Abstract

One proposed HIV vaccine strategy is to induce Gag-specific CD8+ T-cell responses that can corner the virus, through fitness cost of viral escape and unavailability of compensatory mutations. We show here that the most variable capsid residues principally comprise escape mutants driven by protective alleles HLA-B*57, -5801, and -8101 and covarying HLA-independent polymorphisms that arise in conjunction with these escape mutations. These covarying polymorphisms are potentially compensatory and are concentrated around three tropism-determining loops of p24, suggesting structural interdependencies. Our results demonstrate complex patterns of adaptation of HIV under immune selection pressure, the understanding of which should aid vaccine design.

CD8+ T cells play a pivotal role in the control of HIV-1 infection (3, 21, 29). In particular, increased breadth of Gag-specific CD8+ T-cell responses is strongly associated with lower viral loads (18, 20). Although the selection of viral mutations allows escape from these responses, which can lead to loss of control of viremia (1, 11, 16), the detrimental effects of specific escape mutations on viral replicative capacity are now well documented (4, 6, 9, 10, 24, 31, 36). Furthermore, accumulation of HLA-B-associated Gag escape mutations is linked with lowered viral loads (25). However, escape mutations that reduce viral fitness drive the selection of variants that compensate for reduced function (5, 10, 14, 28, 30, 35). These compensatory mutations can occur in the same epitope (10, 31) or at sites both proximal and distal to the epitope (5, 22, 24, 31). Defining the Gag residues that cannot vary without significant cost to viral replicative capacity, or for which adequate compensatory mutants are not available, is relevant to determining which CD8+ T-cell responses an effective HIV vaccine needs to induce.

One such compensatory mutation is H219Q in HIV-1 p24 Gag. This mutation is not consistently seen in the context of one particular HLA allele, but previous studies of HIV-1 B-clade infection have noted a significant association with the T242N escape mutation in the HLA-B*57 and -5801 (HLA-B*57/5801)-restricted epitope TW10 (Gag HXB2 240 to 249) (5, 22, 24) and with escape mutations in the HLA-B*27-restricted epitope KK10 (Gag HXB2 263 to 272) (30, 31). In addition, this mutation was found to recover reduced replicative capacity caused by drug resistance mutations in HIV-1 protease (14). Thus, the H219Q substitution may represent a generic strategy by which HIV can compensate for reductions in viral fitness, rather than a specific association with selection by a particular HLA allele.

H219 sits within the cyclophilin A (CypA)-binding loop that spans Gag residues 214 to 225. This region is one of three “tropism-determining loops” in the N-terminal domain (NTD; HXB2 residues 133 to 279) of p24 Gag that have been defined as nonconserved regions on the outer surface of the capsid, which interact with host cellular factors (17). These three loops undergo coincident conformational shifts, suggesting that they may operate as a structural and functional unit (33). Furthermore, sequencing studies have revealed clusters of mutations in these regions that arise in the context of HLA-B*57 CD8+ T-cell escape mutations but do not fall in known HLA-B*57 epitopes (5, 24).

These observations prompted us to investigate the extent to which amino acid polymorphisms in the p24 NTD represent HLA-driven escape mutants or are “HLA-independent” polymorphisms, potentially capable of compensating for the fitness hit of escape mutations. (These HLA-independent changes are independent, conditioned on direct associations; that is, they are not directly selected by CD8+ T cells).

We studied two cohorts of antiretroviral therapy-naïve study subjects with chronic HIV-1 C-clade infection, recruited from outpatient clinics in Durban, South Africa (n = 662 patients), as previously described (22, 24, 25) and from the Zambia-Emory HIV Research Project cohort, Lusaka, Zambia (n = 87 patients), as previously described (9). Research protocols were approved by the ethics committees in Durban, South Africa, and Lusaka, Zambia, and by Oxford and Emory University Institutional Review Boards. All study subjects gave written informed consent. For South African subjects, genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC); amplification and population sequencing were undertaken as previously described (19, 22). Longitudinal sequence data were generated from RNA sequences from acutely infected Zambian subjects as previously described (9). Sequences were analyzed using Sequencher 4.8 (Gene Codes Corp.). HLA class I typing was performed from genomic DNA as previously described (7, 34). Plasma viral loads were determined using an Amplicor HIV-1 monitor test, version 1.5 (Roche).

