Abstract

Members of the Geminiviridae have single-stranded DNA genomes that replicate in nuclei of infected plant cells. All geminiviruses encode a conserved protein (Rep) that catalyzes initiation of rolling-circle replication. Earlier studies showed that three conserved motifs—motifs I, II, and III—in the N termini of geminivirus Rep proteins are essential for function. In this study, we identified a fourth sequence, designated GRS (geminivirus Rep sequence), in the Rep N terminus that displays high amino acid sequence conservation across all geminivirus genera. Using the Rep protein of Tomato golden mosaic virus (TGMV AL1), we show that GRS mutants are not infectious in plants and do not support viral genome replication in tobacco protoplasts. GRS mutants are competent for protein-protein interactions and for both double- and single-stranded DNA binding, indicating that the mutations did not impair its global conformation. In contrast, GRS mutants are unable to specifically cleave single-stranded DNA, which is required to initiate rolling-circle replication. Interestingly, the Rep proteins of phytoplasmal and algal plasmids also contain GRS-related sequences. Modeling of the TGMV AL1 N terminus suggested that GRS mutations alter the relative positioning of motif II, which coordinates metal ions, and motif III, which contains the tyrosine involved in DNA cleavage. Together, these results established that the GRS is a conserved, essential motif characteristic of an ancient lineage of rolling-circle initiators and support the idea that geminiviruses may have evolved from plasmids associated with phytoplasma or algae.

Geminiviruses are plant viruses with small, circular DNA genomes and twin icosahedral capsids (58). They constitute a large family that is divided into the begomovirus, mastrevirus, curtovirus, and topocuvirus genera based on genome arrangement, insect vector, and host range (68). Geminiviruses amplify their single-stranded (ss) genomes in the nuclei of infected cells using a combination of rolling-circle and recombination-mediated replication (reviewed in references 27, 31, and 35). All geminiviruses encode a conserved protein designated Rep (also known as AL1, AC1, C1, L1, or C1:C2), which mediates initiation of viral replication but does not act as a DNA polymerase (33, 42, 51). Instead, geminiviruses depend on host replication machinery to copy their genomes (28, 31, 32).

Rep is the only geminivirus protein that is essential for viral replication (18, 56). It is a multifunctional protein that mediates virus-specific recognition of its cognate origin (22) and transcriptional repression (17, 69). Rep initiates and terminates viral DNA synthesis (33, 42, 51) and induces the accumulation of host replication factors in infected cells (48). Rep binds specifically to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) at a repeated sequence in the 5′ intergenic region of the viral genome (22, 67), cleaves and ligates DNA within an invariant sequence in a hairpin loop of the plus-strand origin (42, 51), and acts as a DNA helicase to unwind viral DNA during plus-strand replication (12, 16, 67).

Rep is involved in a variety of protein interactions. The formation of Rep homo-oligomers is required for its dsDNA binding and DNA helicase activities (11, 52, 53). Rep activity may also be modulated by interaction with AL3 (62, 63), which is required for high levels of viral DNA accumulation (18), and with coat protein, which downregulates DNA cleavage and ligation activity in vitro (47). Rep binds to several host factors involved in DNA transactions, including the replicative clamp PCNA (5, 9), the clamp loader RFC (46), the ssDNA binding protein RPA (66), histone H3, and a mitotic kinesin (38). It interacts with host regulatory factors, including the retinoblastoma protein (RBR), which modulates the plant cell cycle and differentiation (1, 26, 76), GRIK - a protein kinase that may link the cell cycle to metabolic processes (38, 64, 65), and Ubc9—a component of the sumoylation pathway (10).

The N terminus of Rep contains three conserved sequences called motifs I, II, and III that are characteristic of many rolling-circle initiators (34, 40). Motif I (FLTY) is required for specific dsDNA binding while motif II (HLH) is a metal-binding site that may be involved in protein conformation and DNA cleavage (2, 27, 52). Motif III (YxxKD/E) is the catalytic site for DNA cleavage, with the hydroxyl group of the Y residue forming a covalent bond with the 5′ phosphoryl group of the cleaved DNA strand (42, 51). In the present study, an amino acid sequence alignment of geminivirus Rep proteins uncovered an uncharacterized sequence between motifs II and III that displays high conservation across the Geminiviridae. We investigated the function of this conserved motif (named the GRS for geminivirus Rep sequence) using the bipartite begomovirus Tomato golden mosaic virus (TGMV) (30). Our analysis builds on an extensive knowledge of the TGMV Rep protein (22, 25, 50-53), which is designated AL1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Amino acid sequence alignments and sequence logo representations.

The Invitrogen Vector NTI AlignX module (45) was used for amino acid alignment of Rep proteins. The geminivirus alignments included a Rep sequence from a single isolate for each defined viral species and are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material (21). The geminiviruses with less than 70% identity considered in Fig. S1B in the supplemental material are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. WebLogo was used to generate sequence logos, with columns of amino acids for each position in the sequence. The column height signifies conservation of the sequence at that position, while the height of the amino acids within the column shows relative frequency (13, 61).

Mutagenesis and plasmid construction.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using a QuikChange II kit (Stratagene). Plasmid pNSB148, which contains the wild-type TGMV AL1 coding sequence in a pUC118 background, was used as the template for mutagenesis (52). The oligonucleotides used for mutagenesis and the mutagenesis clones are listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material. The replicon vector, plant expression cassette, yeast two hybrid vectors and Escherichia coli expression cassette for each AL1 mutant are also listed in Table S3. The mutations and flanking sequences used for subcloning were verified by DNA sequencing.

To construct mutant replicon vectors carrying partial tandem copies of TGMV A, a 1.2-kb HindIII/EcoRI fragment from pMON434 (69) was cloned into Bluescript II KS. The mutagenesis clones were digested with BglII and EcoRI to release 364-bp fragments carrying the AL1 mutations, which were subcloned into the altered Bluescript plasmid. To generate the final replicon vectors, a 2.2-kb MunI/EcoRI fragment from pMON424 (18) was subcloned into each of the EcoRI-digested intermediate plasmids. Plant expression cassettes carrying the mutant TGMV AL1 coding sequences were made by subcloning 1.2-kb BglII/BamHI fragments from the mutagenesis clones into pMON921 (22) digested with BglII.

The yeast two-hybrid vector pNSB736 contains a fusion of the full-length, wild-type TGMV AL1 and the Gal4 DNA-binding domain (DBD) (53). The mutant AL1-DBD fusions were created by digesting the mutagenesis clones with NdeI and EcoRI and subcloning the resulting 348-bp fragments into NdeI/EcoRI-digested pNSB736. Wild-type (pNSB1814) and mutant AL1-activation domain (AD) fusions were created by digesting mutagenesis plasmids with NdeI and BamHI and subcloning the resulting 1.2-kb fragments into pGADT7 (Clontech) cut with same enzymes.

To generate E. coli expression cassettes corresponding to wild-type and mutant AL11-180 proteins, the full-length AL1 coding sequence from pMON1549 (22) was cloned into pET16b (Novagen) to give pNSB297 (53). An 889-bp SalI/XbaI fragment was isolated from a pMON1549 variant with a stop codon after AL1 amino acid 180 and subcloned into pNSB297 digested with SalI and XbaI. The resulting clone, pNSB895, encodes wild-type TGMV AL1 amino acids 1 to 180 fused to an N-terminal His10 tag. E. coli expression cassettes for mutant AL11-180 proteins were made by cloning 348-bp NdeI/EcoRI fragments from the mutagenesis clones into NdeI/EcoRI-digested pNSB895.

Infection assays.

Nicotiana benthamiana plants with six to eight leaves were infected by bombardment. Wild-type or mutant TGMV A replicon DNA (10 μg) and wild-type TGMV B replicon DNA (10 μg) were precipitated onto a 1-μm gold microprojectile (60) and used to inoculate six plants. The wild-type TGMV A and B plasmids used were pMON1565 (51) and pTG1.4B, respectively (23). Viral DNA inoculation was performed with a microsprayer (Venganza, Inc.) at 25 lb/in2 using Swinnex filters (Millipore). Three independent experiments were performed with at least six plants per treatment. Symptoms were monitored daily for signs of infection. Young leaf tissue was collected at 18 dpi from five plants from each treatment. The total DNA was isolated (15), digested with DpnI, and amplified for 25 cycles (57) using the oligonucleotides TGTGTTGAGCTTTGATAGAGGGGGGAGTTG and ACGGTTTCAAATAAATGCCAAAAATTATTTTCTTACATATCCTCA, which generate a 1.0-kb region of TGMV A. PCR products were resolved on 1% agarose Tris-acetate-EDTA gels.

