Abstract

Purpose

We compared the prevalence of disability among older American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) with that among their African American and White peers, then examined sociodemographic characteristics associated with disability among AI/ANs.

Design and Methods

We analyzed the 5% 2000 Census Public Use Microdata Sample. We assessed disability by functional limitation, mobility disability, and self-care disability for four age groups (55–64, 65–74, 75–84, and 85 years or older).

Results

For all age strata, AI/ANs reported the highest rates of functional limitation and African Americans the highest level of mobility disability. In the 55-to-64 age group, AI/ANs experienced the highest prevalence of self-care disability, and among those aged 65 years or older, African Americans reported the highest prevalence. Compared to Whites, the adjusted odds ratios for functional limitation, mobility disability, and self-care disability were significantly elevated in AI/ANs (1.62, 1.33, and 1.56, respectively) and African Americans (1.27, 1.54, and 1.56, respectively). For AI/ANs, being of increased age, being female, having lower educational attainment and household income, not being married or in the labor force, and residing in a metropolitan area were associated with disabilities.

Implications

This study contributes to researchers’ limited knowledge regarding disability among older AI/ANs. The lack of available empirical data poses obstacles to understanding the antecedents and consequences of disability for AI/ANs. More information on the nature and extent of disabilities among AI/AN elders would enhance the ability of advocates to document their needs and raise public awareness. Likewise, policy makers could enact prevention strategies and make comprehensive rehabilitative and long-term care services available to this population.

Keywords: American Indians and Alaska Natives, Older adults, Disability, US Census

The scant literature on disabilities among American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) suggests that this understudied minority suffers some of the highest rates of disability of any U.S. racial group (Barnes, Adams, & Powell-Griner, 2005; Hayward & Heron, 1999; John, 2004; John, Hennessy, & Denny, 1999; Waidmann & Liu, 2000). Rates of disability among AI/ANs far exceed those of their non-Hispanic White counterparts. Data from the 1992–1996 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey indicated that 30% of AI/AN Medicare beneficiaries had one or more limitations in performing an activity of daily living (ADL) compared to 17% of Whites (Waidmann & Liu, 2000). Another analysis based on 1990 Census data noted that mobility limitations, self-care limitations, and work disability were more prevalent among older AI/ANs than non-Hispanic Whites (John, 2004; John et al., 1999). An analysis of the Census 2000 Supplementary Survey found that AI/ANs 45 years or older with functional limitations were older, poorer, less educated, and less likely to be married or employed than those without limitations (Fuller-Thomson & Minkler, 2005). These findings were congruent to those found among older adults in the general U.S. population (Hayward & Heron, 1999; Manton, 1989; Onder et al., 2002).

Though provocative, many previous studies have only examined AI/ANs residing in circumscribed geographic regions (Chapleski, Lichtenberg, Dwyer, Youngblade, & Tsai, 1997; Goins, Spencer, Roubideaux, & Manson, 2005; Moss, Roubideaux, Jacobsen, Buchwald, & Manson, 2004) and have lacked comparison groups (Chapleski et al., 1997; Fuller-Thomson & Minkler, 2005). This work highlights the need to better understand the extent of disabilities experienced by older AI/ANs compared to other racial groups and the relationship of disability with sociodemographic characteristics. We, therefore, examined rates of disability among AI/ANs, African Americans, and Whites aged 55 years or older using national data. This study asked three questions: (a) What is the prevalence of disability among older AI/ANs compared with same-age peers of other races? (b) What is the likelihood of having a disability among AI/ANs compared to same-age peers of other races, adjusting for associated sociodemographic characteristics? and (c) What are the sociodemographic correlates of disability among AI/ANs?

Methods

Data

We based this study on individual-level data from 2,944,755 individuals who completed the long form in the 2000 U.S. Census 5% Public Use Microdata Sample. This is a representative sample of housing units and their residents as well as individuals living in group quarters. The sample is a stratified sub-sample drawn from the full Census enumeration; housing units and individuals were randomly selected to receive the long form questionnaire. On average, 1 in 6 households received the long form.