In the South African cohort, H219X (X is Q, P, or R) was seen in 11% of sequences in an analysis of 633 subjects for whom viral loads were available. We found no statistical association between H219X and HLA-B*57/5801 (H219X occurred in 9% of HLA-B*57/5801-positive individuals and in 12% of individuals without HLA-B*57/5801). Individuals with H219Q had higher viral loads, irrespective of HLA type (median viral load was 78,850, versus 29,200 copies/ml; P = 0.004, Mann-Whitney U test; data not shown), consistent with a fitter virus in the presence of this polymorphism.

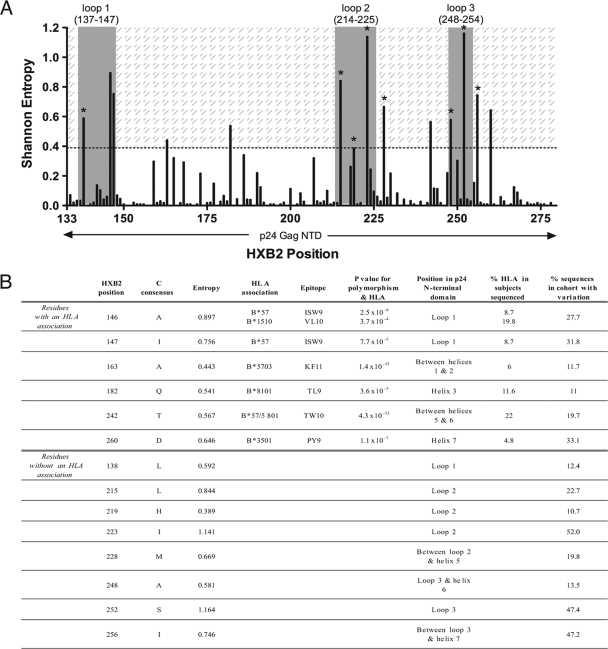

In order to locate other putative HLA-independent compensatory mutations, we identified “high-variability” positions in the p24 NTD by analyzing amino acid sequences using the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) database Shannon entropy tool (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/ENTROPY/entropy) (Fig. 1A). We defined high variability as residues with entropy at least as great as that of position 219 (entropy score, ≥0.389) (Fig. 1B). Of 14 high-variability residues identified in this way, 12 were situated in or flanking (±6 amino acids) the three tropism-determining loops in Gag (loop 1, HXB2 137 to 147; loop 2, 214 to 225; loop 3, 248 to 254) (17) (Fig. 1A). Indeed, significantly higher entropy scores were found for all residues in the three tropism-determining loops than in the rest of p24 NTD (P = 0.0038, Mann-Whitney U test; data not shown). However, not all residues within this region are variable: the crucial proline residues at positions 217 and 222 are conserved in 100% of cases in our cohort of 662 subjects. Therefore, these outer loops contain residues that are either unchangeable (to ensure correct interactions and structure that are vital to replication) or malleable, within limits (to restabilize the capsid when necessary).

FIG. 1.

Amino acid variability in Gag p24 NTD. (A) Shannon entropy of p24 NTD amino acid sequences from 662 C-clade HIV-1 isolates. The three exposed tropism-determining loops are shown (gray bars). The shaded area represents entropy scores of ≥0.389 (entropy equal to or greater than that of position 219). Eight high-variability residues not statistically associated with any HLA class I allele are marked with an asterisk; six of these fall within the three loops. (B) Fourteen high-variability residues in p24 NTD (entropy score, ≥0.389). Top, six residues at which polymorphism is strongly associated with one or more HLA class I alleles. Bottom, eight residues at which polymorphism is not associated with HLA. HLA associations are previously described (25); for all associations, q was <0.05.

