Abstract

Several bacterial proteins are non-covalently anchored to the cell surface via an S-layer homology (SLH) domain. Previous studies have suggested that this cell surface display mechanism involves a non-covalent interaction between the SLH domain and peptidoglycan-associated polymers. Here we report the characterization of a two-gene operon, csaAB, for cell surface anchoring, in Bacillus anthracis. Its distal open reading frame (csaB) is required for the retention of SLH-containing proteins on the cell wall. Biochemical analysis of cell wall components showed that CsaB was involved in the addition of a pyruvyl group to a peptidoglycan-associated polysaccharide fraction, and that this modification was necessary for binding of the SLH domain. The csaAB operon is present in several bacterial species that synthesize SLH-containing proteins. This observation and the presence of pyruvate in the cell wall of the corresponding bacteria suggest that the mechanism described in this study is widespread among bacteria.

Keywords: Bacillus anthracis/cell wall/pyruvate/SLH motifs/surface targeting

Introduction

The bacterial cell wall is essentially a bag-shaped exoskeleton that ensures cell integrity and resists mechanical constraints (Weidel and Pelzer, 1964). This subcellular compartment plays a key role in the regulation of exchanges between the cell and its surrounding environment. In Gram-positive bacteria, the proteins immobilized on the cell surface are of particular interest, because they are often the outermost components of the cell envelope. They are involved in crucial physiological processes, such as cell wall assembly, and the breakdown of large non-transportable nutrient polymers into smaller subunits (Navarre and Schneewind, 1999). In pathogenic bacteria, cell surface proteins are involved in various steps of the infection process: adhesion and/or invasion of host cells, binding to host molecules (immunoglobulins, serum or extracellular matrix proteins) and protection against phagocytosis (for a review see Navarre and Schneewind, 1999). Major therapeutic and biotechnological applications may emerge from understanding of the mechanisms underlying cell surface protein display in bacteria (Cossart and Jonquières, 2000; for reviews see Stahl and Uhlen, 1997; Oggioni et al., 1999). This area of research has therefore moved to the forefront of bacterial cell surface biology during the last decade. Information on the domains that target a protein to the cell surface is increasing rapidly, but little is known about their wall ligand.

During evolution, Gram-positive bacteria have developed various strategies for displaying proteins at their surface. The best characterized mechanism is the covalent binding of LPXTG-carrying proteins to the peptidoglycan pentaglycine cross-bridge. This mechanism requires a C-terminal sorting signal with an LPXTG motif, a hydrophobic domain interacting with the cytoplasmic membrane, a charged tail preventing secretion and a sortase, which catalyzes the transpeptidation reaction (Schneewind et al., 1992; Mazmanian et al., 1999).

A few mechanisms for non-covalent binding to the cell wall have also been described. In Streptococcus pneumoniae, Clostridia and Streptococcus mutans, several proteins interact with choline residues in lipoteichoic or teichoic acids via C-terminal repeats (reviewed in Garcìa et al., 1998). Another non-covalent binding mechanism involves ‘GW modules’, found in the C-terminal part of various proteins (Baba and Schneewind, 1996). It was shown recently that lipoteichoic acids are the cell wall ligand of GW modules (Jonquières et al., 1999). Other non-covalent surface-targeting domains have been characterized in proteins from Gram-positive organisms (Buist, 1997), but not the cell wall polymers to which these domains bind.

Recently, much attention has focused on the cell wall-targeting mechanism of surface layer (S-layer) proteins. These proteins are found in many bacteria from several prokaryote divisions, including several pathogens (Messner and Sleytr, 1992). S-layer proteins self-assemble spontaneously as a bidimensional crystalline array covering the entire cell surface. The high-affinity, non-covalent binding of S-layer proteins to the cell wall and the abundance of these proteins (up to 15% of total protein) make the study of their targeting mechanism very interesting. The existence of a cell wall-targeting domain in surface proteins from Gram-positive bacteria was suggested initially by Fujino et al. (1993) and Lupas et al. (1994), based on sequence comparisons. These authors identified modules (or ‘motifs’) of ∼55 residues, containing 10–15 conserved amino acids, referred to as the SLH (S-layer homology) domain. To date, SLH domains, composed of one or three modules, have been found in >40 proteins from Gram-positive bacteria, and also from some Gram-negative bacteria (Engelhardt and Peters, 1998). In vitro interaction tests between the SLH domain and purified cell walls have shown that the SLH domain is responsible for cell wall targeting (Lemaire et al., 1995). Moreover, in vitro tests have shown that S-layer proteins lacking the SLH domain, obtained by limited protease digestion or genetic engineering, do not bind to cell walls (Olabarrìa et al., 1996; Ries et al., 1997). Furthermore, recombinant strains expressing translational fusions between the SLH domain and heterologous antigens display the chimeric proteins at the vegetative cell surface. Thus, the SLH domain is sufficient to target proteins to the cell wall (Mesnage et al., 1999a,b).

The amino acid composition of the SLH domain is typical of carbohydrate-binding proteins such as lectins (Jarosch et al., 2000). It has been shown that the SLH domain does not directly bind peptidoglycan, but to wall-associated polymers (Sára et al., 1996; Ries et al., 1997; Ilk et al., 1999; Mesnage et al., 1999a). Indeed, the removal of polysaccharides (PSs) covalently bound to the peptidoglycan abolishes the binding of the SLH domain but leaves the structure and chemical composition of the peptidoglycan intact (Ries et al., 1997).

We used Bacillus anthracis, the etiological agent of anthrax, as a model system to elucidate the molecular basis of the interaction between the SLH domain and its cell wall PS ligand. Bacillus anthracis synthesizes two S-layer proteins: EA1 (extractable antigen 1) and Sap (surface array protein). Both proteins have been characterized in detail and both possess an SLH domain (Etienne-Toumelin et al., 1995; Mesnage et al., 1997).

Here we describe the molecular characterization of an operon, csaAB, the expression of which is essential for the SLH-mediated targeting of surface proteins to the cell wall. We found that the distal gene was involved in the addition of a pyruvyl group to a PS fraction and obtained direct evidence that the pyruvylated PS fraction was sufficient to bind the SLH domain. Finally, we propose that the SLH-mediated cell wall sorting of surface proteins described in this study is a widespread mechanism in bacteria.

Results

Identification and molecular characterization of a locus involved in cell wall-associated polymer biosynthesis

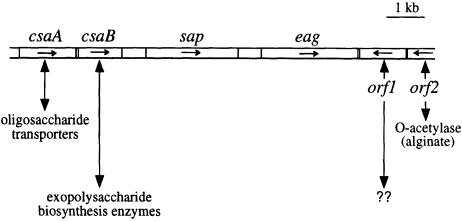

Several studies have shown that bacterial genes with related functions can be clustered on the chromosome. This is true in B.anthracis: the two S-layer components, Sap and EA1, are encoded by genes clustered on the chromosome (sap and eag, respectively; Mesnage et al., 1997). Analysis of the genes surrounding sap and eag revealed that the proteins encoded by the flanking genes were similar to proteins involved in cell wall metabolism (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram of the organization of the chromosomal region containing the B.anthracis S-layer genes sap and eag. Putative functions encoded by the ORFs flanking the S-layer genes, based on sequence comparison with protein databases, are shown.

Cloning and sequencing of the DNA region upstream of sap led to the identification of two genes, csaA and csaB (for cell surface anchoring). Northern blot experiments showed that they were organized as an operon, transcribed as a 2.9 kb mRNA (not shown). Southern blotting experiments and genome sequence analysis suggested that csaA and csaB are each present as a single copy on the chromosome (data not shown). The amino acid sequences deduced from the open reading frames (ORFs) corresponded to 506 and 367 residue proteins for CsaA and CsaB, respectively.