Measures

All data were self-reported. Sociodemographic items included age, gender, race, educational attainment, annual household income, marital status, metropolitan residence, and current labor force participation. Reporting multiple race categories was permitted for the first time in the 2000 U.S. Census. We limited our analyses to respondents aged 55 years or older who reported being only AI/AN, African American, and White. Individuals reporting multiple races were beyond the scope of this study. Educational attainment and annual household income were ordinal variables, and we measured education using seven categories (≤8th grade, 9th–12th grade, high school graduate/General Educational Development, some college/trade school, college graduate, and postbaccalaureate). There were too few individuals by race represented in all 17 response categories in the original education variable, so we collapsed them into these 7 categories. Annual household income included the primary family's total pre-tax money income from all sources during the previous year. We measured income using five categories ($0–$14,999, $15,000–$24,999, $25,000–$34,999, $35,000–$44,999, and ≥$45,000). The original income variable consisted of actual values for each household. Marital status was a nominal variable and indicated whether the respondent was married with a spouse present, married with an absent spouse, separated, divorced, widowed, or never married/single. Metropolitan residence was defined based on the Office of Management and Budget definition; non-metropolitan areas were those that do not fit these criteria (Office of Management and Budget, 2000). We considered individuals in the labor force, including the Armed Forces, to be currently employed.

Outcomes

The outcome of interest was disability as ascertained by a single item with a yes/no response option for three measures: functional limitation, mobility disability, and self-care disability. Functional limitation indicates that respondents had long-lasting conditions that limited them with one or more activity such as walking, climbing stairs, reaching, lifting, or carrying. The question was as follows: “Does this person/do you have a condition that substantially limits one or more basic physical activities such as walking, climbing stairs, reaching, lifting, or carrying?” Mobility disability indicates whether the respondent had any physical or mental health condition that had lasted 6 months or longer, making it difficult or impossible to go outside of the home alone. Respondents were asked the following question: “Because of a physical, mental, or emotional condition lasting 6 months or more, does this person/do you have any difficulty going outside the home alone to shop or visit a doctor's office?” Self-care disability indicates whether respondents had any physical or mental health condition that had lasted 6 or more months, making it difficult for them to take care of basic activities such as bathing, dressing, or getting around in the home. They were asked the following question: “Because of a physical, mental, or emotional condition lasting 6 or more months, does this person/do you have any difficulty dressing, bathing, or getting around inside the home?” Previous research compared these three items to limitations with ADLs and instrumental ADLs (standard measures of disability) and found them to have adequate reliability and validity (Calsyn, Winter, & Yonker, 2001).

Analyses

Descriptive analyses examined sociodemographic characteristics and disability status by race. We fitted two logistic regression models for each of the three disability items, with race as the independent variable, with and without adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics. We fitted three additional logistic regressions models for each of the disability items for AI/ANs alone with the sociodemographic characteristics as the independent variables. For all models, we report the odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for the association between the independent variables and disability. We performed all analyses using SAS software package version 8.1 (SAS Institute, 1999).

Results

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic findings by race. More than half of the AI/ANs were 55 to 64 years of age, compared with 45% of African Americans and 39% of Whites. The mean age was 66 for AI/ANs, 68 for African Americans, and 69 for Whites (data not shown). Approximately 55% to 60% of each racial group was female. The AI/AN sample had the largest percentage of respondents reporting an educational level of eighth grade or lower and the smallest proportion residing in a metropolitan area. All races had about 30% of participants currently in the labor force.

Table 1.

