Abstract

The carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) of the core protein of hepatitis B virus is not necessary for capsid assembly. However, the CTD does contribute to encapsidation of pregenomic RNA (pgRNA). The contribution of the CTD to DNA synthesis is less clear. This is the case because some mutations within the CTD increase the proportion of spliced RNA to pgRNA that are encapsidated and reverse transcribed. The CTD contains four clusters of consecutive arginine residues. The contributions of the individual arginine clusters to genome replication are unknown. We analyzed core protein variants in which the individual arginine clusters were substituted with either alanine or lysine residues. We developed assays to analyze these variants at specific steps throughout genome replication. We used a replication template that was not spliced in order to study the replication of only pgRNA. We found that alanine substitutions caused defects at both early and late steps in genome replication. Lysine substitutions also caused defects, but primarily during later steps. These findings demonstrate that the CTD contributes to DNA synthesis pleiotropically and that preserving the charge within the CTD is not sufficient to preserve function.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) replicates its genome via reverse transcription of a pregenomic RNA (pgRNA). This process ultimately produces a double-stranded DNA with a relaxed-circular conformation (rcDNA) (for a review, see reference 57). A distinguishing feature of HBV reverse transcription is that it occurs within the viral capsid. In the absence of HBV capsids, the HBV polymerase (P) is not able to produce rcDNA genomes from pgRNAs (36, 58, 61). Observations like these suggest that the capsid participates in reverse transcription.

HBV capsids are icosahedra with primarily T=4 symmetry (9, 16, 19). Each capsid contains 120 dimers of the core protein (16, 69), and capsids can assemble in the absence of other viral components (59). A region of the core protein that is a candidate for a role in reverse transcription is the carboxy-terminal region of 34 amino acids, known as the carboxy-terminal domain (CTD). Capsids without the CTD assemble normally but do not support genome replication (8, 47, 70). The CTD can be attached to the capsid interior at the 5- or quasi-6-fold axes (71). Also, the CTD can bind to nucleic acids in vitro (28). Nearly 50% of the residues in the CTD are arginines, which give the CTD a net positive charge. Fourteen of the sixteen arginines are grouped into four clusters of three or four (see Fig. 2A for the amino acid sequence). This arrangement is conserved among mammalian hepadnaviruses (Fig. 2A), suggesting it is important for function. Serines at positions 155, 162, and 170 are also conserved and can be phosphorylated in HBV (17, 21, 40). However, it is not fully understood which features of the CTD (arginine clusters, serine phosphoacceptor sites, or other) contribute to genome replication. The goal of the present study is to understand how each arginine cluster contributes to genome replication. In addition, we are interested in knowing whether maintaining the positive charge is sufficient to preserve function. Understanding these aspects of the CTD will help to determine the mechanisms by which it functions.

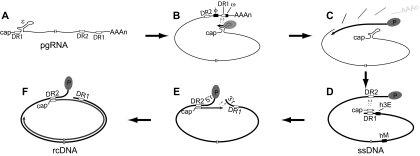

We analyzed the contribution of the CTD to each step in genome replication (Fig. 1). First, HBV packages its pgRNA into capsids (encapsidation). To accomplish this, a stem-loop, epsilon (ɛ), forms near the 5′ end of the pgRNA and associates with the viral P protein to form the encapsidation signal (5, 6, 12, 32, 50). After co-encapsidation of the pgRNA and P protein, minus-strand DNA is initiated by using tyrosine 63 of the P protein as the priming residue (22, 65, 72) and the bulge of ɛ as the template (48, 53, 62, 65). The short, nascent DNA then switches template to a complementary sequence near the 3′ end of the pgRNA where minus-strand DNA synthesis resumes [(−) template switch] (Fig. 1B) (48, 53, 62, 64). The specificity of this template switch is determined by base pairing between nucleotides in ɛ and nucleotides flanking the acceptor site (φ and ω) (2, 3). Subsequently, the minus-strand DNA is elongated to produce a full-length minus-strand DNA [(−)DNA elongation] (Fig. 1C). As minus-strand DNA is synthesized, the RNase H activity of the P protein digests the pgRNA but leaves the 5′ ∼17 nucleotides intact (11, 25, 66). In a majority of cases, this RNA fragment undergoes a template switch from the 3′ end of the minus strand to anneal to a complementary 11-nucleotide sequence near the 5′ end, termed DR2, and primes plus-strand DNA synthesis at DR2 (primer translocation; Fig. 1D) (56, 66). After plus-strand DNA is elongated to the 5′ end of its template, a final template switch occurs in which the nascent plus strand switches from the 5′-terminal redundancy (5′r) to anneal at the 3′-terminal redundancy (3′r) (circularization) (Fig. 1E) (66). Both primer translocation and circularization are promoted by base pairing between cis-acting sequences h3E (near DR1) and hM (near the middle of the genome) (39). Once circularization has completed, plus-strand DNA synthesis resumes, and the plus strand is elongated to produce a rcDNA [(+)DNA elongation; Fig. 1F]. In a minority of capsids, primer translocation does not occur, and plus-strand DNA primes from DR1 (in situ priming) to produce a duplex-linear genome (dlDNA) (60).

FIG. 1.

DNA synthesis for HBV. (A) The pgRNA is greater than the genome length and has 5′ and 3′ copies of the 11-nt direct repeat sequence DR1 and the stem-loop ɛ. The relative position of the other direct repeat sequence, DR2, is also indicated. pgRNA is translated to make the core protein and P protein. Dimers of the core protein assemble into capsids. P protein associates with ɛ and the combination of the two comprises the encapsidation signal. (B) (−)DNA template switch. Minus-strand DNA synthesis initiates within the bulge of ɛ. Tyrosine 63 of P protein is the primer for the first 3 to 4 nt and the bulge of ɛ is the template. The minus-strand then switches template to an acceptor site within the 3′ copy of DR1. Base pairing between nucleotides in the upper stem of ɛ and cis-acting sequences φ and ω contribute to these steps. (C) (−)DNA elongation. Minus-strand DNA elongation and concomitant RNase H degradation of the pgRNA are catalyzed by the P protein, resulting in a full-length, single-stranded DNA. The 5′-most end of the pgRNA remains undigested. (D) Primer translocation. The pgRNA remnant undergoes a template switch from DR1 to DR2 and primes plus-strand DNA synthesis from DR2. The process cannot proceed without cis-acting sequences h3E and hM, which base pair with one another. Several other cis-acting sequences make additional contributions to the process (41). (E) Circularization. After synthesizing to the 5′ end of the minus-strand DNA template, the 3′ end of the plus-strand switches templates to use the 3′ end of minus-strand DNA. Like primer translocation, this step requires base pairing between cis-acting sequences h3E and hM (39). (F) (+) Elongation. Once annealed to 3′r, the plus-strand synthesis resumes, ultimately yielding rcDNA.

Previous studies have made progress toward understanding how the CTD contributes to these steps, but the issue remains unresolved. Multiple studies have demonstrated that truncating the core protein after residue 164 prevented detectable accumulation of rcDNA (8, 34, 37, 47). Mutation of the phosphoacceptor sites in the CTD also produced a similar result (34). A partial explanation for these findings is that CTD truncations (8, 34, 37, 47) and mutations at the serine phosphorylation sites (21, 34, 44) decreased the total amount of HBV nucleic acids within capsids. Also, spliced pgRNAs are preferentially reverse transcribed in many mutants (34, 37; for descriptions of spliced HBV mRNAs, see references 1 and 23). Together, these findings have made a compelling case that a role of the CTD is to promote RNA encapsidation.

The role of the CTD in subsequent DNA synthesis is less clear. Many mutations within the CTD have been shown to reduce rcDNA accumulation (8, 34, 37, 47). However, these reductions could have been because reverse transcription of spliced pgRNA was enhanced in those mutants.

In the present study, we avoided complications due to the presence of spliced RNA by carrying out all analyses in a genetic background in which splicing is reduced. A mutation in the pgRNA reduced most spliced pgRNAs to undetectable levels (1). Primer extension methods and Southern blotting were used to examine different steps in genome replication. Our analysis accounted for defects in preceding steps. Variants in which each arginine cluster was replaced with either alanines or lysines were analyzed. Our results indicate that the CTD contributes to both early and late steps and that maintaining positive charges within the clusters does not necessarily preserve function. These findings suggest that new models are required to explain the how the CTD contributes to genome replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular clones.