An independent analysis of p24 sequences from 350 chronically infected C-clade Zambian individuals revealed an identical entropy pattern, with the same 14 residues displaying the highest entropy scores in this protein (data not shown).

Six of the 14 high-variability residues we identified have previously been associated with selection by HLA alleles in this cohort (q < 0.05) (25) and are situated in defined CD8+ T-cell epitopes (Fig. 1B, top panel). The high entropy of these specific residues compared to the low or zero entropy scores for the rest of the epitope suggests that there are constraints on permitted mutations. Of note, in 5 of 6 cases, these polymorphisms are well-described escape mutants within CD8+ T-cell epitopes restricted by the protective HLA alleles B*57/5801/8101 (10, 19, 22), highlighting the strong selection pressure operated by these alleles to drive viral polymorphisms (25). Of the eight high-variability residues where variation was not HLA driven (Fig. 1B, bottom panel), six (L138, L215, H219, I223, A248, and S252) were situated in the three tropism-determining loops; the remaining two (M228 and I256) were located three and six residues downstream of loops 2 and 3, respectively (Fig. 1B and 2A).

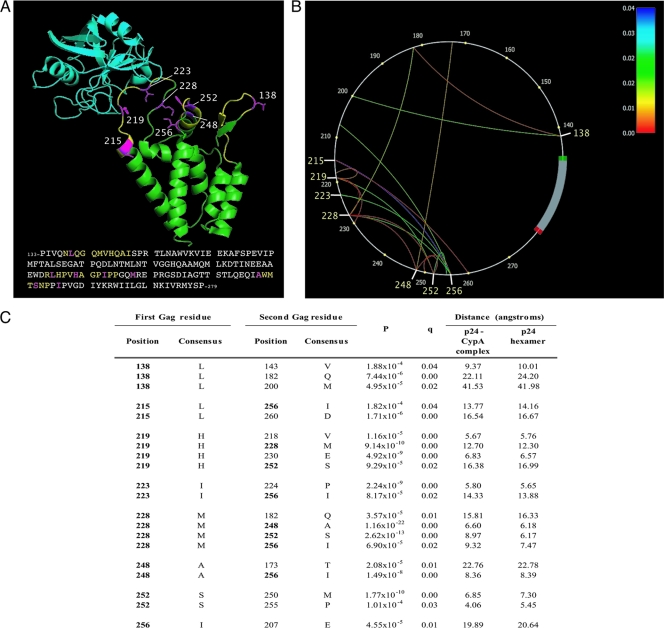

FIG. 2.

Location and covariation of high-variability amino acid residues in Gag p24 NTD. (A) Ribbon diagram of CypA (turquoise) bound to the HIV-1 Gag p24 NTD (green). The three loops are shown in yellow; eight high-variability residues, including H219, are shown in pink with side chains. Adapted from reference 12 (Protein Data Bank [PDB] code 1AK4). C-clade LANL consensus sequence is shown. (B) Phylogenetic dependency network for eight high-variability p24 residues (HXB2 positions 138, 215, 219, 223, 228, 248, 252, and 256) in 662 sequences from Durban, South Africa. Gag p24 is drawn counterclockwise, with the first NTD residue (HXB2 position 133) at the 3 o'clock position. Arcs indicate associations between amino acids (covariation). All associations are statistically significant (q < 0.05); the colors of the arcs correspond to q values. (C) Covariation of eight high-variability HLA-independent residues (in bold) with other Gag residues (for all covarying pairs, q was <0.05; P values are as shown). Consensus C-clade amino acid sequence derived from LANL (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov). Minimum distances between the carbon atoms (C-beta distance) of covarying residues in the folded p24 protein structure, determined by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, are shown. For any amino acid, C-alpha is the carbon atom next to the carbonyl group. In the side chain of an amino acid, the first carbon atom branching from C-alpha in the backbone is called C-beta; the C-beta distance is the distance between two C-beta atoms.