Sociodemographics of the Sample by Race

| Characteristic | AI/AN, % n = 17,946 | African American, % n = 253,725 | White, % n = 2,673,084 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 55–64 | 52.1 | 44.7 | 39.4 |

| 65–74 | 29.5 | 31.1 | 30.9 |

| 75–84 | 14.1 | 17.9 | 21.9 |

| ≥85 | 4.2 | 6.3 | 7.8 |

| Female | 54.9 | 59.2 | 55.7 |

| Education | |||

| ≤8th grade | 26.7 | 23.0 | 11.5 |

| 9th–12th grade, no diploma | 20.7 | 26.7 | 15.1 |

| High school graduate | 24.6 | 24.6 | 33.9 |

| Some college or associate's degree | 19.4 | 15.8 | 21.2 |

| College graduate | 4.9 | 5.1 | 10.3 |

| Postbaccalaureate | 3.8 | 4.8 | 8.1 |

| Annual household income | |||

| $0–$14,999 | 31.5 | 32.4 | 17.4 |

| $15,000–$24,999 | 16.7 | 15.8 | 15.7 |

| $25,000–$34,999 | 13.6 | 12.3 | 14.2 |

| $35,000–$44,999 | 10.1 | 9.6 | 11.6 |

| ≥$45,000 | 28.1 | 30.0 | 41.0 |

| Spouse present | 48.8 | 38.7 | 60.9 |

| Metropolitan residence | 49.7 | 82.6 | 71.7 |

| Currently in labor force | 30.1 | 28.8 | 31.2 |

Note: AI/AN = American Indian and Alaska Native

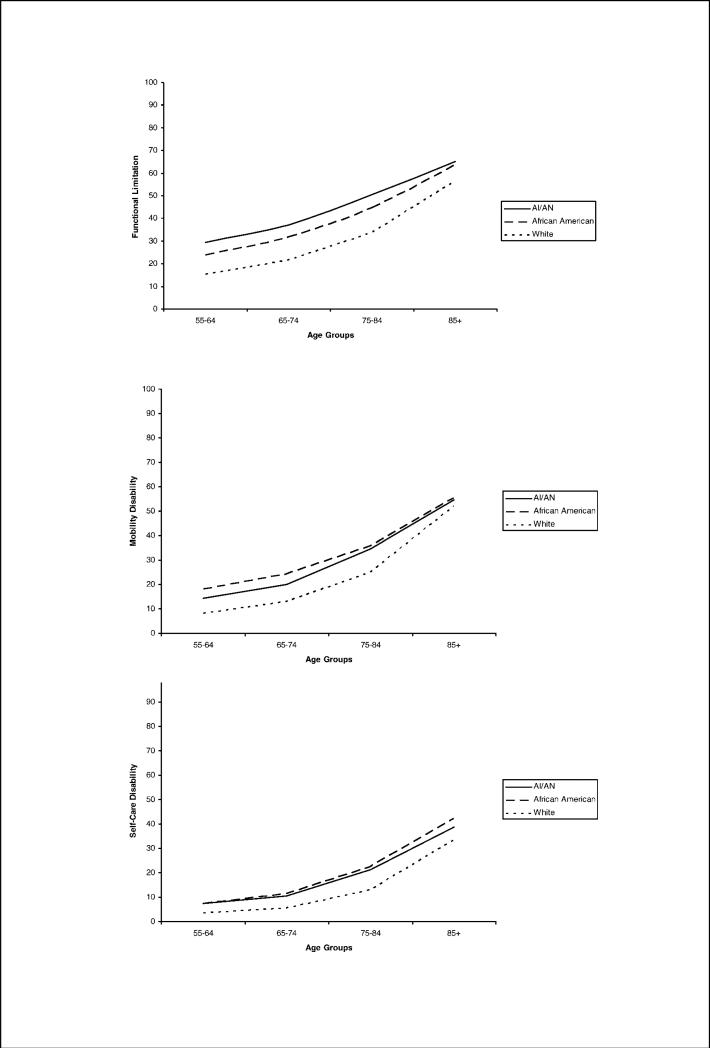

The prevalence of functional limitation, mobility disability, and self-care disability was 36.2%, 20.6%, and 11.6% for AI/ANs; 32.7%, 25.7%, and 13.6% for African Americans; and 24.6%, 16.8%, and 8.7% for Whites, respectively. Figure 1 displays the un-adjusted prevalence of disability by race and age strata. For all age groups, AI/ANs reported the highest prevalence rates of functional limitation compared to African Americans and Whites. For mobility disability, African Americans reported the highest prevalence rates for all age groups. For self-care disability, AI/ANs and African Americans had approximately the same prevalence for ages 55 to 64, whereas African Americans had the highest prevalence rates for those aged 65 years or older. Across all age strata and for all three measures of disability, AI/ANs had higher rates than Whites.

Figure 1.

Disability by race and age. AI/AN = American Indian and Alaska Native.

Table 2 presents the results from three logistic regression models estimating the odds of disability by race alone and three logistic regression models estimating the odds of disability by race adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics. Unadjusted odd ratios showed higher odds of reporting a disability among AI/ANs and African Americans compared to same-aged Whites. After we adjusted for sociodemographics, AI/ANs and African Americans compared to same-aged Whites continued to have increased odds of reporting a disability. Specifically, AI/ANs compared to Whites had increased odds of 62% for reporting a functional limitation, 33% for reporting a mobility disability, and 56% for reporting a self-care disability.