiles. The 414 E. faecium STs were subdivided into 55 SNP profiles. The SNP profiles of all STs listed in the MLST database are shown in the supplemental material.

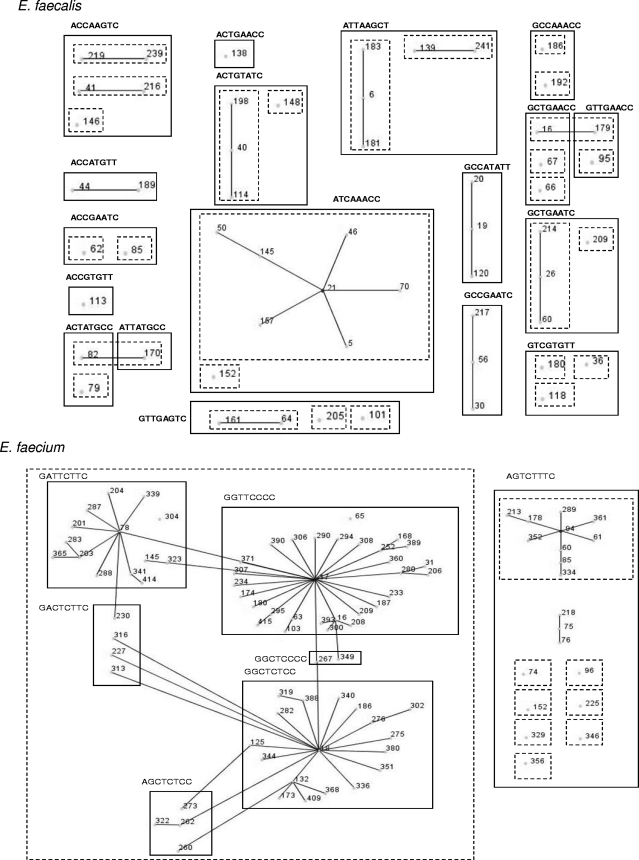

eBURST analysis of all STs was correlated with the SNP profiles of E. faecalis and E. faecium (Fig. 1). The STs of the major E. faecalis clonal complex CC21 were found to share the same SNP profile, ATCAAACC. The most prevalent ST in MLST, ST 16, has the GCTGAACC SNP profile. Previous studies of the E. faecalis population structure have found that CC2 contains STs 6, 2, and 51 and CC9 contains STs 9, 17, 18, 42, and 52 and that these CCs were associated almost exclusively with hospital-derived isolates (6). In contrast, our study found that none of the clinical isolates belonged to either CC2 or CC9. To date, members of CC2 and CC9 have not been documented in Australia. In silico SNP analysis of the MLST STs, together with the in vitro SNP profiling of ST 2, ST 6, and ST 9 strains (obtained from the University of Texas) (Table 2), revealed that CC9 and CC2 can be subdivided by using the SNP method. For these CCs, SNP typing is able to further discriminate between STs in the same clonal complex, indicating that it is ideally suited to further discriminate very closely related STs. The 91 E. faecium STs were grouped into seven SNP profiles. Based on MLST typing, a distinct high-risk enterococcal clonal complex, CC17, can be differentiated. This CC is associated with the majority of hospital outbreaks and clinical infections on five continents (6, 13). Recently, genetic population studies have shown that the majority of vancomycin-resistant E. faecium strains associated with nosocomial infections worldwide are part of the same CC17. The eight high-D-value SNPs were able to further differentiate this major CC17 into 6 SNP profiles. The SNP profile with the most STs (29 in total) had the GGTTCCCC profile. This subdivision of CC17 can be useful in investigating the association of these STs with specific disease profiles, something that MLST is unable to perform, as all these STs are grouped into the same clonal complex by MLST.

FIG. 1.

An eBURST population snapshot of 51 E. faecalis STs grouped into 18 SNP profiles and 27 E. faecium STs grouped into 7 SNP profiles. The dotted-line boxes represent clonal complexes as defined by the E. faecalis and E. faecium MLST databases; the solid-line boxes represent STs grouped according to their corresponding 8-nucleotide high-D-value SNP profiles. Single local variants are connected by solid lines.

The Simpson's index of diversity (D value) was calculated for both E. faecalis and E. faecium to determine the comparative discriminatory powers of MLST and SNP typing. An important finding was that there was little difference in resolving power between MLST and SNP typing either for E. faecalis isolates (MLST D = 0.97 and SNP D = 0.96) or for E. faecium isolates (MLST D = 0.96 and SNP D = 0.91). This finding clearly demonstrates that the high discriminatory power of the SNP genotyping method is as good as that of MLST.

In conclusion, we have developed a novel and widely applicable approach for the typing of E. faecalis and E. faecium isolates that has a high discriminatory power and can be applied to the investigation of nosocomial enterococcal outbreaks. SNP typing subdivided isolates of clonal complexes 2 and 9 of E. faecalis and 17 of E. faecium, members of which are known to be the major causative agents of nosocomial infections globally. This method represents an efficient means of classifying E. faecalis and E. faecium isolates into groups that are concordant with the population structure of these organisms. These SNPs can be used on their own or combined with other rapidly evolving markers, such as virulence genes and antibiotic resistance genes, to yield highly informative genotyping methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Narelle George (Pathology Queensland) and Sue Gill (Queensland University of Technology) for kindly providing the E. faecalis and E. faecium isolates. We also acknowledge Barbara Murray and Karen Jacques-Palaz (Health Science Center at Houston, University of Texas) for supplying E. faecalis ST 2, 6, and 9 strains.