Transient replication assays.

Protoplasts were isolated from Nicotiana tabacum NT-1 suspension cells, electroporated, and cultured as described previously (22). For replication assays, the transfections contained 5 μg of a TGMV B replicon (pTG1.4B [23]), 10 μg of a wild-type (pMON1549) or mutant TGMV AL1 expression cassette, and 10 μg of a TGMV AL3 plant expression cassette (pNSB46 [22]). For the interference assays, 2 μg of a wild-type TGMV A replicon (pMON1565 [51]) was cotransfected with 40 μg of a mutant AL1 expression cassette or the empty expression vector (pMON921 [22]). For both replication and interference assays, total DNA was extracted 48 h after transfection. Total DNA (40 μg) was digested with DpnI and linearized with BglII or BamHI for replication and interference assays, respectively. Nascent viral DNA accumulation was analyzed by DNA gel blotting. Replication and interference blots were probed with a 32P-labeled DNA corresponding to TGMV B and TGMV A, respectively.

Yeast two-hybrid assays.

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain Y190 (Clontech, genotype MATa gal4-542 gal80-538 his3 trp1-901 ade2-101 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 URA3::GAL1-LacZ Lys2::GAL1-HIS3cyhr) was cotransformed with bait and prey plasmids using a lithium acetate-polyethylene glycol protocol (Clontech Yeast Protocols Manual PT3024-1). Transformants were plated on synthetic dropout medium lacking leucine and tryptophan (−LW). Freshly patched yeast cells were used to inoculate 1.2 ml of liquid medium (−LW) and grown overnight at 30°C with shaking at 250 rpm. The cells were pelleted at 1,000 × g for 5 min, rinsed with Z buffer (0.1 M NaPO4 [pH 7], 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4), and resuspended in 300 μl of Z buffer. A 10-μl aliquot was diluted into 90 μl of water, and the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured by using a 96-well Bio-Rad microplate Reader 680. The remaining cells were subjected to five freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen. The cell lysate (150 μl) was added to 50 μl of Z-buffer containing 40 mM β-mercaptoethanol. For the β-galactosidase enzyme assays (adapted from Clontech protocols), 50 μl of the substrate ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside; 4 mg/ml in Z buffer) was added to start the reaction. The reactions were stopped by the addition of 20 μl of 1 M Na2CO3 as the yellow color developed. The cells were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 2 min, and the accumulation of the o-nitrophenol product was measured at A420 by using the microplate reader. One unit of β-galactosidase specific activity was defined as the amount that hydrolyzes 1 μM ONPG to o-nitrophenol and D-galactose per min per cell. β-Galactosidase units were calculated as follows: 1,000 × OD420/(t × V × OD600), where t is elapsed time (in minutes) of incubation, V = 0.1 ml × the concentration factor, and OD600 = the A600 for 10 μl of culture × the dilution factor. The β-galactosidase specific activity for wild-type and mutant AL1 proteins was adjusted for background from bait plasmids alone. The different constructs were tested in a minimum of three experiments, each of which assayed three independent transformants per construct.

For immunoblot analysis of bait protein expression, yeast transformants were grown overnight in 5 ml of synthetic dropout medium lacking tryptophan. The cells were pelleted at 1,000 × g for 5 min, resuspended in 1 volume of yeast cracking buffer (8 M urea, 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.4 mg of bromophenol blue/ml), subjected to five freeze-thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen, and sonicated. The sample was then centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 2 min at 4°C. The supernatant was recovered, and the protein concentration was determined by using Bradford assays. Total protein (100 μg) was resolved on a 12% polyacrylamide-SDS gel and analyzed by immunoblotting with a GAL4 DBD polyclonal antibody (Clontech) at 0.4 μg/ml.

Recombinant protein expression and purification.

Wild-type and mutant versions of His10-tagged AL11-180 were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells after induction by 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 16 h at 16°C. The cells were broken by lysozyme digestion (100 μg/ml) and sonication. Recombinant AL11-180 was partially purified by using a GE His-Trap FF column with a GE Pharmacia Akta Purifier 10. Column wash buffer contained 20 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2 (pH 6.8), and elution buffer contained 20 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 1 M imidazole (pH 6.8). After elution, the proteins were dialyzed to exchange into wash buffer supplemented with 20% glycerol for protein binding and cleavage assays. Total protein concentrations were measured by Bradford assays. Protein purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie brilliant blue staining.

DNA binding and cleavage assays.

LI-COR 5′ IRDye 700 oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. For the oligonucleotides used in in vitro assays, see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material. For dsDNA binding assays, complementary oligonucleotides were incubated at equal molar concentrations for 5 min at 100°C and allowed to cool slowly to room temperature. For ssDNA binding assays and DNA cleavage assays, individual oligonucleotides were heated 5 min at 100°C and immediately placed on ice. For dsDNA and ssDNA binding assays, wild-type and mutant AL11-180 proteins (2.5 μg) were resuspended in binding buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 2.5 mM ATP), 100 ng of poly(dI-dC), and 20 fmol of fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide plus increasing amounts of unlabeled competitor oligonucleotide, as indicated in the figure legends. The binding reactions were incubated for 30 min at room temperature and resolved on a 0.5% Tris-borate-EDTA (pH 8.5) agarose gel and visualized by using an Odyssey infrared imaging system.

For DNA cleavage assays, wild-type and mutant AL11-180 proteins (2.5 μg) were resuspended in cleavage buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM DTT), and 50 fmol of wild-type or mutant oligonucleotide was added. Cleavage reactions were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, 15 μl of sequencing stop buffer (80% [wt/vol] deionized formamide, 10 mM EDTA [pH 8], 0.05% Orange G) was added, and the samples were boiled for 2 min. The reactions were resolved on a 15% polyacrylamide sequencing gel and visualized by using an Odyssey infrared imaging system.

Protein modeling.

Wild-type TGMV AL17-121 was modeled based on the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structure for amino acids 4 to 121 of TYLCSV Rep (PID 1L2M) (8). SWISS-MODEL was used to create the original pdb file based on alignment of TGMV AL1 to TYLCSV Rep (3, 36, 55). PyMOL (14) was used for structural analysis and to create figures. Hydrophobic cavity calculations were performed by using Voronia (59) and visualized as a red mesh ball in PyMOL. For the dsDNA-protein model, the TGMV AL1 model was superimposed onto protein chains A and B of simian virus 40 (SV40) T-antigen bound to palindromic dsDNA (pdb code 2ITL) using LSQMAN (37). The TGMV AL17-121 model superimposed with a Cα root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 2.13 Å for 63 matching residues of chain A and a Cα RMSD of 1.95 Å to chain B. The resulting model of TGMV AL1 bound to dsDNA was further modified in CNS (Crystallography and NMR Systems) (6, 7). Hydrogens were added, and the model was annealed using torsion molecular dynamics at a constant temperature of 298 for 1,000 time steps of 0.005 ps. The final coordinate file from model annealing was energy minimized for 1 cycle of 200 steps. During both annealing and energy minimization, the DNA coordinates remained fixed and only the protein was allowed to be flexible. The final energy minimized model had an average bond RMSD of 0.4 Å and an average angle RMSD of 2.0. Chain A of the final energy minimized model superimposed with a Cα RMSD of 2.34 Å to protein chain A of 2ITL and still superimposed well to the starting model, with a Cα RMSD of 1.26 Å.

RESULTS

A novel motif in geminivirus Rep proteins.