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for Estimating Disability for All Persons ≥ 55 Years of Age

| Functional Limitation |

Mobility Disability |

Self-Care Disability |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | OR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI |

| Racea | ||||||||||||

| AI/AN | 1.75 | 1.69–1.80 | 1.62 | 1.56–1.68 | 1.28 | 1.24–1.33 | 1.33 | 1.27–1.39 | 1.37 | 1.31–1.44 | 1.56 | 1.47–1.65 |

| African American | 1.49 | 1.48–1.50 | 1.27 | 1.25–1.28 | 1.71 | 1.69–1.73 | 1.54 | 1.52–1.55 | 1.66 | 1.63–1.68 | 1.56 | 1.54–1.58 |

| Age | 1.03 | 1.03–1.03 | 1.05 | 1.05–1.05 | 1.05 | 1.05–1.05 | ||||||

| Female | 0.89 | 0.88–0.90 | 1.04 | 1.03–1.05 | 1.05 | 1.04–1.06 | ||||||

| Educationb | ||||||||||||

| ≤8th grade | 2.26 | 2.23–2.30 | 2.92 | 2.86–2.97 | 2.17 | 2.11–2.23 | ||||||

| 9th–12th grade, no diploma | 1.89 | 1.86–1.92 | 2.31 | 2.27–2.36 | 1.58 | 1.54–1.62 | ||||||

| High school graduate | 1.40 | 1.38–1.42 | 1.72 | 1.68–1.74 | 1.27 | 1.24–1.30 | ||||||

| Some college or associate's degree | 1.44 | 1.42–1.46 | 1.45 | 1.42–1.48 | 1.15 | 1.12–1.18 | ||||||

| College graduate | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | 1.08 | 1.06–1.11 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.05 | ||||||

| Annual household incomec | ||||||||||||

| $0–$14,999 | 1.52 | 1.50–1.53 | 1.27 | 1.26–1.29 | 1.23 | 1.21–1.25 | ||||||

| $15,000–$24,999 | 1.27 | 1.25–1.28 | 1.09 | 1.08–1.10 | 1.03 | 1.02–1.05 | ||||||

| $25,000–$34,999 | 1.18 | 1.16–1.19 | 1.05 | 1.04–1.07 | 1.00 | 0.98–1.01 | ||||||

| $35,000–$44,999 | 1.12 | 1.11–1.14 | 1.04 | 1.03–1.05 | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | ||||||

| Spouse present | 0.67 | 0.66–0.67 | 0.65 | 0.66–0.64 | 0.65 | 0.64–0.65 | ||||||

| Metropolitan residence | 0.89 | 0.89–0.90 | 1.05 | 1.04–1.05 | 0.96 | 0.95–0.97 | ||||||

| Currently in labor force | 0.35 | 0.35–0.35 | 0.53 | 0.52–0.54 | 0.28 | 0.27–0.28 | ||||||

| Model chi-square | p ≤ .0001 | p ≤ .0001 | p ≤ .0001 | |||||||||

Notes: AI/AN = American Indian and Alaska Native; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; AOR = adjusted odds ratio.

