Abstract

The yeast type I myosins (MYO3 and MYO5) are involved in endocytosis and in the polarization of the actin cytoskeleton. The tail of these proteins contains a Tail Homology 2 (TH2) domain that constitutes a putative actin-binding site. Because of the important mechanistic implications of a second ATP-independent actin-binding site, we analyzed its functional relevance in vivo. Even though the myosin tail interacts with actin, and this interaction seems functionally important, deletion of a major portion of the TH2 domain did not abolish interaction. In contrast, we found that the SH3 domain of Myo5p significantly contributes to this interaction, implicating other proteins. We found that Vrp1p, the yeast homolog of WIP [Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP)-interacting protein], seems necessary to sustain the Myo5p tail–F-actin interaction. Consistent with recent results implicating the yeast type I myosins in regulating actin polymerization in vivo, we demonstrate that the C-terminal domain of Myo5p is able to induce cytosol-dependent actin polymerization in vitro, and that this activity requires both an intact Myo5p SH3 domain and Vrp1p.

Keywords: ARP2/3/endocytosis/myosin I/Vrp1p/WIP

Introduction

The type I myosins are actin-activated ATPases that bind acidic phospholipids and cellular membranes via a short positively charged tail. This feature suggests a role in membrane dynamics (Pollard et al., 1991; Mooseker and Cheney, 1995). However, demonstration of their involvement in specific tasks has been difficult. Only recently have genetic approaches brought some light to this point (Novak et al., 1995; Geli and Riezman, 1996; Goodson et al., 1996; Jung et al., 1996). MYO3 and MYO5 encode the type I myosins of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Deletion of either gene does not result in any obvious phenotype for growth, whereas a double knockout is synthetically lethal or nearly so, suggesting functional redundancy (Geli and Riezman, 1996; Goodson et al., 1996). The yeast type I myosins are required for the uptake step of endocytosis and the polarization of the actin cytoskeleton (Geli and Riezman, 1996; Goodson et al., 1996). However, the mechanistic basis for their function in these processes is unknown.

Besides the putative membrane-binding domain (TH1), the tails of Myo3p and Myo5p contain two C-terminal domains that are homologous to other members of this protein family: an Ala- and Pro-rich domain (TH2), and a Src Homology domain 3 (SH3 or TH3) (Pollard et al., 1991; Mooseker and Cheney, 1995). SH3 domains are present in a variety of proteins associated with the organization of the actin cytoskeleton and with signal transduction. This domain mediates protein–protein interactions through binding to proline (Pro)-rich stretches (Kuriyan and Cowburn, 1997). The TH2 domain of the protozoal type I myosins binds actin in vitro (Brzeska et al., 1988; Doberstein and Pollard, 1992; Jung and Hammer, 1994; Rosenfeld and Rener, 1994). However, in contrast to the motor-head–actin interaction, ATP does not influence the affinity of the TH2–actin interaction in vitro.

A second ATP-independent actin-binding site on the type I myosins could have important mechanistic implications. It has been suggested that the TH2 domain could serve to recruit type I myosin molecules onto the actin filaments, securing a high local concentration of myosin heads when the actin/myosin ratio is low, and thus it might help to achieve processivity (Albanesi et al., 1985). Alternatively, a second actin-binding site could allow the type I myosins to crosslink and contract actin filaments (Fujisaki et al., 1985; Lynch et al., 1986).

Despite the extensive biochemical characterization of the ATP-independent actomyosin interaction of the protozoal type I myosins, its physiological relevance remains obscure. We decided to use site-directed mutagenesis on MYO5 and a collection of actin alleles (Wertman et al., 1992; Amberg et al., 1995) to investigate whether the ATP-independent actomyosin interaction is functionally relevant. We find that the Myo5p tail binds F-actin in an ATP-independent manner, and that this interaction appears to be functionally important. However, in contrast to what was found for the protozoal type I myosins, the SH3 domain of Myo5p contributes significantly to this ATP-independent actomyosin interaction in vivo, suggesting that the actin binding might not be direct. Furthermore, we find that the yeast homolog of the human WIP [Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP)-interacting protein], Vrp1p (Vaduva et al., 1999), is required to sustain the SH3-dependent Myo5p tail–actin interaction. Consistent with a recently proposed role of the yeast type I myosins in regulating actin polymerization in vivo (Evangelista et al., 2000; Lechler et al., 2000), we find that glutathione–Sepharose beads coated with a fusion protein consisting of glutathione S-transferase (GST) and the C-terminal fragment of Myo5p trigger cytosol-dependent actin polymerization in vitro, and that, strikingly, such activity seems to require both an intact SH3 domain and Vrp1p.