Sequence comparisons with proteins from databases (BLASTP version 2.0.10; Altschul et al., 1997) revealed that CsaA is very similar to Bacillus subtilis paralogs of SpoVB (with a Poisson probability, or ‘E value’, of 10–49, 10–44 and 10–42) and SpoVB itself (E value = 10–28); SpoVB is involved in the acquisition of heat resistance by spores (Popham and Stragier, 1991). CsaA is also similar to several oligosaccharide transporters (or putative transporters) from Gram-negative bacteria. The hydropathy profile of CsaA strongly suggests that it is an integral membrane protein with at least 13 transmembrane segments of 17–23 residues each. As for CsaB, it is similar to WcaK and AmsJ (E values of 10–8 and 5 × 10–4, respectively), which are involved in the biosynthesis of colanic acid in Escherichia coli and of amylovoran in Erwinia amylovora, respectively (Bugert and Geider, 1995; Stevenson et al., 1996). Unlike csaB, wcaK and amsJ belong to large operons (23 kbp for colanic acid biosynthesis and 16 kbp for amylovoran biosynthesis). Colanic acid and amylovoran are PSs containing pyruvate. No genes within these operons have been shown to be involved in the addition of pyruvate. As wcaK is the only unassigned gene of its operon (Stevenson et al., 1996), it was thought likely that WcaK and, by analogy, AmsJ and CsaB, are pyruvyl-transferases involved in peptidoglycan-associated polymer biosynthesis.

Previous studies showed that a polymer is involved in the anchoring mechanism of B.anthracis S-layer proteins (Mesnage et al., 1999a). We therefore investigated the role of the csaAB operon in the biosynthesis of wall-associated polymers in B.anthracis.

Abolition of SLH-mediated surface anchoring in the ΔcsaB mutant

To investigate the function of CsaA and CsaB, we constructed three mutants of the csaAB operon: a non polar csaA mutant, a csaB mutant and the double mutant deleted of both the csaA and csaB genes (they were termed ΔcsaA, ΔcsaB and ΔcsaAΔcsaB, respectively; see Materials and methods and Table IV).

Table IV. Bacterial strainsa, plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Genotype or descriptionb | Source/construction | |

|---|---|---|

| E.coli | ||

| TG1 | supE hsdΔ5 thi Δ (lac-proAB) F′[traD36 proAB+ lacIq lacZΔM15] | Sambrook et al. (1989) |

| JM83 (pRK24) | ara Δ (lac-proAB) strA φ80 lacZΔM15, Tra+, Mob+ | Trieu-Cuot et al. (1987) |

| B.anthracis | ||

| 9131 | plasmidless Sterne strain derivative | Etienne-Toumelin et al. (1995) |

| SM94 | 9131 ΔcsaA (pAMT101) | this work |

| SM95 | 9131 ΔcsaB (pAMT202) | this work |

| SM96 | 9131 ΔcsaA ΔcsaB (pAMT303) | this work |

| Plasmid | ||

| pAT113 | conjugative suicide plasmid used for gene inactivation in B.anthracis | Trieu-Cuot et al. (1991) |

| pATH | pAT113 lacking the HindIII site | this work |

| pNEB | cloning vector | New England Laboratories |

| pUC19 | cloning vector | Yannisch-Perron et al. (1985) |

| pUC1318spc | pUC1318 carrying the spc spectinomycin resistance gene (SpcR) | Murphy (1985) |

| pSPCH+2 | pUC19 carrying a non-polar mutagenic SpcR cassette | this work |

| pSPCH+1, +3 | pUC19 carrying non-polar mutagenic SpcR cassettes | this work |

| pAMT1 | csaA csaB operon in pAT113 | this work |

| pAMT10 | csaA csaB operon in pUC19 | this work |

| pAMT100 | pUC19 carrying the inactivated csaA gene | this work |

| pAMT101 | pAT113 carrying the inactivated csaA gene | this work |

| pAMT202 | pATH carrying the inactivated csaB gene | this work |

| pAMT303 | pAT113 carrying the inactivated csaA and csaB genes | this work |

| pEAI20 | pUC19 carrying the entire csaB gene and the 5′ end of sap | Etienne-Toumelin et al. (1995) |

| pEAI26 | pEAI20 carrying the 3′ end of csaB | this work |

| pEAI260 | pATH harboring the insert of pEAI26 | this work |

| pEAI261 | pEAI260 carrying an internal portion of csaB and the 3′ end of sap | this work |

| pEAI30 | pUC19 carrying the 3′ end of sap | Etienne-Toumelin et al. (1995) |

| pEAI32 | pEAI30 deleted of a fragment within the sap open reading frame | this work |

| pSAL201 | pUC19 carrying the 3′ end of eag | Mesnage et al. (1997) |

| pSAL300 | pEAI260 carrying an internal fragment of csaB and the 3′ end of eag | this work |

| Oligonucleotide | ||

| ED17 | ATC AAC TTT TTT GTC ATG CAA C | |

| Pst-Slh | AAA CTG CAG ACT AAC TCT TAC AAA AAA GTA ATC | |

| ED9 | GGA GAA GAA GCT CAT AGC TTC CG | |

| Am-Spcc | GGA TGT TGA CTG ACT AAC TAG GAG GAA ATA ATA AAT GAG CAA TTT GAT TAA CGG AAA AAT | |

| SPC-H+2c | TTT TAG TTG ACT TCA TTT ATA TTT TCC TCC TTA GCC TAA TTG AGA GAA GTT TCT AT | |

| SPC-H+1c | TTT TAG TTG ACT CAT TTA TAT TTT CCT CCT TAG CCT AAT TGA GAG AAG TTT CTA T | |

| SPC-H+3c | TTT TAG TTG ACC ATT TAT ATT TTC CTC CTT AGC CTA ATT GAG AGA AGT TTC TAT | |

| ORF1 | AAA GAA TTC AGC ATG TTG TAA ACA CTC C | |

| ORF2 | CAG ACA GAA AAA CGC GTC AGA ATT ACA T | |

aAll other strains used in this study are described in Table I or at www.sanger.ac.uk or at www.tigr.org.

bFor B.anthracis strains, the plasmids in brackets are those used for allelic exchange between the chromosomal locus and the inactivated allele.

cThe underlined nucleotides correspond to HincII sites.

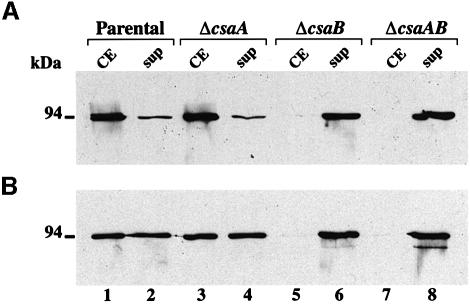

None of these mutants grew less well than the parental strain in rich medium. The involvement of the csaAB operon in the anchoring of B.anthracis S-layer proteins was assessed (Figure 2). We investigated the subcellular location of the surface-exposed EA1 and Sap proteins in each mutant by western blot analyses using specific anti-EA1 and anti-Sap antibodies (Figure 2A and B, respectively). The total amount of EA1 and Sap produced was similar in all mutants compared with the parental strain (Figure 2A and B, lanes 1 and 2 versus lanes 3 and 4, 5 and 6 and 7 and 8). As previously described, in the parental strain, EA1 was associated mainly with cells; Sap was cell associated and was also abundant in culture supernatants (Figure 2A and B, lanes 1 and 2). The results obtained with the ΔcsaA mutant were indistinguishable from those obtained with the parental strain (Figure 2A and B, lanes 1 and 2 versus 3 and 4). The ΔcsaB mutant gave results similar to those of the ΔcsaAΔcsaB mutant. In both strains, neither of the S-layer proteins was associated with the cell fraction (Figure 2A and B, lane 1 versus lanes 5 and 7) but, instead, both were found exclusively in culture supernatants (Figure 2A and B, lanes 6 and 8). Thus, CsaB was required for the cell surface localization of EA1 and Sap, whereas CsaA was not.

Fig. 2. CsaB is necessary for the cell wall anchoring of B.anthracis S-layer proteins. (A) EA1 and (B) Sap were detected in crude extracts (CE, lanes 1, 3, 5 and 7) and TCA-precipitated supernatants (Sup, lanes 2, 4, 6 and 8) from parental (lanes 1 and 2), non-polar ΔcsaA (lanes 3 and 4), ΔcsaB (lanes 5 and 6) and ΔcsaAΔcsaB (lanes 7 and 8) strains by western blotting, using specific polyclonal sera.