In order to determine whether these eight high-variability HLA-independent polymorphisms might covary with each other and with described CD8+ T-cell escape mutations, and thereby represent putative compensatory substitutions, we investigated the relationship between these eight residues and other residues in the NTD of p24 Gag. We used a computational method to construct phylogenetic dependency networks to screen for associations with all NTD residues (8). We identified 20 statistically significant associations (q < 0.05) between the variation at these eight residues and the variation at other positions (Fig. 2A and B), which may indicate coevolution of this variability (2, 15). Of these 20 associations, eight represent a covariation of residues within the group of eight HLA-independent, high-variability positions (Fig. 2B). We also observed significant associations between the covarying cluster of eight HLA-independent polymorphisms and five of seven HLA-selected mutations in the NTD that have previously been reported (25) to impose a cost on viral replicative capacity (a fitness cost was inferred by detecting reversion) (Table 1). These polymorphisms in the NTD of p24 Gag thus statistically occur in a cluster that includes the known compensatory mutation H219X and covary with fitness-reducing escape mutations.

TABLE 1.

Significant associations between costly HLA-selected escape mutations and high-variability HLA-independent polymorphisms

| HXB2 position of HLA-selected escape mutation | Epitope (position of mutation) | Selecting HLA-B allele |

P value for indicated HXB2 position of HLA-independent polymorphisma |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 138 | 215 | 219 | 223 | 228 | 248 | 252 | 256 | |||

| 146 | ISW9 (−1) | 1510/5702/5703 | — | — | — | — | 2.0 × 10−3 | — | — | — |

| 147 | ISW9 (1) | 5702/5703 | — | — | — | 1.6 × 10−3 | — | — | — | 0.001 |

| 177 | TL9 (−3) | 81(01) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 182 | TL9 (3) | 4201/8101 | 7.4 × 10−6 | — | — | — | 3.6 × 10−5 | — | 9.1 × 10−4 | 2.2 × 10−3 |

| 186 | TL9 (7) | 8101 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 6.7 × 10−5 |

| 242 | TW10 (3) | 5702/5703/5801 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 247 | TW10 (8) | 5703 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 7.0 × 10−4 | 4.0 × 10−8 |

q was <0.2 for all associations reported as significant. —, not significant.

We next investigated the spatial proximity of these eight high-variability HLA-independent residues on the three-dimensional p24 NTD protein structure using MacPyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC) (Fig. 2A). There is a likely structural basis for the covariation in Gag, reflected by the fact that 10 of the 20 associations are between residues that are within 12 Å of each other (the maximum distance to permit hydrophobic interactions [33, 37]), both in the p24-CypA complex (12) and in the p24 hexameric protein structure (27) (Fig. 2B). In addition, distances between residues in these 20 pairs were found to be significantly shorter than distances between all non-coevolving pairs in the NTD (for the p24-CypA complex, the P value was 2.45 × 10−6; for the p24 hexamer, the P value was 3.20 × 10−6 [Mann-Whitney U test]). It should be noted, however, that distances of >12 Å do not necessarily mean that residues cannot interact; long-range effects are possible (26), or two covarying residues may be in close spatial proximity at the interface of two p24 monomers when they are packaged into conical cores (23, 28).