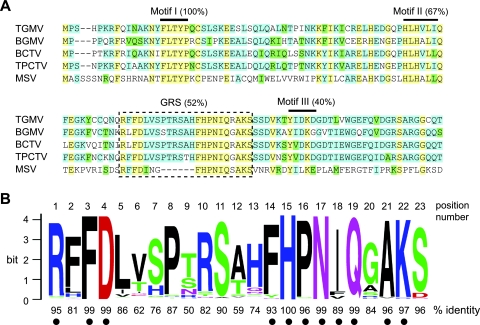

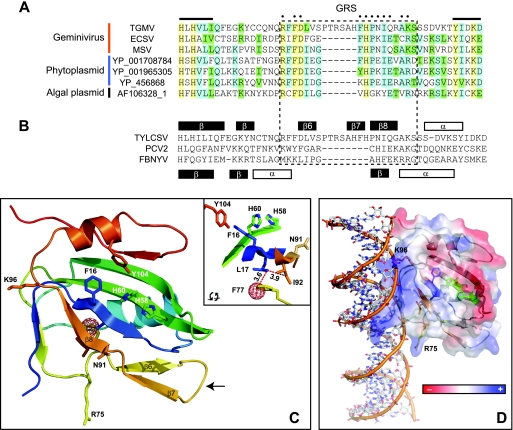

The amino acid sequences of the Rep proteins corresponding to the type members of the four geminivirus genera show 86% similarity and 23% identity (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). The N-terminal DNA binding/cleavage domain displays the highest level of conservation between the four type members (92% similarity and 29% identity). Part of this high conservation is due to the presence of three well-characterized motifs, I, II, and III, that are typical of many rolling-circle initiators, such as the geminivirus Rep proteins (34, 40). Motifs I (5 amino acids), II (6 amino acids), and III (5 amino acids) display amino acid residue conservation in 100, 67, and 40% of the positions, respectively (Fig. 1A). An alignment between TGMV AL1 and the Rep proteins from the type members of the four geminivirus genera uncovered a uncharacterized, conserved sequence in the N terminus that we have designated the GRS (geminivirus Rep sequence) (Fig. 1A). The GRS is 52% identical between the type members and contains six consecutive identical amino acids representing the longest stretch of identity in the Rep N terminus.

FIG. 1.

Novel amino acid motif in the N termini of geminivirus replication proteins. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment shows the novel motif (designated GRS; dotted box) in the N termini of TGMV AL1 and Rep proteins of the type members of the begomovirus (Bean golden mosaic virus [BGMV]), curtovirus (Beet curly top virus [BCTV]), topocuvirus (Tomato pseudo-curly top virus [TPCTV]), and mastrevirus (Maize streak virus [MSV]) genera. Motifs I, II, and III, which are conserved among RCR initiator proteins (40), are marked by lines. The levels of identity for motif I (100%), motif II (67%), motif III (40%), and GRS (52%) are shown. Protein alignment was performed by using Vector NTI AlignX, and the color scheme represents amino acid identity (yellow), conservation (blue), and blocks of similarity (green) (45). (B) Amino acid sequence logo (13, 61) shows the conservation of the GRS motif across 198 geminivirus species (based on reference 21). The percent identity indicated below the sequence logo is based on the consensus amino acid at that position. Dots indicate residues in which the consensus sequence is shared among all genera. Amino acids are color coded according to their type as basic (blue), hydrophobic (black), polar/nonpolar (green), amide (purple), and acidic (red) (13, 61).

To determine the extent of identity of the GRS, we compared Rep protein sequences of 198 geminivirus species (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). We used phylogenetic information (21) to exclude multiple isolates of viral species from the analysis. The Rep sequences were aligned globally with the Vector NTI AlignX module (Invitrogen), and the sequence logo representations of the GRS alignments were performed using WebLogo (13, 61). The GRS sequence logo for all 198 Rep proteins (Fig. 1B) shows an average identity score of 86%. (The amino acids and their frequencies at each GRS position are listed in Table S4 in the supplemental material.) Eleven of the twenty-three residues display ≥89% identity and correspond to the consensus amino acids across the genera (indicated by dots in Fig. 1B). The strongest conservation is at the ends of the GRS, raising the possibility that the sequence encompasses two functionally distinct motifs.

The sequence logo in Fig. 1B is most representative of begomovirus Rep proteins, which constituted 178 of the 198 sequences, and may not accurately reflect the under-represented genera. To address this possibility, we compared the GRSs of 19 geminiviruses Rep proteins (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material) previously identified as <70% identical to each other and representing 10 begomoviruses, 2 curtoviruses, and 7 mastreviruses (41). The sequence logo shows the GRS remains a prominent conserved element even among diverse geminivirus Rep proteins. The 11 consensus amino acids throughout the GRS remain the same showing ≥74% identity in most positions and, interestingly, ≥95% identity at FD at positions 3 and 4, H at position 15, N at position 17, Q at position 19, and AK at positions 21-22.

We also compared the GRS within genus (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material). For this analysis, the begomovirus genus was separated into three groups representing 46 New World viruses, 120 Old World viruses, and 12 members of the Squash leaf curl (SLC) clade. We also compared Rep sequences for 5 curtoviruses and 12 mastreviruses. Several residues are highly conserved across the five sequence logos, most notably FD at positions 3 and 4, H at position 15, N at position 17, Q at position 19, and AK at positions 21 and 22. Each of these amino acids displays 96 to 100% identity in the overall sequence logo in Fig. 1B and is included among the conserved residues identified in the comparison of the diverse set of geminivirus Rep proteins (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). There are also some residues that are conserved within a specific group or genus. For example, Rep proteins in the SLC clade have A at position 20 and D at position 23, whereas G and S are at these positions, respectively, for other begomovirus Rep proteins. Similarly, R at position 1 and F at position 14 are strongly conserved in begomovirus and curtovirus, but not in mastrevirus Rep proteins. Mastrevirus Rep proteins also lack six residues in the middle of the GRS, further supporting the possibility that it contains two motifs.

The GRS is required for infection and viral genome replication.

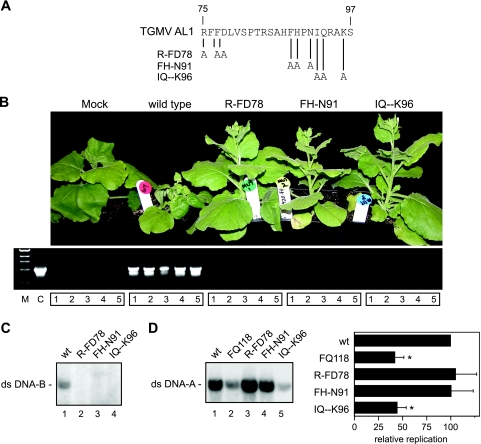

Mutagenesis studies have established that motifs I, II, and III are essential for rolling-circle replication (42, 54), but there is no functional information about the GRS. We used the well-characterized TGMV AL1 protein to investigate the impact the GRS has on Rep function (53, 54). We selected nine GRS residues with the highest level of identity (>89%) and represented in the overall consensus sequence (Fig. 1B) for site-directed mutagenesis. The GRS mutations were clustered in sets of three to facilitate separation of potential motifs within the GRS and to access protein-protein and DNA-protein interactions, which typically involve multiple residues (9, 28, 38, 39). The three GRS mutants, R-FD78, FH-N91, and IQ--K96, are alanine substitution mutants (Fig. 2A). They are named according to corresponding wild-type amino acid sequence and the position of the last modified residue in the AL1 protein (dashes indicate amino acids that were not changed). The P at position 16 and A at position 21 in the overall sequence logo (Fig. 1B) were not selected for mutagenesis because they were already alanine or are likely to be required for maintenance of protein secondary structure (29).

FIG. 2.

The GRS is required for TGMV infection and replication. (A) The positions of the alanine substitutions between TGMV AL1 amino acids 75 to 97 are indicated for mutants R-FD78, FH-N91, and IQ--K96. (B) N. benthamiana plants inoculated with a wild-type or mutant TGMV A replicon and a wild-type TGMV B replicon are shown. Total DNA from 5 plants of mock-, wild-type-, R-FD78-, FH-N91-, and IQ--K96-inoculated plants were analyzed for the presence of TGMV DNA-A by PCR (lanes 1 to 5 for each replicon). Lane C shows a control amplification with a wild-type TGMV A plasmid template. Lane M shows DNA size markers. (C) For transient replication assays, tobacco protoplasts were cotransfected with a wild-type TGMV B replicon and with plant expression cassettes encoding TGMV AL3 and wild-type AL1 (lane 1) or the mutants, R-FD78 (lane 2), FH-N91 (lane 3), or IQ--K96 (lane 4). Total DNA was isolated 48 h posttransfection and analyzed on DNA gel blots using a radiolabeled TGMV B probe. (D) For replication interference assays, tobacco protoplasts were cotransfected with a wild-type TGMV A replicon and with plant expression cassettes for R-FD78 (lane 3), FH-N91 (lane 4), or IQ--K96 (lane 5). The wild-type sample (lane 1) included an empty expression cassette. The AL1 mutant FQ118 (lane 2) was used as a positive control for interference (53). The graph shows the accumulation of TGMV A-DNA in the presence of the AL1 mutants relative to the empty cassette (wt, 100%). The error bars correspond to two standard errors. The asterisks indicate samples that are statistically different from wild-type (P < 0.05).