The implication of CsaB in the anchoring of non-S-layer SLH-containing proteins was also investigated using an anti-SLH polyclonal serum. Contrary to the wild-type situation, no SLH-harboring proteins could be detected at the cell surface fraction of the ΔcsaB mutant (data not shown). Thus, CsaB is necessary for the SLH-mediated anchoring of non-S-layer proteins to the cell wall.

The role of the CsaB protein in autolysis

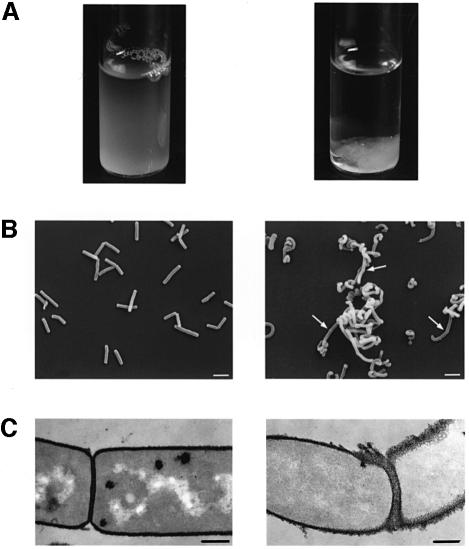

We investigated the consequences of the absence of SLH protein anchoring by analyzing the morphology of the mutants. The non-polar ΔcsaA mutant was indistinguishable from the parental strain; the ΔcsaB and ΔcsaAΔcsaB mutants were indistinguishable from each other. Indeed, the inactivation of csaB led to aberrant morphogenesis. On agar plates, ΔcsaB colonies were very small and convex, rather than large and flat (data not shown). In liquid medium, the mutant grew as clusters of cells, which rapidly sedimented when shaking stopped (Figure 3A). Scanning electron microscopy showed that csaB inactivation was accompanied by major changes in morphogenesis: bacilli formed long chains of twisted cells (Figure 3B). However, they appeared to be septate, suggesting that the ΔcsaB mutant was impaired in cell separation rather than in cell division stricto sensu (see arrows, Figure 3B, right panel).

Fig. 3. SLH-anchoring deficient mutants show aberrant morphology. (A) Sedimentation profile of liquid-grown parental (left panel) and ΔcsaB (right panel) strains. (B) Scanning electron microscopy of parental bacilli (left panel) and long twisted, septate (see arrows) filaments formed by the ΔcsaB mutant (right panel). (C) Thin sections showed that more of cell wall material accumulated in the ΔcsaB mutant (right panel) than in the parental strain (left panel), suggesting an autolysis defect. Bars represent 2.5 and 0.35 µm in (A) and (B), respectively.

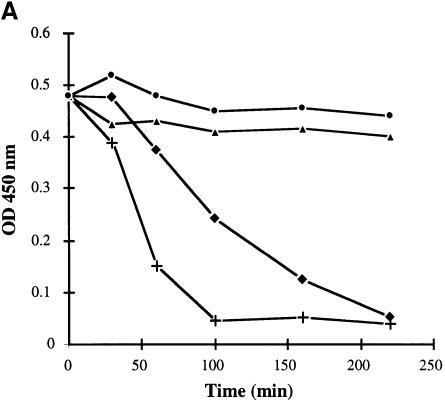

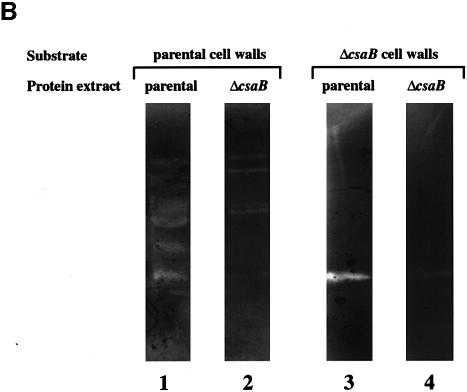

We characterized the morphological changes in the ΔcsaB mutant further by comparing thin sections of parental and ΔcsaB cells (Figure 3C). We found that wall material accumulated on mutant cells. To explain this anomaly, we analyzed the autolysis rate of each strain. With the parental strain, complete autolysis was achieved within 100 min. Although the ΔcsaA mutant was morphologicaly similar to the parental strain (see above), its autolysis rate was slightly lower (Figure 4A). The ΔcsaB and ΔcsaAΔcsaB mutants were not subject to autolysis (Figure 4A). We studied this process further by zymogram analysis. The autolytic profiles of parental and ΔcsaA cells were similar when assayed on cell walls extracted from the parental strain: at least seven bands with autolytic activity were detected (Figure 4B, lane 1, and not shown). The profiles of the ΔcsaB and ΔcsaAΔcsaB mutants showed significantly lower levels of autolytic activity for several bands (Figure 4B, lane 2, and data not shown). We also assayed autolytic profiles on mutant cell walls (Figure 4B, lanes 3 and 4). Very few bands with autolytic activity were observed, and no differences were found between parental and mutant extracts. Thus, the inactivation of csaB was accompanied by a loss of several cell-associated autolytic activities and of a cell wall modification required for the activity of many autolysins.

Fig. 4. CsaB function is required for autolysis. (A) The autolytic kinetics of parental (+), non-polar ΔcsaA (diamonds), ΔcsaB (triangles) and ΔcsaAΔcsaB (circles) strains were compared. (B) The autolytic profiles of crude extracts from parental (lanes 1 and 3) and ΔcsaB (lanes 2 and 4) strains were analyzed by zymograms, with either parental (lanes 1 and 2) or ΔcsaB (lanes 3 and 4) cell walls as substrate.

Cell wall PS content analysis for parental and mutant strains of B.anthracis

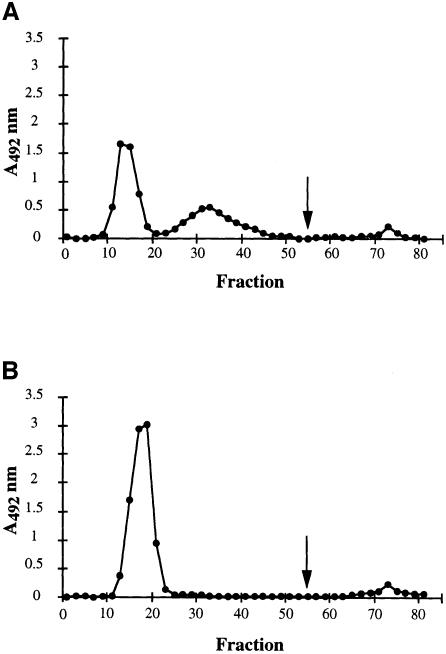

The results described above suggested that CsaB was involved in cell wall metabolism. We investigated the specific defect of the ΔcsaB mutant by studying the composition of the various cell wall components of B.anthracis. This bacterium does not synthesize teichoic acids, the only wall-associated polymer described is a PS (Molnár and Prágai, 1971; Ekwunife et al., 1991). We compared the peptidoglycan structure of the various strains by reverse-phase HPLC (data not shown). No significant difference in wall muropeptide profile was found, suggesting that CsaA and CsaB are not involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. We then extracted the wall-associated polymers with fluorhydric acid (HF). As previously described, we extracted a PS fraction of homogeneous size, with a molecular mass of ∼12 kDa (Ekwunife et al., 1991; data not shown). Gas chromatography (GC) confirmed the presence of Gal, GlcNAc and ManNAc, but in a molar ratio slightly different from that previously described (10:3:1 instead of 3:2:1), probably due to differences in the hydrolysis conditions used. No difference was observed between the total PS extracts from the parental strain and those from any of the mutants, either in molecular mass or in monosaccharide composition (not shown). The wall-associated PSs were purified by ion-exchange chromatography (Figure 5). Three distinct fractions were separated for the parental PS extract (Figure 5A). Fraction I did not interact with the resin and was eluted in the void volume, suggesting that it was not charged. Fraction II interacted slightly with the resin and therefore probably displayed substitution by negatively charged groups. Finally, a third fraction (III) bound to the resin and was eluted at high salt concentration.