Irani U. Rathnayake is in receipt of an International Postgraduate Research Scholarship (IPRS), and the study is supported by the Institute of Sustainable Resources, QUT.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 October 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coque, T. M., P. Seetulsingh, K. V. Singh, and B. E. Murray. 1998. Application of molecular techniques to the study of nosocomial infections caused by enterococci, p. 469-493. In N. Woodford and A. Johnson (ed.), Methods in molecular medicine, vol. 15. Molecular bacteriology: protocols and clinical applications. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coque, T. M., R. Willems, R. Canton, R. Del Campo, and F. Baquero. 2002. High occurrence of esp among ampicillin-resistant and vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecium clones from hospitalized patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:1035-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hiraga, N., T. Muratani, S. Naito, and T. Matsumoto. 2008. Genetic analysis of faropenem-resistant Enterococcus faecalis in urinary isolates. J. Antibiot. 61:213-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Homan, W. L., D. Tribe, S. Poznanski, M. Li, G. Hogg, E. Spalburg, J. D. Van Embden, and R. J. Willems. 2002. Multilocus sequence typing scheme for Enterococcus faecium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1963-1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huygens, F., J. Inman-Bamber, G. R. Nimmo, W. Munckhof, J. Schooneveldt, B. Harrison, J. A. McMahon, and P. M. Giffard. 2006. Staphylococcus aureus genotyping using novel real-time PCR formats. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:3712-3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leavis, H. L., M. J. Bonten, and R. J. Willems. 2006. Identification of high-risk enterococcal clonal complexes: global dispersion and antibiotic resistance. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:454-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leavis, H. L., R. J. Willems, J. Top, E. Spalburg, E. M. Mascini, A. C. Fluit, A. Hoepelman, A. J. de Neeling, and M. J. Bonten. 2003. Epidemic and nonepidemic multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:1108-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maiden, M. C. J., J. A. Bygraves, E. Feil, G. Morelli, J. E. Russell, R. Urwin, Q. Zhang, J. Zhou, K. Zurth, D. A. Caugant, I. M. Feavers, M. Achtman, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:3140-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogier, J.-C., and P. Serror. 2008. Safety assessment of dairy microorganisms: the Enterococcus genus. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 126:291-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Persing, D. H., F. C. Tenover, J. Versalovic, Y.-W. Tang, E. R. Unger, D. A. Relman, and T. J. White (ed.). 2004. Molecular microbiology: diagnostic principles and practice. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 11.Price, E. P., V. Thiruvenkataswamy, L. Mickan, L. Unicomb, R. E. Rios, F. Huygens, and P. M. Giffard. 2006. Genotyping of Campylobacter jejuni using seven single-nucleotide polymorphisms in combination with flaA short variable region sequencing. J. Med. Microbiol. 55:1061-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robertson, G. A., V. Thiruvenkataswamy, H. Shilling, E. P. Price, F. Huygens, F. A. Henskens, and P. M. Giffard. 2004. Identification and interrogation of highly informative single nucleotide polymorphism sets defined by bacterial multilocus sequence typing databases. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:35-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Top, J., R. Willems, and M. Bonten. 2008. Emergence of CC17 Enterococcus faecium: from commensal to hospital-adapted pathogen. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 52:297-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valdezate, S., C. Labayru, A. Navarro, M. A. Mantecon, M. Orteqa, T. M. Coque, M. Garcia, and J. A. Saez-Nieto. 2009. Large clonal outbreak of multidrug-resistant CC17 ST17 Enterococcus faecium containing Tn5382 in a Spanish hospital. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63:17-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vos, P., R. Hogers, M. Bleeker, M. Reijans, T. Van De Lee, M. Hornes, A. Frijters, J. Pot, J. Peleman, M. Kuiper, and M. Zabeau. 1995. AFLP: a new concept for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Research. 23:4407-4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willems, R. J., J. Top, M. van Santen, D. A. Robinson, T. M. Coque, F. Baquero, H. Grundmann, and M. J. Bonten. 2005. Global spread of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium from distinct nosocomial genetic complex. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:821-828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodford, N., L. Tysall, C. Auckland, M. W. Stockdale, A. J. Lawson, R. A. Walker, and D. M. Livermore. 2002. Detection of oxazolidinone-resistant Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium strains by real-time PCR and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4298-4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zdragas, A., P. Partheniou, C. Kotzamanidis, L. Psoni, O. Koutita, E. Moraitou, N. Tzanetakis, and M. Yiangou. 2008. Molecular characterisation of low-level vancomycin-resistant enterococci found in coastal water of Thermaikos Gulf, Northern Greece. Water Res. 42:1274-1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu, X., B. Zheng, S. Wang, R. J. L. Willems, F. Xue, X. Cao, Y. Li, S. Bo, and J. Liu. 2009. Molecular characterisation of outbreak-related strains of vancomycin-resistant E. faecium from an intensive care unit in Beijing, China. J. Hosp. Infect. 72:147-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.