Results

Functionally relevant interaction between Myo5p tail and actin

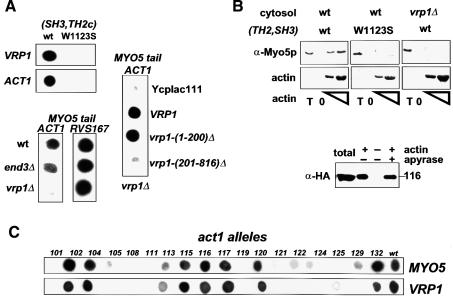

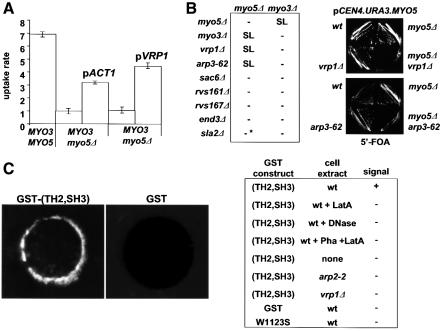

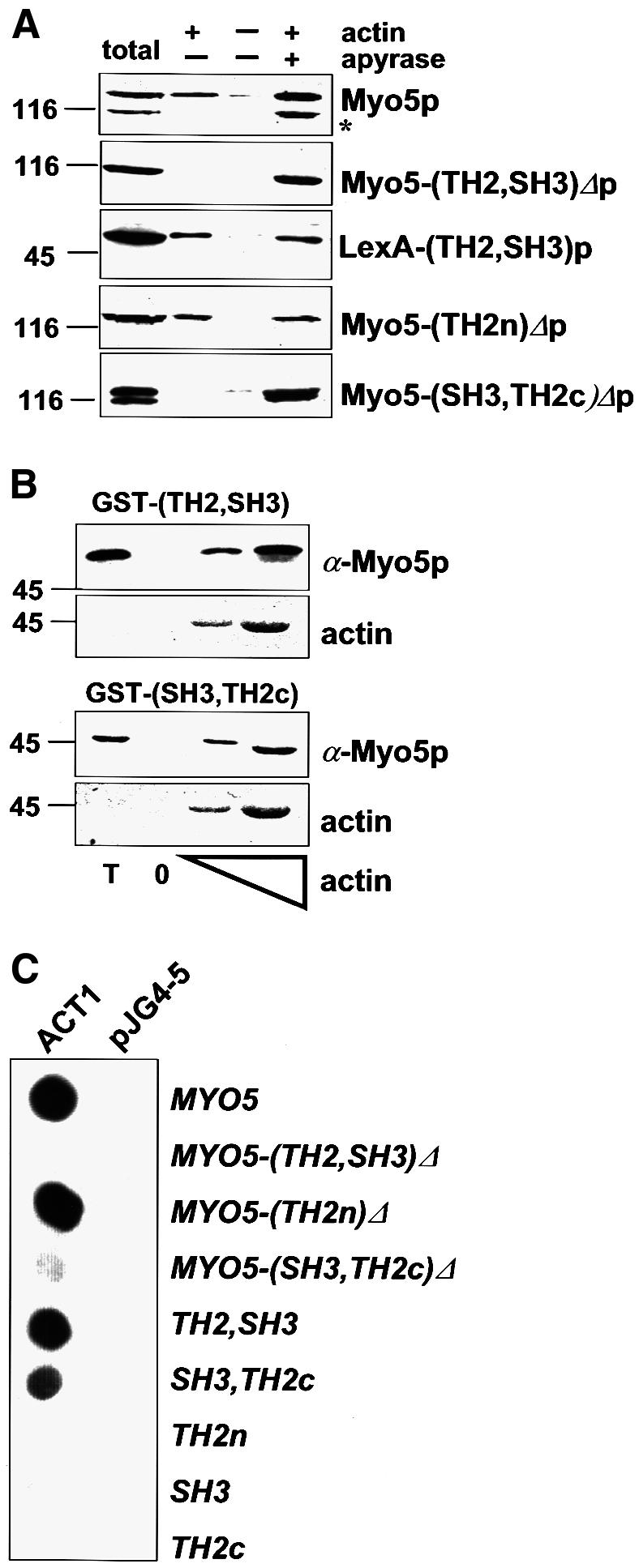

The presence of a TH2 domain in Myo5p (Goodson et al., 1996) suggests that the Myo5p tail bears an ATP-independent actin-binding site. To investigate this possibility we tested the ability of Myo5p (Geli et al., 1998) to pellet with exogenously added F-actin in the presence or absence of ATP. As expected, a significant amount of Myo5p interacted with F-actin in the presence of ATP (Figure 1A). In contrast, a degradation product lacking a C-terminal fragment of ∼25 kDa (Figure 1A, asterisk) failed to pellet with F-actin under these conditions. According to the shift in apparent molecular weight, the missing C-terminal fragment should include the TH2 and the SH3 domains. In agreement, a mutant Myo5p lacking these domains [Myo5-(TH2, SH3)Δp] had an apparent molecular weight similar to that of the Myo5p degradation product (Figure 1A, asterisk) and failed to pellet with F-actin in the presence of ATP (Figure 1A). A LexA fusion protein containing only the TH2 and the SH3 domains of Myo5p interacted with F-actin regardless of the presence or absence of ATP in the buffer [Figure 1A, LexA-(TH2, SH3)]. These results were confirmed using the two-hybrid assay. The MYO5 tail (MYO5) strongly induced transcription of a β-galactosidase reporter gene when tested against actin (ACT1) (Gyuris et al., 1993) (Figure 1C). Truncation of the Myo5p tail immediately upstream of the TH2 domain abolished the interaction [MYO5-(TH2, SH3)Δ], whereas a fragment containing the TH2 and the SH3 domains (TH2, SH3) was sufficient to trigger transcription of the reporter (Figure 1C). In order to investigate whether the Myo5p tail–actin interaction was functionally relevant, we used a subset of the actin alleles from the Wertman collection (Wertman et al., 1992). These actin mutations differentially affect interaction with several actin-binding proteins (Amberg et al., 1995). Since Act1p and Myo5p are required for the internalization step of endocytosis (Kubler and Riezman, 1993; Geli and Riezman, 1996), the α-factor uptake assay (Dulic et al., 1991) can be used to monitor subtle differences in the function of different ACT1 and MYO5 alleles in vivo. Thus, if the Myo5p tail–actin interaction was functionally important for endocytosis, all actin mutations affecting binding to Myo5p should also exhibit defective uptake kinetics. The opposite assertion is not necessarily true since additional actin-binding proteins are necessary for the endocytic uptake. In fact, all mutations that strongly diminished the interaction with the Myo5p tail severely impaired endocytosis (Figure 2A, MYO5). Consistent with this result, the mutant Myo5-(TH2, SH3)Δp, which was unable to pellet with actin in the presence of ATP, was also unable to sustain endocytosis (Figure 2B).

Fig. 1. The Myo5p tail interacts with actin. (A) Cytosolic fractions were prepared from strains bearing integrated versions of wt or mutant myo5 (SCMIG277, SCMIG278, SCMIG279, SCMIG280), or a strain expressing the TH2 and SH3 domains fused to LexA [EGY48 pEG202(TH2, SH3)] in a buffer containing 1 mM ATP. Purified actin (+ actin) or buffer (– actin) were added to the cell extracts. After allowing actin polymerization, one sample containing exogenously added actin was incubated with apyrase to hydrolyze ATP (+ apyrase). F-actin was recovered by centrifugation and the pellet analyzed by immunoblotting. 9E10 was used for detection of Myo5p, and EW/IK for detection of the LexA fusion protein. One quarter of the protein extract utilized per incubation was loaded as total. (B) Recombinant GST fusion proteins [GST–(TH2, SH3) or GST–(SH3, TH2c)] were incubated with cytosolic fractions of a wt strain (RH3975) and increasing concentrations of G-actin. After allowing actin polymerization, F-actin was recovered by centrifugation and the pellets were analyzed for the presence of the recombinant proteins by immunoblotting using the EW/IK antibody. The increasing amounts of actin in the pellet were monitored by Ponceau Red staining. The same amount of GST fusion proteins used per assay were loaded as total (T). (C) Different MYO5 tail fragments [pEG202MYO5, pEG202 myo5-(TH2, SH3)Δ, pEG202 myo5-(TH2n)Δ, pEG202 myo5-(SH3, TH2c)Δ, pEG202(TH2, SH3), pEG202(SH3, TH2c), pEG202(TH2n), pEG202(SH3), pEG202(TH2c)] were tested versus ACT1 (pJG4-5ACT1), or versus the B42 transcriptional activator (pJG4-5) as a control, in the two-hybrid assay on X-Gal-containing plates.

Fig. 2. The Myo5p tail–actin interaction is functionally relevant. (A) The indicated MYO5 tail fragments or END3 (as control) [pEG202MYO5, pEG202(TH2, SH3), pEG202 (SH3, TH2c), pEG202END3] were tested versus the indicated ACT1 alleles (pJG4-5act1-x) in the two-hybrid X-Gal-containing plate assay. The same actin mutants were tested for their ability to sustain endocytosis in vivo. The percentage of cell-bound α-factor internalized/min is indicated. (B) myo3Δ strains bearing integrated myc-tagged wt or mutant MYO5 (SCMIG277, SCMIG278, SCMIG279, SCMIG280) were tested for α-factor internalization. The percentage of cell-bound α-factor internalized/min is indicated. The expression level of the integrated proteins (lower panel) was monitored by immunoblotting. 9E10 was used for detection of wt and mutant Myo5p (lanes 1–4). C4 was used for detection of actin as internal reference.

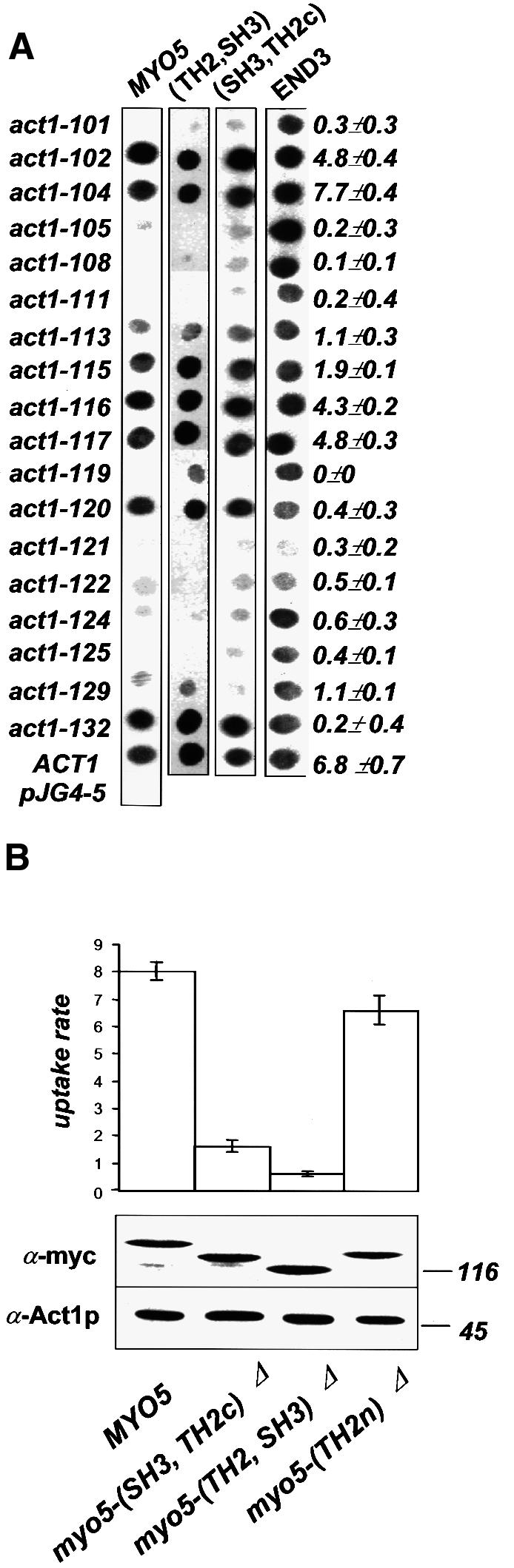

The SH3 of Myo5p contributes to the functionally relevant Myo5p tail–actin interaction