All HBV plasmids contained the sequence found at GenBank accession number V01460 (subtype ayw, genotype D). Nucleotide position 1 was designated to be the C of the unique EcoRI site (GAATTC).

The wild-type (WT) core protein was expressed from plasmid EL43, which is a derivative of previously described plasmid LJ96 (41). EL43 contains HBV nucleotides (nt) 1857 to 1986 (nucleotide numbering goes from nt 1857 to 3182 and restarts at nt 1 to 1986) except for a small deletion within ɛ that prevents encapsidation of pgRNA. EL43 contains the substitutions T2342A (which creates a premature stop codon at codon 13 of P protein), T154C (which disrupts the S protein start codon), and C169A (which creates a premature stop codon in all envelope proteins). All plasmids that express core protein mutants were derived from EL43 with the exception of mutant Y132A, which contained a different mutation, T2306C, to prevent expression of P protein. P protein and pgRNA were expressed from plasmid EL100, which is a derivative of previously described plasmid, LJ144 (1), and differs by the addition of a premature stop codon in the C gene by changing nucleotides at position 1908 from GACC to TAAG, and a substitution in the 3′ splice acceptor site by changing nucleotides at position 484 from CAGG to GTCC. A second P protein and pgRNA expression plasmid, LJ145, was also analyzed. LJ145 is similar to EL100 except that it lacks the 4-nt substitution at position 484; this variant was used to demonstrate that altering the 3′ splice acceptor site did not also affect replication (data not shown). Plasmid EL122 was used to express pgRNA and P for experiments in which the catalytic site of P was changed from YMDD to YMHA by nucleic acid substitutions A731T, G732C, T733C, T736C, G740C, T742C, A744C, and T745C. Altering YMDD to YMHA has been shown to ablate DNA synthesis while preserving pgRNA encapsidation (51). Expression of the core protein from plasmid EL122 was also disrupted by a premature stop codon as in variant EL100. The reference RNA for encapsidation analysis (EL130) differed from EL122 by the addition of CTAATC at position 1833, such that the pgRNA could be distinguished from normal pgRNA in a primer extension analysis. Also, EL130 expressed WT core protein. Molecular clones of variants were generated by oligonucleotide, site-directed mutagenesis and were verified by DNA sequencing. Plasmid LJ200 (39) was used as an internal standard for DNA primer extension and Southern blot analyses. LJ200 was digested with HphI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) to generate fragments of the appropriate size for the assays.

Cell culture and transfection.

The human hepatoma cell line HepG2 was used in all analyses. Cell culture and transfection via calcium phosphate precipitation were carried out as previously described (39, 42), except that 9 μg of each plasmid, along with 1 μg of an expression plasmid for green fluorescent protein, for a total of 19 μg of DNA were transfected per dish. Cells were harvested on day 3 for analysis of capsid assembly, pgRNA encapsidation, and minus-strand DNA template switch. Cells were harvested on day 5 for analysis of all other steps in DNA synthesis.

Isolation of core and viral replicative intermediates.

For all analyses, cell cultures were washed with 2 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EGTA (pH 7.45), and then frozen at −70°C. Later, cells were thawed to room temperature and lysed with 0.2% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl, and 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) for 10 min. The nuclei were then removed by centrifugation as described previously (39, 42). For isolation of encapsidated viral nucleic acids, lysates were adjusted to 2 mM CaCl2 and then incubated with 44 U of micrococcal nuclease (MNase; Worthington) to digest transfected plasmid DNA and unencapsidated HBV RNA. After 2 h, these reactions were supplemented with EDTA to 10 mM, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to 0.4% and Pronase (Roche) to 400 μg/ml, followed by incubation for 2 h at 37°C. Nucleic acid was extracted with a phenol-chloroform mixture and precipitated with ethanol. For isolation of DNA, 1 μg of RNase A was added. For isolation of total cellular RNA, the addition of MNase and subsequent 2 h of incubation were omitted. For analysis of capsid assembly, the lysate was used prior to addition of CaCl2 or MNase.

Analysis of capsid assembly by sedimentation velocity centrifugation and Western blotting.

Capsid assembly was assessed by gently layering 200 μl of the NP-40 lysate (out of 450 μl of total lysate) on a 4-layer sucrose gradient (0.975 ml each: 15, 30, 45, and 60%) and centrifugation at 52,000 rpm for 2.5 h in a Beckman SW60 rotor. Equal volumes of each fraction were electrophoresed through a 15% polyacrylamide-SDS gel and analyzed by Western blotting with a rabbit anti-core polyclonal primary antibody (B0586; Dako) and an infrared (IR) dye-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Li-Cor). Western blots were scanned by using a Li-Cor Odyssey IR imager and quantitated by using LiCor software. Core protein expressed and purified from Escherichia coli (a gift from Zach Porterfield and Adam Zlotnick, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN) was used to establish the linearity of signal output using this Western blotting procedure (data not shown).

Southern blot analyses.

Native or heat-denatured viral DNA was analyzed by Southern blotting as described previously (39). Probes 1816+, 1833+, 1857+, and 1876+ were used to detect the 3′ end of full-length minus-strand DNA (Table 1). All oligonucleotides were 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP as previously described (1). For Fig. 8B, (+)DNA was detected by using a plus-strand-specific, radiolabeled riboprobe spanning the entire genome. The riboprobe was in vitro transcribed using T3 polymerase and plasmid LJ158 (41). Detection of the internal standard (I.S.) DNA was achieved by using radiolabeled oligonucleotide probes b1, b2, b3, and b4 (Table 1) that were specific for the non-HBV region of plasmid LJ200.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide DNA sequences

| Oligoa | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| 1816+ | AACTTTTTCACCTCTGC |

| 1833+ | CTAATCATCTCTTGTTCATGTC |

| 1857+ | ACTGTTCAAGCCTCCAAGCT |

| 1876+ | TGTGCCTTGGGTGGCTTTGG |

| 1995+ | ACCGCCTCAGCTCTGTATCG |

| b1 | GAGCCTATGGAAAAACGCCA |

| b2 | GCAACGCGGCCTTTTTAC |

| b3 | AGCGTCGATTTTTGTGATGCT |

| b4 | TTCGCCACCTCTGACTTG |

| 1740− | CAACTCCTCCCAGTCTTTAAACA |

| 1948− | GAGAGTAACTCCACAGTAGCTCC |

| 1661− | GTCCTCTTATGTAAGACCTTGGGC |

| 1556+ | CCTTCTCATCTGCCGGAC |

| 1661+ | CTCTTGGACTCTCAGCAATGTCAAC |

Sequences are named based on the first nucleotide of HBV sequences to which they anneal. The “+” indicates that the oligo has the same polarity as the positive strand; the “−” denotes that the oligo has the same polarity as the negative strand. Oligos b1 to b4 are complementary to the plasmid backbone sequence.

For the Southern blots shown in Fig. 7, HBV and I.S. DNA were not detected simultaneously. Instead, the HBV DNA was detected first, the oligonucleotide probes were removed from the membranes, and the I.S. DNA was detected subsequently. To remove oligonucleotide probes between hybridizations, membranes were incubated in water for 30′ at 70°C, and removal was confirmed via autoradiography. The masses of HBV DNA and I.S. DNA were determined by comparing the signal in each sample to a standard curve of known amounts of linearized DNA plasmid. This strategy allowed HBV DNA to be normalized to I.S. DNA without concern for differences in detection efficiency between the HBV- and I.S.-specific probes.

Primer extension analysis.

All oligonucleotide primers were 5′ end labeled with 32P. The approximate annealing positions of oligonucleotide primers are indicated in the figures. The sequences of oligonucleotides are given in Table 1. For analysis of RNA by primer extension (as shown in Fig. 3D and E), primer extension was conducted as described previously (2), except only a single primer, oligonucleotide 1948−, was used. For analyses of DNA by the combined primer extension and Southern blotting techniques used in Fig. 7, 2 ng of internal standard DNA and 1 μg of RNase A were added to each viral DNA sample. Samples were then incubated for 2 h at 37°C, precipitated with ethanol, and resuspended in H2O prior to dividing each sample. The rehydrated sample was then split into five equal aliquots so each Southern blot or primer extension reaction contained 1/5 of the total sample. Primer extension analysis was performed on three aliquots using three oligonucleotide DNA primers, one per reaction, with Vent exo− polymerase (New England Biolabs) as described previously (39). Primer extension products were electrophoresed through 6% polyacrylamide gels with 7.6 M urea. Gels were dried and autoradiography was performed using a phosphorimager as described for DNA analysis by Southern blotting. The other two aliquots of the sample were analyzed in two Southern blots, one with heat-denatured samples and the other with native DNA (Fig. 7B and E).