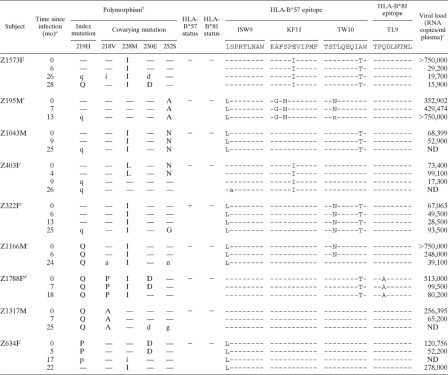

To investigate the dynamics of coselection of mutations in this cluster, we studied longitudinal sequence data, focusing on the best-characterized residue of this group, H219 (Table 2). We identified nine subjects in whom the H219X polymorphism was either transmitted or selected, in conjunction with changes at its four covarying sites (218V, 228M, 230E, and 252S) (Fig. 2B). In five subjects, H219Q was selected between 9 and 27 months posttransmission, following earlier changes at other covarying sites (M228I, S252A/N). In four subjects, H219P/Q was detected at baseline and covarying mutations subsequently arose (V218A/I/P, M228I/L, E230D, S252G/N). H219 substitutions were associated with changes in HLA-B*57- and/or -B*81-restricted epitopes in 8 of 9 subjects, although only one of these was HLA-B*57/81 positive (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Evolving or transmitted mutations at Gag 219 and covarying sites in nine Zambian adults with acute HIV-1 infection

Time point at which mutation was first detected.

Lowercase letters indicate a mixture of amino acids, including the wild type. —, wild type.

HLA-B*57-positive donor.

HLA-B*81-positive donor.

ND, not determined.

In summary, these studies highlight a cluster of covarying high-variability polymorphisms concentrated within three tropism-determining loops in the NTD region of p24 Gag. We postulate a compensatory role for the HLA-independent polymorphisms, based first on their covariation with one another and with CD8+ T-cell escape mutations, second on their close spatial proximity in the three-dimensional structure of p24 Gag, and third on cross-sectional and longitudinal sequence data from two independent cohorts showing that they arise in conjunction with escape mutations. Compensatory mutations may preferentially be selected in the three loops because certain residues in these regions are more likely to tolerate substitutions without a detriment to replicative capacity.

Indeed, in other studies, the same covarying residues have been shown to be beneficial: the results of the present analysis are consistent with reported in vivo covariation in HLA-B*57-positive subjects (5, 24) and with in vitro evidence that H219Q, I223V, M228I, and G248A in a B-clade T242N escape variant are associated with increased replicative capacity (5). It is possible that this cluster of Gag polymorphisms compensates for mutations in certain regions that destabilize or alter the capsid structure (5, 24, 30). A study of mother-to-child transmission noted a similar beneficial effect of this compensatory cluster, demonstrating that these polymorphisms can increase viral fitness, while also abrogating the benefit of HLA-B*57 (32).

Our data substantiate the view that polymorphisms at H219 and other high-variability residues in Gag p24 NTD are not specifically associated with one particular HLA allele or escape mutation but arise in conjunction with a variety of mutations that are detrimental to viral replicative capacity (Tables 1 and 2). Indeed, in these C-clade data sets, H219X is not statistically associated with any individual CD8+ T-cell escape mutation in the p24 NTD. Thus, the association of H219X with variability at multiple residues obscures covariation with any one site. Interestingly, escape mutations selected by HLA-B*8101 (which, like HLA-B*57 and -B*27, is associated with favorable control of viremia) are also found to be strongly associated with four of eight putative compensatory mutations.

Our studies of H219 raise a question: if H219Q is even marginally beneficial to the virus, why is it not selected over the wild type in every HIV-infected individual? Indeed, this mutation results in increased replicative capacity independent of changes in HLA-B*57 epitopes (4, 13). It is possible that other substitutions in p24 are necessary before H219Q and associated polymorphisms can be selected, due to conformational changes or interactions affecting the loops. The HLA-B*57-associated T242N mutation, situated in helix 6, potentially changes the conformation of this helix and alters its interactions with the CypA-binding loop (24). Other evidence that compensatory mutations may be selected only in the context of pre-existing escape mutations comes from studies in which compensatory mutations had deleterious effects on the wild-type virus after experimental reversion of costly escape mutations (26). Our longitudinal data show that covarying mutations at positions H219, V218, M228, E230, and S252 arise in no consistent order but are observed in the presence of HLA-B*57- and/or -B*81-selected mutations.