The C-terminal fragment of the Myo5p tail, which is necessary and sufficient to mediate the ATP-independent actomyosin interaction, bears both the TH2 and the SH3 domains. The SH3 domain of most protozoal type I myosins is placed at the C-terminus, immediately downstream of the TH2 domain (Mooseker and Cheney, 1995). In contrast, the SH3 domain of Myo5p and Myo3p is inserted within the TH2 domain, which it splits into two regions: an N-terminal region of ∼110 amino acids (TH2n) with >40% of Pro and Ala content; and a C-terminal region of ∼70 amino acids with only half the percentage of Pro and Ala (TH2c). Deletion of the region encoding the TH2n results in a MYO5 allele that can complement the growth defect of a myo3Δ myo5Δ mutant, and does not display any defect in actin polarization, suggesting that this domain is not required for Myo5p function (Anderson et al., 1998). In agreement, we found that the analogous mutant could sustain endocytosis with nearly wild-type kinetics in a myo3Δ background [Figure 2B, myo5-(TH2n)Δ]. Since our data suggested that the Myo5p tail–actin interaction is required to sustain endocytosis, we investigated this further. We found that deletion of the N-terminal portion of the TH2 domain abolished neither the ATP-independent actin-binding of Myo5p in the pelleting assay [Figure 1A, Myo5-(TH2n)Δp], nor the Myo5p tail–actin interaction in the two-hybrid system [Figure 1C, MYO5-(TH2n)Δ]. However, we found that a Myo5p truncated immediately upstream of the SH3 domain no longer pelleted with F-actin in the presence of ATP [Figure 1A, Myo5-(SH3, TH2c)Δp], and that its tail interacted only weakly with actin in the two-hybrid system [Figure 1C, MYO5-(SH3, TH2c)Δ]. Additionally, the C-terminal fragment containing only the SH3 and TH2c domains was able to interact with actin both in the pelleting (Figure 1B) and the two-hybrid assays (Figure 1C). The two-hybrid analysis indicated that both the SH3 and the TH2c domains were necessary to sustain the interaction (Figure 1C). Consistent with the functional significance of the (SH3, TH2c)-mediated Myo5p–actin interaction, truncation of Myo5p immediately upstream of the SH3 domain blocked its ability to sustain endocytosis [Figure 2B, myo5-(SH3, TH2c)Δ]. Additionally, the most C-terminal Myo5p fragment containing the SH3 domain (SH3, TH2c) was sufficient to reproduce the Myo5p tail footprint on actin (Figure 2A).

Vrp1p is required to sustain a physiologically relevant interaction between the Myo5p tail and F-actin

Our data indicate that the SH3 domain of Myo5p might be required to sustain a functionally relevant Myo5p tail–actin interaction. To test this possibility further, we analyzed the effect of a point mutation in a conserved residue of the SH3 domain (W1123S). Consistent with the requirement of the SH3 domain in the functionally relevant Myo5p tail–actin interaction, the W1123S mutation prevented binding of the (SH3, TH2c) fragment to actin in the two-hybrid, and abolished the interaction between a GST fusion protein containing the TH2 and SH3 domains in the pelleting assay (Figure 3B). These results strongly suggest that the SH3 domain is required for the physiologically relevant Myo5p tail–actin interaction.

Fig. 3. Vrp1p is required for the Myo5p tail–actin interaction. (A) Upper left panel: the most C-terminal MYO5 fragment containing the SH3 domain [pEG202 (SH3, TH2c); wt] or the same fragment bearing a point mutation in the SH3 domain (W1223S) was tested versus ACT1 (pJG4-5ACT1) or VRP1 (pJG4-5VRP1) using the two-hybrid assay on X-Gal-containing plates. Lower left panel: the MYO5 tail (pEG202MYO5) was tested versus ACT1 (pJG4-5ACT1) or RVS167 (pJG4-5RVS167) in wt (RH2884) or isogenic end3Δ (SCMIG45) or vrp1Δ (SCMIG48) strains bearing the β-galactosidase reporter gene (pSH18–34). Enzyme activity was monitored on X-Gal-containing plates. Right panel: the MYO5 tail (pEG202MYO5) was tested versus ACT1 (pJG4-5ACT1) in a vrp1Δ (SCMIG48) strain bearing the β-galactosidase reporter gene (pSH18–34), and either an empty plasmid (Ycplac111) or the same plasmid bearing wt or the indicated mutant vrp1 genes. Enzyme activity was monitored on X-Gal-containing plates. (B) Upper panel: recombinant purified GST fusion proteins containing the wt TH2 and SH3 domains [GST–(TH2, SH3), wt] or the same construct bearing the W1223S mutation in the SH3 domain were incubated with cytosolic fractions from wt (RH3975) or vrp1Δ (SCMIG48) strains and increasing concentrations of G-actin. After allowing actin polymerization, F-actin was recovered by centrifugation and the pellets analyzed for the presence of the recombinant fusion proteins by immunoblotting using the EW/IK antibody. The increasing amounts of actin in the pellet were monitored by Ponceau Red staining. The same amounts of GST fusion proteins used per assay were loaded as total (T). Lower panel: a cytosolic fraction from a strain bearing a plasmid with an HA-tagged VRP1 (SCMIG277 p181VRP1HA) was prepared in a buffer containing 1 mM ATP. Either purified G-actin (+ actin) or G buffer (– actin) was added to the cell extracts. After allowing actin polymerization, one of the samples containing actin was incubated with apyrase to hydrolyze ATP (+ apyrase). F-actin was recovered by centrifugation and the pellet analyzed by immunoblotting using the anti-HA antibody. One-quarter of the protein extract utilized per incubation was loaded as total (T). (C) The MYO5 tail (pEG202MYO5) or VRP1 (pEG202VRP1) was tested versus the indicated ACT1 alleles (pJG4-5act1-1x) in the EGY48 strain using the two-hybrid assay on X-Gal-containing plates.

The contribution of the SH3 domain to the Myo5p tail–actin interaction implied that other proteins might be involved. In an effort to identify the cytosolic components required for the Myo5p tail–actin interaction, we tested the need for Vrp1p. Several findings point to a potential role of Vrp1p in this binding event. It was shown that the Myo5p SH3 domain interacts with the proline-rich protein Vrp1p (Anderson et al., 1998). On the other hand, Vrp1p, like Myo5p, is required for the uptake step of endocytosis and the polarization of the actin cytoskeleton (Munn et al., 1995; Vaduva et al., 1997), and it interacts with actin in the two-hybrid system (Vaduva et al., 1997). Additionally, we observed that the W1123S mutation, which prevented binding of the of the Myo5p C-terminal fragment to actin, also abolished interaction of this domain with Vrp1p in the two-hybrid assay (Figure 3A).

In agreement with a requirement of Vrp1p for the Myo5p tail–actin interaction, we observed a strong inhibition of the MYO5/ACT1-induced β-galactosidase transcription in the vrp1Δ strain, when compared with wild-type (wt) cells (Figure 3A). Three criteria indicated that this effect was specific. First, deletion of another protein required for the uptake step of endocytosis and the organization of the actin cytoskeleton did not significantly affect the Myo5p tail–actin interaction (Figure 3A, end3Δ). Secondly, the interaction of the Myo5p tail with another protein appeared unaffected in the vrp1Δ strain (Figure 3A, MYO5-RVS167). Thirdly, N- and C-terminal truncations of VRP1, which were equally unable to complement the growth defect of a vrp1Δ strain at 37°C (Vaduva et al., 1997), differentially restored the two-hybrid Myo5p tail–actin interaction in the vrp1Δ cells. The requirement of Vrp1p for the Myo5p tail–actin interaction was confirmed using the actin pelleting assay. The GST–(SH3, TH2) fusion protein failed to pellet with F-actin when cytosol from a vrp1Δ strain was used in the assay (Figure 3B). Also consistent with a proposed role of Vrp1p in mediating the Myo5p tail–actin interaction, hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Vrp1p was also found in the actin pellet together with Myo5p, regardless of the presence or absence of ATP in the buffer (Figure 3B). To test this hypothesis further, we compared the footprints of Myo5p and Vrp1p on the actin molecule. If Vrp1p was really required to mediate the Myo5p tail–actin interaction, all mutations that diminish Vrp1p–Act1p binding should also impair the interaction of Act1p with the Myo5p tail. As expected, the Myo5p and Vrp1p footprints on actin were strikingly similar (Figure 3C).

An intact SH3 domain and Vrp1p seem to be required for Myo5p-induced localized actin polymerization

Recent results strongly suggest that the yeast type I myosins might be implicated in the regulation of localized actin polymerization in vivo (Evangelista et al., 2000; Lechler et al., 2000). Myo3p and Myo5p physically interact with the Arp2p–Arp3p actin-nucleating complex (Evangelista et al., 2000; Lechler et al., 2000), and they are required for the polarized assembly of cortical actin patches in a semi in vitro assay (Lechler et al., 2000). On the other hand, Vrp1p has also been implicated in the regulation of actin polymerization in vivo. Overexpression of Las17p, the yeast homolog of WASP, suppresses the actin polarization and endocytic defect caused by a temperature-sensitive (ts) allele of VRP1, but not of a null mutation (Naqvi et al., 1998). Las17p interacts with the Arp2p–Arp3p complex and activates its actin-nucleation activity in vitro (Madania et al., 1999; Winter et al., 1999). Additionally, a vrp1Δ strain is hypersensitive to the inhibitor of actin polymerization, latrunculin A, and a vrp1 ts mutant can be suppressed by increasing the intracellular concentration of actin (Vaduva et al., 1997).