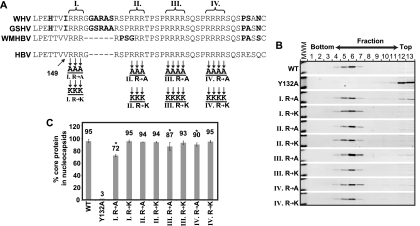

FIG. 2.

Mutations within the CTD have little to no impact on capsid assembly. (A) Alignment of the sequence of CTD of HBV, woolly monkey hepatitis B virus (WMHBV), woodchuck hepatitis B (WHV), and ground squirrel hepatitis B virus (GSHV). Boldface residues indicate differences from the HBV sequence. The sequences of WMHBV, GSHBV, and WHV are from GenBank accession numbers AAO74859.1, K02715.1, and AY628095.1, respectively. The positions of four clusters of arginines—I, II, III, and IV—are also shown. Variants of the HBV core protein are indicated below. Arginines were replaced with either alanines or lysines in each variant. (B) Western blot analysis of velocity sedimentation of cytoplasmic lysates from cells transfected with each of the core variants. Core protein was detected, and a molecular weight marker with bands corresponding to ∼15 and ∼25 kDa is shown in the left lane of each blot (MWM). (C) Quantitation of assembly. Fractions 9 to 13 are considered to be unassembled or improperly assembled core based on comparison to Y132A, a variant that is known to not form capsids (10). For each variant, the proportion of core in fractions 1 to 8 (assembled) is shown as a percent total core protein. Error bars represent ± the 95% confidence interval. Each sample was analyzed a minimum of four times. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference from the WT reference (P < 0.05).

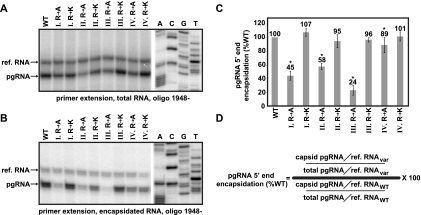

FIG. 3.

Encapsidation of pgRNA. Primer extension using oligo 1948− extended with avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) reverse transcriptase (RT) was used to measure the level of 5′ ends of encapsidated and reference RNAs. (A and B) Representative gels used to measure the encapsidation efficiency of total and encapsidated pgRNA, respectively. In each gel, the positions of the pgRNA and reference RNA (ref. RNA) are indicated. A sequencing ladder is provided for reference. (C) Histogram of the efficiency of encapsidation of the 5′ end of pgRNA, with standard deviations of normalized values represented by error bars. (D) Formula used to calculate encapsidation. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference from the WT reference (P < 0.05).

For simultaneous detection of RNA and DNA by primer extension (as shown in Fig. 4 and 5) a cDNA of pgRNA was generated using AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega) and an unlabeled primer. Subsequently, the sample was incubated 2 h at 37°C with RNase A, precipitated with ethanol, and rehydrated. Primer extension on this mixture of cDNA and (−)DNA using a labeled primer and Vent exo− polymerase was conducted as described previously (39). Oligonucleotides 1556+ and 1857+ were used to detect the 3′ and 5′ ends of pgRNA, respectively (primer sequences given in Table 1, diagrams of the primer annealing sites are shown in Fig. 4A and 5A).

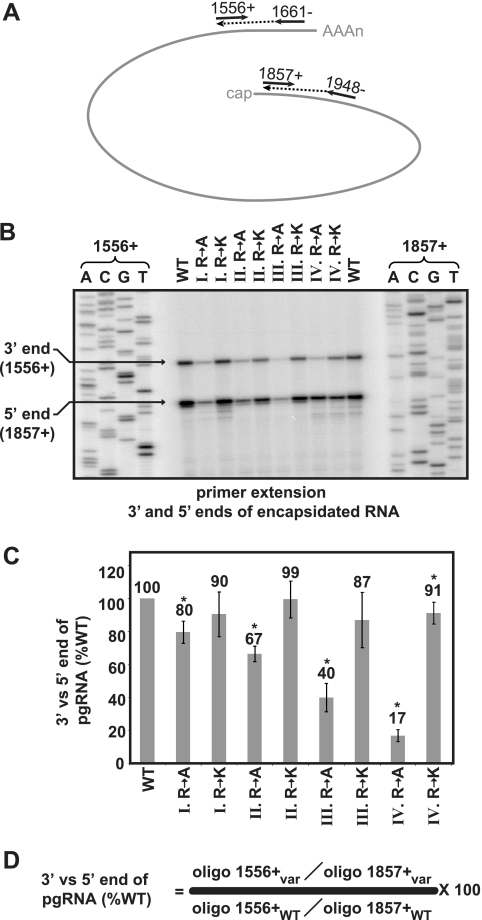

FIG. 4.

Ratio of 3′ to 5′ ends of encapsidated pgRNA. Sequential RNA and DNA primer extension was used to determine the ratio of encapsidated 3′ to 5′ ends of pgRNA. Unlabeled oligos 1948− and 1661− were used to generate cDNAs corresponding to the 5′ and 3′ ends. Radiolabeled oligos 1857+ and 1556+ were subsequently used to detect those cDNAs. (A) A diagram showing this strategy is shown. (B) Representative gel used to determine the ratio of 3′ to 5′ ends. The position of the 3′ and 5′ ends are indicated. Sequencing ladders corresponding to both labeled primers are shown on either side of the gel. (C) A histogram shows the ratio of each variant relative to the wild-type reference. (D) Formula used to calculate the ratio of 3′ to 5′ ends. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference from the WT reference (P < 0.05).

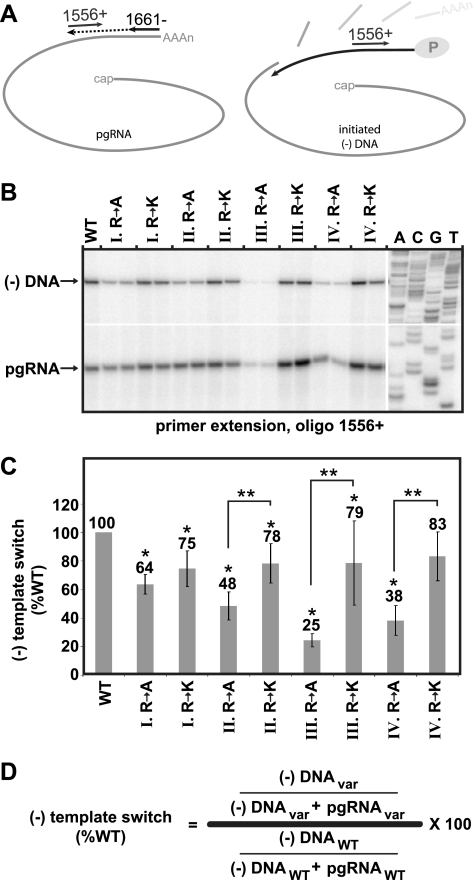

FIG. 5.

Efficiency of minus-strand DNA template switch. (A) The positions of two oligonucleotide primers are shown. Primer 1661− was used to generate a cDNA corresponding to the 3′ end of pgRNA. Radiolabeled oligonucleotide 1556+ was used to detect both the cDNA and minus-strand DNA that has undergone the template switch to DR1. (B) Representative dual primer extension gel with positions of the cDNA corresponding to the pgRNA and minus-strand DNA indicated. A sequencing ladder is shown as a reference. (C) Histogram showing the relative efficiency of (−)DNA template switch of each of the variants as calculated by using the equation shown in panel D. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference from the WT reference (P < 0.05). Double asterisks (**) indicate a significant difference between bracketed variants (P < 0.05).

Statistical analysis.