Fig. 5. Contribution of CsaB to the biosynthesis of the peptidoglycan-associated PS fraction. The profiles from ion-exchange chromatography (DEAE–Sephadex A50 column) of parental (A) and ΔcsaB (B). Total PS extracts are presented. The arrow indicates the addition of 500 mM NaCl to elute bound material.

The elution profile of PS from the ΔcsaA mutant was similar to that of the parental strain (not shown). In the ΔcsaB mutant profile, peak I was larger than that for the parental and ΔcsaA mutant strains, and peak II was absent (Figure 5B). Peak III was similar to that in the parental and ΔcsaA mutant strain. Therefore, CsaB does not seem to be involved in the biosynthesis of fraction III. As expected, the elution profile of the ΔcsaAΔcsaB mutant was identical to that of the ΔcsaB mutant (not shown). The monosaccharide composition of each PS fraction was determined and found to be identical and to have the same molar ratio as the total extract.

Sequence analysis suggested that CsaB may be involved in a pyruvylation pathway. We therefore tested each fraction for pyruvate using an enzymatic assay. Fraction I did not contain significant amounts of pyruvate (0.05 µg/mg PS), whereas fractions II and III contained ∼4.5 and 2.2 µg of pyruvate/mg PS, respectively. Fraction III was so small that its contribution to the total pyruvate content of cell walls is probably minor. Fraction I was devoid of pyruvate and was found in larger amounts in ΔcsaB mutants than in the parental strain. Fraction II may therefore be identical to fraction I, except for the addition of pyruvate by CsaB. We therefore carried out a comparative NMR analysis of fractions I and II.

1H and 13C NMR analysis of the parental-specific and mutant PS fractions

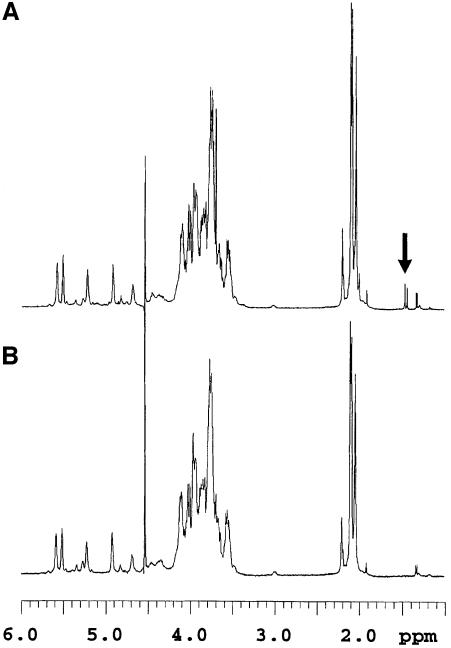

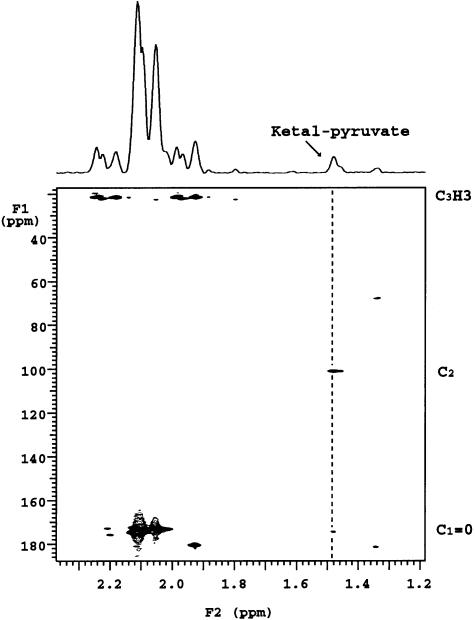

The proton spectra of fractions I and II of the PS indicated that the two compounds were very similar in structure (Figure 6). Nevertheless, fraction II had additional signals at 1.49 and 1.47 p.p.m. and small broad signals in the anomeric region. The two upfield additional signals originate from protons that are not coupled to any other protons in the molecule. Their linewidth was similar to that of the other protons, suggesting that they are attached to the molecule and do not belong to any small component. The gradient heteronuclear single bond proton carbon-correlated experiment (gHSQC) showed that these protons were attached to a carbon resonating at 24.79 p.p.m. The gradient heteronuclear multiple bond proton carbon-correlated experiment (gHMBC) made it possible to correlate these signals with two quaternary carbon signals resonating at 101.42 and 174.33 p.p.m. (Figure 7). The signal resonating at 174.33 p.p.m. corresponds to the carboxylic carbon, while that at 101.42 p.p.m. is typical of a ketal carbon, as already observed in pyruvic acid-containing PSs (Kojima et al., 1988; Ilk et al., 1999). These obervations indicate the presence of a ketal-linked pyruvate group in fraction II that is not present in fraction I. Indeed, the equivalent carbon in pyruvic acid resonates at 205 p.p.m., while the methyl group resonates at 2.4 p.p.m. (data not shown). Moreover, the chemical shift of this ketal carbon is in favor of a pyruvic acid present in a six-membered ketal ring (Kojima et al., 1988). The signal intensity of the pyruvate methyl groups is ∼2.5% that of the combined neighboring N-acetyl groups in the 2.02–2.20 p.p.m. region.

Fig. 6. A pyruvate signal present in the fraction II (the parental strain-specific PS fraction) 1H NMR spectrum (A) is absent from that of fraction I (fraction common to both PS) (B). Spectra were recorded at 500 MHz and 50°C. The pyruvate signals are indicated with an arrow.

Fig. 7. Expansion of the 2D 13C-1H gHBMC spectrum of the parental PS fraction II that was absent from the ΔcsaB mutant, recorded with a 60 ms delay. The 13C links with the pyruvate proton are indicated with a dashed line; C2 corresponds to the ketal carbon [C3H3–C2(O2)– C1OOH].

The results of GC and NMR and enzymatic pyruvate assay indicated that all fractions present the same monosaccharide composition and sequence. The only difference is the presence of ketal-linked pyruvate in the parental fraction II PS and its absence in parental fraction I PS and in ΔcsaB mutant PS. These results indicated that CsaB is involved in the addition of pyruvate on the PS.

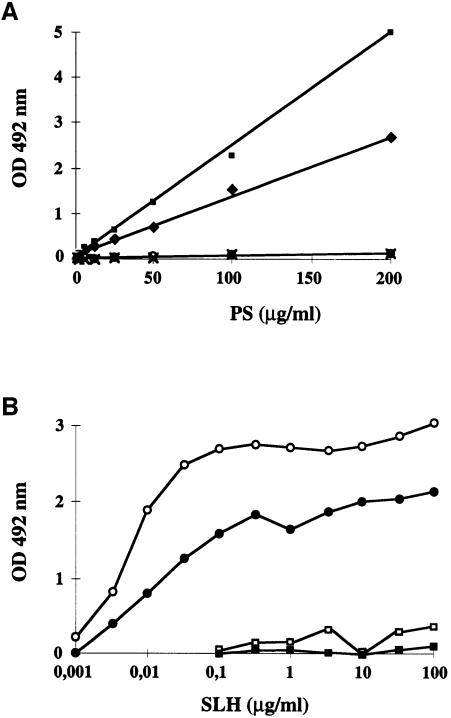

Identification of the pyruvylated PS fraction as the ligand of the SLH domain

Each total PS fraction of B.anthracis was tested in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for binding to the SLH domain of EA1 purified from E.coli (Figure 8A). SLH binding was only observed in csaB+ strains. Only fraction II bound the SLH domains of EA1 and Sap (Figure 8B). Furthermore, this binding occurs in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 8B). These results therefore provide direct evidence that a purified PS fraction is sufficient to bind the SLH domain in vitro. They also indicate that the PS fraction must be pyruvylated to bind the SLH domain. Thus, the absence of fraction II in the ΔcsaB mutant may account for the abolition of SLH-containing protein anchoring to the cell walls.

Fig. 8. In vitro binding of SLH domains to B.anthracis wall-associated PS. (A) The binding capacity of total PS from various B.anthracis strains [parental (diamonds), non-polar ΔcsaA (squares), ΔcsaB (circles) and ΔcsaAΔcsaB (crosses)] to EA1 SLH was assayed. (B) Analysis of binding dose–response of EA1 (open symbols) and Sap (filled symbols) SLH domain to purified PS fractions I (squares) and II (circles).