We collected further evidence in vivo indicating that Vrp1p and the yeast type I myosins are involved in positive regulation of actin polymerization, and that this function is required for the uptake step of endocytosis in yeast. We previously showed that the myo5Δ mutant (but not myo3Δ cells) exhibits a partial endocytosis defect at 37°C (Geli and Riezman, 1996) (Figure 4A). Thus, the wt MYO3 seems to be less efficient than MYO5 at sustaining endocytosis at high temperatures. Interestingly, increasing the intracellular actin concentration by providing an extra copy of ACT1 could partially rescue the ts endocytic defect of the myo5Δ strain (Figure 4A). Also, overexpression of Vrp1p efficiently rescued the endocytosis defect of a myo5Δ strain. However, overexpression of Vrp1p or Act1p was not able to restore endocytosis in a myo3Δ myo5-(TH2, SH3)Δ strain, suggesting that suppression required the presence of at least one myosin I SH3 domain (data not shown). Interestingly, overexpression of Las17p failed to restore endocytosis in the myo5Δ strain, suggesting that type I myosins and Las17p share only partially overlapping functions (Evangelista et al., 2000; Lechler et al., 2000). Additionally, deletion of MYO5, but not of MYO3, exhibits synthetic lethality with mutations in genes specifically involved in the regulation of actin polymerization (ARP3, VRP1), but not with other genes required for polarization of the actin cytoskeleton and endocytosis (i.e. SLA2, RVS161, RVS167, SAC6 and END3) (Figure 4B).

Fig. 4. Myo5p might regulate localized actin polymerization. (A) A myo5Δ strain (RH3976) bearing plasmids carrying ACT1 (p413ACT1) and VRP1 (p181VRP1) or the corresponding control plasmids (pRS413 and Ycplac181, respectively) was tested for internalization of α-factor. The percentage of cell-bound α-factor internalized/min is shown. A wt (RH3975) was assayed as control. (B) arp3-62 (SCMIG286) and vrp1Δ (RH2892) strains were crossed to myo5Δ strains (SCMIG276 and RH3976, respectively) bearing a centromeric plasmid with the MYO5 and URA3 genes (p33MYO5), to construct the corresponding single or double mutations carrying p33MYO5, which were streaked on 5′-FOA plates. A representative of each genotype is shown. Lack of synthetic lethality (SL) (see table, –) between myo3Δ or myo5Δ mutations and the indicated mutants (vrp1Δ, arp3-62, sac6Δ, rvs161Δ, rvs167Δ, end3Δ and sla2Δ) was assessed by standard tetrad analysis. *Even though the myo5Δ sla2Δ spores failed to germinate, the double mutant covered with the p33MYO5 plasmid was able to grow on 5′-FOA plates. (C) The C-terminal fragment of the Myo5p tail is able to induce actin polymerization in vitro. Glutathione–Sepharose beads coated with either GST or GST fused to the MYO5 TH2 and SH3 domains [GST–(TH2, SH3)], or the same fusion protein bearing the W1123S mutation, were incubated with extracts from either a wt (RH3975), vrp1Δ (SCMIG48) or arp2-2 (SCMIG4165) strain, or buffer (none), in the presence of rhodamine–actin. Samples were incubated at 30°C and the fluorescent signal visualized using a fluorescence microscope. Latrunculin A (LatA) or Dnase I was added to the (wt + LatA) or (wt + Dnase I) samples, respectively, during the incubation. For the (wt + Pha + LatA) sample, actin filaments polymerized in the absence of beads were stabilized with phalloidin (Pha) prior to the addition of GST–(TH2, SH3)-coated beads and latrunculin A. Representative (+) and (–) signals are recorded in the left panel [GST–(TH2,SH3) and GST, respectively]. The appearance of the beads in a given sample was homogeneous and the assays were repeated at least three times independently.

It has recently been pointed out that the C-terminal region of Myo5p shares homology with Las17p, including an acidic peptide required for the interaction and activation of the Arp2p–Arp3p complex (Winter et al., 1999). Given this information and all previous data regarding the role of Vrp1p and the yeast type I myosins in the regulation of actin polymerization, we postulated that Myo3p and Myo5p might be able to induce localized actin polymerization, and that this activity might then require interaction with Vrp1p. To test this hypothesis directly, we established a visual actin-polymerization assay in vitro based on Ma et al. (1998a,b). In this assay, glutathione–Sepharose beads coated with GST fusion proteins are incubated with cell extracts in the presence of trace amounts of rhodamine-labeled actin. The de novo polymerization of actin triggered by a given GST fusion protein can be monitored under the microscope by visualizing the accumulation of fluorescent signal around the beads. We chose this assay because, in contrast to the pyrene actin-polymerization assay (Cooper et al., 1983), it permits monitoring of actin polymerization and its localization. Strikingly, we found that beads coated with the GST–(SH3, TH2) fusion protein, but not those coated with naked GST, accumulate a bright fluorescent signal when incubated in cell extracts from a wt strain in the presence of rhodamine-labeled actin (Figure 4C). The signal was abolished when the assay was performed in the presence of the latrunculin A or Dnase I (Figure 4C, table), indicating that actin polymerization was required. To dismiss further the possibility that the GST–(TH2, SH3)-coated beads were just binding actin filaments but not inducing its polymerization, cell extracts were incubated with rhodamine–actin in the absence of beads. F-actin was then stabilized with phalloidin and beads finally added in the presence of latrunculin A to prevent further polymerization. No signal was detected on the GST–(TH2, SH3)-coated beads under these conditions. These results clearly point to a direct role of the yeast type I myosins in the regulation of actin polymerization. Myosin-induced actin polymerization was clearly dependent on the presence of other cellular components since no signal was detected on the GST–(SH3, TH2)-coated beads when buffer was used in the assay instead of a cellular extract. Consistent with a proposed function of the yeast type I myosins in the activation of the Arp2–Arp3p actin-nucleation activity, myosin-induced actin polymerization seemed dependent on the presence of this complex because extracts from an arp2-2 mutant were unable to sustain actin polymerization on the beads. To investigate a possible requirement for the Vrp1p–Myo5p interaction in this process, we assayed the GST fusion protein bearing the point mutation that abolished interaction of the Myo5p SH3 domain with Vrp1p (W1123S). Interestingly, this construct was unable to trigger accumulation of fluorescently labeled actin onto the coated beads, indicating that an intact SH3 domain is required for Myo5p-induced localized actin polymerization. This result also suggested the involvement of Vrp1p in the process. In accord, we found that extracts from a vrp1Δ strain were unable to sustain accumulation of rhodamine-labeled actin onto GST–(TH2, SH3)-coated beads (Figure 4C).

Discussion

An intact Myo5p SH3 domain is required to sustain a physiologically relevant interaction between the Myo5p tail and F-actin

As previously demonstrated for the protozoal type I myosins that contain a TH2 domain (Brzeska et al., 1988; Doberstein and Pollard, 1992; Jung and Hammer, 1994; Rosenfeld and Rener, 1994), we found that the Myo5p tail interacts with F-actin. Despite the extensive biochemical characterization of the second actin- binding site of the protozoal type I myosins, no experiments have addressed its role in vivo. We provide here the first genetic evidence suggesting that the Myo5p tail–actin interaction is physiologically relevant. We found that a number of mutations in either MYO5 or ACT1 that greatly diminished this interaction, either in the two-hybrid and/or the actin pelleting assays, also affected their function.

Previous experiments with the protozoal type I myosins indicate that the second ATP-independent actin-binding site resides within the TH2 domain (Brzeska et al., 1988; Doberstein and Pollard, 1992; Jung and Hammer, 1994; Rosenfeld and Rener, 1994). However, our data indicate that the Myo5p tail–actin interaction detected in either the actin-pelleting or the two-hybrid assays resides within the SH3 and the most C-terminal portion of the TH2 domain. The C-terminal fragment containing the SH3 and the TH2c was sufficient to reconstitute the Myo5p tail footprint on the actin molecule, and was necessary and sufficient to mediate the Myo5p tail–actin interaction, both in the two-hybrid and pelleting assays. In contrast, deletion of the N-terminal portion of the TH2 domain did not affect the interaction with actin in either assay. Consistent with this, deletion of the TH2n region in MYO5 did not disrupt its function in endocytosis or in the polarization of the actin cytoskeleton (Anderson et al., 1998).

The apparent discrepancy between previous findings for the protozoal myosins and our findings for the yeast type I myosin could be explained in several ways. It could be that the different results reflect differences in the assays used to monitor the interaction. Otherwise, there could be evolutionary divergence in the structural organization of the myosin tails. It is possible that the region defined as a TH2 domain in Myo5p is not a bona fide TH2 domain. Glycines in this region are rare when compared with the protozoal counterparts, and the percentage of alanine and proline in the C-terminal region downstream of the SH3 domain is relatively low.

The requirement for the SH3 domain for a physiologically relevant Myo5p tail–actin interaction implicates intermediate proteins in this event. We found that a protein that binds both the Myo5p SH3 domain (Anderson et al., 1998) and F-actin (this manuscript and Vaduva et al., 1997), Vrp1p, is required to sustain this interaction both in the two-hybrid and in the actin pelleting assays. The functional importance of this interaction is shown by the fact that point mutations in either actin or in the SH3 domain of Myo5p that strongly diminished the interaction with Vrp1p, also disrupted the ATP-independent actomyosin interaction and endocytic function.