To determine whether the variants assembled into capsids with different efficiency than wild-type core protein, a two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. If the P value was <0.05, we rejected the null hypothesis that the variant and the wild-type populations were the same. Each variant was analyzed four or more times.

For comparisons in Fig. 3, 4, 5, and 7, we determined whether each variant underwent the step in question at an efficiency different than the wild-type reference. Each variant was analyzed in two or more experiments containing one or more samples of the variant and two or more samples of the wild-type reference. Each variant was analyzed five or more times. Analyzing samples from multiple experiments was accomplished by using a permutation test. Two-sided P values were calculated for the comparison of each variant population to the wild-type reference population using the program Mstat 5.3 (provided by Norman Drinkwater). If the P value was <0.05, the null hypothesis that the two samples were the same was rejected. All statistical analyses were conducted on samples prior to normalization to the wild-type reference.

FIG. 6.

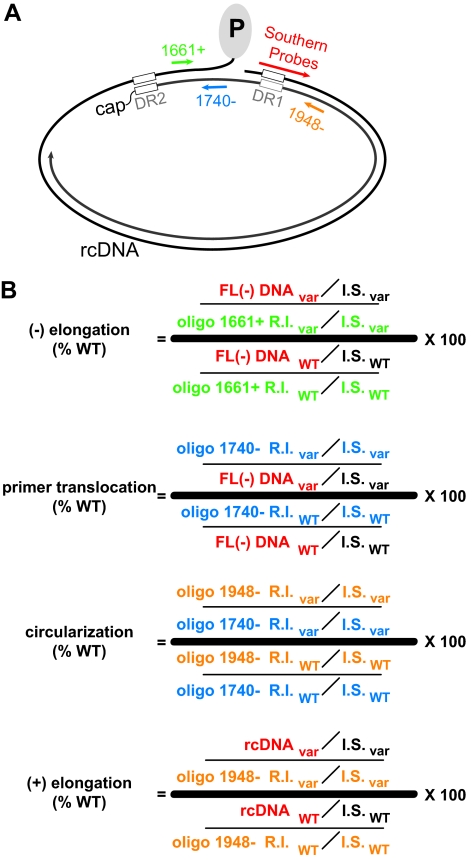

Calculation of efficiency of different steps or stages of DNA synthesis. (A) Position of all oligonucleotide primers and Southern blot hybridization probes used to detect DNA at various stages. Primer extension primers 1661+ (green), 1740+ (blue), and 1948− (orange) were used to detect (−)DNA initiated from DR1, DR2-primed (+)DNA, and circularized (+)DNA, respectively. Southern blotting was used to detect full-length (−)DNA and rcDNA. (B) Equations for calculation of (−) elongation, primer translocation, circularization, (+) elongation. FL (−)DNA is the amount of full-length minus-strand DNA, as detected by Southern blotting (red). Oligo 1661+ R.I. is the amount of minus-strand DNA elongating from DR1, as determined by primer extension with oligon 1661+ (green). Oligo 1740− R.I. is the amount of plus-strand DNA that is initiated at DR2, as detected by primer extension with oligo 1740− (blue). Oligo 1948− R.I. is the amount of plus-strand DNA that is initiated at DR2 and circularized, as detected by primer extension with oligo 1948− (orange). In all cases, a common internal standard DNA (I.S.) was used to normalize and compare the level of viral DNA detected by the different assays and methods. The probes to detect the Southern blot I.S. are specific for a sequence that is not within the HBV genome. A subscript “var” indicates the calculation for a variant. A subscript “WT” indicates the calculation for the wild-type reference. The color of each variable is matched to the probe or primer used to detect that replicative intermediate.

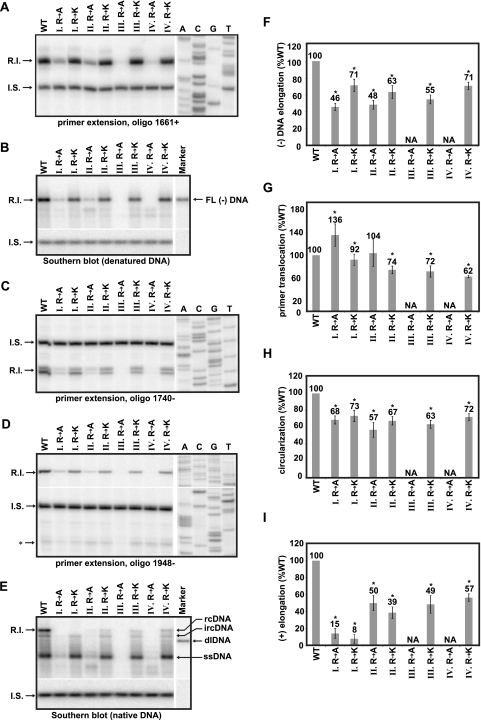

FIG. 7.

Analysis of DNA synthesis efficiency during functionally distinct stages. For all gel images, the positions of the replicative intermediate (R.I.) and internal standard (I.S.) bands that were measured are indicated. (A) Primer extension with oligo 1661+ to detect minus-strand DNA elongated from DR1. (B) Southern blot with heat-denatured DNA to detect full-length minus-strand DNA. (C) Primer extension with oligo 1740− to detect plus-strand DNAs initiated from DR2. (D) Primer extension with oligo 1948− to detect circularized, DR2-initiated plus-strand DNAs. The position of in situ-primed plus-strand DNAs is indicated (*). (E) Southern blot with native DNA. The positions of ssDNA, dlDNA, ircDNA, and full-length rcDNA are indicated. (F thru I). Histograms showing relative efficiency of (−)DNA elongation, primer translocation, circularization, and (+)DNA elongation, as calculated by the equations in Fig. 6. Samples III R to A and IV R to A were not analyzed (NA) because DNA levels were below the limits of quantitative detection due to accumulation of defects at earlier steps in replication. An asterisk (*) indicates a statistically significant difference from the WT reference (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

To engender HBV replication, we transfected HepG2 cells with two plasmids. The pgRNA and P protein were expressed from plasmid EL100 or a derivative. Plasmid EL43 and its derivatives expressed core protein. The EL100 plasmid contains a 4-nt substitution in a frequently used 3′ splice site. This mutation has been shown to prevent formation of most spliced RNAs in cell cultures (1), and it does not have a deleterious effect on replication (data not shown).

To learn whether the individual arginine clusters within the CTD of the core protein are important for function, arginines were replaced with alanines in cluster I, II, III, or IV. We also analyzed lysine substitutions to determine whether the requirement was only that those residues have a positive charge. Eight variants of the core protein were generated (Fig. 2A). The replication of each variant was compared to replication of HBV with the wild-type core protein.

All core protein variants assemble into capsids in transfected cells.

The ability of each variant core protein to assemble into capsids was evaluated by sedimentation velocity centrifugation. Cytoplasmic lysates from cells transfected with each variant were sedimented through a sucrose gradient (Fig. 2B and C). Assembled capsids sediment more rapidly than unassembled core protein. As comparisons, we included a core variant (Y132A) that has previously been shown to form dimers but not capsids (10) and wild-type core protein. We found a small decrease in the proportion of assembled capsids for variants I R to A, III R to A, and IV R to A. However, a majority of core protein was assembled into capsids for all three variants (Fig. 2B and C). We also found that the core protein for variant III R to A resolved as a doublet upon SDS-PAGE analysis. The reason for this doublet is unknown (Fig. 2B). Nevertheless, 87% of the core protein with mutation III R to A assembled into capsids (Fig. 2C). All other variants assembled into capsids at levels similar to wild type.

Arginine clusters contribute to pgRNA encapsidation.

It has been previously shown that the CTD contributes to encapsidation of pgRNA. Either changing serine 155, 162, or 170 (21, 44) or truncating the CTD caused less pgRNA to be encapsidated (8, 37, 47). We determined the ability of the eight variants to encapsidate pgRNA. Cytoplasmic lysates were either treated or not treated with MNase. MNase digests pgRNA that is not encapsidated. The untreated samples contained both encapsidated and unencapsidated pgRNA. All samples were then analyzed by primer extension using oligonucleotide 1948− (Fig. 3A and B). To account for variation in the efficiency of isolation or detection, a reference pgRNA was added to each sample. The reference pgRNA was generated by transfecting a separate culture and mixing the lysates from the reference and experimental cultures prior to isolation of RNA. The reference pgRNA has a 6-nt insertion so it could be distinguished from the experimental pgRNA by primer extension (Fig. 3A and B). To prevent the degradation of pgRNA during DNA synthesis, we inactivated the catalytic site of the P protein by mutation (YMDD to YMHA [51]). The level of pgRNA encapsidation of each variant, relative to the WT reference, was calculated using the indicated formula (Fig. 3D).