Reference = White.

Reference = postbaccalaureate.

Reference = ≥$45,000.

Table 3 presents the results from three logistic regression models to estimate disability for AI/ANs using a saturated model that included our seven sociodemographic characteristics. A year increase in age increased the odds of reporting one of the disability measures between 2% and 4%. Overall, having lower levels of education compared with postbaccalaureate educational attainment increased the likelihood of reporting a functional limitation, mobility disability, and/or self-care disability. Having a spouse present and being in the labor force decreased the odds of reporting one of the disability measures between 25% and 30%, and 63% and 77%, respectively. Having lower household income compared to household incomes of $45,000 or greater increased the likelihood of reporting a functional limitation. Being female increased the odds of having a mobility disability by 10%. Residing in a metropolitan area compared to a nonmetropolitan area increased the odds of having a mobility disability and self-care disability by 12% each.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for Estimating Disability for American Indians and Alaska Natives ≥55 Years of Age

| Functional Limitation |

Mobility Disability |

Self-Care Disability |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI |

| Age | 1.02 | 1.01–1.02 | 1.04 | 1.03–1.04 | 1.04 | 1.03–1.04 |

| Female | 0.98 | 0.91–1.05 | 1.10 | 1.01–1.20 | 1.05 | 0.94–1.18 |

| Educationa | ||||||

| ≤8th grade | 1.69 | 1.34–2.12 | 1.96 | 1.46–2.65 | 1.58 | 1.06–2.35 |

| 9th–12th grade, no diploma | 1.40 | 1.11–1.77 | 1.52 | 1.13–2.05 | 1.30 | 0.87–1.95 |

| High school graduate | 1.28 | 1.01–1.61 | 1.34 | 0.99–1.80 | 1.20 | 0.81–1.80 |

| Some college or associate's degree | 1.31 | 1.04–1.65 | 1.22 | 0.90–1.65 | 1.26 | 0.84–1.90 |

| College graduate | 1.08 | 0.81–1.43 | 1.09 | 0.75–1.56 | 1.25 | 0.76–2.02 |

| Annual household incomeb | ||||||

| $0–$14,999 | 1.45 | 1.30–1.60 | 1.09 | 0.97–1.23 | 1.11 | 0.95–1.30 |

| $15,000–$24,999 | 1.43 | 1.28–1.61 | 1.09 | 0.95–1.25 | 1.06 | 0.89–1.27 |

| $25,000–$34,999 | 1.18 | 1.05–1.34 | 1.11 | 0.96–1.29 | 1.04 | 0.86–1.27 |

| $35,000–$44,999 | 1.34 | 1.17–1.53 | 1.09 | 0.92–1.29 | 1.12 | 0.90–1.40 |

| Spouse present | 0.75 | 0.69–0.81 | 0.74 | 0.69–0.81 | 0.70 | 0.78–0.62 |

| Metropolitan residence | 0.99 | 0.92–1.07 | 1.12 | 1.03–1.22 | 1.12 | 1.01–1.25 |

| Currently in labor force | 0.29 | 0.26–0.32 | 0.37 | 0.32–0.42 | 0.23 | 0.19–0.28 |

| Model chi-square | p ≤ .0001 | p ≤ .0001 | p ≤ .0001 | |||

Notes: AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Reference = postbaccalaureate.

Reference = ≥$45,000.