Our findings demonstrate that HIV polymorphisms may arise in the context of a complex set of interrelated substitutions that reflect structural dependencies among amino acids. Codon covariation can be a confounding effect in the identification of sources of selection pressures on the virus, highlighting the importance of factoring this into HIV-HLA association studies. Our results emphasize the value of examining amino acid sequences not only in their linear form but also in their three-dimensional physiologically relevant form. Future studies are required to identify which of the HLA-independent sites of polymorphism truly act to compensate for a fitness cost of CD8+ T-cell escape mutations, since determining which escape mutations might corner the virus by imposing an uncompensated fitness cost is a desirable goal for future vaccine strategies.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grants AI-46995 [P.J.R.G.] and AI-64060 [E.H]), the Wellcome Trust (P.J.R.G.), The Mark and Lisa Schwartz Foundation (P.J.R.G.), and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (S.A. and E. H.).

P. J. R. Goulder is an Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation Scientist, E. Hunter is a Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar, and T. Ndung'u holds the South African Research Chair in Systems Biology of HIV/AIDS.

We thank the patients and staff in Durban, South Africa, and at the Zambia-Emory HIV Research Project, who made the collection of blood samples for this study possible, and Jian Peng for help with structure prediction.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barouch, D. H., et al. 2002. Eventual AIDS vaccine failure in a rhesus monkey by viral escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature 415:335-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bickel, P. J., et al. 1996. Covariability of V3 loop amino acids. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 12:1401-1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borrow, P., H. Lewicki, B. H. Hahn, G. M. Shaw, and M. B. Oldstone. 1994. Virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity associated with control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 68:6103-6110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boutwell, C. L., C. F. Rowley, and M. Essex. 2009. Reduced viral replication capacity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C caused by cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte escape mutations in HLA-B57 epitopes of capsid protein. J. Virol. 83:2460-2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brockman, M. A., et al. 2007. Escape and compensation from early HLA-B57-mediated cytotoxic T-lymphocyte pressure on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag alter capsid interactions with cyclophilin A. J. Virol. 81:12608-12618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brockman, M. A., G. O. Tanzi, B. D. Walker, and T. M. Allen. 2006. Use of a novel GFP reporter cell line to examine replication capacity of CXCR4- and CCR5-tropic HIV-1 by flow cytometry. J. Virol. Methods 131:134-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bunce, M., et al. 1995. Phototyping: comprehensive DNA typing for HLA-A, B, C, DRB1, DRB3, DRB4, DRB5 & DQB1 by PCR with 144 primer mixes utilizing sequence-specific primers (PCR-SSP). Tissue Antigens 46:355-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson, J. M., et al. 2008. Phylogenetic dependency networks: inferring patterns of CTL escape and codon covariation in HIV-1 Gag. PLoS Comput. Biol. 4:e1000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crawford, H., et al. 2009. Evolution of HLA-B*5703 HIV-1 escape mutations in HLA-B*5703-positive individuals and their transmission recipients. J. Exp. Med. 206:909-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford, H., et al. 2007. Compensatory mutation partially restores fitness and delays reversion of escape mutation within the immunodominant HLA-B*5703-restricted Gag epitope in chronic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 81:8346-8351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feeney, M. E., et al. 2004. Immune escape precedes breakthrough human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viremia and broadening of the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response in an HLA-B27-positive long-term-nonprogressing child. J. Virol. 78:8927-8930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gamble, T. R., et al. 1996. Crystal structure of human cyclophilin A bound to the amino-terminal domain of HIV-1 capsid. Cell 87:1285-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gatanaga, H., et al. 2006. Altered HIV-1 Gag protein interactions with cyclophilin A (CypA) on the acquisition of H219Q and H219P substitutions in the CypA binding loop. J. Biol. Chem. 281:1241-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gatanaga, H., et al. 2002. Amino acid substitutions in Gag protein at non-cleavage sites are indispensable for the development of a high multitude of HIV-1 resistance against protease inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 277:5952-5961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilbert, P. B., V. Novitsky, and M. Essex. 