Analysis of the four arginine clusters revealed alanine substitutions at positions I, II, and III caused reductions in encapsidation ranging from 58% (II R to A) to 24% (III R to A) the level of the wild-type reference (Fig. 3C). The four variants with lysine substitutions and the variant with alanine substitutions in cluster IV were not different from the wild type (Fig. 3C).

Mutation of the CTD can cause under-representation of the 3′ end of capsid-associated pgRNA.

Kock et al. (34) analyzed encapsidation of pgRNA for a core variant that was truncated after residue 164. They used MNase in their isolation of encapsidated pgRNA and found that the 3′ end was underrepresented relative to the 5′ end. Therefore, we determined whether the 3′ end of pgRNA could be detected with the same efficiency as the 5′ end in capsids comprised of our variants. RNA was isolated from intracellular capsids. To simultaneously detect the 3′ and 5′ ends of pgRNA, we used primer extension. First, cDNA representing the 3′ and 5′ ends of capsid-associated pgRNA was created with unlabeled oligonucleotides 1661− and 1948−. Then, the levels of these cDNAs were measured by primer extension with Vent exo− polymerase and radiolabeled oligonucleotides 1556+ and 1857+ (Fig. 4A and B). The ratio of 3′ to 5′ ends of each variant, relative to the ratio of the wild-type reference, was calculated using the indicated formula (Fig. 4D).

We found that replacing each of the arginine clusters with alanines led to an under-representation of the 3′ end of capsid-associated pgRNA. Variants III R to A and IV R to A had the largest decreases, with ratios of 3′ to 5′ ends that were 40 and 17% of the level of the wild-type reference, respectively (Fig. 4C). Alanine substitutions in cluster IV caused the most pronounced under-representation of the 3′ end, but we saw no decrease in encapsidation of the 5′ end (compare Fig. 4C to Fig. 3C). Lysine substitutions were, mostly, not different from the WT reference (Fig. 4C).

Arginine clusters contribute to (−) template switch.

Synthesis of (−)DNA initiates within the bulge of ɛ. Then, the nascent strand switches templates and anneals within the 3′ copy of DR1 and the synthesis of (−)DNA resumes. For ease of discussion, we refer to these processes collectively as the (−) template switch. Primer extension was used to measure these processes. The assay detected (−)DNA that is at least 270 bases in length. The level of this DNA was normalized to the level of encapsidated 3′ ends of the pgRNA. First, the 3′ end of pgRNA was converted to cDNA using oligonucleotide 1661−. Then, the level of this cDNA and the level of (−)DNA were measured simultaneously in a primer extension reaction with Vent exo− DNA polymerase and oligonucleotide 1556+ (Fig. 5A). Extension products that correspond to the pgRNA and (−)DNA are indicated (Fig. 5B), and the formula used to calculate the level of (−)DNA template switch is indicated (Fig. 5D).

Analysis of the eight variants revealed that the alanine substitutions had the largest decreases relative to the level of the wild-type reference and relative to the levels of lysine substitution variants at positions II, III, and IV. However, lysine substitutions also caused decreases, though more modest in magnitude (Fig. 5C). Variant III R to A had the greatest decrease (25% the level of wild type), and variant IV R to K had the smallest decrease (83% the level of the wild type).

Strategy for quantitative analysis of the subsequent steps of DNA synthesis.

To determine the efficiency of the subsequent steps in DNA replication, for each CTD mutant, we measured the proportion of HBV genomes that had initiated (−)DNA, elongated (−)DNA to completion, primed (+)DNA at DR2, circularized (+)DNA, and elongated rcDNA to completion. The amount of HBV DNA at each step was measured by using either primer extension or Southern blotting. To directly compare measurements obtained by primer extension and Southern blotting, each viral replicative intermediate (R.I.) DNA was normalized to a single I.S. DNA. I.S. DNA was added to each viral DNA sample prior to dividing the sample into five aliquots. DNA in each aliquot was then analyzed by using each of the assays shown in Fig. 7A to E. Initiated (−)DNA was detected by primer extension using oligonucleotide (oligo) 1661+ (Fig. 6A and Fig. 7A). Full-length (−)DNA was detected by Southern blot in which samples were first heat denatured (Fig. 6A and Fig. 7B). (+)DNA initiated at DR2 was measured by primer extension using oligo 1740− (Fig. 6A and Fig. 7C). Circularized (+) DNA was detected by primer extension using oligo 1948− (Fig. 6A and Fig. 7D). Fully elongated rcDNA was detected by Southern blotting in which DNA remained native (Fig. 6A and Fig. 7E). The efficiency of (−)DNA elongation, primer translocation, circularization, and (+)DNA elongation was then calculated using the formulas in Fig. 6B. Alanine substitutions at positions III and IV were not analyzed further because the cumulative sum of the defects in earlier steps prevented analysis of subsequent steps.

Arginine clusters contribute to (−)DNA elongation.

Changing any of the arginine clusters decreased elongation of (−)DNA. Arginine-to-alanine substitutions at positions I and II had the largest decreases, with (−)DNA elongation at 46 and 48% the level of wild type (Fig. 7F). We also found that the lysine substitutions had moderate decreases in (−)DNA elongation ranging from 71% (I R to K) to 55% (III R to K) (Fig. 7F).

Arginine clusters contribute to primer translocation.

Because we did not have a way to directly measure only primer translocation, we measured plus-strand DNA that had undergone primer translocation, initiated synthesis from DR2, and synthesized at least 142 nt as a surrogate. For the ease of discussion, we refer to these steps collectively as primer translocation. We found that the alanine substitutions in clusters I and II did not have a decrease in primer translocation (Fig. 7G). This was in contrast to the effect of alanine substitutions on earlier steps. Conversely, the lysine substitutions in clusters II to IV underwent primer translocation 74 to 62% percent the level of the wild-type reference (Fig. 7G).

The arginine clusters contribute to circularization.

As was the case for primer translocation, the circularization template switch could not be directly evaluated. We measured plus-strand DNA that had undergone circularization, reinitiation at 3′r, and elongated an additional 175 nt as a surrogate. We refer to these steps collectively as circularization. Analysis revealed that mutations in any of the four clusters caused a decrease in circularization, with levels ranging from 73% (I R to K) to 57% (II R to A) the level of the wild-type reference (Fig. 7H). Interestingly, the magnitude of defect was very similar between the arginine and lysine substitutions at positions I (68% I R to A; 73% I R to K) and II (57% I R to A; 67% I R to K). Lysine substitutions at positions III and IV resulted in decreases in circularization.

Arginine clusters contribute to plus-strand DNA elongation.

For the six variants analyzed, plus-strand DNA elongation was diminished relative to the level of the wild-type reference (Fig. 7I). Substitutions in cluster I caused the greatest decrease with elongation efficiency of 15% (I R to A) and 8% (I R to K) the level of the wild-type reference. There was little difference in the magnitude of decrease caused by alanine and lysine substitutions in either cluster I or II (Fig. 7I). Lysine substitutions in clusters III and IV also decreased elongation of (+)DNA.

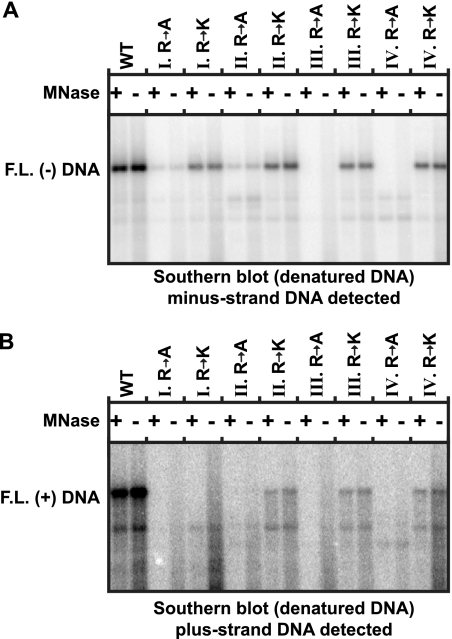

Decreases in accumulation of DNA was not the consequence of increased sensitivity of encapsidated DNA to MNase.