Discussion

We found that older AI/ANs experience high rates of disability, especially compared to Whites. For all age strata among adults aged 55 years or older, AI/ANs reported higher rates of functional limitation than Whites or African Americans. African Americans, however, had the highest prevalence of mobility disability. AI/ANs and African Americans experienced the same rates of self-care disability in the 55-to-64 age group, with African Americans reporting the highest rates in the remaining age groups. Overall, AI/ANs had significantly higher odds of reporting disability compared to Whites, even after we adjusted for sociodemographics. These findings are congruent with a previous analysis using the 1990 U.S. Census that documented that AI/ANs had higher levels of disability than Whites (John, 2004; John et al., 1999).

For AI/ANs, we also found that being of increased age, being female, having lower educational attainment and household income, not having a spouse present or being in the labor force, and residing in a metropolitan area were associated with increased likelihood of disability. Likewise, these characteristics were associated with functional limitation in a sample of AI/ANs aged 45 years or older from the Census 2000 Supplementary Survey (Fuller-Thomson & Minkler, 2005) and are consistent with results of other studies with older adults of other racial groups (Hayward & Heron, 1999; Manton, 1989; Onder et al., 2002). An analysis of the 1990 5% Public Use Microdata Sample found that for AI/ANs, older age and female gender were associated with a greater likelihood of having a disability (Hayward & Heron, 1999). However, among 309 Great Lake American Indians aged 55 years or older, gender, educational status, marital status, and residence were not associated with the likelihood of having limitations with ADLs or instrumental ADLs. Nonetheless, like our findings, increased age was associated with disability (Chapleski et al., 1997). Regarding residence and disability, our findings corroborate earlier research with urban older AI/ANs (Kramer, 1999).

Disability is one of the strongest predictors of needing and using long-term care among older adults. These data, as well as our own, speak to the need for prevention strategies for disability in this population as has been discussed by John and colleagues (1999). In this regard, older AI/ANs would benefit from increased availability of chronic disease management programs and physical activity intervention programs designed to improve strength, balance, and flexibility. Our findings also support the need to implement health policies that address long-term care issues in Indian Country (Baldridge, 2001; Finke, Jackson, Roebuck, & Baldridge, 2002; Goins & Spencer, 2005; Manson, 1989). Congress has never funded health care services for AI/ANs at levels that would provide health services comparable to those that other Americans receive. As a result, the Indian health care system is struggling to meet the needs of the AI/AN population with insufficient resources. This is becoming increasingly important because the number of AI/ANs aged 75 years or older who will need long-term care will double in the next 25 years (U.S. Census Bureau, 2005).

This study has several limitations. Although the availability of national data with substantial numbers of older AI/ANs is scarce, use of the U.S. Census data has inherent limitations. For example, we could not assess some potential correlates of disability, such as chronic diseases, depression, and social support. In addition, the cross-sectional nature of the data makes it impossible to distinguish between temporary and persistent disability or if certain sociodemographic characteristics preceded or resulted from a disability. Yet, these data offer advantages over alternative data sources for examining disability among older AI/ANs. The most prominent advantage is the large sample size, which permits race comparisons and encompasses participants from hundreds of tribes; most large national studies in the area of gerontological health do not include a substantial number of AI/ANs (Rhoades, 2006). Another concern is that single-item measures of any construct, such as those we used, have substantial limitations. Nonetheless, these domains of disability are the most commonly reported in the research literature, and the three items correlate well with longer, well-accepted measures of disability (Calsyn et al., 2001). Finally, the U.S. Census relies on racial self-identification; thus, our results may not reflect the disabilities experienced by more narrowly defined clinical populations of patients served by the Indian Health Service, virtually all of whom are tribally enrolled.