Analysis of the SLH-mediated anchoring mechanism in bacteria

We investigated the link between CsaB and SLH-mediated anchoring by studying several strains known to synthesize surface proteins containing an SLH domain.

We studied closely related species from the Bacillus cereus group, which includes B.anthracis, B.cereus and B.thuringiensis (Helgason et al., 2000). We carried out Southern blot analysis using csaB and the fragment encoding the SLH domain (slh) independently as probes (Table I). Seven of the 12 strains tested contained slh-like sequences, showing that SLH sequences are present in other members of the B.cereus group (Table I). All slh-positive strains were csaB positive, whereas all slh-negative strains were csaB negative (Table I). We then carried out PCR using a primer located within csaB and a convergent primer, localized in the slh of sap. A positive signal was obtained, of the same size as that in B.anthracis, in all of the slh+ csaB+ strains and only in these strains (Table I). Thus, the csaB homolog is always immediately upstream of an slh-like sequence in the bacteria of the B.cereus group. We then sought csaB homologs outside the B.cereus group, and showed that Bacillus licheniformis NM105 harbors both slh and csaB homologs, which are also clustered on the chromosome (Table I).

Table I. Southern and PCR detection of slh- and csaB-like sequences in various Bacillaceae.

| Strains | Southern detection |

PCR | Source or reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| slh | CsaB | |||

| B.anthracisa | ||||

| 9131 | + | + | + | Etienne-Toumelin et al. (1995) |

| B.cereusa | ||||

| ATCC14579 | – | – | – | A.-B.Kolstø |

| II4 | – | – | – | Patra et al. (1998) |

| PC1 | – | – | – | Patra et al. (1998) |

| S8553 | + | + | + | Patra et al. (1998) |

| AH812 | + | + | + | Kotiranta et al. (1998) |

| AH819 | + | + | + | Kotiranta et al. (1998) |

| B.thuringiensisa | ||||

| KTO | – | – | – | D.Lereclus |

| NRRL 4045 | + | + | + | T.J.Beveridge |

| 3BS | + | + | + | Ramisse et al. (1999) |

| Ba-IB | + | + | + | Ramisse et al. (1999) |

| 9727 | + | + | + | Hernandez et al. (1999) |

| B.licheniformis | ||||

| NM105 | + | + | + | Tang et al. (1989) |

aMembers of the B.cereus group.

+, positive detection; –, not detected.

As expected from the low sequence identity, attempts to detect slh and csaB homologs in other Bacillaceae producing surface proteins with an SLH domain (Bacillus sphaericus and Clostridium thermocellum; Bowditch et al., 1989; Lemaire et al., 1995) failed. This limitation of Southern blots and PCR for detection, due to DNA sequence differences between homologs from different species, led us to conclude that computer analysis was the best way to investigate the presence of slh and csaB homologs in other bacteria. We therefore searched databases of sequences from other bacterial genomes. We analyzed four distant bacteria for which complete genome sequences are available or being produced, and that are known to synthesize SLH-containing proteins: Deinococcus radiodurans, Synechocystis PCC6803, Thermotoga maritima and Thermus thermophilus. In these bacteria, the number of ORFs encoding proteins with an SLH domain differs: two in T.maritima, three in D.radiodurans and seven in Synechocystis PCC6803 (Engelhardt and Peters, 1998). All have a CsaB ortholog. The genomes of the other bacteria tested contained neither slh-like sequences nor CsaB orthologs (Table II and not shown).

Table II. Co-existence of slh and csaB homologs in bacterial genomes.

| Strainsa | Homologs of |

|

|---|---|---|

| slh | csaB | |

| Bacillus subtilis | – | – |

| Clostridium difficileb | – | – |

| Deinococcus radiodurans | + | + |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | – | – |

| Staphylococcus aureusb | – | – |

| Streptococcus pneumoniaeb | – | – |

| Synechocystis PCC6803 | + | + |

| Thermotoga maritima | + | + |

| Thermus thermophilusb | + | + |

aSee description at www.tigr.org/tdb/mdb/ or at www.sanger.ac.uk.

bUnfinished genomes.

+, E value <10–10.

Finally, we carried out further biochemical analysis of the pyruvate in the cell walls of some strains (Table III). Significant amounts of pyruvate, similar to those in B.anthracis (∼2 µg of pyruvate/mg cell wall), were present in the cell walls of all slh+ csaB+ strains and in the cell wall of C.thermocellum, which is known to synthesize proteins with SLH domains. The amount of pyruvate detected in slh– csaB– strains was similar to that in B.anthracis ΔcsaB mutant cells and in B.subtilis, a negative control (≤0.1 µg/mg cell wall).

Table III. Pyruvate content of various bacterial cell walls.

| Strains | Wall-associated pyruvatea |

|---|---|

| B.anthracisb | |

| 9131 | 2.0 |

| ΔcsaB | 0.05 |

| B.cereusb | |

| II4 | 0.1 |

| PC1 | 0.1 |

| S8553 | 2.0 |

| B.licheniformis | |

| NM105 | 1.5 |

| B.subtilis | |

| 168 | 0.1 |

| B.thuringiensisb | |

| NRRL 4045 | 4.2 |

| 3BS | 1.9 |

| Ba-IB | 1.8 |

| 9727 | 2.5 |

| C.thermocellum | |

| NCIMB 10682 | 1.7 |

| T.maritima | |

| MSB8 | 1.9 |

aValues are given in µg of pyruvate per mg of total cell wall.

bMembers of the B.cereus group.

These observations support our initial hypothesis that the PS pyruvylation mediated by CsaB is required specifically for the retention of the SLH domain in the cell wall. In addition, this anchoring mechanism seems to be widely conserved among prokaryotes.

Discussion

We investigated the wall ligand for B.anthracis SLH domain-containing proteins. We studied the composition of the PS to which the SLH domain binds non-covalently, and showed that pyruvylation is required for binding. We also characterized an operon required for the transfer of pyruvate to the SLH domain ligand. Finally, we showed that this non-covalent anchoring mechanism is widespread among prokaryotes, suggesting that it has been conserved throughout evolution.

SLH-mediated cell surface targeting in B.anthracis

The B.anthracis genome sequencing project, which is nearing completion, has revealed the existence of several SLH-containing proteins. Three are found on the virulence plasmids (two on pXO1, one on pXO2), and at least 15 are located on the chromosome (Okinaka et al., 1999; see DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession Nos AF065404 and AF188935, and www.tigr.org). Therefore, SLH-mediated anchoring in B.anthracis is not restricted to the S-layer proteins and is widely used by this bacterium. Three of the 18 proteins identified are very similar to peptidoglycan hydrolases (N-acetyl muramoyl-l-alanine amidases), suggesting that proteins containing an SLH domain are important in cell wall metabolism.

Identification of pyruvylated PS as a ligand of the SLH domain

We investigated the cell wall composition of B.anthracis. Our results confirmed that the peptidoglycan-associated PSs are homogeneous in size (Ekwunife et al., 1991). We identified three distinct fractions in the PS extract by ion-exchange chromatography.

Two of the B.anthracis PS fractions (fractions II and III) contained significant amounts of pyruvate, whereas one fraction (fraction I) contained no pyruvate. The presence of pyruvate may account for the negative charge of fraction II, and, at least partly, for that of fraction III. The non-pyruvate acidic groups from fraction III have not yet been identified.

Pyruvate is bound to the PS by an acid-sensitive bond, as increasing the time of HF treatment for PS extraction from cell walls resulted in a decrease in the recovery of fraction II, with a proportional increase in that of fraction I (not shown). The release of pyruvate from PS upon HF treatment has also been described in Bacillus polymyxa AHU 1385 (Kojima et al., 1988). This also accounts for the pyruvate concentration in fraction II being similar to that in total cell walls, although total PS makes up only one-tenth of the total cell wall. In the parental PS, fraction I is thus probably a hydrolysis product of fraction II.