Some mutations within the CTD of the core protein of DHBV increase the susceptibility of mature DNA genomes to digestion with MNase (7, 35). In addition, Guo et al. (24) also found that capsids containing mature HBV genomes lacking covalently attached P protein may be susceptible to digestion with MNase. Therefore, we determined whether the decreases in DNA levels that we observed were due to increased susceptibility to digestion with MNase during isolation of capsid DNA. We compared capsid DNA that was isolated using MNase to samples that were not treated with MNase. The accumulation of full-length minus- and plus-strand DNA was determined by Southern blotting. To remove the transfected plasmid DNA, all samples were treated with DpnI, which digests transfected plasmid DNA but does not digest DNA from capsids. We found that the accumulation of DNA appeared very similar whether or not MNase was used during the isolation procedure (Fig. 8). These results are consistent with findings from previous studies (13, 34, 37). Therefore, we conclude that the decreases we have measured in each step of replication are not due to an increased sensitization of capsid DNA to MNase digestion during its isolation.

FIG. 8.

Capsid mutations do not increase susceptibility of DNA to MNase. HBV DNA was isolated using either MNase or MNase omitted. After isolation, all samples were treated with RNase A and DpnI to digest transfected plasmid DNA and RNA. Subsequent Southern blot analysis on heat-denatured DNA was conducted. Southern blots were probed with minus-strand-specific probes (oligos 1816+, 1833+, 1857+, and 1876+) (A) or a plus-strand-specific riboprobe that spans the full genome length (B).

DISCUSSION

We have analyzed the contribution of the CTD to capsid assembly, pgRNA encapsidation, and DNA synthesis. Core protein variants were generated in which the clusters of arginines in the CTD were replaced with alanines or lysines. We found that each arginine cluster made contributions to pgRNA encapsidation and DNA synthesis.

Replacing arginines with alanines caused a reduction in encapsidation of the 5′ end of pgRNA. Also, we could detect fewer 3′ ends relative to the number of 5′ ends in these variants. An explanation for this phenomenon is that these variants encapsidate the 3′ end of pgRNA more slowly than the 5′ end. Consequently, some pgRNA molecules would have external 3′ ends that would be digested by MNase during isolation. This difference between encapsidation of the 5′ and 3′ ends of pgRNA may be a general property of HBV, but alanine substitutions appear to accentuate it. In contrast, lysine substitutions did not cause changes in encapsidation of pgRNA. One interpretation of these findings is that preserving the charge of each arginine cluster is sufficient for pgRNA encapsidation.

In addition to contributing to encapsidation of pgRNA, the arginine clusters were also found to contribute to DNA synthesis. Replacing any of the arginine clusters with either alanines or lysines decreased (−) template switching and (−)DNA elongation. For these steps, alanine substitutions were more defective than lysine substitutions. Primer translocation was also decreased by arginine to lysine substitutions, but alanine substitutions were tolerated. Finally, circularization and (+) DNA elongation were both decreased when arginines were replaced with alanines or lysines. Furthermore, lysine and alanine substitutions caused defects of similar magnitude in circularization and elongation of (+) DNA. Together, these results suggest that the CTD contributes to DNA synthesis pleiotropically, and preserving the positive charge of the CTD is not sufficient to preserve the function.

There are several hypotheses that could explain why replacing arginines with lysines could cause a pleiotropic defect in DNA synthesis. Arginines may be recognized by the kinase that phosphorylates the CTD. There is evidence to suggest that HBV is phosphorylated by SRPK1 and SRPK2, which phosphorylate serines in regions that are rich with arginine (17). The lysine substitutions may be defective because they are not properly phosphorylated. Alternatively, the differences in size and shape between arginines and lysines may negatively impact the function of the CTD. Subsequent studies are required to test these hypotheses.

Consideration of the charge balance hypothesis.

Le Pogam et al. (37) suggested that the CTD may function by providing the appropriate number of positive charges in the interior of capsids. These charges neutralize the negative charges associated with encapsidated nucleic acids such that a system containing the capsid plus encapsidated nucleic acid is more thermodynamically stable than a system containing the capsid with no nucleic acid. There are two hypotheses for why this charge equivalency may be important. First, the CTD may provide a thermodynamic drive for encapsidation of pgRNA (31, 37). Too few charges in the CTD could cause the pgRNA to either not be encapsidated or only be partially encapsidated. Alternatively, the CTD may protect capsids from being disassembled during encapsidation and DNA synthesis. According to this hypothesis, the negative charges of RNA or DNA would mutually repel one another and exert an outward force on capsids. Positive charges on the CTD reduce this mutual repulsion and prevent it from disrupting capsids.

Our results allow the charge balance hypothesis to be evaluated more thoroughly. First, part of the charge balance hypothesis suggests that the CTD provides a thermodynamic drive for encapsidation (31, 37). Mutations that preserve the charge of the CTD are predicted to be similar to the wild-type reference. We found that replacing arginines with lysines did not cause decreases in encapsidation of the 5′ or 3′ ends of the pgRNA. Therefore, this prediction is met by our results. The hypothesis also predicts that decreasing the charge of the CTD would decrease the amount of encapsidated nucleic acids. We found arginine-to-alanine substitutions all had decreases in encapsidation so this prediction is also met. Together, these results appear to be consistent with the hypothesis that the CTD provides a thermodynamic drive for encapsidation.

The other prediction of the charge balance hypothesis is that capsids will be destabilized if there is not sufficient positive charge in the CTD to neutralize the negatively charged nucleic acids (13, 37, 49). Encapsidation of pgRNA and (+)DNA elongation are the two steps that increase the amount of nucleic acids inside capsids. Therefore, the hypothesis predicts that these steps should be affected by CTD mutation and the other steps should not be affected. Also, only CTD mutations that reduce the positive charge should cause an effect. We found that both pgRNA encapsidation and (+)DNA elongation were affected by CTD mutations. However, lysine substitutions caused as much decrease in (+)DNA elongation as alanine substitutions. Furthermore, the hypothesis predicts that all three template switch steps should not be affected by CTD mutations because these steps cause only negligible increases in the amount of encapsidated nucleic acid. We found that all three template switches were decreased when arginines were replaced with either alanines or lysines. Finally, the hypothesis predicts that synthesis of (−)DNA would not be affected because RNase H digestion of the pgRNA prevents a net increase in the amount of encapsidated nucleic acid. We found that both alanine and lysine substitutions decreased the efficiency of this step. Together, these findings suggest that the charge balance hypothesis does not explain how the CTD contributes to DNA synthesis.

A final prediction of the charge balance hypothesis is that alanine substitutions would result in less of the total core protein being found in assembled capsids as a consequence of capsid disassembly. We found three of the alanine substitution mutants did have small decreases in the proportion of core protein that was found in assembled capsids (Fig. 2; I, III, IV R to A substitutions) relative to the level of the wild-type reference. However, at least one variant (II R to A) was not different from the wild-type reference. Together, we think that our findings are not consistent with the hypothesis that the CTD prevents capsid destabilization by neutralizing the charge of encapsidated DNA or RNA. Therefore, we think that other models to explain the role of the CTD in DNA replication should be considered.

Nucleic acid chaperone hypothesis.

Because the charge balance hypothesis does not seem to adequately explain how the CTD contributes to DNA synthesis, we considered alternative hypotheses. A particularly interesting idea is that the CTD may be functioning as a nucleic acid chaperone (NAC), akin to the NC proteins of retroviruses (for reviews, see references 38 and 52), the Gag-like proteins of retrotransposons (14, 20, 43), or the capsid protein of multiple RNA viruses (15, 45, 63). NACs are proteins that catalyze formation of the correct conformation of nucleic acids. Although the charge balance hypothesis attempts to explain the function of the CTD in terms of thermodynamic benefit, the nucleic acid chaperone hypothesis suggests that the CTD improves the kinetics of replication. These models are not mutually exclusive.