We first analyzed the impact of the GRS mutations on TGMV infection. N. benthamiana plants were inoculated by cobombardment of wild-type or mutant TGMV A and wild-type TGMV B replicons containing partial tandem copies of the viral genome components (Fig. 2B). Plants bombarded with wild-type TGMV A and B showed chlorosis, leaf curling, and stunting symptoms typical of TGMV infection at 18 days postinoculation (dpi). In contrast, plants inoculated with the three GRS mutant viruses did not develop symptoms and, instead, resembled mock-inoculated plants at 18 through 60 dpi. This experiment was repeated three times, with a total of 26 plants, with the same result. We also performed PCR of total DNA extracted from plants inoculated with wild-type and mutant viral replicons at 18 dpi. This analysis confirmed the presence of TGMV DNA-A in plants inoculated with wild-type virus, but no viral DNA was detected in the plants bombarded with the GRS mutant replicons (Fig. 2B). The lack of symptoms and absence of detectable viral DNA established that the GRS mutants are unable to support viral infection.

We then sought to determine whether the inability of the GRS mutants to infect plants was due to a defect in viral replication. Tobacco protoplasts were cotransfected with a TGMV B replicon plasmid, an AL3 plant expression cassette, and plant expression cassettes for wild-type AL1 or the GRS mutants. Total DNA was isolated at 48 h posttransfection and analyzed on DNA gel blots for the accumulation of TGMV B dsDNA (Fig. 2C). TGMV B replication was detected in tobacco cells expressing wild-type TGMV AL1 (Fig. 2C, lane 1) but not in cells expressing the three GRS mutants (Fig. 2C, lanes 2 to 4), indicating that the mutants do not support viral genome replication.

Previous studies showed that some TGMV AL1 mutants interfere with the capacity of wild-type AL1 to support viral replication in tobacco cells (53, 54). We wanted to determine whether the GRS mutants interfere with viral DNA replication in tobacco protoplasts transfected with a TGMV A replicon carrying wild-type AL1 sequences and a 20-fold excess of an empty or mutant AL1 expression cassette (Fig. 2D). The previously described FQ118 transdominant-negative mutant (53) was used as a positive control for replication interference. The accumulation of TGMV A dsDNA in total DNA extracts was examined 48 h after transfection on DNA gel blots (Fig. 2D, left) and quantified by phosphorimage analysis (Fig. 2D, right). The IQ--K96 mutant (Fig. 2D, lane 5) and FQ118 (lane2) control reduced viral genome replication similarly to ca. 50% of wild-type levels. In contrast, no reduction in TGMV A dsDNA levels was seen in the presence of the R-FD78 (Fig. 2D lane 3) and FH-N91 (lane 4) mutants, indicating that they do not interfere with viral replication.

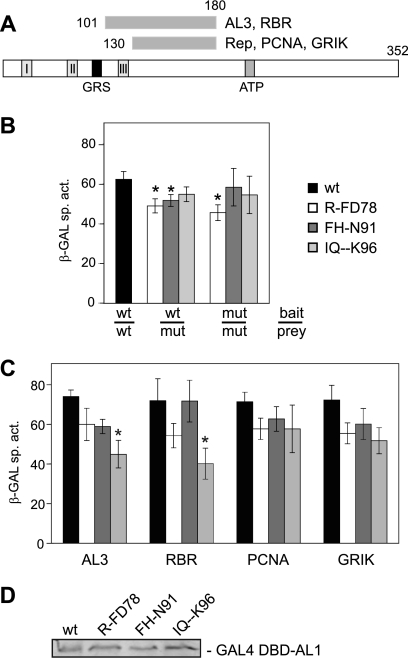

Protein-protein interactions.

AL1 oligomerization and interactions with plant proteins are necessary for TGMV replication and interference activities (9, 38, 39, 62). Thus, we examined the capacities of the GRS mutants to self-interact and to interact with selected host partners (Fig. 3A) by using a semiquantitative yeast two-hybrid assay. For AL1 oligomerization assays (Fig. 3B), a wild-type AL1 bait plasmid (a GAL4 DBD fusion) yeast was cotransformed with prey cassettes for wild-type or mutant AL1 (GAL4 AD fusions). Activation of a GAL4-responsive promoter driving a lacZ reporter was assayed by measuring β-galactosidase activity in total protein extracts. All three GRS mutants displayed ≥75% of wild-type oligomerization activity (Fig. 3B), but the activities of RF-D78 and FH-N91 mutants were statistically different from the wild type (P < 0.05). The weaker oligomerization activities of the RF-D78 and FH-N91 mutants are consistent with their lack of interference activity in protoplast assays (Fig. 2D), which depends on efficient AL1-AL1 interactions. We also examined the abilities of the GRS mutants to interact with themselves in yeast cotransformed with mutant AL1 bait and prey cassettes. In these assays, the RF-D78 mutant displayed reduced oligomerization activity, while FH-N91 and IQ--K96 were not statistically different from wild-type AL1 (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

AL1 GRS mutants oligomerize and interact with other viral and host proteins. (A) Schematic of AL1 protein interactions (9, 38, 39, 62). (B) For AL1 oligomerization assays, yeast was cotransformed with a wild-type or mutant AL1 expression cassette fused to the GAL4 DBD wild-type (wt) or a mutant AL1 expression cassette fused to the GAL4 AD. Protein interactions were assayed by measuring β-galactosidase activity in soluble protein extracts. The error bars correspond to two standard errors. The asterisks indicate samples that are statistically different from the wild type (P < 0.05). (C) For AL1-protein interaction assays, yeast was cotransformed with a wild-type or mutant AL1 expression cassette fused to the GAL4 DBD and with AL3, RBR, PCNA, or GRIK expression cassettes fused to the GAL4 AD. Protein interactions were assayed as described in panel B. (D) Total proteins were extracted from yeast transformed with GAL4 DBD fusions corresponding to wild-type (lane 1), R-FD78 (lane 2), FH-N91 (lane 3), and IQ--K96 (lane 4) AL1. The extracts (100 μg) were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-GAL4 DBD antibody.

Yeast cells were also cotransformed with bait cassettes for wild-type or mutant AL1 and prey cassettes for AL3, RBR, PCNA, or GRIK (Fig. 3C). The interactions of R-FD78 and FH-N91 with AL3, RBR, PCNA, and GRIK did not differ significantly from wild-type AL1. Mutant IQ--K96 displayed reduced AL3 and RBR binding activity relative to wild-type AL1, but there was no difference for PCNA and GRIK. The lower AL3 and RBR binding activities may reflect the proximity of the IQ--K96 mutation to their binding regions, which have been mapped between AL1 amino acids 101 and 180 and shown to require sequences between 101 and 120. (Fig. 3A) (1, 39, 62). In contrast, PCNA and GRIK bind between AL1 amino acids 134 and 180 (9, 38), a finding consistent with no effect of the IQ--K96 mutation on the interactions.

To verify that the observed differences in protein interactions were not due to variable protein production in yeast, we isolated total protein extracts from transformants and examined the levels of the AL1 bait proteins on immunoblots probed with a polyclonal antibody against the GAL4 DBD (Fig. 3D). This analysis confirmed that wild-type AL1 and the GRS mutant bait proteins accumulated to similar levels. A similar analysis of prey proteins was not possible because wild-type and mutant AL1-AD fusions could not be detected on immunoblots. However, it is unlikely that the small reductions in protein interactions detected for the GRS mutants are responsible for their total loss of viral genome replication activity.

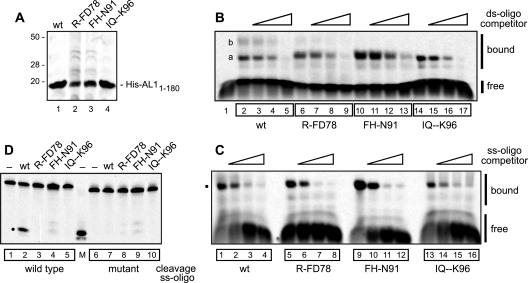

GRS mutants bind to dsDNA.

TGMV AL1 binds to dsDNA in a sequence-specific manner (24). This activity, which is essential for viral replication (22), is mediated by AL1 amino acids 1 to 180 encompassing the DNA binding and oligomerization domains (52, 54). We expressed His-tagged versions of wild-type TGMV AL11-181 and the GRS mutants in E. coli and partially purified the recombinant proteins by Ni2+ affinity chromatography. Figure 4A shows Coomassie brilliant blue staining of the enriched protein extracts resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gels.

FIG. 4.