The yeast type I myosins might trigger localized actin polymerization at the sites of endocytosis

It was demonstrated recently that in mast cells transfected with a fusion protein consisting of green fluorescent protein (GFP) and β-actin, endocytic vesicles ignite a burst of actin polymerization at the moment they pinch off from the plasma membrane (Merrifield, 1999). This result suggests a direct involvement of ARP2–ARP3-dependent localized actin polymerization in some endocytic pathways in mammalian cells. In yeast, mutations in different subunits of the ARP2–ARP3 complex inhibit the uptake step of endocytosis (Moreau et al., 1997; Schaerer-Brodbeck and Riezman, 2000), suggesting that a similar mechanism might be involved. The actin-nucleating activity of purified ARP2–ARP3 complex is moderate. It is believed that different molecules, including the members of the WASP family, locally activate the ARP2–ARP3 complex to fulfill distinct cellular functions (Machesky et al., 1999; Madania et al., 1999; Rohatgi et al., 1999; Welch, 1999; Winter et al., 1999; Yarar et al., 1999). Our results suggest that the yeast type I myosins may play a key role in regulating ARP2–ARP3-dependent actin polymerization at the sites of endocytosis. Surprisingly, we observe that increasing the cellular concentration of actin by providing an extra copy of ACT1 partially rescued the ts endocytic defect of the myo5Δ mutant. Furthermore, we could directly demonstrate that the C-terminal domain of Myo5p is able to trigger localized actin polymerization in vitro, and such activity is most likely to depend on the presence of the Arp2p–Arp3p complex. Type I myosins bind acidic phospholipids with high affinity via their TH1 domain (Pollard et al., 1991; Mooseker and Cheney, 1995). Phosphatidic acid and phosphoinositides have been implicated in budding at the plasma membrane (Jost, 1998; Schmidt, 1999). Thus, the type I myosins are candidate proteins to be recruited to sites where these lipids are locally produced, in order to trigger localized Arp2p–Arp3p-dependent actin polymerization.

An intact SH3 domain and Vrp1p might be required to localize myosin-induced actin polymerization

The C-termini of Myo3p and Myo5p share homology with the C-terminal acidic peptide of Las17p, which enhances the actin-nucleating activity of purified Arp2p–Arp3p complex in vitro (Winter et al., 1999; Evangelista et al., 2000; Lechler et al., 2000). In our assay, however, the C-terminus of Myo5p (TH2c) containing the acidic peptide does not suffice to trigger accumulation of rhodamine-labeled actin (data not shown). Rather, our data clearly indicate that the SH3 domain of Myo5p is also required in this process. A point mutation in the SH3 domain completely abolishes accumulation of fluorescence onto the GST–(SH3, TH2)-coated beads. Interest ingly, the same mutations also abolished a physiologically relevant interaction of the Myo5p tail with F-actin. A view consistent with all these data is that the SH3 domain of Myo5p is required to bind the actin filaments that are being nucleated by the Arp2p–Arp3p complex. Thus, the SH3 domain may be required to localize actin polymerization rather than to activate nucleation. Since our results indicate that Vrp1p is required to mediate the Myo5p tail interaction with F-actin, this hypothesis would be consistent with the observation that a cell extract from a vrp1Δ strain is unable to sustain accumulation of rhodamine-labeled actin onto GST–(TH2, SH3)-coated beads. This possibility does not exclude the option that Vrp1p and the C-terminal acidic peptide of Myo5p work synergistically to promote actin polymerization. Localized accumulation of F-actin might, for example, exponentially provide new sites for activation of the Arp2p–Arp3p complex (Blanchoin et al., 2000). Additionally, Vrp1p bears a WH2 (WASP homology 2) domain, which it shares with members of the WASP family including Las17p (Machesky and Insall, 1998; Miki and Takenawa, 1998). This domain binds monomeric actin in vitro, and has been proposed to promote actin polymerization by increasing the concentration of G-actin in the proximity of growing barbed ends of the filamentous actin.

Materials and methods

Yeast, media, strains and genetic techniques

Yeast strains used in this report are listed in Table I with their relevant genotypes. Unless mentioned otherwise, strains that did not bear plasmids were grown in complete media YPUATD [2% glucose, 2% peptone, 1% yeast extract, 40 µg/ml uracil (Ura), 40 µg/ml adenine (Ade) and 40 µg/ml tryptophan (Trp), 2% agar for solid media]. Strains bearing plasmids were selected on SD minimal media (Dulic et al., 1991). Sporulation, tetrad dissection and scoring of genetic markers were performed as described (Sherman et al., 1974). Recombinant lyticase was purified from Escherichia coli as described (Hicke et al., 1997). Transformation of yeast cells was accomplished by the lithium acetate method (Ito et al., 1983).

Table I. Yeast strains.

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| RH3375 | Mata/Matα ade2/ADE2 his3/his3 myo3Δ::HIS3/MYO3 myo5Δ::TRP1/MYO5 leu2/leu2 lys2/LYS2 trp1/trp1 ura3/ura3 bar1/bar1 | Geli and Riezman (1996) |

| SCMIG281 | Mata/Matα ade2/ADE2 his3/his3 myo3Δ::HIS3/MYO3 mycMYO5::URA3::myo5Δ::TRP1/MYO5 leu2/leu2 trp1/trp1 ura3/ura3 bar1/bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG282 | Mata/Matα ade2/ADE2 his3/his3 myo3Δ::HIS3/MYO3 mycmyo5-TH2nΔ::URA3::myo5Δ::TRP1/MYO5 leu2/leu2 trp1/trp1 ura3/ura3 bar1/bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG283 | Mata/Matα ade2/ADE2 his3/his3 myo3Δ::HIS3/MYO3 mycmyo5-(SH3, TH2)Δ::URA3::myo5Δ::TRP1/MYO5 leu2/leu2 trp1/trp1 ura3/ura3 bar1/bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG284 | Mata/Matα ade2/ADE2 his3/his3 myo3Δ::HIS3/MYO3 bar1/bar1 mycmyo5-(TH2, SH3)Δ::URA3::myo5Δ::TRP1/MYO5 leu2/leu2 trp1/trp1 ura3/ura3 | this study |

| RH3975 | Mata ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | Geli et al. (1998) |

| RH2881 | Mata his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | Riezman laboratory |

| RH2884 | Matα ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | Geli et al. (1998) |

| RH3977 | Matα his3 myo3Δ::HIS3 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | Geli et al. (1998) |

| RH3377 | Mata ade2 his3 myo3Δ::HIS3 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | Geli and Riezman (1996) |

| RH3976 | Mata ade2 his3 myo5Δ::TRP1 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | Geli et al. (1998) |

| RH3978 | Mata his3 myo5Δ::TRP1 leu2 lys2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | Geli et al. (1998) |

| SCMIG276 | Matα ade2 his3 myo5Δ::TRP1 leu2 lys2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG277 | Mata ade2 his3 myo3Δ::HIS3 mycMYO5::URA3::myo5Δ::TRP1 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG278 | Mata his3 myo3Δ::HIS3 mycmyo5-TH2nΔ::URA3::myo5Δ::TRP1 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG279 | Mata his3 myo3Δ::HIS3 mycmyo5-(SH3, TH2c)Δ::URA3::myo5Δ::TRP1 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG280 | Mata ade2 his3 myo3Δ::HIS3 mycmyo5-(TH2, SH3)Δ::URA3::myo5Δ::TRP1 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| RH1995 | Mata his4 leu2 bar1 end3Δ::URA3 | Bénédetti et al. (1994) |

| SCMIG37 | Matα ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 end3Δ::URA3 | this study |

| RH2892 | Mata vrp1Δ::URA3 his4 leu2 lys2 ura3 bar1 | Munn et al. (1995) |

| SCMIG40 | Matα ade2 vrp1Δ::URA3 his3 leu2 lys2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| RH4166 | Mata ade2 arp3-62::LEU2 his3 lys2 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1::URA3 | B.Windsor |

| SCMIG286 | Mata ade2 arp3-62::LEU2 his3 lys2 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1::ura3 | this study |

| SCMIG273 | Mata las17Δ::LEU2 his3 ura3 leu2 trp1 bar1 | A.Munn |

| RH3392 | Matα his3 leu2 lys2 trp1 ura3 bar1 end4D::HIS3 pEND4::URA3 | Wesp et al. (1997) |

| SCMIG47 | Matα his3 leu2 lys2 trp1 ura3 bar1 end4D::his3::LEU2 | this study |

| RH2600 | Mata rvs161Δ his4 ura3 bar1 | Munn et al. (1995) |

| RH2950 | Mata leu2 his4 ura3 trp1::URA3 rvs167Δ::TRP1 bar1 | Munn et al. (1995) |

| RH2565 | Mata sac6-Δ::URA3 ura3 bar1 his3 leu2 | Kubler and Riezman (1993) |

| RH4165 | Mata arp2-2::URA3 ts GAL+ ade2 trp1 leu2 his lys2 ura3 bar1 | B.Windsor |