NAC activity is the result of three separate properties. First, NACs aggregate nucleic acids, thereby increasing the probability that complementary single-stranded nucleic acids will encounter one another. Second, they rapidly and nonspecifically bind to single-stranded nucleic acids, causing base-paired structures to have a slight shift toward single-strandedness when viewed as an aggregate. This is thought to facilitate strand invasion by foreign strands that can form base pairs with one strand in a preexisting duplex. Finally, they rapidly release bound nucleic acids to prevent a progressive conversion to single strands. The mechanisms for this action are reviewed in reference 52.

Proteins with this activity are extremely common among reverse transcribing viruses and single-stranded RNA viruses that do not encode an RNA helicase. In the case of hepatitis B virus, a NAC may be required to improve procession of the polymerase through secondary structures. By analogy, the retroviral NC proteins are essential for polymerase procession through secondary structures (18, 30, 33, 67, 68). Similarly, formation of long-range base paired structures may be facilitated by a NAC akin to the way retroviral NC or NC-like proteins (in LTR retrotransposons) facilitate the rearrangements that occur during genomic RNA dimerization and primer tRNA binding (14, 26, 27, 29, 54, 55). Finally, the actual DNA strand transfers may be catalyzed, akin to how retroviral NC proteins catalyze the minus- and plus-strand transfers for those viruses (4, 46, 67). The results of the present study do not directly test the hypothesis that the CTD is a NAC. However, our results are consistent with this hypothesis. We therefore feel that direct tests to determine whether the CTD is a NAC could yield valuable insights.

Finally, the present study raises the question of whether these arginine clusters function additively or synergistically. The charge balance hypothesis predicts that each arginine cluster should make an additive contribution. Because our data support the idea that encapsidation is promoted via this mechanism, we predict that the four clusters would contribute to encapsidation additively. For the subsequent steps, however, the predictions are less obvious. NAC activity could conceivably originate from either a single functional unit or from several independent modules. If the CTD functions as a single unit or as modules that function in a highly cooperative fashion, we would predict that the activity of the CTD as a whole would drop off after some threshold number of mutations was made. In contrast, if the arginine clusters are part of independent modules, an additive function is more likely. In either case, future studies investigating various combinations of arginine mutations could provide valuable insights.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Lentz, Megan Maguire, Teresa Abraham, Katy Haines, Dan Yuan, and Natalie Greco for thoughtful and constructive criticism during the course of these studies.