The GRS is required for DNA cleavage but not for DNA binding. (A) His-tagged TGMV AL11-180 proteins were expressed in E. coli and partially purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography. Eluted proteins (2.5 μg) for wild-type AL1 (lane 1), R-FD78 (lane 2), FH-N91 (lane 3), and IQ--K96 (lane 4) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining. (B) The dsDNA binding activities of wild-type AL11-180 (lanes 2 to 5) and the mutants R-FD78 (lanes 6 to 9), FH-N91(lanes 10 to 13), and IQ--K96 (lanes 14 to 17) were analyzed in EMSAs using a fluorescent dsDNA oligonucleotide (23). Lane 1 is a no protein control. All reactions contained a 500-fold excess of an unlabeled mutant dsDNA oligonucleotide and increasing amounts (0, 10×, 100×, or 500×) of unlabeled wild-type dsDNA oligo. Specific AL1-dsDNA complexes are designated “a” and “b”. (C) The ssDNA binding activities of wild-type AL11-180 (lanes 1 to 4) and the mutants R-FD78(lanes 5 to 8), FH-N91(lanes 9 to 12), and IQ--K96 (lanes 13 to 16) were analyzed in EMSAs using a fluorescent ssDNA oligonucleotide and increasing amounts (0, 10×, 50×, or 100×) of an unlabeled ssDNA oligonucleotide competitor. An AL1-ssDNA complex is marked by the dot. (D) The DNA cleavage activities of wild-type AL11-180 (lanes 2 and 7) and the mutants R-FD78 (lanes 3 and 8), FH-N91(lanes 4 and 9), and IQ--K96 (lanes 5 and 10) were analyzed using a fluorescent ssDNA oligonucleotide. Lanes 1 to 5 contained a wild-type ssDNA oligonucleotide, whereas lanes 6 to 10 contained a mutant oligonucleotide modified at the cleavage site, which cannot be cleaved. Lanes 1 and 6 correspond to no protein controls, whereas lane M contains a fluorescent oligonucleotide marker for the cleavage product. The dot indicates the cleaved oligonucleotide product. The faint double bands observed in lanes 4 and 9 are due to contaminating nonspecific nuclease activity. The DNA oligonucleotides used in panels B, C, and D are shown in Fig. S2B in the supplemental material.

We used electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) containing oligonucleotides labeled with IRDye 700 infrared dye to examine the dsDNA binding activities of the recombinant His10-AL11-180 proteins. The assays included a wild-type dsDNA oligonucleotide (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material) corresponding to the AL1 binding site in the 5′-intergenic region of the TGMV genome (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material, red) (52). A mutant dsDNA oligonucleotide (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material) that does not bind AL1 served as a negative control and a nonspecific competitor (52). We first verified that the fluorescent label does not interfere with AL1 dsDNA binding. Two shifted complexes were detected for wild-type TGMV His10-AL11-180 (see Fig. S3A, lane 2, in the supplemental material). The faster-migrating complex (designated as “a”) was more abundant than the slower-migrating complex (designated as “b”). Both complexes were competed by the inclusion of increasing amounts of wild-type (lanes 3 to 5) but not mutant (lanes 6 to 8) dsDNA oligonucleotides, indicating that they are specific dsDNA complexes with AL1.

We then compared the dsDNA binding activities of wild-type AL1 and the three GRS mutants (Fig. 4B). The recombinant proteins were incubated with the fluorescent dsDNA oligonucleotide corresponding to the AL1 binding site and a 500-fold excess of the mutant dsDNA competitor and analyzed by an EMSA. Complex “a” was seen with wild-type His10-AL11-180 (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 to 5) and the three GRS mutants, while complex “b” was reduced for R-FD78 (Fig. 4B, lanes 6 to 9) and not detected for FH-N91 (lanes 10 to 13) and IQ--K96 (lanes 14 to 17). The competition patterns were similar for wild-type AL1 and the GRS mutants, indicating that the mutants are competent for dsDNA binding. Oligomerization is required for dsDNA binding (54), and the ability of all three GRS mutants to bind dsDNA supports the oligomerization results in Fig. 3B. However, complex “b” may be indicative of different multimeric forms of AL1 that are reduced for the GRS mutants.

GRS mutants bind nonspecifically to ssDNA.

The TGMV His10-AL11-181 proteins were also tested for binding to ssDNA using two fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides with different sequences but similar size (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material). The ssDNA oligonucleotide 1 corresponds to the hairpin (see Fig. S2A, blue, in the supplemental material) in the plus-strand replication origin that is cleaved by AL1 (51). The ssDNA oligonucleotide 2 is the top strand of the mutant dsDNA used as a negative control for dsDNA binding (Fig. S2B) and is not related to the DNA cleavage site. Wild-type His10-AL11-180 protein was incubated with fluorescently labeled ssDNA oligonucleotide 1 (Fig. S3B, lanes 1 to 4) or ssDNA oligonucleotide 2 (lanes 5 to 8) in the presence of increasing amounts of unlabeled ssDNA oligonucleotide 2. Shifted complexes were detected by EMSA for both oligonucleotides (lanes 1 and 5), and the complexes were competed by unlabeled oligonucleotide 2 (cf. lanes 2 to 4 and lanes 6 to 8), indicating that AL1 binds to ssDNA in a sequence-nonspecific manner. Our result contrasts with an earlier study (70) that concluded that AL1 binds preferentially to a ssDNA sequence corresponding to TGMV common region based on binding to larger probes containing the entire common region (CR in Fig. S2A in the supplemental material).

We then compared the ssDNA binding activities of wild-type and GRS mutant His10-AL11-180 proteins (Fig. 4C). The proteins were incubated with fluorescently labeled ssDNA oligonucleotide 2 and increasing amounts of unlabeled ssDNA oligonucleotide 2 as competitor. A shifted complex (Fig. 4C, dot) was observed for wild-type AL1 (lane 1) and the three GRS mutants (lanes 5, 9, and 13), which was competed similarly by increasing competitor for all four proteins (cf. lanes 2 to 4, lanes 6 to 8, lanes 10 to 12, and lanes 14 to 16). Together, these results indicated that the dsDNA and ssDNA binding activities are not altered significantly by the GRS mutations.

The GRS is required for ssDNA cleavage.

TGMV AL1 cleaves the viral genome at a specific site at the base of the loop in the hairpin (see Fig. S2A, blue, in the supplemental material) in the plus-strand origin (51). We compared the DNA cleavage activities of wild-type His10-AL11-180 and the GRS mutant proteins using a fluorescently labeled ssDNA oligonucleotide (see Fig. 2B in the supplemental material) corresponding to the loop and right stem sequences of the hairpin (Fig. S2B). Cleavage specificity was verified using a fluorescently labeled mutant oligonucleotide (Fig. S2B) that is not a substrate for AL1 endonuclease activity (51). In the presence of wild-type AL1, a cleavage product (Fig. 4D, dot) of the expected size (lane M) was detected in a reaction containing the wild-type oligonucleotide (lane 2) but not the mutant oligonucleotide (lane 7). In contrast, no cleavage products were seen for the GRS mutants with either the wild-type (lanes 3 to 5) or the mutant (lanes 8 to 10) oligonucleotide. This result provides a mechanistic basis for the failure of the GRS mutants to infect plants and support viral genome replication in cultured cells because cleavage of the plus-strand origin is essential for the initiation of rolling-circle replication (51).

The GRS is an ancient motif.

A novel geminivirus, Eragrostis curvula streak virus (ECSV), was isolated recently from wild grasses in Africa (72). ECSV, which is the most divergent geminivirus species described to date, contains a mixture of features distributed across the four geminivirus genera and may represent a new genus. Inspection of the ECSV Rep amino acid sequence between motifs II and III uncovered a sequence that conforms with the GRS consensus at 8 of 11 positions (Fig. 5A). Even though the ECSV Rep gene structure resembles that of begomo-, curto-, and topcoviruses, the GRS motif of the ECSV Rep protein is most similar to mastreviruses (cf. the MSV sequence). The presence of the GRS in ECSV Rep suggested that the motif was in a common ancestor of all members of the Geminiviridae.

FIG. 5.