| EGY48 | Mata his3 trp1 ura3 leu2::lexAop6-LEU2 | Gyuris et al. (1993) |

| SCMIG45 | Matα ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 end3Δ::ura3 | this study |

| SCMIG48 | Matα ade2 vrp1Δ::ura3 his3 leu2 lys2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG308 | Mata act1-101::HIS3 ade2 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG309 | Mata act1-102::HIS3 ade2 leu2 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG310 | Mata act1-104::HIS3 ade2 leu2 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG311 | Mata act1-105::HIS3 leu2 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG312 | Mata act1-108::HIS3 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG313 | Mata act1-111::HIS3 ade2 leu2 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG314 | Mata act1-113::HIS3 ade2 leu2 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG315 | Mata act1-115::HIS3 ade2 leu2 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG316 | Mata act1-116::HIS3 ade2 leu2 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG317 | Mata act1-117::HIS3 ade2 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG318 | Mata act1-119::HIS3 ade2 leu2 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG319 | Mata act1-120::HIS3 leu2 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG320 | Mata act1-121::HIS3 ade2 leu2 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG321 | Mata act1-122::HIS3 ade2 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG322 | Mata act1-124::HIS3 ade2 leu2 trp1 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG323 | Mata act1-125::HIS3 ade2 leu2 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG324 | Mata act1-129::HIS3 ade2 leu2 ura3 bar1 | this study |

| SCMIG325 | Mata act1-132::HIS3 ade2 leu2 ura3 bar1 | this study |

Strains SCMIG277 to SCMIG280 were generated by integrating the corresponding wt and mutant MYO5 genes as described in Geli et al. (1998). SCMIG37 and SCMIG40 were obtained by tetrad dissection of crosses of RH1995 and RH2892, respectively, to RH2884.

SCMIG45, SCMIG48 and SCMIG286 were obtained by selection of ura3 mutants, by plating SCMIG37, SCMIG40 and RH4166, respectively, on SD plates containing 2 g/l 5′-fluoroorotic acid (5′-FOA). SCMIG47 was generated from RH3392 (Wesp et al., 1997) by deleting the HIS3 gene using the LEU2 marker and plating the cells on 5′-FOA plates. Lack of synthetic lethality between myo3Δ and myo5Δ mutations, and vrp1Δ, end3Δ, arp3-62, rvs161Δ, rvs167Δ, sac6Δ and sla2Δ was assessed by tetrad analysis. RH2892 (vrp1Δ), RH1995 (end3Δ), RH2600 (rvs161Δ), RH2950 (rvs167Δ) and RH2565 (sac6Δ) were first crossed to RH2884 to generate the corresponding mutant Matα trp1 his3 strains. The resulting strains and SCMIG47 were then crossed to RH3377 (myo3Δ) and RH3976 (myo5Δ). RH4166 (arp3-62) was crossed to RH3977 (myo3Δ) and to SCMIG276 (myo5Δ).

SCMIG308 to SCMIG325 were constructed as follows: heterozygous diploids carrying the different actin alleles linked to HIS3 (DBY5533, 5534, 5536, 5537, 5538, 5543, 5545, 5546, 5547, 5548, 5550, 5551, 5552, 5553, 5555, 5556, 5559 and 5562, respectively) (Wertman et al., 1992) were sporulated, dissected and the segregants scored for the different markers. Matα act1-x haploids were then crossed to RH422-8A (Mata ACT1 ade2 his3 leu2 ura3 trp1 vma2Δ::LEU2 pVMA2::URA3 bar1). The diploids were selected on SD-Ura-Leu, sporulated, dissected and the segregants scored for the appropriated markers. Mata act1-x his3 leu2 ura3 bar1 and either ade2 or ADE2, and trp1 or TRP1, were chosen to perform the assays (SCMIG308 to SCMIG325).

DNA techniques and plasmid constructions

All DNA manipulations were performed according to standard techniques (Sambrook et al., 1989) unless otherwise specified. Restriction enzymes, Klenow and T4 DNA ligase were obtained from Boehringer Mannheim, New England Biolabs, United States Biochemical or Stratagene Cloning Systems. Plasmids were purified by the Qiagen plasmid purification kit (Qiagen), and transformation of E.coli was performed by electroporation (Dower et al., 1988). All PCRs for cloning purposes were performed with a DNA polymerase with proof-reading activity (Pfu, Stratagene Cloning Systems) and a TRIO-thermoblock (Biometra GmbH). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Microsynth GmbH or Interactiva. All constructs were sequenced by Sequencing service of the ZMBH (Im Neuenheimer Feld 282, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany). Plasmids used in this report and their relevant features are listed in Table II. Further details are available upon request.

Table II. Plasmids.

| Plasmid | Yeast Ori | Yeast marker | Insert | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeplac181 | 2 µm | LEU2 | – | Gietz and Sugino (1988) |

| p181VRP1 | 2 µm | LEU2 | VRP1 | this study |

| p181VRP13HA | 2 µm | LEU2 | VRP13HA | |

| pRS413 | CEN | HIS3 | – | Sikorski et al. (1989) |

| p413ACT1 | CEN | HIS3 | ACT1 | this study |

| p33MYO5 | CEN | URA3 | MYO5 | Geli et al. (1998) |

| p111VRP1 | CEN | LEU2 | VRP1 | this study |

| p111vrp1(9–200)Δ | CEN | LEU2 | vrp1(9–200)Δ | this study |

| p111vrp1(201–816)Δ | CEN | LEU2 | vrp1(201–816)Δ | this study |

| pINmycMYO5 | – | URA3 | myc-tagged MYO5 | this study |

| pINmycmyo5-(TH2n)Δ | – | URA3 | myc-tagged myo5-(TH2)Δ | this study |

| pINmycmyo5-(SH3,TH2c)Δ | – | URA3 | myc-tagged myo5-(SH3,DE)Δ | this study |

| pINmycmyo5-(TH2, SH3)Δ | – | URA3 | myc-tagged myo5-(TH2, SH3)Δ | this study |

| pJG4-5 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42 | Gyuris et al. (1993) |

| pJG4-5ACT1 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42ACT1 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-101 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-101 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-102 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-102 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-104 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-104 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-105 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-105 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-108 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-108 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-111 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-111 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-113 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-113 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-115 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-115 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-116 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-116 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-119 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-119 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-120 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-120 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-121 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-121 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-122 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-122 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-124 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-124 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-125 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-125 | this study |

| pJG4-5act1-129 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B42act1-129 | this study |

| pJG4-5RVS167 | 2 µm | TRP1 | B24RVS167 | this study |

| pEG202 | 2 µm | HIS3 | LexA | Gyuris et al. (1993) |

| pEG202MYO5 | 2 µm | HIS3 | LexAMYO5 tail (aa 757–1219) | this study |

| pEG202 myo5-(TH2c)Δ | 2 µm | HIS3 | LexAmyo5-(TH2c)Δ tail (aa 757–1181) | this study |

| pEG202 myo5-(SH3,TH2c)Δ | 2 µm | HIS3 | LexAmyo5-(SH3,TH2c)Δ tail (aa 757–1091) | this study |

| pEG202 myo5-(TH2, SH3)Δ | 2 µm | HIS3 | LexA myo5-(TH2, SH3)Δ tail (aa 757–996) | this study |

| pEG202(TH2, SH3) | 2 µm | HIS3 | LexA(TH2, SH3) domain (aa 984–1219) | this study |

| pEG202(SH3, TH2c) | 2 µm | HIS3 | LexA(SH3, TH2c) domain (aa 1085–1219) | this study |

| pEG202(TH2n, SH3) | 2 µm | HIS3 | LexA(TH2n, SH3) domain (aa 984–1181) | this study |

| pEG202TH2c | 2 µm | HIS3 | LexATH2c domain (aa 1142–1219) | this study |

| pEG202TH2 | 2 µm | HIS3 | LexATH2 domain (aa 984–1091) | this study |

| pEG202SH3 | 2 µm | HIS3 | LexASH3 domain (aa 1085–1181) | this study |

| pEG202 myo5-TH2nΔ | 2 µm | HIS3 | LexAmyo5-TH2nΔ tail (aa 757–996) + (aa1095–1219) | this study |

| pEG202END3 | 2 µm | HIS3 | LexAEND3 | this study |

| pSH18–34 | 2 µm | URA3 | 8 LexA Op. lacZ | Gyuris et al. (1993) |

| pRFM-1 | 2 µm | HIS3 | LexAbicoid | Gyuris et al. (1993) |

| pGEX5X-3 | – | – | GST | |

| pGST-(TH2,SH3) | – | – | GST-(TH2, SH3) domain (aa 984–1219) | |

| pGST-(TH2,SH3)-W1123S | – | – | GST-(TH2, SH3) domain (aa 984–1219)–W1123S | |

| pGST-(SH3,TH2c) | – | – | GST-(SH3, TH2c) domain (aa 1085–1219) | |

| pGST-(TH2c) | – | – | GST-TH2c domain (aa 1142–1219) |

Immunoblots and antibodies

SDS–PAGE for protein separation was performed as described (Laemmli, 1970) using a Minigel system (Bio-Rad). High and low range SDS–PAGE molecular weight standards (Bio-Rad) were used for determination of apparent molecular weight. Protein concentration was determined using a Bio-Rad Protein assay (Bio-Rad). Total yeast protein extractions, western blotting and immunodetection were performed as described (Geli et al., 1998) using the polyclonal EW and IK antibodies against Myo5p C-terminal peptides (Geli et al., 1998), the 9E10 anti-myc monoclonal antibody (Roche Biochemicals) and the C4 anti-actin monoclonal antibody (Roche Biochemicals).