2005. Covariability of selected amino acid positions for HIV type 1 subtypes C and B. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 21:1016-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goulder, P., et al. 1997. Co-evolution of human immunodeficiency virus and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses. Immunol. Rev. 159:17-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatziioannou, T., S. Cowan, U. K. Von Schwedler, W. I. Sundquist, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2004. Species-specific tropism determinants in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid. J. Virol. 78:6005-6012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honeyborne, I., et al. 2007. Control of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is associated with HLA-B*13 and targeting of multiple gag-specific CD8+ T-cell epitopes. J. Virol. 81:3667-3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiepiela, P., et al. 2004. Dominant influence of HLA-B in mediating the potential co-evolution of HIV and HLA. Nature 432:769-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiepiela, P., et al. 2007. CD8+ T-cell responses to different HIV proteins have discordant associations with viral load. Nat. Med. 13:46-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koup, R. A., et al. 1994. Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. J. Virol. 68:4650-4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leslie, A. J., et al. 2004. HIV evolution: CTL escape mutation and reversion after transmission. Nat. Med. 10:282-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, S., C. P. Hill, W. I. Sundquist, and J. T. Finch. 2000. Image reconstructions of helical assemblies of the HIV-1 CA protein. Nature 407:409-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez-Picado, J., et al. 2006. Fitness cost of escape mutations in p24 Gag in association with control of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 80:3617-3623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthews, P. C., et al. 2008. Central role of reverting mutations in HLA associations with human immunodeficiency virus set point. J. Virol. 82:8548-8559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poon, A., and L. Chao. 2005. The rate of compensatory mutation in the DNA bacteriophage phiX174. Genetics 170:989-999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pornillos, O., et al. 2009. X-ray structures of the hexameric building block of the HIV capsid. Cell 137:1282-1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rolland, M., et al. 2010. Amino-acid co-variation in HIV-1 Gag subtype C: HLA-mediated selection pressure and compensatory dynamics. PLoS One 5:e12463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmitz, J. E., et al. 1999. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science 283:857-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneidewind, A., et al. 2008. Structural and functional constraints limit options for cytotoxic T-lymphocyte escape in the immunodominant HLA-B27-restricted epitope in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid. J. Virol. 82:5594-5605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneidewind, A., et al. 2007. Escape from the dominant HLA-B27-restricted cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response in Gag is associated with a dramatic reduction in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J. Virol. 81:12382-12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneidewind, A., et al. 2009. Maternal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus escape mutations subverts HLA-B57 immunodominance but facilitates viral control in the haploidentical infant. J. Virol. 83:8616-8627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang, C., Y. Ndassa, and M. F. Summers. 2002. Structure of the N-terminal 283-residue fragment of the immature HIV-1 Gag polyprotein. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:537-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang, J., et al. 2008. Human leukocyte antigen class I genotypes in relation to heterosexual HIV type 1 transmission within discordant couples. J. Immunol. 181:2626-2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang, Y., et al. 2010. Correlates of spontaneous viral control among long-term survivors of perinatal HIV-1 infection expressing human leukocyte antigen-B57. AIDS 24:1425-1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright, J. K., et al. 2010. Gag-protease-mediated replication capacity in HIV-1 subtype C chronic infection: associations with HLA type and clinical parameters. J. Virol. 84:10820-10831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu, T., X. Zou, S. Y. Huang, and X. W. Zou. 2009. Cutoff variation induces different topological properties: a new discovery of amino acid network within protein. J. Theor. Biol. 256:408-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]