(A) Alignment of TGMV AL1 amino acids 58 to 108, along with Rep proteins from Eragrostis curvula streak virus (ECSV), MSV, three phytoplasmids, and one algal plasmid (the accession numbers are shown). The GRS is designated by the dotted box, and dots above the alignment indicate positions of the GRS consensus residues. The protein alignment was performed by using Vector NTI AlignX, and the color scheme represents amino acid identity (yellow), conservation (blue), and blocks of similarity (green) (45). (B) Alignment of the structurally characterized Rep proteins from Tomato yellow leaf curl Sardinia virus (TYLCSV [8]), Faba bean necrotic yellows virus (FBNYV [74]), and Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2 [73]). The histidines in motif II and the catalytic tyrosine in motif III are marked by dots. Known structural elements are shown above the alignment for TYLCSV and below the alignment for FBNYV and PCV2 (75). (C) Model structure of TGMV AL1 amino acids 7 to 121. A PyMOL-generated protein ribbon model of TGMV AL1 based on the solved the 4-121 amino acid structure of TYLCSV Rep (PID 1L2M) (8) is shown. Selected residues in motif I (F16 and L17), motif II (H58 and H60), and motif III (Y104) are labeled. The inset box shows a rotated view including residues 8 Å from L17. The red mesh sphere shows the center of a hydrophobic cavity that could be created by mutating F77. The numbers indicate the angstrom distances from L17 to F77 or I92. The arrow shows a potential loop sequence between β6 and β7 strands (the amino acid numbering is for TGMV AL1, which is shifted by one position relative to the TYLCSV Rep structure [8] that served as the basis of the model). (D) The TGMV AL17-121 model was superimposed onto protein chains A and B of the SV40 T antigen bound to its cognate palindromic dsDNA (pdb code 2ITL). This model shows the positive protein surface of TGMV AL17-121 interacting with dsDNA. The electrostatic surface of the protein was created by using the Adaptive Poisson-Boltzmann Solver in PyMOL. In this model, R75 and K96 could contribute to dsDNA binding.

It has been proposed that geminiviruses evolved from rolling-circle plasmids associated with phytoplasma or algae (41, 49, 58). The plasmids encode Rep proteins with motifs I, II, and III arranged similarly to those in geminivirus (34, 40, 71). The GRS is also conserved among the phytoplasmid and algal Rep proteins with the R, F, D, and H residues at positions 1, 3, 4, and 15 identical to the geminivirus GRS consensus (Fig. 5A, numbering from Fig. 1B). The plasmid Reps lack six residues in the middle of the GRS like mastreviruses Rep proteins. The Rep proteins of phytoplasmids also match the GRS consensus at the P, I, A, and R residues at positions 16, 18, 21, and 22 in the GRS logo, which is consistent with their proposed close phylogenetic relationship to geminivirus Rep proteins (41).

Nanoviruses and circoviruses, which infect plants and animals, respectively, encode Rep proteins (34, 71) that are structurally similar to geminivirus Rep (8, 75). However, an alignment of the Rep proteins from Tomato yellow leaf curl Sardinia virus (TYLCSV; a geminivirus), Fava bean necrotic yellow virus (FBNYV; a nanovirus), and Porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2) did not uncover sequences related to the GRS consensus between motifs II and III of FBNYV or PCV2 (dotted box in Fig. 5B). The secondary structures of TYLCSV, FBNYV, and PCV2 Rep proteins also differ in the region as evidenced by the presence of two additional β-strands in TYLCSV Rep (β6 and β7 in Fig. 5B) (8). These results established that the GRS is not a general feature of eukaryotic rolling-circle initiator proteins and support the idea that the Rep proteins of geminiviruses, nanoviruses, and circoviruses are of different lineages (41).

DISCUSSION

Motifs I, II, and III were identified in rolling-circle initiator proteins nearly 20 years ago and subsequently shown to be essential for replication of many viral and plasmid DNAs (34, 40, 42, 52, 54). In the present study, we uncovered another sequence, the GRS, which displays strong conservation across all geminivirus Rep proteins (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Its discovery was facilitated by the large number of geminiviruses genome sequences that have been reported in recent years (21). The GRS represents the longest consecutive stretch of near-amino-acid identity in the overlapping DNA binding and cleavage domains of the Rep protein. GRS mutants are not infectious, do not support viral genome replication, and are not competent for ssDNA cleavage, establishing that the GRS is required for initiation of rolling-circle replication during geminivirus infection. GRS-related sequences also occur in the Rep proteins of phytoplasmal and algal plasmids but not those of nanoviruses and circoviruses. Together, the phylogenetic and functional data established that the GRS is a conserved, essential motif characteristic of an ancient lineage of rolling-circle initiators and supported the idea that geminiviruses evolved from plasmids associated with phytoplasma or algae (41, 49, 58).

The GRS consensus has 2 clusters of amino acids that display ≥ 89% identity across Rep proteins from 198 geminivirus species (Fig. 1B). The TGMV AL1 mutant, R-FD78, is altered in the N-terminal cluster, while the FH-N91 and IQ--K96 mutants are modified in the C-terminal cluster. Even though they are changed in different regions of the consensus, all three GRS mutants were not competent for DNA cleavage, a finding consistent with their inability to infect N. benthamiana plants or support viral genome replication in tobacco protoplasts. However, the three GRS mutants were active for DNA binding and protein interactions, indicating that they do not globally impact AL1 function and, by inference, its structure. This result was very different from earlier studies of motif I, II, and III mutants, which were defective for both DNA binding and cleavage (52), and suggested that the GRS defect occurs via a distinct mechanism.

To better understand the role of the GRS on Rep structure and function, we created a model of TGMV AL17-121 based on the solved NMR structure of TYLCSV Rep4-121 (8). The N termini of TYLCSV and TGMV Rep proteins show 74 and 88% amino acid identity and similarity, respectively, and their GRSs are identical at 22 of 23 positions (cf. Fig. 5A and B). The modeled TGMV AL17-121 ribbon structure shows a central 5-stranded β-sheet, two α-helices and two 2-stranded β-strand elements (Fig. 5C). Residues associated with motifs I and II are located primarily on the surface of the β-sheet, while motif III residues are in an α-helix positioned above the sheet. The GRS encompasses three β-strands designated β6, β7, and β8 and adjacent unstructured regions. The β8 strand is part of the 5-stranded β-sheet that is conserved in many rolling-circle initiators, including the nanovirus and circovirus Rep proteins (71, 75). In contrast, the β6 and β7 strands are unique to geminivirus Rep proteins and may be specifically associated with the GRS. The loop between the β6 and β7 strands corresponds to the more variable central region of the GRS and the residues absent in mastrevirus Reps and those of phytoplasmal and algal plasmids.

In the TGMV AL17-121 model, the GRS is located on the opposite side of the protein domain from Y104 in the DNA cleavage catalytic site (42), and it is unlikely that the GRS plays a direct role in DNA cleavage. To gain insight into why GRS mutations knock out Rep cleavage activity, we examined the roles of individual GRS residues in the model. Key residues (shown in stick in Fig. 5C) in motifs I, II, and III and the GRS are close to each other in the tertiary structure. The inset in Fig. 5C shows all of the TGMV AL1 residues within an 8-Å cutoff of motif I residue L17. Strikingly, three highly conserved GRS residues (F77, N91, and I92) and residues from the three RCR motifs (F16, H58, H60, and Y104) are within the 8-Å distance. In the TGMV AL1 model, F77 and I92 are 3.6 and 3.9 Å from L17, respectively, with the three residues, forming a contiguous hydrophobic core that is buried in the interior of the β-sheet structure. Although N91 is partially solvent exposed, it is also in close proximity to the hydrophobic core. Thus, replacement of the bulky side chains of F77, N91, or I92 by methyl groups in the GRS alanine substitutions is likely to disrupt the hydrophobic core of the protein (20, 77). This is illustrated in a structural model incorporating the F77A mutation, which is predicted to cause the formation of a large hydrophobic cavity (shown as a red mesh ball in Fig. 5C). The GRS mutants contained multiple alanine substitutions, and others not discussed here may have also contributed to destabilization of the hydrophobic core.

In model systems, proteins mutated specifically to create interior hydrophobic cavities undergo conformational changes to maximize hydrophobic packing and stabilize their structures (4, 19, 20, 43). These changes are often subtle, involving small shifts in structure (43). In the GRS mutants, the central β-sheet may have shifted to compensate for the formation of a hydrophobic cavity created by the alanine substitutions. The shift was probably small in magnitude because the GRS mutants are competent in DNA binding and protein interactions, but it may have altered distances critical for DNA cleavage activity. For example, a shift in the position of the central β-sheet could increase the distance between the catalytic residue Y104, which resides on the α-helix located above the sheet, and residues H58 and H60, which protrude from the surface of the sheet and coordinate a metal ion required for DNA cleavage (34, 40, 42, 52). Alternatively, a conformational change might shift the position of Y104 relative to the ssDNA substrate bound to the β-sheet (8). In either case, DNA cleavage activity would be impaired rendering Rep unable to support viral genome replication or infection.