Yeast extracts

Yeast cells were grown in rich media to a density of ∼4 × 107 cells/ml. Cells were harvested and washed twice with XB [100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM ATP, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.7] 50 mM sucrose. One-tenth pellet volume of XB 50 mM sucrose was added and the cells glass bead-lysed in the presence of proteinase inhibitors [0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 µg/ml aprotinin, 1 µg/ml pepstatin, 1 µg/ml leupeptin]. Unbroken cells and debris were eliminated by centrifugation at 2500 g at 4°C. Low speed pelleted (LSP) extracts were supplemented with sucrose (to 200 mM), frozen in liquid N2 and stored at –80°C until use in the actin-polymerization assay. Protein concentration (30–40 mg/ml) was measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay. Aliquots (100 µl) of the LSP extracts were transferred to 1.5 ml polyallomer tubes (Beckman Instruments) and spun twice for 2 h at 45 000 r.p.m. in a TL100 Beckman table-top ultracentrifuge using a TLA-45 rotor. Supernatants (cytosol, HSP) were collected, supplemented to 200 mM sucrose, frozen in liquid N2 and stored at –80°C until use in the pelleting assays. Approximately 10–20 mg of protein per ml of HSP extract was measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay.

Recombinant GST fusion protein purification

pGST plasmids were transformed into BL21 E.coli (Novagen). Cultures grown at 24°C in minimal media (MM) (Sambrook et al., 1989) and 50 mg/l ampicillin were induced at OD 0.7–0.8 with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 2 h. A GST Amersham-Pharmacia purification kit was used (27-4570-01) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified GST fusion proteins were supplemented with 10% glycerol, frozen in liquid N2 and stored at –80°C until use in the actin pelleting assay. GST fusion proteins were freshly purified to a final concentration of 2 mg of fusion protein per ml of 50% glutathione–Sepharose for the actin-polymerization assay.

Actin pelleting assays

The actin pelleting assays performed with the yeast strains expressing the myc-tagged wt and mutant Myo5p, and HA-tagged VRP1 were based on Wang et al. (1998). Cells were grown to a density of 2 × 107 cells/ml. For each pelleting assay, 3 × 109 cells were harvested. Half a pellet volume of 3× EB was added (EB: 20 mM PIPES pH 6.8, 100 mM sorbitol, 100 mM KOAc, 25 mM KCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 1 µg/ml aprotinin, 1 µg/ml pepstatin, 1 µg/ml leupeptin) on ice, and the cells glass bead-lysed. Unbroken cells and debris were eliminated by centrifugation at 2500 g at 4°C. The protein concentration of the supernatant was adjusted to 15 µg/µl with EB. Three 100 µl aliquots of the protein extract were transferred to 1.5 ml polyallomer tubes (Beckman Instruments) and spun for 2 h at 45 000 r.p.m. in a TL100 Beckman table-top ultracentrifuge using a TLA-45 rotor. The supernatants were collected into a fresh tube and 2× 70 µl were transferred to polyallomer tubes containing 10 µl of 3× EB and 20 µl of G buffer (5 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM ATP) containing 2 mg/ml actin (Sigma A-2522). Seventy microliters were transferred to a polyallomer tube containing 10 µl of 3× EB and 20 µl of G buffer for the minus actin control. After 2 h incubation at 4°C, 2 µl of apyrase (0.1 U/µl) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) were added to one of the samples containing actin for the minus ATP control. Ten minutes after incubation at room temperature, the samples were centrifuged at 45 000 r.p.m. for 2 h at 4°C. The supernatants were discarded and the pellet washed once with 100 µl of EB either treated with apyrase (for the minus ATP control) or not. After centrifuging at 45 000 r.p.m. for 2 h at 4°C, the pellets were resuspended in 30 µl of SDS–PAGE sample buffer and processed for immunoblot analysis. After the first ultracentrifugation, 14 µl of protein extract were loaded as total.

For experiments performed with the recombinant Myo5p fragments, 20 µl of the HSP fraction (adjusted to 10 mg/ml) of the corresponding strain (see above) were diluted with 60 µl of XB to bring the sucrose concentration to 50 mM, and centrifuged for 2 h at 4°C at 45 000 r.p.m. in the TLA-45 rotor. Seventy microliters of the supernatant were recovered and mixed with 4 µl of G buffer or 4 µl of G-actin, either 2 or 4 µg/µl. After mixing, 3 µl of the corresponding GST fusion proteins, adjusted to 0.5 µM, were added and the samples incubated at 4°C for 2 h. After centrifuging for 2 h at 4°C at 45 000 r.p.m., the supernatant was aspirated and the pellet washed with 100 µl of XB 50 mM sucrose. After further centrifugation for 2 h, the supernatant was eliminated and the pellet resuspended in 20 µl of SDS–PAGE SB. Three microliters of the corresponding GST fusion proteins adjusted to 0.5 µM were brought to 20 µl with SDS–PAGE sample buffer, and the same amount loaded on the gel as total for comparison.

Visual actin-polymerization assay

The actin-polymerization assay was designed according to Ma et al. (1998a,b). Briefly, 7 µl of LSP extracts adjusted to 20 mg of protein/ml with XB 200 mM sucrose or buffer were mixed with 1 µl of ARS (10 mg/ml creatine kinase, 10 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2, 400 mM creatine phosphate) and 1 µl of 10 µM rhodamine-labeled actin (Cytoskeleton, Inc.). The polymerization reaction was initiated by adding 1 µl of 50% glutathione–Sepharose beads bound to 2–3 µg of the corresponding GST fusion protein. Samples were incubated at 30°C and visualized using fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss Axioskop) after 10–20 min incubation. Latrunculin A and Dnase I were added to a final concentration of 10 µM and 0.5 µg/µl, respectively, prior to the addition of the glutathione–Sepharose beads. Phalloidin was added at 1 µg/ml.

α-factor uptake assay

[35S]α-factor uptake assays were performed as described by Dulic et al. (1991). A pulse–chase protocol was used. Cells were grown in YPUATD or minimal media at 24°C to a density of 0.5–1 × 10 cells/ml, harvested and resuspended in ice-cold YPUATD media for binding of α-factor at 0°C for 45 min. Cells were harvested at 4°C to eliminate unbound α-factor, and internalization was triggered by resuspension in 37°C pre-warmed YPUATD. Samples were taken at the indicated time points into pH 1 and pH 6 buffers. Internalized counts were calculated by dividing pH 1 by pH 6 resistant counts at each time point. The internalization rates were calculated as the percentage of counts internalized per minute between 5 and 10 min (linear range). All uptake assays were performed at least twice, and the mean and standard deviations calculated for each time point.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Riezman and Geli laboratories for discussion. We are grateful to D.Botstein, B.Winsor, A.Munn and R.Brent for sending strains and plasmids. M.I.G. thanks members of the BZH for general support. This work was funded by the Canton Basel-Stadt, a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (H.R.), by the University of Heidelberg and a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (M.I.G.; SFB 352).