In vitro interaction tests indicated that the presence of pyruvate within the PS is necessary and sufficient to bind the SLH domain. The addition of exogenous pyruvate to cell wall extracts does not inhibit binding of the SLH domain. It is therefore tempting to assume that pyruvylated monosaccharides are the ligand of the SLH domain, rather than pyruvate itself. Further analysis is required to characterize the monosaccharide(s) to which pyruvate is bound. The determination of the structure of fraction I and fraction II of the PS currently is in progress.

Functional contribution of the csaAB operon to the wall-anchoring mechanism of SLH-containing proteins

The absence of fraction II and the larger amount of fraction I in the PS extract from the ΔcsaB mutant suggest that CsaB is involved in a pyruvylation pathway of B.anthracis PS. Fraction III levels were unaffected in the PS extract from the ΔcsaB mutant, showing that the addition of pyruvate to this fraction is unrelated to CsaB. Thus, CsaB-independent pyruvylation pathways also exist in B.anthracis.

Sequence analysis revealed that CsaA is highly hydrophobic and has several putative membrane domains, so it may function as an oligosaccharide transporter. No change in phenotype with regard to cell wall anchoring was observed in the ΔcsaA mutant. This may be due to the existence of several proteins similar to CsaA in B.anthracis (see www.tigr.org). Therefore, we cannot exclude functional redundancy. It would be interesting to know whether CsaA can transport any oligosaccharide from the biosynthetic pathway of the SLH domain ligand. The hydrophobic segment in the CsaB protein may also be of functional relevance, and it is tempting to speculate that CsaA and CsaB are part of the membrane-associated biosynthetic machinery.

Role of pyruvylated PS in cell wall metabolism

The pleiotropic phenotype of the ΔcsaB mutant is similar to that of S.pneumoniae mutants affected in the incorporation of choline into teichoic and lipoteichoic acids. These mutants are also morphologically abnormal, due to a defect in autolysis (Séverin et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 1999). Cell wall-associated polymers are essential for autolysis, which is a crucial physiological process. This may explain why, to date, no viable mutant totally devoid of wall-associated polymers has been isolated (Pooley and Karamata, 1994). The viability of the B.anthracis ΔcsaB mutant may be due to its ability to synthesize an anionic polymer (fraction III) and to the presence of some autolytic activity. Indeed, we showed that some autolysins do not require the presence of the PS fraction II to be active. Finally, our data suggest that in B.anthracis and S.pneumoniae, the autolysis deficiency is due to a defect in the cell wall anchoring of autolysins rather than a change in the electrochemical gradient across the plasma membrane, also known to control autolysis (Joliffe et al., 1981).

Zymogram assays using parental protein extract and cell walls from the ΔcsaB mutant as substrate revealed that close contact beween the autolysins and cell walls is not sufficient for peptidoglycan hydrolysis. The binding of autolysins to wall-associated polymers via their SLH domain is necessary. Thus, autolysins must be activated, as described in S.pneumoniae. The activation step probably occurs at the same time as cell wall binding.

Occurrence of the SLH–CsaB cell surface-anchoring mechanism in prokaryotes

We analyzed several bacteria that synthesize proteins with an SLH domain. We found that all had a CsaB ortholog and had pyruvate in their cell wall, at a concentration similar to that in B.anthracis. This was true for bacteria within the B.cereus group, for a more distant Bacillus (B.licheniformis) and another very distantly related Gram-positive bacterium (T.maritima). Bacillus sphaericus also contains pyruvate bound to teichuronic acid, a cell wall polymer (Ilk et al., 1999). It is unknown whether this bacterium has a csaB homolog, but the presence of pyruvate in the cell walls of this bacterium, which synthesizes S-layer proteins with SLH domains, is consistent with our anchoring model.

If no SLH domains were found, no csaB ortholog or pyruvate in the cell wall were detected either. However, some strains within the B.cereus group, independently of the presence of csaB, had the same monosaccharide composition as B.anthracis, with the same molar ratio of components. This is consistent with the idea that CsaB is involved specifically in SLH-mediated anchoring, rather than in a PS biosynthesis step common to various closely related organisms.

In the strains from the B.cereus group, csaB- and slh-like sequences, if present, were clustered on the chromosome. In the phylogenetically distant bacteria D.radiodurans, Synechocystis PCC6803 and T.maritima, which possess slh- and csaB-like sequences, these sequences are not genetically linked. As these bacteria are thought to be closer to the common ancestor than are the Bacillaceae (Gupta, 1998), this suggests that a selection pressure exists, which led to the co-evolution of CsaB and the SLH domains.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, cloning vectors and culture conditions

The E.coli and B.anthracis strains and cloning vectors used in this study are listed in Table IV. pATH was obtained by digesting pAT113 with HindIII, filling the ends and religating, thereby removing the HindIII site. The culture conditions for B.anthracis and E.coli are described elsewhere (Etienne-Toumelin et al., 1995).

DNA manipulation and sequencing

All DNA manipulations were as described by Sambrook et al. (1989) or as previously described (Mesnage et al., 1999a). The sequence data have been submitted to the DDBJ/EMBLGenBank database under accession No. AJ249463.

Identification of the csaAB operon

The sequencing of pEAI20 (Etienne-Toumelin et al., 1995) led to identification of the 3′ end of csaB. The rest of the csaAB locus was sequenced after two successive inverse PCR amplifications. Chromosomal DNA was first digested with ClaI, and amplification was carried out with the divergent oligonucleotides ED17 and Pst-SLH. It was then digested with EcoRI, and PCR amplification was carried out with oligonucleotides ED17 and ED9. Sequence analysis of the 3.7 kbp upstream of the sap translation initiation codon identified two contiguous ORFs corresponding to the csaA and csaB genes, both in the same orientation as sap and eag.

Plasmid constructions for gene inactivations

The characteristics of the plasmids are described in Table IV.

As csaA is the first gene of an operon, we first had to develop a non-polar mutagenesis cassette. The spectinomycin resistance gene (spc) from pUC1318Spc was amplified by PCR using Am-Spc and SPC-H+2. The 0.85 kbp DNA fragment amplified was cloned into the HincII site of pNEB193, giving rise to pSPC-H+2. The selectable cassette from pSPC-H+2 contains no promoter sequence. The spc gene is preceded by translation stop codons in all three reading frames and is immediately followed by a consensus ribosome-binding site and a start codon. Two other cassettes (pSPC-H+1 and pSPC-H+3) were also constructed using the same strategy, with Spc-H+1 and Spc-H+3, respectively, to allow 3′ fusion in different reading frames. These plasmids are available upon request.

The complete csaAB operon was amplified from B.anthracis 9131 chromosomal DNA using the oligonucleotides ORF1 and ORF2. The 3.5 kbp product was inserted into pAT113 digested with SmaI, giving rise to pAMT1. Its insert was inserted as a KpnI–PstI fragment into pUC19. The resulting plasmid, pAMT10, was digested with BstXI and SnaBI and the 1.1 kbp csaA internal fragment was replaced by the 0.85 kbp non-polar resistance spectinomycin cassette from Spc-H+2, cut with HincII and fused to the last codon of the csaA ORF, giving rise to pAMT100. To construct pAMT101, the 3.2 kbp EcoRI fragment of pAMT100 was inserted into pAT113.

To obtain pAMT202 pEAI20 (Etienne-Toumelin et al., 1995) was digested with EcoRI and self-ligated, giving rise to pEAI26, retaining 1.15 kbp including 0.7 kbp upstream from the 5′ end of sap. The insert of pEAI26 was inserted into pATH between the EcoRI and PstI sites, giving rise to pEAI260. In parallel, pEAI30 (Etienne-Toumelin et al., 1995) was digested with HindIII and self-ligated. The resulting plasmid, pEAI32, harbors a 1.75 kbp fragment overlapping the 3′ end of sap.

pAMT202 was constructed by replacing the BclI–HindIII fragment of pEAI260 by a HindIII–BamHI fragment containing the spectinomycin resistance cassette.

pAMT303 was obtained by replacing the 1.4 kb ClaI blunt-ended SpeI fragment by a HincII–XbaI fragment containing the spectinomycin resistance cassette.