Rep proteins are thought to bind to dsDNA via electrostatic interactions between a cluster of positively charged amino acids protruding from a curved, extended sheet adjacent to the central β-sheet (8). This interaction is illustrated in Fig. 5D, which shows an electrostatic surface representation with the positive potential (blue) of TGMV AL17-121 interacting with negatively charged dsDNA. The interaction surface includes R75 and K96, which were changed to alanines in the GRS mutants R-FD78 and IQ--K96, respectively. Both mutants were competent for dsDNA binding, indicating that the loss of a single charged residue along the entire charged surface of Rep is not sufficient to disrupt dsDNA binding. Residues Q9, N11, C70, and Q72, which are predicted to determine dsDNA binding specificity (2, 44), are in an unstructured region of TGMV AL1 adjacent to the electrostatic surface. Thus, it is also unlikely that a small shift in the position of the central β-sheet would impact their abilities to contact dsDNA.

ssDNA is thought to bind to Rep through exposed hydrophobic residues on the surface of the central β-sheet (8). The C terminus of the GRS overlaps with β8, the fifth strand of the β-sheet (Fig. 5B), and our GRS mutants included three residues in the sheet: N91, I92, and Q93. I92, the only hydrophobic residue that was mutated in β8, is not solvent exposed in the TGMV AL17-121 structure and thus unavailable for contacting ssDNA. Furthermore, like dsDNA binding, it is unlikely that the loss of a single contact would be sufficient to disrupt ssDNA binding, especially given that no specific contacts have to be maintained.

The results described here establish the GRS as a highly conserved motif in geminivirus Rep proteins that is required for initiation of rolling-circle replication. Modeling studies suggested that some GRS residues contribute to the structural integrity of the Rep protein but do not obviate other potential functions of the motif. One interesting possibility is that the central GRS residues, which are highly conserved in the Rep proteins of begomoviruses, curtoviruses, and topocuviruses but not mastreviruses, were acquired later in geminivirus evolution during their adaptation to dicotyledonous plants (49, 58). The central region of the GRS is predicted to be unstructured and on the Rep surface, and as such, may be involved in a yet-to-be-characterized host interaction. In addition, the presence of the GRS motif in plasmid-encoded Rep sequences from phytoplasma and alga plasmids may provide further insight into the evolutionary origin of geminiviruses (41, 49, 58, 72). Lastly, because of its strong conservation and essential nature, the GRS may serve as a new target for the development of broad-based geminivirus disease resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dominique Robertson (NCSU Plant Biology) and Wei Shen (NCSU Molecular and Structural Biochemistry) for their comments and suggestions.

This study was supported by NRI-USDA grant 2006-35319-17212 to L.H.-B.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 November 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ach, R. A., et al. 1997. RRB1 and RRB2 encode maize retinoblastoma-related proteins that interact with a plant D-type cyclin and geminivirus replication protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5077-5086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arguello-Astorga, G. R., and R. Ruiz-Medrano. 2001. An iteron-related domain is associated to motif 1 in the replication proteins of geminiviruses: identification of potential interacting amino acid base pairs by a comparative approach. Arch. Virol. 146:1465-1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold, K., L. Bordoli, J. Kopp, and T. Schwede. 2006. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modeling. Bioinformatics 22:195-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baase, W. A., L. Liu, D. E. Tronrud, and B. W. Matthews. 2010. Lessons from the lysozyme of phage T4. Protein Sci. 19:631-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagewadi, B., S. Chen, S. K. Lal, N. R. Choudhury, and S. K. Mukherjee. 2004. PCNA interacts with Indian mung bean yellow mosaic virus Rep and downregulates Rep activity. J. Virol. 78:11890-11903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunger, A. T. 2007. Version 1.2 of the crystallography and NMR system. Nat. Protoc. 2:2728-2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunger, A. T., et al. 1998. Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54:905-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campos-Olivas, R., J. M. Louis, D. Clerot, B. Gronenborn, and A. M. Gronenborn. 2002. The structure of a replication initiator unites diverse aspects of nucleic acid metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:10310-10315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castillo, A. G., D. Collinet, S. Deret, A. Kashoggi, and E. R. Bejarano. 2003. Dual interaction of plant PCNA with geminivirus replication accessory protein (Ren) and viral replication protein (Rep). Virology 312:381-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castillo, A. G., L. J. Kong, L. Hanley-Bowdoin, and E. R. Bejarano. 2004. Interaction between a geminivirus replication protein and the plant sumoylation system. J. Virol. 78:2758-2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choudhury, N. R., et al. 2006. The oligomeric Rep protein of Mungbean yellow mosaic India virus (MYMIV) is a likely replicative helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:6362-6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clerot, D., and F. Bernardi. 2006. DNA helicase activity is associated with the replication initiator protein Rep of Tomato yellow leaf curl geminivirus. J. Virol. 80:11322-11330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crooks, G. E., G. Hon, J. M. Chandonia, and S. E. Brenner. 2004. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14:1188-1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLano, W. L. 2002. The PyMol molecular graphics system. Schrodinger, New York, NY. www.pymol.org.