This study contributes to researchers’ limited knowledge regarding disability among older AI/ANs. The lack of representative, relevant, and applicable empirical data poses obstacles to better understanding disability among older AI/ANs. More information on the nature and extent of disabilities among AI/AN elders would enhance the ability of advocates to document needs and raise awareness and policy-makers to enact prevention strategies as well as ensuring access to comprehensive long-term care services to this population. Further research in this area is needed to aid in fostering a public health emphasis on addressing disabilities among older AI/ANs and all older Americans.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported in part by Grant 1 K01 AG022336-01A2 from the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health; the University of Minnesota; and the Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. We gratefully acknowledge Matthew Schell for his assistance with facilitating access to the data set. The Office of Research Compliance at West Virginia University deemed this study not human subject research by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Food and Drug Administration regulatory definitions. As such, it did not require institutional review board approval.

References

- Baldridge D. The elder Indian population and long-term care. In: Dixon M, Roubideaux Y, editors. Promises to keep: Public health policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 21st century. American Public Health Association; Washington, DC: 2001. pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PM, Adams PF, Powell-Griner E. Health characteristics of the American Indian and Alaska Native population: United States, 1999–2003. Advance Data. 2005;356:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Calsyn RJ, Winter JP, Yonker RD. Should disability items in the census be used for planning services for elders? The Gerontologist. 2001;41:583–588. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapleski EE, Lichtenberg PA, Dwyer JW, Youngblade LM, Tsai PF. Morbidity and comorbidity among Great Lakes American Indians: Predictors of functional ability. The Gerontologist. 1997;37:588–597. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.5.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finke B, Jackson Y, Roebuck L, Baldridge D. American Indian and Alaska Native roundtable on long-term care: Final report 2002. Indian Health Service; Rockville, MD: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Minkler M. Functional limitations among older American Indians and Alaska Natives: Findings from the Census 2000 Supplementary Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1945–1948. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goins RT, Spencer SM. Public health issues among older American Indians and Alaska Natives. Generations. 2005;29(2):30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Goins RT, Spencer SM, Roubideaux Y, Manson S. Differences in functional disability of rural American Indian and White elders with comorbid diabetes. Research on Aging. 2005;27:643–658. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward MD, Heron M. Racial inequality in active life among adult Americans. Demography. 1999;36:77–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John R. Health status and health disparities among American Indian elders. In: Whitfield KE, editor. Closing the gap. The Gerontological Society of America; Washington, DC: 2004. pp. 28–49. [Google Scholar]

- John R, Hennessy CH, Denny CH. Preventing chronic illness and disability among Native American elders. In: Wykle MK, Ford AB, editors. Serving minority elders in the 21st century. Springer; New York: 1999. pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer BJ. The health status of urban Indian elders. IHS Primary Care Provider. 1999;24(5):69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM. Long-term care in American Indian communities: Issues for planning and research. The Gerontologist. 1989;29:38–44. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manton KG. Epidemiological, demographic, and social correlates of disability among the elderly. Milbank Quarterly. 1989;67(Suppl. 1):13–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss MP, Roubideaux YD, Jacobsen C, Buchwald D, Manson S. Functional disability and associated factors among older Zuni Indians. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology. 2004;19:1–12. doi: 10.1023/B:JCCG.0000015013.36716.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Management and Budget Standards for defining metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas. Federal Register. 2000;65:82228–82238. [Google Scholar]

- Onder G, Penninx BWJH, Lapuerta P, Fried LP, Ostir GV, Guralnik JM, et al. Change in physical performance over time in older woman: The Women's Health and Aging Study. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 2002;57A:M289–M293. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.5.m289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades DA. National health data and older American Indians and Alaska Natives. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2006;25:9S–26S. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute . SAS/STAT user's guide, version 8. Author; Cary, NC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau US. [August 14, 2006];Projections of the total resident population by 5-year age groups, race, and Hispanic origin with special age categories: Middle series 1999–2000; Middle series 2050–2070. 2005 from http://www.census.gov/population/projections/nation/summary/np-t4-a.txt.

- Waidmann TA, Liu K. Disability trends among elderly persons and implications for the future. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2000;55B:S298–S307. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.5.s298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]