Construction of recombinant strains

All mutant strains were isogenic to 9131. Recombinant plasmids were transferred from E.coli to B.anthracis by heterogramic conjugation procedure (Trieu-Cuot et al., 1987). Allelic exchange was carried out as previously described (Pezard et al., 1991). The characteristics of the strains are given in Table IV.

Western analysis

Western blots were carried out as described previously, using the same antibodies (Mesnage et al., 1997).

Analysis of peptidoglycan hydrolases by renaturing gel electrophoresis

For this analysis, we used the technique described by Foster (1992).

Autolysis kinetics

Bacillus anthracis strains were grown in SPY medium to an OD600 of 0.5, centrifuged and concentrated 10 times in SPY devoid of glucose, to which 0.05 M NaN3 was added. The decrease in OD450 was then monitored.

Electron microscopy

Bacteria were grown on BHI agar plates for 16 h at 37°C. Ultrathin sections were cut as described by Etienne-Toumelin et al. (1995). For scanning electron microscopy, the samples were treated as described by Bray et al. (1993), and examined under a Jeol JSM-35CF microscope.

Purification of PS

Cell walls were prepared as described previously (Mesnage et al., 1999a). The total PS fraction was extracted from cell walls as described by Ekwunife et al. (1991). PS fractions were subjected to chromatography on a DEAE–Sephadex A50 column (1 × 15 cm) equilibrated with 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, and bound material was eluted with 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 500 mM NaCl.

Carbohydrate assay and determination of monosaccharide composition

Neutral carbohydrates were assayed by the phenol/sulfuric acid method (Chaplin, 1994). Monosaccharide composition was determined by GC on polyol acetate, as described by Sawardeker (1967).

Pyruvate assay

The samples were subjected to acid hydrolysis (500 mM HCl, 30 min, 100°C) to release pyruvate from PS. The amount of pyruvate was then assayed by an enzymatic method using the pyruvate assay kit (Sigma Diagnostics 726) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

In vitro PS binding assay

When ELISA was used to assay the in vitro binding of the various total PS fractions, microplates were coated with serial 1:2 dilutions of PS from 20 to 0.3 µg per well. Wells were saturated with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 2.5 µg of EA1-SLH polypeptide (Mesnage et al., 1999a) were added. When the ELISA was for analysis of dose–response binding, microplates were coated with 10 µg of purified fraction I or II per well. After saturation, serial 1:3 dilutions from 10 µg to 0.1 ng of EA1 or Sap SLH domains were added. Anti-EA1 SLH mice serum was added at a dilution of 1/1000; anti-Sap SLH rabbit serum was added at a dilution of 1/10 000. Anti-mice or anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Amersham) were added at a 1/1000 dilution and detected as previously described (Mesnage et al., 1999a). The anti-EA1 SLH serum was obtained by pooling the sera of mice immunized with the EA1-SLH domain (Mesnage et al., 1999a).

NMR spectroscopy

For NMR analysis, 5 mg of each fraction were disolved in 350 µl of D2O (99.95 atom %, Solvants Documentation Synthese, France) and transferred to a Shigemi tube. Spectra were recorded at 308 and 323 K at 500 MHz for 1H and at 125 MHz for 13C with a Varian Unity spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm triple resonance (1H, 13C, 15N) probehead with z gradient. External trimethylsilyl-3-propionic acid-d4 2,2,3,3 sodium salt (TMSP) was used as a reference. Spectral widths were 4000 Hz for proton and 24 000 or 30 000 Hz for carbon. A 60 ms mixing time was used in the TOCSY experiment and 120 ms mixing time was used in the gHSQC-TOCSY (Wilker et al., 1993). All the 2D experiments, including gHSQC but excluding gHMBC, were recorded in the phase-sensitive mode (States et al., 1982).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank P.Gounon and C.Rolin for electron microscopy, A.Atrih for peptidoglycan structure analysis and M.Lévy for PS binding assays. We would like to thank L.Gutmann for stimulating discussions, Y.Levy for critical reading of the manuscript and J.-P.Latgé, in whose laboratory part of this work was carried out. F.Brossier, M.Haustant, S.Denuault and G.Lambert are thanked for serum preparation and technical assistance. We thank P.Béguin, C.Bouthier de la Tour, V.Briolat, T.J.Beveridge, J.-F.Charles, I.Derré, B.Dupuy, B.K.Ghosh, A.-B.Kolstø and D.Lereclus for providing us with strains and DNA. We thank TIGR for making available the incomplete Bacillus anthracis genome sequence. S.M. and T.M. were funded by the Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche; S.M. also had a ‘Bourse de la Fondation Roux’.