- 15.Dellaporta, S. L., J. Wood, and J. B. Hicks. 1983. A plant DNA minipreparation: version II. Plant. Mol. Biol. Rep. 1:19-21. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desbiez, C., C. David, A. Mettouchi, J. Laufs, and B. Gronenborn. 1995. Rep. protein of tomato yellow leaf curl geminivirus has an ATPase activity required for viral DNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:5640-5644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eagle, P. A., B. M. Orozco, and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 1994. A DNA sequence required for geminivirus replication also mediates transcriptional regulation. Plant Cell 6:1157-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elmer, J. S., et al. 1988. Genetic analysis of the tomato golden mosaic virus. II. The product of the AL1 coding sequence is required for replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:7043-7060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eriksson, A. E., W. A. Baase, and B. W. Matthews. 1993. Similar hydrophobic replacements of Leu99 and Phe153 within the core of T4 lysozyme have different structural and thermodynamic consequences. J. Mol. Biol. 229:747-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eriksson, A. E., et al. 1992. Response of a protein structure to cavity-creating mutations and its relation to the hydrophobic effect. Science 255:178-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fauquet, C. M., et al. 2008. Geminivirus strain demarcation and nomenclature. Arch. Virol. 153:783-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fontes, E. P., P. A. Eagle, P. S. Sipe, V. A. Luckow, and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 1994. Interaction between a geminivirus replication protein and origin DNA is essential for viral replication. J. Biol. Chem. 269:8459-8465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fontes, E. P., H. J. Gladfelter, R. L. Schaffer, I. T. Petty, and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 1994. Geminivirus replication origins have a modular organization. Plant Cell 6:405-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fontes, E. P., V. A. Luckow, and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 1992. A geminivirus replication protein is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein. Plant Cell 4:597-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gladfelter, H. J., P. A. Eagle, E. P. Fontes, L. Batts, and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 1997. Two domains of the AL1 protein mediate geminivirus origin recognition. Virology 239:186-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grafi, G., et al. 1996. A maize cDNA encoding a member of the retinoblastoma protein family: involvement in endoreduplication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:8962-8967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gutierrez, C. 1999. Geminivirus DNA replication. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 56:313-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gutierrez, C., et al. 2004. Geminivirus DNA replication and cell cycle interactions. Vet. Microbiol. 98:111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guzzo, A. V. 1965. The influence of amino acid sequence on protein structure. Biophys. J. 5:809-822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamilton, W. D., V. E. Stein, R. H. Coutts, and K. W. Buck. 1984. Complete nucleotide sequence of the infectious cloned DNA components of Tomato golden mosaic virus: potential coding regions and regulatory sequences. EMBO J. 3:2197-2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanley-Bowdoin, L., S. B. Settlage, B. M. Orozco, S. Nagar, and D. Robertson. 2000. Geminiviruses: models for plant DNA replication, transcription, and cell cycle regulation. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 35:105-140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanley-Bowdoin, L., S. B. Settlage, and D. Robertson. 2004. Reprogramming plant gene expression: a prerequisite to geminivirus DNA replication. Mol. Plant Pathol. 5:149-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heyraud-Nitschke, F., et al. 1995. Determination of the origin cleavage and joining domain of geminivirus Rep proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:910-916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ilyina, T. V., and E. V. Koonin. 1992. Conserved sequence motifs in the initiator proteins for rolling circle DNA replication encoded by diverse replicons from eubacteria, eucaryotes, and archaebacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:3279-3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeske, H., M. Lutgemeier, and W. Preiss. 2001. DNA forms indicate rolling circle and recombination-dependent replication of Abutilon mosaic virus. EMBO J. 20:6158-6167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiefer, F., K. Arnold, M. Kunzli, L. Bordoli, and T. Schwede. 2009. The SWISS-MODEL repository and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D387-D392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kleywegt, G. J. 1996. Use of non-crystallographic symmetry in protein structure refinement. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 52:842-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kong, L. J., and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 2002. A geminivirus replication protein interacts with a protein kinase and a motor protein that display different expression patterns during plant development and infection. Plant Cell 14:1817-1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong, L. J., et al. 2000. A geminivirus replication protein interacts with the retinoblastoma protein through a novel domain to determine symptoms and tissue specificity of infection in plants. EMBO J. 19:3485-3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koonin, E. V., and T. V. Ilyina. 1992. Geminivirus replication proteins are related to prokaryotic plasmid rolling circle DNA replication initiator proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 73:2763-2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krupovic, M., J. J. Ravantti, and D. H. Bamford. 2009. Geminiviruses: a tale of a plasmid becoming a virus. BMC Evol. Biol. 9:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laufs, J., et al. 1995. In vitro cleavage and joining at the viral origin of replication by the replication initiator protein of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:3879-3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee, J., K. Lee, and S. Shin. 2000. Theoretical studies of the response of a protein structure to cavity-creating mutations. Biophys. J. 78:1665-1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Londono, A., L. Riego-Ruiz, and G. R. Arguello-Astorga. 2010. DNA-binding specificity determinants of replication proteins encoded by eukaryotic ssDNA viruses are adjacent to widely separated RCR conserved motifs. Arch. Virol. 155:1033-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu, G., and E. N. Moriyama. 2004. Vector NTI, a balanced all-in-one sequence analysis suite. Brief Bioinform. 5:378-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luque, A., A. P. Sanz-Burgos, E. Ramirez-Parra, M. M. Castellano, and C. Gutierrez. 2002. Interaction of geminivirus Rep protein with replication factor C and its potential role during geminivirus DNA replication. Virology 302:83-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malik, P. S., V. Kumar, B. Bagewadi, and S. K. Mukherjee. 2005. Interaction between coat protein and replication initiation protein of Mung bean yellow mosaic India virus might lead to control of viral DNA replication. Virology 337:273-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagar, S., T. J. Pedersen, K. M. Carrick, L. Hanley-Bowdoin, and D. Robertson. 1995. A geminivirus induces expression of a host DNA synthesis protein in terminally differentiated plant cells. Plant Cell 7:705-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nawaz-ul-Rehman, M. S., and C. M. Fauquet. 2009. Evolution of geminiviruses and their satellites. FEBS Lett. 583:1825-1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Orozco, B. M., et al. 1998. Multiple cis elements contribute to geminivirus origin function. Virology 242:346-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Orozco, B. M., and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 1996. A DNA structure is required for geminivirus replication origin function. J. Virol. 70:148-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orozco, B. M., and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 1998. Conserved sequence and structural motifs contribute to the DNA binding and cleavage activities of a geminivirus replication protein. J. Biol. Chem. 273:24448-24456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Orozco, B. M., L. J. Kong, L. A. Batts, S. Elledge, and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 2000. The multifunctional character of a geminivirus replication protein is reflected by its complex oligomerization properties. J. Biol. Chem. 275:6114-6122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Orozco, B. M., A. B. Miller, S. B. Settlage, and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 1997. Functional domains of a geminivirus replication protein. J. Biol. Chem. 272:9840-9846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peitsch, M. C. 1995. Protein modeling by E-mail. Biotechnology (NY) 13:658-660. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rogers, S. G., Elmer, et al. 1989. Molecular genetics of Tomato golden mosaic virus, p. 199-215. In B. Staskawick, P. Ahlquist, and O. Yoder (ed.), Molecular biology of plant-pathogen interactions, Alan R. Liss, Inc., New York, NY.

- 57.Rojas, M. R., R. L. Gilberson, D. R. Russell, and D. P. Maxwell. 1993. Use of degenerate primers in the polymerase chain reaction to detect whitefly-transmitted geminiviruses. Plant Dis. 77:340-347. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rojas, M. R., C. Hagen, W. J. Lucas, and R. L. Gilbertson. 2005. Exploiting chinks in the plant's armor: evolution and emergence of geminiviruses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43:361-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rother, K., P. W. Hildebrand, A. Goede, B. Gruening, and R. Preissner. 2009. Voronoia: analyzing packing in protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D393-D395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Santos, A. A., L. H. Florentino, A. B. Pires, and E. P. Fontes. 2008. Geminivirus: biolistic inoculation and molecular diagnosis. Methods Mol. Biol. 451:563-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schneider, T. D., and R. M. Stephens. 1990. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:6097-6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Settlage, S. B., A. B. Miller, W. Gruissem, and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 2001. Dual interaction of a geminivirus replication accessory factor with a viral replication protein and a plant cell cycle regulator. Virology 279:570-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Settlage, S. B., A. B. Miller, and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 1996. Interactions between geminivirus replication proteins. J. Virol. 70:6790-6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shen, W., and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 2006. Geminivirus infection up-regulates the expression of two Arabidopsis protein kinases related to yeast SNF1 and mammalian AMPK-activating kinases. Plant Physiol. 142:1642-1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shen, W., M. I. Reyes, and L. Hanley-Bowdoin. 2009. Arabidopsis protein kinases GRIK1 and GRIK2 specifically activate SnRK1 by phosphorylating its activation loop. Plant Physiol. 150:996-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Singh, D. K., M. N. Islam, N. R. Choudhury, S. Karjee, and S. K. Mukherjee. 2007. The 32-kDa subunit of replication protein A (RPA) participates in the DNA replication of Mung bean yellow mosaic India virus (MYMIV) by interacting with the viral Rep. protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:755-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Singh, D. K., P. S. Malik, N. R. Choudhury, and S. K. Mukherjee. 2008. MYMIV replication initiator protein (Rep.): roles at the initiation and elongation steps of MYMIV DNA replication. Virology 380:75-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stanley, J., et al. 2005. Geminiviridae, p. 301-326. In C. M. Fauquet, J. Maniloff, U. Desselberger, and L. A. Ball (ed.), Virus taxonomy. Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier Academic Press, London, England.

- 69.Sunter, G., M. D. Hartitz, and D. M. Bisaro. 1993. Tomato golden mosaic virus leftward gene expression: autoregulation of geminivirus replication protein. Virology 195:275-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thommes, P., T. A. Osman, R. J. Hayes, and K. W. Buck. 1993. TGMV replication protein AL1 preferentially binds to single-stranded DNA from the common region. FEBS Lett. 319:95-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vadivukarasi, T., K. R. Girish, and R. Usha. 2007. Sequence and recombination analyses of the geminivirus replication initiator protein. J. Biosci. 32:17-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Varsani, A., D. N. Shepherd, K. Dent., A. L. Monjane, E. P. Rybicki, and D. P. Martin. 2009. A highly divergent South African geminivirus species illuminates the ancient evolutionary history of this family. Virol. J. 6:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vega-Rocha, S., I. J. Byeon, B. Gronenborn, A. M. Gronenborn, and R. Campos-Olivas. 2007. Solution structure, divalent metal and DNA binding of the endonuclease domain from the replication initiation protein from porcine circovirus 2. J. Mol. Biol. 367:473-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vega-Rocha, S., A. M. Gronenborn, B. Gronenborn, and R. Campos-Olivas. 2007. 1H, 13C, and 15N NMR assignment of the master Rep protein nuclease domain from the nanovirus FBNYV. J. Biomol. NMR 38:169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vega-Rocha, S., B. Gronenborn, A. M. Gronenborn, and R. Campos-Olivas. 2007. Solution structure of the endonuclease domain from the master replication initiator protein of the nanovirus faba bean necrotic yellows virus and comparison with the corresponding geminivirus and circovirus structures. Biochemistry 46:6201-6212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xie, Q., P. Suarez-Lopez, and C. Gutierrez. 1995. Identification and analysis of a retinoblastoma binding motif in the replication protein of a plant DNA virus: requirement for efficient viral DNA replication. EMBO J. 14:4073-4082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xu, J., W. A. Baase, E. Baldwin, and B. W. Matthews. 1998. The response of T4 lysozyme to large-to-small substitutions within the core and its relation to the hydrophobic effect. Protein Sci. 7:158-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.