References

- Albanesi J.P., Fujisaki,H. and Korn,E.D. (1985) A kinetic model for the molecular basis of the contractile activity of Acanthamoeba myosins IA and IB. J. Biol. Chem., 260, 11174–11179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberg D.C., Basart,E. and Botstein,D. (1995) Defining protein interactions with yeast actin in vivo. Nature Struct. Biol., 2, 28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B.L., Boldogh,I., Evangelista,M., Boone,C., Greene,L.A. and Pon,L.A. (1998) The Src homology domain 3 (SH3) of a yeast type I myosin, Myo5p, binds to verprolin and is required for targeting to sites of actin polarization. J. Cell Biol., 141, 1357–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchoin L., Amann,K.J., Higgs,H.N., Marchand,J.B., Kaiser,D.A. and Pollard,T.D. (2000) Direct observation of dendritic actin filament networks nucleated by Arp2/3 complex and WASP/Scar proteins. Nature, 404, 1007–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzeska H., Lynch,T.J. and Korn,E.D. (1988) Localization of the actin-binding sites of Acanthamoeba myosin IB and effect of limited proteolysis on its actin-activated Mg2+-ATPase activity. J. Biol. Chem., 263, 427–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J.A., Walker,S.B. and Pollard,T.D. (1983) Pyrene actin: documentation of the validity of a sensitive assay for actin polymerization. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil., 4, 253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doberstein S.K. and Pollard,T.D. (1992) Localization and specificity of the phospholipid and actin binding sites on the tail of Acanthamoeba myosin IC. J. Cell Biol., 117, 1241–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dower W.J., Miller,J.F. and Ragsdale,C.W. (1988) High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res., 16, 6127–6145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulic V., Egerton,M., Elguindi,I., Raths,S., Singer,B. and Riezman,H. (1991) Yeast endocytosis assays. Methods Enzymol., 194, 697–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista M., Klebl,B.M., Tong,A.H., Webb,B.A., Leeuw,T., Leberer,E., Whiteway,M., Thomas,D.Y. and Boone,C. (2000) A role for myosin-I in actin assembly through interactions with Vrp1p, Bee1p and the Arp2/3 complex. J. Cell Biol., 148, 353–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisaki H., Albanesi,J.P. and Korn,E.D. (1985) Experimental evidence for the contractile activities of Acanthamoeba myosins IA and IB. J. Biol. Chem., 260, 11183–11189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geli M.I. and Riezman,H. (1996) Role of type I myosins in receptor-mediated endocytosis in yeast. Science, 272, 533–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geli M.I., Wesp,A. and Riezman,H. (1998) Distinct functions of calmodulin are required for the uptake step of receptor-mediated endocytosis in yeast: the type I myosin Myo5p is one of the calmodulin targets. EMBO J., 17, 635–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson H.V., Anderson,B.L., Warrick,H.M., Pon,L.A. and Spudich,J.A. (1996) Synthetic lethality screen identifies a novel yeast myosin I gene (MYO5): myosin I proteins are required for polarization of the actin cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biol., 133, 1277–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyuris J., Golemis,E., Chertkov,H. and Brent,R. (1993) Cdi1, a human G1 and S phase protein phosphatase that associates with Cdk2. Cell, 75, 791–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke L., Zanolari,B., Pypaert,M., Rohrer,J. and Riezman,H. (1997) Transport through the yeast endocytic pathway occurs through morphologically distinct compartments and requires an active secretory pathway and Sec18p/N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein. Mol. Biol. Cell, 8, 13–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Fukuda,Y., Murata,K. and Kimura,A. (1983) Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol., 153, 163–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost M., Simpson,F., Kavran,J.M., Lemmon,M.A. and Schmid,S.L. (1998) Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate is required for endocytic coated vesicle formation. Curr. Biol., 8, 1399–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung G. and Hammer,J.A.,III (1994) The actin binding site in the tail domain of Dictyostelium myosin IC (myoC) resides within the glycine- and proline-rich sequence (tail homology region 2). FEBS Lett., 342, 197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung G., Wu,X. and Hammer,J.A.,III (1996) Dictyostelium mutants lacking multiple classic myosin I isoforms reveal combinations of shared and distinct functions. J. Cell Biol., 133, 305–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubler E. and Riezman,H. (1993) Actin and fimbrin are required for the internalization step of endocytosis in yeast. EMBO J., 12, 2855–2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyan J. and Cowburn,D. (1997) Modular peptide recognition domains in eukaryotic signaling. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct., 26, 259–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U.K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechler T., Shevchenko,A. and Li,R. (2000) Direct ivolvement of yeast type I myosins in Cdc42-dependent actin polymerization. J. Cell Biol., 148, 363–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch T.J., Albanesi,J.P., Korn,E.D., Robinson,E.A., Bowers,B. and Fujisaki,H. (1986) ATPase activities and actin-binding properties of subfragments of Acanthamoeba myosin IA. J. Biol. Chem., 261, 17156–17162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Cantley,L.C., Janmey,P.A. and Kirschner,M.W. (1998a) Corequirement of specific phosphoinositides and small GTP-binding protein Cdc42 in inducing actin assembly in Xenopus egg extracts. J. Cell Biol., 140, 1125–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Rohatgi,R. and Kirschner,M.W. (1998b) The Arp2/3 complex mediates actin polymerization induced by the small GTP-binding protein Cdc42. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 15362–15367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machesky L.M. and Insall,R.H. (1998) Scar1 and the related Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein, WASP, regulate the actin cytoskeleton through the Arp2/3 complex. Curr. Biol., 8, 1347–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machesky L.M., Mullins,R.D., Higgs,H.N., Kaiser,D.A., Blanchoin,L., May,R.C., Hall,M.E. and Pollard,T.D. (1999) Scar, a WASp-related protein, activates nucleation of actin filaments by the Arp2/3 complex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 3739–3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madania A., Dumoulin,P., Grava,S., Kitamoto,H., Scharer-Brodbeck,C., Soulard,A., Moreau,V. and Winsor,B. (1999) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologue of human Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein Las17p interacts with the Arp2/3 complex. Mol. Biol. Cell, 10, 3521–3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrifield C.J., Moss.S.E., Ballestrem,C., Imhof,B.A., Giese,G., Wunderlich,I. and Almers,W. (1999) Endocytic vesicles move at the tips of actin tails in cultured mast cells. Nature Cell Biol., 1, 72–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki H. and Takenawa,T. (1998) Direct binding of the verprolin-homology domain in N-WASP to actin is essential for cytoskeletal reorganization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 243, 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooseker M.S. and Cheney,R.E. (1995) Unconventional myosins. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol., 11, 633–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau V., Galan,J.M., Devilliers,G., Haguenauer-Tsapis,R. and Winsor,B. (1997) The yeast actin-related protein Arp2p is required for the internalization step of endocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell, 8, 1361–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn A.L., Stevenson,B.J., Geli,M.I. and Riezman,H. (1995) end5, end6 and end7: mutations that cause actin delocalization and block the internalization step of endocytosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell, 6, 1721–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi S.N., Zahn,R., Mitchell,D.A., Stevenson,B.J. and Munn,A.L. (1998) The WASp homologue Las17p functions with the WIP homologue End5p/verprolin and is essential for endocytosis in yeast. Curr. Biol., 8, 959–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak K.D., Peterson,M.D., Reedy,M.C. and Titus,M.A. (1995) Dictyostelium myosin I double mutants exhibit conditional defects in pinocytosis. J. Cell Biol., 131, 1205–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard T.D., Doberstein,S.K. and Zot,H.G. (1991) Myosin-I. Annu. Rev. Physiol., 53, 653–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatgi R., Ma,L., Miki,H., Lopez,M., Kirchhausen,T., Takenawa,T. and Kirschner,M.W. (1999) The interaction between N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex links Cdc42-dependent signals to actin assembly. Cell, 97, 221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld S.S. and Rener,B. (1994) The GPQ-rich segment of Dictyostelium myosin IB contains an actin binding site. Biochemistry, 33, 2322–2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Schaerer-Brodbeck C. and Riezman,H. (2000) Functional interactions between the p35 subunit of the Arp2/3 complex and calmodulin in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell, 11, 1113–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A., Wolde,M., Thiele,C., Fest,W., Kratzin,H., Podtelejnikov,A.V., Witke,W., Huttner,W.B. and Soling,H.D. (1999) Endophilin I mediates synaptic vesicle formation by transfer of arachidonate to lysophosphatidic acid. Nature, 401, 133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman S., Fink,G. and Lawrence,C. (1974) Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Vaduva G., Martin,N.C. and Hopper,A.K. (1997) Actin-binding verprolin is a polarity development protein required for the morphogenesis and function of the yeast actin cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biol., 139, 1821–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaduva G., Martinez-Quiles,N., Anton,I.M., Martin,N.C., Geha,R.S., Hopper,A.K. and Ramesh,N. (1999) The human WASP-interacting protein, WIP, activates the cell polarity pathway in yeast. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 17103–17108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.X., Catlett,N.L. and Weisman,L.S. (1998) Vac8p, a vacuolar protein with armadillo repeats, functions in both vacuole inheritance and protein targeting from the cytoplasm to vacuole. J. Cell Biol., 140, 1063–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch M.D. (1999) The world according to Arp: regulation of actin nucleation by the Arp2/3 complex. Trends Cell Biol., 9, 423–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertman K.F., Drubin,D.G. and Botstein,D. (1992) Systematic mutational analysis of the yeast ACT1 gene. Genetics, 132, 337–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesp A., Hicke,L., Palecek,J., Lombardi,R., Aust,T., Munn,A.L. and Riezman,H. (1997) End4p/Sla2p interacts with actin-associated proteins for endocytosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell, 8, 2291–2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter D., Lechler,T. and Li,R. (1999) Activation of the yeast Arp2/3 complex by Bee1p, a WASP-family protein. Curr. Biol., 9, 501–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarar D., To,W., Abo,A. and Welch,M.D. (1999) The Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein directs actin-based motility by stimulating actin nucleation with the Arp2/3 complex. Curr. Biol., 9, 555–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]