References

- Altschul S.F., Madden,T.L., Schäffer,A.A., Zhang,J., Zhang,Z., Miller,W. and Lipman,D.J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T. and Schneewind,O. (1996) Target cell specificity of a bacteriocin molecule: a C-terminal signal directs lysostaphin to the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. EMBO J., 15, 4789–4797. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowditch R.D., Baumann,P. and Yousten,A.A. (1989) Cloning and sequencing of the gene encoding a 125-kilodalton surface layer protein from Bacillus sphaericus 2362 and of a related cryptic gene. J. Bacteriol., 171, 4178–4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray D.F., Bagu,J. and Koegler,P. (1993) Comparison of hexamethyldisilane (HMDS), peldri II, and critical-point drying methods for scanning electron microscopy of biological specimens. Micro. Res. Tech., 26, 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugert P. and Geider,K. (1995) Molecular analysis of the ams operon required for expopolysaccharide synthesis of Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Microbiol., 15, 917–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist G. (1997) AcmA of Lactococcus lactis, a cell-binding major autolysin. PhD thesis, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin M.F. (1994) Monosaccharides. In Rickwood,D. and Hames,B.D. (eds), Carbohydrate Analysis. A Practical Approach. 2nd edn. IRL Press at Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cossart P. and Jonquières,R. (2000) Sortase, a universal target for therapeutic agents against Gram-positive bacteria? Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 5013–5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekwunife F.S., Singh,J., Taylor,K.G. and Doyle,R.J. (1991) Isolation and purification of cell wall polysaccharide of Bacillus anthracis (Δ Sterne). FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 66, 257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt H. and Peters,J. (1998) Structural research on surface layers: a focus on stability, surface layer homology domains, and surface layer–cell wall interactions. J. Struct. Biol., 124, 276–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Toumelin I., Sirard,J.-C., Duflot,E., Mock,M. and Fouet,A. (1995) Characterization of the Bacillus anthracis S-layer: cloning and sequencing of the structural gene. J. Bacteriol., 177, 614–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster S.J. (1992) Analysis of the autolysin of Bacillus subtilis 168 during vegetative growth and differentiation by using renaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J. Bacteriol., 174, 464–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino T., Béguin,P. and Aubert,J.-P. (1993) Organization of a Clostridium thermocellum gene cluster encoding the cellulosomal scaffolding protein CipA and a protein possibly involved in attachment of the cellulosome to the cell surface. J. Bacteriol., 175, 1891–1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcìa J.L., Sanchez-Beato,A.R., Medrano,F.J. and Lopez,R. (1998) Versatility of choline-binding domain. Microb. Drug. Resist., 4, 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R.S. (1998) Protein phylogenies and signature sequences: a reappraisal of evolutionary relationships among archaebacteria, eubacteria, and eukaryotes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 62, 1435–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgason E., Økstad,O.A., Caugant,D.A., Johansen,H.A., Fouet,A., Mock,M., Hegna,I. and Kolstø,A.-B. (2000) Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis—one species based on genetic evidence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 66, 2627–2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez E., Ramisse,F., Ducoureau,J.-P., Cruel,T. and Cavallo,J.-D. (1998) Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. konkukian (serotype H34) superinfection: case report and experimental evidence of pathogenicity in immunosuppressed mice. J. Clin. Microbiol., 36, 2138–2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilk N., Kosma,P., Puchberger,M., Egelseer,E.M., Mayer,H.F., Sleytr,U.B. and Sára,M. (1999) Structural and functional analyses of the secondary cell wall polymer of Bacillus sphaericus CCM 2177 that serves as an S-layer-specific anchor. J. Bacteriol., 181, 7643–7646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosch M., Egelseer,E.M., Mattanovich,D., Sleytr,U.B. and Sára,M. (2000) S-layer gene sbsC of Bacillus stearothermophilus ATCC 12980: molecular characterization and heterologous expression in Escherichia coli. Microbiology, 146, 273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joliffe L.K., Doyle,R.J. and Streips,U.N. (1981) The energized membrane and cellular autolysis in Bacillus subtilis. Cell, 25, 753–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonquières R., Bierne,H., Fiedler,F., Gounon,P. and Cossart,P. (1999) Interaction between the protein InlB of Listeria monocytogenes and lipoteichoic acid: a novel mechanism of protein association at the surface of Gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol., 34, 902–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima N., Kaya,S., Araki,Y. and Ito,E. (1988) Pyruvic-acid-containing polysaccharide in the cell wall of Bacillus polymyxa AHU 1385. Eur. J. Biochem., 174, 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotiranta A., Haapasalo,M., Kari,K., Kerosuo,E., Olsen,I., Sorsa,T., Meurman,J.H. and Lounatmaa,K. (1998) Surface structure, hydrophobicity, phagocytosis, and adherence to matrix proteins of Bacillus cereus cells with and without the crystalline surface protein layer. Infect. Immun., 66, 4895–4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire M., Ohayon,H., Gounon,P., Fujino,T. and Béguin,P. (1995) OlpB, a new outer layer protein of Clostridium thermocellum, and binding of its S-layer-like domains to components of the cell envelope. J. Bacteriol., 177, 2451–2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas A., Engelhardt,H., Peters,J., Santarius,U., Volker,S. and Baumeister,W. (1994) Domain structure of the Acetogenium kivui surface layer revealed by electron crystallography and sequence analysis. J. Bacteriol., 176, 1224–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazmanian S.K., Liu,G., Ton-That,H. and Schneewind,O. (1999) Staphylococcus aureus sortase, an enzyme that anchors surface proteins to the cell wall. Science, 285, 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesnage S., Tosi-Couture,E., Mock,M., Gounon,P. and Fouet,A. (1997) Molecular characterization of the Bacillus anthracis main S-layer component: evidence that it is the major cell-associated antigen. Mol. Microbiol., 23, 1147–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesnage S., Tosi-Couture,E. and Fouet,A. (1999a) Production and cell surface anchoring of functional fusions between the SLH motifs of the Bacillus anthracis S-layer proteins and the Bacillus subtilis levansucrase. Mol. Microbiol., 31, 927–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesnage S., Weber-Levy,M., Haustant,M., Mock,M. and Fouet,A. (1999b) Cell surface-exposed tetanus toxin fragment C produced by recombinant Bacillus anthracis protects against tetanus toxin. Infect. Immun., 67, 4847–4850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messner P. and Sleytr,U.B. (1992) Crystalline bacterial cell-surface layers. Adv. Microb. Physiol., 33, 213–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár J. and Prágai,B. (1971) Attempts to detect the presence of teichoic acid in Bacillus anthracis. Acta Microbiol. Acad. Sci. Hung., 18, 105–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E. (1985) Nucleotide sequence of a spectinomycin adenyltransferase AAD(9) determinant from Staphylococcus aureus and its relationship to AAD(3′′)(9). Mol. Gen. Genet., 200, 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarre W.W. and Schneewind,O. (1999) Surface proteins of Gram-positive bacteria and mechanisms of their targeting to the cell wall envelope. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 63, 174–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oggioni M.R., Medaglini,D., Maggi,T. and Pozzi,G. (1999) Engineering the Gram-positive cell surface for construction of bacterial vaccine vectors. Methods, 19, 163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okinaka R.T. et al. (1999) Sequence and organization of pXO1, the large Bacillus anthracis plasmid harboring the anthrax toxin genes. J. Bacteriol., 181, 6509–6515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olabarrìa G., Carrascosa,J.L., Depedro,M.A. and Berenguer,J. (1996) A conserved motif in S-layer proteins is involved in peptidoglycan binding in Thermus thermophilus. J. Bacteriol., 178, 4765–4772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra G., Vaissaire,J., Weber-Levy,M., Le Doujet,C. and Mock,M. (1998) Molecular characterization of Bacillus strains involved in outbreaks of anthrax in France in 1997. J. Clin. Microbiol., 36, 3412–3414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezard C., Berche,P. and Mock,M. (1991) Contribution of individual toxin components to virulence of Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun., 59, 3472–3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pooley H.M. and Karamata,D. (1994) Teichoic acid synthesis in Bacillus subtilis: genetic organization and biological roles. In Ghuysen,J.-M. and Hakenbeck,R. (eds), Bacterial Cell Wall, Vol. 27. Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands, pp. 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Popham D.L. and Stragier,P. (1991) Cloning, characterization and expression of the spoVB gene of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol., 173, 7942–7949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramisse V., Patra,G., Vaissaire,J. and Mock,M. (1999) The Ba813 chromosomal DNA sequence effectively traces the whole Bacillus anthracis community. J. Appl. Microbiol., 87, 224–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries W., Hotzy,C., Schocher,I., Sleytr,U.B. and Sára,M. (1997) Evidence that the N-terminal part of the S-layer protein from Bacillus stearothermophilus pv72/p2 recognizes a secondary cell wall polymer. J. Bacteriol, 179, 3892–3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Sára M., Kuen,B., Mayer,H.F., Mandl,F., Schuster,K.C. and Sleytr,U.B. (1996) Dynamics in oxygen-induced changes in S-layer protein synthesis from Bacillus stearothermophilus PV72 and the S-layer-deficient variant T5 in continuous culture and studies of the cell wall composition. J. Bacteriol., 178, 2108–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawardeker J.S., Sloneker,J.H. and Jeanes,A. (1967) Quantitative determination of monosaccharides as their aldotol acetates by gas liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem., 37, 1602–1604. [Google Scholar]

- Schneewind O., Model,P. and Fischetti,V.A. (1992) Sorting of protein A to staphylococcal cell wall. Cell, 70, 267–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Séverin A., Horne,D. and Tomasz,A. (1997) Autolysis and cell wall degradation in a choline-independent strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb. Drug Res., 3, 391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl S. and Uhlen,M. (1997) Bacterial surface display: trends and progress. Trends Biotechnol., 15, 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- States D.J., Haberkorn,R.A. and Ruben,D.J. (1982) A two-dimensional nuclear Overhauser experiment with pure absorption phase in four quadrants. J. Magn. Reson., 48, 286–292. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson G., Andrianopoulos,K., Hobbs,M. and Reeves,P.R. (1996) Organization of the Escherichia coli K-12 gene cluster responsible for production of the extracellular polysaccharide colanic acid. J. Bacteriol., 178, 4885–4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M., Owens,K., Pietri,R., Zhu,X., McVeigh,R. and Ghosh,B.K. (1989) Cloning of the crystalline cell wall protein gene of Bacillus licheniformis NM 105. J. Bacteriol., 171, 6637–6648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trieu-Cuot P., Carlier,C., Martin,P. and Courvalin,P. (1987) Plasmid transfer by conjugation from Escherichia coli to Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 48, 289–294. [Google Scholar]

- Trieu-Cuot P., Carlier,C., Poyart-Salmeron,C. and Courvalin,P. (1991) An integrative vector exploiting the transposition properties of Tn1545 for insertional mutagenesis and cloning of genes from Gram-positive bacteria. Gene, 106, 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidel W. and Pelzer,H. (1964) Bagshaped macromolecules: a new outlook on bacterial cell walls. Adv. Enzymol., 26, 193–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilker W., Leibfritz,D., Kerssebaum,R. and Bermel,W. (1993) Gradient selection in inverse heteronuclear correlation spectroscopy. Magn. Reson. Chem., 31, 287–292. [Google Scholar]

- Yannish-Perron C., Vierra,J. and Messing,J. (1985) Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequence of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene, 33, 103–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.-R., Idanpaan-Heikkila,I., Fischer,W. and Tuomanen,E.I. (1999) Pneumococcal licD2 gene is involved in phosphorylcholine metabolism. Mol. Microbiol., 31, 1477–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]