This study was supported by NIH grants R01 AI060018, P01 CA022443, and T32 CA009135.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham, T. M., E. B. Lewellyn, K. M. Haines, and D. D. Loeb. 2008. Characterization of the contribution of spliced RNAs of hepatitis B virus to DNA synthesis in transfected cultures of Huh7 and HepG2 cells. Virology 379:30-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham, T. M., and D. D. Loeb. 2006. Base pairing between the 5′ half of epsilon and a cis-acting sequence, phi, makes a contribution to the synthesis of minus-strand DNA for human hepatitis B virus. J. Virol. 80:4380-4387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abraham, T. M., and D. D. Loeb. 2007. The topology of hepatitis B virus pregenomic RNA promotes its replication. J. Virol. 81:11577-11584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auxilien, S., G. Keith, S. F. Le Grice, and J. L. Darlix. 1999. Role of posttranscriptional modifications of primer tRNALys,3 in the fidelity and efficacy of plus strand DNA transfer during HIV-1 reverse transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 274:4412-4420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartenschlager, R., M. Junker-Niepmann, and H. Schaller. 1990. The P gene product of hepatitis B virus is required as a structural component for genomic RNA encapsidation. J. Virol. 64:5324-5332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartenschlager, R., and H. Schaller. 1992. Hepadnaviral assembly is initiated by polymerase binding to the encapsidation signal in the viral RNA genome. EMBO J. 11:3413-3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basagoudanavar, S. H., D. H. Perlman, and J. Hu. 2007. Regulation of hepadnavirus reverse transcription by dynamic nucleocapsid phosphorylation. J. Virol. 81:1641-1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beames, B., and R. E. Lanford. 1993. Carboxy-terminal truncations of the HBV core protein affect capsid formation and the apparent size of encapsidated HBV RNA. Virology 194:597-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bottcher, B., S. A. Wynne, and R. A. Crowther. 1997. Determination of the fold of the core protein of hepatitis B virus by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature 386:88-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourne, C. R., S. P. Katen, M. R. Fulz, C. Packianathan, and A. Zlotnick. 2009. A mutant hepatitis B virus core protein mimics inhibitors of icosahedral capsid self-assembly. Biochemistry 48:1736-1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, Y., and P. L. Marion. 1996. Amino acids essential for RNase H activity of hepadnaviruses are also required for efficient elongation of minus-strand viral DNA. J. Virol. 70:6151-6156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiang, P. W., K. S. Jeng, C. P. Hu, and C. M. Chang. 1992. Characterization of a cis element required for packaging and replication of the human hepatitis B virus. Virology 186:701-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chua, P. K., F. M. Tang, J. Y. Huang, C. S. Suen, and C. Shih. 2010. Testing the balanced electrostatic interaction hypothesis of hepatitis B virus DNA synthesis by using an in vivo charge rebalance approach. J. Virol. 84:2340-2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cristofari, G., D. Ficheux, and J. L. Darlix. 2000. The GAG-like protein of the yeast Ty1 retrotransposon contains a nucleic acid chaperone domain analogous to retroviral nucleocapsid proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 275:19210-19217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cristofari, G., et al. 2004. The hepatitis C virus Core protein is a potent nucleic acid chaperone that directs dimerization of the viral positive-strand RNA in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:2623-2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crowther, R. A., et al. 1994. Three-dimensional structure of hepatitis B virus core particles determined by electron cryomicroscopy. Cell 77:943-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daub, H., et al. 2002. Identification of SRPK1 and SRPK2 as the major cellular protein kinases phosphorylating hepatitis B virus core protein. J. Virol. 76:8124-8137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drummond, J. E., et al. 1997. Wild-type and mutant HIV type 1 nucleocapsid proteins increase the proportion of long cDNA transcripts by viral reverse transcriptase. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 13:533-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dryden, K. A., et al. 2006. Native hepatitis B virions and capsids visualized by electron cryomicroscopy. Mol. Cell 22:843-850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabus, C., et al. 2006. Characterization of a nucleocapsid-like region and of two distinct primer tRNALys,2 binding sites in the endogenous retrovirus Gypsy. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:5764-5777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gazina, E. V., J. E. Fielding, B. Lin, and D. A. Anderson. 2000. Core protein phosphorylation modulates pregenomic RNA encapsidation to different extents in human and duck hepatitis B viruses. J. Virol. 74:4721-4728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerlich, W. H., and W. S. Robinson. 1980. Hepatitis B virus contains protein attached to the 5′ terminus of its complete DNA strand. Cell 21:801-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gunther, S., G. Sommer, A. Iwanska, and H. Will. 1997. Heterogeneity and common features of defective hepatitis B virus genomes derived from spliced pregenomic RNA. Virology 238:363-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo, H., R. Mao, T. M. Block, and J. T. Guo. 2010. Production and function of the cytoplasmic deproteinized relaxed circular DNA of hepadnaviruses. J. Virol. 84:387-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haines, K. M., and D. D. Loeb. 2007. The sequence of the RNA primer and the DNA template influence the initiation of plus-strand DNA synthesis in hepatitis B virus. J. Mol. Biol. 370:471-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hargittai, M. R., R. J. Gorelick, I. Rouzina, and K. Musier-Forsyth. 2004. Mechanistic insights into the kinetics of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein-facilitated tRNA annealing to the primer binding site. J. Mol. Biol. 337:951-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hargittai, M. R., A. T. Mangla, R. J. Gorelick, and K. Musier-Forsyth. 2001. HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein zinc finger structures induce tRNA(Lys,3) structural changes but are not critical for primer/template annealing. J. Mol. Biol. 312:985-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatton, T., S. Zhou, and D. N. Standring. 1992. RNA- and DNA-binding activities in hepatitis B virus capsid protein: a model for their roles in viral replication. J. Virol. 66:5232-5241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwatani, Y., A. E. Rosen, J. Guo, K. Musier-Forsyth, and J. G. Levin. 2003. Efficient initiation of HIV-1 reverse transcription in vitro. Requirement for RNA sequences downstream of the primer binding site abrogated by nucleocapsid protein-dependent primer-template interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 278:14185-14195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ji, X., G. J. Klarmann, and B. D. Preston. 1996. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) nucleocapsid protein on HIV-1 reverse transcriptase activity in vitro. Biochemistry 35:132-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang, T., Z. G. Wang, and J. Wu. 2009. Electrostatic regulation of genome packaging in human hepatitis B virus. Biophys. J. 96:3065-3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Junker-Niepmann, M., R. Bartenschlager, and H. Schaller. 1990. A short cis-acting sequence is required for hepatitis B virus pregenome encapsidation and sufficient for packaging of foreign RNA. EMBO J. 9:3389-3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klasens, B. I., H. T. Huthoff, A. T. Das, R. E. Jeeninga, and B. Berkhout. 1999. The effect of template RNA structure on elongation by HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1444:355-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kock, J., M. Nassal, K. Deres, H. E. Blum, and F. von Weizsacker. 2004. Hepatitis B virus nucleocapsids formed by carboxy-terminally mutated core proteins contain spliced viral genomes but lack full-size DNA. J. Virol. 78:13812-13818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kock, J., S. Wieland, H. E. Blum, and F. von Weizsacker. 1998. Duck hepatitis B virus nucleocapsids formed by N-terminally extended or C-terminally truncated core proteins disintegrate during viral DNA maturation. J. Virol. 72:9116-9120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lanford, R. E., L. Notvall, and B. Beames. 1995. Nucleotide priming and reverse transcriptase activity of hepatitis B virus polymerase expressed in insect cells. J. Virol. 69:4431-4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le Pogam, S., P. K. Chua, M. Newman, and C. Shih. 2005. Exposure of RNA templates and encapsidation of spliced viral RNA are influenced by the arginine-rich domain of human hepatitis B virus core antigen (HBcAg 165-173). J. Virol. 79:1871-1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levin, J. G., J. Guo, I. Rouzina, and K. Musier-Forsyth. 2005. Nucleic acid chaperone activity of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein: critical role in reverse transcription and molecular mechanism. Prog. Nucleic Acids Res. Mol. Biol. 80:217-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewellyn, E. B., and D. D. Loeb. 2007. Base pairing between cis-acting sequences contributes to template switching during plus-strand DNA synthesis in human hepatitis B virus. J. Virol. 81:6207-6215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liao, W., and J. H. Ou. 1995. Phosphorylation and nuclear localization of the hepatitis B virus core protein: significance of serine in the three repeated SPRRR motifs. J. Virol. 69:1025-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu, N., L. Ji, M. L. Maguire, and D. D. Loeb. 2004. cis-Acting sequences that contribute to the synthesis of relaxed-circular DNA of human hepatitis B virus. J. Virol. 78:642-649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu, N., K. M. Ostrow, and D. D. Loeb. 2002. Identification and characterization of a novel replicative intermediate of heron hepatitis B virus. Virology 295:348-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin, S. L., and F. D. Bushman. 2001. Nucleic acid chaperone activity of the ORF1 protein from the mouse LINE-1 retrotransposon. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:467-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Melegari, M., S. K. Wolf, and R. J. Schneider. 2005. Hepatitis B virus DNA replication is coordinated by core protein serine phosphorylation and HBx expression. J. Virol. 79:9810-9820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mir, M. A., and A. T. Panganiban. 2006. Characterization of the RNA chaperone activity of hantavirus nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol. 80:6276-6285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muthuswami, R., et al. 2002. The HIV plus-strand transfer reaction: determination of replication-competent intermediates and identification of a novel lentiviral element, the primer over-extension sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 315:311-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nassal, M. 1992. The arginine-rich domain of the hepatitis B virus core protein is required for pregenome encapsidation and productive viral positive-strand DNA synthesis but not for virus assembly. J. Virol. 66:4107-4116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nassal, M., and A. Rieger. 1996. A bulged region of the hepatitis B virus RNA encapsidation signal contains the replication origin for discontinuous first-strand DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 70:2764-2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newman, M., P. K. Chua, F. M. Tang, P. Y. Su, and C. Shih. 2009. Testing an electrostatic interaction hypothesis of hepatitis B virus capsid stability by using an in vitro capsid disassembly/reassembly system. J. Virol. 83:10616-10626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pollack, J. R., and D. Ganem. 1993. An RNA stem-loop structure directs hepatitis B virus genomic RNA encapsidation. J. Virol. 67:3254-3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Radziwill, G., W. Tucker, and H. Schaller. 1990. Mutational analysis of the hepatitis B virus P gene product: domain structure and RNase H activity. J. Virol. 64:613-620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rajkowitsch, L., et al. 2007. RNA chaperones, RNA annealers and RNA helicases. RNA Biol. 4:118-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rieger, A., and M. Nassal. 1996. Specific hepatitis B virus minus-strand DNA synthesis requires only the 5′ encapsidation signal and the 3′-proximal direct repeat DR1. J. Virol. 70:585-589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rong, L., et al. 2001. HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein and the secondary structure of the binary complex formed between tRNA(Lys,3) and viral RNA template play different roles during initiation of (−) strand DNA reverse transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 276:47725-47732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rong, L., et al. 1998. Roles of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein in annealing and initiation versus elongation in reverse transcription of viral negative-strand strong-stop DNA. J. Virol. 72:9353-9358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seeger, C., D. Ganem, and H. E. Varmus. 1986. Biochemical and genetic evidence for the hepatitis B virus replication strategy. Science 232:477-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seeger, C., F. Zoulim, and W. S. Mason. 2007. Hepadnaviruses, p. 2977-3029. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott/The Williams & Wilkins Co., Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seifer, M., and D. N. Standring. 1993. Recombinant human hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase is active in the absence of the nucleocapsid or the viral replication origin, DR1. J. Virol. 67:4513-4520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seifer, M., S. Zhou, and D. N. Standring. 1993. A micromolar pool of antigenically distinct precursors is required to initiate cooperative assembly of hepatitis B virus capsids in Xenopus oocytes. J. Virol. 67:249-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Staprans, S., D. D. Loeb, and D. Ganem. 1991. Mutations affecting hepadnavirus plus-strand DNA synthesis dissociate primer cleavage from translocation and reveal the origin of linear viral DNA. J. Virol. 65:1255-1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tavis, J. E., and D. Ganem. 1993. Expression of functional hepatitis B virus polymerase in yeast reveals it to be the sole viral protein required for correct initiation of reverse transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:4107-4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tavis, J. E., S. Perri, and D. Ganem. 1994. Hepadnavirus reverse transcription initiates within the stem-loop of the RNA packaging signal and employs a novel strand transfer. J. Virol. 68:3536-3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang, C. C., et al. 2003. Nucleic acid binding properties of the nucleic acid chaperone domain of hepatitis delta antigen. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:6481-6492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang, G. H., and C. Seeger. 1993. Novel mechanism for reverse transcription in hepatitis B viruses. J. Virol. 67:6507-6512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang, G. H., and C. Seeger. 1992. The reverse transcriptase of hepatitis B virus acts as a protein primer for viral DNA synthesis. Cell 71:663-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Will, H., et al. 1987. Replication strategy of human hepatitis B virus. J. Virol. 61:904-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu, W., et al. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein reduces reverse transcriptase pausing at a secondary structure near the murine leukemia virus polypurine tract. J. Virol. 70:7132-7142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang, W. H., C. K. Hwang, W. S. Hu, R. J. Gorelick, and V. K. Pathak. 2002. Zinc finger domain of murine leukemia virus nucleocapsid protein enhances the rate of viral DNA synthesis in vivo. J. Virol. 76:7473-7484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhou, S., and D. N. Standring. 1992. Hepatitis B virus capsid particles are assembled from core-protein dimer precursors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:10046-10050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zlotnick, A., et al. 1996. Dimorphism of hepatitis B virus capsids is strongly influenced by the C terminus of the capsid protein. Biochemistry 35:7412-7421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zlotnick, A., et al. 1997. Localization of the C terminus of the assembly domain of hepatitis B virus capsid protein: implications for morphogenesis and organization of encapsidated RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:9556-9561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zoulim, F., and C. Seeger. 1994. Reverse transcription in hepatitis B viruses is primed by a tyrosine residue of the polymerase. J. Virol. 68:6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]